Central Illustration

Key Words: cardioprotective, exogenous, ketone bodies, pleiotropic, vascular

Highlights

-

•

Evidence for the potential of KBs as a therapeutic approach in cardiovascular disease is accumulating rapidly.

-

•

In addition to serving as alternative fuel sources, KBs exert an array of pleiotropic activities via multiple mechanisms.

-

•

The vasculature is a key target of KBs and significantly contributes to the cardioprotective effects of exogenous KBs.

-

•

Delineation of the primary mechanism(s) for the beneficial cardiac effects of exogenous KBs will accelerate their clinical translation.

Summary

Evidence for the potential of ketone bodies (KBs) in the treatment of cardiovascular disease is growing rapidly. In addition to serving as sources of myocardial fuel, KBs exert an array of pleiotropic activities via multiple mechanisms. The vasculature is emerging as a key target of KBs. Recent small clinical studies have shown that the administration of exogenous KBs to patients with heart failure is associated with a marked reduction in systemic vascular resistance and improvement in myocardial function. Exogenous KBs have also been shown to increase coronary blood flow; decrease pulmonary vascular resistance; promote endothelial function and angiogenesis; increase skeletal muscle oxygenation and capillarization; and inhibit atherosclerosis, vascular calcification, and senescence. These vasculo-protective properties likely contribute to the beneficial effects of exogenous KBs observed in heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, and myocardial ischemia/infarction, and suggest potential wide applications in several other cardiovascular diseases and related conditions. In this review, we will discuss the salutary vascular effects of KBs and their cardioprotective roles.

Ketone bodies (KBs), comprising acetoacetate (AcAc), D-β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB), and acetone, are synthesized in the liver from circulating fatty acids during periods of metabolic stress, such as prolonged fasting, consumption of a high-fat low-carbohydrate diet (also known as a ketogenic diet), and prolonged exercise.1,2 Circulating KBs are taken up by metabolically active tissues such as the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle to serve as a fuel source for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production (Figure 1). Over the past several years, there has been substantial interest in exploring the therapeutic potential of KBs in cardiovascular disease (CVD) by capitalizing on their role as alternative fuel sources. Support for this theory has also accumulated from the observed cardioprotective effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which are known to cause ketosis.3 More recently, there is a growing body of evidence showing that KBs participate in a wide array of cellular functions beyond their role in energy metabolism, including in signaling and epigenetic modification, inhibition of inflammation and oxidative stress, regulation of vascular and endothelial function, and regulation of systemic metabolic homeostasis.1,2,4

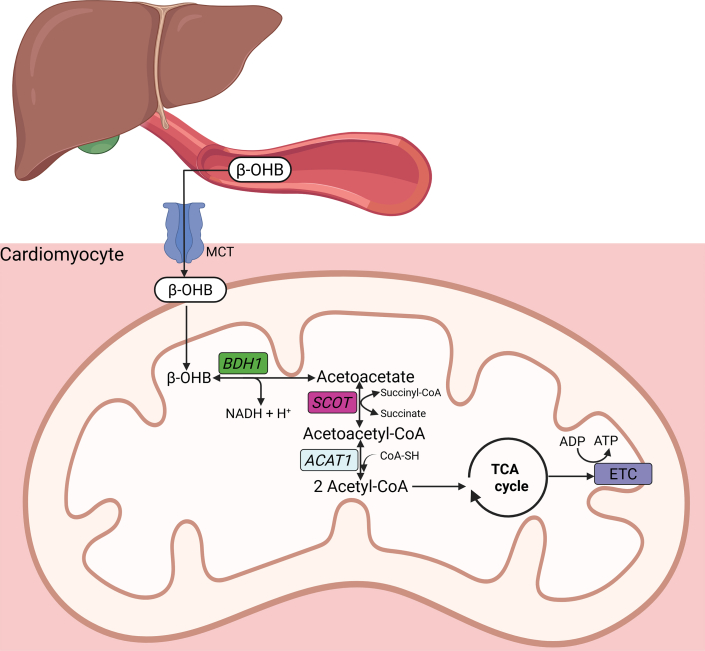

Figure 1.

Ketone Body Oxidation and Energy Generation

Following synthesis in the liver, ketone bodies (KBs) are released into the circulation and transported into cells through monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs). KBs enter the mitochondria and undergo oxidative metabolism via beta-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1 (BDH1) that catalyzes the conversion of beta-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) to acetoacetate (AcAc). AcAc is then metabolized into acetoacetyl-CoA by succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid-CoA transferase (SCOT). Acetoacetyl-CoA is finally converted to acetyl-CoA for entry into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. ACTA1 = acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1; CoA-SH = coenzyme A; ETC = electron transport chain; NADH = nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide.

Ketosis, defined as an increased level of circulating KBs (∼1 mmol/L or higher), is often caused by increased endogenous production. However, ketosis can also be achieved through the administration of exogenous KBs in the form of ketone salts, ketone esters (KEs) such as (R)-3-hydroxybutyl-(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate, or KB precursors including 1,3-butanediol.5, 6, 7 Several recent reviews have discussed the therapeutic potential of exogenous KBs, the ketogenic diet, and SGLT2 inhibitors in CVD, with an emphasis on their beneficial effects on cardiac energy metabolism.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Newer evidence shows that the vasculature is also a key target of the pleiotropic effects of KBs and may significantly contribute to the cardioprotective effects of exogenously administered KBs.15, 16, 17 Considering the critical role that impaired vascular function plays in the pathogenesis and progression of CVD, and the accumulating evidence that KBs have numerous beneficial effects on the vasculature, the cardiovascular (CV) protective effect of KBs operating via the vasculature and endothelium are somewhat underappreciated and may serve as an important new therapeutic avenue of investigation. In this review, we will discuss the substantial contribution of the vascular effects of KBs to their cardioprotective roles, with a specific focus on exogenous KBs.

Cardioprotective Effects of Exogenous KBs

Evidence from both animal and human studies has shown that inducing ketosis via acute or chronic administration of exogenous KBs is beneficial in CVD and related conditions, including ischemic heart disease, heart failure (HF), pulmonary hypertension (PH), atherosclerosis, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and exercise intolerance (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Animal Studies on the Effects of Exogenous Ketone Bodies in CVD

| Disease | Experimental Model | Exogenous Ketone Body | Outcomes | First Author, Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial ischemia/infarction | IRI in fasted rats with 30 min of ischemia and 2 h of reperfusion | IV β-OHB infusion for 60 min before coronary artery ligation | ↓ infarct size; ↓ apoptosis ↑ myocardial ATP |

Zou et al,18 2002 |

| Porcine model of IRI with 45 min of ischemia and 4 h of reperfusion | IV β-OHB infusion from 30 min before coronary artery ligation until completion of the procedure | ↑ LV systolic function; ↓ infarct size ↓ apoptosis; ↓ oxidative stress ↓ microvascular obstruction |

Santos-Gallego et al,19 2023 | |

| IRI in mice with 30 min of ischemia and 24 h of reperfusion | Subcutaneous β-OHB infusion for 24 h during reperfusion | ↑ LV systolic function; ↓ infarct size ↓ apoptosis; ↑ autophagy ↓ ER stress ↓ mitochondrial oxidative stress and swelling; ↑ myocardial ATP |

Yu et al,20 2018 | |

| IRI in isolated perfused mouse hearts | 3 mmol/L β-OHB was added to the perfusion solution at the start of reperfusion | ↑ LV systolic function ↓ NLRP3 inflammasome |

Byrne et al,21 2020 | |

| IRI in mice with 45 min of ischemia and 24 h of reperfusion | Β-OHB administered IP (10 mmol/kg) at the start of reperfusion | ↓ infarct size; ↑ LV systolic function ↑ autophagy in the border zone ↑ mitochondrial DNA levels |

Chu et al,22 2023 | |

| HFrEF | Tachypacing-induced HF (dogs) | IV β-OHB infusion for 2 wks | ↑ CO; ↑ LVEF; ↓ LVEDP ↓ SVR; ↓ Ea; ↓ LVIDd; ↓ LV mass |

Horton et al,5 2019 |

| TAC-induced HF (mice) | 20% KE in drinking water for 2 wks | ↑ LVEF; ↓ LV hypertrophy ↓ Periostin (fibroblast activation) |

Takahara et al,25 2021 | |

| Post-MI HF (mice) | Subcutaneous infusion of β-OHB started after coronary artery ligation (for 4 wks) | ↑ LVEF; ↓ infarct size; ↓ LVIDd ↑ microvascular density; ↑ VEGF |

Wang et al,26 2025 | |

| TAC/MI-induced HF (mice) and post-MI HF (rats) | a diet containing a KE (mice) or β-OHB-butanediol monoester (rats) | ↑ LVEF; ↓ LV hypertrophy; ↓ ANP ↑ myocardial ATP |

Yurista et al,24 2021 | |

| HFpEF | 3-hit model of HFpEF (age, high-fat diet, and the mineralocorticoid DOCP) | a KE gavage (1mg/kg/d) for 30 d | ↑ LV diastolic function ↑ exercise tolerance ↓ lung edema; ↓ BNP ↓ BP ↓ mitochondrial hyperacetylation ↓ NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ fibrosis |

Deng et al,28 2021 |

| 2-hit model of HFpEF (high-fat diet, and L-NAME) | Weekly intraperitoneal injection of β-OHB | ↑ LV diastolic function; ↓ lung edema ↓ BP; ↓ LV hypertrophy; ↓ fibrosis ↓ inflammation; ↑ Tregs |

