ABSTRACT

Background

As highlighted by research on typically developing children, various biases exist when evaluating bilingual children's abilities. These biases can lead to inequitable assessment of language and cognitive abilities—potentially over‐ or underestimating bilinguals’ skills. Recent reviews on neurodivergent bilingual children alluded to the possibility that these biases are also present in clinical research.

Aims

This review examines bilingual neurodiversity research in children through the lens of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Specifically, it evaluates potential biases in recent studies to determine whether linguistic and cognitive abilities are assessed equitably, identify the types of linguistic and neurodiverse experiences represented in research, and examine the roles bilingual individuals play in research.

Methods

We conducted an abbreviated systematic review with a multi‐pronged search of databases and a manual search for quantitative studies on linguistic and cognitive abilities with bilingual neurodivergent children. The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist was adapted for risk of bias assessment. Data was extracted and analysed from 95 studies, including study methods, bilingualism‐related information (e.g., age of acquisition, language history tools, socioeconomic status), outcomes of interest (language, cognition), tasks (e.g., domain, name), and the main results or conclusions of each article.

Main Contribution

We found that equitable bilingual assessment of language and cognition was highly affected by the lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate tools. Most studies used case‐control designs, contrasting neurodivergent bilinguals with monolingual or typically developing peers, which promotes a deficit‐based monolingual‐centred view in bilingual neurodiversity research. We also identified persistent challenges in defining and measuring bilingualism that complicate cross‐comparison across studies and conditions. Research focus remained largely on developmental language disorder (DLD; n = 34) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD; n = 29) given their language symptomology, while acquired disorders are understudied. Additionally, there is a lack of community‐based research that could offer more inclusive methods by involving bilingual communities throughout the research process.

Conclusions

This review emphasizes the need to adopt equitable and inclusive research practices to better understand and support neurodivergent bilingual children. Future research should embrace a nuanced understanding of bilingualism and neurodiversity, prioritizing inclusive methodologies as well as holistic assessments using culturally and linguistically appropriate tools to avoid misdiagnoses and ensure fair clinical evaluations of language and cognition.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

What is already known on this subject

Prior research has demonstrated that neurotypical bilingual children are often compared to monolingual norms, which can introduce biases and result in mischaracterization of bilingual abilities. Monolingually normed assessments are inequitable for use with bilingual children.

What this paper adds to existing knowledge

This review examines biases in recent research on neurodivergent bilingual children, focusing on the assessment of cognitive and language abilities—skills also often evaluated by clinicians, including speech‐language pathologists.

What are the potential or actual clinical implications of this work?

This review integrates a structured EDI framework to contextualise research on neurodiversity for clinicians and researchers. It highlights the need to implement holistic and culturally appropriate assessment methods for all bilingual children that can lead to more equitable evaluations and help to better support tailored interventions and inclusive clinical and research practices.

Keywords: bilingualism, cognition, diversity, equity, inclusion, language, neurodivergent populations, review

1. Introduction

Childhood bilingualism offers sociocultural benefits—including multi/intercultural experience (Feliciano 2001; Fürst and Grin 2023; Golash‐Boza 2005), in addition to possible cognitive benefits (Yurtsever et al. 2023; cf. W. Bao et al. 2024b; Gunnerud et al. 2020; Lowe et al. 2021). Until recently, the predominant belief in healthcare and education has been that learning more than one language would burden children whose neurocognitive functioning was divergent from the societal ‘norm’. This unfounded belief led clinicians and educators to advise against bilingualism (del Hoyo Soriano et al. 2023). Unfortunately, one may still receive this advice, even though this concern has been proven largely unsupported (Guiberson 2013). Several reviews assessed the cognitive or language abilities of bilingual children across various neurodevelopmental conditions, with the findings supporting no adverse effects of bilingualism on children (Kay‐Raining Bird et al. 2016; Uljarević et al. 2016).

Our review takes a fresh look at the most recent studies in this domain. Instead of assessing the potential negative or positive effects of bilingualism on language and cognitive abilities in neurologically diverse children across studies, we evaluate to what degree these studies align with recent equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) perspectives.1 Beyond bilingualism, this review also engages with the concept of neurodiversity, which at its core recognizes an infinite variation in human neurocognitive functioning as a natural aspect of human diversity (Walker 2021). While neurodiversity describes variation at the population level, neurodivergent individuals have neurocognitive functioning that differs from neurotypicals or diverges from dominant societal norms, such as in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and developmental language disorder (DLD; Asasumasu 2015; Walker 2021). Understandings of neurodiversity have been largely shaped by the self‐advocacy of neurodivergent individuals and communities, with strong socio‐political dimensions within the broader neurodiversity movement and paradigm (Botha et al. 2024; Dwyer 2022). This paradigm asserts that differences in how our brains work are not inherently deficits but rather natural variations that enrich human diversity (Walker 2021). Relevant to the current review, it challenges traditional medical models that often interpret neurological differences through a deficit‐based framework, relying on diagnostic criteria and standardized testing that may not fully capture neurodivergent experiences (Chapman 2020; Dwyer 2022; Miranda‐Ojeda et al. 2025). However, existing research in areas like bilingualism and neurodevelopment remains grounded within the medical model, as it is reflected by the studies reviewed here. This review does not seek to endorse the medical model but rather engages with it to critically examine how neurocognitive differences are studied and understood in the context of bilingualism. In particular, this review integrates the principles of EDI to explore the diversity of neurological variations and linguistic experiences represented in the research. By examining EDI within this context, we aim to provide insights into how future research can develop equitable, inclusive study designs and practices that better reflect the experiences of bilingual individuals, including those with neurocognitive differences.

1.1. Previous Reviews of Neurodivergent Bilinguals

Bilingual development of individuals with a range of neurocognitive profiles, including both neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals, is an evolving area of study that offers the opportunity to examine the relationship between language and cognitive diversity. Previous research has mainly focused on reviewing the positive, neutral or negative impacts of bilingualism within singular named diagnoses or neurotypes. These include DLD—previously known as specific language impairment (SLI; Bonuck et al. 2022; Goldstein 2006; Kohnert and Medina 2009; Paradis 2010, 2016; Potapova and Pruitt‐Lord 2019); ASD (Beauchamp and MacLeod 2017; Conner et al. 2020; Drysdale et al. 2015; Lund et al. 2017; Prévost and Tuller 2021; Romero and Uddin 2021; Wang et al. 2018; Yu 2018; cf. Megari et al. 2024 for a review using a neurodiverse approach); hearing impairment (Alfano and Douglas 2018; Crowe and McLeod 2014); and preterm birth (Head et al. 2015).

A few reviews also compared bilinguals across a broader range of neurodivergence. Kay‐Raining Bird and colleagues examined how bilingual acquisition timing and exposure affected language abilities in children with DLD/SLI, ASD, and Down Syndrome (DS; Kay‐Raining Bird et al. 2016). Their findings reported simultaneous bilinguals (multilingual exposure before age three) with DLD had language abilities comparable to monolinguals with DLD. However, sequential bilinguals (multilingual exposure after age three) with DLD exhibited ‘deficits’ on standardized language tests and measures of morphosyntax in their second language, compared to their monolingual peers, which the authors attributed to issues of language dominance or reduced exposure. For children with ASD, no significant differences were found between bilinguals and monolinguals, except in expressive vocabulary. In children with DS, language abilities were similar among simultaneous bilinguals, sequential bilinguals, and monolinguals in the majority language.

Moreover, in a clinician‐oriented systematic review by Uljarević et al. (2016), findings were synthesised from studies evaluating the effects of multilingualism across various neurodevelopmental conditions as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fifth Edition (DSM‐5; American Psychiatric Association 2013). The review focused specifically on populations with ASD, intellectual disability, and communication disorders, as studies examining specific learning disorders, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and motor disorders were not identified. Their review found no evidence suggesting that bilingualism negatively impacts any of these conditions. In fact, bilingualism had a positive effect on communication and social functioning in children with ASD (Uljarević et al. 2016). In general, the results did not distinguish between types of bilingualism (simultaneous or sequential) due to incomplete information in the included studies. However, some findings indicated a slower recovery rate among simultaneous bilinguals who stutter and enhanced interpersonal skills among simultaneous bilinguals with ASD, as compared to sequential counterparts.

