ABSTRACT

Social media platforms today are teeming with images of wildlife as pets, and studies have emerged investigating the role social media plays on the public's perception of primates and their desirability as pets. This study explores the presentation of nonhuman primates and video engagement, defined as user interactions through likes, comments, shares, and views, on the social media platform TikTok. We examined 1378 videos from 173 different TikTok content creators sharing primate videos. Most content depicted primates within a household (43.1%), indicating they are often shown in the context of being pets. This is cause for concern because the portrayal of primates in anthropogenic settings or in contact with humans makes them more desirable as pets to viewers. We also found significant differences in engagement rate based on the location of the video and the species of primate present. Households, zoos, sanctuaries, and wild settings received higher levels of user engagement than other captive or exploitative settings. Smaller primates, mostly platyrrhines, were also found to be more engaging than other species. When variables were clustered using a Multiple Correspondence Analysis, we compared the newly created dimensions against engagement rates using a correlation matrix. We found weak, but significant correlations, with themes representing higher human or anthropomorphic influence receiving better engagement. Because social media can be a source of powerful influence on viewers, rampant presentation of primates as pets or in anthropogenic settings is concerning from a conservation and welfare perspective. However, content from zoos, sanctuaries, and field researchers with imagery representing primates in accredited captivity or in their natural habitats could potentially discourage audiences from regarding primates as making appropriate pets. In turn, this could establish a pathway for TikTok to pivot from being a threat to becoming a tool in primate conservation.

Keywords: #primatesnotpets, pet primates, primate conservation, primate content, social media, TikTok

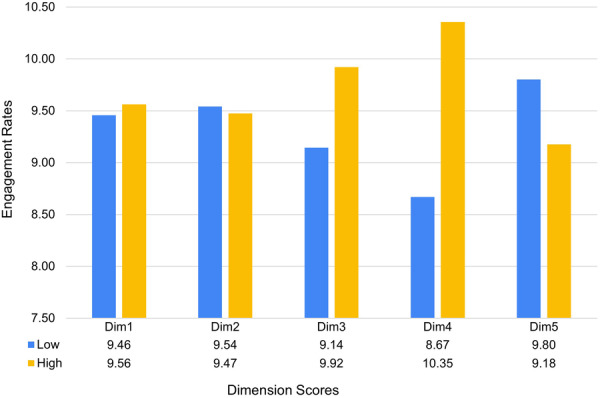

Comparison of the average engagement rate across the two levels of each dimension. These averages offer a complementary view of how video performance may differ across the ends of each thematic dimension. Dimension 1 is the level of human interaction. Dimension 2 is the level of anthropomorphized environment. Dimension 3 is the level of captive context. Dimension 4 is the level of primate exploitation. Dimension 5 is the level of commercial representation.

Summary

In this study, we reviewed primate content on TikTok to evaluate the depictions of primates and determine which depictions garnered higher levels of engagement.

Nearly half of videos analyzed were in a household context exhibiting primates as pets. The remaining videos depicted primates within wild or accredited captive settings. A Multiple Correspondence Analysis determined that the themes of human interaction, anthropomorphized primates, and the commodification of primates had positive correlations with video engagement rates. Engagement rates driven by individual elements of a video indicate a place for more appropriate presentations of primates on TikTok.

We add to a growing body of literature that supports the imagery guidelines set forth by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and argue that more welfare‐centered and naturalistic presentations of primates are necessary. Understanding what drives engagement allows professionals to create ethical, conservation‐focused videos that counteract pet primate content. Importantly, higher follower counts do not guarantee greater engagement; even smaller platforms and followings can share impactful content that supports primate welfare and conservation.

1. Introduction

Historically, animals have been exploited for the purpose of human amusement and entertainment, encompassing multiple contexts and activities (Brando 2016; Fennell and Coose 2022; MacKinnon 2006; Shelton 2014). As digital technology has rapidly advanced, so too have the ways the public consumes and engages with animals across the globe. Within the last century, animals, particularly nonhuman primates (hereafter primates), have been primarily used as “actors” in film, television, and commercials (Aldrich 2018; Aldrich et al. 2023; Riley Koenig et al. 2019; Schroepfer et al. 2011). Today, social media has created a new avenue for the public to participate in such exploitation by making “entertaining” content not only more readily available but easy to create, share, and interact with. These platforms increasingly commodify nature, fueling the illegal trade of exotic animals (Harrington et al. 2019; Herzog 2006; Kitson and Nekaris 2017; Nijman et al. 2022; Nijman et al. 2021) and the popularity of nature‐based tourism (Hausmann et al. 2017; Lenzi et al. 2020; Pagel et al. 2020; von Essen et al. 2020).

Globally, there are more than 5 billion users of social media in 2025, approximately 64% of the world's population (Statista 2025). YouTube and Facebook remain the most widely used platforms among most demographic groups (83% and 68% of adults over 18 years old, respectively), with other platforms capturing smaller niche shares of the attention market (Gottfried 2024). As new platforms emerge and gain rapid popularity, it is increasingly important to understand how these niche user demographics engage with animal content.

In 2016, TikTok was launched as a short‐form video‐based social media platform that has found popularity across multiple age demographics (Auxier and Anderson 2021), particularly younger users, and carries the self‐purported mission “to inspire creativity and bring joy” (TikTok 2024a). The platform's For You Page (henceforth, FYP) uses a large‐scale artificial intelligence model to create a continuous scroll of content based on the user's engagement history, including content from accounts they follow, from their friends, and from friends of friends (Rodela 2023; Cervi 2021; TikTok 2020). In addition to a user's FYP, they also have access to their “Following” page, which contains the accounts that the user has specifically followed. This extended social network and a constantly updated FYP can enable videos (including animal videos) to go “viral,” that is, to gain popularity in a short amount of time across the platform or other platforms (via cross‐platform posting).

Although social media can be a valuable tool for positive conservation messaging (Bergman et al. 2022; Freund et al. 2021; Lenzi et al. 2020; Twining‐Ward et al. 2022), it also creates opportunities for miscommunication, misinformation, and illegal activity. Researchers are raising urgent concerns about the burgeoning negative impacts of animal content on social media, not only on human well‐being (Baccarella et al. 2018) but also human–animal relationships (Feddema et al. 2021). Like its predecessors in the social media industry, TikTok hosts many depictions of wild and exotic animals as pets, including primates. Unique from its competitors, who have remained relatively flat in terms of user growth, TikTok has seen 12% user growth among American adults since 2021; 33% of American adults state they now use the platform (Gottfried 2024). TikTok's content moderation around animal abuse states that it does not allow depictions of “abuse [real or staged], cruelty, neglect, trade [whole or parts], or other forms of animal exploitation” (TikTok 2024b). However, the unfettered proliferation of the platform's video content paired with ambiguous community guidelines and lack of legislative regulation of social media, has generated concerns about user safety, content moderation, and the ability to enforce consequences on users for violations of platform policies.

