Abstract

Background

In recent years, health centers in the United States have invested significant efforts to identify, develop, and implement various health professions training (HPT) programs to combat projected workforce shortages. However, such engagement is inherently complex as health centers are unique teaching settings with the primary function of healthcare delivery. The Readiness to Train Assessment Tool (RTAT) is a 41-item validated survey designed to measure organizational readiness for implementing HPT programs in health centers.

Methods

Between September 2020 and February 2021, the RTAT survey was distributed to all health center employees in the US and US territories. All participants were encouraged to complete the first subscale assessing the health center’s core readiness and commitment to HPT. Those with knowledge, involvement, or interest could select and evaluate specific HPT program(s) within four clinical discipline using the remaining six subscales. Scores were averaged over all participants from the same health center.

Results

Out of 1,466 targeted health centers nationwide, 1,063 health centers (72.5%) responded to the survey and assessed their readiness to engage, while 713 health centers continued the second portion of the survey to assess their readiness to implement at least one HPT program within four clinical disciplines for a total of 1,118 HPT programs assessed. Overall, within clinical disciplines, 10-14% of the health centers were still developing readiness, 48-59% were approaching readiness, and 27-42% were fully ready. Of note, there are a large portion of health centers approaching readiness and can reach full readiness by examining specific readiness areas at the survey item level to determine where barriers exist and where targeted strategies could improve their readiness. These results provide a national-level baseline for future comparisons and for making evidence-based decisions that drive regional and national policy choices for HPT at health centers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the RTAT results were shared with health centers in an individualized, detailed report to fulfill a significant need to identify health centers’ core readiness and capacity to engage in health professions training and determine an appropriate course of action for individual health centers, primary care associations, policymakers, and health professions education and training leaders.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-025-13046-4.

Keywords: Health center, Organizational readiness, Health professions training, Workforce, Implementation, Dissemination, Measure, Survey

Background

In the United States (US), health centers are community-based organizations that deliver primary healthcare services (medical, dental, behavioral, and other) to patients living in or near poverty and those publicly insured or uninsured [1]. They serve as the essential healthcare safety net for an estimated 30 million of the nation’s most vulnerable and underserved populations, regardless of their ability to pay [2]. Health centers, through their coordinated, comprehensive, patient-centered care models, have advanced health equity, addressed emerging public health needs, and improved care quality to meet the needs of their populations [1–5]. Many studies have shown that health centers’ efforts in delivering high-quality care have often exceeded the national standards for providing many healthcare services and have lowered utilization of costly care choices for US populations experiencing economic, geographic, and cultural barriers to affordable healthcare [6–15].

The demand for the services provided by US health centers has been increasing throughout the years [16–18], leading to rapid growth in the number of health centers and challenges with staff recruitment and retention [17–19]. Contributing to these challenges at the national level have been the shortages and geographic maldistribution of primary service providers (e.g., family, general internal, geriatric, and pediatric physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) [20, 21]. In addition, the demanding work environments at the health centers (e.g., insufficient funding and understaffing, time pressures, high workloads) and their challenging patient populations (e.g., more complex patients’ medical and social needs and limited access to specialty care) lead to high rates of employee burnout and turnover [16, 22–27]. Because of the limited health professions training opportunities offered at the health centers [28, 29], new graduates often lack the skills necessary to practice in these settings and get overwhelmed by the complexity of their patients [30].

To address these issues, in recent years, health centers in the US have invested significant efforts to train their own staff by identifying, developing, and implementing various health professions training (HPT) programs [31–42], including 69.31% of federally funded health centers reporting they provide health professional education/training [43]. However, such engagement is inherently complex [44]; health centers are unique teaching settings with the primary function of healthcare delivery.

The health centers’ interest in HPT brings the question of how ready the health centers are to engage and implement specific HPT programs across different clinical disciplines: medical, dental, behavioral health and substance abuse, and others. Answering this question would meet the need at the national level to help health centers address concerns regarding their capacity to implement and sustain health professions training programs. With this need in mind, in 2018, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) authorized the creation of a survey instrument that measures organizational readiness constructs important for implementing health professions training programs at health centers [45]. This significant investment, as well as funding training programs, such as the National Health Services Corps and Teaching Health Centers, demonstrate HRSA’s efforts to support health centers in training the next generation.

The survey, the Readiness to Train Assessment Tool (RTAT), was developed and validated by the Weitzman Institute of Community Health Center, Inc. (CHCI) from 2018 to 19 [46], the survey is available at https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-021–06406-3.

The current article summarizes the results from the first national administration of the RTAT to health centers in 2020. The following main questions were addressed:

What are health centers’ core readiness and commitment to engage with health professions training in general?

What are the HPT programs of most interest or of most importance to the health centers in the US and territories?

How ready are health centers to implement specific HPT programs?

What barriers are health centers experiencing based on the RTAT organizational readiness areas?

Methods

RTAT survey

Health centers’ degree of organizational readiness to engage with HPT programs was measured using the RTAT, a 41-item, 7-subscale validated survey instrument [46]. Each RTAT subscale represents a different readiness area and consists of a specific number of survey items. Brief descriptions of the RTAT subscales [46], based on The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [47], are provided in Table 1. The first subscale (Core Readiness to Engage) is used to evaluate the health center’s core readiness and commitment to engage with health professions training. All health center employees are encouraged to complete the eight survey items of this subscale. Health center employees interested or knowledgeable about a specific HPT program or those ‘directly or indirectly involved with a specific program’ can make the decision to evaluate specific HPT programs using the remaining six subscales.

