Abstract

Background

Managing patients with coma of unknown etiology presents a challenge requiring rapid, structured assessment. We aimed to examine how physicians from different specialties manage patients with coma of unknown etiology and adhere to recommendations in a highly standardized scenario.

Methods

Prospective high-fidelity simulation study conducted at an academic simulation center involving 50 physicians from acute care (38%), internal medicine (36%), and neurology (26%). Participants were confronted with a standardized coma scenario. Performance was assessed for adherence to expert-recommended clinical assessments (primary endpoints) and timing of interventions, such as airway protection, oxygen administration, toxicological screening, and self-evaluation (secondary endpoints).

Results

All participants recognized coma; 80% assessed the Glasgow Coma Scale, with 40% quantifying it correctly. 20% completed ABCDE assessments, with 66% performing head-to-toe examinations. Airway inspection was conducted by 89% of acute care physicians, 70% of neurologists, and 60% of internists. A median of 4 ancillary tests were ordered, mostly neuroimaging (98%) and toxicological screening (86%), while rare toxin screening (2%) and EEG (12%) were scarce. Oxygen was universally administered (100%), but treatment response was rarely checked (8%). Side-positioning for airway protection was infrequent (21% acute care, 15% neurology, 6% internal medicine), while intubation was more commonly ordered by internists (17%). Prior simulator training improved side-positioning rates (27% vs. 4%, p = 0.047). Self-evaluations showed high motivation (median 8/10) but moderate confidence (5/10).

Conclusions

This study highlights specialty-specific differences, misconceptions, and gaps in managing coma of unknown etiology, including inconsistent diagnostic workup and missed treatments, emphasizing the need for guidelines, standardized care and training.

Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov registry (ID NCT06265168).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00415-025-13228-4.

Keywords: Coma, Neurocritical care, Simulator study, Prospective study

Introduction

Coma of unknown etiology is a neurological emergency frequently encountered in emergency settings but remains underinvestigated. Defined as acute consciousness impairment without overt causes, such as trauma or hypoperfusion [1], its incidence ranges from 0.4 to 2%, while altered mental status, a broader category, affects 5–9% of emergencies [1, 2]. Coma is characterized by the absence of wakefulness, awareness, and external responses, reflecting brain dysfunction with reversible or irreversible causes [3, 4]. Rapid diagnosis and treatment of reversible causes are crucial to prevent morbidity and mortality, which can reach up to 25% [1, 5]. Cases with unidentified causes present diagnostic challenges.

Although many centers have implemented standard operating procedures (SOPs) for managing unresponsive patients, universally accepted guidelines are lacking. Current approaches rely heavily on expert opinions [3, 6] rather than robust evidence and often omit or underemphasize internationally recommended steps like the ABCDE approach [7, 8]. The latter is a structured method for assessing and managing critically ill or injured patients prioritizing immediate life-threatening conditions thereby focusing on airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure [7, 8].

To give more insight into the current quality of diagnostic procedures and treatment of patients with coma of unknown cause, this prospective high-fidelity simulation study was performed to examine how physicians from different specialties manage adult patients with coma of unknown etiology and adhere to current recommendations [3, 6], including the ABCDE approach, in a highly standardized simulated scenario [7, 8].

Methods

Ethical approval, registration, and consents

The study was approved by the ethics committee (EKNZ No.2023-01512) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ID NCT06265168). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Setting and design

This prospective, investigator-led, single-blinded high-fidelity simulation study was conducted from March to November 2024 at the University Hospital Basel’s ICU-affiliated simulation center. While institutional SOPs for altered consciousness management were available, SOPs for coma of unknown etiology were not established. Although the established simulated scenario was primary used to investigate the quality of performance of physicians at our medical center, simulation workshops were formally offered for training purposes on emergency management to physicians in intensive care, emergency medicine, internal medicine, and neurology. Before the workshops, the participants had no prior training in the context of the simulated scenario. Voluntary participation was conducted during working hours without additional compensation. All eligible physicians completed a pre-simulation questionnaire on demographics, clinical knowledge, prior simulation experience, total clinical exposure, and pre-session workload.

The extended STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology)-guidelines for simulation research were followed [9].

Simulator setup

Information about the high-fidelity simulator center’s equipment is available in our prior studies [10–12]. Briefly, a programmable high-fidelity mannequin (SimMan®, Laerdal Medical AS, Stavanger, Norway) was utilized, capable of simulating various medical conditions. The mannequin could speak, groan, cough, exhibit palpable or absent pulses, thoracic movements, and various sounds of breathing, as well as blinking, pupil responses, upper extremity motion, foamy sputum production, and enuresis. Vital signs (respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate, and non-invasive blood pressure) were displayed on bedside monitors if measured by the participants and adjusted based on interventions by the participants. Emergency medications (vasopressors, antimicrobials, steroids, thiamine, fluids, glucose, and antiseizure drugs) were available alongside intubation equipment, and flashlights. During simulations, a trained nurse, as part of the simulated scenario, assisted by following physician instructions for diagnostics and monitoring device setup, maintaining a cooperative but passive demeanor.

