Abstract

Introduction

Known for its neuroprotective properties, the ketogenic diet (KD) recently has been shown to prevent weight loss induced by chronic stress in rats, although the mechanisms remain to be elucidated. The obesity-resistant BALB/c mouse is susceptible to chronic stress–induced weight loss, providing a useful model to study the interactions between diet and stress.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the potential of a ketogenic diet to prevent chronic stress-induced weight loss in the obesity-resistant BALB/c mouse strain.

Method

BALB/c mice of both sexes, were divided into groups: (1) standard chow, (2) KD, (3) standard chow + stress, and (4) KD + stress. The stress groups were subjected to a restraint stress protocol for 23 d, 4 h a day. Morphometric changes, glucose tolerance, plasmatic corticosterone levels, and circulating ketone bodies were evaluated.

Results

Levels of β-hydroxybutyrate increased in the KD group in both sexes. However, under stress, the increase in ketone bodies was lower in female mice. Compared with standard chow-fed groups, females on a KD gained significant body weight, an effect lost in females under stress, with decreasing fat tissue deposits. In male mice, although no changes in body weight were observed in the KD group, the mass of adipose tissue depots increased and remained unchanged under stress. Under chronic stress both standard chow and KD-fed mice lost weight. Under KD, female and male BALB/c mice exhibited decreased water and food intake, as well as reduced glucose tolerance, under resting and chronic stress conditions.

Conclusions

There is an interplay between chronic stress and ketogenic metabolism in BALB/c mice. In female mice, chronic stress interferes with ketogenesis, lowering beta-hydroxybutyrate levels and preventing weight gain whereas the KD inhibits chronic stress-induced glucose tolerance, this in a sex-dependent manner.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40795-025-01129-8.

Keywords: Chronic stress, Ketogenic diet, Β-hydroxybutyrate, Obesity-resistance, Glucose tolerance, Sex-dependent

Introduction

Chronic stress is considered a negative emotional experience with the potential to disrupt the body’s homeostasis. The dysregulation of this homeostasis due to stressors plays a role in the development of various pathologies, such as infections, metabolic imbalances, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer [1]. It is known that stress activates the nervous system, triggering the sympathetic-adreno-medullary (SAM) pathway and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, releasing hormones such as catecholamines and glucocorticoids, which chronically impact individuals’ health [2]. Recently, due to the neuroprotective properties attributed to the consumption of a ketogenic diet (KD) [3–5], as well as the ability of ketone bodies to cross the blood-brain barrier to supply energy to the brain, the modulatory role of this diet under chronic conditions such as stress has been questioned.

The KD, widely used as a treatment for neurodegenerative diseases such as epilepsy, is considered a high-fat diet with an appropriate protein content and restricted carbohydrates, forcing the body to alter its metabolism by maintaining a ketogenic state due to high levels of ketone bodies in the blood [6, 7]. It has been reported that the administration of a KD has protective effects on mood disorders, reduction of glucose levels, improved insulin sensitivity, anti-inflammatory properties, and body weight loss [8–11]. The effects of KD, such as body weight loss, are attributed to metabolic adjustments involving adrenergic receptors [12]. Similarly, a direct relationship between ketone bodies and the regulation of the nervous system, controlling the body’s energy expenditure for the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis has been reported, placing the nervous system as a mediator of the effects of the KD on body weight [13, 14].

Due to the neuroprotective properties attributed to the consumption of the KD [3–5], the modulating role that this diet might have in chronic conditions such as stress has been investigated. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that a ketogenic diet has beneficial effects in individuals who consume it regularly, improving mood, mental well-being, and cognitive function while reducing stress, depression, and anxiety compared to those following other types of diets [15].

Limited studies show that consuming a ketogenic diet (KD) prevents the effects of chronic stress, particularly body weight loss [16]. In addition, it has been reported that under acute stress conditions, circulating ketone bodies increase [17, 18], thereby attenuating the stress-induced rise in inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNFα [19, 20]. Despite the widespread use of the KD, the regulatory mechanism of its effects under chronic stress conditions has not yet been elucidated.

Recently, a study evaluating sex- and age-related differences in mice on a ketogenic diet, observed glucose intolerance in males and increased adiposity in females [21]. In the last decade, increasing importance has been given to conducting research on both sexes. In the past, many studies were performed primarily on males to avoid the variability introduced by the estrous cycle and female sex hormones [22]. To ensure that these findings are useful for understanding the effects of KD consumption in humans, it is essential to investigate the impact of the ketogenic diet in both sexes.

The present study aims to evaluate the potential of a KD to prevent chronic stress-induced weight loss in the obesity-resistant BALB/c mouse, circulating ketone bodies, weight gain, adipose tissue deposits, feeding behavior, and glucose tolerance were assessed. Our findings shed light on the interaction between chronic stress and ketogenic metabolism in a widely used lab mouse strain, as well as their differential effect by sex.

