Abstract

Background

Data on the prevalence and burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) are limited in the United States (US).

Objective

To estimate the burden, clinical profile, and prevalence of diagnosed CSU in the United States.

Methods

Data from respondents with physician-diagnosed CSU were collected from the 2019 National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS). Outcomes assessed included diagnosed CSU prevalence, demographics, clinical profile, and burden using the 36-item Short Form Survey version 2 (SF-36v2; physical and mental component summary [PCS and MCS] scores), Short-Form 6 Dimension (SF-6D) and EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) utility scores, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire, and healthcare resource utilization over the past 6 months.

Results

Among 74,994 respondents, 815 reported physician-diagnosed chronic urticaria, with 635 (77.9%) having CSU. The weighted prevalence (95% confidence interval) of diagnosed CSU was 0.78% (0.78%–0.78%). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age at diagnosis was 37.0 (17.1) years, and 51.7% of respondents were female. Lower (worse) MCS and PCS scores were observed than in the overall NHWS population. The mean (SD) SF-6D and EQ-5D health utility scores were 0.54 (0.14) and 0.62 (0.34), respectively. The mean (SD) DLQI score was 13.8 (11.2), with more than 74.0% of respondents reporting anxiety (GAD-7 ≥5) and depression (PHQ-9 ≥5). Mean percent (SD) scores for absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment were 36.5% (26.1), 67.2% (34.9), 73.1% (34.2), and 62.6% (34.1), respectively. The percentage of patients visiting any healthcare provider, an emergency department, or requiring hospitalization was 96.5%, 60.2%, and 55.9%, respectively.

Conclusion

This real-world study reveals a higher prevalence of diagnosed CSU in the United States than previously reported, along with significant humanistic and economic burdens.

Keywords: Chronic spontaneous urticaria, Prevalence, Anxiety, Depression, Absenteeism, Presenteeism

Introduction

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a recurrent inflammatory skin condition characterized by unpredictable and persistent hives and/or angioedema lasting over 6 weeks.1 CSU significantly impacts patients’ daily lives, necessitating a comprehensive assessment of its prevalence and associated burden.

Understanding the epidemiology and variable natural history of CSU is crucial for effective management and improving patient outcomes. Globally, the point prevalence of CSU, depending on study design, varies from 0.02% to 2.7%.2,3 In the United States (US), studies based on insurance claim databases reported an estimated yearly prevalence of diagnosed CSU at 0.08%–0.11%.4,5 A cross-sectional study using data from electronic health records reported a higher point prevalence of CSU at 0.23% in the United States.6 Another US study using the National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) reported the prevalence of diagnosed CSU (based on diagnosed chronic hives as a proxy) at 0.4%.7 The variability in the prevalence of CSU may be due to differences in data sources (claims vs surveys), study designs, variable diagnostic criteria used to define the disease, and the absence of specific diagnostic codes for CSU.2,3 Moreover, researchers have often used the less specific term “chronic urticaria/hives” as a proxy for CSU when reporting the prevalence estimates.7

Patients with CSU also experience —— besides the core symptoms such as pruritus (itch), wheals (hives), angioedema, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression —— a negative impact on daily activities with an overall negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).7, 8, 9, 10 In addition to the humanistic burden, CSU also imposes a considerable economic burden on patients with high use of healthcare resources, including specialist visits, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and productivity loss.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

This study aimed to provide a robust assessment of the clinical profile, prevalence, and burden of CSU in the United States, incorporating both the humanistic and economic dimensions from the patient perspective.

Methods

Study design, data source

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2019 NHWS, a nationally representative sample of the US population.7 The NHWS is a cross-sectional, self-administered, internet-based questionnaire survey designed to reflect health in the general adult population.8,12 Data were collected from adults (≥18 years of age) using opt-in online survey panels with quota sampling to ensure representativeness at the national level.12 The Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN) reviewed the study protocol and questionnaire for the NHWS and approved the exemption. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent for participation in this study.

Patient population and prevalence of diagnosed CSU

Adults who self-reported receiving a diagnosis of CSU from a healthcare provider in the past 12 months were included in the analysis for all outcomes and for the calculation of the weighted 12-month prevalence of diagnosed CSU.

Three items from the NHWS were used to identify participants for this analysis. Participants were asked if they had ever experienced chronic hives (chronic urticaria; ≥6 weeks; yes/no). Subsequently, participants were asked what type of chronic hives they experienced in the past 12 months, with CSU (ie, unknown cause of rash), chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU; specific trigger caused the rash), or “don't know” as responses. Finally, participants who indicated they had experienced CSU or CIndU were asked if they had been diagnosed by a healthcare provider (yes/no).

Sociodemographic, general health, and clinical characteristics

The NHWS variables collected as part of the sociodemographic data were age, gender, annual household income, employment status, insurance type, and general health characteristics, including body mass index. Clinical characteristics reported were age at diagnosis, type of diagnostician, and burden of comorbidities using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, score range: 0–2+).13 To evaluate disease control, the CSU cohort completed the urticaria control test (UCT), with a UCT score of ≤11 indicating poorly controlled urticaria.14 Treatments, including prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medication were also reported. Respondents were also asked to report the “all-cause” out-of-pocket costs incurred in an average month.

