Abstract

Cancer research is undergoing a paradigm shift from solely studying tumor cells to investigating systemic effects of cancer in the tumor macroevironment, with an emphasis on the interactions between host organs and tumors. The theory of homeostasis is an important basis for explaining biological functions from the perspective of the organism. Organic homeostasis relies on brain-body crosstalk through interception, immunoception, nociception and other supervisory processes, guaranteeing normal physiological function. Recent studies reveal that malignant tumors can hijack and exploit the brain and its central-peripheral neuronal networks to disrupt the body's homeostasis. Tumors likely disrupt normal brain-body crosstalk by establishing bidirectional brain-tumor connections. On the contrary, organism utilize these mechanisms to hinder tumorigenesis and progression. Standing at the perspective of brain-body crosstalk also promotes the conceptional evolution of cancer initiation and development, and more importantly, provides additional insight for cancer treatment. In this review, we summarize current knowledge about brain-body crosstalk under tumor-bearing contexts and propose some novel anti-cancer strategies.

Graphical Abstract

Brain-body crosstalk participates in the battle between tumors and the organism: The homeostasis of the organism is collectively maintained by interoception, nociception, neuroception, endocriception, metaboception and immunoception. However, in tumor states, tumors hijack the brain-body crosstalk system to exploit these homeostatic mechanisms, thereby constructing a macroenvironment conducive to their survival and progression. While tumors hijack the brain-body crosstalk to reestablish homeostasis, the host organism simultaneously counteracts the tumor through brain-body crosstalk, safeguarding its intrinsic homeostasis from disruption. The brain-body crosstalk between tumors and multiple organs mediated by the HPA axis-driven humoral regulation and the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves plays a significant role in the battle between tumors and the organism. TME, tumor microenvironment; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; SAS, sympatho-adrenal system. This figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/).

Keywords: Brain-body, Cancer neuroscience, Drug repurposing, Homeostatic disruption, Neural circuity, Neuroimmune

Highlights

● Cancer research has experienced a conceptional evolution, from simply regarding cancer as an unorganized cell mass to a newborn organ. Therefore, standing at the perspective of interactions between organs provides novel insight for this area.

● The organic homeostasis is supervised and exerted respectively by interception, nociception, neuroception, endocriception, metaboception and immunoception, which are tightly associated with brain and other components of the nervous system.

● Tumors could hijack the brain-body crosstalk to facilitate their own survival and progression. In turn, the host could utilize this axis to constrain cancer development, and ideally promote cancer elimination.

● According to theory of brain-body crosstalk, the importance of approaches such as targeted treatment, combined therapy and comprehensive therapy is worthy of emphasis and implementation.

Introduction

Our understanding of cancer has moved beyond the intrinsic cellular alterations of tumors and changes in the local microenvironment, now placing greater emphasis on the interplay between tumors and the entire host organism. The paradigm of cancer treatment has shifted from a curative intent toward conceptualizing tumors as integral components of the organismal macroenvironment, emphasizing tumor interactions with multiple organ systems, particularly brain-body crosstalk under tumor conditions [1]. This perspective transitions from viewing tumors as"autonomous growths"to recognizing"neural-tumor communication"highlighting the systemic regulation of neural activity on tumor metabolism, immune evasion, and metastatic colonization [2].

The central nervous system (CNS) has a fundamental function in maintaining homeostasis, which ensures that functional parameters of various tissues remain within preset ranges. To achieve this, the CNS continuously receives information from both the external and internal environments. These ceaseless streams of information are centrally integrated and converted into functional output signals that are transmitted to the periphery. This bidirectional communication between the periphery and the CNS, termed the"body–brain axis"[3]. The body-brain axis is the foundation of brain-body crosstalk. Brain-body crosstalk involves dynamic dialogues mediated by neural/endocrine signaling with distant organs, primarily investigating the complex bidirectional relationship between the brain and the body. Brain-body crosstalk plays a pivotal role in preserving interoception, particularly in maintaining systemic health, enabling environmental adaptation, and responding to external challenges [4]. Numerous studies have shown that brain-body crosstalk significantly contributes to tumor initiation and progression [2, 5, 6].

It has long been hypothesized that psychosocial factors may influence cancer progression through alterations in sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity [7, 8]. Significant advances in cancer neuroscience have revealed that peripheral tumors are infiltrated by autonomic and sensory nerve fibers, which interact with diverse components of the tumor microenvironment to drive tumorigenesis and metastasis [9]. Tumors establish communication with the CNS through afferent sensory neurons, inflammatory cytokines, or neurotrophic factors [10]. Under tumor conditions, the nervous system dynamically engages in bidirectional brain-body dialogues to modulate tumor progression. Conversely, tumors release tumor-derived factors that reshape neural plasticity, thereby fostering tumor heterogeneity and therapy resistance [11]. The central nervous system can remotely regulate the progression of peripheral tumors through brain-body crosstalk, involving the remodeling of the tumor microenvironment and the modulation of cancer hallmarks. This interplay between tumors and the organism is mediated by interoception, nociception, neuroception, endocriception, metaboception, and immunoception. A deeper understanding of brain-body crosstalk mechanisms will not only elucidate tumor pathogenesis but also provide a scientific foundation for developing novel therapeutic and interventional strategies.

Our approach to comprehending tumors has transcended tumor-intrinsic cellular alterations and local microenvironment modifications, now encompassing how malignancies dynamically interact with the entire host organism. The nervous system, situated at the interface between the brain and body, continuously receives and transmits signals to maintain homeostasis and respond to salient stimuli. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that tumors disrupt this brain-body dialogue through neural and humoral pathways, leading to aberrant brain activity and disease progression. These findings underscore that brain-body crosstalk must be considered a central factor in developing therapeutic strategies for cancer [12]. This review explores brain-body crosstalk under physiological conditions and in the tumor context, elucidating their roles in tumor initiation and progression, while offering novel strategies for cancer treatment.

The macroenvironment of tumor: from innervated TME to brain-body crosstalk

To survive and proliferate, cancer cells must remodel their local environment to ensure a sufficient supply of metabolic fuels and evade immune destruction [13, 14]. To achieve this, they employ a multipronged strategy, secreting a plethora of proteins and metabolites that function within paracrine, endocrine and autocrine signaling circuits in the tumor microenvironment (TME) [15]. For example, tumors secrete IL-6, GDF15 and other substances that act on the brain, leading to systemic inflammation and anorexia [16]. From this perspective, tumors are no longer mere aggregates of cancer cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) components but rather complex entities comprising multiple functional elements [17]. Like normal organs, tumors exert systemic effects and interact with the entire organism, often culminating in life-threatening conditions such as cancer cachexia [18]. Moreover, even when tumors are not located in the brain itself, many cancer-related symptoms involve brain dysfunction (e.g., sleep disturbances in primary breast cancer) [19].

In 2020, our team specialized the tumor microenvironment into six typical microenvironments: hypoxic niche, immune microenvironment, metabolism microenvironment, acidic niche, innervated niche, and mechanical microenvironment [20]. We propose that neural-derived neurotransmitters or neuropeptide-mediated communication between nerves and cancer establishes a specific local microenvironment called the"innervation niche"[20]. As research between nerves and tumors deepens, people are increasingly aware of the close relationship between neurology and cancer science. In recent years, Monje and other scientists have proposed a new field called"cancer neuroscience"to better study how the nervous system communicates with cancer [21]. Cancer neuroscience has unveiled the critical role of the nervous system in tumor initiation, progression, invasion, and metastasis [22–24]. Since the discovery that brain tumors (e.g., glioblastoma) can form functional synapses with normal neurons in the brain [25] and that autonomic nerves robustly regulate the growth and metastasis of prostate and breast cancers through norepinephrine (NE) signaling [26–28], an increasing number of researchers have engaged in cancer neuroscience studies. On the other hand, the emergence of powerful tools for monitoring and manipulating neuronal activity in freely behaving animals, such as calcium imaging and optogenetics, has enabled microscopic-level investigations into how the nervous system interacts with tumors [29–31]. Advances in this field provide fresh perspectives and opportunities for understanding tumor biology and developing innovative anti-cancer therapies. By investigating neural-tumor interactions, novel therapeutic strategies can be developed to improve outcomes and quality of life for cancer patients.

Our understanding of tumors has transcended tumor-intrinsic cellular alterations and local microenvironment modifications, now focusing more on the interactions between tumors and the entire host organism (Fig. 1). Next, we will discuss the crucial role of brain-body crosstalk in maintaining internal environmental homeostasis, and explore how brain-body crosstalk under tumor conditions influence tumorigenesis and development.

Fig. 1.

