Abstract

Purpose

Robotic approaches have been steadily replacing laparoscopic approaches in metabolic and bariatric surgeries (MBS); however, their superiority has not been rigorously evaluated. The main goal of the study was to evaluate the 5-year utilization trends of robotic MBS and to compare to laparoscopic outcomes.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of 2015–2019 MBSAQIP data. Kruskal-Wallis test/Wilcoxon and Fisher’s exact/chi-square were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Generalized linear models were used to compare surgery outcomes.

Results

The use of robotic MBS increased from 6.2% in 2015 to 13.5% in 2019 (N= 775,258). Robotic MBS patients had significantly higher age, BMI, and likelihood of 12 diseases compared to laparoscopic patients. After adjustment, robotic MBS patients showed higher 30-day interventions and 30-day readmissions alongside longer surgery time (26–38 min).

Conclusion

Robotic MBS shows higher intervention and readmission even after controlling for cofounding variables.

Keywords: Robotic bariatric surgery, Laparoscopic bariatric surgery, MBS

Introduction

Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) procedures have evolved from open to laparoscopic allowing shorter intervention times, length of hospital stay, and postoperative recovery, as well as lower postoperative pain [1]. Robotic surgeries are a more recent approach to MBS that has gained popularity over the past several years. According to the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, a robotic surgery is “a surgical procedure or technology that adds a computer technology-enhanced device to the interaction between the surgeon and the patient during a surgical operation” [2]. One of the main proposed benefits of using robotic approaches involves the improved dexterity and precision in tissue manipulation [1].

Comparison of robotic versus laparoscopic MBS has shown conflicting results in previous studies. MBSAQIP 2015–2018 (N= 571,417 cases) data shows that robotic surgeries have resulted in in lower bleeding, complication rates, and length of stay compared to laparoscopic surgeries [3]. However, these improvements were made at the expense of higher leakage rates and longer surgery duration [4]. A systematic review and meta-analysis involving 34 studies (N= 27,997 cases) found no significant differences between robotic and laparoscopic procedures regarding postoperative complications, length of stay, reoperation, conversion, and mortality [5]. However, robotic procedures had longer operative times and hospital costs compared to laparoscopic surgeries [5]. Converse to what was observed in the MBSAQIP 2015–2018 data, according to this meta-analysis, the incidence of anastomotic leak was lower in robotic versus laparoscopic procedures [5]. A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis involving 30 clinical trials (N= 210,420 cases) showed robotic surgeries resulted in lower mortality (2.4 OR) but longer reoperation times (~27 min) compared to laparoscopic procedures [6]. Length of stay, reoperation within 30 days, overall complications, pulmonary embolism, blood loss, and stricture were not different between robotic and laparoscopic procedures [6]. Similarly, a recent study utilizing a matched approach using the 2015–2018 MBSAQIP database (n= 93,802) showed robotic surgeries increased the time invested by 30% for SG and 25% for RYGB, respectively. Length of stay and readmission rates were also higher in robotic procedures versus their laparoscopic counterparts [7]. Thus, based on the current literature, particularly considering the results from the national database, the beneficial effects of performing robotic versus laparoscopic MBS is still in debate, with the most consistent finding being a longer intervention time by the surgeon [8].

The main goal of the present study was to identify the trends in utilization of robotic MBS between 2015 and 2019 using the MBSAQIP database. The secondary goal was to compare robotic versus laparoscopic outcomes in MBS. Based on previous trends and smaller datasets, it was hypothesized that the use of robotic procedures had increased throughout the 5-year time frame and that robotic procedures do not have superior outcomes when compared to laparoscopic procedures.

Methods

Study Design

A retrospective cross-sectional analysis was conducted using the 2015–2019 MBSAQIP data. The UT Health Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects considers a retrospective analysis of public, anonymized data, such as the MBSAQIP dataset, exempt from review and, thus, it does not require ethical approval or formal participant consent.

