Abstract

Background

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) are a group of related chronic autoimmune diseases characterized by muscle inflammation and numerous other potential organ specific manifestations. People with IIM often present with reduced muscle strength, endurance, and aerobic capacity, directly impacting physical function and health-related quality of life. With emerging evidence supporting exercise in IIM, we sought to explore the experiences of exercise in people with IIM to further inform person-centered exercise interventions.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with IIM patients attending the rheumatology clinic at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, de-identified using alphanumeric codes, and analyzed thematically.

Results

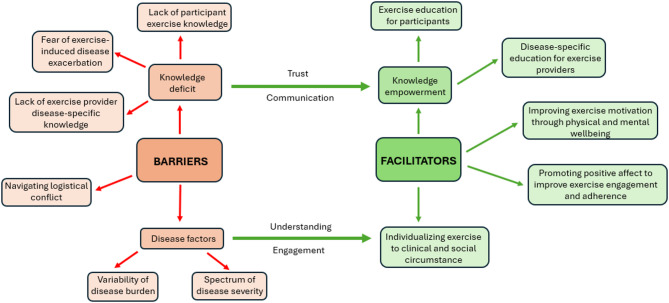

Twenty adults (women = 12, men = 8) with a mean age of 52.6 ± 12.9 years and a mean disease duration of 9.5 ± 8.9 years were included. Nine themes emerged: barriers to exercise (5 themes) and facilitators to exercise (4 themes). Barriers to exercise include (1) variability of disease burden (day-to-day symptom fluctuation, episodic flares, and side effects of treatments), (2) spectrum of disease severity, (3) fear of disease exacerbation, (4) navigating logistical conflict and (5) exercise and disease knowledge deficiency (lack of exercise knowledge in people with IIM and lack of disease-specific knowledge in exercise providers). Facilitators to exercise include (6) knowledge empowerment (participant education on the benefits of exercise in IIM to empower exercise engagement, and disease-specific education for exercise providers to facilitate understanding and trust with their patients) (7) improving exercise motivation through physical and mental wellbeing, (8) promoting positive affect to improve exercise engagement and adherence (social involvement and distractions), and (9) individualizing exercise to clinical and social circumstances.

Conclusions

People with IIM experience several barriers to exercise including disease severity, symptom unpredictability, fear of disease exacerbation, and difficulty scheduling exercise around medical appointments and life commitments. Education about the role of exercise and individualising exercise for people with IIM are central to improving exercise engagement and confidence. It is also important for health care providers to support people with IIM in making the link between physical and mental well-being and maintenance of independence and quality of life.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41927-025-00547-2.

Keywords: Idiopathic, Inflammatory, Myopathy, Exercise, Barriers, Facilitators, Qualitative

Background

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) are a group of related chronic autoimmune diseases characterized by muscle inflammation (myositis), and numerous other potential organ-specific manifestations. There are various subtypes of IIM including dermatomyositis (DM), immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), anti-synthetase syndrome (ASyS), overlap myositis (OM), inclusion body myositis (IBM) and polymyositis (PM). People with IIM present with reduced muscle strength and muscle endurance [1], poor quality of life and mental health [2], fatigue, pain and reduced aerobic capacity [3, 4]. The average peak oxygen consumption during exercise in people with IIM is significantly lower than their age- and sex-matched peers without IIM, potentially contributing to the limited functional capacity in activities of daily living [4]. Living with IIM can impact significantly on quality of life due to disease manifestations, requirement of repeated medical appointments, and treatment side effects [5, 6]. Qualitative research by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Myositis Working Group has identified a number of themes associated with living with IIM, through interviews, focus groups, and surveys, including (1) predominance of pain and fatigue, particularly when carrying out activities of daily living and physical activity (2) the emotional consequence of the disease, (3) symptom variability, particularly fatigue and pain which vary on a day-to-day and hour-to-hour basis, with both “good” days and “bad” days (4) limitations in participation in society, (5) insomnia, and (6) cognitive dysfunction [7, 8]. Another qualitative study has highlighted pain and fatigue as predominant symptoms in people with IIM, together with frequent symptom variation [9].

Despite initial controversy about whether exercise might be detrimental to the muscles of people with IIM, emerging evidence now strongly supports exercise as a safe and potentially effective treatment to improve health outcomes and reduce disability in people with IIM [4, 6–9]. In fact, exercise is increasingly becoming seen as a form of treatment for adult IIM and has been comprehensively reviewed in the literature [10]. Exercise was originally reported to be safe in a 1998 study involving people with DM and PM who underwent a 6 month aerobic exercise program, with a significant improvement in peak oxygen uptake (p < 0.02), peak isometric torque (‘muscle strength’; p < 0.03), and activities of daily living (p < 0.03) when compared to patients with DM and PM who were not performing structured exercise [10, 11]. In another study, endurance exercise training in conjunction with usual care has been shown to improve peak oxygen consumption (p = 0.010) when compared to usual care alone [12]. Despite emerging evidence describing exercise as a safe and effective treatment to improve health outcomes and reduce disability in people with IIM [3, 5–8], people with IIM have very low levels of physical activity compared to those without IIM [11, 12]. The specific reasons people with IIM are less physically active than healthy controls are unknown, and there is no published literature capturing how people with IIM perceive exercise and why this may be the case. In this study, we conducted qualitative interviews to understand the barriers and key facilitators to exercise in this group of patients in order to inform future programs to improve exercise engagement and subsequent health outcomes.

