Abstract

Background

Uterine fibroid constitutes a significant burden for affected women and research in this area has increasingly focused on patient-centered outcomes, with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) becoming crucial in related studies.

Objectives

We aim to summarize the key aspects and PROMs utilized in previous studies, recommend suitable tools for effective evaluations, and emphasize critical areas for future research.

Method

A literature search was conducted in the Medline, CINAHL, Embase, and Web of Science databases, covering the period from inception through October 2024.

Main results

75 studies met the criteria for inclusion and these studies highlight that PROMs utilized in research associated with uterine fibroids encompass a wide range of evaluations, spanning from quality of life, menstrual details, psychological well-being, pelvic floor conditions, pain intensity, menopause symptoms, to sexual function, body image, and other related assessments. Despite using various PROMs in published studies, current clinical trials on uterine fibroids mainly rely on general questionnaires, employing questionnaires specifically designed for uterine fibroids.

Conclusion

By summarizing the research, we provide an overview of existing PROMs for uterine fibroids, revealing a gap due to the lack of specific PROMs. This review contributes to uterine fibroid research by promoting accurate assessments, leading to better treatment options and enhanced patient quality of life.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12905-025-03926-6.

Keywords: Uterine fibroids, Questionnaires, Patient-reported outcome measures, Quality of life

Introduction

Uterine fibroids, the most common benign gynecologic tumors, affect 20–40% of women of reproductive age and up to 80% of Black women by age 50 years [1, 2]. They cause uncomfortable symptoms such as heavy menstrual bleeding, abdominal discomfort, increased urinary frequency, subfertility, chronic pelvic pain, and iron-deficiency anemia, which can strongly affect women’s health. Two-thirds of women with uterine fibroids report feeling tired or worn out, and over 40% express feeling sad or discouraged some, most, or all of the time [3]. Besides, uterine fibroids have profound daily - life consequences, significantly affecting various aspects of women’s lives. Related symptoms and mental stress can decrease productivity, increase absenteeism, and put a strain on intimate partnerships.

Although fibroids are generally non - life - threatening, they can take a significant toll on a woman’s quality of life. As a result, research in this field has gradually shifted its focus towards patient - centered outcomes [4]. The reason for this shift is that, despite their benign nature and effective manageability [5, 6]uterine fibroids still pose a substantial burden on women’s anxiety [7–9] levels and overall well-being [10]. Consequently, many contemporary clinical studies about treatment and prognosis prioritize outcome indicators like patients’ quality of life [11]. Besides, with the rising popularity of emerging treatment options, it becomes all the more crucial to understand the significance of accurate and responsive Patient - Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in evaluating how effective these treatments truly are [12, 13].

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures (PROMs), reporting patients’ views of their symptoms, functional status, and health-related quality of life (QoL), can be used to quantify the psychological impacts of diseases such as uterine fibroids, evaluate the outcomes of therapeutic management, and influence healthcare organization and delivery [14]. Despite the benign nature and high treatability of uterine fibroids, high levels of uterine fibroid-related anxiety, bleeding, and other negative impacts constitute a significant burden for affected women, thereby necessitating comprehensive assessment and focus [9, 15–17]. However, the absence of a summary concerning the key aspects and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) employed in uterine fibroid research has obscured vital insights, hindered the identification of valuable points, and impeded the progression of research efforts.

In this review, we aim to summarize the focused aspects and PROMs used in previous studies on uterine fibroids, recommend available PROMs for effective evaluations, highlight crucial directions for future research, and promote advancements in this field.

Methods

Search strategy and article selection

This study is a scoping review aimed at mapping the existing literature on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in patients with uterine fibroids, and a comprehensive literature search was conducted using Medline, CINAHL, Embase, and Web of Science databases from inception to October 2024 (Literature Search Strategy was shown supplement). The search strategy consisted of (1) the construct of interest: patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs); (2) the target population: leiomyoma; and (3) excluded standards. The full search strategy of all databases is included as supplementary material. The results of the searches were consolidated, and duplicate records were eliminated using Endnote X9.

Article eligibility criteria

We considered studies for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) assessed patient-reported outcome in uterine fibroid patients, (2) utilized a Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) instrument, and (3) were full-text original articles published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. Exclusion criteria were applied to studies that: (1) employed only a portion or an unvalidated short form of a Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (PROM), (2) were published in languages other than English, and (3) were published as abstracts, letters, theses, or editorials.

