Abstract

Cancer driver genes play a pivotal role in understanding cancer development, progression, and therapeutic discovery. The plenty of accumulation of multi-omics data and biological networks provides a data foundation for graph neural network (GNN) frameworks. However, most existing methods directly concatenate multi-omics data as features, which may lead to limited performance. To address this limitation, we propose deepCDG, a deep graph convolutional network (GCN)-based multi-omics integration model for cancer driver gene identification. The model first employs shared-parameter GCN encoders to extract representations from three omics perspectives, followed by feature integration through an attention layer, and finally utilizes a residual-connected GCN predictor for cancer driver gene identification. Additionally, deepCDG employs GNNExplainer for cancer driver gene module identification. Experimental results demonstrate the effective predictive performance, model robustness, and computational efficiency of deepCDG. Additionally, biological interpretability analysis further validates the reliability of the identification of cancer driver genes of our framework, and the identified gene modules provide profound insights into complex inter-gene relationships and interactions. We believe our method offers enhanced applicability for cancer driver gene identification and could be extended to other biological research fields in future studies.

Keywords: cancer driver genes, multi-omics data, graph convolutional networks, gene modules

Introduction

Cancer is a complex multifactorial disease, and mutations in specific genes can confer a selective proliferative advantage to cells, thereby driving cancer initiation and progression. Genes responsible for oncogenesis and disease advancement are referred to as cancer driver genes. Therefore, identifying cancer driver genes plays a crucial role in understanding carcinogenic mechanisms, developing targeted therapies, and advancing precision medicine [1–4].

Early approaches, such as MutSigCV [5], Oncodrive-CLUST [6], and dNdScv [7], are primarily based on mutation frequency under the assumption that cancer driver genes should exhibit significantly higher mutation rates compared to background genes. However, these methods demonstrate limited sensitivity for rare cancer driver genes (less than 1% mutation rate), resulting in missed detection of low-frequency cancer driver genes.

With the accumulation of biological network data, novel methodologies based on multiple biological networks have emerged for cancer driver gene identification [8–13]. HotNet2 [8] identifies interconnected subnetworks with significant mutation enrichment using heat diffusion models on leveraging protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks. BiRW [9] predicts cancer driver genes by performing a random walk on the Kronecker product graph between the PPI network and the phenotype similarity network to filter the noise and preserve semantic information. However, only structural information limits the performance on predicting cancer driver genes.

Recently, as graph neural networks (GNNs) can unearth hidden driver signals and capture detailed neighborhood environments, GNN-based deep learning with multi-omics integration models have been proposed for predicting cancer driver genes[14–20]. For instance, EMOGI [14] combines multi-omics data with PPI networks using graph convolutional networks (GCNs) [21]. It aggregates node representations from topological neighbors to capture network context and identify cancer genes. MTGCN [15] combines biological and structural features to develop enhanced representations and designs an additional edge reconstruction task to improve the performance. SMG [16] employs self-supervised masked graph autoencoders to reconstruct masked multi-omic PPI networks, followed by task-specific fine-tuning where pre-trained GNN-derived feature embeddings inform final predictive layers. Additionally, some methods enhance the predictive accuracy by considering the heterophilic graphs. HGDC [17] aggregates node representations by constructing auxiliary graph diffusions considering the heterophilic nature of biological networks. SGCD [18] combines the GCN with representation separation and bimodal feature extractor to generate node embeddings and preserve the semantic information from PPI and multi-omics. Moreover, some methods use multi-networks to identify cancer driver genes. MNGCL [19] constructs PPI network, gene functional similarity network and pathway co-occurrence association network followed by graph contrastive learning encoders and GCNs to drive unique gene representations. MMGN [20] combines multi-omics and multiplex networks to extract representations, followed by the anomaly detection algorithm DeepSVDD to predict cancer driver genes. Although these methods make a progress, directly combining multi-omics data as node features may cause their omics crosstalk, thereby limiting the performance.

With the demonstrated success of multi-view representation learning in achieving enhanced cross-modal representation and performance [22–27], emerging approaches apply multi-view learning to the integration of multi-omics data [28, 29]. MVGNN [28] learns representations from different omics data based on a multi-view GNN and an attention module for integrating multi-omics data. IMVAL-GCN [29] designs a shared representation learner and a specific representation learner to extract shared and specific representations from multi-view data, demonstrating consensus and complementary effects. However, their performance results should be further improved.

In this work, we propose a deep graph convolutional network (GCN)-based multi-omics integration model for cancer driver gene identification, named deepCDG. The framework initially employs two shared-parameter GCN encoders to embed features across three omics views, and integrates representations through an attention layer. A residual-connected GCN predictor is then applied to the cancer driver gene identification. GNNExplainer is also introduced to extract cancer gene modules. Experimental results demonstrate the effective predictive performance across all datasets, with our model maintaining outstanding in robustness and computational efficiency. Subsequent biological interpretability validation confirms model reliability of predicting cancer driver genes, while identified gene modules provided mechanistic insights into complex intergenic relationships and interactions among genes.

Materials

Multi-omics data, including gene mutations, DNA methylation, and gene expression, are retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), encompassing 16 cancer subtypes, including Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma (BLCA), Breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), Cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), Colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), Esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), Lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), Rectum adenocarcinoma, Thyroid carcinoma (THCA), and Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma (UCEC) with a total of 29 446 biospecimens. For each gene, gene mutation rate, differential DNA methylation rate, and differential gene expression rate are respectively computed across the 16 cancer types, thus generating a 48-dimension feature vector. Subsequently, min-max normalization is conducted on the 48-dimension feature vector of each gene to transform all values to a range between 0 and 1. The details are shown in Section 3 in the Supplementary Materials.

