Abstract

Reproductive rights, including access to abortion, contraception, and comprehensive healthcare, are critical for gender equality and public health. However, these rights remain contentious and heavily influenced by cultural, religious, and political ideologies, creating barriers to equitable care and justice globally. This narrative review examines and compares both abortion laws and policies in the United States and Iran, two ideologically distinct nations with striking parallels in their restrictive approaches. This narrative review identifies key similarities, including the politicization of abortion, the influence of cultural and religious doctrines, and the disproportionate burden of restrictive policies on marginalized populations, leading to unsafe abortions. It also explores major differences, such as the decentralized, state-specific legal variability in the United States versus Iran’s centralized theocratic governance, where demographic goals drive restrictions. These findings highlight how geopolitical and ideological contexts shape reproductive governance and health outcomes. Despite ideological contrasts, the United States and Iran exhibit analogous restrictive trends, revealing global challenges in advancing reproductive justice. Addressing these barriers requires a dual approach: targeted legal and policy reforms within national contexts, particularly in the U.S. and Iran, and alignment with international advocacy efforts promoting reproductive autonomy and human rights. The findings provide critical insights for policymakers and healthcare providers aiming to reform reproductive health frameworks and ensure equitable, rights-based care.

Keywords: Abortion, United States, Iran, Comparative analysis

Background

Reproductive rights encompass the legal entitlements and freedoms related to reproductive health, which can vary significantly across different nations. These rights include the ability of individuals and couples to make informed and autonomous decisions regarding the number, spacing, and timing of their children, as well as access to the necessary information and resources to do so. Central components of reproductive rights include access to safe and legal abortion services, various methods of contraception, protection against forced sterilization and contraception, comprehensive reproductive healthcare services, reproductive education to enable informed choices, and safeguards against harmful practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) [1–3]. Reproductive rights are essential for achieving gender justice. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies access to safe abortion and contraception as core components of sexual and reproductive health care, integral to achieving universal health coverage and reducing maternal mortality [4]. Also, ensuring access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services is vital for upholding the dignity, rights, and overall well-being of individuals globally [5]. Moreover, reproductive rights significantly advance broader objectives such as universal health coverage, gender equality, and economic and social development [6]. They are closely linked to the concept of reproductive justice, a framework that not only upholds these rights but also emphasizes the social, economic, and political conditions that shape individuals’ ability to access and exercise them [4].

The political landscapes of the United States of America (USA) and Iran are deeply rooted in distinct historical and legal traditions that reflect their unique governance systems. In the USA, the foundation of law is the Constitution, establishing a federal system that balances power among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. This framework emphasizes the rule of law, democratic principles, and the protection of individual liberties, with a dynamic interplay between federal authority and state rights [7]. In Iran, the political structure is based on a theocratic model, where governance combines modern state institutions with Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) [8]. The Supreme Leader holds ultimate authority, and laws derive legitimacy from Sharia principles, interpreted by religious scholars, and integrated with civil governance [9]. These contrasting systems highlight the divergent ways societies embed historical, cultural, and ideological values into their legal and political frameworks, shaping both domestic and international policies.

Fluctuations in reproductive rights, especially abortion access, significantly impact women’s health and socioeconomic status globally, as seen in both the USA and Iran. In the USA, legal restrictions on essential healthcare services, including family planning and maternal care, lead to increased rates of unintended pregnancies and associated health risks [10]. Policies often labeled as “Pro-life” reduce women’s ability to make autonomous decisions about pregnancy, impacting their workforce participation and access to educational opportunities. These effects are particularly pronounced among younger women, low-income individuals, and racial or ethnic minorities, who face compounded barriers to healthcare and economic stability [10]. Similarly, in Iran, reproductive challenges rooted in religious and cultural norms present notable risks to women’s health. Limited access to modern contraceptives, comprehensive sexual education, and safe medical procedures exacerbates health risks, including illegal abortions and heightened maternal morbidity and mortality. These issues are further compounded by systemic healthcare access disparities, disproportionately affecting rural and marginalized communities [11]. Together, these examples highlight the multifaceted and intersectional challenges that restrictive reproductive policies pose to women’s health and well-being.

This is a narrative review based on the synthesis of academic literature, legal statutes, policy reports, and relevant case law, aimed at comparing the ideological and legal drivers of abortion policy in the USA and Iran. While Iran and the USA may seem worlds apart—divided by decades of political hostility, cultural contrasts, and ideological clashes—they share an unexpected and intriguing commonality: a retreat in reproductive rights. These two nations, whose relations have been fraught with complexity and tension since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, are bucking a global trend by tightening abortion laws. By conducting a comparative analysis, the study reveals the broader implications of these restrictions on health outcomes and socio-political structures. This exploration underscores how two seemingly disparate nations can enact policies with similar repercussions, offering critical insights into the global challenges posed by reproductive governance amidst contrasting geopolitical and ideological landscapes.

Historical context and current legal framework

Iran

Iran’s legal and social stance on abortion has undergone significant fluctuations over the years. The modern legal framework initially criminalized abortion in 1926, imposing severe penalties unless the procedure was necessary to save the mother’s life. The first notable decriminalization occurred in 1969, expanding the legal grounds for abortion to include preserving the mother’s health. By 1976, the law permitted unrestricted abortion up to 12 weeks of gestation, contingent upon the parents’ decision and the provision of valid reasons. Additionally, therapeutic abortions were allowed without gestational limits, requiring only the mother’s consent and the professional judgment of physicians [12]. However, the law did not provide explicit criteria; the decision was generally grounded in the physician’s medical expertise, considering factors such as the mother’s health, psychological well-being, or other valid medical reasons. Physicians were expected to evaluate the situation based on their clinical assessment, often referencing available medical guidelines or established norms of care. These guidelines, however, were not always formalized in a standardized format, leaving room for professional discretion.