Table 1.

Descriptions and number of survey items of the seven subscales of RTAT

The RTAT survey defines ‘organizational readiness’ as the degree to which health centers are motivated and capable of engaging with and implementing HPT programs [46]. This definition was intended to be more general and in line with the main constructs of the Organizational Readiness to Change (ORC) theory (change commitment and change efficacy) [48], mainly because there is no consensus around a definition of organizational readiness for change [49]. Consistent with the ORC theory, while building capacity is required to successfully get a health center ready to implement an HPT program, an overall collective motivation or commitment to engage with HPT is equally and critically important [48, 50].

Further, for the purposes of the RTAT survey, the following are considered examples of types of HPT programs: (i) established affiliation agreements with academic institutions to host students or trainees; (ii) formal agreements with individual students; and (iii) directly sponsoring accredited or accreditation-eligible training programs (across all disciplines and education levels). Moreover, the survey instrument can be applied to various health centers and HPT programs.

Health centers as the unit of analysis in the RTAT survey

The unit of analysis of the RTAT survey is the individual organization (a health center) and not the individual respondent, and the RTAT survey items reflect the health center as the assessed unit (e.g., ‘At our health center, engaging with health professions training is compatible with our organizational culture.‘). In order to eliminate any confusion that the respondent’s health center was the unit of analysis for the survey items, the organizational context of the survey questions was emphasized in the instructions to the respondents.

RTAT scoring

Each of the 41-survey items has five response categories ranging from 1 to 5 (five-point Likert scale). The response categories indicate the degree of agreement (5-strongly agree to 1-strongly disagree) with the statement (the survey item). Thus, the degree of agreement with the survey statement the participant selected is quantified and represents the score provided for the specific survey item. These scores are averaged over all participants from the same health center who responded to the particular survey item or assessed the particular HPT program.

Each survey item contributes equally to the subscale and overall scale score. The subscale scores are calculated by taking the average of the survey items associated with the specific subscale, while the overall readiness scale score is derived by obtaining the average of all 41-survey items. This structure and scoring allow for three assessment levels: at the survey item, subscale, and overall scale levels, by obtaining their mean (average) scores.

The overall readiness score for a particular HPT program is calculated at the health center level as the average of the 41 readiness survey items and is thus based on all seven RTAT subscales (one core and six program-specific). Ultimately, the overall readiness of a health center to implement a specific HPT program is based on the responses from all health center employees participating in the RTAT survey.

At any level of assessment, the mean RTAT scores may range from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating the highest readiness to engage with and implement a specific HPT program. To establish readiness thresholds, we utilized these mean scores to assign three levels of readiness: developing readiness (mean scores 1.0–2.9); approaching readiness (mean scores 3.0–3.9); and full readiness (mean scores 4.0–5.0) - for each survey item, subscale, and for the overall scale.

We used these three readiness levels to measure individual health centers’ core readiness and program-specific readiness areas to engage with various HPT programs.

National distribution of the RTAT survey

In September 2020, CHCI created an online survey of the RTAT for national administration using Qualtrics Research Core software1 (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The Primary Care Associations (PCAs) [45, 51] distributed the survey to key contacts of all health centers in each state. The key contacts shared the received instructions and a link to the online survey with all staff members at their health center. The CHCI researchers closely monitored the response rates and reported them to the PCAs to help expand and pivot the survey distribution efforts. The data collection closed at the end of February 2021.

RTAT participant groups

All employees of health centers in the US and US territories were invited to participate in the RTAT survey, which was completely anonymous. Survey participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with the RTAT statements as they pertain to the readiness of their health center to engage with HPT program(s). They were encouraged to respond openly and honestly, based only on their judgment, regardless of what others expect at their health center.

Importantly, the RTAT survey was separated into two portions because not all health center employees had enough knowledge to provide valid responses to all survey questions. Due to this specialization of knowledge, the first portion focused on the health centers’ core readiness and commitment to health professions training in general. All health center employees were encouraged to complete this portion (8 survey items of the core readiness to engage subscale).

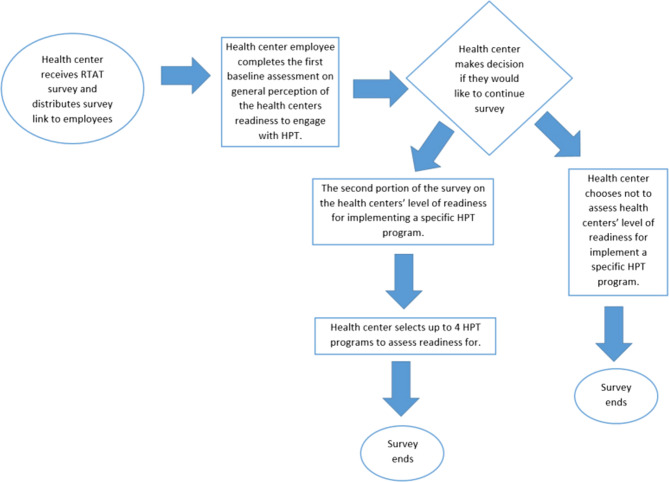

Staff members interested or knowledgeable about a specific HPT program or those ‘directly or indirectly involved with a specific program’ were asked to continue with the second portion. These respondents could assess their health center readiness for HPT programs of their choosing within four clinical discipline categories (medical, dental, behavioral health and/or substance abuse, and others). Our recommendation was to choose and assess readiness for programs of the most importance or the most significant interest to their organization. The respondents were allowed to complete the second portion of the survey up to three times. Within the medical and dental disciplines, employees had the option to simultaneously assess their health center readiness for several programs of their choosing. Within the disciplines ‘behavioral health and/or substance abuse’ and ‘other programs’, they had to assess their readiness one program at a time. See Fig. 1 for a flow diagram depicating the RTAT survey participation.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of RTAT survey participation

