Abstract

Background

Long-acting injectable (LAI) hormonal contraception offers a promising approach to meet women’s pregnancy prevention needs. We sought to understand acceptability of and preferences for LAI hormonal contraception among US women, to optimize the design of a sustained-release LAI in development – including which durations to pursue.

Methods

We implemented a national cross-sectional online survey including a discrete choice experiment (DCE) with women ages 18–44 years currently using or interested in using contraception. Recruitment was via Prime Panels. DCE attributes included potential duration of effectiveness (6/12/24-months), effect on menses, side effects, and timing of return-to-fertility after use. We used mixed-multinomial logit models to analyze the data.

Results

Women (n = 1,029) were 28.6 years old on-average, from 49 US states. 30.9% were Black/African American; 11.6% Hispanic/Latina. 71.6% were nulliparous; 49.0% did not want a(nother) child. Common current contraceptive methods were birth control pills (37.4%), male condoms (35.7%), and withdrawal (19.8%); 18.9% reported having had an unintended pregnancy. In the DCE, women had strong negative preferences for: may cause heavier/unpredictable periods, mild headaches/nausea, slight weight gain, and delayed return-to-fertility (6–12 vs. 3 months), and positive preferences for: may cause no period, and shorter/lighter periods (all p < 0.001). Women also preferred the 12-month to the 6-month duration (p = 0.03). When asked directly about their interest in an LAI with no/minimal side effects/effects on menses and quick return-to-fertility, 92.4% expressed interest, with two-thirds preferring a longer duration (12 or 24-months), and one-third the 6-month duration. Preference for the 6-month duration (vs. 12 or 24) was most highly associated with wanting a child within five years, and higher discomfort with hormones (both p < 0.001).

Conclusions

US women report high interest in an LAI. Interest substantially decreases if the LAI may cause unwanted effects such as heavier/unpredictable periods, mild headaches/nausea, slight weight gain, or delayed return-to-fertility. While longer duration (12 + months) is preferred overall, having a 6-month option appears important especially for women who may want to get pregnant within the next few years, and those concerned about hormones (to try it before using a longer duration).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40834-025-00380-5.

Keywords: Family planning, Contraceptive, United States, Injection, Sustained release; discrete choice experiment

Introduction

Globally, more than 200 million women have an unmet need for contraception [1, 2] and in the United States (US), nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended [3]. Nearly all unintended pregnancies (95%) occur among women not using their contraceptive method correctly or consistently, or who use no method [4]. Furthermore, nearly 40% of women discontinue a method within 12 months of initiation despite wanting to prevent or delay pregnancy [5, 6]. New contraceptive technologies under development aim to fill an unmet need for contraception among individuals dissatisfied by currently available options [7, 8].

Injectable hormonal contraception, an important part of the contraceptive method mix worldwide, currently has a maximum duration of 3 months. Injectable hormonal contraception has been available since the 1960s and in the US since FDA approval in 1992 [9]. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) is the most commonly used injectable globally. Many women find injectables more convenient and discreet than taking a daily birth control pill, and some prefer this method to device-based, longer-acting reversible contraceptives (e.g., intrauterine devices or implants) [10]. Although with ideal use DMPA is over 99% effective [11], several features have limited compliance and hence effectiveness, including barriers/inconvenience associated with returning to the clinic every 3 months (particularly among rural and low-income women [12, 13]), side effects (including loss of bone mineral density), menstrual pattern changes, and long and unpredictable return of fertility of up to 10 months [14]. In fact, DMPA continuation rates at one year can be as low as 40% [15, 16]. While efforts to move towards self-injection to improve continuation rates have proliferated and shown promise [17, 18], a longer-acting injectable could provide another solution.

Daré Bioscience and Adare Pharma Solutions are developing a long-acting injectable (LAI) that addresses each of these concerns by leveraging advances in microsphere technology, Stratµm®, to encapsulate and support extended release of etonogestrel, a synthetic progestin currently used in the contraceptive implant Nexplanon®. The LAI was designed to achieve 6 months or 12 months of contraceptive effectiveness when injected subcutaneously, with potential for longer durations in the future. The uniform microsphere size is expected to allow for continuous drug dosage delivery (anticipated to reduce side effects), and rapid return of fertility (anticipated to be within three months).

In addition to the rigorous safety and efficacy requirements for regulatory approval, end-user research is critical to ensure that contraceptive methods under development meet users’ needs [19, 20]. Such research needs to begin early in product development since user preferences influence acceptability, intention to use, satisfaction, and ultimately adherence and continuation [8]. Several recent studies suggest that women are strongly interested in an LAI (when asked about as a hypothetical future product, often lasting 6 months), largely due to its convenience [10, 21, 22], while they are sometimes also more wary of longer durations in case of any adverse effects given its non-reversibility once injected [22]. As public health interest in LAI formulations grows, for contraception as well as other indications (including HIV prevention), a key question is how individuals weigh the perceived advantages of longer duration, with perceived potential for adverse effects.

In this national survey with US women, that included a discrete choice experiment (DCE), we sought to better understand overall acceptability as well as preferred duration (in light of other product attributes) and characteristics of end-users in the US most likely to use an LAI. Findings are intended to inform the design of our LAI under development, and to add to the field’s understanding of decision-making about long-acting injectable products.

Methods

We conducted an online survey in June-July 2023 with sexually active US women aged 18–44 years who reported not wanting to become pregnant in the next six months and currently using/interested in using contraception. The recruitment process was managed by CloudResearch, an online research platform. The sample was recruited via Prime Panels, an aggregation of dozens of opt-in market research platforms that are commonly used for online research, including MTurk, where people perform tasks for a nominal fee, including completing surveys [23, 24]. Each market research platform that is part of Prime Panels has its own pool of participants, who are profiled by numerous socio-demographic and sometimes other variables. When researchers launch a study, participants meeting the study’s eligibility criteria receive an invitation (e.g., to complete a given survey) via email or the platform’s dashboard (per standard practice for the platform) [25]. MTurk has been used extensively in social and behavioral science research [24], including women’s interest in sexual and reproductive health products [26, 27]. Research has also shown that Prime Panels consistently yields high-quality data, in part due to its screening process in which potential survey participants first complete a brief screener to identify and block individuals who provide poor quality responses [28–30].