Following the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the legal status of abortion shifted again. In 1982, abortion was criminalized following Shia jurisprudence, and penalties included the payment of blood money. While Islamic scholars generally permit abortion before the point of ensoulment (120 days), significant debate remains about the circumstances under which abortion is permissible within this timeframe [13]. From 1982 to 1998, the law allowed abortion exclusively to save the mother’s life. In 2005, the enactment of the Therapeutic Abortion Act permitted abortions in cases of severe fetal anomalies or conditions threatening the mother’s life, provided certain criteria were met. However, the process was highly regulated, requiring the approval of a multidisciplinary team comprising Muslim physicians, forensic medicine experts, and a judge, with final authority resting with the judiciary [12].

The legal framework governing abortion access in Iran became significantly more restrictive with the enactment of the Rejuvenation of the Population and Protection of the Family (RPPF) law in 2021. Following a dramatic decline in fertility rates during the late 2000s, driven by family planning initiatives, the government shifted to pronatalist policies in 2005 [14], reflecting the state’s demographic priorities and efforts to promote population growth. The RPPF law imposed substantial restrictions on access to contraceptives, prohibiting sterilization procedures such as vasectomies and tubal ligations, and limiting the distribution of contraceptives to individuals with specific medical conditions. This shift has raised worries about the potential for an increase in various types of illegal and unsafe abortion, as couples may seek alternative means to control their family size [15]. A rapid transition from an anti-natal policy to promoting population growth by restricting access to affordable long-acting contraceptive methods (such as sterilization and IUDs) can lead to an increase in unintended pregnancies, potentially driving women to resort to illegal, clandestine abortions [16]. Under the provisions of the RPPF law, abortion is permitted only under narrowly defined circumstances: when the pregnancy poses a life-threatening risk to the mother or involves severe fetal anomalies, provided the fetus is under 120 days of gestation. Even in these cases, approval is contingent upon a rigorous review process involving a multidisciplinary panel comprising forensic medicine experts, Muslim physicians, and a judge, with the judiciary retaining ultimate authority over the decision. These restrictions have further curtailed reproductive autonomy, exacerbating barriers to legal abortion access [17].

The united states of America

The development of abortion access, as a reproductive right, in the USA has undergone significant transformations, characterized by pivotal legal cases and evolving societal perspectives. Landmark rulings such as Roe v. Wade (1973) and its reversal in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization have notably affected abortion legislation. Prior to Roe, most states imposed severe restrictions on abortion, allowing exceptions primarily when the mother’s life was at risk. By the mid-19th century, numerous states prohibited abortion at all pregnancy stages, influenced by moral, religious, and medical considerations [18]. During the early to mid-20th century, restrictive abortion laws led to the rise of illegal abortions, creating a significant public health crisis. It is estimated that, annually, thousands of women died or suffered severe complications due to illegal procedures [19]. By the late 1960s, the dire consequences of restrictive laws began to drive advocacy for abortion rights. Some states, including California and New York, liberalized abortion laws to address these public health concerns, but access remained deeply unequal, depending on socioeconomic and geographical factors [20].

In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade established a constitutional right to abortion, asserting that this right was implicit in the right to privacy protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. This landmark ruling invalidated many state laws restricting abortion, setting a federal standard that prohibited states from banning abortions before fetal viability, generally recognized around 24 weeks of gestation [21]. The ruling was a watershed moment in abortion access and reproductive rights, shaping decades of legal and societal discourse [22].

The 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey came before the Supreme Court after several states passed increasingly restrictive abortion laws meant to undermine the protections established in Roe v. Wade, including provisions such as mandatory waiting periods, parental consent for minors, and informed consent requirements. These laws reflected a broader trend among states attempting to limit access to abortion through regulations designed to undermine the protections established in Roe v. Wade. In Casey, the Court reaffirmed the core holding of Roe, maintaining the constitutional right to abortion, but introduced a new legal standard: regulations would be permitted so long as they did not impose an “undue burden” on a woman’s ability to obtain an abortion. This “undue burden” standard allowed states to enact certain restrictions—such as waiting periods and parental consent—as long as they did not create substantial obstacles. Following the decision, many states implemented increasingly creative and targeted regulations that tested the boundaries of the undue burden framework [23].

In June 2022, the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned Roe v. Wade, declaring that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion [24]. This decision returned the authority to regulate abortion to individual states, resulting in a fragmented legal landscape. As Carole Joffe has documented, this volatility isn’t only legislative or judicial—the very clinics themselves are under siege from a sprawling web of ‘TRAP’ regulations, state inspections, and targeted restrictions that cumulatively raise the bar for keeping doors open. Joffe shows how, since 2010, over 400 state-level provisions have specifically targeted clinic architecture (ASC standards), physician privileges, and even the post-procedure experience of patients—forcing many providers to divert precious resources into million-dollar facility upgrades or intensive legal defense rather than patient care. Her ethnographic interviews with over fifty clinic administrators reveal that these “pen” tactics have become as lethal to access as the “six-gun” attacks of decades past, eroding the “woman-centered” ethos of care long championed by independent providers [25].

Following the Dobbs decision, abortion access in the USA has become a state-level issue, creating significant disparities. As of 2025, abortion is banned in 14 states. Additionally, several states have implemented restrictive measures, such as six-week bans, mandatory waiting periods, and counseling requirements. Conversely, states like California, New York, and Illinois have expanded access by enshrining abortion rights in their state constitutions and providing support for out-of-state patients seeking care [26].