Data Source

The American College of Surgeons and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery merged their programs in 2012 to form the MBSAQIP which evaluates the national accreditation standards for bariatric surgery centers in the USA and Canada [9]. The MBSAQIP is the largest, bariatric specific, clinical dataset in the country. The merged 2015–2019 MBSAQIP participant use data file (PUF) was used for this analysis. All MBS patients who received clinical care at an accredited center were included in the PUF. Data input is standardized across centers ensuring reliable data [10].

Variables

Surgical approaches were classified into three groups with CPT code 43775 as laparoscopic SG; CPT codes 43845 and 43633 as biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS); and CPT codes 43846, 43847, 43644, and 43645 as RYGB. Independent and dependent outcome variables were dichotomized using yes/no categories. The covariates used for analysis were age, sex, ethnicity/race, BMI, staple line reinforcement, and baseline comorbidities that significantly differed by groups such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, mobility device, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, renal insufficiency, therapeutic anticoagulation, steroid/Immunosuppressant, diabetes mellitus, functional health status, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea, inferior vena cava filter, and previous organ transplant. Age was classified into four groups: patients less than 18, 18 to 30 years, 31 to 60 years, and greater than 60. Ethnic groups were classified by MBSAQIP as Hispanic, non-Hispanic White (NHW), non-Hispanic Black (NHB), and other. The MBSAQIP defines (1) “reoperation” as any additional surgical procedure to correct a condition not corrected by a previous operation or to correct a secondary effect caused by a prior surgery (including revision) and that took place within 30-days post-surgery; (2) “readmission” as any hospital admission after the patient had been discharged and that took place within 30-days after the MBS; and (3) “intervention” as any medical activity undertaken with the objective of improving patients health during the first 30-days post-MBS. For supplementary table 1, preoperative BMI was classified into four groups using the following cutoff points: BMI < 35, BMI 35 to 39, BMI 40 to 49, and BMI ≥50kg/m2.

Participants

The PUF contains 173 HIPAA-compliant variables on 206,570 cases submitted from 868 centers in 2019; 204,837 cases submitted from 854 centers in 2018; 200,374 from 832 centers in 2017; 186,772 from 791 centers in 2016; and 168,903 from 742 centers in 2015. Inclusion criteria were limited to patients aged > 19 and < 70 years. Cases with missing age (n= 648) were excluded from the analysis. The final analytical sample utilized for the present study included 775,258 adult patients after excluding patients with prior MBS.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of continuous variables such as age, BMI, and surgery time, was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Comparison of categorical variables, such as frequency of metabolic and bariatric surgery procedures by type and year, was performed using the Fisher’s exact test, chi-square tests, and generalized linear models. Generalized linear models with normal distribution and identity link were created to examine temporal trends. Comparison of outcome variables between laparoscopic and robotic procedures was performed with additional logistic regression models. Both crude and adjusted odds ratios (controlling for age, sex, ethnicity/race, BMI, staple line reinforcement, and baseline comorbidities that significantly differed by groups such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, mobility device, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, renal insufficiency, therapeutic anticoagulation, steroid/Immunosuppressant, diabetes mellitus, functional health status, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea, inferior vena cava filter, and previous organ transplant) were generated. P value was considered significant if <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