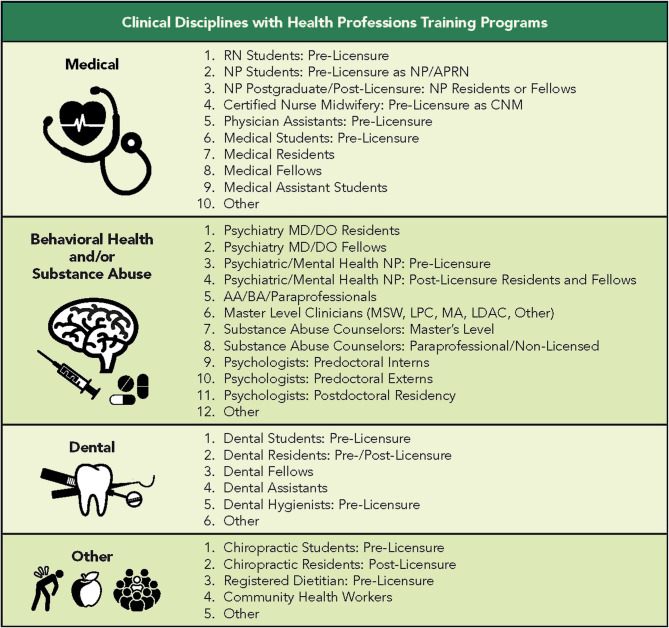

Additionally, each clinical discipline had options of HPT programs for the respondent to select. The options of HPT programs were determined by subject matter experts in federally funded health centers. Figure 2 includes all the HPT program available for each clinical discipline. For each clinical discipline category, the respondent had the option of “other”. By selecting “other”, the respondent was given a free text box to write in a HPT program that they would like to assess readiness for.

Fig. 2.

Assessed health professions training programs by clinical discipline

This research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Research ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the Community Health Center, Inc., Protocol ID: 1176. For all participants in the study informed consent was implied by the completion of the online survey after reading the study information sheet.

Results

RTAT survey response rate and summary statistics

Out of 1,466 targeted health centers nationwide, 1,063 health centers responded to the survey. The national response rate was 72.5% of health centers within the US. All 1,063 health centers assessed their core readiness to engage with health professions training. Of those, 713 health centers also assessed their readiness to implement at least one HPT program. In total, the readiness for 1,118 HPT programs was assessed in four clinical disciplines: medical, dental, behavioral health and/or substance abuse, and others. See Fig. 2 for the assessed HPT programs within each clinical discipline.

Of all 8,239 health center employees who interacted with the survey, 7,777 provided data suitable for RTAT scoring. As per the survey design, there were two distinct types of survey respondents: respondents who scored only their health center’s core readiness and commitment to engage with HPT (5258 or 68% of all respondents) and respondents who also selected and assessed readiness for at least one HPT program (2519 or 32% of all respondents). Notably, health center employees were able to assess their health center readiness for more than one program; therefore, the total number of HPT programs assessed is larger than the number of health centers. Participants assessed medical HPT programs the most (594 or 53.1%), followed by behavioral health and/or substance abuse HPT programs (257 or 23%), dental HPT programs (183 or 16.4%), and other HPT programs (84 or 7.5%).

Further, 3,446 respondents indicated that their health centers had an existing HPT program. These respondents constituted 44% of all RTAT respondents and represented 783 health centers.

An examination of the response rates within the ten specific US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regions [52] showed that 59–92% of the health centers within a specific region responded. Health centers within Region Eight (Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming) responded well above the national response rate, with about 92% of the region’s health centers completing at least one RTAT survey. The response rates for states and US territories ranged from 41 to 100%, with 42 states/US territories having a response rate of 70% or higher. Eleven states and six US territories had 100% of their health centers responding to the survey (New Hampshire, Virginia, Alabama, Alaska, Kentucky, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado, North Dakota, Utah, Wyoming, American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Marshall Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, and the Republic of Palau).

Demographic and employment/professional characteristics of the respondents

The respondents’ demographic and employment/professional characteristics are presented in Table 2. Slightly over 40% of the respondents in the sample were 40 years of age or younger (3131, or 40.2%), with women comprising 80.4% (n = 6253). The White/Non-Hispanic group accounted for the largest percentage in the sample (about 67.7%), followed by the Hispanic/Latino (11.3%) and the Black/African American (9.3%) respondent groups. The Asian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (4.5%), multiracial (2%), and American Indian/Alaska Native (1.4%) groups were also represented. As per educational attainment, most respondents had an associate’s or higher educational degree; only about 28% of the sample had no college degree. Some of the respondents elected not to identify their age (1.9%), gender (1.1%), or race/ethnic identity (3.9%).

