Abstract

Cells regulate the expression of cell cycle-related genes, including cyclins essential for mitosis, through the transcriptional activity of the positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb), a complex comprising CDK9, cyclin T, and transcription factors. P-TEFb cooperates with CDK7 to activate RNA polymerase. In response to DNA stress, the cell cycle shifts from mitosis to repair, triggering cell cycle arrest and the activation of DNA repair genes. This tight coordination between transcription, cell cycle progression, and DNA stress response is crucial for maintaining cellular integrity. Cyclin-dependent kinases CDK7 and CDK9 are central to both transcription and cell cycle regulation. CDK7 functions as the CDK-activating kinase (CAK), essential for activating other CDKs, while CDK9 acts as a critical integrator of signals from both the cell cycle and transcriptional machinery. This review elucidates the mechanisms by which CDK7 and CDK9 regulate the mitotic process and cell cycle checkpoints, emphasizing their roles in balancing cell growth, homeostasis, and DNA repair through transcriptional control.

KEYWORDS: Cell cycle, transcription, CDK7, CDK9

Introduction

Interconnection between DNA damage and cell cycle checkpoints

DNA damage checkpoints and cell cycle checkpoints are interconnected mechanisms that maintain genomic stability [1]. DNA damage checkpoints specifically detect DNA damage and pause the cell cycle to allow for repair. They involve proteins like ATM [2], ATR [3], CHK1 [4], and CHK2 [5], which signal the presence of damage and activate repair pathways or trigger apoptosis if repair is unsuccessful. Cell cycle checkpoints are broader control mechanisms that regulate progression through the cell cycle stages (G1, S, G2, and M). DNA damage checkpoints are a subset of cell cycle checkpoints activated by DNA damage [6,7], ensuring that cells do not replicate damaged DNA, thus preventing mutations and cancer development.

ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ATM and Rad3-related) in cell cycle checkpoint regulation

DNA damage triggers checkpoints at critical stages of the cell cycle: G1/S, G2/M, and intra-S-phase. These checkpoints detect damage and halt progression to allow for repair. The process involves sensor proteins like ATM (Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated) at the G1/S checkpoint, which detects double-strand breaks and activates CHK2 [8]. ATR (ATM and Rad3-related) is activated during intra-S-phase to sense replication stress and activates CHK1 [9]. Both ATM and ATR also function at the G2/M checkpoint, activating CHK1 and CHK2 to inhibit Cdc25 phosphatases and stabilize p53 [10,11]. These kinases phosphorylate proteins like p53, resulting in cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, or apoptosis if repair fails, maintaining genomic stability by preventing the replication of damaged DNA, thereby protecting against mutations and cancer development.

Coordination of DNA damage checkpoints with DNA repair mechanisms

DNA damage checkpoints coordinate with specific DNA repair mechanisms through key molecules like ATM and ATR. ATM is primarily activated by double-strand breaks and triggers repair via Homologous Recombination (HR) [12] or Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) [13], involving proteins such as BRCA1 [14], RAD51 [15] 53BP1 [16], and DNA-PKcs [17]. ATR responds to single-strand damage and replication stress, facilitating Base Excision Repair (BER) and Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER) by activating proteins like CHK1 [18]. Mismatch Repair (MMR), indirectly linked to ATR, handles replication errors [18], demonstrating how checkpoints ensure genomic stability by detecting damage and initiating proper repair pathways.

Transcription factors in DNA damage response and cell cycle regulation

Forkhead Box (FOX) proteins, particularly FOXO and FOXM1, play distinct roles in maintaining genomic integrity [19]. FOXO proteins, like FOXO3, are activated under stress conditions and promote the expression of genes such as p27Kip1 [20] and p21Cip1 [21], which is the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors and halt the cell cycle at the G1 phase [22], allowing for DNA repair or apoptosis. FOXM1, conversely, drives cell cycle progression by promoting the expression of genes necessary for the G2/M transition [23], such as Cyclin B1 [24] and PLK1 [25], ensuring proper mitosis and DNA damage repair.

p53, a central regulator, is stabilized upon DNA damage and activates genes involved in cell cycle arrest, DNA repair (e.g. GADD45), and apoptosis (e.g. BAX) [26]. At the G1/S checkpoint, p53 prevents cells with DNA damage from entering the S phase [27]. The release of E2F transcription factors, regulated by the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein degradation, is crucial for the production of cyclin E, which facilitates the G1/S transition initiates and DNA synthesis [28]; upon DNA damage, Rb remains hypophosphorylated, sequestering E2F and halting the cell cycle [29]. NF-Y binds to CCAAT motifs in promoters of genes crucial for DNA replication and repair (e.g. Cyclin B1, CDC25C) during the G2/M checkpoint [30,31], ensuring that cells do not enter mitosis with damaged DNA. Overall, these transcription factors coordinate cell cycle checkpoints and DNA damage responses, balancing repair and cell death to maintain genomic stability.

The link between transcription and cell cycle regulation

The cell cycle and transcriptional regulation are tightly interwoven processes, each with a crucial role in cell growth and response to external stimuli. During the G1 phase, cells prepare for DNA synthesis, activating genes vital for growth and function, guided by transcription factors that shape the transcriptional program [32]. As the cell transitions into the S phase, marked by DNA replication, there is an increase in transcriptional activity [33]. This coordination between DNA replication and transcription is crucial for maintaining genomic integrity and providing the necessary resources for cell division [34]. When cells encounter specific stimuli, this balanced process may shift, leading to activation of cell cycle checkpoints [35]. In such situations, the transcriptional profile adapts, switching to a different set of genes that facilitate the cell’s response to these stimuli. This change can involve upregulating genes that manage stress responses, repair mechanisms, or apoptosis, ensuring the cell adapts appropriately to its environment [36,37]. The complex coordination of the cell cycle and transcription is crucial for cell growth, response to external factors, and ensuring cellular integrity and cycle precision. To maintain proper cellular function and genomic integrity, the cell relies on precise control mechanisms that synchronize cell cycle progression with transcriptional activities [38].

Role of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) in coordinating cell cycle progression and transcription

The positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) complex, consisting of a transcription factor, a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), and a cyclin, is responsible for activating RNA polymerase II to facilitate transcription [39]. The Cyclin-Dependent Kinase (CDK) family, composed of 20 unique members, plays a central role in these processes. CDKs such as CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK5, and CDK6 are crucial for regulating different stages of the cell cycle, controlling key checkpoints, and ensuring orderly cell division. In contrast, other CDKs, including CDK7, CDK8, CDK9, CDK10, CDK11, CDK12, CDK13, CDK19, and CDK20, primarily regulate gene expression and transcriptional activities [40,41]. CDKs closely collaborate with transcription factors to control cell cycle progression through specific molecular mechanisms. For exampleCDK2 phosphorylates the transcription factor FOXO1 at serine-249, altering its localization and inhibiting its function, which plays a role in DNA damage-induced apoptosis [42]. CDK4 and CDK6 phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), leading to the release of E2F for DNA synthesis during the G1/S transition [43]. Similarly, CDK1 phosphorylates FOXM1, a key transcription factor that enhances the expression of genes essential for mitosis during the G2/M transition [44].

