ABSTRACT

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are aggressive high-fatality cancers that affect children and adults. Most STS subtypes harbor an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) and respond poorly to immunotherapy. Therapies capable of dismantling the immunosuppressive TME are needed to improve sensitivity to emerging immunotherapies. Activation of the Stimulator of INterferon Genes (STING) pathway has shown promising anti-tumor effects in preclinical models of carcinoma, but evaluations in sarcoma are lacking. Herein, we sought to examine the immune modulation and therapeutic efficacy of three translational small molecule STING agonists in an immunologically cold model of STS. Three classes of STING agonists, ML RR-S2 CDA, MSA-2, and E7766 were evaluated in an orthotopic KrasG12D/+ Trp53-/- model of STS. Dose titration survival studies, cytokine serology, and tumor immune phenotyping were used to examine STING agonist efficacy following intra-tumoral treatment. All STING agonists significantly increased survival time, however, only E7766 resulted in durable tumor clearance, inducing CD8+ T-cell infiltration and activated lymphocyte transcriptomic signatures in the TME. Antibody depletion was used to assess the dependency of treatment responses on CD8+ T-cells, showing that in their absence, tumor clearance did not occur following E7766 therapy. Using STING deficient mice, and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, we demonstrated that STS clearance following STING therapy was dependent on host STING and not tumor-intrinsic STING pathway functionality. E7766 represents a promising candidate able to remodel the TME of murine STS tumors toward an inflamed phenotype independent of tumor-intrinsic STING functionality, and should be considered for potential translation in STS treatment.

KEYWORDS: Solid tumor, STING, sarcoma, Immunotherapy

Background

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are rare mesenchymal lineage malignancies that affect children and adults.1,2 STS are rapidly progressive, high-fatality cancers, that are resistant to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapies.3 Immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint blockade therapy have generally shown limited efficacy against STS and success has been exclusive to select subtypes.4–6 At present, the large majority of STS are considered to be poorly responsive to immunotherapies in part due to their tumor microenvironment (TME) which is enriched for TGF-β pathway activation7 and characterized by an abundance of immunosuppressive myeloid lineage cell populations including (CD206+) macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and a paucity of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL).8–12 Further, the TME also shows low expression of PD-L1 T-cell checkpoint regulators.8,13 To increase the susceptibility of STS to immune-mediated treatments, strategies capable of reshaping the TME to increase antigen presentation, TIL infiltration and reprogram immunosuppressive cell types in the TME toward an immunologically activated phenotype are required. Thus, to evaluate this strategy, we have chosen to assess activation of the STimulator of INterferon Genes (STING) pathway using small molecule agonists in the high grade, immunotherapy resistant, immunogenically cold KrasG12D/+ Trp53-/- model of STS.14–17

STING, an endoplasmic reticulum associated molecule, plays a key role in linking the innate and adaptive immune systems upon recognition of cyclic dinucleotides, formed by cGAS in response to viral or host DNA, or small molecule STING agonists.18–20 STING pathway activation results in potent type I interferon production, tumor necrosis, maturation and activation of antigen presenting cells, repolarization of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), and recruitment of effector lymphocytes.18–20 Studies have shown impressive CD11c dendritic cell and CD8+ lymphocyte mediated tumor clearance effects following intra-tumoral or systemic STING agonist treatment in pre-clinical models of carcinoma and melanoma.21–24 Numerous STING agonists are now in early phase clinical trials for carcinomas, melanoma, and lymphomas25,26

We have recently shown that intra-tumoral (i.t.) STING activation using the murine STING agonist, DMXAA, can also induce potent immune-mediated tumor clearance in the murine KP model of high-grade STS, with durable systemic immunity against lung and extremity tumor re-challenge.16 Given that DMXAA does not activate the human STING protein, agonists capable of activating both mouse and human STING have been developed.21,27–30 These translational STING agonists are distinct, showing variable chemical compositions, stability, and modes of administration. We sought to evaluate and compare the immunomodulatory properties and anti-tumor efficacies of three classes of STING agonists, ML RR-S2 CDA (CDN – cyclic dinucleotide STING agonist), MSA-2 (non-nucleotide STING agonist), and E7766 (macrocycle-bridged STING agonist), in an orthotopic, immunologically cold model of high-grade STS. Herein, we demonstrate the macrocycle-bridged STING agonist, E7766 provided the most therapeutically robust immunogenic remodeling of the STS TME and CD8+ lymphocyte mediated tumor clearance. Finally, we demonstrate that STS clearance following STING therapy does not require tumor cell STING expression, but is entirely dependent on non-malignant host cell STING expression. Therefore, we propose that E7766 mediated STING agonist therapy may be a suitable immunotherapy for STS regardless of a tumor’s STING expression status.

Methods

Mice

All animal experiments included in this work received ethics approval from the University of Calgary’s Animal Care Committee under protocol number AC-23–0048. Mice were housed in a biocontainment 2 facility at the University of Calgary under the following protocol number AC-23–0048. The mouse housing facility was maintained under the following conditions: 12-hour light/dark cycle, 22 ± 1°C, and 30–35% humidity. Mice received standard food and water ad libitum. All mice used were 6–12 weeks of age and both males and females were evenly distributed amongst groups. C57BL/6 Mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and bred in house (C57BL/6J stock #000664) and Goldenticket (C57BL/6J-Sting1gt/gt) stock #017537). Mice were humanely euthanized via cervical dislocation according to experimental endpoints, once tumors were found to be 15 milimeter in size in the length, depth, or width dimensions, or if any outward signs of physical deterioration were observed including reduced food or water intake, weight loss, hunching, or fur ruffling. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Cell lines

All cell lines were maintained in an incubator set to 37°C with 5% CO2. All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma.

RAW 264.7 cells

Macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, a gift from Dr. Frank Visser (University of Calgary), were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin and streptomycin (Penstrep).

KP STS cells

KP STS cell line was generated by our laboratory and has been previously characterized elsewhere.16 KP cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penstrep.

KP STING knockout (k/o) STS cells

The KP STING k/o was generated from KP cells using CRISPR Cas9 technology to ablate Sting1 protein expression from the cell line. Similar to the parental cell line, KP STING k/o cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penstrep.

Tumor engraftment, monitoring, and treatment

KP and KP STING k/o cell line tumors were intramuscularly engrafted in the right hindlimbs of C57BL/6 or Goldenticket mice. Tumors were engrafted in male and female mice aged 6–12 weeks, unless otherwise indicated. KP cells were resuspended in sterile, serum free media and kept on ice. Mice were anaesthetized using isofluorane, shaved to expose the injection site, and injected with 100,000 cells intramuscularly in the right lateral gastrocnemius. Tumors were detectable within 7 days of implantation and at this time tumor volume measurements using digital calipers (3x weekly) and bioluminescence imaging using an IVIS Lumina (Perkin Elmer) (1x weekly) were completed for 90 days. Tumor volume was calculated as (tumor volume = (L+X) x L x X x (0.2618)). Re-challenge inoculations were performed in survivor mice via the same procedure, instead using the contralateral hindlimb. All STING agonist treatments were done on day 7 following STS cell injection.

STING agonists

5’6 dimethyl-xanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA)

DMXAA (Sigma-Aldrich, cat#D5817-25 MG) is a flavone acetic acid and is a well-characterized murine STING agonist which has shown therapeutic benefits in several preclinical models of malignancy. Previous studies in the KP model of STS have shown 50% tumor clearance following i.t. injection of DMXAA at a dose of 18 mg/kg which was selected for this study.

ML RR-S2 CDA (CDN)

CDN (Chemietek, #1638750–95–4) is a cyclic dinucleotide STING agonist capable of activating both murine and human STING. Previous preclinical studies have shown promising results, at doses varying from 50–500 µg administered i.t. In our dose titration studies, doses investigated ranged from 50–500 µg for initial survival studies, while tumor immune characterization and combination therapy investigations employed a dose of 100 µg.

MSA-2

MSA-2 (MedChemExpress, cat#129425–81–6) belongs to the non-nucleotide class of STING agonists. At physiological pH, MSA-2 exists as a monomer, but in hypoxic tumor environments, undergoes dimerization and subsequently binds to the STING protein in both mice and human cells. MSA-2, can be administered orally, subcutaneously, or intra-tumorally.28 Based on previous literature, we investigated 18 mg/kg i.t. and 50 mg/kg subcutaneous (s.c.) doses in survival studies. An operational dose of 18 mg/kg i.t. was used for immune characterization and combination therapy investigations

E7766

E7766 (Chemietek, cat#2242635–02–3) is a novel macrocycle bridged STING agonist currently under preclinical and clinical investigation.27,31 Similarly, it is capable of activating the STING protein in murine and human cells. In survival dose titration studies, doses varied from 3-9 mg/kg administered i.t. An operational dose of 4 mg/kg was selected for combination therapy and tumor immune population characterization experiments.

