Abstract

Background

Due to the lack of effective targeted therapies and the high likelihood of acquired resistance, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) remains one of the deadliest cancers affecting women globally. Investigating the mechanism underlying TNBC’s resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy and identifying new therapeutic targets are urgent priorities.

Methods

The expression level of GPX3, cisplatin sensitivity, and ROS production were compared across three TNBC cell lines to elucidate the relationship between GPX3 and platinum resistance. RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analyses of GPX3 knockdown cells revealed its regulation of stress-related signaling pathways and TGFB1. The regulation of TGFB1 by GPX3 was further investigated using Western blotting, RNA interference, confocal microscopy, and inhibitor treatments. The correlation between the expression level of GPX3, TGFB1, and ZEB2 was analyzed using breast cancer microarrays and the TCGA database. The effect of GPX3 on platinum sensitivity in TNBC was studied using a mouse xenograft model.

Results

GPX3 expression was upregulated in more invasive TNBC cells, promoting resistance to cisplatin-based chemotherapy. RNA sequencing revealed that the deletion of GPX3 resulted in a decrease in gene expression patterns associated with pro-tumor signaling pathways. Validation experiments confirmed that the upregulation of TGFB1 in acquired cisplatin resistance is highly dependent on GPX3. Further investigation revealed that the TGFB1-ZEB2 axis mediated platinum resistance and metastasis through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Additionally, platinum treatment increased GPX3 and TGFB1 expression and secretion, and their depletion enhanced platinum sensitivity in TNBC cells. We identified the GPX3-TGFB1-ZEB2 regulatory axis and found a positive correlation in the expression of all three in clinical samples. Our study also demonstrated that GPX3 knockdown inhibited TNBC tumor growth in platinum-treated mouse models.

Conclusions

This study reveals the signaling pathway mediated by GPX3-TGFB1-ZEB2 and its role in acquired platinum resistance and EMT in TNBC. Our findings suggest that GPX3 is a promising biomarker and potential therapeutic target for the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of high-risk TNBC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12964-025-02356-z.

Keywords: Triple-negative breast cancer, Cisplatin, Chemoresistance

Background

Breast cancer (BCa) is the most common malignancy in women worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. Among the molecular subtypes of BCa, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 overexpression or amplification [2, 3]. TNBC represents the most aggressive and lethal subtype, accounting for 15–20% of all BCa cases [4]. Cisplatin (CDDP) is a primary chemotherapeutic agent for TNBC patients, commonly used as monotherapy or combined with other drugs [5]. However, the emergence of resistance reduces the efficacy of CDDP, ultimately leading to therapeutic failure. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the mechanisms underlying TNBC resistance to CDDP-based chemotherapy and identify novel therapeutic targets.

CDDP primarily exerts its anticancer effects by binding to guanine and adenine residues, which leads to apoptosis or cell cycle arrest [6]. Additionally, the antitumor mechanism of CDDP involves the generation of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), which directly damage cellular DNA, lipids, and proteins [7]. Thus, resistance to CDDP may arise from alterations that mitigate or adapt to the molecular damage induced by CDDP in these cellular components. However, the current understanding of these alterations remains limited.

Under normal physiological conditions, cellular redox homeostasis ensures an appropriate response to endogenous and exogenous stimuli. Antioxidant enzymes and low-molecular-weight antioxidants are effective intrinsic defense mechanisms to maintain redox balance during oxidative stress [8, 9]. Glutathione peroxidase 3 (GPX3) is a secreted selenocysteine-containing protein that catalyzes the reduction of peroxides in the presence of glutathione (GSH) [10, 11]. Studies have reported decreased plasma GPX3 activity, associated with selenium deficiency, in many cancer patients, indicating a negative correlation between reduced plasma GPX3 levels and patient prognosis [12–14]. Recent evidence demonstrates that tumor-derived GPX3 is implicated in chemoresistance and tumor progression in several cancer types [10, 15, 16]. However, the potential molecular mechanisms of GPX3 in CDDP resistance in TNBC remain unclear.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is critical in promoting metastasis and drug resistance in various cancers, including TNBC [17, 18]. During EMT, cancer cells lose epithelial characteristics and acquire mesenchymal traits, along with a highly migratory and invasive phenotype [19]. EMT transcription factors (EMT-TFs), such as the SNAIL, TWIST, and ZEB protein families, mediated this transition [20, 21]. The expression of EMT-TFs in breast cancer cells not only induces EMT but also increases the population of stem-like cells, which exhibit self-renewal and anti-apoptotic properties [22, 23]. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), highly expressed in the tumor microenvironment (TME), plays a multifaceted role in tumor progression [24]. In the later stages of cancer development, TGF-β promotes tumor metastasis and therapy resistance by facilitating EMT and stem-like properties [25]. In the canonical TGF-β/SMAD pathway, TGF-β bound to its receptor and induced serine phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 (collectively called SMAD2/3) [26]. Phosphorylated SMAD2/3 form heterodimers with SMAD4, which translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene expression. TGFB1, the most common isoform of TGF-β, is elevated in the serum, tissues, and urine of cancer patients, with elevated levels correlating with tumor progression and reduced survival [27–29].

This study demonstrated that GPX3 enhanced TGFB1-SMAD2/3-ZEB2 signaling-mediated EMT in TNBC cells under CDDP treatment, thereby inducing cisplatin resistance. Depletion of GPX3 sensitized TNBC cells to CDDP and suppressed the EMT process. These findings suggested that the GPX3/TGFB1/ZEB2 axis is a promising therapeutic target for overcoming acquired cisplatin resistance and metastasis in TNBC.

Materials and methods

Drugs and reagents

Cisplatin (Cat. No. HY-17394), SB431542 (TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitors, TRKI, HY-10431), and recombinant human TGFβ1 protein from HEK293 (Cat. No. HY-P70543) were purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE). NAC (Cat. No. S0077) was purchased from Beyotime. ROS fluorescent probe (DCFH-DA) (Cat. No. G1706-100T) purchased from Servicebio. The antibodies used for Western blot, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and immunofluorescence (IF) staining were as following: GPX3 antibody (Cat. no.13947-1-AP), TGFB1 antibody (Cat. no. 81746-2-RR), ZEB2 antibody (Cat. no.14026-1-AP), E-cadherin antibody (Cat. no. 20874-1-AP), N-cadherin antibody (Cat. no.22018-1-AP), Vimentin antibody (Cat. no.60330-1-lg), MMP2 antibody (Cat. no.10373-2-AP), MMP9 antibody (Cat. no.10375-2-AP), c-Myc antibody (Cat. no.67447-1-Ig), and GAPDH antibody (Cat. no.60004-1-Ig) were purchased from proteintech. Smad2 antibody (Cat. no. A7699), Smad3 antibody (Cat. no. A16913), and phospho-Smad2-S465/S467 + Smad3-S423/S425 antibody (Cat. no. AP1343) were purchased from ABclonal. HRP Conjugated AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (Cat. No. BA1062), HRP Conjugated AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Cat. No. BA1061), DyLight 550 Conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (Cat. No. BA1135) and DyLight 488 Conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (Cat. No. BA1127) were purchased from Boster.

Cell culture

Human TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-231 (Cat. no. CL-0150), BT-549 (Cat. no. CL-0041), and SUM159PT (Cat. no. CL-0622) were purchased from the Pricella. TNBC cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), penicillin (100 U/ml; Invitrogen), and streptomycin (100 U/ml; Invitrogen). All cell lines were cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37℃ with CO2/air (5%/95%).

Gene silencing and over-expressing

1 × 10^5 cells were seeded in six-well plates. The following day, cells were transfected with lentiviruses or plasmids using Lipofectamine 8000 (Beyotime) or Neofect™ DNA transfection reagent (Neofect biotech), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR and WB verified the stable mRNA and protein expression levels. The over-expression lentiviruses LV-GPX3 (Cat. No. 77869-1) were purchased from Genechem. The over-expression plasmid TGFB1 (Cat. No. P46938) was purchased from Miaoling Biology. The specific shRNAs against GPX3, TGFB1, ZEB2, SMAD2, SMAD3, and corresponding scramble shRNA-NC were purchased from Sangon (Shanghai, China). Lentiviruses vector GV115 was used to package shRNAs. The sequences of shRNAs (5’-3’) are as follows, with target sequences in bold font:

GPX3 sh1: GTCCGACCAGGTGGAGGCTTTGTCCCTAATTTCCAGCTCTT.

GPX3 sh2: GACTGCCATGGTGGCATAAGTGGCACCATTTACGAGTACGG.

TGFB1 sh1: TGGAGAGAGGACTGCGGATCTCTGTGTCATTGGGCGCCTGC.

