Abstract

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) is among the most common sexually transmitted infections and is associated with substantial health and economic burdens. Vaccination may offer a promising strategy for its global control.

Methods

A deterministic, age-structured mathematical model was applied to assess the global impact of a hypothetical CT vaccine. The analysis explored a range of assumptions for vaccine efficacy against infection acquisition (), duration of protection, and coverage, across both adult catch-up and adolescent-targeted vaccination strategies.

Results

Vaccinating individuals aged 15–49 years beginning in 2030 with a vaccine of and 20-year protection, scaled to 80% coverage by 2040, reduced global CT prevalence, incidence rate, and annual new infections in 2050 by 26.2%, 32.3%, and 26.5%, respectively. Cumulatively, 717 million infections were averted by 2050. The number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one infection declined from 23.3 in 2035 to 10.6 in 2050, with variation across population groups: 5.9 for those aged 15–19 years, 7.5 for those aged 10–14 years, and 3.0 for high-risk groups. Vaccine impact increased with higher , longer protection duration, and inclusion of breakthrough effects on infectiousness and infection duration. While adolescent vaccination achieved substantial impact, its benefits accrued more slowly than those of adult-targeted strategies.

Conclusions

Vaccination against CT can substantially reduce global infection burden, even with moderate efficacy. Impact is enhanced by targeted strategies, with adolescent vaccination aiding long-term control and catch-up programs ensuring immediate benefit. These findings highlight the urgency of vaccine development and integration into public health efforts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s44263-025-00181-7.

Keywords: Vaccine impact, Number needed to vaccinate, Cost-effectiveness, Transmission dynamics, Sexually transmitted infection, Global health

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) is a globally prevalent bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) [1]. The majority of infections are asymptomatic, regardless of anatomical site, which contributes to ongoing transmission and delayed diagnosis [2]. If left untreated, CT infection can result in serious reproductive and urogenital complications [3–7]. In women, these include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy; in men, they include urethritis and epididymitis [3–7].

In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 128.5 million new CT infections globally among individuals aged 15–49 years, with a prevalence of 4.0% among women and 2.5% among men [8, 9]. Regional prevalence varied substantially, ranging from 1.9% to 6.8% among women and from 1.2% to 4.0% among men [8, 9]. These infection levels highlight the need for a fundamental control strategy to mitigate the substantial health and economic burdens associated with CT infection [10].

Despite decades of control efforts, CT infection remains widespread. Large-scale “test and treat” programs have shown inconsistent impact across settings and may not have achieved sustained reductions in prevalence [2, 11, 12]. These programs have also raised concerns about overdiagnosis, overtreatment, relationship strain, and potential contributions to antimicrobial resistance [2, 13, 14]. Moreover, early detection and treatment may hinder the development of protective immunity, increasing susceptibility to reinfection and limiting herd immunity, potentially undermining long-term control efforts [15–18].

Evidence indicates that natural CT infection may confer partial immunity, supported by animal studies and epidemiological observations such as age-related declines in prevalence, reduced organism load and couple concordance with age, and treatment-related attenuation of immunity [19–23]. Modeling studies estimate that primary infection provides over 65% protection against reinfection [18, 24]. These findings support the concept and feasibility of a partially efficacious vaccine, although CT vaccine development remains in its early stages [25–28].

This study applied mathematical modeling to evaluate the potential impact of a prophylactic CT vaccine, once available, at both the global level and within each WHO region. The analysis examined reductions in prevalence, incidence rates, and the annual number of new infections under varying scenarios of vaccine efficacy, duration of protection, and population coverage. It also explored the number of vaccinations needed to avert one infection and assessed the impact of targeted vaccination strategies, including prioritization by age, sex, and sexual risk group, to identify approaches that could maximize public health benefits while reducing costs. These analyses are intended to guide vaccine development and implementation by identifying preferred product characteristics and projecting potential cost-effectiveness and return on investment, following established frameworks applied to other infectious diseases [29–34].

Methods

Scope of study

The mathematical model was applied separately to each of the six WHO regions: African Region, Region of the Americas, South-East Asia Region, European Region, Eastern Mediterranean Region, and Western Pacific Region. Regional estimates were first generated, and global estimates were then obtained by aggregating results across all regions.

Mathematical model

This study adapted a deterministic, compartmental, population-level dynamic model originally developed to characterize CT transmission dynamics and assess the impact of CT vaccination in the United States (US) population [35]. The model draws on established frameworks for modeling STI transmission dynamics [18, 23, 36–44] and the impact of vaccination [31–33, 45–48]. A basic schematic representation of the model is presented in Additional file 1: Fig. S1, and Additional file 1: Section S1 and Table S1 provide a description of the model structure and equations. A comprehensive account of the model’s structure and parameterization is available elsewhere [35].

The population was stratified by age, sex, sexual risk behavior, CT infection status, infection stage, and vaccination status [35]. Infection dynamics were governed by sets of nonlinear differential equations, with each set representing a specific combination of age and sexual risk group [35]. To streamline the model structure, different modes of sexual transmission were not differentiated, and transmission among men who have sex with men was not explicitly represented [35]. Given the relatively small contribution of this transmission route compared to heterosexual transmission, this simplification is not likely to meaningfully influence the results. Additionally, because the input data were specific to urogenital infections, the model did not account for infections at extragenital sites [35]. All analyses for all regions were conducted under the assumption that CT infection was at endemic equilibrium.

The model divided the population into 20 5-year age groups (0–4, 5–9, 10–14, …, 95–99 years), with primary analyses focusing on individuals aged 15–49 years [35]. Sexual debut was assumed to occur at age 15 or later, with individuals under 15 considered sexually inactive [35]. Sexual risk behavior was assumed to vary with age, with older adults gradually transitioning out of sexual activity [35]. Within each age group, individuals were further categorized into five sexual risk groups, ranging from low to high risk based on sexual behavior [35].

The distribution of individuals across sexual risk groups within each region was modeled using a gamma distribution, motivated by empirical data on the number of sexual partners [49]. Variation in sexual risk behavior across risk groups was modeled using a power-law function, informed by sexual partnership data [50] and further supported by findings from network analyses and other modeling studies [51–54].

Sexual mixing across age groups and risk behavior groups—reflecting patterns of partnership formation influenced by age and risk behavior—was modeled using two distinct mixing matrices: one for age and one for risk behavior [35, 44]. The age-based matrix provided the probability that an individual in a given age group would form a sexual partnership with someone in another age group [44, 55, 56]. Similarly, the risk-based matrix specified the probability of partnership formation between individuals from different risk groups [44, 55, 56].

Each matrix consisted of two components: one capturing strictly assortative mixing, where individuals form partnerships exclusively within their own age or risk group, and another capturing proportionate mixing, where partnerships are formed without preference across all groups [44, 55, 56]. Proportionate mixing implies that contact rates between groups are proportional to their relative population sizes and their rates of partnership formation, resulting in random, homogeneous interactions [44, 55, 56].

Risk behavior among men was derived through balancing equations for sexual partnership rates, ensuring that the number of partnerships formed by men in a given subpopulation (defined by age and risk group) with women in another subpopulation matched the number of partnerships formed by women in the latter group with men in the former [35, 44, 55].

