Abstract

Background

Feline morbillivirus (FeMV) has been associated with renal pathology in cats; however, the specific pathological alterations caused by FeMV infection remain controversial. This study aimed to investigate histopathological changes, viral localization, and apoptotic activity in the kidneys of FeMV-infected cats.

Methods

Kidney tissues from 150 deceased cats with suspected or confirmed chronic kidney disease (CKD) were screened for FeMV using conventional reverse-transcription PCR (cRT-PCR). Positive cases were genotyped and quantified for viral load using reverse-transcription digital PCR (RT-dPCR). A control group of nine FeMV-negative kidneys with CKD was included for comparison. Histological evaluation was conducted using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), and Masson’s trichrome staining. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH) were employed to localize viral antigens and assess expression of apoptotic markers, including cleaved caspase-3 (cCasp3), B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and BCL-2–associated X protein (BAX).

Results

FeMV RNA was detected in 6% (9/150) of kidneys, all classified as genotype 1. Histological findings in FeMV-positive cases included eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, lymphoplasmacytic tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) and varying degrees of fibrosis. FeMV antigens were localized in the renal tubular epithelial cells. Statistically, cCasp3 expression (P = 0.005) and interstitial fibrosis (P = 0.040) were significantly higher in FeMV-positive cases than in FeMV-negative controls. No significant differences were observed for TIN, BAX, or BCL-2 expression (P > 0.05). Among FeMV-positive cases, viral load was significantly associated with cCasp3 expression (P = 0.049), but not with TIN, fibrosis, BAX, or BCL-2 expression. Spearman’s correlation revealed a strong positive correlation between viral load and cCasp3 expression (ρ = 0.8222, P = 0.007).

Conclusions

FeMV infection in cats was associated with increased caspase-3–mediated apoptotic activity and interstitial fibrosis in kidney tissue, particularly in cases with higher viral loads. While these findings suggest a possible role for FeMV in renal injury, the absence of consistent associations with other apoptotic markers and inflammatory parameters indicates that additional factors may contribute to disease progression. Further studies, including longitudinal and experimental investigations, are needed to clarify the pathogenic mechanisms and the clinical relevance of FeMV in feline kidney disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12917-025-04953-z.

Keywords: Feline morbillivirus, Kidney pathology, Apoptosis, Chronic kidney disease, Caspase-3

Background

Feline morbillivirus (FeMV), a member of the genus Morbillivirus in the Paramyxoviridae family, was first discovered in the urine of stray cats in Hong Kong in 2012 [1]. Since its discovery, FeMV has been reported in various countries across Asia, Europe, and the United States [2–5]. To date, two genotypes of FeMV have been recognized: genotype 1 (FeMV-1) and genotype 2 (FeMV-2) [1, 6]. FeMV-1 is the more prevalent genotype and has been found in domestic cats in Hong Kong, Japan, China, Thailand, Malaysia, Turkey, Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom [1, 4, 7–13]. In contrast, FeMV-2 has been reported in Germany and serological evidence of FeMV-2 has been identified in domestic cats in Chile [6, 14]. Additionally, FeMV infection has been documented in wild felids, including black leopard (Panthera pardus) [15] and guignas (Leopardus guigna) [16], as well as in non-felid species such as domestic dogs [17] and white-eared opossum (Didelphis albiventris) [18], suggesting a broad-range and cross-species transmission potential.

Numerous studies have been investigated the presence of FeMV in various clinical samples and tissues. FeMV is most frequently detected in urine and kidneys of infected cats [9, 11, 15]. The infection exhibits renal epitheliotropism, characterized by eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (ICIBs) within the cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells [19]. Although FeMV genomic material is predominantly localized in the kidney [8, 20], the virus likely spreads to other tissues via hematogenous dissemination. Accordingly, FeMV has been detected and/or localized in various organs such as the brain, lungs, spleen, intestine, liver, lymph nodes, and urinary bladder [5, 6, 8, 17, 19, 21].

Several studies have suggested a potential association between FeMV infection and chronic kidney disease (CKD) in cats, particularly in cases marked by the presence of tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) [1] and renal interstitial fibrosis [22]. Interestingly, FeMV genetic materials and antibodies have been identified in both cats with renal diseases and in clinically healthy individuals [1, 2, 4, 8, 9, 19, 23, 24]. While previous research indicated a link between FeMV infection and renal interstitial fibrosis, this association may have been influenced by the age distribution of the sampled populations, which largely consisted of mature adult and senior cats [22]. The detection of FeMV in both diseased and asymptomatic cats raises important questions regarding its pathological roles and the specific renal alterations.

Paramyxoviruses are known for their ability to modulate apoptotic processes in infected tissues [25]. Members of the family Paramyxoviridae, such as measles virus and Sendai virus, have been shown to induce apoptosis, whereas mumps virus has been reported to suppress apoptotic activity in its infected cells [26–28]. In the context of FeMV infection, a previous study has documented increased apoptotic activity in infected renal tissue [29]. However, it remains uncertain whether FeMV induces apoptosis through caspase-dependent or caspase-independent pathways, particularly since renal tissue damage—regardless of etiology—can inherently trigger apoptosis [30].

In this study, we examined the pathological effects of naturally occurring FeMV-1 infection in domestic cats, with a specific focus on its association with interstitial inflammation, fibrosis, and apoptosis. We also assessed viral localization using ISH and viral protein expression using IHC. Our objective was to characterize the tissue distribution of FeMV-1 in the kidney and evaluate its potential contribution to virus-induced renal injury.

Results

Animal data of FeMV-detected kidneys and viral quantification

Out of 150 investigated kidneys obtained from 150 cats, nine kidney samples (6.0%) tested positive for FeMV by cRT-PCR, and subsequent genetic sequencing confirmed all positive cases as FeMV genotype 1 (FeMV-1) (Table 1). All FeMV-positive cats were domestic shorthairs, with seven cases classified as young adult (77.8%) and two cases as seniors (22.2%). The two senior cats (case 3 and 4) showed sclerotic kidneys. Additionally, nine FeMV-negative cats with CKD, confirmed by both FeMV PCR and broad feline viral PCR screening, were included as control cases (Supplementary Table S1). Details regarding the reason for necropsy are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Clinical data, including blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels were available for only 4 out of the 9 FeMV-positive cats (Table 1). Selective viral screening revealed that 4 out of the 9 FeMV-positive cats (44.4%) were co-infected with feline leukemia virus (FeLV), while no evidence of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV), feline coronavirus (FCoV), or feline calicivirus (FCV) was found (Table 1). FeMV load in of FeMV-positive kidneys was quantified using probed-based RT-dPCR. FeMV copy numbers ranged from 0.4 × 101 to 9.14 × 104 copies/µL (Table 1). The highest viral load (9.14 × 10⁴ copies/µL) was observed in a 10-year-old senior cat (case 3).

Table 1.