Liao et al,29 2021 | |

| Diabetic cardiomyopathy | Type 2 diabetic (db/db) mice | A diet containing a KE | ↑ LV systolic and diastolic function ↓ Oxidative stress; ↑ ketolytic enzymes ↑ Mitochondrial function; ↑ mitochondrial oxygen consumption |

Thai et al,27 2021 |

| Hypertension | Dahl S (salt-sensitive) rats fed a high-salt diet | 1,3-butanediol (20%) in drinking water for 8 wks | ↓ BP (both systolic and diastolic) ↓ Renal NLRP3-inflammasome ↓ Renal injury (fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis, and protein casts) |

Chakraborty et al,30 2018 |

| Atherosclerosis | A mouse model of atherosclerosis (high-fat diet fed apoE−/− mice) | Intragastric administration of β-OHB for 9 wks | ↓ atherosclerotic plaque burden in the aorta ↓ NLPR3 inflammasome ↑ cholesterol efflux via GPR109a on macrophages; ↓ M1 macrophages |

Zhang et al,31 2021 |

| Vascular calcification | CKD rats and VitD3-overloaded mice | Supplementation of 1,3-butanediol | ↓ Calcification of aortic rings and VSMCs ↓ HDAC9-dependent NF-κB signaling |

Lan et al,33 2022 |

β-OHB = beta-hydroxybutyrate; ANP = atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; BP = blood pressure; CO = cardiac output; DOCP = deoxycorticosterone pivalate; Ea = arterial elastance; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; ER = endoplasmic reticulum; HDAC9 = histone deacetylase 9; HFrEF = heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; IRI = ischemia-reperfusion injury; IV = intravenous; L-NAME = N(ω)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; LVEDP = left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd = left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole; MI = myocardial infarction; NLRP3 = Nod-like receptor protein 3; SVR = systemic vascular resistance; TAC = transverse aortic constriction; Tregs = regulatory T cells; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; VSMCs = vascular smooth muscle cells.

Table 2.

Clinical Trials on the Beneficial Effect of Exogenous Ketone Bodies in CVD and CVD-Related Conditions

| Disease/Condition | Subjects | Exogenous KBs | βOHB Conc, mmol/L |

Follow-Up | Outcomes | First Author, Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | 16 patients with chronic HFrEF | IV infusion of β-OHB | 3.3 | 3 h | ↑ CO by 2 L/min; ↑ LVEF by 8% ↓ SVR by 5.6 WU ↓ PCWP by 1.2 mm Hg ↑ MVO2; ↔ MEE; ↑ CBF |

Nielsen et al.,39 2019 |

| 12 patients with cardiogenic shock | A single enteral dose of KE (0.5 g/kg) | 2.9 | 3 h | ↑ CO by 0.5 L/min; ↑ LVEF by 4%; ↑ CPO ↓ SVR by 3.0 WU ↓ PCWP by 3 mm Hg ↑ Forearm oxygenation ↓ Glucose |

Berg-Hansen et al.,41 2023 | |

| 24 patients with HFrEF | An oral KE drink (25 g) 4 times daily | 2.4 | 2 wks | ↑ CO by 0.4 L/min; ↑ LVEF by 3% ↓ SVR by 1.5 WU ↓ PCWP by 2 (rest) and by 3 mm Hg (peak exercise); ↔ CO (at peak exercise) |

Berg-Hansen et al,42 2024 | |

| 12 patients with HFrEF | An oral dose of 1,3-butanediol (0.5 g/Kg) | 1.5 | 6 h | ↑ CO by 0.9 L/min; ↑ LVEF by 3% ↓ SVR by 4.4 WU ↓ NEFA; ↓ Glucose |

Guldbrandsen et al,40 2025 | |

| HF in type 2 DM | 24 patients with HFpEF and type 2 DM | An oral KE drink (25 g) 4 times daily | 1.01 | 2 wks | ↑ CO by 0.2 L/min and ↔LVEF ↑ LV compliance ↓ SVR by 0.8 WU ↓ PCWP by 1 (rest) and by 5 mm Hg (peak exercise) |

Gopalasingam et al,43 2024 |

| 12 patients with type 2 DM and HF, EF < 50% | IV β-OHB infusion | 3.3 | 6 h | ↑ CO by 1.2 L/min; ↑ LVEF by 6.4% ↑ CBF (in those with higher baseline EF) ↔ MGU |

Solis-Herrera et al,71 2025 | |

| PH | 20 patients with either PAH (n = 10) or CTEPH (n = 10) | IV β-OHB infusion | 3.4 | 2 h | ↑ CO by 1.2 L/min; ↑ S’ by 1.4 cm/s ↔ LVEF ↓ PVR by 1.3 WU; ↓ SVR by 5.2 WU ↔ PCWP ↑ SVO2 by 5.2% |

Nielsen et al,44 2023 |

| Insulin resistance | 15 obese individuals | An oral KE drink before OGTT | 3.4 | 2.5 h | ↓ Glycemic response ↓ NEFA |

Myette-Côté et al,45 2018 |

| 14 obese individuals | An oral KE (12 g), premeal | 1.8 | 14 d | ↓ Glucose (postprandial and 24-h average) ↑ FMD (brachial artery) ↓ NLRP3 activation |

Walsh et al,46 2021 | |

| 8 healthy subjects | IV β-OHB and GH infusion | 3.3 | 6 h | ↓ Lipolysis; ↓ NEFA ↑ Insulin sensitivity |

Høgild et al,47 2024 | |

| Exercise capacity/tolerance | 39 high-performance athletes | An oral KE (573 mg/kg) taken at rest and during exercise | 3.0 | 45 min | ↑ Endurance exercise performance ↑ Oxidative metabolism (skeletal muscle) ↓ Glycolysis (skeletal muscle) |

Cox et al,48 2016 |

| 9 healthy male participants | An oral KE (25 g) after endurance training sessions | 2.6 | 3 wks | ↑ Endurance exercise performance ↓ Physiological indicators of overtraining |

Poffé et al,50 2019 | |

| 14 highly trained male cyclists | An oral KE (75 g) during cycling under reduced FiO2 | 3.0 | 3 h | ↑ Skeletal muscle oxygenation ↑ Blood oxygenation ↔ Exercise performance |

Poffé et al,93 2021 | |

| 10 healthy male volunteers | An oral KE (25 g) after training sessions | — | 3 wks | ↑ Skeletal muscle capillarization ↑ eNOS and VEGF ↑ Serum erythropoietin |

Poffé et al,94 2023 | |

| 13 adults with type 2 diabetes | An oral KE (0.115 g/kg) 1 h before cycling | 2.2 | 2 h | ↑ CO (rest and exercise) ↓ SVR (rest and exercise) ↑ Skeletal muscle oxygenation (exercise) ↔ VO2; ↔FMD (brachial artery) |

Perissiou et al,95 2025 | |

| 6 athletes | High vs low dose (752 vs 252 mg/kg) oral KE | 4.4 vs 2.0 | 1 h | ↑ Exercise efficiency in both low and high doses ↔KB oxidation low vs high dose ketosis ↔KB oxidation low vs high-intensity exercise |

Dearlove et al., 202149 | |

| 20 symptomatic HFpEF patients | An oral KE (500 mg/kg 1 h before incremental exercise and an additional 250 mg/kg 30 min before constant-intensity exercise | 3.1 and 3.8 mmol/L | 1-2 h | ↔ VO2 ↑ CO, ↑ LVEF, and ↓ SVR (at rest) ↔CO, ↔LVEF, and ↔SVR (peak exercise) ↓ LV filling pressures (rest and exercise) ↔ Endurance (constant-intensity exercise) ↓ Systemic carbohydrate utilization ↓ NEFA, ↓ glucose |

Selvaraj et al,140 2025 |

CBF = coronary blood flow; CPO = cardiac power output; CS = cardiogenic shock; CTEPH = chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus; EE = myocardial energy efficiency; eNOS = endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GH = growth hormone; KE = ketone ester; MGU = myocardial glucose uptake; MVO2 = myocardial oxygen consumption (non-esterified fatty acids); OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PH = pulmonary hypertension; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; S′ = right ventricular annular systolic velocity; SVO2 = mixed oxygen saturation; abbreviations as in Table 1.

Preclinical evidence

In several animal models of ischemia-reperfusion injury, β-OHB infusion or oral administration of a KE before coronary artery ligation18,19 or during reperfusion20, 21, 22 reduced infarct size, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, peri-infarct inflammation, and improved contractile performance (Table 1). Similarly, substantial experimental evidence supports the salutary effects of exogenous KBs in pathological remodeling and HF.23 Inducing ketosis via chronic β-OHB infusion or oral supplementation with KEs ameliorated pathologic cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in several animal models of HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).5,24, 25, 26 Similarly, increasing circulating β-OHB levels via administration of exogenous KBs resulted in improvement of left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic function in diabetic mice,27 and mitigated diastolic dysfunction and pathologic remodeling in 3-hit28 and 2-hit29 mouse models of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). In addition to myocardial infarction (MI) and HF, experimental studies also show the protective effects of exogenous KBs in hypertension,30 atherosclerosis,31,32 vascular calcification,33,34 dyslipidemia,35,36 insulin resistance,37 and exercise intolerance35,38 (Table 1).