Methods

Animals

We used 12- to 16-week-old BALB/c mice of both sexes obtained from the bioterium of the Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas at Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL), México. Mice were provided with food and water ad libitum and housed in controlled microenvironmental conditions of 12 h:12 h light: dark cycles with controlled temperature ranging between 22 and 25 °C and 45% relative humidity.

All experimental procedures in animals were approved by the Research Ethics and Animal Welfare Committee of Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, UANL (CEIBA-2021-002).

Experimental design

To reduce stress induced by handling, animals were daily handled for five minutes by the same operator. They were randomly divided into the following groups: males; standard chow (n = 5), standard chow + stress (n = 5), KD (n = 5), and KD + stress (n = 4) and females; standard chow (n = 10), standard chow + stress (n = 8), KD (n = 5), and KD + stress (n = 5). Mice were subjected to daily restraint stress for four hours during 23 d. For this procedure, mice were individually placed in well-ventilated 50 mL conical tubes [23]. Standard chow consisted of 13% fat, 28% protein, and 57% carbohydrate (LabDiet 5001, 2.86 kcal g, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO, USA), whereas the KD consisted of 80% fat, 15% protein, and 5% carbohydrates (Research Diets D06040601, 6.1 kcal g; Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) [24, 25]. Food and water intake were assessed through the protocol. Mouse body weight was measured every two days, using a digital scale.

Glucose tolerance test

On day 23 of the protocol, we assessed glucose tolerance [26]. Mice were fasted for six hours, blood was collected from the tip of the tail and baseline blood glucose was measured using a glucometer (Trividia Health Inc., Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA) (time 0). Next, a 100 mg/mL glucose solution (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH, USA) in sterile saline solution, was administered by intraperitoneal injection. Blood glucose was measured at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min post-glucose injection. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the glucose time-course data.

β-hydroxybutyrate plasma levels

Before euthanizing the animals, changes in blood β-hydroxybutyrate levels (BHB), the primary circulating ketone bodies, were determined by measuring the blood ketone body concentration immediately after blood collection, using the KetoSens™ test strips (i-SENS, Seoul, Korea), following manufacturer´s instructions.

Tissue sampling

At the end of the experiment, mice were anesthetized with a dose of 100 mg/Kg pentobarbital (Aranda, Mexico) and terminal cardiac puncture was conducted to obtain blood samples, after which animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The interscapular, inguinal, and visceral adipose tissue deposits were removed, weighed on an analytical scale, and stored at -80 ºC until analysis. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the body weight by the square of the nose-anus length at the end of the experiment.

Plasma corticosterone

To determine HPA activation an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Parameter Corticosterone Assay KGE009, R&D Systems) was conducted to quantify plasmatic corticosterone levels, following the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were analyzed in duplicate to ensure accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Water and food intake, BMI, ketone body levels, AUC, corticosterone levels, and percentage of adipose tissue depots were first analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by planned multiple comparisons. If significant results were obtained, a Bonferroni post-hoc test was performed. Body weight and glucose tolerance test were assessed by two-way ANOVA, if significant results were obtained, a Tukey post-hoc test was performed. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

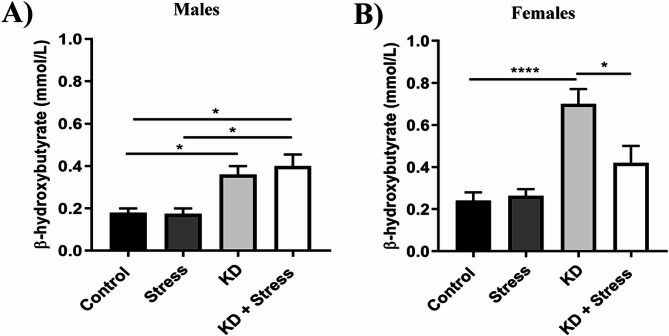

Plasma β - hydroxybutyrate levels

β-hydroxybutyrate levels were measured to assess the activation of ketogenesis when consuming a ketogenic diet (males, n = 4–5 mice / group; females, n = 5–10 mice / group). In males consuming a KD, an increase in BHB levels was observed both under resting (0.3 mmol/L, p = 0.0474) and chronic stress (0.4 mmol/L, p = 0.0269) conditions (Fig. 1A). In contrast, although females consuming KD also showed an increase in BHB levels (0.7 mmol/L, p = 0.0001); in those subjected to chronic stress, the increase was significantly reduced (0.42 mmol/L, p = 0.0149) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of the KD on BHB levels in BALB/c mice under conditions of rest and chronic stress. Mice consumed a standard diet or a KD for 23 d. On day 23 of the protocol, we evaluated blood ketone bodies. Levels of BHB in blood in (A) male and (B) female mice of the BALB/c strain at day 23 under a KD and chronic stress. In BALB/c mice on a KD, blood ketone body levels increased, under stress or resting conditions. However, in females, ketone body levels were lower under chronic stress conditions; n = 4–10 mice/ group. Data represent the mean ± standard error. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant

