Abstract

Background

Flexor tendon injuries are prevalent in Turkey and interest in hand rehabilitation is steadily increasing. However, there is no consensus regarding therapists’ rehabilitation decisions. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the current approaches of hand therapists Turkey toward flexor tendon injuries.

Method

A 15-item multiple-choice online survey was distributed via WhatsApp to therapists actively working in the field of hand rehabilitation in hospitals, clinics, public health institutions, and universities, who were also members of the Turkish Hand Therapists Association. The survey was distributed at two different points and remained open from February 2025 to April 2025.

Results

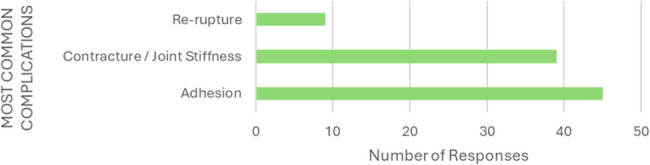

This study surveyed 117 members of the Turkey Hand Therapists Association, achieving a 51.28% response rate with 60 therapists participating. Among respondents, 68.3% were physiotherapists, 20% academicians, and 11.7% occupational therapists. Half reported 0–5 years of experience, and 51.6% held postgraduate degrees. The majority (31.7%) initiated rehabilitation within postoperative weeks 0–1, and 78.3% had communication with the surgeon. The most preferred rehabilitation protocol was a combination of early active and early passive motions (60%). Regarding treatment specifics, 33.3% administered a total of 15 rehabilitation sessions, with session durations typically between 20 and 40 min (45%). Session frequency varied, with 35% conducting five sessions per week. Experience was the primary factor influencing protocol selection (73.3%). The most used assessment method was measuring normal joint range of motion (85%), while adhesion (73.3%) was the most frequently encountered complication, and re-rupture (15%) was the least common.

Conclusions

In Turkey, there has been a transition toward early mobilization approaches particularly employing early active motion techniques. However, parameters such as the frequency and duration of rehabilitation vary significantly among therapists. Therefore, future research in Turkey should aim to identify the most effective rehabilitation frequency and duration parameters by promoting enhanced collaboration among therapists.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12891-025-08960-x.

Keywords: Injury, Hand therapy, Therapist, Flexor tendon repair

Background

Flexor tendons are an essential component of hand function; therefore, their injuries require an appropriate surgical approach and a meticulous rehabilitation program [1]. Additionally, these injuries typically occur as a result of work-related incidents and frequently affect males in the productive working age group [2, 3]. However, there is still no established gold standard for either the surgical technique or the rehabilitation program to be followed post-repair [4–8].

Numerous protocols have been described for rehabilitation following flexor tendon repair [9]. Initially, immobilization during the exudative phase of wound healing was recommended. The introduction of the Kleinert protocol marked a turning point, as it enabled early mobilization of the repaired finger through the use of rubber bands. Since the 1980 s, however, the preference has gradually shifted toward early active motion, which has been supported by numerous laboratory-based studies [10]. The historical development of rehabilitation protocols can be broadly categorized into immobilization, early controlled mobilization, and early active mobilization [11, 12]. The common goal of all protocols is to enhance tendon gliding, prevent complications, and restore the patient’s functional abilities [8, 13, 14]. However, differences exist in terms of the timing and sequencing of exercises, as well as splinting techniques [11, 12]. Although there is still ongoing debate regarding which protocol yields the most favorable outcomes, studies have shown that early mobilization protocols are superior to immobilization protocols in terms of clinical outcomes [5, 6, 15].

Outcome measures in flexor tendon injuries are heterogeneous, partly due to limited theoretical clarity on what should be assessed and differing priorities across countries regarding clinically relevant outcomes [8]. There are standardized classification systems used to interpret clinical outcomes based on joint range of motion. The three most commonly used systems are the Strickland (original and modified versions), the Buck-Gramcko system, and the Total Active Motion (TAM) system endorsed by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. For instance, in injuries involving the 2nd to 5th digits, the original classification by Strickland and Glogovac evaluates active range of motion at the PIP and DIP joints. According to this system, patients who regain < 50%, 50–69%, 70–84%, and 85–100% of normal active flexion are classified as having poor, fair, good, and excellent outcomes, respectively [16].