Table 2.

Demographic and professional characteristics of the RTAT respondents

*Respondents were allowed to select multiple options for this question

The two distinct groups of respondents, the core readiness group and the HPT program group, had some gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment differences. For example, the HPT readiness group had higher proportions of respondents in the older age categories, higher proportions of men and Black/African American respondents, and higher proportions of respondents with graduate and clinical doctorate degrees (see Table 2 for more details).

Regarding their professional profile, respondents in the sample were most likely to be employed in a leadership role at the health center (1834 respondents or 20.6%), closely followed by a care team member role (1727 respondents or 19.4%). Medical, behavioral health, and dental providers constituted almost a quarter of all RTAT respondents. More than 2,895 respondents, or 37%, had been employed at their health center for over five years. Further, the HPT program readiness group comprised more organizational leaders, medical, dental, and behavioral health providers, and employees with an educational or training role than the core readiness group.

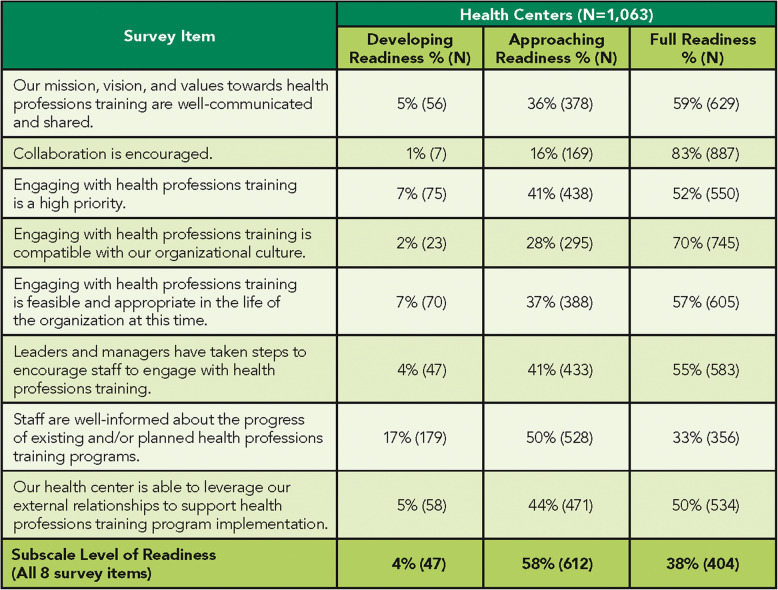

Health centers’ core readiness and commitment to engage with health professions training

Table 3 shows the distribution of all 1,063 responding health centers (7,777 individual respondents) scoring at the three levels of core readiness (developing readiness, approaching readiness, or full readiness). These distributions are presented at the individual survey item and the overall subscale score. At the national level, 38% of the participating health centers reached ‘full readiness’ on overall/core readiness to engage with HPT. Most health centers (58%) scored in the ‘approaching readiness’ range, while only 4% were in the ‘developing readiness’ range. The statements for which the two largest proportions of health centers reached ‘full readiness’ were: ‘At our health center, collaboration is encouraged.’ (83% of health centers) and ‘At our health center, engaging with health professions training is compatible with our organizational culture.’ (70% of health centers). The statement for which the largest proportion of health centers was still ‘developing readiness’ was: ‘Staff are well-informed about the progress of existing and/or planned health professions training programs.’ (17%).

Table 3.

Core readiness and commitment to engage with HPT Programs (N=1,063 health centers)

Health centers’ interest in specific HPT programs

Based on the number of individual respondents and the number of health centers selecting a specific HPT program, we analyzed health center interest in specific HPT programs. The results are based on 713 health centers assessing readiness for 1,118 HPT programs. Table 4 presents the national summary results of the top programs ranked within each clinical discipline (medical, dental, behavioral health and/or substance abuse, and other programs) from the highest to the lowest number of health centers selecting them for readiness assessment. These results should be interpreted only within each clinical discipline.

Table 4.

Top programs of importance and interest to the health centers

Nationwide, the most popular medical HPT programs were: ‘Nurse Practitioner (NP) Student’, ‘Medical Assistant (MA) Student’, and ‘Medical Resident’. Based on the number of health centers assessing the programs, the top three dental programs were: ‘Dental Assistant Students’, ‘Dental Students’, and ‘Dental Hygienist Student’, while the top three behavioral health and/or substance abuse programs were: ‘Master Level Clinicians’, ‘Substance Abuse Counselors: Master Level’, and ‘Substance Abuse Counselors: Paraprofessional’. Further, within the ‘other HPT programs’ category, the most selected program was ‘Community Health Worker’; a few health centers also selected the ‘Registered Dietitian’ and ‘Chiropractic Student’ programs.

Health centers’ readiness levels for specific HPT programs within clinical disciplines

To answer the question about health centers’ readiness to implement specific HPT programs, we analyzed the readiness of 713 health centers to implement 1,118 HPT programs. We assigned the readiness levels based on the health center’s overall RTAT score for a specific HPT program (all 41 RTAT survey items covering all seven subscales/readiness areas).

Figure 3 presents the national summary results indicating how ready the health centers are for programs within a specific clinical discipline (medical, dental, behavioral health and/or substance abuse, and other HPT programs). Overall, within clinical disciplines, 10–14% of the health centers were still developing readiness, 48–59% were approaching readiness, and 27–42% were fully ready.

