Abstract

Background

Ovarian cancer is among the deadliest gynecological malignancies, primarily due to late-stage diagnosis and poor prognosis. Novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets are urgently needed to enhance early detection and treatment efficacy. Fc fragment of IgG-binding protein (FCGBP), a mucin-like glycoprotein, has been associated with various cancers, but its specific role in ovarian cancer progression has not been well-defined. This study aimed to investigate the clinical relevance, functional role, and underlying mechanisms of FCGBP in ovarian cancer progression.

Methods

Gene expression profiles from multiple public datasets were analyzed to identify differentially expressed genes. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was performed to correlate FCGBP expression with clinical traits. Single-cell RNA sequencing and pseudotime trajectory analyses were used to examine FCGBP expression dynamics. FCGBP expression was validated in ovarian cancer tissues using quantitative PCR, western blotting, and immunohistochemistry. Functional assays, including proliferation, migration, invasion, and colony formation, were conducted in SKOV3 and ES-2 ovarian cancer cell lines with FCGBP knockdown. The molecular mechanism was explored using dual-luciferase reporter assays and co-immunoprecipitation. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and western blotting assessed cytokine levels and pathway activation. An in vivo xenograft mouse model was used to evaluate tumorigenic effects.

Results

FCGBP expression was significantly elevated in ovarian cancer tissues and correlated with advanced tumor stage and poor prognosis. Single-cell analysis showed FCGBP expression peaked in terminally differentiated epithelial cancer cells. Silencing FCGBP significantly reduced proliferation, migration, invasion, and colony formation in vitro, and suppressed tumor growth and improved survival in vivo. Mechanistically, FCGBP enhanced interleukin-6 expression by interacting with NF-kappaB subunit p65, leading to activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Rescue experiments confirmed that exogenous interleukin-6 could restore the tumor-promoting effects lost upon FCGBP knockdown.

Conclusions

Our findings establish FCGBP as a crucial oncogenic regulator in ovarian cancer, acting through the IL-6-mediated activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. FCGBP holds promise as a novel diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target, potentially improving early diagnosis, prognosis, and management of ovarian cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-06854-z.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, FCGBP, IL-6, Cell proliferation, Therapeutic target

Background

Ovarian cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide due to its late-stage diagnosis, aggressive nature, and high recurrence rate [1, 2]. Despite advancements in surgical techniques, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies, the five-year survival rate for patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer remains disappointingly low [3]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets to improve early diagnosis, prognostic evaluation, and individualized treatment strategies for ovarian cancer patients. Fc fragment of IgG-binding protein (FCGBP) is a large mucin-like glycoprotein initially identified for its role in mucosal immunity, where it binds to the Fc region of IgG antibodies [4, 5]. Previous studies have revealed diverse, context-dependent roles for FCGBP in various cancers, and recent bioinformatic analyses suggest its overexpression and association with immune infiltration in ovarian cancer [6–9]. Recent literature indicates that FCGBP can act either as a tumor suppressor or as an oncogene, depending on the cancer type and cellular context [6, 10, 11]. However, the expression pattern, biological function, and underlying molecular mechanisms of FCGBP in ovarian cancer progression have yet to be thoroughly elucidated.

Inflammation is increasingly recognized as a hallmark of cancer, with pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) playing pivotal roles in promoting tumor growth, invasion, angiogenesis, and immunosuppression [12–15]. The IL-6/JAK-STAT signaling pathway, in particular, is crucially involved in ovarian cancer progression and correlates with poor patient outcomes [16]. In this study, we investigated the role and mechanism of FCGBP in ovarian cancer progression. We initially performed bioinformatic analyses to identify FCGBP as a significantly overexpressed gene in ovarian cancer tissues. Subsequently, we validated its functional roles both in vitro and in vivo, highlighting its oncogenic properties in ovarian cancer progression. Furthermore, we elucidated the molecular mechanism underlying FCGBP’s oncogenic functions, demonstrating its critical role in activating the IL-6/JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Our findings reveal FCGBP as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in ovarian cancer, offering novel insights into its pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions.