In vivo antibody administration

Anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy

Eight doses of 250 µg anti-PD-1 (Cedarlane, cat#BE0146) were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) on days 9, 11, 15, 18, 22, 25, 29, and 32 following tumor engraftment. STING combinatorial therapies were administered on day 7, prior to the start of anti-PD-1 therapy. Tumor BLI and volume were monitored for 90 days.

Anti-CD8+ T-cell depletion

Neutralizing anti-CD8α (Cedarlane, cat#BE0061) or IgG2b (Cedarlane, cat# BE0090) isotype control antibodies were administered i.p. to C57BL/6 mice on days 4, 7, and 10 (250 μg/day) following orthotopic KP tumor engraftment alongside E7766 therapy (4 mg/kg i.t.) on day 7. Mice received an additional i.p. dose of 125 μg antibody weekly until an endpoint was reached. At humane endpoint, tumors, blood, and spleens were collected to assess CD8+ T-cell depletion.

Immunblotting

STING agonist treated cell pellets were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (50 m M Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1%Triton-X 100, distilled water) supplemented with 1 tablet of Phospho-STOP (Roche, cat#04906837001) and 1 tablet of EDTA-Complete (Roche, cat#04693159001). Extracted proteins (20 μg) were loaded into a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and separated by mass (100 V for 90 min) (BIO-RAD PowerPac 200). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in TBST buffer (1x TBS + 5% Tween 20) and incubated with one of the following rabbit monoclonal antibodies overnight (1:1000 dilution) in 5% BSA in TBST buffer: (anti-pIRF3 (Cell Signaling Technology, cat#4947), anti-p-STING (Cell Signaling Technology, cat# 72971), anti-STING (Cell signaling technology, cat#13647), pTBK1 (Cell signaling technology, cat#5483). Twenty-four hours later, membranes were washed and incubated with a secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2500 dilution) in 5% skim milk in TBST buffer (7074, Cell SignalingTechnology). An equal part solution of HRP substrate peroxide solution and substrate luminal reagent and (Immobilon Western Kit: Chemiluminescent HRP substrate) was used to image the membranes. Stained membranes were stripped and finally probed with anti-β-actin antibody (1:10,000 dilution) in 5% milk in TBST buffer (664804, BioLegend) and imaged. A 10–250 kDA protein ladder kaleidoscope was used for assessment (161–0375, BioRAD). For studies in RAW 264.7, proteins extracted from RAW 264.7 cells treated with cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate (cGAMP) were used as a positive control as it is the natural ligand to STING.

Serum and cell supernatant cytokine array

Tumor-bearing mice were treated with standardized doses of DMXAA, CDN, MSA- 2, E7766, or control and subsequently sacrificed 6 h post-therapy. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture and centrifugated for 10 mins at 4°C at 13,000 r.p.m. Cell supernatants from STING agonist treated RAW264.7 and KP STS cells were collected. All studies used Luminex xMAP technology to complete multiplexed quantification of 44 mouse cytokines. Analyses were completed with the LuminexTM 200 system (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) by Eve Technologies Corp. (Calgary, Alberta) using the MilliporeSigma Mouse Cytokine 44-Plex Discovery Assay. The assay was completed in accordance with the protocol provided by the manufacturer by Eve TechnologiesTM. All results are reported in pg/mL.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions from tumor, blood, and spleen samples were then stained with zombie aqua or near infrared (Biolegend) viability dye (diluted at 1:10000) according to the manufacturer’s protocol for 30 mins at room temperature in the dark (Biolegend). Next, samples were washed with FACS buffer and pelleted at 300 x g for 7 mins at 4°C and resuspended in 1 mL of FACS buffer containing TrueStain fcX (Biolegend) block to reduce nonspecific antibody binding (diluted 1.5:100) for 15 mins. Finally, samples were stained with various antibodies for 1 hour in the dark at 4°C (Appendix, Table 1). Prior to acquisition on the Attune NxT flow cytometer (Life Technologies), samples were washed with FACS buffer and resuspended in 300 μl of FACS buffer. Cell phenotypes were identified as per Table 2 (Appendix).

Nanostring transcriptomics

Tumor samples were extracted from mice 24 h, 72 h, and 1-week following STING agonist therapy and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for 15 mins prior to transfer to a −80°C freezer for long-term storage. Tumors were subsequently provided to the Precision Oncology Hub (POH, University of Calgary) Laboratory for RNA extraction and sample preparation for the NanoString ImmunOncology 360 panel according to the manufacturer’s instructions. nCounter data was generated and analyzed using NanoString’s nSolver software. Z-scores associated with lower expression are represented by the color “tin” while z-scores associated with higher relative expression are represented by the color “plum” in each heatmap.

Statistics

All statistical assessments were completed with the guidance of a biostatistician (GEA). Analyses were completed in Graphpad Prism (v10.1.1). Non-parametric tests were used for all analyses to accout for the non normal distribution of data. For tests comparing STING agonist therapies and control groups, a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons was selected. For tests comparing two groups, a Mann-Whitney U test was completed. Kaplan Meier analyses with Log rank (Mantel-Cox) tests were performed for survival studies. A cox-proportional hazard ratio was added to assess synergy among STING + anti-PD-1 combination treatments.

Results

E7766 is superior to other translational STING agonists by inducing durable tumor clearance of KP sarcomas

