Abstract

Objective

The morphology of the tongue and its relationship with the hard palate play an important role in the rehabilitation of patents with temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD). This study aimed to evaluate the intra-and inter-evaluator reliability of ultrasound measurements of tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness in healthy individuals.

Methods

Thirty healthy volunteers were assessed using a Mindray ultrasound device with a C5-1s probe. Two trained evaluators conducted two measurement sessions 1 week apart. Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were used to determine measurement reliability.

Results

The ICCs for tongue-palate distance were 0.745 (intra-evaluator) and 0.611 (inter-evaluator). For tongue thickness, the ICCs were 0.855 (intra-evaluator) and 0.730 (inter-evaluator). Individual evaluator reliability was consistent: Evaluator A showed ICCs of 0.761 (distance) and 0.862 (thickness); Evaluator B showed ICCs of 0.788 (distance) and 0.841 (thickness). All correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Ultrasound provides a reliable method for quantifying tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness in healthy subjects. These measures could support clinical assessment and rehabilitation planning for conditions such as TMD.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Tongue-palate distance, Tongue thickness, Healthy volunteers

Introduction

The tongue is an important component of the oral and maxillofacial systems, participating in various physiological activities such as chewing, swallowing, breathing, vocalization, oral sensation, and posture maintenance. The tongue plays a vital role in numerous physiological activities, requiring it to adapt and take various forms [1].

The correlation between the shape and size of the tongue and its surrounding tissue structure has long been a focal point of interest in the field of oral medicine [2]. Extensive research indicates that alterations in tongue position can significantly impact oral and maxillofacial functions [3–6]. Moreover, when the tongue is in the forward extension position, it exerts a slight but sustained outward force on the teeth [7], which significantly impacts both the vertical and horizontal directions of the teeth [8], leading to malocclusion. The volume relationship between the tongue and the oral cavity emerges as a crucial determinant influencing tooth alignment and occlusion [9]. When excluding other pathological factors, changes in tongue function may also lead to temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD) and pain [5]. Early diagnosis of abnormal tongue position and function prevents oral diseases such as malocclusion and TMD. However, due to the scalability and variability of the tongue itself, tongue measurement has become a challenge [2], which limits the in-depth exploration of related research areas. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore effective, accurate, and clinically feasible tongue measurement methods.

At present, X-ray lateral head positioning film- [10], computed tomography (CT) imaging- [11], magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)- [12], three-dimensional ultrasound- [13], and cone-beam computed tomography system (CBCT)-based measurement methods [9] can help evaluate tongue volume, tongue movements, and other parameters, indirectly or directly helping study tongue function from different aspects. However, these methods have certain limitations when it comes to clinical application. First, the utilization of lateral head positioning film and CT scans may subject patients to radiation exposure. Second, while CT-, MRI-, and three-dimensional ultrasound-based measurement methods can effectively delineate the boundaries of the tongue body, they often incur high examination costs. Last, the majority of the participants in previous studies were positioned supine, which fails to help replicate the functional dynamics of the tongue in everyday life [14]. Although patients can perform similar daily functional movements in an upright position during CBCT, in order to clearly identify the soft tissue boundaries on CBCT images, it is also necessary to apply radioactive contrast agents to the subject’s tongue and surrounding tissues [9], which carries certain risks.

Ultrasound evaluation is a commonly used imaging technique in clinical practice, offering advantages such as ease of operation, low cost, no radiation exposure, and no specific body position restrictions. In the past, some studies have applied ultrasound examination to assess sublingual regions in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome [15, 16]. In addition, certain scholars have explored the application of ultrasound in studying the interplay between the tongue and the palate during swallowing, specifically while utilizing ultrasound imaging to observe the movement relationship between the tongue and the palate on the sagittal plane, along with measuring the maximum average distance between these structures throughout the swallowing process [17]. Hence, the objective of this study was to assess the reliability of ultrasound measurements in evaluating the distance between the tongue and palate (tongue-palate distance), as well as the thickness of the tongue body, in individuals without any underlying health issues. This research aimed to establish a theoretical foundation for the practical implementation of ultrasound in assessing tongue shape and position in clinical settings.

We hypothesize that ultrasound can conveniently and accurately detect and measure the tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness, and it also exhibits relatively high intra-evaluator and inter-evaluator reliability.