Another critical aspect of flexor tendon repair and rehabilitation is the development of complications. Possible complications include rupture, adhesion, contracture, revision surgeries, delayed wound healing, pulley insufficiency, triggering, persistent pain, gap formation, sensory loss, quadriga, swan neck deformity, and lumbrical plus deformity [13, 14, 17]. Among these, the most frequently encountered complication is adhesion, which occurs in approximately 30% of cases following flexor tendon injury and significantly impairs hand functionality [18, 19].

In Turkey, the practice of hand therapy is undertaken by occupational and physiotherapists as part of their undergraduate education. However, these professionals do not take formal certification exams. The Turkish Hand Therapists Association was established in 2004 with the aim of addressing this gap by bringing together therapists and promoting clinical standards through the organisation of scientific meetings and educational activities. The designation of “certified hand therapist” has not been officially recognised in Turkey [20]. Rehabilitation protocols applied after flexor tendon repair vary significantly between countries and even among hand surgery centers within the same country [12]. In the literature, there are more studies investigating surgeons’ protocol preferences, while studies examining the decisions of hand therapists regarding rehabilitation protocols, session duration, frequency, and other factors are relatively fewer [9, 13, 14]. In Turkey a study has been conducted on surgeons’ tendencies regarding flexor tendon repair [15]; however, no study has been reported on therapists’ preferences for rehabilitation protocols, commonly encountered complications, preferred assessment methods, rehabilitation durations, or related topics. Therefore, the aim of our study is to examine the current trends and management approaches of therapists in hand flexor tendon injuries in Turkey. Our hypothesis is that there will be significant variations among therapists in Turkey country regarding the characteristics of rehabilitation, such as the time of initiation, duration, and frequency.

Methods

There is no valid and reliable questionnaire available to evaluate hand therapists’ current approaches to hand tendon injuries, so a 15-item online multiple-choice survey was developed to assess these approaches. During the development of the questionnaire items, existing surveys with objectives similar to those of the present study were first reviewed. The questions included in these studies were compiled and, with expert input, adapted to the Turkish context and clinical practices. Each of the consulted experts had at least 10 years of experience in the field of flexor tendon rehabilitation. Throughout the adaptation process, the content of the questions was enriched, and the response options and language were revised to enhance practical relevance, based on feedback from two clinicians and two academics. For instance, topics such as years of professional experience, job title, workplace setting, commonly encountered complications, educational background, preferred rehabilitation protocols, communication opportunities with surgeons, and key considerations in determining rehabilitation protocols are frequently addressed in international studies. Accordingly, questions related to these areas were directly adapted from previous literature [15, 21–24]. Additional items were developed and included by experts to address the specific aims of the study. These included questions regarding the week in which rehabilitation was initiated post-repair, the assessment tools used, as well as the total number, frequency, and duration of therapy sessions. Subsequently, a pilot study was conducted in a small group, including experienced hand therapists with over 20 years of experience, to evaluate the clarity of the questions and identify potential issues. Based on the feedback received, modifications were made to enhance the survey. To increase the flexibility of the study, an “Other, please specify” option was added to questions 2 (How many years of experience do you have in the field of hand therapy?), 3 (What type of institution do you work in?), 8 (What are your primary considerations when selecting a rehabilitation protocol?), 9 (Which complications do you observe most frequently?), 11 (How many days per week do you treat patients?), 12 (What is the average duration of a treatment session?), and 13 (How many total sessions do your patients typically receive?). Although various predefined response options were provided for each of these questions, the inclusion of this additional option was deemed necessary due to the wide variability in potential answers depending on the therapist, institution, and other contextual factors. The survey included questions related to professional background, such as occupation (physiotherapist, occupational therapist, academician), years of experience in the field of hand therapy, and level of education. Additionally, it inquired about rehabilitation practices, including the most frequently preferred protocol, assessment methods used, common complications encountered, and treatment duration (Supplementary file 1).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sakarya University of Applied Sciences (Approval date: 20.02.2025, Approval number: 53/03). Before data collection, the researchers explained to the participants the purpose of the study, that voluntary participation was essential, that anonymity was guaranteed, and that their data would be used only for this study. Informed consent was taken from all participants. The patients were also allowed to withdraw from the study any time without stating any reason. The Declaration of Helsinki was adhered to throughout all phases of this study.