Fig. 3.

Health centers’ readiness levels for HPT programs within clinical discipline

Health centers could select more than one program in each category.

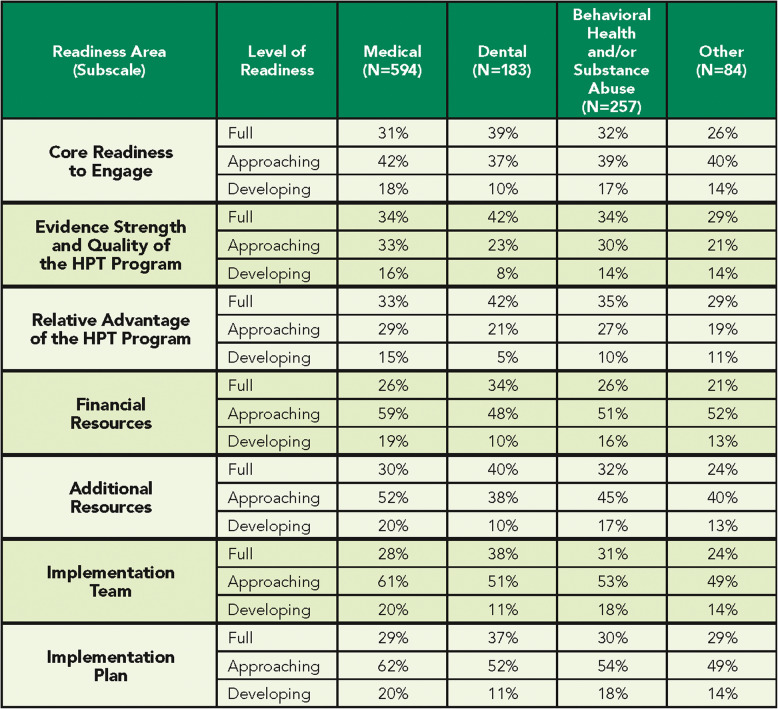

Health centers’ levels of readiness for specific readiness areas

We present results regarding barriers that health centers nationwide are experiencing across various readiness areas, as measured by the respective RTAT subscales (core and program-specific). To help each health center understand their own specific barriers, we provided individualized, analyzed reports to the health center with the responses received from their staff members. These reports allow health centers to identify which readiness areas are presenting barriers to achieve full readiness and successfully implement the intended HPT program.

Table 5 summarizes the distribution of readiness levels (Full, Approaching, and Developing) within each readiness area, or subscale, across clinical disciplines: medical, dental, behavioral health and/or substance abuse, and other HPT programs. The table presents the distribution of average readiness levels for each RTAT subscale, based on the number of responses from health centers that selected a program within each clinical discipline. Notably, a single health center may have several HPT programs assessed within each clinical discipline category that fall under different readiness levels for a given subscale.

Table 5.

Health centers' readiness within each readiness area by clinical discipline

Individual health center reports

The results from the RTAT survey were meant to help health centers and PCAs understand how well prepared the health centers are to engage with and implement health professions training programs in general and for specific HPT programs within specific clinical disciplines selected by the health center staff. To accomplish this goal, we supplied all responding health centers with individualized, detailed reports and analyses of survey responses submitted by their employees. For some health centers, the results were complex, encompassing several selected HPT programs in several clinical disciplines and requiring three levels of interpretation for each program (readiness at the overall scale, for each readiness area, considering all 41 survey items).

These reports were meant to help identify the focus of the health centers’ strategic workforce plans, encourage dialogue, and take action on these results within individual health centers. For example, a deeper examination of the RTAT results could help execute meaningful exercises (e.g., focus groups) with stakeholders and interested employees to discuss gaps and capacity to plan for future HPT engagement. If a determination is made about a specific HPT program investment, the RTAT survey could help assess and evaluate the implementation and sustainability efforts and progress since continually evaluating readiness for the subsequent implementation stages is critical for addressing concerns and securing needed resources.

RTAT scale reliability

Finally, the calculated Cronbach’s alpha of 0.931 (based on N = 5,258) for the RTAT scale verified its excellent reliability [53].

Discussion

In this article, we presented a summary of the results from the first national assessment of the readiness of US health centers to engage with and implement HPT programs. To measure health center readiness, we used the RTAT survey of critical determinants of organizational readiness that can impact the implementation of HPT programs [46]. We provided an overview of the US health centers’ commitment to engage with health professions training, their specific interest in HPT programs, and distributions of organizational readiness levels for them within a clinical discipline and specific readiness areas. While the unit of our analysis was the health center, individual health center employees served as the informants for the readiness of their health centers to engage with and implement HPT programs. The scoring results are based on their perspectives at the time of survey administration.

The distinctive nature of the health centers as teaching settings emphasized the need to determine if health professions training is a priority at the health centers in the US and the adjustments that might be needed to implement HPT training programs successfully. We assessed the health centers’ core readiness to engage with health professions training to measure commitment as a critical area of focus because engaging with health professions training involves a cultural shift in the organization. Moving to health professions training at a health center requires commitment from all employees because often their roles and work processes are redefined and redesigned, changing health center employees’ perceptions about their role in the organization.