The evolution of conceptual understanding of tumors. Modern oncology research has transcended the traditional confines of tumor-intrinsic cellular alterations and local microenvironment regulation, transitioning into a profound paradigm shift from a"localized lesion-centric framework"to a"whole-organism host-oriented framework", centering on mechanistic deciphering of systemic regulatory mechanisms underlying tumor-host interactions. During tumor-host interactions, brain-body crosstalk plays a critical role. TME, tumor microenvironment. This figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/)

Brain-body crosstalk: maintaining systematic homeostasis

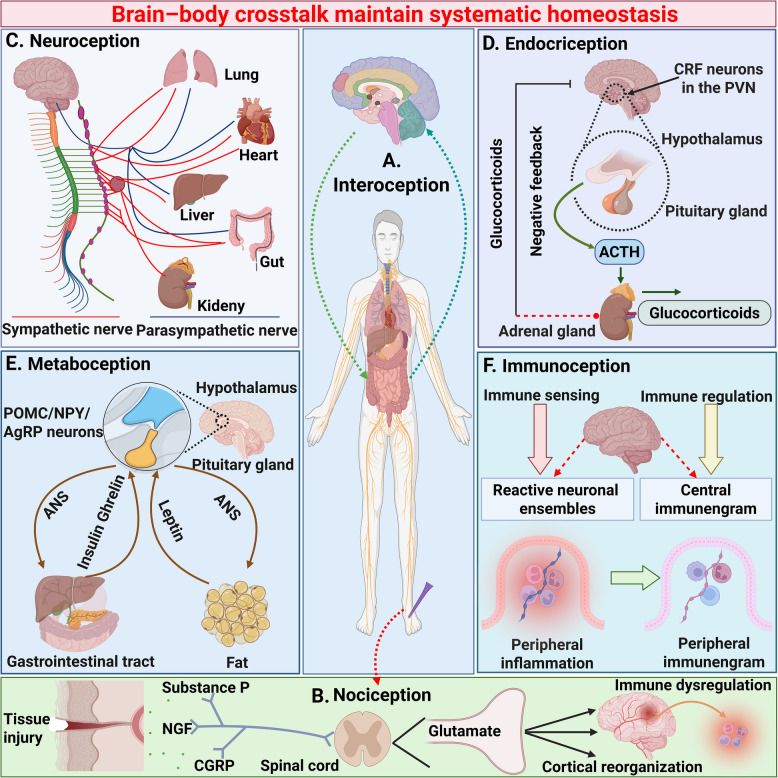

Under physiological conditions, brain-body crosstalk plays a crucial regulatory role in interoception, nociception, neuroception, endocriception, metaboception, immunoception. Understanding how brain-body crosstalk upholds homeostasis and health represents a compelling research frontier [2, 11, 32, 33] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Brain-body crosstalk determinant systematic homeostasis. Under physiological conditions, as the central processor of the body's systems biology regulation, the brain-body crosstalk maintains systematic homeostasis by regulating multiple organs through the parasympathetic nerve, the spinal cord-skin nociceptive loop, and multi-interface communication from the brain to metabolism, endocrine and immune systems, achieving real-time regulation of interoception, nociception, neuroception, endocriception, metaboception and immunoception. A Interoception, defined as the physiological homeostasis process perceived by the brain and involving multiple organs, plays a vital role in maintaining systemic stability. This homeostatic regulation relies on the perception of internal bodily states mediated by neural and humoral afferent pathways, which facilitate bidirectional signaling between the body and the brain; B Nociception is the neurobiological process through which an organism detects and interprets potential or actual tissue damage. When noxious stimuli (e.g., high temperature, mechanical pressure, chemical injury) activate nociceptors in the skin, the dorsal horn of the spinal cord performs primary integration of pain signals. These signals are then transmitted via the spinothalamic tract to the thalamus and further projected to the cerebral cortex. The brain initiates a cascade of responses to such injury, which may even trigger immune dysfunction due to neuro-immune crosstalk; C Neuroception refers to the nervous system's capacity to detect and interpret internal and external environmental cues, orchestrating a multilevel regulatory cascade from molecular signaling to behavioral responses. This adaptive mechanism enables the nervous system to anticipate risks and initiate context-specific physiological adjustments, primarily through the brain's dynamic modulation of multiple organ systems via sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves to maintain systemic homeostasis; D Endocriception refers to the physiological process through which organisms continuously monitor circulating metabolites, ions, hormonal and neurochemical signals via specific receptor-mediated mechanisms, and orchestrates the dynamic adjustment of hormonal secretion through intricate regulatory mechanisms. As exemplified by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which maintains endocrine homeostasis via bidirectional feedback regulation to adapt to internal and external stressors; E Metaboception in organisms involves dynamic brain-body crosstalk. The ANS governs energy homeostasis by orchestrating energy metabolism through bidirectional interactions with the gastrointestinal tract and adipose tissue, forming an integrated neuro-metabolic regulatory network; F The brain and immune system establish bidirectional communication, termed immunoception. This process enables the detection of immunological disturbances by mediating crosstalk between the immune and nervous systems, thereby mobilizing brain-body systems to restore systemic immune homeostasis. CRF, corticotropin releasing factor; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; ANS, autonomic nervous system; POMC, p-opiomelanocortin; NPY, neuropeptide Y; AgPR, agouti-related peptide. This figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/)

Interoception

The biological processes that maintain homeostasis and normal bodily functions involve the coordinated actions of multiple organ systems. These systems interact through complex multidirectional communication and possess their own regulatory mechanisms. Consequently, the brain can not only exchange information with the external environment via circulating molecules (such as those from blood and cerebrospinal fluid), but also transmit signals through nerves that innervate various organs. For example, the hypothalamus regulates digestive organs by releasing neuropeptide Y (NPY) to modulate appetite, while also controlling anterior pituitary hormone secretion through the hypophyseal portal system, thereby indirectly influencing the functions of peripheral organs such as the adrenal glands [34].

Such multi-layered communication mechanisms enable the organism to precisely regulate homeostatic maintenance processes [35]. The homeostatic process of the body, perceived by the brain and involving multiple organs, is called interoception [36]. Interoception refers to the perception of the body's internal state mediated through neural and humoral afferent pathways, arising from the transmission of signals from the body to the brain [37]. Interoceptive information guides the brain's efferent physiological regulation of the body to maintain health and is integrated into the representations of sensation, emotion, cognition, and motivation [36, 37]. Interoception serves as the foundation for maintaining homeostasis and its dysfunction is associated with various physiological and psychological disorders. The organism maintains interoceptive homeostasis through brain-body crosstalk.

Other perceptions

Other perceptions, such as nociception, neuroception, endocriception, metaboception, and immunoception, also play crucial roles in maintaining organismal homeostasis.

Under physiological conditions, the brain-body crosstalk precisely maintains interoceptive homeostasis through the coordinated interplay of the nervous, metabolic, endocrine and immune systems. This equilibrium serves as the foundation for adapting to internal and external environmental changes while preserving physiological balance. However, when external stressors such as infection, trauma, or psychological distress exceed the body’s adaptive capacity, homeostatic mechanisms are disrupted. Such dysregulation can trigger pathological cascades, including chronic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, or aberrant cellular proliferation, ultimately contributing to diseases such as cancer. Next, the discussion will focus on how brain-body crosstalk maintains organismal homeostasis under tumor conditions, and how this process impacts cancer hallmarks and the TME during the maintenance of homeostasis.

Brain-body crosstalk: participating in the battle between tumors and the organism

"Brain-body crosstalk dynamically regulates the TME through the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, influencing biological features of tumorigenesis, metastasis, and therapy resistance (e.g., angiogenesis, immune evasion). Under tumor conditions, interoceptive homeostasis becomes dysregulated. Tumors exploit brain-body crosstalk to create a macroenvironment conducive to their survival, while the host organism attempts to counteract tumor progression through reciprocal neurobiological adaptations. This dynamic interplay establishes a complex macroenvironment characterized by reciprocal interactions between tumors and multiple organ systems. Cancer complexity spans multiple dimensions, such as tumor initiation and promotion, TME and immune macroenvironment, aging, metabolic states, cancer cachexia, circadian rhythms, and microbiome [1]. These factors collectively demonstrate that cancer is not merely a localized collection of genetic mutations but a dynamic, systemic disease shaped by and reciprocally influencing whole-body physiology. Investigating these processes through a neurobiological lens, particularly focusing on brain-body crosstalk, provides critical insights into tumor pathophysiology, revealing novel therapeutic targets (e.g., neuromodulation, chronotherapy) and redefining cancer as a disorder of systemic homeostasis. Next, we will discuss the important role of brain-body crosstalk in the battle between tumors and the organism.