Clinical evidence

Studies in humans also support the salutary CV effects of increasing circulating concentrations of KBs in CVD (Table 2). In patients with HFrEF, acute β-OHB infusion39 or an oral dose of 1,3-butanediol40 increased CO (cardiac output) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and reduced systemic vascular resistance (SVR). In patients with cardiogenic shock caused by acute MI or decompensated HF, a single dose enteral KE administration on top of an existing medical regimen increased CO, decreased filling pressures and SVR, and improved peripheral perfusion.41 In addition to acute treatment, chronic supplementation with KBs also demonstrated significant cardiac benefits. Two studies, one involving patients with HFrEF on optimal medical therapy42 and the other involving patients with HFpEF and type 2 diabetes,43 reported that treatment with an oral KE for 14 days increased CO and reduced SVR and LV filling pressures, both at rest and during exercise. In patients with pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), infusion of β-OHB decreased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), increased CO, and improved right ventricular function.44 Exogenous KBs also have favorable effects on systemic metabolic homeostasis and exercise performance and have been shown to improve postprandial hyperglycemia, reduce circulating non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels by inhibiting lipolysis in adipose tissue, enhance skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity, increase skeletal muscle oxygenation and capillarization, and improve exercise performance45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 (Table 2).

Taken together, there is substantial preclinical and clinical evidence supporting the therapeutic potential of exogenous KBs in CVD. Below, we will discuss the effects of KBs on vascular physiology and CVD and their contribution to CV protection.

Vascular Effects of Ketone Bodies

Ketone bodies exert multiple effects on several critical aspects of vascular physiology and pathophysiology, including SVR and PVR, blood flow in specific vascular beds (such as the coronary, renal, and cerebral arteries), endothelial and microvascular function, vascular senescence, atherosclerosis, and vascular calcification (Figure 2, Central Illustration). The vascular effects of KBs along with proposed mechanisms are discussed later.

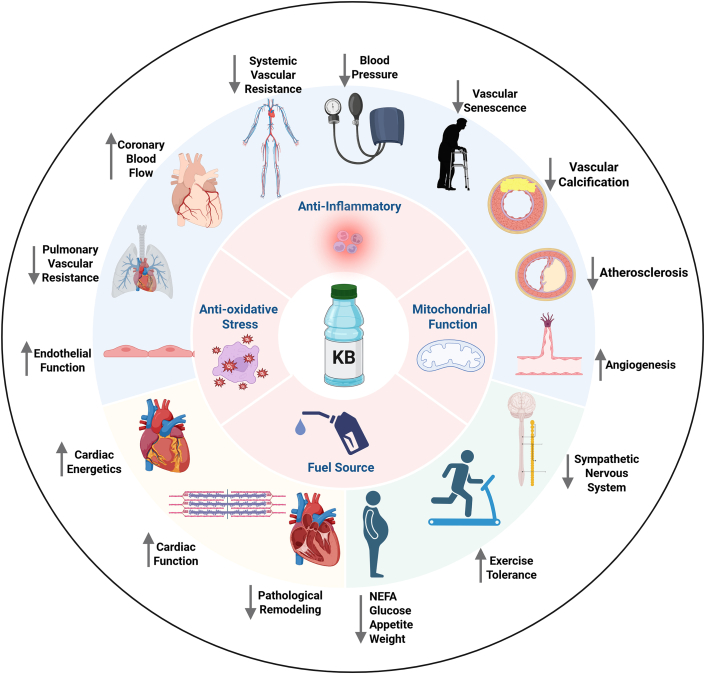

Figure 2.

The Beneficial Vascular, Cardiac, and Systemic Effects of Exogenous KBs

Vasculoprotective properties of exogenous ketone bodies include vasodilation of systemic, pulmonary, and coronary circulation, enhancing endothelial function; decreasing blood pressure; promoting angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis; and preventing vascular senescence, calcification, and atherosclerosis. Cardiac effects of KBs include improving cardiac energetics, ameliorating pathological remodeling, and enhancing cardiac function. Systemic metabolic effects of KBs include decreasing glucose and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels, suppressing appetite, and weight loss. KBs may also improve exercise tolerance and inhibit the sympathetic nervous system. Cellular mechanisms for the above activities include roles as a fuel source, anti-inflammatory, antioxidative stress, and promoter of mitochondrial function.

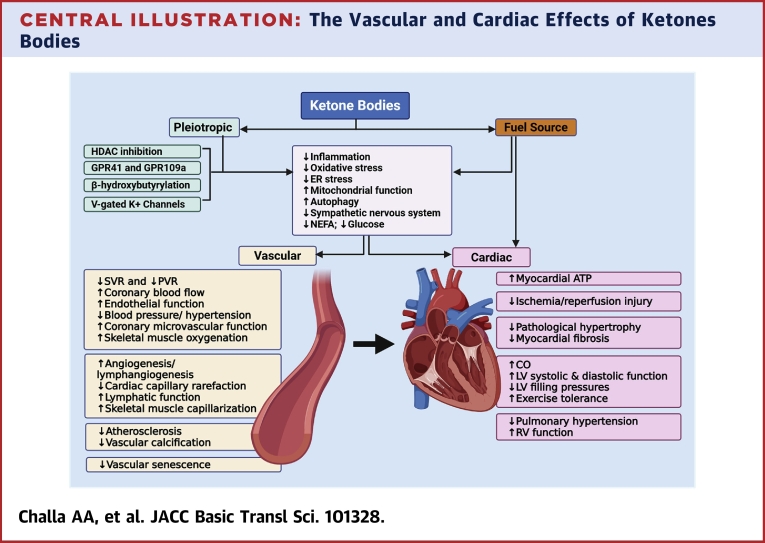

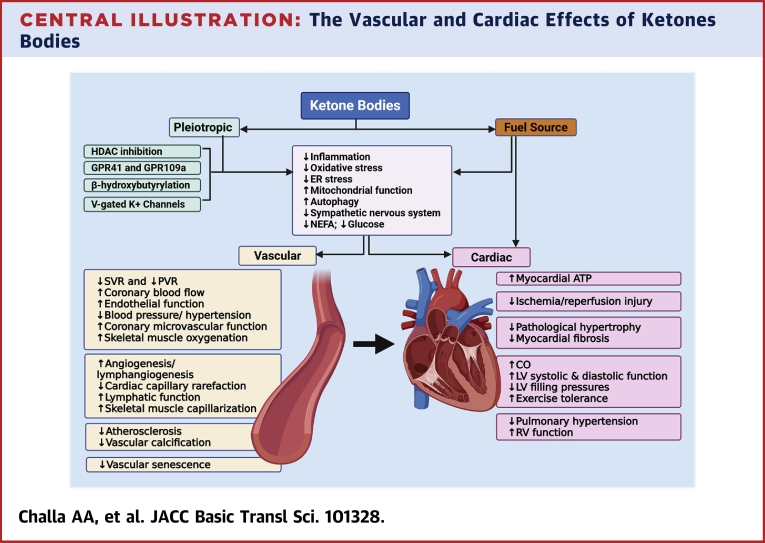

Central Illustration.

The Vascular and Cardiac Effects of Ketones Bodies

Ketone bodies (KBs) serve as an alternate fuel source for the myocardium but also possess pleiotropic activities including anti-inflammatory, antioxidative stress, and enhancing mitochondrial function among others. KBs accomplish these functions via several mechanisms, including inhibiting histone deacetylase (HDAC), acting via their G-protein coupled receptors (GPRs), β-hydroxybutyrylation of cellular proteins and histones, and activation of voltage-gated potassium channels (V-gated K+ channels). The vasculature is the main target of the pleiotropic activities of KBs. The effects of KBs on the vasculature include systemic, pulmonary, and coronary vasodilation, enhancing endothelial function, and promoting angiogenesis. The vascular effects of KBs contribute to the beneficial effects of KBs in ischemia-reperfusion injury, pathological cardiac remodeling, heart failure, and pulmonary hypertension.

Effects on vascular physiology and pathophysiology

Systemic vascular resistance

SVR is primarily determined by the diameter of resistance blood vessels throughout the body. Inappropriately elevated SVR as a result of peripheral vasoconstriction leads to diminished CO caused by increased afterload on the LV.53 Elevated SVR is particularly relevant to HF caused by diminished cardiac reserve and impaired ability to activate compensatory mechanisms. Indeed, afterload reduction is a key aspect of managing HF, both in acute and chronic settings.53 In multiple preclinical and clinical studies, exogenous KBs have consistently been shown to reduce SVR. In healthy rats, acute β-OHB infusion significantly increased CO and markedly reduced SVR.54 Importantly, the reduction in SVR was not accompanied by a decrease in blood pressure or an increase in heart rate, thereby avoiding hypotension and tachycardia as potential adverse effects.54 In this study, the increase in CO is reported to result from a combination of increased myocardial contractility and reduced SVR.54 To support the role of increased myocardial contractility, the authors used isolated perfused rat hearts where peripheral vascular resistance is nonexistent and showed that the addition of 3 to 10 mmol/L β-OHB increased LV contractile performance as measured by LV developed pressure.54 In a canine tachypacing model of HF, chronic infusion of ß-OHB significantly reduced SVR and improved cardiac function, suggesting the effect on SVR is also observed in disease states.5 Evidence from clinical studies also aligns with findings from experimental studies. In healthy adults, acute β-OHB infusion39 or single-dose ingestion of a KE55 increased CO and LV systolic function and markedly reduced SVR. A significant increase in CO (by 2 L/min) along with a marked decrease in SVR (by 5.6 WU) was reported in HFrEF patients who received acute β-OHB infusion for 3 hours, raising the circulating serum level to 3.3 mmol/L.39 Similarly, treatment of patients with HFrEF with a single oral dose of 1,3-butanediol elevated the circulating β-OHB level to 1.5 mmol/L, increased CO by 0.9 L/min, and reduced SVR by 4.4 WU.40 A reduction in SVR along with improved CO and LV filling pressures was also observed in patients with cardiogenic shock who received a single enteral dose of a KE.41 In these clinical studies, because invasive pressure-volume measurements were not conducted, the determination of whether CO increased caused by the effect on the myocardium, peripheral vascular resistance, or a combination was not possible.