Results

High expression of FCGBP in ovarian cancer

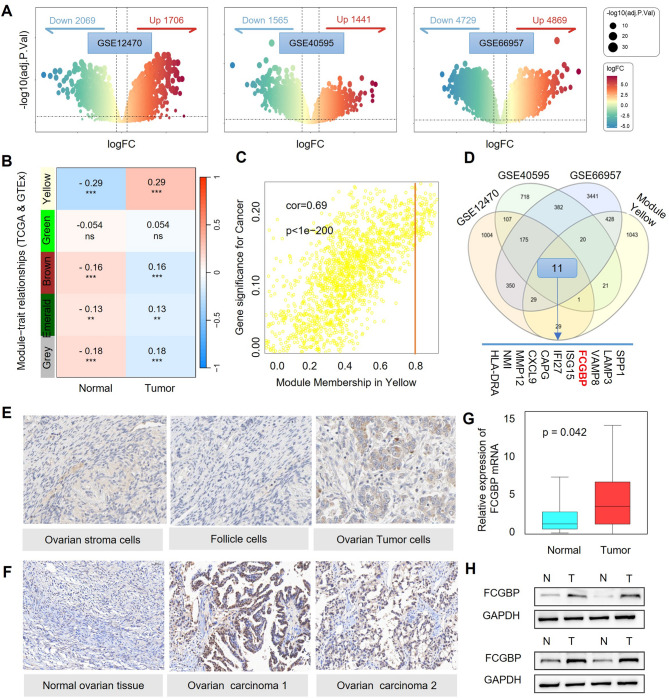

In this study, differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis was performed on three ovarian cancer-related GEO datasets (GSE12470, GSE40595, and GSE66957), identifying sets of upregulated and downregulated genes (Fig. 1A) [17, 18]. Furthermore, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was conducted by integrating TCGA-OV and GTEx datasets [19], resulting in the construction of five independent gene co-expression modules (Fig. 1B). Among these, the yellow module exhibited a strong correlation with ovarian cancer clinical characteristics (Fig. 1C). By intersecting the highly expressed genes from the three GEO datasets with the genes in the yellow module, 11 key differentially expressed genes, including FCGBP, were identified (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

High Expression of FCGBP in Ovarian Cancer. (A) Volcano plots showing DEGs in three ovarian cancer GEO datasets (GSE12470, GSE40595, GSE66957). (B-C) WGCNA identified the yellow module correlated significantly with ovarian cancer traits. (D) Venn diagram identifying 11 key genes, including FCGBP, from overlapping datasets. (E-F) Immunohistochemistry from HPA database and clinical samples showing increased FCGBP expression in ovarian cancer. (G-H) qPCR and Western blot confirming elevated FCGBP mRNA and protein levels in tumor tissues

To validate the expression of these genes in ovarian cancer tissues, we examined the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database, which confirmed that FCGBP is highly expressed in ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 1E) [20]. Consistently, using the GEPIA platform, we also validated the high expression of FCGBP in tumor tissues based on TCGA-OV and GTEx datasets (Figure S1). This trend was corroborated by immunohistochemical staining conducted in our clinical samples, further supporting higher FCGBP expression levels in serous carcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma tissues relative to normal ovarian tissues (Fig. 1F). qPCR analysis demonstrated a significant upregulation of FCGBP mRNA levels in ovarian cancer tissues (Fig. 1G), and Western blot (WB) analysis further confirmed that FCGBP protein expression was markedly elevated in ovarian cancer tissues (Fig. 1H). These findings indicate that FCGBP is highly expressed in ovarian cancer and may play a crucial role in its pathogenesis and progression.

Single-cell RNA-seq reveals FCGBP expression associated with differentiation and prognosis in ovarian cancer