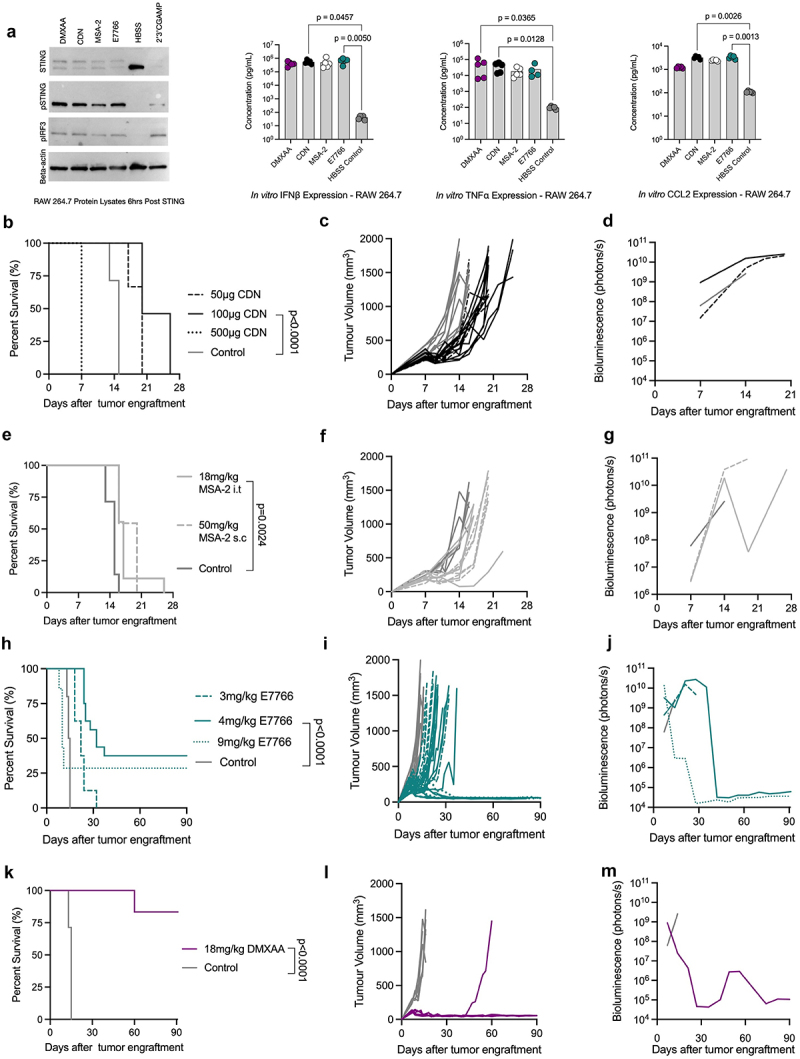

When administered at equimolar amounts, we confirmed that CDN, MSA-2, and E7766 can all functionally activate murine STING as shown by immunoblot and cytokine array (Figure 1a). Next, we investigated survival outcomes for each agonist in response to several dosing regimens. Immune competent C57BL/6 mice were engrafted with KP STS cells and treated i.t. with CDN, MSA-2, or E7766. A significant extension in survival time was observed at the 100 µg dose of CDN, with 46% of mice surviving between 21–26 days before reaching experimental endpoint compared to all control mice reaching this endpoint within 13–15 days; although none of the CDN treated mice at any dose demonstrated durable tumor clearance (Figure 1b-d). Any dose exceeding 100 µg of CDN resulted in death within the first 24 hrs of therapy, most dramatically so in the 500 µg cohort (Figure 1b). For MSA-2, we evaluated both i.t. (18 mg/kg) and subcutaneous (50 mg/kg) doses, given that it is a non-nucleotide STING agonist specifically designed to dimerize and activate STING in the hypoxic TME. No toxicity was observed at the doses evaluated, and a significant extension in survival time was observed relative to controls with the i.t. dose 20% (16–27 days) (Figure 1e-g). Finally, we tested i.t. doses of E7766. Tumor clearance was observed at various doses, although any dose exceeding 4 mg/kg resulted in toxicity and need for euthanasia within the first week of therapy. At the 4 mg/kg dose, no toxicity was observed and survival frequencies of 38% were observed compared to controls (Figure 1h-j). From these experiments, operational doses for each agonist were selected for further phenotypic delineation; 100 µg of CDN, 18 mg/kg of MSA-2 i.t., and 4 mg/kg of E7766. A DMXAA cohort treated with 18 mg/kg i.t. were followed as a positive control, demonstrating that 83% of mice are durable cured of primary STS tumors (Figure 1k-m), consistent with previous findings.32

Figure 1.

E7766 induces tumor clearance in KP sarcomas. a. Immunoblot and cytokine concentrations from RAW264.7 cells following equimolar treatment with STING agonists. cGAMP treatment was used as a positive control condition. b. Overall survival of STS bearing mice treated i.T. With 50 µg (n=6), 100 µg (n=10), or 500 µg of CDN (n=10) and control (n=7) (log-rank Mantel-Cox test). c & d. Tumor volume (c) and bioluminescence (d) of CDN treated mice over time. e. Overall survival of STS bearing mice treated with 18 mg/kg of MSA-2 i.T. (n=9) or 50 mg/kg of MSA-2 subcutaneously (n=11) and control (n=7) (log rank Mantel-Cox test). f & g Tumor volume (f) and bioluminescence (g) of MSA-2 treated mice over time. h. Overall survival of STS bearing mice treated i.T. With 3 mg/kg (n=8), 4 mg/kg (n=16), or 9 mg/kg (n=7) of E7766 and control (n=10) (log rank Mantel-Cox test). i & j Tumor volume (i) and bioluminescence (j) measurements of E7766 treated mice over time. k. Overall survival of STS bearing mice treated i.t. With 18 mg/kg (n=6) and control (n=10) (log rank Mantel-Cox test). l & m. Tumor volume (i) and bioluminescence (j) measurements of E7766 treated mice over time. All bioluminescence figures represent the average BLI signal for each condition.

E7766 induces significant systemic elevation of interferon-mediated cytokines and induces immunogenic restructuring in the KP sarcoma TME

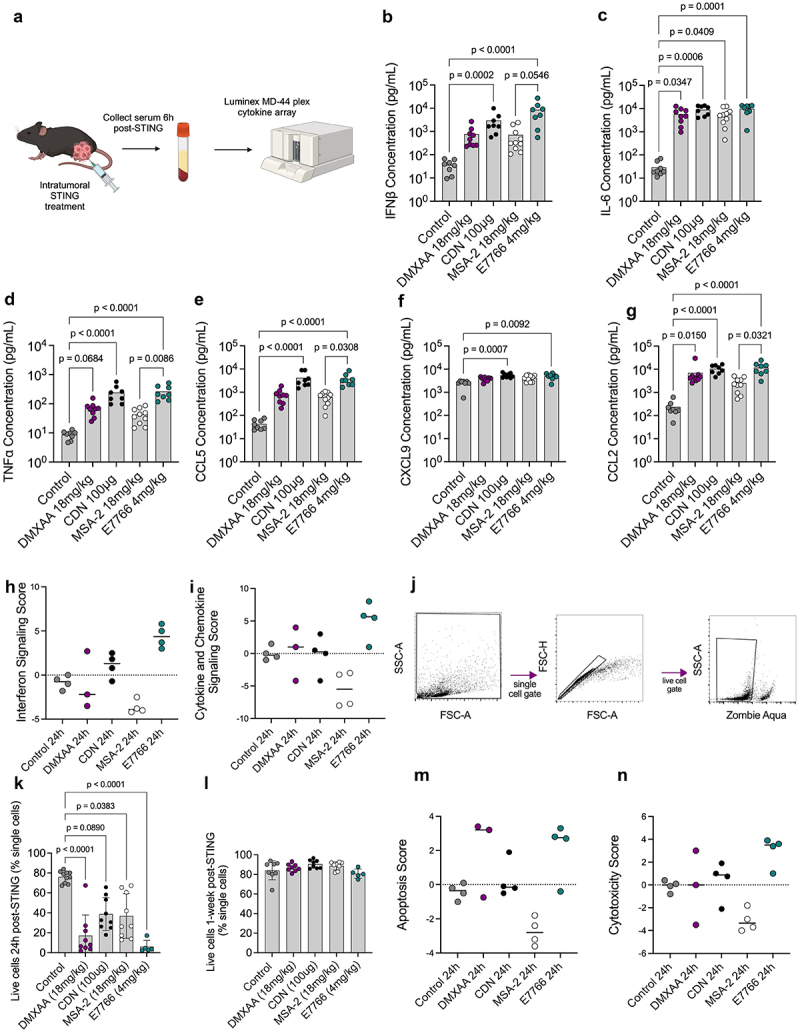

While all three agonists can activate murine and human STING, differences in survival outcomes emerged. To better understand these differences, we sought to quantify systemic cytokines and the immune organization of TME induced by each agonist. Sera were collected from mice 6 h following STING therapy to quantify systemic cytokine concentrations (Figure 2a). The sera from mice in the CDN and E7766 conditions contained similar levels of many cytokines, namely IFNβ and TNFα (Figure 2b-g). MSA-2 consistently generated the lowest systemic levels of key STING-related cytokines including IFNβ, TNFα, CCL5, and CCL2 compared to all other agonists (Figure 2). Similarly, at the tumor transcriptomic level, interferon and cytokine signaling levels were most pronounced in the E7766 condition 24 h post therapy (Figures 2h&i). Flow cytometry revealed that in the first 24 h following STING therapy, significant amounts of cell death were present across all agonists relative to control. Although not significant, it is worth noting that both DMXAA and E7766, the two agonists capable of inducing tumor clearance in this model, appeared to have the lowest percentage of live cells at this time point and a similar trend was visualized in the transcriptome apoptosis scores at 24 h, indicating that both DMXAA and E7766 generated higher apoptosis scores relative to the other STING agonists (Figure 2j-n).

Figure 2.

E7766 and CDN lead to similar systemic cytokine production phenotypes 6h following therapy, and all STING agonists induced significant amounts of cell death within the tumor microenvironment at 24h post-therapy. a. Schematic of experimental design created with BioRender.com. Mice were engrafted with 100,000 KP STS cells and one week later were treated with either 18 mg/kg DMXAA, 100 µg CDN, 18 mg/kg MSA-2, 4 mg/kg E7766, or control. Six hours follow treatment, serum was collected for cytokine analyses. b-g. Serum concentrations of IFNβ, IL-6, TNFα, CCL5, CXCL9, CCL2, respectively (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, n= 8–10 per condition). H&I. interferon signaling (h) and cytokine and chemokine signaling (i) scores generated from STING treated tumors using the Nanostring® advanced analysis tool 24h following STING therapy. j. Flow cytometry gating strategy for identifying dead cells. k&l Percentage of live cells at 24h (k) and 1-week (l) following STING therapy. m&n apoptosis (m) and cytotoxicity (n) scores generated from STING treated tumors using the Nanostring® advanced analysis tool 24h following STING therapy.