TGFB1 sh2: TGGTGGAAACCCACAACGAAATCTATGACAAGTTCAAGCAG.

ZEB2 sh1: GGCCAGAAGCCACGATCCAGACCGCAATTAACAATGGTACA.

ZEB2 sh2: ACTTGGGTTTCCCACCATGAATAGTAATTTAAGTGAGGTAC.

Samd2 sh1: CTTTCAACGGTATCAAGTGGTCCCACGAATACCAGGAGGCC.

Samd2 sh2: AGCTGCGGCAAGAACATTGTGCCCATCATTGATGGCTTCGA.

Samd3 sh1: ATGGAAACGAGCCCTCAAAGATCGCTTTAAATATGTTCGAA.

Samd3 sh2: TGGGCACCAGGCTGTTCTGATGGATTTAATTAAAAAATACA.

Drug sensitivity assay

5000 cells were seeded into 96-well plate, after adherence, cells were treated with DMSO as control and specific concentrations of drugs for 48 h. Cell viability was measured with CCK8 and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, VT). Drug sensitivity IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression (inhibitor vs. response (three parameters)) with Prism GraphPad software (version 10.2.3).

Quantity RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the RNA isolator Total RNA Extraction Reagent (R401-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR using SYBR Green PCR on Bio-Red real-time PCR system (Bio-Red, USA). The relative gene expression, for GAPDH as the housekeeping gene, was calculated following the 2−△△CT method. Primers purchased from Sangon (Shanghai, China). The primers (5’-3’) used in RT-qPCR were as follows:

GPX3-FP: AGAAGTCGAAGATGGACTGCC, GPX3-RP: GGGAAAGCCCAGAATGACCA;

TGFB1-FP: TACCTGAACCCGTGTTGCTC, TGFB1-RP: CGGTAGTGAACCCGTTGATGT;

ZEB2-FP: CAACCATGAGTCCTCCCCAC, ZEB2-RP: GTCTGGATCGTGGCTTCTGG.

Protein extraction and western blot

Cells with specific treatment were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with cold PBS, and lysed in Western and IP lysis buffer (Beyotime, P0013) for 30 min. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, P0011) and then suspended in 1× SDS loading buffer. For the western blot, 30 µg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5–12%) and transferred onto NC membranes. The membranes were probed with the corresponding primary antibodies and visualized using a super signal chemiluminescent substrate (Biosharp, BL520B). The intensity of protein bands was quantified using ImageJ software (version 2.1.0 / 1.53c).

Orthotopic nude mouse model

To determine the effect of GPX3 on TNBC cell response to CDDP in vivo and tumor growth, MDA-MB-231 cells with GPX3 knockdown or control cells (5 × 10⁶) were suspended in 50 µL PBS and injected into the mammary fat pad of female athymic nude mice. Five days post-injection, mice were randomly assigned to different groups. Drug treatment was initiated on day 7 post-implantation when most tumor size reached approximately 100 mm³ (3–6 mm, and > 70% of tumors exceeded 5 mm in diameter) [30, 31]. Mice with similar tumor burden were randomized into CDDP and saline groups. Mice received intraperitoneal injections of CDDP at 4 mg/kg every 5 days (q5d). This schedule continued for a total of 5 doses or until tumors reached the ethical endpoint (≥ 1500 mm³). The control group received PBS following the same schedule. Each group included 5 mice. Body weight and tumor volume were monitored every every other day; no animals exceeded the 15% weight loss threshold requiring intervention. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Tumor Volume = A×B2/ 2. A represents the longest tumor dimension and B is the perpendicular dimension to A. Mice were euthanized if their body weight decreased by more than 15% of pre-injection weight or if the maximum tumor volume reached 1500 mm³. During necropsy, tumor tissues were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for histological evaluation and tumor tissue identification.

Bulk RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from cell samples using TRIzol reagent. After quantification and purification, for total RNA, the Stranded mRNA Library Kit for Illumina® (Wuhan Seqhealth, China) was used to construct the library. Then, products of the library were investigated on DNBSEQ-T7 (MGI Tech. China). Based on the criterion (P value < 0.05 and fold change > 1.2), DEGs were evaluated using the edge R package. Afterwards, GO analysis, KEGG enrichment analysis, and GSEA were performed.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Supernatants from each group were collected and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min to remove debris. The clarified supernatants were stored at -80 °C before ELISA analysis. Total TGF-β1 concentration was measured using the Human TGF-β1 Platinum ELISA Kit (eBioscience), while the active form of TGF-β1 was quantified using the LEGEND MAX Free Active TGF-β1 ELISA Kit (BioLegend), following the manufacturer’s instructions. A standard curve was generated using serial dilutions of recombinant TGF-β1 provided by the manufacturer. Samples were loaded in duplicate onto a 96-well plate, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. TGF-β1 concentrations were determined by interpolating sample values onto the standard curve.

Measurement of GPX3 and TGFB1 secretion

TNBC cells were seeded in 10-cm culture dishes. Cells were grown to 80% confluence, switched to a serum-free medium and incubated for 48 h. Supernatants were collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter (Biosharp, BS-QT-013). The samples were concentrated using 10 kDa cutoff ultrafiltration centrifugal columns (Merk Millipore) to extract most secreted proteins. Proteins were suspended in 1 × SDS loading buffer, stored at -80 °C, or subjected to Western blot as described above. Ponceaux was used to standardize total secreted protein.

ChIP-qPCR

To identify the enrichment of SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 at the ZEB2 promoter region, existing ChIP-seq data were obtained from the UCSC website. Enrichment of SMAD3 binding fragments at the ZEB2 promoter region was identified, and primers were designed accordingly for ChIP-qPCR validation. Cells were seeded in 10-cm culture dishes, and when cell confluence reached 80%, they were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min. The fixation was quenched with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. Cells were collected and lysed to prepare chromatin according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibodies targeting smad3, and the enrichment at the ZEB2 promoter region was quantified by ChIP-qPCR.

The primers (5’-3’) used in ChIP-qPCR were as follows, and more details were presented in Table S1.

Primer1-FP: CCTACCTGCGAAGTCTTGTT, Primer1-RP: CTTCGCGGCTTCTTCATGC;

Primer2-FP: GGTGGAAGCGAAGAAACAGC, Primer2-RP: GTAACACGTCAGTCCGTCCC;

Primer3-FP: GACTGACGTGTTACGCCTCT, Primer3-RP: TCACATGATGCTCACGCTCA.

Luciferase reporter assay

1 × 10^5 cells were transiently co-transfected with pGL3 reporter plasmids containing the ZEB2 promoter and pRL-CMV using the Lipo8000 transfection reagent. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System.

Tissue microarray immunofluorescence

A breast cancer tissue microarray containing 75 tumor sites was used for 4-color immunofluorescence staining to examine the differences in protein expression levels of TGFB1 (sp-orange), GPX3 (sp-green), and ZEB2 (CY5) within breast cancer tissues. Nuclear staining was performed with DAPI.

Data collection and analysis

The data were collected from GEPIA (Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) and UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/ index.html), TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) online analysis tool. The expression level of GPX3, TGFB1, ZEB2, mesenchymal signature (CDH2, VIM, FN1, ACTA2, SNAI1, SNAI2, ZEB1, ZEB2, TWIST1, TWIST2, MMP-2, MMP-9, NID2, FOXC2) and EMT-TF signature (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, TWIST2, ZEB1, ZEB2, FOXC2, GSC, E47, PRRX1, SOX9, KLF8) were obtained from TCGA (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/), and the resource data sets supported the results can be found in (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).

Statistics analysis

Unless otherwise specified, all statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Parametric data are shown as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and nonparametric data are shown as medians and ranges. Two-way ANOVA or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed for multiple group analysis. Unpaired Student’s t-test was performed to compare data between two groups. Two-tailed P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Fisher’s exact test analysis of the correlations of gene expression between GPX3 and various clinical features. Spearman rank correlation was used to analyze the association of GPX3, TGFB1, and ZEB2 in TNBC tissue samples. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all p values are two-tailed (ns: not significant, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). Other methods were in the Supplementary materials.