Essential clinical information, feline morbillivirus (FeMV) copies number and other viral screening

| Case No. | Cat No. | Age (years) | BUN (mg%)a | Creatinine (mg%)a | FeMV load (copies/ µL) | Percentage of homologyb | Molecular viral screening | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeLV | FIV | FCoV | FCV | FPLV | |||||||

| 1 | K014 | 3 | 50.4 | 3 | 0.7 × 101 | 100% | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | K025 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1.5 × 101 | 100% | + | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | K036 | 10 | N/A | N/A | 9.14 × 104 | 98.8% | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | K052 | 16 | 36 | 1.7 | 8.7 × 101 | 98.72% | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | K075 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 8.3 × 101 | 98.77% | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | K110 | 3 | 32.3 | 1.3 | 0.5 × 101 | 100% | + | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | K134 | 2 | N/A | N/A | 4.3 × 102 | 100% | + | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | K135 | 3 | 27.3 | 1.4 | 0.4 × 101 | 100% | + | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | K138 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 5.3 × 101 | 98.73% | - | - | - | - | - |

a Reference range: BUN 10–30 mg%; Creatinine = 0.8-2.0 mg%

b Percentage of homology with FmoPV-Thai-U16, except cat no.K052 showed homology score with FmoPV/TH/A48

Abbreviations: BUN = blood urea nitrogen; FeLV = feline leukemia virus; FIV = feline immunodeficiency virus; FCoV = feline coronavirus; FCV = feline calicivirus; FPLV = feline panleukopenia virus; + = positive; - = negative; N/A = no data available

Histological and morphological analyses of FeMV-positive kidneys

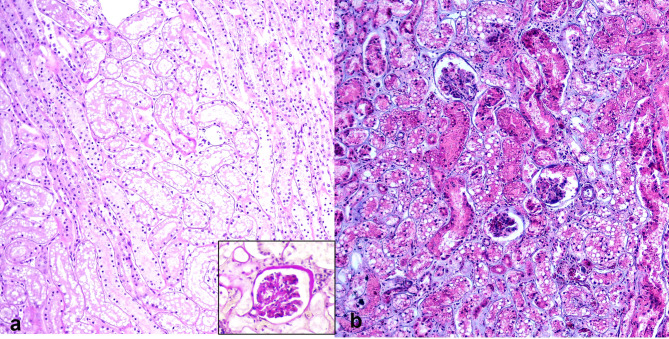

All kidneys testing positive for FeMV by RT-dPCR showed the presence of eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (ICIBs) within the renal tubular epithelial cells (Figs. 1A-C). The severity of ICIB presentation varied among cases and was categorized as mild, moderate, or severe (Table 2). Tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), characterized by mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltration, was consistently observed across all FeMV-positive cases (Supplementary Table S1). Although interstitial nephritis typically affects the renal cortex, four cases (cases 3, 4, 5, and 6) exhibited inflammatory infiltrates extending into the medulla (Table 2). Case 3, which had the highest FeMV viral load also displayed features of chronic renal pathology. Cases 6 and 7, both co-infected with FeLV, showed histological evidence of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining confirmed the integrity of the glomerular capillary and tubular epithelial basement membranes in these cases (Table 2; Fig. 2). Mild to severe MPGN was observed in five of the nine FeMV-positive cases. Two of these (cases 6 and 7) were co-infected with FeLV and exhibited mild MPGN. Notably, case 7 also presented with acute pulmonary edema at the time of necropsy (Supplementary Table S2). Interstitial fibrosis was observed in all FeMV-positive cases except for case 1. The severity of fibrosis ranged from mild to moderate, with moderate fibrosis prominent in cases 2, 4, 5, and 7 (Table 2; Fig. 2).

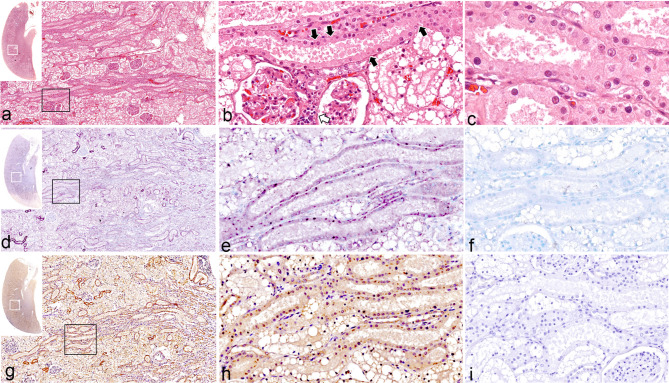

Fig. 1.

Feline morbillivirus (FeMV) infection. Kidney. Case 7. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) (a-c), in situ hybridization (ISH) (d-f), immunohistochemistry (IHC) (g-i). Insets indicate an overview of kidney section of each investigation panel, and white squares indicate areas where examined. Black squares indicate a higher magnification where presented in a subsequent figure. (a) Multifocal renal tubular necrosis. (b) Focal lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis (white arrow). (c) Renal tubular necrosis with eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (ICIBs). (d) Multifocal labelling (purple chromogens) of FeMV probe in renal tubules. (e) ISH signals label ICIBs of renal tubular epithelial cells. (f) No hybridization signal presents in the slide incubation with an unrelated probe. (g) FeMV matrix antigens (brown chromogen) are identified in the cytoplasm of renal tubules. (h) The IHC-against FeMV labels the ICIBs. (i) There is no reaction presented in the slide incubation with normal rabbit IgG antibody

Table 2.

Summary of pathological alterations, special stains, apoptotic activity, and viral localization of FeMV-infected kidney

| Case No. | Cat No. | Gross | H&E | PAS | MT | Apoptotic | IHC | ISH | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICIBsa | Area of mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration (scoring)b | Other lesions | Glomerulus lesion | Area of desquamated basement membrane | Area of renal fibrosis (scoring)b | BCL2 (scoring)b | BAX (scoring)b | Cleaved caspase-3 (scoring)b | |||||

| 1 | K014 | NRL | ++ | C (2) | - | MPGN | C, M | − (0) | C (1) | − (0) | − (0) | - | C |

| 2 | K025 | NRL | ++ | C (1) | - | - | C | C (2.5) | C, M, P (3) | C, M (3) | C (1) | C, M,P | C, M,P |

| 3 | K036 | Mild irregular surface | + | C, M,P (2) | Vacuolated cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells | - | C, M,P | C (0.7) | C, M, P (3) | C (2.7) | C− (2) | C, M,P | C, M,P |

| 4 | K052 | Mild irregular surface | + | C, M (2) | Vacuolated cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells | MPGN | C, M,P | C, M,P (1.5) | C, M (2) | C (1.3) | C (2) | C.M | C, M,P |

| 5 | K075 | NRL | ++ | C, M (1) | - | MPGN | C, M,P | C (2.5) | C, M (2) | C, M (3.3) | C (2) | C, M,P | C, M,P |

| 6 | K110 | NRL | ++ | C, M (1) | - | MPGN | C | C (1) | C, M, P (3) | C (3.3) | C (1) | C, M,P | C, M,P |

| 7 | K134 | NRL | +++ | C (1) | - | MPGN | C | C (1) | C, M (2) | C (3.3) | C (2) | C, M,P | C, M,P |

| 8 | K135 | NRL | +++ | C (1) | - | - | C, M,P | C (3.3) | C (1) | C (2.3) | C (1) | C, M,P | C, M,P |

| 9 | K138 | NRL | +++ | C (1) | - | - | C, M,P | C (0.7) | C (2) | C (1.7) | C (1) | - | C, M,P |

aDegree of ICIBs in tubular epithelial cells: (+) mild; (++) moderate; (+++) severe

b Scoring of interstitial inflammation, fibrosis, and apoptotic activity is equal to means value of semi-quantitative scoring

Abbreviations: H&E = hematoxylin & eosin stain; PAS = Periodic acid Schiff stain; MT = Masson trichrome stain; IHC = immunohistochemistry; ISH = in situ hybridization; C = cortical area; M = medullar area; P = pelvis area; NRL = no remarkable lesion; MPGN = membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; ICIBs = intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies

Fig. 2.