Brain-body crosstalk: reestablishing tumor homeostasis

Tumors hijack brain-body crosstalk, enhance tumor characteristics, reprogram TME and even impact the entire organism's rhythms to establish a homeostasis conducive to its survival and proliferation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Brain-body crosstalk drives TME reprogramming and cancer hallmark. In physiological states, systematic homeostasis is governed by the regulation of interoception, nociception, neuroception, endocriception, metaboception, and immunoception. Whereas neoplastic entities subvert this paradigm through hijacking brain-body crosstalk. This oncological coup manifests as: enhancing tumor characteristics, reprogramming of the TME, and remodeling of systemic biorhythmic networks, culminating in the establishment of a macroenvironment conducive to its survival and proliferation. TME, tumor microenvironment. This figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/)

Enhancing cancer hallmarked abilities

Emerging research highlights 14 hallmark features of cancer [38]. The interplay between the nervous system and tumor evolution at cellular/molecular levels may drive hallmark acquisition [14]. For instance, in subsequent discussions we will elucidate how brain-body interactions under neoplastic conditions facilitate the acquisition of the following tumor hallmarks: proliferative signaling, evasion of cell death, invasion and metastasis, and tumor-promoting inflammation. Investigating the extent to which brain-body crosstalk contributes to the acquisition of these cancer hallmarks represents a critical research frontier.

Proliferative signaling

Tumor development and growth depend on the dynamic equilibrium within the microenvironment of a balance between pro-tumorigenic factors (e.g., growth promotion, angiogenesis, cell survival) and tumor-suppressive signals (e.g., proliferation inhibition, apoptosis induction) [39]. The brain promotes proliferative signaling through neural pathways.

In brain tumors, sensory experiences can drive tumorigenesis and progression. For example, photostimulation activates retinal ganglion cell neurons, triggering optic nerve activity that enhances shedding of neuroligin-3. This process regulates the initiation, growth, and maintenance of low-grade gliomas (LGGs) by fostering neuron-glioma synaptic connectivity [40]. In addition, odorant stimulation activates olfactory receptor neurons, which signal to mitral/tufted cells in the olfactory bulb. These neurons secrete insulin-like growth factor-1 in an experience and activity-dependent manner, promoting the initiation and growth of high-grade gliomas in murine models [41]. These studies demonstrate that sensory stimuli can modulate tumor progression within their respective neural circuits. Electrochemical interplay extends beyond primary brain tumors. A study found that breast cancer brain metastases co-opt astrocyte-like signaling in pseudo-tripartite synapses, activating glutamatergic NMDA receptors on metastatic cells to enhance growth [42]. In addition, gliomas increase neuronal excitability, creating a feedforward loop. Hyperexcitable neurons release more glutamate and growth factors, further fueling tumor progression [25, 43, 44].

The interaction between the nervous system and cancers outside the CNS can also promote the transmission of proliferative signals. In peripheral solid tumors, the TME is infiltrated by autonomic and sensory nerve fibers, which interact with stromal, immune, and neoplastic components to drive proliferative [9]. For example, in murine breast cancer models, corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the central medial amygdala project to peripheral tumors, activating intratumoral sympathetic nerves to drive proliferation [8]. In murine pancreatitis models, capsaicin-induced sensory neuron ablation eliminated central neuroinflammation and suppressed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) initiation/progression, demonstrating how peripheral inflammatory signals are relayed to the CNS via afferent nerves [45]. In addition, the role of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems in pancreatic cancer has been demonstrated. Stress-induced catecholamines (e.g., NE from sympathetic nerves or adrenal glands) promote PDAC progression via β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) signaling, enhancing tumor cell proliferation [46–48]. Parasympathetic nerves activate the WNT signaling pathway in gastrointestinal cancer cells through cholinergic signaling, thereby driving the proliferation and growth of gastrointestinal cancers [49].

Cell death

The sympathetic nerves infiltrating the TME enable tumor cells to resist cell death. In xenograft models, both sympathetic denervation of the prostate and genetic knockout of the Adrb2 and Adrb3 genes encoding β2- and β3-adrenergic receptors significantly suppressed prostate cancer progression [26]. Genetic knockout studies in mice targeting Adrb2, Adrb3, or both genes revealed that loss of a single β-AR delayed xenograft tumor development, while combined deficiency of β2- and β3-adrenergic receptors profoundly inhibited tumor colonization. Increased numbers of apoptotic epithelial cells were observed in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia regions of sympathectomized mice [26], indicating that sympathetic innervation of the prostate may promote tumor expansion by facilitating cancer cells to evade programmed cell death.

Invasion and metastasis

Tumor innervation is closely related to poor prognosis in many cancer patients, and multiple studies suggest that tumor innervation may be involved in the regulation of the process of invasion and metastasis [50, 51]. In animal models, cholinergic agonists promote the proliferation of prostate cancer cells and accelerate their metastatic spread to pelvic draining lymph nodes, while cholinergic antagonists inhibit lymph node metastasis [26]. Furthermore, pharmacological interventions or genetic approaches blocking the muscarinic signaling pathway in the prostate tumor microenvironment significantly suppress tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and distant metastasis [52]. In addition, studies have found that compared with low-metastatic mouse breast tumors, high-metastatic tumor models exhibit a more significant phenomenon of neural innervation. This enhanced effect of neural infiltration is attributed to the axon guidance molecule SLIT2 specifically expressed in the tumor vascular system [53]. Further mechanism analysis reveals that breast cancer cells can activate the spontaneous calcium signal activity of sensory neurons and induce the release of the neuropeptide substance P (SP). Neuron-derived SP can significantly promote the growth, invasion and metastasis of breast tumors [53]. The bidirectional interaction between the brain-body crosstalk and tumor metastasis involves a mechanism known as perineural invasion (PNI), which is particularly prominent in PDAC and prostate cancer [54–57]. This phenomenon manifests as cancer cells infiltrating adjacent tissues along nerve pathways. Recent studies reveal that the mutual crosstalk between neural innervation and cancer cells may actively drive PNI progression. For instance, PDAC cells utilize paracrine signaling to induce the c-Jun/AP-1 transcriptional network, reprogramming neighboring Schwann cells into a"tumor-activated"state [58]. This reprogramming exhibits dual effects: Firstly, activated Schwann cells form microtracks ("tracks") that envelop cancer cells, facilitating their migration along nerve pathways remodeled by PDAC cells. Secondly, these tumor-activated Schwann cells secrete the chemokine CCL2, recruiting inflammatory monocytes that differentiate into macrophages expressing the extracellular protease cathepsin B. Together, these components synergistically promote PNI progression [59]. These functional studies in PDAC highlight the critical role of the nervous system in driving clinically significant invasive phenotypes.

Beyond peripheral nervous system tumors, brain-body crosstalk plays a critical role in the metastasis and invasion of central nervous system tumors. Research indicates that α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPA receptor)-mediated synaptic signaling inputs significantly enhance the invasive capacity of glioma cell subpopulations at the tumor periphery. This pro-invasive effect relies on calcium signaling pathways activated by synaptic communication, which can be blocked through calcium chelators or inhibition of cAMP response element-binding protein activity [60]. Real-time in vivo imaging techniques reveal that some invasive tumor cells gradually transition into a quiescent proliferative phenotype, while others persistently migrate to distal brain regions, collectively driving the expansion of the tumor's invasive range within the brain [60].

Tumor-promoting inflammation

Tumor-promoting inflammation represents a distinct pathological state characterized by persistent immuno-inflammatory responses. At its core, this chronic inflammatory process drives tumor initiation, invasion and metastasis through dynamic modulation of immune equilibrium, cellular signaling networks and metabolic reprogramming within the tumor microenvironment. Mechanistically, sustained inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, CCL5) activate oncogenic signaling pathways including NF-κB and STAT3, thereby fueling malignant processes encompassing tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis and immune evasion [61, 62]. Brain-body crosstalk orchestrates tumor-promoting inflammation through neuro-immune-tumor circuits. For example, in neurofibromatosis type 1-associated LGGs, studies have revealed that CCL5 secreted by microglia and bone marrow-derived myeloid cells promotes tumor growth. The secretion of CCL5 by these cells depends on paracrine signals from tumor-infiltrating CD8 + T lymphocytes. Consequently, CD8 + T cells form the foundation of a unique pro-tumor inflammatory microenvironment, which mediates three critical hallmarks of cancer: sustained proliferative signaling, resistance to cell death, and immune evasion [63].

The crosstalk between the brain and body plays a significant role in the formation of cancer hallmarks. With increasing reports of tumor mechanisms, future neural-tumor interactions may be viewed as another cancer hallmark for tumorigenesis.