The force of infection was determined by sexual partner change rates, CT transmission probabilities per sexual act and per partnership, and mixing patterns across age and risk groups [35].

The natural history of CT infection was modeled as progression from susceptibility to symptomatic or asymptomatic infection, followed by a temporary period of natural immunity, as supported by empirical evidence [1, 18, 36, 57]. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals could receive treatment, albeit at different rates [35].

Model implementation, calibration, and analysis were conducted using MATLAB R2019a (the MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Simulations were partially performed using the Red Cloud computational infrastructure at Cornell University.

Data sources

Model parameters were based on knowledge of CT natural history, epidemiology, and patterns of sexual behavior, as summarized in Additional file 1: Table S2 and described in detail—including parameter definitions, justifications, and data sources—elsewhere [35]. Key sources informing parameter selection included a review of existing STI transmission models [36] and the parameterization approach adopted by the WHO STI model [1, 57].

Demographic data, including population size by age and sex, as well as historical and future projections, were obtained from the United Nations’ World Population Prospects database [58]. Sex-specific CT prevalence estimates for each WHO region were based on WHO’s 2020 estimates [8, 9]. CT treatment rates for symptomatic and asymptomatic infections were informed by the parameterization approach adopted in the WHO STI model [1, 57].

The shape and scale parameters for the gamma distribution describing the distribution of females across sexual risk groups were informed by analyses of the number of sexual partners reported over the past 12 months [49]. For males, the scale parameter was assumed to be the same as that for females, while the shape parameter was estimated through model fitting.

The exponent parameter governing the power-law function describing the variation in sexual risk behavior among females was informed by prior studies [50, 59–61], whereas the corresponding parameter for males was determined through model fitting. Notably, the overall partnership change rate for females was treated as a fitted parameter and varied by region. Although the distributions of sexual risk behavior among females followed a similar pattern across regions, the overall level of sexual risk behavior differed due to region-specific calibration.

Variation in coital act frequency with age was derived from empirical data on general population sexual behavior [18, 62], while variation in sexual partner change rates by age was informed by patterns observed in the US population [35].

Model fitting

The model was calibrated to WHO sex-specific estimates of CT prevalence for 2020 across WHO regions (Additional file 1: Table S3). These estimates encompass both clinically documented and undocumented infections, enabling the model to capture the full burden of CT. Because the model assumed endemic equilibrium for CT prevalence, these 2020 estimates not only were applied for that year but also were assumed to remain constant over time in the absence of vaccination. Accordingly, calibration was based on the assumption of stable prevalence over time in the no-vaccination counterfactual scenario, rather than relying solely on a single year’s data.

Calibration was performed by minimizing an objective function defined as the sum of squared differences between model-predicted and observed prevalence for women and men, following an established approach [35, 55, 59, 63]. The model compared predicted prevalence values with WHO estimates for each sex and penalized deviations accordingly.

To minimize this objective function, three parameters were optimized during the calibration process: the overall partnership change rate for females, the shape parameter of the gamma distribution for males, and the exponent of the power-law function for males. Model fit was evaluated using formal goodness-of-fit metrics, including the sum of squared errors and root-mean-square error. Demographic processes, including birth and mortality rates, were modeled using a published methodology [55, 63], with rates estimated by fitting to age- and sex-specific population distributions for each region.

During the calibration process, the model was run from 1950 onward to allow sufficient time for CT transmission dynamics to reach endemic equilibrium. Initial CT prevalence was set at 15% for women and 10% for men—values higher than the expected equilibrium levels—to accelerate convergence to steady state. Notably, the equilibrium prevalence is determined by model parameters and is independent of the initial conditions; however, the choice of initial conditions influences the speed at which equilibrium is attained.

This calibration approach enabled a uniquely identifiable parameter solution during the fitting process. The calibration procedure employed the Nelder-Mead simplex method [64], a robust, derivative-free numerical optimization algorithm commonly used for minimizing multidimensional functions.

Vaccine efficacies

The conventional measure of a vaccine’s effect is its efficacy against infection acquisition (), which reflects the proportional reduction in susceptibility to infection following vaccination [33, 35, 46]. However, as CT vaccines are anticipated to provide only partial protection against acquisition [26, 47], it is also important to consider how vaccination influences the natural history and infection transmission among individuals who become infected despite vaccination [33, 35, 47, 65, 66].

To capture these “breakthrough” effects, two additional measures of vaccine efficacy are considered: and . represents the proportional reduction in infectiousness among vaccinated infected individuals compared to unvaccinated infected individuals [33, 35, 46], while denotes the proportional reduction in the duration of infection among vaccinated infected individuals compared to unvaccinated counterparts [33, 35].

Given that protection from a CT vaccine is likely to be finite rather than lifelong [26, 47], duration of protection is a critical determinant of vaccine impact. The primary analysis assumed an average protection duration of 20 years, to cover the span from sexual debut through 35 years of age, the period of highest infection risk [18, 67]. Achieving this duration may require a primary series with booster doses. Protection was modeled to wane at a constant rate, consistent with an exponentially distributed duration of protection.

Measures of vaccine impact

The population-level impact of a CT vaccine is shaped by both its direct effects (, , , and duration of protection) and its indirect effects through reduced onward transmission within the population [35]. Vaccine impact was evaluated by comparing prevalence, incidence rate, and annual new infections under vaccination scenarios against a counterfactual scenario without vaccination.

Additional evaluation was conducted using the number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one CT infection over a defined time horizon, calculated as the ratio of total vaccinations administered to infections averted within that period [35]. This metric serves as a proxy for cost-effectiveness, capturing the epidemiologic effectiveness of vaccination in the absence of cost data, as the per-dose cost of the vaccine is not yet established.

A programmatic perspective was adopted, assessing the number of vaccinations required to prevent one infection from the initiation of vaccination through a specified year. Vaccine impact was estimated separately for each WHO region and at the global level.

Vaccine program scenarios

The vaccine program scenarios examined are summarized in Table 1. The first vaccination scenario represented an adult-focused program, assuming the introduction of a CT vaccine in 2030 with an average protection duration of 20 years. The vaccination targeted individuals aged 15–49 years, regardless of current or prior CT infection (catch-up vaccination strategy).

Table 1.

Summary of vaccine program scenarios evaluated in the study

| Scenario | Eligibility criteria | Purpose of scenario |

|---|---|---|

| Adult vaccination scenario | Individuals aged 15–49 years | Optimizing vaccine use and maximizing population-level impact within a feasible timeframe |

| Adolescent vaccination scenario | Individuals aged 10–14 years | Evaluating the potential long-term implementation strategy for a chlamydia vaccine |

| Adult vaccination scenario with vaccination based on the following: | ||

| • Age | Targeting individual age groups separately | Assessing the impact of targeting specific age groups and its implications for cost-effectiveness |

| • Sexual risk behavior | Targeting individual sexual risk groups separately | Assessing the impact of targeting specific sexual risk groups and its implications for cost-effectiveness |

| • Sex | Targeting either women or men exclusively | Assessing the impact of targeting specific sex and its implications for cost-effectiveness |

| Adult vaccination scenario with the following: | ||

| • Varied vaccine efficacy | Individuals aged 15–49 years | Evaluating vaccine impact across varying levels of vaccine efficacy |

| • Varied combinations of efficacy parameters | Individuals aged 15–49 years | Evaluating vaccine impact across varying combinations of vaccine efficacy parameters (, , ) |

| • Varied duration of vaccine protection | Individuals aged 15–49 years | Evaluating vaccine impact across varying durations of vaccine protection |

| • Varied vaccine coverage | Individuals aged 15–49 years | Evaluating vaccine impact across varying vaccine coverage levels |

Vaccine coverage was gradually increased at a constant vaccination rate to reach 80% by 2040, after which it was maintained through ongoing vaccination. This scenario was designed to optimize vaccine use upon availability and maximize population-level impact within a feasible timeframe.