These reviews already highlight some points relevant to the goal of the current review. For instance, they note a lack of methodologically robust studies that adequately collect and report participant language information (Kay Raining‐Bird et al. 2012; Uljarević et al. 2016) and highlight issues in determining appropriate ‘control’ groups in comparative research designs (Uljarević et al. 2016), which may introduce biases in synthesis results. These and other potential biases in bilingualism research have been already noted in regard to studies that investigate language and cognition in typically developing paediatric populations—as synthesized in the next section.

1.2. Potential Biases in Bilingualism Research

Bilingualism research on typically developing children has largely adopted a language group approach, dichotomizing an experience as either ‘bilingual’ or ‘monolingual’ to provide a comparison (Rothman et al. 2023). While this approach can provide insights across different language environments and inform theoretical models and clinical practice, it also has notable issues. Comparing bilingual and monolingual groups can perpetuate a deficit‐oriented, monolingual‐centric perspective, where monolingualism is seen as the norm and bilingualism as the exception (Grosjean 1998). This approach erroneously assumes that bilinguals operate as if they are two monolinguals in one brain (Grosjean 1998).

A monolingual bias may lead to a misrepresentation of bilingual individuals’ abilities, as biases in the tools and methodologies used in evaluating language history, collecting data and in analysis also pose challenges (De Houwer 2023). Additionally, studies often lack sufficient detail about bilingual participants' backgrounds, complicating the interpretation of results and overlooking the sociocultural context. Comparisons are frequently made using monolingual norm‐referenced tests administered in a single language, which can underestimate bilingual abilities since these tests have not been validated for accuracy, validity, and reliability with a diverse, bilingual normative sample (Freeman and Schroeder 2022). For instance, vocabulary size as measured by the widely used and primarily monolingual normed Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT; Dunn and Dunn 2007) has repeatedly produced lower receptive vocabulary scores among bilingual as compared to monolingual participants, even when matching socioeconomic status (SES; Ben‐Zeev 1977; Umbel et al. 1992). In this vein, vocabulary size has often been mistakenly believed to be delayed in bilinguals (Fennell and Lew‐Williams 2017; Thordardottir 2011). In single‐language vocabulary knowledge, a larger vocabulary is reported in monolinguals, as compared to bilingual children (Hoff et al. 2012; Poulin‐Dubois et al. 2013). However, considering total vocabulary across both languages, the opposite is true: bilinguals have a larger total vocabulary compared to monolinguals (De Houwer et al. 2014). This highlights that testing both languages of bilinguals (beyond vocabulary) to achieve a holistic view of the bilingual child's abilities can provide a fairer description of bilingual abilities. Rather than evaluating each language in isolation, as if the child were two separate monolinguals, a holistic assessment approach considers the interplay between both languages and recognizes that language skills are distributed across the bilingual's entire linguistic repertoire. This method aligns with current best practices, which advocate for assessments in both languages to capture a fuller scope of a bilingual child's language competence.

In addition to providing a holistic view of bilingual children's abilities, various other steps can be taken to overcome the deficit‐oriented view. Some efforts have been made in this direction within research focusing on typically developing children. For instance, one solution to the ‘categorical’ view towards bilingualism‐monolingualism can be to additionally include continuous variables in analyses. For instance, operationalization of language abilities or language history variables of interest may be evaluated continuously along a given range (e.g., language exposure) as well as categorically as bilingual or monolingual (e.g., W. Bao et al. 2024a; Kremin and Byers‐Heinlein 2021). Given the inconsistencies in how bilingualism factors are collected and reported, a more systematic approach to documenting and reporting language history could help address some of these discrepancies. Numerous language history questionnaires have been developed for developmental bilingual research, covering factors such as proficiency, exposure, and current and past use in each language (De Cat et al. 2023; DeAnda et al. 2016; Marian et al. 2007; Paradis et al. 2010). Bilingual individuals vary widely in their language experiences, and the use of a language history questionnaire helps to avoid the assumption that all bilinguals are alike. These tools enable the consistent and equitable measurement of key factors across all participants and provide metrics that are appropriate for continuous variable evaluation as previously outlined. These tools provide more information about the participants’ language background in studies, allowing research to account for the diversity across language experiences.

1.3. The Current Review

Previous reviews on neurodivergent bilinguals (Kay‐Raining Bird et al. 2016; Uljarević et al. 2016) highlight a critical issue: biases embedded in the research design and methodology for neurotypical bilinguals might also apply to research on neurodivergent bilingual children. For instance, the categorical contrastive approach seems to be a standard practice, where neurodivergent bilinguals are compared to a neurodivergent or even a neurotypical monolingual ‘norm’. This approach perpetuates the pathologization of bilingual development, where deviations from the norm are interpreted as delayed or disordered language. While the ‘difference’ versus ‘disorder’ approach attempts to overcome this bias in bilingual clinical practice, this approach has the potential to further reinforce this bias, as it suggests that bilinguals are different from a certain accepted norm based on monolingual abilities (Yu et al. 2021).

Furthermore, a holistic approach—evaluating all languages and accounting for and reporting relevant bilingualism factors—is just as crucial in neurodivergent populations as it is in neurotypical ones. From a clinical perspective, the diagnosis of DLD or other language‐related disorders is contingent on impairments presented in both bilingual's languages, as ‘disorders’ should manifest in all languages of the bilinguals (Bedore and Peña 2008; Kohnert 2010; Peña, Bedore, and Kester 2016). However, monolingual screening tools have shown poor diagnostic accuracy for bilingual children with DLD (Altman et al. 2022; Armon‐Lotem and Meir 2016), and screening tools are rarely available in the heritage (non‐English) language (X. Bao et al. 2024). The effects of the monolingual bias (e.g., use of inappropriate tools), coupled with assessment of a bilingual child in just one language, can result in misdiagnoses, with bilingual individuals often experiencing both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis of language disorders in a clinical context (Bedore and Peña 2008) and mischaracterization in a research context (Kutlu and Hayes‐Harb 2023).

In this review, we examine studies published since the two most recent reviews (Kay‐Raining Bird et al. 2016; Uljarević et al. 2016), with a particular focus on potential biases. To guide our evaluation, we adopt a research‐focused framework of equity, diversity and inclusion, particularly at the participant level of research (Canada Research Coordinating Committee 2021; cf. National Institutes of Health 2023). The framework's core principles are as follows: Equity is characterized by the removal of biases and systemic barriers to ensure fair and equal opportunities; Diversity encompasses a variety of unique dimensions, identities, and traits; and Inclusion is the practice of ensuring all are valued for their contributions and equitably supported. We employ this framework to answer the following research questions:

(i) Equity. Are bilinguals’ linguistic and cognitive abilities being equitably assessed?

(ii) Diversity. What types of linguistic and neurodiverse experiences are represented in research?

(iii) Inclusion. In what roles are bilingual individuals included in research?

2. Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

Quantitative articles with a focus on task‐based linguistic abilities or cognition, conducted with bilingual neurodivergent (BN) children and either (i) a monolingual neurodivergent (MN) comparator group or (ii) a bilingual typically developing (BTD) comparator group were included. Literacy‐related tasks (including reading and writing) were excluded, as our goal was to analyse effects of bilingualism on language and cognition separately, and in literacy tasks, language and cognitive functions greatly overlap. In addition, studies whose focus was to diagnosis disorders or validate an assessment tool to identify clinical markers were excluded, as these did not provide sufficient information regarding linguistic and cognitive outcomes. Children who were at risk or suspected of a condition—as opposed to diagnosed—were not included. Studies were cross‐referenced with two earlier mentioned reviews (Kay‐Raining Bird et al. 2016; Uljarević et al. 2016) and excluded if they were previously featured to provide an update to the literature. An additional exclusion criterion based on the resulting critical appraisal assessment is described in the corresponding section below.

2.2. Search Strategy

We employed an abbreviated systematic‐review method, using a multi‐pronged search through to March 2024. OVID Medline, Embase and APA PsycINFO databases was searched for peer‐reviewed English or French language articles and OSF Preprints (including associated repositories, Cogprints, Preprints.org, bioRxiv and PsyArXiv) and medRxiv for preprints on language and cognitive development in bilingual children (aged 0 to 17 inclusive) with atypical development. A manual ancestral search in Google Scholar was used with pre‐screened database articles. A grey literature search was conducted through a callout for unpublished manuscripts. To ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature, an institutional librarian assisted in refining the search strategy and these databases and helping to select these databases based on their strong representation of peer‐reviewed studies in bilingualism, language processes, cognition, and speech‐language pathology. Keywords used in the search strategy are included in the Supporting Information S1.