The RTAT results provide a clear statement of the willingness of health centers nationwide to engage with health professions training. The observed levels of core readiness and commitment suggest that health centers are well-placed to engage with or sustain health professions training programs. Moreover, the RTAT surveys were completed during the COVID-19 pandemic (September 2020 to February 2021). Health center employees taking the time to focus on the critical issues of health professions training in their health centers during the pandemic further emphasizes their strong interest and willingness to contribute to advancing health professions training.

The results also point to the potential for broader engagement and implementation of health professions training programs in health centers. More than 67% of responding health centers indicated having an existing HPT program confirming the vast interest of health centers in training their own staff. The HPT programs serve as system-oriented, organizational-level solutions to reduce staff burnout; thus, the benefits of HPT training are of particular appeal to health centers willing to embrace the opportunity to train the next generation of health professionals. Because of the perpetual challenges health centers experience in staff recruitment and retention, their interest and engagement in health professions training present an opportunity to train health professionals who better understand the complex medical and social needs of the health centers’ populations and are prepared to address them by practicing with confidence and competence at the highest-performance level.

Further, the summary results indicate that health centers’ interest spans across clinical disciplines and educational levels. While there is an array of HPT programs in each clinical discipline selected by health centers, the results also point to the programs within each clinical discipline that are of the most importance and interest nationwide.

The summary results also illuminate which areas of readiness need improvement to achieve full readiness for HPT programs implementation in specific clinical disciplines. These readiness areas can be interpreted as problems, barriers, or concerns that were overcome or are being overcome by health centers. Of note are the large proportions of health centers’ approaching readiness’ in each readiness area, making clear that these health centers possess high potential for reaching ‘full readiness’ in the near future. To realize this potential, health centers should closely examine individual survey items to identify specific barriers and implement targeted strategies that could improve their readiness. For instance, if a health center is at the “developing readiness” stage in the Financial Resources subscale for the Medical Residents Program, the barrier may be addressed through grant fudning or by demonstrating the program’s return on investment for provider recruitment and retention. It is also important to note that on a national level, on average, across all four clinical disciplines, the lowest percent of respondents indicated full readiness under the Financial Resources subscale (27%), closely followed by Implementation Team (30%) and Implementation Plan (31%) (See Table 5). This indicates that, overall, health centers face significant barriers in funding, time, and institutional support to successfully implement health professions training programs.

It is important to emphasize that the summary results from the study should be considered only as a snapshot in time of health center readiness to engage and implement health professions training. This summary analysis of RTAT results at the national level established a baseline that will allow for comparisons in the future and is a way to start collecting and using health center readiness data to make evidence-based decisions that drive regional and national policy choices for health professions training at health centers. For example, the national RTAT data can support legislation, such as the Health Care Workforce Innovation Act of 2024 (H.R. 7307) [54] and the Bipartisan Primary Care and Health Workforce Act (S. 2840) [55]. Additionally, administering the RTAT survey and measuring the same readiness constructs over time at the regional, state, and health center levels in the context of multiple or specific HPT programs would allow for further comparisons in readiness and better implementation planning.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study provides a reasonable basis for generalizations and conclusions based on reliable nationwide data, the high response rates from health centers during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the selected methodology. Because of the high response rates, the potential for bias in the RTAT data is low.

A limitation of this study is that the survey captures responses only from health centers that selected an HPT program when assessing readiness levels across specific readiness areas by clinical discipline. As a result, the findings may not be generalizable to all health centers, particularly those that did not assess an HPT program. The exclusion of health centers introduces selection bias and limits the ability to make national estimates of readiness within each clinical discipline and readiness area.

With this being said, the COVID-19 pandemic probably influenced response rates differently in different US regions [52]. Certain health center employees were probably less likely to respond to surveys during the pandemic. Therefore, caution should be exercised when comparing and interpreting the survey results from this period to other measurement periods.

Additionally, while our recommendation to survey respondents was to choose programs of the most importance or the most significant interest to their organization, the program’s implementation stage (late vs. early) could have also influenced the choice of specific programs for evaluation. However, we had no data about the implementation stages of the evaluated HPT programs.

Finally, while the RTAT survey length was considered carefully during the survey design [46], we further decreased the completion time by structuring the survey for ease of response.

Recommendations

The study results indicate the US health centers’ strong interest in health professions training and the difficulties and opportunities for engaging with HPT programs. Thus, we encourage a deeper examination and comparison of the readiness scores for different HPT programs to provide helpful insight for future development and dissemination of HPT programs and potential resource allocation guidance. Further, subgroup analyses could help reveal differences in the barriers health centers experience in developing HPT programs vs. sustaining them or help determine the role health center characteristics (e.g., location, size, type, patient populations served) might play in health centers’ readiness or interest in specific HPT programs. For health centers with multiple sites, additional analysis could uncover variations in training needs across locations, particularly when sites serve different populations or are geographically distant. Lastly, future research and analysis should explore readiness among health centers located in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) [56].

As a next step, providing meaningful recommendations based on the RTAT results would mean selecting and developing the most relevant, effective, and practical implementation strategies or techniques to support health center readiness improvement and implementation efforts. Implementation strategies are critical mechanisms for supporting the implementation process [57]. Using them would be most beneficial if they are evidence-based, linked to specific determinants of implementation success, framed to appeal to the health centers and the PCAs, and incorporated into implementation efforts nationwide. To this end, we recommend several lists and taxonomies, including the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) [58] and the Behavior Change Technique [59], which can be used as a starting point for developing implementation strategies for improving specific readiness areas.