A target sample size of 1,000 was selected to ensure adequate statistical power for the DCE [31], and to examine heterogeneity in preferences between women based on several different characteristics. Women were eligible if (per existing information available in Prime Panels) they were a female, aged 18–44 years, living in the US, and (as assessed by a set of screening questions) reported not wanting to become pregnant in the next six months; current contraceptive user or interested in contractive use; no tubal ligation or hysterectomy; and no medical conditions that would make her unable to use a hormonal contraceptive (for example, current breast cancer). Pre-specified quotas were set within Prime Panels (based on existing information in Prime Panels) for 50% of the sample to be young women ages 18–24 years and at least 30% to be Black/African American, to help ensure representation from these subgroups of women who have historically been more likely than their counterparts to use the three-month hormonal contraceptive injectable DMPA.

The survey was programmed and hosted in REDCap [32, 33], and was available in English or Spanish. Prime Panels automatically sent eligible respondents a link to the survey indicating that it will take 20–30 min to complete and will be available in English and Spanish. After finishing the screening questions, eligible respondents completed informed consent before proceeding to the survey. Surveys took an average of 23 min to complete. Each participant who completed the survey was compensated at a rate set by Prime Panels, which did not exceed $10.

Conceptual framework

This study was driven by a conceptual framework in which product- and user-centered factors interact to influence user acceptability, intention to use, initiation, and continuation of the product. Drawing on previous conceptual frameworks [34, 35], product-centered factors include: physical characteristics (e.g., injectable; non-reversible), duration (e.g., 6-, 12-, 24-month; plus return to fertility after duration complete), active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs; e.g., contains hormones), and side effects (e.g., effect on menses; weight gain). Specific user-centered factors to investigate in this study were informed by the Theory of Planned Behavior [36, 37] in which three determinants influence behavioral intentions: (1) attitude (e.g., about contraception, hormones, and the LAI attributes specifically), (2) subjective norms (e.g., perceptions about healthcare provider, peer, or partner approval of LAI use), and (3) perceived behavioral control (e.g., over LAI use, including lack of control over reversing drug effects once injected). Participant background factors (e.g., sociodemographic characteristics, reproductive and contraceptive history) are hypothesized to influence these determinants.

DCE design

In DCEs, participants complete a series of “choice sets,” each involving a single choice between Option A (consisting of the combination of specific levels for a series of attributes) or Option B (consisting of other levels of those same attributes). We fixed certain product attributes like hormonal nature, > 99% effectiveness, and non-reversibility at a single level since they are inherent to injectable hormonal contraception and are not modifiable.

We designed the DCE as recommended [38]: (1) Identified potentially salient characteristics (such as duration, effect on menstrual cycle, return to fertility, etc.); (2) Refined these characteristics and identified their levels (such as different durations; nature of effect on menstrual cycle); (3) Selected a subset of the possible choice sets; and (4) Finalized choice sets, including specific wording and layout. For the first step, DCE attribute choices were selected based on consideration of this particular LAI’s characteristics (e.g., potential durations in development; etonogestrel and its known contraceptive efficacy and most common effects on menses and other side effects; targeting a rapid, predictable return to fertility after duration is complete), as well as a literature review to identify potentially salient characteristics of LAIs in general to end-users. Attribute selection was also informed by previous responses to a question about potential interest in different durations of the LAI under development from qualitative in-depth interviews with 25 US women ages 20–47 years recruited via ResearchMatch [39]. These data further informed the DCE design (especially to home in on key attributes women seemed to weigh against each other when considering the product), as well as other survey variables (characteristics of women that seemed to influence their considerations of the product). We finalized the set of attributes and defined appropriate levels for each in consultation with study team members and other experts (who include product developers, as well as an obstetrician/gynecologist).

We used NGene software [40] to select a subset from all possible choice sets using a fractional factorial design. We limited the number of choice sets to 12 to reduce cognitive burden that can lead to respondent fatigue [41]. We pilot-tested the survey, including the DCE choice sets, with 21 respondents via Prime Panels, and generated final choice sets in NGene based on priors from the pilot data [31].

Final DCE attributes (and levels) included: Duration (6, 12, 24 months); Effect on menstruation (No effect; May cause shorter or lighter periods, with possibly unpredictable bleeding; May cause heavier bleeding, with possible unpredictable bleeding; May cause you to have no period); Other side effects (None; May cause mild headaches or nausea; May cause slight weight gain; May cause mood changes); and Return to fertility after use (Within 3 months, predictable; Within 6–12 months, unpredictable). Figure 1 presents an illustrative choice set from the final survey.

Fig. 1.

Illustrative example of a DCE choice set (1 of 12)

The DCE section was introduced by a series of statements about the product being developed (after each of which the participant had to check “Ok, got it.”), including the anticipated contraceptive effectiveness of > 99%, the type of hormone, even release of hormones over time, at no higher a dose than currently approved products, and non-reversibility before the end of the intended duration. We then presented a brief description of each DCE attribute and its levels. After that, the participants were presented with the 12 choice sets. For each, respondents were asked to choose Option A, Option B, or Neither option. If respondents chose “neither”, they were asked a follow up ‘forced choice’ question (“if you had to choose Option A or B, which would you choose?”). All participants completed the same choice sets; however, the order of choice sets was varied to avoid positional bias (respondents were randomized to one of three possible attribute orders).

Additional study measures

Immediately following the DCE choice sets, we asked directly about which duration for an LAI with the target product profile (TPP - i.e., no/minimal effects on menstruation, no/minimal side effects, and return to fertility within 3 months, predictable) they would most consider using. Response options included 6-month, 12-month, 24-month, or None of these durations. We followed this with an open-ended question asking about reasons for that choice.

Additional survey questions related to socio-demographic characteristics, fertility intentions, reproductive history, contraceptive history, general contraceptive preferences, family planning access barriers, and perceived behavioral control and subjective norms related to potential LAI use.

Data analysis

We used Stata v16 or higher to analyze all data. DCE data were analyzed using mixed multinomial logit models to account for heterogeneity of preferences across respondents and for within-respondent correlation [42], where participants’ choices are the dependent variable, and the levels of the attributes within the choice sets are the independent variables. Attributes were all categorical and were coded using effects coding, in which zero represents the mean effect across all attribute levels, rather than the omitted level (as is the case for dummy coding). This yields parameter estimates for all levels (and the parameter estimate for the omitted level is the negative sum of the parameters for the included levels).

