Abstract

Background

Professional identity formation (PIF) is a critical component of medical education, involving the transformation of medical students into skilled physicians. Despite its importance, there is limited research on the specific aspects of professional identity that develop during different stages of medical training.

Objectives

This study aims to identify the aspects of professional identity formation during the years medical students rotate in different medical departments and to characterize the reflective expressions that support this development.

Methods

A descriptive case-study methodology was employed, involving five medical students participating in a course designed to foster PIF. Data were collected from reflective journals and semi-structured interviews over three years. Directed content analysis was used to identify categories and subcategories of professional identity and reflective expressions.

Results

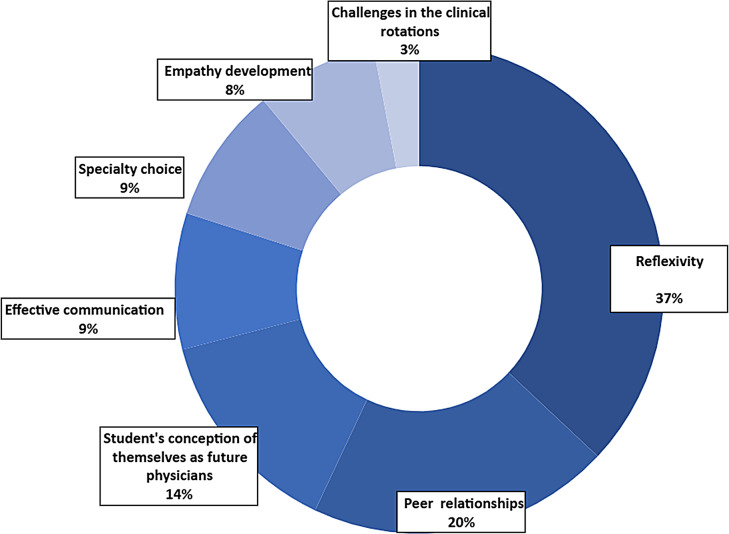

Seven main categories of professional identity were identified: Reflexivity, Peer relationships, Student’s conception of themselves as future physicians, Effective communication, Specialty choice, Empathy development, and Challenges in the clinical rotations. Reflexivity emerged as the most prominent category, with subcategories including personal emotions, clinical experience, decision-making processes, cultural beliefs, and perceptions of medical hierarchy. Reflective writing evolved over time, showing an increased ability for interpretation and critical reflections.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the existing knowledge by highlighting specific aspects of professional identity formation (PIF) as observed through the reflective expressions of medical students during their clinical rotations. The medical education community could benefit from systematically cultivating aspects of professional identity at each stage of medical studies and throughout their careers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07611-y.

Keywords: Professional identity formation (PIF), Reflective writing, Reflexivity, Medical education, Medical students, Clinical rotations

Introduction

Professional identity formation (PIF) is an ongoing longitudinal process that medical students undergo as they develop into skilled physicians, making it a crucial component of their medical education [1–3]. Despite its recognized importance in medical education, Professional Identity Formation (PIF) remains insufficiently understood, particularly regarding the specific aspects (e.g., communication skills, empathy, students’ evolving perceptions of their roles etc.) that evolve during different stages of a physician’s career. Limited research has explored which reflective expressions support this development during the clinical years [4]. Current research describes PIF as the gradual transformation of medical students into doctors, involving the incorporation of knowledge, professional values and beliefs, behaviors, and cultural influences, all shaped by individual experiences. These elements are influenced by the context of one’s medical education and career (e.g., the university attended, the stage of education and career) [2, 5–7].

The development of medical professional identity and the acquisition of relevant knowledge and skills are essential for becoming a skilled physician who can meet professional expectations and provide effective patient care [8]. Through socialization and experiential learning within supportive peer and colleague environments, physicians assimilate attributes that shape their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions in alignment with the standards of the medical profession [9–11].

One educational tool that has been shown to foster PIF is written reflections.

Reflective writing is generally characterized by depth, critical thinking, and personal insight. According to Lee’s criteria [12], reflective writing can be evaluated across three levels: descriptive (reporting events), interpretive (analyzing experiences in light of prior knowledge or values), and critical (re-examining beliefs and considering changes in perspective or behavior). Effective reflections often include emotional awareness, ethical reasoning, and the integration of professional values [13–15].

Reflective writing assists in processing clinical experiences, understanding the role of a physician, developing empathy, and drawing attention to the sociocultural aspects of healthcare [13, 16, 17]. Reflective expressions involve articulating thoughts and feelings about personal experiences, revisiting values, beliefs, thoughts, and actions, and preserving or changing perspectives, thereby enhancing PIF [14]. Identifying specific reflective expressions that highlight aspects of professional identity may lead to a better understanding of which aspects are prominent at each stage of medical students’ education [4, 18].

PIF begins with acceptance into medical school and continues throughout all stages of a physician’s career, from medical student to intern, resident, and beyond [2, 8]. Various aspects of professional identity evolve over different career stages [19]. These aspects include a sense of belonging to a professional group, emotional connections to the profession and its values, teamwork, communication, patient assessment, cultural awareness, ethical awareness, empathy, and listening [8, 20–22]. Written reflections are essential for cultivating PIF and the personal and professional growth of physicians. Through reflective writing, physicians review their thoughts, goals, and actions, understanding how their perspectives, motives, and emotions influence their behavior, thereby enhancing their learning and development [23–25].

The clinical years, during which medical students rotate through different clinical departments, hence “the clinical years”, are a critical period in medical education. During this time, students transition from theoretical learning to the practical application of their knowledge and skills [26, 27]. They are exposed to real-world medical environments, interact with patients and medical personnel, and begin to take on responsibilities as members of the medical team. The clinical years provide a rich context for meeting role models, internalizing social influences, and practicing reflective expressions (thinking, discussing, and writing), all of which, support PIF [10, 28].

A few studies have analyzed medical students’ written reflections to identify different aspects of PIF. Hatem and Halpin [29] identified three main aspects, namely performing physicians’ tasks, providing patient care, and integrating personal ideals and professional values. Sawatsky and colleagues [3] found that autonomy, decision-making, and responsibility for patients are three key themes in the formation of medical students’ professional identity. Most studies that looked into PIF relate to the process, and less so to the specific aspects of PIF. For example, Sarraf-Yazdi and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis on PIF of medical students, dividing identity formation into professional characteristics in medicine and socialization processes within the medical community [4]. Park and Hong [8] found that learning from experiences during medical school, including interactions with patients and others, enables medical students to develop their professional identities.