Data collection process

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval, the survey link was shared in the Hand Therapists Association WhatsApp group, which consists of 117 members. In order to enhance the response rate, reminder messages were sent to members at two different time points, and the survey remained open for approximately one and a half months (February 21, 2025 – April 1, 2025). The survey did not include personal information such as name, surname, or gender, and the results were recorded anonymously.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0. The percentage of each response was calculated for each question, and for questions allowing multiple responses, the frequency (N) of each selected option was reported. No power analysis was conducted in this study, as the goal was to reach therapists primarily working in the field of hand rehabilitation in Turkey country. This objective was achieved by sharing the survey in the Hand Therapists Association WhatsApp group. There were 117 individuals who were registered with the association and also members of the WhatsApp group. The study aimed to achieve the maximum response rate.

Results

This study was completed with the participation of 60 therapists. The response rate for the survey sent to the Turkiye Hand Therapists Association whatsapp group, which consists of 117 members, was 51.28%. Of the survey participants, 68.3% (41/60) were physiotherapists, 20% (12/60) were academicians, and 11.7% (7/60) were occupational therapists. Half of the participants (50%, 30/60) reported having 0–5 years of experience. Across all professional groups, the highest participation was among individuals with 0–5 years of experience. The highest rate of participants with over 20 years of experience belonged to the academic profession group (8.33%, 1/12). Among participants with 16–20 years of experience, physiotherapists were the largest professional group (19.5%, 8/41). There were no occupational therapy participants with more than 10 years of experience. Half of all participants worked in public institutions, while the other half worked in private institutions/organizations. Among the professional groups, only more than half of physiotherapists (63.4%, 26/41) worked in private institutions/organizations.

Among the participants, 48.3% (29/60) held a bachelor’s degree, 28.3% (17/60) had a master’s degree, and 23.3% (14/60) had a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD). In fact, more than half of the participants (51.6%, 31/60) had a postgraduate degree. The highest education level was observed among academicians, with 75% (9/12) holding a PhD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of therapist

| Physiotherapist n = 41 |

Academic n = 12 |

Occupational therapist n = 7 |

Total n = 60 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience (%) | ||||

| 0–5 years | 51 | 33 | 71 | 50 |

| 6–10 years | 10 | 25 | 29 | 15 |

| 11–15 year | 12 | 17 | 12 | |

| 16–20 years | 20 | 17 | 17 | |

| 20+ years | 7 | 8 | 7 | |

| Institution (%) | ||||

| State | 37 | 83 | 71 | 50 |

| Private | 63 | 17 | 29 | 50 |

| Education level (%) | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 63 | 8 | 9 | 48 |

| Master’s degree | 32 | 17 | 29 | 28 |

| Doctor of Philosophy | 5 | 75 | 43 | 23 |

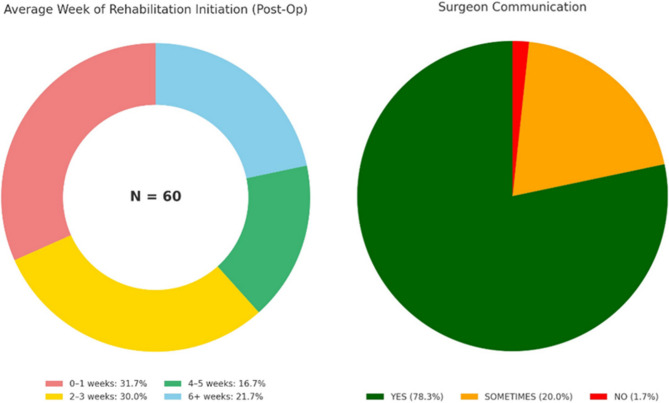

According to the therapists’ responses, the most common time for starting rehabilitation after flexor tendon repair was post-operative weeks 0–1 (31.7%, 19/60), while the least common time was post-operative weeks 6 and beyond (16.7%, 10/60). Other responses included 2–3 weeks (30%, 18/60) and 6 weeks or later (21.7%, 13/60).

Among the therapists participating in the study, 78.3% (47/60) reported having the opportunity to communicate with the surgeon, 20% (12/60) indicated that they sometimes had the opportunity to communicate with the surgeon, and 1.7% (1/60) reported not having the opportunity to communicate with the surgeon (Fig. 1). Additionally, the therapists reported that 21.6% (13/60) of the repairs were performed by orthopedic surgeons, while 78.4% (47/60) were performed by hand surgeons.