Results

GPX3 promoted cisplatin resistance in TNBC

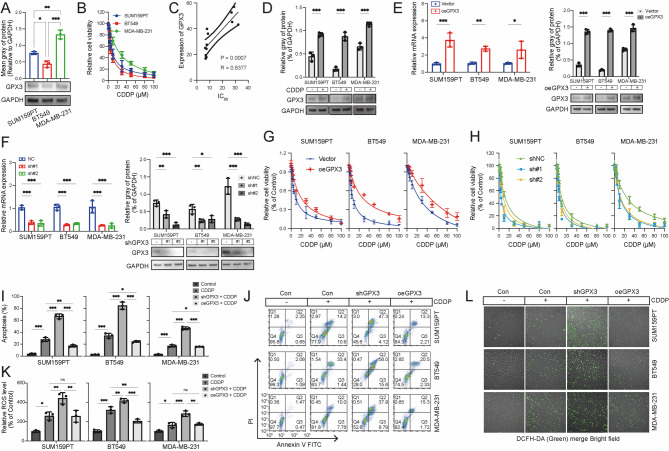

This study aimed to determine whether GPX3 is associated with cisplatin resistance in TNBC. Three human TNBC cell lines (MDA-MB-231, BT-549, and SUM159PT) were employed in this study. GPX3 exhibited the highest protein expression in MDA-MB-231, whereas its expression was relatively lower in BT-549 (Fig. 1A). The viability of all three TNBC cell lines decreased following cisplatin treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Notably, MDA-MB-231 displayed the highest resistance to cisplatin, with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 22.31 µM, whereas BT-549 and SUM159PT exhibited lower IC50 values of 8.31 µM and 9.59 µM, respectively. A significant positive correlation was observed between IC50 values and GPX3 expression (R = 0.8377, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1C). These findings suggested that GPX3 expression may attenuate the antitumor efficacy of cisplatin in TNBC cells. Changes in GPX3 expression following cisplatin treatment were first examined to evaluate whether GPX3 inhibited the efficacy of cisplatin. Western blot analysis revealed that GPX3 protein levels were elevated in all three TNBC cell lines following cisplatin treatment (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

GPX3 promoted cisplatin resistance in TNBC cells. (A) GPX3 protein expression levels in TNBC cell lines were assessed by Western blot. (B) TNBC cells were treated with a gradient of cisplatin concentrations for 48 h, and cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 assay. (C) Correlation analysis between GPX3 expression and cisplatin IC50 values in TNBC cells. (D) TNBC cells were incubated with cisplatin, and GPX3 expression was determined by Western blot. (E-F) Transfection efficiency was evaluated using RT-qPCR and Western blot following GPX3 overexpression or knockdown. (G) CCK-8 assay assessing the effect of GPX3 overexpression on cisplatin resistance or sensitivity in TNBC cells. (H) CCK-8 assay assessing the effect of GPX3 knockdown on cisplatin resistance or sensitivity in TNBC cells. (I) Apoptosis was quantified by flow cytometry after Annexin-V and PI staining following cisplatin treatment. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. (J) Percentage of Annexin-V + apoptotic cells in each group. (K) GPX3 knockdown increased intracellular ROS accumulation following cisplatin treatment, while GPX3 overexpression significantly reduced ROS levels in TNBC cells. (L) Relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DCFH-DA staining, reflecting intracellular ROS levels. (ns P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

To further investigate the role of GPX3 in cisplatin resistance, apoptosis was examined using Annexin V/PI staining. TNBC cells treated with cisplatin at their IC50 concentrations for 48h exhibited both early and late apoptosis. GPX3 knockdown (KD) significantly increased cisplatin-induced apoptosis, with a higher proportion of cells in late apoptosis (Annexin+/PI+) especially in MDA-MB-231 cells. Conversely, GPX3 overexpression reduced cisplatin-induced apoptosis in all three TNBC cell lines (Fig. 1I-J). These findings suggested that GPX3 expression modulated cisplatin sensitivity by regulating apoptotic responses, with high GPX3 levels conferring resistance to cisplatin-induced cell death.

GPX3 possesses antioxidative properties, while elevated ROS levels were critical in CDDP-induced tumor suppression and apoptosis induction. To determine whether GPX3 regulated intracellular ROS levels in response to cisplatin, the fluorescent redox probe DCFH-DA was employed to measure ROS accumulation. These results showed that cisplatin treatment increased intracellular ROS levels in TNBC cells, and this effect was further exacerbated by GPX3 knockdown, while GPX3 overexpression reduced CDDP-induced ROS accumulation (Fig. 1K-L). Next, the contribution of GPX3 knockdown-induced oxidative stress to increased TNBC sensitivity to cisplatin was investigated. The ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was used to counteract the ROS elevation caused by GPX3 depletion. NAC pretreatment significantly reversed the increased intracellular ROS levels (Figure S1A-B), suppressed the proliferation inhibition (Figure S1C), and reduced cell death (Figure S1D-E) in GPX3-depleted TNBC cells treated with cisplatin. These findings suggested that GPX3 was crucial in maintaining redox homeostasis, thereby regulating TNBC cell sensitivity to cisplatin.

To further investigate the impact of GPX3 expression on cisplatin sensitivity in vivo, we utilized a cell-derived xenograft (CDX) model with MDA-MB-231 cells in nude mice. The experimental procedure followed the outlined workflow (Fig. 2A). Compared to the control group, GPX3 knockdown enhanced the inhibitory effect of cisplatin on tumor growth (Fig. 2B-D). While cisplatin treatment caused modest weight reduction by day 30, the magnitude of change from baseline (Δweight) did not significantly differ between groups, suggesting manageable toxicity within ethical limits (Fig. 2E). Tumor cell proliferation was assessed by H&E and Ki67 immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining (Fig. 2F-G). GPX3 knockdown significantly reduced tumor cell proliferation under cisplatin treatment, suggesting that GPX3 may be a potential therapeutic target to enhance the antitumor effects of cisplatin.

Fig. 2.

GPX3 promotes cisplatin resistance in TNBC tumors in vivo. (A) Schematic of the animal experimental workflow. (B) Tumor volume changes over time in xenograft tumors following injection of GPX3-KD and control MDA-MB-231 cells (n = 5 mice per group). (C) Average tumor diameter of xenograft tumors in different treatment groups. (D) Tumor volume and weight of xenograft tumors at the endpoint. (E) Body weight changes in mice before and after treatment in each group. (F-G) Ki67 and GPX3 IHC staining in tumor xenografts and quantitative analysis of tumor cell proliferation. (ns P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

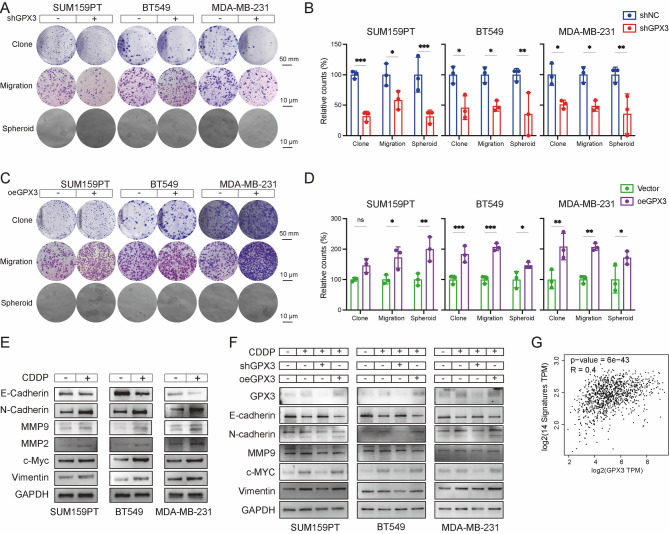

Cisplatin treatment enhanced EMT, relays on GPX3

In human cancers, EMT is a critical cellular process associated with tumor progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance, during which epithelial cells acquire mesenchymal characteristics. To investigate how GPX3 influences the long-term proliferation, metastasis, and stemness potential of TNBC cells under cisplatin treatment, colony formation, Transwell, and spheroid formation assays were performed (Fig. 3A-D). GPX3 knockdown impaired colony formation, cell migration, and spheroid formation in three tested TNBC cell lines following cisplatin treatment, while GPX3 overexpression enhanced these properties. These findings suggested that GPX3 was essential for clonal growth, metastasis, and stemness of TNBC cells under cisplatin-induced stress.

Fig. 3.