The known cancer driver genes are derived from the following resources: the Network of Cancer Genes (NCG v6.0) [30], COSMIC Cancer Gene Census (v91) [31], and DigSEE [32]. The non-cancer driver genes are collected by excluding genes annotated in NCG, COSMIC, OMIM [33], and KEGG pathways [34].

PPI networks data are collected from CPDB [35], MULTI-NET [36], PCNet [37], STRINGdb [38], and IRefIndex [39]. We filter the interactions with confidence scores less than 0.5 on CPDB and less than 0.85 on STRINGdb. MULTINET and the 2015 IRefIndex version are sourced directly from the Hotnet2 GitHub repository. For the updated IRefIndex, only binary human protein interactions are considered. PCNet construction is consistent with the EMOGI framework [14]. To maintain the consistency across PPI datasets, each gene is standardized to its official symbols, with nodes representing genes and edges denoting experimentally validated interactions. Finally, we obtain the six uniformly formatted PPI networks and the information of PPI networks is shown in Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials.

Method

Overview of deepCDG

As shown in Fig. 1, deepCDG is a deep GCN-based multi-omics integration framework for efficient cancer driver gene identification. The deepCDG employs two weight-shared GCN encoders to learn unique gene representations. Then deepCDG incorporates MLP-based feature aggregation extractor to merge the two embeddings on gene expression omic. Subsequently, an attention layer integrates representations from three omics to generate cross-omics aggregated gene representations. Finally, a residual GCN classifier is applied to the cancer driver gene prediction. Additionally, we utilize GNNExplainer to identify core gene subgraphs for cancer gene module interpretation.

Figure 1.

Overview of deepCDG. (a) deepCDG employs weight-shared GCN encoders to learn gene representations, followed by a MLP-based feature aggregation extractor to fuse the two embeddings from the gene expression omic. Subsequently, an attention layer is used to generate cross-omic integrated gene representations. Finally, a residual GCN classifier is applied to the cancer driver gene prediction. (b) GNNExplainer is introduced to identify cancer gene modules.

Weight-shared GCN encoder for individual omic

We construct three graphs  ,

,  and

and  for a PPI network on the gene mutations, gene expression and DNA methylation respectively, where

for a PPI network on the gene mutations, gene expression and DNA methylation respectively, where  denotes the adjacency matrix,

denotes the adjacency matrix,  denotes the edges in the PPI network. For the omic feature matrix

denotes the edges in the PPI network. For the omic feature matrix  ,

,  means gene mutation, gene expression or DNA methylation omic,

means gene mutation, gene expression or DNA methylation omic,  denotes the number of genes and

denotes the number of genes and  denotes the dimensions of individual omic data. Meanwhile, to improve the generalization of deepCDG, we randomly remove the edges in the PPI network and mask the values of each feature matrix using certain probabilities to generate the enhanced graphs

denotes the dimensions of individual omic data. Meanwhile, to improve the generalization of deepCDG, we randomly remove the edges in the PPI network and mask the values of each feature matrix using certain probabilities to generate the enhanced graphs  ,

,  and

and  . Then we choose weight-shared GCNs as the encoders to learn the representations of genes. Through the first encoder, we derive the gene representations

. Then we choose weight-shared GCNs as the encoders to learn the representations of genes. Through the first encoder, we derive the gene representations  and

and  from

from  and

and  . Through the second encoder, we derive the gene representations

. Through the second encoder, we derive the gene representations  and

and  from

from  and

and  . In particular, the propagation rule for each layer in a GCN can be defined as:

. In particular, the propagation rule for each layer in a GCN can be defined as:

|

(1) |

where  denotes the feature representation of layer

denotes the feature representation of layer  ,

,  denotes the adjacency matrix with added self connections,

denotes the adjacency matrix with added self connections,  denotes the degree matrix,

denotes the degree matrix,  denotes a learnable weight matrix and

denotes a learnable weight matrix and  denotes a non-linear function, such as Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU).

denotes a non-linear function, such as Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU).

Subsequently, we utilize a multilayer perceptron (MLP) module followed by a linear layer to integrate the embeddings  and

and  from the gene expression to generate representations

from the gene expression to generate representations  . It can be formulated as follows:

. It can be formulated as follows:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

where  denotes a concatenation operation.

denotes a concatenation operation.

Cross-omic attention aggregation layer

Different omics can provide specific perspectives on the development and progression of cancers. Therefore, an integrated analysis is required to generate comprehensive representations of genes. The attention aggregation layer aims to integrate omic-specific representations which include  for gene mutation omic,

for gene mutation omic,  for gene expression omic and

for gene expression omic and  for DNA methylation omic in an adapted approach by capturing the different importance of each omic. The attention layer will concentrate on the more important omic through assigning greater weights to the corresponding omic. Specially, for a given omic representation, we first project it to the linear space by utilizing a fully-connected network. Then we obtain the importance of each omic representation by calculating the similarity between the omic representation and a trainable vector

for DNA methylation omic in an adapted approach by capturing the different importance of each omic. The attention layer will concentrate on the more important omic through assigning greater weights to the corresponding omic. Specially, for a given omic representation, we first project it to the linear space by utilizing a fully-connected network. Then we obtain the importance of each omic representation by calculating the similarity between the omic representation and a trainable vector  . Formally, for a gene

. Formally, for a gene  and its gene representation

and its gene representation  on the omic

on the omic  , the attention coefficient

, the attention coefficient  , representing the importance of omic

, representing the importance of omic  to the gene

to the gene  , can be defined as:

, can be defined as:

|

(5) |

where  denotes a trainable vector while

denotes a trainable vector while  and

and  are the trainable weight matrix and bias vector, respectively. To make the attention coefficient comparable across different omics, we utilize a softmax function to derive attention score

are the trainable weight matrix and bias vector, respectively. To make the attention coefficient comparable across different omics, we utilize a softmax function to derive attention score  , which can be defined as:

, which can be defined as:

|

(6) |

where  denotes the number of omics. Subsequently, the final output

denotes the number of omics. Subsequently, the final output  of the attention layer can be defined as:

of the attention layer can be defined as:

|

(7) |

where  denotes the integrated representation of gene

denotes the integrated representation of gene  .