Fig. 1.

Timing of rehabilitation initiation and communication with the surgeon

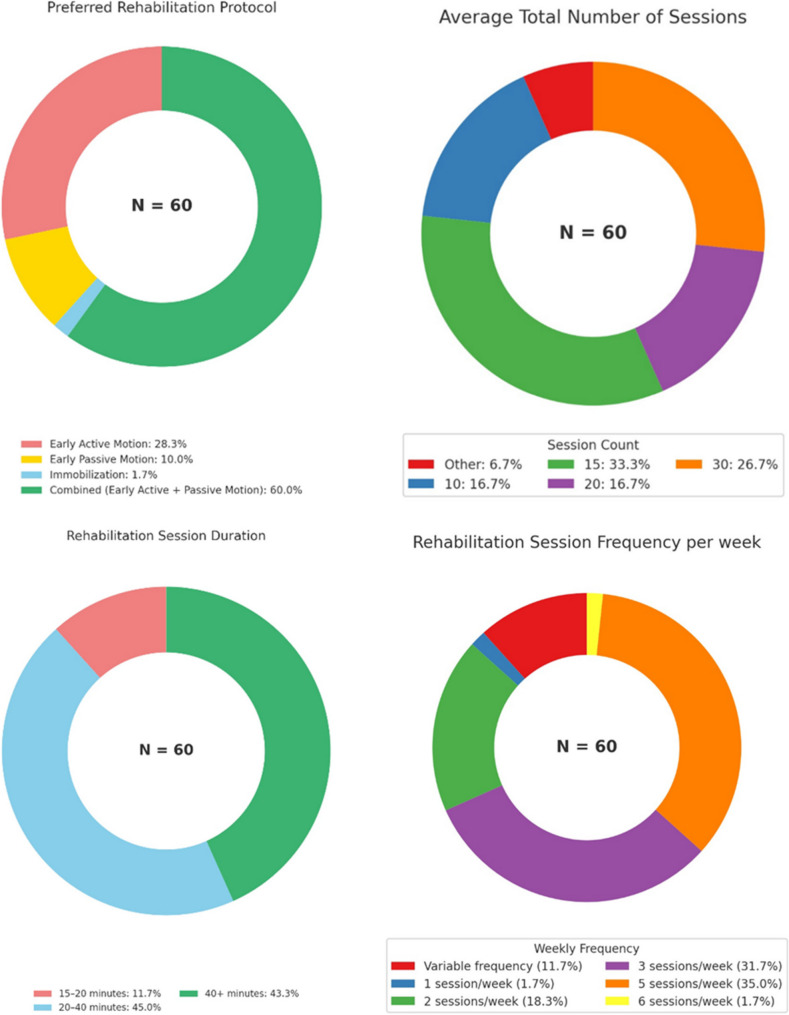

The rehabilitation protocol most preferred by therapists was a combination of early active and early passive motions. The preferences of therapists for rehabilitation protocols, in order, were combined (60%, 36/60), early active motion (28.3%, 17/60), early passive motion (10%, 6/60), and immobilization (1.7%, 1/60).

Most therapists (33.3%, 20/60) reported administering a total of 15 rehabilitation sessions following flexor tendon repair. Other therapists reported administering 30 sessions (26.7%, 16/60), 20 sessions (16.7%, 10/60), 10 sessions (16.7%, 10/60), or selected “Other” (6.7%, 4/60). The “Other” responses included statements such as “until recovery” or “depending on the condition of the hand.”

Most therapists reported that the duration of a session was typically between 20 and 40 min (45%, 27/60). Additionally, 43.3% (26/60) of therapists indicated that the session duration was longer than 40 min. A minority (11.7%, 7/60) reported that the session duration was between 15 and 20 min.