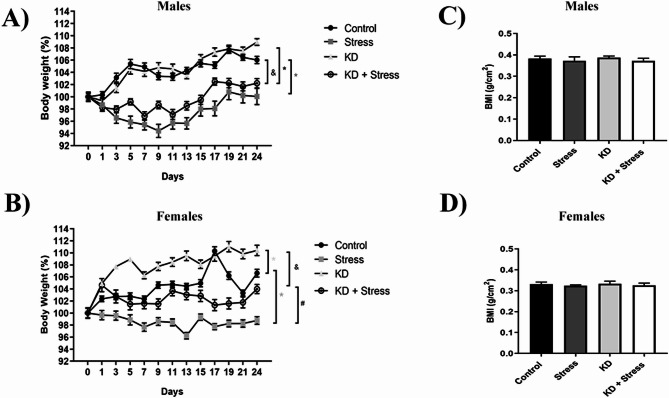

Body weight

To assess whether the consumption of a KD induces changes in body weight in BALB/c mice under conditions of rest or chronic stress, we monitored body weight changes through the protocol (males, n = 4–5 mice / group; females, n = 5–10 mice / group).

We found that the consumption of a KD does not alter the body weight of male mice. However, when subjected to stress, male mice lost 6% of their body weight by day 23 of the protocol, regardless of whether they consumed a standard (p = 0.0001) or a KD (p = 0.0001) diet (Fig. 2A). However, we did not observe changes in BMI (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of body weight gain during 23 d of the protocol. Mice were divided into four groups and subjected to a chronic restraint stress protocol, a chow diet, and a KD. Results were reported as a percentage of body weight. In males on a KD, a decrease in body weight was observed under chronic stress, when consuming a standard and a KD. In females, mice that consumed a KD increased their body weight, whereas in chronic stress they lost weight. No alterations in BMI were observed in any of the conditions evaluated. Body weight gain in (A) male and (B) female mice of the BALB/c strain, during 23 d of chronic stress and consumption of a KD. IBM in (C) male and (D) female BALB/c mice during 23 d of chronic stress and consumption of a KD; n = 4–10 mice/ group. Data represent the mean ± standard error. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant

Female mice consuming a KD gained 4% more body weight (p = 0.0008), this weight gain was not observed under stress conditions, where the mice lost 6% of their body weight (p = 0.0364). Female mice fed a standard diet and chronically stressed lost 7% of their body weight, as compared with resting mice (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 2B). No changes in BMI were observed under KD or stress conditions (Fig. 2D).

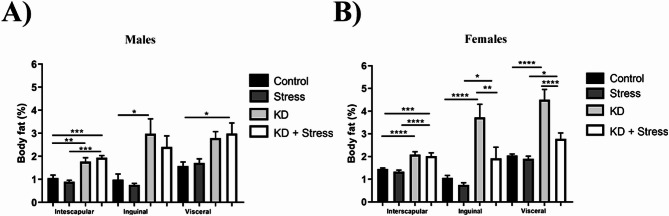

Body fat mass

Animals were euthanized and tissues excised, the interscapular, inguinal and visceral adipose tissue deposits of all experimental groups were weighed.

In male mice (n = 4–5 / group) consuming a KD, interscapular fat increased from 1.05 to 1.77% (p = 0.0040) and inguinal fat increased from 0.98 to 2.97% (p = 0.0285). In addition, male mice on the KD subjected to chronic stress showed an increase in interscapular fat from 1.05 to 1.9%, as compared to resting (p = 0.0006) or stressed mice on a standard diet (p = 0.0002). Similarly, male mice that consumed KD and were subjected to chronic stress exhibited an increase in visceral fat from 1.57 to 2.98% (p = 0.0237) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of body fat mass changes at day 23 of restraint stress, KD, or their combination. In mice that consumed a KD, an increase in interscapular, inguinal, and visceral tissue deposits was observed in both sexes. In stressed mice, only females with KD showed a decrease in inguinal and visceral tissue deposits. Body fat mass in (A) male and (B) female BALB/c mice at day 23 of chronic stress and consumption of a KD; n = 4–10 mice/ group. Data represent the mean ± standard error. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant

In female mice (n = 5–10 / group) consuming a KD, an increase in interscapular fat from 1.4 to 2.08% (p = 0.0001), inguinal fat from 0.98 to 2.97% (p = 0.0285), and visceral fat from 2.04 to 4.5% (p = 0.0001) was observed. However, when mice on KD were subjected to chronic stress, both inguinal (1.91%) and visceral (2.7%) fat significantly (p = 0.0025) decreased (Fig. 3B).