β-OHB exists as 2 enantiomers, D-β-OHB and L-β-OHB. The D-β-OHB is the physiologically active and the most abundantly synthesized enantiomer. The L-β-OHB only constitutes ∼4% of the total circulating β-OHB.56,57 Although D-β-OHB is readily oxidized in several metabolically active extrahepatic tissues, L-β-OHB cannot be oxidized in these tissues as it is not a substrate for the activity of β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1 (BDH1), one of the rate-limiting enzymes for the oxidative metabolism of KBs.1,58, 59, 60, 61, 62 In a recent study using pigs and invasive hemodynamic monitoring, the hemodynamic effects of acute infusion of the 2 enantiomers of β-OHB (D-, L-, or D/L-β-OHB) were compared. Infusion of both enantiomers markedly reduced SVR, and the circulating β-OHB levels correlated with CO for both enantiomers.63 The authors demonstrated that the increase in CO was caused by a reduction in afterload, as β-OHB infusion did not affect contractility, preload, or mitochondrial respiratory capacity.63 Importantly, the L-β-OHB, despite showing much slower myocardial uptake kinetics, exerted a stronger hemodynamic response than D-β-OHB, likely caused by higher circulating levels. The findings from this study showed that the vasodilatory effect of β-OHB plays a predominant role in the increase in CO and the improvement in cardiac function associated with acute β-OHB administration. In addition, given the metabolic and pharmacokinetic differences between D- and L-β-OHB, the previously mentioned study suggests that the enantiomer composition of exogenous KBs should be carefully considered for therapeutic applications. Due to slower metabolism, L-β-OHB has a longer elimination half-life, allowing it to achieve higher and more sustained circulating levels than D-β-OHB.63,64 However, if the desired effect is mediated by the role of KBs as alternate fuels, the use of D-β-OHB or a racemic mixture may be necessary.

Chronic administration of exogenous KBs has also been shown to decrease SVR and increase CO in patients with HFrEF as well as in diabetic patients with HFpEF.42,43 Moreover, consistent with the effect of exogenous KBs on systemic vasodilation, β-OHB supplementation has been shown to increase coronary,65 renal,66 and cerebral67 blood flow.

Taken together, there is robust evidence supporting the effect of exogenous KBs on SVR in both physiological and disease states. The reduction in SVR afforded by exogenous KBs plays a primary role in the increase in CO observed with acute administrations and likely contributes to the favorable hemodynamics and improved cardiac function observed with chronic therapy. Further investigations are needed to settle the contributions of the vascular effects to the favorable hemodynamic effects of exogenous KBs.

Coronary blood flow

As part of the systemic circulation, it seems reasonable to speculate that coronary vascular resistance, and thus coronary blood flow (CBF), could be affected by exogenous KBs. However, the relationship between SVR and CBF is not straightforward for several reasons. First, the coronary circulation has a remarkable ability to autoregulate blood flow, maintaining a relatively constant blood flow over a wide range of perfusion pressures. This is because of its tight regulation through multiple mechanisms, including local metabolic, myogenic, endothelial, neural, and hormonal influences.68 As such, coronary vascular resistance operates relatively independently of SVR. Second, the heart, at baseline, extracts a significantly higher percentage of oxygen from the blood compared with other organs.68 Thus, increased demand during stress requires a significant increase in CBF, likely more than what can be achieved by a modest change in SVR. Third, CBF is influenced by compressive forces generated by myocardial contraction during systole.68 As a result, blood flow is maximal during diastole rather than during systole. Thus, increased diastolic filling pressure could significantly limit CBF even in the face of systemic vasodilation. Last, it is challenging to distinguish between increased CBF resulting from augmented CO because of reduced SVR and increased blood flow caused by direct coronary vasodilation. Therefore, although exogenous KBs cause systemic vasodilation as detailed in the previous section, whether they increase CBF is an important question to answer with crucial clinical implications.

Evidence from preclinical studies suggests that β-OHB can increase CBF. In isolated perfused rat hearts, 10 mmol/L β-OHB increased coronary perfusion by ∼20%.54 Similarly, β-OHB caused concentration-dependent vasorelaxation of coronary septal arteries isolated from rat hearts with an EC50 value of 12.4 mmol/L,54 suggesting that significant direct effects of KBs on the coronary vasculature in vivo require KB concentrations higher than typically achieved with exogenous KB administration. Consistent with this notion, β-OHB at concentrations up to 5 mmol/L did not promote direct vasodilation of murine coronary arteries, and deletion of cardiomyocyte BDH1 abolished the ability of β-OHB to augment CBF, indicating a mechanism of KB-induced coronary hyperemia that is dependent on cardiomyocyte metabolism.69 Nevertheless, in isolated preconstricted pig swine coronary arteries, at a concentration of 3 mmol/L, both the D- and L-enantiomers of β-OHB induced vasorelaxation.63 Only a few clinical studies have explored the effect of KBs on myocardial perfusion. In a study involving 8 healthy volunteers, β-OHB infusion for 6 hours achieved circulating levels of 3.8 mmol/L and increased CBF by 75%.65 In healthy adults who consumed a ketone diester drink, circulating β-OHB level rose to 2.1 mmol/L within 2 hours, and CO and CBF increased 31% and 29% from baseline, respectively.70 In patients with HFrEF and in healthy age-matched controls who received β-OHB infusion for 3 hours, the circulating β-OHB level rose to 3.4 mmol/L, accompanied by increased CBF.39 In a recent clinical trial involving 12 diabetic patients with HF and EF <50%, β-OHB infusion increased CO and LVEF, but there was no difference in CBF.71 Subgroup analysis, however, revealed increased CBF in those with higher EFs, suggesting distinct effects depending on the etiology of HF.

Although the potential of KBs to enhance myocardial perfusion in physiology and CVD is a promising therapeutic area, the mechanisms by which they promote vasodilatory responses require further investigation.

Pulmonary vascular resistance

PAH is one of the most challenging CVDs to manage caused by a lack of effective medical therapies. And CTEPH is an increasingly recognized cause of PH.72 Although the primary treatment for CTEPH is surgical pulmonary endarterectomy, medical therapies can be used in patients who are deemed inoperable.73 However, patients with PAH and CTEPH have increased PVR even with existing medical therapies.74 Recently, the vasodilatory activities of exogenous KBs have been found to extend to the pulmonary circulation as well. In patients with PAH or CTEPH, infusion of β-OHB decreased PVR, increased CO, and improved right ventricular function.44 In isolated pulmonary arteries from rats, exposure to β-OHB decreased arterial tension,44 suggesting the vasodilatory effect is responsible for the decreased PVR. Interestingly, decreased PVR was also noted in patients with HFrEF who received β-OHB infusion,39 suggesting potential applications of KBs for the treatment of PH of various etiologies, and extending the list of beneficial effects of KBs in CVDs.

Endothelial dysfunction

Under physiological conditions, the endothelium controls vascular homeostasis by regulating vascular tone and blood flow, modulating vascular permeability, and inhibiting vascular inflammation and thrombosis.75 Endothelial dysfunction, defined as a failure of the endothelium to perform any of these crucial functions, is caused by injury from one or more of the multiple CV risk factors, including dyslipidemia, diabetes, obesity, cigarette smoking, and unhealthy diet, and is a key inciting pathology for the development of CVD.76,77

Exogenous KBs have been shown to prevent endothelial dysfunction. In a salt-sensitive model of hypertension using Dahl S rats, 1,3-butanediol (20%) in drinking water prevented high-salt diet-induced endothelial dysfunction and hypertension.30,78 Interestingly, circulating β-OHB levels were low in the hypertensive rats fed a high-salt diet, suggesting a correlation between decreased β-OHB and endothelial dysfunction. Similarly, β-OHB infusion blunted endothelial damage and disease severity in a mouse model of stroke by preserving the integrity of the blood-brain barrier.79 Evidence from clinical studies also supports the effect of exogenous KBs on endothelial function. In obese adults, supplementation with a KE for 2 weeks improved glucose tolerance as well as endothelial function as measured by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation.46

The previously mentioned studies show that KBs are not only vasodilators but also have the potential to attenuate endothelial dysfunction.