Methods

Aims

In this qualitative study, we sought to explore, describe, and understand the experiences and perceptions of exercise in people living with IIM to gain deeper insight into the barriers and facilitators to exercise to inform the design of person-centred exercise interventions, increase exercise engagement and adherence, and improve health-related outcomes in this population.

Study design

This study was a qualitative research study comprising individual interviews developed and conducted to capture barriers and facilitators to exercise in people with IIM. This study was conducted in accordance with the 2013 Version of the Declaration of Helsinki [13] and was approved by the Sydney Local Health District Research Ethics Committee [ethics approval number: 2023/PID03069]. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research was used to report on this study [see Additional file 1] [14].

Study setting

This study was a single site study conducted at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown, Sydney, Australia.

Participant characteristics

The study inclusion criteria included adults aged ≥ 18 years, diagnosed with IIM by a medical practitioner (IIM subtype was clinician assigned), attending the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, who could independently decide to take part in the study and provide informed consent. The study did not exclude individuals based on language proficiency; however, all participants spoke and understood English and did not require an interpreter. Enrolment decisions were guided by a purposive sampling framework [15] to ensure a representative participant cohort with respect to gender, ethnicity, disease subtype, disease duration (< 10 and ≥ 10 years), work status, and exercise participation. Participants were recruited until saturation of themes was achieved i.e. until no new themes were derived from the interviews, in line with standard practice to determine sample size in thematic analysis enquiry [16].

Data collection

Following consent, participant demographic information was collected by the research team (SF, NL), prior to the individual interviews (conducted by SF or NL), to guide purposive sampling. Baseline information included age, gender, work status, ethnicity, language/s spoken at home, highest education level received, disease type, disease duration, medications, and exercise participation. IIMs were categorized into subtypes including DM, PM, IMNM, ASyS, OM. Exercise was categorized according to frequency (number of days per week) and type (aerobic, strength/resistance, range of motion/flexibility, and a combination).

Individual interviews were approximately 20 min in duration, were conducted either online on Microsoft Teams, via telephone, or in-person in the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPAH) rheumatology clinic, between March and June 2024, audio-recorded using a Dictaphone or via Microsoft Teams, transcribed using Microsoft Word, and anonymized using alphanumeric codes to ensure patient confidentiality. An interview guide [see Additional file 2] was developed by the research team (SF, NL, MN).

Data analyses

Qualitative analysis of the interview transcripts was undertaken simultaneously by two authors (SF, NL) and reviewed by a third author (MN) and consumer advisor with lived experience of IIM to ensure a fair and an unbiased appraisal of the experiences expressed. Reflexive thematic analysis was adopted in accordance with qualitative research guidelines, ensuring findings were grounded in shared person experiences rather than imposed from existing concepts [23–26]. Data analysis software NVivo QSR international, release 1.5.1 (940) was used to facilitate qualitative analysis. During the transcription phase, participants were de-identified using alphanumeric codes. Initially, anonymized transcripts were read multiple times independently by SF and NL, and initial words/phrases (codes) that captured important experiences derived from the research questions were independently applied to each transcript to ensure rigorous analysis and to minimize researcher bias. The codes were then explored and refined during several discussions between SF and NL to conceptually group related codes to form themes and subthemes [23]. After a preliminary independent analysis of the data and several discussions, themes were reviewed by members of the research team (SF, NL, MN) and a consumer advisor to achieve consensus and ensure study results aligned with true patient experiences. De-identified key quotations from the transcripts were selected to illustrate themes and subthemes (supplementary 2 and 3), and coded using the participants gender, age, and subtype of IIM.

Results

Participants

Twenty adults (women = 12, men = 8) with IIM met study inclusion criteria and participated in the study, upon which saturation of themes was reached. The mean age of participants was 52.6 ± 12.9 years (minimum 27 years, maximum 71 years), with a mean disease duration of 9.5 ± 8.9 years (minimum 1 year, maximum 32 years). Purposive sampling ensured broad and representative participation in terms of IIM disease subtype (DM n = 6, ASyS n = 5, IMNM n = 3, PM n = 3 and OM n = 3). There were no participants with IBM. Most of the participants reported that they exercise (n = 14), with the frequency of exercise ranging from 1 day per week (n = 2), 2 to 3 days per week (n = 9), and > 5 days per week (n = 3). However, some did not exercise (n = 6). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 20)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 52.6 ± 12.9 |

