Abstract

Background

Today, the majority of individuals depend significantly on the Internet in daily life. In Jordan, the Internet penetration rate is improving year to year, but it is not still at a high level compared to the rest of the world and neighboring Asian countries. Due to a lack of satisfactory information, it is important to assess internet use, spatial distribution and determinants of internet use among reproductive-age women in Jordan.

Method

Secondary data from JPFHS 2023 were used to analyze 42,692 women aged 15–49 years. Spatial analysis was used using ArcGIS 10.4.1. The Bernoulli model was used by applying Kuldorff’s methods using SaTScan 10.1.2 software to analyze the purely spatial clusters of internet use. A multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression was performed to estimate community variance to identify individual and community-level factors associated with internet use. All models were fitted in STATA version 17.0 and finally, the AOR with a corresponding 95%confidence interval was reported.

Result

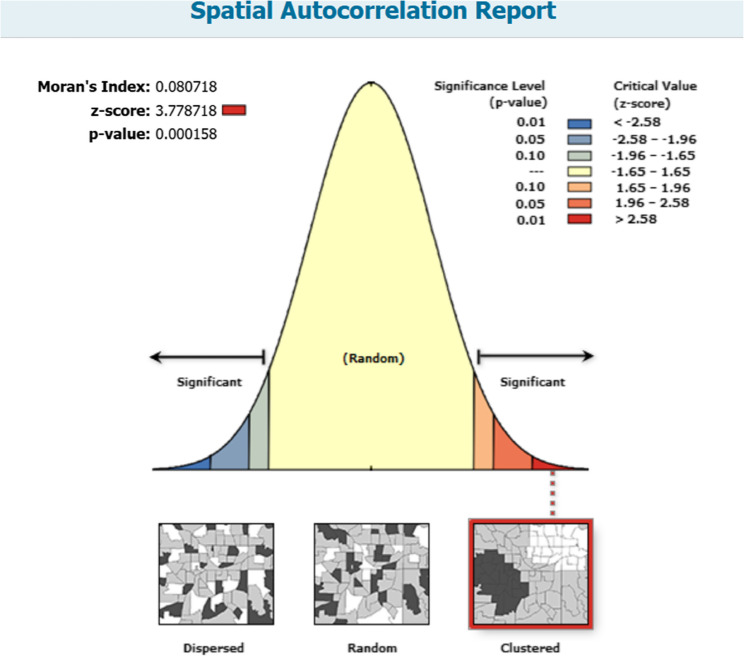

The magnitude of internet use was 80.37%±95% CI (79.99–80.75). The overall mean of women was 38.24 ± 7.31, with the age range 35–49 years constituting the larger group (69.09%). Women with secondary and above education [AOR = 4.65;95% CI (3.74,5.78)], working [AOR = 1.86;95% CI (1.67,2.08)], women age [AOR = 0.78; 95% CI (0.64,0.94)], middle households [AOR = 1.65 95% CI (1.50,1.81)], divorced [AOR = 0.62; 95% CI (0.47,0.80)], has personal electron wallet [AOR = 1.60 95% CI (1.41,1.80)], and own mobile phone [AOR = 33.34; 95% CI (28.41,39.12)] has higher odds of internet use. The spatial distribution in internet use was found to be nonrandom (global Moran’s I = 0.08, p value < 0.001). Sixty-six primary clusters were identified in Irbid region with relative likelihood of 1.18 and LLR of 273.26, at p value < 0. 0001.

Conclusions

Internet use among reproductive age women in Jordan is 80.37% and has spatial variation across the country. Both community and individual level determinants affect internet use in Jordan. Consequently, women’s Internet use might be enhanced by educating them, empowering to use personal electronic wallet and mobile phone and strengthening household income.

Keywords: Internet use, Spatial distribution, Reproductive age women, Jordan

Introduction

Internet is a worldwide web public computer network [1]. It links one million computers around worldwide. Today, the majority of individuals depend significantly on the Internet in ordinary life [2]. Internet use is the use of the online by people whether they are at homebased, at work place, or in an organization [3]. The development of technology, particularly the Internet, has the influence to change every element of life and offers boundless access to a wide range of evidence from across the globe.

Today more than 57% of the world population are current internet users [4]. The internet penetration rate in Asia was 65.9% [5] and in Jordan 88% [6]. Within Asia the internet penetration rates are relatively high in some countries in Singapore 92% [7], Republic of Korea 97% [8] and Japan 93.3% [9]. The use of the internet for health-related message is expanding and is becoming increasingly important to the healthcare system. Across the health sector and health policy, it has been used for a variety of programs. Half of women in low-income nations do not have access to the internet, and the gap in mobile internet access in low- and middle-income countries is 23%. This implies that, in contrast to males, women are meaningfully omitted out on the positive effects of internet use on their health [1, 10].

Based on International Technology Union (ITU) data at the start of 2023, female internet use as a percentage of the total population is estimated at 83% [11]. South West Asia is one of the regions of the world where a number of factors that influence internet use have been identified. These are age [12, 13], education level [14–17], marital status [12], wealth index [1, 18, 19], having mobile phone [20], place of residence [21] and has personal electronic wallet [22] which are significantly associated with internet use.

According to a Thailand study, 10.83% of older peoples used the internet to obtain health-related information. This study found that all sociodemographic characteristics, with the exception of age and marital status, had an effect on looking in the Internet for health-related information [23]. Lack of regular internet connectivity restricts access to certain health services in developing nations like Bangladesh, including general counseling and knowledge about medications [24]. A study conducted in Bangladesh, adolescent married women had greater information needs during pregnancy. The information collected during this time has an influence on labor, delivery, and the postpartum period [25]. According to World bank, in Jordan’s the data indicates that there is a gender gap in internet usage, with 10.9% fewer women using the internet compared with men [26].

Using the internet to obtain health information gives women the chance to make health-related decisions and enhance their health. However, there is insufficient data regarding the prevalence of internet use, regional variations, and related factors, especially among Jordan women of reproductive age who are looking for health information.

Therefore, this study examined data from the Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS) 2023 to determine internet use, geographical variance, and factors related to internet use among Jordanian women of reproductive age. No study in Jordan has previously utilized nationally representative data to examine internet utilization. The findings will be crucial in developing evidence-based interventions to improve women’s internet usage habits for accessing updated health information. This will also serve as a valuable resource for future research in this field. The question of this study were:

What is the spatial distribution of internet use among reproductive-age women in Jordan?

What are the individual-, household-, and community-level determinants associated with internet use?

Methods

Study design, setting and period

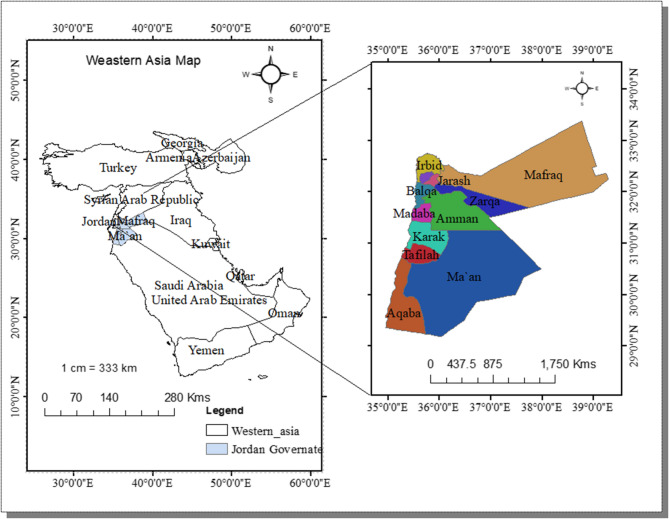

The study was conducted in Jordan. Jordan is one of the mid-sized countries in the region by population. The current population of Jordan is 11,520,684 of March 6, 2025, with 85.1% living in Urban areas based on Worldometer elaboration of the latest United Nation data [27]. Currently in Jordan there are 12 regional states (Amman, Balqa, Zarqa, Madaba, Irbid, Mafraq, Jarash, Ajloun, Karak, Tafiela, Aqaba and Ma’an (Fig. 1). The 2023 JDHS data were collected from 12 regions. This study used secondary data from JPFHS 2023. The Department of Statistics (DOS) in collaboration with United State Agency for International development (USAID), the United Nations Children Fund’s (UNICEF), the Untied Nation Population Fund’s (UNFPA) and the ICF conducted a community based cross-sectional study from January to June 2023 [28]. The women’s data (IR) from JDHS were used.