Table 1 presents a comparative timeline highlighting key developments in abortion laws in the USA and Iran, illustrating the historical evolution and policy shifts within each country.

Table 1.

Comparative timeline of abortion law developments in the USA and Iran

| Year | USA | Iran |

|---|---|---|

| 1800–1960 s | ⨉ Abortion largely criminalized. Exceptions only when mother’s life at risk [19].. | |

| 1926 | ⨉ Abortion criminalized, only permitted to save mother’s life [12].. | |

| 1969–1976 |

Liberalized laws: abortions allowed up to 12 weeks; therapeutic abortion permitted [12].. Liberalized laws: abortions allowed up to 12 weeks; therapeutic abortion permitted [12].. |

|

| 1973 |

Roe v. Wade– Constitutional right to abortion established [21].. Roe v. Wade– Constitutional right to abortion established [21].. |

|

| 1979–1982 | ⨉ Post-revolution, abortion criminalized again; only allowed to save mother’s life [12].. | |

| 1992 |

Planned Parenthood v. Casey– Introduced “undue burden” standard [23]. Planned Parenthood v. Casey– Introduced “undue burden” standard [23]. |

|

| 2005 |

Therapeutic Abortion Act– Allows abortion for fetal anomalies or maternal risk [12].. Therapeutic Abortion Act– Allows abortion for fetal anomalies or maternal risk [12].. |

|

| 2021 | ⨉ RPPF Law– Major restrictions; only allows abortion in limited cases under judiciary oversight [14]. | |

| 2022 | ⨉ Dobbs v. Jackson– Roe overturned; abortion rights returned to states [24]. | |

| 2025 | ⨉  Patchwork laws: bans in 14 states, protections in others [26]. Patchwork laws: bans in 14 states, protections in others [26]. |

Political drivers

Iran’s national health policies are closely shaped by Islamic principles, with religious doctrine playing a central role in legal and medical decision-making [27]. The Ministry of Health operates within this framework, actively promoting family planning programs that align with both public health goals and religious guidelines [28]. Post-abortion care is available in public and private healthcare settings, reflecting a pragmatic approach to maternal health [29]. However, access to legal abortion remains highly restricted. Therapeutic abortion is only permitted under specific conditions—such as when the mother’s life is at risk or in cases of severe fetal anomalies—and even then, the process is complex and bureaucratically demanding. It requires approvals from multiple medical specialists and final authorization by the Legal Medicine Organization, ensuring that each case adheres strictly to religious and legal criteria [30]. This process ensures alignment with Shi’a Islamic jurisprudence, underscoring why abortion policy in Iran is better categorized under religious drivers rather than political drivers, as seen in more secular contexts like the USA.

Abortion is a highly politicized issue in the USA, shaped not only by the partisan divide between Democrats and Republicans but also by the influence of state governments, activist groups, healthcare providers, and religious organizations [31]. Republican-controlled states have enacted numerous restrictions in recent years [32, 33]. The issue plays a key role in mobilizing voters, particularly women [34]. Voter mobilization increases when abortion is prominent, especially among individuals with strong religious convictions. Religious identity often aligns with political affiliation, and both conservative and progressive faith-based groups actively mobilize their members. Data shows abortion is increasingly important to voters who prioritize religious values, highlighting a strong connection between faith and political engagement [35].

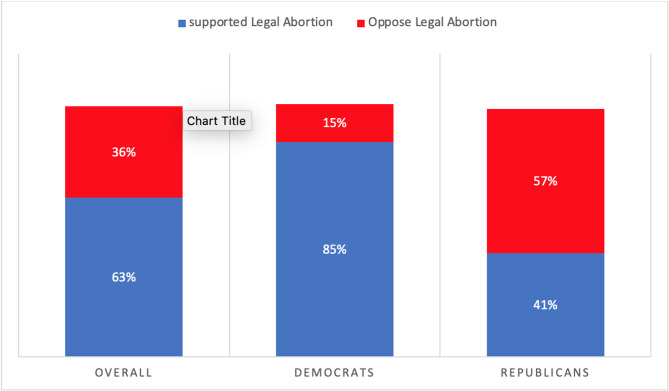

Moreover, it should be mentioned that, within each party, there is significant intra-party variation. On the Democratic side, while the majority of the party supports abortion rights, some centrist or conservative Democrats, particularly in swing states, have shown hesitation or support for restrictions, often influenced by regional and religious dynamics. In the Republican Party, while the pro-life stance is dominant, there is a growing faction of moderate Republicans who advocate for exceptions, such as in cases of rape or incest, particularly in the face of shifting public opinion on abortion access. This intra-party divergence complicates the clear-cut partisan divide and highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of party dynamics on abortion policy [36, 37]. According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in April 2024, 63% of Americans believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% think it should be illegal in all or most cases. This overall support masks a significant partisan divide. Among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, 85% support legal abortion in all or most cases. In contrast, only 41% of Republicans and Republican leaners share this view (Fig. 1) [38].

Fig. 1.

American Public Opinion on Legal Abortion (2024)

Political economy drivers are crucial in shaping the legacy of the USA because they influence the interplay between markets and politics, which in turn affects social, economic, and political outcomes [39]. Insurance companies in the USA play a significant role in healthcare delivery, primarily through managing costs via mechanisms like prior authorization, low reimbursement rates, and exclusions of certain services from coverage [40]. However, abortion coverage in the United States is shaped less by insurer preferences and more by a complex web of federal and state legislation. The Hyde Amendment, for instance, prohibits the use of federal funds for abortion services except in cases of rape, incest, or life endangerment. This federal restriction directly affects Medicaid coverage and indirectly influences access through its chilling effect on broader policy implementation. Some states, such as California, Oregon, and New York, have chosen to use state Medicaid funds to cover abortion services, but the majority do not—resulting in considerable disparities in access. Additionally, at least 26 states restrict abortion coverage in private insurance plans, including those offered through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchanges, often requiring a separate rider to obtain coverage [41]. Given these legislative constraints, many individuals end up paying out of pocket for abortion services, even when they have insurance coverage [42].

