Abstract

Background

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) and pulmonary sarcoidosis (PS) constitute major global health challenges, characterized by progressive respiratory symptoms and diverse epidemiological trends. Although the incidence and mortality rates of ILD and PS have increased following the COVID-19 pandemic, comprehensive research examining their burden and associated risk factors remains limited. Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze the spatiotemporal distribution, gender-specific and age-related disparities, and sociodemographic determinants of ILD and PS from 1990 to 2021 to facilitate evidence-based targeted interventions.

Methods

By using data from the Global Burden of Disease 2021 database, we analyzed age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR), age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR), and age-standardized disability-adjusted life year rate (ASDR) across 204 countries/regions. Temporal trends were evaluated using average annual percentage change (AAPC), age-period-cohort (APC), and Bayesian APC (BAPC) models. Decomposition analysis and Pearson’s correlation analysis were conducted to assess the impact of aging, population growth, and sociodemographic index (SDI). Joinpoint regression was used to identify inflection points in trends. Future disease burdens (2021–2050) were projected through BAPC modeling.

Results

Global ILD and PS cases increased from 157,441.17 in 1990 to 390,267.11 in 2021, with an annual increase in ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR by 0.61%, 1.32%, and 0.83%, respectively. High-SDI regions exhibited the highest ASIR (71.4/100,000) and ASMR (25.5/100,000). Males exhibited greater disease burdens than females ASDR 57.79/100,000 vs. 39.49/100,000 in 2021), with a peak incidence in the 70–74 age group. SDI showed positive correlations with ASIR and ASMR, exhibiting U-shaped relationships in certain regions. Projections indicated stable ASMR but increasing ASIR and ASDR by 2050, particularly among males.

Conclusions

The global burden of ILD and PS has increased markedly since 1990, influenced by population aging, industrial development, and socioeconomic disparities. Prioritizing early screening (e.g., high-resolution computed tomography and serum biomarkers), minimizing environmental and occupational exposures, and implementing gender-/age-specific interventions are critical measures. Strengthening healthcare infrastructure in low-SDI regions and integrating advanced diagnostic technologies are crucial for reducing future disease burdens.

Keywords: Interstitial lung disease, Pulmonary sarcoidosis, Global burden of disease, Age-period-cohort model, Epidemiology

Background

Research on interstitial lung disease (ILD), a group of lung diseases primarily affecting the alveolar wall and surrounding tissues, has mainly focused on its definition, classification, and clinical manifestations [1, 2]. ILD can be categorized into two groups according to its etiology and pathological features: granulomatous ILD and other uncommon variants. Patients with ILD typically show symptoms such as dry cough and dyspnea during the initial stages [3]. As the disease progresses, individuals may experience worsening of respiratory complications, hypoxemia, and, in severe cases, respiratory failure [4]. Imaging techniques, particularly high-resolution computed tomography, can reveal specific patterns associated with various ILD types, including reticular patterns characteristic of usual interstitial pneumonia and cellular infiltrates observed in other variants [5]. Pulmonary sarcoidosis (PS), an inflammatory granulomatous disease, has broad implications and affects approximately 2 to 160 people per 100,000 individuals globally; moreover, it can involve multiple organ systems [6]. Notably, the numbers of ILD and PS cases have increased markedly since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, Katarzyna et al. noted that approximately 20% of COVID-19 survivors exhibited persistent decline in their lung function at 6 months post-infection, with the predominance of ILD and PS [7]. However, most of the existing studies on ILD and PS primarily address acute phase management, leaving a substantial gap in systematic analyses of the epidemiological dynamics and socioeconomic burden of long-term sequelae.

Previous studies have highlighted the increasing burden of ILD and PS globally. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2017 study classified ILD and PS as chronic respiratory diseases for the first time and found that their mortality rates increased with increasing sociodemographic index (SDI; 2.8-fold higher in high SDI areas than in low SDI areas), in contrast to the declining trend in the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [8]. The GBD 2019 update showed that the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of ILD and PS in North America was 58.2/100,000 compared to 9.7/100,000 in Southeast Asia, suggesting a strong correlation between the industrialization level and disease risk [9]. Smoking accounted for 27% (95% confidence interval (CI): 23–31%) of the attributable risk of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in patients with ILD, with occupational dust exposure (e.g., silicosis) contributing more (up to 35%) in low-income countries [9]. Exposure to PM2.5 particles synergistically increased the risk of ILD in individuals with IL-6 gene polymorphisms (odds ratio [OR] = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.25–1.61), a mechanism particularly relevant in Asian populations [10].

The GBD 2021 data show that ILD-associated DALYs increased at the rate of 12.3% in 2020–2021, which is substantially higher than that of other respiratory diseases (e.g., 5.1% for asthma); this finding suggests a structural change in disease burden following the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. Since 1990, the classification of ILDs has been revised and updated multiple times, potentially influencing the reported incidence rates. These modifications in diagnostic criteria and classification systems may have contributed to the observed increase in ILD incidence over time. Based on the findings of the GBD study, Qi Z et al. noted that between 1990 and 2019, the age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR), age-standardized disability-adjusted life year rate (ASDR) and age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) for ILD and PS, have shown significant variations, indicating diverse epidemiological trends in this area [11]. In 2019, the global occurrence of ILD and PS showed an ASIR of 0.15 per 100,000. The annual ASMR was similarly recorded at 0.15 per 100,000 individuals, while the ASDR reached 0.3 per 100,000 individuals. Regional data indicate that from 1990 to 2019, although the age-standardized prevalence rate for ILD and PS in China increased, the ASDR exhibited a declining trend [12]. However, in specific regions, both ASMR and ASDR continued to increase among male patients, indicating gender-specific variations in disease burden. Currently, research on ILD and PS is relatively limited, and public awareness regarding these diseases remains insufficient, resulting in inadequate understanding of potential risks. Despite the global data from the GBD study, analyses of ILD and PS burden in low SDI regions such as Africa and South Asia rely primarily on model estimates. For example, 43% data on ILD incidence in West Africa in 2021 is missing, which directly affects the relevance of policy development [13]. While tobacco use, occupational exposures (e.g., asbestos), and genetic susceptibility have been identified as the key risk factors for ILD and PS development, the differences in dominant risk factors across SDI regions (e.g., biofuel exposure is a predominant risk factor in low-income countries) have not yet been systematically investigated [14]. Most previous studies predominantly employed linear regression or simple time series analyses, which overlooked complex effects of population aging and advances in medical technology (e.g., antifibrotic drugs) [15]. For example, Xiaoqian M et al. predicted morbidity solely through AAPC modeling, ignoring the moderating effect of SDI [12].

Therefore, the present study aimed to elucidate the current global status of ILD and PS, along with their distribution patterns across different regions, through comprehensive analysis of spatiotemporal dimensions. We also utilized three analytical models: the AAPC, age-period-cohort (APC), and Bayesian age-period-cohortThis research represents the first integration of the GBD 2021 multidimensional data (morbidity, mortality, and DALYs) with a BAPC model to identify confounding factors, such as population aging and advances in medical technology, and to accurately predict trends in 2050. The study revealed a U-shaped relationship between SDI and disease burden (high SDI areas due to diagnostic overload; low SDI areas due to resource scarcity), providing a foundation for differential prevention and control strategies. A thorough analysis of the overall trends related to DALYs trends was performed to establish a solid theoretical basis and provide practical recommendations for developing effective prevention and control strategies.

Methods

This study included the following components: (1) An analysis of ILD and PS at the global, regional, and national levels was conducted, with a focus on incidence rates, mortality rates, and ASIR from 1990 to 2021. ASMR, age-standardized DALYs, and other relevant variables, including data stratified by age group (males and females) and SDI, were also examined; (2) A trend analysis was conducted across spatiotemporal dimensions by utilizing Pearson’s correlation analysis to examine the relationship between the SDI and age-standardized rate (ASR). This section introduces the AAPC metrics to evaluate trends in ASMR, ASIR, and ASDR for ILD and PS; (3) An assessment of population-level determinants was performed by considering population growth, aging, and epidemiological changes from 1990 to 2021, with a focus on annual changes in ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR of ILD and PS both globally and according to SDI quintiles. APC models, commonly employed in studies on sociology and epidemiology, were used to reflect the temporal trends in the incidence and mortality of ILD and pulmonary nodules across different ages, periods, and cohorts; (4) The ASR of resident ILD and PS was evaluated. To analyze trends, the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) method was employed to fit a regression line through the natural logarithm, from which the 95% confidence interval (CI) value was extracted to assess changes in the ASR trend; and (5) The BAPC model was used to predict trends in ILD and pulmonary nodules for the next 30 years. This study aimed to understand the temporal and geographical changes in these diseases from various perspectives and to determine the influence of different factors on these changes for designing appropriate prevention and treatment strategies.