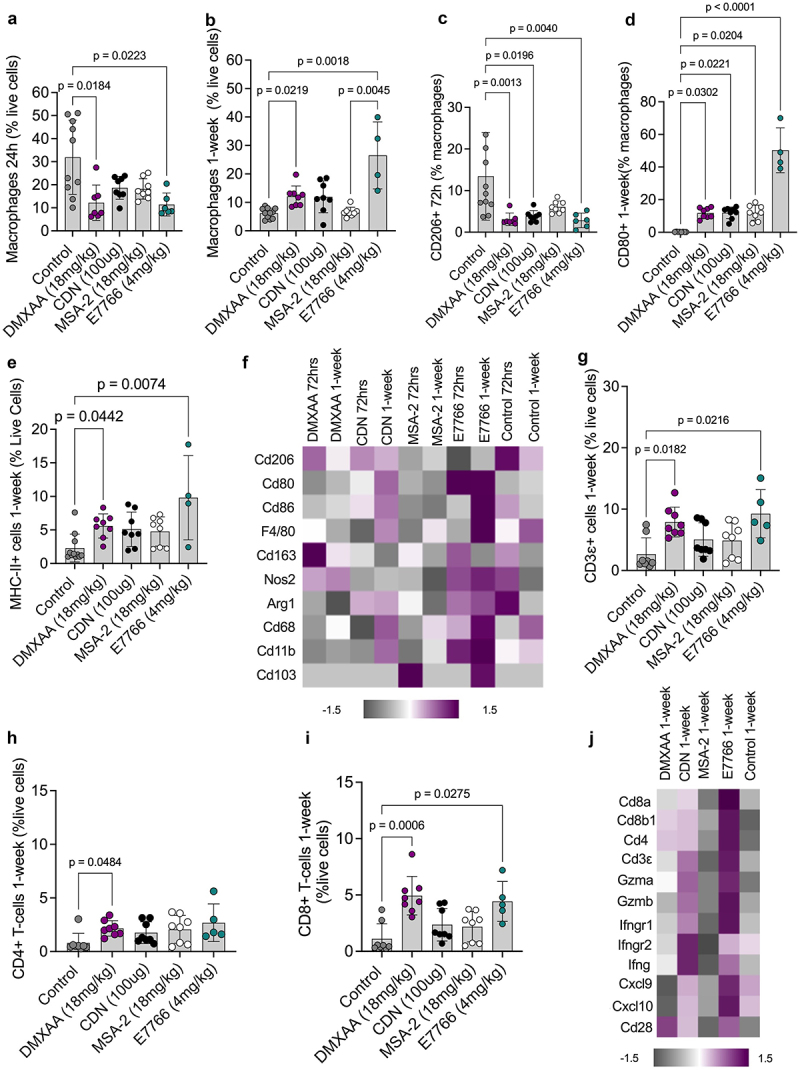

In an effort to identify differences amongst the various STING agonists, we sought to characterize immune tumor microenvironment changes using FACS and investigating transcriptomic changes following STING agonist treatment at various timepoints. Both DMXAA and E7766 conditions yielded significantly lower percentages of macrophages within the TME at the 24 h timepoint relative to controls (Figure 3a). In contrast, at 1-week, both DMXAA and E7766 contain significantly higher macrophage frequencies relative to control and MSA-2 (Figure 3b). Further, at 1-week following STING therapy, E7766 treated tumors contained significantly higher proportions of anti-tumor CD80+ macrophages relative to controls (Figure 3d) shifting away from the higher proportions of immunosuppressive CD206+ macrophages observed in control tumors at 72 h (Figure 3c). Additionally, 1-week following STING therapy, E7766 resulted in significantly greater proportions of MHC-II+ myeloid cells in the TME (Figure 3e). E7766 treated tumors demonstrated increased mRNA expression of genes associated with anti-tumor macrophage phenotypes (Cd80, Cd86, Cd68, Nos2) (Figure 3f). Parallels between the transcriptomic and flow cytometry data were also seen in control tumors as evidenced by an enrichment in genes associated with immune suppressive macrophages, including Cd163, Cd206, and Arg1 (Figure 3f).

Figure 3.

E7766 therapy appears to polarize the myeloid TME compartment of the KP STS towards an immunogenic phenotype.a&b. Proportion of macrophages (F480+/CD11b+) cells at 24h and 1-week following STING agonist administration, respectively, as a percentage of live cells. c. Proportion of CD206+ macrophages as a percentage of macrophages 72hrs following STING therapy. d. Proportion of CD80+ macrophages as a percentage of macrophages 1-week following STING therapy. e. Proportion of MHC-II+ myeloid cells as a percentage of live cells 1-week following STING therapy. f. Heatmap of transcriptomic expression of genes associated with markers of myeloid lineage cells. Proportion of CD3ε+ (g), CD4+ (h), and CD8+ (i) as a percentage of live cells 1-week after STING agonist administration. j. Heatmap of gene expression signatures associated with markers of lymphocyte activation 1-week following STING therapy (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, n=5–8 per condition).

Next, lymphocyte populations in the STS TME were assessed following STING therapy. Similar to DMXAA, E7766 therapy resulted in higher frequencies of both CD3ε and CD8+ T-cells relative to controls, a finding that was not observed among the other STING agonists at 1-week following therapy (Figure 3g & I), while DMXAA uniquely showed significantly higher frequencies of CD4+ T-cells relative to controls, which was not demonstrated in the E7766 condition (Figure 3h). E7766 displayed the greatest enrichment in transcriptomic markers of lymphocyte activation at the 1-week timepoint (Figure 3j). In summary, we show that E7766 and DMXAA, the agonists associated eradication of KP sarcomas, the greatest TME polarization away from immunosuppressive TAMs and the greatest enrichment of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes.

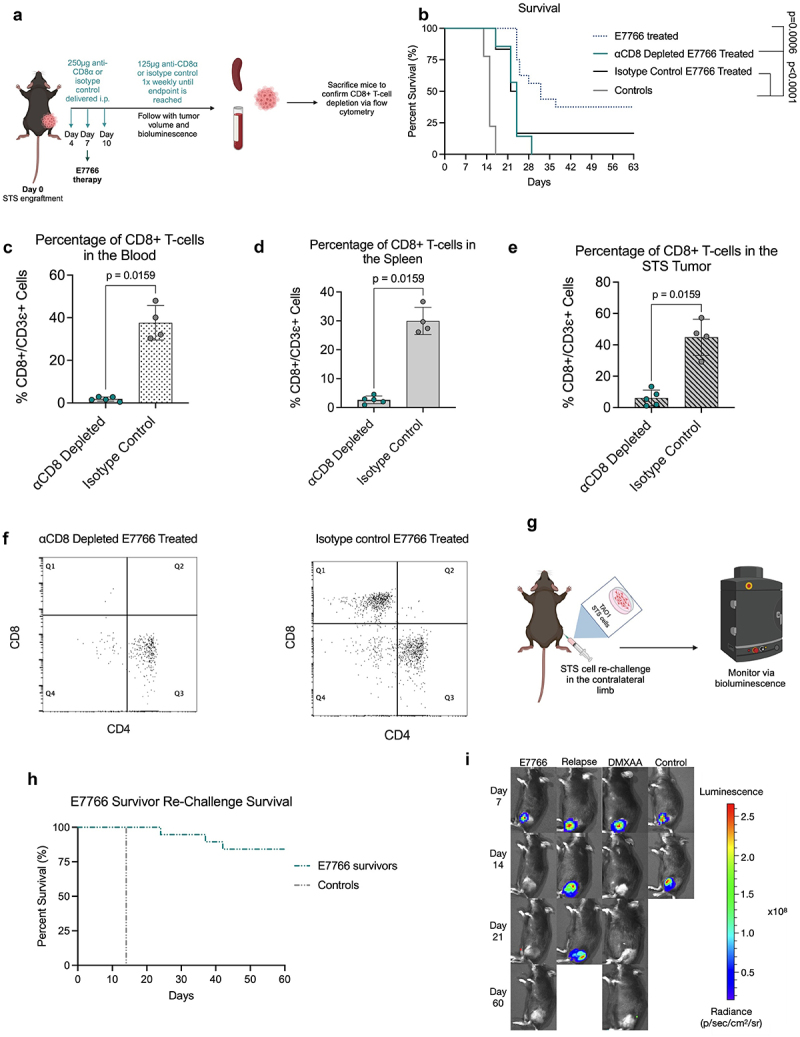

KP sarcoma clearance is dependent on CD8+ T-cells and induces a memory response to tumor rechallenge following E7766 therapy

To assess the importance of CD8+ T-cells in exerting an anti-tumor response following E7766 therapy, CD8+ T-cell depletions were performed in concert with E7766 treatment (Figure 4a). After CD8+ T-cell depletion, none of the mice were able to eradicate their primary STS tumors (Figure 4b). CD8+ T-cell depletion was confirmed via flow cytometry of blood, spleens, and tumors (Figure 4c-f). These results indicate that CD8+ T-cells are critical contributors to tumor clearance following E7766 therapy. As E7766 therapy results in durable CD8+ T-cell dependent tumor clearance, we sought to establish whether survivors of E7766 monotherapy develop protection against contralateral limb re-challenge to determine if protection against disease would occur at site distant from that of the initial tumor engraftment (Figure 4g). As with DMXAA administration, the majority of E7766 survivors that were re-challenged were able to rejected engraftment. This indicated that survivors of STING agonist therapy had developed long-lasting protection against KP STS malignancy (87.5%, Figure 4h,i).