Religious drivers

In Iran, most of the population identify as Muslims. In Islam, abortion debates revolve around the concept of “ensoulment,” believed to occur around the fourth month of pregnancy. Abortion is haram (forbidden) regardless of ensoulment, but after ensoulment it is legally prohibited. Before ensoulment, exceptions are made based on one of the key Islamic principles, the rule of “La-haraj”. This rule states that Islam does not impose unbearable difficulty on its believers. Therefore, if a pregnancy presents an unbearable burden on a woman or her family, Islamic law allows for abortion before ensoulment. Cases where the fetus is diagnosed with severe abnormalities or genetic conditions that would lead to unbearable suffering for the child and family are also considered grounds for abortion before ensoulment. Once the fetus is considered to have a soul, abortion is strictly prohibited even if the mother’s life is in danger. The only exception is in situations where both the mother and the fetus are in danger, and abortion would save the mother’s life [43–46].

Interpretations of these conditions vary among religious authorities, with Ayatollahs issuing fatwas that reflect differing opinions. In Shiite Islam, Ayatollahs are senior jurists qualified to issue new religious rulings after over 30 years of rigorous training and recognition from peers. Ordinary Muslims may consult them for guidance on religious matters. Fatwas are formal rulings issued by these scholars in response to specific questions, based on the Quran, hadiths, and reasoning. They address various aspects of Islamic life, including complex issues like abortion [27, 47]. While traditional interpretations often correlate Islamic teachings with large families, socio-economic transformations have led to various understandings [48]. Shiite scholars mostly forbid abortion in the cases of rape and illegitimate pregnancies, even before ensoulment. The permissibility of abortion for medical reasons, such as saving the mother’s life, is generally agreed upon. Contemporary rulings have expanded the permissible grounds to fetal viability as a reason for requesting a therapeutic abortion. Moreover, scholars have permitted abortions when the fetus has congenital disorders that have serious long-term social or economic hardships for families if carrying a child to term. This demonstrates a degree of flexibility within Islamic jurisprudence [46].

In the USA, religiosity—particularly among Christians—strongly correlates with opposition to abortion, shaping both political activism and cultural attitudes. Conservative Christian groups, including many Catholic and evangelical communities, have been instrumental in lobbying for restrictive abortion policies and promoting alternatives such as crisis pregnancy centers [31, 49]. States with higher levels of religiosity are significantly more likely to enact restrictive abortion laws. However, Christianity is not monolithic in its views; some denominations and religious leaders support abortion rights, often invoking religious freedom and compassion in cases involving the mother’s health, fetal anomalies, or pregnancies resulting from rape [50]. These internal religious debates influence not only individual attitudes but also how religious communities mobilize politically—either reinforcing abortion restrictions or advocating for access under specific conditions [51].

Cultural and socioeconomical drivers

In Iran, economic challenges, such as low family income and financial hardship [52], coupled with the social pressure to maintain a certain standard of living, create difficult choices for families facing unintended pregnancies [15, 47]. Cultural, regional, and ethnic differences further shape attitudes. Differences in reproductive behaviors such as desire to childbearing, number of desired children, and method of contraception in different ethnical groups shape different attitudes towards terminating an unwanted pregnancy and acceptance of abortion [53, 54]. Moreover, changing cultural norms are expected to contribute to a rising trend in abortion rates, with conservative cities reporting lower abortion rates and liberal areas, such as Tehran, showing higher rates of abortion. These changes include more openness toward discussing abortion, more liberal cultural attitudes, characterized by lower religiosity and greater acceptance of gender equality and modern family values [54–56]. Over the past two decades, a gradual shift towards more liberal attitudes on abortion has been observed in Iran. Younger generations, in particular, demonstrate a more accepting view of abortion compared to older cohorts [56].

Despite the legal provision for abortion under specific circumstances, stigma remains a significant barrier for women seeking abortions. Cultural emphasis on motherhood, collectivist values, and the view of abortion as sinful contribute to societal judgment, especially in more religious communities [54, 57, 58]. Unmarried women face additional challenges due to social taboos against premarital relationships, which can lead to unwanted pregnancies and an increased demand for abortion [59]. Partner influence also plays a significant role in reproductive decisions [60]. For instance, a study that found economic status to be the main reason for induced abortion, husbands were the most common individuals encouraging women to have an abortion [61].

In the USA, various forms of media—including news outlets, entertainment media, and social media—play a significant role in shaping public opinion on abortion. News media influence how the abortion debate is framed, often emphasizing political conflict, moral dimensions, or individual narratives, which can sway public attitudes. Entertainment media, though sometimes inaccurate, have begun to portray abortion more frequently and empathetically, potentially reducing stigma and increasing public understanding. Social media platforms, meanwhile, have become key arenas for advocacy, allowing both pro-choice and pro-life groups to mobilize supporters, spread messaging, and influence undecided audiences. Through these channels, media can amplify awareness of systemic inequalities related to race, class, and gender that affect abortion access, indirectly contributing to broader cultural and political debates on reproductive rights [62, 63].