2.3. Data Collection

Single‐reviewer (KIL) screening and extraction were conducted, starting with title and abstract screening, full‐text screening, followed by data extraction. The screening and extraction process was facilitated in the specialized review software, Covidence. Publication data, study methods, bilingualism‐related information (e.g., age of acquisition, other language history tool used to measure bilingualism, SES measured), outcome of interest (language, cognition), task (e.g., domain, name), and main results/conclusions of each included article were extracted and summarized in Supporting Information S3. The synthesis of the data items relied on a combination of narrative and quantitative methods in order to answer the research questions.

2.4. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The Checklist for Quasi‐Experimental Studies from the Joanna Briggs Institute Appraisal Tools (Joanna Briggs Institute 2017) was adapted for appraising studies identified in the database and manual search for risk of bias. The appraisal team consisted of the authors (KIL, MM) and six undergraduate‐ and graduate‐level research assistants, who underwent a training session in conducting the appraisal in Covidence. Critical appraisals were first independently conducted by an assigned primary and secondary appraiser, with a third independent appraiser assigned to compare ratings, resolve disagreements through discussion and evaluation, and make the final consensus decision. A percentage score, derived from the total of the weighted question scores, was used to categorize studies into three quality tiers: Low (< 50%), Medium (51%–74%), and High (75%–100%). Only studies rated as medium or high quality were included to ensure that comparable and reliable quality of data contributed to the synthesis. The critical appraisal questions and assessments are available in the Supporting Information S2.

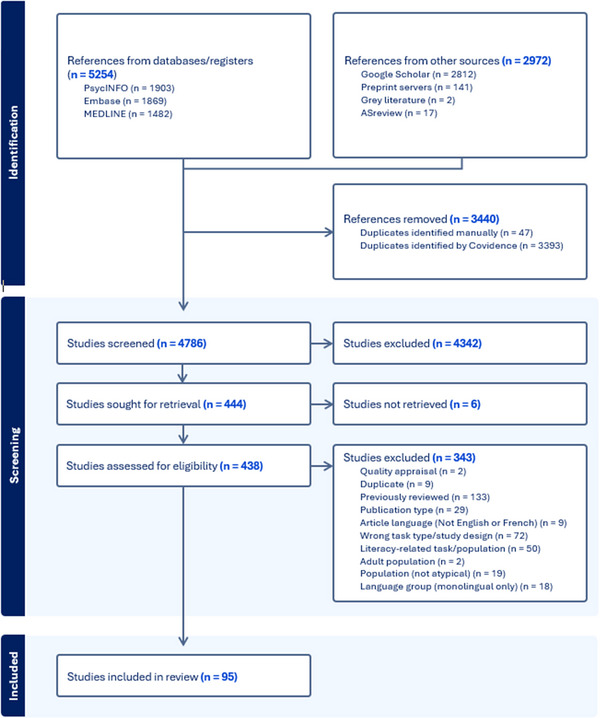

3. Results

Four hundred and thirty‐eight studies were assessed for eligibility following reference deduplication and initial title and abstract screening. Approximately 30% of studies assessed for eligibility had previously been reviewed in Kay Raining‐Bird and Uljarević’s syntheses and thus were excluded from this updated synthesis. An additional 48% was excluded as well. Common reasons for exclusion included tasks requiring participant literacy, population type (i.e., adult or not atypically developing) and language group (i.e., monolinguals only). Through the quality appraisal process, two studies were flagged as lower quality (percent score below 50%) and were excluded from the synthesis due to not meeting the minimum quality threshold required for inclusion (see quality appraisal table, Table S2). In particular, these studies were found lacking in key areas evaluating internal validity and comprehensiveness of reporting: insufficient sample description (e.g., presenting symptoms, stage/severity), failure to account for socio‐economic status, and inadequate assessment of bilingual language background (e.g., age of acquisition, bilingual type). Ultimately, our search yielded 95 studies identified for inclusion in the review (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) diagram flowchart indicating the processes of literature identification, screening and inclusion for studies included in the review.

A detailed description and a bibliography of included studies are available in the Supporting Information S3 and S4. Studies were published between 1996 and 2024, with the bulk from 2019 onwards. Just under half of studies focused on language (45/95, 47%) or a mixture of language and cognitive abilities (36/96, 38%), as opposed to cognition alone (14/95, 15%). Language domains varied, including speech perception and production, phonological development, vocabulary, syntax, language acquisition, code‐switching, social communication and narrative skills. Cognition domains evaluated include executive functioning, attention, processing speed, memory, behavioural outcomes and social cognition (e.g., theory of mind).

3.1. Equity: Are Bilinguals’ Linguistic and Cognitive Abilities Being Equitably Assessed?

3.1.1. Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Tools

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of study measurement approaches across various tool types categorized by linguistic and cultural adaptation. Standardized measures were frequently employed with both typically developing controls and neurodivergent bilingual groups (85/95, 89%). In contrast, experimental tasks, such as researcher‐designed assessments for language (e.g., picture naming) or cognition (e.g., Flanker task), were infrequently used independently (14/95, 15%), particularly in studies focusing on cognition. More often, however, both measurement approaches were used in combination (44/85, 52%). Nearly half of the studies (45%) used tools that were non‐linguistic or “accultural” (i.e., tasks with minimal linguistic demands). Other tools used included single‐language study tools (i.e., where a single study language was evaluated; 82/95, 86%), translated tools (i.e., tools translated for study use; 6/95, 6%), culturally adapted tools for additional languages tested (i.e., tools that underwent translation and cultural validation; 31/95, 33%) and bi/multilingual tools (i.e., tailored to the specific language pair or community; 7/95, 7%).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of reviewed studies based on tool types (categorized according to their linguistic and cultural adaptation) and measurement approach (experimental only, standardized only, or combined).

Note: Tool types are defined as: single language (tools designed and used for one language), nonlinguistic (no/minimal language involved), culturally adapted (modified for culture and language), bilingual (developed for two languages), translated (adapted for language only). Measurement approaches are: experimental only (researcher/informal tasks), standardized only (assessments/tests), combined (both methods).

For the measurement of language, standardized and/or normed language assessments such as the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF; Wiig et al. 2013) and PPVT (Dunn and Dunn 2007) were the most conducted, with cultural adaptations readily used for French (and Canadian French) and Spanish participants. Multilingually‐adapted tools such as those by the Language Impairment Testing in Multilingual Settings (LITMUS; Armon‐Lotem and Grohmann 2021) network—covering sentence repetition, narrative, nonword repetition and cross‐linguistic lexical tasks—were also commonly used. Translations were rarer, used to index vocabulary, narrative language and the development of language. Among bilingual assessments, the Bilingual English‐Spanish Assessment (BESA; Peña et al. 2018) and Bilingual English Spanish Assessment Middle Extension (BESA‐ME; Peña et al. 2010) for Spanish‐English bilinguals were frequently used; other tools include vocabulary tests such as the Receptive/Expressive One‐Word Picture Vocabulary Test‐Spanish Bilingual edition (Brownell 2000; Martin 2013). Experimental language tasks were also used to probe into children's language production (e.g., narrative production, story‐retell, sentence/nonword repetition, picture naming) and comprehension (e.g., morphosyntax, sentence comprehension) tasks.