Methods

General information

In the current study, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was adopted as the key index to assess the reliability of measurements. According to the established criteria [18], ICC < 0.69 = poor, 0.70–0.79 = moderate, 0.80–0.89 = good, and 0.90–0.99 = excellent. An ICC within the range of 0.70–0.99 was considered to demonstrate moderate to excellent reliability. Therefore, the expected ICC values for this study were set at 0.70 and 0.99. A total sample size of 18 participants was required to satisfy a significance level (α) of 0.05 with a power of 0.90 (PASS 15, NCSs, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA, 2017.). Additionally, a review of relevant literature on the reliability of ultrasound evaluation revealed that previous studies had employed sample sizes ranging from 16 to 32 cases [19–21]. Considering both the statistical calculation and the precedent in existing research, 30 participants were ultimately selected as the sample size for this study to ensure adequate statistical power and the generalizability of the study results.

From March 1, 2023, to April 30, 2023, 30 healthy participants, including 12 men and 18 women, were recruited from the hospital where the researchers work. Ethical approval was granted by the institutional ethics committee. All participants were provided with a clear understanding of the study’s purpose to ensure transparency and ethical conduct. They were required to sign an informed consent form indicating their voluntary participation. Moreover, participants retained the right to withdraw from the experiment at any point, emphasizing the importance of their autonomy and well-being.

This study employed specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the appropriate selection of participants. The inclusion criteria for healthy individuals were defined as follows: good systemic health status; no history of macrotrauma or surgical intervention involving the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) or cervical region; no prior diagnosis of TMD; absence of TMD-related signs and symptoms; and no evidence of TMD upon brief clinical evaluation [22]. Age should be 18 years old or older. The exclusion criteria consisted of individuals with cognitive impairment, rendering them unable to cooperate effectively, and those with known allergies to coupling gel.

Table 1 shows the participants’ age, height, weight, and body mass index.

Table 1.

General information on the participants

| N | Age (years) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | BMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 29 ± 1.16 | 166.27 ± 1.49 | 65.90 ± 2.87 | 23.46 ± 0.70 |