We first ran a conditional logit model and examined indicators of left-right bias and opt-out bias. We then employed mixed-multinomial logit (MML) models to generate final mean preference weights for each level of each attribute, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also used these weights to estimate relative importance of each attribute in relation to the other attributes.

We also explored heterogeneity in expressed interest in the LAI with the TPP (chose a duration rather than “none of these durations”), and, among those expressing interest, choice of duration (coded as 6 vs. 12 + months), based on hypothesized independent variables, via bivariate logistic regression analyses. These variables included socio-demographic characteristics, fertility intentions, menstrual history, and contraceptive history and preferences. We did not conduct adjusted regression analyses due to high collinearity between many of the independent variables.

To analyze data from the open-ended question (regarding reasons for the LAI duration the participant chose), we exported each participant’s response into an excel spreadsheet, segmented by whether she chose No duration or 6-month, 12-month, or 24-month for the duration of the LAI with the TPP. One analyst then coded each entry into common emerging themes and counted the number of participants reflecting each theme.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Population Council Institutional Review Board (protocol 1013). All participants provided informed consent before completing the survey.

Results

In total, 1,029 women ages 18–44 years completed the online survey and were included in the analysis. Of 4,105 women completing screening questions, 1,186 were eligible and proceeded to the informed consent form (the largest reason for ineligibility was not currently using contraception and not interested in using contraception). Of these, 1,159 agreed to participate and proceeded with the survey, of whom 1,046 completed the survey. Seventeen participants were removed from the analysis because they realistically were not at risk of becoming pregnant since they reported currently using vasectomy as their form of contraception and reported having only one partner in the last year (with whom all were married/cohabiting).

As seen in Table 1, women were 28.6 years old on average (SD 8.2). About 63% of the sample reported being White, and 31% Black/African American; 12% reported being of Latino, Hispanic, or Spanish origin. Participants came from all US states (except Alaska), with a greater concentration (45%) in the South vs. Northeast, Midwest, or West (likely due to the quota over-representing African Americans, 57% of whom live in the South per the 2020 census [43]). Most women reported living in suburban (53%) or urban (29%) areas; 18% reported rural residence. Just under half (46%) reported completing high school education or higher; 18% reported household poverty.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics, reproductive history, and fertility intentions (n = 1,029)

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age – mean (SD) | 28.6 years | 8.2 years |

| n | % | |

| Race | ||

|

White Black/African American Native American Asian Pacific islander Other race |

647 318 17 77 70 35 |

62.9% 30.9% 1.7% 7.5% 0.7% 3.4% |

| Latino, Hispanic, or Spanish origin | 119 | 11.6% |

| Region of US | ||

|

Northeast Midwest South West (All US states represented, except Alaska) |

188 204 460 177 |

18.3% 19.8% 44.7% 17.2% |

|

Rural Suburban Urban |

182 546 301 |

17.7% 53.1% 29.3% |

| Completed high school education or higher | 477 | 46.4% |

| Household poverty a | 186 | 18.0% |

| Married/cohabiting (vs. not) | 336 | 34.7% |

| Number of children | ||

|

0 1 2 3 or more |

737 107 110 75 |

71.6% 10.4% 10.7% 7.3% |

| Want a child/another child | ||

|

No Yes Unsure |

504 311 214 |

49.0% 30.2% 20.8% |

| When wants (next) child | (n = 525) | |

|

Within 2 years 2–4 years 5+ Not sure |

43 130 240 111 |

8.4% 24.8% 45.7% 31.1% |

| How would you feel if found out pregnant | (n = 1,014) | |

|

Very upset A little upset Pleased Don’t know |

587 195 110 122 |

57.9% 19.2% 10.8% 12.0% |

| Ever had unintended pregnancy | (n = 1,010) | |

|

No Yes Not sure |

805 191 14 |

79.7% 18.9% 1.4% |

| Menses history (could select multiple) | ||

|

Heavy periods Spotting Irregular periods None of the above |

485 338 445 294 |

47.1% 32.9% 43.3% 28.6% |

aReported that there was “very often” or “fairly often” not enough money in the household for basic needs in last six months

About one-third (35%) of women reported being married/cohabiting. Most (72%) did not have children, 30% reported wanting a/nother child (21% were unsure). Among those possibly wanting a/nother child, almost half (45%) wanted to wait five or more years, 25% 2–4 years, and 8% within two years. A majority (58%) said they would be “very upset” if they found out they were pregnant. Nearly one-fifth (19%) reported ever having an unintended pregnancy. Nearly half reported a history of heavy and irregular periods, respectively.

Turning to contraceptive use history (Table 2), the most common currently used, and ever-used, contraceptive methods were birth control pills and male condoms. About one-fifth (20%) of women reported currently using withdrawal. Between 5 and 10% of women reported currently using the hormonal IUD, fertile days, contraceptive implant, or contraceptive injection. Just under 5% reported currently using, and 29% ever using, emergency contraception.

Table 2.

Contraceptive use history (in order of current use prevalence) (n = 1,029)

| Currently using | Ever used (but not currently) |

Never used | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth control pills | 37.4% | 35.4% | 27.2% |

| Male condoms | 35.7% | 38.5% | 25.9% |

| Withdrawal | 19.8% | 27.8% | 52.4% |

|

Hormonal IUD (Levonorgestrel IUD, Mirena, Liletta, Skyla) |

8.8% | 4.3% | 86.9% |

| Fertile days | 6.9% | 10.6% | 82.5% |

|

Contraceptive implant (Implanon, Nexplanon) |

5.0% | 4.8% | 90.3% |

|

Contraceptive injection (Depo-Provera) |

4.8% | 11.5% | 83.8% |

|

Emergency contraception (e.g., Plan B, Ella levonorgestrel) |

4.5% | 28.3% | 67.3% |

| Birth control patch | 2.6% | 8.1% | 89.3% |

| Female condoms | 2.4% | 6.6% | 91.0% |

| Vaginal ring (NuvaRing, Annovera) | 1.8% | 5.8% | 92.4% |

| Copper IUD (Paraguard) | 1.8% | 3.0% | 95.2% |

| Diaphragm (with/without spermicide) | 0.4% | 2.6% | 97.0% |

As shown in Table 3, most women reported being at least somewhat comfortable with the idea of hormonal contraception (i.e., selected at least 2 on a scale from 0 to 5), and 40% were comfortable (selected 4 or 5). 8% reported a high level of needle fear, and 46% a medium level. Over half of women reported ever discontinuing a contraceptive method for at least one of the unwanted effects/challenges we asked about, the most common being unwanted side effects (32% of the full sample) and unwanted effects on menses (24%). Among the 167 women reporting ever having used Depo-Provera, 68% reported unwanted effects. Almost one-quarter (23%) of women reported that other people they know experienced unwanted effects from Depo-Provera (with 40% of the sample saying they didn’t know anyone who has used this method). 10% of women reported experiencing barriers to getting to the family planning clinic, and 8% difficulty affording family planning visits in the last 5 years.