Outcome measures

Humanistic and economic outcomes were assessed among the respondents with diagnosed CSU and the overall NHWS sample population. HRQoL was assessed using the 36-item Short Form Survey version 2 (SF-36v2), which is a generic 36-item health survey instrument with a recall period of 4 weeks.15 Two summary scores were calculated: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS).15,16 The MCS and PCS scores can be interpreted relative to the general population average of 50 and standard deviation (SD) of 10, with higher summary scores indicating better HRQoL.17

The SF-36v2 was used to generate the Short-Form 6 Dimension (SF-6D) health utility score. The SF-6D provides a meaningful measure of general health status and yields a summary score ranging from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better health status.18,19 Respondents also completed the five-level EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) questionnaire,20 which comprises a descriptive 5-dimension system and a visual analog scale (EQ-VAS).21 A single utility score assessing general health status ranging from 0 to 1 can be derived, with higher scores indicating better health status. The EQ-VAS indicates self-rated health at the moment of completion on a vertical line, with the score ranging from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health).22

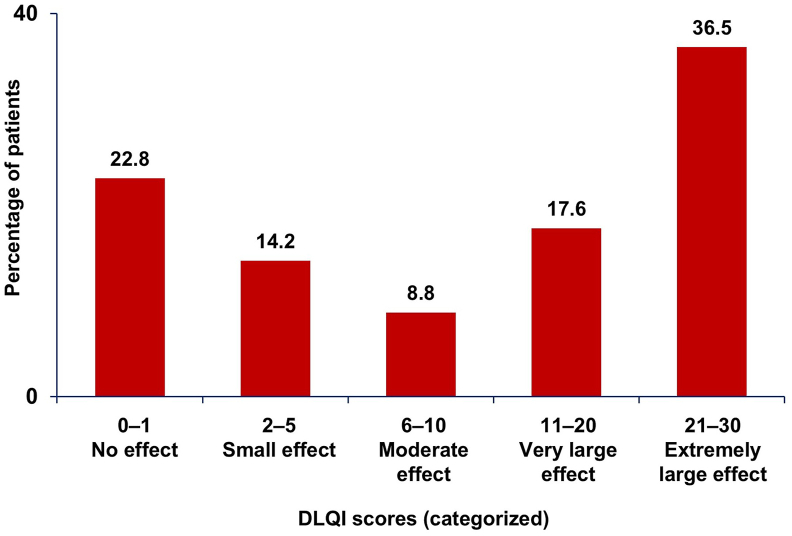

Dermatology-related quality of life was assessed using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a 10-item questionnaire with a 7-day recall period and overall score ranging from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating severe impact on patients' lives.23 The scores were categorized in bands representing “no effect” (0–1), “small effect” (2–5), “moderate effect” (6–10), “very large effect” (11–20), and “extremely large effect” (21–30) on patients’ lives.24 The DLQI scores were also dichotomized as DLQI ≤10 and DLQI >10.25

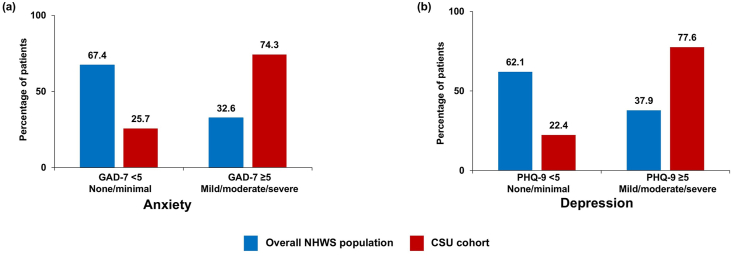

Anxiety was assessed using General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), a 7-item measure with scores ranging from 0 to 21.26 Depression was assessed using Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a nine-item measure with scores ranging from 0 to 27.27 GAD-7 and PHQ-9 are widely validated measures with a recall period of 2 weeks. The summary scores for both can be dichotomized so that scores of <5 indicate none/minimal anxiety/depression, while scores of ≥5 indicate severe anxiety/depression.28

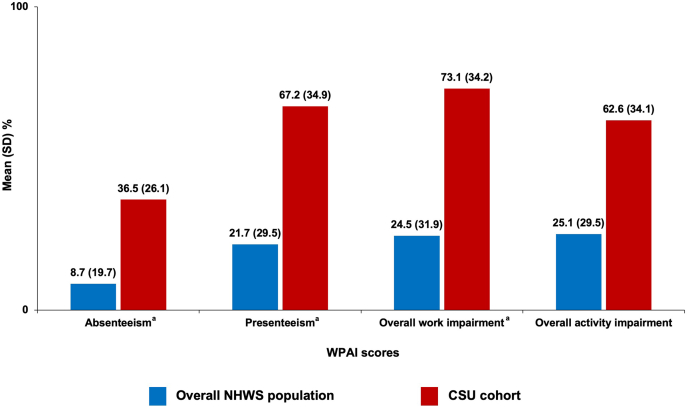

Work and non-work activity impairment was evaluated using the six-item Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire general health version, which has a recall period of 7 days. WPAI scores are calculated and reported as percent impairment as follows: absenteeism (% of work time missed due to health state), presenteeism (% of work impairment while working due to health state), overall work impairment (a composite score of absenteeism and presenteeism), and overall non-work activity impairment.29 Absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment were assessed among employed respondents only.

“All-cause” healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) was assessed by reporting the percentage and mean number of visits to healthcare providers and emergency departments, as well as hospitalizations, in the past 6 months.

Statistical analysis

The 12-month weighted prevalence of diagnosed CSU was calculated and reported in this study. The weights were constructed to account for the distribution of sex, age, and race/ethnicity in the United States using 2018 population estimates from the Current Population Survey.30 A weighted prevalence estimate with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) was presented. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the patient profile and reported outcomes of the CSU cohort, and results were reported as mean (SD) frequency. The humanistic and economic outcomes of patients with CSU were descriptively compared to the overall general NHWS population. All data management and analyses were conducted using SPSS 23.0 and/or SAS 9.4.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the overall NHWS population