The visual context and content of social media posts strongly influence user perceptions of and attitudes toward animals, including primates (Leighty et al. 2015; Lenzi et al. 2020; Moloney et al. 2021; Nekaris et al. 2016; Quarles et al. 2023; Riddle and MacKay 2020). The appearance of primates in photos and videos is prolific across Facebook, Instagram, Twitter (now branded X), and YouTube, and although some of the primates found on these platforms are shown in their natural habitats, many are depicted in entertainment settings or as pets (Lenzi et al. 2020). For example, the repeated use of primates and other charismatic species in celebrity culture (Spee et al. 2019) or branding and advertisements can result in erroneous perceptions about endangerment, population health, or conservation issues (Courchamp et al. 2018; Schroepfer et al. 2011). When primates and humans are shown together in photos and videos, they are perceived as desirable pets (Ross et al. 2011), as being less dangerous or tamer (Leighty et al. 2015; Pagel et al. 2020), and poor welfare or the presence of stereotypical behaviors are often misconstrued and considered “cute” (Nekaris et al. 2016). The drive for views and follower engagement on social media posts can serve to normalize inappropriate human–wildlife interactions and the presence of stereotypical behaviors, while overall encouraging more shocking and attention‐grabbing content to garner views (Harrington et al. 2023; Nekaris et al. 2016; Nunes et al. 2023). Even institutions driven by conservation and educational missions can become increasingly focused on producing entertaining content with charismatic animals because it performs well with viewers (Llewellyn and Rose 2021).

Wanting an exotic pet is not necessarily tied to how that animal is portrayed visually, but also a generational desire (Cronin et al. 2022). In Cronin's (2022) findings, generations like Gen Z, Millennials, and Gen X, stated interest in wanting a wild animal as a pet (a sloth or python in this particular case), regardless of the context and caption of the photo. This sentiment is alarming, especially in light of TikTok user demographics. Compared to other social media platforms, most TikTok users (70%) are between the ages 18–49, with Gen Z (18–29 years old) comprising nearly half of users (Auxier and Anderson 2021). The contribution of TikTok to the exotic pet conversation is compounded by this generational effect and the fact that the platform visually perpetuates the idea that primates are appropriate pets. Therefore, TikTok may be playing an outsized role in exposing younger generations to inappropriate portrayals of primates, that is, as pets, in entertainment, and potentially the exotic pet trade, which could increase threats faced by primates both in captivity and the wild.

In this study, we analyzed primate‐specific content on TikTok to explore the various ways primates are depicted, how users interact with these posts, and to assess overall video engagement using platform metrics. By broadly characterizing the types of primate‐based content on TikTok and evaluating its performance with viewers, we aim to better understand the trends and demand for primate‐related content on social media. The prevalence and context of certain types of primate videos may also reveal the broader impact that TikTok and other social media platforms have on wildlife trade. Trending videos can potentially inspire viewers to want a pet primate, reinforcing the false notion that concerning content, as identified by experts, is harmless—thereby undermining ongoing conservation efforts (Nekaris et al. 2013; Ross et al. 2011).

2. Methods

This study complied with Central Washington University's Human Subjects Review Council (#2021‐109), adhered to the American Society of Primatologists (ASP) Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Non‐Human Primates, followed the ASP Code of Best Practices for Field Primatology, and adhered to the legal requirements of the United States where the research was conducted. Additionally, the authors state there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

2.1. Data Collection

We collected data from January to May 2021 from primate videos found on TikTok. We searched for videos using a combination of specific hashtags, which are words or phrases used to organize searches, draw attention to a theme, and/or to engage in online conversation. The original search hashtags used during coding were #primate, #monkey, #ape, #exoticpet, #petmonkey, #monkeysoftiktok, and #apesoftiktok. The hashtags were used in any combination; a coder could use one, some, or all of the original hashtags to search for videos. Eventually, the original hashtags failed to yield new videos, so we expanded our list of search terms based on common hashtags we saw during the coding of previous videos. These additional hashtags were: #cutemonkey, #lemur, and #chimp. We also found searching #monkeys prompted additional search results compared to #monkey. Once a video was selected, we coded up to 10 of the most recent videos that displayed a primate per that creator's account. This often included the same primate but helped to ensure our sample included a variety of possible primate depictions from the same creator.

To determine who is posting primate content and the performance of a video, we collected the following 11 metrics for each account and video: (1) the hashtags used as search terms by the coder to find the video on TikTok; (2) the account username (hereafter content creator or creator); (3) whether the account was “verified”; (4) the creator's total number of followers; (5) the video URL; (6) the date the video was posted; (7) the hashtags used on the video by the creator; (8) the number of views of the video; (9) the number of likes on the video; (10) the number of comments on the video; and (11) the number of shares of the video.

The venues for primate exploitation have varied, including ceremonies, sports, fairs, circuses, menageries, and ecotourism settings (Agoramoorthy and Hsu 2005; Aldrich et al. 2023; Sehl & Barboza, 2018; Brando 2016; Fennel & Coose 2022; Shelton 2014; Sterckx 2012; Yates 2009). Preliminary analysis also revealed content featuring primates in novel settings, like riding in cars or visiting pet supply stores. To capture what may be prevalent across TikTok, we recorded multiple setting types. We examined the content of each video and coded the following 12 variables: (1) the primate genus or species shown; (2) the assumed location/setting of the video (see Table 1); (3) whether the video advertised or contained information regarding the sale of the primate; (4) the presence of humans; (5) the presence of a barrier between the primate and any humans; (6) whether human–alloprimate contact occurred; (7) whether humans in the video were wearing personal protective equipment (PPE); (8) the presence of food; (9) the presence of human artifacts (e.g., blankets, toys; see Supporting Information S1: Table S1); (10) the presence of human clothing on the primate; (11) the presence of other animals; and (12) the presence of restraints. When coding for a variable, if we were unable to determine the code or were unsure, that variable was coded as “Unknown” or “Not Visible.” For example, if we were unable to discern the location of the video or know if the primate was wearing clothing, it was marked as “Unknown.” These cases were then excluded from further analyses.

Table 1.

Location variable definitions.

| Location | Description |

|---|---|

| Captivity—sanctuary | An accredited facility; confirmed by additional information on account (e.g., caption, comments, a well‐known/established facility). |

| Captivity—zoo | An accredited facility where animals are housed for exhibition; confirmed by additional information on the account (e.g., caption, comments, a well‐known/established facility). |

| Captivity—entertainment | Exotic wildlife park; implies no oversight by an accredited institution (e.g., AZA, EAZA, WAZA, GFAS, etc). |

| Captivity—unknown | Unable to discern the type of captive environment. |

| Household | Within a place of residence or yard; context is primate is being kept as a pet. |

| Business | Within or outside a store or business location, considered to be in a customer‐based environment. |

| Vehicle | Video takes place entirely in a vehicle; vehicle can be parked or in motion. |

| Event | Primate attending an event (e.g., a sporting event, concert, county fair, etc.) as a bystander. |

| Performance | Primate is on a film set or stage and is being asked/told to complete a task, performing tricks for an audience present. |

| Medical/veterinary | Field work procedures or veterinary office by an assumed medical professional. |

| School | A K‐12 or university educational setting. |

| Wild | Primate in their perceived natural habitat. |

| Other | Any location not previously described. |

| Unknown | Cannot be determined from the context of the video. |

2.2. Data Analysis

Data were collected, organized, and stored in Microsoft Excel (vers. 16.72). All statistical analyses were performed in Jamovi (vers. 2.6.22) using the supporting Rj editor and multivariate exploratory data analysis modules (Leblay et al. n.d.; Love & Agosti n.d). Multiple coders worked on this project at different stages, so we completed two rounds of interobserver reliability (IOR). In the first round, 10 coders assessed the same 10 randomly chosen videos and coded all 12 variables. This initial round of IOR resulted in 85%–95% agreement between coders across the variables (Cronbach's α = 0.996). We then discussed coding discrepancies and conducted a second round of IOR. In this second round, nine coders assessed three videos and coded 12 variables. Reliability scores improved to 94%–100% agreement between coders across the variables (α = 0.995). To assess the distribution of our data and test for normality, we performed a Shapiro–Wilk test and a visual inspection of the distribution of the data using Q–Q plots. Non‐normality was assumed (p < 0.05), and nonparametric tests were used where appropriate.

