ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Breakthrough infections (BTI) threaten the progress of the COVID-19 vaccination program towards pandemic control. To better understand the future vaccine, knowing the BTI in the general population over a while is important.

Aims and Objectives:

The study aimed to compare the BTI among the general population after 1 year of completion of the primary series of Covishield and Covaxin.

Materials and Methods:

This hospital-based prospective study was conducted among the general population beneficiaries of a COVID-19 vaccination center. Clients aged 18 years or above who had completed second vaccine dose were enrolled using systematic random sampling and followed up for 1 year. Using a semi-structured questionnaire, participants were telephonically interviewed within 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months of the second vaccine dose.

Results:

Out of 1682 participants who completed the study, 958 (57.0%) and 724 (43.0%) participants received Covaxin and Covishield, respectively. Twenty-nine (3.0%) Covaxin recipients and 25 (3.5%) Covishield recipients reported BTI after 1 year of follow-up with no statistically significant difference among both groups (p-0.624). The binary logistic regression model showed that participants with either diabetes or hypertension had 1.22 times the risk of BTI compared to those without comorbidities (aOR: 1.219, CI: 0.072–20.716, p-0.891). BTI was not significantly associated with the type of vaccine, sex, employment status, and age category of the participants.

Conclusion:

The study suggests that regardless of the type of vaccine received, the population will be at the same risk and require similar future containment strategies.

Keywords: COVID-19 Vaccines, Breakthrough Infections, Vaccination, BBV152 COVID-19 vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, Pandemics

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had devastating effects all over the world. Many vaccines were developed to combat COVID-19. India initiated the COVID-19 vaccination program on January 16, 2021. The primary vaccines used initially were CovishieldTM (manufactured by Serum Institute of India) and Covaxin® (manufactured by Bharat Biotech).[1] Clinical trials and mass vaccination campaigns of Covishield and Covaxin provided sufficient data about their efficacy and safety after emergency use authorization.[2,3,4] Given the emerging evidence, the gap between two doses of the Covishield vaccine was raised from 4–6 weeks to 12–16 weeks from May 13, 2021, in India (except for international travelers).[5] India carried out the world’s largest COVID-19 vaccination program through 3006 Covid vaccination centers across 28 states and 8 union territories. Over 1.7 billion doses of Covishield and 0.35 billion doses of Covaxin had been administered till September 1, 2022.[4]

Both vaccines reduce the severity of illness, but BTI are known to occur. None of the vaccines offer 100% protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection.[6,7,8] Some people may get infected and fall sick even after receiving two doses of the primary series of vaccines. Appearance of novel variants of SARS-CoV-2 increases the risk of reinfection. Available evidence on COVID-19 vaccination has indicated that COVID BTI have mild symptoms, fewer complications, and a lower hospitalization rate.[9] Similar findings have been reported from various Indian studies where the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and BTI was significantly reduced among vaccinated individuals.[8,9,10] Most of these studies were cross-sectional and conducted among healthcare workers.[11]

To better understand the vaccine in the future, it is important to know the BTI in the general population over time and this will also guide the primary healthcare physicians in pandemic preparedness. However, few studies have been conducted among the general public in India.[12,13] Tracking of BTI is vital primarily because it would serve as an important indicator to determine the impact of vaccination and help in decision-making regarding the need for additional booster doses given the changing virulence and mutations in the organism. No study compares the prevalence of BTI in the general population after Covishield (late schedule) versus Covaxin. Thus, the study aimed to compare the COVID-19 BTI among the general population after 1 year of completion of the primary series of vaccination with Covishield (late schedule) and Covaxin.

Methodology

This hospital-based prospective study was conducted among the general population beneficiaries for COVID-19 vaccination at Dr. B.R. Ambedkar State Institute of Medical Science, Mohali. It is a government medical college in north India providing Covishield and Covaxin as per the guidelines of the Government of India. This study compared the BTI in two groups: Covaxin and Covishield (late). Group Covishield (late) had persons who received a second dose of vaccine 12–16 weeks after the first dose. The ethical approval was obtained from the Institute’s Ethics Committee (AIMS/IEC/25/2021). Informed consent was taken from the study participants either telephonically or through WhatsApp via Google Forms after clarifying the study purpose and procedure. The ethics committee approved the consent procedure due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sample Size was calculated, assuming taking chances of BTI after Covishield – 7% and Covaxin – 4% [As no study was available on BTI of the general population, all available studies were conducted among health care providers].[6] The sample size was calculated using the following formula, n = (Zα/2 + Zβ)2*[p1 (1-p1) + p2 (1-p2)]/(p1-p1)2. Keeping the test power at 95% and 5% type I error rate, the sample size was calculated as 993, rounded off to 1000. With a loss to follow-up rate of 10%, the final sample size was 1100 per group.