Feline morbillivirus (FeMV) infection. Kidney. Cats. (a) Tubular integrity represented by intact tubular basement membrane. Inset: the presence of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN). Case 5. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). (b) Renal interstitial fibrosis. Fibrous tissue infiltrating renal parenchyma with minimal tubular atrophy. Case 4. Masson’s Trichrome (MT)

FeMV localization and distribution in infected kidneys

Among the nine FeMV-positive cases, IHC targeting the FeMV M protein detected positive immunostaining signals in seven cases. The remaining two cases (cases 1 and 9) showed no detectable M protein expression by IHC. However, ISH targeting a partial genomic segment of the FeMV L gene revealed FeMV localization in all nine cases, consistent with the molecular detection results by RT-dPCR. In affected kidneys, FeMV was distributed across all anatomical regions, as summarized in Table 2. The IHC signals were most prominent in the cortical and medullar areas.

Both ISH and IHC assays demonstrated FeMV localization along the plasma membrane and within the cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells (Fig. 1d-e and g-h). Interestingly, nuclear signals were also observed in some tubular epithelial cells, most notably in case 5 (Fig. 3a-b). No FeMV-specific immunostaining or in situ signal was observed on negative control slides processed with non-specific antibodies or with unrelated probes (Figs. 1f & i). To validate the negative FeMV PCR results in the control group, IHC for FeMV M protein was also performed. As expected, none of nine FeMV PCR-negative control kidneys exhibited any FeMV-specific IHC signals.

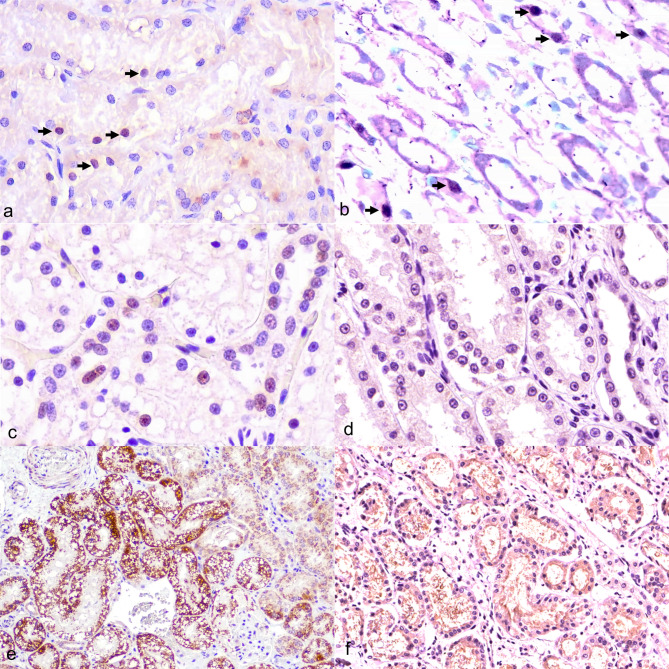

Fig. 3.

Feline morbillivirus (FeMV) infection. Kidney. Cat. (a) Nuclei of tubular epithelial cells exhibiting immunostaining signals against FeMV-M protein (arrows). Immunostaining is also present in the ICIBs of tubular epithelial cells. Case 5. Immunohistochemistry (IHC). (b) Intense in situ hybridization (ISH) signals observed in the nuclei of tubular epithelial cells. Case 5. ISH. (c) Immunostaining signal for cleaved caspase-3 (cCasp3) observed in the nuclei of epithelial cells. Case 5. IHC. (d) No immunostaining signal for cCasp3 detected in FeMV-negative kidney (control group) obtained from chronic kidney disease (CKD)-cat. Case 13. IHC. (e) Intense brown chromogen labelled BAX expression observed in the cytoplasm of tubular epithelial cells within intact tubules. Case 5. IHC. (f) Few chromogen deposits marking weak BCL-2 expression in a FeMV-positive case. Case 5. IHC

Apoptotic activity with FeMV co-localization

cCasp3 expression was observed in most FeMV-positive cases, except for case 1. Immunostaining for activated cCasp3 was detected in single or multiple renal tubular epithelial cells, predominantly in the cortical region of the kidney (Fig. 3c). cCasp3 activity was noted not only in proximal tubules containing the ICIBs, but also in tubules without visible ICIBs. No cCasp3 expression was detected in glomeruli. Furthermore, no cCasp3 immunostaining was observed in any FeMV-negative CKD control cases (Fig. 3d). Notably, co-localization of FeMV-1 antigen and caspase-3 was confirmed in cases 2, 4, 6, and 8 (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Feline morbillivirus (FeMV) infection. Kidney. Case 8. Dual labelling. (a) Co-labelling of apoptotic activities markers (cCasp3, purple chromogen) and FeMV-M protein (brown chromogen). The nucleus of renal epithelial cells displayed cCasp3 expression generating dark purple color, with slight cytoplasmic immunoreaction against the FeMV-M protein (inset). (b) Co-labelling of apoptotic activities markers (BAX, purple chromogen) and FeMV-M protein (brown chromogen). The cytoplasm of renal epithelial cells co-expressed BAX and FeMV-M protein, generating reddish-purple color in some tubules. Bars indicate 100 μm

BAX expression was detected in all FeMV-positive kidneys except case 1. Expression was primarily localized in the renal cortex, though in cases 2 and 5, it extended into to the medullary region area. Strong BAX expression was observed in tubules with intact basement membrane, particularly in case 5 (Fig. 3e). Interestingly, tubules with epithelial cell detachment also demonstrated prominent BAX expression. Co-localization of BAX and FeMV-1 was seen in all FeMV-positive cases, with the exception of case 1 (Fig. 4b). BCL-2 expression was observed in the cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells, predominantly in the cortical and medullary regions, with extension into the renal pelvis in some cases (cases 2, 3, and 6). Notably, BCL-2 expression was present in case 1, where BAX was absent. BCL-2 staining was generally more prominent in tubules with preserved structural integrity (Fig. 3f). In cases 5, 6, 7, and 8, BAX expression was greater than BCL-2 expression, while in case 2, the expression levels were comparable (Table 2). Similar patterns of BAX and BCL-2 expression were also observed in the FeMV-negative CKD control kidneys.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare histopathological and apoptotic parameters between FeMV-positive and FeMV-negative (control) groups. The analysis showed that cCasp3 expression (P = 0.005) and interstitial fibrosis (P = 0.040) were significantly higher in FeMV-positive cases. No significant differences were found for other parameters, including TIN, BAX, and BCL-2 expression (P > 0.05). Within the FeMV-positive group, the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a significant association between FeMV viral load and cCasp3 expression (P = 0.049). However, viral load was not significantly associated with TIN (P = 0.302), renal fibrosis (P = 0.469), BAX (P = 0.465), or BCL-2 expression (P = 0.165) (Table 3). To further examine these relationships, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was performed. A strong positive correlation was found between viral load and cCasp3 expression (ρ = 0.8222, P = 0.007), while no significant correlations were observed between viral load and other parameters (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of statistical analyses of viral load of FeMV-positive cats compared with semiquantitative scoring of histopathological parameters

| Histopathological parameters | Kruskal-Wallis test (P-value) | Spearman’s Correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho (ρ) | Spearman’s P-Value | ||

| Tubular interstitial inflammation (TIN) | 0.302 | 0.365 | 0.334 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 0.469 | -0.354 | 0.349 |

| BCL-2 | 0.165 | 0.321 | 0.400 |

| BAX activity | 0.465 | 0.136 | 0.728 |

| cCasp3 activity | 0.049* | 0.822 | 0.007* |

*P-value less than 0.05 is considered statistical significances

Discussion

Feline morbillivirus (FeMV) has been identified as a virus potentially associated with the onset of CKD in cats, marked by the presence of TIN [1]. In this study, FeMV-1 was detected in a small subset of feline kidney samples in Thailand, suggesting a relatively low prevalence of fatal FeMV-associated disease. However, the exact cause of death in these FeMV-positive cats could not be definitively determined. FeMV-1 was detected in the cat exhibiting lesions in kidneys, with a predominance in the young DSH cats. This finding aligns with findings from a 2021 study in Italy, where FeMV-1 genomic material was more frequently detected in young DSH cats (84.3%) [31]. Notably, FeMV-2 was not detected in any of samples in our study, further supporting previous reports that FeMV-1 is the more prevalent genotype across different geographic regions [4, 6, 8, 10].