Despite these insights, there is still a gap in understanding which specific aspects of professional identity develop during each stage of a medical professional’s career and what reflective expressions support this development. This study seeks to bridge this gap by exploring the aspects of professional identity that develop during clinical years and identifying the reflective expressions that support this development. The findings will provide insights into the progression of PIF and inform educational frameworks for medical training. Thus, the research objectives are designed to bridge this gap.

Research objective and research questions

This study has two main aims. First, to identify aspects of professional identity that develop during the years students go through clinical rotations. Second, to characterize students’ reflective expressions that relate to PIF and their development. Therefore, our research questions are:

What are the most prominent aspects of professional identity that develop, according to medical students, during their clinical years?

What characterizes reflective expressions relating to PIF of medical students during their clinical years?

Research methodology

A descriptive case-study methodology was used in this study. Descriptive case-studies were shown to describe different characteristics of phenomena in their context, and so they are used for theory building. This method allows researchers to gain a comprehensive understanding of the research issue, enriching the problem or situation with descriptions and explanations [30]. We chose this method to expand our understanding of the aspects of students’ professional identity development and the development of their reflective expressions, as they occur in real-life context during their clinical years.

Research setting

A new mandatory course to foster PIF was launched in our medical school during 2017 for students in their clinical years (4th, 5th, and 6th years of their studies). The course operates as monthly sessions of small groups (8–10 students per group) at the Faculty of Medicine premises. The groups remain unchanged over the years regardless of the different ward allocations of the students. Each group is led by a facilitator, who serves as a well-respected staff physician in one of the affiliated hospitals. All facilitators are carefully selected for their experience as physicians, outstanding competence as professionals, and desire to devote time and energy to the student’s medical education. Facilitators participate in preparatory sessions of 16 h before the course, participate in two days of continuing training, one at the middle and one at the end of each academic year.

Students participating in the course are requested to write reflective journals between the monthly sessions, that relate to significant events or issues they encounter during their clinical rotations. The facilitator responds in person to the written journals and facilitates a group discussion following issues that arise from the journals, discussions that are mostly led by the students. Once or twice during the course, the facilitators share a reflective journal of their own, allowing the group to discuss it as they do for the journals written by the students.

Research tools and data collection methods

Data were collected and analyzed from reflective journals over three years and from semi-structures interviews that were held with students. In the reflective journals, the students described individual experiences or meaningful issues/events from their clinical rotations. Additionally, they discussed ethical issues, values, and organizational or emotional challenges. The average number of words in a reflective journal was 459.

Medical students were interviewed using a semi-structured interview that lasted 50–60 min. The questions of the interview were composed by two experts in medical education and inspired by research conducted by Vivekananda-Schmidt et al. [31]. Based on the research aims we composed 10 interview questions which enabled us to collect a sufficient amount of data regarding aspects of professional identity. The location and time for the interviews were determined by the interviewees. Here are examples of questions from the interview:

Can you describe two significant events from your clinical rotations that had a lasting impact on you? Please describe the circumstances of the events and explain why they were significant for you.

Please provide one or two examples of topics or events you shared and described during the course discussions.

Did listening to other group members sharing their experiences help you better understand situations you had encountered? Please elaborate in what sense did it help you?

Research participants

Over a period of three years, we conducted an in-depth investigation of five medical students who participated in a course specifically designed to foster PIF during their clinical years. Participants were selected using purposeful sampling method with the goal of identifying information-rich cases that would best address the research questions [32, 33]. To ensure consistency, all five students were selected from the same course group, which was led by the same experienced facilitator throughout the three years. Each student attended all 17 course sessions and regularly submitted reflective journals. All participants expressed a high level of comfort in sharing their thoughts and emotions with the research team, which contributed to the depth and richness of the data collected. We chose to analyze findings from five students for the case-studies as the categories arising from analyzing written journals reached saturation (more details to follow under data analysis). The participants were from diverse genders and cultural backgrounds, a representation of the cultures of students that study in our Faculty of Medicine.

The university’s Ethics Committee approved the study (approval no 2018-037). Students signed informed consent forms before participating in the study. All identifying information was removed, and participants were assigned pseudonyms to protect confidentiality.

Data analysis

Reflective journals and interviews were analyzed thorough directed content analysis [34–36]. The coding process involved several steps. We began with thoroughly reading and analyzing 47 reflective journals written by the five case-studies. Through immersive reading, bearing in mind the body of knowledge regarding PIF [34–38] the data from the reflective journals were coded. The process of coding enabled to establish categories relating to aspects of professional identity in both deductive and inductive analysis [39]. The theoretical categories deductively imposed were based on literature in the field of PIF. Specifically, we drew from prior studies addressing key components of PIF such as:

Reflexivity, Effective communication, and Empathy development [2, 4, 8, 21]. The inductive analysis revealed additional categories related to aspects of PIF. Inductive categories emerged from the data during our iterative coding process. We identified four additional categories that were not predetermined but rather surfaced from participants’ narratives: Peer relationships, Students’ conception of themselves as future physicians, Specialty choice, and Challenges during clinical rotations.

The process of building the codebook included meetings between the first and second authors in which revisiting categories their description and matching examples from the data was established through a negotiated agreement [40, 41]. After establishing the first version of the code book, meetings with the third author were held and refinement of the names and description of the categories, based on additional examples from the data, was established. After that, to ensure trustworthiness, an inter-rater reliability process was conducted. There were two rounds of validation involving the second author and two members of the research group who are experts in educational research. The first agreement percentage for 19 examples from the data was 42.34%. A meeting was held to resolve disagreements and further training of the team regarding the codebook. The second agreement percentage for 33 examples was 88.24% with Fleiss’ kappa value of 0.819(43). An example of how disagreements among coders were resolved is provided in “Additional file 1 - An example of how disagreements among coders were resolved”.

Finally, we resolved any discrepancies left by refining the coding book. The entire set of the data (47 reflective journals) was then coded by the second author, and no additional categories were recognized, and saturation was achieved.