Microvascular dysfunction

Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) refers to a set of functional and structural abnormalities, including impaired endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation, enhanced vasoconstrictor reactivity, arteriolar remodeling, luminal narrowing, and microvascular rarefaction.80 CMD is highly prevalent in patients with CVD, particularly in patients with cardiometabolic diseases and HFpEF, and its presence is associated with worse clinical outcomes.75,77,81, 82, 83 Exogenous KBs have been shown to be beneficial in CMD. In diabetic rats, β-OHB supplementation for 10 weeks attenuated coronary perimicrovascular fibrosis and prevented coronary microvascular hyperpermeability.84,85 Coronary microvascular rarefaction is a feature of CMD and is observed in several CVDs, including HFpEF and HFrEF, and in the pathological remodeling secondary to hypertension or MI.75,77 Emerging evidence suggests that KBs promote endothelial proliferation, capillarization, and angiogenesis.86 In a mouse model of pressure overload-induced hypertrophy, a ketogenic diet was found to increase myocardial capillary density.86 Recently, Wang et al26 showed that chronic subcutaneous infusion of β-OHB rescued post-MI cardiac dysfunction in mice primarily caused by enhanced peri-infarct neovascularization. Similarly, feeding post-MI mice a KE for 2 weeks improved cardiac function by significantly increasing capillary density in the peri-infarct zone.87 Interestingly, in the same study, the authors showed a correlation between high serum β-OHB levels and good collateral circulation in patients with MI.87

Impaired skeletal muscle oxygenation during exercise is often caused by decreased blood flow and can be indicative of microvascular dysfunction in the skeletal muscle vascular bed.88 Reduced skeletal muscle oxygenation during exercise is prevalent in old age, type 2 diabetes, and HFpEF, contributing to the associated exercise intolerance.89, 90, 91, 92 In these conditions, decreased skeletal muscle capillary density is an important contributor to decreased oxygenation.89, 90, 91 Recently, supplementation of trained athletes with a KE has been shown to improve skeletal muscle oxygenation93 following acute intake during exercise and promote skeletal muscle capillarization with chronic use after exercise.94 In a more relevant population to CVD, a single oral dose of KE increased CO, reduced SVR, and improved skeletal muscle oxygenation, both at rest and during exercise.95 It remains to be seen if exogenous KBs improve the exercise tolerance of patients with CVD through their salutary effects on skeletal muscle oxygenation and capillarization.

In summary, the potential of exogenous KBs to improve coronary and skeletal muscle microvascular dysfunction needs further investigation.

Lymphatic function

HF, HFpEF in particular, is associated with several abnormalities of the lymphatic system, including impaired lymph vessel integrity, lymph valve dysfunction, impaired lymphangiogenesis, and lymph vessel rarefaction.96 Diminished interstitial fluid clearance and impaired peripheral lymphatic drainage caused by a dysfunctional lymphatic system have been shown to contribute to recurrent peripheral and pulmonary edema in patients with HF.96 Interestingly, in a mouse model of MI, β-OHB supplementation was shown to promote lymphangiogenesis, facilitating cardiac repair.97 In a mouse model of peripheral lymphatic injury, a ketogenic diet promoted lymphangiogenesis and improved lymphatic drainage.97 In a small clinical study evaluating the potential of ketone therapy in patients with secondary lymphedema, the consumption of a ketogenic diet significantly improved lymphatic function, and a reduction in edema volume was observed in some patients.98 Further studies, using exogenous KBs, are needed to determine the therapeutic benefits of ketone therapy for patients with lymphedema.

Atherosclerosis and vascular calcification

Recent preclinical evidence suggests that KBs play a protective role against atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Chronic oral administration of β-OHB to mice with genetic susceptibility to atherosclerosis significantly decreased atherosclerotic plaque burden in the aorta.31,32 In a rat model of CKD and VitD3-overloaded mice, chronic supplementation with 1,3-butanediol attenuated aortic calcification.33,34 Currently, clinical evidence supporting the antiatherosclerosis and antivascular calcification effects of KBs is lacking.

In summary, substantial evidence supports the effect of exogenous KBs on several aspects of vascular physiology and pathophysiology, which significantly contribute to their cardioprotective effects. These include reducing systemic as well as coronary and pulmonary vascular resistance, enhancing endothelial, microvascular, and lymphatic function, and preventing atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. These vascular effects are promising therapeutic targets for the treatment of a wide range of CVD and related conditions, including ischemic heart disease, HF, PH, exercise intolerance, cardiometabolic diseases, and atherosclerosis.

Mechanistic understanding of the vascular effects of KBs

During states of ketosis, such as prolonged fasting or following the administration of exogenous KBs, the increased concentration of circulating β-OHB is accompanied by uptake in extrahepatic tissues, including the brain, heart, and skeletal muscles, for use as an alternative energy source.99 β-OHB crosses plasma membranes primarily via monocarboxylate transporters and enters the mitochondria through mechanisms that have not yet been fully elucidated for oxidative metabolism via the actions of 3 ketolytic enzymes, BDH1, succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid-CoA transferase (SCOT), and acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 to ultimately produce acetyl-CoA for entry into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Figure 1). Like the extrahepatic tissues mentioned previously, the vasculature can also readily oxidize KBs. Both vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)100 and endothelial cells86 have been shown to oxidize KBs. In support of this, endothelial cells express the rate-limiting ketolytic enzymes BDH1 and SCOT.86

KBs, in addition to their role as alternative fuel sources, exhibit diverse tissue-specific activities, including influencing vasoreactivity and regulating the expression and activity of key cellular molecules in target tissues by acting as signaling mediators and epigenetic modifiers.1 As signaling mediators, KBs act through specific G-protein-coupled receptors (GPRs), GPR41 and GPR109A. For instance, β-OHB exerts its antisympathetic nervous system effects by inhibiting GPR41 in ganglionic neurons101 and anti-inflammatory and antineoplastic effects by activating GPR109A on the surface of inflammatory and intestinal stem cells, respectively.102, 103, 104As epigenetic and post-translational modifiers, KBs inhibit class I histone deacetylases (HDAC) and directly modify lysine residues of histones and specific proteins via β-hydroxybutyrylation.26,105,106 The signaling and epigenetic modifier roles of KBs are the primary mechanisms for several of their vascular effects.

Endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis

The proangiogenic potential of β-OHB has been demonstrated to be beneficial in pathological hypertrophy, post-MI cardiac repair, and exercise performance. It is thus critical to understand the mechanism underpinning this vascular effect of exogenous KBs. Incubating murine cardiac endothelial cells with β-OHB enhanced the rate of cell proliferation and promoted migration and sprouting in angiogenesis assays.86 Interestingly, oxidation of KBs was required for the proangiogenic effects.86 In agreement with this, increased concentrations of β-OHB failed to activate proliferation in cardiac endothelial cells lacking the enzyme SCOT.86 Similarly, in cultured lymphatic endothelial cells, β-OHB enhanced endothelial proliferation, migration, and vessel sprouting.97 Like in vascular endothelial cells, oxidation of β-OHB in lymphatic endothelial cells was demonstrated to be required for the pro-lymphangiogenesis effects.97 The oxidation of KBs in endothelial cells is likely used to meet the demand for high ATP and biomass production associated with proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis.86,97 Therefore, the metabolic roles of KBs partly mediate the beneficial vascular effects in the coronary vasculature, as well as in the lymphatic vessels.

Recently, alternative mechanisms for the proangiogenic effect of β-OHB have been proposed. In a model of post-MI cardiac repair, β-OHB was found to target macrophages to stimulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production in the peri-infarct area to promote neovascularization and cardiac repair.26 The proposed molecular mechanism involves the β-hydroxybutyrylation of lysine residues in prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 (PHD2), an inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF-1α), resulting in a downstream effect that enhances HIF-1α-induced VEGF transcription and secretion, thereby increasing peri-infarct neovascularization. In another recent study, β-OHB promoted angiogenesis post-MI via epigenetic modification of proangiogenic genes.87 In a study involving healthy volunteers who participated in endurance training, postexercise supplementation with a KE resulted in enhanced skeletal muscle angiogenesis and capillarization.93 Interestingly, the increase in muscle capillarization was reported to be associated with a KB-mediated increase in circulating erythropoietin.94,107 This can have therapeutic implications, as anemia in HF is prevalent and is associated with impaired erythropoietin production.108

In brief, both metabolic and nonmetabolic roles are involved in the proangiogenic effects of exogenous KBs.

Vasodilation

Although direct vasodilation is suggested in experimental studies involving isolated vessels, the precise mechanism by which β-OHB causes vasodilation is not entirely clear. In isolated precontracted rat coronary arteries, β-OHB caused concentration-dependent vasorelaxation, with an EC50 value of 12.4 mmol/L.54 Besides the coronary arteries, β-OHB also relaxed arteries and veins from various vascular beds, at concentrations ranging from 1 to 20 mmol/L.54 However, these are generally supraphysiologic doses. In the physiologically relevant concentration range between 2 and 4 mmol/L, the coronary vasodilation caused by β-OHB was 20% to 25% of that caused by the endothelium-dependent vasorelaxant, acetylcholine (5 μmol/L).54 In this study, the vasodilatory effect of β-OHB on the coronary arteries was shown to be endothelium-independent, suggesting a possible direct effect of β-OHB on VSMCs.54 However, our work recently reported that β-OHB (0.1–5 mmol/L) had no significant effect on pressurized murine coronary arteries ex vivo; this was irrespective of whether arteries had developed stable pressure-dependent (80 mm Hg) tone or were preconstricted with the stable thromboxane analog U46619.69 Nonetheless, another study involving isolated preconstricted swine coronary arteries showed that both the D- and L-enantiomers of β-OHB, at a concentration of 3 mmol/L, induced vasorelaxation, indicating a vasodilatory effect independent of cellular metabolism, as the L-enantiomer is not readily oxidized.63 Together, these results indicate that the direct vasoactive effects of β-OHB differ across species.