GPX3-dependent enhancement of EMT in cisplatin-treated TNBC cells. (A-D) Colony formation, Transwell migration, and Spheroid formation assays demonstrated that GPX3 knockdown inhibited proliferation, migration, and stemness of TNBC cells following cisplatin treatment, whereas GPX3 overexpression had opposite effects and corresponding quantitative analysis. (E) Western blot analysis of EMT markers’ expression in TNBC cells from control and cisplatin-treated groups. (F) Western blot analysis of EMT markers’ expression in TNBC cells transfected for 48 h with either a negative control, GPX3-shRNA, or a GPX3 overexpression plasmid, in both control and cisplatin-treated groups. (G) Correlation analysis between mesenchymal markers and GPX3 expression using the GEPIA online tool. (ns P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Treatment of SUM159PT, MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 with cisplatin at their IC50 concentrations for 24 h decreased the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin while increasing the expression of mesenchymal markers, including N-cadherin, MMP9, MMP2, c-Myc, and Vimentin (Fig. 3E, Figure S2). To investigate how GPX3 expression influences EMT and CDDP resistance in TNBC, the expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers was examined in three human TNBC cell lines with altered GPX3 expression. During cisplatin treatment, GPX3 overexpression further promoted mesenchymal markers, whereas GPX3 knockdown reversed cisplatin-induced EMT (Fig. 3F, Figure S3). Additionally, analysis using the GEPIA online tool confirmed a significant positive correlation between GPX3 expression and mesenchymal markers (14-signature: CDH2, VIM, FN1, ACTA2, SNAI1, SNAI2, ZEB1, ZEB2, TWIST1, TWIST2, MMP2, MMP9, NID2, and FOXC2) (Fig. 3G). These findings suggested that higher GPX3 expression during cisplatin treatment promoted EMT, thereby enhancing TNBC cell metastasis and stemness, ultimately contributing to cisplatin resistance.

Response to transcriptional changes induced by GPX3 knockdown

To determine how GPX3 influences the cisplatin sensitivity and intrinsic gene expression in TNBC cells, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on GPX3 knockdown and control MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 4A). Compared to NC, in the GPX3-KD cells, 218 genes were downregulated and 85 genes were upregulated. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed that GPX3 expression correlated with the expression of several cancer-related gene signatures, particularly those involved in metabolism and biosynthesis, as well as the associated signaling pathways, including TGF-beta, Rho GTPases, and PI3K-AKT (Fig. 4B). Analysis of validated transcription factor binding data (ChEA, ENCODE) showed that genes downregulated upon GPX3 knockdown included MYC (stemness), MAX (metabolism), USF2 (immune, metabolism), and MAFK (stress response) (Fig. 4C). Further analysis of small molecule gene expression signatures indicated that GPX3 knockdown largely mimicked the gene regulation effects of MEK, PI3K, and mTOR inhibition (Fig. 4D). However, Narcilasine and Chaetocin reversed GPX3-KD signature (Fig. 4E) These results suggested that GPX3 expression influenced tumor-promoting pathways involved in stress responses and metabolism.

Fig. 4.

Transcriptional changes in response to GPX3 knockdown. (A) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between GPX3 knockdown and control-transfected MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Gene enrichment analysis of RNA-seq data after GPX3 knockdown indicates enrichment of tumor-associated metabolic and biosynthetic pathways in control cells compared to GPX3 knockdown cells. (C) Transcription factor enrichment analysis of RNA-seq data after GPX3 knockdown (ChEA, ARCHS4, and ENCODE). (D-E) Small molecule query identifying gene expression signatures that mimic or reverse the gene expression changes induced by GPX3 knockdown

The transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway plays a dual role in cancer development, acting as a tumor suppressor in the early stage while promoting tumor metastasis and drug resistance in the later stages [32, 33]. This dual-function is similar to the behavior of GPX3. TGF-β is a key factor in promoting EMT and enhancing tumor cells’ resistance to chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin through various mechanisms [34–36]. By inducing EMT, TGF-β increased tumor cells resistant to chemotherapy. Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether GPX3-mediated cisplatin resistance is linked to the TGF-β signaling pathway.

Cisplatin enhanced TGF-β signaling, dependent on GPX3 expression

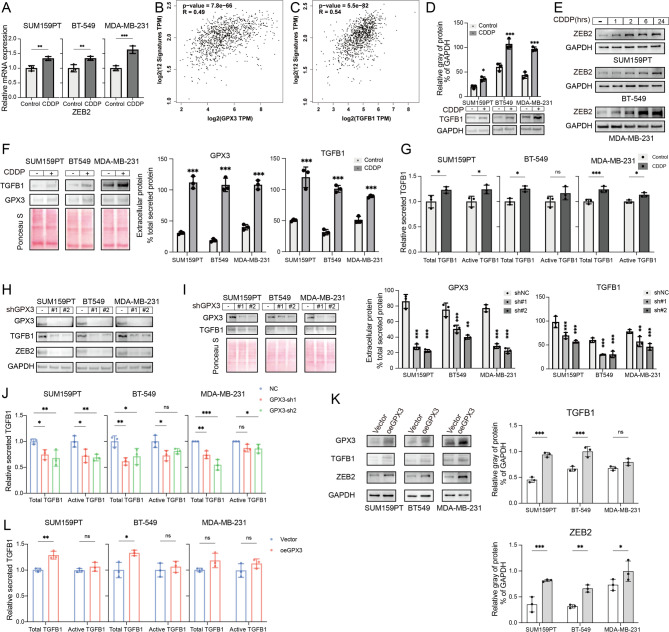

Previous studies have shown that cisplatin treatment increased the expression of EMT-related molecules, whereas GPX3 knockdown reversed this effect (Fig. 3E-F). The EMT process is regulated by EMT-TFs. Recent studies suggested that EMT-TFs can mediate chemotherapy resistance. For example, ZEB2 has been shown to drive PI3K/AKT signaling, promoting cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer [37]. ZEB1 promoted integrin signaling and enhanced gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells [38]. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that cisplatin enhanced the transcription of EMT-TFs (Figure S4) in TNBC cells, particularly ZEB2 (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Cisplatin treatment enhances TGFB1 and ZEB2 expression, dependent on GPX3 expression. (A) RT-qPCR analysis showed that cisplatin treatment enhanced the transcription of ZEB2. (B) GEPIA tool analysis of the relationship between EMT-TFs and GPX3 expression. (C) GEPIA tool analysis of the relationship between EMT and EMT-TF signatures and TGFB1 expression. (D) Western blot analysis of TGFB1 protein expression in TNBC cells after cisplatin treatment. (E) Western blot analysis of ZEB2 protein expression in TNBC cells after cisplatin treatment. (F-G) Western blot and ELISA analysis of secreted TGFB1 and GPX3 levels in the culture supernatant of TNBC cells after cisplatin treatment. (H) Western blot analysis of TGFB1 and ZEB2 expression in the control and cisplatin-treated groups, 48 hours post-transfection with negative control or GPX3-shRNA. (I-J) Western blot and ELISA analysis of secreted total and active TGFB1 levels in the culture supernatants of the NC and GPX3-KD cells after cisplatin treatment. (K) Western blot analysis examined the effect of overexpression of GPX3 on the upregulation of TGFB1 and ZEB2 induced by cisplatin. (L) ELISA analysis examined the effect of overexpression of GPX3 on secreted total and active TGFB1 level. (ns P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

GEPIA analysis revealed a positive correlation between EMT-TF 12-signature (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, TWIST2, ZEB1, ZEB2, FOXC2, GSC, E47, PRRX1, SOX9, KLF8) and GPX3 expression (Fig. 5B), with the strongest correlation observed between ZEB2 and GPX3 (Table 1). ZEB2, a member of the zinc finger E-box binding protein family, primarily activates mesenchymal marker gene expression and inhibits epithelial marker gene expression, thereby promoting EMT and enhancing cancer cell migration and invasion [20, 39, 40]. Previous studies have shown that TGF-β/Smad signaling was a key regulator of EMT, and ZEB2 expression is positively regulated by TGF-β signaling [27]. GEPIA analysis further confirmed the positive correlation between EMT and EMT-TF signatures and TGFB1 expression (Fig. 5C; Table 1).

Table 1.

GEPIA analysis the correlation between GPX3, TGFB1 and EMT-TF 12-signature

| EMT-TF | GPX3 | TGFB1 | GPX3 + TGFB1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | p-value | R | p-value | R | p-value | |

| E47 | 0.074 | 0.014 | 0.080 | 0.0083 | 0.007 | 0.820 |

| FOXC2 | 0.070 | 0.021 | 0.070 | 0.022 | 0.024 | 0.420 |

| GSC | 0.130 | <0.001 | 0.130 | <0.001 | 0.064 | 0.034 |

| KLF8 | 0.130 | <0.001 | 0.024 | 0.42 | 0.080 | 0.009 |

| PRRX1 | 0.380 | <0.001 | 0.410 | <0.001 | 0.160 | <0.001 |

| SNAI1 | 0.220 | <0.001 | 0.290 | <0.001 | 0.170 | <0.001 |

| SNAI2 | 0.280 | <0.001 | 0.360 | <0.001 | 0.130 | <0.001 |

| SOX9 | -0.047 | 0.120 | -0.170 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.810 |