Simulated clinical scenario

The content validity of the simulated clinical scenario was based upon the following approach: first, the simulated scenario was based upon a well-established, studied and published previous scenario of a comatose adult patient presenting with a minimal convulsive status epilepticus [10, 12] by removing the motor symptoms (i.e., convulsions) and signs of enuresis. In addition, the accompanying laboratory handouts, which were provided to the participants, were adapted to fit the current scenario of intoxication. Second, the experienced study/simulator team consisting of a leading senior physician board certified in neurology and intensive care medicine, a first-year resident in her last year prior to graduation, and two experienced registered nurses qualified for intensive care medicine, generated and assessed the adapted scenario for content validity, until overall consensus was reached. The final scenario that was agreed upon was then piloted on two volunteering physicians who both recognized the intended scenario of coma. Third, our finding that in the study 100% of all participants recognized coma supports the content validity of our simulated scenario.

Prior simulation all participants were instructed to assume the role of the emergency department physician. Participants were briefed on the mannequin’s capabilities, including motion, vital sign displays, airway management, and repositioning. For their training, participants were confronted with a highly standardized simulation clinical scenario in an emergency room involving an adult comatose patient with an initial Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 3, which gradually improved to 4 (eye1, verbal2, motor1). Participants were blinded to the underlying cause of coma, which was an isopropanol intoxication. This rare cause of coma was selected to assure that participating physicians would rarely determine the underlying etiology of the coma early within the designated 20-min training period.

The scenario began with the participating physician being called by the nurse to assess a patient “not being well”. The simulated patient was positioned supine, exhibited a GCS of 3 and coughed repetitively. All vital signs were simulated within normal physiological ranges (if monitored by the participants), except for periodic oxygen desaturation slightly below 90%. The mannequin featured a pre-installed intravenous access. A printed medical chart included an emergency medical service report describing an adult patient with coma of unwitnessed onset and laboratory findings including a hemogram with normal leukocyte, thrombocyte, and erythrocyte counts, although erythrocytes were macrocytic. The C-reactive protein concentration, glucose levels, and thyroid-stimulating hormone concentrations were within normal limits, as were the transaminases. Alkaline phosphatase and total γ-glutamyltransferase, were mildly elevated. An unremarkable cerebral computed tomography (CT) was displayed at all times. Upon request, CT angiography was reported to be unremarkable. Upon request, blood gas analysis, conducted early in the clinical course, showed no significant acid–base disturbance, with normal pH and base excess, bicarbonate levels and electrolytes (consistent with findings in isopropanol intoxication [13]). Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed normal cell counts, lactate, and glucose. Albumin concentration was slightly reduced, while other proteins showed normal levels. Toxicological screening was negative for serum ethanol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, opioids, methadone, cannabinoids, amphetamines, tricyclic antidepressants, acetaminophen, and salicylates and was reported upon request. Tests for less common toxins were pending. Upon request, an increased osmolal gap of 23 mOsm/kg H2O was presented.

The simulation was recorded via camera from different angles and a microphone for real-time observation, debriefing, and anonymized analysis. Sessions ended after 20 min or upon correct identification of isopropanol intoxication. Group debriefings followed each session.

After the simulation, participants completed two questionnaires (Supplemental File 1). The first assessed knowledge of coma diagnostics, management, and understanding. The second involved self-assessment using an “emotion wheel reflectivity” tool.

Data assessment

And overview of all variables which were a priori identified, based upon a review by two of the authors (L.N. and R.S.) of the two references/guidelines regarding the assessment and management of coma [3, 6] and the two guidelines regarding the internationally recommended ABCDE approach [7, 8] that were systematically captured are presented in the Supplemental File 1. Participants’ performances and the “patient’s” vital signs (if measured and displayed on the monitor) were recorded simultaneously using “frame-in-frame” video and audio technology. Two independent observers (L.N. and R.S.) analyzed the recordings to code data for assessing the primary and secondary endpoints outlined below. Actions and verbalizations were coded on a “second-by-second” basis.

Inter-rater agreement on categorical variables was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa (κ), while continuous variables (e.g., time to action) were compared directly. Disagreements were resolved through joint review until consensus was reached.

Outcomes and measurements

Primary endpoints included the proportion of participants who executed clinical assessments in line with recommended assessments for the management of coma [3, 6] including the internationally recommended ABCDE approach [7, 8] and the time of these executions after first “patient” contact.