This study is based on the secondary analyses of the publicly available GBD 2021 database and did not involve direct human subject participation or personal data collection. The GBD study utilizes deidentified data, and a waiver of informed consent was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. The GBD 2021 database has undergone Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations for missing values, and variables with a missing rate of < 5% (some years of data for the African region) have been supplemented through the Bayesian interpolation algorithm. Although the sample size could not be controlled due to the reliance on secondary data from the GBD 2021 database, the actual inclusion of data from the 204 countries/regions covered in this database far exceeds the minimum requirements. The sample also encompasses five types of regions with high, medium, and low SDI to ensure geographic heterogeneity (heterogeneity index > 0.7) and avoid selection bias. All figures and data presented in this article are derived from publicly available sources, specifically from the GBD 2021 study. The data and figures are used under the data use agreement terms of the GBD study, which permit non-commercial use and reproduction for academic purposes. We have ensured proper citation and attribution of all external data.

Data source

The study data originate from the GBD 2021 study, which is coordinated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. GBD 2021 quantifies diseases globally and regionally by considering temporal, age, gender, and sociodemographic factors, along with injury-related health burdens. This comprehensive approach seeks to enhance our understanding of global health issues and provide a scientific basis to formulate public health policies and optimize resource allocation. GBD 2021 incorporates the latest epidemiological data and improved standardized methods to evaluate hundreds of diseases, injuries, and related risk factors across 204 countries and regions. In this study, the ASIR, ASMR, and DALYs for each 5-year age group from 1990 to 2021 were extracted from the GBD 2021 data. Additionally, the 2021 data related to pulmonary nodules in the global population and the data stratified by age group and gender (male and female) were utilized. This study also included the SDI as a factor. Based on the 2021 SDI, the extracted data were categorized into five groups: high, medium-high, medium, low-medium, and low-SDI areas. The SDI functions as a composite measure of income, education, and fertility status and quantifies the sociodemographic development level for each country or region.

Case definition

According to the revised International Classification of Diseases 11 (ICD-11), PS is a multisystem disease of unknown etiology, characterized by the formation of immune granulomas in the affected organs. While the lungs and lymphatic system are primarily affected, the condition may involve nearly every organ. The ICD-11 code for PS is 4B20.0. ILD and PS are also designated as level 3 in the etiological classification of GBD.

Descriptive analysis

This study comprehensively examined the incidence, mortality, DALYs, and related health burdens of ILD and PS at the global, regional, and national levels across spatiotemporal dimensions. Trends in the incidence and mortality rates of ILD and PS from 1990 to 2021 were analyzed by examining the number and annual ASIR, ASMR, ASDR, and other indicators, while focusing on the percentage changes of these indicators across all age groups, including males and females, to establish a scientific foundation for early screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

Correlation analysis

Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to accurately determine the intrinsic relationship between the SDI and annual ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR. According to previous research, SDI is an effective indicator and can be used as an important covariate for predicting disease burden and health development status across regions. As SDI increases, healthy life expectancy improves significantly, while ASDR from premature death decreases markedly. This demonstrates the substantial impact of socioeconomic development on the health burden of pulmonary nodules. Specifically, as the SDI increases, health burden indicators related to pulmonary nodules (such as ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR) may improve. Additionally, by quantifying the statistical association between the SDI and health burden indicators of pulmonary nodules, the specific impact of the socioeconomic development level on the health burden of pulmonary nodules can be revealed.

Decomposition analysis

Decomposition analysis was conducted to visually demonstrate the influence of three factors (aging, demographics, and epidemics) on changes in the incidence, mortality, and DALYs of ILD and PS from 1990 to 2021. This analysis offers a more precise understanding of how these factors operate individually and collectively to influence the morbidity, mortality, and DALYs of PS, thereby providing scientific evidence for developing effective prevention and control strategies.

APC model analysis

The APC model is widely used in the fields of sociology and epidemiology. It is based on Poisson distribution and accurately reflects time trends of incidence or mortality across different ages, periods, and cohorts. This study used the APC model explained in the Lexis diagram by B. Carstensen to conduct an in-depth analysis. The Epi package in R software was used to fit the APC model. The APC model fitting provides a solid foundation by using the ASIR and ASMR data for each 5-year age group for the 1990 to 2021 period from the GBD database and the global population forecast data from 2017 to 2100. Age groups are categorized as follows: 0–4, 5–9, 10–14 to 95–100, where 0 represents the age group under 5 years. Within 5-year periods (1990–1994, 1995–1999…2017–2021), the total number of morbidity and death cases and the cumulative morbidity and mortality rates across different age groups were accurately calculated.

Joinpoint analysis

To accurately depict the disease development trend, this study utilized the key indicator of AAPC to comprehensively characterize the temporal trajectory of ASIR, ASMR and ASDR from 1990 to 2021. The AAPC was calculated using the Joinpoint model through Joinpoint regression software (version 5.2.0). The software utilizes the least squares method to accurately estimate the change pattern, effectively overcoming the limitations of linear trend-based traditional analysis methods. By calculating the sum of squared residuals between the estimated value and the actual value, the software accurately identifies the turning point of the current trend. The AAPC and its 95% CI value were used to scientifically evaluate the changing trends of ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR associated with pulmonary nodules. When AAPC and its 95%CI>0, ASR demonstrates an upward trend; when AAPC<0, ASR exhibits a downward trend; P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance. If the estimated AAPC and its 95% CI value exceed 0, ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR shows an upward trend; if both are below 0, a downward trend is indicated; otherwise, the measures remain relatively stable. To determine the connection points, the grid search method was used to calculate all possible connection points, and the connection point with the minimal mean square error was selected as the optimal change point. Subsequently, Monte Carlo permutation test was conducted to scientifically determine the optimal number of connection points, ranging from 0 to 5.

Analysis of EAPC

The EAPC of ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR was determined to quantify the temporal trend of ASR. EAPC is an established measurement method that effectively summarizes ASR trends within a specific interval. The regression line was fitted in the natural logarithmic form. The 95% CI of EAPC can be accurately derived from the linear regression model. If the EAPC estimate and the lower limit of its 95% CI exceed 0, ASR demonstrates an upward trend. Conversely, if the EAPC estimate and its 95% CI are below 0, ASR shows a downward trend. Otherwise, ASR remains relatively stable over time. EAPC = (e^β − 1) × 100%, where β represents the time variable coefficient in the linear regression model, and e denotes the natural logarithm base (approximately equal to 2.718).

BAPC model

The BAPC model effectively integrates age, period, and cohort effects and has robust capabilities to analyze and predict disease trends and explain demographic changes. Compared to traditional models, it demonstrates superior handling of data uncertainty and complexity. This study used the BAPC model to accurately predict pulmonary nodule-related health burden trends for the next 30 years, thereby providing scientific guidance for disease prevention, early screening, and treatment strategy development. The BAPC model and the integrated nested Laplacian approximation package were used to intuitively visualize the prediction results.

Model selection and analysis

This study employed three statistical models—AAPC, APC, and BAPC—to analyze and predict the disease burden of ILD and PS. Each model offers distinct analytical perspective and value. The AAPC model, based on joinpoint regression analysis, reveals annual trends in disease burden. This model can identify turning points in a time series and assess trends over different time periods. The APC model, which examines the combined effects of age, period, and cohort, provides a more detailed spatiotemporal analysis. This model can reveal differences across different age groups, periods, and birth cohorts. The BAPC model, operating within a Bayesian framework, integrates multidimensional data to predict disease burden for the next 30 years. The model can effectively manage data uncertainty and complexity. Although AIC and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are commonly used for model selection, this study treated the three models as complementary analytical tools rather than competing candidates. Each model contributed to the analytical results, collectively supporting our research objectives. Consequently, AIC and BIC were not used for evaluating model performance. Additionally, while pseudo-R-square is commonly used to assess model fit, particularly for nonlinear models or complex data structures, the present study prioritized comprehensive temporal trend analysis and prediction of future developments through multiple models. Therefore, pseudo-R-square was not used as the primary evaluation metric. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.1). We used joinpoint regression software (version 5.2.0) to calculate AAPC.