For the measurement of cognition, standardized neuropsychological tests for multiple non‐linguistic and linguistic‐related cognitive domains (e.g., Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [KBIT; Kaufman and Kaufman 2004], Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children [WISC; Wechsler 2014], Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence [WASI; Wechsler 2011], Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence [WPPSI; Wechsler 2012], Bayley Scales of Infant Development [Bayley 2006], A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment [NEPSY; Korkman et al. 2007]) or more specifically for one cognitive domain such as short‐term memory (e.g., WISC digit span), executive function (e.g., Delis‐Kaplan Executive Function Scale [D‐KEFS; Delis et al. 2001], Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function [BRIEF; Gioia et al. 2015]), or more generally for nonverbal IQ (e.g., Test of Nonverbal Intelligence [TONI; Brown et al. 2010], Raven's Progressive Matrices [Raven et al. 1998], Leiter International Performance Scale [Roid et al. 2013]). These were frequently available and adapted to the different language pairs of the participants, or more rarely, translated when no available adaptations existed (e.g., Comprehensive Executive Function Inventory [CEFI; Naglieri and Goldstein 2013] – Arabic). Test batteries were often combined normed tests with experimental tasks (e.g., Attentional network task [ANT], Flanker, Simon, 2‐back, card sorting, continuous performance, first/second order theory of mind tasks). Bilingual tools for cognition were non‐existent; most studies used nonverbal or reduced verbal cognitive tasks.

Diagnosis‐specific measures were noted, especially in ASD, where there were more measurements of language/cognitive‐related autism traits (e.g., use of Children's Communication Checklist [CCC; Bishop 2003], Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule [ADOS; Lord et al. 2012], and Social Responsiveness Scale [SRS; Constantino and Gruber 2005]) and in the HI/CI users, where language intelligibility and speech perception tests were more commonly used.

3.1.2. Holistic Language Assessment

We defined holistic language assessment as an assessment approach that considers the bilingual's linguistic repertoire across both languages. Across 30 out of the total 95 studies reviewed, both languages of neurotypical and neurodivergent bilinguals’ were evaluated in study tasks, using validated bilingual assessments (n = 8), culturally adapted assessments (e.g., CELF‐Spanish; n = 19) or by translating tasks into the bilingual's language (n = 3). Another 14 studies evaluated only part of the study tasks in both languages and exclusively used culturally adapted measures. For studies employing informant‐reported measures of a child's language abilities, administering the test in another language would be neither necessary nor informative, as it would assess the informant's language skills rather than the child's abilities. In nearly half of studies (43/95), bilinguals, primarily those with heterogenous language pairs, for example, English‐Other, were only evaluated in one of their languages, which was often the societal/prestige language used by the researchers.

As a diagnosis of DLD precludes impairment in both languages, it is important to assess both languages in a language study. Among DLD studies evaluating language/cognitive abilities, 62% did not conduct all study tasks in both languages (only one language: 16/35; some tasks assessed in two languages: 6/35).

3.1.3. Assessment Informants

While most measures were directed at the child participant, other informants were also part of the study as a means of proxy for the child's abilities. These included parents, teachers and clinicians/researchers themselves. These were often concerning subjective judgements of a child's communication (e.g., CCC, ADOS, Student Oral Language Observation Matrix [SOLOM; Parker et al. 1985]) and behaviours/emotions (e.g., Behaviour Assessment System for Children [BASC; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2015], Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment [BITSEA; Briggs‐Gowan and Carter 2006], Child Behaviour Checklist [CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001], BRIEF, CEFI), using validated tools. In four studies, the authors exclusively consulted informant proxies, with no direct measures of the child.

3.2. Diversity: What Types of Linguistic and Neurodiverse Experiences Are Represented in Bilingualism Research?

3.2.1. Linguistic Diversity

The definition of who was considered bilingual varied study to study. Often defined a priori, certain studies operationalized it as one or multiple criteria that bilinguals recruited to their group were required to meet, including information such as expressive/receptive abilities as confirmed during the study visit, tested proficiency and information collected via parent report (e.g., environment/exposure with set cutoff, language history).

Age of acquisition, which was sometimes explicitly stated as type of bilingualism (e.g., simultaneous, sequential), was not well‐recorded. Among those who did report it, we could infer that 33 studies (35%) recruited simultaneous bilinguals, with only three studies (3%) recruiting sequential bilinguals. The remaining 61 studies either did not specify or did not provide information to ascertain a bilingual type or seemed to indicate a mixed group of bilingual types.

Bilingual participants were recruited from across 21 countries (Figure 3), with a majority from North America, with 31 studies (33%) from the United States and 14 studies from Canada (15%). Europe (e.g., Greece, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Spain, 41%) and the Middle East (e.g., Israel, United Arab Emirates, 11%) were also represented, and Asia/Oceania (e.g., Hong Kong, Japan, India, Australia) with 4 studies (4%). Four studies also recruited multinational samples of culturally comparable states (e.g., Canada and the United States; Belgium and the Netherlands). Homogenous language pairs (59 studies), with Spanish‐English and Russian‐Hebrew as the most common, slightly outnumbered the sampling of heterogenous bilingual groups (e.g., English‐Other language pairs, 36/95). In most cases, studies recruited from one language pair for homogenous groups; however, a few studies (4%) opted to study several homogenous groups (e.g., Spanish‐English, French‐English). Bimodal bilingualism was also featured, with more homogenous bimodal bilingual groups (4/5) than heterogenous (1/5) recruited.

FIGURE 3.

Frequency of included studies by geographic location and by language pairs spoken/signed. Note: ASL, American Sign Language; BSL, British Sign Language; NSL, Norwegian Sign Language; SEE, Signed Exact English; SLN, Sign Language of the Netherlands; SSD, Sign Supported Dutch. R script for this figure was adapted from Rocha‐Hidalgo and Barr (2023).

Most studies (71/95, 75%) measured participant SES, especially those that included both comparator groups (30/38, 79%) or compared bilingual groups (15/18, 83%). This was most often indexed by parental—often maternal—education (50/71, 70%), or a composite of parental education with other metrics like employment status and household income (10/71, 14%). A few studies used research‐developed measures of SES (e.g., Family Affluence Scale; Currie et al. 1997), teacher's rating of family SES, school postal code, qualifying for school's free/reduced lunch program, and the country's ranking of the city of residence. A couple of studies did not specify the methods by which they came to evaluate SES, but offered a rating, for example, ‘mid‐high SES’ or ‘poor SES’. Others shared only that SES was measured but never reported findings. Finally, one in four studies never measured SES in their samples; 67% of studies comparing MN to BN omitted measurement of this variable (26/39).

3.2.1.1. Assessing Bilingualism

Assessing bilingualism was most often conducted via parental report (85/95, 89%). This was done through a variety of methods, such as parent‐completed questionnaires, clinical interviews or standardized history (medical chart abstraction), parent language diaries, or simply confirmation with parents (e.g., does your child speak another language, yes/no?). Other lesser employed means derived bilingualism from the school setting (e.g., ELL designation, type of school, classroom teacher designation, school records, teacher rating) or occasionally child self‐rating.

Measures utilized for bilingual assessment were most often researcher‐created measures specifically for study at hand (44/95); however, a subset of studies (21/95) used previously established measures such as the Bilingual Language Exposure Calculator (BILEC; Unsworth 2013), Parents of Bilingual Children Questionnaire (PaBiQ; Tuller 2015), Bilingual Parent Questionnaire (BIPAQ; Abutbul‐Oz and Armon‐Lotem 2022), Bilingual Input‐Output Survey (BIOS; Peña et al. 2018) and Inventory to Assess Language Knowledge (ITALK; Peña et al. 2018), Child Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP‐Q; Marian et al. 2007), Alberta Language Development Questionnaire (ALDeQ; Paradis et al. 2010), Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire (ALEQ; Paradis 2011), Montreal Bilingual Language Use and Exposure Questionnaire (M‐BLUE; Beauchamp 2020) and the SOLOM. The assessment of bilingualism varied widely, though most measures focused on gauging the child's language environment and use and more rarely on language proficiency. Language proficiency in both languages is key to understanding a holistic view of a bilingual's language abilities. A few studies did separately evaluate proficiency through teacher rating (e.g., signing skills), oral proficiency ratings confirmed by parent questionnaires and direct measures of language abilities (e.g., Russian Language Proficiency Test for Multilingual Children, Gagarina et al. 2010; SOLOM; Parker et al. 1985). A handful of studies used multiple measures (4/95), combining parent reports with direct measures (e.g., child's language abilities as evidence of proficiency) and the child's ability on tasks.