Sampling strategies

In the institute, for every vaccination, client entries were done in a register where serial number, name, mobile number, type of vaccine, and category of the client (healthcare provider, front-line worker, senior citizen (>60 years), people below 45 years and, 46–60 years) were recorded. For Covishield (late schedule) and Covaxin, the beneficiaries who got a second dose of vaccine from June 2021 to December 2021 were considered.

Entry registers for both vaccines were taken and numbered. Every fifth beneficiary (systematic random sampling) was included till the desirable sample size was achieved. Clients aged 18 years or above who had completed a second vaccine dose were included. Pregnant and lactating females, clients who got COVID-19 infection before completing 14 days of the second dose, international travelers, health care providers, front-line workers, and clients who could not be contacted even after three attempts at the time of enrollment were excluded from the study. The beneficiaries were followed up for 1 year after the second dose of the vaccine.

Procedure

The information regarding sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, designation, co-morbidities, employment status), vaccine doses, and BTI was collected using a semi-structured questionnaire. Participants were interviewed telephonically between 2 weeks and 4 weeks (to rule out the possibility of COVID-19 infection within 14 days of the second dose), at 6 months and 12 months after the second dose of vaccine. They were informed about all the COVID-19 services available in the institute and were encouraged to notify the investigator about BTI telephonically or through WhatsApp. After enrollment, the information regarding BTI was collected for 1 year. It was collected via participant interviews or notified by the participants.

Operational definitions

Any participant who tested positive for COVID-19 using RTPCR during the study period was considered the case. The disease was classified as mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19 disease based on the guidelines provided by the Government of India.[14] Vaccine BTI was defined as when a person tested positive for COVID-19 as evident from the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA or antigen in the respiratory sample collected ≥ 14 days after vaccination with all recommended doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.[15]

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences v. 20 (IBM Corp., NY, USA) software after cleaning the data in Microsoft Excel. Participants who were not contacted or not cooperative during the study were removed from the analysis. Descriptive analysis was performed and categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The Chi-square test was used to assess the significance of BTI between the two vaccines. The predictors of breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection were suggested using the binary logistic regression model. A p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

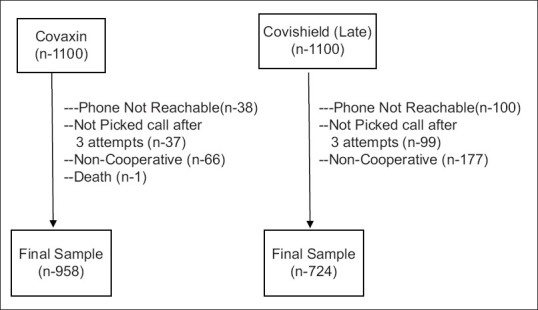

Out of 2200 participants, 1682 participants completed the study, as shown in Figure 1. Out of 1682 vaccinated participants, 958 (57.0%) participants received Covaxin and 724 (43.0%) participants received Covishield. Overall the mean age of vaccinated individuals was 42.4 years. The majority of study participants in both Covaxin (86.5%) and Covishield (87.4%) groups belonged to the 18–59-year age group. Males (54.9) were the predominant vaccine recipients for both vaccines. Comorbidities were present in 66 (3.9%) vaccinated participants with most of them suffering from hypertension and diabetes (1.9%) [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of the study participants*

| Variables | Covaxin n=958 | Covishield (late) n=724 | Total n=1682 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean±SD | 40.59±15.57 | 44.70±14.23 | 42.36±15.15 |

| Age groups | |||

| 18–59 years | 828 (86.5) | 633 (87.4) | 1461 (86.8) |

| >60–80 years | 114 (11.9) | 91 (12.6) | 205 (12.2) |

| >80 years | 16 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (1.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 460 (48.0) | 298 (41.2) | 758 (45.1) |

| Male | 498 (52.0) | 426 (58.8) | 924 (54.9) |

| Employment status | |||

| Working | 866 (90.4) | 648 (89.5) | 1514 (90.0) |

| Housewife/retired/non-working | 92 (9.6) | 76 (10.5) | 168 (10.0) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Present | 24 (2.5) | 42 (5.8) | 66 (3.9) |

| Absent | 934 (97.5) | 682 (94.2) | 1616 (96.1) |

| Type of comorbidities | |||

| Any chronic disease** | 24 (2.5) | 42 (5.8) | 66 (3.9) |

| Only diabetes | 02 (0.2) | 24 (3.3) | 26 (1.5) |

| Only hypertension | 05 (0.5) | 21 (2.9) | 26 (1.5) |

| Diabetes and hypertension | 10 (1.0) | 22 (3.0) | 32 (1.9) |

*Value in parenthesis indicates percentage. **Chronic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, asthma