| Gender, n | |

| Female | 12 |

| Male | 8 |

| Ethnicity, n | |

| Oceania | 4 |

| European | 8 |

| North/East Asian | 2 |

| Central/South/South-East Asian | 2 |

| North Africa and Middle Eastern | 2 |

| Other (South African, Caribbean) | 2 |

| Languages spoken at home, n | |

| English | 14 |

| Mandarin | 1 |

| Cantonese | 1 |

| Tagalog | 1 |

| Dari | 1 |

| French | 1 |

| Arabic | 1 |

| Highest level of education completed, n | |

| High school | 6 |

| Diploma/College | 4 |

| University degree (Bachelors) | 5 |

| University degree (Masters/Honours) | 5 |

| Work status, n | |

| No work | 9 |

| Part-time | 3 |

| Full-time | 8 |

| Disease duration, mean ± SD | 9.5 ± 8.9 |

| Disease duration, n | |

| < 5 years | 9 |

| 5 to 10 years | 3 |

| > 10 to 20 years | 6 |

| > 20 years | 2 |

| Disease subtype, n | |

| Dermatomyositis | 6 |

| Anti-synthetase syndrome | 5 |

| Polymyositis | 3 |

| Overlap myositis | 3 |

| Immune mediated necrotizing myopathy | 3 |

| Current medications, n | |

| Prednisone (range 2.5–25 mg, median 10 mg) | 10 |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) | 10 |

| Methotrexate | 8 |

| Mycophenolate | 7 |

| Rituximab | 5 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 |

| Other (Esomeprazole, Tacrolimus, Upadacitinib, Azathioprine) | 5 |

| IIM specific organ involvement, n | |

| Muscle* | 19 |

| Lung | |

| Interstitial lung disease | 10 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 3 |

| Skin | 11 |

| Joint | 3 |

| Disease status, n | |

| Clinically stable/in remission | 11 |

| Normal Creatine Kinase (CK) <250 units/L | 11 |

| Stable Manual Muscle Test (MMT26) | 4 |

| Active disease | 5 |

| Elevated CK (range 286–1877 units/L) | 3 |

| Skin** | 1 |

| Lung | 1 |

| No data | 4 |

| Major comorbidities, n | |

| Osteopenia/osteoporosis | 7 |

| Osteoarthritis | 4 |

| Heart disease | 4 |

| Diabetes | 3 |

| Hypertension | 3 |

| Obesity | 3 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 2 |

| Persistent soft tissue infection | 1 |

| Exercise frequency, n | |

| No exercise | 6 |

| 1 day per week | 2 |

| 2–3 days per week | 9 |

| 4–5 days per week | 0 |

| > 5 days per week | 3 |

| Exercise type, n | |

| Aerobic (exercise bike, walking, swimming) | 8 |

| Strengthening (gym-based or home-based, resistance bands/weights) | 3 |

| Range of motion (yoga, stretching) | 1 |

| All the above | 2 |

*1 participant had amyopathic dermatomyositis

**Participant with amyopathic dermatomyositis

Themes

Nine themes emerged that together constitute barriers (5 themes) and facilitators (4 themes) to exercise in people with IIM. Themes within barriers to exercise include (1) variability of disease burden, relating to day-to-day symptom fluctuation, episodic flares, and side effects to treatments, (2) spectrum of disease severity, (3) fear of disease exacerbation, (4) navigating logistical conflict and (5) exercise and disease knowledge deficiency, pertaining to lack of exercise knowledge in patients and disease-specific knowledge amongst exercise providers. Themes within facilitators to exercise include (6) knowledge empowerment, including participant education on the benefits of exercise in IIM to empower future exercise engagement, and disease-centered education for exercise providers to facilitate understanding and trust with their patients (7) improving exercise motivation through physical and mental wellbeing, (8) promoting positive affect to improve exercise engagement and adherence, particularly through social involvement and distractions, and (9) individualizing exercise to clinical and social circumstances.

Each theme and subtheme are described in further detail below. Illustrative quotations for each subtheme are included in the supplementary material (Supplementary 2 and 3), and a thematic schema summarizing the relationship between the themes is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Thematic schema

Variability of disease burden

Day to day symptom variability

This subtheme revealed that people with IIM experience varying symptoms that not only change from one day to the next, but also fluctuate in severity within a day from one hour to the next. Participants noted that they could vary from “fine” to “really exhausted in a matter of minutes without prediction”. Many participants described “good” and “bad” days, with “bad days” characterized by increased fatigue and therefore decreased exercise motivation.

Episodic flares

Symptom fluctuance was also compounded by episodic flares i.e. exacerbations in disease activity, which were also often associated with myalgia and fatigue, further decreasing exercise motivation. Some participants expressed difficulty engaging in set exercise programs, due to the unpredictability of symptom burden. Notably, 5 participants at the time of interviewing were experiencing a clinical flare of disease, and fear of post-exercise myalgia was a more prominent reported theme in this group than in those in clinical remission.

Medication side effect considerations

Medication side effects negatively impacted individuals, with steroids being noted to result in muscle weakness. Additionally, fear of infection whilst on immunosuppression resulted in decreased utilization of public gym equipment, and reduced engagement in communal exercise and the benefits of social interactions in this setting.