TikTok metrics (i.e., the number of followers, likes, comments, shares, and views) are reported as the median with interquartile ranges (IQR) due to large ranges and to minimize the influence of outliers. Considering the snapshot nature of the TikTok platform, any missing metric information from the data set could not be collected post hoc. For instance, three samples did not report the number of views or shares. However, those samples were kept because other metrics were recorded, and the change in n is reported throughout the results where appropriate. When possible, all large numbers follow the notation common to social media platforms (e.g., thousand = K and million = M).

TikTok users have two sources of video content: their “Following” page and their “FYP”; therefore, it is possible for users to see videos from both accounts they follow and those they do not. Meaning, followers may not always guarantee views. To understand the relationship between TikTok metrics to analyze video engagement, we performed a linear regression. Before conducting the regression analysis, the assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity were examined. Initially, these assumptions were not met, and we performed a Log10 transformation on the number of followers, views, likes, comments, and shares. Both residual versus fitted and Q–Q plots indicated homoscedasticity and normal distributions, respectively. The variance inflation factor (VIF) value and Durbin–Watson statistic suggested no multicollinearity or autocorrelation, respectively. We conducted a linear regression to examine whether the number of followers predicted the number of views, likes, comments, and shares a video received. The overall results were significant, suggesting that the number of followers had a significant effect on video interactions. However, when we examined whether the number of views predicted the number of likes, comments, and shares, the results indicated that this metric was a stronger predictor of video interactions (Supporting Information S1: Table S2).

A standard measurement for performance of a video online is its engagement rate (Sehl and Tien 2023), although there are several ways to calculate engagement depending on how one is evaluating post performance. We were interested in the level of engagement the video received and, based on the results of the linear regression, determined engagement by view to suit our needs. To calculate engagement rate by view, we used the following equation: (number of likes + number of comments + number of shares)/(number of views)*100. We calculated engagement rates for each video, excluding six videos with one or more missing metrics. It has been reported that AI bots can like a video without it counting as a view on that video, thus artificially inflating video metrics. The metrics and views on another six videos held the same value, that is, the number of views = the number of likes. Due to either a date entry error or inflated metrics via bot, we filtered out videos with an engagement rate > 100. When appropriate, we ran post hoc Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner (DSCF) pairwise comparisons to test the differences in medians for location, human contact, and species.

We performed Kruskal–Wallis tests to evaluate the relationship between TikTok engagement rates, the types of interactions (e.g., the number of likes or comments received on a video), and the video content variables, while also deciding to focus on video location, species, and human presence and contact. We defined engagement by the number of views, likes, comments, or shares that the video had at the time the data was collected. Given that previous research (Ross et al. 2011) has shown that the presence of humans influences the perception of primates, we focused our analytical approach on human contact. We performed a Mann–Whitney U‐test to evaluate engagement rates and the presence of human contact. We also performed a chi‐square test of independence to determine the relationship between certain locations and the likelihood of human contact. For all tests, we set significance at p < 0.05.

Finally, we also considered the potential for specific video variables to interrelate (e.g., human contact is more likely in households than zoos, some species are more prevalent as pets given their size and accessibility). For that reason, we conducted a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) to examine the relationships between the video content variables simultaneously. We included all 12 categorical variables as active variables, using a broader taxonomic grouping (i.e., ape, cercopithecid, platyrrhine, and strepsirrhine) instead of more narrow genus and species, and grouped our Locations to reflect our earlier consolidation of locations that represented less than 1% of the data set. To see how these variables interacted with engagement rate, we included engagement rate as the quantitative supplementary variable. Quantitative variables in an MCA do not directly influence the analysis itself, rather they are used to assist in the interpretation of the categorical variables through their direction and position on the factorial map. We set the ventilation level at 5% and maintained the category selection at cos² ≥ 0.10. We changed the default number of dimensions from two to five, as these additional dimensions helped explain more of the inertia observed in the data set. Using the dimension scores, we ran a correlation analysis examining the influence of dimensionality on engagement rates.

3. Results

3.1. Video Descriptives and Content

We examined a total of 1378 videos from 173 different TikTok creator accounts. Of these, only 17 (9.8%) were verified accounts. Four videos were deleted from our sample due to a missing URL, as we no longer had a record of that video to reference on TikTok if needed. The median number of followers on an account was 68.3 K (IQR 546,069) and ranged from 4 to 31.8 M followers. The median number of days since a video was posted was 93.5 (IQR 230). The median number of views (n = 1375) on a video was 10.9 K (IQR 76,596) and ranged from 5 to 150.3 M views. The median number of hashtags included on a video was 6.0 (IQR 7) ranging from 0 to 30. The median number of likes on a video was 755 (IQR 5062) but ranged from 0 to 9.5 M. The median number of comments was 16 (IQR 63.8) ranging from 0 to 142.9 K. The median number of shares (n = 1375) was 14 (IQR 109) ranging from 0 to 917.6 K (Supporting Information S1: Table S3).

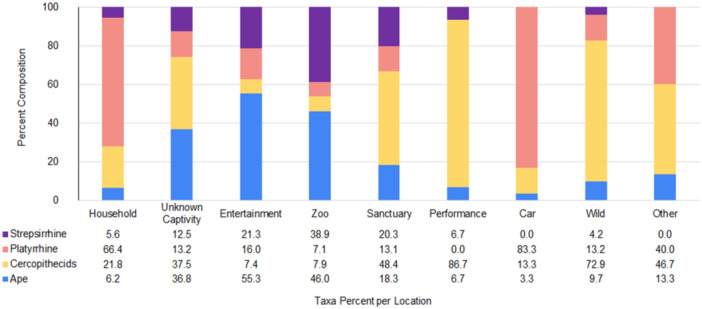

Video location was identifiable in 1317 videos. Wild depictions of primates only accounted for 11% of the videos coded (n = 145). Most frequently, videos displayed primates housed in some form of captivity, namely within a human household (n = 599, 45.5%), sanctuary (n = 155, 11.8%), an ambiguous unknown captive setting (n = 138, 10.5%), or zoo (n = 126, 9.6%). Locations that contributed to less than 1% of videos (“Business,” “Medical/Veterinary,” and “Event”) were reclassified as “Other” for further analyses. Primates were shown manipulating food, eating, or being fed in one‐third of the videos posted (33%, n = 451). When the food item was identifiable, we found both natural diet, that is, food items characteristic of a species‐specific diet, (70%, n = 285) and human food items (30%, n = 122) being consumed (unknown food items, 3.2%, n = 44). See Supporting Information S1: Table S4 for a full description of food items. Primates appeared wearing human clothing in approximately one‐third of videos (32.5%, n = 444) and were frequently engaging with human artifacts, including children's toys and enrichment (62.5%, n = 861). Although other animals also occasionally appeared in videos (e.g., dogs, big cats, birds, etc.), primates were more frequently the focus of most videos (88.0%, n = 1213).