Individuals whose vaccine-induced immunity waned were assumed to be revaccinated at the same rate. Vaccine coverage was defined as the proportion of the targeted population currently protected by the vaccine. The model accounted for all vaccinations administered, including both initial primary series and revaccinations, and all results reflected the total number of vaccinations delivered.

To explore the impact of more focused strategies, this scenario was further adapted to prioritize specific subgroups based on age, sex, and sexual risk behavior. To assess how vaccine characteristics could optimize impact, additional analyses varied vaccine efficacy, combinations of efficacy parameters (VES, VEI, VEP), duration of protection, and coverage levels.

The second scenario represented an adolescent-focused vaccination program, introducing the vaccine in 2030 exclusively to individuals aged 10–14 years. Coverage in this cohort was gradually scaled to 80% by 2040 and maintained thereafter. This scenario reflects a potential long-term implementation approach for an STI vaccine, modeled after human papillomavirus vaccination programs [68], which target adolescents prior to sexual debut to ensure protection before initial exposure to infection.

Uncertainty analysis

To assess the impact of parameter uncertainty on model outcomes, a multivariable uncertainty analysis was performed using Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) [69, 70], with results summarized as 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs). LHS is a stratified sampling method that efficiently captures variability across the full parameter space while requiring fewer simulations than simple random sampling [69, 70]. Consistent with existing practices in modeling and cost-effectiveness analyses [55, 59, 63], each model parameter was varied within a ± 30% range around its point estimate.

Parameters varied included the duration of infection, duration of natural immunity, treatment rates for symptomatic and asymptomatic infections, proportion of infections that become symptomatic, proportion achieving immunity following treatment, degrees of assortativeness for age and risk group mixing, transmission probability per coital act, frequency of coital acts, gamma distribution parameters for sexual risk groups, the exponent in the power-law function for risk behavior, and the function defining the age-dependency of the sexual contact rate.

Each parameter range was stratified into 500 equally probable intervals, from which one value was sampled at random without replacement. These values were then randomly combined across parameters to produce 500 unique and representative parameter sets.

For each set, the model was recalibrated to match WHO region-specific, sex-stratified CT prevalence estimates, ensuring epidemiological consistency. Vaccine impact was re-estimated for each run, and 95% UIs were derived to capture uncertainty in projections driven by joint variation in behavioral and biological parameters. Accordingly, this uncertainty analysis offers a validation approach for this type of modeling framework, particularly in the absence of time-series prevalence data.

The code used to generate the analyses presented in this study is available at the cited repository link [71].

Results

Impact of adult vaccination scenario

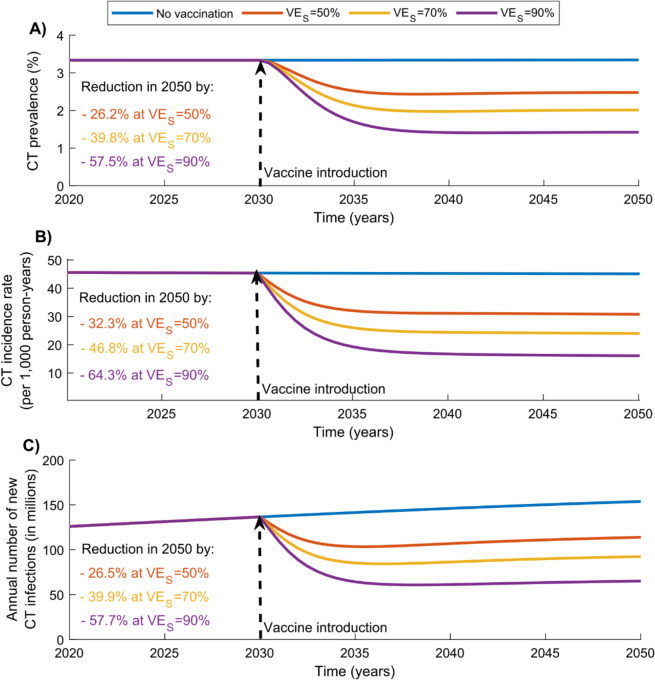

Figure 1 presents the impact of the adult vaccination scenario, in which individuals aged 15–49 years were vaccinated starting in 2030 with a vaccine providing 20 years of protection, and coverage was scaled up to 80% by 2040.

Fig. 1.

Global impact of the adult CT vaccination scenario targeting individuals aged 15–49 years. Projected reductions in (A) CT prevalence, (B) CT incidence rate, and (C) annual number of new CT infections under the adult vaccination scenario, assuming values of 50%, 70%, and 90%, with a vaccine duration of protection of 20 years. The vaccine is introduced in 2030, and coverage is scaled up to 80% by 2040 and maintained thereafter. Abbreviations: CT, Chlamydia trachomatis

At , CT prevalence, incidence rate, and the annual number of new infections in 2050 were reduced by 26.2%, 32.3%, and 26.5%, respectively. Cumulatively, 323,913,921 infections were averted by 2040 and 717,205,721 by 2050. Additional file 1: Fig. S2 presents the regional breakdown of vaccine impact, showing reductions in CT prevalence, incidence rate, and annual new infections across each WHO region in 2050.

As expected, higher vaccine efficacy resulted in greater impact. At , CT prevalence, incidence rate, and the annual number of new infections in 2050 were reduced by 39.8%, 46.8%, and 39.9%, respectively. Cumulatively, 481,724,717 infections were averted by 2040 and 1,085,672,843 by 2050.

At , CT prevalence, incidence rate, and the annual number of new infections in 2050 were reduced by 57.5%, 64.3%, and 57.7%, respectively. Cumulatively, 665,548,395 infections were averted by 2040 and 1,533,836,122 by 2050.