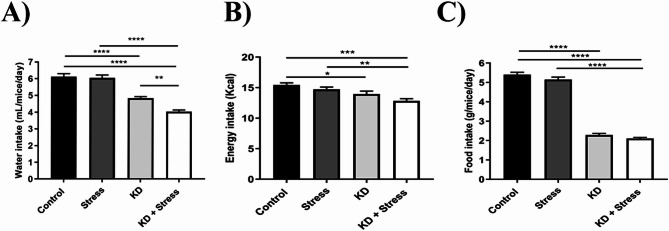

Feeding and drinking behavior

To assess whether food and water consumption contributed to the increase in body weight and fat in the mice, we evaluated water, food and energy intake in our experimental groups (males, n = 4–5 mice / group; females, n = 5–10 mice / group).

Males on a KD consumed 50% less water than mice on a standard diet (p = 0.0001). This decrease in water consumption was more pronounced in mice that were on a KD and subjected to chronic stress (4.02 mL, p = 0.0018) (Fig. 4A). When evaluating energy intake, male mice had a lower energy intake (12.8 kcal/day) under a KD both at resting (p = 0.0494) and under stress (p = 0.0059) conditions (Fig. 4B). Food intake decreased in male mice on a KD (Fig. 4C), regardless of whether they were at resting (1.65 g/day, p = 0.0001) or under stress (1.84 g/day, p = 0.0001), compared to mice on a standard diet (5.40 g/day).

Fig. 4.

Effect of a KD on eating behavior in male mice under chronic stress. In mice under a KD, a decrease in water, energy, and food intake was observed, as compared with the control group. However, in mice with KD under stress, a decrease in water consumption was observed. Average intake of (A) water and (B) energy intake, and (C) food of male BALB/c mice under a KD and chronic stress; n = 4–10 mice/ group. Data represent the mean ± standard error. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant

Similarly, female mice water intake decreased (2.96 g/day, p = 0.0001) under KD (Fig. 5A). We did not observe significant differences in energy intake (Fig. 5B). Food intake decreased under a KD (Fig. 5C), both at rest (1.65 g/day, p = 0.0001) and under chronic stress (1.84 g/day, p = 0.0001), as compared with those on a standard diet (4.01 g/day).

Fig. 5.

Effect of a KD on eating behavior in female mice under chronic stress. In mice under a KD, a decrease in food and water consumption was observed, as compared with the control group. Average intake of (A) water and (B) energy, and (C) food of female BALB/c mice under a KD and chronic stress; n = 4–10 mice/ group. Data represent the mean ± standard error. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

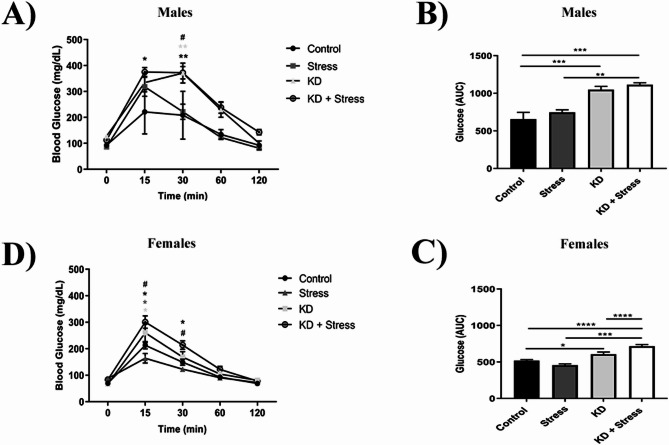

Glucose tolerance

In male mice on a ketogenic diet, lower glucose tolerance was observed both at resting conditions (minute 30; p = 0.0082) and chronic stress (minute 15; p = 0.0138 and minute 30; p = 0.0273). This was consistent with the AUC, for which an increase in area was observed in mice consuming a ketogenic diet both at resting (p = 0.0007) and chronic stress conditions (p = 0.0002) (Fig. 6A and B) (n = 4–5 mice / group).

Fig. 6.

Effect of a KD, chronic stress, and their combination in BALB/c mice on day 23 of the protocol. Mice were fasted for six hours, after which blood was collected from the tip of the tail and a determination of basal blood glucose was performed using a glucometer. After intraperitoneal glucose injection, blood glucose levels were measured at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. Mice that were under a KD had lower glucose tolerance in both sexes. Glucose tolerance test in (A) male and C) female BALB/c mice on day 23 of the protocol. Area under the curve in (B) male and D) female mice under a KD and chronic stress due to movement restriction; n = 4–10 mice/ group. Data represent the mean ± standard error. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In female mice on a KD, lower glucose tolerance was observed at resting (minute 15; p = 0.0421) and under chronic stress conditions (minute 15; p = 0.0001 min 30; p = 0.0019). In contrast, mice under chronic stress on a standard diet showed improved glucose tolerance (minute 15; p = 0.0087). When evaluating the AUC, an increase was observed in the KD group (p = 0.0187) and in the KD group under stress (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 6C and D) (n = 5–10 mice / group).