Figure 4.

E7766 induced KP tumor clearance is CD8 T lymphocyte dependent and results in systemic protection against tumor rechallenge.a. Schematic of CD8+ T-cell depletion protocol. b. Survival of E7766 treated mice under CD8+ T-cell depleted or non-depleted states (log rank Mantel-Cox test). c-e. Proportion of CD8+ T-cells in the blood (c), spleen (d), and tumor (e), following STING agonist treatment as a percentage of CD3ε+ cells. f. Dot plots of flow cytometry samples in the depleted or undepleted condition depicting CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations. g. Schematic of KP STS re-challenge in STING agonist induced survivors created with BioRender.com. h. Kaplan-Meier survival plots of survivor mice re-challenged with KP STS (n=3–24 mice per condition. I. Tumor bioluminescence Images of survivor mice following STS re-challenge from days 7–60. Each mouse image is a representative animal from each group (Mann-Whitney U test, n=5–8 mice per condition). The relapse group is specific to mice from the E7766 treatment condition that have relapsed tumors.

STING therapy and anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy are additive in therapeutic effect

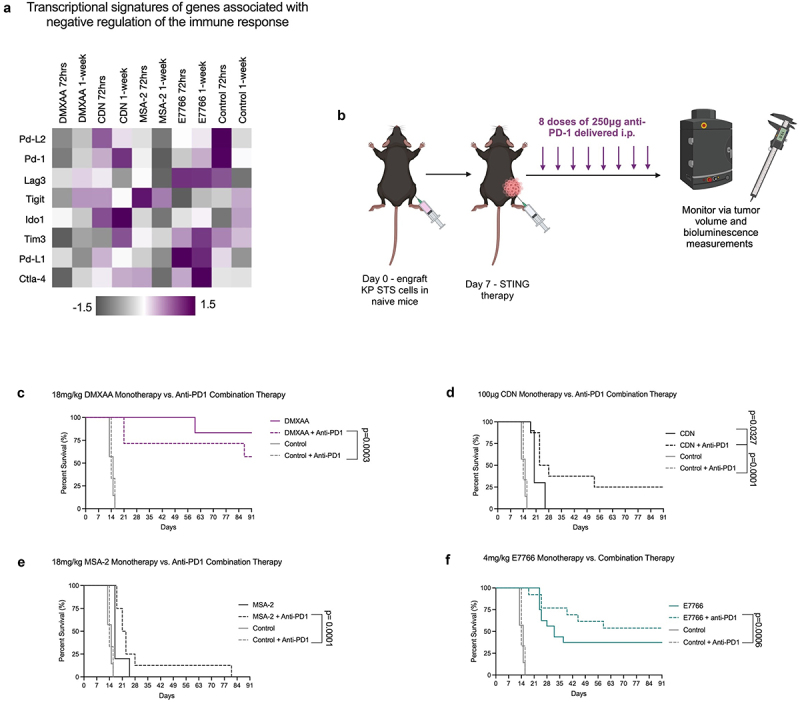

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy has revolutionized treatment outcomes for patients with various types of cancer. Presently, STS patients have experienced limited clinical benefit from ICB monotherapy.5,6 Transcriptomic phenotyping of STING treated STS tumors 1-week following therapy revealed that many negative regulators of the immune system, including Pd-1, and its ligands Pd-L1 and Pd-L2 (Figure 5a), were enriched upon treatment with CDN and E7766. Therefore, we sought to determine whether STING agonist therapy (DMXAA, CDN, MSA-2, or E7766) could synergize with anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

Figure 5.

E7766 survivors are protected against KP STS re-challenge and STING therapy coupled with anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy is additive. a. Transcriptomic profiling of genes associated with negative regulation anti-tumor immunity. b. Schematic of anti-PD-1 + STING combination therapy dosing schedule created with BioRender.com. c. Overall survival of mice treated with DMXAA, anti-PD-1, or in combination. d. Overall survival of mice treated with CDN, anti-PD-1, or CDN + anti-PD-1. e. Overall survival of mice treated with MSA-2, MSA-2 + anti-PD-1, or anti-PD-1. f. Overall survival of mice treated with E7766, E7766 + anti-PD-1, or anti-PD-1. (log-rank Mantel-Cox tests n= 5–16 mice per group). Control and anti-PD-1 monotherapy conditions are repeated in figures c-f.

To investigate this combinatorial strategy, STING agonist therapy (DMXAA, CDN, MSA-2, or E7766) was administered alongside anti-PD-1 according to Figure 5b. As a monotherapy, KP STS tumors do not respond to anti-PD-1.16 Durable tumor clearance was observed in 27% of the CDN+anti-PD-1 combination therapy group compared to the CDN monotherapy and anti-PD-1 monotherapy (Figure 5d). Additionally, survival frequencies increased in the E7766+anti-PD-1 combination therapy group, with 57% of mice in this condition eradicating their STS tumors. Taken together, these results show that STING agonist therapy demonstrates an additive effect when coupled with anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade in the context of CDN specifically (Figure 5f). For both DMXAA and MSA-2, the combination therapy strategy significantly extended survival time relative to the anti-PD-1 monotherapy, but these survival extensions were not significant as compared to CDN or DMXAA monotherapies (Figure 5c,e).

STING agonist therapy induces KP tumor clearance that is independent of tumor cell intrinsic STING protein expression yet reliant on host cell STING expression

As a mechanism of evading the immune system’s ability to identify and kill cancer, cancer cells may downregulate STING expression, or show dysfunctional STING pathway signaling.33 However, it is unclear if STING expression and signaling in tumor cells is needed for their clearance following STING agonist therapy. Thus, we sought to determine if the therapeutic outcomes, that occur following STING agonist therapy were dependent on the presence of STING in malignant versus host cell compartments of the TME.

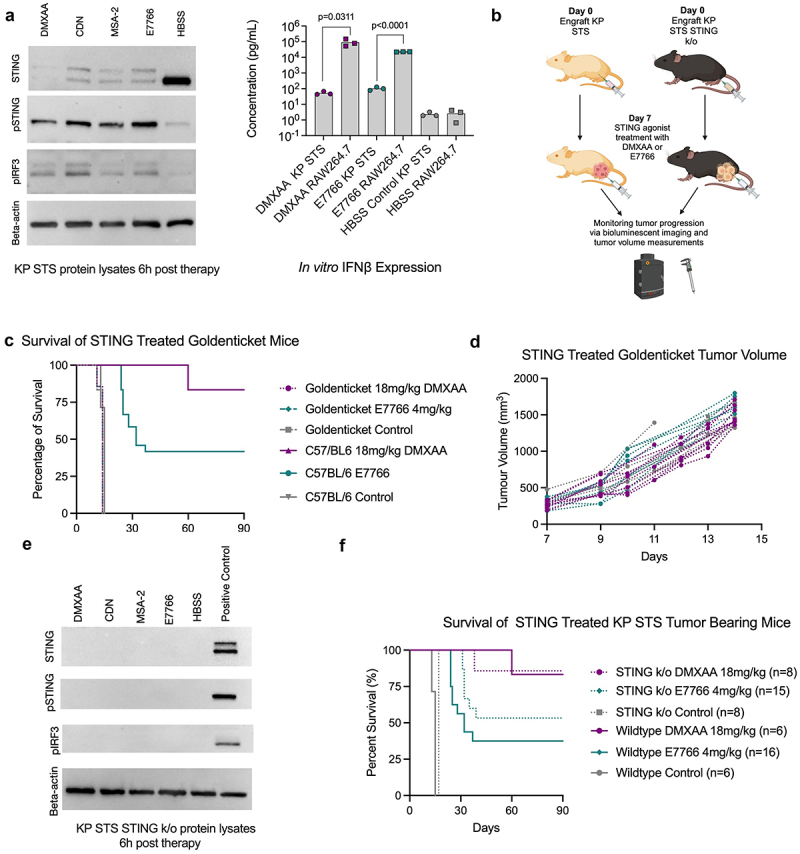

First, we confirmed that our KP STS cell line is responsive to STING agonists by demonstrating that treatment with equimolar amounts of DMXAA, CDN, MSA-2, and E7766 lead to phosphorylation of STING and IRF3 (Figure 6a). Also, IFNβ was detected in the supernatants of E7766 and DMXAA treated KP STS cells, although IFNβ concentrations were significantly lower compared to RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells, suggesting less robust activation of the STING pathway in KP STS cells.