Selective viral screening revealed that four FeMV-positive cases were co-infected with FeLV. Although no direct association between FeLV and FeMV infection has been established, FeLV is known affect renal function through systemic infection, often leading to immune-complex glomerulonephritis [32]. Histopathological analysis using PAS staining identified MPGN in two FeMV-positive cats co-infected with FeLV. However, no FeMV-specific immunostaining or ISH signals were observed in the glomeruli of any cases, suggesting no direct involvement of FeMV in MPGN development in this study. Viral RNA quantification via RT-dPCR showed a wide range of copy numbers among FeMV-positive kidneys. Although our study did not reveal a clear age-related pattern of FeMV-associated disease, these findings suggest that FeMV infection may not be age-dependent, and viral persistence can vary across individuals.

Among the 9 FeMV-positive cases, 2 cases did not exhibit immunostaining signals against the M protein. In contrast, the ISH assay targeting a partial genomic segment of the L gene of FeMV indicated that FeMV was localized in all 9 cases, consistent with the results of molecular FeMV detection. This discrepancy suggests that ISH may be more sensitive than IHC for FeMV detection, potentially due to differences in antigen expression levels or preservation. Immunostaining and ISH signals of FeMV antigens were observed in both the cytoplasm and, occasionally, the nucleus of renal tubular epithelial cells. While previous studies have reported FeMV localization primarily in the cytoplasm [15, 33], our study detected additional nuclear signals in some cases. While morbilliviruses typically replicate in the cytoplasm, intranuclear inclusion bodies have been reported [34], and viral proteins such as the large polymerase (L) may localize to the nucleus [35]. The ISH probe in this study targeted the L gene, which could potentially explain nuclear signal detection. The L protein is involved in RNA synthesis and may transiently interact with host nuclear components to modulate transcription or evade immune surveillance. However, this nuclear signal may also represent non-specific hybridization, and caution is warranted in interpreting it as true viral localization. Further investigation is needed to clarify whether nuclear localization reflects a biological process or an artifact. The presence of ICIBs confirmed by positive immunostaining or ISH in this study supports previous findings that FeMV-1 exhibits renal epitheliotropism [19]. Additional histopathological changes observed in FeMV-infected kidneys—including TIN, tubular degeneration, and epithelial vacuolation—have also been described in earlier reports [1]. Previous studies have suggested that FeMV may trigger an immune-mediated response in renal tissue, potentially involving recruitment of inflammatory cells and resulting in the development of TIN [36–38]. In our study, all FeMV-positive cases exhibited varying degrees of lymphoplasmacytic TIN. However, it is important to note that TIN is a non-specific lesion and can arise from diverse etiologies, including other infectious, immune-mediated processes, and idiopathic conditions. Moreover, our analysis did not demonstrate a statistically significant association between FeMV viral load and TIN severity. Interestingly, in three cases where ICIBs were most prominent, the degree of inflammatory cell infiltration was lower than in cases with only mild to moderate ICIB presence. This finding may suggest a complex or potentially inverse relationship between viral antigen accumulation and immune cell infiltration. Such variability could reflect differences in host immune response, infection stage, viral replication dynamics, or other unidentified factors. Although our findings are consistent with previous reports of TIN in FeMV-positive kidneys, the current evidence remains insufficient to establish FeMV as a definitive causative agent of interstitial nephritis. Further longitudinal and mechanistic studies are required to clarify whether FeMV plays a direct pathogenic role or functions as a co-factor in the development of multifactorial renal disease.

While the significant correlation of renal interstitial fibrosis between FeMV infection and non-infection was found, the observed association could be influenced by potential sampling bias—such as age distribution skewed toward older cats—as well as other confounding factors unrelated to viral infection. Persistent FeMV infection could contribute to chronic kidney damage, as renal injuries may lead to fibrosis even after viral clearance [39, 40], ultimately impairing tissue repair processes [41]. Nevertheless, further experimental studies are needed to confirm whether FeMV plays a direct causative role in renal fibrosis.

A key finding of this study is the significantly higher expression of cCasp3 in FeMV-positive cases compared to FeMV-negative controls, indicating increased caspase-dependent apoptotic activity in infected kidneys. Additionally, both the Kruskal–Wallis and Spearman’s rank correlation tests revealed a significant association between FeMV viral load and cCasp3 expression, supporting the hypothesis that viral burden may drive caspase-mediated apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells. These findings are consistent with previous reports of enhanced apoptotic activity in FeMV-infected renal tissue [29]. The co-localization of FeMV-1 antigens with activated caspase-3 further suggests that FeMV-1 may directly contribute to caspase-dependent apoptotic processes. Together, these results reinforce a link between FeMV infection and caspase-3–mediated apoptosis, aligning with mechanisms reported in other morbillivirus infections [42, 43].

IHC also showed cytoplasmic expression of BAX and BCL-2 in renal tubular epithelial cells, and BAX co-localized with FeMV antigens. However, neither BAX nor BCL-2 expression differed significantly between FeMV-positive and FeMV-negative groups, nor were they significantly correlated with viral load. This suggests that FeMV infection alone may not be sufficient to alter the expression of these upstream apoptotic regulators. While BAX and BCL-2 are known to modulate intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathways, their involvement in FeMV-associated renal injury remains uncertain. It is possible that their expression reflects basal cellular stress responses rather than virus-specific apoptotic signaling. In contrast, the significant increase in cCasp3 expression in infected kidneys—particularly in association with viral load—supports a more direct role for FeMV in triggering caspase-dependent apoptosis. These findings highlight the complexity of virus–host interactions in the kidney and suggest that FeMV may contribute to renal damage primarily through activation of downstream apoptotic effectors. Other paramyxoviruses such as measles virus and Newcastle disease virus, have been shown to trigger both extrinsic (caspase-8-mediated) and intrinsic (BAX/Bak-mediated) apoptotic pathways. Whether FeMV preferentially triggers extrinsic apoptosis remains to be elucidated.

Although a significant association was found between FeMV viral load and cCasp3 expression, no such association was observed with other histopathological parameters, including TIN, fibrosis, or the expression of BAX and BCL-2. These findings suggest that FeMV may contribute specifically to caspase-dependent apoptotic processes, while fibrosis and inflammation could result from multifactorial or secondary mechanisms not directly linked to viral burden. Several points must be considered, as apoptosis is a common response that occurs in the kidney even during sterile insults such as toxins, ischemia, or physical trauma [37, 44, 45]. The prolonged apoptotic activity on renal tissue could cause renal interstitial fibrosis [46]. The pathway which FeMV induces apoptosis remains unknown. Thus, further investigation regarding these findings needs to be conducted. This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. The sample size was small, and four of the FeMV-positive cases were co-infected with FeLV, which could potentially confound the histological interpretation. The viral load variation among samples may also influence observed pathology. Importantly, the small sample size and the presence of FeLV co-infection in several cases may confound the interpretation of FeMV-specific pathology. While comorbidities were noted in some cases, no cases were excluded on this basis to preserve a representative sample of naturally infected cats. This may introduce variability in histopathological findings and should be considered when evaluating the generalizability of these findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, FeMV may be associated with pathological alterations in renal tissue, particularly through the enhancement of caspase-dependent apoptotic activity, although the precise mechanism remains to be elucidated. Although our findings are associative, they raise the possibility that FeMV infection may play a contributory role in the early stages of kidney injury; however, further studies are needed to determine causality. Further investigations are necessary to clarify the mechanisms by which FeMV regulates apoptotic activity and to better understand its role in renal pathology.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and ethics

A total of 150 deceased cats with a history of azotemia, CKD, or gross morphological features suggestive of CKD—based on established diagnostic guidelines [47]—were sampled during necropsy at the Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University, between 2019 and 2022. Comprehensive clinical information, including age, sex, blood profile, the medical records (at least one month before death), and macroscopic and microscopic kidney lesions, was systematically documented for subsequent analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The age of the cats was recorded according to Feline Life Stage Guidelines [48].