Table 3.

Other respondent experiences and preferences (n = 1,029)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Comfort with idea of hormonal contraceptive | ||

|

Not comfortable (0, 1) Somewhat comfortable (2, 3) Comfortable (4, 5) |

126 493 410 |

12.2% 47.9% 39.8% |

| Needle fear (general) | ||

|

Low (0–3) Medium (4–8) High (9–10) |

475 473 81 |

46.2% 46.0% 7.9% |

| Ever discontinued a contraceptive method due to: | ||

|

Unwanted effect on menses Unwanted side effects Pain/discomfort from device Unwanted effects on sex life Difficulty remembering to use Difficulty getting more method None of above |

243 331 157 141 157 118 448 |

23.6% 32.2% 15.3% 13.7% 15.3% 11.5% 43.5% |

| Ever experienced unwanted effects of Depo-Provera (among ever-users) |

(n = 167) 114 |

68.2% |

| Other people you know experienced unwanted effects from Depo-Provera | ||

|

No Yes Don’t know I don’t know anyone who has used Depo-Provera |

271 232 136 390 |

26.3% 22.6% 13.2% 37.9% |

| Experienced difficulty getting to family planning clinic in the last 5 years | 103 | 10.0% |

| Experience difficulty affording family planning visits in the last 5 years | 80 | 7.8% |

DCE results

Review of the conditional logit model findings (available in Supplemental Table 1) showed that selection of the opt-out (“neither option”) was acceptably low, as indicated by a statistically significant value for the alternative specific constant for the opt-out. (On average, 14% responded “neither” to a given choice set, ranging from 7 to 24%; data not shown). We therefore decided not to use the forced choice responses. In addition, there was no evidence of left-right bias in the way participants responded to task choices (as indicated by a non-significant coefficient related to left-right bias).

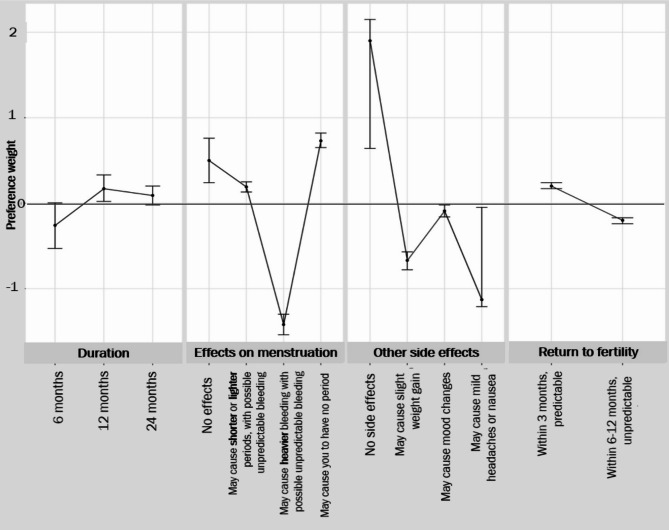

Mean preference weights for each attribute, from the mixed multinomial logit model, are shown in Fig. 2. (More detailed data from this model are included in Supplemental Table 1). Women had strong negative preferences for “may cause heavier/unpredictable periods” (p < 0.001); mild headaches/nausea (p < 0.001); slight weight gain (p < 0.001); mood changes (p < 0.01), and “6–12 months, unpredictable” return to fertility (vs. “3 months, predictable”, p < 0.001). They had positive preferences for “may cause you to have no period”, and “may cause shorter/lighter periods, with possible unpredictable bleeding” (p < 0.001). Women also significantly preferred the 12-month to the 6-month duration (p < 0.03), while there was no significant preference for the 24-month vs. 6-month duration.

Fig. 2.

Mean preference weights from mixed multinomial logit model (n = 1,029)

Note: Each mean preference weight represents the average strength of preference regarding the particular attribute level, across the sample. Positive values reflect a preference for that attribute level, negative values represent preference against that attribute level; values for which the confidence interval overlaps 0 reflect no statistically significant preference

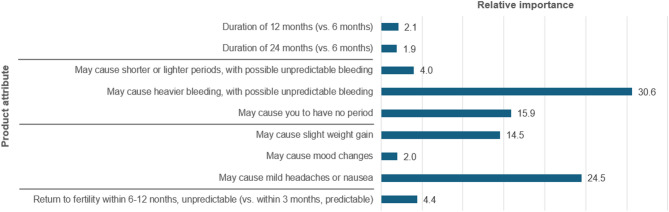

Estimates of the importance of each attribute relative to all other attributes (Fig. 3) indicate that the most important are the potential for heavy bleeding that is unpredictable, followed by mild headache or nausea, causing no period, and slight weight gain. The least important attributes are 12-month (vs. 6-month) duration; the potential for causing mood changes, and 24-month (vs. 6-month) duration.

Fig. 3.

Relative importance estimates for product attributes

Relative importance estimates were computed using the means from the MMNL main effects model. The absolute value of the mean of each attribute’s parameters was multiplied by the difference between the attribute levels’ highest and lowest values to give the maximum effect. The relative importance values were then calculated by considering the proportion of the maximum effect in the context of the total for each attribute

Interest in LAI with target product profile

As seen in Table 4, when asked directly about which duration of the LAI with TPP they would most consider using, most participants (92.4%) expressed interest in a duration rather than “None of these durations”. Nearly equal numbers reported preferring the 6-month, 12-month, and 24-month durations, respectively. In addition, about three-quarters of women choosing the 6- or 12-month duration said they would consider a longer duration if they used the shorter duration first with no unwanted effects.