In isolated mouse and rat mesenteric arteries, β-OHB induced potent vasodilation through its direct action on potassium channels in VSMCs.78 The vasodilatory activity was shown to be endothelium-independent and also independent of its canonical receptor, GPR109a. Interestingly, despite the endothelium-independent vasodilatory activity, β-OHB sensitized arteries from rats fed a high-salt diet to nitric oxide (NO), thereby ameliorating endothelial dysfunction.78 In agreement, a recent study showed that niacin, a potent activator of GPR109a, failed to increase CO in HFrEF patients, suggesting the hemodynamic effects of β-OHB are independent of GPR109a.109 The details of the mechanisms by which KBs cause vasodilation and improve the sensitivity of vessels to the action of NO need further investigation. Furthermore, although β-OHB–induced inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system via GPR41 has been reported, its contribution to vasodilation is unknown.110

Anti-inflammatory roles

KBs possess potent anti-inflammatory properties, including inhibiting the Nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and nuclear factor kappa B signaling and suppressing key cytokines and pernicious enzyme expressions implicated in CV inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta, and inducible nitric oxide synthase.103,111 For instance, mice with elevated levels of circulating β-OHB, resulting from the deletion of SCOT in skeletal muscles, were protected from pressure overload-induced HF caused by reduced activation of the cardiac NLRP3 inflammasome.21 Similarly, β-OHB infusion ameliorated cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in a mouse model of HFpEF by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and attenuating mitochondrial hyperacetylation.28 Given the important role inflammation plays in endothelial and microvascular dysfunction, the anti-inflammatory activities of KBs could contribute to their salutary roles in improving vascular function. In agreement, 1,3-butanediol attenuated high-salt-induced hypertension and kidney injury by inhibiting renal and vascular NLRP3 inflammasome.30 Thus, it appears that the direct vasodilatory effect as well as the anti-inflammatory effect of KBs are involved in enhancing endothelial function. The anti-inflammatory roles of β-OHB have also been reported to contribute to its antiatherosclerotic and antivascular calcification effects. The proposed antiatherogenic mechanism involves the activation of GPR109A on macrophages, inhibition of cholesterol efflux, suppression of M1 macrophages, and inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome.31 Inhibition of HDAC9-induced nuclear factor kappa B signaling in VSMCs is proposed as a mechanism for attenuating vascular calcification.33

Antioxidative stress roles

In addition to anti-inflammatory roles, βOHB has also been demonstrated to prevent oxidative stress in endothelial cells by inhibiting class I HDACs and inducing the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress defense.112 Exogenous KBs suppressed collagen IV production and attenuated coronary perimicrovascular fibrosis by promoting the expression of genes involved in resistance to oxidative stress.84 In cultured human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells, β-OHB treatment attenuated high glucose-induced collagen production by limiting oxidative stress.84 In other studies, β-OHB has been demonstrated to prevent oxidative stress by inhibiting class I HDACs, thereby up-regulating the expressions of genes involved in resistance to oxidative stress.28,113, 114, 115 Furthermore, β-OHB has been shown to have direct ROS scavenging effects, potentially contributing to its protective effect against hypoglycemia-induced oxidative neuronal damage.116

Roles as epigenetic modifiers

Substantial evidence indicates that β-OHB–mediated epigenetic modification regulates the expression and activity of key proteins involved in CV homeostasis.117, 118, 119 For instance, the inhibition of class 1 HDACs by β-OHB has been shown to influence the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress resistance.113,115,120,121 In a rat model of diabetes, 10 weeks of treatment with β-OHB inhibited HDAC3 and caused the acetylation of histone H3 lysine 14 (H3K14) in the Claudin-5 promoter, thereby up-regulating Claudin-5 and antagonizing diabetes-associated cardiac microvascular hyperpermeability.85 β-OHB has also been shown to promote the cardioprotective epigenetic effects of sirtuin-1 (Sirt1), a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide–dependent class III HDAC.118,122,123 In line with this, in HFpEF patients who underwent exercise training, Sirt1 activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlated with the circulating level of β-OHB.114 And a recent analysis of human and animal cardiac specimens from postischemic HF identified a specific pattern of maladaptive chromatin remodeling mediating the ischemia-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, namely a double methylation of H3 at K27 and a single methylation at K36.124 Intriguingly, treatment with β-OHB attenuated the maladaptive chromatin remodeling and the associated mitochondrial dysfunction in these tissues, suggesting the potential of KBs as powerful epigenetic modifiers.

Furthermore, β-OHB can directly modify the lysine residues of histones and specific nonhistone proteins via β-hydroxybutyrylation. Emerging evidence shows that β-hydroxybutyrylation is a powerful mechanism by which β-OHB exerts its diverse pleiotropic activities, including some of the salutary effects on the vasculature.105,125, 126, 127 In an animal model of stroke, β-OHB was found to preserve the integrity of the blood-brain barrier by inducing the expression of the tight-junction protein Zona Occludens-1 via β-hydroxybutyrylation of H3K9 at the promoter of the gene coding for the protein.79 In diabetic rats, β-OHB–mediated β-hydroxybutyrylation prevented endothelial aortic injury128 and glomerulosclerosis129 by up-regulating VEGF and matrix metalloproteinase-2 expressions, respectively. In adipocytes, β-OHB–mediated β-hydroxybutyrylation up-regulated the expression of adiponectin, a potent vasculoprotective adipokine.130 In a recent study involving a mouse model of MI, β-OHB promoted peri-infarct angiogenesis and improved post-MI cardiac function by a mechanism involving β-hydroxybutyrylation of H3K9 of several genes involved in hypoxia-induced angiogenesis.87 Contrary to the beneficial effects listed previously, however, a recent study reported an association between β-OHB–mediated β-hydroxybutyrylation and diabetic cardiomyopathy in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes.131 The proposed mechanism involved the accumulation of β-OHB caused by decreased BDH1 in diabetic hearts, increased β-hydroxybutyrylation of H3K9 of the gene for lipocalin-2 (LCN2), increased expression of LCN2, and activation of NFx-κB.131 It is unknown if β-hydroxybutyration following exogenous KBs could have similar adverse consequences in diabetes. Another in vitro study reported that β-OHB–induced β-hydroxybutyrylation potentiates the propagation of hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells.132

Taken together, epigenetic modification is a crucial mechanism by which KBs mediate several of their beneficial vascular and cardiac effects. A more detailed understanding of the mechanism and consequences of KB-mediated epigenetic modifications at molecular, cellular, tissue, and whole-body levels will provide crucial insights relevant for clinical translation.

Prevention of vascular senescence

The accumulation of senescent endothelial and VSMCs contributes to vascular aging, a significant risk factor for atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, and other CVDs.133,134 Maintaining quiescence is thought to be a mechanism by which cells can avoid initiating senescence programs. β-OHB has been reported to promote quiescence of endothelial, VSMCs, and muscle stem cells, thereby preventing stress-induced and replicative senescence in these cells.135,136 In endothelial and VSMCs, the proposed molecular mechanism involves the direct binding of β-OHB to an RNA-binding protein, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1, which stabilizes octamer-binding transcriptional factor 4 (Oct4) messenger RNA. This, in turn, leads to increased expression of Oct4 and Lamin B1, key factors that counteract DNA-damage-induced senescence. Interestingly, genetic depletion of Oct4 in mice led to a marked progression of atherosclerosis.137 Although the β-OHB–induced quiescence of endothelial cells appears to contradict the pro-proliferative effect discussed in the prior sections, it is crucial to consider that by preventing the senescence of endothelial cells, β-OHB essentially maintains their proliferative potential. Considering individual endothelial cells, the effect of β-OHB on promoting proliferation vs quiescence may depend on the age and cell-cycle status of the target cells, as well as the nature of environmental cues such as hypoxia, oxidative stress, inflammatory cells and cytokines, and growth factors. Further understanding of the orchestration of these divergent effects is crucial for future clinical translation.

Effect on systemic metabolism

Acute hyperglycemia, as in the postprandial state, as well as elevated circulating NEFAs, impairs vascular function likely by increasing oxidative stress in endothelial cells and promoting inflammation.138,139 Exogenous KBs have been shown to improve glucose tolerance, reduce circulating NEFA levels, and lower appetite and blood levels of ghrelin.45, 46, 47,140,141 Whether the vasculoprotective activities of exogenous KBs, such as enhanced endothelial function, are caused by their effect on systemic metabolism is unclear and needs further investigation.

Through the aforementioned mechanisms, exogenous KBs exert a range of vascular effects, including modulation of systemic, pulmonary, and coronary vascular resistance, maintenance of endothelial and microvascular function, promotion of angiogenesis and tissue repair, and preservation of vascular health via antiatherosclerotic and antivascular calcification roles. The relative contribution of each of these activities to the beneficial CV effects of KBs remains unknown and warrants further investigation.

The CV Effects of Ketone Bodies: Metabolic vs Nonmetabolic Roles

Although there is now compelling evidence to support the cardioprotective roles of KBs as presented in the previously mentioned sections, whether improved cardiac energy metabolism contributes to the beneficial CV effects of exogenous KBs supplementation is less clear.