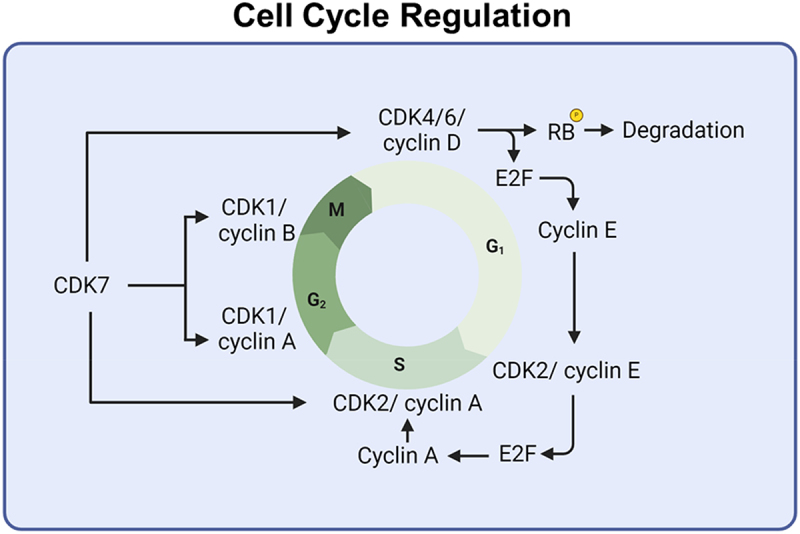

Cyclin proteins intricately regulate specific phases of the cell cycle. In the G1 phase, activator protein 1 (AP1) [45], Ras [46], nuclear factor (NFκB) [47], and Myc [48] induce Cyclin D expression binding with CDK4/6, resulting in the release of the E2F transcription factor following phosphorylating RB for degradation [43]. Additionally, the levels of Myc mRNA and protein are influenced by the activity of CDK9 [49]. E2F then promotes the expression of Cyclin E, thereby preparing the cell for the G1/S transition [50]. Cyclin A/CDK2 activity is elevated in S phase, while Cyclin A interacts with CDK1 during G2 [51]. Subsequently, the CDK1/cyclin A complex activates CDK1/cyclin B via Cdc25 phosphatase, facilitating the G2/M checkpoint and initiating mitosis [52]. In the G2 phase, as cells prepare for division, transcriptional activities are fine-tuned through complex regulatory interactions, ensuring readiness for mitosis [53]. The absence of Mitogen signaling, especially CDK2/cyclin A activity in G2, aids in transitioning the cell from the cycle to the G0 phase [54].

CDK7 and CDK9 are particularly important in regulating gene transcription, especially in response to DNA damage. CDK7, as part of the TFIIH complex, phosphorylates the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II and modulates transcription factors like p53, which are crucial for the DNA damage response [55]. CDK9, a key component of the P-TEFb complex, interacts with transcription factors such as E2F1 and CDKN1C, leading to reduced phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II [56]. Through these interactions, CDK7 and CDK9 coordinate the regulation of the cell cycle and gene expression.

CDK7 acts as CDK activating kinase (CAK) in cell cycle regulation

CDK7 is a kinase with dual roles in cell cycle regulation and transcription [57,58]. Partnering with cyclin H, it forms a complex that phosphorylates CDK1, CDK2, and CDK4/6, thereby influencing the cell cycle [59–61]. CDK7 plays a crucial role in the precise timing of cell cycle events through its activation of multiple CDKs (Figure 1). CDK7 forms active complexes with Cyclin H and Mat1 and is regulated by two phosphorylation sites in its activation segment (T loop) at T170 and S164 [62]. This kinase maintains orderly cell division by regulating CDK4/6 in the G1 phase, CDK2 in the S phase, and CDK1 in the M phase through phosphorylation [60,61]. During the cell cycle, CDK7 phosphorylates CDK4 at Thr172 to promote G1 progression [58]. CDK7 activates CDK2, which, in combination with cyclins E and A, drives the transition from the G1 to the S phase, regulating DNA replication [63]. CDK7 also activates CDK1 by pairing it with cyclin B, which is crucial for the G2 to M transition [64], initiating key mitotic processes such as chromatin condensation and spindle assembly [65]. This highlights CDK7’s essential role in regulating the activity of various CDKs throughout the cell cycle. Additionally, CDK7 phosphorylates RNA polymerase II at Serine-7 during transcription initiation [66].

Figure 1.

CDKs and cyclins orchestrate the cell cycle, with CDK4/6 partnering with cyclin D during the G1 phase, and CDK2 with cyclin E and cyclin a at the G1/S checkpoint and S phase. CDK1 collaborating cyclin a and cyclin B in the G2 phase and checkpoint for M phase.

CDK9’s role in transcriptional regulation

CDK9 is a critical component of the P-TEFb complex, which enhances transcriptional elongation by partnering with cyclin T1 to phosphorylate RNA polymerase II at serine-2 [67]. It also associates with cyclins K [68] and T2 (T2a and T2b) [69], modulating its activation and directing transcription specificity. Inhibition of CDK9 results in prolonged pausing of RNA polymerase near gene promoters [70]. The long non-coding RNA 7SK serves as a negative regulator of CDK9, and its release, triggered by methyltransferase 3 (METTL3) methylation, enables P-TEFb complex formation and transcription [71,72].