In addition to the above analysis, to study the development of reflective expressions for each case-study, we have again analyzed all reflective journals. This process was preformed deductively according to Lee’s criteria for evaluating reflective writing [12]. These criteria included three levels of reflection. The first level is descriptive, where students describe an event from their perspective. The second level is interpretive, where students interpret situations and relate those situations to their own experiences. The third level is critical, where students analyze their experiences to gain knowledge, or alter perceptions, behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes toward their profession. This process was validated by two educational researchers and one medical education expert through a negotiated agreement approach.

The five medical students were interviewed using a semi-structured interview protocol that lasted 50–60 min and consisted of 10 open-ended questions. The location and time for the interview were determined by the interviewees. The coding process of interviews included several steps. First, we transcribed and read the transcripts multiple times. Second, we coded the transcripts while employing the students’ reflective journals coding book, described previously. A total of 47 reflective journals were analyzed, with an average length of 459 words per journal. Additionally, five semi-structured interviews were conducted, each lasting between 60 and 70 min. Through this analysis, we identified 172 excerpts, which were coded into seven main categories.

Results

The categories we discuss below represent various aspects of the professional identity of medical students in their clinical years, as well as their reflective expressions related to PIF. In the following sections, we characterize each category and elaborate on what each entails, supported by data from our analysis.

Reflexivity – Reflexivity is a core aspect of PIF, it enables students to critically examine their experiences. This category involves the description of an event or experience encountered by the student, reflecting on cognitive and emotional aspects of it, on past and present experiences as well as thoughts for the future. Students’ excerpts in this category included reflections on thinking, understanding or learning how to better handle such experiences in the future. The following excerpt is a quote from a student’s journal:

I am glad I had the opportunity to witness such a challenging resuscitation because I will encounter such circumstances again and I will need to handle it. I am wondering whether anybody in my group felt overwhelmed as I did but just did not show it. Will I become more resilient as I get more experienced and be able to participate in preforming a resuscitation, or even stand closer to the patient? I hope I will be less startled when I know what to do.

Our analysis revealed that the Reflexivity category appeared in 37% of the excerpts, making it the most prevalent category. This category was further divided into five main sub-categories, which are described below.

My emotions – This sub-category includes personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and feelings about clinical situations.

During my psychiatry rotation I was interviewing a patient with two of my fellow-students. All of a sudden, the patient stood up, raised his voice, and refused to answer further questions. The three of us felt threatened; we feared he will become physically violent. We were caught by surprise, scared, and felt unprepared for the situation.

This student’s reflection highlights his emotional response and feelings about the clinical situation. In this excerpt there is also an acknowledgment of feeling unprepared for the situation, which suggests a cognitive reflection on his current skills and readiness to handle such events. By reflecting on this experience, the student is likely to develop strategies to better handle similar situations in the future, such as improving his ability to stay calm and respond effectively to unexpected and intimidating patient behaviors.

My growing clinical experience – This sub-category includes insights from real-life encounters during clinical rotations, broadening students’ competencies as future physicians.

A young patient was admitted to the ward during the night, and was presented by the resident on call during morning rounds. Most staff physicians agreed with the resident diagnosis, but I thought differently. I was hesitant to share my opinion as I was just a medical student, but I found the right timing to speak up, and suggested my diagnosis. I felt good about it.

The student reflects on their ability to analyze clinical information and develop their own medical judgment. Their hesitation, followed by sharing their opinion, highlights an emerging sense of professional role and growing self-assurance. After sharing their diagnosis, they feel a sense of accomplishment and growth.

An additional excerpt exemplifies how a student is gaining insights into their clinical preference and professional identity through their experiences in clinical rotations:

As I was going through my clinical rotations, it became clear to me that having an ongoing professional relationship with my patients is more fulfilling to me than meeting them once, diagnosing them, treating them, and saying goodbye.

The student reflects on their preference for long-term patient relationships, recognizing what they find fulfilling—an insight that may shape future career choices and support their professional identity development.

My decision-making process – This sub-category encompasses decision-making abilities in clinical settings, insights into how complex decisions are approached, and growth in making informed decisions.

I observed a resuscitation that took place in the emergency department. I stood at a distance, taken aback by what I witnessed. I began to question whether I would ever be capable of taking the lead in such a situation.

The student focuses on the challenges involved in decision-making processes under stressful conditions, such as resuscitation. They critically evaluate their readiness to handle such situations, and identify areas for growth in their clinical practice.

My thoughts and beliefs in relation to cultural diversity – This sub-category focuses on how students’ cultural background, personal beliefs and values influence their clinical practice and interactions with patients. It includes insights into how cultural diversity impacts decision-making, patient care, and professional relationships.

I attended a termination of pregnancy at the 16th week of gestation… I could not stop thinking… Is it acceptable to refuse to perform it? What if everyone choses to opt-out? I know there is no definitive answer. I think it depends on each individual’s background and opinions. Personally, I believe it is better to perform such procedures to alleviate suffering for everyone involved, the baby and the family. Similarly, I think that euthanasia of sick and elderly people should be allowed to end their lives with dignity. I believe that a baby born to parents who do not want it is destined to suffer. However Still, I am not sure if I could personally carry out such a procedure.

The student reflects on how cultural background and personal beliefs influence clinical decisions. This awareness supports a more nuanced and reflective approach to ethically complex situations, contributing to their professional identity formation.

My perception of the hierarchy of the medical profession – This sub-category focuses on students’ understanding of the hierarchical structure within the medical profession. It includes insights into their evolving role, the dynamics of professional relationships, and the importance of various healthcare team members in patient care.

I feel that I am starting to be regarded more as a physician and less as a student. This change is very significant for me in several ways. First, I need to find a way to establish my place within a department team that is already quite established. Second, this is the first time I feel that more is expected of me than just arriving on time, listening, and occasionally answering questions. There are real expectations for results, a genuine involvement in decision-making, and patient management.

Next, we describe and characterize additional categories we identified, and elaborate on what each of them entails, supported by data from our analysis.

Peer relationships – Peer relationship contributes to PIF by offering a collaborative environment where students share experiences, discuss challenges, and support one another emotionally. This sense of community reinforces positive behaviors, fosters belonging, and enhances reflective capacity. Students reported that studying together and participating in peer or facilitator-led discussions helped them manage difficult situations, express emotions, and deepen their reflections during clinical rotations. Group discussions where either led by a facilitator (a staff physician) or by the peers themselves.