A total of 74,994 respondents participated in the 2019 US NHWS. The mean (SD) age of participants in the overall US sample was 47.6 (17.3) years and 56.9% were female. More than 50% of the respondents had a university degree, 59.4% were employed, and 54.3% had an annual household income between $25,000 and $100,000. The majority (86.4%) of the respondents had a CCI score of 0, while 7.4% had a score of 2+. Almost 89% of the respondents had insurance, with 51.6% having commercial insurance, while 22.0% had Medicare insurance at the time of the survey. In an average month, 80.2% of the overall respondents reported all-cause ≤$100 out-of-pocket costs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, general health, and clinical characteristics of the overall NHWS population and the physician-diagnosed CSU cohort.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Overall NHWS population (N = 74,994) | CSU (n = 635) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | ||

| At data collection | 47.6 (17.3) | 39.6 (12.6) |

| At diagnosis | NA | 37.0 (17.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 42,664 (56.9) | 328 (51.7) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Asian | 5438 (7.3) | 34 (5.4) |

| Black/African American | 8326 (11.1) | 102 (16.1) |

| White, Hispanic | 8401 (11.2) | 112 (17.6) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 49,694 (66.3) | 371 (58.4) |

| Other | 3135 (4.2) | 16 (2.5) |

| Regional census, n (%) | ||

| North-East | 14,470 (19.3) | 135 (21.3) |

| Midwest | 15,644 (20.9) | 143 (22.5) |

| South | 27,810 (37.1) | 212 (33.4) |

| West | 17,070 (22.8) | 145 (22.8) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Less than a university degree | 37,051 (49.4) | 242 (38.1) |

| University degree | 37,793 (50.4) | 392 (61.7) |

| Declined to answer | 150 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Employed | 44,580 (59.4) | 504 (79.4) |

| Retired | 15,480 (20.6) | 48 (7.6) |

| Not employed | 8211 (10.9) | 34 (5.4) |

| Homemaker | 4215 (5.6) | 31 (4.9) |

| Disability (long-term/short-term) | 2508 (3.3) | 18 (2.8) |

| Annual household income, n (%) | ||

| Low: <$25,000 | 11,410 (15.2) | 58 (9.1) |

| Medium: $25,000 to $100,000 | 40,735 (54.3) | 273 (43.0) |

| High: $100,000+ | 19,251 (25.7) | 292 (46.0) |

| Declined to answer | 3598 (4.8) | 12 (1.9) |

| All-cause out-of-pocket costs in an average month, n (%) | ||

| $0 to $100 | 60,181 (80.2) | 407 (64.1) |

| $101 to $500 | 4961 (6.6) | 156 (24.6) |

| $501 to $1000 | 710 (0.9) | 37 (5.8) |

| $1001 or more | 411 (0.5) | 21 (3.3) |

| Do not know | 8731 (11.6) | 14 (2.2) |

| Health insurance status, n (%) | ||

| Has insurance | 66,484 (88.7) | 570 (89.8) |

| Commercial | 38,689 (51.6) | 434 (68.3) |

| Medicare | 16,499 (22.0) | 72 (11.3) |

| Medicaid | 5413 (7.2) | 45 (7.1) |

| Military | 2002 (2.7) | 11 (1.7) |

| Other | 3881 (5.2) | 8 (1.3) |

| Does not have insurance | 8510 (11.3) | 65 (10.2) |

| General health characteristics | ||

| CCI score, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 64,796 (86.4) | 327 (51.5) |

| 1 | 4662 (6.2) | 59 (9.3) |

| 2+ | 5536 (7.4) | 249 (39.2) |

| Body mass index, n (%) | ||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 2594 (3.5) | 103 (16.2) |

| Normal weight (18.5 to <25.0 kg/m2) | 24,749 (33.0) | 178 (28.0) |

| Overweight (25 to <30.0 kg/m2) | 21,970 (29.3) | 119 (18.7) |

| Obese (30.0 kg/m2 and above) | 21,926 (29.2) | 136 (21.4) |

| Declined to answer | 3755 (5.0) | 99 (15.6) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Disease duration (years), mean (SD) | NA | 11.0 (12.6) |

| Angioedema in the past 3 months | ||

| Experienced angioedema, n (%) | NA | 312 (49.1) |

| Number of angioedema events, mean (SD) | NA | 3.9 (5.7) |

| Diagnosticiana, n (%) | ||

| Primary care physician/general practitioner | NA | 73 (36.3) |

| Nurse practitioner/physician assistant | NA | 10 (5.0) |

| Allergist | NA | 80 (39.8) |

| Dermatologist | NA | 33 (16.4) |

| Other | NA | 5 (2.5) |

| UCT, n (%) | ||

| Poorly controlled (UCT ≤11) | NA | 489 (77.0) |

| Well controlled (UCT ≥12) | NA | 146 (23.0) |

| Treatment patterns, n (%) | ||

| Treatment at time of surveyb | NA | 338 (53.2) |

| Prescription medication | NA | 61 (18.0) |

| OTC medication | NA | 312 (92.3) |

| Prescription and OTC medication | NA | 35 (10.4) |

| Prescribed medication classes | ||

| H1-antihistamines | NA | 43 (12.7) |

| Oral corticosteroids | NA | 14 (4.1) |

| Cyclosporine | NA | 6 (1.8) |

| Biologics | NA | 5 (1.5) |

| Other immunosuppressants | NA | 5 (1.5) |

| Doxepin | NA | 2 (0.6) |

| Other medications | NA | 20 (5.9) |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; NA, not available; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey; OTC, over-the-counter; SD, standard deviation; UCT, urticaria control test.

The proportions calculated for diagnosticians were calculated with the number of missing responses (n = 434) excluded from the denominator. Therefore, the base sample for the proportion is the sum of respondents who provided a valid response (n = 201).

Not mutually exclusive.

Prevalence of diagnosed CSU in the United States

Among 74,994 respondents from the US 2019 NHWS, a total of 1105 had experienced symptoms of chronic urticaria in the past 12 months, of whom 815 (73.8%) were diagnosed with chronic urticaria. Among respondents with chronic urticaria, 635 (77.9%) reported diagnosed CSU (Fig. 1). The 12-month weighted prevalence (95% CI) of diagnosed CSU was estimated at 0.78% (0.78%–0.78%) in the United States.

Fig. 1.

Type of chronic urticaria among NHWS respondents. aSymptoms include itch, hives, and/or angioedema for more than 6 weeks. bDiagnosed by a physician. CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; CIndU, chronic inducible urticaria; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of CSU respondents

Among respondents with physician-diagnosed CSU (n = 635), 51.7% were female, and the mean (SD) age at diagnosis and data collection was 37.0 (17.1) and 39.6 (12.6) years, respectively. The mean (SD) disease duration was 11.0 (12.6) years. More than 50% of the respondents were White, non-Hispanic, and 56.2% belonged to Southern or Western regions. About 62.0% of the respondents had a university degree, 79.4% were employed, 46.0% reported an annual household income of more than $100,000, and 64.1% of the respondents reported ≤$100 out-of-pocket costs in an average month, which was lower compared to the overall NHWS sample population (Table 1).