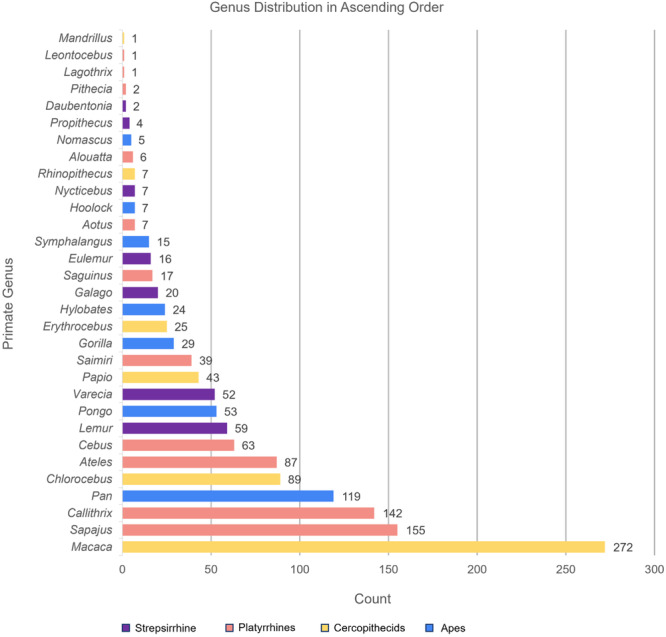

Overall, monkeys were the subjects of most videos (platyrrhines, 37.9%, n = 522; cercopithecids, 31.7%, n = 437; apes, 18.6%, n = 256; strepsirrhines, 11.8%, n = 163). When assessed by genus (n = 1369), Macaca (19.9%), Sapajus (11.3%), Callithrix (10.4%), and Pan (8.7%) accounted for 50.2% of all videos (Figure 1). When assessed by common name (n = 1378), macaques (19.7%), capuchins (15.9%), marmosets (10.2%), and lemurs (9.9%) accounted for 55.7% of all videos.

Figure 1.

Frequencies of primate genera present in TikTok videos.

We found that platyrrhines were most frequently depicted as household pets (Figure 2). The majority of platyrrhines recorded in households were capuchins (30%, n = 179), marmosets (17%, n = 103), spider monkeys (11.5%, n = 69), and squirrel monkeys (4.8%, n = 29). This was followed by cercopithecids—macaques (10.7%, n = 64), vervet/green monkeys (7.5%, n = 45), and patas monkeys (3.2%, n = 19)—and chimpanzees (4.5%, n = 27) and galagos (2.3%, n = 14) as the most common of the apes and strepsirrhines, respectively. Within videos filmed in zoos and sanctuaries, lemurs (30.2%, n = 85), vervet/green monkeys (12.5%, n = 35), orangutans (11.7%, n = 33), baboons (9.6%, n = 27), macaques (7.8%, n = 22), chimpanzees (7.5%, n = 21), and gorillas (6.4%, n = 18) were the most common species. In wild settings, macaques (66.2%, n = 96) and capuchins (7.6%, n = 11) were predominant. Chimpanzees were common among most captive settings—including households, entertainment, zoos, and sanctuaries—but were only recorded in the wild in two videos. Macaques were common in both captive and wild settings and were one of the only species recorded in a performance setting.

Figure 2.

Primate species by video location.

Humans frequently appeared within the video frame (57.7%, n = 795) and were often shown in direct contact with the primate (85.3%, n = 677). When this was the case, the humans present were not wearing PPE (93.6%, n = 634), and there was unlikely to be a barrier between them and the alloprimate (89.4%, n = 711). Overall, visible barriers between the primate and the person filming were only observable in 12.7% (n = 175) of posted videos, and primates were also unlikely to be restrained (91.7%, n = 1263). Most videos did not explicitly state that the primate was for sale or trade (96.9%, n = 1328). However, 3.1% of videos that listed the primate for sale or trade were most frequently selling platyrrhines (83.3%, n = 35). In fact, 80% of the primates for sale were marmosets or capuchins. In this study sample, apes were never indicated as being for sale (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primates indicated for sale on TikTok.

| Genus (common name) | n |

|---|---|

| Callithrix (common marmosets) | 14 |

| Sapajus (tufted capuchins) | 11 |

| Cebus (gracile capuchins) | 3 |

| Galago (bushbabies) | 3 |

| Saimiri (squirrel monkeys) | 3 |

| Ateles (spider monkeys) | 2 |

| Chlorocebus (grivet, vervet, and green monkeys) | 2 |

| Saguinus (tamarins) | 2 |

| Papio (baboons) | 1 |

3.2. Engagement Metrics

Investigating engagement metrics, we found significant differences in engagement across taxonomic groups (χ 2 = 53.7; df = 3; p < 0.001; ε 2 = 0.0393). Post hoc DCSF pairwise comparisons revealed that platyrrhines and strepsirrhines received significantly higher engagement than apes and cercopithecoids (Table 3). For further breakdown of the engagement rates across taxa, see Supporting Information S1: Table S5.

Table 3.

Significant engagement rate by taxonomic group.

| Group A | Group B | Mdn A | Mdn B | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ape | Platyrrhines | 7.22 | 8.97 | 5.75 | < 0.001 |

| Ape | Strepsirrhines | 7.22 | 10.2 | 6.03 | < 0.001 |

| Cercopithecids | Platyrrhines | 7.33 | 8.97 | 8.38 | < 0.001 |

| Cercopithecids | Strepsirrhines | 7.33 | 10.2 | 7.67 | < 0.001 |

In general, video location differed significantly in the number of views (χ 2 = 103.7; df = 10; p < 0.001; ε 2 = 0.079), likes (χ 2 = 94.4; df = 10; p < 0.001; ε 2 = 0.072), shares (χ 2 = 98.9; df = 10; p < 0.001; ε 2 = 0.075), and comments (χ 2 = 72.8; df = 10; p < 0.001; ε 2 = 0.055). Engagement rate by video location was also significant (χ 2 = 52.8; df = 8; p < 0.001; ε 2 = 0.043). Videos filmed in zoos and vehicles had the highest engagement rates (8.8% and 9.1%, respectively), whereas performance settings had low engagement (4.7%, Table 4). Post hoc DSCF pairwise comparisons determined that videos located in both households and zoos had higher engagement than those in captive entertainment, performance, or wild settings (Table 5; Supporting Information S1: Table S6).

Table 4.

Median engagement rate for video locations and human contact.

| Location | N | Mdn Engagement Rate (MER) | Human Contact | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N) | MER | No (N) | MER | |||

| Household | 566 | 8.59 | 332 | 8.98 | 234 | 8.26 |

| Sanctuary | 139 | 7.50 | 60 | 8.63 | 79 | 7.26 |

| Wild | 136 | 6.46 | 37 | 6.80 | 98 | 6.24 |

| Unknown captivity | 122 | 7.41 | 45 | 7.43 | 77 | 7.38 |

| Zoo | 120 | 8.78 | 29 | 9.75 | 91 | 8.54 |

| Entertainment | 93 | 6.36 | 63 | 6.30 | 29 | 7.50 |

| Vehicle | 28 | 9.07 | 21 | 9.03 | 7 | 12.2 |

| Performance | 14 | 4.73 | 6 | 4.50 | 8 | 6.11 |

| Other | 13 | 6.99 | 11 | 6.99 | 2 | 8.73 |

Note: Location N excludes locations with engagement rates over 100.