.

Cancer driver gene predictor

Giving the cross-omic integrated representation  , we employ a GCN-based predictor to obtain the probabilities of genes functioning as cancer driver genes. Additionally, to reduce over-smoothing and make full use of cross-omic representations

, we employ a GCN-based predictor to obtain the probabilities of genes functioning as cancer driver genes. Additionally, to reduce over-smoothing and make full use of cross-omic representations  , we utilize residual connection in GCNs. Formally, the propagation rule for each layer in a residual GCN can be defined as:

, we utilize residual connection in GCNs. Formally, the propagation rule for each layer in a residual GCN can be defined as:

|

(8) |

where  and

and  are trainable weights and bias in the full connection layer.

are trainable weights and bias in the full connection layer.

We adopt the binary cross-entropy loss to train the model:

|

(9) |

where  is the label information of gene

is the label information of gene  (1 or 0) and

(1 or 0) and  is the prediction score of gene

is the prediction score of gene  .

.

Gene module interpretation

GNNExplainer [40] can identify critical subgraphs influencing GNN predictions by maximizing mutual information between predictions and simplified substructures. Therefore, we utilize GNNExplainer to derive the core subgraphs of predicted cancer driver genes. Formally, the core subgraph  for the gene

for the gene  can be defined as:

can be defined as:

|

(10) |

where  denotes learnable edge mask, representing edge importance for gene

denotes learnable edge mask, representing edge importance for gene  .

.  stands for hadamard product. The optimization goal can be defined as:

stands for hadamard product. The optimization goal can be defined as:

|

(11) |

where  denotes conditional entropy,

denotes conditional entropy,  denotes the node prediction and

denotes the node prediction and  denotes feature mask identifying key feature dimensions.

denotes feature mask identifying key feature dimensions.

Implementation details of deepCDG

Our model is built using Python 3.8, PyTorch Geometric 2.0.2 and PyTorch 1.8.0. In our experiments, the hidden layer dimensions of GCN encoders is set to 48. For GCN predictor, the filters for each layer are 100, 200, and 1. For GNNExplainer, the training epoch is set to 200. Other hyperparameters are consistent with the default values. We choose Adam as the optimizer for the model. The learning rate is set to 0.001. The dropout rates of masking features and cutting edges are both 0.5. The model is trained for 1200 epochs and the weight decay is set to 0. Algorithm 1 lists the pseudocode for running our model.

|

Results

Performance evaluation on pan-cancer datasets

To evaluate the performance of deepCDG, we compare it with five baseline models (MTGCN, HGDC, EMOGI, IMVRL-GCN, and SMG) across six PPI networks using five-fold cross-validation with ten repetitions to obtain the final results. To ensure fairness, all models employ identical PPI networks and multi-omics features. The PPI networks include CPDB, MULTINET, PCNet, STRINGdb, IRefIndex, and IRefIndex_2015. For the five-fold cross-validation, the datasets are randomly partitioned into a training set (75%) and a test set (25%), with the ratio of cancer driver genes to non-cancer driver genes maintained consistent with the original dataset in both training set and test set. The hyperparameters of all baseline models are kept consistent with those described in their original papers.

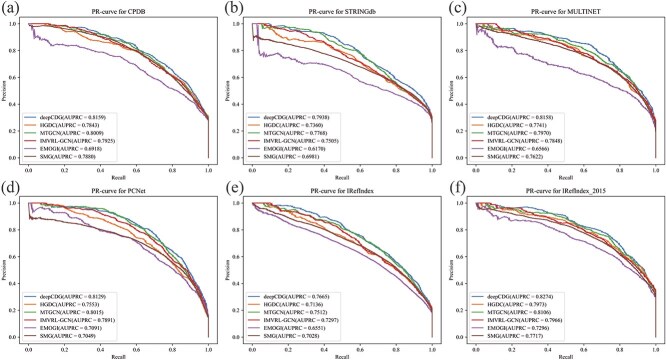

Figure 2 and Table 1 demonstrate the Precision–Recall (PR) curves and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) values respectively across all networks. The results show that deepCDG exhibits superior AUPRC compared to other models on pan-cancer datasets in all PPI networks, indicating its outstanding performance in predicting cancer driver genes.

Figure 2.

PR curve comparison of deepCDG and other baseline models on different PPI networks. (a) PR-curve for CPDB. (b) PR-curve for STRINGdb. (c) PR-curve for MULTINET. (d) PR-curve for PCNet. (e) PR-curve for IRefIndex. (f) PR-curve for IRefIndex_2015.

Table 1.

AUPRC values for deepCDG and other baseline models across different PPI networks

| PPI network | CPDB | STRINGdb | MULTINET | PCNet | IRefindex | IRefindex_2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGDC | 0.7843 | 0.7360 | 0.7741 | 0.7553 | 0.7136 | 0.7973 |

| IMVRL-GCN | 0.7925 | 0.7505 | 0.7848 | 0.7891 | 0.7297 | 0.7966 |

| MTGCN | 0.8009 | 0.7768 | 0.7970 | 0.8015 | 0.7512 | 0.8106 |

| SMG | 0.7880 | 0.6981 | 0.7622 | 0.7049 | 0.7028 | 0.7717 |

| EMOGI | 0.6918 | 0.6170 | 0.6566 | 0.7091 | 0.6551 | 0.7294 |

| deepCDG | 0.8159 | 0.7938 | 0.8158 | 0.8129 | 0.7665 | 0.8274 |

The best results are highlighted in bold.