The BTI was reported in 54 (3.2%) vaccinated participants and no statistically significant difference was found among both vaccine groups (χ²-0.241; p-0.624). Only two participants were reinfected again after BTI during the study period (one each from both vaccines). Among 958 participants vaccinated with Covaxin, 29 (3.0%) reported BTI with 2 (0.2%) hospitalizations and 1 (0.1%) death, which was due to non-COVID illness. Among 724 participants vaccinated with the late second dose of Covishield, 25 (3.5%) reported BTI with 4 (0.5%) hospitalizations and 1 (0.1%) required ICU/oxygenation [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of BTI in Covaxin and Covishield (late) vaccine (n=1682)

| Type of vaccination | Number of infections (within the first year of the second dose) | No. of persons who required hospitalization | No. of persons who required ICU/oxygenation | Death reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covaxin (n=958) | 29 (3.0%) | 02 (0.2%) | 00 (0.0) | 01 (0.1%) |

| Covishield (late) (n=724) | 25 (3.5%) | 04 (0.5%) | 01 (0.1%) | 00 (0.0) |

| Total (n=1682) | 54 (3.2%) | 06 (0.4%) | 01 (0.06%) | 01 (0.06%) |

The binary logistic regression model showed that participants administered with Covishield were at lower risk of BTI as compared to those vaccinated with Covaxin; though the results were found to be non-significant (aOR: 0.86, CI: 0.486–1.523, p-0.605). Participants who have diabetes or hypertension had 1.22 times the risk of BTI as compared to the people who did not have diabetes or hypertension (a: 1.219, CI: 0.072–20.716, p-0.891); though the results were found to be non-significant. BTI was not significantly associated with sex (aOR: 1.236, CI: 0.711–2.149, p-0.453), employment status (aOR: 1.097, CI: 0.451–2.666, p-0.838), and age category of the participants (p-0.873) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Adjusted binary logistic regression models for associated factors of SARS-CoV-2 BTI (n=1682)

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio | Standard error | CI (lower-upper) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1 (reference) | ||||

| Male | 1.236 | 0.282 | 0.711–2.149 | 0.453 | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Non-working | 1 (reference) | ||||

| Working | 1.097 | 0.453 | 0.451–2.666 | 0.838 | |

| Vaccine category | |||||

| Covaxin | 1 (reference) | ||||

| Covishield (late) | 0.860 | 0.291 | 0.486–1.523 | 0.605 | |

| Morbidity profile | |||||

| Non-hypertensive or diabetic | 1 (reference) | ||||

| Hypertensive or diabetic | 1.219 | 1.445 | 0.072–20.716 | 0.891 | |

| Any chronic diseases | |||||

| Chronic disease | 1 (reference) | ||||

| No chronic disease | 0.811 | 1.044 | 0.105–6.277 | 0.841 | |

| Age category | |||||

| >60 years | 1 (reference) | 0.873 | |||

| 40–59 Years | 0.787 | 0.464 | 0.317–1.953 | 0.605 | |

| 18–40 Years | 0.974 | 0.322 | 0.518–1.831 | 0.935 | |

Discussion

Our study compares the prevalence of COVID-19 BTI among the general population after a second dose of either Covishield (ChAdOx 1 nCoV-19 vaccine) or Covaxin (BBV-152). The majority of study participants in both Covaxin (86.5%) and Covishield (87.4%) groups belonged to the 18–59-year age group. Both vaccines were administered more to males than females. Various studies conducted among the vaccinated patients in India showed that the majority, i.e. approx. 70% of them, received Covishield, and the rest received Covaxin.[16,17]