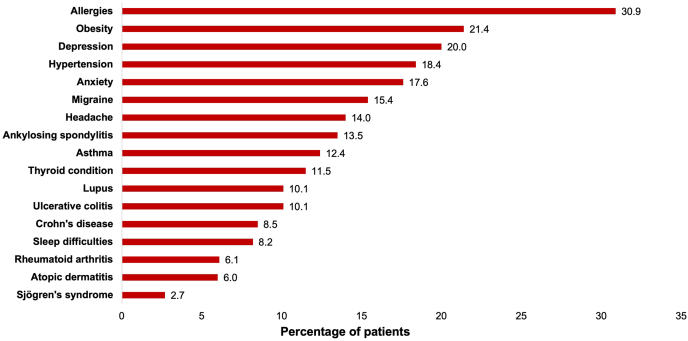

Approximately half (49.1%) of the respondents reported experiencing angioedema in the past 3 months, with the mean (SD) number of angioedema events in the past 3 months being 3.9 (5.7). Allergists (39.8%), followed by primary care physicians (36.3%) and dermatologists (16.4%), were the most frequent diagnosticians responsible for CSU diagnosis. UCT scores show that 77.0% of respondents had a score ≤11, indicating poorly controlled CSU. Only 53.2% of the respondents were receiving treatment at the time of the survey, of whom 18.0% were using prescription medication, and 92.3% were using OTC medication. H1-antihistamines (12.7%), followed by oral corticosteroids (4.1%) and cyclosporine (1.8%), were the most frequently prescribed medication classes (Table 1). Among biologics, omalizumab was prescribed to 1.6% of respondents with CSU. The most commonly diagnosed comorbidities (>10%) were allergies, metabolic disorders (obesity and hypertension), mental health conditions (depression and anxiety), neurological disorders (migraine and headache), asthma, and autoimmune conditions (ankylosing spondylitis, thyroid conditions, lupus, and ulcerative colitis; Fig. 2). A CCI score of 2+ was reported in 39.2% of respondents with CSU and 7.4% of the overall NHWS population.

Fig. 2.

Comorbidities among the physician-diagnosed CSU cohort.

Allergies included all types of allergies, including food allergy and allergic rhinitis. Participants self-reported receiving a diagnosis for an allergy.

CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria

Health-related quality of life

Of respondents with CSU, the mean (SD) MCS and PCS scores were 36.3 (10.5) and 40.1 (10.0), respectively, reflecting the mental and physical impact of CSU. The mean (SD) SF-6D and EQ-5D scores were low at 0.54 (0.14) and 0.62 (0.34), respectively, showing an impairment of general status. The MCS, PCS, and utility scores were lower (worse) than in the overall NHWS population (Fig. 3). The mean (SD) EQ-VAS score in the CSU cohort was lower (68.5 [27.8]) as compared to the overall NHWS population (75.4 [22.5]).

Fig. 3.

a) MCS and PCS scores and b) Health utility scores among the overall NHWS population and the physician-diagnosed CSU cohort. Higher scores in MCS/PCS and SF-6D/EQ-5D indicate better HRQoL and health status, respectively. CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SD, standard deviation; SF-6D, Short-Form 6 Dimension; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey

The mean (SD) DLQI score was 13.8 (11.2), with 54.2% of respondents having a score >10. More than one-third (36.5%) of respondents had a DLQI score between 21 and 30, indicating an extremely large effect on the patient's life (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

DLQI score bands for the diagnosed CSU cohort. Categorized DLQI scores: DLQI (0–1): No effect; DLQI (2–5): Small effect; DLQI (6–10): Moderate effect; DLQI (11–20): Very large effect; DLQI (21–30): Extremely large effect. CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index

Mild/moderate/severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥5) and depression (PHQ-9 ≥5) was approximately two times more frequently reported in the CSU cohort than in the overall NHWS population (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mental health: a) Anxiety and b) Depression among the overall NHWS population and the physician-diagnosed CSU cohort. GAD-7 <5 and PHQ-9 <5 indicate none/minimal anxiety and depression, respectively. GAD-7 ≥5 and PHQ-9 ≥5 indicate mild/moderate/severe anxiety and depression, respectively. CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder-7; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9

Work productivity and activity impairment

Among employed respondents, the mean percentage (SD) of absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment was 36.5% (26.1), 67.2% (34.9), and 73.1% (34.2), respectively. The percentage of overall activity impairment was 62.6% (34.1). When compared to the overall NHWS cohort, CSU respondents experienced a higher impact (worse scores) on work and activities (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Work productivity and activity impairment over the past 7 days among the overall NHWS population and the physician-diagnosed CSU cohort. aAssessed among employed respondents only; higher scores mean higher impairment. CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey; SD, standard deviation; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

Healthcare resource utilization

In terms of all-cause HCRU, 96.5% of the respondents had visited any healthcare provider in the past 6 months, and 60.2% reported visiting an emergency department a mean (SD) of 8.6 (11.9) and 3.7 (5.0) times, respectively. Meanwhile, 55.9% of respondents had been hospitalized in the past 6 months, with the mean (SD) number of hospitalizations being 4.4 (9.8). HCRU was substantially higher in the CSU respondent cohort, with approximately four times higher emergency department visits and six times higher hospitalizations as compared to the overall NHWS population (Table 2).

Table 2.