Both right and left kidneys, from the same individual cats, were dissected along the mid-sagittal line, encompassing cortical, medullar, and pelvis regions, and were collected for two sample sets. The first sample set involved fresh tissues stored at -80 °C for molecular investigation, while the second sample set comprised preserved tissues fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathological study, special staining assessment, caspase-dependent apoptotic activity, and assay related to viral localization and distribution. Informed consent was obtained from all pet owners prior to the collection of samples. Additionally, nine kidney samples that previously tested negative for FeMV by cRT-PCR [11] and were confirmed free of common viral infections through an in-house diagnostic PCR screening pipeline [49] were included as a control group for comparison. This study was received approval from the Chulalongkorn University Animal Care and Use Committee (No. 2231023), and all procedures complied with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Molecular assays for FeMV screening and viral quantification

Fresh kidney tissue from each sample was used to prepare a 10% tissue homogenate by mixing approximately 5 g of tissue in 1 mL of 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using a Tissue Ruptor (Qiagen, Germany). Genomic materials were extracted followed the manufacturer’s protocol of the QIAamp® cador® Pathogen Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The synthetic RNA (QuantiNova Internal Control RNA and Assay, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was added during extraction to determine the effectiveness of extraction and reverse transcription process. The purity and concentration of the obtained nucleic acid were measured using spectrophotometer analysis (NanoDrop, Thermo Scientific™, USA).

To re-confirm and differentiate of FeMV in these cases, the molecular screening for the presence of FeMV-1 and FeMV-2 involved the utilization of previously described protocols [50]. Briefly, a total of 50 µl of a mixture of commercial one step reverse-transcription (RT) PCR kit (Qiagen OneStep RT-PCR kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 10 pmol of each forward and reverse primers, and 5 µl of RNA template, was employed. The thermocycler conditions consisted of RT step at 50 °C for 30 min, followed by activation of PCR step at 94 °C, 15 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s, annealing at 55 °C, 30 s, extension at 72 °C, 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min, employing a Labcycler thermocycler (SensoQuest, Germany). An amplicon size of approximately 500 bp was considered positive detection. Sequence-known FeMV-1/Thailand strain (GenBank accession numbers MN295672) [15] and FeMV-2/Germany Gordon strain (GenBank accession numbers MK182089) were used as positive controls. A non-template control (NTC) served as a negative control by replacing the template with RNase free water.

PCR products were analyzed using QIAxcel Advance DNA-screening (Qiagen, Germany). Samples showing bands according to the reference size was further processed for gel electrophoresis and purification using Macherey-Nagel™ NucleoSpin™ Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) before being sent for bidirectional Sanger sequencing (Macrogen, Korea). The sequencing results were used to confirm the presence of FeMV by blasting to the previously described FeMV genomes using the Nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn) from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database.

FeMV-positive cases were further examined for selective viral screening of viruses likely to be associated with kidney disease [51]. Conventional reverse-transcription PCR (cRT-PCR) or cPCR, using either pan-primer or specific primer sets, were performed to detect evidence of infection with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) [52], feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) [53], feline coronavirus (FCoV) [54], feline calicivirus (FCV) [55], and feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV) [56] (Supplementary Table S3). The viral load of all FeMV-positive cases was subsequently quantified.

The extracted RNA samples from both FeMV-positive and FeMV-negative cases (control group) were subjected further for viral load quantification of FeMV RNA through RT-digital PCR (RT-dPCR) using the QIAcuity Digital PCR System (QIAGEN, Germany). In this assay, we utilized primer set LPW12490-12491 from previous study, with amplicon size around 155 bp, targeting the partial L-gene [1]. Each sample was run in duplicates using QIAcuity OneStep Advanced Probe Kit on a 24-well 26K-partition nanoplate (QIAGEN, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The 40-µl reaction mixture included 10 µl of 4x OneStep Advanced Probe Master Mix, 0.4 µl of 100x OneStep Advanced RT Mix, 1.6 µl of each forward and reverse primer (400 nM), 0.8 µl probe (200 nM), 5 µl of RNA template and 20.6 µl RNase-free water. The fluorescent-labelled oligonucleotide probe was designed based on the conserved L-gene region of FeMV, amplified with the primer set 5’-FAM6- CCT GGG TTT TTT CAG TGG CTT CAC AAA ATT-BHQ1-3’ (BIONICS, Korea) [1]. Cycling conditions included 50 ºC for 40 min for the RT step, followed by 95 ºC for 2 min for RT enzyme inactivation, 50 cycles of 95 ºC for 5 s for denaturation, 55 ºC for 30 s for annealing, and 72 ºC for 30 s for extension. Finally, the nanoplate was imaged, the emitted fluorescent signal was measured, and the absolute FeMV copy number of each replicate was automatically reported as copies/µl created by the QIAcuity Software Suite 2.1.7.182 (QIAGEN, Germany). The calculation involved the ratio of the positive partition to the valid partition and was supported by a Poisson statistic distribution with a 95% confidence interval [57]. The reported FeMV copy number of each case was averaged from duplicates. Sequencing-confirmed FeMV-positive control and NTC were also included to ensure the assay’s reliability.

Pathological investigation of feline kidneys

As described above, the second sample set included renal tissues fixed in formalin for 48 h and subsequently processed for routine histology. The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues were scroll cut at a thickness of 4 μm and placed on positively charged slides for further routine histology staining with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E), special staining Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and Masson trichrome (MT), viral localization using ISH and IHC, and apoptotic activity investigation. FeMV-PCR-positive cases were then examined under a microscope for the presence of eosinophilic ICIBs in the renal epithelial cells [19]. The degree of ICIBs presence in renal tubules was qualitatively evaluated and categorized as mild (ICIBs observed in 1/3 of renal tissue), moderate (ICIBs observed in 2/3 of renal tissue), and severe (ICIBs observed throughout the renal tissue). Special stains, including MT and PAS, were also applied to evaluate the presence of fibrosis in the interstitial area of renal tissue and the integrity of the renal basement membrane, respectively. In addition, the interstitial inflammation, marked by lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration was accounted for evaluation. The sections were then evaluated and semi-quantitatively scored as previously described [1, 22, 58].

FeMV localization and distribution in kidneys

To determine the localization of FeMV in renal tissue, IHC against the M protein [15, 19] and ISH targeting conserved L gene of FeMV, were conducted simultaneously on the FFPE samples. The IHC protocol was performed by following previous studies [15, 19] applying a rabbit polyclonal anti-FeMV M protein at a dilution of 1:250 (v/v) on renal FFPE sections, incubating at 37 ºC for 1 h. Isotype control antibodies were used in place of the primary antibody (Enzo®, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) labelled EnVision polymer conjugated to goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (EnVision, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was used as a secondary antibody. The positive immunosignal was observed by the brown color of 3, 3 -diaminobenzidine (DAB) under a microscope. A kidney section previously confirmed to be positive of FeMV [19], through IHC assay, was used as positive control.