Reprograming TME

Tumor initiation and progression are governed by the dynamic equilibrium between pro-growth factors (e.g., angiogenesis induction, cell survival) and anti-proliferative signals (e.g., apoptosis promotion) in TME [38]. Tumors actively subvert cellular activities within their local microenvironment to evade immune destruction and fulfill their metabolic demands for growth, proliferation, and metastasis. In reshaping the TME, tumors corrupt nearly all signals detectable by sensory/vagal nerves, including cytokines [64], metabolites [65], hormones[66], hypoxia [67] and tissue architecture [68]. Previous research in our laboratory specialized the tumor microenvironment into six typical microenvironments: hypoxic niche, immune microenvironment, metabolism microenvironment, acidic niche, innervated niche and mechanical microenvironment. However, our understanding of how specific TME-derived signals activate sensory/vagal nerves, how these signals propagate to the brain, and how such neural inputs interact with circulating humoral factors remains poorly understood. Next, we will discuss the effects of brain-body crosstalk on different dimensions of the TME.

Hypoxic niche

The hypoxic tumor microenvironment and brain-body crosstalk are closely interconnected, primarily mediated through hypoxia-induced molecular mechanisms and neural signaling pathways that regulate tumor progression. Rapid tumor growth leads to abnormal vasculature, creating hypoxic regions (oxygen partial pressure < 1%). Hypoxia activates the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) pathway, promoting angiogenesis (via vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF]), metabolic reprogramming (Warburg effect), and immune suppression, thereby enhancing tumor aggressiveness [69]. There exists bidirectional regulation between hypoxia and neural signaling: Hypoxia facilitates neural infiltration by upregulating molecules like VEGF and Slit2 through HIF-1α, promoting axon guidance and tumor innervation. Conversely, neural signals exacerbate hypoxia, as NE released by sympathetic nerves activates HIF-1α via β-adrenergic receptors, forming a positive feedback loop [70]. Under hypoxic conditions, tumors influence brain function through brain-body interactions. Hypoxia-induced factors (e.g., hepatocyte growth factor, IL-6) promote neuroinflammation and alter blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, potentially facilitating brain metastasis or cognitive impairment [71]. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment and neural signals form a dynamic interaction network through HIF pathways, jointly driving tumor invasion, immune evasion and distant metastasis. Future research should focus on elucidating specific molecular mechanisms of the neuro-hypoxia axis and developing combined therapeutic interventions [72].

Immune microenvironment

A bidirectional regulatory network exists between the immune and nervous systems [73–75]. Neuro-effector molecules and immune mediators participate in this interaction, which aims to maintain tissue homeostasis and minimize or prevent pathological conditions [76]. When the brain detects inflammatory deviations from physiological set points via vagal afferent signaling, brainstem neural networks generate coordinated efferent corrective signals propagated through the vagus nerve, other autonomic pathways and neuroendocrine routes [76]. The brain modulates immunity via brainstem neurons and circuits. Studies reveal that cytokines produced during tissue inflammation initiate afferent reflex arcs to balance pro- and anti-inflammatory responses. Ablation of vagal afferent fibers projecting to the nucleus tractus solitaries (NTS) results in uncontrolled inflammation, whereas experimental activation of specific vagal fibers suppresses inflammation and enhances anti-inflammatory responses. These findings confirm that NTS neurons play a pivotal role in establishing the inflammatory set point required for immune homeostasis [4]. This neuroimmune reflex architecture enables dynamic, context-dependent regulation of inflammation, positioning the brainstem as a critical hub for integrating neural and immune signals to preserve systemic equilibrium.

The interplay among immune cells, tumor cells, and neurons profoundly influences tumor progression [77, 78]. Autonomic neural signals regulate the tumor immune microenvironment. Norepinephrine primarily mediates immunomodulatory functions via the β2-adrenergic receptor, which is widely expressed by immune cells. Sympathetic nerve-released norepinephrine remodels tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) functions by inducing immunosuppressive signals (e.g., IL-10, arginase 1 [ARG1]) while suppressing proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-12 [79]. Norepinephrine upregulates immunosuppressive molecules like IL-10 and programmed death-ligand 1 [80, 81], enhances the immunosuppressive activity of regulatory T cells by elevating IL-10 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 levels [82].

Norepinephrine impairs natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity by reducing perforin and granzyme production [83]. Preclinical studies further confirm that norepinephrine accelerates tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting CD8 + T and NK cell cytotoxicity while promoting macrophage infiltration and ARG1 expression [83, 84]. Acetylcholine, released by parasympathetic nerves, mediates diverse immunomodulatory effects through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors broadly expressed on immune cells [85]. Activation of nAChRs suppresses proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNFα, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6) [86, 87], promotes IL-10 secretion [88], and dampens NK cell cytotoxicity by inhibiting granzyme and IFN-γ production [89, 90].

While autonomic neural signals regulate the tumor immune microenvironment, tumor cells actively exploit neural mechanisms to enhance survival. For example,

murine PDAC secrete trigger sympathetic nerve fiber ingrowth into the microenvironment, facilitating immune evasion [91]. Human pancreatic, colorectal, and prostate cancer cells release BDNF precursors to recruit autonomic innervation, accelerating disease progression [92].

Moreover, emerging research in cancer neuroscience has revealed that peripheral tumors may activate specific neurocircuits in brain regions such as the hypothalamus or brainstem, thereby modulating efferent autonomic neural signals. For example, murine pancreatic ductal or colorectal adenocarcinomas activate catecholaminergic neurons in the brainstem’s ventrolateral medulla (a key hub for sympathetic signaling), suppressing CD8 + T cells to promote tumor growth [93]. Murine lung carcinoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma, fibrosarcoma, or melanoma activates hypothalamic neurons, driving pituitary release of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) into circulation. This tumor-induced α-MSH promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) generation in the bone marrow, suppressing antitumor immunity [94]. This adaptive mimicry highlights tumors’ capacity to co-opt neural pathways, fostering immunosuppressive microenvironments conducive to survival and metastasis. These findings underscore the nervous system’s dual role as both a regulator and target in cancer biology, revealing novel therapeutic opportunities to disrupt neuro-immune-tumor triads.

Metabolism microenvironment

Tumor cells adapt to hypoxic and nutrient-deprived microenvironments by reprogramming metabolic pathways (e.g., glycolysis, glutaminolysis), while influencing immune cell and stromal cell functions through the release of metabolites such as lactate and ketone bodies [95–99]. Research has uncovered neuro-metabolic disruption mechanisms within the context of brain-tumor interactions. For instance, in oral squamous cell carcinoma, nociceptors secrete calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which promotes tumor growth by reprogramming tumor cell metabolism. This effect is potentially mediated through the induction of cytoprotective autophagy under the low-glucose microenvironment of the oral cavity, enhancing tumor survival [100]. Additionally, breast tumors alter the activity of orexigenic neurons in the lateral hypothalamus, leading to systemic metabolic abnormalities [101]. This finding underscores the pivotal role of central neuromodulators in driving metabolic perturbations caused by peripheral tumors [102]. Together, these studies highlight how tumors exploit neural-metabolic axes via peripheral nociceptive signaling or central appetite-regulating networks to hijack host physiology, expanding our understanding of brain-body crosstalk in cancer-associated metabolic adaptation.

Acidic niche

The interplay between brain-body interactions and the acidic tumor microenvironment involves complex mechanisms encompassing neural regulation, metabolic reprogramming, immune suppression, and tumor progression. The formation of the acidic tumor microenvironment is associated with the Warburg effect, lactate accumulation, and HIF-1α [65, 103]. A recent study has shown that chronic mental stress can increase the levels of serum and tumor epinephrine, thereby activating lactate dehydrogenase A-mediated glycolysis. The resulting acidic microenvironment rich in lactic acid enhances the occurrence of breast cancer [104]. More research is needed in the future to explore whether the nervous system can regulate the acidic microenvironment of tumors, especially whether chronic stress can promote tumor glycolysis and acidification by releasing cortisol through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Brain-body crosstalk may modulate tumor microenvironment acidification via neural signaling and metabolic regulation, while the acidic microenvironment reciprocally accelerates tumor progression and neural invasion. Future research should focus on elucidating the neuro-metabolic-immune network interactions to develop combinatorial therapeutic strategies.