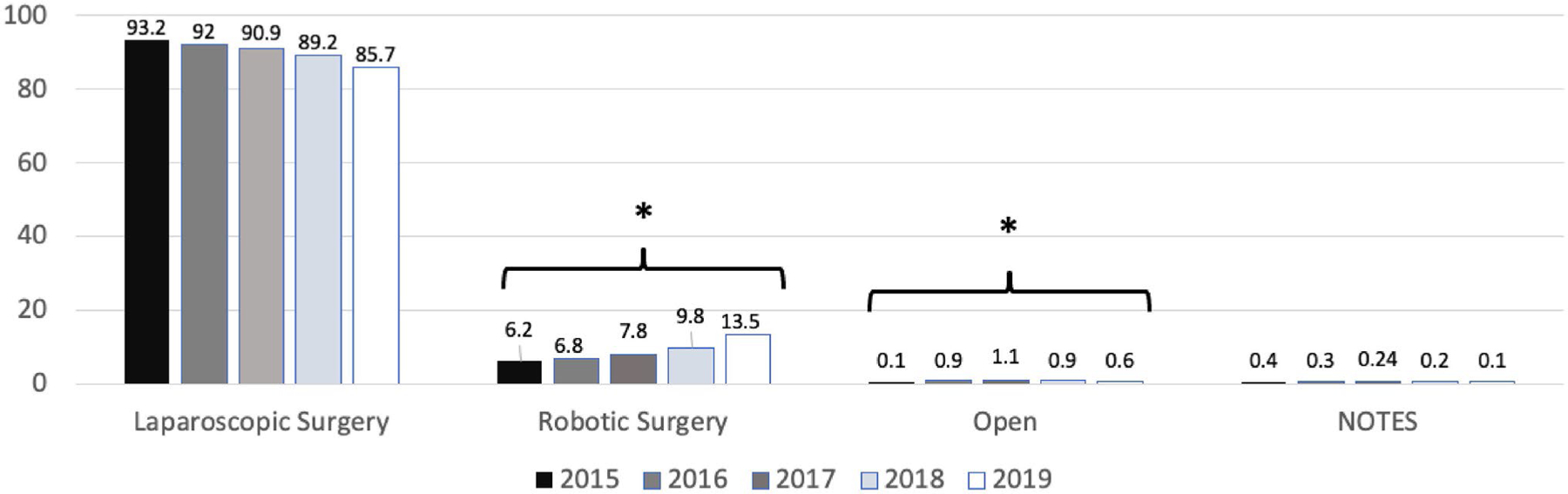

A total of 775,258 MBS procedures were captured in the database within our inclusion criteria between 2015 and 2019. During this period, the utilization of laparoscopic MBS decreased from 93.2 to 85.7%, whereas the percentage of robotic MBS significantly increased from 6.2 to 13.5% (p <0.01) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of metabolic and bariatric surgery procedures, MBSAQIP, 2015–2019. Generated from GLM procedure. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopy. * Denotes significant trend (p <0.05)

SG was the most common utilized procedure (71.9%), followed by RYGB (27.0%), and BPD-DS (1.1%). A robotic approach for SG (6.0 to 13.7% [p <0.01]), RYGB (7.2 to 13.5% [p <0.05]), and BPD-DS (21.2 to 25% [p <0.05]) showed a significant incremental trend from 2015 to 2019 (Table 1). BMI did not significantly impact the rate of utilization of robotic or laparoscopic SG and RYGB (Supplementary table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of metabolic and bariatric surgery procedures by type and year, MBSAQIP 2015 to 2019

| Approach | Total (2015–2019) N= 775,258 |

2015 N= 133,552 |

2016 N= 149,026 |

2017 N= 160,897 |

2018 N= 165,234 |

2019 N= 166,549 |

Trend pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | 557,236 (71.9) | ||||||

| Laparoscopic | 506,010 (90.81) | 85,871 (93.94) | 99,347 (93.00) | 107,965 (91.95) | 108,830 (89.95) | 103,997 (86.23) | 0.382 |

| NOTES | 285 (0.05) | 4 (0) | 99 (0.09) | 88 (0.07) | 59 (0.05) | 35 (0.03) | 0.886 |

| Open | 93 (0.02) | 20 (0.02) | 20 (0.02) | 14 (0.01) | 20 (0.02) | 19 (0.02) | 0.846 |

| Robotic | 50,848 (9.13) | 5515 (6.03) | 7354 (6.88) | 9349 (7.96) | 12,082 (9.99) | 16,548 (13.72) | 0.003 |