Selection of studies

Two independent researchers conducted the initial screening of potentially eligible studies by reviewing titles and abstracts from the retrieved studies. Full texts were then scrutinized for abstracts that aligned with the inclusion criteria. In cases of disagreement, conflicts were resolved through discussion.

Results

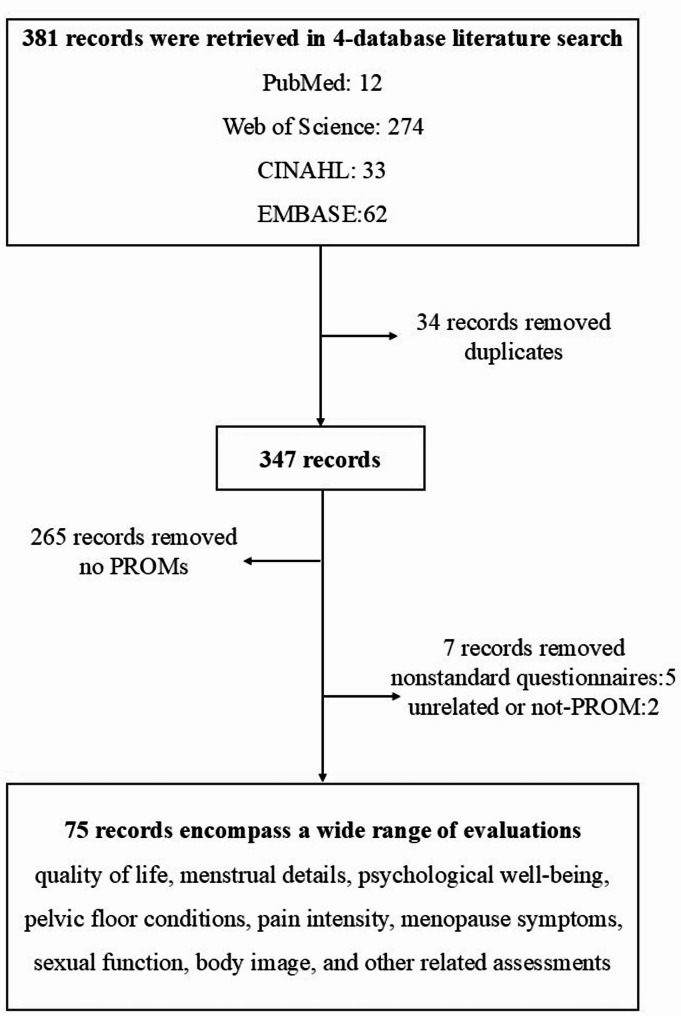

A total of 381 records were retrieved from four databases (Fig. 1). After removing 34 duplicate records, 265 unrelated records, and seven non-standard questionnaires, 75 records met the eligibility criteria and were included for comprehensive analysis (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow of the literature search

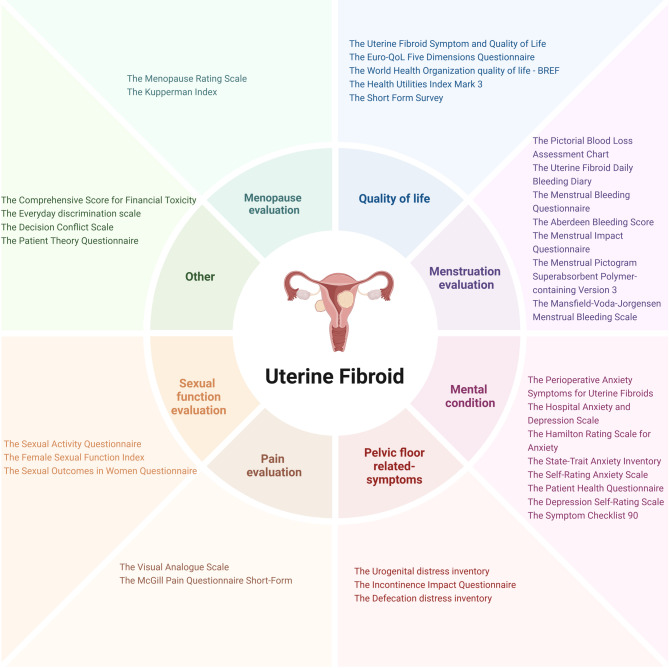

Patient-reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) utilized in research associated with uterine fibroids encompass a wide range of evaluations, spanning from quality of life, menstrual details, psychological well-being, pelvic floor conditions, pain intensity, menopause symptoms, to sexual function, body image, and other related assessments (Fig. 2). Although various Patient-Reported Outcome Measures appear in published studies, contemporary clinical trials on uterine fibroids primarily employ general questionnaires designed for multiple conditions. Besides, a limited number of studies and clinical trials utilize questionnaires (4 PROMS: UFS-QoL, UF-DBD, PASM-UF, FSD) specifically designed for uterine fibroids (Table 1), and only 16 studies were about validation of PROMs (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROMs) framework for uterine fibroids