On my first clinical rotation I made a mistake that could have potentially compromised my patient’s care. I was disappointed in myself, I felt like a failure for many hours after the incident. I was able to deal with it only thanks to the support I received from my group members.

This reflection illustrates how peer support helped the student manage a difficult emotional experience, reinforcing confidence and promoting reflective growth—both of which are integral to developing a professional identity. This support fosters a sense of belonging and community, essential for developing a strong professional identity.

An additional excerpt example discerns how Peer relationships develop a stronger sense of belonging and community, which ultimately contributes to growth as a compassionate and competent physicians:

I think the meetings [in the course] brought us closer together and revealed deeper layers of thoughts and feelings in each of us that I would otherwise have not known. We are all so different culturally, and yet we complete each other in a beautiful way, and that is what I believe makes us a great group of healthcare professionals.

The student highlights how a supportive, diverse environment fosters collaboration and empathy—key elements of professional identity.

The following example highlights how the student recognized the value of a supportive peer group by contrasting it with a less cohesive one:

Most of our group did the psychiatry rotation together with another group, and I realized how lucky I am to be in my group. In the other group, there were poor relationships among the members. They barely talked to each other, and scarcely participate in the seminars that are held during the rotation.

Students’ conception of themselves as future physicians – This category includes students’ general views on developing respectful and trustworthy doctor-patient relationships, the physicians’ role in assisting patients to make medical decisions, a sense of satisfaction from working as a physician, and the complexity of leading a “physician’s life”. Students describe their perception of the medical profession, the role of the physician, and how they envision themselves as future physicians.

I wish my passion for the medical profession will last as long as I practice. I do not want to be like physicians I have met, who suffer burnouts… Those who see their patients as a list of symptoms or diseases. I know it might be easier not to see the whole picture, so as to care less about our patients. It might consume a lot of energy, but I am not looking for the easy way.

This excerpt shows the student’s view of the physician’s role as both compassionate caregiver and patient advocate, highlighting the balance between compassionate care, and professional detachment.

The next excerpt illustrates the student’s thoughtful consideration of a holistic approach to patient care, continuous learning, and balancing personal and professional fulfillment:

I often think about my personal life and about my future life. On one hand, I feel that there is no substitute for the profession I have chosen. It allows me to express myself academically, professionally, practically and emotionally. I always strive to know more and more, and I always see the person in front of me as a whole, with physical, emotional, and spiritual entities… I hope that in the future, I will choose a residency that will bring good for me and for my family, and will benefit my patients and my environment as well. Additionally, I wish to find a profession where I will be both satisfied and able to function properly as an equal among equals.

In the above excerpt the student expresses satisfaction with their chosen profession, a commitment to ongoing learning, and a desire to balance work and life within a supportive medical community.

Effective communication – Students emphasize the importance of active listening to create effective communication between physicians, patients and their families. This contributes to effective treatment and reduces medical errors.

My first admission on the ward was of a patient in her forties. She was cooperative yet brief in her answers. When I asked her about her family background, she told me about the difficult experiences she had throughout her life. She was a relatively new immigrant, and she shared some challenges she faced during her immigration… she burst in tears. It was a difficult conversation for me… At the end of our meeting, she said to me: ‘Thank you very much for listening to me, I already feel much better’. This interaction with the patient reminded me why I chose this profession as my career, and why becoming a doctor is worth going through such a long and challenging path. I understood the importance of listening to the patient and allowing them to share their feelings. I believe it is an essential part of the patient’s treatment and recovery.

This student recognizes that creating a safe space for patients to share emotions can improve their well-being. They highlight the role of empathy and active listening in strengthening the physician-patient relationship and improving outcomes.

In the next excerpt example, a student recognizes that medical errors often stem from communication breakdowns. The student underscores how communication is crucial for effective treatment and for reducing medical errors.

Medical errors are a very broad topic… During my studies, I witnessed situations in which a knowledgeable physician alone was not enough to tailor the best treatment for a patient if the patient was not heard. It is important to listen to the patient’s wishes and beliefs, their family, their nurse, and anyone who might know the patient better than the physician. If a mistake is made, it is important to admit the mistake, apologize, and take responsibility to reestablish trust with the patient.

Specialty choice – this category reflects the evolving nature of PIF, where experiences shape and refine a student’s understanding of their professional identity and future goals. Students describe aspects associated with their career choices, including field-specific interests, clinical rotation experiences, and cultural or socioeconomic background.

As a result of my experience in the Pediatric ward I decided to pursue Pediatrics as my future specialty. My choice was made after I realized that in pediatrics, I would find many aspects of the medical profession that are important to me, like long-term relationships with patients and their families. I believe this is how one can truly make an impact and create change for the patient. I realized that the ability to handle difficult situations and challenging patients during one’s medical career lies in their ability to connect with their patients and the families, rather than maintaining a distant approach.

This excerpt highlights how clinical experiences can shape a student’s choice of specialty by reinforcing their desire to pursue a field that aligns with their values and goals. The student emphasizes the importance of building long-term relationships with patients and their families, which is a key aspect of PIF.

An additional excerpt example illustrates the transformative journey from theoretical learning to practical application in medical education, and its expected impact on career choices.

Before the “clinical years”, meaning when we started our clinical rotations, a large part of my medical studies was theoretical. The transition from theory to practice requires not only knowledge but also experience and self-confidence. At the beginning of my studies, being a physician felt very distant. During my clinical rotations, I started to gain self-confidence in managing conversations with patients and understanding and analysing different medical cases. In the neurology rotation, for instance, my admission notes for my first patient were much better than my admission notes in pediatrics, which I did before, and from my notes in Internal medicine, which was my first clinical rotation. The more experience I gain, the clearer it will become what I really want to do as a physician.

The student highlights the shift from theoretical knowledge to practical application. This transition is crucial in PIF as it marks the beginning of hands-on experience, which is essential for developing clinical skills and confidence. The student’s journey from feeling distant from the role of a physician to gaining confidence and clarity about their career path illustrates both emotional and cognitive development. This growth is integral to forming a professional identity that encompasses both the technical and empathetic aspects of medical practice. The student acknowledges that with more experience, their career aspirations will become clearer.

Empathy development – Students express empathy towards patients and their families, show concern and care, and wish to alleviate patients’ suffering.