When the frequency of sessions was surveyed, the responses varied significantly. 35% of therapists (21/60) reported 5 sessions per week, 31.6% (19/60) reported 3 sessions per week, 18.3% (11/60) reported 2 sessions per week, 1.6% (1/60) reported 1 session per week, 1.6% (1/60) reported 6 sessions per week, and 11.6% (7/60) reported that the number of sessions per week varied (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of rehabilitation

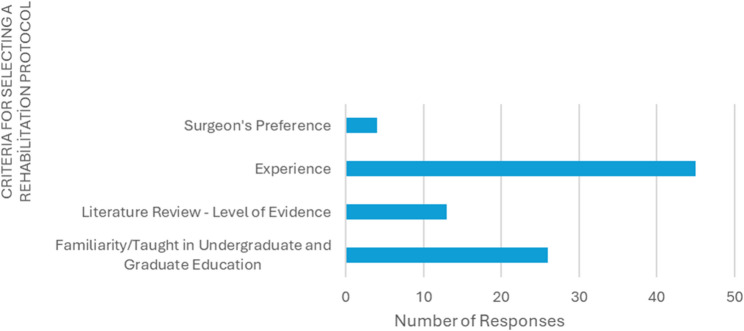

In response to the question about what therapists relied on when selecting a rehabilitation protocol, the most common answer was experience (44/60). This was followed by familiarity/what was taught in undergraduate and graduate education (26/60), literature review - level of evidence (13/60), and the surgeon’s decision (3/60) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Criteria for selecting a rehabilitation protocol

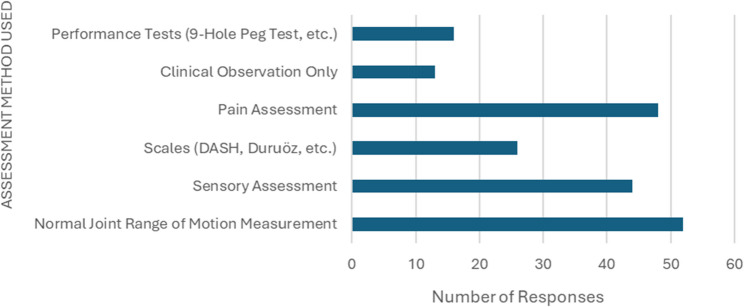

The most used assessment method in rehabilitation was the normal joint range of motion measurement (51/60). This was followed by pain assessment (47/60), sensory assessment (43/60), scales (DASH, Duruöz, etc.) (25/60), performance tests (9-Hole Peg Test, etc.) (15/60), and clinical observation only (12/60) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Assessment method used

The most common complication encountered by therapists was adhesion (44/60), while the least common complication was re-rupture (9/60). Contracture/joint stiffness was the second most frequently observed complication after adhesion (39/60) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Most common complications

Discussion

The demographic profile of the participating therapists indicates a relatively young workforce in terms of their professional experience in hand therapy. This may reflect the increasing interest and involvement in the field of hand rehabilitation in Turkey following graduation [20]. Furthermore, the fact that more than half of the participants hold postgraduate degrees suggests that clinical and academic efforts may be progressing in parallel, potentially creating a strong foundation for interdisciplinary collaboration. In this study, half of the therapists work in public institutions, while the other half work in the private sector. However, these findings are based on a small sample of only 60 therapists, and the sample size may not fully represent all hand therapists in Turkey.

Some experts are concerned that starting rehabilitation early may increase the risk of tendon rupture [25], while others believe that a strong suture will allow for early mobility [26, 27]. In a survey study conducted by Bigorre et al. on surgeons, it was found that 28% of surgeons did not begin rehabilitation until the 7th day post-repair, and 20% waited until the 15th day. This means that nearly half of the surgeons recommended starting rehabilitation within the first two weeks post-repair [21]. In the present study, most therapists (%61.7, 37/60) reported starting rehabilitation in the early period (%31.7 within 0–1 week, %30 within 2–3 weeks). One of the most striking reasons for the early initiation of rehabilitation. In the present study study could be the therapists’ opportunity for communication with the surgeon. This is supported by the fact that 78.3% (47/60) of the therapists in the present study reported having the opportunity to communicate with the surgeon. Previous studies have shown that open communication between therapists and surgeons shortens the time to begin therapy. This is because it allows for both the patient’s referral to therapy and the therapist to feel more confident in their approach [25].