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of proms utilized in uterine fibroid research

| PROMs | Introduction | Specific for uterine fibroid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | |||

| The Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life | Generic measure of health-related quality of life | Yes | |

| The Short Form Survey | Physical functioning, social/role functioning, mental and general health, perceptions, bodily pain, and vitality | No | |

| The Short Form Survey | Generic measure of health-related quality of life | No | |

| The EuroQoL Five Dimensions Questionnaire | Generic measure of health-related quality of life | No | |

| The Health Utilities Index Mark 3 | Health and related quality of life: vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, and pain | No | |

| The World Health Organization quality of life | Overall quality of life and general health: physical health, psychological, social relationships and environment | No | |

| Menstruation evaluation | |||

| The Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart | Semi-quantitative evaluation of menstrual blood loss: the number of tampons used and the degree to which they are stained with blood | No | |

| The Aberdeen Bleeding Score | Evaluate menstrual symptoms and quality of life | No | |

| The Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire | Menstrual and Gynecological symptoms | No | |

| The Mansfield-Voda-Jorgensen Menstrual Bleeding Scale | Quantified bleeding | No | |

| The Menstrual Pictogram Superabsorbent Polymer-containing Version 3 | Quantified bleeding | No | |

| The Uterine Fibroid Daily Bleeding Diary | Rate the severity of vaginal bleeding in the past 24 hours’ from “No vaginal bleeding,” to “Very severe” | Yes | |

| The Menstrual Impact Questionnaire | Measure the effect of HMB on a woman’s self-assessment of menstrual blood loss (MBL), limitations in social/leisure activities, physical activities, and ability to work | No | |

| Mental condition evaluation | |||

| The Perioperative Anxiety Symptoms for Uterine Fibroids | Measure the perioperative anxiety symptoms of uterine fibroids: pain, lack of appetite, fatigue (tiredness), disturbed sleep, and anxiety | Yes | |

| The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale | General anxiety disorder | No | |

| The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | Measure to detect depression and anxiety | No | |

| The Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety | Measure anxiety severity: psychological and somatic symptoms associated with anxiety | No | |

| The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | General anxiety disorder | No | |

| The Symptom Checklist 90 | Distinguish patients with/without psychosomatic diseases: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, photic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, others | No | |

| The Patient Health Questionnaire | Screening, diagnosing, monitoring and measuring the severity of depression | No | |

| The Depression Self-Rating Scale | Measure the affective, psychological, and somatic aspects of depression, | No | |

| Pelvic floor related- symptoms | |||

| The Urogenital distress inventory | Assesses the presence and experienced bother of pelvic floor symptoms associated with lower urinary tract dysfunction: irritative, stress, and obstructive/discomfort symptoms | No | |

| The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire | Measure disease-specific quality of life in women with stress urinary incontinence | No | |

| The Defecation distress inventory | Assesses the presence and experienced bother of defecatory symptoms: constipation, painful defecation, fecal incontinence, and flatus incontinence | No | |

| Pain evaluation | |||

| The McGill Pain Questionnaire Short-Form | Provide quantitative measures of clinical pain that would capture its sensory, affective and other qualitative components, and allow statistical analysis of data collected during clinical research and practice | No | |

| The Visual Analogue Scale | Measure pain intensity from 0 “no symptoms” to 10 “very severe symptoms | No | |

| Fibroid Symptom evaluation | |||

| The Fibroid Symptom Diary | Assessed fibroid-related bleeding severity, menstrual cramping, and fatigue. | Yes | |

| Sexual function evaluation | |||

| The Sexual Activity Questionnaire | Focused on the relational, emotional, and behavioral aspects of sexual activity | No | |

| The Sexual Outcomes in Women Questionnaire | Assess the impact of pelvic problems on sexual desire, frequency, satisfaction, orgasm, and discomfort | No | |

| The Female Sexual Function Index | Measure female sexual function | No | |

| The Questionnaire for Screening Sexual Dysfunctions | Detect sexual dysfunctions | No | |