Innervated niche

The interplay between the brain and TME operates through direct neural regulation and remote signaling mediated by neurotransmitters and metabolites, shaping tumor progression and systemic adaptations [105–107]. Developing breast and prostate adenocarcinomas recruit doublecortin-expressing neural progenitor cells from the subventricular zone (a neurogenic niche in the brain) [108]. These progenitors migrate through locally permeabilized BBB into circulation, home to tumors, and differentiate into adrenergic neurons that drive tumor progression [109, 110]. Similarly, lung adenocarcinomas are infiltrated by doublecortin neural cells exhibiting adrenergic properties linked to tumor progression and chemoresistance [111]. In addition to peripheral tumors, neurotransmitters and metabolites released through brain-body interactions also regulate the brain tumor microenvironment. Similar to the synapses formed between neurons and oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the healthy brain, neuron-glioma synaptic interactions are mediated by calcium-permeable AMPA receptors [25, 112]. Whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiological studies in glioma cells reveal that a subset (~ 5–10%) of tumor cells within specific regions exhibit glutamatergic, AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic activity [112]. A preclinical model found that Pharmacological inhibition of glioma AMPA receptors or disruption of neuron-glioma gap junctions significantly impedes tumor growth, and enhancing AMPA receptor signaling (e.g., via glutamate reuptake inhibitors) accelerates glioma invasion and angiogenesis [112]. This mechanism recapitulates the adaptive plasticity observed in healthy synapses, underscoring that neuron-glioma interactions can be reinforced through activity-dependent signaling pathways [113]. Targeting these neural mechanisms such as blocking β-adrenergic signaling or intercepting neurotrophic factor activity may disrupt tumor-brain crosstalk, offering novel strategies to combat cancer progression and systemic comorbidities [114–116].

Mechanical microenvironment

The bidirectional regulatory relationship between brain-body crosstalk (i.e., the interplay between the nervous system and systemic bodily systems) and the tumor mechanical microenvironment manifests in two key aspects: 1) neural regulation of mechanical signals within the tumor microenvironment, and 2) biomechanical modulation of neuro-tumor crosstalk [68, 117]. The tumor mechanical microenvironment, comprising ECM, interstitial fluid pressure, and mechanical stresses (e.g., compression, shear forces), directly influences tumor cell behavior through its stiffness and mechanical properties [118]. ECM stiffening activates pro-oncogenic pathways (e.g., integrin-FAK signaling) to upregulate YAP/TAZ expression, promoting tumor invasion and metastasis [119, 120]. The nervous system modulates the tumor mechanical microenvironment through neurotransmitters, hormones, and immune regulation. Sympathetic activation (e.g., under stress) releases NE, which enhances ECM remodeling via β-adrenergic receptors, increasing matrix stiffness (e.g., collagen deposition) and tumor aggressiveness. Conversely, parasympathetic nerves may inhibit matrix metalloproteinases through acetylcholine (ACh), reducing ECM degradation and indirectly altering mechanical properties [26, 70]. Mechanistically, tumor mechanical properties regulate neural innervation and neurotransmitter release via mechanotransduction. ECM stiffening or elevated local pressure activates mechanosensitive ion channels (e.g., Piezo1) in sensory nerve terminals, transmitting pain signals to the CNS and potentially triggering systemic inflammation [121, 122]. Future investigations should employ single-cell sequencing, organoid models and in vivo mechano-imaging to dissect its molecular architecture and therapeutic implications.

Disrupting circadian rhythms

Circadian rhythms, also known as the biological clock, are endogenous, evolutionarily conserved physiological processes that temporally coordinate external environmental changes with internal physiological functions [123–125]. Circadian disruption can promote tumor growth and progression by altering cancer cell biology [126, 127]. Many cancers disrupt circadian rhythms [128, 129]. For example, hepatocellular carcinoma perturbs the circadian system at the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) level, involving alterations in SCN neuropeptides, neuronal activity, Bmal1 expression, glial activation, and oxidative stress [130]. Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation via NE and/or epinephrine release is a key regulator of circadian timing [131]. Furthermore, the brain dynamically modulates tumor metastasis through circadian-dependent neural and humoral signaling. Studies reveal that circadian fluctuations in hormones such as testosterone, insulin, and melatonin significantly influence the dynamics of circulating tumor cell (CTC) shedding from primary tumors [132]. In both mice and humans, CTC shedding peaks during rest phases (e.g., nighttime in nocturnal mice or sleep in humans), highlighting circadian regulation of metastatic spread [132]. Understanding circadian-tumor interactions offers novel strategies to optimize chronotherapy (timed treatment delivery) and mitigate cancer-related circadian disruptions, potentially improving therapeutic outcomes and patient quality of life [133].

Brain-body crosstalk facilitates tumor initiation and progression by modulating cancer hallmarks and the TME Investigating tumors through the lens of brain-body crosstalk offers novel insights into uncovering tumor mechanisms and advancing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Brain-body crosstalk: a powerful anti-tumor weapon for the organism

While tumors hijack brain-body crosstalk to establish a homeostasis conducive to their survival and proliferation [134], the host organism simultaneously counteracts tumors through brain-body crosstalk to preserve its own homeostasis from disruption. The crosstalk between the brain and body serves as a powerful weapon for the organism to combat tumors. The brain-body crosstalk is primarily manifested in combating tumors and regulating the body's homeostasis through axes such as the HPA, Hypothalamic-Sympathetic-Adrenal (HSA), etc. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Brain-body crosstalk is a powerful anti-tumor weapon for the organism. When a tumor hijacks brain-body crosstalk to establish a homeostasis conducive to its survival and proliferation, the host organism simultaneously combats the tumor through brain-body crosstalk to protect its own homeostasis from being disrupted. The crosstalk between the brain and the body is a powerful weapon anti-tumor weapon for the organism. Brain-body crosstalk is mainly manifested as combating tumors and regulating the homeostasis of the body through axes such as HPA and HSA, etc. A HPA/HPG-Tumor axis, upon detecting tumor-derived factors such as IL-6, the brain activates the HPA axis to secrete glucocorticoids, which suppress the NF-κB signaling pathway within tumors, thereby exerting antitumor effects. HPG-Tumor axis, upon detecting tumor-secreted factors such as IL-6, the brain downregulates estrogen ER and AR expression via the HPG axis, thereby exerting antitumor effects; B Neuro-Immune-Tumor Axis, Neural circuits coordinate systemic immune responses to execute multimodal antitumor strategies through neurotransmitter-mediated immunomodulation and neural activity-dependent checkpoint regulation., C Brain-Gut-Tumor Axis, the vagus nerve, functioning as the central conduit of the gut-brain axis, mediates antitumor effects via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, while gut microbial metabolites such as SCFAs exert direct oncosuppressive activity; D Neuro-Metabolic-Tumor Axis, upon detecting tumor-derived factors such as IL-6, the liver, gut, and pancreas secrete hormones including ghrelin that signal to the brain. This neural interface subsequently mobilizes the ANS and ACh-mediated pathways to execute multimodal antitumor actions; E HAS/SAM-Tumor axis, under tumor conditions, the HSA axis exerts antitumor effects through coordinated neuro-endocrine remodeling, mechanistically linked to elevated BDNF in the central nervous system and suppressed leptin signaling in adipose tissue. Under acute stress, activation of the SMA axis induces adrenaline release that exerts antitumor effects through β2-adrenergic receptor -mediated immune and metabolic reprogramming. F Neuro-Endocrine-Tumor Axis, the pituitary gland secretes GH to stimulate muscle synthesis, while skeletal muscle reciprocally releases myokines such as irisin that exhibit multimodal antitumor activity through endocrine-paracrine signaling networks. HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; HPG, hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; ER, estrogen receptor; AR, androgen receptor; HAS, hypothalamic-sympathetic-adrenal; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; ANS, autonomic nervous system; POMC, p-opiomelanocortin; NPY, neuropeptide Y; AgPR, agouti-related peptide; ACh, acetylcholine; GH, growth hormone; PRL, prolactin; SAM, sympathetic-adreno-medullary. This figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/)

HPA-tumor axis

HPA axis plays a role in antitumor effects through complex regulation of stress hormones on the tumor microenvironment, immune system, and tumor cell behavior. Under acute stress conditions, glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) released by the HPA axis can suppress the progress of tumor cells via glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of the NF-κB pathway [135]. This is associated with the HPA axis reducing the release of pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), thereby suppressing inflammation-driven tumor progression [136]. Furthermore, glucocorticoids released by the HPA axis may directly regulate tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis by binding to glucocorticoid receptors within tumor cells, thereby modulating the expression of apoptosis-related genes (e.g., Bcl-2, Bax) [137].