Secondary endpoints included the performance and timing of medical interventions following initial assessments, such as airway protection (non-invasive side-positioning or tracheal intubation), oxygen administration, expanding toxicological screening to identify the etiology, and post-simulation self-evaluation.

A priori sample size calculations

In the absence of established international guidelines for the management of patients with coma of unknown etiology, sample size calculation was based on data from comparable clinical scenarios involving similar treatment approaches, such as status epilepticus. Using a systematic review on adherence to status epilepticus guidelines [14], the hypothesized adherence rate was set at 80%. For a one-sample comparison against an observed proportion of 60% adherence rate to guidelines, the estimated required sample size was 43 participants assuming a one-sided significance level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.8.

Statistics

For descriptive statistics, discrete variables were expressed as counts (percentage) and continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Inter-rater agreement on categorical variables was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa (κ). Univariable comparisons of proportions were performed using chi-square test. Two-sided p values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA® version 16.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Description of participants and inter-rater agreement

Demographics and baseline characteristics of the 50 participating physicians are presented in Table 1. Physicians were primarily affiliated with intensive care/emergency medicine (i.e., acute care specialties; 38%), internal medicine (36%), and neurology (26%). The median age was 31 years (IQR 29–33), with 64% being female. Participants had a median of 4 years of clinical experience (IQR 3–5), and 44% had prior simulation training. Males were slightly under-represented, with the representation being consistent with the current percentage of males in medical education in Switzerland (BAG Statistiken Ärztinnen/Ärzte, 2019). The working hours stated agreed with Swiss labor law.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participating physicians (n = 50)

| Characteristics of participants | n/median | %/IQR |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years; median, IQR) | 31 | 29–33 |

| Female (n, %) | 32 | 64.0 |

| Physicians’ primary affiliation | ||

| Intensive care/emergency medicine (n, %) | 19 | 38.0 |

| Internal medicine (n, %) | 18 | 36.0 |

| Neurology (n, %) | 13 | 26.0 |

| Years of clinical experience (years; median, IQR) | 4 | 3–5 |

| Previous simulator training (n, %) | 22 | 44.0 |

| Working hours prior to participation (hours; median, IQR) | 10 | 8–11 |

IQR interquartile range

Inter-rater agreement regarding categorical variables assessed from video and audio recordings was κ = 0.93.

Primary endpoints

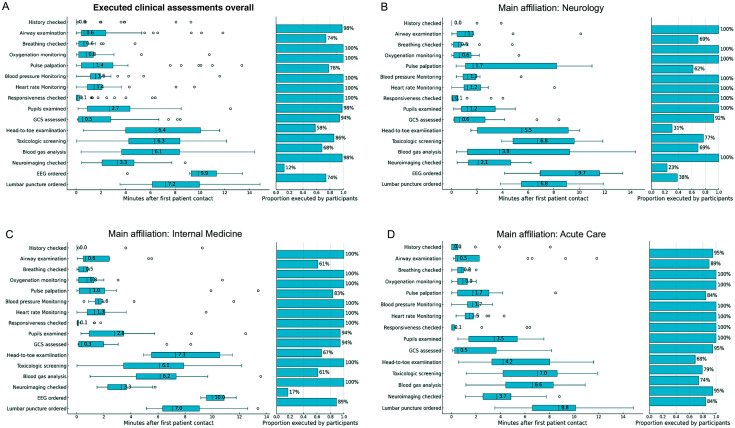

The performance of clinical assessment is presented in Table 2. While the “patient’s” history and responsiveness were checked by almost all participants and coma was recognized by 100%, the level of consciousness was quantified correctly in 40% and complete execution of all ABCDE examination steps was performed in 20%. Important steps, such as airway inspection, pulse palpation, and a complete head-to-toe examination, were performed in 60–78%. While a median of four ancillary tests were performed/checked (IQR 3–4) with 98% checking neuroimaging for structural pathologies and 86% calling for toxicological screening results, other ancillary tests, including EEG, cerebrospinal fluid analyses were infrequently performed/checked or considered. Only 2% of the participants requested screening for rare toxins and none sought to calculate an osmolal gap, despite 86% having reviewed the general toxicology screening and 68% having analyzed the blood gas results. Figure 1A presents details regarding the overall percentage and time of executed examination steps after first “patient” contact. Assessments (if considered) such as head-to-toe examination, laboratory analyses, initiation of an EEG, and lumbar puncture were performed or considered with a median latency exceeding 6 min, in contrast to other assessments that were completed within 3 min. The proportion of executed assessments and time to performance after first patient contact categorized by the participants’ main affiliations is presented in Fig. 1B to D. Affiliation-centered subgroup analyses revealed a similar proportion of performed clinical assessments among all different specialties. However, while neurologists and internal medicine specialists performed airway examination in 60–70%, acute care specialists examined the airways more frequently (89%).