Fig. 1.

Study area map (Jordan)

Source and study population

The source population included all reproductive-age women (15–49 years) residing in Jordan before the survey, while the study population comprised women in selected enumeration areas (EAs) during the survey period. Eligible participants were usual household members or women who stayed in the household the night before the survey; areas with missing geographic coordinates and institutionalized women’s in prisons or hospitals were excluded. The analysis used the Individual Record (IR) dataset from JPFHS 2023, with a final sample of 42,692 women (15–49 years) with complete data. Sampling weights were applied to correct for nonproportional allocation across regions and urban/rural strata, ensuring nationally representative estimates.

Sampling procedure

The Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS) 2023 used the 2015 Jordan Population and Housing Census (JPHC) as its sampling frame, employing a stratified, cluster-based, multistage sampling design to select a nationally representative sample across Jordan’s 12 administrative governorates. The 12 governorates were first stratified into urban and rural areas, creating 26 sampling strata, each sampled independently to ensure proportional geographic and residential representation. Governorates were progressively divided into smaller units, and 970 clusters (PSUs) were selected using a probability-proportional-to-size (PPS) approach. The final report of the study includes specifics about the JPFHS 2023 study methodology [28]. The data were obtained from the DHS Program through an online request by explaining its objective and significance (https://www.dhsprogram.com).

Study variables

The study’s outcome variable was internet use, which is binary (“1” use the internet or “0” not use the internet) depending on whether the women use the Internet in the last 12 months or not. If the responses of ‘never and yes but don’t know when’ are taken as not used Internet(No), else used Internet (Yes) [1, 29]. Independent variables are respondent education, respondent occupation, respondent age, wealth status, marital status, has personal electronic wallet, own a mobile telephone, region community media and place of residence.

Data management and analysis

Data analysis was done using STATA 17, ArcMap 10.4.1, and SatScan 10.1.2 software. Prior to data processing, all frequency distributions were weighted (v001/1,000,000) in order to ensure that the EDHS sample was representative and to gain accurate estimates and standard errors. Data was thoroughly cleaned, and missing values were imputed to ensure completeness. After cleaning, the data were cross-tabulated to the outcome variable with cluster and exported to Microsoft Excel. Excel and GPS data were then combined for spatial analysis. text, tables, and figures were used to present descriptive and summary statistics.

Multilevel analysis

Descriptive and summary statistics were performed using STATA 17.0. The multilevel model was favored above the regular model due to a significant LR test (p < 0.05), which accounted for error terms at each level and variance changes. Also because the DHS data have a hierarchical structure, where individuals are nested within clusters or enumeration areas. Using traditional logistic regression in this situation could result in skewed results and inaccurate conclusions [30]. it ignores the clustered nature of DHS data, where individuals are nested within enumeration areas. This can lead to underestimation of standard errors, resulting in inflated Type I error rates—i.e., finding statistically significant associations where none exist. A multilevel model corrects for this by accounting for intra-cluster correlation, thereby providing more reliable estimates and valid statistical inferences. kindly see the updated version of the manuscript. Therefore, a multilevel binary logistic regression was applied.

The analysis employed four hierarchical models to examine factors associated with internet use. The null (empty) model served as a baseline, containing no explanatory variables, to assess the overall variance in internet use without any adjustments. This model helped partition variance between individual and community levels, providing a reference point for subsequent models. Model I introduced individual-level factors, including demographic variables and behavioral or socioeconomic factors. This model identified which personal characteristics were significantly associated with internet use, isolating their effects from broader contextual influences. Model II focused exclusively on community-level variables, such as geographic location, regional infrastructure. By excluding individual factors, this model highlighted macro-level determinants of internet access, revealing whether community characteristics independently influenced usage patterns [31].

Finally, Model III combined both individual and community-level factors to assess their joint influence. This comprehensive model tested whether community effects persisted after accounting for individual differences and explored potential cross-level interactions. By comparing these models, the analysis determined the relative importance of personal versus contextual factors and identified key predictors of internet adoption. This stepwise approach ensured a nuanced understanding of how multilevel influences shape digital access [32].

A comparison of the models was conducted using the Deviance (−2LL), LLR, AIC, BIC. By using multiple criteria (Deviance, AIC, and BIC), a more robust and comprehensive assessment of model performance and parsimony was achieved, guiding the selection of the most appropriate multilevel model. The model considered best-fitting was the one with the lowest deviation or the highest LLR. We calculated the Proportional Change in Variance (PCV), Median Odds Ratio (MOR), Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and likelihood ratio test to assess the variation between clusters. By measuring the percentage of the overall observed individual variance in internet use that may be attributed to changes between clusters, ICC quantifies the degree of heterogeneity of internet use between clusters. The multilevel mixed-effect regression p value < 0.05 and Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) with a 95% CI were used to identify significant predictors of internet usage.

Spatial analysis

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

The study employed the spatial autocorrelation measure, Global Moran’s I, to determine whether Internet use for health related information among Jordanian women of reproductive age is dispersed, clustered or random distributed. Moran’s I is a spatial statistic that quantifies autocorrelation, producing a single value between − 1 and + 1. A value close to −1 indicates dispersion, near + suggests clustering, and around zero signifies a random distribution. A statistically significant Moran’s I (P < 0.05) confirms the presence of spatial autocorrelation, indicating that Internet use is not randomly distributed, leading to the rejection of null hypothesis [33].

Getis Ord gi* hotspot analysis

The Getis-Ord Gi, or hotspot analysis was used to assess spatial autocorrelation variations across study locations by computing Gi* values for each region. To determine statistically significant clustering at p < 0.05 with a 95% CI, the z-score was calculated. A random pattern is suggested if the z-score falls between − 1.96 and + 1.96, as the p-value < 0.05, meaning null hypotheses cannot be rejected. If the z-score is beyond this range, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a significant spatial pattern. A z-score below − 1.96 signifies cold spot (low internet use clustering, while a z-score above + 1.96 identifies a hotspot (high internet use clustering) [34].