BMI body mass index

Testing methods

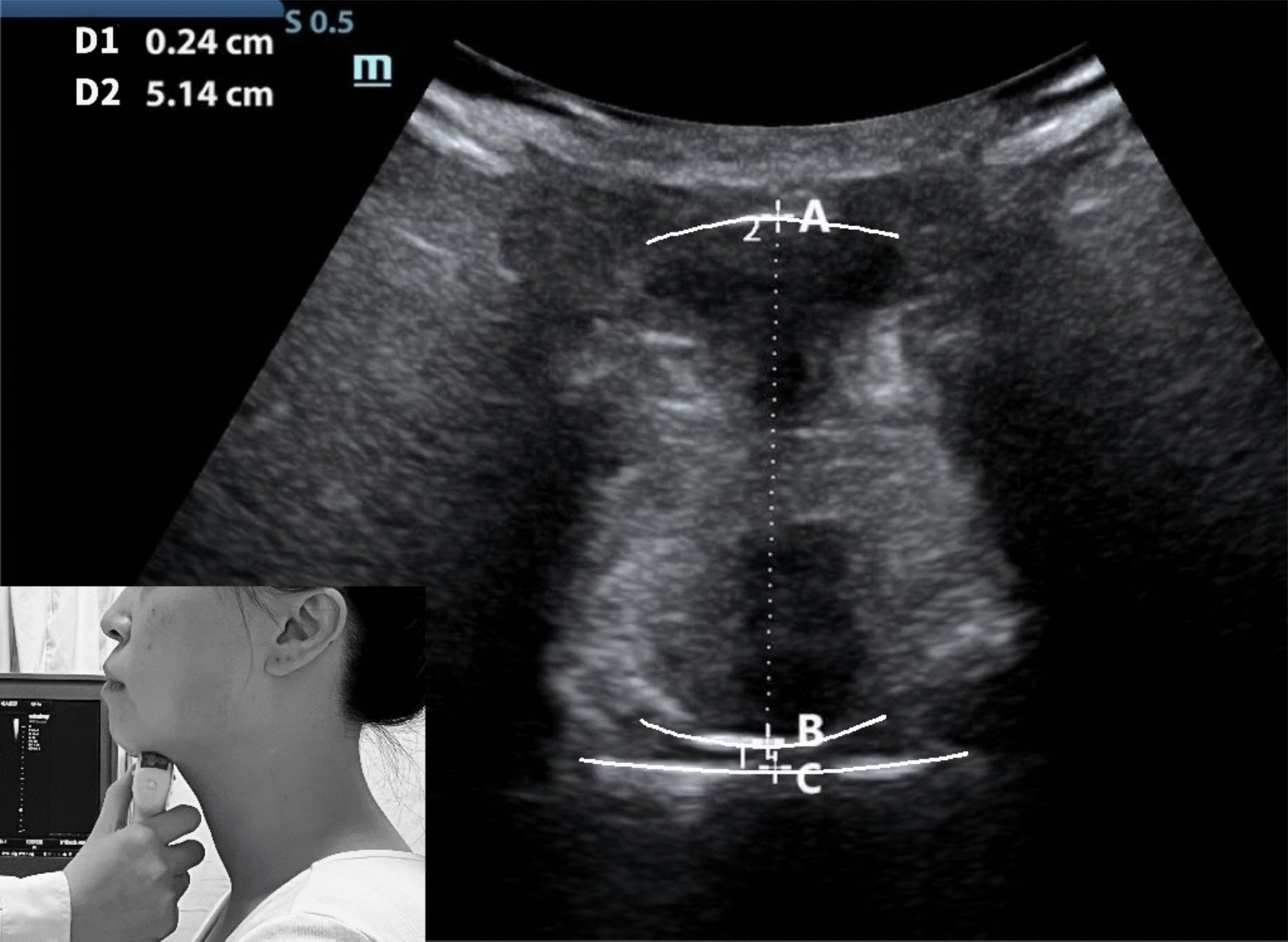

The participants were asked to be seated comfortably and look straight ahead in their habitual position; this involved ensuring no support was provided for their back while maintaining a chair height of 42 cm. The evaluator used Mindray ultrasound, UMT-500, and convex array probe C5-1s, Shenzhen Mindray Biomedical Electronics Co., Ltd. Initially, the probe was positioned at the anterior region of the subject's mandibular floor, aligning with its long axis, before gradually moving toward the hyoid bone. The short axis was placed between the posterior aspect of the tongue and the upper palate, enabling the measurement and documentation of tongue-palate distance. Screenshots were captured to measure and record tongue thickness (Fig. 1). The ultrasound mode was set to a frequency of 5 MHz and a depth of 8 cm. Two evaluators performed the measurements twice for the assessment of both intra-evaluator and inter-evaluator reliability. The mean values were derived for each evaluator, and data from the previous and subsequent evaluations were considered for assessment of the internal reliability between different evaluators (Evaluator A and Evaluator B). The interval between the two evaluations was 1 week, and a dedicated person recorded the data. The measurement indicators were tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound image of the tongue body scanned on the frontal plane. A Base tongue side bottom; B dorsal side of tongue; C palate surface. AB: tongue thickness, BC: distance between the tongue and palate

Tongue-palate distance: The distance between the tongue’s upper surface and the hard palate [23], in centimeters.

Tongue thickness: The vertical distance from the surface of the hyoid muscle to the back of the tongue [24], in centimeters.

Evaluator preparation and training

A blind evaluation approach was employed in this study, and two evaluators were selected. One evaluator had extensive ultrasonography experience, with over 10 years of practical knowledge in the field. The second evaluator was a physiotherapist who had been working for 1 year and received 1 h of specific training in ultrasonography. The training included (1) 20 min of formal training on the ultrasound technique for tongue and palate measurements and (2) practice on five healthy volunteers (40 min) to become familiar with the protocol and measurement procedure. Both evaluators performed their measurements independently in the same controlled environment and were unaware of each other’s evaluation outcomes. The testing order of the two evaluators was randomized during the experiment to minimize potential bias.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed using the SPSS version 22.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). The measurement data are expressed as x ± SD. To assess the intra-evaluator and inter-evaluator reliability when evaluating tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC 3,1) with 95% confidence intervals were used. ICC and 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the following criteria [18]: < 0.69 = poor, 0.70–0.79 = moderate, 0.80–0.89 = good, and 0.90–0.99 = excellent. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests were used to assess the data’s normality and variance homogeneity, respectively. The Mann–Whitney U test would be used if there is any non-parametric data.