Impact of adolescent vaccination scenario

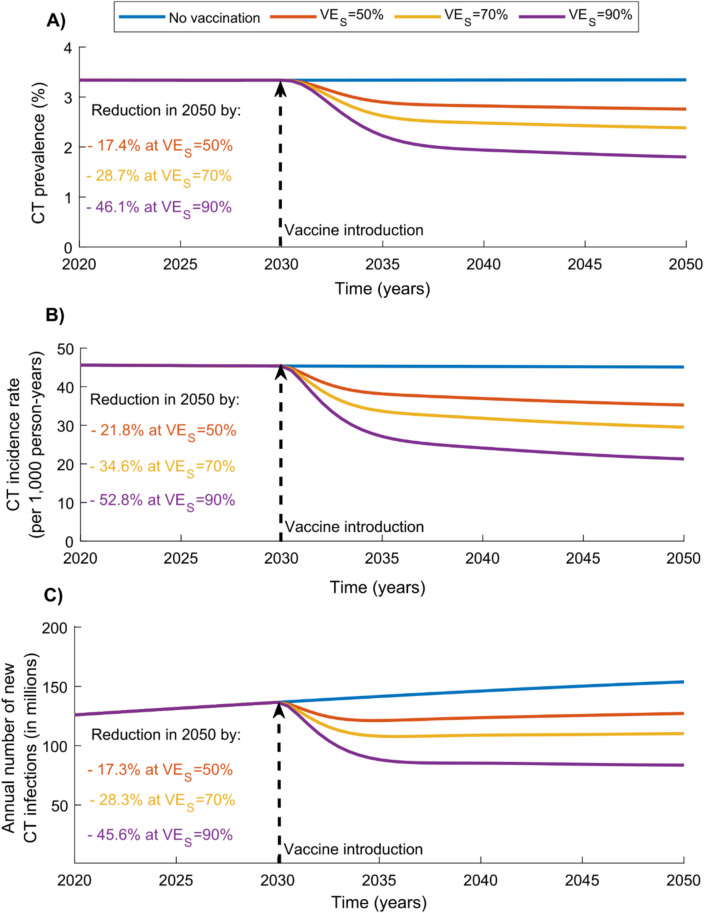

Figure 2 shows the impact of the adolescent vaccination scenario, in which adolescents aged 10–14 years were vaccinated beginning in 2030 with a vaccine providing 20 years of protection, and coverage was scaled up to 80% in this cohort by 2040.

Fig. 2.

Global impact of the adolescent CT vaccination scenario targeting individuals aged 10–14 years. Projected reductions in (A) CT prevalence, (B) CT incidence rate, and (C) annual number of new CT infections under the adolescent vaccination scenario, assuming values of 50%, 70%, and 90%, with a vaccine duration of protection of 20 years. The vaccine is introduced in 2030, and coverage is scaled up to 80% by 2040 and maintained thereafter. Abbreviations: CT, Chlamydia trachomatis

While the vaccine impact was substantial, it was lower than that observed in the adult scenario targeting individuals aged 15–49 years (Fig. 1). At , CT prevalence, incidence rate, and the annual number of new infections in 2050 were reduced by 28.7%, 34.6%, and 28.3%, respectively. Cumulatively, 279,606,388 infections were averted by 2040 and 686,072,283 by 2050.

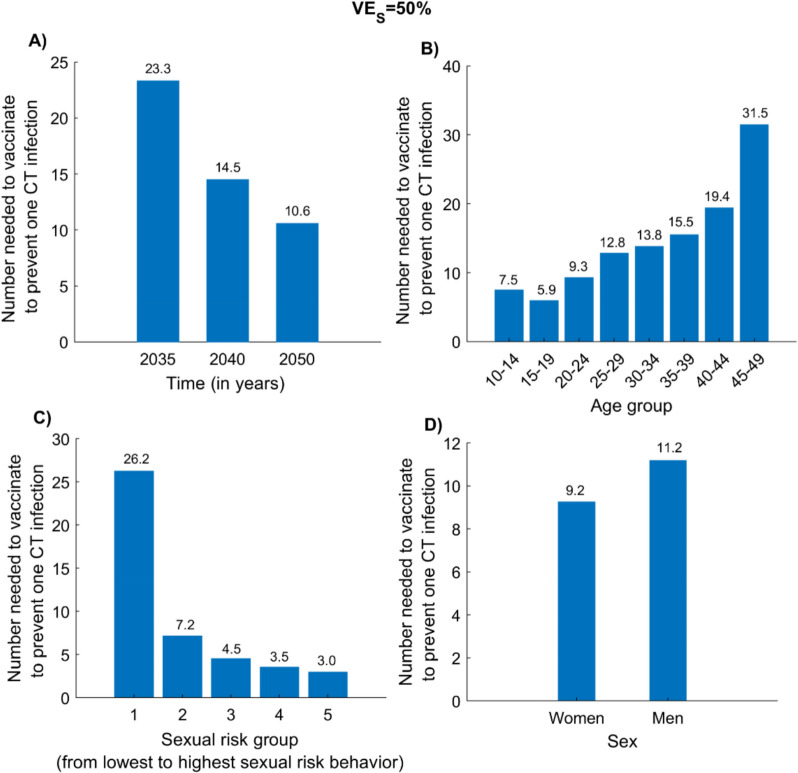

Number needed to vaccinate to prevent one CT infection

Figure 3 presents the NNV to prevent one CT infection under the adult vaccination scenario at . The NNV declined over time, from 23.3 by 2035 to 14.5 by 2040 and 10.6 by 2050 (Fig. 3A). Corresponding regional estimates for 2050 are shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S3.

Fig. 3.

Number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one CT infection under different vaccination prioritization strategies. A NNV over time since program initiation under the adult CT vaccination scenario. B NNV by age group prioritization by 2050. C NNV by sexual risk group prioritization by 2050. D NNV by sex prioritization by 2050. Analyses assume and a vaccine duration of protection of 20 years. The vaccine is introduced in 2030, with coverage scaled up to 80% by 2040 and maintained thereafter. Abbreviations: CT, Chlamydia trachomatis

The NNV varied by target population. Among age groups, individuals aged 15–19 years required the fewest vaccinations to avert one infection, with an NNV of 5.9 by 2050 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the 45–49-year group had the highest NNV at 31.5, while the 10–14-year group had the second lowest value at 7.5.

Vaccination was most efficient when targeting high-risk groups—representing populations experiencing the greatest force of infection, such as female sex workers—with an NNV of 3.0 (Fig. 3C). By comparison, the lowest-risk general population required 26.2 vaccinations to prevent one infection. Differences by sex were minimal, with NNVs of 9.2 and 11.2 for women and men, respectively (Fig. 3D).

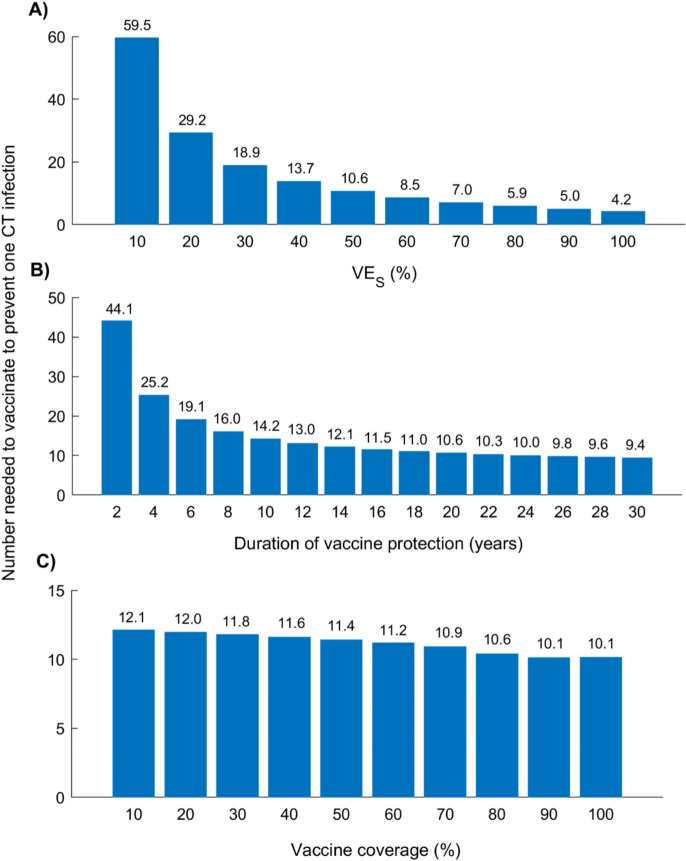

Number needed to vaccinate by vaccine efficacy, duration of protection, and coverage

Figure 4 presents the NNV to prevent one CT infection under the adult vaccination scenario, across varying , durations of protection, and coverage levels. As expected, vaccine efficiency improved with increasing and duration of protection.