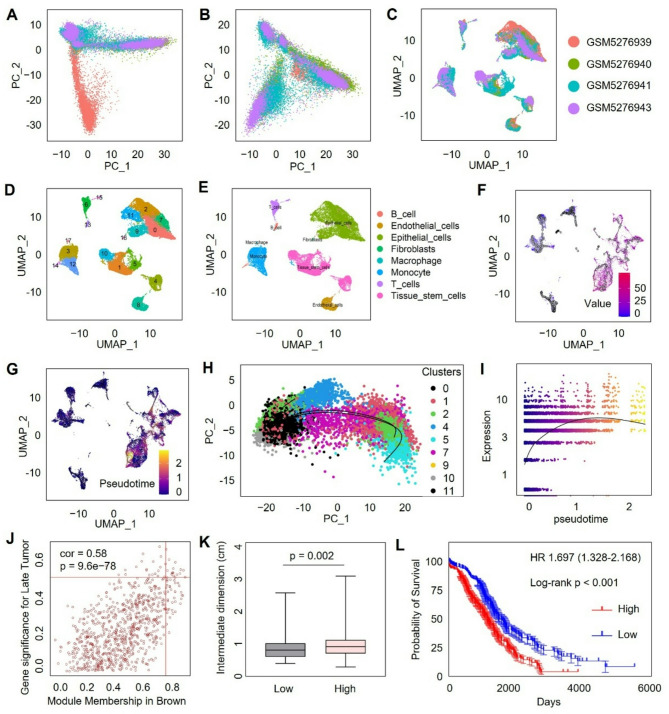

We next analyzed single-cell RNA sequencing data from ovarian cancer samples obtained from dataset GSE173682 [21]. After data integration and batch-effect correction, the single-cell transcriptomic profiles showed well-aligned cell populations, without discernible batch-dependent effects (Fig. 2A-B). Cells were then clustered into distinct groups using unsupervised clustering methods (Fig. 2C). Marker-based cell type annotation subsequently identified several major cell populations, including epithelial cells, stromal cells, immune cells, and stem-like cell populations (Fig. 2D-E). Pseudotime trajectory analysis revealed that FCGBP expression was primarily enriched in cells at terminal differentiation states (Fig. 2F-G). To further confirm this observation, epithelial and stem-like cell populations were separately extracted and subjected to additional pseudotime trajectory analysis. Consistently, FCGBP was predominantly expressed at the terminal stage of differentiation (Fig. 2H). Further analysis demonstrated a gradual increase in FCGBP expression level as pseudotime progressed, supporting its potential role in cellular differentiation and maturation (Fig. 2I). Moreover, WGCNA was performed again using the GSE12470 dataset, which includes both early-stage and advanced-stage ovarian cancer samples (Figure S2). The analysis identified the brown module as strongly correlated with advanced ovarian cancer, and notably, FCGBP was found to reside within this module, implying its relationship with advanced tumor progression (Fig. 2J). Clinical correlation analyses revealed significantly larger tumor sizes in samples with high FCGBP expression compared to low-expression counterparts, suggesting that its upregulation in terminally differentiated cancer cells may represent a molecular switch that drives aggressive behavior (Fig. 2K). Additionally, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed significantly poorer survival outcomes in patients with high FCGBP expression, underscoring its prognostic significance in ovarian cancer (Fig. 2L). Collectively, these data highlight FCGBP as a marker highly expressed at differentiated states of ovarian cancer cells and further emphasize its potential involvement in ovarian cancer progression.

Fig. 2.

Single-cell Analysis Reveals FCGBP Expression Patterns and Clinical Correlation in Ovarian Cancer. (A-C) Integration and batch-effect correction of single-cell RNA-seq data from dataset GSE173682. (D-E) UMAP plots showing cell clustering and marker-based annotation of distinct cell populations. (F-G) Pseudotime trajectory analysis highlighting enrichment of FCGBP expression in differentiated cell states, particularly epithelial and stem cell clusters. (H-I) FCGBP expression increases with pseudotime progression. (J) WGCNA analysis using GSE12470 dataset identifies FCGBP within the brown module significantly associated with advanced ovarian cancer. (K-L) High FCGBP expression correlates with increased tumor size and poor patient survival

Knockdown of FCGBP reduces proliferation, invasion, and migration of ovarian cancer cells

To investigate the functional role of FCGBP in ovarian cancer, we performed a series of in vitro assays using two ovarian cancer cell lines, SKOV3 and ES-2. CCK-8 proliferation assays revealed that silencing FCGBP significantly reduced cell viability compared with the control group, indicating that FCGBP promotes ovarian cancer cell proliferation (Fig. 3A-B). Further analysis using a 3D sphere formation assay demonstrated that FCGBP knockdown markedly inhibited spheroid formation and reduced spheroid diameter, suggesting a role for FCGBP in maintaining the tumor-initiating capabilities of ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 3C-D). Additionally, colony formation assays showed decreased clonogenic capacity upon FCGBP suppression, further confirming its oncogenic properties in ovarian cancer (Fig. 3E-F).

Fig. 3.

Knockdown of FCGBP Inhibits Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation, Tumorigenicity, Invasion, and Migration. (A-B) CCK-8 assays showing decreased proliferation in SKOV3 and ES-2 cells upon FCGBP silencing. (C-D) 3D tumorsphere formation assays demonstrating reduced sphere-forming ability after FCGBP knockdown. (E-F) Colony formation assays revealing significantly fewer colonies formed by FCGBP-silenced cells compared to controls. (G-H) Transwell invasion assays indicating that FCGBP inhibition significantly impairs ovarian cancer cell invasion. (I-J) Wound-healing assays showing decreased migration in FCGBP-silenced ovarian cancer cells

To assess the impact of FCGBP on ovarian cancer cell invasion and migration, we performed transwell and wound healing assays. The results indicated that silencing FCGBP significantly attenuated cell invasion abilities in both SKOV3 and ES-2 cell lines (Fig. 3G-H). Similarly, wound healing assays demonstrated decreased migratory potential following FCGBP inhibition, confirming the critical role of FCGBP in ovarian cancer cell migration (Fig. 3I-J). Taken together, these findings provide strong evidence that FCGBP promotes ovarian cancer cell proliferation, invasion, migration, and tumor-initiating potential, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target.

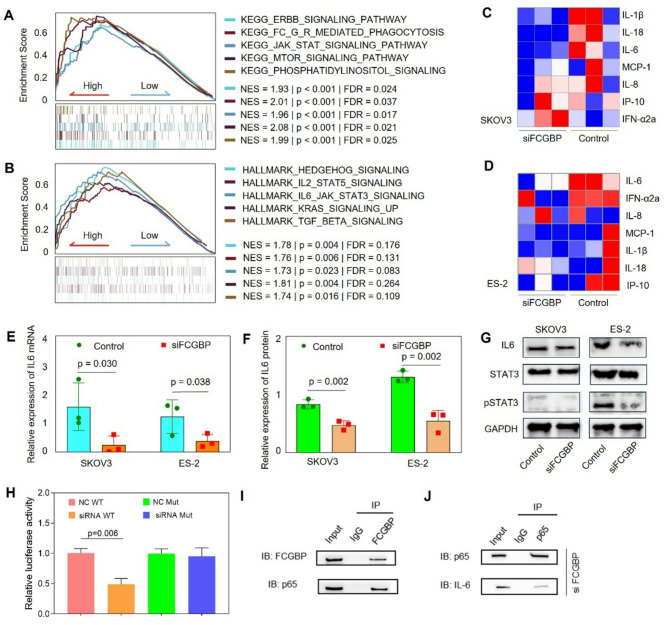

FCGBP enhances ovarian cancer progression via activation of the IL-6/JAK-STAT signaling pathway