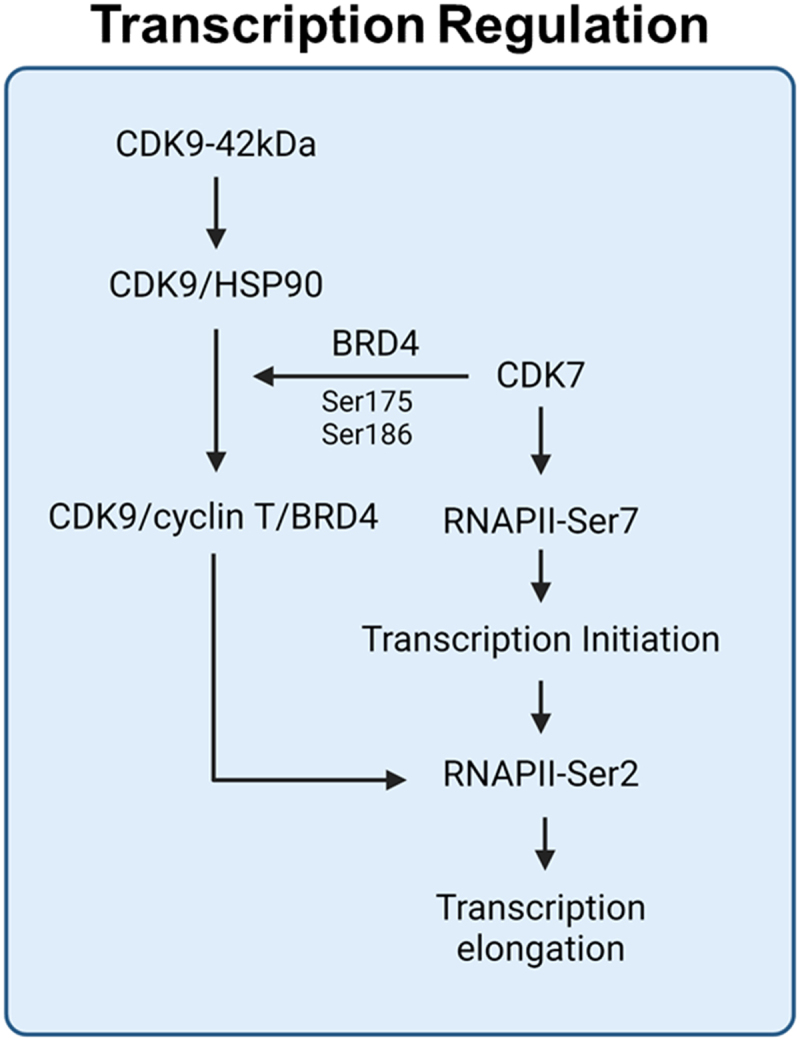

CDK9’s activity and binding interactions are regulated by the post-translational modifications that influence downstream regulation of transcription (Figure 2). Phosphorylation at Thr186 is key for CDK9’s dissociation from HSP90, enabling CDK9 translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus [57]. CDK9 shuttling to the nucleus to bind with cyclin T1 facilitates transcription [73]. Cyclin binding is essential for the functionality of all CDKs. Cyclin T1 [74], cyclin T2 [75], and cyclin K [76] have been identified as partners that interact with CDK9, each regulating specific genes in response to particular conditions. Cyclin T1 regulates CDK9 in the transcriptional CDK9/CycT1 complex, featuring a unique cyclin orientation for substrate specificity, especially for P-TEFb’s targets like RNA Pol II’s CTD heptad repeat, and tailors CDK9’s activation segment for Ser/Thr-Pro motif recognition [74].

Figure 2.

Regulation of CDK9 transcription activity by CDK7.

CDK9 phosphorylation at serine-175 facilitates BRD4 binding, while phosphorylation at serine-186 is associated with HSP90 dissociation [57]. CDK7 activates RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) at serine-7 during transcription initiation [66], and the CDK9/cyclin T/BRD4 complex further phosphorylates RNAPII at serine-2 [67], promoting transcription elongation.

CDK9’s function is also governed by T-loop phosphorylation, which is crucial for its recruitment to specific DNA sites by transcription factors. CDK7, as a CAK, phosphorylates CDK9 at Serine-175 within the T-loop, increasing its affinity for BRD4 without altering its intrinsic kinase activity, thereby activating the P-TEFb complex to initiate RNA transcription [57]. Additionally, Serine-91 phosphorylation on the Androgen Receptor (AR) regulated by CDK1 and CDK9, enhancing AR transactivation [77], associated with castration resistance [78] and clinical outcomes in prostate cancer [79]. This phosphorylation, crucial for gene expression regulation in castration-resistant prostate cancer, indicates a key interaction between AR and CDK9 [80].

CDK9 also interacts with endogenous BRCA1 and BARD1 (BRCA1-associated RING domain 1), facilitated by their RING finger and BRCT domains, and is involved in forming ionizing radiation-induced foci (IRIF) and co-localizing with BRCA1 at DNA damage sites [81], highlighting CDK9’s interaction with specific transcription factors to determine transcription specificity by directing it to precise DNA sites for targeted RNA transcription initiation.