We also recommend creating a national expert panel tasked with defining realistic implementation goals that consider health centers’ diverse interests and levels of organizational readiness. As mentioned, such goals should address developing and deploying critically needed recommendations for implementation strategies based on health centers’ readiness levels to implement and sustain specific HPT programs. At the same time, goals should also address continued national RTAT assessments and focus on developing health centers’ readiness by considering all readiness areas as an integrated system.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the RTAT results fulfill a significant need to identify health centers’ core readiness and capacity to engage in health professions training and determine an appropriate course of action for individual health centers, PCAs, policymakers, and health professions education and training leaders.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge and thank all experts and survey participants for their valuable contributions leading to the successful completion of this research study.

Abbreviations

- US

United States

- HPT

Health Professions Training

- HRSA

Health Resources and Services Administration

- RTAT

Readiness to Train Assessment Tool

- CHCI

Community Health Center, Inc

- PCAs

Primary Care Associations

- HHS

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- ORC

Organizational Readiness to Change

Authors’ contributions

AS and MF led the national assessment and collaborated with federal funders, health centers, and primary care associations. IZ led as an expert on the survey design. MO conducted the data analysis for the individual health center reports. MO and MA distributed the individual health center reports. IZ conducted the statistical analyses, wrote the first draft and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed the draft for important intellectual content, approved the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and can be shared upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Research ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the Community Health Center, Inc., Protocol ID: 1176. For all participants in the study informed consent was implied by the completion of the online survey after reading the study information sheet.

Consent to participate was obtained at the beginning of the survey with the following statement: “Your participation is completely voluntary. Your consent is indicated by completing and submitting the survey.”

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Copyright© 2024 Qualtrics. Qualtrics and all other Qualtrics product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA. https://www.qualtrics.com.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Health Resources and Services Administration. What is a health center? 2013. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-centers/what-health-center. Accessed 23 Jun 2023.

- 2.National Association of Community Health Centers. Community Health Center Chartbook. 2023. Bethesda, MD: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2023. https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Chartbook-2020-Final.pdf. Accessed 23 Jun 2023.

- 3.Health Resources & Services Administration. Health Center Program: Impact and Growth. Bureau of Primary Health Care. 2018. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-centers/health-center-program-impact-growth. Accessed 23 Jun 2023.

- 4.Politzer RM, Yoon J, Shi L, Hughes RG, Regan J, Gaston MH. Inequality in america: the contribution of health centers in reducing and eliminating disparities in access to care. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58:234–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi L, Stevens GD, Wulu JT Jr, Politzer RM, Xu J. America’s health centers: reducing Racial and ethnic disparities in perinatal care and birth outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1881–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin P, Alvarez C, Sharac J, Rosenbaum SJ, Vleet A, Van, Paradise J, et al. A profile of community health center patients: implications for policy. 2013. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/8536-profile-of-chc-patients.pdf.

- 7.Hadley J, Cunningham P. Availability of safety net providers and access to care of uninsured persons. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1527–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falik M, Needleman J, Herbert R, Wells B, Politzer R, Benedict MB. Comparative effectiveness of health centers as regular source of care: application of Sentinel ACSC events as performance measures. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29:24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Probst JC, Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Association between community health center and rural health clinic presence and county-level hospitalization rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: an analysis across eight US States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laiteerapong N, Kirby J, Gao Y, Yu T, Sharma R, Nocon R, et al. Health care utilization and receipt of preventive care for patients seen at federally funded health centers compared to other sites of primary care. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:1498–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans CS, Smith S, Kobayashi L, Chang DC. The effect of community health center (CHC) density on preventable hospital admissions in medicaid and uninsured patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26:839–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nocon RS, Lee SM, Sharma R, Ngo-Metzger Q, Mukamel DB, Gao Y, et al. Health care use and spending for medicaid enrollees in federally qualified health centers versus other primary care settings. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta PP, Santiago-Torres JE, Wisely CE, Hartmann K, Makadia FA, Welker MJ, et al. Primary care continuity improves diabetic health outcomes: from free clinics to federally qualified health centers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myong C, Hull P, Price M, Hsu J, Newhouse JP, Fung V. The impact of funding for federally qualified health centers on utilization and emergency department visits in Massachusetts. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0243279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saloner B, Wilk AS, Levin J. Community health centers and access to care among underserved populations: A synthesis review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77:3–18. 10.1177/1077558719848283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CHA, Curtin T, Hart LG. Shortages of medical personnel at community health centers: implications for planned expansion. JAMA. 2006;295:1042–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurley R, Felland L, Lauer J. Community health centers tackle rising demands and expectations. Issue Br Cent Stud Heal Syst Chang. 2007;116. https://www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/5216. [PubMed]

- 18.Miller SC, Frogner BK, Saganic LM, Cole AM, Rosenblatt R. Affordable care act impact on community health center staffing and enrollment. J Ambul Care Manage. 2016;39:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savageau Ja, Ferguson WJ, Bohlke JL, Cragin LJ, O’Connell E. Recruitment and retention of primary care physicians at community health centers: a survey of Massachusetts physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011. 10.1353/hpu.2011.0071. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Health Resources and Services Administration. Primary Care Workforce Projections. 2022. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/data-research/projecting-health-workforce-supply-demand/primary-health. Accessed 27 Jun 2023.