HPG-tumor axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal (HPG) Axis modulates tumor microenvironment and immune responses through direct and indirect regulation of sex hormone (estrogen/androgen) secretion. Research reveals that in breast cancer, the HPG axis inhibits estrogen receptor (ER) signaling via activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), thereby suppressing tumor cell proliferation [138]. In prostate cancer, GnRH analogs (e.g., leuprolide) downregulate androgen receptor signaling pathways to induce tumor cell apoptosis [139]. Furthermore, the HPG axis potentiates antitumor immunity, a study found estrogen enhances CD8 + T cell glycolytic capacity through ER-β signaling (augmenting IFN-γ secretion), which amplifies T cell-mediated antitumor activity [140].

HSA-tumor axis

There exists a complex regulatory relationship between brain-body crosstalk and the tumor metabolic microenvironment, which is intricately linked to the fine-tuned regulation by the hypothalamus and SNS [141]. The hypothalamic sympathoneural-adipocyte (HSA) axis links physical/social environments to the regulation of adipose phenotypes, thereby modulating multiple organ systems and ultimately influencing cancer progression. Activation of the HSA axis has been shown to suppress tumor development [142]. In both obese and non-obese animals, HSA axis activation induces significant white adipose tissue atrophy, potentially limiting the pool of functional stromal cells available for tumor recruitment [143]. Furthermore, HSA activation reduces cancer proliferation through sympathetic innervation of adipose tissue, leptin suppression, and induction of hypothalamic brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression. Notably, genetic activation of the HSA axis via adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated hypothalamic BDNF overexpression resolves hepatic steatosis and demonstrates potential protective effects against liver cancer in preclinical models, suggesting therapeutic promise for metabolic dysfunction-associated malignancies [143]. This integrative axis underscores the brain’s capacity to coordinate systemic metabolic and neural adaptations that counteract oncogenic processes.

SAM-tumor axis

The antitumor effects of the sympathetic-adreno-medullary (SAM) axis exhibit significant context dependency. Short-term stress-induced activation of the SAM axis can inhibit tumor cell proliferation and survival directly while mobilizing immune responses to exert antitumor effects, whereas chronic activation is more commonly associated with tumor promotion [9]. Here, we focus on its antitumor effects. Acute activation of the SAM axis directly suppresses tumor cell proliferation and survival. Studies demonstrate that epinephrine activates the β2-AR/cAMP/PKA pathway, inhibiting Cyclin D1 and upregulating p21, thereby blocking the G1/S phase transition in prostate cancer cells [9]. NE induces ROS generation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via β3-AR, activating BAX/BAK-dependent mitochondrial membrane permeability transition and apoptosis [144]. Short-term SAM axis activation enhances immune-mediated tumor killing. Epinephrine upregulates natural killer (NK) cell surface activating receptors (e.g., NKG2D) and promotes granzyme B release via β2-AR, amplifying tumor cell cytotoxicity [145]. SAM axis activation improves chemotherapy sensitivity. NE enhances cisplatin-induced DNA double-strand breaks in ovarian cancer cells by increasing ROS levels via β-AR signaling [146]. Research on the antitumor effects of the SAM axis remains in its early stages. Future studies should explore targeted interventions to modulate SAM axis activity for tumor suppression, emphasizing strategies that harness its acute immunostimulatory and pro-apoptotic effects while avoiding chronic activation-related protumorigenic outcomes.

Brain-gut-tumor axis

Current research on the role of the"brain-gut-tumor axis"in anti-tumor effects primarily focuses on the interactions among the gut microbiota, CNS, and tumor microenvironment. The gut microbiota influences systemic immune responses in the host through metabolites (such as short-chain fatty acids [SCFAs] and tryptophan metabolites) and immune-modulating molecules, particularly enhancing the activity of CD8 + T cells and natural NK cells, thereby improving the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors like PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [147]. The vagus nerve plays a critical role in the brain-gut-tumor axis by suppressing tumor-associated inflammation via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP), which reduces the release of pro-tumor cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 [148]. Studies demonstrate that vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) reduces tumor growth in colorectal cancer mouse models and its activation inhibits gut inflammation-related tumors through the α7 nicotinic ACh receptor [148]. Additionally, gut microbiota-derived metabolites exhibit direct anti-tumor effects. For instance, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs, e.g., butyrate) enhance anti-tumor immunity via epigenetic regulation (e.g., histone deacetylase inhibition) and directly induce tumor cell apoptosis [149]. The brain-gut-tumor axis exerts anti-tumor effects through multiple pathways, including immune modulation, neural signaling, metabolites, and stress responses. Future research should further unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying microbial-host interactions and explore therapeutic strategies targeting this axis, such as probiotics, VNS, or psychological interventions.

Neuro-immune-tumor axis

The neuro-immune-tumor axis is a cutting-edge field in cancer research, revealing complex interactions among the nervous system, immune system, and tumor microenvironment [150, 151]. The parasympathetic nervous system enhances anti-tumor immunity through neurotransmitter secretion. Studies have shown that parasympathetic activation releases ACh, which binds to the α7 nicotinic ACh receptor (α7nAChR) to promote anti-tumor immune responses, such as increasing CD8 + T cell infiltration and suppressing the pro-tumorigenic phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [152]. Additionally, studies have shown that electroacupuncture enhances anti-tumor immunity in mice with breast tumors by activating the vagus nerve to regulate inflammatory cytokines [153]. The neuro-immune-tumor axis influences anti-tumor immunity through multifaceted regulation of immune cell function, tumor microenvironment remodeling, and metabolic reprogramming. Targeting this axis with interventions such as β-blockers or neuromodulation holds promise as a novel direction for cancer immunotherapy.

Neuro-endocrine-tumor axis

The neuro-endocrine-tumor axis regulates tumor initiation, progression, and immune evasion through synergistic interactions between the nervous and endocrine systems. Its core mechanisms include neurotransmitter-hormone signaling and stress pathway modulation. Neurotransmitters and hormones exhibit direct anti-tumor effects. Studies have shown that Ach suppresses tumor cell proliferation via the α7 nicotinic α7nAChR and reduces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) in lung cancer [154]. In addition, as the largest secretory organ in the human body, muscles secrete irisin, which has anti-tumor effects [155]. The neuro-endocrine-tumor axis exerts a double-edged sword effect on tumor progression—either promoting or suppressing tumors depending on the microenvironmental context and intervention timing.

Neuro-metabolic-tumor axis

The neuro-metabolic-tumor axis influences tumor cell energy acquisition, proliferation, and immune evasion through neural regulation of metabolic pathways. Its core mechanisms include neurotransmitter-driven metabolic reprogramming, metabolite-neural signaling feedback, and metabolic-immune crosstalk. Neurotransmitters can regulate tumor metabolism, a study found that parasympathetic neurotransmitter acetylcholine suppresses tumor glutamine metabolism by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway via α7nAChR, thereby blocking nucleotide synthesis.

Metabolite can mediate neuro-tumor interaction, studies found that ketogenic diet and ketone bodies enhance the anti-cancer efficacy of PD-1 blockade [156]. Vagal nerve signaling modulates the levels of metabolic intermediates (e.g., succinate, lactate), thereby altering the energy metabolism patterns of tumor cells. Studies have revealed that VNS inhibits the activity of mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase, reduces hypoxia-induced succinate accumulation and consequently suppresses HIF-1α-mediated VEGF-driven angiogenesis and immunosuppression [157]. Additionally, metabolic reprogramming also contributes to anti-tumor effects, a study found leptin secreted by adipocytes promotes colorectal carcinoma migration via the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, highlighting leptin as a potential therapeutic target [158]. The neuro-metabolic-tumor axis bidirectionally modulates tumor progression through metabolic reprogramming and immune-metabolic interactions, with mechanisms highly dependent on microenvironmental context. Future studies should integrate metabolomics and single-cell neural tracing technologies to resolve spatial heterogeneity in intratumoral neuro-metabolic networks; while developing metabolic-neural combination therapies (e.g., lactate inhibitors combined with VNS).

Brain-body crosstalk addresses unresolved questions in tumor research

There are still many unresolved questions in cancer research and exploring from the perspective of brain-body crosstalk may offer some directions for addressing these issues. Clinical observations show that tumors can recur for years or even decades after primary tumor resection. This is largely attributed to cellular dormancy, where residual cancer cells enter a metabolically quiescent state due to ECM remodeling, tissue oxidative stress, and endoplasmic reticulum stress [159]. These dormant cells are typically resistant to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies, making them a major obstacle in cancer eradication [160]. Whether this dormancy is controlled by the brain is a question worth studying. For example, is dormancy dynamically controlled by the central nervous system (e.g., via the hypothalamus-autonomic axis)? Do stress hormones like NE reactivate dormant cells through β-AR signaling? Does the brain influence dormant cell energy sensing and reactivation by modulating systemic metabolism (e.g., insulin/leptin signaling)? Research in this field will unravel the molecular mechanisms of brain-dormant cell interactions, offering novel therapeutic targets to prevent tumor recurrence. A critical question arises after primary tumor resection or treatment: do aberrantly activated brain circuits revert to a"pre-cancer"state? If so, how long does this recovery take, and what factors influence the process? In breast cancer, fatigue, and sleep disturbances may persist long after tumor removal and cessation of therapy [161]. However, the mechanisms underlying these sustained neural alterations remain unknown. Future studies leveraging animal models of cancer survivorship will be invaluable for addressing these questions, offering insights into neuroplasticity, stress axis recalibration, and the long-term interplay between residual tumor biology and CNS function [162].