Spatial interpolations

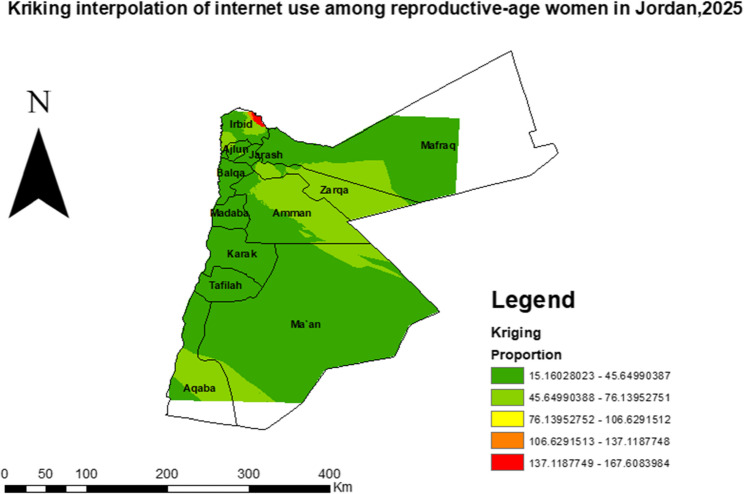

The Internet penetration in unsampled areas was predicted using the Ordinary kriging spatial interpolation approach, which was based on the values found in sampled areas. Different geostatistical and deterministic interpolation techniques exist [35]. The ordinary kriging interpolation approach was the greatest fit for mapping Internet use since it had the lowest Mean Predicted Error (MPE) and root mean square error, suggesting that predicted and observed values were nearly identical [36]. The spherical variogram model was chosen due to its ability to represent gradual spatial correlation in Internet usage patterns [37]. The model effectively captured the spatial structure of the data, with a nugget of 10, a sill of 50, and a range of 300 m. These parameters helped predict Internet usage in unsampled regions, with higher usage represented in red areas and lower usage in blue areas (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Ordinary kriging interpolation of internet use among reproductive age women in Jordan 2023 DHS

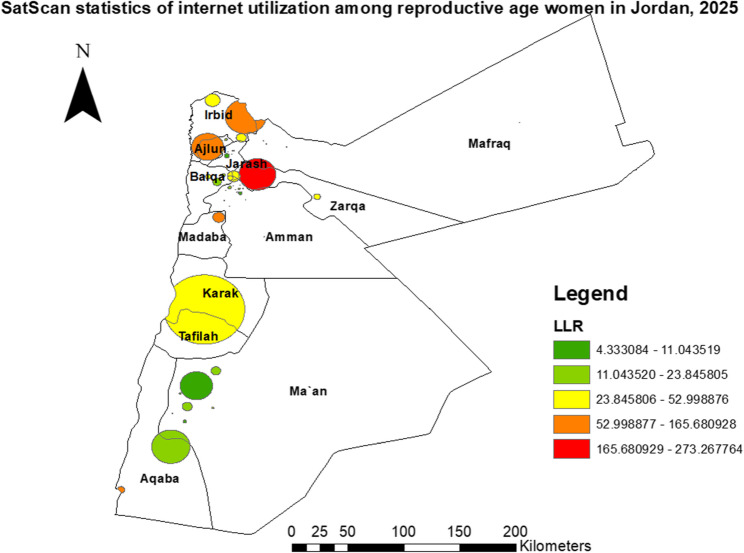

Spatial scan statistics

SatScan version 10.1 software was utilized to identify the community locations of the statistically important spatial windows for Internet use utilizing Bernoulli-based model spatial Kuldorff’s Scan statistics [38]. Bernoulli’s model uses a moving scan window to detect clusters, with Internet users acting as cases and non-users as controls. Small and large clusters are discovered, but those that surpass the maximum size are ignored. Areas with a significant p-value and a high Log Likelihood Ratio have higher Internet usage than regions outside the window.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

A total of 42,962 weighted samples of reproductive-age women were participated in this study. The overall mean of women was 38.24 ± 7.31, with the age range 35–49 years constituting the larger group 29,686 (69.09%). Almost, 36,832 (89.74%) of participants were attained secondary and above education. Most of study participants were from Amman region 6685 (15.56%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Individual level characteristics of internet use among reproductive age women in ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Category | Weighted frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | Rural | 7385 | 17.19 |

| Urban | 35,577 | 82.81 | |

| Respondent education | Non educated | 1745 | 4.06 |

| Primary | 4385 | 10.20 | |

| Secondary and above | 36,832 | 89.74 | |

| Respondent occupation | No working | 5102 | 11.86 |

| Working | 37,860 | 88.14 | |

| Respondent age | 15–24 | 1672 | 3.89 |

| 25–34 | 11,604 | 27.02 | |

| 35–49 | 29,686 | 69.09 | |

| Marital status | Widowed | 1383 | 3.23 |

| Divorced | 881 | 2.05 | |

| Married | 40,698 | 94.72 | |

| Own a mobile telephone | No | 2819 | 6.56 |

| No | 40,143 | 93.44 | |

| Region | Amman | 6685 | 15.56 |

| Balqa | 2853 | 6.64 | |

| Zarqa | 2368 | 13.55 | |

| Madaba | 2368 | 5.51 | |

| Irbid | 5596 | 13.03 | |

| Mafraq | 4217 | 9.82 | |

| Jarash | 3362 | 7.83 | |

| Ajloun | 2834 | 6.60 | |

| Karak | 2297 | 5.35 | |

| Tafiela | 2544 | 5.92 | |

| Aqaba | 2242 | 5.22 | |

| ma’an | 2143 | 4.99 | |

| Wealth Status | Poor | 23,409 | 54.49 |

| Middle | 7998 | 18.62 | |

| Rich | 11,555 | 26.90 | |

| Frequency of reading news paper | Yes | 8976 | 20.89 |

| No | 33,986 | 79.11 | |

| Frequency of listening radio | Yes | 11,427 | 26.60 |

| No | 31,535 | 73.40 | |

| Frequency of watching television | No | 7273 | 16.93 |

| Yes | 35,689 | 83.07 |

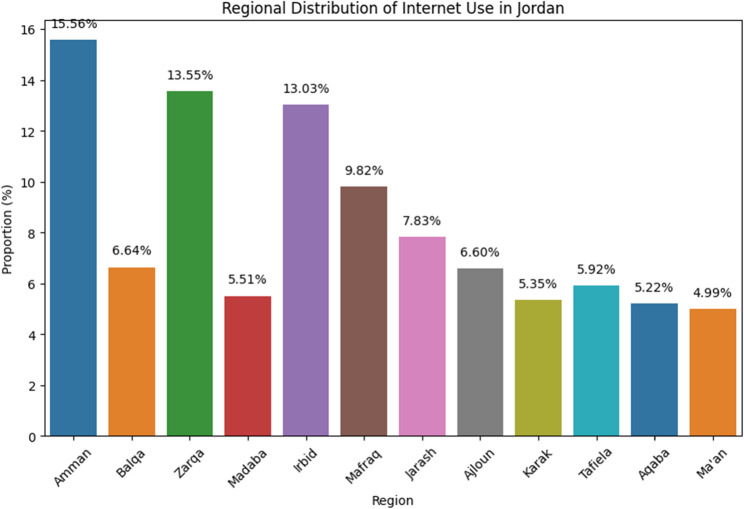

Proportion of internet of by region in Jordan

The proportion of internet use varies across region. The highest proportion of internet use was observed in Amman 6685 (15. 56%).On the other hand, the lowest proportion of internet use, Ma’an 2143 (4.99%) (Fig. 2). In this study, a total of 34,519 (80.37%) ± (95% CI 79.99–80.75) women used the internet to obtain healthcare information.

Fig. 2.