Table 4.

LAI duration women would consider, given target product profile (TPP)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| LAI duration women would most consider using, given no/minimal side effects, no/minimal effect on menses, and return to fertility within 3 months (i.e., TPP) | ||

|

6 months 12 months 24 months None of these durations |

320 319 312 78 |

31.1% 31.0% 30.3% 7.6% |

| How soon after the method you chose was approved, would you want to start using it? (among women not responding “None of these durations” above) | (n = 951) | |

|

Right away (within next 6 months) In 6–12 months In 1–2 years In 2–5 years In more than 5 years Don’t know |

327 220 172 64 18 150 |

34.4% 23.1% 18.1% 6.7% 1.9% 15.8% |

| Among those choosing 6-month duration: Would consider 12- or 24-month duration if they used the 6-month duration first with no unwanted effects |

(n = 320) 238 |

74.4% |

| Among those choosing 12-month duration: Would consider 24-month duration if they used the 12-month duration first with no unwanted effects |

(n = 319) 234 |

76.2% |

| How concerning is non-reversible nature of LAI (among full sample) | ||

|

Not concerning A little concerning Somewhat concerning Very concerning (Main reasons reported for finding it concerning: Any side effects could last a long time; uncertainty of not knowing what effects it could have would make me worried) |

191 420 253 165 |

18.6% 40.8% 24.6% 16.0% |

| Change in likelihood of using contraceptive LAI if it also prevented HIV (at > 99% effectiveness)(among full sample) | ||

|

No more likely Somewhat more likely Much more likely |

210 256 563 |

29.4% 24.9% 54.7% |

When women were asked how soon they would want to start using the LAI once it is approved, about one-third (34%) said right away, 23% within 6–12 months, and 18% in in 1–2 years.

Most women were concerned with the non-reversible nature of the LAI, with 41% of the full sample finding it “a little concerning”, 25% “somewhat concerning”, and 16% “very concerning”. When provided a list of reasons they would find it concerning, the most commonly selected were “Any side effects could last a long time” and “Uncertainty of not knowing what effects it could have would make me worried”.

We also asked about potential interest in a long-acting contraceptive injectable that also prevents HIV (i.e., a multipurpose prevention technology; noting several such injectables are currently in development, albeit not long-acting). Over half (55%) of all women said they would be “much more likely” to use the contraceptive LAI if it also prevented HIV, and 25% said “somewhat more likely”.

Table 5 presents results of logistic regression analyses to identify characteristics of women who were not willing to use any duration of the LAI with the TPP. These women had greater odds of being highly uncomfortable with hormonal contraception (p < 0.001), having extreme needle fear (p < 0.001), and living in a rural area (p = 0.013). The following respondent characteristics were not associated with non-willingness to consider using the LAI: age, marital/cohabiting status, race, ethnicity, education, household poverty, wanting a child/more children, timing of wanting a child, own/others’ negative experience with Depo-Provera, barriers getting to clinic, barriers affording family planning visits.

Table 5.

Associations with greater non-willingness to consider using an LAI with the TPP (n = 1,029)

| % not willing to consider any LAI duration | OR (95% CI) p-value |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Comfortable with hormonal contraception (2–5) Highly uncomfortable with hormonal contraception (0,1) |

5.0% 26.2% |

3.19 (1.72, 5.92) p < 0.001 |

|

Non-extreme needle fear (0–8) Extreme needle fear (9–10) |

6.7% 18.5% |

3.19 (1.72, 5.92) p < 0.001 |

|

Suburban/urban residence Rural residence |

6.6% 12.1% |

1.92 (1.15, 3.23) p = 0.013 |

Table 6 shows results of logistic regression analyses to identity characteristics of women who were interested in a longer duration of the LAI (with TPP) – coded as 12- or 24-month vs. 6-month (a binary variable). Women choosing a longer duration had higher odds of not wanting a child in the next 2 years, or even within the next 5 years, and of being very upset if they found out they were pregnant. They also had higher odds of being comfortable with hormonal contraception, having little/no concern with non-reversibility, as well as having a history of discontinuing a contraceptive method due to difficulty getting more of it. They had lower odds of having previously discontinued a method due to unwanted effects on their period. Women interested in a longer duration were also more likely to be currently using hormonal contraception, as well as one of the long-acting methods already available (i.e., an IUD or implant). Regarding differences by socio-demographic characteristics, Black/African American women (vs. other races) were less interested in a longer duration, while White (vs. other races) were more interested. Younger women (age 18–24 vs. 25–44 years), and women living in poverty (vs. not), were also more interested in a longer duration.

Table 6.

Associations with longer duration preference (12 or 24 months, vs. 6 months), among women who would consider using an LAI with the TPP (n = 951)

| % selecting 12- or 24-month duration (vs. 6-month) | OR (95% CI) p-value |

|

|---|---|---|

| Fertility intentions | ||

|

Wants child within 2 years Doesn’t want child within next 2 years |

34.2% 67.8% |

4.00 (2.08, 7.69) p < 0.001 |

|

Wants child within next 5 years or unsure when Doesn’t want child within next 5 years |

54.5% 71.0% |

2.04 (1.52, 2.70) p < 0.001 |

|

Not very upset Very upset if found out she was pregnant |

58.2% 72.6% |

1.91 (1.45, 2.50) p < 0.001 |

| Contraceptive preferences and history | ||

|

Highly uncomfortable with hormonal contraception (0,1) Comfortable with hormonal contraception (2–5) |

55.4% 69.9% |

1.88 (1.39, 2.56) p < 0.001 |

|

High/some concern with non-reversibility Little/no concern with non-reversibility |

54.1% 68.3% |

1.82 (1.26, 2.63) p = 0.001 |

|

Did not previously discontinue a method due to unwanted effects on period Previously discontinued a method due to unwanted effects on period |

68.7% 59.1% |

0.66 (0.49, 0.90) p = 0.008 |

|

Did not previous discontinue a method due to difficulty getting more of it Previously discontinued a method due to difficulty getting more of the method |