The choice of rehabilitation protocol following flexor tendon repair is another controversial topic. With advancements in surgery, current literature is shifting towards early mobilization protocols [11, 12]. However, early mobilization protocols are quite diverse in themselves, and there is still no established gold standard. Studies generally suggest that passive mobilization protocols, compared to early active mobilization protocols, have a lower risk of rupture but result in greater joint motion limitations [5, 28]. In the present study, in line with current literature, the trend among therapists in Turkey was towards early mobilization protocols. The majority combined early active and early passive mobilization, while a significant proportion used only early active mobilization. Several factors, such as the surgical procedure, the strength of the repair, the patient’s compliance, and the therapist’s experience, are taken into account when selecting a protocol [11]. Indeed, in the present study, most therapists indicated that they consider their experience when choosing a protocol. Although half of the participating therapists have 0–5 years of experience, the frequent exchange of knowledge and experience in the field of hand therapy in Turkey may be one reason why experience plays a significant role in protocol selection. Additionally, despite having fewer years of experience, the number of flexor tendon repair patients treated annually may be high. Many therapists who are members of the Hand Therapists Association in Turkey are professionals who have proven themselves to the surgeons they collaborate with, and therefore, they may exercise a considerable degree of experience-based autonomy when selecting treatment approaches. Not investigating the number of patients treated annually who have undergone flexor tendon repair is a limitation of our study. The success of rehabilitation is not solely determined by which protocol is selected. The success of the repair associated injuries, the severity of the trauma, the quality of the rehabilitation applied, and the patient’s compliance are also crucial factors for the success of rehabilitation. Especially, the patient’s adherence to precautions, commitment to home exercises, and participation in sessions significantly influence the effectiveness of the treatment, independent of the protocol applied [12, 29, 30]. Based on the responses from the 60 therapists in our survey, there appears to be a preference for early active mobilization and combined protocols, which aligns with current evidence.

In the present study, the most frequently reported total number of sessions was 15, followed by 30 sessions. The total number of sessions is often influenced more by national health insurance policies than by therapist discretion. The duration of each session was reported to be mostly longer than 40 min. The most common response was a rehabilitation frequency of five sessions per week, which again appears to be influenced by healthcare system policies. However, it is evident that there is no consensus regarding the optimal frequency of rehabilitation.

In the present study, the most used outcome measure by therapists was the assessment of normal joint range of motion, followed by pain and sensory evaluations. Since flexor tendon injuries often cause finger movement limitations, they lead to impaired hand function and reduced quality of life, making range of motion assessment particularly important [14]. However, studies show that range of motion does not always align with functional outcomes, as functionality is influenced by multiple factors [31].

Our findings indicate that tools measuring functionality and performance were used less frequently, possibly due to time constraints, limited resources, or insufficient training. To address these issues, it is recommended to implement in-service training programs specifically for clinicians, develop guidelines on the use of standardized assessment tools, and organize educational seminars or workshops to highlight the importance of these tools in clinical practice. Additionally, more comprehensive theoretical and practical content related to functional and performance-based assessments could be incorporated into educational curricula. Such initiatives may encourage therapists to use functional and performance-based measurement tools more widely and effectively.

Flexor tendon injuries are often accompanied by digital nerve injuries due to their anatomical proximity [32]. Therefore, sensory evaluation along the finger is essential, and most therapists in the present study reported performing it. Although pain pathways can be sensitized due to surgical trauma, minimally invasive techniques have reduced postoperative pain [33]. Still, pain remains one of the most frequently assessed parameters, likely due to its biopsychosocial impact.

Although there have been advancements in the repair and rehabilitation of flexor tendon injuries in recent years, complications still occur. Potential complications include rupture, adhesion, contracture, revision surgeries, delayed wound healing, pulley insufficiency, triggering, persistent pain, gap formation, sensory loss, quadriga, swan neck and lumbrical plus deformity [13, 14, 17]. In the present study, the most frequently reported complication was adhesion. Adhesion formation is the most common and one of the most challenging complications to prevent in flexor tendon injuries [34]. Current approaches to flexor tendon repair advocate for early mobilization; however, factors such as pain, swelling, and patient compliance may still hinder postoperative rehabilitation efforts [35]. On the other hand, recent studies have increasingly focused on pharmacological agents to prevent adhesion formation, and these investigations show promising potential [35, 36]. Following adhesion, the second most frequently reported complication by therapists was contracture/joint stiffness. Joint contractures can also be prevented through proper splinting—in a position of 0–30° wrist flexion, 50–90° MCP flexion, and full IP joint extension—and the implementation of early rehabilitation protocols [17, 37]. Joint stiffness is considered an early-stage complication [38]. In the present study, therapists may not have had the opportunity to evaluate most patients in the long term and may have considered joint stiffness as an early-stage complication. The third most frequently reported complication was re-rupture. Even though the majority of therapists in the present study implemented protocols incorporating early active mobilization and combination approaches, and initiated rehabilitation in the early postoperative phase, re-rupture did not emerge as a commonly encountered complication. This finding may be attributed to the adherence to contemporary surgical and rehabilitation principles for flexor tendon repair, which have substantially mitigated the risk of tendon re-rupture in clinical practice [39].