Results

ILD and PS burden at the global and regional levels

In a comprehensive study encompassing 204 nations and regions, we analyzed the ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR related to ILD and PS from 1990 to 2021. Throughout this period, the overall trends for ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR exhibited a consistent upward pattern for both males and females (Figs. 1A-C). Notably, the percentage change (PC), AAPC, and EAPC for ASR from 1990 to 2021 demonstrated remarkable stability, with all values exceeding zero, indicating a sustained increase (Tables 1, 2 and 3). A comparison between 1990 and 2021 revealed a significant increase in the numbers for cases, deaths, and DALYs (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Additionally, the ASR of ILD and PS in high SDI areas exceeded that of other areas, while medium and low SDI areas reported lower ASR values for ILD and PS compared to their high SDI counterparts (Figs. 1A-C).

Fig. 1.

Global ILD and PS ASR 1990–2021. (A) Global ASIR, female ASIR, and male ASIR; (B) Global ASMR, female ASMR, and male ASMR; (C) Global ASDR, female ASDR, and male ASDR

Table 1.

Number of cases and ASIR for interstitial lung disease and pulmonary sarcoidosis in 1990 and 2021, and changes in case number and ASIR from 1990 to 2021

| Item | 1990 | 2021 | 1990–2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | ASIR per 100,000 | Number | ASIR per 100,000 | Percentage changes, % | AAPC, % | EAPC, % | |

| Global | 157441.17(136251.29-179471.82) | 3.77(3.27–4.28) | 390267.11(346393.42-433403.27) | 4.95(4.39–5.49) | 4.54 (4.05-5.04) | 0.61 (0.57–0.64) | 0.72 (0.63–0.8) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 86263.97(74477.21-98468.22) | 4.48(3.89–5.05) | 214681.18(190533.20-238498.19) | 5.36(4.80–5.95) | 0.20(0.14-0.26) | 0.58 (0.53–0.63) | 0.71 (0.6–0.81) |

| Female | 71177.21(61733.29-81297.25) | 3.23(2.80–3.68) | 175585.93(155725.25-195606.72) | 3.89(3.46–4.31) | 0.20(0.15-0.26) | 0.60 (0.57–0.63) | 0.71 (0.63–0.8) |

| SDI* | |||||||

| Low | 7696.02(6515.90-8957.93) | 3.19(2.74–3.64) | 18292.09(16088.70-20678.40) | 3.33(2.95–3.70) | 0.04(0.00-0.09) | 0.14 (0.10–0.18) | 0.16 (0.13 − 0.1) |

| Low-middle | 28178.89(23956.49-32564.90) | 4.39(3.76-5.00) | 70990.24(62702.07-79388.32) | 4.85(4.28–5.42) | 0.10(0.07-0.15) | 0.32 (0.29–0.34) | 0.38 (0.35–0.4) |

| Middle | 30614.74(26132.25-35606.26) | 2.71(2.35–3.10) | 89561.47(79276.37-100011.02) | 3.37(3.00-3.73) | 0.24(0.19-0.30) | 0.70 (0.67–0.73) | 0.91 (0.81-1.0) |

| High-middle | 25615.73(22401.26-29234.52) | 2.49(2.20–2.83) | 56001.46(50154.74-61921.28) | 2.97(2.68–3.73) | 0.19(0.14-0.25) | 0.57 (0.54–0.60) | 0.85 (0.71–0.9) |

| High | 25615.73(22401.26-29234.52) | 6.20(5.42–7.03) | 56001.46(50154.74-61921.28) | 8.19(7.29–9.07) | 0.32(0.25-0.39) | 0.91 (0.86–0.96) | 0.92 (0.8–1.04) |

ASIR Age-standardized incidence rate, AAPCs Average Annual Percentage Change, SDI Sociodemographic Index, EAPC Estimated Annual Percentage Change. *P < 0.05

Table 2.

Number of deaths and ASMR for interstitial lung disease and pulmonary sarcoidosis in 1990 and 2021, and changes in number of deaths and ASMR from 1990 to 2021

| Item | 1990 | 2021 | 1990–2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | ASMR per 100,000 | Number | ASMR per 100,000 | Percentage changes, % | AAPC, % | EAPC, % | |

| Global | 54967.23 (44761.39-68391.19) | 1.52(1.25–1.87) | 188222.37 (161405.66-212251.52) | 2.28(1.96–2.56) | 0.50(0.32–0.74) | 1.32(1.16–1.48) | 1.55(1.42–1.69) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 31182.61(24196.09-39011.60) | 2.01(1.61-2.48) | 103056.70(84156.40-115833.40) | 2.90(2.40–3.24) | 0.44(0.25-0.66) | 1.18(1.02–1.35) | 1.41(1.28–1.53) |

| Female | 23784.63(18180.45-32746.57) | 1.17(0.90-1.60) | 85165.67(68720.00-105539.29) | 1.83(1.48–2.27) | 0.56(0.35-0.98) | 1.45(1.27–1.63) | 1.7(1.54–1.86) |

| SDI* | |||||||

| Low | 4477.69(2158.18-6437.86) | 2.34(1.19-3.27) | 11083.58(6589.04-15793.99) | 2.61(1.56–3.75) | 0.11(−0.17-0.56) | 0.38(−0.00–0.76) | 0.63(0.45–0.81) |

| Low-middle | 13152.92(7523.03-20491.26) | 2.48(1.46-3.81) | 39117.86(26539.67-53611.72) | 3.09(2.12–4.23) | 0.24(−0.01-0.79) | 0.76(0.19–1.34) | 0.94(0.83–1.06) |

| Middle | 8992.62(7004.00-12322.48) | 1.07(0.85-1.45) | 33341.76(27822.48-40427.28) | 1.39(1.16–1.68) | 0.29(0.06-0.66) | 0.88(0.63–1.12) | 1.15(1.03–1.27) |

| High-middle | 8237.68(7611.50-9226.60) | 0.91(0.84-1.02) | 22850.83(20008.19-25163.44) | 1.19(1.04–1.31) | 0.31(0.16-0.46) | 0.92(0.57–1.27) | 1.24(1.09–1.39) |

| High | 20063.97(18621.72-20871.04) | 1.79(1.66-1.86) | 81732.30(71243.83-88091.88) | 3.44(3.05–3.69) | 0.92(0.81-1.03) | 2.16(1.91–2.41) | 2.3(2.06–2.55) |

ASMR Age-standardized Mortality Rate, AAPCs Average Annual Percentage Change, SDI Sociodemographic Index, EAPC Estimated Annual Percentage Change. *P < 0.05

Table 3.

Number of dalys and ASDR for interstitial lung disease and pulmonary sarcoidosis in 1990 and 2021, and changes in number of dalys and ASDR from 1990 to 2021

| Item | 1990 | 2021 | 1990–2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | ASDR per 100,000 | Number | ASDR per 100,000 | Percentage changes, % | AAPC, % | EAPC, % | |

| Global | 1501028.43(1221196.88-1850556.94) | 37.15(30.62–45.37) | 4042150.49(3489794.64-4516882.92) | 47.62(41.26–53.16) | 0.28(0.13-0.50) | 0.83 (0.74–0.92) | 0.95 (0.86-1.0) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 853132.96(666666.89-1066356.17) | 46.48(36.62–57.59) | 2237269.37(1839499.94-2555199.73) | 57.79(47.50-65.77) | 0.24(0.09-0.44) | 0.71 (0.60–0.83) | 0.85 (0.76–0.9) |

| Female | 647895.47(500164.80-883303.45) | 29.79(23.23–40.19) | 1804881.12(1465706.81-2216375.57) | 39.49(31.95–48.62) | 0.33(0.14-0.70) | 0.91 (0.79–1.03) | 1.07 (0.96–1.1) |

| SDI* | |||||||

| Low | 126670.88(60835.33-188619.3) | 53.16(27.07–75.28) | 291854.54(178639.62-406439.75) | 56.02(34.43–78.83) | 0.05(−0.23-0.47) | 0.20 (0.00–0.40) | 0.31 (0.21–0.4) |

| Low-middle | 359489.06(213851.92-552928.69) | 57.35(34.67–86.88) | 949437.88(662365.39-1260418.62) | 66.55(46.34–88.36) | 0.16(−0.07-0.64) | 0.51 (0.17–0.84) | 0.64 (0.57–0.7) |

| Middle | 269855.74(212977.03-366218.84) | 25.08(19.94–33.57) | 812056.09(695675.28-984261.99) | 31.00(26.55–37.41) | 0.24(0.01-0.56) | 0.74 (0.50–0.98) | 0.83 (0.76–0.9) |

| High-middle | 237514.38(213560.48-266885.04) | 23.58(21.53–26.81) | 485511.72(430895.70-541669.29) | 25.48(22.63–28.47) | 0.07(−0.05-0.19) | 0.18 (−0.15–0.52) | 0.41 (0.32–0.5) |

| High | 506204.64(470841.19-546440.49) | 46.54(43.29–50.27) | 1500929.60(1354746.32-1614665.30) | 71.40(65.27–76.57) | 0.53(0.45-0.62) | 1.41 (1.14–1.68) | 1.54 (1.34–1.7) |