Results

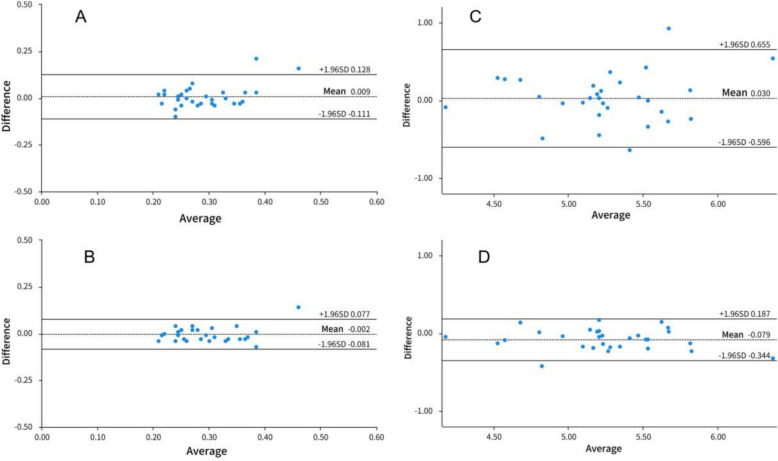

The intra- and inter-evaluator ICC for tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness

The intra-evaluator ICC for tongue-palate distance was 0.745 (95%CI 0.642–0.856), and the inter-evaluator ICC was 0.611 (95%CI 0.393–0.770). The intra-evaluator ICC for tongue thickness was 0.855 (95%CI 0.729–0.937), and the inter-evaluator ICC was 0.730 (95%CI 0.546–0847), as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2A–D.

Table 2.

The intra- and inter-evaluator ICC for tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness

| Intra-evaluator | Evaluation data ( ± SD) | ICC | SEM | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluator A (cm) | Evaluator B (cm) | ||||

| Tongue-palate distance | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.611** | 0.095 | 0.393–0.770 |

| Tongue thickness | 5.26 ± 0.50 | 5.23 ± 0.46 | 0.730** | 0.075 | 0.546–0.847 |

| Inter-evaluator | 1st evaluation (cm) | 2nd evaluation (cm) | |||

| Tongue-palate distance | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 0.745** | 0.053 | 0.642–0.856 |

| Tongue thickness | 5.21 ± 0.47 | 5.29 ± 0.49 | 0.855** | 0.053 | 0.729–0.937 |

ICC Correlation coefficient, SEM Standard error, CI Confidence interval; **< 0.05 represents a significant correlation

Fig. 2.

A Bland–Altman plots of intra-evaluator ICC for tongue-palate distance. B Bland–Altman plots of inter-evaluator ICC for tongue-palate distance. C Bland–Altman plots of intra-evaluator ICC for tongue thickness. D Bland–Altman plots of inter-evaluator ICC for tongue thickness

Individual evaluator reliability

Evaluator A showed ICC of 0.761(95%CI 0.655–0.892) for tongue-palate distance and 0.862 (95%CI 0.672–0.957) for tongue thickness; Evaluator B showed ICCs of 0.788 (95%CI 0.576–0.907) for tongue-palate distance and 0.841 (95%CI 0.606–0.950) for tongue thickness, as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3A–D.

Table 3.

Individual evaluator reliability

| Evaluator A | Evaluation data ( ± SD) | ICC | SEM | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st evaluation (cm) | 2nd evaluation (cm) | ||||

| Tongue jaw distance | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.761** | 0.058 | 0.655–0.892 |

| Tongue thickness | 5.23 ± 0.48 | 5.30 ± 0.52 | 0.862** | 0.075 | 0.672–0.957 |

| Evaluator B | 1st evaluation (cm) | 2nd evaluation (cm) | |||

| Tongue jaw distance | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.788** | 0.086 | 0.576–0.907 |

| Tongue thickness | 5.19 ± 0.47 | 5.27 ± 0.46 | 0.841** | 0.089 | 0.606–0.950 |

ICC correlation coefficient, SEM standard error, CI confidence interval; **< 0.05 represents a significant correlation

Fig. 3.