| Body Image evaluation | |||

| The Body Image Scale | Measure body image concerns | No | |

| Menopause evaluation | |||

| The Menopause Rating Scale | Measure the severity of aging-symptoms; somato-vegetative symptoms: sweating/hot flushes, heart discomfort, sleep problems, joint and muscle problems, categorized; psychological symptoms: depressive mood, irritability, anxiety, and physical/mental exhaustion, categorized; urogenital symptoms: sexual problems, bladder problems, and vaginal dryness, categorized. | No | |

| The Kupperman Index | Measure the severity of aging-symptoms: urinary infection, sexual complaints, sweating/hot flushes, palpitation, vertigo, headache, paresthesia, formication, arthralgia, myalgia, fatigue, nervousness, melancholia | No | |

| Other | |||

| The Patient Theory Questionnaire | Evaluate patients’ beliefs about the causes of myomas | No | |

| The Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity | Assess objective and subjective financial distress experienced by patients of their treatment. | No | |

| The Decision Conflict Scale | Measures personal perceptions of: option - choosing uncertainty; modifiable uncertainty - contributing factors; effective decision - making | No | |

| The Everyday discrimination scale | Assess the health effects of perceived discrimination | No | |

Quality of life assessment has emerged as essential for patients with uterine fibroids, particularly in evaluating and comparing levels before and after treatment. The Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life questionnaire specifically evaluates fibroid-related quality of life and represents the most widely used self-administered instrument for assessing fibroid-related symptoms and health-related QoL [18, 19]. However, the remaining six questionnaires constitute general assessment tools not specific to this condition.

More than 25% of patients with uterine fibroids experience prolonged or heavy menstrual bleeding [20]potentially leading to iron deficiency anemia [21]. Therefore, this prevalence necessitates consideration of bleeding in uterine fibroid research, with seven menstruation-related questionnaires currently in use. These instruments include the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) [22]Aberdeen Bleeding Score, Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire (MBQ), Mansfield-Voda-Jorgensen Menstrual Bleeding Scale (MVJ), the menstrual pictogram superabsorbent polymer-containing version 3 (MP SAP-c v3), and the Uterine Fibroid Daily Bleeding Diary (UF-DBD), which are utilized to evaluate menstrual blood loss [23, 24]. Additionally, the Menstrual Impact Questionnaire specifically assesses heavy menstrual bleeding’s impact on quality of life [25].

Research has demonstrated uterine fibroids’ significant impact on patients’ mental health, with improved mental state serving as a treatment effectiveness indicator [26]. Actually, anxiety regarding heavy bleeding and pelvic pain constitutes the primary stressor for patients with uterine fibroids [7]resulting in elevated rates of self-harm within this population [8]. 80% of American patients with uterine fibroids opt for surgery due to anxiety and malignancy concerns [27]. Disease-related anxiety represents the most prevalent emotional burden among these patients, primarily associated with fibroid size and number, treatment requirements, and potential side-effects [9]. Related to significant patient-reported health disabilities (including bodily pain, mental health, social functioning, and sex life satisfaction), uterine fibroids appear to be a vital psychosocial stressor; disability scores after fibroid diagnosis can exceed those in diabetes mellitus, heart disease, and breast cancer [28]. The following Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) were utilized to assess anxiety or depression in patients with uterine fibroids: the Perioperative Anxiety Symptoms related to Uterine Fibroids (PASM-UF), the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA), the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Zung’s Anxiety Self-Rating Scale, and Depression Self-Rating Scale [29, 30]. Among these, PASM-UF was specifically developed to evaluate anxiety symptoms related to uterine fibroids, encompassing pain, loss of appetite, fatigue, disturbed sleep, and anxiety [31].

Currently, there is a focus on fibroid surgery and its potential to improve bladder symptoms and defecatory function [32]. In this field, three commonly used tools are the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI), the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, and the Defecation Distress Inventory (DDI) [33]. Additionally, the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) were utilized for evaluating fibroid-related pain [34]. Meanwhile, the Fibroid Symptom Diary (FSD) served as a tool to assess fibroid-related pain, bleeding severity, menstrual cramping, and fatigue [35].