| TWIST1 | 0.140 | <0.001 | 0.190 | <0.001 | 0.093 | 0.002 |

| TWIST2 | 0.500 | <0.001 | 0.380 | <0.001 | 0.400 | <0.001 |

| ZEB1 | 0.440 | <0.001 | 0.320 | <0.001 | 0.260 | <0.001 |

| ZEB2 | 0.580 | <0.001 | 0.500 | <0.001 | 0.410 | <0.001 |

We examined the changes in TGFB1 and ZEB2 expression in TNBC cells following cisplatin treatment and found that, compared to the control, the protein levels of TGFB1 and ZEB2 were elevated (Fig. 5D-E, Figure S5), with ZEB2 expression increasing over time. The level of secreted TGFB1 and GPX3 were also increased (Fig. 5F-G). Similarly, GPX3 knockdown blocked the cisplatin-induced upregulation of TGFB1 and ZEB2 expression (Fig. 5H, Figure S6) and reduced secreted TGFB1 (Fig. 5I-J). We next investigated the effect of overexpression of GPX3 on the activation of the TGF-β pathway induced by cisplatin. Indeed, GPX3 overexpression slightly increased the expression levels of TGFB1 and ZEB2 in SUM159PT and BT-549 cells, but had little effect on MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 5K, Figure S7). Additionally, the supernatants of SUM159PT and BT-549 cells with overexpressed GPX3 showed an increase in the content of activated TGFB1 after cisplatin treatment, while the total TGFB1 levels did not significantly change in the supernatants of the three TNBC cells (Fig. 5L). Overall, these results suggested that CDDP-induced EMT and TGF-β signaling depended on GPX3 expression.

GPX3 enhanced TGF-β signaling

We further explored how GPX3 affects TGFβ signaling. We compared GPX3-KD and NC MDA-MB-231 cells treated with or without recombinant human TGFβ1 protein (rhTGFβ1) for 8 h. RT-qPCR analysis showed that, compared to the control treatment, rhTGFβ1 significantly increased TGFB1, MMP9, ZEB2, and Vimentin levels in NC cells (Fig. 6A). However, there were no significant differences between GPX3-KD cells treated with or without rhTGFβ1 (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, Western blot analysis demonstrated that in NC cells treated with rhTGFβ1, the levels of TGFB1 and p-SMAD2/3 were elevated, exhibiting a TGF-β-dependent EMT phenotype (Fig. 6C). Similarly, no significant differences were observed between rhTGFβ1-treated and untreated GPX3-KD cells (Fig. 6C). These results indicated that the expression of GPX3 promoted TGF-β signaling.

Fig. 6.

GPX3 enhanced TGF-β1 signaling following cisplatin treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A-B) RT-qPCR analysis of TGFB1 signaling and its EMT marker expression levels in cells transfected with NC or GPX3-KD, treated with or without rhTGFβ1. (C) Western blot analysis of TGFB1 signaling and EMT marker expression levels in cells transfected with NC or GPX3-KD, treated with or without rhTGFβ1. (D-E) Immunofluorescence staining for SMAD2 and SMAD3 in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments of NC and GPX3-KD cells treated with rhTGFβ1, with corresponding quantification. (F) Western blot analysis of the ratio of phosphorylated SMAD2/3 (p-SMAD2/3) to total SMAD2 and SMAD3 in NC and GPX3-KD cells treated with rhTGFβ1. (G-H) Secretion levels of total and active TGFB1 in the supernatants of GPX3-KD cells incubated with cisplatin, with or without NAC pre-treatment, as detected by Western blot and ELISA. (I) Western blot analysis of TGF-β signaling and EMT marker expression in GPX3-KD cells, with or without NAC pre-treatment. (ns P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Furthermore, we continued to investigate the involvement of GPX3 in the TGFB1/SMAD signaling pathway. Nuclear translocation assays were performed on shGPX3 or NC MDA-MB-231 cells treated with or without rhTGFβ1 for 2 h. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that SMAD2/3 was detected in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of NC and GPX3-KD cells. The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (ratioS2 + 3) was 3.18 in NC cells and 1.37 in GPX3-KD cells, with only trace amounts of SMAD2/3 detected in the nucleus of GPX3-KD cells, significantly lower than in NC cells. After 2 h of rhTGFβ1 treatment, SMAD2/3 levels in the nucleus were increased, with ratioS2 + 3 values of 8.06 and 2.56 in NC and GPX3-KD cells, respectively (Fig. 6D-E). Immunoblotting results showed that rhTGFβ1 increased the proportion of phosphorylated SMAD2/3 (p-SMAD2/3) in NC cells, while its effect on GPX3-KD cells was much smaller (Fig. 6F). During TGF-β signaling activation, SMAD complexes composed of SMAD4 and p-SMAD2/3 translocated to the nucleus to regulate the expression of downstream target genes [41]. Knockdown of GPX3 significantly impaired the TGFB1/SMAD cascade, including the phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 and nuclear translocation.

Given the role of GPX3 in scavenging toxic ROS and maintaining cellular redox balance and the previous finding that NAC reversed the increased sensitivity of GPX3-KD cells to cisplatin, it is hypothesized that GPX3 may also promote enhanced EMT and TGF-β signaling during cisplatin treatment through its antioxidant function. GPX3 knockdown reversed the effect of cisplatin on TGFB1 expression, while the addition of NAC restored this effect, including the expression of TGFB1 and both the total and active levels of secreted TGFB1 (Fig. 6G-H). Furthermore, pretreatment with NAC in GPX3-KD cells improved TGF-β signaling, as evidenced by the increased expression of TGFB1, p-SMAD2/3, and EMT markers (Fig. 6I). This underscored the critical role of GPX3-mediated antioxidant systems in regulating TGFB1 expression and TGF-β/EMT signaling.

GPX3-TGFB1-ZEB2 enhanced EMT in TNBC during CDDP treatment

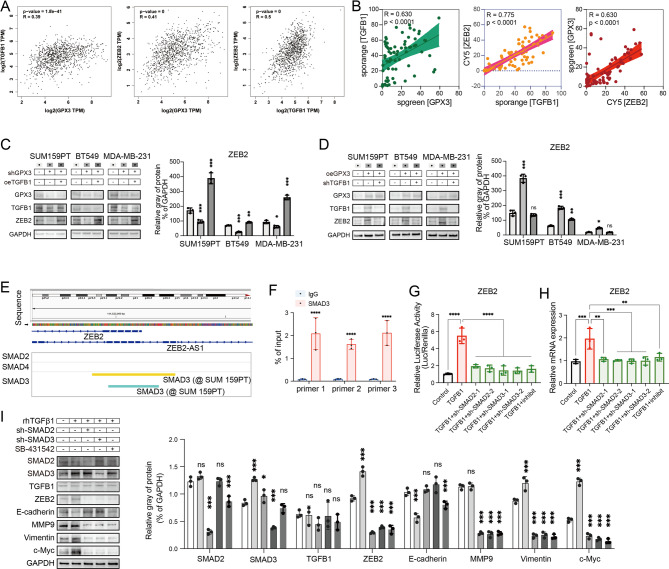

To identify the GPX3-TGF-β1-SMAD2/3-ZEB2 signaling axis in TNBC, we examined the expression levels of GPX3, TGFB1, and ZEB2 in the TCGA-BRCA dataset, revealing a positive correlation (Fig. 7A; Table 1). Clinical tissue microarrays were used to further confirm the correlation between GPX3, TGFB1, and ZEB2 expression in breast cancer (Fig. 7B). Western blot analysis showed that overexpression of TGFB1 reversed the downregulation of ZEB2 induced by GPX3 knockdown in MDA-MB-231, and vice versa (Fig. 7C-D). These data suggested that GPX3 activated ZEB2 via TGFB1.

Fig. 7.

GPX3-TGFB1 promoted ZEB2 expression and enhanced EMT during cisplatin treatment in TNBC. (A) GEPIA analysis of the relationship between the expression of GPX3, TGFB1, and ZEB2. (B) Correlation analysis of the protein expression levels of GPX3, TGFB1, and ZEB2 in TNBC patient tissue microarrays (n=75). (C-D) Western blot analysis showed that TGFB1 reversed the effect of GPX3 on ZEB2 expression. (E) Existing ChIP-seq analysis of SMAD3 binding sites on the ZEB2 gene promoter (ChiP-Atlas: Enrichment Analysis, https://chip-atlas.org/enrichment_analysis). (F) ChIP-qPCR validation of SMAD3 enrichment at the ZEB2 gene promoter. (G-I) Knocking down SMAD2 or SMAD3 or inhibiting TGFBR1 kinase activity abolished rhTGFβ1-induced transcriptional activity (G), expression level of ZEB2 (H), and EMT markers (I). (ns P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Analysis of existing ChIP-Seq Data (ChiP-Atlas: Enrichment Analysis, https://chip-atlas.org/enrichment_analysis) revealed that SMAD3 binds to two regions on the ZEB2 gene in SUM159PT cells: chr2:144519892–144,520,270 (378 bp) and chr2:144519965–144,520,196 (231 bp) (Fig. 7E, Figure S8). Under normal physiological conditions, the SMAD complex was present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of highly invasive TNBC cells, where it promoted ZEB2 expression by interacting with the ZEB2 gene promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-qPCR) experiments were performed to confirm that the SMAD2/3 complex was recruited to the ZEB2 promoter (Fig. 7F). In cells expressing GPX3, knocking down SMAD2 (sh-Smad2) or SMAD3 (sh-Smad3), or inhibiting TGFBR1 kinase activity using SB-431,542, reduced rhTGFβ1-induced transcriptional activity (Fig. 7G), ZEB2 expression (Fig. 7H), and EMT markers expression levels (Fig. 7I).