CDK9’s involvement in DNA damage stress response

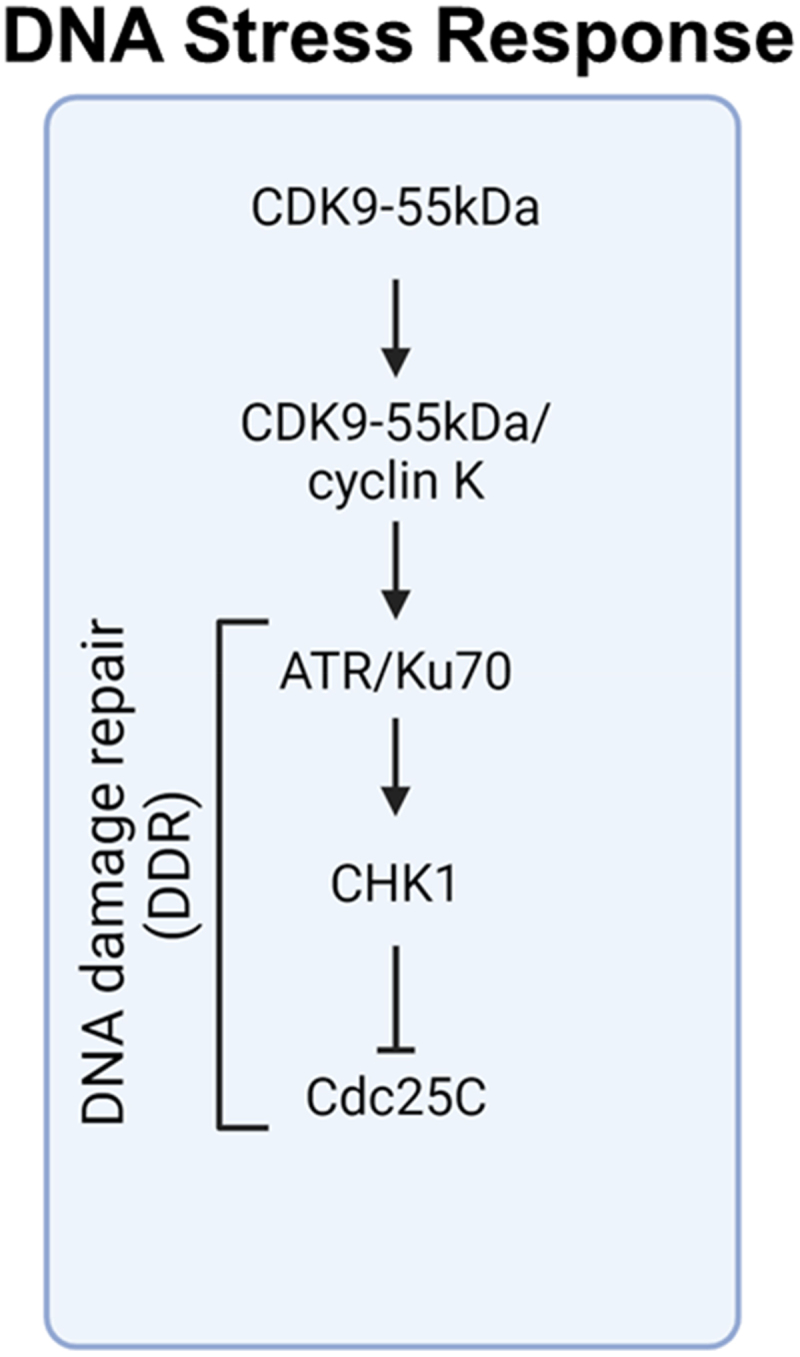

CDK9 depletion elevates γH2AX phosphorylation, disrupting cell cycle recovery during HU or aphidicolin exposure [76]. Cyclin K interacts with CDK9 during the replication stress response, playing a role in DNA damage signaling and aiding in recovery from replication arrest [76]. CDK9/cyclin K has been identified to bind ATR, contributing to the replication stress response [82]. In addition, CDK9 activity is crucial for the replication stress response. Sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) activates CDK9 with deacetylation at lysine 48 in response for HU treatment [83]. The depletion of the 55KDa isoform of CDK9 induces apoptosis and double-strand breaks (DSBs). Notably, the 55KDa isoform rather than the 42KDa isoform CDK9 associates with the Ku70 protein [84]. Moreover, the CDK9/cyclin K complex plays a crucial role in cellular response mechanisms by recruiting the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) for activation [82]. Following this, ATR activates cell cycle checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1), leading to a reduction in Cdc25C levels [85]. This reduction is crucial for the subsequent activation of CDK1/cyclin B, illustrating a crucial cascade in cell cycle control and checkpoint activation (Figure 3). Furthermore, CDK9 is also phosphorylated at tyrosine 19 by anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) involving in poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) resistance and homologous recombination (HR) repair [86]. Also, CDK9 participates non-homologous end-joining with interaction of BRCA1 and BARD1 (BRCA1-associated RING domain 1) [81]. These findings suggest a potential role for CDK9 in the DNA Damage Response (DDR) and the ensuing arrest at the G2/M checkpoint.

Figure 3.

The involvement of the CDK9-55kDa isoform in DNA stress response.

The CDK9-55kDa variant forms a complex with cyclin K, which interacts with DNA damage-responsive proteins like ATR and Ku70 [82], leading to the activation of CHK1 that suppresses Cdc25C [85], thereby promoting DNA damage repair through Homologous Recombination (HR) or Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathways.

The role of CDK9 isoforms in transcription regulation and cellular responses

CDK9 plays distinct functionality in transcription regulation [87] and cell cycle checkpoint control [76]. This kinase’s involvement in diverse cellular responses, especially its capacity to regulate gene expression related to damage repair processes, is noteworthy. Yet, the mechanisms that enable CDK9 to concurrently oversee repair operations and the transcription of associated genes are still to be fully understood. The identification of CDK9’s functional variations points to an intricate regulatory system. A scientific challenge lies in deciphering how CDK9 shifts between initiating repair mechanisms and fine-tuning transcription for specific repair pathways. This complex equilibrium, where CDK9 balances between directing repair processes and modulating relevant transcription, is an area ripe for further investigation.

Investigations into CDK9’s diverse functions revealed distinct transcript isoforms. CDK9 transcripts share core exons but originate from different promoters, resulting in two isoforms of 42kDa and 55kDa [88]. The CDK9-55kDa variant, distinguished by its additional N-terminal sequence, does not interact with cyclin T1 and is localized to the nucleolus [89]. Although both forms exhibit kinase activity with RNA polymerase II [88], the extended N-terminal region of CDK9-55kDa still remains unknown in unique regulatory roles and interactions. The CDK9-55kDa isoform is associated with specific functions, such as muscle regeneration and differentiation [90] and macrophage differentiation [89]. The regulatory mechanisms and phosphorylation dynamics of various CDK9 isoforms, however, remain an area in need of deeper exploration.

The role of CDK9 dysregulation in cancer progression and therapeutic targeting

The dysregulation of CDK9 has emerged as a key factor in the regulation of cell death, particularly in the context of cancer [91,92]. Aberrant CDK9 activity is correlated with various aspects of cancer behavior such as enhanced cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis, disrupting the delicate balance between cell survival and programmed cell death [93–96]. Elevated CDK9 levels have been associated with increased transcriptional activity, the expression of anti-apoptotic genes, and enhanced cell proliferation. Conversely, inadequate CDK9 function may result in prolonged transcriptional pauses, affecting crucial pro-survival pathways. Hence, targeting CDK9 has emerged as a candidate cancer treatment strategy with the development of inhibitors (Table 1). Notably, the inhibition of CDK9 has been shown to decrease the phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II, indicating a potential molecular mechanism underlying the therapeutic impact of CDK9 inhibition in the context of cancer. Understanding the nuanced role of CDK9 dysregulation in cancer cell death holds promise for developing targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring the delicate balance necessary for effective cancer treatment.

Table 1.

Pan and selective CDK9 inhibitors.

| Name | Target | IC50 for CDK9 |

|---|---|---|

| SNS-032 [97,98] | CDK2, CDK5, CDK7 and CDK9 | 4 nM |

| Dinaciclib [99] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK5 and CDK9 | 4 nM |

| Flavopiridol [100] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK6, CDK7 and CDK9 | 20 nM |

| AT7519 [101] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK6 and CDK9 | <10 nM |

| AZD5438 [102] | CDK1, CDK2, and CDK9 | 20 nM |

| PHA-793887 [103] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK5, CDK7 and CDK9 | 138 nM |

| PHA-767491 hCl [104] | CDK9, CDK1, CDK2 | 34 nM |

| Riviciclib hydrochloride [105] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK6, CDK7 and CDK9 | 20 nM |

| RGB-286638 | CDK1, CDK2, CDK3, CDK4, CDK5 and CDK9 | 1 nM |

| CGP60474 [106] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK5, CDK7 and CDK9 | 13 nM |

| CDKI-73 [107] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK4 and CDK9 | 5.78 nM |

| Samuraciclib hydrochloride [108] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK5, CDK7 and CDK9 | 1.2 μM |

| Bohemine | CDK2 and CDK9 | 2.7 μM |

| AT7519 hCl [109] | CDK1, CDK2, CDK3, CDK4, CDK5, CDK6 and CDK9 | <10 nM |

| G1T38 | CDK4, CDK6 and CDK9 | 28 nM |

| Fadraciclib [110] | CDK2, CDK9 | 26 nM |

| LY2857785 [111] | CDK9, CDK8 and CDK7 | 0.011 μM |

| CDK-IN-2 | CDK9 | <8 nM |

| CAN508 | CDK9 | 0.35 μM |

| KB-0742 Dihydrochloride | CDK9 | 6 nM |

| NVP-2 [112] | CDK9 | 0.514 nM |

| JSH-150 | CDK9 | 1 nM |

| Enitociclib [113] | CDK9 | 3 nM |

| MC180295 [114] | CDK9 | 5 nM |

| AZD4573 [115] | CDK9 | <0.004 μM |

| Atuveciclib [116] | CDK9 | 13 nM |

| LDC000067 [117] | CDK9 | 44 nM |

Inhibiting CDK9 has been shown to attenuate cell proliferation in various cancer types, including osteosarcoma [95], endometrial cancer [118], ovarian cancer [119], pancreatic cancer [120], and prostate cancer [121]. The inhibition of CDK9 via Voruciclib prompts caspase 3 cleavage, instigating apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [92]. CDK9’s crucial role in maintaining MDM4 expression suppresses p53 activity in cancer cells [122]. Suppression of CDK9 leads to swift Mcl-1 turnover, triggering apoptosis in hematologic cancer cells [123]. The inhibitor Dinaciclib reduces Mcl-1 expression, resulting in apoptosis in B-cell lymphoma [124]. CDK9 inhibition decreases cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (cFlip) and Mcl-1, enhancing sensitivity to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) treatment in cancers [125]. Utilizing a CDK9 inhibitor to sensitize TRAIL-mediated cell death has been explored in colorectal cancer [126] and pancreatic cancer [127]. CDK9 inhibition induces apoptosis by downregulating c-Myc-mediated glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) and hexokinase 2 (HK2) in B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (B-ALL) [128]. The dysregulation of CDK9 suggests its significant impact on cell growth and indicates its potential role in cell cycle regulation.