Table 5.

Significant pairwise results for engagement rates by video location.

| Location A | Location B | Mdn A | Mdn B | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household | Entertainment | 8.59 | 6.36 | −6.661 | < 0.001 |

| Household | Wild | 8.59 | 6.46 | −7.324 | < 0.001 |

| Household | Performance | 8.59 | 4.73 | −4.429 | 0.046 |

| Zoo | Entertainment | 8.78 | 6.36 | 5.066 | 0.003 |

| Sanctuary | Entertainment | 7.50 | 6.36 | 3.584 | 0.020 |

| Zoo | Wild | 8.78 | 6.46 | −4.885 | 0.016 |

Videos with a human present (57.7%, n = 795) received more engagement (Supporting Information S1: Table S7), but did not receive a higher engagement rate overall than videos without a human present (U = 191106; p = 0.090; r = 0.055). However, the presence of human–alloprimate contact increased engagement rate (U = 192410; p = 0.032; r = 0.07; Table 4), with those videos showing human–alloprimate contact receiving significantly more views (U = 177604; p < 0.001; r = 0.14), likes (U = 174497; p < 0.001; r = 0.16), shares (U = 187944; p = 0.005; r = 0.09), and comments (U = 168120; p < 0.001; r = 0.19) than videos without human–alloprimate contact. We used a chi‐square test of independence to examine the relationship between video location and presence of human–alloprimate contact, and this was significant (χ² = 126, df = 8, p < 0.001). Videos of primates in households, captive entertainment, and cars were more likely to show human–alloprimate contact. The inverse was true for zoos and wild settings.

3.3. Relationship Between Video Content Variables

An MCA was conducted to explore the relationships between the 12 categorical variables. The analysis indicated that the first five dimensions explained approximately 38% of the inertia. The most significant dimension, Dimension 1, captured the level of human–alloprimate interaction and differentiated between highly interactive (e.g., human contact, no barriers) and less interactive spaces (e.g., primates in natural settings, no human contact). Dimension 2 highlighted the differences between highly structured environments (zoos, sanctuaries) and more informal, unstructured settings (households, the wild). Dimension 3 reflected the species featured and the environment in which they were filmed, distinguishing between different taxa and their settings (wild vs. captive). Dimension 4 captured whether primates were depicted in commodified or captive contexts, including the presence of trade/for sale indicators and restraints. Dimension 5 represented the commercial aspect of primate videos, distinguishing between those with clear signs of human influence (artifacts present, listed for sale) and those without. Table 6 provides a list of dimensions and their scoring factors.

Table 6.

Dimension descriptions from the multiple correspondence analysis.

| Dimension | Theme | Low score | High score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dim. 1 | Human interaction | No humans, no contact, PPE worn, and barriers present | Humans present, direct contact, no PPE, and no barriers |

| Dim. 2 | Anthropomorphized environment | Wild settings, natural environments, no clothing, and no artifacts | Structured environments, clothing present, and human artifacts |

| Dim. 3 | Captive context | Wild settings, no barriers, and most high strepsirrhine presence | Captivity, high platyrrhine presence, barriers, and human artifacts |

| Dim. 4 | Primate exploitation | Not for sale, no restraints, no human‐provided food, and no other animals present | Trade/sale, primates restrained, fed human food, and other animal species present |

| Dim. 5 | Commercial representation | No artifacts, no clothing, and wild/sanctuary setting | Highly staged, human artifacts, clothing, and trade/sale indicators |

Note: While Dimensions 2 and 3 are similar, Dimension 2 focuses on how much a setting is influenced by humans, and Dimension 3 focuses on whether a primate is fully wild or captive and relates directly to species type. Similarly, Dimensions 4 and 5 both indicated primates as being for sale. Dimension 4 focused on how the primate was treated and used, whereas Dimension 5 focused on how humans incorporated various humanized elements, such as artifacts, props, and clothing, to alter the video's presentation of the primate.

Using the dimension themes provided by the MCA results, we performed a correlation analysis to inspect the relationship between engagement rate and the dimension scores (Table 7). Dimension 1 scores and engagement rate were weakly and negatively correlated, (ρ = −0.067, p = 0.012), indicating that higher engagement aligned with problematic portrayals of primates, meaning content containing high levels of human interaction and within household settings. Dimension 2 scores and engagement rate were not significantly correlated, (ρ = −0.002, p = 0.955), indicating no strong link between structured (zoos, sanctuaries) and unstructured (households) captive settings and engagement rate. Dimension 3 scores were moderately and positively correlated with engagement rate, (ρ = 0.124, p < 0.001). Higher engagement occurred around content portraying specific species, some of which are common in the pet trade. Dimension 4 scores were moderately and negatively correlated with engagement rate, (ρ = −0.121, p < 0.001), indicating lower engagement with videos that aligned with proper primate welfare (no restraints, provisioning of natural diets). Finally, Dimension 5 scores were weakly and positively correlated with engagement rate, (ρ = 0.058, p = 0.033), whereby there was higher engagement with content showing primates wearing clothing and when human artifacts were in frame.

Table 7.

Correlation matrix on engagement rate and dimension scores.

| Engagement rate | Dim. 1 | Dim. 2 | Dim. 3 | Dim. 4 | Dim. 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement rate | Spearman's rho | — | |||||

| df | — | ||||||

| p‐value | — | ||||||

| N | — | ||||||

| Dim. 1 | Spearman's rho | −0.067* | — | ||||

| df | 1370 | — | |||||

| p‐value | 0.012 | — | |||||

| N | 1372 | — | |||||

| Dim. 2 | Spearman's rho | −0.002 | 0.038 | — | |||

| df | 1370 | 1376 | — | ||||

| p‐value | 0.955 | 0.156 | — | ||||

| N | 1372 | 1378 | — | ||||

| Dim. 3 | Spearman's rho | 0.124*** | 0.032 | −0.021 | — | ||

| df | 1370 | 1376 | 1376 | — | |||

| p‐value | < 0.001 | 0.232 | 0.438 | — | |||

| N | 1372 | 1378 | 1378 | — | |||

| Dim. 4 | Spearman's rho | −0.121*** | 0.004 | 0.024 | −0.012 | — | |

| df | 1370 | 1376 | 1376 | 1376 | — | ||

| p‐value | < 0.001 | 0.888 | 0.370 | 0.661 | — | ||

| N | 1372 | 1378 | 1378 | 1378 | — | ||

| Dim. 5 | Spearman's rho | 0.058* | −0.007 | 0.099*** | −0.003 | 0.073** | — |

| df | 1370 | 1376 | 1376 | 1376 | 1376 | — | |

| p‐value | 0.033 | 0.792 | < 0.001 | 0.910 | 0.006 | — | |

| N | 1372 | 1378 | 1378 | 1378 | 1378 | — |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

To provide a more intuitive comparison across the two levels of each dimension, we also calculated the average engagement rate for each group (Figure 3). These averages offer a complementary view of how video performance may differ across the ends of each thematic dimension.