All-cause HCRU in the past 6 months among the overall NHWS population and the physician-diagnosed CSU cohort.

| Any healthcare provider visits | Overall NHWS population (N = 74,994) | CSU cohort (n = 635) |

|---|---|---|

| Visited, % | 77.3 | 96.5 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 4.7 (6.1) | 8.6 (11.9) |

| General practitioner | ||

| Visited, % | 49.2 | 48.7 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.5) | 2.2 (2.3) |

| Allergist | ||

| Visited, % | 4.0 | 29.6 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 2.4 (3.7) | 2.8 (4.3) |

| Dermatologist | ||

| Visited, % | 10.7 | 19.2 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.9 (1.5) |

| Emergency department visits | ||

| Visited, % | 14.5 | 60.2 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 2.1 (3.1) | 3.7 (5.0) |

| Hospitalizations | ||

| Hospitalized, % | 9.7 | 55.9 |

| Number of hospitalizations, mean (SD) | 2.4 (4.9) | 4.4 (9.8) |

Note: mean number of visits is among those who saw the corresponding healthcare provider in the past 6 months. CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

Studies have reported the point prevalence of chronic urticaria in the United States at 0.10%–0.23%.2,6 However, the epidemiological estimates of CSU specifically are limited in the United States, and these estimates tend to vary depending on the underlying data source. Given the paucity of published evidence, there is a need to accurately assess the prevalence and burden of CSU on the affected individuals in the US healthcare system. This study aimed to fill this gap and contribute to the understanding of CSU epidemiology in the United States, along with its associated humanistic and economic burden, using NHWS data. The NHWS provides real-world, patient-reported data of more than 200 conditions, and the representation of NHWS data has been validated in the United States.31,32

The weighted prevalence of diagnosed CSU in the present study was estimated at 0.78%, higher than previously reported in a study by Vietri et al.7 (0.4%), which was based on the reporting of chronic hives in the US NHWS data from over 10 years ago. It may be expected that chronic hives, as a less specific term, would be more prevalent than CSU. However, a meta-analysis using time-trend evaluations showed an increasing prevalence of chronic urticaria over time,2 which may be reflected in the increase in prevalence in this study compared to that by Vietri et al.7 The estimated prevalence in this study was also considerably higher in comparison to studies by Zazzali et al4 (0.08%) and Broder et al5 (0.11%) in the United States. While the present study reported prevalence estimates based on patient self-reported physician-diagnosed CSU, the studies by Zazzali et al4 and Broder et al5 are based on insurance claims that are generated for billing purposes and may lack clinical information, leading to the under-coding of this condition. This inconsistency may be attributed to variable diagnostic criteria and a lack of specific International Classification of Diseases codes for CSU.33

Furthermore, studies using claims databases, which typically only include data on prescription medication, have reported lower CSU prevalence estimates, as the majority of these patients continue treatment with OTC medication and, therefore, patients with active disease do not get recorded in the system. In comparison, the present study uses a more representative cohort of patients from the NHWS who reported receiving a diagnosis of CSU from a healthcare provider; these patients could have been receiving prescription medication, OTC medication, or no active treatment. This allows for a more accurate estimate of CSU prevalence, which more realistically captures the larger population living with CSU, such as those who, despite symptoms, do not use medication, or those who use OTC medication and are therefore not present in the claims databases.

Globally, the prevalence of diagnosed CSU reported in this study was higher compared to studies using chronic urticaria as a proxy for CSU, such as those conducted in Brazil (0.41%)10 and five European countries (0.51%).11 The prevalence of CSU in the present study was also higher when compared to other database studies from Italy (0.02%–0.38%)33 and South Korea (0.16%–0.45%).34 However, these studies used data collected 10 or more years ago, and, as previously noted, the prevalence of chronic urticaria is increasing.2 The US prevalence was lower compared to the overall prevalence in China (1.29%) but similar to the point prevalence of urticaria (0.75%).35

The sociodemographic characteristics of the CSU population in the present study were consistent with those of the previous studies, which had more than 50% female participants.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 This finding was substantiated by a systematic review and meta-analysis, which reported a higher prevalence of chronic urticaria among females.2 Patients with CSU report a variety of comorbidities such as allergies, anxiety, depression, and autoimmune diseases, which is consistent with other published studies. Overall, the burden of comorbidities was higher than the NHWS general population, as reflected by the CCI scores.3 Additionally, compared to the overall US population, anxiety, depression, asthma, and autoimmune conditions including ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, and rheumatoid arthritis were more prevalent in the CSU study population (0.3%–12.5%, vs 6.1%–20.0%),36, 37, 38 and obesity was less prevalent (40.3% vs 21.4%).39 Although the occurrence of allergies was relatively high in the CSU population (30.9%), it is comparable to the proportion of individuals in the general US population with an allergy (31.8%; seasonal allergy, eczema, or food allergy).40

Angioedema in CSU remains underdiagnosed as well as under-reported and has been negatively associated with HRQoL, disease control, and productivity.41, 42, 43 Approximately half (49.1%) of the respondents with CSU experienced angioedema in this study, which is in line with the published literature indicating that around 50% of patients with CSU report concomitant angioedema.41 The prevalence of angioedema in this study was also comparable with the ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II, and GLACIAL clinical trials and the ASSURE-CSU study.42,43 Maurer et al. also reported that a significantly higher proportion of patients with CSU experienced angioedema in Central and South America (50.8%) compared to European regions (46.1%).44

More than 75% of the study participants had poorly controlled CSU, aligning with the results of the AWARE and DERMLINE survey studies, which reported that three-quarters of patients had uncontrolled disease.45,46 Another study reported that significantly greater proportions of patients with CSU in Central and South America experienced uncontrolled disease compared to European countries.44

Guidelines suggest referral to a specialist, as necessary, following review of a patient's medical history, physical examination, or basic testing.1 As highlighted previously, 77.0% of patients in this survey experienced poorly controlled disease, and 60.2% required emergency department visits. However, despite CSU being a chronic dermatological condition, only 16.4% received their diagnosis from a dermatologist, and only 19.2% reported visits to a dermatologist in the past 6 months. Similarly, in a real-world US cohort identified through a claims database, few patients reported dermatologist visits, with just 10.7% and 21.5% with dermatologist visits pre- and post-CSU diagnosis, respectively.47 The global Urticaria Voices survey further highlights the barriers to accessing specialized care, and gaps in the healthcare system, with patients reporting waiting a mean of two years between symptom onset and diagnosis, during which time they consult a mean of 6.1 physicians.48 The study concluded that there remains a need for improved multidisciplinary and specialized care for the treatment of patients with CSU.48 One component required to improve CSU care is increased education for both patients and physicians.49 Additionally, optimizing patient–provider communication and shared decision-making, incorporating the patient's journey with CSU, may result in improved long-term disease management.49,50