Spatial variation of internet use across region in Jordan 2023 DHS

Multilevel analysis

Multilevel mixed-effects regression was used to compute four different models: the null model, the model with individual-level variables, the model with community-level variables, and the final model, which included both individual-and community-level factors. Mixed effect model was the best model for the data since it had the lowest deviation and the highest log likelihood. The random intercepts and the fixed effects for the use of internet are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Individual and community level factors associated with internet use among reproductive age women in Jordan 2023 DHS

| Characteristics | Category | Model I (AOR with 95%) | Model II (AOR with 95%) | Model III (AOR with 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent education | Non educated | Ref | - | Ref |

| Primary | 4.94(3.77,5.84)* | - | 4.65(3.74,5.78)* | |

| Secondary and above | 9.07(7.42,11.08)* | - | 8.99(7.36,10.99)* | |

| Respondent occupation | No working | Ref | - | Ref |

| Working | 1.89(1.611,2.00)* | - | 1.86(1.67,2.08)* | |

| Respondent age | 15–24 | Ref | - | Ref |

| 25–34 | 0.74(0.609,0.89)* | - | 0.72(0.5,0.87)* | |

| 35–49 | 0.79(0.66,0.95)* | - | 0.78(0.64,0.94)* | |

| Wealth Status | Poor | Ref | - | Ref |

| Middle | 1.68(1.53,1.85)* | - | 1.65(1.50,1.81)* | |

| Rich | 1.56(1.43,1.72)* | - | 1.55(1.41,1.70)* | |

| Marital status | Widowed | Ref | - | Ref |

| Divorced | 0.62(0.47,0.80)* | - | 0.62(0.47,0.80)* | |

| Married | 0.99(0.82,1.21) | - | 1.00(0.82,1.21) | |

| Has personal electronic wallet | No | Ref | - | Ref |

| Yes | 1.57(1.39,1.77)* | - | 1.60(1.41,1.80)* | |

| Own a mobile telephone | No | Ref | - | Ref |

| Yes | 33.10(28.21,38.84)* | - | 33.34(28.41,39.12)* | |

| Region | Amman | - | Ref | Ref |

| Balqa | - | 1.17(0.72,1.92) | 1.30(0.80,2.10) | |

| Zarqa | - | 4.31(2.70,6.90)* | 7.86(4.82,12.22)* | |

| Madaba | - | 4.66(2.56,8.50)* | 5.68(3.09,10.41)* | |

| Irbid | - | 2.96(1.88,4.66)* | 3.15(2.03,4.91)* | |

| Mafraq | - | 0.43(0.27,0.69)* | 0.66(0.42,1.05) | |

| Jarash | - | 1.51(0.89,2.54) | 1.75(1.05,2.92)* | |

| Ajloun | - | 3.30(1.86,5.85)* | 3.23(1.83,5.69)* | |

| Karak | - | 2.26(1.30,3.93)* | 2.87(1.67,4.93)* | |

| Tafiela | - | 2.34(1.27,4.28)* | 2.44(1.33,4.49)* | |

| Aqaba | - | 0.77(0.43,1.37) | 0.89(0.51,1.57) | |

| ma’an | - | 3.35(1.81,6.19)* | 4.11(2.21,7.62)* | |

| Community media | No | - | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | - | 0.75(0.68,0.82)* | 0.70(0.64,0.76)* | |

| Place of residence | Urban | - | Ref | - |

| Rural | - | 0.82(0.59,1.12) | - |

*p-value < 0.05

The random effect (measure of variation) results in multilevel analysis

The ICC value in the null model was 26.4%, suggesting that 26.4% of the total variation in internet use was attributable to the between-group variation, while the individual-level difference accounted for the remaining 39.05%. The median odds ratio also indicated that internet usage among reproductive- age women was varied across clusters. The MOR was 4.52 implying that women in the cluster with higher Internet usage had 4.52 times higher odds of using the Internet than women in the cluster with lower Internet use assuming two women were randomly selected from different clusters (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measure of variation and model fit statistics in internet use among reproductive age women in ethiopia, 2023

| Parameter | Null model | Model I | Model II | Model III | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance | 3.119707 | 2.956731 | 2.531037 | 2.34551 | |

| MOR | 4.52 | 4.09 | 4.17 | 3.57 | |

| ICC | 0.264 | 0.4733 | 0.4348 | 0.4167 | |

| PCV | 5.22% | 15.5% | 18.89% | 21.82% | |

| Model Fitness | |||||

| LLR | −16414.93 | −14297.376 | −16343.095 | −14221.454 | |

| Deviance | 32829.86 | 28594.75 | 32686.19 | 28442.91 | |

ICC Inter Cluster Correlation, MOR Median Odd Ratio, PCV Proportional Change in Variance

In Model I, only individual-level variables were added. The results that women’s age, marital status, wealth index, own mobile phone, has personal electronic wallet, and women’s occupation were associated with internet use. According to ICC in Model I, variations in women’s Internet use between communities explained 47.33% of the variation. In regards to the PCV, individual-level factors explained 15.5% of the variation in Internet use across communities.

In Model II, only community-level variables were incorporated, and results demonstrated that community media and region factors were significantly linked to the use of the internet. The ICC in Model II indicated that about 43.48% of the variation in women’s Internet usage was attributable to disparities between localities. Furthermore, the PCV indicated that 18.89% of the variation in internet use between communities was accounted for by community-level characteristics.

After integrating both individual and community-level variables into model III, the disparity in the likelihood of Internet use between communities remained to be statistically significant. Based on the estimated ICC, community differences accounted for 41.46% of the difference in Internet use. According to the PCV, model III’s individual and community-level characteristics accounted for 21.82% of the variation in Internet use among communities (Table 2).

Fixed effect result in a multilevel analysis

The final model (Model IV) in the multivariable multivariable multilevel mixed-effects regression analysis incorporated both individual and community-level factors. Significant determinants of Internet use include Women’s education, occupation, age, wealth status, marital status, possession of a personal electronic wallet, ownership of a mobile phone and region. The odds of women who accomplished secondary and above education and primary education were 8.99 times [AOR = 8.99;95% CI (7.36,10.99)] and 4.65 times [AOR = 4.65; 95% CI (3.74,5.78)] more likely to use the internet for health related purpose respectively, than women who non educated. Working women were 1.86 times [AOR = 1.86; 95% CI (1.67,2.08)] more likely to use the internet for health than not working women. Individuals aged 25–34 were 0.72 times less likely [AOR = 0.72; 95% CI (0.50, 0.87)] to use the internet compared to 15–24 aged women. Similarly, those aged 35–49 were 0.78 times less likely [AOR = 0.78; 95% CI (0.64, 0.94)] to use the internet.

Women from middle and rich sized households were 1.65 times [AOR = 1.65; 95% CI (1.50,1.81)] and 1.55 times [AOR = 1.55; 95% CI (1.41,1.70) more likely to use the internet for health, respectively, than women from poorer households. Women has persona electronic wallet were 1.60 times [AOR = 1.60; 95% CI (1.41,1.80)] more likely to use the internet for medical purpose than women without electronic wallet. Women with mobile phones were 33.34 time [AOR = 33.34; 95% CI 28.41,39.12) more likely to use the internet for health purpose than women without mobile phone.

Among community based variables, the odds of women Zarqa were in 7.86 times [AOR = 7.86;95% CI (4.82,12.22)], and those in Madaba were 5.68 times [AOR = 5.68; 95% CI 3.09,10.41)] more likely to use the internet than women in the Amman. The odds of women in Ma’an were 4.11 times [AOR = 4.11; 95% CI (2.21,7.62)] and those in Irbid were 3.15 times [AOR = 3.15; 95% CI (2.03,4.91)] more likely to use the internet than women in the Amman (Table 3).