In support of the metabolic role of KBs as a primary mechanism for their CV benefits, increased circulating levels of KBs and enhanced myocardial KB utilization are observed in animals and humans with HF.142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149 The level of ketosis correlates with the severity of HF and is attributed to increased free fatty acid mobilization in response to augmented neurohormonal activation.150 Consistently, circulating KB levels were linked to natriuretic peptides,151,152 N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide, and brain natriuretic peptide, which have been shown to promote adipose tissue lipolysis.153 Transgenic mice with cardiac-specific deletion of the genes encoding BDH15 or SCOT154 developed worse pressure overload-induced pathological LV remodeling and systolic dysfunction. Conversely, cardiac-specific overexpression of BDH1 attenuated pressure overload-induced or post-MI pathological LV remodeling and systolic dysfunction.155 Together, these findings suggest that a reliance on KBs as an alternate fuel source in failing hearts may be a beneficial adaptive response to compensate for the known decline in fatty acid and glucose oxidation.156

On the other hand, the following lines of evidence refute the argument that KB-induced cardioprotection relates to their metabolism. First, despite the proposition of the “thrifty substrate” hypothesis35 where KBs serve as a rescue “super-fuel” for the failing heart,157 there is no evidence that the oxidation of KBs improves myocardial energy efficiency. In the isolated working rat heart, KB oxidation as a sole substrate resulted in contractile failure, possibly by sequestration of coenzyme A, thereby impairing the TCA cycle.158,159 In addition, KB oxidation rates in these hearts were unchanged in response to increased workload.160 In isolated hearts from mice exposed to pressure overload, an increased supply of KBs significantly enhanced their oxidation and increased total ATP production without improving cardiac efficiency.143 In pigs, acute β-OHB markedly reduced SVR and increased CO proportional to the circulating β-OHB levels. It was demonstrated that the increase in CO was caused by a decrease in afterload, and there was no difference in myocardial contractility or mitochondrial respiratory capacity.63 Similarly, short-term intravenous infusion of β-OHB in healthy individuals as well as in patients with HFrEF improved CO without increasing myocardial efficiency.39 These studies suggest that KBs provide additional fuel sources and may contribute to increased total ATP production, without improving myocardial efficiency. Second, although oxidation of KBs is increased in HFrEF, a similar increase in HFpEF has not been consistently demonstrated, arguing against the notion that utilization of KBs is a universal adaptive response in failing hearts.28,161,162 Interestingly, while dapagliflozin increased circulating levels of KB-related metabolites in patients with HFrEF,163 a similar increase was not seen in patients with HFpEF.164 Third, the favorable hemodynamic effects of short-term β-OHB administration, including the increase in CO, were found to be stronger for the L-enantiomer compared with the D-enantiomer, despite the slow cardiac uptake and oxidation kinetics of the L-enantiomer, suggesting metabolism-unrelated hemodynamic effects.63 Similarly, the effect of β-OHB on the duration of action potentials and peak calcium transients in induced pluripotent stem cell-cardiomyocytes was enantiomer-specific and independent of its role as a source of fuel.165 Last, several studies have demonstrated that mechanisms unrelated to cardiac energetics contribute to the CV benefits of acute and chronic administration of exogenous KBs. These include effects on SVR,39, 40, 41,95 inflammation,21,28,29 oxidative stress,19 endothelial function, coronary and skeletal muscle microvascular function,26 angiogenesis,166,167 autophagy,20,22 endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress,20 and mitochondrial integrity and function.20,22,28,168

Taken together, it is likely that the beneficial cardiac effects of KB supplementation are, at least in part, mediated by their role as myocardial fuel. However, beyond their role as alternative fuel sources, KBs have multiple pleiotropic activities caused by their action as signaling mediators and epigenetic modifiers, which account for a significant portion of their CV benefits.

The vasculature is the main target of the pleiotropic effects of KBs and significantly contributes to the salutary roles of KBs in CVD. Whether the metabolic or nonmetabolic activity of exogenous KBs is the predominant mechanism of cardioprotection remains unclear and likely varies depending on the disease context, the type of administration (acute vs chronic), the serum concentration of KBs, and other unidentified factors. It is also possible that there is a collaboration or synergy among the various roles contributing to the superior potential of exogenous KBs in the treatment of CVDs compared with purely metabolic, anti-inflammatory, or vasoactive therapies.

Therapeutic Implications and Unanswered Questions in the Field

Despite recent advances in the treatment of HF, patients with HF experience substantial morbidity and mortality,169,170 highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic modalities that offer incremental benefits on top of existing medical therapies. Existing HF pharmacotherapies, with the exception of SGLT2 inhibitors, primarily target neurohormonal activation, and hemodynamic disturbances associated with HF.171 In contrast, exogenous KBs, in addition to their favorable hemodynamic effects, could target several pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development and progression of HF. These include maladaptive metabolic remodeling and energy deprivation,5 inflammation,28 oxidative stress,113 mitochondrial dysfunction,124 endothelial dysfunction,46 microvascular rarefaction,166,167 and reduced coronary blood flow.65 In theory, the possibility of simultaneously targeting several of the above key pathophysiological mechanisms makes KBs promising therapeutic agents across the spectrum of HF. As proof of concept, the results from the short-term treatment of patients with HFrEF42 and HFpEF43 with a KE are encouraging. However, larger and long-term clinical trials will be necessary to determine the safety and efficacy of exogenous KBs for the treatment of HF.

The numerous beneficial effects of KBs on vascular function, discussed in this review, have significant therapeutic implications for the treatment of CVDs. For instance, the ability of exogenous KBs to reduce vascular resistance in systemic, pulmonary, and coronary circulation is relevant in the treatment of both acute decompensated and chronic HF, as increased SVR, PH, and decreased coronary flow reserve are critical hemodynamic abnormalities associated with symptoms and disease progression. In support of this, acute β-OHB infusion resulted in improved CO and reduced filling pressures in patients with cardiogenic shock as well as in patients with chronic HF.41 In these studies, however, it is unclear to what extent reduced SVR contributed to the increase in CO and decreased filling pressures. It is imperative to design clinical studies aiming to delineate the primary driver of the improvement in hemodynamic parameters and cardiac function with acute and chronic administration of KBs.42,43

Given the scarcity of tolerable and effective pulmonary vasodilators, exogenous KBs have exciting potential as acute or chronic therapies in patients with PAH, CTEPH, and other causes of PH. Thus, evaluating the therapeutic potential of chronic treatment with exogenous KBs in PH is urgently needed. Similarly, although there is preclinical and limited indirect clinical evidence that exogenous KBs could provide benefits in the treatment of hypertension, atherosclerosis, acute coronary syndrome, and coronary microvascular dysfunction, whether these benefits can be reproduced in clinical trials remains to be seen.

Reduced exercise tolerance, quantified as decreased peak oxygen consumption (VO2), is a critical metric in CVD, serving as an indicator of disease severity and quality of life, as well as a reliable predictor of CV and all-cause mortality.17 There are several reasons to believe exogenous KBs could be promising therapies to improve exercise tolerance in patients with or at risk of CVD. These include the potential of KBs to cause peripheral vasodilation without significant changes in blood pressure,39 increase CBF,65 skeletal muscle oxygenation and capillarization,52,93 improve endothelial and microvascular function,46 and reduce filling pressures during exercise,43 as well as their purported role in inhibiting skeletal muscle catabolism.172 However, the majority of the studies on the effect of KBs on exercise performance mainly involved high-performance athletes, and the results, thus far, have been conflicting and appear to depend on ketone formulation, timing of supplementation, and mode of exercise.173 Similarly, clear benefits of exogenous KBs in exercise performance in patients with CVD have not been established. In a recent clinical trial involving patients with HFpEF, acute KE supplementation decreased LV filling pressures both at rest and during exercise, but did not increase peak VO2 or exercise endurance.140 Similarly, decreased LV filling pressures during exercise were reported with chronic KE therapy in patients with HFrEF and diabetic patients with HFpEF, however, peak VO2 and exercise endurance were not assessed.42,43 Therefore, the benefits of exogenous KBs in exercise tolerance/performance in patients with CVD require further investigation.

From a mechanistic standpoint, although we now know that KBs exert pleiotropic activities, the primary contributor(s) to their observed beneficial effects in CVD remains unclear. Specifically, whether their role as an alternative fuel source for the myocardium or the beneficial vascular effects is the primary mechanism of cardioprotection in HF is unknown. Advances in metabolic profiling using novel approaches to study metabolic flux combined with spatial and single-cell analysis technologies, and integration with transcriptomics and proteomics data, are expected to improve our understanding of the role of KB metabolism in HF of various etiologies.174 In addition, we recommend that future studies utilize the distinct metabolic profiles of the 2 enantiomers of β-OHB to delineate beneficial effects related to the roles of β-OHB as fuel sources vs signaling mediators. A better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms by which KBs cause vasodilation, enhance endothelial function and proliferation, and promote angiogenesis is also needed. Specifically, because β-hydroxybutyrylation is emerging as a potentially powerful mechanism capable of mediating the multifaceted beneficial biological effects of KBs,79,87,127, 128, 129, 130 future studies are expected to provide a deeper, disease- and tissue-specific mechanistic understanding and clarify current inconsistencies in the published reports.131

Limitations and Potential Adverse Effects of Exogenous KB Supplementation

Although preclinical and clinical evidence for the benefits of exogenous KBs in the treatment of CVD is growing, certain limitations and potential adverse effects need careful consideration. Ketone salts, KEs, and 1,3-butanediol have unpleasant tastes and are associated with gastrointestinal adverse effects, raising concerns of tolerability and compliance with long-term use. However, the gastrointestinal adverse effects are overall infrequent, mild, and vary depending on the type of ketone used.175 KEs, for instance, have been reasonably well-tolerated in recent clinical trials with follow-up durations up to 4 weeks.42,43,46,51,52,176 Notably, the novel ketone diester, bis-hexanoyl R-1,3-butanediol, was also well-tolerated over a 4-week duration with no significant gastrointestinal adverse effects compared with a taste-matched placebo.177 In a recent clinical trial involving patients with HFrEF40 as well as in studies involving healthy subjects,175,178 a 1-time dose of oral 1,3-butanediol did not cause significant adverse effects. However, a prior study reported adverse effects, including nausea, dizziness, and euphoria, attributed to the alcohol-like properties of 1,3-butanediol.179 Similarly, higher doses of 1,3-butanediol were found to be toxic in rats.78 Fluid overload with sodium load is a concern with the use of ketone salts such as sodium-β-OHB in patients with HF.39 In this regard, the sodium-free KEs and 1,3-butanediol are safer alternatives.