To evaluate model robustness, we analyze the predictive performance of all models under three distinct perturbation scenarios: feature perturbation (random masking gene features), network removed perturbation (random edge removal in PPI networks) and network rewired perturbation (randomly rewiring PPI network with preserved node degrees similar to [41]), with perturbation frequencies set at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 0.9. As shown in Fig. 3, the feature and network perturbation experiments indicate the robust predictive capability of deepCDG under complex real-world interference conditions.

Figure 3.

Feature robustness, network removed and rewired robustness analysis of deepCDG and other baseline methods. (a) Feature robustness analysis. (b) Network removed robustness analysis.(c) Network rewired robustness analysis.

To assess computational efficiency, we measure the computational time required for all models to complete one five-fold cross-validation run across different PPI networks. As illustrated in Fig. 4, deepCDG demonstrates comparable execution time to EMOGI while consistently outperforms other baseline methods in time efficiency, highlighting its effective computational practicality on large-scale biological networks.

Figure 4.

Time overhead analysis of deepCDG and other baseline methods.

Ablation study

deepCDG is designed based on separately learning three omics representations followed by information fusion through an attention layer. To validate the contributions of different omics data, we first compare the performance of deepCDG with different combinations of omics as input data. “MF + MF” means that we use only gene mutations as the feature input. Similarly, “METH + METH” means using only DNA methylation as input, while “GE + GE” means using only gene expression as the omic feature input. We apply different dropout rates (0.4, 0.5, and 0.6) to the input omics features to enhance the data quality. When using two omics, we put the gene expression omic as input  and put another omic as

and put another omic as  and

and  when gene expression is included in the two omics. We put the gene mutation omic as input

when gene expression is included in the two omics. We put the gene mutation omic as input  and put another omic as

and put another omic as  and

and  when using gene mutation and DNA methylation omics. As shown in Table 2, the model performance declines when using only a single omics feature, while results improve with two omics, and achieve optimal performance when all three omics are combined. The result indicates the effectiveness of integration of all the three omics data.

when using gene mutation and DNA methylation omics. As shown in Table 2, the model performance declines when using only a single omics feature, while results improve with two omics, and achieve optimal performance when all three omics are combined. The result indicates the effectiveness of integration of all the three omics data.

Table 2.

Ablation study

| Methods | AUC | AUPRC |

|---|---|---|

| MF+MF | 0.8819 | 0.7925 |

| METH+METH | 0.8570 | 0.7348 |

| GE+GE | 0.8683 | 0.7490 |

| MF+METH | 0.8876 | 0.7985 |

| GE+MF | 0.8953 | 0.8089 |

| GE+METH | 0.8777 | 0.7636 |

| GE+MF+METH | 0.8995 | 0.8161 |

| Encoding by MLP | 0.8944 | 0.8031 |

| Without attention layer | 0.8960 | 0.8135 |

| No sharing weight in GCN encoder | 0.8930 | 0.8124 |

| Without MLP | 0.8969 | 0.8108 |

| Without residual | 0.8571 | 0.7187 |

| Predicting by MLP | 0.8869 | 0.7954 |

The best results are highlighted in bold.

Moreover, to analyze the contributions of different components in deepCDG, we subsequently perform model ablation experiments. “Encoding by MLP” means that we use MLP as encoders. “Without attention layer” means that the integrated representation is obtained by concatenating the three omics output. “No sharing weight in GCN encoder” means that we use independent encoders. “Without MLP” means that we delete the feature aggregation extractor. “Without residual” means that we delete the residual connection in GCNs. “Predicting by MLP” means we predict the cancer driver genes using MLP. We observe that GCN plays a critical role in extracting PPI and omics representations, but may underperform MLP without residual connections. Shared parameter configurations enhances the feature extraction across multi-omics features while integrating gene expression data through MLP-based integration and attention mechanisms further augment predictive accuracy. Overall, each omic contributes significantly to cancer driver gene identification, and the model ablation experiments validate the effectiveness of deepCDG.

Performance on cancer type-specific driver gene prediction

We further verify the performance of deepCDG on the 15 cancer types on CPDB dataset, including BRCA, LUAD, BLCA, LIHC, CESC, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, KIRC, KIRP, LUSC, PRAD, STAD, THCA, and UCEC. Cancer driver(positive) genes are collected based on NCG6.0 annotations, while non-cancer driver(negative) genes comprise 2187 genes consistent with pan-cancer datasets. For each cancer type, only the corresponding 3-dimension omics features, including gene mutation rate, differential DNA methylation rate and differential gene expression rate, are retained for each gene. As shown in Table 3, deepCDG achieves the highest AUPRC values for 11 out of 15 cancer types, with a 12.33% improvement over the second-best result for UCEC. Notably, it outperforms the second-best models by over 5% in AUPRC for 6 cancer types. Furthermore, deepCDG demonstrates superior AUC values for 9 cancer types. These results robustly demonstrate that deepCDG maintains effective performance even under extreme class imbalance between positive and negative genes in cancer-specific prediction tasks.

Table 3.