| RYGB | 209,379 (27.0) | ||||||

| Laparoscopic | 189,126 (90.33) | 37,711 (91.89) | 37,638 (92.08) | 38,281 (91.64) | 37,817 (89.98) | 37,679 (86.30) | 0.912 |

| NOTES | 120 (0.06) | 4 (0.01) | 46 (0.11) | 48 (0.11) | 16 (0.04) | 6 (0.01) | 0.758 |

| Open | 931 (0.44) | 362 (0.88) | 244 (0.60) | 173 (0.41) | 87 (0.21) | 65 (0.15) | 0.017 |

| Robotic | 19,202 (9.17) | 2961 (7.22) | 2948 (7.21) | 3273 (7.83) | 4108 (9.77) | 5912 (13.54) | 0.041 |

| BPD-DS | 8643 (1.1) | ||||||

| Laparoscopic | 6503 (75.24) | 818 (74.09) | 1018 (76.54) | 1315 (77.08) | 1676 (75.67) | 1676 (73.25) | 0.005 |

| NOTES | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0) | - |

| Open | 317 (3.67) | 52 (4.71) | 78 (5.86) | 93 (5.45) | 54 (2.44) | 40 (1.75) | 0.561 |

| Robotic | 1823 (21.09) | 234 (21.20) | 234 (17.59) | 298 (17.47) | 485 (21.90) | 572 (25.00) | 0.015 |

GLM procedure

BPD-DS, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; NOTES, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery; RYGB, Roux-en-Y Gastrectomy; and SG, sleeve gastrectomy

Patients undergoing MBS through a robotic approach had significantly higher age and BMI, and a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, renal insufficiency, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea, inferior vena cava filter, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, anticoagulation therapy, and mobility devices, while also having lower functional health status. Patients undergoing robotic MBS were significantly less likely to be female and to have a prior organ transplant in comparison to patients undergoing laparoscopic MBS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics by metabolic and bariatric surgery procedure

| Variable | Laparoscopic | Robot-assisted | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N= 729,884) | (N= 72,911) | ||

| Age | 44.51 ± 12.01 | 44.70 ± 12.04 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 45.22 ± 7.93 | 45.49 ± 8.09 | <0.001 |

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| Hispanic | 72,411 (9.92) | 6593 (9.04) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 425,802 (58.34) | 41,998 (57.60) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 118,955 (16.30) | 13,966 (19.15) | |

| Other | 112,716 (15.44) | 10,354 (14.20) | |

| Male | 148,803 (20.39) | 14,479 (19.87) | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 61,296 (8.40) | 5988 (8.21) | 0.085 |

| GERD | 221,657 (30.37) | 23,433 (32.14) | <0.001 |

| Mobility device | 10,872 (1.49) | 1439 (1.97) | <0.001 |

| Oxygen dependent | 4992 (0.68) | 493 (0.68) | 0.808 |

| MI history | 9075 (1.24) | 854 (1.17) | 0.093 |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 7688 (1.05) | 742 (1.02) | 0.368 |

| PTCA | 13,657 (1.87) | 1440 (1.98) | 0.049 |

| Hypertension | 345,479 (47.33) | 35,578 (48.80) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 170,882 (23.41) | 17,529 (24.04) | <0.001 |

| Prior DVT | 11,860 (1.62) | 1142 (1.57) | 0.232 |

| Dialysis | 2238 (0.31) | 248 (0.34) | 0.120 |

| Renal insufficiency | 4512 (0.62) | 535 (0.73) | <0.001 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation | 19,855 (2.72) | 2185 (3.00) | <0.001 |