Spectrum of disease severity

Variation in organ manifestations and symptom burden

The severity and impact of disease varied significantly among participants, often depending on their individual organ manifestations. A diverse range of disease symptoms were noted, ranging from feeling “normal” to skeletal muscle weakness, myalgia, arthritis, interstitial lung disease and skin fragility. These manifestations uniquely impacted individuals’ ability to exercise, with one participant noting that “we all have different issues and it can affect you in different ways”. Notably, one participant had amyopathic dermatomyositis and therefore did not experience the muscle weakness and myalgia most reported. However, this participant reported that other manifestations such as skin fragility made it difficult to use equipment in the gym. Also, participants with lung-predominant involvement found that a pulmonary-rehabilitation based program was more effective for them in improving symptoms.

Experience of fatigue and impact on motivation

In addition to specific organ involvement, a theme that was more prominent in older participants (> 55 years) was the presence of debilitating constitutional symptoms, with the most notable being fatigue. Participants noted that there was both physical and ‘mental’ fatigue that directly impacted desire to exercise as it became “hard to get motivated to exercise the next day”.

Fear of disease exacerbation

Fear of precipitating disease flare

Participants reported significant anxiety that exercise could precipitate muscle inflammation and disease flare. Some indicated that their fear was reinforced by muscle pain post-exercise, compounded by the inability to determine whether the etiology was “because of the lactate from exercise or the inflammation”.

Fear of myalgia and prolonged recovery

Another common barrier to exercise in those with skeletal muscle manifestations was post-exercise myalgia and a prolonged recovery phase compared to pre-disease baseline. This discouraged engagement in future exercise, with one individual reporting their “muscles are tired and in pain, so I don’t want to exercise again.”

Fear of exacerbating individual comorbidities

Furthermore, there was significant variation among individuals in the perception of what constitutes a safe amount and type of exercise. This was in part due to comorbidities experienced by individuals, including spinal stenosis, osteoporosis, arrythmia and balancing issues in the context of muscle weakness.

Navigating logistical conflict

Managing treatment schedules

Participants identified that life commitments and medical appointment schedules conflicted with their ability to engage in routine exercise. Intravenous immunoglobulin schedule was identified as a major logistical conflict to exercise, as it was often reported to be associated with constitutional symptoms in the several days post-infusion. Participants also juggled multiple specialist appointments which impeded a regular exercise schedule, noting free days depend on “doctors’ appointments, and that changes every time”.

Juggling multiple commitments

Many participants were engaged in full-time or part-time work, which was also a major barrier to attending structured exercise programs during working hours. Furthermore, multiple participants reported family responsibilities including caring for children or grandchildren that reduced remaining time and energy for exercise commitments.

Exercise and disease knowledge deficiency

Lack of exercise knowledge in participants

Lack of exercise knowledge in participants was a reported barrier to engaging in exercise, particularly pertaining to anxiety of perceived “unsafe” exercises and the desire to engage in the exercises “most helpful” to their condition. Participants expressed that guidance from an exercise professional with specialist knowledge would improve their engagement in routine exercise.

Lack of disease-specific knowledge in exercise providers

Conversely, participants expressed that a perceived lack of disease-specific knowledge and its resultant implications on exercise safety in their exercise providers resulted in decreased feeling of confidence and trust in exercise prescriptions. Multiple participants reported negative experiences with exercise due to previous injury while engaging with exercise professionals who lack specific knowledge in autoimmune disease and IIM.

Knowledge empowerment

Empowering exercise knowledge

While participants felt they lacked confidence in their knowledge and understanding about safe and effective exercises for their disease, they reported that “knowledge and resource” would be helpful in establishing a routine. It was noted that an educational “program to help work out what exercises are helpful and best for [IIM]” would be welcomed by participants and would be helpful in engaging in future exercise through increased understanding of the most beneficial exercises for their disease, as well as learning the correct techniques to exercise safely. Others reported that improving their knowledge of safe exercises reduced their anxiety of precipitating disease exacerbation and would empower them to feel more confident in future exercise.

Enabling disease-specific knowledge

Participants stressed the importance of exercise professionals understanding their disease, indicating that the perception of disease-specific knowledge in their exercise providers was vital to trust and engagement in exercise prescriptions. This is evident in one participant’s experience, where she notes her exercise provider “did all her research, everything on me. So, I only go when it’s her classes”. The openness of exercise providers to education was also discussed, with positive participant perception noted when her physiotherapist “hadn’t heard of my disease before but looked it up. Did all his research and he was my lifesaver.”

Improving exercise motivation through physical and mental wellbeing

Participants reported that exercise was important in improving their mental and physical wellbeing and was a means of preserving their independence.

Improving mental wellbeing

Participants consistently expressed that engaging in regular physical activity and exercise enhanced their mental wellbeing. One participant who did not engage in regular exercise discussed that “physical health is about mental and physical wellbeing interaction,” noting that she feels “more stressed or depressed when my physical health is not good.” She identified improving her mental health as a motivator to resuming exercise. Exercise was also reported to be a way to “clear your mind” with the resultant perception of increased strength boosting mental health and confidence. A bi-directional positive relationship was identified where promotion of mental wellbeing was seen as a potential motivator for improving exercise engagement and adherence, particularly in those who did not exercise.