Performance on cancer type-specific driver gene prediction

| Cancer type | LUAD | BRCA | BLCA | LIHC | CESC | COAD | ESCA | HNSC | KIRC | KIRP | LUSC | PRAD | STAD | THCA | UCEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model/AUPRC | |||||||||||||||

| HGDC | 0.3427 | 0.3501 | 0.5737 | 0.2831 | 0.2184 | 0.4236 | 0.3040 | 0.3008 | 0.3405 | 0.4076 | 0.2401 | 0.3427 | 0.4569 | 0.1089 | 0.4147 |

| IMVRL-GCN | 0.2711 | 0.2390 | 0.5590 | 0.1502 | 0.2883 | 0.2589 | 0.1044 | 0.1248 | 0.1719 | 0.2500 | 0.1801 | 0.3606 | 0.4560 | 0.0708 | 0.3716 |

| MTGCN | 0.3104 | 0.4703 | 0.4643 | 0.2737 | 0.2291 | 0.4523 | 0.2973 | 0.3963 | 0.2913 | 0.2085 | 0.2519 | 0.4295 | 0.4754 | 0.1841 | 0.4321 |

| SMG | 0.2510 | 0.2935 | 0.3636 | 0.1506 | 0.0610 | 0.2163 | 0.1954 | 0.3619 | 0.2678 | 0.0399 | 0.0649 | 0.2552 | 0.3461 | 0.1419 | 0.1184 |

| EMOGI | 0.1723 | 0.2292 | 0.1160 | 0.1138 | 0.0496 | 0.0840 | 0.0793 | 0.0744 | 0.0716 | 0.0464 | 0.0312 | 0.1198 | 0.0754 | 0.1112 | 0.1292 |

| deepCDG | 0.3830 | 0.4755 | 0.5849 | 0.3421 | 0.2001 | 0.5102 | 0.3119 | 0.3803 | 0.3449 | 0.3200 | 0.2695 | 0.4890 | 0.5244 | 0.1011 | 0.5554 |

| Model/AUC | |||||||||||||||

| HGDC | 0.8991 | 0.8901 | 0.9454 | 0.8642 | 0.8040 | 0.9055 | 0.8896 | 0.8964 | 0.8707 | 0.9121 | 0.8986 | 0.8950 | 0.9538 | 0.8489 | 0.9146 |

| IMVRL-GCN | 0.8762 | 0.8466 | 0.9389 | 0.8350 | 0.9041 | 0.8117 | 0.7899 | 0.8418 | 0.7840 | 0.8816 | 0.8890 | 0.8919 | 0.9243 | 0.7949 | 0.8936 |

| MTGCN | 0.8895 | 0.9253 | 0.9122 | 0.8636 | 0.8468 | 0.8847 | 0.8535 | 0.9219 | 0.8407 | 0.9101 | 0.8873 | 0.8667 | 0.9373 | 0.8815 | 0.9218 |

| SMG | 0.8618 | 0.8918 | 0.9093 | 0.8741 | 0.9151 | 0.8269 | 0.8526 | 0.8866 | 0.8673 | 0.8878 | 0.7809 | 0.8962 | 0.9381 | 0.8588 | 0.8608 |

| EMOGI | 0.1723 | 0.2292 | 0.1160 | 0.1138 | 0.0496 | 0.0840 | 0.0793 | 0.0744 | 0.0716 | 0.0464 | 0.0312 | 0.1198 | 0.0754 | 0.1112 | 0.1292 |

| deepCDG | 0.9026 | 0.9276 | 0.9512 | 0.8870 | 0.8305 | 0.8718 | 0.8921 | 0.9075 | 0.8745 | 0.8688 | 0.8425 | 0.9227 | 0.9725 | 0.8384 | 0.9227 |

The best results are highlighted in bold.

Performance on independent test sets

We evaluate the performance of deepCDG on two independent cancer driver gene datasets to ensure the performance of deepCDG is not biased toward any specific cancer-related dataset. The two independent datasets include the OncoKB [42] consisting of 320 genes and the ONGene [43] consisting of 388 genes, and the details of the two independent datasets are shown in Section 4 in the Supplementary Materials. deepCDG and baseline models are trained using known cancer and non-cancer driver genes from  across different PPI networks. The trained models are separately applied for cancer gene prediction in these two independent datasets. After excluding genes overlapping with training genes, we consider predicted cancer driver genes which present in the independent sets as positive genes and remaining predicted cancer driver genes as negative genes. According to the results shown in Fig. 5, although the insufficient number of known true positive genes limits the predictive performance, deepCDG outperforms all other models and achieves the best performance on average.

across different PPI networks. The trained models are separately applied for cancer gene prediction in these two independent datasets. After excluding genes overlapping with training genes, we consider predicted cancer driver genes which present in the independent sets as positive genes and remaining predicted cancer driver genes as negative genes. According to the results shown in Fig. 5, although the insufficient number of known true positive genes limits the predictive performance, deepCDG outperforms all other models and achieves the best performance on average.

Figure 5.

Performance of deepCDG and baseline models across two independent sets based on OncoKB and ONGene.

Prediction of potential cancer driver genes

We apply deepCDG across six PPI networks to obtain predicted genes using a threshold of 0.99, removing overlapping and known cancer driver genes, ultimately identifying 148 predicted cancer driver genes which are shown in Table 1 in the Supplementary Materials. We compare these predictions against two literature-derived cancer gene datasets. One is CancerMine [44], a literature-mined resource for drivers, oncogenes and tumor suppressors in cancer. The other is the Candidate Cancer Gene Database (CCGD) [45], a database of cancer driver genes from transposon-based forward forward genetic screens. Overall, 86.5% (128/148) of predicted genes overlap with at least one dataset. Among these, 86.7% (111/128) are present in CancerMine, 82.8% (106/128) in CCGD, and 69.5% (89/128) overlap with both datasets. Experimental results demonstrate the strong association between deepCDG-predicted potential genes and the development and progress of cancer, thereby validating the model’s reliability.