For the ISH assay, a digoxigenin-deoxyuridine triphosphate (DIG-dUTP) labelled-probe was constructed from purified PCR product of FeMV-L gene, following the manufacturer’s protocol of PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche, USA). Hybridization was carried out in a peroxidase system. After the pretreatment in citrate buffer pH 6.0 (0.01 M) at 121 ºC for 5 min, the section was washed in 1x Tris-NaCl-EDTA (TNE) (v/v) buffer for 5 min. Subsequently, endogenous peroxidase blocking was performed in 3% (v/v) H2O2 for 15 min, and nonspecific blocking was done in 0.5% (w/v) BSA at 37 ºC for 1 h. The section was then soaked with hybridization buffer containing the synthesized probe and incubated in a humidified, light protected chamber at 37 ºC overnight. Afterward, the section was washed in a series of diluted Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer (v/v) 2x SSC, 1x SSC, and 0.5x SSC. Anti-DIG polymerized horseradish peroxidase (POD) antibody (Roche, USA), at a dilution of 1:200 (v/v) was applied to the section and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The ISH signal was visualized using ImmPACT®VIP Peroxidase Substrate according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Vector Laboratories, USA). Methyl green was utilized for counterstaining. The positive hybridization signal was considered when the purple color precipitation was found within cells. The hybridization buffer containing the unrelated probe (feline bocavirus-3 probe) [59] was used to replace the FeMV probe, utilizing the negative control slide. The ISH signal was monitored under a microscope.

Caspase-dependent apoptotic activity assay

The intrinsic, or mitochondrial, pathway of apoptosis was evaluated using immunohistochemistry. This involved assessing the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein BCL-2–associated X protein (BAX) and apoptotic marker cCasp3, achieved using the SignalStain® Proliferation/Apoptosis IHC Sampler Kit (Cell Signaling TECHNOLOGY, USA), following previously described protocols [49]. To complement this analysis, the expression of BCL-2—an anti-apoptotic protein—was also evaluated, based on methods reported in earlier studies [60]. The FeMV-negative kidney samples were included as the control group for immunohistochemical comparison.

Briefly, the section underwent antigen retrieval in boiled citrate buffer (95 ºC) pH 6.0 (0.01 M) for 10 min (for BAX) and 20 min (for cCasp3) and 121 °C (for BCL-2). Endogenous peroxidase was deactivated using 3% (v/v) hydrogen peroxidase (H2O2) at room temperature (RT) for 15 min (for BAX), 30 min (for cCasp3) and 10 min (for BCL-2). Non-specific blocking was performed using 5% (w/v) skim milk for 60 min at 37 °C (for BAX), 2.5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) (EMD Millipore, USA) for 90 min at RT (for cCasp3) and 1% (w/v) BSA for 30 min at 37 °C (for BCL-2). The primary antibody for BAX (monoclonal mouse anti-BAX Clone1F5-1B7, dilution 1:100 (v/v), Sigma Aldrich, Germany), cCasp3 (monoclonal antibody against cCasp3 (Asp175), dilution 1:400 (v/v), Cell Signaling TECHNOLOGY, USA), and for BCL-2 (monoclonal mouse anti-human Bcl-2 oncoprotein (NCL-bcl-2-486), dilution 1:100 (v/v), Leica, United Kingdom) were applied to the sections and incubated overnight at 4ºC. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with anti-rabbit/mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (EnVision, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 37 °C for 45 min (for BAX) and 60 min (for cCasp3) and at RT for 45 min (for BCL-2). 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used as the substrate for the peroxidase reaction, and the sections were then counterstained with haematoxylin. A universal negative control of Immunoglobulins (IgGs) (Enzo®, USA) was used to replace the primary antibody in the negative control slide, with the positive immunosignal appearing in brown color. Tissue sections from mammary gland adenocarcinoma biopsies, previously confirmed to express BCL-2, BAX and cCasp3, were used to validate the assay. The sections were then evaluated using semi-quantitative scoring system according to a previous study with some modifications [58] (Supplementary Table S4). To confirm the potential of FeMV in inducing caspase-dependent apoptotic activity, a co-localization assay was performed to observe the simultaneous presence of FeMV and BAX or cCasp3 expressed in renal tubular epithelial cells through double IHC (brown color for FeMV and purple color for apoptotic activity) as protocols mentioned above.

Data analyses

Histological analyses, including H&E staining, special staining, and immunohistochemical assessment of apoptotic activity, were conducted in a blinded manner by three independent pathologists. All slides were randomized and labeled with coded identifiers to ensure that evaluators were unaware of case information during scoring. Descriptive evaluation of histopathological changes was performed for each assay. Semi-quantitative scoring was applied to parameters related to FeMV infection, including interstitial inflammation, fibrosis, and pro- and anti-apoptotic marker expression [22, 29]. Interstitial inflammation, along with BCL-2 and BAX expression, was assessed at low-power magnification (4×) across five randomly selected fields. Interstitial fibrosis was evaluated at 10× magnification, while cCasp3 expression was assessed at high-power magnification (40×). Mean scores from the three observers were used for statistical analysis. Both FeMV-positive and FeMV-negative (control) groups were evaluated using the same methodology.

To assess the relationship between FeMV infection and histopathological/apoptotic parameters, nine FeMV-negative CKD kidney samples were included as controls. Semi-quantitative scores from the FeMV-positive and control groups (Supplementary Table S5) were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Additionally, within the FeMV-positive group, viral load was compared to mean scores for each histopathological and apoptotic parameter. Non-parametric tests were used due to the ordinal nature of the scoring and the sample size. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to detect differences in marker expression across levels of viral load. Spearman’s rank correlation was then applied to evaluate monotonic relationships between FeMV viral load (as a continuous variable) and marker expression. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, USA), with significance set at P < 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Table 1: Comprehensive clinical information, including age, sex, blood profile, the latest medical records (at least one month before death), and macroscopic and microscopic kidney lesions of FeMV-infected cats

Supplementary Table 2: Additional data corresponding to necropsied FeMV-positive cats and FeMV-negative cats (control group)

Supplementary Table 3: Primer sets for selective viral screening by cRT-PCR/cPCR

Supplementary Table 4: Semi-quantitative scoring system for histopathological alteration

Supplementary Table 5: Summary of semiquantitative scoring of FeMV-positive and FeMV-negative (control group)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof.Dr.Anudep Rungsipipat and Assist. Prof. Dr. Kasem Rattanapinyopituk (Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University) who kindly provided the antibody for BCL-2 and BAX, respectively.

Abbreviations

- BAX

BCL-2 associated X protein

- BCL-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- cCasp3

Cleaved caspase-3

- cRT-PCR

Conventional reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- DIG

Digoxigenin

- FeMV

Feline morbillivirus

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- ICIBs

Intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- ISH

In situ hybridization

- MPGN

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- MT

Masson Trichrome

- NTC

Non-template control

- PAS

Periodic Acid Schiff

- POD

Polymerized horseradish peroxidase

- RT

Reverse transcription

- RT-dPCR

Reverse transcription-digital polymerase chain reaction

- SLAM

Signalling lymphocytic activation molecule

- TIN

Tubulointerstitial nephritis

Author contributions

ANZ, PP, CP, and ST designed and performed the experiments; MS and TV provided the positive control utilized in this study; ANZ, CP, and ST performed the histologic evaluations, semiquantitative scoring and statistical analysis; ANZ and PP performed the viral quantification assay; the manuscript was written by ANZ, CP, and ST with the contribution of all authors.