Moreover, only half of the patients were receiving treatment at the time of this survey, of whom 12.7% were prescribed H1-antihistamines, the mainstay of guideline-recommended treatments.1 Previous real-world studies have also reported a large proportion (54.1%–60.3%) of patients with CSU not currently receiving any treatment.46,51 Despite the high burden of the disease, CSU largely remains undertreated, resulting in poorly controlled disease and outcomes.46 Although treatment guidelines state that corticosteroids should be reserved for acute exacerbations only (short courses ≤10 days),1 real-world studies suggest frequent deviations from these guidelines, with up to 75% of patients with CSU receiving corticosteroids.5,47,52 Additionally, although designated as second-line treatment,1 the prescription of biologics remains low (1.5%).5,47

The pathology of CSU is not fully understood, with some providers potentially providing their patients with misinformation,49,53 and as noted previously, a lack of effective treatment options and significant diagnostic delays.48 All of this can lead to frustration, and result in patients attempting to self-diagnose and seek alternative treatment options, often using internet sources in place of seeking in-person care.54,55 Patients may also erroneously search for an external trigger, leading to anxiety and unnecessary avoidance of the assumed trigger, adding to the patient burden.49,55,56 In addition, studies suggest that undertreatment may be due to patient and physician treatment dissatisfaction and safety concerns, a lack of awareness or familiarity with advanced treatment among providers, or the financial burden associated with treatment that is faced by patients.46,49,57 Together, these situations highlight the urgent need for viable treatment options, especially for patients who remain symptomatic following first- and second-line treatment.58 Thus, novel therapies that are currently in development58 may provide physicians with more treatment options in the near future.

Here, a substantial impact of CSU on HRQoL, as indicated by MCS, PCS, health utility, and DLQI scores, was reported. In the CSU cohort, HRQoL was notably worse, with a decrement of 10 points for MCS and PCS scores and a decrement of more than 0.15 points in health utility scores when compared to the overall NHWS population. This is consistent with studies from the United States, Europe, and Korea, which reported worse HRQoL among patients with CSU.6, 7, 8, 9, 10,59

In this study, over 74% of the respondents reported experiencing anxiety (GAD-7 ≥5) and depression (PHQ-9 ≥5), which aligns with findings from similar studies globally.60, 61, 62 Research conducted in the five largest European countries and Brazil found that anxiety and depression were twice as common among patients with CSU compared to controls.9,10 A systematic review reported the pooled prevalence of psychosomatic disorders at 46.1%, which was lower compared to our study.62

The mean absenteeism, presenteeism (present but lost productivity), overall work impairment, and activity impairment were more than twice as high among patients with CSU compared to the overall NHWS population, and these findings are consistent with the previous research in the US.6,7,63 The percentage of work and activity impairment in this study was higher than that of studies conducted in Europe.8, 9, 10 Comparing the difference in the burden of CSU, the AWARE study reported significantly higher impairment in the Central/South America region compared to Europe.44 HCRU was also substantial in our study, with more than 55.0% of patients with CSU having reported emergency department visits and hospitalizations, which was higher compared to previous studies in the United States and Europe.4,6,9,10 The greater work, productivity, and mental health impairments, as well as HCRU, in this study may be attributed to the higher percentages of patients with uncontrolled and unpredictable disease, undertreatment, and angioedema. Angioedema has been previously associated with significantly higher impairment in HRQoL, sleep, and daily activities.42,64 Italian patients from the AWARE study reported considerable improvement in HRQoL, DLQI, WPAI, and total activity impairment, with 96.8% being treated with medication during the study.65 The evidence for the increased prevalence of comorbidities among patients with CSU is substantial, with these comorbidities having a negative impact on HRQoL and being associated with higher humanistic and economic burdens.3

The chronic and variable nature of CSU can exacerbate humanistic and economic burdens over time, necessitating a comprehensive assessment. The results of this study would further inform healthcare providers, policymakers, and stakeholders for better resource allocation; however, this study has several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting these results. Firstly, the NHWS is a panel-based internet survey, and there could be bias in the estimates, most likely among segments of the population that do not have access to the internet, which may underestimate the true burden of disease. Similarly, the sociodemographic composition of the overall study population may not be reflective of the general US population. For example, the proportion of individuals with a university degree was higher among study participants than the general US population aged ≥25 years (50.4% vs 35.0%),66 which may be due to the association between educational attainment and the likelihood to participate in health surveys.67,68 Furthermore, humanistic and economic outcomes of patients with CSU were compared to the overall survey population and not to patients without CSU only; thus, the actual burden of CSU may not have been fully realized. Another limitation is the use of patient-reported outcomes with different recall time periods, which may lead to recall bias. The patient-reported nature of the survey also meant that healthcare provider diagnoses of CSU and comorbidities were not verified, and diagnostic criteria not specified. The survey was designed to be patient-friendly, with medical information presented in an easy-to-understand format; thus, more specific medical details were not collected. The information that was collected is limited by the patients’ abilities to provide accurate responses. Additionally, as CIndU is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed as CSU,69 some participants with CIndU may have been included in the CSU population. The high frequency of allergies reported may be reflective of the fact that the diagnostic criteria for allergies, and individual allergy types, were not collected. However, as noted previously, the prevalence of allergies was comparable to the general US population.40 Finally, this is a cross-sectional study, and the nature of these data prevents any causal interpretation of the findings.