Spatial analysis

Spatial autocorrelation

The findings showed that among Jordanian women of reproductive age, Internet use was not distributed randomly. There was a positive skew to the right in the distribution. The result of the Global Moran’s I test was 0.08 with a p-value that was very significant (p < 0.001). According to the substantial Global Moran’s I, which was more than zero, the spatial variations of Internet use showed a clustered pattern. This implies that the likelihood of this pattern occurring by chance is less than 1% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Spatial autocorrelation of internet use among reproductive age women in Jordan 2023 DHS

Getis Ord gi* hotspot analysis

The statistical study of Getis-Ord Gi* showed a significant geographical clustering of Internet use hotspots and cold spots. A higher Z-score is an indicator of a stronger clustering. No distinct clustering is shown when the Z-score is near zero; high-value clusters are indicated by positive Z-scores, whilst low-value clusters are indicated by negative Z-scores. The red color indicates hotspot areas with Z scores > 0 (3.646762–4.843822), and the blue color indicates cold spots with Z scores < 0 (−5.363587- −0.513502). Based on Getis ord Gi* hotspot statistical analysis, significant hotspots of internet use were found in Irbid, Ajilun, Jarash, Zarak, and Mafrak and a few place in Balqa (Dier Alla Zone). However, statistically cold spots of internet use were found in most parts of the Karak, Tafilah, and some parts of Ma’ an and Aqaba region of joradan (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Hotspot analysis of internet use among reproductive age women in Jordan 2023 DHS

Spatial interpolation

The distance from known places was calculated using the standard kriging interpolation approach in order to estimate values at unknown points or areas. By presenting points inside event occurrence ranges, this method was utilized to determine the proportion of Internet usage in unsampled areas. Regular kriging analysis predicts that Internet usage will rise and move from blue to red areas. A higher percentage of predicted Internet use is represented by the red spots, whilst a smaller portion is shown by the blue areas (Fig. 5). Irbid (137–167) were predicted to be the most prevalent areas for internet use women compared to other regions.

Satscan statistics

Through the use of the Bernoulli model and pure spatial analysis, we were able identify specific local clusters that are required for specific local interventions. One primary and 31 secondary (a total of 32) were significant (p < 0.05) and internet use clusters were indicated. In total 50 location found in the cluster. The spatial window was placed at 32.082657 N, 36.096772 E)/with a 13.98 km radius, with a relative likelihood of 1.18 and LLR of 273.26, at p value < 0. 0001 (Table 4). The cluster was located in the Irbid region (Fig. 6). This means that those lived in these areas were 11.18 times more exposed to internet use than those outside of these clusters.

Table 4.

Most likely clusters of purely Spatial analysis of internet use among reproductive age women in Jordan 2023 DHS

| Cluster | EA Identified | Coordinate/Radius | Population | Cases | RR | LLR | P-Value | Region (Location) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary | (32.0827, 36.0968)/13.98 km | 3,907 | 3,638 | 1.18 | 273.27 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 2 | Secondary | (32.5478, 36.0019)/15.44 km | 3,571 | 3,251 | 1.15 | 165.68 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 3 | Secondary | (31.7381, 35.7863)/4.53 km | 1,616 | 1,529 | 1.19 | 140.91 | < 0.001 | Karak |

| 4 | Secondary | (32.3032, 35.6961)/12.11 km | 2,747 | 2,484 | 1.13 | 109.86 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 5 | Secondary | (29.5504, 35.0004)/2.89 km | 1,542 | 1,428 | 1.16 | 93.70 | < 0.001 | Aqaba |

| 6 | Secondary | (30.9973, 35.6713)/30.91 km | 3,501 | 3,036 | 1.09 | 52.99 | < 0.001 | Ma’an |

| 7 | Secondary | (31.9041, 36.5773)/2.51 km | 1,077 | 983 | 1.14 | 49.85 | < 0.001 | Zarqa |

| 8 | Secondary | (32.6786, 35.7360)/5.65 km | 240 | 237 | 1.23 | 40.68 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 9 | Secondary | (32.0537, 35.8803)/2.09 km | 204 | 203 | 1.24 | 39.77 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 10 | Secondary | (32.3762, 35.9673)/3.81 km | 258 | 251 | 1.21 | 34.22 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 11 | Secondary | (32.2724, 35.9026)/0.62 km | 136 | 136 | 1.25 | 29.76 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 12 | Secondary | (32.0668, 35.9066)/4.86 km | 323 | 306 | 1.18 | 28.09 | < 0.001 | Irbid |

| 13 | Secondary | (30.206590, 35.737399)/0.82 km | 213 | 207 | 1.21 | 27.75 | 0.0000000064 | Ma’an |

| 14 | Secondary | (32.076046, 35.823738)/1.41 km | 184 | 180 | 1.22 | 26.64 | 0.000000017 | Irbid |

| 15 | Secondary | (32.063573, 35.701357)/2.10 km | 120 | 120 | 1.25 | 26.26 | 0.000000024 | Irbid |

| 16 | Secondary | (32.362305, 35.844335)/1.02 km | 109 | 109 | 1.24 | 23.85 | 0.00000020 | Irbid |

| 17 | Secondary | (30.218507, 35.532222)/3.82 km | 138 | 135 | 1.22 | 19.97 | 0.0000064 | Ma’an |

| 18 | Secondary | (31.872966, 35.828711)/0 km | 90 | 90 | 1.24 | 19.68 | 0.0000082 | Karak |

| 19 | Secondary | (31.968459, 35.949903)/0.73 km | 145 | 141 | 1.21 | 19.05 | 0.000014 | Karak |

| 20 | Secondary | (29.895628, 35.400804)/14.86 km | 184 | 176 | 1.19 | 18.63 | 0.000021 | Aqaba |

| 21 | Secondary | (31.827169, 35.872213)/0 km | 73 | 73 | 1.24 | 15.96 | 0.00022 | Karak |

| 22 | Secondary | (32.243840, 35.889457)/0 km | 70 | 70 | 1.24 | 15.31 | 0.00040 | Irbid |

| 23 | Secondary | (31.978075, 35.873769)/1.30 km | 70 | 70 | 1.24 | 15.31 | 0.00040 | Karak |

| 24 | Secondary | (32.022295, 35.773526)/3.27 km | 179 | 169 | 1.18 | 14.69 | 0.00068 | Irbid |

| 25 | Secondary | (31.995932, 35.956386)/0 km | 65 | 65 | 1.24 | 14.21 | 0.0010 | Karak |

| 26 | Secondary | (32.263444, 35.860880)/0 km | 59 | 59 | 1.24 | 12.90 | 0.0033 | Irbid |

| 27 | Secondary | (31.940451, 35.930921)/0 km | 56 | 56 | 1.24 | 12.24 | 0.0059 | Amman |

| 28 | Secondary | (31.878656, 36.001801)/0 km | 55 | 55 | 1.24 | 12.02 | 0.0072 | Zarqa |

| 29 | Secondary | (30.505174, 35.763312)/3.68 km | 55 | 55 | 1.24 | 12.02 | 0.0072 | Ma’an |

| 30 | Secondary | (32.231057, 35.851309)/1.92 km | 121 | 115 | 1.18 | 11.04 | 0.018 | Irbid |

| 31 | Secondary | (30.384565, 35.606125)/12.54 km | 188 | 174 | 1.15 | 11.02 | 0.018 | Ma’an |

| 32 | Secondary | (30.096630, 35.513068)/1.38 km | 49 | 49 | 1.24 | 10.71 | 0.025 | Ma’an |

Fig. 6.

purely spatial analysis of internet use among reproductive age women in Jordan 2023 DHS

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the spatial distribution and determinants of internet utilization among reproductive age women in Jordan. It was founded on an analysis of secondary data from the nationally representative study JPFHS 2023.The spatial analysis finding showed that the spatial distribution of internet utilization among women age 15–49 significantly varied across the country. In multilevel mixed effect analysis women’s education, women’s occupation, women’s age, wealth status, community media, marital status, has personal electronic wallet, own mobile telephone, and region were significant predictors of internet use.