- 21.White R, Keahey D, Luck M, Dehn RW. Primary care workforce paradox: A physician shortage and a PA and NP surplus. JAAPA. 2021;34:39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chin MH, Auerbach SB, Cook S, Harrison JF, Koppert J, Jin L, et al. Quality of diabetes care in community health centers. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuang E, Pourat N, Chen X, Lee C, Zhou W, Daniel M, et al. Organizational factors associated with disparities in cervical and colorectal cancer screening rates in community health centers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30:161–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff. 2007;26:1459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis SE, Nocon RS, Tang H, Park SY, Vable AM, Casalino LP, et al. Patient-centered medical home characteristics and staff morale in safety net clinics. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi AS, Selia E, McDonnell K. Stress and provider retention in underserved communities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telzak A, Chambers EC, Gutnick D, Flattau A, Chaya J, McAuliff K, et al. Health care worker burnout and perceived capacity to address social needs. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25:352–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson WJ, Cashman SB, Savageau JA, Lasser DH. Family medicine residency characteristics associated with practice in a health professions shortage area. 2009. https://adfm.org/media/1283/ferguson-et-al_fammed2009.pdf. [PubMed]

- 29.Morris CG, Johnson B, Kim S, Chen F. Training family physicians in community health centers: a health workforce solution. Fam Med. 2008;40:271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flinter M. From new nurse practitioner to primary care provider: bridging the transition through FQHC-based residency training. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;17(1):6 PMID: 22320872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis CS, Roy T, Peterson LE, Bazemore AW. Evaluating the teaching health center graduate medical education model at 10 years: Practice-Based outcomes and opportunities. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bureau of Health Workforce. Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME) Program. 2023. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding/apply-grant/teaching-health-center-graduate-medical-education. Accessed 28 Jun 2023.

- 33.Thomas T, Seifert P, Joyner JC. Registered nurses leading innovative changes. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016;21. 10.3912/OJIN.VOL21NO03MAN03. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Hartzler AL, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, Wagner EH. Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:240–5. 10.1370/AFM.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barclift SC, Brown EJ, Finnegan SC, Cohen ER, Klink K. Teaching health center graduate medical education locations predominantly located in federally designated underserved areas. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8:241–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight K, Miller C, Talley R. Health centers’ contributions to training tomorrow’s physicians. Natl Assoc Community Heal Centers. 2010;20005:1–25. http://www.nachc.com/client/thcreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C, Chen F, Mullan F. Teaching health centers: a new paradigm in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:1752–6. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182720f4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flinter M, Bamrick K. Training the next generation: residency and fellowship programs for nurse practitioners in community health centers. Middletown, CT: Community Health Center, Incorporated; 2017. https://www.weitzmaninstitute.org/NPResidencyBook. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Health Resources & Services Administration. Advanced nursing education nurse practitioner residency (ANE-NPR) program: Award Table 2019. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding-opportunities/ane-npr. Accessed 8 May 2020.

- 40.Garvin J. Bill would extend funding for dental public health programs. American Dental Association. 2019. https://lsc-pagepro.mydigitalpublication.com/publication/?i=568613&article_id=3307595&view=articleBrowser. Accessed 8 May 2020.

- 41.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Certified community behavioral health clinic expansion grants. 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/grant-announcements/sm-20-012. Accessed 8 May 2020.

- 42.Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(Suppl 1):383–406. 10.1111/1475-6773.12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Health Resources and Services Administration. National Health Center Program Uniform Data System (UDS) Awardee Data Table WFC: Workforce. 2019. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national/table?tableName=WFC&year=2019. Accessed 7 September 2022.

- 44.Holt DT, Armenakis AA, Harris SG, Feild HS. Research in organizational change and development. Res Organ Chang Dev. 2010;16:ii. 10.1108/S0897-3016(2010)0000018015. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Health Resources and Services Administration. State and Regional Primary Care Association Cooperative Agreements Workforce Funding Overview. 2020. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/funding/funding-opportunities/pca/workforce-funding-overview. Accessed 15 Oct 2020.

- 46.Zlateva I, Schiessl A, Khalid N, Bamrick K, Flinter M. Development and validation of the readiness to train assessment tool (RTAT). BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Damschroder LJ, Aron DCD, Keith RE, Kirsh SSR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. 2009;4:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miake-Lye IM, Delevan DM, Ganz DA, Mittman BS, Finley EP. Unpacking organizational readiness for change: an updated systematic review and content analysis of assessments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee S-YD, Review. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65:379–436. 10.1177/1077558708317802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Health Resources and Services Administration. What’s a Primary Care Association (PCA)?. 2023. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/technical-assistance/strategic-partnerships/primary-care-associations. Accessed 30 Aug 2023.

- 52.United States Department of Health and Human Services. United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regions. 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/education-and-outreach/educational-collaboration-with-ohrp/ohrp-educational-events-by-hhs-region/index.html. Accessed 23 Jun 2023.

- 53.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. 10.1007/BF02310555. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Health Care Workforce Innovation Act of, H.R.7307. 2024, 118th Cong. (2024). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/7307. Accessed 30 April 2025.

- 55.Bipartisan Primary Care and Health, Workforce Act. S.2840, 118th Congress. 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2840/text. Accessed 30 April 30 2025.

- 56.Health Resources and Services Administration. What Is Shortage Designation?. 2023. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation. Accessed 30 April 2025.

- 57.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript and can be shared upon request.