It is well-established that benign gynecological diseases adversely impact sexual function [36]. Although some patients hesitate to receive surgery like hysterectomy due to concerns about potential negative effects on their sexual well-being [37]research has shown that uterine artery embolization (UAE) can enhance the sexual and psychological well-being of women with symptomatic uterine fibroids [38]. Therefore, in order to elucidate the relationship between sexual function, disease, and treatment, and to optimize management and improve the sexual function of patients with uterine fibroid, it is crucial to consider the sexual function of patients. This This assessment involves various patient-reported outcome measures, including the Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ), the Sexual Outcomes in Women Questionnaire (SHOW-Q), the Female Sexual Function Index, and the Questionnaire for Screening Sexual Dysfunctions (QSD) [38, 39]. Furthermore, when addressing symptoms associated with menopause in patients with fibroids, the Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) and the Kupperman Index have been employed [40, 41].

Body image refers to an individual’s cognitive or affective evaluation of their body or appearance, which may manifest as either positive or negative perceptions [42]. In recent decades, research on body image has expanded significantly. Studies have shown that undergoing treatment for fibroids can affect one’s perception of body image post-procedure [43]. Consequently, researchers frequently employ the Body Image Scale and the Physical Component Summary (PCS) to generate evidence and guidelines for systematic fibroid management [32, 43].

A limited number of studies focus on financial status, decision conflict, and patients’ beliefs regarding the causes of myomas. These research efforts employ patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) such as the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity, the Decision Conflict Scale, the Patient Theory Questionnaire, and the Zenz Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) [44].

Last but not least, among the four Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) designed for uterine fibroids (Table 2), three focused primarily on anxiety (PASM-UF), bleeding (UF-DBD), or symptoms (FSD) respectively. Consequently, to comprehensively assess different aspects of uterine fibroids, multiple questionnaires need to be administered, creating a potentially time-intensive and demanding process. Only one PROM assessed both symptoms and quality of life (UFS-QoL). Therefore, future development of PROMs for uterine fibroids should emphasize comprehensive assessment to enhance clinical utility and research applications.

Table 2.

Summary of proms specific for uterine fibroid

| PROM | Construct(s) | Target population | Mode of administration | Administration time | Recall period | Items (No.) | Scorning rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life (UFS-QoL) | Symptom severity scale (8-item) and HRQL questions (29-item; 6 subscales: concern, activities, energy/mood, control, self-consciousness, and sexual function) | Patients with uterine fibroids | Self-administered, interview-based | 10–15 min | Past 3 months | 37 | 5 points scale (1–5) |

| The Perioperative Anxiety Symptoms for Uterine Fibroids (PASM-UF) | Measure the perioperative anxiety symptoms of uterine fibroids: pain, lack of appetite, fatigue (tiredness), disturbed sleep, and anxiety | Patients with uterine fibroids | Self-administered, interview-based | 2–3 min | Now | 5 | 10 points scale (0–10) |

| The Uterine Fibroid Daily Bleeding Diary (UF-DBD) | Quantified fibroid-related bleeding: Rate the severity of any vaginal bleeding in the past 24 hours’ with “No vaginal bleeding,” “Spotting,” “Mild,” “Moderate,” “Severe,” or “Very severe”. | Patients with uterine fibroids | Self-administered, interview-based | 1–2 min | past 24 h | 1 | 0–10 (0 =“No vaginal bleeding”, 1 = “Spotting”, 4 = “Mild”, 6 = “Moderate”, 8 = “Severe”, 10 = “Very Severe”) |

| The Fibroid Symptom Diary (FSD) | Assessed fibroid-related bleeding severity, menstrual cramping, and fatigue (11 items): 5 items for Menstrual bleeding or spotting; 1 item for cramping (distinct from other pain); 1 item for fatigue; 1 item for and bloating; 3 items for other fibroid-related pain. | Patients with uterine fibroids | Self-administered, interview-based | 1–2 min | past 24 h | 11 | Depends |

Discussion

This review synthesizes the current landscape of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) utilized in uterine fibroid research. Our analysis reveals that while the multifaceted impact of fibroids on patient well-being is increasingly recognized—spanning quality of life (QoL), menstrual burden, mental health, pelvic floor dysfunction, pain, menopausal symptoms, sexual function, and body image [45]—the methodological approaches to capturing this complexity remain heterogeneous and often inadequate [3, 46, 47].

Moreover, the significance of quality of life assessment in uterine fibroids research has been established, highlighting the need for more evidence to support the selection of the most fitting Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). The UFS-QoL, disease-specific and extensively validated [48–51]offers a valuable tool for comprehensively evaluating fibroid-related symptoms and their impact on QoL. However, the frequent reliance on generic PROMs in research and clinical trials poses a significant limitation. These instruments fail to capture the distinct symptomatology and lived experiences unique to uterine fibroid patients, potentially obscuring critical treatment effects or patient burdens [52–54].