The present study showed that only 3.2% of the vaccinated participants reported BTI in a year, with no statistically significant difference between Covishield and Covaxin groups. There was a wide variation in the prevalence of COVID-19 BTI in India. A North Indian study reported that 2% of the healthcare workers who were fully vaccinated with Covaxin were reinfected with COVID-19.[18] Another study found a higher prevalence (13%) of breakthrough symptomatic COVID-19 infection among the healthcare providers working in the chronic care medical facility.[6] A nationwide study showed that 23% of healthcare workers who had received either one or two doses of Covaxin or Covishield had BTI. The prevalence of BTI was lower among Covishield recipients (21%) compared to Covaxin (32%).[17]

In a study conducted among vaccinated individuals with COVID-19 symptoms reporting to various healthcare facilities in Odisha, more Covishield (87.2%) recipients were diagnosed with BTI than Covaxin (12.8%) recipients.[13] A cross-sectional study conducted among vaccinated beneficiaries of a COVID-19 vaccination center in Bihar reported that the prevalence of BTI was lowest among elderly and 45–59 years old adults (4.4%) compared to front-line workers (9.4%) and healthcare workers (13.3%).[12] However, the study has not commented on the vaccine individuals diagnosed with BTI received.

We found that few patients with BTI required hospitalization (0.4%) with no death reported due to COVID-19 infection. Singh et al.[12] reported that about 8% of patients with BTI received hospital management, while no casualties were reported. Dash et al.[13] observed that about 9.9% of patients were hospitalized after BTI, but there was no significant difference among the Covishield and Covaxin groups. In the present study, hospitalizations were higher among the participants who received Covishield than those who received Covaxin. In India, both Covaxin and Covishield show satisfactory efficacy against various novel variants of the COVID-19 virus; however, the efficacy of Covishield might decline in case of structural changes in the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein. A third phase experiment, a nationwide cross-sectional study and a multicentric hospital-based study in India, showed that the vaccine effectiveness of Covishield was superior to Covaxin. The vaccine effectiveness of both vaccines was similar against the delta strain and its sub-lineages. Vaccine effectiveness was significantly higher (94%) for an interval of 6–8 weeks between two doses of either vaccine than that for < 6 weeks.[17,19,20] However, there was no difference in the in-hospital mortality and disease severity between the recipients of Covishield or Covaxin in either the fully vaccinated or the partially vaccinated cohorts, as depicted by a study conducted in New Delhi, India.[21]

The present study showed that the participants without co-morbidity had a 17.5% lower risk of BTI compared to the people with co-morbidity, especially diabetes or hypertension. It has been well documented that the vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 decreases among those individuals who have comorbid conditions as compared to those who do not have any comorbidity.[22] Our findings are consistent with another study, which reported that vaccinated individuals with comorbidities experienced a higher risk of breakthrough COVID-19 infections than those without comorbidities.[23]

Strengths and limitations

The study has several strengths. The study compared 1-year post-vaccination BTI between Covishield and Covaxin, with adequate sample sizes. This study will guide primary care physicians in adapting public health practices regarding COVID-19 vaccination and helping them to manage any future pandemic. Infections were confirmed via RT-PCR, and data were collected through direct communication with participants and their relatives. However, the possibility of recall bias and research participant bias cannot be ruled out. The follow-up was done in 6 months due to a shortage of human resources. Participants who had a subclinical infection or tested RT-PCR negative but were confirmed or treated by the physician as COVID-19 were not considered for the analysis. The loss to follow-up was greater in the Covishield group. The study is likely to underestimate the true prevalence of BTI.

Conclusion

The prevalence of BTI in the Covaxin and Covishield groups was 3.0% and 3.5%, respectively. Participants who had a chronic disease were at a greater risk of BTI. The risk of BTI was not significantly associated with vaccine type, sex, employment status, and age of the participants. The study suggests if revaccination is needed in the future, regardless of the type of vaccine received, most participants will be at the same risk and require similar strategies for containment.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Nil.

References

- 1.Kumar VM, Pandi-Perumal SR, Trakht I, Thyagarajan SP. Strategy for COVID-19 vaccination in India: The country with the second highest population and number of cases. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6:60. doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00327-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ, Flaxman AL, Folegatti PM, Owens DR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdO×1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): A single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1979–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdO×1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: An interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asokan MS, Joan RF, Babji S, Dayma G, Nadukkandy P, Subrahmanyam V, et al. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines BBV152 (COVAXIN®) and ChAdO×1 nCoV-19 (COVISHIELD™) in seronegative and seropositive individuals in India: A multicentre, nonrandomised observational study. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2024;22:100361. doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2024.100361. doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2024.100361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Gap between two doses of Covishield Vaccine extended from 6-8 weeks to 12-16 weeks based on recommendation of COVID Working Group. 2021. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1718308 .