The United States’ racial and ethnic diversity significantly shapes how abortion is perceived, accessed, and experienced. Abortion stigma—manifesting as shame, secrecy, or fear of judgment—can deter individuals from seeking care, and this stigma is often experienced differently across racial and ethnic groups [64–68]. Structural racism compounds these differences, with communities of color disproportionately facing barriers such as limited clinic access, financial obstacles, and inadequate reproductive healthcare infrastructure. For example, Black and Latina women are more likely to live in areas with abortion restrictions and fewer providers, contributing to higher rates of unintended pregnancies and limited options for care. At the same time, cultural and religious beliefs within communities—such as those found in some Asian American, Latinx, or immigrant populations—can reinforce stigma and influence abortion decision-making. Additionally, mistrust of the medical system, rooted in historical injustices like forced sterilization and medical neglect, can further complicate access to abortion care among marginalized groups. These intersecting factors highlight the need to consider race and ethnicity not just as demographic variables, but as central to understanding the structural and cultural dynamics shaping abortion access and attitudes in the USA [67, 68].

Additionally, abortion policy in the USA is increasingly influenced by shifts in donor funding and financial support from opposition groups, particularly those with significant resources. Over the past few decades, well-funded conservative donor networks have played a substantial role in shaping the national conversation around abortion. Organizations such as the National Right to Life Committee and Americans United for Life have received substantial financial backing from donors who aim to influence political campaigns and judicial appointments. These financial contributions have enabled opposition groups to strategically target state-level legislative changes, contributing to a patchwork of abortion laws that reflect the priorities of affluent and well-resourced interest groups. This dynamic underscores the growing importance of financial resources in the shaping of abortion policy [69].

Comparative analysis

Both Iran and the USA illustrate that religion plays a notable role in shaping abortion regulations and access. In Iran, this influence is explicitly reflected in formal legislation and policymaking. In another form, in the USA, religious groups and churches exert considerable influence indirectly, particularly through electoral processes and lobbying efforts, which become more pronounced when Republicans, who rely heavily on support from conservative constituencies, hold power [31]. However, the differing political systems in these countries have resulted in distinct pathways toward implementing such restrictions. The USA, as a secular nation with a federal structure and an independent judiciary, faces greater challenges in imposing nationwide restrictions on abortion. The tension between conservative and liberal states prevents the federal government from making sweeping, uniform decisions on abortion laws. While this decentralized system can act as a buffer against immediate conservative reforms, it also limits the ability of liberal groups to secure nationwide protection for abortion rights. In contrast, Iran operates as a centralized Islamic state where religious authorities exert direct and indirect influence over policymaking. Consequently, decisions to limit abortion access, such as the 2021 enactment of the RPPF law, were implemented with relative ease.

Islam and Christianity, as Abrahamic religions with shared theological roots, exhibit notable similarities in their perspectives on abortion, family planning, and the regulation of women’s bodies [70]. Despite these foundational parallels, contemporary interpretations have led to significant divergences between the two contexts. Nonetheless, hardliners in both Iran and the USA are deeply influenced by religious doctrines and principles, leading to policies and decisions that aim to restrict access to abortion. Both pro-life movements in the USA and cultural norms in Iran put a large emphasis on the life of the fetus rather than the mother’s autonomy. Believing abortion to be a sin leads to social stigma and self-stigma of having an induced abortion in women who choose abortion due to different reasons, even calling the act a representation of narcissism [71]. This view is further strengthened by the importance of motherhood and its sanctity.

On the other hand, the multicultural characteristics of both countries’ populations, mainly due to different ethnical groups in Iran and different ethnical and racial groups in the USA, cause different perspectives regarding abortion in terms of stigma and acceptance, and differences regarding financial barriers and access to clinics.

In both countries, restrictive abortion laws could contribute to an increase in illegal abortion practices. Criminalization of abortion is associated with increased risks of maternal mortality or morbidity, because illegal abortions often become unsafe due to the clandestine conditions under which they are carried out, such as by untrained individuals, in non-clinical settings, or using harmful methods. In Iran, nearly half of illegal abortions are medically unsafe, leading to serious public health consequences [15, 72, 73]. Criminalization contributes to delayed abortion and post abortion care until women are severely ill, poor quality post abortion care, sexual and financial exploitation, and financial costs. Moreover, restrictions create black markets for abortion medication, and negatively impacts the provider–patient relationship [73].

These legal limitations disproportionately affect marginalized groups, including immigrants and individuals with low socioeconomic status. In Iran, women from low-income backgrounds are more likely to seek abortion due to economic hardship and limited social support and are more likely to resort to illegal, clandestine abortions due to financial and social constraints [74]. In the USA, half of women seeking abortion live below the federal poverty level. Denial of abortion services exacerbate their condition in terms of loss of full-time employment and poverty [10]. However, many of these individuals only have public insurance and are prohibited from using it to pay for abortion services. This is a major factor of seeking self-managed abortion [75]. This could be particularly evident among people of color [76]. Moreover, in both Iran and the USA, access to therapeutic abortion presents significant challenges. In Iran, it remains highly regulated, requiring a complex approval process involving multiple medical specialists and formal authorization from the Legal Medicine Organization [29]. Similarly, in certain U.S. states, recent policy developments have introduced layered legal and procedural hurdles that restrict access to abortion services, even when such procedures are technically permitted [77]. In addition, in both the USA and Iran, self-managed medication abortions are often clinically indistinguishable from spontaneous miscarriages and are typically documented and managed as such within healthcare systems. Healthcare providers frequently advise patients not to disclose their use of abortifacient medications, particularly in jurisdictions with restrictive abortion laws, to mitigate the risk of legal repercussions. Consequently, there are no dedicated post-abortion care (PAC) programs specific to self-managed abortions in either context; instead, follow-up care is administered through standard miscarriage or emergency care protocols [78–80].