Fig. 4.

Number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one CT infection under the adult vaccination scenario, across varying vaccine characteristics. Projected NNV by 2050 under different assumptions for vaccine efficacy, duration of protection, and coverage levels: A NNV versus , assuming a duration of protection of 20 years and 80% vaccine coverage. B NNV versus duration of protection, assuming and 80% coverage. C NNV versus vaccine coverage level, assuming and a 20-year duration of protection. The vaccine is introduced in 2030, targeting individuals aged 15–49 years, with coverage scaled to the target level by 2040 and maintained thereafter. Abbreviations: CT, Chlamydia trachomatis

At , the NNV was 59.5; this declined to 10.6 at and to 4.2 at (Fig. 4A). The NNV decreased rapidly with increasing at lower levels but largely plateaued beyond .

A similar pattern was observed with vaccine duration of protection (Fig. 4B). The NNV dropped from 44.1 at 2 years to 14.2 at 10 years, and further to 9.4 at 30 years, with diminishing gains beyond 10 years.

In contrast, the NNV declined only modestly with increasing vaccine coverage (Fig. 4C). At 10% coverage, the NNV was 12.1, compared to 10.1 at 100% coverage.

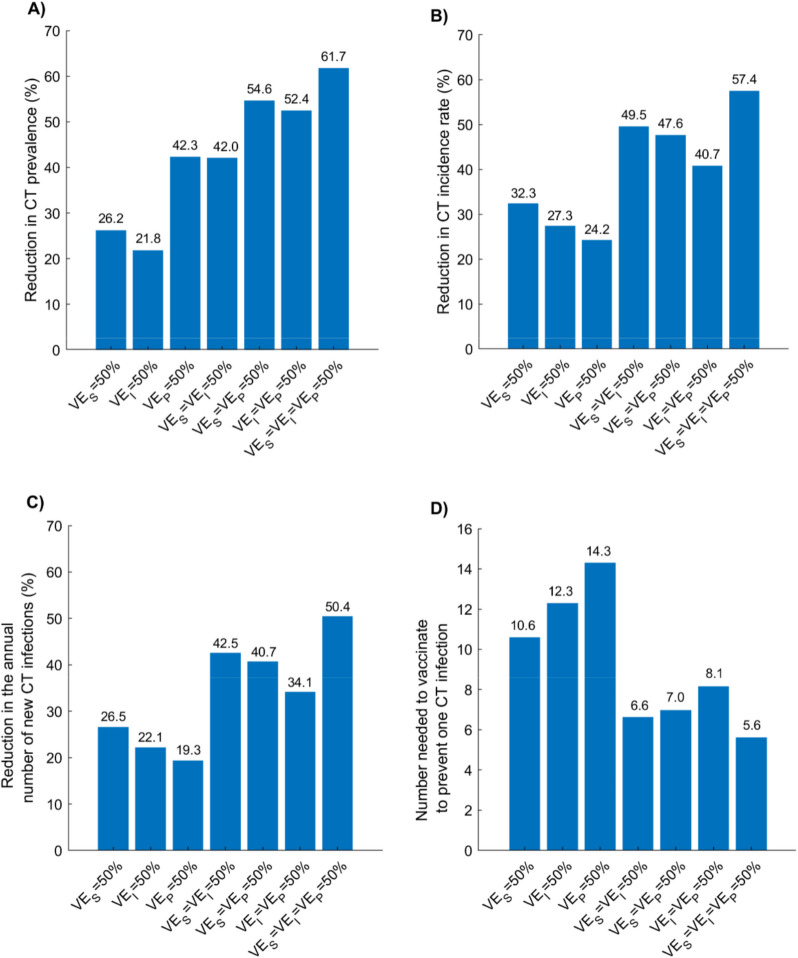

Impact of, , , and individually and in combination

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of the vaccine under the adult vaccination scenario, assuming different combinations of efficacy parameters (, , ). Among the three, produced the greatest impact—yielding the largest reductions in prevalence, incidence rate, and annual number of new infections, as well as the lowest NNV.

Fig. 5.

Global impact of the adult CT vaccination scenario under different combinations of vaccine efficacy parameters. Projected reductions in (A) CT prevalence, (B) CT incidence rate, (C) annual number of new CT infections in 2050, and (D) the number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one CT infection by 2050, assuming different combinations of , , and , each set at 50%. The vaccine provides 20 years of protection and is introduced in 2030, and coverage is scaled up to 80% by 2040 and maintained thereafter. Abbreviations: CT, Chlamydia trachomatis

However, combining with the breakthrough effects of and/or consistently yielded greater impact than any single efficacy component alone, with the most substantial reductions observed when all three were combined. At = , CT prevalence, incidence rate, and the annual number of new infections in 2050 were reduced by 61.7%, 57.4%, and 50.4%, respectively, with a corresponding NNV of 5.6.

Uncertainty analysis

Additional file 1: Fig. S4 presents the results of the uncertainty analysis, demonstrating the influence of variability in model parameters on vaccine impact estimates. Despite parameter uncertainty, the vaccine consistently produced substantial reductions in CT infection outcomes across all simulations, indicating that the conclusion of a beneficial vaccine impact remained robust.

Discussion

Vaccination against CT has the potential to substantially reduce the global incidence and prevalence of infection, even if the vaccine offers only moderate efficacy and does not provide sterilizing immunity. The benefits of vaccination become evident within a few years of implementation and continue to accumulate over time. With a relatively low number needed to vaccinate to prevent a single infection—just 10.6 by 2050—the vaccine may prove to be cost-effective, or even cost-saving, as supported by a health economic analysis [72].

These findings highlight the need to prioritize CT vaccine development and to incorporate the vaccine, once available, into public health strategies aimed at reducing the health and economic burdens associated with the infection. The analysis also identifies opportunities to enhance cost-effectiveness through targeted vaccination. Among age groups, vaccinating individuals aged 15–19 years was the most efficient strategy, requiring only 5.9 vaccinations to avert one infection by 2050. Adolescents aged 10–14 years also represented an efficient target group, with an NNV of 7.5. The highest efficiency was observed in high-risk populations—such as female sex workers—where just 3.0 vaccinations were needed to prevent one infection.

Although vaccinating women was slightly more efficient than vaccinating men, the difference was modest. Nonetheless, given the disproportionately higher burden of CT-related reproductive health complications among women [3, 4, 6, 7], these findings underscore the importance of prioritizing women in vaccination strategies.