A Bland–Altman plots of intra-evaluator ICC of Evaluator A for tongue-palate distance. B Bland–Altman plots of inter-evaluator ICC of Evaluator A for tongue-palate distance. C Bland–Altman plots of intra-evaluator ICC of Evaluator B for tongue thickness. D Bland–Altman plots of inter-evaluator ICC of Evaluator B for tongue thickness

Discussion

Before applying ultrasonography to measure tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness in a clinical context, it is crucial to assess its reliability. The objective of this study was to explore the intra-evaluator and inter-evaluator reliability of using ultrasonography to measure tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness in healthy individuals maintaining their natural head and neck positions.

The findings of this study indicate that ultrasonography holds promise as a valuable tool for assessing the size of the tongue and its relative position with respect to the neighboring structures, introducing a novel approach and methodology for clinical evaluations of the tongue. The intra-evaluator reliability for tongue thickness demonstrated good agreement. Meanwhile, the inter- and intra-evaluator reliability analysis for tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness yielded a moderate ICC. Notably, a moderate reliability was also observed between evaluators for tongue-palate distance based on the ICC. These results suggest that the ultrasound-based measurement method employed in evaluating tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness has high accuracy and repeatability.

The tongue is crucial in various oral functions, such as chewing, swallowing, and speech. Working with the mandible and hyoid bone, it forms a complex biomechanical system. Recognizing the interplay and influence of these components is imperative in clinical diagnosis and treatment, as it allows for a comprehensive understanding of the intricate dynamics involved [25]. Changes/dysfunctions in the appearance, posture, and/or mobility of the lips, tongue, mandible, and cheeks, as well as changes/dysfunctions in oral and maxillofacial functions, may lead to dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint [26], leading to TMD. In TMD patients, the changes in chewing and swallowing functions are closely related to the changes in hyoid position. This difference in vertical position could be attributed to potential disruptions in the length–tension relationship of the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles, resulting from altered tension in the mastication muscles. Consequently, these changes in muscle tension can contribute to modifications in the vertical position of the hyoid bone, ultimately leading to an increased horizontal distance between the maxilla and the hyoid bone [3], thus reducing the contraction amplitude of the suprahyoid muscle [27], and thereby affecting the tongue’s position in the oral cavity.

The tongue’s position when people hold their head in a natural posture is the natural resting position of the tongue when the jaw is at rest. It is characterized by the tongue being situated within the oral cavity, specifically at floor of the oral cavity. In this position, the tongue may rest between the teeth, either within the boundaries of the cutting surfaces or extending slightly beyond them [7]. Based on the Balance theory, the tongue exerts a subtle yet consistent force on the teeth, which can significantly impact their positioning in both the vertical and horizontal directions. Consequently, if a patient’s tongue position is more anteriorly positioned, this force is amplified, subsequently affecting the alignment and positioning of the teeth [4]. However, there are differences in tongue position among individuals with different types of malocclusion, and a previous study found that there are significant differences in tongue position among different types of anterior malocclusion during apical dislocation [4].

It should be emphasized that all tongue muscles, including external and internal muscles, always work together rather than separately [28]. The balance between the tension of these muscles must be maintained; otherwise, dysfunction may occur, leading to changes in the position of the hyoid bone and tongue function [7]. Increased lip activity also makes the muscles around the mouth abnormally tense. When this happens, the tip of the tongue is placed either on the front teeth or against the front teeth. Even if the force applied as a result of this placement is slight, if it lasts for too long, the front teeth will open, affecting the coordinated activities of the mastication muscles [29]. Research suggests that the mastication muscles provide a certain degree of mandibular stability during tongue movement [30], and in an optimal clinical state of tongue function, additional activation of the muscles of mastication is not required during tongue movements [31].

Abnormal changes in tongue position are often observed in clinical practice. Ji et al. [23] chose the commonly used X-ray cephalometric films in orthodontic diagnosis combined with tongue back imaging technology to determine the position of the tongue, that is, to measure the parameters of the back shape curve of the tongue. They established a tongue back shape measurement method, summarized and analyzed several common types of tongue posture positions, and found that healthy participants mostly have a normal flat or high arch tongue position [32], which means that tongue-palate distance is relatively narrow. Individuals with normal tongue posture have the tongue surface closer to the upper jaw than that in those with abnormal tongue posture. Future research can further analyze and compare the differences in tongue-palate distance between patients with oral and maxillofacial system dysfunction and healthy individuals and the tongue position characteristics in TMD patients.