Limitations

The primary limitation of our study is the number; therefore, there is a risk of bias. Although the findings obtained are valuable, they may not fully reflect the overall national landscape of hand rehabilitation practices in Turkey. Also, in Turkey, the title of certified hand therapist is not officially recognized. Although the Hand Therapists Association (http://www.elterapistleridernegi.org/) was established in 2004 to bring together therapists working in the field of hand therapy, not all professionals in this field may be members of the association. While the number of therapists working in hand therapy is lower compared to other rehabilitation fields in Turkey, the exact number remains unknown. One limitation of our study is the exclusion of certain technical aspects from the survey, such as splint design and duration, as well as the average number of tendon injury patients treated per year.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is an increasing tendency toward early mobilization, particularly in alignment with global trends, in the rehabilitation following flexor tendon repair in Turkey. Rehabilitation is predominantly initiated within the first three weeks after tendon repair. Most hand rehabilitation therapists in Turkey have the opportunity to communicate with surgeons. However, there is considerable variation among therapists regarding parameters such as the frequency, duration, and total number of rehabilitation sessions. In the context of hand rehabilitation in Turkey, clinical experience plays a critical role in therapists’ decision-making processes. Adhesion was identified as the most frequently observed complication. The originality of this study lies in being the first to evaluate the current approaches of hand therapists in Turkey toward flexor tendon injuries. It is recommended that future studies be conducted with larger and more representative samples of therapists involved in post–flexor tendon repair rehabilitation. Furthermore, comparative analyses should be included to encourage standardized, evidence-based approaches in the rehabilitation of flexor tendon injuries.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Salime Altunbay and Beray Keleşoğlu Işın for distributing the online survey.

Authors’ contributions

Seher Karacam: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Birgul Dingirdan Gultekinler: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Sakarya University of Applied Sciences (Approval date: 20.02.2025, Approval number: 53/03). Before data collection, the researchers explained to the participants the purpose of the study, that voluntary participation was essential, that anonymity was guaranteed, and that their data would be used only for this study. Informed consent was taken from all participants. The patients were also allowed to withdraw from the study any time without stating any reason. The Declaration of Helsinki was adhered to throughout all phases of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pearce O, et al. Flexor tendon injuries: repair & rehabilitation. Injury. 2021;52(8):2053–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens KA, Caruso JC, Fallahi AKM, Patiño JM. Flexor Tendon Lacerations. Tampa; 2018. [PubMed]

- 3.De Jong JP, et al. The incidence of acute traumatic tendon injuries in the hand and wrist: a 10-year population-based study. Clin Orthop Surg. 2014;6(2): 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G, Rothrauff BB, Tuan RS. Tendon and ligament regeneration and repair: clinical relevance and developmental paradigm. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today Rev. 2013;99(3):203–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutsky KF, Giang EL, Matzon JL. Flexor tendon injury, repair and rehabilitation. Orthop Clin. 2015;46(1):67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starr HM, et al. Flexor tendon repair rehabilitation protocols: a systematic review. J Hand Surg. 2013;38(9):1712–7. e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue R, et al. Current clinical opinion on surgical approaches and rehabilitation of hand flexor tendon injury—a questionnaire study. Front Med Technol. 2024;6: 1269861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw AV, et al. Outcome measurement in adult flexor tendon injury: a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2022;75(4):1455–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis D. Tendon rehabilitation: factors affecting outcomes and current concepts. Curr Orthop Pract. 2018;29(2):100–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho SLD, Chow CSE. Comparison of Kleinert versus saint John protocol in zone I/II flexor tendon injuries: a retrospective study. J Orthop Trauma Rehabil. 2024. 10.1177/22104917241256658. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skirven TM, DeTullio LM. Therapy after flexor tendon repair. Hand Clin. 2023;39(2):181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesney A, et al. Systematic review of flexor tendon rehabilitation protocols in zone II of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(4):1583–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aydemir K, Yazıcıoğlu K. Üst Ekstremite Tendon Yaralanmalarının Rehabilitasyonu. J Phys Med Rehab Sci. 2011;14:1–6.