It is important to note that the vaccine impact estimates presented in this study may be conservative. The primary analyses assume that the vaccine functions solely by reducing susceptibility to infection (), without accounting for potential biological effects among vaccinated individuals who experience breakthrough infections. Evidence from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection suggests that vaccination can reduce pathogen load () and shorten the duration of infection () in such cases [66, 73, 74]. Similar effects are plausible for CT infection, as supported by animal model studies demonstrating vaccine-induced reductions in bacterial load and infection duration [26, 47, 65]. Additional analyses in this study indicate that accounting for these breakthrough effects could markedly enhance the overall impact of the vaccine. Accordingly, clinical trials for CT vaccines should assess not only efficacy against acquisition but also effects on bacterial load and infection duration.

Although adolescent vaccination is likely to serve as the long-term strategy—providing protection prior to initial exposure—the public health impact of this approach will require a decade to materialize, as vaccinated individuals gradually age into periods of sexual activity. In contrast, the adult vaccination scenario illustrates that implementing a catch-up strategy targeting individuals aged 15–49 years, or at least those aged 15–29 years, can markedly accelerate population-level impact in the years immediately following vaccine introduction. Such an approach is critical for achieving timely and substantial reductions in CT burden.

This study has limitations. The study was based on assumed vaccine characteristics; however, no CT vaccine is currently available, and the attributes of any future vaccine may differ substantially from those explored in this analysis. The eventual vaccine may exhibit different efficacy profiles, durations of protection, or modes of action than those modeled here, which could influence its population-level impact. Nonetheless, the scenarios examined in this study were designed to reflect a broad and plausible range of vaccine characteristics to provide generalizable insights into the potential benefits of CT vaccination under various conditions.

The model was calibrated to WHO sex-specific CT prevalence estimates for each region, which vary considerably and are associated with substantial uncertainty [8, 9]. Given the relatively low prevalence of CT, its transmission dynamics are sensitive to the underlying structure of sexual risk behavior—particularly the distribution of individuals across risk groups and the intensity of risk behavior within those groups. Consequently, regional differences in prevalence necessitated distinct parameterizations of sexual risk behavior, resulting in variability in the projected vaccine impact across regions. In light of the uncertainty surrounding regional prevalence estimates [8, 9], these regional differences in vaccine impact should be interpreted with caution.

Model estimates rely on input data whose validity and generalizability remain uncertain, as key aspects of CT natural history and transmissibility are still not well characterized [10, 18, 36, 75, 76]. This knowledge gap arises largely from ethical constraints in studying a treatable infection. Furthermore, the lack of regional time-series and age-specific prevalence data precludes their incorporation into model calibration, necessitating the assumption of stable prevalence in the absence of vaccination. This also prevents use of other validation methods based on training and testing data sets, such as comparing model predictions to out-of-sample observations.

However, because the model focuses on estimating relative reductions in outcomes, its predictions are less sensitive to such uncertainties. Any bias in prevalence calibration would likely affect both the vaccination and no-vaccination scenarios similarly, with reduced impact on the estimated relative vaccine effect. This is further supported by the uncertainty analysis, which showed that substantial vaccine impact was consistently sustained across a wide range of parameter assumptions.

The model did not explicitly incorporate CT testing and treatment programs; however, their effects were implicitly captured through calibration to observed prevalence, which reflects real-world transmission dynamics in the presence of such programs. CT infection was assumed to be at endemic equilibrium in the absence of vaccination. However, shifts in sexual behavior patterns or the introduction of interventions could have modified transmission dynamics over time. The definition of “sexual risk groups” remains imprecise and context dependent [42, 77–79], which limits the precision of NNV estimates within these subpopulations. Moreover, the model did not account for potential sexual behavior changes following vaccination due to the lack of consistent empirical evidence supporting such effects [68].

Vaccination was assumed to be administered irrespective of individuals’ current or prior CT infection status, reflecting programmatic feasibility. The model assumed no vaccine-induced benefit among previously infected individuals, consistent with existing evidence from human and animal studies on CT immunity [19–21]. Should future data demonstrate protective effects in this group, the estimates presented here would underestimate the true impact of vaccination. The model assumed that vaccine-induced protection wanes according to an exponential distribution; however, the rate and pattern of waning for CT vaccine-induced immunity remain unknown. This assumption may also overestimate the number of vaccinations required to avert one infection, as it causes some individuals to lose immunity more quickly than the average duration—leading to earlier revaccination—while others retain protection for longer than expected.

Finally, this study focused on epidemiological impact and did not include a health economic evaluation. Cost components such as screening, clinical care, treatment of complications (e.g., PID, ectopic pregnancy, infertility), and assisted reproductive services were not considered. Future research should incorporate these elements into a full economic evaluation, particularly once vaccine cost data become available, to provide a more comprehensive assessment of CT vaccination programs.

This study has strengths. The model was sufficiently detailed to capture the complexity of CT transmission dynamics, incorporating stratification by age, sex, and sexual risk behavior while remaining tailored to available epidemiological and behavioral data. The model incorporated a range of vaccine characteristics—such as efficacy components, durations of protection, and coverage levels—allowing for comprehensive scenario analyses. Despite uncertainty in key aspects of CT natural history, the model produced projections that were robust across a range of plausible assumptions, as demonstrated by the uncertainty analysis. Importantly, the projected vaccine impact is likely conservative. For example, the model assumed a relatively long duration of natural immunity; if this duration is shorter in reality, the vaccine’s impact would be greater due to increased reinfection risk among unvaccinated individuals. Furthermore, the main analyses did not account for potential secondary benefits, such as reductions in infectiousness, infection duration, or complications from breakthrough infections—factors that would further enhance vaccine efficiency and impact, as shown in the additional analyses. These conservative assumptions strengthen confidence in the reliability and public health relevance of the projected benefits of CT vaccination.

Conclusions

Vaccination against CT is a promising public health intervention with the potential to substantially reduce the global burden of infection, even if it provides only moderate efficacy and does not confer sterilizing immunity. The benefits of vaccination emerge rapidly and accumulate over time, with potential for cost-effectiveness—particularly when targeted to high-impact groups such as adolescents, young adults, and individuals at elevated sexual risk. While adolescent vaccination offers a sustainable long-term strategy, catch-up vaccination among young adults will be critical for achieving immediate reductions in incidence. The projections presented here are likely conservative, and real-world vaccine impact could be greater if breakthrough effects on infectiousness and infection duration are realized. These findings support urgent investment in CT vaccine development and highlight the importance of integrating the vaccine into public health programs to mitigate both the clinical and economic burden of this common infection.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the administrators of the Red Cloud infrastructure at Cornell University for their support in running the simulations. They are also grateful to Ms. Adona Canlas for administrative assistance.

ChatGPT was used solely for grammar verification and phrasing refinement. The authors thoroughly reviewed and edited the text, taking full responsibility for its accuracy and quality.

Abbreviations

- CT

Chlamydia trachomatis

- LHS

Latin Hypercube Sampling

- NNV

Number needed to vaccinate

- PID

Pelvic inflammatory disease

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- STI

Sexually transmitted infection

- UI

Uncertainty interval

- U.S.