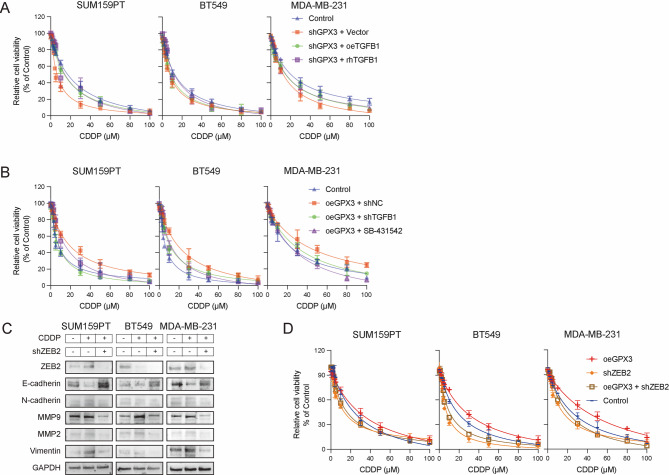

GPX3-TGFB1-ZEB2 enhanced acquired cisplatin resistance in TNBC

Finally, we explored the role of the GPX3-TGFB1-ZEB2 signaling axis in acquired cisplatin resistance. We found that the addition of rhTGFβ1 or overexpression of TGFB1 enhanced cisplatin resistance in GPX3-KD cells (Fig. 8A). In contrast, in cells with normal GPX3 expression, treatment with SB-431,542 significantly reduced cell viability under cisplatin treatment, and knockdown of TGFB1 similarly increased the sensitivity of the cells to cisplatin (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

GPX3-TGFB1-ZEB2 enhanced acquired cisplatin resistance in TNBC. (A) CCK-8 assay showed that overexpression or activation of TGFB1 reversed cisplatin sensitivity in GPX3-KD cells. (B) CCK-8 assay demonstrated that knockdown or inhibition of TGFB1 increased cisplatin sensitivity in cells with normal GPX3 expression. (C) Targeted knockdown of ZEB2 in TNBC cells prevented the cisplatin-induced enhancement of EMT. (D) Targeted knockdown of ZEB2 increased cisplatin sensitivity in TNBC cells

In cells with normal GPX3 expression, cisplatin treatment upregulated the expression of mesenchymal markers and downregulated E-cadherin. Targeted knockdown of ZEB2 reversed these effects (Fig. 8C) and increased the sensitivity of TNBC cells to cisplatin (Fig. 8D). These results suggested that GPX3-TGFB1-ZEB2-mediated EMT contributed to the EMT process and cisplatin resistance in TNBC cells.

Discussion

Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy remains the primary comprehensive treatment for TNBC [5]. Investigating the mechanisms underlying cisplatin-based chemotherapy resistance is crucial for mitigating resistance and improving therapeutic efficacy. Previous studies have reported an association between GPX3 and cisplatin resistance [42–44]; however, the precise mechanism remains unclear. In this study, RNA-seq analysis revealed that GPX3 induced TGFB1 expression, thus promoting TGF-β/SMAD signaling. We demonstrated that GPX3 served as a key determinant of enhanced TGF-β/Smad signaling in TNBC during cisplatin treatment, contributing to treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients.

Platinum-based chemotherapy effectively combated tumors by inducing DNA crosslinking, disrupting DNA secondary structures, and triggering apoptosis [6]. Additionally, platinum-based drugs induced the production of ROS, leading to DNA damage, cell cycle arrest, and increased chemotherapy sensitivity [7]. Despite these effects, tumor cells can develop resistance to platinum-based drugs through various mechanisms [45, 46]. In this study, differential sensitivity to CDDP was observed among TNBC cell lines (BT-549, SUM159PT, and MDA-MB-231). Notably, MDA-MB-231 cells, which exhibited high GPX3 expression, displayed the strongest resistance to cisplatin, with only a mild increase in ROS levels following treatment. These findings suggested that GPX3 provided a survival advantage to tumor cells under cisplatin-induced oxidative stress. Under cisplatin exposure, GPX3 was crucial for maintaining transcriptional programs associated with pro-tumorigenic metabolism and biosynthesis. The expression of the TGF-β/SMAD/ZEB2, which promoted EMT and stemness, was highly dependent on GPX3 during cisplatin treatment. GPX3 depletion inhibited cisplatin-induced TGF-β signaling, while under normal or upregulated GPX3 function, cisplatin-induced oxidative stress enhanced TGFB1 expression and downstream signaling. In our experiments, GPX3 overexpression enhanced cisplatin-induced TGF-β signaling activation in BT-549 and SUM159PT, but its effect was minimal in MDA-MB-231 cells. We proposed this differential response stems from their distinct basal GPX3 expression levels. In MDA-MB-231, the native GPX3 activity may already be sufficient to scavenge cisplatin-generated ROS and maintain the redox balance required for proper TGF-β signaling activation. Therefore, additional GPX3 overexpression provided little further benifit. In contrast, BT-549 and SUM159PT got benifit from GPX3 supplement. However, GPX3 may be just one component of a larger redox-sensing network governing TGF-β activation. Further studies should explore potential synergies between GPX3 and other antioxidant systems in mediating cisplatin response.

Like many antioxidant enzymes, GPX3 exhibited dual functions: protecting cells from oxidative damage under normal conditions and promoting cancer cell survival during tumor progression [47, 48]. Some of GPX3’s immunomodulatory functions may be associated with its antioxidant activity within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [49, 50]. Upregulation of TGFB1 expression was commonly observed in fibrosis, inflammatory diseases, cardiovascular disorders, and cancers [51]. It is induced by various stress responses, including oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and inflammation [52, 53]. Given this, it was surprising that GPX3 depletion, which increased cellular stress, leads to a reduction in TGFB1 expression. However, pathway analysis of RNA-seq data following GPX3 knockdown revealed a strong association with TGFB1-related regulatory pathways, including HSF1-mediated heat shock response, cellular stress responses, extracellular matrix (ECM) components (collagen formation, collagen biosynthesis, and modifying enzymes, elastic fiber formation), and the TGF-β signaling pathway. Interestingly, no significant enrichment of oxidative stress-related pathways was observed in GPX3-depleted cells, as might have been expected. These findings suggested that, in addition to preventing excessive oxidative stress, GPX3 may have other functions. Our RNA-seq analyses revealed that GPX3 modulated oncogenic pathways, include stress response pathways and core metabolic process, particularly through its integration with key cancer-related signaling axes including TGF-beta, Rho GTPases, and PI3K-AKT. In this study, we identified that GPX3 maintains TGF-β signaling activation under oxidative stress conditions induced by cisplatin. It is reported that TGF-β-SMAD signaling activated the AKT/ GSK-3β pathway to promote the conversion of glucose to glycolysis, and participating in EMT and fibrosis [54–56]. The RhoA signal promoted the nuclear translocation of YAP, thereby promoting cancer cell invasion [57, 58]. Additionally, GPX3, as a selenium protein, may affect the activity of PI3K-AKT by influencing selenium metabolism, and subsequently influenced the transcription of downstream genes [59, 60]. Overall, we speculated that GPX3 may alter the metabolic pathways and products in the TME through its oxidative regulatory function, including the metabolic processes of glycogen, cholesterol, and selenium, thereby regulating downstream transcriptional changes.

Although the focus was on manipulating GPX3 expression within tumor cells, extracellular GPX3 in the TME may also originated from tumor-associated cells. Previous studies have shown that type II alveolar epithelial cells near the tumor interface contributed to GPX3 expression, which was crucial for metastatic colonization in the lungs [48, 49]. Additionally, GPX3 was enriched in the stroma of lung and gastric cancers, where it has been reported to promote chemoresistance and immune evasion [61]. However, the impact of tumor-associated cells on extracellular GPX3 and its role in breast cancer progression remains unclear.