| Pre-op steroid/immunosuppressant | 1679 (1.74) | 1326 (1.82) | 0.109 |

| DM | <0.001 | ||

| Insulin | 60,264 (8.26) | 6558 (8.99) | |

| Non-insulin | 128,226 (17.57) | 13,254 (18.18) | |

| Functional health status | <0.001 | ||

| Independent | 723,035 (99.06) | 71,967 (98.71) | |

| Partially dependent | 4483 (0.61) | 518 (0.71) | |

| Totally dependent | 2118 (0.29) | 401 (0.55) | |

| COPD | 11,474 (1.57) | 1344 (1.84) | <0.001 |

| History of PE | 8566 (1.17) | 885 (1.21) | 0.337 |

| Sleep apnea | 274,800 (37.65) | 28,086 (38.52) | <0.001 |

| IVC filter | 4035 (0.55) | 474 (0.65) | 0.001 |

| Previous organ transplant | 1030 (0.23) | 84 (0.16) | 0.001 |

Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables for laparoscopic vs. robotic-assisted approaches

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; IVC, inferior vena cava; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolism; and PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

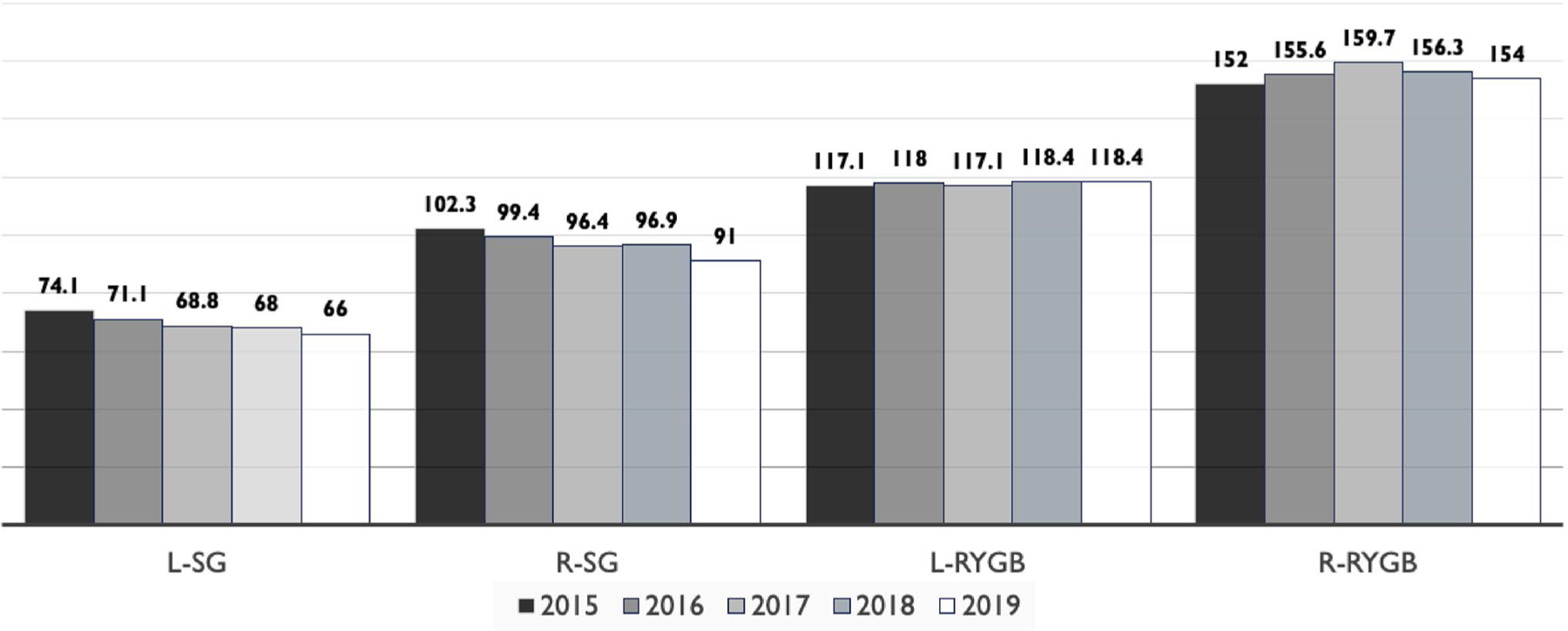

Robotic SG and RYGB are on average ~26 and ~37.7 min longer than laparoscopic approaches, representing a 27.4% and 24.2% longer time investment, respectively. Analysis showed a decrease in both laparoscopic SG time (from 74.1 ± 36.2 to 66.0 ± 33.6 min [~8.0 min]) and robotic SG time (from 102.3 ± 42.9 to 91.0 ± 39.8 [~11.3 min]) from 2015 to 2019. Conversely, the time invested in both laparoscopic (117.1 ± 52.5 to 118.4 ± 52.8 [~1.3 min]) and robotic RYGB (152.6 ± 63.7 to 154.0 ± 60.6 [~2.0 min]) slightly but significantly increased from 2015 to 2019 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Operative time in minutes by metabolic and bariatric surgery approach and procedure. Kruskal-Wallis test. L-SG, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; R-SG, robotic sleeve gastrectomy; L-RYGB, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastrectomy; R-RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastrectomy

Crude logistic regression models showed robotic surgeries to have a 16% higher risk of 30-day reoperation (OR= 1.16, 95% CI= 1.09–1.24), a 20% higher risk of 30-day intervention (OR= 1.20, 95% CI= 1.12–1.28), and a 19% higher risk of 30-day readmission (OR= 1.19, 95% CI= 1.15–1.24) compared to laparoscopic surgeries. Logistic regression models adjusted showed a 31% higher 30-day intervention (OR= 1.31, 95% CI= 1.04, 1.65) and a 15% higher 30-day readmission (OR= 1.15, 95% CI= 1.02, 1.30), in the robotic versus the laparoscopic group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds of mortality and other primary outcomes, robotic versus laparoscopic surgery approach, MBSAQIP, 2015 to 2019

| Outcome | Laparoscopic | Robotic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR | 95% CI | p value | Adj ORa | 95% CI | p value | ||

| 30-day mortality | 1.0 (ref) | 0.877 | (0.675, 1.140) | 0.327 | 0.462 | (0.187, 1.142) | 0.094 |

| 60-day mortality | 1.0 (ref) | 1.756 | (0.414, 7.456) | 0.445 | -b | - | 0.670 |

| 30-day reoperation | 1.0 (ref) | 1.160 | (1.088, 1.238) | <0.001 | 0.934 | (0.719, 1.212) | 0.606 |

| 30-day intervention | 1.0 (ref) | 1.197 | (1.122, 1.277) | <0.001 | 1.313 | (1.042, 1.654) | <0.001 |

| 30-day readmission | 1.0 (ref) | 1.194 | (1.150, 1.239) | <0.001 | 1.154 | (1.023, 1.302) | 0.020 |

| Stroke | 1.0 (ref) | 1.306 | (0.716, 2.384) | 0.384 | 1.709 | (0.366, 7.990) | 0.496 |

| Intraoperative/ post MI | 1.0 (ref) | 0.572 | (0.320, 1.023) | 0.060 | -b | - | 0.882 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1.0 (ref) | 1.142 | (0.918, 1.421) | 0.233 | 1.109 | (0.630, 1.951) | 0.981 |

| Postoperative DVT | 1.0 (ref) | 0.917 | (0.761, 1.105) | 0.361 | 0.953 | (0.582, 1.559) | 0.979 |

| Septic shock | 1.0 (ref) | 0.589 | (0.078, 4.425) | 0.607 | - b | - | 0.969 |

| Sepsis | 1.0 (ref) | 0.589 | (0.141, 2.451) | 0.467 | - b | - | 0.964 |

ORs and 95% CI derived from logistic regression. Outcomes adjusted for potential confounders (age, sex, ethnicity/race, BMI and staple line reinforcement, gastroesophageal reflux disease, mobility device, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, renal insufficiency, anticoagulation therapy, steroid/immunosuppressant use, diabetes mellitus, functional health status, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea, inferior vena cava filter, and previous organ transplant).