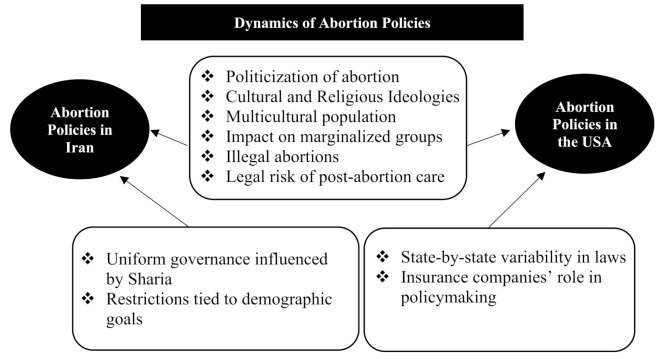

Concerns regarding population growth in Iran played a significant role in the implementation of the RPPF law, which imposed stricter restrictions on abortion. In contrast, population growth dynamics have not been a major driving factor in shaping abortion regulations in the USA. Conversely, insurance companies have played a significant role in policymaking and lobbying efforts related to abortion regulations in the USA, while this influence is largely absent in Iran, where abortion policies are shaped primarily by governmental authorities. Figure 2 shows the dynamics of abortion policies in the USA and Iran.

Fig. 2.

Comparative Matrix: Dynamics of Abortion Policies in the USA and Iran

Conclusion

Restrictive abortion policies in both the USA and Iran reveal how deeply cultural, religious, and ideological values can shape reproductive laws, regardless of political system or governance structure. In the USA, anti-abortion groups leverage financial resources and political advocacy to influence legislation. In Iran, religious doctrine and national priorities drive the formation of reproductive policies. Despite their vastly different political and religious contexts, both countries have arrived at similarly restrictive approaches to abortion, reflecting a convergence rooted in traditional values and ideological commitments rather than evidence-based public health strategies. This alignment underscores a broader global trend: restrictive reproductive policies are not confined to one type of governance or region, but can emerge in both secular democracies and religious theocracies. However, the strategies for addressing these restrictions must be context-specific. The mechanisms of influence, the sources of authority, and the public’s relationship to the state differ significantly in each case. In Iran, change may require religious reinterpretation or shifts within clerical leadership, whereas in the USA, advocacy may focus more on legal challenges, electoral mobilization, and public opinion. Recognizing these differences is essential to developing effective, culturally sensitive responses that prioritize reproductive autonomy while navigating distinct social and political terrains.

Acknowledgements

We utilized OpenAI’s ChatGPT for support in clarifying language and improving the overall readability of the text. All substantive content and scientific interpretations were developed and verified independently by the authors.

Author contributions

M.H. conceptualized the study. M.H. and F.H. wrote the manuscript. S.H. revised it. All authors reviewed the final version and approved it.

Funding

Not applicant.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicant.

Consent for publication

Not applicant.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Buser JM. Women’s Reproductive Rights Are Global Human Rights. J Transcult Nurs. 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 29];33(5):565–6. Available from: 10.1177/10436596221118112 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Whelan AM, Bratcher Goodwin M. The Impact of Reproductive Rights on Women’s Development. In: Redlich AD, Quas JA, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Developmental Psychology and the Law. Oxford University Press; 2023 [cited 2024 Oct 29];0. Available from: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197549513.013.25

- 3.Morison T, Le Grice JS. Reproductive Justice: Illuminating the Intersectional Politics of Sexual and Reproductive Issues. In: Zurbriggen EL, Capdevila R, editors. The Palgrave Handbook of Power, Gender, and Psychology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023 [cited 2024 Oct 29];419–35. Available from: 10.1007/978-3-031-41531-9_23

- 4.Onwuachi-Saunders C, Dang QP, Murray J, Reproductive Rights. Reproductive Justice: Redefining Challenges to Create Optimal Health for All Women. J Healthc Sci Humanit. 2019 [cited 2025 Apr 22];9(1):19–31. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9930478/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sexual. and reproductive health and rights. [cited 2024 Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights

- 6.Why Reproductive Rights Matter. in an Open Society. [cited 2024 Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/why-reproductive-rights-matter-open-society

- 7.Ginsburg T, Huq AZ. How to Save a Constitutional Democracy. First Edition. Chicago London: University of Chicago Press 2020;305

- 8.Haddadi M, Sahebi L, Hedayati F, Shah IH, Parsaei M, Shariat M et al. Induced abortion in Iran, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, the law and the diverging attitude of medical and health science students. PLOS ONE. 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 22];20(3):e0320302. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0320302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Arjomand SA, Arjomand SA. The turban for the crown: the Islamic revolution in Iran. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press 1990;304. Studies in Middle Eastern History). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster DG, Biggs MA, Ralph L, Gerdts C, Roberts S, Glymour MM. Socioeconomic outcomes of women who receive and women who are denied wanted abortions in the united States. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):407–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erfani A. Policy Implications of Cultural Shifts and Enduring Low Fertility in Iran. 2019;112–5.

- 12.Abbasi M, Shamsi Gooshki E, Allahbedashti N. Abortion in Iranian legal system: a review. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;13(1):71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abortion: An islamic ethical KA, view. 2007 [cited 2024 Feb 24];6(5):29–33. Available from: https://www.sid.ir/paper/291152/fa

- 14.Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME). Iran) statistical centre of iran. iran.Demographic and health survey (IDHS). Ministry of Health and Medical Education (Iran), Statistical Centre of Iran. 2000.