Funding

This research project is supported by Graduate Scholarship Program for ASEAN or Non-ASEAN Countries of Chulalongkorn University (to ANZ), National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT): (Grant No. NRCT5-RGJ63001-013) and Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University (to CP and PP), and the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund) (to ANZ).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was received approval from the Chulalongkorn University Animal Care and Use Committee (No. 2231023). Informed consent was obtained from all pet owners prior to inclusion of the animals in the study. All kidney samples used in this study were obtained post mortem from cats that had died due to natural causes or unrelated medical conditions and were submitted for routine necropsy. No animals were euthanized or sedated for the purpose of this research, and no anesthesia or drug administration was performed by the investigators. All methods performed in this study comply with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Woo PC, Lau SK, Wong BH, Fan RY, Wong AY, Zhang AJ, Wu Y, Choi GK, Li KS, Hui J, et al. Feline morbillivirus, a previously undescribed paramyxovirus associated with tubulointerstitial nephritis in domestic cats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(14):5435–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sieg M, Heenemann K, Ruckner A, Burgener I, Oechtering G, Vahlenkamp TW. Discovery of new feline paramyxoviruses in domestic cats with chronic kidney disease. Virus Genes. 2015;51(2):294–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharp CR, Nambulli S, Acciardo AS, Rennick LJ, Drexler JF, Rima BK, Williams T, Duprex WP. Chronic infection of domestic cats with feline morbillivirus, united States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(4):760–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohd Isa NH, Selvarajah GT, Khor KH, Tan SW, Manoraj H, Omar NH, Omar AR, Mustaffa-Kamal F. Molecular detection and characterisation of feline morbillivirus in domestic cats in Malaysia. Vet Microbiol. 2019;236:108382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Luca E, Crisi PE, Marcacci M, Malatesta D, Di Sabatino D, Cito F, D’Alterio N, Puglia I, Berjaoui S, Colaianni ML, et al. Epidemiology, pathological aspects and genome heterogeneity of feline morbillivirus in Italy. Vet Microbiol. 2020;240:108484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sieg M, Busch J, Eschke M, Bottcher D, Heenemann K, Vahlenkamp A, Reinert A, Seeger J, Heilmann R, Scheffler K et al. A new genotype of feline morbillivirus infects primary cells of the lung, kidney, brain and peripheral blood. Viruses 2019, 11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Furuya T, Sassa Y, Omatsu T, Nagai M, Fukushima R, Shibutani M, Yamaguchi T, Uematsu Y, Shirota K, Mizutani T. Existence of feline morbillivirus infection in Japanese Cat populations. Arch Virol. 2014;159(2):371–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz H, Tekelioglu BK, Gurel A, Bamac OE, Ozturk GY, Cizmecigil UY, Altan E, Aydin O, Yilmaz A, Berriatua E, et al. Frequency, clinicopathological features and phylogenetic analysis of feline morbillivirus in cats in istanbul, Turkey. J Feline Med Surg. 2017;19(12):1206–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCallum KE, Stubbs S, Hope N, Mickleburgh I, Dight D, Tiley L, Williams TL. Detection and Seroprevalence of morbillivirus and other paramyxoviruses in geriatric cats with and without evidence of azotemic chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(3):1100–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donato G, De Luca E, Crisi PE, Pizzurro F, Masucci M, Marcacci M, Cito F, Di Sabatino D, Boari A, D’Alterio N, et al. Isolation and genome sequences of two feline morbillivirus genotype 1 strains from Italy. Vet Ital. 2019;55(2):179–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaiyasak S, Piewbang C, Rungsipipat A, Techangamsuwan S. Molecular epidemiology and genome analysis of feline morbillivirus in household and shelter cats in Thailand. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16(1):240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou J, Ye S, Xu H, Zhao J, Ren Z, Lu G, Li S. First report of feline morbillivirus in Mainland China. Arch Virol. 2020;165(8):1837–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busch J, Heilmann RM, Vahlenkamp TW, Sieg M. Seroprevalence of infection with feline morbilliviruses is associated with FLUTD and increased blood creatinine concentrations in domestic cats. Viruses. 2021;13(4):578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busch J, Sacristan I, Cevidanes A, Millan J, Vahlenkamp TW, Napolitano C, Sieg M. High Seroprevalence of feline morbilliviruses in free-roaming domestic cats in Chile. Arch Virol. 2021;166(1):281–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piewbang C, Chaiyasak S, Kongmakee P, Sanannu S, Khotapat P, Ratthanophart J, Banlunara W, Techangamsuwan S. Feline morbillivirus infection associated with tubulointerstitial nephritis in black leopards (Panthera pardus). Vet Pathol. 2020;57(6):871–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sieg M, Sacristán I, Busch J, Terio KA, Cabello J, Hidalgo-Hermoso E, Millán J, Böttcher D, Heenemann K, Vahlenkamp TW et al. Identification of novel feline paramyxoviruses in Guignas (Leopardus guigna) from Chile. Viruses 2020, 12(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Piewbang C, Wardhani SW, Dankaona W, Yostawonkul J, Boonrungsiman S, Surachetpong W, Kasantikul T, Techangamsuwan S. Feline morbillivirus-1 in dogs with respiratory diseases. Transbound Emerg Dis 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lavorente FLP, de Matos A, Lorenzetti E, Oliveira MV, Pinto-Ferreira F, Michelazzo MMZ, Viana NE, Lunardi M, Headley SA, Alfieri AA et al. First detection of feline morbillivirus infection in white-eared opossums (Didelphis albiventris, lund, 1840), a non-feline host. Transbound Emerg Dis 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Chaiyasak S, Piewbang C, Yostawonkul J, Boonrungsiman S, Kasantikul T, Rungsipipat A, Techangamsuwan S. Renal epitheliotropism of feline morbillivirus in two cats. Vet Pathol. 2022;59(1):127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crisi PE, Dondi F, De Luca E, Di Tommaso M, Vasylyeva K, Ferlizza E, Savini G, Luciani A, Malatesta D, Lorusso A et al. Early renal involvement in cats with natural feline morbillivirus infection. Anim (Basel) 2020, 10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Darold GM, Alfieri AA, Muraro LS, Amude AM, Zanatta R, Yamauchi KC, Alfieri AF, Lunardi M. First report of feline morbillivirus in South America. Arch Virol. 2017;162(2):469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutummaporn K, Suzuki K, Machida N, Mizutani T, Park ES, Morikawa S, Furuya T. Association of feline morbillivirus infection with defined pathological changes in Cat kidney tissues. Vet Microbiol. 2019;228:12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stranieri A, Lauzi S, Dallari A, Gelain ME, Bonsembiante F, Ferro S, Paltrinieri S. Feline morbillivirus in Northern italy: prevalence in urine and kidneys with and without renal disease. Vet Microbiol. 2019;233:133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park ES, Suzuki M, Kimura M, Mizutani H, Saito R, Kubota N, Hasuike Y, Okajima J, Kasai H, Sato Y, et al. Epidemiological and pathological study of feline morbillivirus infection in domestic cats in Japan. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12(1):228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers R, Takimoto T. Antagonism of innate immunity by paramyxovirus accessory proteins. Viruses. 2009;1(3):574–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esolen LM, Park SW, Hardwick JM, Griffin DE. Apoptosis as a cause of death in measles virus-infected cells. J Virol. 1995;69(6):3955–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bitzer M, Prinz F, Bauer M, Spiegel M, Neubert WJ, Gregor M, Schulze-Osthoff K, Lauer U. Sendai virus infection induces apoptosis through activation of Caspase-8 (FLICE) and Caspase-3 (CPP32). J Virol. 1999;73(1):702–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hariya Y, Yokosawa N, Yonekura N, Kohama G, Fuji N. Mumps virus can suppress the effective augmentation of HPC-induced apoptosis by IFN-gamma through disruption of IFN signaling in U937 cells. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44(6):537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutummaporn K, Suzuki K, Machida N, Mizutani T, Park ES, Morikawa S, Furuya T. Increased proportion of apoptotic cells in Cat kidney tissues infected with feline morbillivirus. Arch Virol. 2020;165(11):2647–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Havasi A, Borkan SC. Apoptosis and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2011;80(1):29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donato G, Masucci M, De Luca E, Alibrandi A, De Majo M, Berjaoui S, Martino C, Mangano C, Lorusso A, Pennisi MG. Feline Morbillivirus in Southern Italy: Epidemiology, Clinico-Pathological Features and Phylogenetic Analysis in Cats. Viruses. 2021;13(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Rossi F, Aresu L, Martini V, Trez D, Zanetti R, Coppola LM, Ferri F, Zini E. Immune-complex glomerulonephritis in cats: a retrospective study based on clinico-pathological data, histopathology and ultrastructural features. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15(1):303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaiyasak S, Piewbang C, Yostawonkul J, Boonrungsiman S, Kasantikul T, Rungsipipat A, Techangamsuwan S. Renal epitheliotropism of feline morbillivirus in two cats. Vet Pathol 2021:3009858211045441. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Piewbang C, Chansaenroj J, Kongmakee P, Banlunara W, Poovorawan Y, Techangamsuwan S. Genetic adaptations, biases, and evolutionary analysis of canine distemper virus Asia-4 lineage in a fatal outbreak of Wild-Caught civets in Thailand. Viruses 2020, 12(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Sato H, Masuda M, Miura R, Yoneda M, Kai C. Morbillivirus nucleoprotein possesses a novel nuclear localization signal and a CRM1-independent nuclear export signal. Virology. 2006;352(1):121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soos TJ, Sims TN, Barisoni L, Lin K, Littman DR, Dustin ML, Nelson PJ. CX3CR1 + interstitial dendritic cells form a contiguous network throughout the entire kidney. Kidney Int. 2006;70(3):591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurts C, Panzer U, Anders HJ, Rees AJ. The immune system and kidney disease: basic concepts and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(10):738–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abraham SN, Miao Y. The nature of immune responses to urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(10):655–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monaghan K, Nolan B, Labato M. Feline acute kidney injury: 1. Pathophysiology, etiology and etiology-specific management considerations. J Feline Med Surg. 2012;14(11):775–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown CA, Elliott J, Schmiedt CW, Brown SA. Chronic kidney disease in aged cats: clinical features, morphology, and proposed pathogeneses. Vet Pathol. 2016;53(2):309–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruggeman LA. Common mechanisms of viral injury to the kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26(3):164–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molouki A, Yusoff K. NDV-induced apoptosis in absence of bax; evidence of involvement of apoptotic proteins upstream of mitochondria. Virol J. 2012;9:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sahoo M, Thakor MD, Baloni JC, Saxena S, Shrivastava S, Dhama S, Singh K, Singh K. Neuropathology mediated through caspase dependent extrinsic pathway in goat kids naturally infected with PPRV. Microb Pathog. 2020;140:103949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cowgill LD, Polzin DJ, Elliott J, Nabity MB, Segev G, Grauer GF, Brown S, Langston C, van Dongen AM. Is progressive chronic kidney disease a slow acute kidney injury?? Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2016;46(6):995–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Dunaevich A, Apfelbaum N, Kuzi S, Mazaki-Tovi M, Aroch I, Segev G. Acute on chronic kidney disease in cats: etiology, clinical and clinicopathologic findings, prognostic markers, and outcome. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34(4):1496–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jang HS, Padanilam BJ. Simultaneous deletion of Bax and bak is required to prevent apoptosis and interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2015;309(6):F540–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sparkes AH, Caney S, Chalhoub S, Elliott J, Finch N, Gajanayake I, Langston C, Lefebvre HP, White J, Quimby J. ISFM consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of feline chronic kidney disease. J Feline Med Surg. 2016;18(3):219–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quimby J, Gowland S, Carney HC, DePorter T, Plummer P, Westropp J. 2021 AAHA/AAFP feline life stage guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2021;23(3):211–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piewbang C, Dankaona W, Poonsin P, Yostawonkul J, Lacharoje S, Sirivisoot S, Kasantikul T, Tummaruk P, Techangamsuwan S. Domestic Cat hepadnavirus associated with hepatopathy in Cats: A retrospective study. J Vet Intern Med. 2022;36(5):1648–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tong S, Chern SW, Li Y, Pallansch MA, Anderson LJ. Sensitive and broadly reactive reverse transcription-PCR assays to detect novel paramyxoviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(8):2652–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartmann K, Pennisi MG, Dorsch R. Infectious agents in feline chronic kidney disease: what is the evidence?? Adv Small Anim Care. 2020;1:189–206. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lacharoje S, Techangamsuwan S, Chaichanawongsaroj N. Rapid characterization of feline leukemia virus infective stages by a novel nested recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) and reverse transcriptase-RPA. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):22023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Techakriengkrai N, Suksamai P, Wachiratada N. Confirmation of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) Infection by Provirus PCR. In: the 17th Chulalongkorn University Veterinary Conference 2018: 25–27 April 2018; Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University; 2018:25–26.