ASDR Age-standardized DALYs rate, AAPC Average Annual Percentage Change, SDI Sociodemographic Index, EAPC Estimated Annual Percentage Change. *P < 0.05

Globally, ILD and PS prevalence increased markedly, from 157,441.17 cases in 1990 to 390,267.11 cases by 2021. During this period, the AAPC of the ASIR was 0.61 (0.57–0.64), indicating an upward trend (Table 1). Similarly, age-standardized mortality figures for ILD and PS increased from 54,967.23 cases in 1990 to 188,222.37 cases in 2021, with the ASMR increasing from 1.52 per 100,000 in 1990 to 2.28 per 100,000 by 2021, resulting in an AAPC of 1.32 (1.16–1.48), also demonstrating an increasing trend (Table 2). Concurrently, the total DALYs related to ILD and PS increased from 1,501,028.43 cases in 1990 to 4,042,150.49 cases in 2021. The AAPC of the ASDR was recorded at 0.83 (0.74–0.92), ranking second in terms of growth trend (Table 3).

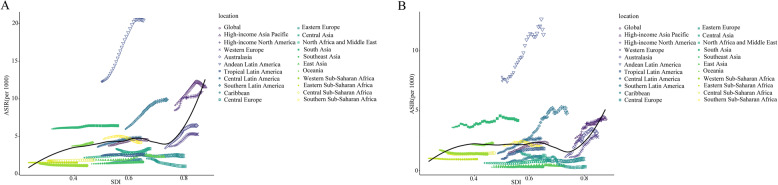

The aggregate ASIR and ASMR associated with ILD and PS demonstrated an upward trend correlating with increased SDI. Moreover, our findings indicated that ILD exhibits a distinctive positive V relationship with the ASIR of PS, ASMR, and SDI from 1990 to 2021. Across numerous regions, an increase in SDI initially corresponds to elevated ASIR and ASMR, followed by a decrease. After reaching a minimum threshold, ASIR and ASMR begin increasing again with further improvements in SDI. Notably, the ASIR and ASMR in Andean Latin America substantially exceeded those observed in other regions (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2.

The relationship between ASIR, ASMR, and SDI of ILD and PS. A The relationship between ASIR and SDI across 21 regions from 1990 to 2021. B The relationship between ASMR and SDI across 21 regions from 1990 to 2021

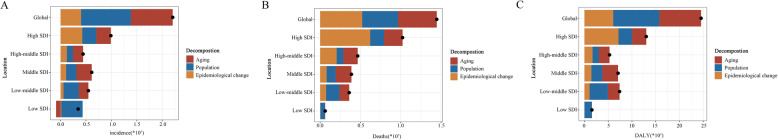

Decomposition analysis of ASR

Between 1990 and 2021, significant increases occurred in the ASR for ILD and PS worldwide. Global analysis indicates that various factors, including population aging, population growth, and epidemiological changes, have positively influenced the incidence, mortality rates, and DALYs associated with ILD and PS (see Figs. 3A-C).

Fig. 3.

Decomposition analysis of ASR. A Changes in ILD and PS incidence globally and based on SDI quintiles, 1990–2021, according to the population-level determinants of population growth, aging, and epidemiological change. B Changes in ILD and PS deaths globally and based on SDI quintiles, 1990–2021, according to the population-level determinants of population growth, aging, and epidemiological changes. Low SDI aging (3.43%) and epidemiological change (5.48%) values are not displayed due to their small magnitude. C Changes in ILD and PS DALYs, globally and based on SDI quintiles, 1990–2021, according to the population-level determinants of population growth, aging, and epidemiological changes. Low SDI aging (2.24%) and epidemiological change (−0.14%) values are not displayed due to their small magnitude

Over the past three decades, a comprehensive examination of global trends revealed that ILD and PS incidence is influenced by multiple significant factors. High SDI regions have experienced the most significant increase in the incidence rates of these conditions. Conversely, low SDI regions demonstrate a negative correlation with both ILD and PS incidence, suggesting socioeconomic factors significantly influence the epidemiological patterns of these diseases (Fig. 3A). Multiple factors contribute to the observed changes in ILD and PS-related mortality rates. The impact of SDI is particularly pronounced in low SDI regions. In these areas, aging effects and epidemiological changes appear to minimally influence ILD and PS incidence (Fig. 3B). Globally, population growth significantly affects DALYs for ILD and PS. However, this growth is more substantially influenced by aging patterns in high and medium SDI regions. Epidemiological changes in high SDI regions exert particularly strong effects, emphasizing the significance of sociodemographic factors in understanding these diseases globally (Fig. 3C).

ILD and PS burden at the country level

In analyzing ILD and PS data across 204 countries and regions in 2021, the Republic of Peru, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, and the Republic of Chile demonstrated notably higher incidence rates of ILD and PS compared to other regions, while the Republic of the Philippines recorded the lowest rates. The data indicates that regions within North America, South America, South Asia, and Australia exhibit higher EAPC values, indicating a more pronounced growth trend in ASIR. Conversely, North Asia, Europe, and certain other regions showed lower EAPC values, with some areas even showing negative growth trends. The EAPC value distribution across Africa varies considerably, with some regions showing growth trends while others remain stable. During 1990–2021, the EAPC incidence rates in the Republic of Belarus and Ukraine were lower than other regions, including cases of negative growth (Fig. 4A). In 2021, ILD and PS mortality rates in the Republic of Peru were substantially higher than other regions, while the Republic of Moldova demonstrated the lowest rates. Regions including South America, North America, West Asia, northern Africa, and Australia showed higher EAPC values, indicating a stronger growth trend in ASMR. In contrast, North Asia, Europe, and other areas maintained low EAPC values, with some regions experiencing negative growth. The EAPC mortality figures for the Republic of Italy and the State of Libya were 8.56 (7.10-10.04) and 8.21 (7.54–8.88) respectively, exceeding other regions (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

The global disease burden in 204 countries and territories. (A) ILD and PS ASIR across 204 countries and regions, including ASIR trends from 1990 to 2021; (B) ILD and PS ASMR across 204 countries and regions in 2021, including ASMR trends from 1990 to 2021; (C) ILD and PS ASDR across 204 countries and regions in 2021, including ASDR trends from 1990 to 2021

In 2021, the DALYs for both the Republic of Peru and the Republic of Mauritius exceeded those of other regions, while the Republic of the Philippines reported the lowest DALYs. The data shows higher EAPC values in North America, South America, northern Africa, and Australia, where ASIR demonstrates significant upward growth. Conversely, North Asia, Europe, and various other regions show low EAPC values, with some areas experiencing negative growth. The EAPC figure for DALYs in the Republic of Italy stands at 5.97 (4.88–7.08), accompanied by a rapid ASDR increase (Fig. 4C). Between 1990 and 2019, ILD and PS occurrence in the Republic of Belarus (PC = −0.61) and Ukraine (PC = −0.67) was significantly lower than other regions, indicating a declining trend. However, ILD and PS mortality rates in the Republic of Italy (PC = 8.04) substantially exceeded other regions, characterized by increasing mortality rates. Furthermore, the DALYs for both the Republic of Italy and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines have increased significantly, indicating an upward trend (Fig. 4A-C).