Each time I hear the words ‘the patient had died’ or ‘the patient in on the verge of death’ which seems to be easily uttered by staff physicians, I temporarily lose my ability to hear anything that follows… I feel as if the world has temporarily stopped.

The student’s response to a patient’s critical condition reflects deep empathy and emotional involvement, suggesting they are internalizing the medical profession’s values of compassionate care alongside clinical competence.

The next excerpt is another example of a medical student’s deep empathy and concern for patients:

One of the hardest things for me is to see someone in pain and suffering, especially children or helpless elderly people. After an experience in the pediatric ward, where I learned how important it is to be gentle with our young patients, and how physicians try to prevent inflicting pain by all means, it became even harder. We, as physicians, might inflict a lot of pain on our patients, of course for a good purpose. However, maybe we can stop and think for a moment before performing a painful procedure, and consider how to reduce the pain, even if it takes a toll of investing more time and energy from us, especially if it is not an emergency situation. I often ask myself: why don’t we treat adults the way we treat kids? Don’t they feel pain? And the helpless elderly? It’s true that adults have the advantage of knowing that the pain from a procedure has a purpose, yet children don’t understand that the pain is for their benefit. However, I am sure that with a bit more thought, consideration, and effort, we can reduce pain in adults and the elderly as well.

The student expresses strong empathy for vulnerable patients and a desire to alleviate suffering, even at personal cost. Their willingness to question standard practices reflects a developing, patient-centered approach and alignment with the core values of compassionate medical care.

Challenges during clinical rotations – Facing challenges during clinical rotations contributes to the student’s professional growth. Developing problem-solving skills and the ability to adapt to new challenges are critical components of PIF. Students describe professional and academic challenges encountered during clinical rotations in hospital departments. For example, difficulties in diagnosing and solving unfamiliar medical situations and worries about facing scenarios not yet encountered during their studies.

One of the significant challenges I am facing during my pediatric rotations is how to deal with children who have suffered major trauma, or those with incurable diseases. It is difficult to cope with situations where I am not capable of relieving their pain.

The text highlights the student’s need to adapt to complex and unfamiliar medical situations. It forces them to confront their limitations and seek ways to improve their skills and knowledge.

The next excerpt illustrates the continuing academic challenges faced by students during clinical rotations:

Last week, I started my second rotation in pediatrics. Once again, my colleagues and I found ourselves in embarrassing situations where we are asked many questions, but did not know the correct answers, especially since it had been over a year since we last dealt with pediatrics. However, the questions are asked in good spirits, it was clear that the physicians wanted us to improve. We no longer fear these situations as we gain experience and learn to take things in stride.

The student describes the difficulty of answering questions during clinical rotations, especially after a gap in dealing with a specific field. The student notes that despite the initial embarrassment, they and their colleagues no longer fear these situations. The text reflects the student’s journey from feeling unprepared to becoming more comfortable and confident in their abilities. This progression is essential for the development of a professional identity that integrates both knowledge and practical skills.

Following the qualitative analysis of the aspects of professional identity that develop during medical students’ clinical years, we conducted a frequency analysis to identify the most prominent aspects. Reflexivity was found to be the most prominent category, and the following categories were identified, in decreasing order of frequency: Peer relationships, Students’ conception of themselves as future physicians, Effective communication, Specialty choice, Empathy development, Challenges students face during clinical rotations. This is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The percentage of different categories of professional identity and their frequency as identified from the qualitative analysis of reflective journals and from interviews with students

The analysis of these categories and their frequencies provides a comprehensive understanding of the aspects that contribute to the development of professional identity formation in medical students during their clinical years. It underscores the importance of self-reflection, peer support, effective communication, empathy, and overcoming challenges in shaping a well-rounded and competent physician.

Having identified the key aspects of professional identity development (research question 1), we now turn to the second part of our analysis, which explores the reflective expressions that support this development (research question 2).

We reanalyzed all reflective journals in order to examine the progression of reflective expressions for each case-study, based on Lee’s [12] criteria for evaluating reflective writing, and divided them to three levels: (a) Descriptive (b) Interpretive and (c) Critical (See data analysis section). Table 1 presents examples for reflective expressions based on Lee’s categories from the reflective journals of two students. They describe an event they encountered during the fourth year of their studies (the first year of clinical rotations in our medical school).

Table 1.

Examples of the three levels of reflective writing as derived from journals of two students

| Student | Descriptive level | Interpretive level | Critical level |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | “A patient arrived bluish and unresponsive and was immediately placed in the resuscitation room. I was surprised that they allowed us in… The room was small, fowl- smelling, and there were many medical staff members crowded there”. | “I was concerned that our presence would disturb and distract the medical staff… I was surprised by what was happening with me being a witness… It was very difficult for me to comprehend that I was witnessing a battle between life and death”. | “Observing this difficult situation was a valuable clinical experience as I will have to deal with similar situations later in my career as a physician. Was I the only person in the room to feel nauseous? I assume the more I will see situations like this, and the more I learn- the better I will be able to handle these stressful situations. |

| B | “During one of the department rounds, I heard a man screaming, he was very angry… He claimed that none of the physicians or nurses had treated him since he arrived, despite his suffering from a severe leg pain”. | “…I was scared and wondered why a person was standing and shouting in the hospital corridor in such a manner… I think this should not have happened, that we should learn from such an incident… I learned that physicians and nurses are quite used to seeing pain and suffering, therefore are less sensitive to it than me, but none the less it is a difficult experience for the patient”. | “…I believe it is essential to remember that a patient that complains about pain is suffering, and that for him it is a unique experience, in spite of the fact that we, as medical professionals, have encountered many complaints like his. We need to remain compassionate and offer support even when we get more experienced”. |

From analyzing the journals written by the case-studies during the three years of clinical rotations, it was clear that the students’ reflective expressions have gradually developed. The number of noteworthy events at the level of interpretive reflection was the highest (N = 41) compared to descriptive (N = 35) and to critical reflections (N = 16) in each of the three clinical years, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reflective expressions according Lee’s [12] criteria for reflective writing according to the clinical year

| Level of reflective writing Clinical year |

Descriptive | Interpretive | Critical | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th year | 8 (36%) | 11 (50%) | 3 (14%) | 22 |

| 5th year | 17 (34%) | 23 (47%) | 9 (18%) | 49 |

| 6th year | 10 (48%) | 7 (33%) | 4 (19%) | 21 |

| Total | 35 (38%) | 41 (46%) | 16 (17%) | 92 |

Analysis of the journals indicated variations between students in relation to the level of reflective writing they had used most often: Two of the students wrote mostly at the level of descriptive reflection without progression during the years. The other three used all three levels of reflection in their reflective journals with an increasing number of interpretive and critical writing during the fifth and sixth years.