To elucidate the downstream mechanisms mediated by FCGBP in ovarian cancer, we performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) using KEGG and HALLMARK sets [22]. The results indicated significant enrichment of inflammatory pathways, especially the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, in samples exhibiting high FCGBP expression (Fig. 4A-B). To further confirm these findings, we analyzed those inflammatory cytokine levels, revealing a notable reduction in IL-6 levels upon FCGBP knockdown (Fig. 4C-D). Consistent with these results, qPCR and ELISA analyses confirmed that FCGBP suppression significantly decreased IL-6 expression at both the mRNA and protein secretion levels in SKOV3 and ES-2 cell lines (Fig. 4E-F). Additionally, Western blot analyses demonstrated that inhibition of FCGBP significantly reduced the phosphorylation of STAT3 without affecting total STAT3 protein expression (Fig. 4G). Given that FCGBP is not a classical transcription factor and lacks known DNA-binding domains, we hypothesized that FCGBP might exert its regulatory effect on IL-6 expression through interaction with transcription factors. Notably, prior studies have established that NF-κB (particularly the p65 subunit) is a major transcriptional regulator of IL-6 expression [23, 24]. To examine the mechanism of IL-6 regulation, we performed a dual-luciferase reporter assay using wild-type and NF-κB-mutant IL-6 promoter constructs. We found that FCGBP suppression decreased IL-6 promoter activity, and that this effect was abolished when the NF-κB binding site on the promoter was mutated (Fig. 4H). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation (IP) assays confirmed that FCGBP physically interacts with the NF-κB p65 subunit (Fig. 4I), and Reciprocal Co-IP using anti-p65 also confirmed the interaction between p65 and FCGBP, supporting their cooperative role in transcriptional regulation of IL-6 (Fig. 4J). These findings suggest that FCGBP enhances IL-6 expression via interaction with NF-κB, thereby activating the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway to promote ovarian cancer progression.

Fig. 4.

FCGBP Promotes Ovarian Cancer Progression via IL-6/JAK-STAT Pathway Activation. (A-B) GSEA analysis using KEGG and HALLMARK databases indicating enrichment of inflammation-related pathways, especially the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, in FCGBP-high expression samples. (C-D) Heatmaps of inflammatory cytokine expression profiles in SKOV3 and ES-2 cells after FCGBP knockdown. (E-F) qPCR and ELISA confirming significant decreases in IL-6 mRNA expression and protein secretion upon FCGBP silencing. (G) Western blot analysis of IL-6, STAT3 and pSTAT3 following FCGBP inhibition. (H) Dual-luciferase reporter assay using wild-type and NF-κB-binding-site-mutated IL-6 promoter constructs. (I-J) Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays demonstrating the physical interaction between FCGBP and NF-κB p65 (I), and reciprocal Co-IP showing co-enrichment of p65 and IL-6 with FCGBP (J). IgG was used as a negative control

IL-6 treatment rescues ovarian cancer cell functions impaired by FCGBP knockdown

To further validate the role of IL-6 in mediating FCGBP’s effects on ovarian cancer progression, we performed rescue experiments by treating FCGBP-silenced SKOV3 cells with recombinant IL-6. CCK-8 assays demonstrated that IL-6 supplementation significantly restored cell viability impaired by FCGBP knockdown (Fig. 5A). Similarly, 3D sphere formation assays indicated that IL-6 treatment markedly rescued the spheroid-forming ability and increased spheroid diameter compared to FCGBP knockdown alone (Fig. 5B-C). Colony formation assays further confirmed that IL-6 could significantly reverse the inhibitory effects of FCGBP knockdown on clonogenic capability (Fig. 5D-E). Additionally, transwell invasion and wound healing assays showed that IL-6 treatment effectively restored the invasive and migratory capacities of ovarian cancer cells reduced by FCGBP suppression (Fig. 5F-I). Taken together, these findings clearly indicate that IL-6 plays a pivotal role in mediating FCGBP-driven proliferation, invasion, and migration in ovarian cancer cells, underscoring the therapeutic potential of targeting the FCGBP/IL-6 signaling axis.

Fig. 5.