65.0% 76.8% |

1.78 (1.13, 2.83) p = 0.014 |

|

Not currently using a hormonal method Currently using a hormonal method |

58.1% 72.2% |

1.87 (1.42, 2.45) p < 0.001 |

|

Not currently using a long-acting method Currently using a long-acting methoda |

63.8% 79.6% |

2.21 (1.45, 3.37) p < 0.001 |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||

|

Not Black/African American Black/African American |

69.4% 59.5% |

0.64 (0.49, 0.86) p = 0.003 |

|

Not White White |

62.3% 68.7% |

1.33 (1.01, 1.76) p = 0.043 |

|

Age 18–24 years Age 25–44 years |

69.8% 63.5% |

0.76 (0.58, 0.99) p = 0.043 |

|

No household poverty Household poverty |

65.0% 72.8% |

1.44 (0.99, 2.09) p = 0.052 |

a Long-acting methods included IUDs and implants

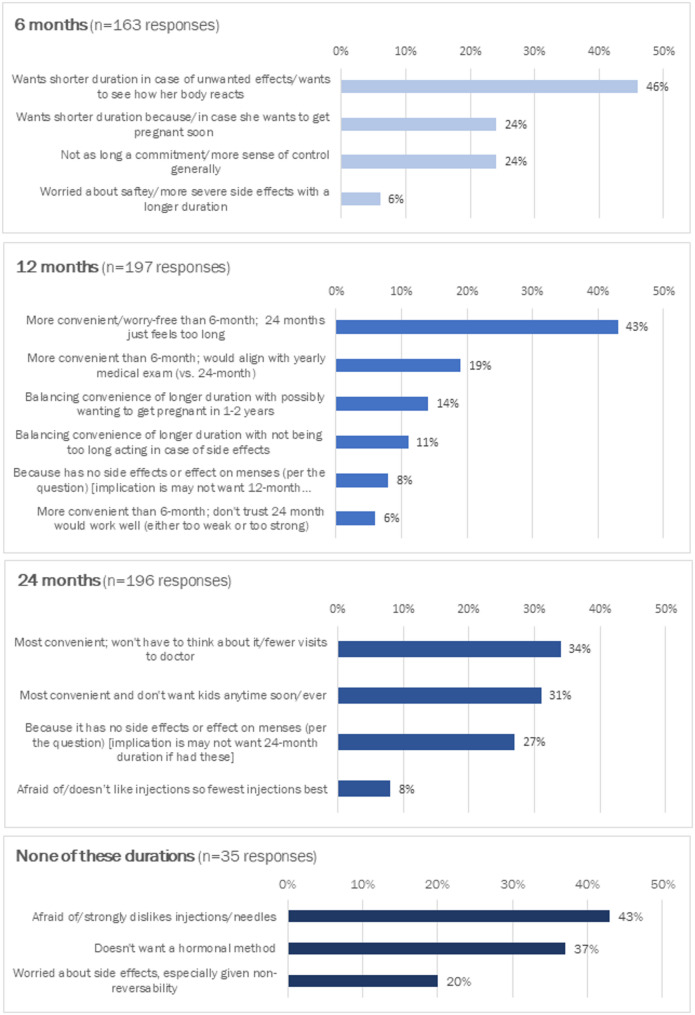

About three-quarters of all participants provided responses to the open-ended question regarding reasons they chose the specific LAI duration (or none of the durations). In most cases the meaning of the text women wrote in – although usually brief – was interpretable. We categorized responses by common themes (Fig. 4). The main reasons for choosing the 6-month duration had to do with guarding against unwanted effects/seeing how her body reacts before choosing a longer duration, and because/in case she wants to get pregnant soon. The main reasons for choosing the 12-month duration involved balancing convenience of the longer duration with guarding against potential unwanted effects or potentially wanting to get pregnant in 1–2 years, as well as aligning with a yearly medical/family planning visit. The main reasons for choosing the 24-month duration were highly valuing convenience and strong desire to not have any/more children. Finally, the main reasons for choosing none of the durations centered around strong aversion to hormones and extreme needle fear.

Fig. 4.

Stated reasons for preferred LAI duration

Discussion

This study among a diverse sample of 1,029 US women revealed high potential interest in long-acting injectable hormonal contraception. However, interest decreases substantially if women are told the product may cause heavier/unpredictable periods, side effects (mild headaches/nausea; slight weight gain), or delayed/unpredictable return-to-fertility. A longer duration (12 or 24 months) is preferred to a 6-month duration of contraceptive effectiveness, although duration was not a primary driver of LAI interest. There was substantial heterogeneity in interest in and preferred duration of the LAI between women with different characteristics. Having a 6-month option appears important especially for women who may want to get pregnant within the next few years and those concerned about hormones (who often want to try a shorter duration first before the longer duration).

We were surprised that in the DCE, duration was not more highly prioritized in relation to the other attributes. It may be that unwanted effects of an LAI are to some extent “dealbreakers” for the method, but if absent women then consider the potential benefits of a longer duration. Notably, there was remarkably high interest (> 90%) in the LAI without these unwanted effects (as is anticipated to be the case for the injectable being developed). This high interest is reinforced by the fact that most women said they would want to use the product within the next year. Moreover, many women retained some concern about the longer durations, with about 40% at least somewhat concerned by the non-reversibility of an LAI.

There were diverse preferences regarding duration, about evenly split between 6 and 12 months (both of which are target durations for this product), as well as 24 months (a hypothetical longer duration). This preference diversity may have also masked relative importance of duration in the DCE model. Based on responses to the open-ended questions, women seemed to have clear rationales for their duration preference. In our view, the main takeaway is that most women do prefer a longer duration (given the TPP), but that some women feel strongly about the need for a 6-month duration for the reasons noted.

Along with negative preferences for several unwanted effects, women also had positive preferences for the LAI potentially causing them to have no period. The relatively large standard deviation suggests heterogeneity in this preference; while many women may prefer for the LAI to cause no period, others may not. This heterogeneity may be due to divergent preferences related to menses suppression, as documented in previous research [44, 45]; unfortunately, we did not capture such preferences in the survey so we could not gauge whether this was the case in our study.