3.2.2. Neurodiversity

While all studies focused on BN children, 39 studies compared bilinguals with an MN comparator group, 18 contrasted a BTD comparator group and 38 studies contained both comparison groups. Across all studies, we counted 5601 BN, 7373 MN and 2969 BTD total participants. However, this may represent an overestimation, as participant overlap was present across studies of similar research groups. The number of participants ranged from 2 to 2742, for a median sample size of 25 for BN, 21 for MN and 30 for BTD. The age range of the participants was reported to be between 1.6 and 25 years based on studies that shared a range, with median age of 7.32 years for BN, 7.40 years for MN and 7.08 years for BTD participants calculated based on group‐specific values.

Across all studies, DLD and ASD continue to be the most studied neurotype groups, followed by hearing impaired and cochlear implant users (HI/CI) and other neurotypes. Other neurotypes included preterm birth (n = 8), DS (n = 3), attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (n = 1), epilepsy (n = 1), paediatric stroke (n = 1) and speech‐sound impairment (n = 1). Two studies recruited groups that contained multiple diagnoses (e.g., ASD, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder and developmental disorder). The distributions for each neurotype group and comparison group are seen in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of included studies by neurotype and comparison groups.

| Diagnosis, n (%) | BN‐MN | BN‐BTD | BN‐MN‐BTD | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental language disorder | 1 (3%) | 14 (42%) | 18 (55%) | 33 |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 11 (37%) | 4 (13%) | 15 (50%) | 30 |

| Hearing impaired/cochlear implant users | 14 (78%) | 4 (22%) | 18 | |

| Preterm birth | 7 (88%) | 1 (13%) | 8 | |

| Down syndrome | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 3 |

| Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 1 (100%) | 1 | ||

| Epilepsy | 1 (100%) | 1 | ||

| Pediatric stroke | 1 (100%) | 1 | ||

| Speech sound impairment | 1 (100%) | 1 | ||

| Multiple diagnoses | 2 (100%) | 2 |

Note: Two studies recruited multiple separate groups including autism spectrum disorder and developmental language disorder.

Abbreviations: BN, Bilingual neurodivergent; BTD, Bilingual typically developing; MN, monolingual neurodivergent.

3.3. Inclusion: In What Roles Are Bilingual Individuals Included in Research?

Bilinguals primarily participated as subjects in quantitative research designs that involved comparisons between case and control groups (e.g., BN‐MN, BN‐BTD). These comparisons varied in number of groups from one comparator up to five and were based on group characteristics such as diagnosis (e.g., one or more neurodivergent vs. typically developing), language (e.g., one or more bilingual language pairs vs. monolingual), age (e.g., younger children, older children, adults), and other criteria (e.g., mean length of utterance).

A small number of studies incorporated longitudinal designs (9%), tracking bilingual participants over time to observe developmental changes, and retrospective designs (11%), utilizing existing medical records or prior research participation. However, none of the studies employed community‐based research approaches, such as co‐design or involving youth participants as community partners.

4. Discussion

We examined 95 recent studies on bilingualism in neurodivergent and neurotypical populations, using an equitable, (neuro)diverse, inclusive lens to identify the influence of potential biases in the current state of the research. Overall, equitable assessment of language and cognition in bilinguals is significantly impacted by the use of culturally and linguistically appropriate tools, the language(s) used for evaluation, and the knowledge brought in by the information source(s). Our discussion addresses the findings in relation to our research questions based on each pillar of this framework, as well as considerations for following the EDI framework in future research in neurodivergent and neurotypical populations.

4.1. Assessing Bilinguals Equitably

Eighty‐six percent of studies reviewed here assessed bilinguals’ abilities using tools developed for monolingual populations. While widespread, standardized norm‐referenced tests often lack appropriate norming samples validating their use in bilinguals. Grosjean (1998) emphasized that bilinguals’ abilities do not equate to the abilities of two monolingual speakers, as bilinguals develop their linguistic skills in relation to their two languages and share knowledge across. As such, standardized tests that are typically normed for monolinguals can disadvantage bilinguals (e.g., over‐ or underestimation of abilities). Using monolingual norms for bilinguals can have significant clinical implications for the bilingual community, as clinicians and educators might discourage families and their children from learning a second language (De Houwer 2023; Genesee 2022; Grosjean 1998). A further critique, informed by a Disabilities Studies and Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) perspective, can be found in the examination of racial ideologies behind the speech‐language pathology practices. Nair and colleagues shared a critical analysis of how standardized testing often privileges a ‘standard’ monolingual language, which can lead to the pathologizing of bilingual language variations in racial and linguistic minorities (Nair et al. 2023). This lens highlights that these norms are not neutral but rooted in White, middle‐class, and monolingual standards, which can lead to systemic biases that disproportionately affect individuals from marginalized backgrounds. This framework argues that the traditional ‘difference vs. disorder’ approach in speech‐language pathology, which aims to distinguish between language variations and disorders, often fails to account for the complex interplay of race, culture, and disability (Yu et al. 2021).

We found that among neurodivergent populations too, as with neurotypical populations, use of standardized tests (95%) was commonly employed to evaluate linguistic processes of expressive, receptive language and global language abilities, while batteries of executive function and low verbal/nonverbal tests of IQ were frequently evaluated to index cognitive ability. While standardized measures are valued for their discriminant properties, it is important to recognize that biases can still exist, even among gold‐standard assessments. Furthermore, it is important to consider that even when standardized tests are administered in both languages of bilingual individuals—aligned with the holistic evaluation approach—such assessments often assume that bilinguals possess two distinct, non‐interacting linguistic systems, effectively treating them as two separate monolinguals within a single mind. However, bilinguals engage in complex interlinguistic interactions, where skills in one language influence and support the other. Standardized tests may be less suitable to capture the dynamic and context‐dependent nature of bilingual language use, compared to alternatives like dynamic assessments (Caffrey et al. 2008; Grigorenko and Sternberg 1998; Wood et al. 2024). Translated tools, culturally adapted tools and bi/multilingual assessments tailored to the population are becoming more widely available (Bedore and Peña 2008; Bhalloo and Molnar 2023; Hemsley et al. 2014). However, these are often limited to select language pairs (e.g., Spanish‐English) or not widely implemented in practice (e.g., dynamic assessment, Dubasik and Valdivia 2020; Wood, Kika, et al. 2024). Direct linguistic translation alone is considered insufficient to reach functional and cultural equivalency and quality of the original instrument (Sousa and Rojjanasrirat 2011; Van Widenfelt et al. 2005). Instead, bilingual assessments (e.g., BESA) and multilingually adapted tools (e.g., LITMUS), which were used in a few of the reviewed studies, are better positioned to avoid underdiagnosis or over‐identification commonly reported in bilinguals, such as in the case of DLD (Bedore and Peña 2008; Kohnert 2010). In future studies, use of these bilingual and linguistically adapted tools should be prioritized to more accurately assess holistic language competence and account for interlinguistic transfer.

We found that holistic evaluation of both of the bilinguals’ languages is not common practice in research on neurodivergent populations, despite clear recommendations by clinical bodies (American Speech‐Language‐Hearing Association n.d., 2023). For nearly half of studies, the language of evaluation remains confined to just one of a bilingual individual's languages. Since language‐related diagnoses must be confirmed in both languages, it is essential that evaluations are also conducted in both languages to fairly assess abilities. Furthermore, this restriction ignores the dynamic and integrated nature of bilingual language use (see also Otheguy et al. (2015) on translanguaging). This issue is particularly pertinent to reported lexical‐related issues, most notably among included studies with bilinguals with ASD (Andreou et al. 2020; Peristeri et al. 2021; Peristeri, Vogelzang, et al. 2021; Skrimpa et al. 2022). Overall vocabulary size—considering total words known in both languages—is the more equitable option in comparing bilinguals to monolingual peers (Fennell and Lew‐Williams 2017; Poulin‐Dubois et al. 2013). However, across the reviewed studies, both languages were not fully considered in evaluations of vocabulary, which is also likely for other linguistic abilities evaluated, such as speech sound production, syntax, morphosyntax, and pragmatic abilities. Furthermore, the differences in the properties of the languages highlight another motivating factor to expand evaluations beyond one language (Kohnert 2010).