- 6.Tyagi K, Ghosh A, Nair D, Dutta K, Bhandari PS, Ansari IA, et al. Breakthrough COVID19 infections after vaccinations in healthcare and other workers in a chronic care medical facility in New Delhi, India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:1007–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niyas VKM, Arjun R. Breakthrough COVID-19 infections among health care workers after two doses of ChAdO×1 nCoV-19 vaccine. QJM Mon J Assoc Physicians. 2021;114:757–8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcab167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rana K, Mohindra R, Pinnaka L. Vaccine Breakthrough Infections with SARS-CoV-2 Variants. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2107808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2107808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaishya R, Sibal A, Malani A, Kar S, Prasad K H, SV K, et al. Symptomatic post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infections in healthcare workers–A multicenter cohort study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:102306. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102306. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das A, Khan S, Vidyarthi AJ, Gupta R, Mondal S, Singh S, et al. Breakthrough infection among healthcare personnel following exposure to COVID-19: Experience after one year of the world's largest vaccination drive. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2023;12:2328–37. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_529_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chahal S, Govil N, Gupta N, Nadda A, Srivastava P, Gupta S, et al. COVID related original research: Stress, coping and attitudinal change towards medical profession during COVID-19 Pandemic among health care professionals in India: A cross sectional study. Indian J Ment Health. 2020;7:255. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh CM, Singh PK, Naik BN, Pandey S, Nirala SK, Singh PK. Clinico-epidemiological profile of breakthrough COVID-19 infection among vaccinated beneficiaries from a COVID-19 vaccination centre in Bihar, India. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2022;32:15–26. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v32i1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dash GC, Subhadra S, Turuk J, Parai D, Rath S, Sabat J, et al. Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections among BBV-152 (COVAXIN®) and AZD1222 (COVISHIELD™) recipients: Report from the eastern state of India. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1201–5. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Clinical guidance for management of adult COVID-19 Patients. 2021. Available from: https://covid19dashboard.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/COVID19ClinicalManagementProtocolAlgorithm Adults19thMay2021.pdf .

- 15.Centre for Disease Control. COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections reported to CDC. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:792–93. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7021e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abhilash KP, Mathiyalagan P, Krishnaraj VR, Selvan S, Kanagarajan R, Reddy NP, et al. Impact of prior vaccination with Covishield™ and Covaxin®on mortality among symptomatic COVID-19 patients during the second wave of the pandemic in South India during April and May 2021: A cohort study. Vaccine. 2022;40:2107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishna B, Gupta A, Meena K, Gaba A, Krishna S, Jyoti R, et al. Prevalence, severity, and risk factor of breakthrough infection after vaccination with either the Covaxin or the Covishield among healthcare workers: A nationwide cross-sectional study. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2022;38((Suppl 1)):S66–78. doi: 10.4103/joacp.joacp_436_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malhotra S, Mani K, Lodha R, Bakhshi S, Mathur VP, Gupta P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection rate and estimated effectiveness of the inactivated whole virion vaccine BBV152 against reinfection among health care workers in New Delhi, India. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2142210. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42210. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das S, Kar SS, Samanta S, Banerjee J, Giri B, Dash SK. Immunogenic and reactogenic efficacy of Covaxin and Covishield: A comparative review. Immunol Res. 2022;70:289–315. doi: 10.1007/s12026-022-09265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatnagar T, Chaudhuri S, Ponnaiah M, Yadav PD, Sabarinathan R, Sahay RR, et al. Effectiveness of BBV152/Covaxin and AZD1222/Covishield vaccines against severe COVID-19 and B. 1.617. 2/Delta variant in India, 2021: A multi-centric hospital-based case-control study. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suri TM, Ghosh T, Arunachalam M, Vadala R, Vig S, Bhatnagar S, et al. Comparison of in-hospital COVID-19 related outcomes between COVISHIELD and COVAXIN recipients. Lung India. 2022;39:305–6. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_141_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefan N. Metabolic disorders, COVID-19 and vaccine-breakthrough infections. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18:75–6. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00608-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smits PD, Gratzl S, Simonov M, Nachimuthu SK, Goodwin Cartwright BM, Wang MD, et al. Risk of COVID-19 breakthrough infection and hospitalization in individuals with comorbidities. Vaccine. 2023;41:2447–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]