United States

- VEI

Vaccine efficacy against infection infectiousness

- VEP

Vaccine efficacy against infection disease progression

- VES

Vaccine efficacy against infection acquisition

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

MM designed, parameterized, and coded the mathematical model, conducted the simulations, and co-wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LJA conceived the study and led the design of the model and analyses, and co-wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council (ARG01-0522–230273). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council. The authors also acknowledge the infrastructure support provided by the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its supplementary material. The model’s source code is available at: https://github.com/MouniaM/CT-vaccination.git.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Monia Makhoul, Email: mom2039@qatar-med.cornell.edu.

Laith J. Abu-Raddad, Email: lja2002@qatar-med.cornell.edu

References

- 1.Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, Low N, Unemo M, Abu-Raddad LJ, Chico RM, Smolak A, Newman L, Gottlieb S, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(8):548-562P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Bergen J, Hoenderboom BM, David S, Deug F, Heijne JCM, van Aar F, Hoebe C, Bos H, Dukers-Muijrers N, Gotz HM, et al. Where to go to in chlamydia control? From infection control towards infectious disease control. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97(7):501–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rekart ML, Gilbert M, Meza R, Kim PH, Chang M, Money DM, Brunham RC. Chlamydia public health programs and the epidemiology of pelvic inflammatory disease and ectopic pregnancy. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(1):30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishori R, McClaskey EL, WinklerPrins VJ. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: screening, diagnosis, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(12):1127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McConaghy JR, Panchal B. Epididymitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(9):723–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J. Pelvic inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2039–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reekie J, Donovan B, Guy R, Hocking JS, Kaldor JM, Mak DB, Pearson S, Preen D, Stewart L, Ward J, et al. Risk of pelvic inflammatory disease in relation to chlamydia and gonorrhea testing, repeat testing, and positivity: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization: Progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections 2021. World Health Org 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077. Accessed on Feb 2, 2025.

- 9.World Health Organization: Global and regional sexually transmitted infection estimates for 2020. Available from World Health Org 2023. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/global-and-regional-sti-estimates. Accessed on Feb 2, 2025.

- 10.Brunham RC, Rappuoli R. Chlamydia trachomatis control requires a vaccine. Vaccine. 2013;31(15):1892–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronn MM, Li Y, Gift TL, Chesson HW, Menzies NA, Hsu K, Salomon JA. Costs, health benefits, and cost-effectiveness of chlamydia screening and partner notification in the United States, 2000–2019: a mathematical modeling analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2023;50(6):351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronn MM, Wolf EE, Chesson H, Menzies NA, Galer K, Gorwitz R, Gift T, Hsu K, Salomon JA. The use of mathematical models of chlamydia transmission to address public health policy questions: a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(5):278–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Wees DA, Drissen M, den Daas C, Heijman T, Kretzschmar MEE, Heijne JCM. The impact of STI test results and face-to-face consultations on subsequent behavior and psychological characteristics. Prev Med. 2020;139: 106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies B, Turner KME, Frolund M, Ward H, May MT, Rasmussen S, Benfield T, Westh H. Danish Chlamydia Study G: Risk of reproductive complications following chlamydia testing: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Denmark. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(9):1057–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunham RC, Rekart ML. The arrested immunity hypothesis and the epidemiology of chlamydia control. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(1):53–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su H, Morrison R, Messer R, Whitmire W, Hughes S, Caldwell HD. The effect of doxycycline treatment on the development of protective immunity in a murine model of chlamydial genital infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(4):1252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunham RC, Pourbohloul B, Mak S, White R, Rekart ML. The unexpected impact of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection control program on susceptibility to reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(10):1836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omori R, Chemaitelly H, Althaus CL, Abu-Raddad LJ. Does infection with Chlamydia trachomatis induce long-lasting partial immunity? Insights from mathematical modelling. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(2):115–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batteiger BE, Xu F, Johnson RE, Rekart ML. Protective immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection: evidence from human studies. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl 2):S178-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottlieb SL, Martin DH, Xu F, Byrne GI, Brunham RC. Summary: the natural history and immunobiology of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection and implications for chlamydia control. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl 2):S190-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rank RG, Whittum-Hudson JA. Protective immunity to chlamydial genital infection: evidence from animal studies. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl 2):S168-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisler WM, Lensing SY, Press CG, Hook EW 3rd. Spontaneous resolution of genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women and protection from reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(12):1850–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Althaus CL, Turner KM, Schmid BV, Heijne JC, Kretzschmar M, Low N. Transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis through sexual partnerships: a comparison between three individual-based models and empirical data. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(66):136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smid J, Althaus CL, Low N. Discrepancies between observed data and predictions from mathematical modelling of the impact of screening interventions on Chlamydia trachomatis prevalence. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottlieb SL, Deal CD, Giersing B, Rees H, Bolan G, Johnston C, Timms P, Gray-Owen SD, Jerse AE, Cameron CE, et al. The global roadmap for advancing development of vaccines against sexually transmitted infections: update and next steps. Vaccine. 2016;34(26):2939–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de la Maza LM, Darville TL, Pal S. Chlamydia trachomatis vaccines for genital infections: where are we and how far is there to go? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(4):421–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray SM, McKay PF. Chlamydia trachomatis: cell biology, immunology and vaccination. Vaccine. 2021;39(22):2965–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gottlieb SL, Spielman E, Abu-Raddad L, Aderoba AK, Bachmann LH, Blondeel K, Chen XS, Crucitti T, Camacho GG, Godbole S, et al. WHO global research priorities for sexually transmitted infections. Lancet Glob Health. 2024;12(9):e1544–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottlieb SL, Giersing BK, Hickling J, Jones R, Deal C, Kaslow DC. Group HSVVEC: Meeting report: initial World Health Organization consultation on herpes simplex virus (HSV) vaccine preferred product characteristics, March 2017. Vaccine. 2019;37(50):7408–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boily M-C, Brisson M, Mâsse B, Anderson R: The role of mathematical models in vaccine development and public health decision making. In., edn. Edited by Morrow W, Sheikh N, Schmidt C, Davies D: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012;480–508.