There exists a sophisticated bidirectional interplay between tumors and the brain (and the systemic nervous system). The nervous system not only regulates tumor growth, metastasis, and drug resistance, but tumors themselves also influence brain function and systemic neural activity through multiple pathways. Brain-body crosstalk in the tumor state reveals that cancer is not merely a localized disease but a systemic disorder. Targeting this brain-body crosstalk offers novel therapeutic avenues for cancer treatment.

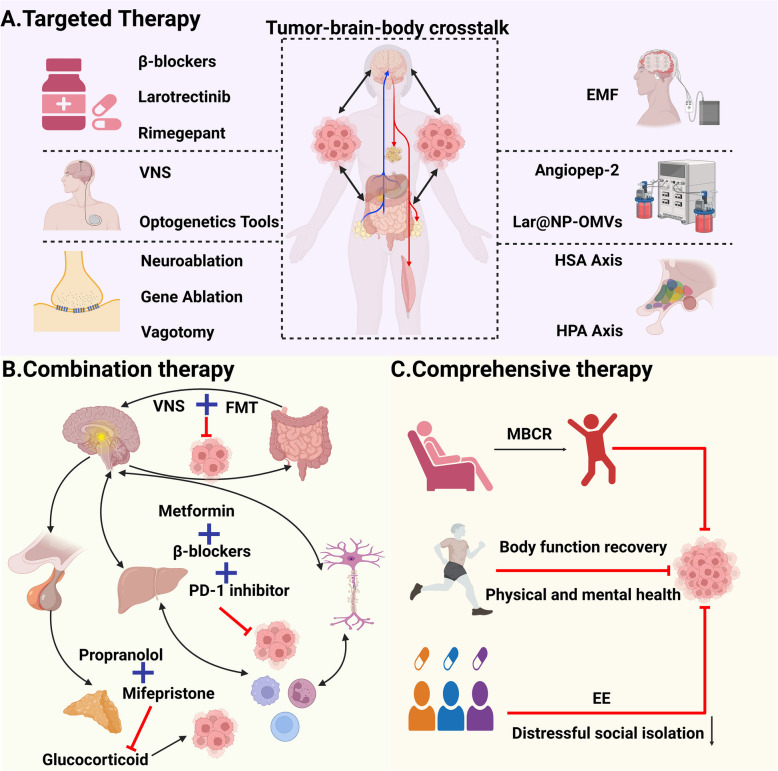

Brain-body crosstalk: novel anti-tumor strategies

Cancer neuroscience is a rapidly advancing discipline marked by emerging and exciting discoveries that hold potential to influence or even fundamentally transform cancer therapeutics [163–165]. Within the framework of brain-body crosstalk, targeting bidirectional neuro-tumor crosstalk may slow tumor growth or even reverse it while preserving or restoring quality of life and neural function. Recent studies highlight the clinical relevance of early histological documentation of intratumoral nerve fibers, demonstrating that increased innervation correlates with poorer patient prognosis [166, 167]. A growing body of preclinical and clinical research now shows that modulating the nervous system impacts the growth and spread of solid tumors in vivo as well as their response to therapy [27, 168–170]. Researchers are focusing on the tumor neural microenvironment, investigating how brain-body interactions become dysregulated in cancer and exploring strategies to control these pathways to block tumor progression (Table 1) (Fig. 5).

Table 1.

Tools for studying and manipulating neural innervation in brain-body-tumor crosstalk

| Tool | Mechanism of action | Application | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-edited mice | |||

| Advillin-Cre transgenic mouse | Peripheral sensory nerve-specific Cre recombinase (not expressed in CNS) | Enables specific deletion of genes in sensory nerves, or nerve depletion when crossed with DTA or DTR knock-in mice | [244, 245] |

| Ngf knock-in mouse | Ngf gene preceded by a stop codon inserted into the ROSA26 locus | When crossed to a Cre-expressing mouse strain (e.g. epithelial or stromal expressed Cre), increases NGF production and tissue innervation | [49, 246] |

| Nav1.8 Cre knock-in mouse | Express Cre recombinase from the endogenous sodium channel Scn10a locus | Enables selective deletion of genes in nociceptive nerves, or nociceptive neuron depletion when crossed with DTA or DTR knock-in mice | [247] |

| TrkAF592A or TrkBF616A knock-in mice | Trk knock-in alleles with modified kinase domains allowing pharmacological inhibition with nanomolar concentrations of the ligands 1NMPP1 or 1NaPP1 | Temporal pharmacological inhibition of nerve recruitment in the TME | [110, 248] |

| Trkb-CreERT2 knock-in mouse | Tamoxifen-inducible sensory nerve-specific Cre recombinase | Enables temporal control over gene expression specifically in sensory nerves or nerve depletion when crossed with DTA or DTR knock-in mice | [249] |

| Neurotoxin | |||

| 6-hydroxy dopamine (6OHDA) |

Polar monoamine mimetic that is taken up in the periphery by post-synaptic adrenergic nerves causing free radical destruction of nerve terminals |

When given neonatally, it induces permanent global sympathectomy (as well as off-target CNS effects), whereas in the adult, it only causes temporary peripheral sympathectomy (as it is unable to cross the BBB) | [26, 70, 250, 251] |

| RTX | A super agonist of sensory neuron-expressed calcium channel TRPV1, causing calciummediated neuronal death | When given neonatally, it induces permanent global sensory denervation, whereas in the adult, it causes temporary peripheral sensory denervation | [252, 253] |

| Capsaicin | TRPV1 agonist causing cytotoxicity at high doses | Less potent than RTX requiring repeated injections or incorporation into daily mouse feeds to induce lasting sensory denervation | [254] |

| Botulinum toxin |

Bacterium-derived protease that is taken up by endocytosis in the axonal terminal, and which selectively cleaves synaptic proteins preventing acetylcholine release |

When injected into a tissue of interest causes temporary denervation of cholinergic synapses | [255] |

| Novel neural-targeting nanocarrier Lar@NP-OMVs | Capable of modulating neuro-tumor crosstalk through both direct and indirect mechanisms | On the one hand, utilizes the neuron-binding peptide NP41 to precisely target neural structures in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and deliver the Trk inhibitor larotrectinib, blocking nerve growth and perineural invasion. On the other hand, leverages bacterial outer membrane vesicle (OMV) structures to polarize tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) toward the anti-tumor M1 phenotype, enhancing phagocytic activity and cytokine secretion. In murine pancreatic cancer models, combination therapy with Lar@NP-OMVs and gemcitabine significantly enhances chemotherapeutic efficacy, reducing tumor volume by 70% and extending median survival by 40% compared to gemcitabine alone | [256] |

| Surgical denervation | |||

| Mechanical neurectomy | Mechanical transection of axonal process, or removal of ganglionic cell body | Physical disruption of tissue innervation | [257–259] |

| Genetic vector | |||

| AAV | Replication inactivated viral vector that stably and predictably integrates desired engineered genetic information into neurons with minimal neurotoxicity | When injected peripherally in a tissue of interest, it travels in a retrograde manner to an innervating ganglion with the neuronal cell type selectivity determined by an engineered promoter (e.g. tyrosine hydroxylase for adrenergic specific expression) | [260, 261] |

| Neuro modulation | |||

| Optogenetic ion channels |

Light activated microbial ion channels with high fidelity spatial and temporal activation and inactivation |

When expressed in peripheral nerves in vivo, it enables precise spatiotemporal control of nerve firing and neurotransmitter release | [262] |

| Chemogeneticreceptors | Engineered G-protein coupled receptors activated by biologically inert drugs that modulate neuronal firing via altering intracellular levels of second messengers such as cAMP and calcium | When expressed in nerves in vivo, it enables temporal (and to a degree spatial) control of nerve firing and neurotransmitter release | [261, 263] |

| Long-acting ion channels (NaChBac) | Voltage-gated prokaryotic sodium ion channel with prolonged inactivation kinetics | When expressed in nerves in vivo, it enables increased nerve firing and neurotransmitter release | [260, 264] |

| EMF | Coordinate and regulate the neural activity in the peripheral nervous system and other tissues (including the neural activity in the stomach and heart) to synchronize them with the brain's rhythmic patterns | Inhibits the growth of multiple malignant cell lines while not affecting non-malignant cells | [201, 202] |

| Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) | Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway suppresses pro-inflammatory factors (such as IL-6, TNF-α) in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors | [265] | |

| Neural tracing | |||

| Single neuron—single-cell resolution (Trace-n-seq) | Retrograde axonal tracing from the tissue to their respective ganglia was performed, followed by single-cell isolation and transcriptomic analysis | Molecular characterization of neurons innervating the pancreas and PDAC at single-cell resolution | [266] |

Fig. 5.