Value not reported because of disproportionality and low sample size within the procedure while adjusting for covariates

MI, myocardial infraction; DVT, peep vein thrombosis

Discussion

Results here show that the use of robotic MBS has been steadily increasing from 2015 to 2019 with the most pronounced increment observed in 2018 to 2019. Specifically, there was a 217% increase in number of primary robotic MBS completed from 2015 to 2019. After stratifying by MBS type, the rate of utilization of both robotic SG and RYGB procedures doubled from 2015 to 2019. Adjusted analysis showed a higher 30-day intervention and readmission rates as well as a longer surgery time (26–38 min) in comparison to laparoscopic approaches.

Performing MBS in patients with high degrees of obesity comes with surgical challenges such as space constraints caused by increased liver size, presence of intra-abdominal fat, and a thick abdominal wall which complicate the handling of manual instruments [1]. Robotic MBS has been proposed to overcome these issues, potentially improving surgery outcomes; however, these claims have not been supported by the presented results.

Previous research using the MBSAQIP database shows a significant improvement in operative time from 2015 to 2018 in the robotic cohort of MBS [3]. However, our analysis using 2015–2019 data shows that after stratifying by surgery type, robotic surgeries were significantly shorter by ~11 min only in the SG but not the RYGB group. According to a recent world-wide systematic review and meta-analysis, robotic surgeries have ~27.6 min longer operative times in comparison to laparoscopic procedures [6]. Our analysis shows a similar trend in surgery duration between robotic versus laparoscopic procedures for both SG (28.3 min longer in the robotic SG) and RYGB (~34.9 min longer in the robotic RYGB) with a more pronounced difference in the later one. These results show longer surgery duration in robotic procedures, particularly when utilized to perform an already longer MBS surgery, RYGB.

When using the MBSAQIP 2015–2018 data, robotic MBS showed higher 30-day readmission and 30-day intervention rates which were mainly driven by robotic sleeve gastrectomy [3, 4]. Two additional studies utilizing the same dataset/years but selecting only subgroups of matched participants, also found a higher readmission rate in the robotic RYGB and robotic SG groups, as well as higher reintervention rate in robotic SG versus their laparoscopic counterparts [7, 11]. Our unadjusted analysis, which includes 2019 data, corroborates these results showing a significantly higher 30-day reoperation, 30-day readmission, and 30-day intervention rates in the robotic surgery group. However, it is possible that the higher reoperation, readmission, and interventions could be driven by the higher baseline comorbidity rates present in the robotic group, as having a higher number of risk factors pre-MBS has shown to increase post-MBS complication rates [12–14]. Therefore, after controlling for age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, staple line reinforcement, and comorbidities (specifically the ones that showed significant between-group differences at baseline), we found that surgical reoperations were no longer significantly different between groups; however, readmissions and interventions remained significant and even increased their effect. In other words, even after controlling for potential baseline confounders, patients within the robotic group were more likely to be readmitted to the hospital and to receive medical interventions within the 30-days post-surgery.

Several studies have been published using the MBSAQIP database; however, this is the only study that has compared the trends and outcomes of robotic versus laparoscopic procedures using the most recent dataset 2015–2019 containing a total of 775,258 cases. We present both crude and adjusted covariates to control for any potential confounders. Despite these strengths, this review has several limitations that should be mentioned. First, bariatric surgeons generally perform only one type of MBS procedure (either robotic or laparoscopic); therefore, comparison between procedures is indirectly also comparing surgeons’ skills. Second, this is a retrospective analysis on a prospectively collected database and thus is vulnerable to the biases associated with retrospective analyses, such as (1) coding errors and missing data, (2) models adjustment limited to variables that have already been collected, and (3) lack of relevant variables such as surgeon’s experience, surgery cost, stapler or robotic platform utilized (newer platform involves a shorter learning curve), as well as information on weight loss, comorbidity resolution, and long-term complications >30-days post-surgery. Third, since statistical significance is largely dependent on sample size and since the present analysis was performed on a large database, it is possible that we observe significant statistical differences that are not clinically relevant. Lastly, there is no standardization on the quantity of robotic system utilization for procedures listed as “robotic” and therefore, it is not possible to determine the percentage of robotic system use in a “robotic-assisted” surgery. Future data collection should separate hybrid surgeries from surgeries involving a single approach.