A hypothetical model positions CDK9 as a regulatory hub in both transcription and cell cycle regulation

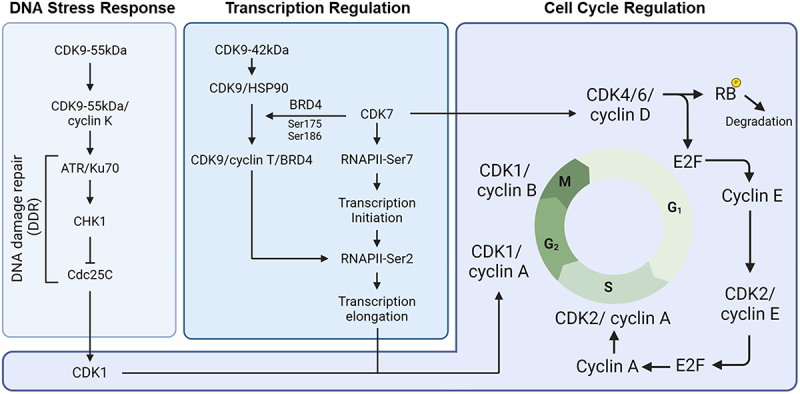

CDK7 is recognized for its crucial role in phosphorylating other CDKs, thereby playing a pivotal role in cell cycle progression, notably via CDK1/2, as extensively reported in the literature [60]. Beyond this, CDK7 may also have a significant role in transcriptional remodeling under stress conditions, potentially decelerating both transcription and cell cycle processes. The orchestration of CDK activity hinges on the interactions between CDKs acting as CAKs and those involved in other cell cycle-related functions. In this framework, CDK7 acts as an active CAK for cell cycle CDKs [129], in contrast to CDK8, which serves to inhibit CAK activity of these CDKs [130]. CDK9, however, utilizes a unique approach to regulate transcription and the cell cycle, marking a departure from the roles of CDK7 and CDK8. Additionally, the multiple CDK9 isoforms may participate in specialized roles, during recovery from DNA replication stress and potentially engaging in transcriptional regulation, a facet of CDK9 function that remains underexplored. This highlights CDK9 as a kinase with dual functionality, actively involved in adjusting transcription in response to stress, positioning it alongside CDK7 as a critical regulatory nexus.

CDK9’s role as a regulatory hub is crucial in modulating transcription and cell cycle regulation. Following phosphorylation by CDK7, CDK9 is released from the CDK9/HSP90 complex, enabling its interaction with cyclin T. This interaction leads to the formation of the P-TEFb complex, integral for transcription activation and RNAPII activation, thereby maintaining cell cycle-specific gene expression through various stages. In response to DNA stress, a different isoform, CDK9-55kDa, emerges due to transcript variations and associates with cyclin K, Ku70, BRCA, and ATR at DNA damage repair sites, underscoring its role in DNA repair [76,81,84]. Moreover, CDK2 has been identified to phosphorylate CDK9 at Serine-90 [131], with the dephosphorylation of Serine-175 regulated by protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) [132], implying a dual function of CDK9 in transcription regulation and cell cycle regulation.

The functional diversity of CDK9, through its isoforms, reveals unique and largely undefined roles, positioning it as a dual regulator of transcription and cell cycle checkpoints. Unlike CDK7, CDK9’s extended peptide in its isoforms plays a complex role that remains to be fully deciphered, suggesting CDK9’s potential function as a cellular sensor critical for balancing cell cycle progression with the activation of repair mechanisms (Figure 4). In response to stress, specific signaling pathways tailor CDK9’s activity, directing it toward DNA repair through distinct mechanisms compared to CDK7. This is facilitated by unique protein modifications on CDK9 isoforms, modifying their interactions with proteins involved in the damage response. Once damage is resolved, these modifications diminish, restoring the CDK9-42kDa isoform’s function and resuming regular transcription activities related to mitosis.

Figure 4.

Proposed Model: a role for CDK9 in coordinating transcription and Cell Cycle Regulation. We hypothesize that CDK9 shifts between isoforms to manage transcription regulation and DNA stress response effectively.

The coordination of extracellular stimuli sensors can trigger cell cycle arrest in response to damage. CDK9, a key kinase in the P-TEFb complex, may play a role in transcription activation, although its involvement in cell cycle regulation is still unclear. Stress-induced CDK9 isoforms could modulate gene expression by upregulating DNA damage response genes and downregulating cell cycle genes. However, there is no definitive evidence on how CDK9 directly influences transcription factor binding affinity or downstream gene expression changes. Given the limited preliminary observations, CDK9 may have an as-yet-undiscovered role in coordinating these cellular processes.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NIH/NCI U54CA143803, CA163124, CA093900, CA143055; CDMRP/PCRP W81XWH-20-10353, W81XWH-22-1-0680, the Patrick C. Walsh Prostate Cancer Research Fund, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation; Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan [110-2926-I-002-513].