Targeting brain-body crosstalk in cancer therapy. Emerging preclinical and clinical evidence has established that neuromodulation critically governs the proliferation, metastatic dissemination, and therapeutic vulnerability of solid tumors. At present, many tumor-targeted treatments start from the tumor-associated neural microenvironment, exploring how the brain-body crosstalk in cancer are dysregulated and exploring strategies to control these pathways to prevent tumor progression, with particular emphasis on: A targeted therapy, B combination therapy, and (C) comprehensive therapy. VNS, vagus nerve stimulation; EMF, electromagnetic field; HAS, hypothalamic-sympathetic-adrenal; HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; MBCR, mindfulness-based cancer recovery; EE, environmental enrichment. This figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/)

Targeted therapy

From the perspective of brain-body crosstalk in targeting tumors, several repurposed drugs have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy and circadian rhythm-based treatment regimens have shown clinical benefits. However, emerging therapeutic strategies including neuromodulation, neural blockade, neurometabolic interventions, bioelectric therapies, and intelligent delivery systems remain at the stage of animal experimentation or preclinical research.

Drug repurposing

Given that over 100 drugs in neurology, psychiatry, and internal medicine modulate neurotransmitters and other neural signaling components, repurposing one or several of these agents for specific tumor types represents a clinically expedient approach for rapid therapeutic translation [171]. Additionally, novel drugs targeting neuro-tumor signaling pathways are currently under development (Table 2).

Table 2.

Targeting brain-body-tumor crosstalk: current therapeutics and research landscape

| Tumor type | Therapy | Target | Phase | Actual or target accrual | Primary endpoint | Status | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27M spinal cord glioma | ONC201 | DRD2/DRD3 antagonist | Phase 2 | 84 | Progression-free survival | Terminated | 8 of 12 patients alive at < 12 months median follow-up | NCT02525692 |

| H3K27M diffuse midline glioma | ONC201 | DRD2/DRD3 antagonist | Phase 2 | 95 | Objective response rate | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT03295396 |

| Neuroendocrine tumours | ONC201 | DRD2/DRD3 antagonist | Phase 2 | 30 | Tumour response | Completed | 56% progressed | NCT03034200 |

| Paediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma | ONC201 | DRD2/DRD3 antagonist | Phase 1 | 134 | Recommended phase 2 dose | Terminated | Not reported | NCT03416530 |

| Endometrial cancer | ONC201 | DRD2/DRD3 antagonist | Phase 2 | 27 | Progression-free survival | Terminated | Not reported | NCT03485729 |

| Ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer | ONC201 | DRD2/DRD3 antagonist | Phase 2 | 62 | Dose-limiting toxicity, adverse events, objective response rate, progression-free survival | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT04055649 |

| Recurrent and rare CNS tumours | ONC206 | DRD2 antagonist | Phase 1 | 102 | Dose-limiting toxicity | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT04541082 |

| Paediatric high-grade glioma | INCB7839 | ADAM10/17 inhibitor | Phase 1 | 13 | Adverse events | Completed | Not reported | NCT04295759 |

| Glioblastoma | Talampanel | AMPAR regulator | Phase 2 | 72 | Overall survival | Completed | Improved overall survival compared with historical controls | |

| Glioblastoma | Memantine | NMDAR regulator | Phase 2 | 4 | Overall survival | Terminated | Not reported | NCT01260467 |

| Glioma | Talampanel | AMPAR inhibitor | Phase 2 | 30 | Progression-free survival | Terminated | Early termination due to futility | NCT00062504 |

| Ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer | Propranolol, chemotherapy | β-adrenergic antagonist | Phase 1 | 32 | Feasibility | Completed | Not reported | NCT01504126 |

| Ovarian cancer | Propranolol | β-adrenergic antagonist | Phase 1 | 24 | Feasibility | Completed | Improved quality of life | NCT01308944 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Propranolol etodolac | β-adrenergic antagonist/COX-2 Inhibitor | Phase 2 | 210 | Recurrence | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT03838029 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Bethanechol | Muscarinic agonist | Phase 1 | 17 | Change in Ki-67 | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT03572283 |

| Cancer pain | Tanezumab | Antibody against NGF | Phase 3 | 156 | Change in pain | Completed | Not reported | |

| Cancer pain | Resiniferatoxin | Capsaicin analogue | Phase 1 | 45 | Safety | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT00804154 |

| Melanoma | Propranolol, pembrolizumab | β-adrenergic antagonist | Phase 1 | 47 | Safety | Completed | No dose-limiting toxicity; objective response rate 78% | NCT03384836 |

| Bladder cancer | Propranolol, pembrolizumab | β-adrenergic antagonist | Phase 2 | 24 | Objective response rate | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT04848519 |

| Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms | Somatostatin Analogs | Somatostatin Analogs | unknown | 156 | Adverse events | Completed | Not reported | NCT02788565 |

| Prostate cancer | Carvedilol | β-adrenergic antagonist | Phase 2 | 22 | Changes in serum PSA | Ongoing | Not reported | NCT02944201 |

Beta-blockers can inhibit the adrenal gland's tumor-promoting effects [172]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that β-adrenergic blockade downregulates biomarkers of tumor cell invasion and reshapes the tumor immune response [173, 174]. For instance, propranolol has been shown to reduce breast cancer recurrence risk, correlating with increased immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment and decreased metastasis-related biomarkers [174]. Moreover, β-blocker-mediated modulation of sympathetic signaling is safe in breast cancer patients and demonstrates good tolerability when combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy [174]. Additionally, there are still some drugs currently undergoing preclinical research or animal studies. For example, tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA) inhibitors targeting the nerve growth factor (NGF) pathway (e.g., larotrectinib) can block the NGF/TrkA axis, thereby reducing neural invasion and pain in cancer [175, 176]. Preclinical research revealed that rimegepant, a CGRP-blocking migraine medication, reduces cancer cell autophagy and enhances the efficacy of anti-angiogenic agents and other nutrient-deprivation therapies [100]. Notably, certain antipsychotic agents have demonstrated antitumor efficacy through mechanisms involving brain-body crosstalk. A study on olanzapine revealed that this antipsychotic agent mitigates chronic stress-induced tumorigenesis and chemoresistance. Mechanistic investigations further demonstrated that olanzapine suppresses the medial prefrontal cortex-NE-CLOCK neuroendocrine axis, effectively reversing stress-associated anxiety-like behaviors and attenuating lung cancer stemness characteristics [177].

Circadian rhythm regulation

Current research explores circadian rhythm-based optimization strategies for cancer therapy [126, 178]. Chronotherapy is a treatment approach that leverages circadian rhythms to optimize therapeutic effects on tumors while minimizing adverse impacts on healthy tissues [179]. For example, timing chemotherapy and immunotherapy to specific circadian phases improves efficacy. A study found anti-PD-1 antibodies administered in the evening demonstrate enhanced efficacy due to minimal PD-1 expression and peak functional activity of CD8 + T cells at this time [180]. Similarly, evening infusion of CAR-T cells reduces tumor burden by over 50% in mice [180]. Chronomodulated administration of conventional drugs (e.g., platinum-based agents) also reduces toxicity to normal cells. In colorectal cancer patients, nighttime oxaliplatin delivery significantly decreases neurotoxicity and improves tolerability [180]. Light therapy and photoperiod adjustment can restore rhythmic expression of clock genes (e.g., Bmal1, Per). In liver cancer models, normalized light exposure suppresses metastasis and reverses oncogene expression [181]. Some scholars tried to use melatonin to interfere with the biological clock [182]. Research has demonstrated that melatonin exerts antitumor effects in various types of tumors, suggesting that melatonin interventions targeting circadian rhythms represent a potential anticancer strategy [183–185]. Recent research has focused on circadian clock-targeted therapies. Studies have revealed that REV-ERB agonists can remodel the tumor microenvironment, inhibit cell cycle progression, and induce apoptosis [186]. These advances highlight the need for personalized cancer therapies tailored to patients’ chronotypes (e.g.,"morning"or"evening"types).

Neuromodulation