The authors identified a connection between reflective writing and PIF. Table 3 highlights how specific reflective expressions relate to different aspects of PIF. For instance, reflective expressions regarding the personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and clinical situations were found to be an important component across multiple aspects of PI, i.e.: effective communication, empathy development, and challenges students face during clinical rotations. Additionally, reflective expressions about the students’ growing clinical experiences and decision-making processes are pivotal in shaping their conceptions of themselves as future physicians and influencing their choices for future residency.

Table 3.

Reflective expressions relating to different aspects of PIF

| Aspects of PIF of medical students during their clinical years | Reflective expressions relating to aspects of PIF |

|---|---|

| Peer relationships | My emotions - personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and feelings about clinical situation; My growing clinical experience; My decision-making process in different clinical settings; My thoughts and beliefs in to cultural diversity; My perception of the hierarchy of the medical profession |

| Student’s conception of themselves as future physicians | My emotions - personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and feelings about clinical situation; My growing clinical experience; My decision-making process in different clinical settings; My perception of the hierarchy of the medical profession |

| Effective communication | My emotions - personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and feelings about clinical situation; My growing clinical experience; My thoughts and beliefs in relation to cultural diversity |

| Specialty choice | My emotions - personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and feelings about clinical situation; My growing clinical experience; My decision-making process in different clinical settings; My perception of the hierarchy of the medical profession |

| Empathy development | My emotions - personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and feelings about clinical situation; My growing clinical experience; My thoughts and beliefs in relation to cultural diversity |

| Challenges during clinical rotations | My emotions - personal emotional state, feelings towards patients, and feelings about clinical situation; My growing clinical experience; My thoughts and beliefs related to cultural diversity; My perception of the hierarchy of the medical profession |

Discussion

There is a paucity of studies focusing on medical students during their clinical rotations using a longitudinal design, particularly in cultivating aspects of their professional identity, as presented in this study. Previous studies have indicated that medical students’ professional identity is shaped during their medical school years through experiential learning, interactions with medical professionals and participating in various clinical situations [2, 3, 8]. Additionally, research has indicated that reflection about clinical experiences is a critical element in creating and shaping professional identity [18, 27].

Our findings suggest that the five students who wrote reflective journals discussed specific aspects related to their PIF. While these findings align with and expand upon previous research, they underscore, in the study’s limited context, the multifaceted nature of PIF. Through our analysis, we conceptualized each aspect of PIF and elaborated on it. Given the exploratory nature of this study, future research with larger, more diverse samples is needed to validate and generalize these findings.

Our results show that reflexivity was the most prominent category. This finding strengthens previous research on the significance of reflexivity for PIF [2, 42] and underscores the need for medical education programs to incorporate reflective writing and/or other modalities of reflective expressions to enhance students’ PIF [17, 43]. Our study provides a nuanced understanding of reflexivity by identifying specific aspects that students reflect on during their clinical years. By breaking down reflexivity into specific aspects (i.e., My emotions, My growing clinical experience, My decision-making process, My thoughts and beliefs in relation to cultural diversity, My perception of the hierarchy of the medical profession) our study provides a more comprehensive understanding of how students process their experiences and develop their professional identities during their clinical years.

We consider these sub-categories of reflexivity as valuable tools for generating ‘food for thought’, facilitating group discussions, and encouraging personal reflection. This approach aims to support students in their journey to develop a unique professional identity. Our findings point out that dedicated time for sharing emotional experiences and cognitive challenges from clinical rotations were crucial for PIF during the clinical years of medical school. While Clandinin et al., [44] previously established that pedagogical space encourages reflection among future physicians, our study extends this understanding by suggesting the effectiveness of peer-led formats. In addition to traditional faculty-led reflection sessions, students reported that peer-led discussions created a unique dynamic. This environment fostered an increased internal motivation to share significant experiences, even when those experiences were emotionally challenging. This aligns with but also builds upon Steinert et al., [45] work on the role of relationships in PIF. While the authors focused broadly on positive relationships with colleagues and instructors, our findings suggest that peer-to-peer relationships in structured small groups may be particularly powerful for processing clinical experiences. Thus, Peer relationships can be considered, as implied from our analysis, as an aspect of PIF. Our study identifies specific dimensions of ‘Student’s conception of themselves as future physicians’ that were previously unexplored. While Scheide et al. [42] and Pitkala & Mantyranta [46] established that medical students’ professional self-conception evolves through patient interactions and reflective practice, they focused on the general adoption of the physician’s role. Our findings unpack four distinct aspects of professional self-conception during students’ clinical years: developing respectful and trustworthy doctor-patient relationships, the physician’s role in advising and assisting patients in making informed medical decisions, the sense of satisfaction from working as a physician, and the complexity of leading a “physician’s life”. The study also illuminates the emotional dimension of PIF. While previous studies emphasized the technical and cognitive aspects of becoming a physician, our research reveals that students’ self-conception is equally shaped by their growing understanding of the interpersonal and lifestyle implications of medical practice. This more comprehensive view of PIF suggests that medical education programs should address not only clinical competencies but also the personal and practical challenges of the medical practice.

Most studies on the development of communication skills in medical students and physicians have focused on simulation-based training, performance assessments, and surveys evaluating communication skills [37, 47]. Our study offers a more authentic and personal perspective on communication skills. In our study, students freely articulate their thoughts, revealing their own perceptions of effective communication in real-world scenarios. This setting allowed them to reflect on how they would behave in similar clinical settings as future physicians. This approach enabled students to reflect on their experiences and develop a deeper understanding of effective communication in clinical settings.

Our study also shows the connection between residency selection and PIF as students related to their cultural and social backgrounds, along with the desire to become a role model. These two attributes were particularly prominent among women. Previous studies on specialty choice have primarily focused on identifying these factors [48–50]. These studies have provided valuable insights into the external factors that shape residency choices. Our study shows that the decision-making process for residency is closely linked to PIF during the years of clinical rotations during medical school. When students are encouraged to openly reflect on their experiences, they often discuss choosing a residency. By highlighting the connection between residency choices and PIF, our study provides a deeper understanding of how personal and professional experiences during clinical years influences career decisions. This insight can inform educational frameworks that support students in making informed residency choices that align with their PIF.