Results of logistic regression analyses provide insight into characteristics of women who chose “none of these durations” (indicating non-interest in using the LAI), as well as women who would opt for a longer (12- or 24-month) vs. shorter (6-month) duration. High discomfort with hormones, extreme fear of needles, and rural residence emerged as factors associated with non-interest in the LAI. Still, while statistically significant, an overwhelming majority (> 80%) of women in each of these categories did choose a duration (i.e., expressed some level of willingness, vs. choosing “none of these durations”). Regarding preference for a longer LAI duration, comfort with hormones also emerged as a strong predictor, as did current use of a hormonal method, and no history of discontinuing a contraceptive method due to effect on menses. Current use of a long-acting contraceptive method (an IUD or implant) was also associated with longer duration preference; this may reflect general preference for longer-acting methods rather than interest in switching from one of these long-acting methods to an LAI. Fertility intentions were even stronger predictors of wanting a longer duration, with women not wanting a child in the next 2 years, or even 5 years, and being very upset if they found out they were pregnant, having 2–4 times the odds of choosing a longer duration. This finding is underscored by the open-ended responses. In terms of socio-demographics, Black/African American women had lower odds of wanting a longer duration, vs. White women who had higher odds; younger women had higher odds of wanting a longer duration, as did women living in poverty (although this last finding was only marginally significant, at p = 0.052). Reasons for these associations are not fully evident; however, it may be that certain socio-demographic characteristics predispose individuals to greater or lesser receptiveness to and trust of a medical innovation such as an LAI.

Beyond LAIs for contraception, the evidence generated in this study could prove useful in understanding how individuals make decisions about LAI products, including LAI pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention – such as Cabotegravir [46, 47] (2-month duration) and Lenacapavir [48, 49] (6-month duration) – as well as future development of LAI multipurpose prevention technologies (MPTs) to simultaneously prevent pregnancy, HIV, STIs, etc. (Notably, over half (55%) of our respondents said they would be much more likely, and one-quarter somewhat more likely, to use the contraceptive LAI if it also prevented HIV, in line with other studies documenting high interest in MPTs [50, 51]). It seems likely that an LAI for indications other than contraception would similarly be of high interest to end-users for reasons of convenience, peace of mind, and better outcomes due to improved adherence. However, it is also likely that end-users will be sensitive to potential unwanted effects, and that confidence will likely improve as those unwanted effects are ruled out via clinical trials and implementation studies. Our findings regarding shorter duration options may have some parallels to LAIs for other indications, e.g., antiretroviral (ARV)-based PrEP for HIV prevention. Some end-users may prefer to start with a shorter duration first to see how it affects their body (even if unwanted effects are known to be rare), before trying a longer duration. In addition, end-users with anticipated shorter-term or intermittent periods of perceived HIV risk may prefer shorter durations of exposure to ARVs.

This study has several important limitations. First, the study is based on hypothetical willingness to use a novel contraceptive method, which may introduce uncertainty or bias in responses. As there are no existing LAI contraceptives on the market, we can only use a hypothetical approach to help inform product development efforts to ensure alignment with end-user needs. Second, in the DCE, the strong negative preferences for certain effects on menses and side effects substantially outweighed preferences for duration, which limited our ability to use DCE data to assess tradeoffs between these attributes and longer durations. Third, we cannot confirm the representativeness of the national sample to the population of US women meeting study eligibility criteria; due to our purposive oversampling of young women (ages 18–24 years) and Black/African American women, the sample certainly over-represents those subgroups.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings support the potential for the LAI to fill an unmet need for contraception among women in the US, who, as our data also underline, continue to use contraceptive methods with high failure rates (e.g., pills, condoms, withdrawal) and to experience high rates of contraceptive discontinuation, including for Depo Provera, as well as unintended pregnancy. The diversity of preferences for LAI durations highlights the need for contraceptive developers to continue to aspire to broaden choice. Continued end-user research regarding varied preferences and tradeoffs is needed to optimize LAI products as they are being developed and rolled out. Such research will add to the growing body of evidence regarding LAIs for different indications, helping maximize long-term public health impact.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who took part in the survey and qualitative research. We also are grateful to Dr. Matthew Quaife for his advice about the discrete choice experiment (DCE) design, to Brady Zieman for his support with DCE choice set programming, and to Dr. Jessica Sales, Michelle Nguyen, and Shakti Shetty at Emory University for their work on the qualitative research.

Abbreviations

- API

Active pharmaceutical ingredient

- ARV

Antiretroviral

- CI

Confidence interval

- DCE

Discrete choice experiment

- LAI

Long-acting injectable

- LARC

Long-acting reversible contraceptive

- MPT

Multipurpose prevention technology

- PrEP

Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- TPP

Target product profile

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AG, LBH, DRF, TA; Methodological design: All authors; Data collection: GS, AG, TA; Data analysis: AG, TA, GS; Writing-original draft: AG, TA; Writing-review & editing: All authors.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R43HD108820. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data availability

Upon acceptance of this manuscript, data underlying the analyses presented in this manuscript will be placed in a public repository (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/popcouncil).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Population Council Institutional Review Board (protocol 1013). All participants provided informed consent before completing the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

David Friend, Elizabeth Proos, and Isabella Johnson are employees and equity holders of Daré Bioscience, Inc., while Nathan Dormer and Ulrike Foley hold the same roles at Adare Pharma Solutions. Both companies have a commercial interest in products related to this research, which may be perceived as a potential conflict of interest. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Singh S, Darroch JE, Ashford LS, Vlassoff M. Adding it up: the costs and benefits of investing in family planning and maternal and newborn health. Guttmacher Institute; 2009.

- 2.Sedgh G, Ashford LS, Hussain R. Unmet need for contraception in developing countries: examining women’s reasons for not using a method. New York: Guttmacher Institute. 2016;2:2015-6.

- 3.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the united states, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonfield A, Hasstedt K, Kavanaugh M, Anderson R. The social and economic benefits of women’s ability to determine whether and when to have children. Guttmacher Institute. 2013. 2020.

- 5.Ali MM, Cleland JG, Shah IH, Organization WH. Causes and consequences of contraceptive discontinuation: evidence from 60 demographic and health surveys. 2012.

- 6.Jain A. The leaking bucket phenomenon in family planning: Champions4Choice. 2014.