The magnitude of women in reproductive age who used the Internet to look for information related to health was 80.37%. This result implies that women’s internet usage to access health information is relatively good internet access. This result is significantly less than the nation’s current rapid adoption and use of information technology. According to other investigations conducted within Asia and developed nations, this result is likewise lower. Internet use to access medical information among reproductive age women in China (88.7%) [39], Sweden (84%) [40], Austria (98.0%) [41], Belgium (85.9%) [42] and Australia (91.9%) [43].The possible reason for the difference might be due to technological accessibility and socioeconomic growth in these nations. Additionally, it could be due to access to infrastructure linked to digital technology and national policies related to internet development strategy contributing to the discrepancy by enabling women to make use of internet to acquire health related information in developed and developing country. This might be related to difference in infrastructure, awareness level in these countries.

This finding indicated that the age of women has significant influence in the use of internet on for health related purpose. Women aged 35–49 years were 78% less likely [AOR = 0.78; 95% CI (0.64,0.94)] to use the internet for well-being than women aged 15–24 years. This was supported by previous studies in USA [13] and the Saudi Arabia [19]. It could be because younger women might have put greater value on the external benefits of using technology. They see the value of using technology and have a strong desire to accomplish effectively. Additionally, since young women do not have large families, they may be less burdened with working and financial obligations to meet basic necessities, which may lead to a rise in the use of the Internet to learn about their health [44]. Similarly, it was supported by studies from Japan [45]. Internet use for health has a strong association with age. The Internet utilization of women decreases with age, with those between the ages of 15 and 24 using it more frequently than those between the ages of 40 and 49.

The finding of this study also indicated that women’s education has a positive significant relationship internet use. Women with secondary and above were 8.99 times [(AOR = 8.99; 95% CI (7.36,10.99)] more likely to use the internet for health purpose than those without education. This result is similar with studies done in UK [16], Columbia [17] and Iran [46]. The reason for this could be that educated women are more likely to look up up-to-date high-quality health information online and are more confident and capable of taking action to improve their own and the health of others. This could also include educated women who are able to utilize the Internet, search for information, read content, truly understand context, and be familiar with the service subject area [47].

The marital status of women was significantly associated with on the use of the internet for heath information. Divorced women were 62% less likely [AOR = 0.62; 95% CI (0.47,0.80)] to use the internet for health than widowed women. This is supported by research done in USA [48]. This finding indicates that divorced women are less likely to use the internet for health related purpose compared to widowed women. This is might be that differences in internet availability and the varying effects of social isolation and life transitions on internet use result in the reduced likelihood of divorced women searching the internet for health information when compared to widowed women [49, 50]. However, some research does not find marital status to be a significant predictor. A study conduced in Taiwan, Germany [51], and US [52] marital status were not significantly associated with internet utilization among reproductive age women. The reason might be ounger unmarried women might be more tech-savvy, while older married women could rely on spouses for health decisions, reducing their need for online searches [53].

Studies suggest that the wealth status of respondents has a significant on the use of internet for health purpose. The likelihood of internet sue among reproductive age women from rich and middle-sized households was higher than that among women from poor households. Women from rich households were 1.55 times [(AOR = 1.55; 95% CI (1.41,1.70)] and women from middle-income households were 1.65 times [(AOR = 1.65; 95% CI (1.50,1.81)] morel likely to use the internet than women from poor households. This finding is supported by studies conducted in Iran [46], France [54], China [55]. This could be that wealthy households likely to have higher incomes, and having access to the Internet and having internet at home might increase the likelihood that women of reproductive age will use the Internet for health-related objectives more frequently.

Another finding of this study, women occupation was positively associated with internet use for health purpose. Women who has work were 1.86 times [AOR = 1.86; 95% CI (1.67,2.08)] more likely to use the internet than those without work. This is supported by studies evidence in Japan [56] and the Malaysia [57]. A possible reason could be that women in the workforce are more likely to be exposed to digital resources, have better access to the internet at work, and possess higher levels of computer proficiency [58].

According to this finding, mobile possession was significantly associated with interne use for health purposes. Women who had a mobile phone were 33.34 times [(AOR = 33.34;95% CI (28.41,39.12)] more likely to use the internet than those did not have mobile phones. It reflects Mobile phone ownership aligns with digital divide showing near-essential status of devices for internet access in LMICs [59]. This finding was supported by evidence from Japan [60] and Columbia [61]. This might be as there are currently a variety of readily accessible technologies that make using the Internet easier. Owning a mobile phone allows you to easily and affordably access Wi-Fi Internet anywhere it’s offered [62].

Personal electronic wallet was a significant determinants of internet use for health information. Women who had personal electronic wallet were 1.60 times [(AOR = 1.60; 95% CI (1.41,1.80)] more likely to use the internet than those did not have personal electronic wallet. This finding is supported by evidence in Korean [63]. This suggests that by simplifying online transactions, lowering financial obstacles, or improving digital engagement, owning a personal electronic wallet may make it easier to use the internet [64].

Finally, the analysis showed that Zarak and Madaba regions were positively associated with internet use for health purposes. Respondents who lived in Zarka 7.86 times [AOR = 7.86; 95% CI (4.82,12.22)] and Madaba 5.68 times [AOR = 5.68; 95% CI (3.09,10.41)] more likely to use the internet than those in the Amman region. This finding is supported the research done in Jordan [65, 66] and USA [67]. This might be associated with the fact that city administrations have better internet access infrastructure, more educated respondents, and a better community than other areas.

Across the nation, there were significant variations in spatial distribution of Internet use for healthcare related purposes. Interventions might be based on the variation in Internet use, which indicated clustering in some regions of the nation. To the right of the curve (skewed to the right), the global Moran’s I result was positive. The significant positive Moran’s I was 0.08 and with a significant p-value (p < 0.001) indicating that there was statistically significant clustering (nonrandom) of internet users in the country. This indicates that the probability of the clustered pattern being the product of random chance is less than 1%.

The Getis Ord Gi* statistical analysis showed the significant spatial clustering of high values (hotspots) and significant clustering of low values (cold spots) of internet use. The clustering’s intensity strengthens with an increase in Z score based on the Getis-Ord Gi* statistical analysis finding.

Based on Getis ord Gi* hotspot statistical analysis, significant hotspots (Z > 0) of internet use were found in Irbid, Ajilun, Jarash, Zarak, and Mafrak and a few place in Balqa (Dier Alla Zone). However, statistically cold spots (z < 0) of internet use were found in most parts of the Karak, Tafilah, and some parts of Ma’ an and Aqaba region of joradan.

Purely spatial scan statistical analysis indicated the circled significant areas of Irbid and Jarash region. This finding was supported by a study conducted in the Turkey [68] and Europe [69]. This might be the result of regional variations in infrastructural availability as well as sociocultural and socioeconomic disparities among women. Furthermore, the disparity in women’s awareness and attitudes regarding the advantages of obtaining health and health-related information online may also contribute to the geographic diversity in Internet use [1, 70]. Furthermore, the significant geographical differences in media exposure and levels of education may help to explain these discrepancies.