Improving physical wellbeing and maintaining independence

This subtheme highlighted the importance of exercise in enhancing physical wellbeing and maintaining independence. Exercise improved energy and general well-being, and in participants who previously exercised but no longer do so, it was noted that without it they “just feel tired.” Most participants also reported that at some point during their disease journey, they were reliant on other people to complete activities of daily living. This was a prominent theme in older participants > 55 years, who reported a sense of reliance on others for assistance, and “being a burden”. In this population, physical activity was reported to be used as a preventative measure against further deterioration, with one participant reporting her main motivator to continuing exercising was the desire “to do my own thing and be free and remain independent.” Promoting exercise to improve physical capacity, and to maintain and prolong independence is a powerful intrinsic motivator in people with IIM to persevere with exercise adherence.

Promoting positive affect to improve exercise engagement and adherence

Participants emphasized the benefits of social interaction, distraction, and motivational techniques as effective strategies for improving positive affect towards exercise, underscoring the importance of creating supportive exercise environments and utilizing diverse approaches to encourage positive exercise attitudes and behaviors.

Improving isolation with social exercise

Several participants who did not engage in regular exercise reported that due to the impacts of IIM on their lives, they felt socially isolated from both their friends and family and did not have anyone to exercise with. Conversely, other participants identified that the social aspect of exercise was a key factor in their willingness and commitment to engage in exercise. For example, many people felt more motivated to exercise if they had friends to exercise with, and the social aspect was an added incentive to commence and maintain exercise routines.

Utilizing exercise distraction

This subtheme highlighted the role of distractions, such as music, in motivating people with IIM to engage in exercise. Many participants did not intrinsically enjoy exercise but noted that distractors such as music would improve enjoyment and performance, with one participant reflecting that when “certain songs come on that people really like…they work a bit harder”. Interactive exercises such as Zumba or dancing were among other suggested ways to exercise “without feeling as though you are necessarily exercising”.

Motivational communication and recognition of achievement

With many participants lacking intrinsic enjoyment of exercise, a common reported sentiment was that external motivating comments from their exercise providers helped in adhering to and engaging in future exercise. As one participant aptly comments, “when you’re sick and you’re on that many meds, the last thing you want to do is exercise…so lots of reassurance or pick up…and pumping them up…”. Other participants note that recognition of achievement is important for exercise confidence, and goal-oriented exercise to “set their goals and gains” and enhance continued exercise engagement.

Individualizing exercise to specific clinical and social circumstances

This theme emphasized the importance of individualizing exercise to peoples’ individual and social circumstances. Participants reported that their exercise routine needs to be specific to their symptoms and disease manifestations and modified depending on how they feel on a day-to-day basis. Participants also reported that the selection of exercise days should be considered around treatment schedules and factor variables such as perceived post-IVIG fatigue and medical appointments, as well as social commitments, noting that many participants have young families and work considerations.

Discussion

While the beneficial role of exercise in IIM is becoming increasingly recognized, people with IIM engage in lower levels of exercise when compared to their peers [11]. It is therefore important to understand the positive and negative exercise experiences in people with IIM to best adapt to their individual needs and ultimately enhance exercise engagement and adherence. To our knowledge, there have been no qualitative studies of person-perceived barriers and facilitators to exercise in IIM, and our study reveals novel findings that can be utilized in creating future exercise interventions in people with IIM. Considering the similarity in symptoms and manifestations between IIM and other rheumatic diseases such as systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, our novel findings may also be transferable to these populations.

While all our study participants had positive views on the benefits of exercise, our study revealed that there are some disease-related barriers to exercise that people with IIM face. The unpredictability of symptoms from hour-to-hour or day-to-day, compounded by fatigue and episodic flares, were among the most prominent barriers to engaging in regular exercise. This is not surprising, considering that symptom fluctuation is commonly reported in other qualitative studies in IIM [8, 17, 18], with fatigue being the second most reported symptom in people with IIM according to the OMERACT trial [19]. Particularly pertinent in that study was the reported discrepancy between patient-perceived and healthcare provider-perceived disease burden, with over 80% of patients reporting fatigue, but only around two-thirds of healthcare providers recognizing this factor. This is also reflected in qualitative literature with the perception that many features of IIM such as fatigue and symptom fluctuations were “invisible” and were therefore under-recognized by healthcare providers [9]. An interesting finding in this study is that even participants in ‘remission’ with normal CK and MMT26 described a decrease in their exercise capacity compared to baseline, and fluctuating levels of fatigue. This gap in symptom burden perception highlights the importance of exercise professionals understanding the impact of fatigue and symptom unpredictability which can occur even in those without clinical disease activity, and the need to recognize that their participants may require more flexibility with structured exercise programs.

Despite the publication of recent studies [20, 21] highlighting the anti-inflammatory role of exercise and its potential to reduce disease activity in IIM and other rheumatic diseases, many participants reported heightened anxiety that exercise might precipitate muscle inflammation and result in a disease flare. This is possibly a relic from literature prior to the 1990’s indicating that exercise was contraindicated because it could exacerbate muscle inflammation in IIM [22]. Furthermore, participants seemed unable to differentiate post-exercise myalgia and fatigue from a myositis flare, with concerns regarding prolonged post-exercise recovery posing a major barrier to participation in regular exercise. Reassuringly, numerous studies have not demonstrated an increase in systemic markers of muscle inflammation (including CK, CRP and ESR) after exercise [23, 24], with notable findings revealing that muscle lactate following a 12-week endurance exercise program reduced by 35% when compared to pre-intervention baseline. This knowledge discrepancy stresses the need for evidence-based person-centered education, to address a modifiable barrier to exercise engagement.