Assessments should also consider multiple sources of information to gain a comprehensive and holistic understanding of a bilingual's abilities. Parent‐reported measures and direct measures offer different perspectives on the child's language and cognition, each contributing essential components to the complete story—especially when the abilities of those bilingual children are considered whose languages are not spoken by the experimenter or the clinician. Parent ratings can provide valuable insights into a child's language use in unstructured conditions and everyday activities, while experimental tasks (i.e., researcher‐designed assessments like picture naming for language or the Flanker task for cognition) and standardized tests offer a more structured, less experience‐specific experience (Toplak et al. 2013). Informants like parents and teachers can fill in gaps by providing greater context into a child's language abilities and cognition beyond the testing session. For instance, parent ratings of the BRIEF have been found to diverge from performance‐based tasks of executive function, suggesting its clinical utility lies in complementing performance‐based tasks in order to assess behavioural concerns more generally (Mcauley et al. 2010). By leveraging the insights from both parent reports and child‐directed measures, a more comprehensive understanding of bilingual children's language development can be attained.

4.2. Enhancing Diversity Across Research

While study locations included bilinguals from across the globe, Western, English‐speaking countries—especially the United States and Canada—were over‐represented. As regions with substantial linguistic diversity and societal multilingualism are largely located in the ‘global south’ (Bylund et al. 2024; Kidd and Garcia 2022), it is imperative to broaden research efforts to include these multilingual regions. This geographic bias also led to a higher number of homogenous pairings being studied, especially among Spanish‐English bilinguals in the United States, compared to studies of heterogenous language pairings (societal language‐other). Moreover, bimodal bilingualism, the ability to use and understand two languages across different sensory modalities (such as a spoken and a signed language), was least represented in the research across only five studies.

As we limited this study to English and French publications (without limitations on language pairings studied within), it may have biased our results toward research from countries where these languages are more commonly used. Clinically oriented studies may be published in the language of the target community, as speech‐language professionals may not always have the resources or training to publish in English or French. While in this instance only nine studies were excluded due to language limitations, a broader issue persists: the dominance of English in scientific publishing continues to shape the accessibility and visibility of research from non‐English‐speaking regions. This highlights the need to recognize and address the impact of language bias on global research accessibility and representation.

Moreover, inconsistency in defining, measuring, and reporting of bilingualism is a limitation to the theoretical and clinical contributions derived from such research (also see Uljarević et al. [2016] and Kay‐Raining Bird et al. [2016]). The reviewed studies’ means of measuring bilingualism, from informant types to bilingual types based on timing and exposure, show significant variability. In instances where direct measurement was unachievable, researchers resorted to proxies such as the school setting or retrospective clinic data or chart review, introducing new challenges. Such approaches typically only capture a singular dimension of bilingualism or tangential concepts (e.g., culture, race/ethnicity), thereby compromising on data quality. Similar challenges persist in research focusing on neurotypical children (Rocha‐Hidalgo and Barr 2023; Surrain and Luk 2019) and ASD (Hantman et al. 2023). Moving forward, it is crucial for future research to meticulously document bilingualism, considering multidimensional factors such as language history, exposure levels, and language pairs. This approach will enable more accurate descriptions of bilingual samples and strengthen the design and interpretation of research, allowing for more nuanced analyses with continuous variables as opposed to solely categorical ones (Kremin and Byers‐Heinlein 2021).

The reviews by Uljarević et al. (2016) and Kay‐Raining Bird et al. (2016) both offered representations of diverse linguistic and neurodiverse experiences; however, ASD, DLD, and DS were prioritized given the research breadth. Uljarević et al. (2016) included studies on stuttering (classified under communication disorders) alongside these conditions, but other DSM‐classified disorders, such as motor disorder, specific learning disorder, ADHD, and other neurodevelopmental disorders, were either not found or excluded for not meeting diagnostic criteria. Other diagnoses not captured in the review include acquired disorders in infancy or childhood (e.g., paediatric stroke, traumatic brain injury, substance exposure, spinal cord injuries).

While it follows that bilingualism studies tend to focus on language‐related disorders such as DLD and ASD—given that bilingualism is inherently a language‐related phenomenon—this focus limits the scope of the literature and introduces selection bias within the synthesis. Research has shown that bilingualism can also affect general non‐linguistic cognitive mechanisms (Adesope et al. 2010; Hilchey and Klein 2011). For this reason, studies on bilingualism should be broadened to encompass a wider range of neurodivergent conditions, including both developmental and acquired disorders, to allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how bilingual neurodiversity works.

Further, SES posed another limitation to interpreting the reviewed studies, as it was not always controlled for or even measured in the research. Notably, 25% of studies did not measure SES, with 67% of those comparing monolingual to bilingual neurotypical children omitting this factor. When comparing monolinguals and bilinguals, SES has previously been identified as a modulating factor in the investigation of bilingualism in neurotypical children (Calvo and Bialystok 2014; Naeem et al. 2018). Bilinguals and monolinguals can differ in their SES—an environmental factor that can, independently from language experience, affect cognitive and language abilities. When SES is not controlled for, observed differences between groups risk being misattributed to language status alone, rather than to disparities of socioeconomic determinants (e.g., access to linguistic resources, educational opportunities, and exposure to dominant linguistic norms). This can inadvertently support deficit‐based perspectives of bilingualism, a narrative that is challenged in frameworks such as translanguaging and raciolinguistics. Therefore, whenever a comparison is made between monolinguals and bilinguals, SES factors should be controlled across groups. In the reviewed studies, SES was primarily indexed through parental education or a composite score with other metrics; however, at times only an author rating was provided without methods of measurement. To account for the impact of social determinants on health outcomes, SES needs to be systematically measured and controlled for (for one approach to this, see Singh et al. 2023).

This section has underscored the critical need for enhanced diversity across bilingualism research, encompassing geographic, linguistic, and neurodiverse representation, as well as methodological rigour. However, ‘standard’ language is a racialized construct, and even with rigorous controls, assessments may be biased (Flores and Rosa 2015). To make bilingualism research more diverse, methodologies must incorporate an understanding and address raciolinguistic bias.

4.3. Inclusivity in Bilingualism Research

Study designs often involved a case‐control group approach, where neurodivergent bilinguals were invited to participate at one time point. Studies typically included neurodivergent bilingual children, contrasting them with either monolingual neurodivergent peers or, less frequently, with typically developing bilingual children, or both. Current approaches in developmental sciences and even across this review position bilingual individuals as research subjects. However, alternative methods such as community‐based research advocate for a more inclusive role for bilingual participants across the research process. This approach, already prevalent in education and health fields, allows the bilingual community—including bilingual youth, caregivers and other stakeholders—to be actively engaged, from determining the research topic to designing the study and from dissemination to implementation. Likewise, neurodiversity research is increasingly repositioning neurodivergent individuals from research subjects to active collaborators. This aligns with the neurodiversity paradigm, which emphasizes the value of lived experience, as it offers crucial insights often missed by traditional approaches (Cioè‐Peña 2020; Pellicano and den Houting 2022). This inclusion addresses potential biases in research conducted without neurodivergent perspectives and ensures greater relevance to the community's needs (Sonuga‐Barke 2023). By actively involving bilingual and neurodivergent communities, researchers can adopt more participatory approaches that enhance the inclusiveness and relevance of their studies for the participant‐partners.

5. Recommendations for Future Clinical Research

Research design. Consider research designs that do not dichotomize research participants into the binary of monolingual versus bilingual, as this approach can overlook the diversity of language experiences that exist. As well, do not compare neurodivergent bilinguals’ abilities to those of neurotypical or neurodivergent monolinguals, but to typical bilinguals instead.

Research measurements. When evaluating language and cognition, assessments not biased against bilinguals and parent‐report measures should be used in tandem, as there may be a divergence in the construct measured. Standardized tests are advisable if they have been validated for a bilingual population; specific bilingual measures and alternatives (e.g., dynamic assessment, language sampling, language background or language history tools) represent a more suitable option where available.

Populations to be studied. Neurotypes other than ASD and DLD also deserve attention, as they too are affected by language and cognitive sequelae. Diversifying study populations to include not only a wider variety of linguistic backgrounds but also individuals with other forms of neurodivergence, and expanding their roles in research (e.g., community‐based research, participatory approaches), can enhance clinical relevance.

Measuring and reporting bilingual characteristics. To overcome difficulties in comparing bilingualism across studies, research should always provide detailed descriptions of their bilingual populations. Language background information should be collected by appropriate background questionnaires. Variables relevant to age of acquisition, amount/quality of exposure, frequency and context of usage should be reported about the languages investigated.