- 31.Boily MC, Abu-Raddad L, Desai K, Masse B, Self S, Anderson R. Measuring the public-health impact of candidate HIV vaccines as part of the licensing process. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(3):200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alsallaq RA, Schiffer JT, Longini IM Jr, Wald A, Corey L, Abu-Raddad LJ. Population level impact of an imperfect prophylactic vaccine for herpes simplex virus-2. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(5):290–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makhoul M, Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Seedat S, Mumtaz GR, Al-Omari S, Abu-Raddad LJ: Epidemiological impact of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: mathematical modeling analyses. Vaccines (Basel) 2020:8(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Dasbach EJ, Elbasha EH, Insinga RP. Mathematical models for predicting the epidemiologic and economic impact of vaccination against human papillomavirus infection and disease. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:88–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makhoul M, Ayoub HH, Awad SF, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. Impact of a potential chlamydia vaccine in the USA: mathematical modelling analyses. BMJ Public Health. 2024;2(1): e000345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson LF, Geffen N. A comparison of two mathematical modeling frameworks for evaluating sexually transmitted infection epidemiology. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(3):139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Althaus CL, Heijne JC, Roellin A, Low N. Transmission dynamics of Chlamydia trachomatis affect the impact of screening programmes. Epidemics. 2010;2(3):123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Althaus CL, Heijne JC, Herzog SA, Roellin A, Low N. Individual and population level effects of partner notification for Chlamydia trachomatis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12): e51438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heijne JC, Althaus CL, Herzog SA, Kretzschmar M, Low N. The role of reinfection and partner notification in the efficacy of chlamydia screening programs. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(3):372–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heijne JC, Herzog SA, Althaus CL, Tao G, Kent CK, Low N. Insights into the timing of repeated testing after treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis: data and modelling study. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(1):57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kretzschmar M, Turner KM, Barton PM, Edmunds WJ, Low N. Predicting the population impact of chlamydia screening programmes: comparative mathematical modelling study. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(5):359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner KM, Adams EJ, Gay N, Ghani AC, Mercer C, Edmunds WJ. Developing a realistic sexual network model of chlamydia transmission in Britain. Theor Biol Med Model. 2006;3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garnett GP, Anderson RM. Factors controlling the spread of HIV in heterosexual communities in developing countries: patterns of mixing between different age and sexual activity classes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1993;342(1300):137–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garnett GP, Anderson RM. Balancing sexual partnership in an age and activity stratified model of HIV transmission in heterosexual populations. Mathematical Medicine and Biology: A J of the IMA. 1994;11(3):161–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abu-Raddad LJ, Boily MC, Self S, Longini IM Jr. Analytic insights into the population level impact of imperfect prophylactic HIV vaccines. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(4):454–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ: Epidemiological impact of novel preventive and therapeutic HSV-2 vaccination in the United States: mathematical modeling analyses. Vaccines (Basel) 2020:8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Gray RT, Beagley KW, Timms P, Wilson DP. Modeling the impact of potential vaccines on epidemics of sexually transmitted Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(11):1680–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de la Maza MA, de la Maza LM. A new computer model for estimating the impact of vaccination protocols and its application to the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. Vaccine. 1995;13(1):119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omori R, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. Dynamics of non-cohabiting sex partnering in sub-Saharan Africa: a modelling study with implications for HIV transmission. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91(6):451–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liljeros F, Edling CR, Amaral LA, Stanley HE, Aberg Y. The web of human sexual contacts. Nat. 2001;411(6840):907–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barabási A-L. Linked: How Everything Is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life. New York: Plume; 2003.

- 52.Boccaletti S, Latora V, Moreno Y, Chavez M, Hwang D. Complex Networks: Structure and Dynamics Physics Reports. 2006;424:175–308.

- 53.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH: Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’networks. nat.1998:393(6684):440. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Barrat A, Barthelemy M, Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A. The architecture of complex weighted networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(11):3747–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ayoub HH, Amara I, Awad SF, Omori R, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ: Analytic characterization of the herpes simplex virus type 2 epidemic in the United States, 1950–2050. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021;8(7):ofab218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Garnett GP, Anderson RM. Contact tracing and the estimation of sexual mixing patterns: the epidemiology of gonococcal infections. Sex Transm Dis. 1993;20(4):181–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12): e0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: World Population Prospects, the 2018 Revision. 2018. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/.

- 59.Awad SF, Sgaier SK, Tambatamba BC, Mohamoud YA, Lau FK, Reed JB, Njeuhmeli E, Abu-Raddad LJ. Investigating voluntary medical male circumcision program efficiency gains through subpopulation prioritization: insights from application to Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12): e0145729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Awad SF, Abu-Raddad LJ. Could there have been substantial declines in sexual risk behavior across sub-Saharan Africa in the mid-1990s? Epidemics. 2014;8:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Awad SF, Sgaier SK, Lau FK, Mohamoud YA, Tambatamba BC, Kripke KE, Thomas AG, Bock N, Reed JB, Njeuhmeli E, et al. Could circumcision of HIV-positive males benefit voluntary medical male circumcision programs in Africa? Mathematical modeling analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1): e0170641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinstein M, Wood JW, Stoto MA, Greenfield DD. Components of Age-Specific Fecundability. Popul Stud. 1990;44(3):447–67. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. Characterizing the transitioning epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the USA: model-based predictions. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lagarias JC, Reeds JA, Wright MH, Wright PE. Convergence properties of the Nelder-Mead simplex method in low dimensions. SIAM J Optim. 1998;9(1):112–47. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Igietseme J, Eko F, He Q, Bandea C, Lubitz W, Garcia-Sastre A, Black C. Delivery of chlamydia vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2005;2(3):549–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Tang P, Coyle P, Hasan MR, Yassine HM, Benslimane FM, Al-Khatib HA, Al-Kanaani Z, et al. Relative infectiousness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine breakthrough infections, reinfections, and primary infections. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm. 1976–2016

- 68.Kasting ML, Shapiro GK, Rosberger Z, Kahn JA, Zimet GD. Tempest in a teapot: a systematic review of HPV vaccination and risk compensation research. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1435–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huntington DE, Lyrintzis CS. Improvements to and limitations of Latin hypercube sampling. Probab Eng Mech. 1998;13(4):245–53. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blower SM, Dowlatabadi H: Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex models of disease transmission: an HIV model, as an example. Internal Stats Rev/Revue Intl de Statis 1994:229–243.

- 71.Makhoul M, Abu-Raddad LJ: Vaccination as a strategy for Chlamydia trachomatis control: a global mathematical modeling analysis. Github. 2025. https://github.com/MouniaM/CT-vaccination.git. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Chesson HW, Gift TL, Brunham RC, Bolan G. Cost-effectiveness of chlamydia vaccination programs for young women. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(6):960–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qassim SH, Hasan MR, Tang P, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Yassine HM, Al-Khatib HA, Smatti MK, Abdul-Rahim HF, Nasrallah GK, et al. Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants, age, vaccination, and prior infection on infectiousness of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 984784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hay JA, Kissler SM, Fauver JR, Mack C, Tai CG, Samant RM, Connolly S, Anderson DJ, Khullar G, MacKay M et al. Quantifying the impact of immune history and variant on SARS-CoV-2 viral kinetics and infection rebound: a retrospective cohort study. Elife 2022;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Brunham RC. Problems with understanding Chlamydia trachomatis immunology. J Infect Dis. 2022;225(11):2043–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lewis J, White PJ, Price MJ. Per-partnership transmission probabilities for Chlamydia trachomatis infection: evidence synthesis of population-based survey data. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(2):510–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Omori R, Abu-Raddad LJ. Sexual network drivers of HIV and herpes simplex virus type 2 transmission. AIDS. 2017;31(12):1721–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Omori R, Nagelkerke N, Abu-Raddad LJ. Nonpaternity and half-siblingships as objective measures of extramarital sex: mathematical modeling and simulations. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:3564861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Omori R, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. Understanding dynamics and overlapping epidemiologies of HIV, HSV-2, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis in sexual networks of men who have sex with men. Front Pub Health. 2024;12:1335693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its supplementary material. The model’s source code is available at: https://github.com/MouniaM/CT-vaccination.git.