Considering all the findings from this study, we proposed a potential mechanism by which GPX3 enhanced cisplatin resistance: (1) GPX3 maintained redox homeostasis during cisplatin treatment, where GPX3 depletion sensitized cisplatin-resistant TNBC cells to treatment, thereby improving cisplatin-induced toxicity against both resistant and low-sensitivity cells. (2) GPX3 depletion prolonged and enhanced cisplatin toxicity. Cisplatin induced immediate apoptosis through DNA damage, while prolonged treatment increased ROS accumulation. GPX3 depletion facilitated ROS accumulation-induced apoptosis, thereby augmenting both immediate cell death and delayed toxicity caused by cisplatin. (3) In cisplatin-resistant or low-sensitivity TNBC cells, TGFβ signaling and EMT were upregulated under cisplatin treatment, contributing to acquired resistance. This process depended on GPX3, which provided a robust antioxidant background to support EMT and resistance.

Conclusion

This study provided evidence that GPX3 can serve as a predictive biomarker for cisplatin response in TNBC. Targeting GPX3 may serve as a potential cisplatin sensitization strategy, supporting its integration into cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens to improve the efficacy of targeted chemotherapy in breast cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the technical support by the Medical sub-center of Huazhong University of Science &Technology Analytical & Testing center. We thank the Experimental Animal Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for support of animal experiments.

Author contributions

Q. Hu, and Q. Chen designed and performed most experiments and analyzed the data. W. Yang and A. Ren performed some bioinformatics and immunofluorescence image analyses, respectively. J. Tan and T. Huang directed and coordinated study, designed the research, and oversaw the project. Q. Hu, Q. Chen, J. Tan and T. Huang wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (No. 82002834) and Grant (No.82303780).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experimentation in this study was performed following the Guidelines of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of HUST (Number: 2551).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qingyi Hu and Qianzhi Chen authors contributed equally.

Lead contact: Tao Huang.

Contributor Information

Jie Tan, Email: tj505_210@126.com.