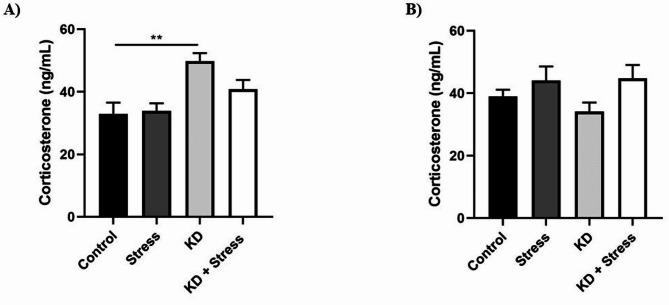

Plasmatic corticosterone levels

In male mice (n = 4–5 mice/group) that consumed KD, plasma corticosterone levels significantly increased from 32.88 ng/mL to 49.73 ng/mL compared to the control group (p = 0.0086) (Fig. 7A). In contrast, no significant changes were observed among female groups, or by stress induction (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Evaluation of plasma corticosterone levels in BALB/c mice under resting conditions, restraint stress, KD, or their combination. Males that consumed KD for 23 days showed an increase in plasma corticosterone levels, but not females. Corticosterone levels in BALB/c mice: (A) males and (B) females under mobility restriction, KD, or their combination; n = 4–10 mice / group. Data represent the mean ± standard error. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effect of a ketogenic diet in chronically stressed obesity-resistant BALB/c mice. Our results showed that KD and chronic stress independently influenced body weight and glucose tolerance in female BALB/c and their interaction alters the direction and magnitude of these responses.

To confirm that the KD used in this study induced nutritional ketosis; we evaluated blood levels of β-hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body considered responsible for anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects observed against chronic degenerative diseases [20]. Circulating ketone bodies are produced under different conditions in the body, including starvation, fasting, prolonged exercise or dietary regimens such as the KD [6, 7]. In our study, the animals fed a KD developed higher levels of ketone bodies, compared with the groups fed a standard diet, which agrees with previous reports where the effects of this diet were studied [25, 27, 28]. Regarding the impact of stress on ketone bodies levels, it has been observed in various reports that during acute stress, plasma levels of BHB increase [17, 29, 30]. Others have reported that in C57BL/6 mice subjected to acute social defeat stress (SDS), BHB levels increased [18], whereas a chronic stress protocol did not significantly affect plasma BHB levels, consistent with our results. We observed no changes in BHB levels in animals under chronic stress and a standard diet, compared with groups on resting conditions.

However, for animals under KD, although increasing levels were observed in both sexes under chronic stress, levels of BHB were lower in females, indicating that chronic stress suppresses the increase in levels of circulating ketone bodies in a sex-dependent manner in BALB/c mice, in contrast with others findings [16].

These sex-specific effects could be attributed to the estrous cycle in females, variations in female sex hormones, age, strain, or even the study model. Sex differences have been observed in plasma ketone body levels, with women exhibiting higher fasting ketone body levels and showing sex-dependent responses to metabolic challenges [31, 32]. However, the exact mechanism underlying these differences remains unclear. Additionally, it has been reported that males consuming a ketogenic diet (KD) are more susceptible to metabolic changes, such as increased insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, whereas females are more susceptible to morphometric changes, such as greater adiposity [21]. In a study of C57Bl/6J mice consuming a KD, females were more susceptible to the adverse metabolic changes observed [33].

Numerous reports have demonstrated the effects of consuming a KD on body weight, most of which report the loss of body weight and a decrease in body fat [12, 13]. This contrasts with the findings of our study, where we observed that females on a KD gained body weight and body fat, which was lost when animals were subjected to chronic stress, confirming the potential of the KD to reduce the effects of chronic stress on body weight. Others have observed that in Long-Evans rats subjected to unpredictable chronic stress for 21 days, a KD protected females from stress-mediated weight loss [16].

On the other hand, no changes in body weight were observed in male BALB/c mice fed with KD, whereas the groups under chronic stress lost weight regardless of the type of diet. Furthermore, we showed that body fat in male BALB/c mice increased when KD was administered, regardless of conditions, which may indicate that adipose depots are differentially affected by a KD. These sex-based differences might be related to the presence of sex hormones and their distinct roles in the mouse, with the presence of estrogen and the hormonal cycle [34]. For this study, the estrous cycle of the females was not evaluated to avoid any other stressors that may influence the results.