Disclosure statement

Kenneth J. Pienta is a consultant for CUE Biopharma, Inc., is a founder and holds equity interest in Keystone Biopharma, Inc., and holds equity interest in Kreftect, Inc. Sarah R. Amend holds equity interest in Keystone Biopharma, Inc. All other authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- [1].Luna-Maldonado F, Andonegui-Elguera MA, Diaz-Chavez J, et al. Mitotic and DNA damage response proteins: maintaining the genome stability and working for the common good. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:700162. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.700162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB.. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421(6922):499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marechal A, Zou L. DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(9):a012716–a012716. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Patil M, Pabla N, Dong Z. Checkpoint kinase 1 in DNA damage response and cell cycle regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(21):4009–4021. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1307-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zannini L, Delia D, Buscemi G. CHK2 kinase in the DNA damage response and beyond. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014;6(6):442–457. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kaufmann WK, Paules RS. DNA damage and cell cycle checkpoints. FASEB J. 1996;10(2):238–247. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.2.8641557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dasika GK, Lin SC, Zhao S, et al. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoints and DNA strand break repair in development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18(55):7883–7899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cao L, Kim S, Xiao C, et al. ATM-Chk2-p53 activation prevents tumorigenesis at an expense of organ homeostasis upon Brca1 deficiency. Embo J. 2006;25(10):2167–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Heffernan TP, Simpson DA, Frank AR, et al. An ATR- and Chk1-dependent S checkpoint inhibits replicon initiation following uvc-induced DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(24):8552–8561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Busch C, Barton O, Morgenstern E, et al. The G2/M checkpoint phosphatase cdc25C is located within centrosomes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(9):1707–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu K, Zheng M, Lu R, et al. The role of CDC25C in cell cycle regulation and clinical cancer therapy: a systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20(1):213. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01304-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bakr A, Oing C, Kocher S, et al. Involvement of ATM in homologous recombination after end resection and RAD51 nucleofilament formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(6):3154–3166. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Britton S, Chanut P, Delteil C, et al. ATM antagonizes NHEJ proteins assembly and DNA-ends synapsis at single-ended DNA double strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(17):9710–9723. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tarsounas M, Sung P. The antitumorigenic roles of BRCA1-BARD1 in DNA repair and replication. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(5):284–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lord CJ, Ashworth A. RAD51, BRCA2 and DNA repair: a partial resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(6):461–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Feng L, Li N, Li Y, et al. Cell cycle-dependent inhibition of 53BP1 signaling by BRCA1. Cell Discov. 2015;1:15019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen WM, Chiang JC, Shang Z, et al. DNA-PKcs and ATM modulate mitochondrial ADP-ATP exchange as an oxidative stress checkpoint mechanism. Embo J. 2023;42(6):e112094. doi: 10.15252/embj.2022112094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yan S, Sorrell M, Berman Z. Functional interplay between atm/atr-mediated DNA damage response and DNA repair pathways in oxidative stress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(20):3951–3967. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1666-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bach DH, Long NP, Luu TT, et al. The dominant role of forkhead box proteins in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3279. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rathbone CR, Booth FW, Lees SJ. FoxO3a preferentially induces p27Kip1 expression while impairing muscle precursor cell-cycle progression. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37(1):84–89. doi: 10.1002/mus.20897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang Y, Xing Y, Zhang L, et al. Regulation of cell cycle progression by forkhead transcription factor FOXO3 through its binding partner DNA replication factor Cdt1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(15):5717–5722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203210109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bachs O, Gallastegui E, Orlando S, et al. Role of p27(Kip1) as a transcriptional regulator. Oncotarget. 2018;9(40):26259–26278. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen X, Muller GA, Quaas M, et al. The forkhead transcription factor FOXM1 controls cell cycle-dependent gene expression through an atypical chromatin binding mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(2):227–236. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00881-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Leung TW, Lin SS, Tsang AC, et al. Over-expression of FoxM1 stimulates cyclin B1 expression. FEBS Lett. 2001;507(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02915-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fu Z, Malureanu L, Huang J, et al. Plk1-dependent phosphorylation of FoxM1 regulates a transcriptional programme required for mitotic progression. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(9):1076–1082. doi: 10.1038/ncb1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Senturk E, Manfredi JJ. p53 and cell cycle effects after DNA damage. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;962:49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hyun SY, Jang YJ. p53 activates G(1) checkpoint following DNA damage by doxorubicin during transient mitotic arrest. Oncotarget. 2015;6(7):4804–4815. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim S, Armand J, Safonov A, et al. Sequential activation of E2F via Rb degradation and c-myc drives resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in breast cancer. Cell Rep. 2023;42(11):113198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yen A, Sturgill R. Hypophosphorylation of the RB protein in S and G2 as well as G1 during growth arrest. Exp Cell Res. 1998;241(2):324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Maity SN, de Crombrugghe B. Role of the ccaat-binding protein CBF/NF-Y in transcription. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23(5):174–178. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01201-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gurtner A, Manni I, Piaggio G. NF-Y in cancer: impact on cell transformation of a gene essential for proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2017;1860(5):604–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bertoli C, Skotheim JM, de Bruin RA. Control of cell cycle transcription during G1 and S phases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(8):518–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm3629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Meryet-Figuiere M, Alaei-Mahabadi B, Ali MM, et al. Temporal separation of replication and transcription during S-phase progression. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(20):3241–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tsirkas I, Dovrat D, Thangaraj M, et al. Transcription-replication coordination revealed in single live cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(4):2143–2156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Barnum KJ, O’Connell MJ. Cell cycle regulation by checkpoints. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1170:29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sun S, Zhou J. Molecular mechanisms underlying stress response and adaptation. Thorac Cancer. 2018;9(2):218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fulda S, Gorman AM, Hori O, et al. Cellular stress responses: cell survival and cell death. Int J Cell Biol 2010. 2010;2010:214074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pluta AJ, Studniarek C, Murphy S, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinases: masters of the eukaryotic universe. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2023;15:e1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fujinaga K, Huang F, Peterlin BM. P-TEFb: the master regulator of transcription elongation. Mol Cell. 2023;83(3):393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Malumbres M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):122. doi: 10.1186/gb4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lukasik P, Zaluski M, Gutowska I. Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) and their role in diseases development-review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Huang H, Regan KM, Lou Z, et al. CDK2-dependent phosphorylation of FOXO1 as an apoptotic response to DNA damage. Science. 2006;314(5797):294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kim S, Leong A, Kim M, et al. CDK4/6 initiates Rb inactivation and CDK2 activity coordinates cell-cycle commitment and G1/S transition. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):16810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Laoukili J, Alvarez M, Meijer LA, et al. Activation of FoxM1 during G2 requires cyclin A/Cdk-dependent relief of autorepression by the FoxM1 N-terminal domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(9):3076–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shen Q, Uray IP, Li Y, et al. The AP-1 transcription factor regulates breast cancer cell growth via cyclins and E2F factors. Oncogene. 