The lack of sufficient patient education regarding disease and management is also reflected in other studies of adults with IIM, with an expressed need for disease information and potential treatments [25]. This correlates with our study results, with most patients expressing the desire for education regarding the evidence-based role for exercise in IIM, as well as guidance on safe and effective exercise. A recent meta-analysis assessing the impacts of education in rheumatoid arthritis patients [26] demonstrated that education significantly improved disease activity (p < 0.00001), pain (p < 0.00001), and general health (p < 0.00001). Similarly, studies in systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrated that lack of patient education and low health literacy was a risk factor for higher disease activity and disease flares [26, 27]. Evidence shows that in clinical practice, people are more likely to engage in an activity if they expect an improvement in health outcomes [28]. Therefore, patients should be educated by their health care providers on the benefits of exercise for their condition to maximize adherence [29].

A novel finding of this study was that a major barrier for adults with IIM engaging with supervised exercise is the perceived lack of disease-specific knowledge amongst their exercise providers. Participants felt that this lack of knowledge meant that their exercise providers were unable to formulate disease-specific safety considerations, resulting in reduced trust and subsequent engagement. This is problematic as existing data show that greater trust between patients and their healthcare providers is associated with less patient-reported symptoms, better quality of life, and greater treatment satisfaction [30] and that this trust hinges mostly on healthcare providers’ communication skills and their knowledge of the patient [31]. In IIM, disease-specific knowledge is particularly relevant due to the heterogeneity of disease manifestations and experienced symptoms. While many people experience skeletal muscle involvement and subsequent weakness, other manifestations may include skin rashes, dysphagia, dilated cardiomyopathy, interstitial lung disease, and constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss and fatigue [32]. Given the complexity and wide range of symptoms and manifestations in IIM, it is important that healthcare providers are well educated about the disease to ensure that exercise is delivered in a safe and effectively tailored manner. It is also important that this education is delivered in a meaningful way, considering peoples’ real-world experiences. Multidisciplinary in-person education sessions with supplementary online modules may provide an opportunity for interaction between physicians, people with lived experience, and exercise providers, to better understand the experience of exercise. This study provides nuanced insights from people with IIM about their real-world experiences with exercise that could help to educate health care providers.

Our study has also found that a major motivator for regular and continued exercise engagement was the potential for social bonding. Participating in group exercises or even unstructured walks with friends provided a sense of camaraderie and community. These social interactions made the exercise experience more enjoyable and less daunting, transforming it from a solitary task into a shared experience. Participants found that exercising with others not only offered support and encouragement but also created opportunities for forming new friendships and strengthening existing relationships. The importance of highlighting the social aspects of exercise is underpinned by current literature that demonstrates the reciprocal relationship between physical inactivity and loneliness, with loneliness having been identified as a risk factor for physical inactivity and vice versa [33, 34]. Conversely, there is emerging evidence to suggest that social exercise versus exercising alone is associated with improved pain tolerance [35], and social bonding is potentially linked to improved exercise performance [36]. Furthermore, the development of community-based exercise programs for people with IIM, fosters social interaction and may function as a support group for an uncommon condition, an additional aspect to encourage exercise adherence.

Many participants also identified that they did not intrinsically enjoy exercise and that the presence of positive distractors during exercise, such as music, could help augment the exercise experience. Exercising with music has been shown to increase blood flow, improve physiological functioning and decrease perceived exhaustion [37]. Importantly, enhanced participant enjoyment is linked to adherence [38], which could be a potential consideration to facilitate exercise adherence in this population. This effect is not completely confined to music, with other distractions such as watching an enjoyable television show during exercise, resulting in improved mood when compared to exercise without distraction [39].

Therefore, due to the heterogeneity of symptom burden, comorbidities and social circumstances that affect exercise engagement in people with IIM, it is vital that exercise prescriptions are individualized to the persons’ clinical and social circumstance. As alluded to, it is important that exercise professionals understand the individual disease manifestations, symptoms, and medication side-effect profiles, so that exercise can be tailored accordingly. It is also essential to consider participants’ treatment schedules, to ensure the exercise schedule does not conflict with life commitments, medical appointments, or treatment-related constitutional symptoms. It is also relevant for exercise providers to consider participants’ energy level and symptom fluctuations, which may require more flexibility for engagement in structured exercise programs.