We assessed the intake of food and water, as behavior that may explain the weight gain. In both sexes, we found that when mice consumed KD, water and food daily intake decreased to half of what they consume when on standard chow. In this regard, we calculated energy intake, finding a decrease only in males, suggesting that food consumption is not related to body weight gain. It has been reported that KD induces satiety faster than standard chow, which agrees with our results. Therefore, it would be of interest to evaluate alterations in hormones such as leptin or ghrelin, as well as proteins involved in the regulation of metabolism in our future research. FGF21, for instance, has been directly correlated with metabolic regulation and thermogenesis, being one of the main regulatory proteins involved in the consumption of the KD, and one of the main candidates for its regulation [35, 36]. In addition, it has been shown that FGF21 is related to dietary intake [37]. The KD used in this study is primarily composed of soybean oil and lard, with both saturated and unsaturated fats, as well as a 15% protein content. Proteins may provide an energy source through gluconeogenesis, which may interfere with biological effects such as weight loss [38]. When consuming a low-carbohydrate diet, metabolism is altered because there is no glucose available as the primary source of energy. As a result, the body is forced to seek an alternative energy source through ketogenesis, leading to lower glucose levels and an improvement in insulin levels.

In our study, under this dietary regimen, mice that consumed the KD showed reduced glucose tolerance or elevated levels of glucose, which is conflicting with other authors’ reports, using the same mouse strain, the same percentage of macronutrients, or different diet administration protocols [36, 39]. On the other hand, some authors have reported comparable results to those found in our study, when the same diet was used [24, 40]. It has been demonstrated that the macronutrient composition of ketogenic diets can influence the observed effects, primarily those related to the composition of saturated fats in the diet [41, 42]. This also maintains a state of nutritional ketosis, which is consistent with our results.

When evaluating plasma corticosterone levels, no alterations were observed in the stressed groups, both in males and females. Although this contrasts with findings from various authors reporting increased serum corticosterone levels in response to different stressors [43, 44], it aligns with previous findings in the same model used in this study [23]. This contrast may be attributed to the habituation of mice to the stress paradigm. In this regard, it has been observed that 21 days of restraint stress led to habituation in mice, reflected in the absence of changes in corticosterone levels [45].

On the other hand, along with the increase in corticosterone, a decrease in body weight is observed throughout the stress paradigm, both parameters being indicative that the subjects are under stress [45, 46]. Although no changes in corticosterone levels were detected in our study, a significant loss of body weight was observed. The response to a stressor is influenced by multiple factors, including weight, age, strain, genetics, type of stimulus, and its duration, all of which play a crucial role in an individual’s adaptability to stress and its potential consequences [47].

When evaluating corticosterone levels in KD-fed mice, we observed an increase in plasma levels in male mice, whereas no changes were observed in females. The activity of the HPA axis has been linked to an individual’s nutritional status, particularly in the context of KD, through alterations in the production of metabolic hormones such as cortisol. In this regard, an increase in serum cortisol levels has been reported in Sprague-Dawley rats after two weeks on a KD [48]. Similarly, in male C57BL/6J mice and Long-Evans rats that consumed KD for three weeks, an increase in plasma corticosterone levels was observed, consistent with our findings [49]. This suggests that nutritional ketosis, induced by KD consumption, activates the HPA axis in a sex-dependent manner.

Conclusions

In summary, chronic stress attenuates the effects of a KD in weight gain and BHB levels in female BALB/c mice. In contrast, the KD inhibits the increase in glucose tolerance observed in female BALB/c under chronic stress. These results suggest an interplay between chronic stress and a high-fat KD that modifies their effects in a sex-dependent manner. Additional research is necessary to investigate this interplay, as well as to assess the importance of sex hormones in the findings of this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Laboratorio de Inmunología y Virología from Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo Léon for the facilities provided to accomplish this work. We also thank M.Sc. Alejandra Arreola-Triana, ELS for language correction of the manuscript and Adrián Galván Quintero for his technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under curve

- BHB

Beta-hydroxybutyrate

- BMI

Body mass index

- KD

Ketogenic diet

Author contributions

A.L.C.R., D.C.H., R.T.G. and C.R.P.: Conceived and designed the experiments; A.L.C.R. wrote the original draft, prepared figures, reviewed and edited; A.L.C.R., I.G.L. and D.C.H. performed experiments. D.C.H., A.C.M.T., R.G.F., P.T.G. analyzed data, reviewed and edited manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.C.H. was awarded a PAICYT grant with ID CN1560-21 from Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. A.L.C.R. and I.G.L. received fellowship grants from CONAHCYT with IDs 966501 and 966540.

Data availability

Data is available as supplementary material.