Implication of the study

This study reveals significant socioeconomic and regional differences in Jordanian women of reproductive age’s use of the internet for health-related objectives. Public health outcomes can be improved and access to digital health can be expanded by addressing these gaps through focused policies and actions.

The necessity for region-specific digital health strategies is indicated by the spatial clustering of internet use. The digital divide can be closed by growing digital literacy initiatives and internet infrastructure in underprivileged communities. Online platforms should be used in public health campaigns to guarantee that everyone has access to health information.

Internet use is significantly influenced by socioeconomic characteristics, such as wealth position, work, and education. Targeted digital literacy programs and easier access to affordable internet services are necessary for women from lower-income and less educated backgrounds. Internet use is also influenced by age and marital status; younger women use the internet more often than older women. Divorced and older women should be encouraged to use digital health services through tailored interventions. Furthermore, hotspot areas can be used to expand telehealth, whereas cold spot areas require awareness campaigns and infrastructure upgrades.

Strength and limitations of the study

The most crucial aspect of the study was the identification of certain statistically significant Internet use hotspots and cold spot areas through the use of advanced methods like spatial analyses. The interpretation is predicated on the following limitations, which this study acknowledged. A cause-and-effect link between result and predictor variables cannot be established because the survey is cross-sectional. Only circular clusters were identified by the SaTScan analysis; clusters with irregular shaped were not detected.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the magnitude of internet use for health related purpose among reproductive-age women is 80.07%. women’s education, women’s occupation, women’s age, wealth status, marital status, has personal electronic wallet, own mobile telephone, and region were significant predictors of internet use. Therefore, improving women’s education, media exposure, encourage them to use mobile phone and personal electronic wallet, and empowering household wealth could improve internet usage to obtain right health information.

Acknowledgements

The measure DHS program provided the data sets used in this study, and we are appreciative that they allowed us to acquire the dataset from their website.

Abbreviations

- AIC

Akaike’s Information Criterion

- AOR

Adjusted Odd Ratio

- CSA

Central Statistical Agency

- CV

Community Variance

- DHS

Demographic Health Survey

- EA

Enumeration Areas

- JPFHS

Jordan Population and Family Health Survey

- ICC

Intracluster Correlation Coefficient

- IR

Individual Record

- MOR

Median Odd Ratio

- PCV

Proportional Change in Variance

Authors’ contributions

JMK was accountable for making significant contributions to the study selection, data collection, funding acquisition, formal analysis, conceptualization, investigation, methodology, and original draft preparation. Project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, and reviewing are all handled by JMK, ADG, ASA, BGM, BNB, SAA, WDN, KTT, DSA, final draft of the manuscript, and the final draft of the work was read, edited, and approved by all the writers.

Data availability

The official database of the DHS program contains the dataset that was utilized and examined in this investigation upon formal request. An email is usually sent to confirm approval for access to the dataset.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The JDHS data was used, publicly available on the DHS website [28]. The International Review Board of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) program data archivists waived informed consent after the consent paper was submitted to the DHS program, and a letter of authorization was obtained to download the dataset for this investigation. We made a serious commitment to following all DHS approval requirements. The study’s methodology is accessible with registration and a valid request, and it conforms with relevant criteria. This study was conducted according to the Helsinki. Declaration..

Consent for publication

The publishing consent was not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Meshesha NA, Atnafu DD, Hussien M, Tizie SB, Dube GN, Bitacha GK. Internet use, Spatial variation and its determinants among reproductive age women in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mouha RARA. Internet of things (IoT). J Data Anal Inform Process. 2021;9(02):77. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serafino P. Exploring the uk’s digital divide. Office Natl Stat. 2019;2019:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradshaw AC. Internet users worldwide. Education Tech Research Dev. 2001:111–7.

- 5.Panichsombat R. Impact of internet penetration on income inequality in developing asia: an econometric analysis. ASR: CMU J Social Sci Humanit. 2016;3(2):151–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alshuaibi AS, Mohd Shamsudin F, Alshuaibi MSI. Internet misuse at work in Jordan: Challenges and implications. 2015.

- 7.Ningsih C, Choi Y-J. An effect of internet penetration on income inequality in Southeast Asian countries. 2018.

- 8.Layton R, Jitsuzumi T, Cho D-K. Broadband Network Usage Fees: Empirical and Theoretical Analysis Versus Observed Broadband Investment and Content Development. Insight from Korea and the Rest of the World. Insight from Korea and the Rest of the WorldAugust 6, (2024). 2024.

- 9.Zheng H, Ma W, Rahut D. How the internet is revolutionizing sustainable agriculture in Asia. 2024.

- 10.Larsson M. A descriptive study of the use of the internet by women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery. 2009;25(1):14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Master A, Garman C. A worldwide view of nation-state internet censorship. Free and Open Communications on the Internet; 2023.

- 12.Balhara YPS, Mahapatra A, Sharma P, Bhargava R. Problematic internet use among students in South-East asia: current state of evidence. Indian J Public Health. 2018;62(3):197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Din HN, McDaniels-Davidson C, Nodora J, Madanat H. Profiles of a health information–seeking population and the current digital divide: cross-sectional analysis of the 2015–2016 California health interview survey. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(5):e11931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balhara YPS, Doric A, Stevanovic D, Knez R, Singh S, Chowdhury MRR, et al. Correlates of problematic internet use among college and university students in eight countries: an international cross-sectional study. Asian J Psychiatry. 2019;45:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chia DX, Ng CW, Kandasami G, Seow MY, Choo CC, Chew PK, et al. Prevalence of internet addiction and gaming disorders in Southeast asia: A meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruse RL, Koopman RJ, Wakefield BJ, Wakefield DS, Keplinger LE, Canfield SM, et al. Internet use by primary care patients: where is the digital divide? Fam Med. 2012;44(5):342–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albright JM. Sex in America online: an exploration of sex, marital status, and sexual identity in internet sex seeking and its impacts. J Sex Res. 2008;45(2):175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinpeng A. Digital media, political authoritarianism, and internet controls in Southeast Asia. Media Cult Soc. 2020;42(1):25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alduraywish SA, Altamimi LA, Aldhuwayhi RA, AlZamil LR, Alzeghayer LY, Alsaleh FS, et al. Sources of health information and their impacts on medical knowledge perception among the Saudi Arabian population: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(3):e14414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jadoon NA, Zahid MF, Mansoorulhaq H, Ullah S, Jadoon BA, Raza A, et al. Evaluation of internet access and utilization by medical students in lahore, Pakistan. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2011;11:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen JD, King AJ, Davis LA, Guntzviller LM. Utilization of internet technology by low-income adults: the role of health literacy, health numeracy, and computer assistance. J Aging Health. 2010;22(6):804–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez JAR, Tanpoco M. Continuance intention of mobile wallet usage in the philippines: A mediation analysis. Rev Integr Bus Econ Res. 2023;12(3):128–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robru K, Setthasuravich P, Pukdeewut A, Wetchakama S, editors. Internet use for health-related purposes among older people in thailand: an analysis of nationwide cross-sectional data. Informatics: MDPI; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickard A, Islam MI, Ahmed MS, Martiniuk A. Role of internet use, mobile phone, media exposure and domestic migration on reproductive health service use in Bangladeshi married adolescents and young women. PLOS Global Public Health. 2024;4(3):e0002518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khader Y, Al Nsour M, Abu Khudair S, Saad R, Tarawneh MR, Lami F, editors. Strengthening primary healthcare in Jordan for achieving universal health coverage: a need for family health team approach. Healthcare: MDPI; 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bank W. Gender data portal. 2023.