Tao Huang, Email: huangtaowh@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12–49. 10.3322/caac.21820. Epub 2024/01/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbeck N, Gnant M, Breast, Cancer. Lancet. 2017;389(10074):1134–50. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31891-8. Epub 2016/11/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Zhang H, Merkher Y, Chen L, Liu N, Leonov S, et al. Recent advances in therapeutic strategies for Triple-Negative breast Cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):121. 10.1186/s13045-022-01341-0. Epub 2022/08/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders ME, Gianni L. Triple-Negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(11):674–90. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.66. Epub 2016/10/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu Y, Hu Y, Tang C, Guan X, Zhang W. Platinum-Based systematic therapy in Triple-Negative breast Cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022;1877(1):188678. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188678. Epub 2022/01/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin S, Guo Y, Guo Z, Wang X. Monofunctional Platinum(Ii) Anticancer Agents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) (2021) 14(2). Epub 2021/02/11. 10.3390/ph14020133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mirzaei S, Hushmandi K, Zabolian A, Saleki H, Torabi SMR, Ranjbar A, et al. Elucidating role of reactive oxygen species (Ros) in cisplatin chemotherapy: A focus on molecular pathways and possible therapeutic strategies. Molecules. 2021;26(8). 10.3390/molecules26082382. Epub 2021/05/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Bansal A, Simon MC. Glutathione metabolism in Cancer progression and treatment resistance. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(7):2291–8. 10.1083/jcb.201804161. Epub 2018/06/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilchis-Landeros MM, Vázquez-Meza H, Vázquez-Carrada M, Uribe-Ramírez D, Matuz-Mares D. Antioxidant Enzymes and Their Potential Use in Breast Cancer Treatment. Int J Mol Sci (2024) 25(11). Epub 2024/06/19. 10.3390/ijms25115675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Nirgude S, Choudhary B. Insights into the Role of Gpx3, a Highly Efficient Plasma Antioxidant, in Cancer. Biochem Pharmacol (2021) 184:114365. Epub 2020/12/15. 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114365 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhang N, Liao H, Lin Z, Tang Q. Insights into the role of glutathione peroxidase 3 in Non-Neoplastic diseases. Biomolecules. 2024;14(6). 10.3390/biom14060689. Epub 2024/06/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Chang C, Cheng YY, Kamlapurkar S, White S, Tang PW, Elhaw AT, et al. Gpx3 supports ovarian Cancer tumor progression in vivo and promotes expression of Gdf15. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;185:8–16. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2024.02.004. Epub 2024/02/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Worley BL, Kim YS, Mardini J, Zaman R, Leon KE, Vallur PG, et al. Gpx3 supports ovarian Cancer progression by manipulating the extracellular redox environment. Redox Biol. 2019;25:101051. 10.1016/j.redox.2018.11.009. Epub 2018/12/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Q, Chen J, Yang W, Xu M, Zhou J, Tan J, et al. Gpx3 expression was Down-Regulated but positively correlated with poor outcome in human cancers. Front Oncol. 2023;13:990551. 10.3389/fonc.2023.990551. Epub 2023/02/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Gowily AH, Loutfy SA, Ali EMM, Mohamed TM, Mansour MA. Tioconazole and chloroquine act synergistically to combat Doxorubicin-Induced toxicity via inactivation of Pi3k/Akt/Mtor signaling mediated Ros-Dependent apoptosis and autophagic flux Inhibition in Mcf-7 breast Cancer cells. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14(3). 10.3390/ph14030254. Epub 2021/04/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 16.Ji S, Ma Y, Xing X, Ge B, Li Y, Xu X, et al. Suppression of Cd13 enhances the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapeutic drugs in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:660377. 10.3389/fphar.2021.660377. Epub 2021/05/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grasset EM, Dunworth M, Sharma G, Loth M, Tandurella J, Cimino-Mathews A, et al. Triple-Negative breast Cancer metastasis involves complex Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition dynamics and requires vimentin. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(656):eabn7571. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn7571. Epub 2022/08/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontana R, Mestre-Farrera A, Yang J. Update on Epithelial-Mesenchymal plasticity in Cancer progression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2024;19:133–56. 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-051222-122423. Epub 2023/09/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastushenko I, Blanpain C. Emt transition States during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29(3):212–26. 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.12.001. Epub 2018/12/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saitoh M. Transcriptional regulation of Emt transcription factors in Cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2023;97:21–9. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.10.001. Epub 2023/10/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano-Gomez SJ, Maziveyi M, Alahari SK. Regulation of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition through Epigenetic and Post-Translational Modifications. Mol Cancer. 2016. 10.1186/s12943-016-0502-x. Epub 2016/02/26. 15:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Krebs AM, Mitschke J, Lasierra Losada M, Schmalhofer O, Boerries M, Busch H, et al. The Emt-Activator Zeb1 is a key factor for cell plasticity and promotes metastasis in pancreatic Cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(5):518–29. 10.1038/ncb3513. Epub 2017/04/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan AQ, Hasan A, Mir SS, Rashid K, Uddin S, Steinhoff M. Exploiting transcription factors to target Emt and Cancer stem cells for tumor modulation and therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2024;100:1–16. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2024.03.002. Epub 2024/03/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng Z, Fan T, Xiao C, Tian H, Zheng Y, Li C, et al. Tgf-Β signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):61. 10.1038/s41392-024-01764-w. Epub 2024/03/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Zhang Z, Huang Z, Li M, Yang F, Wu Z, et al. Isotoosendanin exerts Inhibition on Triple-Negative breast Cancer through abrogating Tgf-Β-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition via directly targeting Tgfβr1. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(7):2990–3007. 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.006. Epub 2023/07/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-Dependent and Smad-Independent pathways in Tgf-Beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425(6958):577–84. 10.1038/nature02006. Epub 2003/10/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh HW, Hsu EC, Lee SS, Lang YD, Lin YC, Chang CY, et al. Pspc1 mediates Tgf-Β1 autocrine signalling and Smad2/3 target switching to promote emt, stemness and metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(4):479–91. 10.1038/s41556-018-0062-y. Epub 2018/03/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juarez I, Gutierrez A, Vaquero-Yuste C, Molanes-López EM, López A, Lasa I, et al. Tgfb1 polymorphisms and Tgf-Β1 plasma levels identify gastric adenocarcinoma patients with lower survival rate and disseminated disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25(2):774–83. 10.1111/jcmm.16131. Epub 2020/12/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecker LSM, Berlato C, Maniati E, Delaine-Smith R, Pearce OMT, Heath O, et al. Tgfbi production by macrophages contributes to an immunosuppressive microenvironment in ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021;81(22):5706–19. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-21-0536. Epub 2021/09/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan H, Luo B, Wu X, Guan F, Yu X, Zhao L, et al. Cisplatin induces pyroptosis via activation of Meg3/Nlrp3/Caspase-1/Gsdmd pathway in Triple-Negative breast Cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(10):2606–21. 10.7150/ijbs.60292. Epub 2021/07/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian C, Yang C, Tang Y, Zheng W, Zhou Y, Zhang S, et al. Pharmacological manipulation of Ezh2 with Salvianolic acid B results in tumor vascular normalization and synergizes with cisplatin and T Cell-Mediated immunotherapy. Pharmacol Res. 2022;182:106333. 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106333. Epub 2022/07/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao M, Mishra L, Deng CX. The role of Tgf-Β/Smad4 signaling in Cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14(2):111–23. 10.7150/ijbs.23230. Epub 2018/02/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colak S, Ten Dijke P. Targeting Tgf-Β signaling in Cancer. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(1):56–71. 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.11.008. Epub 2017/07/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyazono K. Transforming growth Factor-Beta signaling in Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition and progression of Cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2009;85(8):314–23. 10.2183/pjab.85.314. Epub 2009/10/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu H, Gu X, Xia L, Zhou Y, Bouamar H, Yang J, et al. A novel Tgfβ trap blocks Chemotherapeutics-Induced Tgfβ1 signaling and enhances their anticancer activity in gynecologic cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(12):2780–93. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-3112. Epub 2018/03/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Z, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Sun W, Yung MMH, Sun J, et al. Erk regulates Hif1α-Mediated platinum resistance by directly targeting Phd2 in ovarian Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5947–60. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-4145. Epub 2019/07/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu DM, Zhang T, Liu YB, Deng SH, Han R, Liu T, et al. The Pax6-Zeb2 Axis promotes metastasis and cisplatin resistance in Non-Small cell lung Cancer through Pi3k/Akt signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(5):349. 10.1038/s41419-019-1591-4. Epub 2019/04/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu M, Zhang Y, Yang J, Cui X, Zhou Z, Zhan H, et al. Zip4 increases expression of transcription factor Zeb1 to promote integrin Α3β1 signaling and inhibit expression of the gemcitabine transporter Ent1 in pancreatic Cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):679–e692671. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.038. Epub 2019/11/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fardi M, Alivand M, Baradaran B, Farshdousti Hagh M, Solali S. The crucial role of Zeb2: from development to Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal transition and Cancer complexity. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(9):14783–99. 10.1002/jcp.28277. Epub 2019/02/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan JH, Yang F, Wang F, Ma JZ, Guo YJ, Tao QF, et al. A long noncoding Rna activated by Tgf-Β promotes the Invasion-Metastasis cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(5):666–81. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.010. Epub 2014/04/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guan Y, Li J, Sun B, Xu K, Zhang Y, Ben H, et al. Hbx-Induced upregulation of Map1s drives hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and migration via Map1s/Smad/Tgf-Β1 loop. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;281(Pt 3):136327. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136327. Epub 2024/10/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saga Y, Ohwada M, Suzuki M, Konno R, Kigawa J, Ueno S, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 3 is a candidate mechanism of anticancer drug resistance of ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2008;20(6):1299–303. Epub 2008/11/21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen B, Rao X, House MG, Nephew KP, Cullen KJ, Guo Z. Gpx3 promoter hypermethylation is a frequent event in human Cancer and is associated with tumorigenesis and chemotherapy response. Cancer Lett. 2011;309(1):37–45. 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.05.013. Epub 2011/06/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelosof L, Yerram S, Armstrong T, Chu N, Danilova L, Yanagisawa B, et al. Gpx3 promoter methylation predicts platinum sensitivity in colorectal Cancer. Epigenetics. 2017;12(7):540–50. 10.1080/15592294.2016.1265711. Epub 2016/12/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li F, Zheng Z, Chen W, Li D, Zhang H, Zhu Y, et al. Regulation of cisplatin resistance in bladder Cancer by epigenetic mechanisms. Drug Resist Updat. 2023;68:100938. 10.1016/j.drup.2023.100938. Epub 2023/02/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferreira JA, Peixoto A, Neves M, Gaiteiro C, Reis CA, Assaraf YG, et al. Mechanisms of cisplatin resistance and targeting of Cancer stem cells: adding glycosylation to the equation. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;24:34–54. 10.1016/j.drup.2015.11.003. Epub 2016/02/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Qi H, Liu Y, Duan C, Liu X, Xia T, et al. The Double-Edged roles of Ros in Cancer prevention and therapy. Theranostics. 2021;11(10):4839–57. 10.7150/thno.56747. Epub 2021/03/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan M, Lin J, Wang B, Chen C, Huang Z, Tian Y, et al. A novel Necroptosis-Related gene index for predicting prognosis and a cold tumor immune microenvironment in stomach adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:968165. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.968165. Epub 2022/11/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Z, Zhu J, Liu Y, Wang Z, Cao X, Gu Y. Tumor-Polarized Gpx3(+) At2 lung epithelial cells promote premetastatic niche formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(32):e2201899119. 10.1073/pnas.2201899119. Epub 2022/08/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rice SJ, Roberts JB, Tselepi M, Brumwell A, Falk J, Steven C, et al. Genetic and epigenetic Fine-Tuning of Tgfb1 expression within the human Osteoarthritic joint. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(10):1866–77. 10.1002/art.41736. Epub 2021/03/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shenshen W, Yin L, Han K, Jiang B, Meng Q, Aschner M, et al. Nat10 accelerates pulmonary fibrosis through N4-Acetylated Tgfb1-Initiated Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal transition upon ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ Pollut. 2023;322:121149. 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121149. Epub 2023/02/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao L, Lu F, Koc S, Zheng Z, Wang B, Zhang S, et al. Lrrk2 Gly2019ser mutation promotes Er stress via interacting with Thbs1/Tgf-Β1 in parkinson’s disease. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10(30):e2303711. 10.1002/advs.202303711. Epub 2023/09/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen YT, Jhao PY, Hung CT, Wu YF, Lin SJ, Chiang WC et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum Protein Txndc5 Promotes Renal Fibrosis by Enforcing Tgf-Β Signaling in Kidney Fibroblasts. J Clin Invest (2021) 131(5). Epub 2021/01/20. 10.1172/jci143645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Zhang PP, Wang PQ, Qiao CP, Zhang Q, Zhang JP, Chen F, et al. Differentiation therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting the activity of Akt/Gsk-3β/Β-Catenin Axis and Tgf-Β induced Emt with Sophocarpine. Cancer Lett. 2016;376(1):95–103. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.011. Epub 2016/03/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie T, Zheng Y, Zhang L, Zhao J, Wu H, Li Y. Pgrn knockdown alleviates pulmonary fibrosis regulating the Akt/Gsk3β signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;152:114443. 10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114443. Epub 2025/03/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsumoto T, Yokoi A, Hashimura M, Oguri Y, Akiya M, Saegusa M. Tgf-Β-Mediated Lefty/Akt/Gsk-3β/Snail Axis modulates Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition and Cancer stem cell properties in ovarian clear cell carcinomas. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57(8):957–67. 10.1002/mc.22816. Epub 2018/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang F, Sahu V, Peng K, Wang Y, Li T, Bala P, et al. Recurrent Rhogap gene fusion Cldn18-Arhgap26 promotes Rhoa activation and focal adhesion kinase and Yap-Tead signalling in diffuse gastric Cancer. Gut. 2024;73(8):1280–91. 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329686. Epub 2024/04/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tucci FA, Pennisi R, Rigiracciolo DC, Filippone MG, Bonfanti R, Romeo F, et al. Loss of numb drives aggressive bladder Cancer via a rhoa/rock/yap signaling Axis. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):10378. 10.1038/s41467-024-54246-6. Epub 2024/12/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang S, Liu Y, Sun Q, Zeng B, Liu C, Gong L, et al. Triple Cross-Linked dynamic responsive hydrogel loaded with selenium nanoparticles for modulating the inflammatory microenvironment via Pi3k/Akt/Nf-Κb and Mapk signaling pathways. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10(31):e2303167. 10.1002/advs.202303167. Epub 2023/09/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Jiang C, Ganther H, Lü J. Antimitogenic and proapoptotic activities of Methylseleninic acid in vascular endothelial cells and associated effects on Pi3k-Akt, erk, Jnk and P38 Mapk signaling. Cancer Res. 2001;61(19):7171–8. Epub 2001/10/05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu R, Zhu G, Sun Y, Li M, Hu Z, Cao P, et al. Neutrophil infiltration associated genes on the prognosis and tumor immune microenvironment of lung adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1304529. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1304529. Epub 2024/01/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Serrano-Gomez SJ, Maziveyi M, Alahari SK. Regulation of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition through Epigenetic and Post-Translational Modifications. Mol Cancer. 2016. 10.1186/s12943-016-0502-x. Epub 2016/02/26. 15:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.