Declarations

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All experiments with animals complied with Mexican regulation NOM-062-ZOO-1999 and were approved by the UANL Research Ethics and Animal Welfare Committee (CEIBA-2021-002).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Baum A. Stress, intrusive imagery, and chronic distress. Health Psychol. 1990;9(6):653–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens MAC, Wand GS. Stress and the HPA axis: role of glucocorticoids in alcohol dependence. PubMed. 2012;34(4):468–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis J, Fournakis N, Ellison JM. Ketogenic diet for the treatment and prevention of dementia: A review. J Geriatr Psychiatr Neurol. 2020;34(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy PA, Likhodii S, Nylen K, Burnham WM. The antidepressant properties of the ketogenic diet. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(12):981–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tieu K, Périer C, Caspersen C, Teismann P, Wu D, et al. D-β-Hydroxybutyrate rescues mitochondrial respiration and mitigates features of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(6):892–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masood W, Annamaraju P, Khan Suheb MZ et al. Ketogenic Diet. StatPearls. 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499830/. Accessed 2024 Jan. [PubMed]

- 7.Puchalska P, Crawford PA. Multi-dimensional roles of ketone bodies in fuel metabolism, signaling, and therapeutics. Cell Metabol. 2017;25(2):262–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cicero AFG, Benelli M, Brancaleoni M, Dainelli G, Merlini D, Negri R. Middle and Long-Term impact of a very Low-Carbohydrate ketogenic diet on cardiometabolic factors: A Multi-Center, Cross-Sectional, clinical study. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2015;22(4):389–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Rashidy OF, El-Baz F, Gendy YGE, Khalaf RI, Reda DJ, Saad K. Ketogenic diet versus gluten free casein free diet in autistic children: a case-control study. Metab Brain Dis. 2017;32(6):1935–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong K, Raffray M, Roy-Fleming A, Blunden S, Brazeau A. Ketogenic diet as a normal way of eating in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A qualitative study. Can J Diabetes. 2020;45(2):137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yancy WS, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EA. Low-Carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a Low-Fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(10):769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douris N, Desai BN, Fisher FM, Cisu T, Fowler AJ, Zarebidaki E, et al. Beta-adrenergic receptors are critical for weight loss but not for other metabolic adaptations to the consumption of a ketogenic diet in male mice. Mol Metabolism. 2017b;6(8):854–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brownlow M, Jung SY, Moore R, Bechmann N, Jankord R. Nutritional ketosis affects metabolism and behavior in Sprague-Dawley rats in both control and chronic stress environments. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polito R, Messina G, Valenzano A, Scarinci A, Villano I, Monda M, Porro C, Pisanelli D, Monda V, Messina A. The role of very low calorie ketogenic diet in sympathetic activation through cortisol secretion in male obese population. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner S, Davies E, Barkus E, Kraeuter A. Ketogenic diet has a positive association with mental and emotional well-being in the general population. Nutrition. 2024;124:112420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahagun E, Ward L, Kinzig KP. Attenuation of stress-induced weight loss with a ketogenic diet. Physiol Behav. 2019;212:112654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubera B, Hubold C, Wischnath H, Zug S, Peters A. Rise of ketone bodies with psychosocial stress in normal weight men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;45:43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato S, Yu Z, Sakai M, Motoike IN, Saigusa D, Hirayama R, et al. Decreased β-hydroxybutyrate and ketogenic amino acid levels in depressed human adults. Eur J Neuroscience/EJN Eur J Neurosci. 2023;57(6):1018–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji J, Fotros D, Sohouli MH, Velu P, Fatahi S, Liu Y. The effect of a ketogenic diet on inflammation-related markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 2024;83(1):40–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamanashi T, Iwata M, Kamiya N, Tsunetomi K, Kajitani N, Wada N, et al. Beta-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenic NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, attenuates stress-induced behavioral and inflammatory responses. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sprankle KW, Knappenberger MA, Locke EJ, Thompson JH, Vinovrski MF, Knapsack K, Kolwicz SC. Sex- and Age-Specific differences in mice fed a ketogenic diet. Nutrients. 2024;16(16):2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beery AK, Zucker I. Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35(3):565–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caballero-Hernandez D, Najera-Valderrabano D, Valadez-Lira A, Franco-Molina M, Gomez-Flores R, Tamez-Guerra P, Tamez-Guerra R, Rodríguez-Padilla C. Alterations of antitumor and metabolic responses in L5178Y-R lymphoma-bearing mice after only 30-minute daily chronic stress exposure. Exp Oncol. 2017;39:4, 276–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinzig KP, Honors MA, Hargrave SL, Davenport BM, Strader AD. Wendt, D. Sensitivity to the anorectic effects of leptin is retained in rats maintained on a ketogenic diet despite increased adiposity. Neuroendocrinology. 2010a;92(2):100–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahagun E, Bachman BB, Kinzig KP. Sex-specific effects of ketogenic diet after pre-exposure to a high-fat, high-sugar diet in rats. Nutr Metabolism Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31(3):961–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benedé-Ubieto R, Estévez-Vázquez O, Ramadori P, Cubero FJ, Nevzorova YA. Guidelines and considerations for metabolic tolerance tests in mice. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome Obes. 2020;13:439–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy A, Pissios P, Otu HH, Xue B, Asakura K, Furukawa N, Marino FE, Liu F, Kahn BB, Libermann TA. Maratos–Flier, E. A high-fat, ketogenic diet induces a unique metabolic state in mice. Am J Physiology-endocrinology Metabolism. 2007;292(6):E1724–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinzig KP, Scott KA, Hyun J, Bi S, Moran TH. Altered hypothalamic signaling and responses to food deprivation in rats fed a Low-Carbohydrate diet. Obes Res. 2005;13(10):1672–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishiguchi T, Iwata M, Kajitani N, Miura A, Matsuo R, Murakami S, et al. Stress increases blood beta-hydroxybutyrate levels and prefrontal cortex NLRP3 activity jointly in a rodent model. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2021;41(2):159–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Son H, Baek JH, Kang JS, Jung S, Chung H, et al. Acutely increased β-hydroxybutyrate plays a role in the prefrontal cortex to escape stressful conditions during the acute stress response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;554:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cochran J, Taufalele PV, Lin KD, Zhang Y, Abel ED. Sex Differences in the Response of C57BL/6 Mice to Ketogenic Diets. 2018; Diabetes, 67.