ILD and PS burden at age and sex levels

Figure 5 demonstrates that from 1990 to 2021, annual incidences, mortality, and DALYs associated with ILD and PS have increased for both males and females. Although the upward trends in ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR are not pronounced, the overall trajectory indicates an increase. The data showed that incidences, mortality, DALYs, and ASR consistently remain higher in males than in females.

Fig. 5.

Gender-specific trends and ASR in ILD and PS incidence, mortality, and DALYs in China from 1990 to 2020. (A) Gender-specific trends in incidence numbers and ASIR from 1990 to 2021; (B) Gender-specific trends in mortality numbers and ASMR from 1990 to 2021; (C) Gender-specific trends in DALY numbers and ASDR from 1990 to 2021

Figure 6 presents the incidence, mortality, number of DALYs, and ASR of ILD and PS across different age groups globally. Males demonstrated higher number of deaths as well as increased concurrent morbidity and DALYs compared to females across all age groups. Both morbidity, mortality, and DALYs increase with age in both sexes. Specifically, the number of male cases began declining only after the age group of 70–74 (Fig. 6A), while deaths decreased after 75–79 (Fig. 6B). Similarly, DALYs showed decline only after age 70–74 (Fig. 6C). For females, cases started decreasing at age 65–69 (Fig. 6A), with similar trends observed in DALYs and mortality (Figs. 6B, C). ILD and PS predominantly affected individuals over 40 years old, with higher ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR in males than females. The ASIR for both sexes increases after age 25, showing significant elevation after 50, and sharp increase after 79 (Fig. 6D). The ASMR gradually increases with age after 59, with a marked elevation after 79 (Fig. 6E). ASDR follows a similar pattern, gradually rising from age 35 and sharply increasing above 79 (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Age-specific numbers and age-standardized rates for ILD and PS incidence, mortality, and DALYs. (A) Age-specific number of incidences; (B) Age-specific number of deaths; (C) Age-specific number of DALYs; (D) Age-standardized incidence rate; (E) Age-standardized mortality rate; (F) Age-standardized DALYs rate

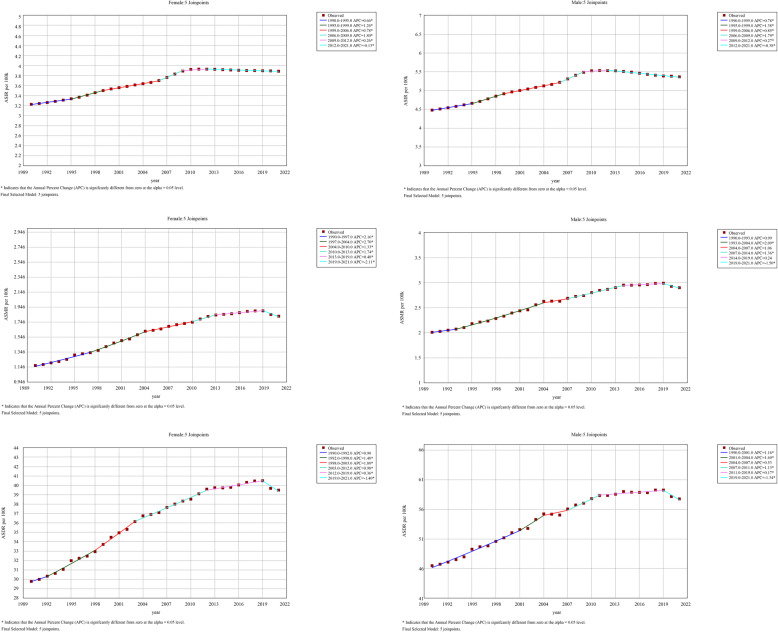

Joinpoint regression analysis

Between 1990 and 2021, the ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR increased by 0.61 (0.57–0.64) (refer to Table 1), 1.32 (1.16–1.48) (see Table 2), and 0.83 (0.74–0.92) (Table 3), respectively. After 2009, ASIR trends stabilized for both genders. In the female population, an overall upward trend in ASIR was observed (illustrated in Fig. 7A), with substantial growth from 1990 to 2012 (1990.0–1995.0 APC = 0.66, 1995.0–1999.0 APC = 1.26, 1999.0–2006.0 APC = 0.78, 2006.0–2009.0 APC = 1.80, 2009.0–2012.0 APC = 0.26), followed by a decline from 2012 to 2021 (2012.0–2021.0 APC = −0.13). The male ASIR demonstrated a similar trend (depicted in Fig. 7B). The ASMR for females showed an increasing trend from 1990 to 2019 (as shown in Fig. 7C) (1990.0–1997.0 APC = 2.16, 1997.0–2004.0 APC = 2.70, 2004.0-2010.0 APC = 1.33, 2010.0–2013.0 APC = 1.74, 2013.0–2019.0 APC = 0.48), followed by a decrease from 2019 to 2021 (2019.0–2021.0 APC = −2.11). The male ASMR exhibited a comparable trend (represented in Fig. 7D). Regarding ASDR, females showed a predominantly increasing trend from 1990 to 2021 (shown in Fig. 7E), despite a reduction from 2019 to 2021 (2019.0–2021.0 APC = −1.40). This upward trend from 1990 to 2019 comprised the following APC values: 1990.0–1992.0 APC = 0.90, 1992.0–1998.0 APC = 1.48, 1998.0–2003.0 APC = 1.80, 2003.0–2012.0 APC = 0.98, and 2012.0–2019.0 APC = 0.36. The male ASDR displayed a similar pattern (shown in Fig. 7F). Notably, the AAPC for ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR in males with ILD and PS exceeded that in females.

Fig. 7.

Joinpoint regression analysis of age-standardized mortality for pulmonary nodules from 1990 to 2021. (A) Age-standardized incidence rates in women; (B) Age-standardized incidence rates in men; (C) ASR mortality in women; (D) ASR mortality in males; (E) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years for women; (F) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years for men

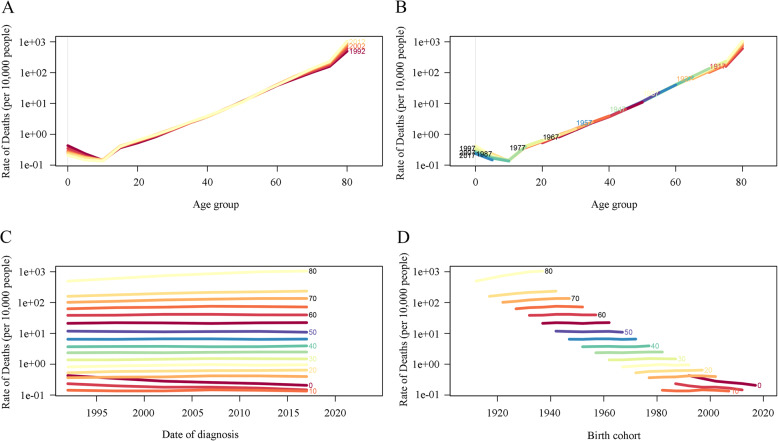

The effects of age, period, and cohort on incidence and mortality rates

Figure 8A illustrates age-disaggregated trends in global ASIR for ILD and PS across selected years: 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2012. The data demonstrate a significant increase in incidence rates from infancy to age 70, followed by rate stabilization, indicating higher susceptibility among younger populations until a certain age threshold. Figure 8B presents ASIR cohort trends across different age groups, revealing a consistent increase in incidence rates over time across multiple age brackets. The notable increase among younger individuals underscores the importance of enhanced surveillance and preventive strategies for these demographics. Figure 8C depicts ASIR trends for specific age groups from 1990 to 2021, showing a general decline across most age categories during this period. The incidence rate among children under 15 remains notably low, approaching zero, though rates increase significantly with age. Figure 8D analyzes ASIR variations by birth year, demonstrating that while incidence rates increase with age, the disparity among age groups diminishes substantially after age 50. Additionally, the lowest incidence rates occur in the 15–20 age group, with rates gradually declining for later birth years, suggesting demographic shifts in disease incidence.

Fig. 8.