- 15.Shirdel E, Asadisarvestani K, Kargar FH. The abortion trend after the pronatalist turn of population policies in iran: a systematic review from 2005 to 2022. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosseini H, Erfani A, Nojomi M. Factors associated with incidence of induced abortion in hamedan, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20(5):282–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aramesh K. Population, abortion, contraception, and the relation between biopolitics, bioethics, and Biolaw in Iran. Dev World Bioeth. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mohr JC. Abortion in america: the origins and evolution of National policy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press 1979;352. [Google Scholar]

- 19.University of California Press. [cited 2024 Nov 26]. Liberty and Sexuality by David Garrow - Paper. Available from: https://www.ucpress.edu/books/liberty-and-sexuality/paper

- 20.Solinger R. Reproductive Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know®. New York: Oxford University Press Oxford 2013;240. (What Everyone Needs To Know®). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Justia Law. [cited 2024 Nov 26]. Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113. 1973. Available from: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/410/113/

- 22.Greenhouse L, Siegel R. Before Roe v. Wade: Voices that Shaped the Abortion Debate before the Supreme Court’s Ruling. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2012 [cited 2024 Nov 26]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2131505

- 23.Justia Law. [cited 2024 Nov 26]. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833. 1992. Available from: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/505/833/

- 24.National Constitution Center.– constitutioncenter.org. [cited 2024 Nov 26]. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization | Constitution Center. Available from: https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/supreme-court-case-library/dobbs-v-jackson-womens-health-organization

- 25.Joffe C. The Struggle to Save Abortion Care. Contexts. 2018 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Apr 29];17(3):22–7. Available from: 10.1177/1536504218792522

- 26.Guttmacher Institute. 2025. Interactive Map: U.S. Abortion Policies and Access.

- 27.Moinifar HS. Religious leaders and family planning in Iran. Iran Cauc. 2007;11(2):299–313. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehryar AH, Ahmad-Nia S, Kazemipour S. Reproductive health in iran: pragmatic achievements, unmet needs, and ethical challenges in a theocratic system. Stud Fam Plann. 2007;38(4):352–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghodrati F. Controversial issues of abortion license according to religious and jurisprudential laws in iran: A systematic review. Curr Women’s Health Reviews. 2020;16(2):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badieian Mosavi N, Hejazi SA, Sadeghipour F, Fotovat A, Hoseini M. Examination of fetal indications in 548 cases of abortion therapy permissions issued by forensic medicine center of Razavi khorasan, iran, in 2015. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertility. 2018;21(5):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halfmann D. Doctors and demonstrators: how political institutions shape abortion law in the united states, britain, and Canada. University of Chicago Press 2011;368.

- 32.Laws Affecting Reproductive Health and Rights. 2015 State Policy Review | Guttmacher Institute. 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/laws-affecting-reproductive-health-and-rights-2015-state-policy-review

- 33.2015 Year-End State Policy Roundup | Guttmacher Institute. 2016 [cited 2024 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2016/01/2015-year-end-state-policy-roundup

- 34.Rohlinger DA. Abortion politics, mass media, and social movements in America. Cambridge University Press 2015;187.

- 35.Adamczyk A, Valdimarsdóttir M. Understanding americans’ abortion attitudes: the role of the local religious context. Soc Sci Res. 2018;71:129–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnell M. House Republican supports abortion exceptions for rape, citing personal experience. The Hill. 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 25]. Available from: https://thehill.com/homenews/sunday-talk-shows/3481052-house-republican-supports-abortion-exceptions-for-rape-citing-personal-experience/

- 37.Diamant J. Three-in-ten or more Democrats and Republicans don’t agree with their party on abortion. Pew Research Center. 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/06/18/three-in-ten-or-more-democrats-and-republicans-dont-agree-with-their-party-on-abortion/

- 38.Public Opinion on Abortion. Pew Research Center. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/public-opinion-on-abortion/

- 39.Hacker JS, Hertel-Fernandez A, Pierson P, Thelen K, editors. The American political economy: politics, markets, and power. Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press 2021;400. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh K, Ratnam SS. The influence of abortion legislation on maternal mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998;63(Suppl 1):S123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Published I. How State Policies Shape Access to Abortion Coverage. KFF. 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/interactive-how-state-policies-shape-access-to-abortion-coverage/

- 42.Jerman J, Jones RK, Onda T. Characteristics of U.S. Abortion Patients in 2014 and Changes Since 2008. 2016 [cited 2025 Jun 7]; Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/characteristics-us-abortion-patients-2014

- 43.Aramesh K. Abortion: an Islamic ethical view. 2007 [cited 2024 Nov 18]; Available from: https://www.sid.ir/EN/VEWSSID/J_pdf/9432007S501.pdf

- 44.Aramesh K. A closer look at the abortion debate in Iran. Am J Bioeth. 2009;9(8):57–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ardestani AS, Esfahani MK, Hussieni SM. Abortion in the views of different religions and laws. J Pol L. 2016;9:99. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hedayat KM, Shooshtarizadeh P, Raza M. Therapeutic abortion in islam: contemporary views of Muslim shiite scholars and effect of recent Iranian legislation. J Med Ethics. 2006;32(11):652–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shamshiri-Milani H, Pourreza A, Akbari F. Knowledge and attitudes of a number of Iranian Policy-makers towards abortion. J Reprod Infertility. 2010;11(3):189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Youssef NH. 3 The Status and Fertility Patterns of Muslim Women. In: Beck L, Keddie N, editors. Women in the Muslim World. Harvard University Press 2013 [cited 2024 Nov 19];69–99. Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.4159/harvard.9780674733091.c4/html?lang=en&srsltid=AfmBOoq_yK-x6bmzBdiLW9CMtj4qtu_y6o0WXYdFbeLwCxgU5aTzJ5wd