2008;27(3):366–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gille H, Downward J. Multiple ras effector pathways contribute to G(1) cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(31):22033–22040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hinz M, Krappmann D, Eichten A, et al. Nf-κB function in growth control: regulation of Cyclin D1 expression and G 0 /G 1 -to-S-Phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(4):2690–2698. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.4.2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Daksis JI, Lu RY, Facchini LM, et al. Myc induces cyclin D1 expression in the absence of de novo protein synthesis and links mitogen-stimulated signal transduction to the cell cycle. Oncogene. 1994;9(12):3635–3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mustafa EH, Laven-Law G, Kikhtyak Z, et al. Selective inhibition of CDK9 in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2023;43:202–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lees E, Faha B, Dulic V, et al. Cyclin E/cdk2 and cyclin A/cdk2 kinases associate with p107 and E2F in a temporally distinct manner. Genes Dev. 1992;6(10):1874–1885. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mitra J, Enders GH. Cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes regulate activation of Cdk1 and Cdc25 phosphatases in human cells. Oncogene. 2004;23(19):3361–3367. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Vigneron S, Sundermann L, Labbe JC, et al. Cyclin A-cdk1-dependent phosphorylation of bora is the triggering factor promoting mitotic entry. Dev Cell. 2018;45(5):637–50 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fischer M, Schade AE, Branigan TB, et al. Coordinating gene expression during the cell cycle. Trends Biochem Sci. 2022;47(12):1009–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cornwell JA, Crncec A, Afifi MM, et al. Loss of CDK4/6 activity in S/G2 phase leads to cell cycle reversal. Nature. 2023;619(7969):363–370. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06274-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kalan S, Amat R, Schachter MM, et al. Activation of the p53 transcriptional program sensitizes cancer cells to Cdk7 inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2017;21(2):467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ma Y, Chen L, Wright GM, et al. CDKN1C negatively regulates RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphorylation in an E2F1-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(13):9813–9822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.091496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Mbonye U, Wang B, Gokulrangan G, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (CDK7)-mediated phosphorylation of the CDK9 activation loop promotes P-TEFb assembly with tat and proviral HIV reactivation. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(26):10009–10025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Schachter MM, Merrick KA, Larochelle S, et al. A Cdk7-Cdk4 T-loop phosphorylation cascade promotes G1 progression. Mol Cell. 2013;50(2):250–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Peissert S, Schlosser A, Kendel R, et al. Structural basis for CDK7 activation by MAT1 and Cyclin H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(43):26739–26748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Larochelle S, Merrick KA, Terret ME, et al. Requirements for Cdk7 in the assembly of Cdk1/cyclin B and activation of Cdk2 revealed by chemical genetics in human cells. Mol Cell. 2007;25(6):839–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Garrett S, Barton WA, Knights R, et al. Reciprocal activation by cyclin-dependent kinases 2 and 7 is directed by substrate specificity determinants outside the T loop. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(1):88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Duster R, Anand K, Binder SC, et al. Structural basis of Cdk7 activation by dual T-loop phosphorylation. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Fagundes R, Teixeira LK. Cyclin E/CDK2: DNA replication, replication stress and genomic instability. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:774845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kalous J, Jansova D, Susor A. Role of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 in translational regulation in the M-Phase. Cells. 2020;9(7):1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Serpico AF, Febbraro F, Pisauro C, et al. Compartmentalized control of Cdk1 drives mitotic spindle assembly. Cell Rep. 2022;38(4):110305. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Glover-Cutter K, Larochelle S, Erickson B, et al. Tfiih-associated Cdk7 kinase functions in phosphorylation of C-terminal domain Ser7 residues, promoter-proximal pausing, and termination by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(20):5455–5464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00637-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Egloff S. CDK9 keeps RNA polymerase II on track. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(14):5543–5567. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03878-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Fu TJ, Peng J, Lee G, et al. Cyclin K functions as a CDK9 regulatory subunit and participates in RNA polymerase II transcription. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(49):34527–34530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Peng J, Zhu Y, Milton JT, et al. Identification of multiple cyclin subunits of human P-TEFb. Genes Dev. 1998;12(5):755–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Gressel S, Schwalb B, Decker TM, et al. CDK9-dependent RNA polymerase II pausing controls transcription initiation. Elife. 2017;6:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Perez-Pepe M, Desotell AW, Li H, et al. 7SK methylation by METTL3 promotes transcriptional activity. Sci Adv. 2023;9(19):eade7500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Nguyen VT, Kiss T, Michels AA, et al. 7SK small nuclear RNA binds to and inhibits the activity of CDK9/cyclin T complexes. Nature. 2001;414(6861):322–325. doi: 10.1038/35104581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Napolitano G, Licciardo P, Carbone R, et al. CDK9 has the intrinsic property to shuttle between nucleus and cytoplasm, and enhanced expression of cyclin T1 promotes its nuclear localization. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192(2):209–215. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Baumli S, Lolli G, Lowe ED, et al. The structure of P-TEFb (CDK9/cyclin T1), its complex with flavopiridol and regulation by phosphorylation. Embo J. 2008;27(13):1907–1918. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Giacinti C, Bagella L, Puri PL, et al. MyoD recruits the cdk9/cyclin T2 complex on myogenic-genes regulatory regions. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206(3):807–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Yu DS, Zhao R, Hsu EL, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9-cyclin K functions in the replication stress response. EMBO Rep. 2010;11(11):876–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Chen S, Gulla S, Cai C, et al. Androgen receptor serine 81 phosphorylation mediates chromatin binding and transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(11):8571–8583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Russo JW, Liu X, Ye H, et al. Phosphorylation of androgen receptor serine 81 is associated with its reactivation in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;438:97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].McAllister MJ, McCall P, Dickson A, et al. Androgen receptor phosphorylation at serine 81 and serine 213 in castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23(4):596–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Gao X, Liang J, Wang L, et al. Phosphorylation of the androgen receptor at Ser81 is co-sustained by CDK1 and CDK9 and leads to ar-mediated transactivation in prostate cancer. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(7):1901–1920. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Nepomuceno TC, Fernandes VC, Gomes TT, et al. BRCA1 recruitment to damaged DNA sites is dependent on CDK9. Cell Cycle. 2017;16(7):665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Yu DS, Cortez D. A role for CDK9-cyclin K in maintaining genome integrity. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(1):28–32. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.1.14364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Zhang H, Park SH, Pantazides BG, et al. SIRT2 directs the replication stress response through CDK9 deacetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(33):13546–13551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Liu H, Herrmann CH, Chiang K, et al. 55K isoform of CDK9 associates with Ku70 and is involved in DNA repair. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397(2):245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Gralewska P, Gajek A, Marczak A, et al. Participation of the ATR/CHK1 pathway in replicative stress targeted therapy of high-grade ovarian cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Chu YY, Chen MK, Wei Y, et al. Targeting the alk–CDK9-Tyr19 kinase cascade sensitizes ovarian and breast tumors to PARP inhibition via destabilization of the P-TEFb complex. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(10):1211–1227. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00438-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Bacon CW, D’Orso I. CDK9: a signaling hub for transcriptional control. Transcription. 2019;10(2):57–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Shore SM, Byers SA, Maury W, et al. Identification of a novel isoform of Cdk9. Gene. 2003;307:175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Liu H, Herrmann CH. Differential localization and expression of the Cdk9 42k and 55k isoforms. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203(1):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Giacinti C, Musaro A, De Falco G, et al. Cdk9–55: a new player in muscle regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216(3):576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Kato N, Kozako T, Ohsugi T, et al. CDK9 inhibitor induces apoptosis, autophagy, and suppression of tumor growth in adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma. Biol Pharm Bull. 2023;46(9):1269–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Luedtke DA, Su Y, Ma J, et al. Inhibition of CDK9 by voruciclib synergistically enhances cell death induced by the bcl-2 selective inhibitor venetoclax in preclinical models of acute myeloid leukemia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Romano G. Deregulations in the cyclin-dependent kinase-9-related pathway in cancer: implications for drug discovery and development. ISRN Oncol. 