Figure 3.

The average engagement rate across five dimensions. Dimension 1 is the level of human interaction. Dimension 2 is the level of anthropomorphized environment. Dimension 3 is the level of captive context. Dimension 4 is the level of primate exploitation. Dimension 5 is the level of commercial representation.

4. Discussion

TikTok's slogan is “where trends start.” Our survey of primate content on TikTok found that the platform facilitates the creation and distribution of videos that portray primates primarily within artificial settings. Through the use of high‐resolution images, videos, and captivating content, TikTok perpetuates the pet primate trend, which popularizes harmful practices with dangerous welfare applications. We found that, similar to other social media platforms, primates are often depicted as pets and/or often being anthropomorphized. Similar to other studies of primates on social media (Aldrich 2018; Moloney et al. 2021; Nijman et al. 2023), some species were more prevalent (e.g., macaques, capuchins, and marmosets), as well as more commonly promoted or sold as pets (e.g., marmosets and capuchins).

Our results also indicated species, location, and human contact to be variables linked to video engagement rates. Further results of the MCA found these variables to be key attributes to video themes (e.g., Dimension 1: Human Interaction; Dimension 2: Anthropomorphized Environment; etc.). The results comparing engagement rates among the five dimensions yielded some weak, but significant findings. We found that videos with more human interaction (Dimension 1) or showing primates as something to exploit (Dimension 4) had lower engagement. We also found that certain taxa within certain environments (Dimension 3) were associated with higher engagement. Unfortunately, videos with a commercial aspect (Dimension 5), also had slightly higher engagement rates. Dimension 2 highlighted that video setting alone does not affect engagement. This contradicts our earlier finding of location being significant for engagement rate. This could be due to the fact that some primate species are more likely to be seen in some locations than others, so any significant finding for location could be more related to the species portrayed. Although we had some significant findings, it is important to note that no dimension alone was a strong predictor for video engagement. Meaning, primate content on TikTok is popular regardless of the context. With this in mind, our study offers three main takeaways to better understand the type of content guiding video performance and audience engagement on the platform.

4.1. Primates Continue to be Depicted as Pets

The first takeaway is that videos depicting primates as pets were prevalent across the platform. Similar to Carstens (2022), the majority of the videos we analyzed featured primates in household settings, as well as other locations outside of the home but still within the context of being pets (e.g., primates shown at places of business or in vehicles). Videos of primates in zoos, sanctuaries, or in the wild, only made up only a small proportion of content in our sample, and even when present, received lower engagement. Anthropomorphizing primates, through the use of clothing, diapers, and human food items, occurred primarily outside of these accredited settings, yet contributed to themes that received higher engagement than the non‐anthropomorphized counterparts.

Quarles et al. (2023) introduced the concept of wildlife being “decontextualized,” suggesting that as wildlife, like primates, are increasingly removed from their natural ecological contexts, the less we see them as wild animals. As videos of primates as pets appear in algorithm‐based FYP feeds, the user is exposed to this decontextualized image of a primate both within the framing of TikTok videos and within the format of the platform itself. As users engage with content, the algorithm continues to recommend similar videos from various accounts across the app within an endless scroll of content. This continued exposure to primates removed from their wild identity, or their “decontextualization,” makes it possible for primates to then be “recontextualized” as pets.

Platyrrhines were the most common primate in household settings and in videos advertising monkeys for sale, consistent with previous research (de Souza Fialho et al. 2016; do Nascimento et al. 2013; Nijman et al. 2023; Seaboch and Cahoon 2021). The prevalence of small monkeys as pets may be linked to successful campaigns highlighting the difficulties of owning large‐bodied apes, such as difficulty in managing their size and behavior, disease transmission, and their endangered status (Aldrich 2018). Seaboch and Cahoon (2021) explained the motivations of primate ownership are multifaceted, with individuals often seeking primates for their perceived human‐like qualities, companionship, novelty, and social status. Seaboch also noted that while many primate species are vulnerable to the pet trade, certain species are more commonly sought after, due to factors like body size, cost, availability, and perceived suitability as pets.

It has been shown that social media, television, and film continue to influence exotic pet trends and drive acquisition rates due to perceived popularity (Aldrich et al. 2023; Herzog 2006; Moloney et al. 2021; Nijman and Nekaris 2017; Svensson et al. 2022). Videos of primates as pets often appear in viewers' algorithm‐driven FYP feeds, potentially sparking interest in primate ownership among those who hadn't considered it before. This exposure has been associated with a surge in Google searches for primates as pets, as was the case for bushbabies in Svensson et al.'s (2022) study. This increase in searches correlates with a rise in international Galago exports, emphasizing the influence of social media on the exotic pet trade.

Beyond the superficial portrayal of primates as pets, we must also address issues surrounding their welfare. In this study, 88% of videos depicted locations that are unsuitable for primates. Primates are incredibly social animals, and young primates require intensive time with their mother and other group members as they learn the physical and social skills needed to ensure survival and secure psychological well‐being (Hevesi 2023; Rosenbaum and Silk 2022; Silk 2007). It is often the case that infants are sold as pets from breeders and then raised in unnatural environments (Soulsbury et al. 2009). Though we rarely encountered videos that advertised a primate as being for sale either explicitly in the video or caption, on several videos, exchanges between viewers and content creators occurred within the comment section. This is worrisome, even though it was a rare occurrence, because it was a theme extrapolated from the MCA (Dimensions 4 and 5). Even these small exchanges have the potential to drive primate pet sales (Carstens 2022). Regardless of the good intentions of an owner, no home‐based living conditions can adequately provide proper welfare conditions. Primates are unintentionally abused both mentally and physically when they are forced to wear clothing, eat an improper diet, or are deprived of their optimal social conditions, regardless of their owner's potentially loving intentions (Social Media Animal Cruelty Coalition 2022; Soulsbury et al. 2009). Although it was less often the case that primates in this study were observed eating an inappropriate diet or wearing clothing, it was quite often the case that a solitary primate was depicted. We see these questionable conditions of captivity along the lines of The Social Media Animal Cruelty Coalition (SMACC), who recommend the category of “unintentional abuse” when reporting animal cruelty directly to their database (Social Media Animal Cruelty Coalition 2022).

4.2. The Physical Human–Alloprimate Interface

The second takeaway is that interactions between humans and primates are a primary factor behind video popularity. Overall, human presence occurred in over half (57%) of videos, and human–alloprimate contact occurred in 49% of videos in this study. We found that human presence resulted in an increase in the number of interactions (views, likes, comments, and shares; see Supporting Information S1: Table S6) a video received, similar to the findings provided by Carstens (2022). Human presence alone did not affect video engagement rate, however, human contact did. Videos scoring high for human interaction (Dimension 1) also received higher engagement. Human presence or contact can be interpreted as a positive or negative aspect of primate welfare and is highly context dependent. Some might consider a human in close proximity, including physical contact, as a form of enrichment, whereas others might view it from a stance of public health risk.