Figure 6.

STING expression in host cells, but not tumor cells, is required for STS clearance following STING agonist therapy. a. Immunoblot showing expression of STING (33-35kDa), phosphorylated STING (pSTING) (41kDa), and phosphorylated IRF3 (pIRF3) (45kDa), from the protein lysates of STING agonist treated RAW 264.7 cells and supernatant cytokine concentrations of KP cells and RAW 264.7 for IFNβ (multiple Mann-Whitney U tests comparing IFNβ expression of DMXAA, E7766, and HBSS control treated KP and RAW 264.7 cells, n=3 per condition). b. Schematic of KP STS cell line engraftment on day 0, i.T. STING treatment on day 7, and subsequent monitoring of goldenticket mice and C57BL/6 mice over time via bioluminescence imaging and tumor volume measurements created with Biorender.com. c. Overall survival of KP STS bearing mice treated i.T. With 4 mg/kg E7766, 18 mg/kg DMXAA, or control (n=6–16 per group). d. Tumor volume measurements of STING treated goldenticket mice over time. e. Western blot showing expression of STING, phosphorylated STING (pSTING), and phosphorylated IRF3 (pIRF3) from the protein lysates of STING treated KP STS cells. f. Overall survival of KP STING−/− bearing mice and KP wildtype tumor bearing mice following STING treatment and tumor volume, respectively.

To assess whether STING signaling by KP STS cells alone can induce tumor clearance, KP STS cells were engrafted in Goldenticket mice and treated with DMXAA or E7766 according to the schematic in Figure 6b. Goldenticket mice do not express a functional STING protein.34 We found that E7766 and DMXAA were no longer able to elicit tumor clearance when KP STS tumors were engrafted in Goldenticket mice. Although STING signaling and subsequent type I interferon production in KP STS cells is possible, it was insufficient to promote a therapeutic response in the absence of nonmalignant host cell STING expression (Figure 6c,d). To examine this further, we evaluated the consequences of ablating STING expression in KP STS cells on survival outcomes from STING therapy with DMXAA and E7766. To accomplish this, we used CRISPR Cas9 technology to engineer a KP STS cell line in which the Sting1 gene was knocked out via single nucleotide deletion resulting in a pre-mature stop codon. Following confirmation that this cell line lacked STING protein expression (Figure 6e), we engrafted 100,000 KP STS STING k/o cells in the hindlimbs of C57BL/6 mice. One week later, DMXAA or E7766 STING therapy was administered i.t. In this case, mice bearing KP STING k/o tumors were equally responsive to STING agonist treatment as wild-type controls (Figure 6f). Taken together, these results demonstrated the efficacy of STING agonist treatment was dependent on host cell STING expression but not tumor cell STING expression.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously compare the anti-tumor effects of multiple clinically relevant STING agonists in a preclinical model of a poorly immunogenic solid tumor. Of the translational STING agonists evaluated, only E7766 reliably induced tumor clearance at various doses, while CDN and MSA-2 failed to do so. As most STS are extremity-based, these malignancies are anatomically amenable to intra-lesional immune modulating therapies, such as STING agonism, thus this data is clinically important.

Immune landscapes of STING agonist treated STS tumors were assessed using flow cytometry and transcriptomics, revealing that E7766 is able to stimulate significant immunogenic changes in both lymphocyte and myeloid compartments of the STS TME. Notably, there was a significant increase in CD3ε+ and CD8+ T-cells infiltrating the TME, in addition to significant increases in anti-tumor CD80+ macrophages with a reduction in CD206+ macrophages. Clinically, the TME of STS demonstrate an immunologically suppressed phenotype. Together, the data suggests that STING immunotherapy with E7766 shifts the immune landscape of the murine KP STS tumors toward a more inflamed, immunogenic phenotype, perhaps allowing effective tumor clearance. In alignment with these data, we found that STS-bearing mice treated with E7766 were unable to mount an anti-tumor response in the absence of CD8+ T-cells. These findings are consistent with previous work assessing DMXAA mediated STS tumor clearance in RAG2−/− mice where, tumor clearance was abrogated.32

Recent studies have shown that radiotherapy can synergize with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 leading to increased progression free survival in sarcoma.35 It is known that radiation can activate a type I interferon response as a result of DNA damage, thus indirectly activating the STING pathway and other pattern recognition receptors.36–38 Additionally, anti-PD-1 has been FDA approved for alveolar soft part sarcoma,4 an ultra-rare STS subtype, which is notable as both Pd-1 (PD-1) and Pd-L1 (PD-L1) are upregulated in the TME of the murine STING agonist treated KP STS tumors. Therefore, we explored the possibility that STING agonist immunotherapy could sensitize tumors to anti-PD-1 in the KP model. As radiotherapy can induce DNA damage and subsequent activation of a type I interferon response, we sought to determine if STING activation could sensitize our murine model to anti-PD-1 treatment. Previous work completed by our group and others has shown that the murine KP STS model (spontaneous or engrafted) is resistant to anti-PD-1 monotherapy.16,39 However, we found that co-administration of STING agonists and checkpoint blockade therapy led to significant improvements in survival. This was especially evident for CDN+anti-PD-1 combination therapy, resulting in a significant improvement in tumor eradication as compared to CDN monotherapy on its own, which has no anti-tumor effect in the KP model. Although not significant, an increase in survival was also noted in the E7766+anti-PD-1 condition. Transcriptomic data demonstrated that each STING agonist may activate the expression of different negative regulators of the immune response, possibly providing opportunities to explore other ICB combination therapies targeting those markers. For example, in addition to Pd-1, E7766 also upregulated Lag3, Tim3, and Ctla-4. As monotherapies, some of these the STING agonists we tested are currently under investigation in clinical trials.40 These compounds may be used to augment different treatment regimens.

As a mechanism of evading the immune system’s ability to identify and kill cancer, some cancer cells downregulate STING expression or exhibit dysfunctional STING pathway signaling.33 Thus, STING expression, or its lack thereof, can exist on a spectrum in both murine and human cancers and may be dependent on disease progression status.41 A criticism of STING activating cancer immunotherapy is that many cancer cells evolve a dysfunctional cGAS-STING-IFN signaling axis.42,43 Further, it is unclear if STING signaling in cancer cells is tumor promoting or tumor inhibiting. Some studies have demonstrated that some cancers with impaired cGAS or STING have reduced type I interferon production which can promote tumorigenesis.42,43 Further work investigating human melanoma cell lines showed that some cell lines could participate in STING signaling thereby increasing the tumor cell antigenicity and subsequent sensitization to lymphocyte mediated killing due to MHC-I upregulation.44 In contrast, evidence has emerged revealing that chronic STING activation in malignant cells resulting from DNA damage can stimulate the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, thus promoting tumorigenesis, and increase rates of metastasis.44–46

Using models of host and tumor cell intrinsic STING deficiency, we have shown that in KP STS tumors, STING agonists must engage signaling in nonmalignant host/stromal cells rather than cancer cells. Although others have shown that in the absence of host STING expression STING agonist mediated tumor clearance is inhibited,22 our data expands on these observations showing that STING functionality in cancer cells, and specifically in KP STS, is not necessary for tumor clearance. Thus, STING agonist mediated tumor clearance in our STS model is dependent exclusively on host cell STING. This is supported by recent work demonstrating that cGAS-derived cGAMP can be transferred from cancer cells to dendritic cells within the TME via gap junctions, further indicating that STING activation in cancer cells themselves is not needed to produce an anti-tumor response.47 Further, it is known that inactivating mutations in p53 is the most ubiquitous mutation in human STS,48 and research has shown in several murine and human cancer cell lines, with p53 knockdown suppressed the function of TBK1, thereby reducing STING induced type I interferon production.49 Our findings are in agreement, given that our KP STS tumors contain a Trp53-/- mutation. Thus, this work suggests that STING immunotherapy may still be a viable therapeutic candidate regardless of STING or p53 status of tumor cells, which is relevant for sarcoma and other solid cancers. Further delineations of which nonmalignant host cell types are involved in STING signaling in the STS TME will be critical for predicting therapeutic responses to STING therapy and potentially developing cell type-specific STING agonist delivery systems to reduce toxicity are currently being explored by our group and others. Given that myeloid cells are dominant immune lineage in the TME of many STS, and myeloid cells mount a potent IFN response to STING agonism23,50 it is reasonable to believe that one or more of these cell types could be critically involved in determining the response to STING agonist therapy.