Heavy menstrual bleeding, a hallmark symptom, highlight the challenge of quantifying subjective experiences. Tools like the Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart (PBAC) and Aberdeen Bleeding Score provide structured approaches for assessing blood loss, facilitating treatment evaluation. Nevertheless, their practical limitations and variable correlation with objective measures [55, 56]leading to an unmet need for more precise, patient-friendly, and clinically meaningful assessment methodologies in this domain.

Beyond physical symptoms, the psychological health of uterine fibroids—including heightened anxiety, depression, and distress—demand greater attention [57, 58]. These factors are intrinsically linked to treatment adherence, decision-making, and long-term recovery. Integrating validated psychological assessments into both research protocols and clinical practice is therefore not merely supplementary but essential for a holistic understanding of patient needs and for tailoring effective, personalized management strategies. Future research must prioritize investigating the underlying mechanisms linking fibroids to mental health burden and rigorously evaluating targeted psychosocial interventions.

As research into the quality of life of patients with uterine fibroids progresses, sexual function and body image have increasingly emerged as pivotal areas of interest. These dimensions are vital to patients’ overall well-being [59, 60]. Consequently, it is essential to conduct more studies that focus on the impact of treatment on patients’ sexual function and body image, in order to refine and enhance treatment plans [61].

A critical observation from our synthesis is the persistent disconnect between the recognized multidimensionality of the fibroid experience and the tools used to measure it. Clinical trials predominantly utilize generic PROMs, with only a minority employing the disease-specific UFS-QoL. Moreover, even existing fibroid-specific tools often capture a limited spectrum of impact, necessitating burdensome combinations of multiple questionnaires to achieve a comprehensive assessment [62]. This fragmented approach creates significant respondent burden and analytical complexity, hindering both research efficiency and clinical utility.

Consequently, there is a compelling and urgent need to advance PROM development and application in this field. Rather than seeking a single “best” instrument, our aim is to guide researchers and clinicians towards a more sophisticated approach: selecting or developing PROMs based on a clear conceptual framework of fibroid impact that aligns with the specific research question or clinical context. This requires prioritizing instruments with proven validity, reliability, responsiveness, and relevance to the specific dimensions under investigation. Optimizing assessment could involve refining existing tools, developing modular instruments, or creating novel, comprehensive fibroid-specific PROMs capable of capturing the full breadth of patient experiences efficiently [63].

Conclusion

By summarizing previous research, we provide valuable references associated with assessment and PROMs for future studies on uterine fibroids. Furthermore, we highlight the existing gap due to the current lack of uterine fibroids-specific PROMs. Additionally, recommending effective Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) tools will assist researchers in more accurately assessing treatment efficacy and improvements in patients’ quality of life. These efforts will contribute to advancements in the field of uterine fibroids, offering patients better treatment options and enhanced quality of life.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Shuhao Yang: Design, data collection, analysis, and drafting the manuscript. Qing Yan, Fei Liu, Wei Yan: Data collection. Suzhen Yuan, Minli Zhang, Zhangying Wu: Analysis. Ya Li: Study conception, review of study design and review of draft manuscript. Tao Xiang: review of draft manuscript; Wenwen Wang: Study conception, review of study design and review of draft manuscript.dy design and review of draft manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2704100); Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan -Basic Research (2023020201010041); National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Regional Project (81760266).

Data availability

Data is provided within supplementary information.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tao Xiang, Email: 173930870@qq.com.