IL-6 rescues FCGBP knockdown-induced inhibition of ovarian cancer cell functions. (A) CCK-8 assay demonstrating that IL-6 supplementation rescues cell proliferation impaired by FCGBP knockdown in SKOV3 cells. (B-C) 3D tumorsphere assay showing IL-6 significantly restores spheroid formation inhibited by FCGBP silencing. (D-E) Colony formation assay indicating IL-6 treatment reverses the inhibitory effects of FCGBP knockdown on clonogenic ability. (F-G) Transwell invasion assay confirming IL-6 supplementation rescues cell invasion reduced by FCGBP silencing. (H-I) Wound-healing assay illustrating that IL-6 treatment partially restores cell migration impaired by FCGBP knockdown

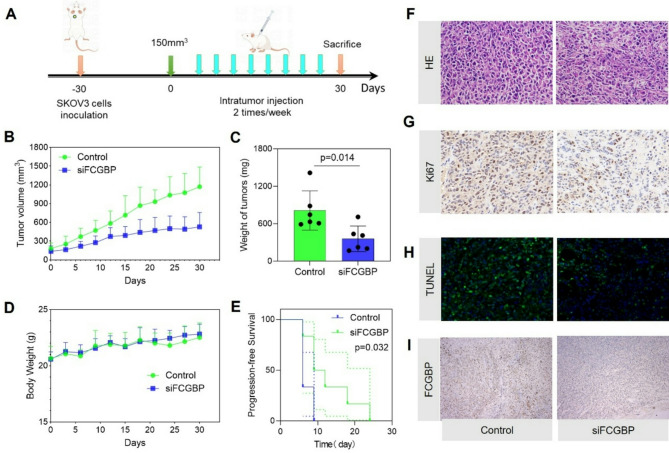

Knockdown of FCGBP inhibits tumor growth and prolongs survival in ovarian cancer xenograft model

To validate our in vitro findings in vivo, we established a xenograft ovarian cancer mouse model by inoculating SKOV3 cells into nude mice, followed by intratumoral injections of FCGBP-targeted siRNA or control siRNA (Fig. 6A). Tumor volume measurements showed that FCGBP knockdown significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to controls (Fig. 6B). Additionally, the final tumor weight was markedly reduced in the FCGBP-silenced group compared with the control group (Fig. 6C), with no significant difference in body weight between the groups, indicating minimal systemic toxicity (Fig. 6D). Progression-free survival analysis further demonstrated significantly prolonged survival in mice treated with FCGBP siRNA compared to control mice (Fig. 6E). Histological examination revealed reduced tumor cellularity and more apoptosis in FCGBP-silenced tumors. Immunohistochemical analysis showed decreased proliferation marker Ki-67 expression and increased apoptotic cells indicated by TUNEL staining in the FCGBP knockdown group (Fig. 6F-H). Immunostaining confirmed effective knockdown of FCGBP protein in treated tumors (Fig. 6I). These results collectively confirm that targeting FCGBP significantly suppresses ovarian cancer progression in vivo, supporting its potential as a promising therapeutic target for ovarian cancer treatment.

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of FCGBP Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Growth In Vivo. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure for SKOV3 ovarian cancer xenografts in nude mice. (B-C) Tumor growth curves and final tumor weights demonstrating significant inhibition of tumor growth upon FCGBP knockdown. (D) Body weight monitoring showing no significant difference between control and FCGBP-silenced groups. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis indicating prolonged progression-free survival in mice treated with FCGBP siRNA. (F-I) Representative histological and immunohistochemical analyses showing reduced cellularity (HE staining), decreased proliferation (Ki67), increased apoptosis (TUNEL), and effective FCGBP silencing in tumors

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that FCGBP is significantly overexpressed in ovarian cancer and plays a crucial role in promoting ovarian cancer progression. Specifically, we found that high FCGBP expression enhances proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumor-initiating capabilities of ovarian cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, we revealed that FCGBP facilitates ovarian cancer progression primarily through the activation of the IL-6/JAK-STAT signaling pathway.

Previous studies have suggested diverse roles for FCGBP in various malignancies. For example, FCGBP has been reported to exhibit tumor-suppressive roles in colorectal cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, while its elevated expression correlates with poor prognosis in gallbladder cancer [25–27]. These opposing roles likely reflect context-specific molecular interactions and signaling environments. In ovarian cancer, our data suggest that FCGBP promotes tumor progression by cooperating with NF-κB p65 to enhance IL-6 transcription, thereby activating downstream JAK/STAT signaling. This interaction may not occur in other epithelial tissues. Differences in tumor microenvironment, FCGBP isoforms, post-translational modifications, and binding partners may all contribute to this divergent behavior. Identifying FCGBP as a critical factor in ovarian cancer progression highlights its potential as a valuable biomarker and therapeutic target.