For clinical practice resources, see American Speech and Hearing Association (American Speech‐Language‐Hearing Association n.d.) and Speech Pathology and Audiology Canada (Crago and Westernoff 1997; Speech‐Language and Audiology Canada 2024) for recommendations on the assessment of bilinguals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material 1.

Funding: This research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant (RGPIN‐2019‐06523) to M.M. and Ontario Graduate Scholarship to K.I.L.

Note

Common abbreviations may differ based on which value is emphasized and as customary by country. The acronym commonly used in the United States is DEIA, with an emphasis on diversity (National Institutes of Health 2023). In Canada, EDI—emphasizing equity—may be more common (Canada Research Coordinating Committee 2021).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

- Abutbul‐Oz, H. , and Armon‐Lotem S.. 2022. “Parent Questionnaires in Screening for Developmental Language Disorder Among Bilingual Children in Speech and Language Clinics.” Frontiers in Education 7: 846111. 10.3389/feduc.2022.846111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T. , and Rescorla L.. 2001. Manual for the ASEBA School‐Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Adesope, O. O. , Lavin T., Thompson T., and Ungerleider C.. 2010. “A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of the Cognitive Correlates of Bilingualism.” Review of Educational Research 80, no. 2: 207–245. 10.3102/0034654310368803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano, A. R. , and Douglas M.. 2018. “Facilitating Preliteracy Development in Children With Hearing Loss When the Home Language Is Not English.” Topics in Language Disorders 38, no. 3: 194–201. 10.1097/TLD.0000000000000156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altman, C. , Harel E., Meir N., Iluz‐Cohen P., Walters J., and Armon‐Lotem S.. 2022. “Using a Monolingual Screening Test for Assessing Bilingual Children.” Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 36, no. 12: 1132–1152. 10.1080/02699206.2021.2000644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM‐5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech‐Language‐Hearing Association . n.d. “Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech‐Language Pathology [Practice Portal].” Practice Portal. Retrieved October 6, 2024. https://www.asha.org/Practice‐Portal/Professional‐Issues/Bilingual‐Service‐Delivery/.

- American Speech‐Language‐Hearing Association . 2023. Ad Hoc Committee on Bilingual Service Delivery: Competencies, expectations, and Recommendations for Multilingual Service Delivery [Final Report] . ASHA. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/reports/ahc‐bilingual‐service‐delivery‐final‐report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, M. , Tsimpli I. M., Durrleman S., and Peristeri E.. 2020. “Theory of Mind, Executive Functions, and Syntax in Bilingual Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Languages 5, no. 4: 67. 10.3390/LANGUAGES5040067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armon‐Lotem, S. , and Grohmann K. K., eds. 2021. Language Impairment in Multilingual Settings: LITMUS in Action Across Europe. Vol. 29. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Armon‐Lotem, S. , and Meir N.. 2016. “Diagnostic Accuracy of Repetition Tasks for the Identification of Specific Language Impairment (SLI) in Bilingual Children: Evidence From Russian and Hebrew.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 51, no. 6: 715–731. 10.1111/1460-6984.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asasumasu, K. 2015. PSA From the Actual Coiner of “Neurodivergent” . Lost in My Mind TARDIS. https://Sherlocksflataffect.Tumblr.Com/Post/121295972384/Psa‐Fromthe‐Actual‐Coiner‐Of‐Neurodivergent.

- Bao, W. , Alain C., Thaut M., and Molnar M.. 2024a. “Bilinguals Differ From Monolinguals in Attentional Resource Allocation During Spoken Language Processing: Pupillometry Evidence.” Preprint, PsyArxiv, June 13. 10.31234/osf.io/7brj8. [DOI]

- Bao, W. , Alain C., Thaut M., and Molnar M.. 2024b. “Is There a Bilingual Advantage in Auditory Attention Among Children? A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Standardized Auditory Attention Tests.” PLoS ONE 19, no. 5: e0299393. 10.1371/journal.pone.0299393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, X. , Komesidou R., and Hogan T. P.. 2024. “A Review of Screeners to Identify Risk of Developmental Language Disorder.” American Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology 33, no. 3: 1548–1571. 10.1044/2023_AJSLP-23-00286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley, N. 2006. Bayley Scales of Infant and Child Development. 3rd ed. Harcourt Assessment, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, M. L. H. 2020. “The Influence of Bilingualism in School‐Aged children : An Examination of Language Development in Neurotypically Developing Children and in Children With ASD.” PhD diss., Université de Montréal. https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/handle/1866/24617. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, M. L. H. , and MacLeod A. A. N.. 2017. “Bilingualism in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Making Evidence Based Recommendations.” Canadian Psychology 58, no. 3: 250–262. 10.1037/CAP0000122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedore, L. M. , and Peña E. D. 2008. “Assessment of Bilingual Children for Identification of Language Impairment: Current Findings and Implications for Practice.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 11, no. 1: 1–29. 10.2167/BEB392.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Zeev, S. 1977. “The Influence of Bilingualism on Cognitive Strategy and Cognitive Development.” Child Development 48, no. 3: 1009–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalloo, I. , and Molnar M. 2023. “Towards Linguistically‐Responsive Literacy Assessments in Bilingual Children: Establishing an Urdu Phonological Tele‐Assessment Tool (U‐PASS).” SocArxiv, Preprint, July 18. 10.31235/osf.io/mptf9. [DOI]

- Bishop, D. V. M. 2003. Children's Communication Checklist. 2nd ed. The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck, K. , Shafer V., Battino R., Valicenti‐McDermott R. M., Sussman E. S., and McGrath K.. 2022. “Language Disorders Research on Bilingualism, School‐Age, and Related Difficulties: A Scoping Review of Descriptive Studies.” Academic Pediatrics 22, no. 4: 518–525. 10.1016/J.ACAP.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha, M. , Chapman R., Giwa Onaiwu M., Kapp S. K., Stannard Ashley A., and Walker N.. 2024. “The Neurodiversity Concept Was Developed Collectively: An Overdue Correction on the Origins of Neurodiversity Theory.” Autism 28, no. 6: 1591–1594. 10.1177/13623613241237871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs‐Gowan, M. J. , and Carter A. S.. 2006. Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. , Sherbenou R. J., and Johnsen S. K.. 2010. Test of nonverbal intelligence: TONI‐4 . Pro‐ed.