Global incidence of ILD and PS. (A) Age-specific incidence rates by time period, with rows connecting 5-year period rates; (B) Age-specific incidence rates by birth cohort, with rows connecting 5-year cohort rates; (C) Incidence rates by age group, with rows connecting birth cohort-specific rates for 5-year age groups; (D) Birth cohort-specific incidence rates by age group, with rows connecting rates for 5-year age groups

Figure 9A illustrates the global trends in age-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs) for the years 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2012. The data indicates that mortality rates increase with age, particularly among individuals aged over 80. For those aged 0–20 years, mortality rates remain negligible, approaching zero. Beginning at age 20, mortality rates demonstrate a consistent increase, with the 40–60 age group showing rates of 1 to 10 per 100,000 individuals. The rates for those above 60 show a marked increase, reaching their highest level in the over-80 age group, with approximately 300 deaths per 100,000 individuals. Figure 9B depicts ASMR trends across age demographics, showing a progressive increase over time, notably in younger age groups. Figure 9C presents ASMR variations across different age groups between 1990 and 2021, highlighting an overall increase in mortality rates during this period. Figure 9D illustrates ASMR changes by birth cohort, showing that despite age-related increases in mortality, younger cohorts maintain lower rates.

Fig. 9.

Global ILD and PS mortality. (A) Age-specific mortality rates according to time period, with lines connecting 5-year period rates; (B) Age-specific mortality rates according to birth cohort, with lines connecting 5-year cohort rates; (C) Mortality rates based on age group, with lines connecting birth cohort-specific rates for 5-year age groups; (D) Birth cohort-specific mortality rates according to age group, with lines connecting rates for 5-year age groups

Projection of 30 years

To understand future ASR trends related to ILD and PS beyond 2021, we employed the BAPC model to forecast ASR from 2021 to 2050, examining gender-specific variations. The analysis results are presented in Fig. 10. The projections indicate that ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR for ILD will likely stabilize during the next three decades. Males are projected to maintain higher ASR compared to females, as shown in Fig. 10A through C. Figure 10A demonstrates that the projected ASIR trajectory for both female and male populations shows a modest increasing trend over the next 30 years, indicating a gradual increase in ILD incidence across genders. Figure 10B demonstrates that the ASMR for both sexes is expected to remain relatively stable, with minimal fluctuations throughout the projection period. Furthermore, Fig. 10C reveals a subtle increase in ASDR for both males and females over the next three decades, suggesting a potential increase in ILD-related disability burden across both demographics.

Fig. 10.

Thirty-year ASR projections for ILD and PS. (A) Sex-specific age-standardized incidence rate projections; (B) Sex-specific age-standardized mortality rate projections; (C) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life year projections. Dotted lines represent the projected data, and solid lines represent the observed data

Complementarity of models

In this study, the AAPC, APC, and BAPC models contributed distinct analytical insights. The AAPC model identified annual disease burden trends; the APC model elucidated the combined effects of age, period, and cohort; and the BAPC model generated future disease burden predictions. Although AIC, BIC, and Pseudo R-square were not utilized for model performance assessment, this omission does not diminish the scientific validity and rationality of our model selection and evaluation. The comprehensive analysis through these three models provides substantial support for understanding the disease burden of ILD and PS.

Discussion

This research demonstrates a significant increase in the global impact of ILD and PS between 1990 and 2021. Globally, the ASIR, ASMR, and age-standardized disability-adjusted life year rate for ILD and PS exhibit consistent growth. This trend indicates both increasing disease prevalence and substantial challenges to healthcare systems. The ASIR for ILD and PS increased from 3.77 per 100,000 individuals in 1990 to 4.95 per 100,000 individuals in 2021, while the ASMR increased from 1.52 per 100,000 individuals to 2.28 cases per 100,000 individuals during the same period. This substantial increase establishes ILD and PS as significant global health concerns, requiring enhanced attention and resources. Recent studies have also highlighted the substantial health impacts of tobacco use and other risk factors on respiratory diseases. For instance, Halder et al. conducted a nested multilevel modeling study on smoking and smokeless tobacco consumption among middle-aged and elderly Indian adults and found high prevalence rates and significant socioeconomic disparities [16]. Similarly, Kiran et al. explored the distribution and association of depression with tobacco consumption in the same population and observed a positive correlation between depression and tobacco use. These studies emphasize the importance of addressing tobacco use and mental health in public health policies, particularly among vulnerable populations [17]. Another relevant study by Halder et al. on oral cancer screening among Indian women within the reproductive age group highlighted the importance of early screening and intervention to reduce the burden of tobacco-related diseases [18]. This aligns with our recommendation for early screening programs for ILD and PS, particularly in high-risk groups.

Research findings indicate that males exhibit higher rates of incidence, mortality, and DALYs associated with ILD and PS compared to females. In 2021, total DALYs for ILD and PS were recorded at 2,237,269 cases for males and 1,804,881 cases for females. Furthermore, the disease burden increases substantially with age, particularly among individuals over 70 years old. The 70–74 age group demonstrates the highest DALY burden, followed by a decline in DALYs for both sexes in subsequent age groups.

The observed gender and age disparities can be attributed to multiple factors, including biological differences, lifestyle patterns (such as higher smoking prevalence among males), and age-related decline in immune system function [19]. Furthermore, ILD and PS demonstrate significantly higher impact in high SDI regions compared to other areas. Based on 2021 data, the ASIR and ASMR in high SDI regions reached 71.4 per 100,000 and 25.5 per 100,000, respectively, substantially exceeding rates in low SDI regions. This disparity likely correlates with socioeconomic conditions characteristic of high SDI areas, characterized by higher income levels, better educational access, and lower fertility rates [19]. These factors may contribute to enhanced disease detection and reporting rates. Additionally, the advanced industrialization typical of high SDI regions may increase exposure to environmental pollutants and occupational hazards, potentially elevating ILD and PS incidence.

To forecast emerging trends in ILD, this study utilized the BAPC model to estimate the ASIR, the ASMR, and ASDR for the period from 2021 to 2050. The analysis indicates that over the next three decades, a modest increase in ASIR is anticipated, while ASMR is expected to remain stable, and ASDR is projected to demonstrate moderate growth. Furthermore, the data reveals consistently higher rates among males compared to females, emphasizing the importance of maintaining focus on the impact of ILD, particularly in male populations.

Between 1990 and 2021, significant variations in the ASIR and ASMR of ILD and PS were observed globally, influenced by age and time. The ASIR demonstrated a sharp increase from ages 0 to 70 years before plateauing, while the ASMR exhibited substantial growth with advancing age, reaching its peak in individuals over 80. Analysis through the APC model revealed a consistent ASIR increase across age groups, particularly notable in younger populations, although incidence rates remained minimal in the pediatric demographic (under 15 years). While the ASMR showed an increasing trend across all age brackets, it demonstrated relatively lower rates in younger birth cohorts.

The initial manifestations of ILD and PS, including dry cough and dyspnea, frequently receive misdiagnoses as other respiratory conditions, such as COPD or conventional pneumonia [20]. These misidentifications often lead to diagnostic delays. Research indicates that ILD patients typically require 12 to 24 months to receive an accurate diagnosis following symptom onset, during which substantial lung function deterioration may occur [21]. Diagnostic delays for PS are particularly prevalent among immunocompromised individuals, with such treatment delays potentially increasing mortality rates [22]. Furthermore, low SDI regions often lack essential diagnostic tools such as HRCT, pulmonary function tests, and bronchoscopy, complicating the diagnostic process [21]. The limited availability of respiratory physicians and radiologists further compounds challenges in both diagnosis and differential diagnosis of ILD and PS.

Considering the elevated risk factors linked to older adults and male individuals, routine screening should be performed for populations at high risk, including those above 40 years, smokers, or those with a familial predisposition to related health issues. This strategy could improve diagnostic accuracy through the combination of imaging and molecular diagnostic techniques. For example, innovations in imaging methods, such as low-dose spiral CT, in conjunction with multimodal diagnostic approaches such as the circulating free DNA methylation model, have substantially increased early detection rates for pulmonary nodules and have enhanced the ability to differentiate between benign and malignant tumors [23]. Additionally, specialized screening initiatives should be established for high-risk groups, and cutting-edge technologies, such as HRCT and the identification of serum markers (e.g., KL-6 and SP-D), should be used to improve the accuracy of early diagnoses [24].