There were some limitations in our study. The participants in our study were limited to those with IIM who attend RPAH, which is an urban quaternary hospital in Sydney, Australia and serves as a statewide referral center for IIM. Our data may not be representative of the experience of people with IIM who live in rural settings where one could postulate different patient and healthcare team factors. The participants in our study were recruited from an exclusively outpatient setting, and therefore our findings may have limited applicability to patients who are more acutely unwell in an in-patient setting. Finally, we were not able to recruit any patients with IBM due to its scarcity within the clinic we recruited from. This is pertinent as the IBM population is distinct from other IIMs in certain key characteristics that are likely to impact exercise, tending to be older (age of onset > 45 years) with an asymmetric distal muscle distribution of involvement [40]. While pharmacologic therapies have had little success in this population [41], emerging evidence has shown exercise programs can preserve muscle function and increase exercise capacity [42]. Further research into the views of exercise in this unique entity is needed in order to guide development of relevant exercise programs. Online interviews are an increasingly common alternative to traditional face-to-face interviews and provide out-of-hours flexibility for participants, as well eliminating travel time and scheduling conflicts. However, conducting interviews online has some limitations, such as the inability to easily respond to participants’ body language and emotional cues, as well as potential technological difficulties [43], which may influence the experience and quality of the interview. It is worth noting that our study included a balanced distribution of online and in-person interviews (n = 11, in-person; n = 9, online).

Future qualitative research should explore perspectives on exercise in a broader range of myositis subtypes, including inclusion body myositis, to better understand variations in experiences and perceived barriers across all myositis subtypes. A qualitative study incorporating both inpatients and outpatients from diverse demographic backgrounds across Australia would enhance the generalizability of findings. This approach would provide deeper insights into how factors such as disease subtype and social determinants influence engagement with exercise. Additionally, investigating healthcare providers’ perspectives alongside patient experiences could offer a more comprehensive understanding of how exercise is integrated into existing healthcare pathways and identify opportunities for improving exercise recommendations and support in clinical practice.

Conclusion

People with IIM experience several barriers to exercise including disease impact and symptom unpredictability. There is also a fear of disease exacerbation and prolonged recovery following exercise, as well difficulties navigating scheduling conflicts with medical appointments and life commitments. Education and reassurance for participants on the evidence for exercise in IIM, in combination with a novel finding of the importance of disease-centred education for healthcare professionals, are key facilitators. Other key exercise facilitators for some people with IIM include leveraging the benefits of social interactions and using distractions, which together may ultimately improve engagement and adherence to exercise in this population.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the twenty participants who took part in this study, the RPAH immunology department, and the RPAH rheumatology department clinicians and nurses for their support with recruitment, and Dr Shannon Taylor from the University of Sydney for REDCap support. We would like to thank our lived experience expert for her critical appraisal of the study results. We also acknowledge and thank members of the Myositis Research Consumer Panel for their study design feedback. The Myositis Research Consumer Panel is led by the Myositis Discovery Program at Murdoch University and the Perron Institute, partnering with the Myositis Association of Australia and the Consumer and Community Involvement Program (Perth, WA).