- Brownell, R. 2000. Expressive One‐Word Picture Vocabulary Test: Manual. Academic Therapy Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bylund, E. , Khafif Z., and Berghoff R.. 2024. “Linguistic and Geographic Diversity in Research on Second Language Acquisition and Multilingualism: An Analysis of Selected Journals.” Applied Linguistics 45, no. 2: 308–329. 10.1093/applin/amad022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey, E. , Fuchs D., and Fuchs L. S.. 2008. “The Predictive Validity of Dynamic Assessment: A Review.” Journal of Special Education 41, no. 4: 254–270. 10.1177/0022466907310366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, A. , and Bialystok E.. 2014. “Independent Effects of Bilingualism and Socioeconomic Status on Language Ability and Executive Functioning.” Cognition 130, no. 3: 278–288. 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada Research Coordinating Committee . 2021. “Best Practices in Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Research.” Government of Canada, Updated October 10, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R. 2020. “Defining Neurodiversity for Research and Practice.” In Neurodiversity Studies, edited by Rosqvist H. B., Chown N., and Stenning A., 218–220. Routledge. 10.4324/9780429322297-21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cioè‐Peña, M. 2020. “Bilingualism for Students With Disabilities, Deficit or Advantage?: Perspectives of Latinx Mothers.” Bilingual Research Journal 43, no. 3: 253–266. 10.1080/15235882.2020.1799884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, C. , Baker D. L., and Allor J. H.. 2020. “Multiple Language Exposure for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder From Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities.” Bilingual Research Journal 43, no. 3: 286–303. 10.1080/15235882.2020.1799885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, J. N. , and Gruber C. P.. 2005. Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Crago, M. , and Westernoff F.. 1997. “Position Paper on Speech‐Language Pathology and Audiology in the Multicultural, Multilingual Context.” Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology and Audiology (CASLPA) 21, no. 3: 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, K. , and McLeod S.. 2014. “A Systematic Review of Cross‐Linguistic and Multilingual Speech and Language Outcomes for Children With Hearing Loss.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 17, no. 3: 287–309. 10.1080/13670050.2012.758686/SUPPL_FILE/RBEB_A_758686_SM4595.PDF. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Currie, C. E. , Elton R. A., Todd J., and Platt S.. 1997. “Indicators of Socioeconomic Status for Adolescents: The WHO Health Behaviour in School‐aged Children Survey.” Health Education Research 12, no. 3: 385–397. 10.1093/her/12.3.385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cat, C. , Kašćelan D., Prévost P., Serratrice L., Tuller L., and Unsworth S. 2023. “How to Quantify Bilingual Experience? Findings From a Delphi Consensus Survey.” Bilingualism 26, no. 1: 112–124. 10.1017/S1366728922000359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, A. 2023. “The Danger of Bilingual‐monolingual Comparisons in Applied Psycholinguistic Research.” Applied Psycholinguistics 44, no. 3:. 10.1017/S014271642200042X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, A. , Bornstein M. H., and Putnick D. L.. 2014. “A Bilingual‐Monolingual Comparison of Young Children's Vocabulary Size: Evidence From Comprehension and Production.” Applied Psycholinguistics 35, no. 6. 10.1017/S0142716412000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAnda, S. , Bosch L., Poulin‐Dubois D., Zesiger P., and Friend M.. 2016. “The Language Exposure Assessment Tool: Quantifying Language Exposure in Infants and Children.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 59, no. 6: 1346–1356. 10.1044/2016_JSLHR-L-15-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Hoyo Soriano, L. , Villarreal J., and Abbeduto L.. 2023. “Parental Survey on Spanish‐English Bilingualism in Neurotypical Development and Neurodevelopmental Disabilities in the United States.” Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders 7, no. 4: 591–603. 10.1007/s41252-023-00325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis, D. C. , Kaplan E., and Kramer J.. 2001. Delis‐Kaplan Executive Function System. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, H. , van der Meer L., and Kagohara D.. 2015. “Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder From Bilingual Families: A Systematic Review.” Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2, no. 1: 26–38. 10.1007/S40489-014-0032-7/TABLES/1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubasik, V. L. , and Valdivia D. S.. 2020. “School‐Based Speech‐Language Pathologists' Adherence to Practice Guidelines for Assessment of English Learners.” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 52, no. 2: 485–496. 10.1044/2020_LSHSS-20-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L. M. , and Dunn D. M.. 2007. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Fourth Edition. Pearson Education. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft15144‐000 [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, P. 2022. “The Neurodiversity Approach(es): What Are They and What Do They Mean for Researchers?” Human Development 66, no. 2: 73–92. 10.1159/000523723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano, C. 2001. “The Benefits of Biculturalism: Exposure to Immigrant Culture and Dropping out of School Among Asian and Latino Youths.” Social Science Quarterly 82, no. 4: 865–879. 10.1111/0038-4941.00064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, C. , and Lew‐Williams C.. 2017. “Early Bilingual Word learning.” In Early Word Learning, edited by G. Westermann and Mani N., 1st ed, 110–122. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315730974-9/EARLY-BILINGUAL-WORD-LEARNING-CHRISTOPHER-FENNELL-CASEY-LEW-WILLIAMS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores, N. , and Rosa J.. 2015. “Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education.” Harvard Educational Review 85, no. 2: 149–171. 10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. R. , and Schroeder S. R.. 2022. “Assessing Language Skills in Bilingual Children: Current Trends in Research and Practice.” Journal of Child Science 12, no. 1: e33–e46. 10.1055/s-0042-1743575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst, G. , and Grin F.. 2023. “Multilingualism, Multicultural Experience, Cognition, and Creativity.” Frontiers in Psychology 14. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1155158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagarina, N. V. , Klassert A., and Topaj N.. 2010. “Russian Language Proficiency Test for Multilingual Children [Sprachstandstest Russisch für Mehrsprachige Kinder].” ZAS Papers in Linguistics 54: 54–54. 10.21248/ZASPIL.54.2010.402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, F. 2022. “The Monolingual Bias a Critical Analysis.” Journal of Immersion and Content‐Based Language Education 10, no. 2: 153–181. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, G. , Isquith P. K., Guy S., and Kenworthy L.. 2015. BRIEF2. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. 2nd ed. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Golash‐Boza, T. 2005. “Assessing the Advantages of Bilingualism for the Children of Immigrants.” International Migration Review 39, no. 3: 721–753. 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00286.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, B. 2006. “Clinical Implications of Research on Language Development and Disorders in Bilingual Children.” Topics in Language Disorders 26, no. 4: 305–321. https://journals.lww.com/topicsinlanguagedisorders/Fulltext/2006/10000/Clinical_Implications_of_Research_on_Language.00004.aspx?casa_token=0bbZbxHFLbUAAAAA:9UBEAvfoLovPuG2QEFWYWqEL0b8PRmrXNkuNof‐Vd0Umfiag‐KHZNREQAFvOwMdn8KYHNpb47HU8vgz0AAiIEXBW. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko, E. L. , and Sternberg R. J.. 1998. “Dynamic Testing.” Psychological Bulletin 124, no. 1: 75–111. 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, F. 1998. “Studying Bilinguals: Methodological and Conceptual Issues.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 1, no. 2: 131–149. 10.1017/s136672899800025x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guiberson, M. 2013. “Bilingual Myth‐Busters Series Language Confusion in Bilingual Children.” Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Populations 20, no. 1: 5–14. 10.1044/cds20.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnerud, H. L. , Ten Braak D., Reikerås E. K. L., Donolato E., and Melby‐Lervåg M.. 2020. “Is Bilingualism Related to a Cognitive Advantage in Children? A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 146, no. 12: 1059–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantman, R. M. , Choi B., Hartwick K., Nadler Z., and Luk G.. 2023. “A Systematic Review of Bilingual Experiences, Labels, and Descriptions in Autism Spectrum Disorder Research.” Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1095164. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1095164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Head, L. M. , Baralt M., and Darcy Mahoney A. E.. 2015. “Bilingualism as a Potential Strategy to Improve Executive Function in Preterm Infants: A Review.” Journal of Pediatric Health Care 29, no. 2: 126–136. 10.1016/J.PEDHC.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, G. , Holm A., and Dodd B.. 2014. “Identifying Language Difference versus Disorder in Bilingual Children.” Speech, Language and Hearing 17, no. 2: 101–115. 10.1179/2050572813Y.0000000027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilchey, M. D. , and Klein R. M.. 2011. “Are There Bilingual Advantages on Nonlinguistic Interference Tasks? Implications for the Plasticity of Executive Control Processes.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 18, no. 4: 625–658. 10.3758/S13423-011-0116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, E. , Core C., Place S., Rumiche R., Señor M., and Parra M.. 2012. “Dual Language Exposure and Early Bilingual Development.” Journal of Child Language 39, no. 1: 1–27. 10.1017/S0305000910000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute . 2017. “Checklist for Quasi‐Experimental Studies.” The Joanna Briggs Institute . https://jbi.global/critical‐appraisal‐tools.

- Kaufman, A. S. , and Kaufman N. L.. 2004. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. 2nd ed. Pearson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kay Raining‐Bird, E. , Lamond E., and Holden J.. 2012. “Survey of Bilingualism in Autism Spectrum Disorders.” International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 47, no. 1: 52–64. 10.1111/J.1460-6984.2011.00071.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay‐Raining Bird, E. , Genesee F., Verhoeven L.. 2016. “Bilingualism in Children With Developmental Disorders: A Narrative Review.” Journal of Communication Disorders 63: 1–14. 10.1016/J.JCOMDIS.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, E. , and Garcia R.. 2022. “How Diverse Is Child Language Acquisition Research?” First Language 42, no. 6: 703–735. 10.1177/01427237211066405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert, K. 2010. “Bilingual Children With Primary Language Impairment: Issues, Evidence and Implications for Clinical Actions.” Journal of Communication Disorders 43, no. 6: 456–473. 10.1016/J.JCOMDIS.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert, K. , and Medina A.. 2009. “Bilingual Children and Communication Disorders: A 30‐Year Research Retrospective.” Seminars in Speech and Language 30, no. 4: 219–233. 10.1055/S-0029-1241721/ID/56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]