- 54.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, Tong S, Urbani C, Comer JA, Lim W, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1953–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piewbang C, Kasantikul T, Pringproa K, Techangamsuwan S. Feline bocavirus-1 associated with outbreaks of hemorrhagic enteritis in household cats: potential first evidence of a pathological role, viral tropism and natural genetic recombination. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mochizuki M, Horiuchi M, Hiragi H, San Gabriel MC, Yasuda N, Uno T. Isolation of canine parvovirus from a Cat manifesting clinical signs of feline panleukopenia. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(9):2101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Group Td, Huggett JF. The digital MIQE guidelines update: minimum information for publication of quantitative digital PCR experiments for 2020. Clin Chem. 2020;66(8):1012–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McLeland SM, Cianciolo RE, Duncan CG, Quimby JM. A comparison of biochemical and histopathologic staging in cats with chronic kidney disease. Vet Pathol. 2015;52(3):524–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piewbang C, Wardhani SW, Phongroop K, Lohavicharn P, Sirivisoot S, Kasantikul T, Techangamsuwan S. Naturally acquired feline bocavirus type 1 and 3 infections in cats with neurologic deficits. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69(5):e3076–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sakarin S, Rungsipipat A, Surachetpong SD. Expression of apoptotic proteins in the pulmonary artery of dogs with pulmonary hypertension secondary to degenerative mitral valve disease. Res Vet Sci. 2022;145:238–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Comprehensive clinical information, including age, sex, blood profile, the latest medical records (at least one month before death), and macroscopic and microscopic kidney lesions of FeMV-infected cats

Supplementary Table 2: Additional data corresponding to necropsied FeMV-positive cats and FeMV-negative cats (control group)

Supplementary Table 3: Primer sets for selective viral screening by cRT-PCR/cPCR

Supplementary Table 4: Semi-quantitative scoring system for histopathological alteration

Supplementary Table 5: Summary of semiquantitative scoring of FeMV-positive and FeMV-negative (control group)

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.