Abbreviations

- IIM

Idiopathy inflammatory myopathies

- RPAH

Royal Prince Alfred Hospital

- DM

Dermatomyositis

- PM

Polymyositis

- IMNM

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy

- ASyS

Anti-synthetase syndrome

- IBM

Inclusion body myositis

- OM

Overlap myositis

Author contributions

All authors were involved in drafting or revising this study critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to submit for publication. SF and NL had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (GNT).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the 2013 Version of the Declaration of Helsinki [13] and was approved by the Sydney Local Health District Research Ethics Committee [ethics approval number: 2023/PID03069]. All participants signed informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Natalie Li and Stephanie Frade contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Alexanderson H, Regardt M, Ottosson C, Munters LA, Dastmalchi M, Dani L, et al. Muscle strength and muscle endurance during the first year of treatment of polymyositis and dermatomyositis: A prospective study. J Rhuematol. 2018;45(4):538–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regardt M, Welin Henriksson E, Alexanderson H, Lundberg IE. Patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis have reduced grip force and health-related quality of life in comparison with reference values: an observational study. Rheumatology. 2010;50(3):578–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alemo Munters L, Dastmalchi M, Andgren V, Emilson C, Bergegård J, Regardt M, et al. Improvement in health and possible reduction in disease activity using endurance exercise in patients with established polymyositis and dermatomyositis: A multicenter randomized controlled trial with a 1-Year open extension followup. Arthritis Care Res (2010). 2013;65(12):1959–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiesinger GF, Quittan M, Nuhr M, Volc-Platzer B, Ebenbichler G, Zehetgruber M, et al. Aerobic capacity in adult dermatomyositis/polymyositis patients and healthy controls. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sultan SM, Ioannou Y, Moss K, Isenberg DA. Outcome in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myositis: morbidity and mortality. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(1):22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Vlekkert J, Hoogendijk JE, de Visser M. Long-term follow-up of 62 patients with myositis. J Neurol. 2014;261(5):992–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexanderson H, Del Grande M, Bingham CO 3rd, Orbai AM, Sarver C, Clegg-Smith K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and adult patients’ disease experience in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Report from the OMERACT 11 myositis special interest group. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(3):581–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regardt M, Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L, Sarver C, Björn A, Lundberg IE, et al. Patients’ experience of myositis and further validation of a myositis-specific patient reported outcome Measure - Establishing core domains and expanding patient input on clinical assessment in myositis. Report from OMERACT 12. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(12):2492–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldroyd A, Dixon W, Chinoy H, Howells K. Patient insights on living with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy and the limitations of disease activity measurement methods – a qualitative study. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiesinger GF, Quittan M, Graninger M, Seeber A, Ebenbichler G, Sturm B, et al. Benefit of 6 months long-term physical training in polymyositis/dermatomyositis patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(12):1338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinto AJ, Yazigi Solis M, de Sá Pinto AL, Silva CA, Maluf Elias Sallum A, Roschel H, et al. Physical (in)activity and its influence on disease-related features, physical capacity, and health-related quality of life in a cohort of chronic juvenile dermatomyositis patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(1):64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramdharry GM, Wallace A, Hennis P, Dewar E, Dudziec M, Jones K, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise performance and factors associated with aerobic capacity in neuromuscular diseases. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(6):683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Medical Association Declaration. Of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd ed. ed. Saint Paul, MN: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oldroyd A, Dixon W, Chinoy H, Howells K. Patient insights on living with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy and the limitations of disease activity measurement methods - a qualitative study. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortega C, Limaye V, Chur-Hansen A. Patient perceptions of and experiences with inflammatory myositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16(7):341–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mecoli CA, Park JK, Alexanderson H, Regardt M, Needham M, de Groot I, et al. Perceptions of patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: an international OMERACT study. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(1):106–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexanderson H, Dastmalchi M, Esbjörnsson-Liljedahl M, Opava CH, Lundberg IE. Benefits of intensive resistance training in patients with chronic polymyositis or dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):768–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alemo Munters L, Dastmalchi M, Andgren V, Emilson C, Bergegård J, Regardt M, et al. Improvement in health and possible reduction in disease activity using endurance exercise in patients with established polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with a 1-year open extension followup. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(12):1959–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundberg IE, Nader GA. Molecular effects of exercise in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4(11):597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexanderson H, Munters LA, Dastmalchi M, Loell I, Heimbürger M, Opava CH, et al. Resistive home exercise in patients with recent-onset polymyositis and dermatomyositis -- a randomized controlled single-blinded study with a 2-year followup. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(6):1124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alemo Munters L, Dastmalchi M, Katz A, Esbjörnsson M, Loell I, Hanna B, et al. Improved exercise performance and increased aerobic capacity after endurance training of patients with stable polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(4):R83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chérin P, Pindi Sala T, Clerson P, Dokhan A, Fardini Y, Duracinsky M, et al. Recovering autonomy is a key advantage of home-based Immunoglobulin therapy in patients with myositis: A qualitative research study. Med (Baltim). 2020;99(7):e19012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Z, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Zhou R, Ye X, Chen Z, et al. The effects of patient education on psychological status and clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:848427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maheswaranathan M, Cantrell S, Eudy AM, Rogers JL, Clowse MEB, Hastings SN, et al. Investigating health literacy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a descriptive review. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20(12):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steckler A, McLeroy KR, Hotzman D, Godfrey H, Hochbaum. (1916–1999): from social psychology to health behavior and health education. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Collado-Mateo D, Lavín-Pérez AM, Peñacoba C, Del Coso J, Leyton-Román M, Luque-Casado A et al. Key factors associated with adherence to physical exercise in patients with chronic diseases and older adults: an umbrella review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, Hasler S, Krummenacher P, Werner C, et al. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0170988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson SD, Raeke LH. Patients’ trust in physicians: many theories, few measures, and little data. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):509–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oldroyd A, Lilleker J, Chinoy H. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies - a guide to subtypes, diagnostic approach and treatment. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(4):322–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shvedko A, Whittaker AC, Thompson JL, Greig CA. Physical activity interventions for treatment of social isolation, loneliness or low social support in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2018;34:128–37. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galper D, Trivedi M, Barlow C, Dunn A, Kampert J. Inverse association between physical inactivity and mental health in men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan P, Rickers K. The effect of behavioral synchrony in groups of teammates and strangers. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2013;11.

- 36.Davis A, Taylor J, Cohen E. Social bonds and exercise: evidence for a reciprocal relationship. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terry PC, Karageorghis CI, Curran ML, Martin OV, Parsons-Smith RL. Effects of music in exercise and sport: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2020;146(2):91–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madison G, Paulin J, Aasa U. Physical and psychological effects from supervised aerobic music exercise. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(6):780–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Privitera GJ, Antonelli DE, Szal AL. An enjoyable distraction during exercise augments the positive effects of exercise on mood. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13(2):266–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg SA. Inclusion body myositis: clinical features and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(5):257–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skolka MP, Naddaf E. Exploring challenges in the management and treatment of inclusion body myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2023;35(6):404–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnardottir S, Alexanderson H, Lundberg IE, Borg K. Sporadic inclusion body myositis: pilot study on the effects of a home exercise program on muscle function, histopathology and inflammatory reaction. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35(1):31–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cater JK. Skype a cost-effective method for qualitative research. Rehabilitation Counselors Educators J. 2011;4(2):3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.