- 49.Adamczyk A, Kim C, Dillon L. Examining public opinion about abortion: A Mixed-Methods systematic review of research over the last 15 years. Sociol Inq. 2020;90(4):920–54. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoffmann JP, Johnson SM. Attitudes toward abortion among religious traditions in the united states: change or continuity?? Sociol Relig. 2005;66(2):161–82. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bohrer B. The abortion debate in American christianity: church authority structures, denominational responses, and the stances of the affiliated. SN Soc Sci. 2022;2(3):24. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ranji A. Induced abortion in iran: prevalence, reasons, and consequences. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2012;57(5):482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abasi Z, Keshavarz Z, Abbasi- Shavazi MJ, Ebadi A, Esmaily H, Poorbarat S. Comparative study of reproductive behaviors in two ethnicities of Fars and Turkmen in North khorasan, Iran. J Midwifery Reproductive Health. 2022;10(1):3109–18. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farash Kheialo N, Ramzi N, Sadeghi R. Social and cultural determinants of students’ attitudes toward abortion. Women’s Strategic Stud. 2020;22(87):109–30. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erfani A. Induced abortion in tehran, iran: estimated rates and correlates. Int Perspect Sex Reproductive Health. 2011;37(3):134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hosseini H, Bagi M. The rise of Liberal attitudes toward abortion in Iran. Int J Popul Issues. 2025;2(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rasoulyan F, Mirnezami SR, Nasr AK, Morshed-Behbahani B. Abortion stigma, government regulation and religiosity: findings from the case of Iran. J Economic Stud. 2023;51(5):1127–43. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cultural Atlas. 2016 [cited 2024 Nov 27]. Iranian - Family. Available from: https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/iranian-culture/iranian-culture-family

- 59.Motamedi M, Merghati-Khoei E, Shahbazi M, Rahimi-Naghani S, Salehi M, Karimi M, et al. Paradoxical attitudes toward premarital dating and sexual encounters in tehran, iran: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abdoljabbari M, Karamkhani M, Saharkhiz N, Pourhosseingholi M, Khoubestani MS. Study of the effective factors in women’s decision to make abortion and their belief and religious views in this regard. J Pizhūhish Dar Dīn Va Salāmat. 2016;2(4):44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morteza A, Marzieh K, Nasrin S, Mohammadamin P, Masoumeh SK, Study of the effective factors in women’s decision to make abortion and their belief and religious views in this regard. 2016;2(4):46–54.

- 62.Herold S, Becker A, Schroeder R, Sisson G. Exposure to lived representations of abortion in popular television program plotlines on abortion-Related knowledge, attitudes, and support: an exploratory study. Sex Roles. 2024;90(2):280–93. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Herold S. Abortion in entertainment media, 2019–2024. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2024;36(6):400–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Norris A, Bessett D, Steinberg JR, Kavanaugh ML, De Zordo S, Becker D. Abortion stigma: a reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(3 Suppl):S49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Danner K. The a-word: destigmatizing abortion in American culture. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2022; Available from: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd/3976

- 66.Adair L, Lozano N, Ferenczi N. Abortion attitudes across cultural contexts: exploring the role of gender inequality, abortion policy, and individual values. Int Perspect Psychology: Res Pract Consultation. 2024;13(3):138–52. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown K, Laverde R, Barr-Walker J, Steinauer J. Understanding the role of race in abortion stigma in the united states: a systematic scoping review. Sex Reproductive Health Matters. 2022;30(1):2141972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chandrasekaran S, Key K, Ow A, Lindsey A, Chin J, Goode B et al. The role of community and culture in abortion perceptions, decisions, and experiences among Asian Americans. Front Public Health. 2023 [cited 2024 Nov 14];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.982215/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.INSTITUTE INDEX. The secret money behind the push to ban abortion | Facing South. [cited 2025 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.facingsouth.org/2019/05/institute-index-secret-money-behind-push-ban-abortion

- 70.Silverstein AJ, Stroumsa GG, editors. Introduction. In: The Oxford Handbook of the Abrahamic Religions. Oxford University Press 2015 [cited 2024 Dec 27];0. Available from: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697762.002.0007

- 71.Motaghi Z, Keramat A, Shariati M, Yunesian M. Triangular assessment of the etiology of induced abortion in iran: a qualitative study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(11):e9442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Editors TPM. Why restricting access to abortion damages women’s health. PLOS Medicine. 2022 Jul 26 [cited 2024 Dec 27];19(7):e1004075. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1004075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Geneva: World Health Organization. Abortion care guideline. 2022. Report No.: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 74.Haseli A, Rahnejat N, Rasoal D. Reasons for unsafe abortion in Iran after pronatalist policy changes: a qualitative study. Reproductive Health. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 27];21(1):182. Available from: 10.1186/s12978-024-01929-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Weitz TA. Making sense of the economics of abortion in the united States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2024;56(3):199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.https://www.apa.org. [cited 2024 Dec 27]. Abortion bans cause outsized harm for people of color. Available from: https://www.apa.org

- 77.Rep, Kelly. M [R P 16. H.R.175–118th Congress (2023–2024): Heartbeat Protection Act of 2023. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/175

- 78.Jerman J, Frohwirth L, Kavanaugh ML, Blades N. Barriers to Abortion Care and Their Consequences For Patients Traveling for Services: Qualitative Findings from Two States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2017 [cited 2025 Apr 30];49(2):95–102. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1363/psrh.12024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Harris LH, Grossman D. Complications of Unsafe and Self-Managed Abortion. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 30];382(11):1029–40. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1908412 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Pasha AS, Sonik R, Their Body OC. Health Hum Rights. 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 30];26(1):137–42. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11197858/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.