- 14.Peters SE, Jha B, Ross M. Rehabilitation following surgery for flexor tendon injuries of the hand. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;19(1):1–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gibson PD, Sobol GL, Ahmed IH. Zone II flexor tendon repairs in the United States: trends in current management. J Hand Surg. 2017;42(2):e99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renberg M, et al. Range of motion following flexor tendon repair: comparing active flexion and extension with passive flexion using rubber bands followed by active extension. J Hand Surg. 2024;49(12):1203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lilly SI, Messer TM. Complications after treatment of flexor tendon injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(7):387–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YJ, Ryoo HJ, Shim H-S. Prevention of postoperative adhesions after flexor tendon repair with acellular dermal matrix in zones III, IV, and V of the hand: a randomized controlled (CONSORT-compliant) trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(3):e28630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Titan AL, et al. Flexor tendon: development, healing, adhesion formation, and contributing growth factors. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(4):639e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sığırtmaç İC, Karadağ B, Öksüz Ç. Ergoterapist ve fizyoterapist Adaylarının El Terapisi Alanında Öz yeterliliklerinin incelenmesi. Ergoterapi Rehabil Dergisi. 2020;8(2):153–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigorre N, et al. Primary flexor tendons repair in zone 2: current trends with GEMMSOR survey results. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2018;37(5):281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unsal SS, Yildirim T, Armangil M. Comparison of surgical trends in zone 2 flexor tendon repair between Turkish and international surgeons. Actaorthop Traumatol Turc. 2019;53(474–7):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarron L, et al. Current rehabilitation recommendations following primary triangular fibrocartilage complex foveal repair surgery: a survey of Australian hand therapists. J Hand Ther. 2023;36(4):932–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadakia Z, et al. How is range of motion of the fingers measured in hand therapy practice? A survey study. Hand Ther. 2024;29(3):112–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kammien AJ, Hu KG, Yu C, Grauer JN, Colen DL. Hand therapy utilization following digital flexor tendon repair: Trends, timing, predictive factors, and association with reoperation. J Hand Ther. 2025. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Wu Y, Tang J. Recent developments in flexor tendon repair techniques and factors influencing strength of the tendon repair. J Hand Surg (European Volume). 2014;39(1):6–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chauhan A, Palmer BA, Merrell GA. Flexor tendon repairs: techniques, eponyms, and evidence. J Hand Surg. 2014;39(9):1846–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starr HM, et al. Flexor tendon repair rehabilitation protocols: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38A:1712–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Frueh FS, et al. Primary flexor tendon repair in zones 1 and 2: early passive mobilization versus controlled active motion. J Hand Surg. 2014;39(7):1344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin M, et al. An overview of the management of flexor tendon injuries. Open Orthop J. 2012;6(Suppl 1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stenekes MW, et al. Cerebral consequences of dynamic immobilisation after primary digital flexor tendon repair. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2010;63(12):1953–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkatramani H, et al. Flexor tendon injuries. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10(5):853–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng J, Liu B, Gong G. The therapeutic effects of the minimally invasive repair of hand flexor tendon injuries. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2019;12(12):13706–11. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Civan O, et al. Tenolysis rate after zone 2 flexor tendon repairs. Joint Dis Related Surg. 2020;31(281–5):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vinitpairot C, et al. Current trends in the prevention of adhesions after zone 2 flexor tendon repair. J Orthop Research®. 2024;42(10):2149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia Q, et al. Risk factors associated with tendon adhesions after hand tendon repair. Front Surg. 2023;10: 1121892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulos N, Bozentka DJ. Management of complications of flexor tendon injuries. Hand Clin. 2015;31(2):293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wimbiscus M, et al. Advances and challenges in zone 2 flexor tendon repairs. Ann Plast Surg. 2024;93(6S):S138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, Tang JB. Complications of flexor tendon repair. J Hand Surg Eur. 2024;49(158–66):2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.