Wenwen Wang, Email: wenwenwang@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallach EE, Vlahos NF. Uterine myomas: an overview of development, clinical features, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(2):393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hervé F, Katty A, Isabelle Q, Céline S. Impact of uterine fibroids on quality of life: a National cross-sectional survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;229:32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fennessy FM, Kong CY, Tempany CM, Swan JS. Quality-of-life assessment of fibroid treatment options and outcomes. Radiology. 2011;259(3):785–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahase E. Uterine fibroids: NICE recommends new treatment option for moderate to severe symptoms. BMJ. 2024;386:q1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali M, Ciebiera M, Wlodarczyk M, et al. Current and emerging treatment options for uterine fibroids. Drugs. 2023;83(18):1649–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brito LG, Panobianco MS, Sabino-de-Freitas MM, et al. Uterine leiomyoma: Understanding the impact of symptoms on womens’ lives. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiuve SE, Huisingh C, Petruski-Ivleva N, Owens C, Kuohung W, Wise LA. Uterine fibroids and incidence of depression, anxiety and self-directed violence: a cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2022;76(1):92–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knudsen NI, Wernecke KD, Siedentopf F, David M. Fears and concerns of patients with uterine Fibroids - a survey of 807 women. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(9):976–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonanni V, Reschini M, La Vecchia I, et al. The impact of small and asymptomatic intramural and subserosal fibroids on female fertility: a case-control study. Hum Reprod Open. 2023;2023(1):hoac056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Go VAA, Thomas MC, Singh B, et al. A systematic review of the psychosocial impact of fibroids before and after treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(5):674–e708678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Q, Ciebiera M, Bariani MV, et al. Comprehensive review of uterine fibroids: developmental origin, pathogenesis, and treatment. Endocr Rev. 2022;43(4):678–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitale SG, Saponara S, Sicilia G, et al. Hysteroscopic diode laser myolysis: from a case series to literature review of incisionless myolysis techniques for managing heavy menstrual bleeding in premenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(3):949–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346:f167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alhazmi RA, Bukhari M. Perception of poor prognosis and psychological impact on the infertile couples who stop IVF therapy: cross sectional scientific perspective. Med Sci 2023;27(134).