IL-6-mediated JAK-STAT signaling has been widely documented as critical in tumor progression, immune evasion, and metastasis across numerous cancer types, including ovarian cancer [28–30]. Here, we showed that silencing FCGBP significantly reduced IL-6 expression and suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation, suggesting that FCGBP functions as an upstream regulator of the IL-6/JAK-STAT pathway. This pathway’s activation is well-known for promoting tumor growth, survival, angiogenesis, and immune modulation [31–33]. Hence, our findings highlight FCGBP’s pivotal role in modulating this critical signaling axis and provide a rationale for targeting FCGBP to interrupt IL-6-dependent tumor-promoting signals. Mechanistically, our findings reveal that FCGBP enhances IL-6 transcription not by directly binding the IL-6 promoter, but through physical interaction with the NF-κB p65 subunit. This novel mechanism positions FCGBP upstream of canonical IL-6 signaling and provides a molecular explanation for sustained IL-6 production in the tumor microenvironment. Beyond its direct regulation of IL-6, FCGBP likely integrates into broader oncogenic signaling networks. The IL-6/STAT3 axis is regulated by various factors including IL-1β, NF-κB, and suppressors such as SOCS1/3 [34]. Our data suggest FCGBP cooperates with NF-κB to sustain pro-tumor inflammation. Moreover, as a secreted glycoprotein with adhesion-related domains, FCGBP may intersect with pathways like PI3K/AKT, EMT, and TGF-β, which are central to ovarian cancer progression. Importantly, persistent IL-6/STAT3 activation is known to mediate immune suppression via myeloid-derived suppressor cell recruitment and T cell dysfunction [35]. Thus, FCGBP may contribute to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment-an area warranting further study.

Single-cell RNA sequencing further supports the clinical relevance of FCGBP. We observed that its expression increases along the pseudotime differentiation trajectory and is enriched in terminally differentiated epithelial cancer cells. While terminal differentiation typically implies reduced proliferation in normal tissue, in tumors, it may reflect a phenotypic switch toward more invasive, immune-evasive states. This aligns with our in vitro and in vivo data showing that high FCGBP expression confers enhanced oncogenic behavior, and with our clinical analyses linking FCGBP expression to tumor size and worse survival outcomes.

Our study provides the first comprehensive evidence of FCGBP’s function and mechanistic involvement in ovarian cancer progression. The functional validation, including rescue experiments and animal models, further strengthens the evidence for FCGBP as an actionable therapeutic target. Thus, targeting FCGBP represents a promising therapeutic approach for ovarian cancer. Mechanistically, FCGBP enhances IL-6 transcription through NF-κB and interacts directly with p65. This finding not only advances mechanistic insight into the upstream regulation of IL-6 but also suggests that FCGBP functions as a co-regulator of pro-inflammatory transcriptional programs that fuel tumorigenesis. Clinically, these findings have translational implications. Although no inhibitors directly targeting FCGBP have yet been developed, its structural features and extracellular nature render it a potentially druggable protein. FCGBP is a large secreted mucin-like glycoprotein containing multiple von Willebrand D domains and cysteine-rich adhesion modules, which may serve as epitope targets for antibody-based therapeutics [36]. Its extracellular localization makes it particularly suitable for monoclonal antibody or nanobody-based interventions. Combining FCGBP inhibition with existing IL-6, JAK, or STAT3 inhibitors may further enhance antitumor efficacy. Considering that FCGBP expression correlates with poor prognosis and advanced disease, it also holds promise as a biomarker for risk stratification or therapeutic response prediction. Future translational work should focus on functional epitope mapping, generation of neutralizing antibodies or blocking peptides, and in vivo evaluation of FCGBP-targeted therapies in preclinical ovarian cancer models.

Conclusions

Our study identifies FCGBP as a crucial regulator in ovarian cancer progression through the IL-6/JAK-STAT signaling pathway. These findings provide novel insights into ovarian cancer biology and highlight FCGBP as a promising therapeutic target, opening new avenues for improved clinical management of ovarian cancer.

Methods

Ovarian cancer specimens

All procedures involving human participants in this study were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (Approval No. IRB-2021-124). A total of 40 epithelial ovarian cancer tissue samples and 20 normal ovarian tissue samples were collected from Zhejiang Cancer Hospital between June 2021 and December 2022 for FCGBP detection.

Bioinformatic analysis

Microarray gene expression datasets relevant to ovarian cancer were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, including GSE12470, GSE40595, and GSE66957. GSE12470 includes expression data from early- and advanced-stage ovarian tumors; GSE40595 contains data from primary tumors and matched normal tissues; GSE66957 provides gene profiles across multiple ovarian cancer histological subtypes. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between ovarian cancer tissues and normal controls were identified using R with cutoffs set at adjusted p-value < 0.05 and|log2 fold-change| >1.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

WGCNA was performed using the “WGCNA” R package (version 1.71) on normalized RNA-seq data from the TCGA-OV and GTEx normal ovary datasets. A soft-thresholding power was selected based on scale-free topology criteria, and hierarchical clustering was used to detect gene co-expression modules. Module–trait relationships were calculated by correlating module eigengenes with clinical phenotypes.

Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis

Single-cell transcriptomic data (GSE173682) were analyzed using Seurat (version 4.3.0) for normalization, scaling, and batch-effect correction. Cells were clustered using the Louvain algorithm and visualized via UMAP. Cell types were annotated based on canonical markers. Pseudotime trajectory analysis was conducted using Monocle3 (version 1.2.9) to infer cellular differentiation states. FCGBP expression was mapped along the pseudotime continuum.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was conducted using the “clusterProfiler” R package (version 4.6.0) with gene sets from the KEGG and Hallmark (MSigDB) collections. Genes were ranked based on log fold change between FCGBP-high and FCGBP-low groups. Enrichment scores and false discovery rates (FDR) were computed to assess pathway significance.