Table 2.

Overall clinical performances and conceptual understanding of coma of the participating physicians (n = 50)

| Overall clinical performance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Overall execution of first assessment (primary endpoints; n, %)a | ||

| Patient’s history assessed | 49 | 98.0 |

| Coma recognized | 50 | 100.0 |

| Responsiveness checked | 50 | 100.0 |

| GCS scored completely at least once | 40 | 80.0 |

| GCS scored correctly | 20 | 40.0 |

| Call for additional staff | 46 | 92.0 |

| All ABCDE systems checked at least once | 10 | 20.0 |

| Airway checked at least once | 37 | 74.0 |

| Breathing checked at least once | 50 | 100.0 |

| Circulation/pulse checked at least once | 39 | 78.0 |

| Disability (neurologic) checked at least once | 50 | 100.0 |

| Exposure/head-to-toe examination at least once | 33 | 66.0 |

| Critical ancillary tests (secondary endpoints)a | ||

| Number of ancillary tests checked/performed at least once (median, IQR) | 4 | 3–4 |

| Toxicological screening checked at least once (n, %) | 43 | 86.0 |

| Call for extended toxicological screening for rare toxins at least once (n, %) | 4 | 2.0 |

| Calculation of osmolal gap at least once (n, %) | 0 | 0.0 |

| Blood gas analysis checked at least once (n, %) | 34 | 68.0 |

| Neuroimaging checked at least once (n, %) | 49 | 98.0 |

| EEG requested at least once | 6 | 12.0 |

| Lumbar puncture ordered and CSF analysis checked at least once | 37 | 74.0 |

| Overall executed treatment steps (secondary endpoints; n, %)a | ||

| Side positioning for airway protection | 7 | 14.0 |

| Call for tracheal intubation | 6 | 12.0 |

| Oxygen supply | 50 | 100.0 |

| Antiseizure drugs administered | 7 | 14.0 |

| Antibiotics administered | 1 | 2.0 |

| Antiviral drugs administered | 1 | 2.0 |

| Treatment response checked | 4 | 8.0 |

| Conceptual statements regarding coma (secondary endpoints as assessed by questionnaires; n, %) | ||

| Coma definition correct | 28 | 56.0 |

| Suspected etiology “intoxication” to be most likely | 46 | 92.0 |

| Indicating that “intoxication” is a frequent and important etiology | 18 | 36.0 |

| Considering seizures as the cause of coma | 32 | 64.0 |

| Considering cerebral hemorrhage as the cause of coma | 47 | 94.0 |

| Considering traumatic brain injury as the cause of coma | 45 | 90.0 |

| Considering aspiration with hypoxemia as the cause of coma | 16 | 32.0 |

| Indicating that comatose patients must be intubation regardless of underlying cause | 11 | 22.0 |

Fig. 1.

Proportion and time of executed clinical assessments for coma as recommended by opinion leaders [3, 6] including the internationally recommended ABCDE approach for the examination of critically ill patients [7, 8] categorized by the participants’ main affiliation (primary endpoints). GCS Glasgow Coma Score, EEG electroencephalography. *Note that boxplots represent attempted tasks without claiming correctness or completeness of task performance

Secondary endpoints

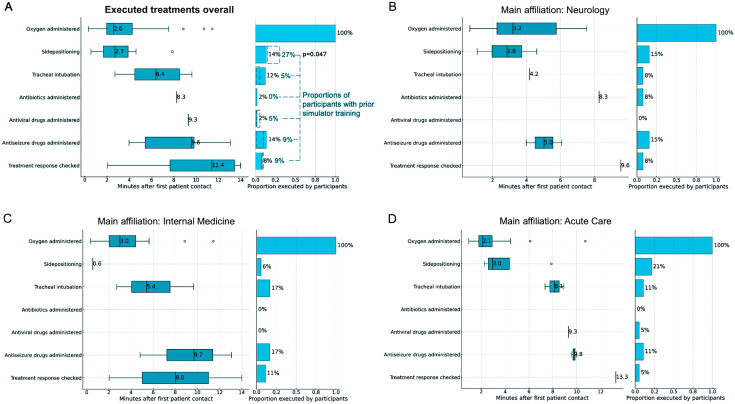

Figure 2A illustrates the proportion of participants initiating treatments and the timing of various treatment steps following initial “patient” contact. While oxygen administration was universally performed, airway protective measures such as side-positioning and tracheal intubation were less frequently executed (14% and 12%, respectively). Antibiotic and antiviral therapies were initiated by two participants, whereas antiseizure medication was more commonly administered (14%). Treatment response evaluation was rarely undertaken, occurring in 8% of scenarios.