Conclusion

Analysis of MBSAQIP 2015–2019 data showed robotic surgeries to have a higher 30-days intervention and readmission rates, alongside a longer surgery time (26–38 min) in comparison to laparoscopic approaches. Future research comparing the effectiveness and safety of robotic versus laparoscopic approaches would benefit from the creation of an experimental study in which both procedures (1) are performed by the same surgeons, who should ideally have similar skills in robotic (new platform, Vinci Xi) and laparoscopic approaches, and (2) have participants with similar comorbidity rates.

Supplementary Material

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-05964-7.

Key Points.

Two hundred and seventeen percent higher utilization of robotic metabolic and bariatric surgeries between 2015 and 2019.

First article to stratify by year and bariatric surgery type the time invested in robotic procedures.

After adjustment, 30-day intervention and readmissions remained higher in the robotic MBS group.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [grant R01MD011686].

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethical Approval For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent Informed Consent does not apply.

Conflict of Interest Dr. de la Cruz (surgeon) has received funds from Intuitive Surgical Inc. for education purposes since 2019. Dr. de la Cruz’ relationship with Intuitive Surgical Inc. has been reviewed by the University of Miami, Florida in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. Dr. Kukreja (surgeon) is a consultant and key opinion leader for Intuitive Surgical Inc. since 2019. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jung MK et al. Robotic bariatric surgery: a general review of the current status. The International Journal of Medical Robotics + Computer Assisted Surgery : MRCAS. 2017;13(4). % 10.1002/rcs.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pernar LIM, Robertson FC, Tavakkoli A, et al. An appraisal of the learning curve in robotic general surgery. Surg Endosc 2017;31(11):4583–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tatarian T, Yang J, Wang J, et al. Trends in the utilization and perioperative outcomes of primary robotic bariatric surgery from 2015 to 2018: a study of 46,764 patients from the MBSAQIP data registry. Surg Endosc 2021;35(7):3915–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarritt T, Hsu CH, Maegawa FB, et al. Trends in utilization and perioperative outcomes in robotic-assisted bariatric surgery using the MBSAQIP database: A 4-Year Analysis. Obes Surg 2021;31(2):854–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li K, Zou J, Tang J, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2016;26(12):3031–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Miao L, Ren Z, Li Y. Robotic bariatric surgery for the obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2021;35(6):2440–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudash M, Kuhn J, Dove J, et al. The longitudinal efficiency of robotic surgery: an MBSAQIP Propensity matched 4-year comparison of robotic and laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2020;30(10):3706–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundberg PW, Wolfe S, Seaone J, et al. Robotic gastric bypass is getting better: first results from the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14(9):1240–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surgery ACoSaASoMaB. Metabolic and bariatric surgery accreditation and quality improvement program. Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/mbsaqip. Accessed 1 Oct 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surgery ACoSaASoMaB. User guide for the 2018 participant use data file (PUF). Available at: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/bariatric/mbsaqip_2018_puf_userguide.ashx. Accessed 1 Oct 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Chaar M, King K, Salem JF, et al. Robotic surgery results in better outcomes following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program analysis for the years 2015–2018. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2021;17(4):694–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalsky MP et al. Cardiovascular risk factors after adolescent bariatric surgery. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20172485. % 10.1542/peds.2017-2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husain F, Jeong IH, Spight D, et al. Risk factors for early postoperative complications after bariatric surgery. Ann Surg Treat Res 2018;95(2):100–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nickel F, de la Garza JR, Werthmann FS, et al. Predictors of risk and success of obesity surgery. Obes Facts. 2019;12(4):427–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.