Cell culture and transfection

The ovarian cancer cell lines SKOV3 and ES-2 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Both SKOV3 and ES-2 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco), and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For transient knockdown experiments, cells were transfected with specific siRNAs targeting FCGBP or negative control siRNA using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each transfection experiment was performed independently in triplicate.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Japan). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression levels were calculated using the comparative Ct method (2 − ΔΔCt), with GAPDH as an internal control. All experiments were conducted independently at least three times.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Culture supernatants were collected from ovarian cancer cells 48 h after transfection. IL-6 protein concentrations were quantified using a human IL-6 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were measured in triplicate, and experiments were repeated independently three times.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The human IL-6 promoter sequence (wild-type or with mutations at the NF-κB binding site) was cloned into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega, USA). SKOV3 cells were co-transfected with the IL-6 promoter reporter plasmid and either siFCGBP or control vector using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, USA). A Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL-TK) was co-transfected as an internal control. After 36 h, luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

SKOV3 cells were lysed in IP lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) containing protease inhibitors. Cell lysates were pre-cleared and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-FCGBP antibody (Proteintech) or anti-p65 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by incubation with Protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 2 h. After washing, the immune complexes were eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using specific antibodies against FCGBP and p65. Normal IgG served as a negative control.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, transfected cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2,000 cells/well) and incubated for indicated time points. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, USA).

Colony formation assay

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 800 cells/well and cultured for two weeks. Colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and counted under microscopy. Each assay was independently repeated three times.

Transwell invasion assay

Transfected cells were seeded into the upper chambers of Transwell inserts (Corning, USA) coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA). The lower chambers were filled with medium containing 10% FBS. After 24 h, cells invading through the membrane were fixed, stained, and counted in five randomly selected fields under microscopy.

Wound-healing assay

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and allowed to reach confluence. A linear scratch was created using a sterile 200 µL pipette tip. Cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with serum-free medium. Wound closure was observed and photographed at indicated time points.

Animal experiments

Female nude mice (BALB/c-nu, 4–5 weeks old) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center (Shanghai, China). SKOV3 cells (5 × 106) were subcutaneously injected into nude mice. When tumors reached approximately 150 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to groups and received intratumoral injections of FCGBP-targeted siRNA or control siRNA twice weekly for four weeks. Tumor volume and mouse body weight were measured regularly. Tumors were harvested, weighed, and processed for histological and immunohistochemical analyses. All animal experiments complied with institutional animal care guidelines and were approved by the Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was analyzed using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA. Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1: Expression levels of FCGBP in ovarian cancer tissues compared with normal ovarian tissues based on GEPIA analysis.

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2: WGCNA analysis identifying key gene modules associated with ovarian cancer progression.

Acknowledgements

No additional acknowledgement.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: ZQ F and C L. Study conduct: ZQ F, KL C, F Z. Data analysis: WG G and C L. Manuscript preparation: ZQ F and D C.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Medical and Health Research Project of Zhejiang Province (2022KY626, 2023KY499). National Natural Science Foundation of China (82303377).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (Approval No. IRB-2021-124).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Whitwell HJ, Worthington J, Blyuss O, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, Gunu R, Kalsi J, Menon U, Jacobs I, Zaikin A, Timms JF. Improved early detection of ovarian cancer using longitudinal multimarker models. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:847–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuroki L, Guntupalli SR. Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. BMJ. 2020;371:m3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jing L, Gong M, Lu X, Jiang Y, Li H, Cheng W. LINC01127 promotes the development of ovarian tumors by regulating the cell cycle. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:406–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang JJ, Zhang Y, Chen Q, Chen QN, Yang X, Zhu XL, Hao CY, Duan HB. A novel prognostic marker and therapeutic target associated with glioma progression in a tumor immune microenvironment. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:895–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suo Y, Hou C, Yang G, Yuan H, Zhao L, Wang Y, Zhang N, Zhang X, Lu W. Fc fragment of IgG binding protein is correlated with immune infiltration levels in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomol Biomed. 2023;23:605–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Gong Z, Liu J, Wang W, Liu K, Yang Y, Lu X, Wang J. Fc fragment of IgG binding protein suppresses tumor growth by stabilizing wild type P53 in colorectal cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2025;25:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin Y-H, Yang Y-F, Shiue Y-L. Multi-omics analyses to identify FCGBP as a potential predictor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Diagnostics. 2022;12:1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu R, Ge N, Huang B, Fu J, Zhang Y, Wang N, Xu Y, Li L, Peng X, Zou Y, et al. Impacts of vitrification on the transcriptome of human ovarian tissue in patients with gynecological cancer. Front Genet. 2023;14:1114650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun X, He W, Lin B, Huang W, Ye D. Defining three ferroptosis-based molecular subtypes and developing a prognostic risk model for high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Aging. 2024;16:9106–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng L, Zeng J, He J, Li Y, Li C, Lin Z, Chen G, Wu H, Zhou L. FCGBP functions as a tumor suppressor gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Discover Oncol. 2024;15:704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu H, Zhang Q, Song H, Tang J, Fu J, Wang X. FcGBP was upregulated by HPV infection and correlated to longer survival time of HNSCC patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:86503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao H, Wu L, Yan G, Chen Y, Zhou M, Wu Y, Li Y. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Target Therapy. 2021;6:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumari N, Dwarakanath B, Das A, Bhatt AN. Role of interleukin-6 in cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. Tumor Biology. 2016;37:11553–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamed AH, Ahmed AT, Al Abdulmonem W, Bokov DO, Shafie A, Al-Hetty HRAK, Hsu C-Y, Alissa M, Nazir S, Jamali MC. Interleukin-6 serves as a critical factor in various cancer progression and therapy. Med Oncol. 2024;41:182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu S, Cao Z, Lu R, Zhang Z, Sethi G, You Y. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)-associated tumor microenvironment remodelling and cancer immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2025. Jan 10:S1359-6101(25)00001-2. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mir MA, Bashir M, Jan N. The role of Interleukin (IL)-6/IL-6 receptor Axis in Cancer. Cytokine and chemokine networks in Cancer. Springer 2023;137–64.