Fig. 2.

Proportion and time of executed treatment steps for coma as recommended by opinion leaders [3, 6] categorized by the participants’ main affiliation (secondary endpoints)

Analyses of treatment initiation and timing, stratified by the physicians’ specialty, are presented in Fig. 2B to D revealing consistent performance distributions across specialties, with few notable exceptions. Internal medicine specialists performed side-positioning significantly less frequently than neurologists (6% vs. 15%) and acute care specialists (6% vs. 21%). Conversely, tracheal intubation was requested more often by internal medicine specialists compared to neurologists (17% vs. 8%). Participants with prior simulator training of emergency scenarios performing side-positioning more often as compared to untrained participants (27% vs. 4%; p = 0.047; Fig. 2A).

Concept of coma and self-evaluation (secondary endpoints)

First questionnaires (Supplemental File 2) revealed several conceptual misunderstandings, as detailed at the bottom of Table 2. Nearly half of the participants provided incorrect definitions of coma. In addition, treatment misconceptions were identified, with over 20% of physicians asserting immediate tracheal intubation to be mandatory for comatose patients, irrespective of underlying etiologies.

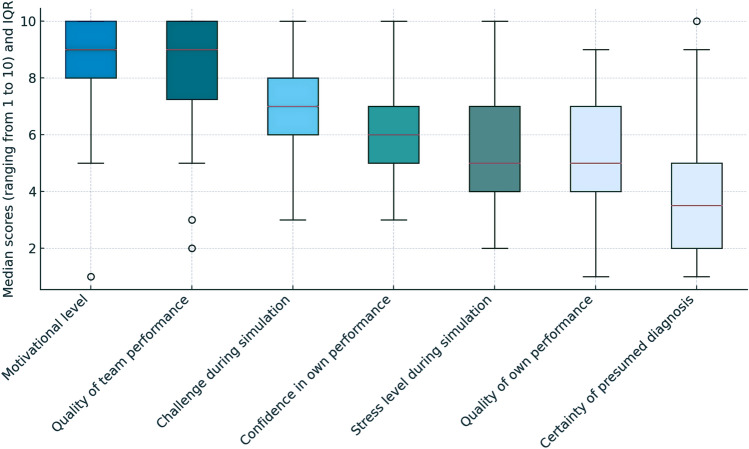

The results of the self-evaluation (Supplemental File 2) are presented in Fig. 3. While most physicians reported high motivation and rated the quality of team performance as high, their median self-assessment of personal challenge and confidence during the scenarios ranged from moderate to high. In contrast, the quality of their own performance and the perceived stress level were mostly rated as moderate. Furthermore, their confidence in the accuracy of their presumed diagnosis was reported as low to moderate.

Fig. 3.

Debriefing with self-evaluation of performance during simulation (secondary endpoints)*. IQR interquartile range. *Ranges for self-evaluation according to the emotional reflexivity questionnaire with “1” indicating “not at all” or “very uncertain” and “10” indicating “very much”, “excellent” or “very certain”

Discussion

This study examined how physicians from various specialties manage an adult patient with coma of unknown etiology in a highly standardized high-fidelity simulation, assessing adherence to recommended measures [3, 6] (primary endpoints), as well as the timing and execution of medical interventions, and post-simulation self-evaluation (secondary endpoints). The findings reveal significant variability in diagnostic and therapeutic practices and highlight important and critical gaps in adherence to recommended assessment bundles and treatment. Despite a 100% recognition of coma, only 40% of physicians quantified the level of consciousness accurately. Physicians completed the ABCDE bundle [7, 8] in only 20%. Crucial diagnostics, such as airway inspection, routine laboratory analyses, and advanced investigations, such as EEG, lumbar puncture, or extended toxicological screening, were frequently omitted. Treatment initiations varied markedly, with a concerningly high omission rate of essential steps. While oxygen was administered universally, airway protective measures, such as side-positioning or tracheal intubation, were notably infrequent, increasing the risk of aspiration and pneumonia, which can exacerbate systemic inflammation, worsen brain dysfunction [15], and prolong treatment and hospital stays [16].

Although our analyses revealed relatively consistent performance across specialties, acute care specialists conducted airway examinations more frequently than internal medicine physicians and neurologists. Internal medicine specialists were less likely to perform side-positioning but more often opted for tracheal intubation. This suggests specialty-specific variations that may reflect differences in training emphasis and clinical experience.

Conceptual gaps in understanding coma were evident, as nearly half of the participants provided incorrect coma definitions. Misconceptions about treatment were prevalent with over 20% mistakenly stating that all comatose patients require immediate intubation regardless of the underlying cause of coma. While participants rated their motivation and teamwork highly, confidence in their own diagnostic accuracy and performance was moderate, reflecting challenges of managing such complex scenarios—potential mediators for perceived stress and uncertainty as indicated by the physicians.