- 16.Flory N, Lang EV. Distress in the radiology waiting room. Radiology. 2011;260(1):166–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yun X-Y, Chen S-J, Zheng Q-W. Targeted perioperative nursing combined with Propofol and Fentanyl for gynecological laparoscopic surgery. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med (eCAM) 2022:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 18.JB S, K C, NG G, et al. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeung SY, Kwok JWK, Law SM, Chung JPW, Chan SSC. Uterine fibroid symptom and Health-related quality of life questionnaire: a Chinese translation and validation study. Hong Kong Med J. 2019;25(6):453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet. 2001;357(9252):293–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnez J, Carmona F, Maitrot-Mantelet L, Dolmans MM, Chapron C. Uterine disorders and iron deficiency anemia. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(4):615–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kriplani A, Srivastava A, Kulshrestha V, et al. Efficacy of Ormeloxifene versus oral contraceptive in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding due to uterine leiomyoma. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(12):1744–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magnay JL, O’Brien S, Gerlinger C, Seitz C. A systematic review of methods to measure menstrual blood loss. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haberland C, Filonenko A, Seitz C, et al. Validation of a menstrual pictogram and a daily bleeding diary for assessment of uterine fibroid treatment efficacy in clinical studies. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bushnell DM, Martin ML, Moore KA, Richter HE, Rubin A, Patrick DL. Menorrhagia impact questionnaire: assessing the influence of heavy menstrual bleeding on quality of life. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(12):2745–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann B, Singh B, Brennan J, Blanck J, Segars JH. The impact of fibroid treatments on quality of life and mental health: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2024;121(3):400–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallicchio L, Harvey LA, Kjerulff KH. Fear of cancer among women undergoing hysterectomy for benign conditions. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(3):420–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Go VAA, Thomas MC, Singh B, et al. A systematic review of the psychosocial impact of fibroids before and after treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(5):674–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.You Z, Chen L, Xu H, Huang Y, Wu J, Wu J. Influence of Anemia on postoperative cognitive function in patients undergo hysteromyoma surgery. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:786070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park SA, Lee J, Kim HY. Virtual reality education program for women with uterine tumors treated by high-intensity focused ultrasound. Heliyon. 2024;10(1):e23759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Xu W, Sang G, Yu D, Shi Q. A measure for perioperative anxiety symptoms in patients with FUAS - treated uterine fibroids: development and validation. Int J Hyperth. 2022;39(1):525–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hehenkamp WJ, Volkers NA, Birnie E, Reekers JA, Ankum WM. Symptomatic uterine fibroids: treatment with uterine artery embolization or hysterectomy–results from the randomized clinical embolisation versus hysterectomy (EMMY) trial. Radiology. 2008;246(3):823–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Kooij SM, Hehenkamp WJ, Volkers NA, Birnie E, Ankum WM, Reekers JA. Uterine artery embolization vs hysterectomy in the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: 5-year outcome from the randomized EMMY trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):e105101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersson JK, Khan Z, Weaver AL, Vaughan LE, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Stewart EA. Vaginal Bromocriptine improves pain, menstrual bleeding and quality of life in women with adenomyosis: A pilot study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(10):1341–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deal LS, Williams VS, Fehnel SE. Development of an electronic daily uterine fibroid symptom diary. Patient. 2011;4(1):31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beyan E, İnan AH, Emirdar V, Budak A, Tutar SO, Kanmaz AG. Comparison of the effects of total laparoscopic hysterectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy on sexual function and quality of life. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8247207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrero S, Abbamonte LH, Giordano M, Parisi M, Ragni N, Remorgida V. Uterine myomas, dyspareunia, and sexual function. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voogt MJ, De Vries J, Fonteijn W, Lohle PN, Boekkooi PF. Sexual functioning and psychological well-being after uterine artery embolization in women with symptomatic uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(2):756–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacoby VL, Parvataneni R, Oberman E, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation of uterine leiomyomas: clinical outcomes during early adoption into surgical practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(4):915–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu NN, Kaw D, McCullough MF, Nsouli-Maktabi H, Spies JB. Menopause and menopausal symptoms after ovarian artery embolization: a comparison with uterine artery embolization controls. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(5):710–e715711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitade M, Kumakiri J, Kobori H, Murakami K. The effectiveness of Relugolix compared with leuprorelin for preoperative therapy before laparoscopic myomectomy in premenopausal women, diagnosed with uterine fibroids: protocol for a randomized controlled study (MyLacR study). Trials. 2024;25(1):343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kling J, Kwakkenbos L, Diedrichs PC, et al. Systematic review of body image measures. Body Image. 2019;30:170–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klock J, Radakrishnan A, Runge MA, Aaby D, Milad MP. Body image and sexual function improve after both myomectomy and hysterectomy for symptomatic fibroids. South Med J. 2021;114(12):733–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su WK, Coleman CM, Bossick AS, Lee-Griffith M, Wegienka G. Racial differences in planned hysterectomy procedure route. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2022;31(1):31–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fortin C, Flyckt R, Falcone T. Alternatives to hysterectomy: the burden of fibroids and the quality of life. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;46:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koga K, Fukui M, Fujisawa M, Suzukamo Y. Impact of diagnosis and treatment of uterine fibroids on quality of life and labor productivity: the Japanese online survey for uterine fibroids and quality of life (JOYFUL survey). J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49(10):2528–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morris JM, Liang A, Fleckenstein K, Singh B, Segars J. A systematic review of minimally invasive approaches to uterine fibroid treatment for improving quality of life and fibroid-Associated symptoms. Reprod Sci. 2023;30(5):1495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu W, Chen W, Chen J, et al. Adaptability and clinical applicability of UFS-QoL in Chinese women with uterine fibroid. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keizer AL, van Kesteren PJM, Terwee C, de Lange ME, Hehenkamp WJK, Kok HS. Uterine fibroid symptom and quality of life questionnaire (UFS-QOL NL) in the Dutch population: a validation study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):e052664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spies JB, Coyne K, Guaou Guaou N, Boyle D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves SM. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliveira Brito LG, Malzone-Lott DA, Sandoval Fagundes MF, et al. Translation and validation of the uterine fibroid symptom and quality of life (UFS-QOL) questionnaire for the Brazilian Portuguese Language. Sao Paulo Med J. 2017;135(2):107–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Churruca K, Pomare C, Ellis LA, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): A review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect. 2021;24(4):1015–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carrozzino D, Patierno C, Guidi J, et al. Clinimetric criteria for Patient-Reported outcome measures. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(4):222–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Critchley HOD, Babayev E, Bulun SE, et al. Menstruation: science and society. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(5):624–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitaker L, Critchley HO. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:54–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang H, Lau WB, Lau B, et al. A mass spectrometric insight into the origins of benign gynecological disorders. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2017;36(3):450–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiewa J, Mortlock S, Meltzer-Brody S, Middeldorp C, Wray NR, Byrne EM. A common genetic factor underlies genetic risk for gynaecological and reproductive disorders and is correlated with risk to depression. Neuroendocrinology. 2023;113(10):1059–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Curley CM, Johnson BT. Sexuality and aging: is it time for a new sexual revolution? Soc Sci Med. 2022;301:114865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kennedy V, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, et al. Can you ask? We just did! Assessing sexual function and concerns in patients presenting for initial gynecologic oncology consultation. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL. A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):477–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anchan RM, Spies JB, Zhang S et al. Long-term health-related quality of life and symptom severity following hysterectomy, myomectomy, or uterine artery embolization for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;229(3):275.e271-275.e217. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Frisch EH, Mitchell J, Yao M, et al. The impact of fertility goals on Long-term quality of life in Reproductive-aged women who underwent myomectomy versus hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30(8):642–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within supplementary information.