- 17.Yoshihara K, Tajima A, Komata D, Yamamoto T, Kodama S, Fujiwara H, Suzuki M, Onishi Y, Hatae M, Sueyoshi K, et al. Gene expression profiling of advanced-stage serous ovarian cancers distinguishes novel subclasses and implicates ZEB2 in tumor progression and prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1421–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeung TL, Leung CS, Wong KK, Samimi G, Thompson MS, Liu J, Zaid TM, Ghosh S, Birrer MJ, Mok SC. TGF-β modulates ovarian cancer invasion by upregulating CAF-derived versican in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5016–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regner MJ, Wisniewska K, Garcia-Recio S, Thennavan A, Mendez-Giraldez R, Malladi VS, Hawkins G, Parker JS, Perou CM, Bae-Jump VL, Franco HL. A multi-omic single-cell landscape of human gynecologic malignancies. Mol Cell. 2021;81:4924–e49414910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brasier AR. The nuclear factor-kappaB-interleukin-6 signalling pathway mediating vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:211–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H, Qi H, Ren J, Cui J, Li Z, Waldum HL, Cui G. Involvement of NF-κB/IL-6 pathway in the processing of colorectal carcinogenesis in colitis mice. Int J Inflamm 2014;2014:130981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wang J, Gong Z, Liu J, Wang W, Liu K, Yang Y, Lu X, Wang J. Fc fragment of IgG binding protein suppresses tumor growth by stabilizing wild type P53 in colorectal cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2025;25:507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng L, Zeng J, He J, Li Y, Li C, Lin Z, Chen G, Wu H, Zhou L. FCGBP functions as a tumor suppressor gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Discov Oncol. 2024;15:704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong L, Wen Y, Miao X, Yang Z. NT5E and FcGBP as key regulators of TGF-1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) are associated with tumor progression and survival of patients with gallbladder cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355:365–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.To K, Chan M, Leung W, Ng E, Yu J, Bai A, Lo A, Chu S, Tong J, Lo K. Constitutional activation of IL-6-mediated JAK/STAT pathway through hypermethylation of SOCS-1 in human gastric cancer cell line. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1335–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang B, Lang X, Li X. The role of IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in cancers. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1023177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Reviews Clin Oncol. 2018;15:234–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang M, Wu S, Cai W, Ming X, Zhou Y, Chen X. Hypoxia-induced MIF induces dysregulation of lipid metabolism in Hep2 laryngocarcinoma through the IL-6/JAK-STAT pathway. Lipids Health Dis. 2022;21:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia Castellano JM, García-Padrón D, Martínez-Aragón N, Ramírez-Sánchez M. Vera Gutiérrez VJ, Fernández Pérez LF: role of the IL-6/Jak/Stat pathway in tumor angiogenesis. Influence of Estrogen Status 2022.

- 33.Servais FA, Kirchmeyer M, Hamdorf M, Minoungou NW, Rose-John S, Kreis S, Haan C, Behrmann I. Modulation of the IL-6-signaling pathway in liver cells by MiRNAs targeting gp130, JAK1, and/or STAT3. Mol Therapy Nucleic Acids. 2019;16:419–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, Wormald S, Willson TA, Stanley EG, Robb L, Greenhalgh CJ, Förster I, Clausen BE, et al. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:540–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Masuda K, Kishimoto T. Regulation of IL-6 in immunity and diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;941:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehrencrona E, Gallego P, Trillo-Muyo S, Garcia-Bonete M-J, Recktenwald CV, Hansson GC, Johansson MEV. The structure of FCGBP is formed as a disulfide-mediated homodimer between its C-terminal domains. FEBS J. 2025;292:582–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1: Expression levels of FCGBP in ovarian cancer tissues compared with normal ovarian tissues based on GEPIA analysis.

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2: WGCNA analysis identifying key gene modules associated with ovarian cancer progression.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.