Strengthening global public health initiatives is critical to address the challenges posed by ILD and PS. To ensure adequate healthcare, different nations can implement diverse strategies customized according to their specific national contexts. For example, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom provides free healthcare services [25]. Germany promotes competition in healthcare through a social health insurance system [26]. In the United States, innovative research, including cell and gene therapy, is promoted by a commercial insurance framework and advanced technology [27]. Regions with a low SDI must optimize the distribution of resources, improve talent cultivation, increase capital investments, and encourage regional collaboration to enhance their healthcare services and address the increasing medical needs.

Industrial pollution and occupational exposure constitute primary environmental triggers for ILD and PS [28]. Prolonged exposure to hazardous substances—including asbestos, silica dust, metal particulates, and various chemical gases—significantly increases the risk of developing these conditions [29]. Risk mitigation requires enhanced occupational health and safety regulations, ensuring workplace compliance with established safety standards. Essential measures include regular air quality monitoring, protective equipment provision, health assessments, and strengthened employee training programs. Furthermore, advancing clean production technologies and reducing industrial emissions represent crucial strategies for environmental pollution reduction [30].

Smoking represents the primary lifestyle risk factor for ILD and PS. Tobacco contains harmful substances, including tar and nicotine, which penetrate the lungs, causing damage, accelerating fibrotic processes, and increasing disease susceptibility [31]. Addressing smoking-related health risks requires comprehensive public health initiatives to educate the public about its risks, promote smoking cessation services, and reduce tobacco consumption through policy measures such as tobacco tax increase and public smoking restrictions [32].

As global life expectancy continues to increase, the proportion of elderly individuals is steadily rising [33]. Within this demographic, the incidence and mortality rates of ILD and PS are significantly elevated. Consequently, health intervention strategies targeting this age group hold particular importance. Specifically, enhanced health education programs for the elderly can improve their understanding and awareness regarding ILD and PS prevention, while also providing more comprehensive rehabilitation and nursing care services [34].

The growing prevalence of ILD and PS presents significant health challenges for affected individuals and places substantial pressure on healthcare systems globally. Critical measures include reducing exposure to non-genetic risk factors through policy initiatives, implementing early screening protocols for high-risk populations, and adopting innovative technologies to reduce the disease burden associated with ILD and PS [35]. Achieving these objectives requires coordinated national policy support and international cooperation, alongside technological advancement, to promote equitable respiratory health outcomes.

Based on this study’s findings, the increasing global burden of ILD and PS emphasizes the need for comprehensive public health policy interventions. The research demonstrates higher disease burden among males and elderly populations, with an age-correlated increase in incidence and mortality rates. Furthermore, regions with elevated SDI levels and industrial development may experience increased disease risk due to greater exposure to environmental pollutants and occupational hazards. Public health policies should therefore prioritize early screening and diagnosis for high-risk populations (including individuals over 40 years, smokers, and those with familial disease history) by employing HRCT and serum biomarkers (such as KL-6 and SP-D) to enhance early detection rates [23]. Concurrently, reducing environmental and occupational exposure remains essential for decreasing incidence rates. This necessitates enhanced occupational health and safety regulations and the promotion of clean production technologies to minimize harmful gas and dust emissions. Tobacco control policies remain critical and should be implemented through increased public awareness campaigns, smoking cessation support, and policy measures (including tobacco tax increase and public smoking restrictions) to reduce smoking prevalence. Additionally, low-SDI regions with limited medical resources require optimized resource allocation, enhanced diagnostic capabilities among healthcare providers, and improved regional cooperation and knowledge exchange. As population aging accelerates, elderly health concerns become increasingly significant, necessitating community health education initiatives to enhance health awareness and specialized rehabilitation services. Finally, international collaboration and data sharing are crucial for improving global public health, particularly in low-income countries, where disease surveillance systems require establishment to enhance epidemiological data accuracy and reliability. Through comprehensive implementation of early screening, exposure reduction, tobacco control, medical resource optimization, elderly health awareness enhancement, and international collaboration, the disease burden of ILD and PS can be effectively reduced, providing valuable insights for managing other chronic respiratory conditions.

Limitations and future research directions

This research presents several limitations. Firstly, regarding data sources, ILD and PS prevalence in low-income nations may be underestimated due to inadequate diagnostic capabilities and incomplete disease registries. Consequently, where reliable data is unavailable, GBD estimates rely heavily on modeling processes, predictor variables, or historical trends, introducing potential uncertainty. Secondly, regarding research methodology, despite employing various statistical approaches, including the APC model and BAPC model, these methods may retain limitations in addressing data uncertainty and complexity. For instance, BAPC model predictions depend on historical data and underlying assumptions, which may not accurately reflect future trends. Finally, in assessing disease burden, this study primarily focused on metrics such as DALYs, without fully addressing these diseases’ long-term impact on patient quality of life and associated economic implications. Future studies should further investigate the economic impacts of ILD and PS, particularly in low-income regions and countries, to provide more comprehensive public health implications assessment.

The observed increase in the incidence rates of ILD may reflect a confluence of diagnostic refinement and therapeutic advancements. Since 1990, classifications of ILD have evolved considerably, driven by advances in imaging techniques, such as HRCT, and histopathology. Notably, the 2013 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) multidisciplinary criteria introduced HRCT-based subclassification of fibrotic patterns [36], while the 2022 ATS/ERS/Japanese Respiratory Society/American College of Chest Physicians (JRS/ALAT) guideline expanded the diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis to include non-smoker-associated usual interstitial pneumonia and clarified indications for antifibrotic therapy [5]. Concurrently, the formalization of “progressive pulmonary fibrosis” in 2020 broadened the recognition of phenotypes, capturing fibrosing ILDs with treatment-refractory decline [37]. These diagnostic updates have enhanced precision but may introduce temporal heterogeneity by reclassifying previously undifferentiated cases.

Moreover, therapeutic advancements—including antifibrotics such as nintedanib and pirfenidone, and biologics targeting the fibrogenic pathways—have initiated a fundamental shift toward early diagnosis [38, 39]. Clinicians now emphasize definitive testing (e.g., HRCT and biopsy) to inform treatment decisions, particularly in progressive ILD subtypes [40]. This approach aligns with the expansion of multidisciplinary care and guidelines promoting proactive diagnosis, such as the 2022 IPF guidelines [5]. Although this study did not directly measure the impact of therapy, the combined effect of improved diagnostics and innovative therapies likely influences the increasing incidence rates. Subsequent longitudinal studies should account for these variables to distinguish between genuine epidemiological patterns and diagnostic and treatment-related effects.

Additional research should examine these aspects more thoroughly, particularly in low-income regions. Comprehensive studies on the economic impact of ILD and PS, particularly in low-income areas, are necessary to assess their complete public health implications. Data collection efforts in low-resource settings require enhancement to improve the accuracy of prevalence estimates and reduce dependence on model-based predictions. Longitudinal research is essential to better understand the natural progression of ILD and PS and assess intervention effectiveness over time. Research should explore new diagnostic technologies (e.g., low-dose spiral CT and cfDNA methylation models) to enhance early detection rates and distinguish between benign and malignant conditions [23]. International collaboration should be strengthened to exchange best practices and resources, particularly in regions with limited healthcare infrastructure. Addressing these challenges and pursuing these research directions will enhance understanding of ILD and PS and inform effective public health policies.

Conclusions

This research demonstrates a significant global increase in the burden of diseases such as ILD and PS from 1990 to 2021, particularly in regions with high SDI. The findings indicate that incidence rates, mortality, and DALYs associated with ILD and pulmonary nodular disease are substantially higher among older adults and males. A significant correlation exists between the SDI and the ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR for these conditions. Given ongoing global trends in population aging and industrialization, the burden of these diseases is projected to continue increasing. Consequently, implementing comprehensive intervention strategies is essential, with a focus on reducing exposure to non-genetic risk factors (including environmental pollution and smoking), enhancing early diagnostic capabilities, and strengthening screening measures for high-risk populations to achieve improved lung health globally.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation staff and its collaborators who prepared these publicly available data. We would like to thank TopEdit (https://www.topeditsci.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

GBD Collaborator: Luna Zhao

Abbreviations

- ILD

Interstitial Lung Disease

- PS

Pulmonary Sarcoidosis

- GBD

Global Burden of Disease

- ASIR

Age-Standardized Incidence Rate

- ASMR

Age-Standardized Mortality Rate

- ASDR

Age-Standardized Disability Rate

- DALYs

Disability-Adjusted Life Years

- AAPC

Average Annual Percentage Change

- APC

Age-Period-Cohort

- BAPC

Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort

- EAPC

Estimated Annual Percentage Change

- SDI

Sociodemographic Index

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- KL-6

Krebs von den Lungen-6 (a serum biomarker)

- SP-D

Surfactant Protein D

- ATS/ERS

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society

- JRS/ALAT

Japanese Respiratory Society/American College of Chest Physicians

Authors’ contributions

L Zhao, D Liu, Y Zhou, Y Jia, H Liu, Y Liu, G Lv, Y Zhang and W Mo designed the study. L Zhao, J Li, J Ren, Y Zhang and N Wang analyzed the data and performed the statistical analyses. L Zhao, W Zhang, J Liu, J Ma and C Wu drafted the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed the drafted the manuscript for critical content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Corps Guiding Science and Technology Program Projects (grant number 2023ZD019).