It is currently unclear whether pulsatile elevations in circulating KBs are sufficient for the cardioprotective benefits or if sustained ketosis is more effective. If the latter is true, a limitation of ketone salts and monoesters is their short half-lives, limiting ketosis to only a few hours and requiring either continuous infusions or repeated dosing regimens to achieve sustained ketosis.7 The β-OHB precursor, 1,3-butanediol, provided elevated circulating β-OHB for a relatively prolonged period (6 hours) in patients with HFrEF.40 Future studies to discover novel approaches to achieve sustained ketosis are needed.

In patients with type 1 diabetes and in some patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, there is a theoretical risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with exogenous KB supplementation. DKA often presents with blood ketone levels in the range of 10 to 20 mmol/L; however, a level ≥3 mmol/L is sufficient for diagnosis in the presence of significant acidosis. Although current supplementation regimens only elevate circulating KBs to 0.5 to 3 mmol/L and occasionally up to 6 mmol/L,9 this may be detrimental in the setting of acute conditions associated with ketoacidosis in patients at risk. Nonetheless, thus far, DKA has not been identified as an adverse effect of exogenous KBs in studies involving patients with type 2 diabetes.180 In fact, KE supplementation for 4 weeks to patients with type 2 diabetes resulted in improved glycemic control without evidence of significant acid-base disturbances.176 While euglycemic DKA has been associated with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in the setting of fasting, a similar phenomenon has not been reported for exogenous KBs.176,180 However, further long-term studies evaluating the safety of exogenous KBs in at-risk populations are necessary.

Taken together, despite the above limitations and potential adverse effects, based on current evidence, the therapeutic potential of exogenous KBs in CVD outweighs the associated risks. Future studies with long-term treatments will determine the safety profiles and compliance of exogenous KBs.

Conclusions

Evidence for the potential of KBs as a therapeutic approach in CVD is growing rapidly. Exogenous KBs have been found beneficial in ischemia-reperfusion injury, MI, pathological cardiac remodeling, HF, systemic and pulmonary arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis, and vascular calcification. Given the traditional view of KBs as substrates for oxidative metabolism, investigations into the therapeutic potential of KBs in CVD had, for a long time, focused on their role in improving cardiac energetics. However, beyond their role as sources of fuel, KBs possess multifaceted activities, including vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, proangiogenic, and antisenescence properties. Although the specific role that contributes the most to CV benefits remains unclear, a large body of evidence now supports the substantial contribution of the pleiotropic activities of KBs to the cardioprotective effects reported in preclinical and clinical studies. Specifically, the vasculature stands out as a prime target of KBs, with growing evidence showing the vasculo-protective properties of KBs significantly contribute to the cardioprotective benefits conferred by KBs.

Exogenous KBs cause systemic, coronary, as well as pulmonary vasodilation, contributing to the increase in CO and improvement in cardiac function observed with both acute and chronic administration in patients with HF or PH. In addition to vasodilation, KBs enhance endothelial and microvascular function, promote angiogenesis in cardiac and skeletal muscle, enhance lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic function, and prevent atherosclerosis, vascular senescence, and vascular calcification. The vasculoprotective activities of exogenous KBs likely operate in collaboration with their role as a source of myocardial fuel to confer substantial cardioprotective benefits. Delineation of the primary mechanism(s) for the CV benefits of exogenous KBs will accelerate their clinical translation into new therapeutic tools to combat CVD.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have received funding support from the National Institutes of Health (HL142710 [to Dr Nystoriak], HL147844 [to Dr Hill], HL168198 [to Dr Hill], AG084688 [to Drs Hill and Nystoriak], 23TPA1141824 [to Dr Hill], and the American Heart Association (24DIVSUP1291349 [to Dr Gouwens]). This work was partly supported by a grant from the Jewish Heritage Fund for Excellence Research Enhancement Grant Program at the University of Louisville, School of Medicine.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Puchalska P., Crawford P.A. Metabolic and signaling roles of ketone bodies in health and disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2021;41:49–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-111120-111518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson A.B., Queathem E.D., Puchalska P., Crawford P.A. Metabolic messengers: ketone bodies. Nat Metab. 2023;5:2062–2074. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMurray J.J.V., Solomon S.D., Inzucchi S.E., et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giuliani G., Longo V.D. Ketone bodies in cell physiology and cancer. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;326:C948–C963. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00441.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horton J.L., Davidson M.T., Kurishima C., et al. The failing heart utilizes 3-hydroxybutyrate as a metabolic stress defense. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.124079. 124079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke K., Tchabanenko K., Pawlosky R., et al. Kinetics, safety and tolerability of (R)-3-hydroxybutyl (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate in healthy adult subjects. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;63:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stubbs B.J., Cox P.J., Evans R.D., et al. On the metabolism of exogenous ketones in humans. Front Physiol. 2017;8:848. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selvaraj S., Kelly D.P., Margulies K.B. Implications of altered ketone metabolism and therapeutic ketosis in heart failure. Circulation. 2020;141:1800–1812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.045033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yurista S.R., Chong C.-R., Badimon J.J., Kelly D.P., de Boer R.A., Westenbrink B.D. Therapeutic potential of ketone bodies for patients with cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1660–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yurista S.R., Nguyen C.T., Rosenzweig A., de Boer R.A., Westenbrink B.D. Ketone bodies for the failing heart: fuels that can fix the engine? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021;32:814–826. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2021.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuura T.R., Puchalska P., Crawford P.A., Kelly D.P. Ketones and the heart: metabolic principles and therapeutic implications. Circ Res. 2023;132:882–898. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.321872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan M.S., Khan F., Fonarow G.C., et al. Dietary interventions and nutritional supplements for heart failure: a systematic appraisal and evidence map. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1468–1476. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manolis A.S., Manolis T.A., Manolis A.A. Ketone bodies and cardiovascular disease: an alternate fuel source to the rescue. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3534. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu K., Yang Y., Yang J.-H. Underlying mechanisms of ketotherapy in heart failure: current evidence for clinical implementations. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1463381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa T.J., Linder B.A., Hester S., et al. The janus face of ketone bodies in hypertension. J Hypertens. 2022;40:2111–2119. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000003243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopaschuk G.D., Dyck J.R.B. Ketones and the cardiovascular system. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2023;2:425–437. doi: 10.1038/s44161-023-00259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soni S., Skow R.J., Foulkes S., Haykowsky M.J., Dyck J.R.B. Therapeutic potential of ketone bodies on exercise intolerance in heart failure: looking beyond the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2025 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaf004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou Z., Sasaguri S., Rajesh K.G., Suzuki R. dl-3-Hydroxybutyrate administration prevents myocardial damage after coronary occlusion in rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1968–H1974. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00250.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos-Gallego C.G., Requena-Ibáñez J.A., Picatoste B., et al. Cardioprotective effect of empagliflozin and circulating ketone bodies during acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;16 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.123.015298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Y., Yu Y., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., An W., Zhao X. Treatment with D-β-hydroxybutyrate protects heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;829:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrne N.J., Soni S., Takahara S., et al. Chronically elevating circulating ketones can reduce cardiac inflammation and blunt the development of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu Y., Hua Y., He L., et al. β-hydroxybutyrate administered at reperfusion reduces infarct size and preserves cardiac function by improving mitochondrial function through autophagy in male mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2024;186:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2023.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura M., Odanovic N., Nakada Y., et al. Dietary carbohydrates restriction inhibits the development of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117:2365–2376. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yurista S.R., Matsuura T.R., Silljé H.H.W., et al. Ketone ester treatment improves cardiac function and reduces pathologic remodeling in preclinical models of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahara S., Soni S., Phaterpekar K., et al. Chronic exogenous ketone supplementation blunts the decline of cardiac function in the failing heart. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:5606–5612. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C., Xu W., Jiang S., et al. β-hydroxybutyrate facilitates postinfarction cardiac repair via targeting PHD2. Circ Res. 2025;136:704–718. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.124.325179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thai P.N., Miller C.V., King M.T., et al. Ketone ester D-β-hydroxybutyrate-(R)-1,3 butanediol prevents decline in cardiac function in type 2 diabetic mice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng Y., Xie M., Li Q., et al. Targeting mitochondria-inflammation circuit by β-hydroxybutyrate mitigates HFpEF. Circ Res. 2021;128:232–245. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]