The prevalence of human contact appearing in TikTok videos presents a legitimate threat of zoonotic disease transmission to both humans and alloprimates (Gilardi et al. 2021; Kalema‐Zikusoka et al. 2021; Lappan et al. 2020). In the videos we observed where a human was present in the video frame, 93.6% of individuals were not wearing any form of PPE. As the majority of primates on TikTok were depicted as pets in household settings, this finding suggests a potential risk of disease transmission between pet primates and their owners. This poses a public health concern, especially given that pet primates were also observed in places of business and other public spaces beyond households.

Human–alloprimate contact is outlined in the Best Practice Guidelines for Responsible Images of Non‐Human Primates (Waters et al. 2021) as a source of concern for primate conservation efforts, as its depictions in media have been found to drive the primate pet trade. Our findings confirmed this concern, as the majority of human contact we observed occurred in household settings. The popularity of human contact within primate content might be explained by the concept of the “encounter value” of animals, wherein sheerly by being encounterable to humans, animals like primates can generate income (as a prop for tourists to pose with, by sale as a pet, or by way of monetary or “like”‐based capital as a popular exotic pet account on TikTok; Collard 2020). The value of human contact with a primate is so sought after that Snapchat developed a filter entitled the “caring monkey,” where a selfie taker can capture a digital macaque sitting on their shoulder and grooming their hair, thus propelling the desirability of this physical interaction (Aldrich et al. 2023). There is a growing body of literature on the effectiveness of captions in providing further context when depicting human–alloprimate interactions. Captions neither mitigate the viewers' perceptions that primates make desirable pets nor the desire to interact with them, and videos using captions in reference to conservation issues do not perform as well (Freund et al. 2021; Freund et al. 2024). Because we found that human contact—not just human presence—was driving video engagement and that captions can be ineffective, social media imagery of human–alloprimate interactions is proving to be counterproductive for primate welfare and conservation.

4.3. The Future: Changing the Trend

The MCA themes provide an insight into what type of content is currently trending on TikTok: content saturated in the anthropomorphism and commodification of primates. Yet, when we break these videos down into their component parts, we find that content providing the opposite—less human influence and natural or wild settings—are able to obtain high levels of engagement. The interplay among or between elements of a video driving engagement is a finding not unique to only this study. Similarly, Shaw et al. (2022) coded and analyzed Instagram posts from wildlife conservation organizations, linking image elements to engagement. They also found that human presence did not impact engagement, and even when engagement was significantly higher with images of human contact, that significance was lost once outliers were removed. It is perhaps becoming evident that when it comes to social media imagery and perception, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. These videos in which primates are not framed as pets often depict more structured human–alloprimate interactions with more careful attention to the needs and welfare of primates. As such, the third takeaway of this study is that this non‐pet primate content could present a potential alternative approach to promoting positive welfare for primates on the platform.

The consistent representation of primates in more suitable wild and captive settings could have a substantial impact on primate conservation and public perceptions. By using TikTok and other social media platforms, researchers, educators, and animal care specialists alike can share and disseminate their research and/or educational materials and conservation messaging. When posting content that includes humans in frame or in direct contact with alloprimates, the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) published image guidelines should be adhered to to avoid the unintended consequences of how human–alloprimate content might be interpreted by the general public (Waters et al. 2021). These guidelines suggest practicing great discretion in posting primate photos and recommend not publishing photos showcasing direct physical contact, photos without proper PPE, professionals not remaining at a safe distance from primates, and to include obvious research materials, like notepads, stopwatches, or binoculars, or husbandry equipment to provide much needed context that is inseparable from the photo visual itself. Human contact with primates is restricted in many professional settings, including zoos, sanctuaries, and the field, for a variety of reasons, including the risks of physical harm and disease transmission.

5. Conclusions

TikTok regularly exhibits various forms and levels of primate exploitation, and most videos serve to perpetuate the notion that primates make suitable household pets. However, because videos from zoos, sanctuaries, and the wild can also compete and perform well in social media spaces, we are optimistic that there is a broader public interest in “wild” wildlife. Many questions remain about how to effectively follow the IUCN guidelines for posting imagery and the effectiveness of captions provided by professionals who work with primates (Freund et al. 2024). Although we found that human presence alone did not significantly enhance video engagement, it was a common component in themes receiving high engagement. Therefore, we suggest that professionals refrain altogether from posting photos posing with the species they study or care for. Regardless of how curated the surrounding context may be, remaining in close proximity to or in direct contact with alloprimates could send the wrong message to the general public. While there is some variability in the effectiveness of conservation‐driven messages or captions tied to videos (Aldrich 2018; Freund et al. 2024; Ross et al. 2011), it has been reported that when the general public is more knowledgeable and has reputable sources about a subject at hand, certainly one as controversial as the exploitation of endangered animals, they are more likely to ask questions and have more negative perceptions of alloprimate use in pop culture (Bergman et al. 2022). It is essential to correct the perception that what the public sees as “cute” can actually be harmful, and it is also important to increase the visibility of responsible content that depicts wild primates in natural, non‐anthropogenic habitats and engaging in species‐specific behaviors. Additionally, when human–alloprimate interactions are unavoidable, it is vital to showcase the clear use of PPE and visible barriers while emphasizing the professional contexts in which these interactions occur (see IUCN guidelines, Waters et al. 2021; Cheyne et al. 2022). Responsible imagery can help shape TikTok content that clearly supports primate welfare and conservation efforts. This responsibility should be shared by all TikTok users—the content creators, the viewers engaging with the material, and the platform's moderators.

Primate content continues to be popular on TikTok and other social media platforms but that does not mean it will never change. Currently, social media platforms have adopted a report‐and‐remove mechanism where users can flag and attempt to categorize content they perceive as violating community guidelines. These reports are reviewed algorithmically or by human moderators, both of which must make decisions about whether to retain or remove content and if further action against the creator, such as account suspension, should occur (Common 2020). These decisions are often made quickly, and the decision‐tree for reporting content as “Animal Abuse” becomes easier to follow when the content is blatantly illegal conduct or overt, often graphic representations of animal abuse where community guidelines are explicitly recognized as being violated. How then, are users and moderators navigating and making decisions around gray zones of context? For example, what actions occur, and in what consistency, around instances of potentially subjective or more subtle gradations of unintentional abuse, animal mistreatment, poor welfare, or questionable contexts (purposefully perpetrated or not; e.g., see Harrington et al. 2023)? These are valid questions currently without concrete answers. As advocates continue to strive for transparency and consistency around moderation, we recommend that users continue to flag and report questionable primate‐related content on TikTok and all other social media platforms. Flags remain a practical mechanism for alerting moderators to content that potentially violates existing terms and conditions or community guidelines. Flags are also a symbolic mechanism of underlying shifts in the perspectives, standards, and tolerances of the larger user base and can pressure platforms to adjust existing community standards to fit current social contexts (Crawford and Gillespie 2014). Though moderators may not understand the harm of pet primate content, reporting videos to SMACC provides data they can compile and provide “Spotlight Reports” to their ongoing efforts and continued dialog with TikTok and other social media giants. Users can also inform TikTok's algorithm that they do not support pet primate content by refusing to interact with it, including interactions that express disapproval within a comment on the post. Although it may seem counterintuitive, the algorithm is not able to discern the sentiment of comments. This means any interaction is taken at face value, and a critical comment is viewed the same as a supportive comment in the eyes of the algorithm.