- 7.Ross J, Stover J. Use of modern contraception increases when more methods become available: analysis of evidence from 1982–2009. Global Health: Sci Pract. 2013;1(2):203–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley SE, Casterline JB. Understanding unmet need: history, theory, and measurement. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45(2):123–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westhoff C. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (Depo-Provera®): a highly effective contraceptive option with proven long-term safety. Contraception. 2003;68(2):75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knox SA, Viney RC, Street DJ, Haas MR, Fiebig DG, Weisberg E, et al. What’s Good Bad about Contracept Products?? Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(12):1187–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the united States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asheer S, Berger A, Meckstroth A, Kisker E, Keating B. Engaging pregnant and parenting teens: early challenges and lessons learned from the evaluation of adolescent pregnancy prevention approaches. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(3):S84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potter LS, Dalberth BT, Cañamar R, Betz M. Depot Medroxyprogesterone acetate pioneers: a retrospective study at a North Carolina health department. Contraception. 1997;56(5):305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Family planning: a global handbook for providers: 2011 update: evidence-based guidance developed through worldwide collaboration. 2011.

- 15.Myers JE, Ellman TM, Westhoff C. Injectable agents for pre-exposure prophylaxis: lessons learned from contraception to inform HIV prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015;10(4):271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, Petrosky E, Madden T, Eisenberg D, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(5):1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beasley A, White KOC, Cremers S, Westhoff C. Randomized clinical trial of self versus clinical administration of subcutaneous depot Medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception. 2014;89(5):352–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cover J, Ba M, Lim J, Drake JK, Daff BM. Evaluating the feasibility and acceptability of self-injection of subcutaneous depot Medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in senegal: a prospective cohort study. Contraception. 2017;96(3):203–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minnis AM, Krogstad E, Shapley-Quinn MK, Agot K, Ahmed K, Danielle Wagner L, et al. Giving voice to the end-user: input on multipurpose prevention technologies from the perspectives of young women in Kenya and South Africa. Sex Reproductive Health Matters. 2021;29(1):1927477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romano JW, Van Damme L, Hillier S. The future of multipurpose prevention technology product strategies: Understanding the market in parallel with product development. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;121:15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callahan RL, Brunie A, Mackenzie AC, Wayack-Pambè M, Guiella G, Kibira SP, et al. Potential user interest in new long-acting contraceptives: results from a mixed methods study in Burkina Faso and Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0217333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolley EE, McKenna K, Mackenzie C, Ngabo F, Munyambanza E, Arcara J, et al. Preferences for a potential longer-acting injectable contraceptive: perspectives from women, providers, and policy makers in Kenya and Rwanda. Global Health: Sci Pract. 2014;2(2):182–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Litman L, Robinson J. Conducting online research on Amazon mechanical Turk and beyond. Sage; 2020.

- 25.CloudResearch. What is Prime Panels? 2025. Available from: https://www.cloudresearch.com/support/

- 26.Hynes JS, Sales JM, Sheth AN, Lathrop E, Haddad LB. Interest in multipurpose prevention technologies to prevent hiv/stis and unintended pregnancy among young women in the united States. Contraception. 2018;97(3):277–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hynes JS, Sheth AN, Lathrop E, Sales JM, Haddad LB. Preferred product attributes of potential multipurpose prevention technologies for unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections or HIV among US women. J Women’s Health. 2019;28(5):665–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss A, Hartman J, Litman R, Online Research Changes L. But CloudResearch Consistently Delivers The Highest Quality Data at the Lowest Price 2025. Available from: https://www.cloudresearch.com/resources/blog/cloudresearch-highest-quality-data-lowest-cost/

- 29.Chandler J, Rosenzweig C, Moss AJ, Robinson J, Litman L. Online panels in social science research: expanding sampling methods beyond mechanical Turk. Behav Res Methods. 2019;51:2022–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas BD, Ewell PJ, Brauer M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: comparisons between mturk, prolific, cloudresearch, qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(3):e0279720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mensch BS, van der Straten A, Katzen LL. Acceptability in microbicide and PrEP trials: current status and a reconceptualization. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(6):534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merkatz RB, Plagianos M, Hoskin E, Cooney M, Hewett PC, Mensch BS. Acceptability of the nestorone®/ethinyl estradiol contraceptive vaginal ring: development of a model; implications for introduction. Contraception. 2014;90(5):514–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2020;2(4):314–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helter TM, Boehler CEH. Developing attributes for discrete choice experiments in health: a systematic literature review and case study of alcohol misuse interventions. J Subst Use. 2016;21(6):662–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ResearchMatch. What is ResearchMatch? 2024 [cited 2024 December 17]. Available from: https://www.researchmatch.org/

- 40.ChoiceMetrics. Ngene 1.2 user manual & reference guide. Australia; 2018.

- 41.Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFadden D, Train K. Mixed MNL models for discrete response. J Appl Econom. 2000;15(5):447–70. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frey WH. A ‘New Great Migration’ is bringing Black Americans back to the South. 2022.

- 44.Polis CB, Hussain R, Berry A. There might be blood: a scoping review on women’s responses to contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes. Reproductive Health. 2018;15:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeh PT, Kautsar H, Kennedy CE, Gaffield ME. Values and preferences for contraception: a global systematic review. Contraception. 2022;111:3–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delany-Moretlwe S, Hughes JP, Bock P, Ouma SG, Hunidzarira P, Kalonji D, et al. Cabotegravir for the prevention of HIV-1 in women: results from HPTN 084, a phase 3, randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10337):1779–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Landovitz RJ, Donnell D, Clement ME, Hanscom B, Cottle L, Coelho L, et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bekker L-G, Das M, Abdool Karim Q, Ahmed K, Batting J, Brumskine W, et al. Twice-yearly Lenacapavir or daily F/TAF for HIV prevention in cisgender women. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(13):1179–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelley CF, Acevedo-Quiñones M, Agwu AL, Avihingsanon A, Benson P, Blumenthal J, et al. Twice-Yearly Lenacapavir for HIV prevention in men and Gender-Diverse persons. New England Journal of Medicine; 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Bhushan NL, Ridgeway K, Luecke EH, Palanee-Phillips T, Montgomery ET, Minnis AM. Synthesis of end-user research to inform future multipurpose prevention technologies in sub-Saharan africa: a scoping review. Front Reproductive Health. 2023;5:1156864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedland B, Plagianos M, Savel C, Kallianes V, Martinez C, Begg L, et al. Women want choices: opinions from the share. Learn. Shape global internet survey about multipurpose prevention technology (MPT) products in development. AIDS Behav. 2023;27(7):2190–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon acceptance of this manuscript, data underlying the analyses presented in this manuscript will be placed in a public repository (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/popcouncil).