Conclusion

This real-world study reported a higher prevalence of diagnosed CSU in the United States than previously published and highlighted the substantially high humanistic and economic burdens experienced by patients with CSU. The research reveals that most individuals with CSU suffer from inadequate disease management and insufficient treatment. This leads to negative impacts on their mental and physical well-being, as well as hindrances in their work and everyday life. Consequently, there is an increased demand for healthcare services, which may have economic implications.

This study draws attention to the importance of improving management of this condition and highlights the unmet needs of this population. Following the established treatment protocols is likely to lead to better health outcomes for patients and a decrease in the humanistic and economic burdens associated with the condition.

Abbreviations

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI, confidence interval; CIndU, chronic inducible urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; EQ-VAS, EuroQol-visual analogue scale; GAD-7; General Anxiety Disorder-7; HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MCS, mental component summary; NA. not available; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey; OTC, over-the-counter; PCS, physical component summary; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SD, standard deviation; SF-36v2, 36-item Short Form Survey version 2; SF-6D, Short-Form 6 Dimension; UCT, urticaria control test; US, United States; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment.

Authors’ contributions

WS, DP, JR, RKK, and MMB contributed to the conception of the study and acquisition of the data. KK, SG, and BLB contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the drafting of the article. All authors provided final approval of the article to be submitted for publication.

Authors’ consent for publication

All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version for submission. All authors had access to the study data.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly available because they were used pursuant to a data use agreement. The data are available through requests made directly to Oracle Life Sciences.

Funding source

This research was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Medical writing and editorial support was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Declaration of competing interest

WS was a consultant for Allakos, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Jasper, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Teva; a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Genentech, GSK, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi; and has conducted research for AbbVie, Allakos, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celldex, Escient, Evommune, Genentech, GSK, Incyte, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Upstream Bio. DP and JR are employees of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA, and may own stock and/or stock options. RKK is an employee of Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, India. KK and SG are employees of Oracle Life Sciences, Austin, TX, USA, who own the NHWS and conducted the data analysis. BLB was an employee of Oracle Life Sciences, who own the NHWS at the time of the analysis. MMB is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland and may own stock and/or stock options.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Mukhtar Ahmad Dar, Novartis Healthcare Pvt Ltd., Hyderabad, India. Editorial support was provided by Harriet Pelling, PhD and Bernadette Tynan, MSc (both of BOLDSCIENCE Ltd., UK). This manuscript was developed in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines. The authors had full control of the content and made the final decision on all aspects of this publication.

Footnotes

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

References

- 1.Zuberbier T., Abdul Latiff A.H., Abuzakouk M., et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022;77:734–766. doi: 10.1111/all.15090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fricke J., Ávila G., Keller T., et al. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy. 2020;75:423–432. doi: 10.1111/all.14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolkhir P., Giménez-Arnau A.M., Kulthanan K., Peter J., Metz M., Maurer M. Urticaria. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8:61. doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zazzali J.L., Broder M.S., Chang E., Chiu M.W., Hogan D.J. Cost, utilization, and patterns of medication use associated with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broder M.S., Raimundo K., Antonova E., Chang E. Resource use and costs in an insured population of patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:313–321. doi: 10.1007/s40257-015-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wertenteil S., Strunk A., Garg A. Prevalence estimates for chronic urticaria in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vietri J., Turner S.J., Tian H., Isherwood G., Balp M.M., Gabriel S. Effect of chronic urticaria on US patients: analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoskin B., Ortiz B., Paknis B., Kavati A. Humanistic burden of refractory and nonrefractory chronic idiopathic urticaria: a real-world study in the United States. Clin Ther. 2019;41:205–220. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurer M., Abuzakouk M., Bérard F., et al. The burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria is substantial: real-world evidence from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy. 2017;72:2005–2016. doi: 10.1111/all.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balp M.M., Lopes da Silva N., Vietri J., Tian H., Ensina L.F. The burden of chronic urticaria from Brazilian patients' perspective. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2017;7:535–545. doi: 10.1007/s13555-017-0191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balp M.M., Vietri J., Tian H., Isherwood G. The impact of chronic urticaria from the patient’s perspective: a survey in five European countries. Patient. 2015;8:551–558. doi: 10.1007/s40271-015-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goren A., Liu X., Gupta S., Simon T.A., Phatak H. Quality of life, activity impairment, and healthcare resource utilization associated with atrial fibrillation in the US National Health and Wellness Survey. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weller K., Groffik A., Church M.K., et al. Development and validation of the urticaria control test: a patient-reported outcome instrument for assessing urticaria control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1076. e1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware J.E., Snow K.K., Kolinski M., Gandeck B. The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre; Boston, MA: 1993. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maruish M.E. Quality Metric Incorporated; 2011. User's Manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandek B., Ware J.E., Aaronson N.K., et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. International quality of life assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brazier J., Roberts J., Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21:271–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brazier J., Usherwood T., Harper R., Thomas K. Deriving a preference-based single index from the UK SF-36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1115–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herdman M., Gudex C., Lloyd A., et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontodimopoulos N., Stamatopoulou E., Gazi S., Moschou D., Krikelis M., Talias M.A. A comparison of EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, and SF-6D utilities of patients with musculoskeletal disorders of different severity: a health-related quality of life approach. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4097. doi: 10.3390/jcm11144097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng Y., Parkin D., Devlin N.J. Assessing the performance of the EQ-VAS in the NHS PROMs programme. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:977–989. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0537-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finlay A.Y., Khan G.K. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hongbo Y., Thomas C.L., Harrison M.A., Salek M.S., Finlay A.Y. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659–664. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finlay A.Y. Current severe psoriasis and the rule of tens. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:861–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang K. Estimating productivity costs in health economic evaluations: a review of instruments and psychometric evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:31–48. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistic. Current population survey, 2018 annual social and economic (ASEC) supplement. 2018. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/techdocs/cpsmar18.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2024.