Moreover, we compare the overlap of cancer driver genes identified by deepCDG and other identification methods shown in Fig. 6. We find that deepCDG predicts unique potential cancer driver genes undetected by other approaches. For instance, studies reveal COL7A1 as a novel biomarker candidate in many cancer types and a critical role in cancer aggressiveness [46]. MARCO is shown to promote non-small cell lung cancer progression by regulating the immunosuppressive function of tumor-associated macrophages through mechanisms closely linked to the IL37 signaling pathway [47, 48]. Elevated GNGT1 levels promote EMT activation and tumor microenvironment (TME) reprogramming, driving metastatic behavior and ultimately leading to adverse survival prognoses in LUAD patients [49]. These experimental results demonstrate the high credibility of cancer driver genes predicted by deepCDG.

Figure 6.

Upset diagram of the overlap of cancer driver genes identified by deepCDG and other identification methods.

Enrichment analysis

The results of Gene Ontology (GO) and Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis on predicted cancer driver genes identified by deepCDG are shown in Figs 7 and 8, which indicate that the candidate cancer driver genes participate in many important process of cancers. For instance, for GO biological process enrichment analysis, the process response to peptide hormone highlights the critical role of peptide hormone signaling in tumorigenesis and therapeutic targeting in lung cancer [50]. For GO cellular component enrichment analysis, collagen-containing extracellular matrix (ECM) in cancer underscores its dual structural and pro-tumorigenic roles. Tumor fibroblast-derived collagens promote the progression, metastasis, immune evasion, and metabolic reprogramming through dormancy modulation and immune interactions. ECM remodeling correlates with prognosis, while collagen-targeted therapies may inhibit metastasis and enhance treatment efficacy [51]. In GO molecular function enrichment analysis, enriched actin binding in prostate cancer correlates with cytoskeletal remodeling via actin-binding proteins, e.g. cofilin and fascin, driving invasion-metastasis cascades through filament dynamics [52]. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis reveal that PI3K-Akt signaling drives oncogenic growth and therapy resistance in cancers. Investigating approaches that focus on critical elements within the pathway could be helpful for advancing cancer therapeutics development [53].

Figure 7.

GO biological process, cellular component and molecular function enrichment analysis of top predicted genes.

Figure 8.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of top predicted genes.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Drug sensitivity assays assess tumor cell responsiveness by measuring cellular proliferation under chemotherapeutic drugs. Modulating specific apoptotic proteins to observe tumor responses could aid in developing more effective therapeutic strategies. We select the top ten predicted cancer driver genes and perform GDSC drug sensitivity experiments using Gene Set Cancer analysis (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA) [54, 55]. The drug sensitivity results on CPDB in Fig. 9 demonstrate that the drug associations for most genes, providing novel insights into cancer-specific therapeutic interventions. Notably, CP466722 reversibly inhibits ataxia-telangiectasiamutated (ATM) kinase, transiently enhancing tumor radiosensitivity through specific, non-toxic ATM blockade, thereby proposing a novel radiosensitization strategy for radiotherapy [56]. PIK-93 downregulates PD-L1 via ubiquitination, synergizes with anti-PD-L1 to enhance T-cell activation, inhibits tumor growth, and remodels the immunosuppressive TME in preclinical models [57]. The compound I-BET-762 exhibits dual anti-tumor efficacy by directly suppressing tumor cell proliferation and modulating immune cell dynamics across multiple organs in both in vitro and in vivo models, which positions it as a promising candidate for cancer interception and combinatorial treatment strategies [58].

Figure 9.

Correlation between drug sensitivity and mRNA expression for the top 10 predicted cancer driver genes on CPDB.

Gene module dissection in pan-cancer

GNNExplainer is a post-hoc explanation tool for our GCN model and it can interpret the contribution factors to cancer driver genes. Therefore, we employ GNNExplainer to detect gene modules revealing subgraphs of the most critical pairwise relationships of the cancer driver genes. Through the analysis of known cancer driver genes modules, we can explore their inter-module connections. For instance, alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation, X-linked (ATRX) and ATM are both verified cancer driver genes on BRCA. ATRX mutations impair chromatin remodeling, histone H3.3 deposition at repetitive regions, replication stress response, and DNA repair, promoting tumorigenesis and therapy resistance, particularly in gliomas [59]. The mutated ATM gene regulates cell cycle control, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and telomere maintenance, with its well-documented role as a cancer risk factor [60]. We construct the both ATRX and ATM modules, which are illustrated in Fig. 10. It can be found that the known cancer driver genes such as RADiation sensitive protein 51 (RAD51), bloom syndrome gene participate in the interactions of ATRX and ATM. Researches show that ATRX null cells are thought to rely on ATM associated pathways for DNA damage repair (DDR) and siRNA down-regulation of ATRX has been shown to result in impairment of RAD51 localization to BRCA1 which is key for DDR [61], which demonstrates the tight relations on cancer among ATRX, ATM, and RAD51. Meanwhile, PRKDC and SMC1A rank within deepCDG’s top potential predicted cancer driver genes are also participate in the interactions of ATRX and ATM, strongly suggesting their crucial role in the development and progress of cancers.

Figure 10.

Cancer gene module analysis between known cancer driver genes ATRX and ATM.

Conclusion

In this study, we propose a deep GCN-based multi-omics integration model named deepCDG. The deepCDG employs a pair of weight-shared GCN encoders to obtain gene representations based on multi-omics data and the PPI network. Subsequently, deepCDG designs an attention-based aggregation module to allocate importance weights across different omics for generating integrated feature representations. These fused representations comprehensively integrate semantic information from various omics while emphasizing inter-omics relationships, enabling a more holistic and profound understanding of genes. Finally, a GCN-based classifier is introduced to identify the candidate cancer driver genes. The results show that deepCDG demonstrates the stable effectiveness in both pan-cancer and cancer type-specific datasets across different PPI networks. We also verify the model robustness on two independent datasets. Compared with other models, deepCDG also exhibits computational efficiency advantages. Subsequent interpretability analyses reveal that genes predicted by deepCDG show strong cancer associations, with detected cancer gene modules displaying high consistency, thereby providing deeper insights in cancer pathogenesis. We believe our method offers enhanced applicability for cancer driver gene identification and could be extended to other biological research fields in future studies. With the development of high-throughput technologies, various interactome networks have been accumulated, including PPIs, metabolism and regulation. In the future work, we will extend our deep GCN model to multiplex networks to further improve the performance of cancer driver gene identification.