Research also documents a loss of empathy among medical students during their early clinical training. This decline is often attributed to the shift in students’ roles as part of the team providing patient care, moving from viewing patients as individuals experiencing suffering to seeing them as objects of clinical work [51, 52]. Our study indicated that when students described their feelings regarding dealing with challenging events and patients, they emphasized the importance of compassion and concern for alleviating patients’ suffering. The students wrote about feeling empathy towards patients’ emotional and physical state, indicating this competency from early on during their clinical rotations. Our study shows that early clinical experiences shape students’ empathy and suggests that reflection during these years can foster compassion for patients.

The five case studies expressed and discussed the professional, academic, and personal challenges they encountered during their clinical rotations in hospital departments. This emphasizes the importance of addressing challenges in clinical rotations as a critical component of PIF and highlights the role of reflective writing in helping students process and learn from these challenges. For instance, students often wrote about their struggles with balancing academic responsibilities and patient care, and how these experiences contributed to their development as future physicians.

Clinical rotations provide essential learning experiences and opportunities for professional growth, but they also present challenges that must be addressed to enhance medical education and patient care [52, 53]. Despite the relatively limited number excerpts relating to this category in the journals and interviews, it is important to address these challenges, as students viewed them as an essential part of their professional development.

Based on Lee’s criteria for evaluating reflective writing [12] (descriptive, interpretive, and critical), our analysis showed that students’ reflective writing developed over time, indicating an increasing capacity to interpret and critically analyze situations, thoughts, and feelings. However, there were individual differences between students regarding the depth of their reflections. Many studies have found that medical students’ ability to reflect upon experiences contributes to the development of their professional identities [13, 22, 24, 29]. Written and verbal reflective expressions during medical school were found to help develop reflexivity and enhance the ability to express emotions [54, 55]. Writing a reflective journal that encapsulates all three levels of reflective expressions was found to be a challenging task for some students, who mostly used the descriptive level. Therefore, offering a personalized program in order to assist those who struggle with implementing all three levels in their reflective journals is recommended. Despite this challenge, all students enrolled in the study have shown some improvement in the depth of their reflexivity.

This study provides valuable insights into the complex relationship between the characteristics of reflective expressions and the main aspects of PIF of medical students during their clinical years. The thorough analysis of reflective journals written over a significant period of three years, together with the thorough analysis of semi-structured interviews with the students who wrote those journals, offers valuable insights into the main aspects of the professional identity of medical students at the stage of clinical rotations during medical school. Further research that includes a larger sample of medical students and physicians at different stages of their studies and career may help construct a more solid educational framework for enhancing professional identity development at its best.

Limitations and further research

This study is exploratory in nature, and further research with larger, more diverse samples is needed to validate these findings and expand our understanding of PIF in medical education. Case studies provide detailed insights into specific phenomena, contexts, or individuals, making them invaluable for understanding complex and nuanced situations. However, a significant limitation of this approach, as in our study, is the limited number of cases—five students—which reduces the potential for generalizability. Nevertheless, these five students represented the genders and diverse cultures in our medical school, and the rich data derived from their journals and interviews over three years was sufficient to address our research questions.

Another limitation of our study is the potential for researchers’ biases in interpreting students’ reflective expressions. However, the rigorous data analysis, as detailed in the section of data analysis, aimed to reduce these biases and strengthen the trustworthiness of the results.

Further research is warranted on professional identity formation (PIF) of the facilitators who lead student groups in courses aimed at fostering PIF; How interactions with students, listening to discussions, and reading reflective journals impact (or not) their own professional identity as experienced physicians and medical educators.

This study contributes to the existing knowledge by highlighting specific aspects of PIF as observed through the reflective expressions of medical students during their clinical rotations. We see this study as a potential first step to initiate a discussion on a learning progression framework that will cultivate PIF at each stage of the medical profession.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The institution’s financial aid for the second author is greatly appreciated.We would like to thank the students who were willing to share their thoughts, feelings, and reflective journals with us.We would like to thank Mrs. Ilana Dobkin for her help in the literature review.

Author contributions

S.A. is the primary advisor of A.S that at the time of the research was a master student, N.K is the second advisor of the second author. All three authors contributed to this study in conception and design of the work, the analysis, and interpretation of the data. All three authors drafted the work and revisited it, writing was led by SA. All three authors approved of the version to be published.