The inconsistent adherence to recommended assessments, particularly regarding airway assessment and management as well as full-body examination to detect injuries, aligns with previous simulation-based studies. A study evaluating lifeguards’ capacity to perform the ABCDE approach on a simulated drowned victim found that none of the participants performed complete clinical assessments [17]. Similarly, investigations in a simulated scenario of patients in status epilepticus revealed complete ABCDE assessment in only 5% [10, 12]. The absence of “head-to-toe” examinations in our scenario is another concern, given the likelihood of falls and injuries in unwitnessed coma cases, as noted in the simulated medical report. The mannequin’s design, however, may represent a bias, as it may have hindered such assessments. Nevertheless, these findings collectively highlight a pervasive challenge in the consistent application of systematic assessment protocols across various emergency situations, calling for more structured training and stronger emphasis of more systematic assessments and the implementation of guidelines.

This study further highlights the influence of prior simulator-based training, particularly in the areas of airway management and evaluating treatment responses with pre-trained physicians performing these steps more frequently. The limited number of participants with prior simulation training, however, calls for larger-scale research to fully understand its impact on performance. Nonetheless, our findings align with evidence that regular training in standardized emergency procedures improves outcomes and is a cornerstone of medical practice [18]. High-fidelity simulation has enabled clinicians across all experience levels to safely learn, refine, and repeatedly practice their skills without endangering patients or relying on high patient volumes. Therefore, training in simulated, high-pressure, time-sensitive neurologic emergencies, such as coma, may enhance the delivery of evidence-based care in real-world emergency settings.

Our previous findings in simulated scenarios of status epilepticus revealed significant differences among specific specialties [10, 12] motivated us to further investigate differences regarding coma assessment and management among different physicians’ specialties. This revealed very similar to our present study a less sufficient airway assessment and airway protective measures performed by internal medicine specialists and neurologists as compared to acute care specialists. We further enhanced our discussion by deducting that these observed disparities, especially regarding protective airway management indicate that implementing specialized training programs customized to distinct medical specialties may effectively mitigate these challenges. Furthermore, the findings underscore the potential benefit of supplementary interventions, such as instituting regular, standardized, and enhanced interdisciplinary debriefings following the management of coma patients. Such structured sessions would facilitate exposure to critical and constructive feedback, thereby fostering collaborative learning and knowledge exchange among physicians in daily clinical practice. The finding that physicians with prior simulation training performed side-positioning more frequently further underscores that more exposure to such scenarios may optimize clinicians performance and that less experienced physicians should have more interprofessional exchange, where they can profit and learn especially from more senior or experienced colleagues, an optimization that may be achieved through regular debriefing sessions that are still under established and rarely used in clinical practice [19].

The inverse relationship between affiliation to internal medicine or neurology and firm airway assessment/management warrants attention and emphasizes the need for stronger focus on this approach in guidelines. Despite coma of unknown etiology [5] and intoxication-related coma [20] is a common emergency faced by these specialists, no large studies have assessed the impact of simulation training on neurologists’ performance in managing coma. Simulation training for other neurological emergencies showed that participants found the scenarios realistic, reported improved medical knowledge, confidence in handling emergencies, and leadership skills [10, 12, 21–23]. The current simulator setup provides structured training and debriefing for managing coma of unknown etiology, aiming to establish a standard comparable to other advanced life support scenarios.

The inconsistent care of comatose patients with unknown causes reveals a critical need for standardized guidelines and training. To improve outcomes, structured training, interdisciplinary collaboration, and simulation-based education with feedback must be implemented. Future research should evaluate these interventions and refine protocols.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Its single-center design may restrict the generalizability of our findings. The simulation environment may also have limited external validity, necessitating confirmation of our findings in real-world clinical practice. Nonetheless, the fact that all participating physicians recognized patient unresponsiveness and that 94% attempted to quantify the level of consciousness suggests that the simulated scenario was realistic and effectively portrayed the intended neurological emergency. Moreover, several of our findings are consistent with those from clinical studies on neurological emergencies involving altered consciousness, such as epileptic seizures and status epilepticus, as previously investigated in simulation settings [10, 12]. In addition, high-fidelity simulation is widely employed as a training tool for advanced life support, providing effective learning opportunities for standardized and controlled clinical practice without posing risks to patients [24]. The inability to capture unspoken considerations of differential diagnoses, leaves it unclear whether certain diagnostic steps were omitted due to context-based exclusion of specific diagnoses. The fact that the video and audio material was reviewed by only two and not more reviewers represents another limitation, as well as the fact that both reviewers were not blinded to the participants clinical specialties which may be a source of bias. Finally, it is possible that some participants might have conducted additional examinations if the scenario would have been simulated for more than 20 min. However, we decided to use a 20 min time-window, as in an acute emergency, a delay in diagnosis over several minutes to hours can be critical and must be avoided.