If the tongue’s ability to change is reduced, it may lead to TMJ problems, dysphagia, dysgeusia, and pronunciation disorder [5]; this is attributable to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome [6]. The common clinical manifestations of chewing and swallowing function in TMD patients are unilateral chewing preference and inappropriate tongue positioning, accompanied by significant contraction of the perioral muscle [7]. Therefore, individuals with abnormal tongue thickness may have problems such as those related to chewing, swallowing, and pronunciation; however, there is limited research on this topic, and further exploration is required.

In the assessment of tongue morphology, it is noteworthy that computed tomography (CT) utilizes ionizing radiation, a factor that constitutes a distinct drawback. Conversely, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) presents a safer alternative, as it is devoid of ionizing radiation exposure. Nevertheless, it is imperative to recognize that MRI is generally associated with higher costs relative to CT [33]. Ultrasound, by virtue of its non-involvement with ionizing radiation, stands out as a significant advantage in this context.

Although CT, MRI, and three-dimensional ultrasound techniques are capable of delineating the boundaries of the tongue body, their elevated examination costs render them unsuitable for routine clinical assessments [15]. The ultrasound-based evaluation approach enables tongue measurements across multiple postures, including sitting, supine, and standing positions-capabilities unattainable with CT, MRI, and other modalities—thereby further underscoring the merits of ultrasound-based assessment [2].

A review of prior studies has revealed that ultrasound measurements exhibit high reliability when conducted by the same evaluator [20]. Additionally, even following short-term training, novice evaluators can achieve excellent consistency in their measurements when compared to experienced counterparts [19]. This is also one of the reasons why ultrasound can be used to evaluate the relationship between the tongue and the oral cavity.

This study shows that ultrasound-based measurement is highly reliable in evaluation of tongue thickness. The average tongue thickness measured in this study was 5.27 ± 0.42, which differs from the 5.83 ± 0.43 reported by Zhou et al. because the methods for measuring tongue thickness differ. In the study by Zhou et al. [33], participants were given instructions to close their mouths, lightly touch the tip of their tongue to their front teeth, and relax without making any sound, and the ultrasound image was obtained when the entire contour of the tongue was visible within the ultrasound field of view. The measurement conducted in this study involved determining the maximum size, referred to as the skin-tongue distance, which was measured from the lingual surface to the chin skin while the participants were in a supine position. Notably, the findings revealed that the distance, known as the tongue thickness, measured from the sublingual surface to the lingual surface while the participants were sitting, was smaller than that reported by Zhou et al. [33].

Therefore, ultrasound-based measurement of tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness is a simple and easy-to-master rehabilitation assessment technique, which is convenient for clinical practice.

Despite these favorable findings, the present study has several limitations. First, due to the lack of gold standards for measuring tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness, ultrasound-based evaluation was not compared with other measurement methods, resulting in a lack of validity analysis data. Second, in this study, the definition of “healthy individuals” relied on participants’ self-reported absence of pain or discomfort, without objective assessments of craniofacial structures, occlusal conditions, facial biotypes, or orofacial muscle function. Third, the 1-week interval between repeated measurements may not be sufficient to fully eliminate memory bias. Given the complex interactions between craniofacial morphology and tongue biomechanics, these omissions may introduce some variability into the research findings.

In summary, ultrasonography-based measurement exhibits excellent intra-evaluator and inter-evaluator reliability when evaluating tongue-palate distance and tongue thickness. Furthermore, ultrasonography is characterized by its fast learning curve, simplicity of operation, absence of radiation, and cost-effectiveness. These advantages make ultrasonography an accessible and reliable method for conducting clinical evaluations at any given time, ensuring dependable results. It is recommended to use this method as an auxiliary tool for clinical work and research on the characteristics of the tongue.

Acknowledgements

All authors are funded by Shanghai Rehabilitation Medicine Clinical Medical Research Center 21MC1930200 and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (project number YG2021QN70).