Funding

No funding from grants was received. The second Author received the university scholarship.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is not a clinical trial. The study was conducted in accordance with The American Psychological Association’s (APA) Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct. The university’s Ethics Committee approved the study (approval no 2018-037). Students signed informed consent forms before participating in the study. All identifying information was removed, and participants were assigned pseudonyms to protect confidentiality.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Findyartini A, Anggraeni D, Husin JM, Greviana N. Exploring medical students’ professional identity formation througwritten reflections during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Health Res. 2020;9(1):4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Findyartini A, Greviana N, Felaza E, Faruqi M, Zahratul Afifah T, Auliya Firdausy M. Professional identity formation of medical students: A mixed-methods study in a hierarchical and collectivist culture. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawatsky AP, Santivasi WL, Nordhues HC, Vaa BE, Ratelle JT, Beckman TJ, et al. Autonomy and professional identity formation in residency training: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2020;54(7):616–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarraf-Yazdi S, Teo YN, How AEH, Teo YH, Goh S, Kow CS, et al. A scoping review of professional identity formation in undergraduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3511–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarraf-Yazdi S, Goh S, Krishna L. Conceptualizing professional identity formation in medicine. Acad Med. 2024;99(3):343–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilligan C, Loda T, Junne F, Zipfel S, Kelly B, Horton G, et al. Medical identity; perspectives of students from two countries. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ong YT, Kow CS, Teo YH, Tan LHE, Abdurrahman ABHM, Quek NWS et al. Nurturing professionalism in medical schools. A systematic scoping review of training curricula between 1990–2019. Med Teach [Internet]. 2020 Jun 2 [cited 2025 Jun 8];42(6):636–49. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1724921 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Park GM, Hong AJ. Not yet a doctor: medical student learning experiences and development of professional identity. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald A. Professional identity: A concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2020;55(3):447–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarvis-Selinger S, Macneil KA, Costello GRL, Lee K, Holmes CL. Understanding professional identity formation in early clerkship: A novel framework. Acad Med. 2019;94(10):1574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalet A, Buckvar-Keltz L, Harnik V, Monson V, Hubbard S, Crowe R, et al. Measuring professional identity formation early in medical school. Med Teach. 2017;39(3):255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HJ. Understanding and assessing preservice teachers’ reflective thinking. Teach Teach Educ. 2005;21(6):699–715. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams J, Ari M, Cleeves M, Gong J. Reflective writing as a window on medical students’ professional identity development in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(2):117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koole S, Dornan T, Aper L, De Wever B, Scherpbier A, Valcke M, et al. Using video-cases to assess student reflection: development and validation of an instrument. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merlo G, Ryu H, Harris TB, Coverdale J. MPRO: A professionalism curriculum to enhance the professional identity formation of university premedical students. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane AS, Roberts C. Contextualised reflective competence: a new learning model promoting reflective practice for clinical training. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):71–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donohoe A, Guerandel A, O’Neill GM, Malone K, Campion DM. Reflective writing in undergraduate medical education: A qualitative review from the field of psychiatry. Cogent Educ. 2022;9(1):2107293. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tagawa M. Scales to evaluate developmental stage and professional identity formation in medical students, residents, and experienced Doctors. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbour JB, Lammers JC. Measuring professional identity: A review of the literature and a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis of professional identity constructs. J Prof Organ. 2015;2(1):38–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan A, Moran CN, Byrne D, Hickey A, Boland F, Harkin DW, et al. Do professionalism, leadership, and resilience combine for professional identity formation? Evidence from confirmatory factor analysis. Front Med. 2024;11(13):1385489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandran L, Iuli RJ, Strano-Paul L, Post SG. Developing a way of being: deliberate approaches to professional identity formation in medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(5):521–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Désilets V, Graillon A, Ouellet K, Xhignesse M, St-Onge C. Reflecting on professional identity in undergraduate medical education: implementation of a novel longitudinal course. Perspect Med Educ. 2022;11(4):232–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman LA, Shew RL, Vu TR, Brokaw JJ, Frankel RM. Is reflective ability associated with professionalism lapses during medical school? Acad Med. 2016;91(6):853–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim JY, Ng CYH, Chan KLE, Wu SYEA, So WZ, Tey GJC, et al. A systematic scoping review of reflective writing in medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, Archer J, Barnes R, Bleakley A, et al. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today’s experiences of tomorrow’s Doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann KV. Theoretical perspectives in medical education: past experience and future possibilities. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):60–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the clouds: three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1606–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatem DS, Halpin T. Becoming doctors: examining student narratives to understand the process of professional identity formation within a learning community. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vivekananda-Schmidt P, Crossley J, Murdoch-Eaton D. A model of professional self-identity formation in student Doctors and dentists: A mixed method study assessment and evaluation of admissions, knowledge, skills and attitudes. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract. 1996;13(6):522–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baškarada S. Qualitative case study guidelines. Qual Rep. 2014;19:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis. SAGE Open. 2014;4(1):215824401452263. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh HFF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colleagues and Authors. Collegue J Res Sci Teach. 2015.

- 37.Karnieli-Miller O, Michael K, Gothelf AB, Palombo M, Meitar D. The associations between reflective ability and communication skills among medical students. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(1):92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visser CLF, Wilschut JA, Isik U, Van Der Burgt SME, Croiset G, Kusurkar RA. The association of readiness for interprofessional learning with empathy, motivation and professional identity development in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, O’Brien BC, Rees CE. Shedding the Cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ. 2017;51(1):40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watts FM, Finkenstaedt-Quinn SA. The current state of methods for Establishing reliability in qualitative chemistry education research articles. Chem Educ Res Pract. 2021;22(3):565–78. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garrison DR, Cleveland-Innes M, Koole M, Kappelman J. Revisiting methodological issues in transcript analysis: negotiated coding and reliability. Internet High Educ. 2006;9(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheide L, Teufel D, Wijnen-Meijer M, Berberat PO. (Self-)Reflexion and training of professional skills in the context of being a Doctor in the future - a qualitative analysis of medical students’ experience in LET ME… keep you real! GMS J Med Educ. 2020;37(5):1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmad A, Bahri Yusoff MS, Zahiruddin Wan Mohammad WM, Mat Nor MZ. Nurturing professional identity through a community based education program: medical students experience. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2018;13(2):113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clandinin J, Cave MT, Cave A. Narrative reflective practice in medical education for residents: composing shifting identities. Advances in Medical Education and Practice. Volume 2. Dove Medical Press Ltd; 2011. pp. 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Steinert Y, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):963–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pitkala KH, Mantyranta T. Professional socialization revised: medical students’ own conceptions related to adoption of the future physician’s role - A qualitative study. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff. 2010;29(7):1310–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alaqeel SA, Alhammad BK, Basuhail SM, Alderaan KM, Alhawamdeh AT, Alquhayz MF, et al. Investigating factors that influence residency program selection among medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borges NJ, Navarro AM, Grover A, Hoban JD. How, when, and why do physicians choose careers in academic medicine? A literature review. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):680–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nuthalapaty FS, Jackson JR, Owen J. The influence of quality-of-life, academic, and workplace factors on residency program selection. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):417–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou YC, Tan SR, Tan CGH, Ng MSP, Lim KH, Tan LHE, et al. A systematic scoping review of approaches to teaching and assessing empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen AMH, Blakely ML, Daugherty KK, Kiersma ME, Meny LM, Pereira R. Meaningful connections: exploring the relationship between empathy and professional identity formation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2024;88(8):100725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holmboe E, Ginsburg S, Bernabeo E. The rotational approach to medical education: time to confront our assumptions? Med Educ. 2011;45(1):69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang JR, Lin SW. Examining reflective thinking: A study of changes in methods students’ conceptions and Understandings of inquiry teaching. 2008;6:459–79.

- 55.Austenfeld JL, Paolo AM, Stanton AL. Effects of writing about emotions versus goals on psychological and physical health among third-year medical students. J Pers. 2006;74(1):267–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.