In summary, our findings reveal that the translational STING agonist, E7766, may be a promising STING agonist for further investigation in sarcoma clinical trials. Our results highlight the ability of intra-tumoral E7766 injection to support immunogenic TME remodeling of murine sarcomas, facilitating immune-mediated tumor clearance. Importantly, in our model the anti-tumor properties of STING agonist therapy are independent of tumor STING expression status. Thus, providing impetus for pursuing STING agonist immunotherapy in combination with other treatment modalities such as radiation, surgery, or anti-PD1 in the therapy of STS.

Supplementary Material

Appendix.

Table A1.

Flow cytometry antibodies.

| Vendor | Reagent name | Catalogue Number |

|---|---|---|

| Biolegend | Zombie Aqua Fixable viability kit | 423102 |

| Biolegend | Zombie NIRTM Fixable viability kit | 423105 |

| Biolegend | FITC anti-mouse CD19 | 115506 |

| Biolegend | PerCP/Cyanine 5.5 anti-mouse CD8a | 100733 |

| Biolegend | PE anti-mouse CD4 | 100512 |

| Biolegend | Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse CD3ε | 155609 |

| Biolegend | Brilliant Violet 605 anti-mouse I-A/I-E | 107639 |

| Biolegend | PE anti-mouse/human CD11b | 101207 |

| Biolegend | Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse CD11c | 117314 |

| Biolegend | PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD206 (MMR) | 141719 |

| Biolegend | Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse F4/80 antibody | 123122 |

| Biolegend | APC/Fire 750 anti-mouse CD45 antibody Clone 30F11 | 103154 |

| Biolegend | TruStain FcX PLUS/anti-mouse CD16/32 | 156604 |

Table A2.

Immune cell phenotyping with flow cytometry.

| Cell type | Flow cytometry gating definition |

|---|---|

| Live cells | Zombie aqua - |

| Hematopoietic cells | Zombie aqua -/CD45+ |

| T lymphocytes | Zombie aqua -/CD45+/CD3ε + |

| CD8+ T lymphocytes | Zombie aqua -/CD45+/CD3ε +/CD4-/CD8+ |

| CD4+ T lymphocytes | Zombie aqua -/CD45+/CD3ε CD8-/CD4+ |

| Macrophages | Zombie aqua -/CD45+/CD11b+/F/480+ |

| CD80+ macrophages | Zombie aqua -/CD45+/CD11b+/F/480+/CD80+ |

| CD206+ macrophages | Zombie aqua -/CD45+/CD11b+/F/480+/CD206+ |

| Antigen presenting cells | Zombie aqua -/CD45+/MHC-II+ |

Funding Statement

This research conducted in this study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research under grant number [202010PJT-452897].

Disclosure statement

The authors of this manuscript do not have any relevant competing interests or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

- CCL2

C-C motif ligand 2

- CCL5

C-C motif ligand 5

- cGAS

cyclic GMP-AMP synthase

- CXCL10

chemokine ligand 10

- CXCL9

chemokine ligand 9

- DMXAA

5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- i.m.

intramuscular

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.t.

intratumoral

- ICB

immune checkpoint blockade

- IFNβ

interferon beta

- IRF3

interferon regulatory factor 3

- KRAS

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PD-1

programmed death-1

- PD-L1

programmed death-ligand 1

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- RPMI

Roswell park memorial institute

- STING

stimulator of interferon genes

- STS

soft tissue sarcoma

- TBK1

tank binding kinase 1

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- TIL

tumor infiltrating lymphocyte

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- Trp53

tumor protein p53

Data availability statement

All data in this manuscript can be made available upon reasonable request. Please e-mail the corresponding author, Dr. Monument (http://mjmonume@ucalgary.ca).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2025.2534912