- 32.Ruppert PM, Kersten S. Mechanisms of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis during fasting. Trends Endocrinol Metabolism. 2023;35(2):107–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smolensky I, Zajac-Bakri K, Odermatt TS, Brégère C, Cryan JF, Guzman R, Timper K, Inta D. Sex-specific differences in metabolic hormone and adipose tissue dynamics induced by moderate low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diet. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Sex differences in metabolic homeostasis, diabetes, and obesity. Biology Sex Differences. 2015; 6(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Murata Y, Nishio K, Mochiyama T, Konishi M, Shimada M, Ohta H, Itoh N. Fgf21 impairs adipocyte insulin sensitivity in mice fed a Low-Carbohydrate, High-Fat ketogenic diet. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8(7), e69330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Watanabe M, Singhal G, Fisher FM, Beck TC, Morgan DA, Socciarelli F, et al. Liver-derived FGF21 is essential for full adaptation to ketogenic diet but does not regulate glucose homeostasis. Endocrine. 2019;67(1):95–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song P, Zechner CPG, Hernandez G, Canovas JM, Xie Y, Sondhi V, et al. The hormone FGF21 stimulates water drinking in response to ketogenic diet and alcohol. Cell Metabol. 2018;27(6):1338–e13474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffin L, Gentile J. Ke Jia-Yu. Ketogenic Diet for Rodents: Diverse Applications for Neurological and Metabolic Diseases. Research Diets. 2020.

- 39.Moreno B, Bellido D, Sajoux I, Goday A, Saavedra D, Crujeiras AB, Casanueva FF. Comparison of a very low-calorie-ketogenic diet with a standard low-calorie diet in the treatment of obesity. Endocrine. 2014;47(3):793–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kinzig KP, Honors MA, Hargrave SL. 2010. Insulin Sensitivity and Glucose Tolerance Are Altered by Maintenance on a Ketogenic Diet. Endocrinology. 2010b. 151(7), 3105–3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Fuehrlein BS, Rutenberg MS, Silver JN, Warren MW, Theriaque DW, Duncan GE, Stacpoole PW, Brantly ML. Differential metabolic effects of saturated versus polyunsaturated fats in ketogenic diets. J Clin Endocrinology Metabolism/Journal Clin Endocrinol & Metabolism. 2004;89(4):1641–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denke MA. Metabolic effects of high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets. The American J Cardiol. 2001;88(1):59–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo Y, Sun J, Li T, Zhang Q, Bu S, Wang Q, Lai D. Melatonin ameliorates restraint stress-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in testicular cells via NF-κB/iNOS and Nrf2/ HO-1 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Vagnerová K, Jágr M, Mekadim C, Ergang P, Sechovcová H, Vodička M, Olša Fliegerová K, Dvořáček V, Mrázek J, Pácha J. Profiling of adrenal corticosteroids in blood and local tissues of mice during chronic stress. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):7278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding JX, Rudak PT, Inoue W, Haeryfar SM. Physical restraint mouse models to assess immune responses under stress with or without habituation. STAR Protocols. 2021. 2(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Michel C, Duclos M, Cabanac M, Richard D. Chronic stress reduces body fat content in both obesity-prone and obesity-resistant strains of mice. Horm Behav. 2005;48(2):172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, Kopp B, Wulsin A, Makinson R, Scheimann J, Myers B. (2016). Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary‐Adrenocortical Stress Response. Comprehensive Physiology. 2016; 603–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Thio LL, Erbayat-Altay E, Rensing N, Yamada KA. Leptin contributes to slower weight gain in juvenile rodents on a ketogenic diet. Pediatr Res. 2006;60(4):413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryan KK, Packard AEB, Larson KR, Stout J, Fourman SM, Thompson AMK, et al. Dietary manipulations that induce ketosis activate the HPA axis in male rats and mice: a potential role for fibroblast growth factor-21. Endocrinology. 2018;159(1):400–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available as supplementary material.