- 27.Worldometer. Jordan Population 2025.

- 28.DoSDJa ICF, Amman J, Rockville. Maryland, USA: DoS and ICF. Jordan Population and Family and Health Survey 2023.

- 29.Austin PC, Merlo J. Intermediate and advanced topics in multilevel logistic regression analysis. Stat Med. 2017;36(20):3257–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gulliford M, Adams G, Ukoumunne O, Latinovic R, Chinn S, Campbell M. Intraclass correlation coefficient and outcome prevalence are associated in clustered binary data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(3):246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salahuddin M, Tisdell C, Burton L, Alam K. Does internet stimulate the accumulation of social capital? A macro-perspective from Australia. Econ Anal Policy. 2016;49:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Negash WD, Belachew TB, Asmamaw DB, Bitew DA. Four in ten married women demands satisfied by modern contraceptives in high fertility sub-Saharan Africa countries: a multilevel analysis of demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Songchitruksa P, Zeng X. Getis–Ord Spatial statistics to identify hot spots by using incident management data. Transp Res Rec. 2010;2165(1):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krivoruchko K. Empirical bayesian kriging. ArcUser Fall. 2012;6(10):1145. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gia Pham T, Kappas M, Van Huynh C, Hoang Khanh Nguyen L. Application of ordinary kriging and regression kriging method for soil properties mapping in hilly region of central Vietnam. ISPRS Int J Geo-Information. 2019;8(3):147. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulldorff M. A Spatial scan statistic. Commun Statistics-Theory Methods. 1997;26(6):1481–96. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L, Gao Y, Zhu D, Yuan Y, Liu Y. Quantifying the scale effect in Geospatial big data using semi-variograms. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0225139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tegegne KT, Tegegne ET, Tessema MK, Wudu TK, Abebe MT, Workaeh AZ. Spatial distribution and determinant factors of anemia among women age 15–49 years in Burkina faso; using mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression model. J Prev Med Hyg. 2024;65(2):E203–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Javanmardi M, Noroozi M, Mostafavi F, Ashrafi-rizi H. Internet usage among pregnant women for seeking health information: A review Article. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2018;23(2):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornelius JB, Whitaker-Brown C, Neely T, Kennedy A, Okoro F. Mobile phone, social media usage, and perceptions of delivering a social media safer sex intervention for adolescents: results from two countries. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2019;10(null):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haluza D, Böhm I. The quantified woman: exploring perceptions on health app use among Austrian females of reproductive age. Reproductive Med. 2020;1(2):10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanssens D, Thijs IM, Dreesen P, Van Hecke A, Coorevits P, Gaethofs G, et al. Information resources among Flemish pregnant women: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(10):e37866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sayakhot P, Carolan-Olah M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumann E, Czerwinski F, Reifegerste D. Gender-specific determinants and patterns of online health information seeking: results from a representative German health survey. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(4):e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitsutake S, Takahashi Y, Otsuki A, Umezawa J, Yaguchi-Saito A, Saito J, et al. Chronic diseases and sociodemographic characteristics associated with online health information seeking and using social networking sites: nationally representative cross-sectional survey in Japan. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e44741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rains SA. Health at high speed: broadband internet access, health communication, and the digital divide. Communication Res. 2008;35(3):283–97. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diviani N, Van Den Putte B, Giani S, van Weert JC. Low health literacy and evaluation of online health information: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lombardo S, Cosentino M. Internet use for searching information on medicines and disease: a community pharmacy–based survey among adult pharmacy customers. Interact J Med Res. 2016;5(3):e5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh GK, Girmay M, Allender M, Christine RT. Digital divide: marked disparities in computer and broadband internet use and associated health inequalities in the united States. Int J Translational Med Res Public Health. 2020;4(1):64–79. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shim H, Ailshire JA, Crimmins EM, INTERNET USE, AND SOCIAL ISOLATION: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF LIFE TRANSITIONS. Innov Aging. 2019;3(Suppl 1):S194. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bach R, Wenz A. Studying health-related internet and mobile device use using web logs and smartphone records. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0234663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sedrak MS, Soto-Perez-De-Celis E, Nelson RA, Liu J, Waring ME, Lane DS, et al. Online health information–seeking among older women with chronic illness: analysis of the women’s health initiative. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e15906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chong CY, Teh P-L, Wu S, Liew EJY, editors. Perceptions and Expectations of Women-In-Tech (WIT) Application: Insights from Older Women in Rural Areas. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; 2023: Springer.

- 54.Beck F, Richard J-B, Nguyen-Thanh V, Montagni I, Parizot I, Renahy E. Use of the internet as a health information resource among French young adults: results from a nationally representative survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(5):e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hadlington LJ. Cognitive failures in daily life: exploring the link with internet addiction and problematic mobile phone use. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;51:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sasayama K, Nishimura E, Yamaji N, Ota E, Tachimori H, Igarashi A, et al. Current use and discrepancies in the adoption of Health-Related internet of things and apps among working women in japan: Large-Scale, internet-Based, Cross-Sectional survey. JMIR Public Health Surveillance. 2024;10:e51537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahadzadeh AS, Sharif SP, Ong FS, Khong KW. Integrating health belief model and technology acceptance model: an investigation of health-related internet use. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sandborg J, Söderström E, Henriksson P, Bendtsen M, Henström M, Leppänen MH, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone app to promote healthy weight gain, diet, and physical activity during pregnancy (HealthyMoms): randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2021;9(3):e26091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar D, Hemmige V, Kallen MA, Giordano TP, Arya M. Mobile phones may not bridge the digital divide: a look at mobile phone literacy in an underserved patient population. Cureus. 2019;11(2):e4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.AlGhamdi KM, Moussa NA. Internet use by the public to search for health-related information. Int J Med Informatics. 2012;81(6):363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Russell DM. The digital expansion of the mind: Implications of Internet usage for memory and cognition. 2019.

- 62.Gashu KD, Yismaw AE, Gessesse DN, Yismaw YE. Factors associated with women’s exposure to mass media for health care information in ethiopia. A case-control study. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2021;12:100833. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chae S, Lee Y-J, Han H-R. Sources of health information, technology access, and use among non–English-speaking immigrant women: descriptive correlational study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(10):e29155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamil AM, Ali S, Poulova P, Akbar M. An ounce of prevention or a pound of cure? Multi-level modelling on the antecedents of mobile-wallet adoption and the moderating role of e-WoM during COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1002958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Alnawafleh AH, Rashad H. Does the health information system in Jordan support equity to improve health outcomes? Assessment and recommendations. Archives Public Health. 2024;82(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Obeidat B, Alourd S. Healthcare equity in focus: bridging gaps through a Spatial analysis of healthcare facilities in irbid, Jordan. Int J Equity Health. 2024;23(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alkhatlan HM, Rahman KF, Aljazzaf BH. Factors affecting seeking health-related information through the internet among patients in Kuwait. Alexandria J Med. 2018;54(4):331–6. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turan N, Kaya N, Aydın GÖ. Health problems and help seeking behavior at the internet. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2015;195:1679–82. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang H, Wang S, Zheng Y. Spatial-temporal variations and trends of internet users: assessment from global perspective. Inform Dev. 2023;39(1):136–46. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin CA, Atkin DJ, Cappotto C, Davis C, Dean J, Eisenbaum J, et al. Ethnicity, digital divides and uses of the internet for health information. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;51:216–23. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The official database of the DHS program contains the dataset that was utilized and examined in this investigation upon formal request. An email is usually sent to confirm approval for access to the dataset.