Data availability

GBD study 2021 data resources are available online from the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is based on data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study. The GBD study uses deidentified data, and a waiver of informed consent was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. As our research utilized this publicly available, deidentified dataset, additional ethics approval for our specific analysis was not required. This approach meets the ethical guidelines for secondary data analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Althobiani MA, Russell AM, Jacob J, Ranjan Y, Folarin AA, Hurst JR, Porter JC. Interstitial lung disease: a review of classification, etiology, epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1296890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griese M. Etiologic Classification of Diffuse Parenchymal (Interstitial) Lung Diseases. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Maher TM. Interstitial lung disease: A review. JAMA. 2024;331(19):1655–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khor YH, Ng Y, Barnes H, Goh NSL, McDonald CF, Holland AE. Prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis without anti-fibrotic therapy: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(157):190158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, Kreuter M, Lynch DA, Maher TM, Martinez FJ, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an Update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valenzuela C, Cottin V. Epidemiology and real-life experience in progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2022;28(5):407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guziejko K, Moniuszko-Malinowska A, Czupryna P, Dubatówka M, Łapińska M, Raczkowski A, Sowa P, Kiszkiel Ł, Minarowski Ł, Moniuszko M et al. Assessment of Pulmonary Function Tests in COVID-19 Convalescents Six Months after Infection. J Clin Med. 2022;11(23):7052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):585–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GBD 2019 Chronic Respiratory Diseases Collaborators. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;59:101936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Q, Huang S, Xu H, Peng J, Wang P, Li S, Zhao J, Shi X, Zhang W, Shi L, et al. The burden of mental disorders in Asian countries, 1990–2019: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng Q, Jiang D. Global trends of interstitial lung diseases from 1990 to 2019: an age-period-cohort study based on the global burden of disease study 2019, and projections until 2030. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1141372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma X, Zhu L, Kurche JS, Xiao H, Dai H, Wang C. Global and regional burden of interstitial lung disease and pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Thorax. 2022;77(6):596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fei Y, Yu H, Liu J, Gong S. Global, regional, and National burden of geriatric depressive disorders in people aged 60 years and older: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2025;24(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao T, Lv T. Causal relationship between serum metabolites and interstitial lung disease in humans: A Mendelian randomization study. Technol Health Care. 2024;32(5):3485–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukui T, Mamesaya N, Takahashi T, Kishi K, Yoshizawa T, Tokito T, Azuma K, Morikawa K, Igawa S, Okuma Y, et al. A prospective phase II trial of First-Line osimertinib for patients with EGFR Mutation-Positive NSCLC and poor performance status (OPEN/TORG2040). J Thorac Oncol. 2025;20(5):665–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halder P, Chattopadhyay A, Rathor S, Saha S. Nested multilevel modelling study of smoking and smokeless tobacco consumption among middle aged and elderly Indian adults: distribution, determinants and socioeconomic disparities. J Health Popul Nutr. 2024;43(1):182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiran T, Halder P, Sharma D, Mehra A, Goel K, Behera A. Distribution and association of depression with tobacco consumption among middle-aged and elderly Indian population: nested multilevel modelling analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional survey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2025;44(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halder P, Kansal S, Sarkar S, Das A. Oral Cancer screening among Indian women within reproductive age-group: coverage, determinants, socio-economic disparities. J Med Care Res. 2024;287(4):365.

- 19.Gandhi SA, Min B, Fazio JC, Johannson KA, Steinmaus C, Reynolds CJ, Cummings KJ. The impact of occupational exposures on the risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2024;21(3):486–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arcana RI, Crișan-Dabija RA, Caba B, Zamfir AS, Cernomaz TA, Zabara-Antal A, Zabara ML, Arcana Ș, Marcu DT, Trofor A: Speaking of the "Devil": Diagnostic Errors in Interstitial Lung Diseases. J Pers Med. 2023;13(11):1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Pritchard D, Adegunsoye A, Lafond E, Pugashetti JV, DiGeronimo R, Boctor N, Sarma N, Pan I, Strek M, Kadoch M, et al. Diagnostic test interpretation and referral delay in patients with interstitial lung disease. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cano-Jiménez E, Vázquez Rodríguez T, Martín-Robles I, Castillo Villegas D, Juan García J, Bollo de Miguel E, Robles-Pérez A, Ferrer Galván M, Mouronte Roibas C, Herrera Lara S, et al. Diagnostic delay of associated interstitial lung disease increases mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang W, Zhang X, Zhang J, Chen X, Huang H, He B, Qin W, Zhu H. Multimodal data generative fusion method for complex system health condition Estimation. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):20026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren J, Chen F, Liu Q, Zhou Y, Cheng Y, Tian P, Wang Y, Li Y, He Y, Liu D, et al. Management of pulmonary nodules in non-high-risk population: initial evidence from a real-world prospective cohort study in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135(8):994–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniatopoulos G, Hunter DJ, Erskine J, Hudson B. Large-scale health system transformation in the united Kingdom. J Health Organ Manag. 2020;ahead–of–print(ahead–of–print):325–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lungen M, Dredge B, Rose A, Roebuck C, Plamper E, Lauterbach K. Using diagnosis-related groups. The situation in the united Kingdom National health service and in Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2004;5(4):287–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamburg MA, Cohen M, DeSalvo K, Gerberding J, Khaldun J, Lakey D, MacKenzie E, Palacio H, Shah NR. Building a National public health system in the united States. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(5):385–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence A, Myall KJ, Mukherjee B, Marino P: Converging Pathways: A Review of Pulmonary Hypertension in Interstitial Lung Disease. Life (Basel). 2024;14(9):1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gandhi S, Tonelli R, Murray M, Samarelli AV, Spagnolo P. Environmental Causes of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(22):16481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Charokopos A, Moua T, Ryu JH, Smischney NJ. Acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease in the intensive care unit. World J Crit Care Med. 2022;11(1):22–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alarcon-Calderon A, Vassallo R, Yi ES, Ryu JH. Smoking-Related interstitial lung diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2023;43(2):273–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vicol C, Arcana RI, Trofor AC, Melinte O, Cernomaz AT. Why making smoking cessation a priority for rare interstitial lung disease smokers?. Tob Prev Cessat. 2024;23(10):18332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Jeganathan N, Sathananthan M. The prevalence and burden of interstitial lung diseases in the USA. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8(1):00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Lionis C, Midlöv P. Prevention in the elderly: A necessary priority for general practitioners. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;23(1):202–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budreviciute A, Damiati S, Sabir DK, Onder K, Schuller-Goetzburg P, Plakys G, Katileviciute A, Khoja S, Kodzius R. Management and prevention strategies for Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. Front Public Health. 2020;8:574111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antoniou KM, Margaritopoulos GA, Tomassetti S, Bonella F, Costabel U, Poletti V. Interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(131):40–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Ryerson CJ, Myers JL, Kreuter M, Vasakova M, Bargagli E, Chung JH, Collins BF, Bendstrup E, et al. Diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in adults. An official ATS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(3):e36–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong AW, Ryerson CJ, Guler SA. Progression of fibrosing interstitial lung disease. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watase M, Mochimaru T, Kawase H, Shinohara H, Sagawa S, Ikeda T, Yagi S, Yamamura H, Matsuyama E, Kaji M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(3):e0283288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lederer C, Storman M, Tarnoki AD, Tarnoki DL, Margaritopoulos GA, Prosch H. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Breathe (Sheff). 2024;20(1):240006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

GBD study 2021 data resources are available online from the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).