Key Points

A deep GCN-based multi-omics integration model for cancer driver genes, called deepCDG, is proposed.

deepCDG utilizes shared-parameter GCN-based encoders and an attention layer to generate integrated gene representations.

deepCDG performs better predictive performance of cancer driver genes compared to other baseline models.

deepCDG demonstrates outstanding robustness and computational efficiency compared to other baseline models.

deepCDG provides deeper insights in cancer pathogenesis by extracting cancer gene modules.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Yingzhuo Wu, School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072 Shaanxi, China.

Jialuo Xu, School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072 Shaanxi, China.

Junming Li, School of Software, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072 Shaanxi, China.

Jia Gu, Faculty of Data Science, City University of Macau, Macau, 999078 Macau, China.

Xuequn Shang, School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072 Shaanxi, China.

Xingyi Li, School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072 Shaanxi, China; Faculty of Data Science, City University of Macau, Macau, 999078 Macau, China; Shenzhen Research Institute of Northwestern Polytechnical University, Shenzhen, 518057 Guangdong, China.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [62202383, 62433016], Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation [2024A1515012602], the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2022YFD1801200], the State Key Laboratory for Animal Disease Control and Prevention Foundation [SKLADCPKFKT202407], the Macau Young Scholars Program [AM2024027], and the Science and Technology Development Fund of Macao [0002/2024/RIA1].

Data availability

All data is publicly available and the source code of model and evaluation can be freely downloaded from https://github.com/xingyili/deepCDG, https://github.com/xingyili/deepCDG-eval.

References

- 1. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013;500:415–21. 10.1038/nature12477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martincorena I, Campbell PJ. Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells. Science 2015;349:1483–9. 10.1126/science.aab4082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE. et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013;339:1546–58. 10.1126/science.1235122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li X, Hao J, Zhao Z. et al. PathActMarker: an R package for inferring pathway activity of complex diseases. Front Comp Sci 2025;19:193908. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P. et al. Nature 2013;499:214–8. 10.1038/nature12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tamborero D, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. OncodriveCLUST: exploiting the positional clustering of somatic mutations to identify cancer genes. Bioinformatics 2013;29:2238–44. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martincorena I, Raine KM, Gerstung M. et al. Universal patterns of selection in cancer and somatic tissues. Cell 2017;171:1029–1041.e21 e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leiserson MDM, Vandin F, Wu HT. et al. Pan-cancer network analysis identifies combinations of rare somatic mutations across pathways and protein complexes. Nat Genet 2015;47:106–14. 10.1038/ng.3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie M, Hwang T, Kuang R. Prioritizing disease genes by bi-random walk. In: Tan P-N, Chawla S, Ho CK et al. (eds.), Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2012, 292–303.

- 10. Cho A, Shim JE, Kim E. et al. MUFFINN: cancer gene discovery via network analysis of somatic mutation data. Genome Biol 2016;17:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li Y, Patra JC. Genome-wide inferring gene–phenotype relationship by walking on the heterogeneous network. Bioinformatics 2010;26:1219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jiang R. Walking on multiple disease-gene networks to prioritize candidate genes. J Mol Cell Biol 2015;7:214–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grover A, Leskovec J. node2vec: scalable feature learning for networks. KDD 2016;2016:855–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schulte-Sasse R, Budach S, Hnisz D. et al. Integration of multiomics data with graph convolutional networks to identify new cancer genes and their associated molecular mechanisms. Nat Mach Intell 2021;3:513–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peng W, Tang Q, Dai W. et al. Improving cancer driver gene identification using multi-task learning on graph convolutional network. Brief Bioinform 2022;23:bbab432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cui Y, Wang Z, Wang X. et al. SMG: self-supervised masked graph learning for cancer gene identification. Brief Bioinform 2023;24:bbad406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang T, Zhang SW, Xie MY. et al. A novel heterophilic graph diffusion convolutional network for identifying cancer driver genes. Brief Bioinform 2023;24:bbad137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li X, Xu J, Li J. et al. Towards simplified graph neural networks for identifying cancer driver genes in heterophilic networks. Brief Bioinform 2025;26:bbae691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peng W, Zhou Z, Dai W. et al. Multi-network graph contrastive learning for cancer driver gene identification. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng 2024;11:3430–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li X, Li J, Hao J. et al. Multiplex networks and pan-cancer multiomics-based driver gene identification using graph neural networks. Big Data Min Anal 2024;7:1262–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kipf TN, Welling M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907. 2016. 10.48550/arXiv.1609.02907 [DOI]

- 22. Li J, Zhang B, Lu G. et al. Generative multi-view and multi-feature learning for classification. Inf Fusion 2019;45:215–26. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen N, Zhu J, Sun F. et al. Large-margin predictive latent subspace learning for multiview data analysis. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2012;34:2365–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen X, Chen S, Xue H. et al. A unified dimensionality reduction framework for semi-paired and semi-supervised multi-view data. Pattern Recognit 2012;45:2005–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang W, Arora R, Livescu K. et al. On deep multi-view representation learning. In: Francis B, David B (eds.), Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, Volume 37. Lille, France: PMLR, 2015, 1083–92.