Conclusions

This high-fidelity simulation study reveals significant gaps in managing adult patients with coma of unknown etiology, including inconsistent diagnostics, incomplete adherence to expert recommendations, and missed critical treatments. Specialty-specific differences and misconceptions highlight the need for standardized care through guidelines and enhanced training. High-fidelity simulation offers a platform to improve practice, confidence, teamwork, and leadership. Structured training, guideline adherence, and inter-specialty collaboration are essential to improve diagnostic accuracy, treatment consistency, and patient outcomes, while targeted education and further research can refine protocols and elevate emergency care quality.

Data availability statement

The corresponding author has access to all data. He takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis and interpretation, and the conduct of the research. The authors have the right to publish any and all data, separate and apart from the guidance of any sponsor.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental File 1: Variables which were a priori identified and systematically captured, based upon a review of the four references/guidelines. (PDF 38 KB)

Supplemental File 2: Questionnaire regarding the past scenario and emotional reflexivity questionnaire for subjective self-evaluation after completing the simulated clinical scenario. (PDF 28 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank all the staff of the medical intensive care unit and the simulator team Ms. Sabine Schweitzer and Mr. Marc Breuer for their most helpful support during the study. We thank all physicians of the University Hospital Basel for participating in this study. The corresponding author has full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author contributions

Liliane Nüesch and Raoul Sutter planned and designed the study, acquired, and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. Kai Tisljar, Sebastian Berger, Gian Marco De Marchis, Tolga D Dittrich, Stefano Bassetti, Roland Bingisser, Sabina Hunziker, and Stephan Marsch interpreted the data, revised the manuscript and substantially contributed to the inaugural draft. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel. The funder (University Hospital Basel) had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. This study was performed and designed without the input or support of any pharmaceutical company, or other commercial interest. Open access funding provided by University of Basel.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

L. Nüesch reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. K. Tisljar reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S. Berger reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. G.M. De Marchis was or is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation; Science Funds [Wissenschaftsfonds] of the University Hospital Basel and University of Basel; Bangerter-Rhyner-Stiftung; Swisslife Jubiläumsstiftung for Medical Research; Swiss Neurological Society; Fondazione Dr. Ettore Balli; De Quervain research grant; Thermo Fisher GmbH. He received travel honoraria by Bayer and speaker honoraria by Medtronic and BMS/Pfizer. T.D. Dittrich was or is supported by the Swiss Heart Foundation, the science funds of the University Hospital Basel, and the Research Fund for excellent young researchers of the University of Basel. He holds shares from Johnson & Johnson, Roche, Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Novo Nordisk. S. Bassetti reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. R. Bingisser is editor of medstandards.com, a symptom-based medical decision-support tool licensed to 150 European hospitals, owned by the University Hospital Basel. S. Hunziker is supported by the Swiss National Foundation (SNF) (Ref 10001C_192850/1 and 10531C_182422), the Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation (8472/HEG-DSV), and the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine (SSGIM). S. Marsch reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. R. Sutter received research grants from the Swiss National Foundation (No 320030_169379), the Research Fund of the University Basel, the Scientific Society Basel, and the Gottfried Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. He received personal grants from UCB-pharma and holds stocks from Alcon, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, and Roche.

Use of artificial intelligence-assisted technologies

The large language model (ChatGPT-4omni, OpenAI, San Francisco, USA) was used to paraphrase and summarize some of the manuscript’s content. After using this application, the authors further edited the content as needed and verified its accuracy.

Ethical Standard Statement

The study has been approved by the appropriate local ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All participants consented to participate in written form.