References

- 1.Fletcher C, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F.. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone: WHO classification of tumours. Vol. 5. IARC, World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blank A, Fice MP. Challenges in the management of complex soft-tissue sarcoma clinical scenarios. jaaos-J Am Acad Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2024;32(3):e115–19. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casali P, Jost L, Sleijfer S, Verweij J, Blay J-Y, Group EGW. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:ii89–ii93. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergsma EJ, Elgawly M, Mancuso D, Orr R, Vuskovich T, Seligson ND. Atezolizumab as the first systemic therapy approved for alveolar soft part sarcoma. Ann Pharmacother. 2024;58(4):407–415. doi: 10.1177/10600280231187421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Angelo SP, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, Atkins J, Milhem MM, Jahagirdar BN, Antonescu CR, Horvath E, Tap WD, Schwartz GK. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab treatment for metastatic sarcoma (alliance A091401): two open-label, non-comparative, randomised, phase 2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(3):416–426. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tawbi HA, Burgess M, Bolejack V, Van Tine BA, Schuetze SM, Hu J, D’Angelo S, Attia S, Riedel RF, Priebat DA. Pembrolizumab in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma and bone sarcoma (SARC028): a multicentre, two-cohort, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(11):1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30624-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakravarthy A, Khan L, Bensler NP, Bose P, De Carvalho DD. TGF-β-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4692. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06654-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petitprez F, de Reyniès A, Keung EZ, Chen T-W-W, Sun C-M, Calderaro J, Jeng Y-M, Hsiao L-P, Lacroix L, Bougoüin A. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature. 2020;577(7791):556–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1906-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorbye SW, Kilvaer T, Valkov A, Donnem T, Smeland E, Al-Shibli K, Bremnes RM, Busund L-T, Câmara NOS. Prognostic impact of lymphocytes in soft tissue sarcomas. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(1):e14611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jumaniyazova E, Lokhonina A, Dzhalilova D, Kosyreva A, Fatkhudinov T. Immune cells in the tumor microenvironment of soft tissue sarcomas. Cancers. 2023;15(24):5760. doi: 10.3390/cancers15245760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dancsok AR, Gao D, Lee AF, Steigen SE, Blay J-Y, Thomas DM, Maki RG, Nielsen TO, Demicco EG. Tumor-associated macrophages and macrophage-related immune checkpoint expression in sarcomas. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1747340. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1747340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiwara T, Healey J, Ogura K, Yoshida A, Kondo H, Hata T, Kure M, Tazawa H, Nakata E, Kunisada T. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in sarcomas. Cancers. 2021;13(5):1086. doi: 10.3390/cancers13051086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood GE, Meyer C, Petitprez F, D’Angelo SP. Immunotherapy in sarcoma: current data and promising strategies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2024;44(3):e432234. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_432234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sondak VK, Smalley KS, Kudchadkar R, Grippon S, Kirkpatrick P. Ipilimumab. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(6):411–413. doi: 10.1038/nrd3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez WR, Scherer A, McGivney GR, Brockman QR, Knepper-Adrian V, Laverty EA, Roughton GA, Dodd RD. Divergent immune landscapes of primary and syngeneic kras-driven mouse tumor models. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80216-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hildebrand KM, Singla AK, McNeil R, Marritt KL, Hildebrand KN, Zemp F, Rajwani J, Itani D, Bose P, Mahoney DJ. et al. The kras G12D; Trp53 fl/fl murine model of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma is macrophage dense, lymphocyte poor, and resistant to immune checkpoint blockade. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(7):e0253864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirsch DG, Dinulescu DM, Miller JB, Grimm J, Santiago PM, Young NP, Nielsen GP, Quade BJ, Chaber CJ, Schultz CP. A spatially and temporally restricted mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Nat Med. 2007;13(8):992–997. doi: 10.1038/nm1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber GN. STING: infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(12):760–770. doi: 10.1038/nri3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decout A, Katz JD, Venkatraman S, Ablasser A. The cGAS–STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(9):548–569. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corrales L, McWhirter SM, Dubensky TW, Gajewski TF. The host STING pathway at the interface of cancer and immunity. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(7):2404–2411. doi: 10.1172/JCI86892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sivick KE, Desbien AL, Glickman LH, Reiner GL, Corrales L, Surh NH, Hudson TE, Vu UT, Francica BJ, Banda T, et al. Magnitude of therapeutic STING activation determines CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep. 2018;25(11):3074–3085. e3075. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corrales L, Glickman LH, McWhirter SM, Kanne DB, Sivick KE, Katibah GE, Woo S-R, Lemmens E, Banda T, Leong JJ. Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. Cell Rep. 2015;11(7):1018–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downey CM, Aghaei M, Schwendener RA, Jirik FR, Kanthou C. DMXAA causes tumor site-specific vascular disruption in murine non-small cell lung cancer, and like the endogenous non-canonical cyclic dinucleotide STING agonist, 2′ 3′-cGAMP, induces M2 macrophage repolarization. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(6):e99988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss JM, Guérin MV, Regnier F, Renault G, Galy-Fauroux I, Vimeux L, Feuillet V, Peranzoni E, Thoreau M, Trautmann A. The STING agonist DMXAA triggers a cooperation between T lymphocytes and myeloid cells that leads to tumor regression. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(10):e1346765. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1346765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meric-Bernstam F, Sweis RF, Hodi FS, Messersmith WA, Andtbacka RH, Ingham M, Lewis N, Chen X, Pelletier M, Chen X. Phase I dose-escalation trial of MIW815 (ADU-S100), an intratumoral STING agonist, in patients with advanced/metastatic solid tumors or lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(4):677–688. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meric-Bernstam F, Sweis RF, Kasper S, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Dummer R, Stradella A, Long GV, Spreafico A, Shimizu T. Combination of the STING agonist MIW815 (ADU-S100) and PD-1 inhibitor spartalizumab in advanced/metastatic solid tumors or lymphomas: an open-label, multicenter, phase Ib study. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(1):110–121. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DS, Endo A, Fang FG, Huang KC, Bao X, Choi HW, Majumder U, Shen YY, Mathieu S, Zhu X. E7766, a macrocycle‐bridged stimulator of interferon genes (STING) agonist with potent Pan‐Genotypic activity. ChemMedchem. 2021;16(11):1741–1744. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan B-S, Perera SA, Piesvaux JA, Presland JP, Schroeder GK, Cumming JN, Trotter BW, Altman MD, Buevich AV, Cash B. An orally available non-nucleotide STING agonist with antitumor activity. Science. 2020;369(6506). doi: 10.1126/science.aba6098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrington K, Brody J, Ingham M, Strauss J, Cemerski S, Wang M, Tse A, Khilnani A, Marabelle A, Golan T. Preliminary results of the first-in-human (FIH) study of MK-1454, an agonist of stimulator of interferon genes (STING), as monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab (pembro) in patients with advanced solid tumors or lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2018;29, viii712):viii712. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy424.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hines JB, Kacew AJ, Sweis RF. The development of STING agonists and emerging results as a cancer immunotherapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25(3):189–199. doi: 10.1007/s11912-023-01361-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang K-C, Endo A, McGrath S, Chandra D, Wu J, Kim D-S, Albu D, Ingersoll C, Tendyke K, Loiacono K. Discovery and characterization of E7766, a novel macrocycle-bridged STING agonist with pan-genotypic and potent antitumor activity through intravesical and intratumoral administration. MDPI, AACR; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marritt KL, Hildebrand KM, Hildebrand KN, Singla AK, Zemp FJ, Mahoney DJ, Jirik FR, Monument MJ. Intratumoral STING activation causes durable immunogenic tumor eradication in the KP soft tissue sarcoma model. Front Immunol. 2022;13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1087991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sokolowska O, Nowis D. STING signaling in cancer cells: important or not? Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis. 2018;66(2):125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00005-017-0481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauer J-D, Sotelo-Troha K, Von Moltke J, Monroe KM, Rae CS, Brubaker SW, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Woodward JJ, Portnoy DA, et al. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of sting in the in vivo interferon response to listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect Immun. 2011;79(2):688–694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00999-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mowery YM, Ballman KV, Hong AM, Schuetze SM, Wagner AJ, Monga V, Heise RS, Attia S, Choy E, Burgess MA. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab, radiation therapy, and surgery versus radiation therapy and surgery for stage III soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity (SU2C-SARC032): an open-label, randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2024;404(10467):2053–2064. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01812-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang QS, Hayes JP, Gondi V, Pollack SM. Immunotherapy and radiotherapy combinations for sarcoma. In 2. (Elsevier), pp. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2024;34(2):229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2023.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colangelo NW, Gerber NK, Vatner RE, Cooper BT. Harnessing the cGAS-STING pathway to potentiate radiation therapy: current approaches and future directions. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1383000. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1383000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu R, Zhu B, Chen D. Type I interferon-mediated tumor immunity and its role in immunotherapy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(3):191. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04219-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel R, Mowery YM, Qi Y, Bassil AM, Holbrook M, Xu ES, Hong CS, Himes JE, Williams NT, Everitt J. Neoadjuvant radiation therapy and surgery improves metastasis-free survival over surgery alone in a primary mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023;22(1):112–122. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spalato-Ceruso M, Ghazzi NE, Italiano A. New strategies in soft tissue sarcoma treatment. J Hematol & Oncol. 2024;17(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s13045-024-01580-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng H, Wu L, Xiao Q, Meng X, Hafiz A, Yan Q, Lu R, Cao J. Epigenetically suppressed tumor cell intrinsic STING promotes tumor immune escape. Biomed & Pharmacother. 2023;157:114033. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia T, Konno H, Ahn J, Barber GN. Deregulation of STING signaling in colorectal carcinoma constrains DNA damage responses and correlates with tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2016;14(2):282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konno H, Yamauchi S, Berglund A, Putney RM, Mulé JJ, Barber GN. Suppression of STING signaling through epigenetic silencing and missense mutation impedes DNA damage mediated cytokine production. Oncogene. 2018;37(15):2037–2051. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0120-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Falahat R, Perez-Villarroel P, Mailloux A, Zhu G, Pilon-Thomas S, Barber G, Mulé J. STING signaling in melanoma cells shapes antigenicity and can promote antitumor T-cell activity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(11):1837–1848. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He L, Xiao X, Yang X, Zhang Z, Wu L, Liu Z. STING signaling in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy: a friend or foe? Cancer Lett. 2017;402:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Q, Boire A, Jin X, Valiente M, Er EE, Lopez-Soto A, Jacob S, Patwa L, Shah R, Xu, et al. Carcinoma–astrocyte gap junctions promote brain metastasis by cGAMP transfer. Nature. 2016;533(7604):493–498. doi: 10.1038/nature18268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schadt L, Sparano C, Schweiger NA, Silina K, Cecconi V, Lucchiari G, Yagita H, Guggisberg E, Saba S, Nascakova Z, et al. Cancer-cell-intrinsic cGAS expression mediates tumor immunogenicity. Cell Rep. 2019;29(5):1236–1248. e1237. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nacev BA, Sanchez-Vega F, Smith SA, Antonescu CR, Rosenbaum E, Shi H, Tang C, Socci ND, Rana S, Gularte-Mérida R. Clinical sequencing of soft tissue and bone sarcomas delineates diverse genomic landscapes and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3405. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30453-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghosh M, Saha S, Bettke J, Nagar R, Parrales A, Iwakuma T, van der Velden AW, Martinez LA. Mutant p53 suppresses innate immune signaling to promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(4):494–508. e495. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohkuri T, Kosaka A, Nagato T, Kobayashi H. Effects of STING stimulation on macrophages: STING agonists polarize into “classically” or “alternatively” activated macrophages? Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2018;14(2):285–287. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1395995query. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data in this manuscript can be made available upon reasonable request. Please e-mail the corresponding author, Dr. Monument (http://mjmonume@ucalgary.ca).