- 31.Strader C., Goren A., DiBonaventura M. Prevalence of combinations of diabetes complications across NHANES and NHWS. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(Suppl. 3):3–679. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolge S.C., Doan J.F., Kannan H., Baran R.W. Association of insomnia with quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:415–422. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapi F., Cassano N., Pegoraro V., et al. Epidemiology of chronic spontaneous urticaria: results from a nationwide, population-based study in Italy. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:996–1004. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim Y.S., Park S.H., Han K., Bang C.H., Lee J.H., Park Y.M. Prevalence and incidence of chronic spontaneous urticaria in the entire Korean adult population. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:976–977. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J., Mao D., Liu S., et al. Epidemiology of urticaria in China: a population-based study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135:1369–1375. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norris T., Adjaye-Gbewonyo D., Bottoms-McClain L. 2024. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2023 national health interview survey.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease202405.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pate C.A., Zahran H.S. The status of asthma in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2024;21 doi: 10.5888/pcd21.240005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abend A.H., He I., Bahroos N., et al. Estimation of prevalence of autoimmune diseases in the United States using electronic health record data. J Clin Investig. 2025;135 doi: 10.1172/JCI178722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emmerich S.D., Fryar C.D., Stierman B., Ogden C.L. NCHS Data Brief.; 2024. Obesity and severe obesity prevalence in adults: United States, August 2021-August 2023. 508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng A., Boersma P. NCHS Data Brief; 2023. Diagnosed allergic conditions in adults: United States, 2021; pp. 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maurer M., Weller K., Bindslev-Jensen C., et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zazzali J.L., Kaplan A., Maurer M., et al. Angioedema in the omalizumab chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria pivotal studies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:370–377.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sussman G., Abuzakouk M., Bérard F., et al. Angioedema in chronic spontaneous urticaria is underdiagnosed and has a substantial impact: analyses from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy. 2018;73:1724–1734. doi: 10.1111/all.13430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maurer M., Houghton K., Costa C., et al. Differences in chronic spontaneous urticaria between Europe and Central/South America: results of the multi-center real world AWARE study. World Allergy Organ J. 2018;11:32. doi: 10.1186/s40413-018-0216-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maurer M., Raap U., Staubach P., et al. Antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria: 1-year data from the AWARE study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49:655–662. doi: 10.1111/cea.13309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner N., Zink A., Hell K., et al. Patients with chronic urticaria remain largely undertreated: results from the DERMLINE online survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021;11:1027–1039. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00537-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riedl M.A., Patil D., Rodrigues J., et al. Clinical burden, treatment, and disease control in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: real-world evidence. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2025;134 doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2024.12.008. 324–332.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weller K., Winders T., McCarthy J., et al. Urticaria voices: real-world experience of patients living with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2025;15:747–761. doi: 10.1007/s13555-025-01348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldstein S., Eftekhari S., Mitchell L., et al. Perspectives on living with chronic spontaneous urticaria: from onset through diagnosis and disease management in the US. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1091–1098. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maurer M., Albuquerque M., Boursiquot J.N., et al. A patient charter for chronic urticaria. Adv Ther. 2024;41:14–33. doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02724-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weller K., Maurer M., Bauer A., et al. Epidemiology, comorbidities, and healthcare utilization of patients with chronic urticaria in Germany. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:91–99. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soong W., Patil D., Pivneva I., et al. Disease burden and predictors associated with non-response to antihistamine-based therapy in chronic spontaneous urticaria. World Allergy Organ J. 2023;16 doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2023.100843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Armstrong A.W., Soong W., Bernstein J.A. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: how to measure it and the need to define treatment success. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023;13:1629–1646. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolf J.A., Moreau J.F., Patton T.J., Winger D.G., Ferris L.K. Prevalence and impact of health-related internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients. Cutis. 2015;95:323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Finnegan P., Murphy M., O'Connor C. Reinventing the wheal: a review of online misinformation and conspiracy theories in urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2023;53:118–120. doi: 10.1111/cea.14246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sánchez J., Sánchez A., Cardona R. Dietary habits in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: evaluation of food as trigger of symptoms exacerbation. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/6703052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mosnaim G., Patil D., Kuruvilla M., Hetherington J., Keal A., Mehlis S. Patient and physician perspectives on disease burden in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a real-world US survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2025;134:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2024.11.028. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kolkhir P., Fok J.S., Kocatürk E., et al. Update on the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Drugs. 2025;85:475–486. doi: 10.1007/s40265-025-02170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ye Y.M., Koh Y.I., Choi J.H., et al. The burden of symptomatic patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a real-world study in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2022;37:1050–1060. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2022.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozkan M., Oflaz S.B., Kocaman N., et al. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:29–33. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Staubach P., Dechene M., Metz M., et al. High prevalence of mental disorders and emotional distress in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:557–561. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ben-Shoshan M., Blinderman I., Raz A. Psychosocial factors and chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review. Allergy. 2013;68:131–141. doi: 10.1111/all.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jain S., Gupta S., Li V.W., Suthoff E., Arnaud A. Humanistic and economic burden associated with depression in the United States: a cross-sectional survey analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:542. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04165-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodríguez-Garijo N., Sabaté-Brescó M., Azofra J., et al. Angioedema severity and impact on quality of life: chronic histaminergic angioedema versus chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.07.011. 3039-3043.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rossi O., Piccirillo A., Iemoli E., et al. Socio-economic burden and resource utilisation in Italian patients with chronic urticaria: 2-year data from the AWARE study. World Allergy Organ J. 2020;13 doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.United States Census Bureau . Educational Attainment. 2023. ACS 5-Year estimates subject tables.https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2023.S1501 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee C.M.Y., Thomas E., Norman R., et al. Educational attainment and willingness to use technology for health and to share health information – the reimagining healthcare survey. Int J Med Inform. 2022;164 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reinikainen J., Tolonen H., Borodulin K., et al. Participation rates by educational levels have diverged during 25 years in Finnish health examination surveys. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28:237–243. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kovalkova E., Fomina D., Borzova E., et al. Comorbid inducible urticaria is linked to non-autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria: CURE insights. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.11.029. 482–490.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly available because they were used pursuant to a data use agreement. The data are available through requests made directly to Oracle Life Sciences.