References

- 1.Schmidt WU, Ploner CJ, Lutz M, Mockel M, Lindner T, Braun M (2019) Causes of brain dysfunction in acute coma: a cohort study of 1027 patients in the emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 27:101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun M, Schmidt WU, Mockel M, Romer M, Ploner CJ, Lindner T (2016) Coma of unknown origin in the emergency department: implementation of an in-house management routine. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 24:61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Traub SJ, Wijdicks EF (2016) Initial diagnosis and management of coma. Emerg Med Clin N Am 34:777–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Posner JB, Plum F, Saper CB (2007) Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volk S, Koedel U, Pfister HW, Schwankhart R, Op den Winkel M, Muhlbauer K, Klein M (2018) Impaired consciousness in the emergency department. Eur Neurol 80:179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edlow JA, Rabinstein A, Traub SJ, Wijdicks EF (2014) Diagnosis of reversible causes of coma. Lancet 384:2064–2076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soar J, Nolan JP, Bottiger BW, Perkins GD, Lott C, Carli P, Pellis T, Sandroni C, Skrifvars MB, Smith GB, Sunde K, Deakin CD, Adult Advanced Life Support Section C (2015) European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 3. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 95:100–147 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Truhlar A, Deakin CD, Soar J, Khalifa GE, Alfonzo A, Bierens JJ, Brattebo G, Brugger H, Dunning J, Hunyadi-Anticevic S, Koster RW, Lockey DJ, Lott C, Paal P, Perkins GD, Sandroni C, Thies KC, Zideman DA, Nolan JP, Cardiac Arrest in Special Circumstances Section C (2015) European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation 95:148–201 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Cheng A, Kessler D, Mackinnon R, Chang TP, Nadkarni VM, Hunt EA, Duval-Arnould J, Lin Y, Cook DA, Pusic M, Hui J, Moher D, Egger M, Auerbach M, International Network for Simulation-Based Pediatric Innovation R, Education Reporting Guidelines I (2016) Reporting guidelines for health care simulation research: extensions to the CONSORT and STROBE statements. Simul Healthc 11:238–248 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sutter R, Tisljar K, Opic P, De Marchis GM, Bassetti S, Bingisser R, Hunziker S, Marsch S (2019) Emergency management of status epilepticus in a high-fidelity simulation: a prospective study. Neurology 93:838–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tramer L, Becker C, Hochstrasser S, Marsch S, Hunziker S (2018) Association of electrocardiogram alterations of rescuers and performance during a simulated cardiac arrest: a prospective simulation study. PLoS ONE 13:e0198661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kliem PSC, Tisljar K, Baumann SM, Grzonka P, De Marchis GM, Bassetti S, Bingisser R, Hunziker S, Marsch S, Sutter R (2022) First-response ABCDE management of status epilepticus: a prospective high-fidelity simulation study. J Clin Med 11(2):435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraut JA, Kurtz I (2008) Toxic alcohol ingestions: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3:208–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill CE, Parikh AO, Ellis C, Myers JS, Litt B (2017) Timing is everything: where status epilepticus treatment fails. Ann Neurol 82:155–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Q, Yao C, Wu Y, Wang H, Fan Q, Yang Q, Xu J, Dai H, Zhang Y, Xu F, Lu T, Dowling JK, Wang C (2023) Neurological disorders after severe pneumonia are associated with translocation of endogenous bacteria from the lung to the brain. Sci Adv 9:eadi0699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellaviti G, Balsamo F, Iosa M, Vella D, Pistarini C (2021) Influence of systemic infection and comorbidities on rehabilitation outcomes in severe acquired brain injury. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 57:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez-Mendez F, Otero-Agra M, Abelairas-Gomez C, Saez-Gallego NM, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Barcala-Furelos R (2019) ABCDE approach to victims by lifeguards: how do they manage a critical patient? A cross sectional simulation study. PLoS ONE 14:e0212080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruesseler M, Weinlich M, Muller MP, Byhahn C, Marzi I, Walcher F (2010) Simulation training improves ability to manage medical emergencies. Emerg Med J 27:734–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imperio M, Ireland K, Xu Y, Esteitie R, Tan LD, Alismail A (2024) Clinical team debriefing post-critical events: perceptions, benefits, and barriers among learners. Front Med (Lausanne) 11:1406988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsberg S, Hojer J, Enander C, Ludwigs U (2009) Coma and impaired consciousness in the emergency room: characteristics of poisoning versus other causes. Emerg Med J 26:100–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braksick SA, Kashani K, Hocker S (2017) Neurology education for critical care fellows using high-fidelity simulation. Neurocrit Care 26:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ermak DM, Bower DW, Wood J, Sinz EH, Kothari MJ (2013) Incorporating simulation technology into a neurology clerkship. J Am Osteopath Assoc 113:628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller JM, Steinbach TC, Adamson R, Carlbom DJ, Johnson NJ, Clark J, Kritek PA, Coruh B (2019) ICU emergencies simulation curriculum for critical care fellows: neurologic emergencies. MedEdPORTAL 15:10813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perkins GD (2007) Simulation in resuscitation training. Resuscitation 73:202–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teasdale G, Jennett B (1974) Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 2:81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones C (1979) Glasgow coma scale. Am J Nurs 79:1551–1553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental File 1: Variables which were a priori identified and systematically captured, based upon a review of the four references/guidelines. (PDF 38 KB)

Supplemental File 2: Questionnaire regarding the past scenario and emotional reflexivity questionnaire for subjective self-evaluation after completing the simulated clinical scenario. (PDF 28 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author has access to all data. He takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis and interpretation, and the conduct of the research. The authors have the right to publish any and all data, separate and apart from the guidance of any sponsor.