- 26. Xu J, Han J, Nie F. Multi-view feature learning with discriminative regularization. In: Sierra C (ed.), Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Melbourne, Australia: AAAI Press, 2017, 3161–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jing XY, Hu RM, Zhu YP. et al. Intra-view and inter-view supervised correlation analysis for multi-view feature learning. In: Brodley CE, Stone P (eds.), Proceedings of the 28th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Québec City, Québec, Canada: AAAI Press, 2014, 1882–9.

- 28. Ren Y, Gao Y, Du W. et al. Classifying breast cancer using multi-view graph neural network based on multi-omics data. Front Genet 2024;15:1363896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang J, Fu H, Xue F. et al. Multiview representation learning for identification of novel cancer genes and their causative biological mechanisms. Brief Bioinform 2024;25:bbae418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Repana D, Nulsen J, Dressler L. et al. The network of cancer genes (NCG): a comprehensive catalogue of known and candidate cancer genes from cancer sequencing screens. Genome Biol 2019;20:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sondka Z, Bamford S, Cole CG. et al. The COSMIC cancer gene census: describing genetic dysfunction across all human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 2018;18:696–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim J, So S, Lee HJ. et al. DigSee: disease gene search engine with evidence sentences (version cancer). Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:W510–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McKusick VA. Mendelian inheritance in man and its online version, OMIM. Am J Hum Genet 2007;80:588–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28:27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kamburov A, Wierling C, Lehrach H. et al. ConsensusPathDB—a database for integrating human functional interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:D623–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khurana E, Fu Y, Chen J. et al. Interpretation of genomic variants using a unified biological network approach. PLoS Comput Biol 2013;9:e1002886. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang JK, Carlin DE, Yu MK. et al. Systematic evaluation of molecular networks for discovery of disease genes. Cell Syst 2018;6:484–495.e5 e5. 10.1016/j.cels.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC. et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49:D605–12. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Razick S, Magklaras G, Donaldson IM. iRefIndex: a consolidated protein interaction database with provenance. BMC bioinformatics 2008;9:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ying Z, Bourgeois D, You J. et al. GNNExplainer: generating explanations for graph neural networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst 2019;32:9240–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lazareva O, Baumbach J, List M. et al. On the limits of active module identification. Brief Bioinform 2021;22:bbab066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips S. et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;1:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu Y, Sun J, Zhao M. ONGene: a literature-based database for human oncogenes. J Genet Genomics 2017;44:119–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lever J, Zhao EY, Grewal J. et al. CancerMine: a literature-mined resource for drivers, oncogenes and tumor suppressors in cancer. Nat Methods 2019;16:505–7. 10.1038/s41592-019-0422-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Abbott KL, Nyre ET, Abrahante J. et al. The candidate cancer gene database: a database of cancer driver genes from forward genetic screens in mice. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:D844–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Koca D, Séraudie I, Jardillier R. et al. COL7A1 expression improves prognosis prediction for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma atop of stage. Cancers 2023;15:2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. La Fleur L, Boura VF, Alexeyenko A. et al. Expression of scavenger receptor MARCO defines a targetable tumor-associated macrophage subset in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2018;143:1741–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. La Fleur L, Botling J, He F. et al. Targeting MARCO and IL37R on immunosuppressive macrophages in lung cancer blocks regulatory T cells and supports cytotoxic lymphocyte function. Cancer Res 2021;81:956–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fan LL, Wang XW, Zhang XM. et al. GNGT1 remodels the tumor microenvironment and promotes immune escape through enhancing tumor stemness and modulating the fibrinogen beta chain-neutrophil extracellular trap signaling axis in lung adenocarcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2025;14:239–59. 10.21037/tlcr-2024-1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moody TW. Peptide hormones and lung cancer. Panminerva Med 2006;48:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. De Martino D, Bravo-Cordero JJ. Collagens in cancer: Structural regulators and guardians of cancer progression. Cancer Res 2023;83:1386–92. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fu F, Yu Y, Zou B. et al. Role of actin-binding proteins in prostate cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024;12:1430386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. He Y, Sun MM, Zhang GG. et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021;6:425. 10.1038/s41392-021-00828-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu CJ, Hu FF, Xia MX. et al. GSCALite: a web server for gene set cancer analysis. Bioinformatics 2018;34:3771–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liu CJ, Hu FF, Xie GY. et al. GSCA: An integrated platform for gene set cancer analysis at genomic, pharmacogenomic and immunogenomic levels. Brief Bioinform 2023;24:bbac558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rainey MD, Zachos G, Gillespie DAF. Analysing the DNA damage and replication checkpoints in DT40 cells. Reviews and protocols in DT40 research. Subcellular Biochemistry 2006;40:107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lin CY, Huang KY, Kao SH. et al. Small-molecule PIK-93 modulates the tumor microenvironment to improve immune checkpoint blockade response. Science. Advances 2023;9:eade9944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang D, Leal AS, Carapellucci S. et al. Chemoprevention of preclinical breast and lung cancer with the bromodomain inhibitor I-BET 762. Cancer Prev Res 2018;11:143–56. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-17-0264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pang Y, Chen X, Ji T. et al. The chromatin remodeler ATRX: role and mechanism in biology and cancer. Cancers 2023;15:2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stucci LS, Internò V, Tucci M. et al. The ATM gene in breast cancer: its relevance in clinical practice. Genes 2021;12:727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. George SL, Lorenzi F, King D. et al. Therapeutic vulnerabilities in the DNA damage response for the treatment of ATRX mutant neuroblastoma. EBioMedicine 2020;59:102971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is publicly available and the source code of model and evaluation can be freely downloaded from https://github.com/xingyili/deepCDG, https://github.com/xingyili/deepCDG-eval.