Author contributions

Yan Tang: conceptualization, ideas, research goals and aims; Shi-Zhen Zhang(Co-first author): data curation, writing original draft, methodology development or design of methodology, creation of models; Yuan Yao: resources, supervision, methodology development or design of methodology, creation of models; Ji-Ling Ye: methodology development or design of methodology, research goals and aims, software programming, software development, designing computer programs; Lei Jin: investigation conducting a research and investigation process, software programming, software development, designing computer programs; Li-Li Xu: resource, supervision, funding acquisition, acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication; Xin Jiang (Corresponding Author): conceptualization, resources, supervision; research goals and aims, testing of existing code components; Zhong-Yi Fang (Co corresponding author):data curation, writing original draft, creation of models, software programming, software development, this author contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-corresponding author.

Funding

All authors are funded by Shanghai Rehabilitation Medicine Clinical Medical Research Center 21MC1930200, Key Discipline Construction Project Supported by Shanghai Health Commission (2023ZDFC0303) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (project number YG2021QN70).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Batch number: SH9H-2019-T316-2.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xin Jiang, Email: jiangxinkylie@163.com.

Zhong-Yi Fang, Email: tonyfangtony@163.com.

References

- 1.Stone M. A three-dimensional model of tongue movement based on ultrasound and x-ray microbeam data. J Acoust Soc Am. 1990;87(5):2207–17. 10.1121/1.399188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan JL, Duan YZ, Guo J, Zhao LL. Localization measurement of human tongue by ultrasonic imaging. J Clin Res. 2006;8:1178–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber P, Corrêa EC, Bolzan GP, Ferreira FS, Soares JC, Silva AM. Chewing and swallowing in young women with temporomandibular disorder. Codas. 2013;25(4):375–80. 10.1590/s2317-17822013005000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Y, Lin YL, Xu LY. Comparative study on tongue characteristics in intercuspal occlusion and tongue’s natural resting position. J Oral Sci Res. 2015;31(04):377–80+84. 10.13701/j.cnki.kqyxyj.2015.04.017.