2013;2013:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2013/305371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Hu C, Shen L, Zou F, et al. Predicting and overcoming resistance to CDK9 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(9):3694–3707. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ma H, Seebacher NA, Hornicek FJ, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) is a novel prognostic marker and therapeutic target in osteosarcoma. EBioMedicine. 2019;39:182–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Mustafa EH, Laven-Law G, Kikhtyak Z, et al. Selective inhibition of CDK9 in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2024;43(3):202–215. doi: 10.1038/s41388-023-02892-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Jiang L, Wen C, Zhou H, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 7/9 inhibitor SNS-032 induces apoptosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2022;23(1):319–327. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2022.2055421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Bottomly D, Long N, Schultz AR, et al. Integrative analysis of drug response and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(8):850–64 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Saqub H, Proetsch-Gugerbauer H, Bezrookove V, et al. Dinaciclib, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, suppresses cholangiocarcinoma growth by targeting CDK2/5/9. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Zhai S, Senderowicz AM, Sausville EA, et al. Flavopiridol, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in clinical development. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(5):905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Zhao W, Zhang L, Zhang Y, et al. The CDK inhibitor AT7519 inhibits human glioblastoma cell growth by inducing apoptosis, pyroptosis and cell cycle arrest. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(1):11. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05528-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Wang Y, Luo R, Zhang X, et al. Proteogenomics of diffuse gliomas reveal molecular subtypes associated with specific therapeutic targets and immune-evasion mechanisms. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Sidorkiewicz I, Jozwik M, Buczynska A, et al. Identification and subsequent validation of transcriptomic signature associated with metabolic status in endometrial cancer. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):13763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Chen S, Pan C, Huang J, et al. ATR limits Rad18-mediated PCNA monoubiquitination to preserve replication fork and telomerase-independent telomere stability. Embo J. 2024;43(7):1301–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Cossa G, Roeschert I, Prinz F, et al. Localized inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 by NUAK1 promotes spliceosome activity and reveals a MYC-Sensitive feedback control of transcription. Mol Cell. 2020;77(6):1322–39 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Rajadurai A, Tsao H. Identification of collagen-suppressive agents in keloidal fibroblasts using a high-content, phenotype-based drug screen. JID Innov. 2024;4(2):100248. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2023.100248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Brewer K, Bai F, Blencowe A. pH-responsive Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(2-vinylpyridine) micelles for the triggered release of therapeutics. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(3):977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Fang J, Singh S, Cheng C, et al. Genome-wide mapping of cancer dependency genes and genetic modifiers of chemotherapy in high-risk hepatoblastoma. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Wang H, Wang X, Wang W, et al. Interleukin-15 enhanced the survival of human γδT cells by regulating the expression of mcl-1 in neuroblastoma. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):139. doi: 10.1038/s41420-022-00942-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Chen R, Chen Y, Xiong P, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor fadraciclib (CYC065) depletes anti-apoptotic protein and synergizes with venetoclax in primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2022;36(6):1596–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Lavy M, Gauttier V, Dumont A, et al. ChemR23 activation reprograms macrophages toward a less inflammatory phenotype and dampens carcinoma progression. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1196731. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1196731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Valdez Capuccino L, Kleitke T, Szokol B, et al. CDK9 inhibition as an effective therapy for small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(5):345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Cai Y, Chen M, Gong Y, et al. Androgen-repressed lncRNA LINC01126 drives castration-resistant prostate cancer by regulating the switch between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of androgen receptor. Clin & Transl Med. 2024;14(1):e1531. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Fujii T, Nishikawa J, Fukuda S, et al. MC180295 inhibited Epstein–Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma cell growth by suppressing DNA repair and the cell cycle. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10597. doi: 10.3390/ijms231810597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Zhao J, Cato LD, Arora UP, et al. Inherited blood cancer predisposition through altered transcription elongation. Cell. 2024;187(3):642–58 e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Zhao F, Wang Y, Zuo H, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) inhibitor atuveciclib ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis in mice by inhibiting various inflammation factors via STAT3 signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;129:111652. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Patel PS, Algouneh A, Krishnan R, et al. Excessive transcription-replication conflicts are a vulnerability of BRCA1-mutant cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(9):4341–4362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].He S, Fang X, Xia X, et al. Targeting CDK9: a novel biomarker in the treatment of endometrial cancer. Oncol Rep. 2020;44(5):1929–1938. doi: 10.3892/or.2020.7746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Wang J, Dean DC, Hornicek FJ, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) is a novel prognostic marker and therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. FASEB J. 2019;33(5):5990–6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Kretz AL, Schaum M, Richter J, et al. CDK9 is a prognostic marker and therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017;39(2):1010428317694304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Li J, Liu T, Song Y, et al. Discovery of small-molecule degraders of the CDK9-cyclin T1 complex for targeting transcriptional addiction in prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2022;65(16):11034–11057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Stetkova M, Growkova K, Fojtik P, et al. CDK9 activity is critical for maintaining MDM4 overexpression in tumor cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(9):754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Cidado J, Boiko S, Proia T, et al. AZD4573 is a highly selective CDK9 inhibitor that suppresses MCL-1 and induces apoptosis in hematologic cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(4):922–934. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Gregory GP, Hogg SJ, Kats LM, et al. CDK9 inhibition by dinaciclib potently suppresses mcl-1 to induce durable apoptotic responses in aggressive myc-driven B-cell lymphoma in vivo. Leukemia. 2015;29(6):1437–1441. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Lemke J, von Karstedt S, Abd El Hay M, et al. Selective CDK9 inhibition overcomes TRAIL resistance by concomitant suppression of cFlip and mcl-1. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(3):491–502. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Shen X, Kretz AL, Schneider S, et al. Evaluation of CDK9 inhibition by Dinaciclib in combination with apoptosis modulating izTRAIL for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Biomedicines. 2023;11(3):928. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11030928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Ruff JP, Kretz AL, Kornmann M, et al. The novel, orally bioavailable CDK9 inhibitor atuveciclib sensitises pancreatic cancer cells to trail-induced cell death. Anticancer Res. 2021;41(12):5973–5985. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Huang WL, Abudureheman T, Xia J, et al. CDK9 inhibitor induces the apoptosis of B-Cell acute lymphocytic leukemia by inhibiting c-myc-mediated glycolytic metabolism. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:641271. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.641271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Bisteau X, Paternot S, Colleoni B, et al. CDK4 T172 phosphorylation is central in a CDK7-dependent bidirectional CDK4/CDK2 interplay mediated by p21 phosphorylation at the restriction point. PloS Genet. 2013;9(5):e1003546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Abdelmalak M, Singh R, Anwer M, et al. The renaissance of CDK inhibitors in breast cancer therapy: an update on clinical trials and therapy resistance. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(21):5388. doi: 10.3390/cancers14215388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Breuer D, Kotelkin A, Ammosova T, et al. CDK2 regulates HIV-1 transcription by phosphorylation of CDK9 on serine 90. Retrovirology. 2012;9:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Nekhai S, Petukhov M, Breuer D. Regulation of CDK9 activity by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Biomed Res Int 2014. 2014:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/964964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]