- 5.Bordoni B, Morabito B, Mitrano R, Simonelli M, Toccafondi A. The anatomical relationships of the tongue with the body system. Cureus. 2018;10(12):e3695–6. 10.7759/cureus.3695. (Epub 2019/03/07). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kajee Y, Pelteret JP, Reddy BD. The biomechanics of the human tongue. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2013;29(4):492–514. 10.1002/cnm.2531. (Epub 2013/01/16). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marim GC, Machado BCZ, Trawitzki LVV, de Felicio CM. Tongue strength, masticatory and swallowing dysfunction in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorder. Physiol Behav. 2019;210: 112616. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louis MME. Contemporary ortheodontics. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding X, Suzuki S, Shiga M, Ohbayashi N, Kurabayashi T, Moriyama K. Evaluation of tongue volume and oral cavity capacity using cone-beam computed tomography. Odontology. 2018;106(3):266–73. 10.1007/s10266-017-0335-0. (Epub 2018/02/23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen AM, Vig PS. A serial growth study of the tongue and intermaxillary space. Angle Orthod. 1976;46(4):332–7. 10.1043/0003-3219(1976)046%3c0332:Asgsot%3e2.0.Co;2. (Epub 1976/10/01). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe AA, Gionhaku N, Takeuchi K, Fleetham JA. Three-dimensional CT reconstructions of tongue and airway in adult subjects with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1986;90(5):364–74. 10.1016/0889-5406(86)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauder R, Muhl ZF. Estimation of tongue volume from magnetic resonance imaging. Angle Orthod. 1991;61(3):175–84. 10.1043/0003-3219(1991)061%3c0175:Eotvfm%3e2.0.Co;2. (Epub 1991/01/01). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wein B. A new procedure for 3-dimensional reconstruction of the surface of the tongue from ultrasound images. Ultraschall Med. 1990;11(6):306–10. 10.1055/s-2007-1011582. (Epub 1990/12/01). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekprachayakoon I, Miyamoto JJ, Inoue-Arai MS, Honda EI, Takada JI, Kurabayashi T, Moriyama K. New application of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of deglutitive tongue movement. Prog Orthod. 2018;19(1): 45. 10.1186/s40510-018-0245-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao J, Duan YZ, Lin Z, Zhang YZ. Measurement of human tongue by ultrasonic imaging. J Pract Stom. 2002;03:253–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manlises CO, Chen JW, Huang CC. Dynamic tongue area measurements in ultrasound images for adults with obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2020;29(4): e13032. 10.1111/jsr.13032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohkubo M, Scobbie JM. Tongue shape dynamics in swallowing using sagittal ultrasound. Dysphagia. 2019;34(1):112–8. 10.1007/s00455-018-9921-8. (Epub 2018/06/30). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim BB, Lee JH, Jeong HJ, Cynn HS. Effects of suboccipital release with craniocervical flexion exercise on craniocervical alignment and extrinsic cervical muscle activity in subjects with forward head posture. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2016;30:31–7. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar P, Cruziah R, Bradley M, Gray S, Swinkels A. Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of ultrasonographic measurements of acromion-greater tuberosity distance in patients with post-stroke hemiplegia. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2016;23(3):147–53. 10.1080/10749357.2015.1120455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar P, Chetwynd J, Evans A, Wardle G, Crick C, Richardson B. Interrater and intrarater reliability of ultrasonographic measurements of acromion-greater tuberosity distance in healthy people. Physiother Theory Pract. 2011;27(2):172–5. 10.3109/09593985.2010.481012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar P, Bradley M, Swinkels A. Within-day and day-to-day intrarater reliability of ultrasonographic measurements of acromion-greater tuberosity distance in healthy people. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010;26(5):347–51. 10.3109/09593980903059522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YH, Auh QS, An JS, Kim T. Poorer sleep quality in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders compared to healthy controls. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1): 246. 10.1186/s12891-022-05195-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourdiol P, Mishellany-Dutour A, Peyron MA, Woda A. Contributory role of the tongue and mandible in modulating the in-mouth air cavity at rest. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(9):2025–32. 10.1007/s00784-012-0897-8. (Epub 2012/12/18). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamori M, Imamura E, Fukuta M, Tachiyama K, Kamimura T, Hayashi Y, Matsushima H, Ogawa K, Nishino M, Hirata A, Mizoue T, Wakabayashi S. Tongue thickness measured by ultrasonography is associated with tongue pressure in the Japanese elderly. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8): e0230224. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Messina G. The tongue, mandible, hyoid system. Eur J Transl Myol. 2017;27(1): 6363. 10.4081/ejtm.2017.6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Felício CM, de Oliveira MM, da Silva MA. Effects of orofacial myofunctional therapy on temporomandibular disorders. Cranio. 2010;28(4):249–59. 10.1179/crn.2010.033. (Epub 2010/11/03). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fassicollo CE, Machado BCZ, Garcia DM, de Felicio CM. Swallowing changes related to chronic temporomandibular disorders. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(8):3287–96. 10.1007/s00784-018-2760-z. (Epub 2018/11/30). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarado C, Arminjon A, Damieux-Verdeaux C, Lhotte C, Condemine C, Cousin AS, Sigaux N, Bouletreau P, Mateo S. Impaired tongue motor control after temporomandibular disorder: a proof-of-concept case-control study of tongue print. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022;8(2):529–36. 10.1002/cre2.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson EH, Hall JT, Zwemer JD. Swallowing patterns in human subjects with and without temporomandibular dysfunction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;98(6):507–11. 10.1016/0889-5406(90)70016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komoda Y, Iida T, Kothari M, Komiyama O, Baad-Hansen L, Kawara M, Sessle B, Svensson P. Repeated tongue lift movement induces neuroplasticity in corticomotor control of tongue and jaw muscles in humans. Brain Res. 2015;1627:70–9. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melchior MO, Valencise Magri L, Da Silva A, Cazal MS, Da Silva M. Influence of tongue exercise and orofacial myofunctional status on the electromyographic activity and pain of chronic painful TMD. Cranio. 2021;39(5):445–51. 10.1080/08869634.2019.1656918. (Epub 2019/08/23). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji CR, Zhou CL, Li WC, Ma L. Measurement method and classification of tongue posture position. Beijing Journal of Stomatology. 1998(01):6–8+16.

- 33.Zhou YM, Yuan YM, Yao WD, Li YH. Predicting value for difficult laryngoscopy in patients with osahs by measuring tongue thickness with ultrasonography. Acta Academiae Medicinae Wannan. 2020;39(03):263–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.