Nearing the end of data collection, while we began cleaning our video data, we noticed that searching the term “monkey for sale” in TikTok's search bar led to a screen with the following statement: “This phrase may be associated with the illegal trade of wildlife. TikTok is committed to preventing wildlife trafficking on our platform and keeping our community safe. For more information, please view our Community Guidelines” (TikTok 2021). However, videos featuring primates as pets and discussions about purchasing primates in the video comments continue to persist. Although this slight shift in the scope of community guidelines did not eliminate discussions of purchasing or owning primates altogether, it did create a barrier against easily searching for this type of content. In doing so, it provides an example of how the platform can continue to moderate posts moving forward and with increasing levels of stringency. We take this search warning to indicate that others using the platform also have an interest in making animal content more ethical. Therefore, we offer our findings as a means for others to better understand the scope of primate‐related content on TikTok in effort to improve the collective welfare and conservation efforts for captive and wild primates everywhere.

Author Contributions

Kelsie K. Strong: conceptualization (equal), data curation (equal), formal analysis (lead), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), project administration (lead), resources (equal), validation (supporting), visualization (lead), writing – original draft preparation (lead), writing – reviewing and editing (lead). Lilith A. Frakes: investigation (equal), resources (equal), validation (supporting), writing – original draft preparation (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Jessica A. Mayhew: conceptualization (equal), data curation (equal), formal analysis (supporting), funding acquisition (lead), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), resources (equal), supervision (lead), validation (lead), visualization (supporting), writing – original draft preparation (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Chelsea J. Thompson: investigation (equal), resources (supporting), writing – review and editing (supporting). Caroline P. Ratliff: conceptualization (equal), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), resources (supporting), writing – reviewing and editing (supporting).

Supporting information

Supporting Table S1: Presence/Absence Variable Descriptions. Supporting Table S2: Linear Regression Results. Supporting Table S3: Median TikTok Metrics. Supporting Table S4: Food Variable Descriptions. Supporting Table S5: Significant DSCF pairwise comparisons of the median number of views, likes, shares, and comments a video received by taxonomic group. Supporting Table S6: Significant DSCF pairwise comparisons of the median number of views, likes, shares, and comments a video received by video location. Supporting Table S7: Mann‐Whitney U Results on the Number of Views, Likes, Comments, Shares and Overall Engagement and Human Presence.

Acknowledgments

We are beyond appreciative of Patricia Mitchell, who originally proposed this study project, helped to conceptualize it, and contributed to the data collection process. We are also grateful to Ilmi Moen‐Hamm, Kimberly Fowler, and Lauren Kippes for their help with data collection. Watching videos of primates in exploitative situations each week was no easy task, emotionally. We thank Brandon Hosszu and Courtney Garzone for their input on early iterations of the project. We are also thankful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, which aided in significantly improving this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Agoramoorthy, G. , and Hsu M. J.. 2005. “Use of Nonhuman Primates in Entertainment in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 8, no. 2: 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, B. C. 2018. “The Use of Primate ‘Actors’ in Feature Films 1990–2013.” Anthrozoös 31, no. 1: 5–21. 10.1080/08927936.2018.1406197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, B. C. , Feddema K., Fourage A., Nekaris K. A. I., and Shanee S.. 2023. “Primate Portrayals: Narratives and Perceptions of Primates in Entertainment.” In Primates in Anthropogenic Landscapes: Exploring Primate Behavioural Flexibility Across Human Contexts, edited by McKinney T., Waters S. and Rodrigues M. A., Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects, 307–326. Springer. 10.1007/978-3-031-11736-7_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auxier, B. , and Anderson M.. 2021. “Social Media Use in 2021.” Pew Research Center, April 1–6. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/.

- Baccarella, C. V. , Wagner T. F., Kietzmann J. H., and McCarthy I. P.. 2018. “Social Media? It's Serious! Understanding the Dark Side of Social Media.” European Management Journal 36, no. 4: 431–438. 10.1016/j.emj.2018.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, J. N. , Buxton R. T., Lin H. Y., et al. 2022. “Evaluating the Benefits and Risks of Social Media for Wildlife Conservation.” FACETS 7: 360–397. 10.1139/facets-2021-0112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brando, S. 2016. “Wild Animals in Entertainment.” In Animal Ethics in the Age of Humans: Blurring Boundaries in Human‐Animal Relationships, edited by Bovenkerk B. and Keulartz J., The International Library of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Ethics, 295–318. Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-44206-8_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, M. 2022. “Time Is TikToking: User Perceptions of Primate Videos on One of the Fastest Growing Social Media Platforms.” Doctoral dissertation, Durham University. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/543782543.pdf.

- Cervi, L. 2021. “Tik Tok and Generation Z.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 12, no. 2: 198–204. 10.1080/19443927.2021.1915617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheyne, S. M. , Maréchal L., Oram F., Joanna S., and Waters S.. 2022. The IUCN Best Practice Guidelines One Year on: Addressing Some Misunderstandings and Encouraging Primatologists to Be Responsible Messengers. Primate Eye, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Collard, R. C. 2020. Animal Traffic: Lively Capital in the Global Exotic Pet Trade. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Common, M. F. 2020. “Fear the Reaper: How Content Moderation Rules Are Enforced on Social Media.” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 34, no. 2: 126–152. 10.1080/13600869.2020.1733762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courchamp, F. , Jaric I., Albert C., Meinard Y., Ripple W. J., and Chapron G.. 2018. “The Paradoxical Extinction of the Most Charismatic Animals.” PLoS Biology 16, no. 4: e2003997. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, K. , and Gillespie T.. 2014. “What Is a Flag For? Social Media Reporting Tools and the Vocabulary of Complaint.” New Media & Society 18, no. 3: 410–428. 10.1177/1461444814543163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, K. A. , Leahy M., Ross S. R., Wilder Schook M., Ferrie G. M., and Alba A. C.. 2022. “Younger Generations Are More Interested Than Older Generations in Having Non‐Domesticated Animals as Pets.” PLoS One 17: 0262208. 10.1371/journal.pone.0262208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Fialho, M. , Ludwig G., and Valenca‐Montenegro M. M.. 2016. “Legal International Trade in Live Neotropical Primates Originating From South America.” Primate Conservation 30: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento, R. A. , Schiavetti A., and Montaño R. A. M.. 2013. “An Assessment of Illegal Capuchin Monkey Trade in Bahia State, Brazil.” Neotropical Biology & Conservation 8, no. 2: 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- von Essen, E. , Lindsjö J., and Berg C.. 2020. “Instagranimal: Animal Welfare and Animal Ethics Challenges of Animal‐Based Tourism.” Animals 10, no. 10: 1830. 10.3390/ani10101830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feddema, K. , Harrigan P., and Wang S.. 2021. “The Dark and Light Sides of Engagement: An Analysis of User‐Generated Content in Wildlife Trade Online Communities.” Australasian Journal of Information Systems 25: 25. 10.3127/ajis.v25i0.2987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D. A. , and Coose S.. 2022. “Animals in Entertainment.” In Routledge Handbook of Animal Welfare, edited by Knight A., Philips C. and Sparks P., 176–189. Routledge. 10.4324/9781003182351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freund, C. A. , Cronin K. A., Huang M., Robinson N. J., Yoo B., and DiGiorgio A. L.. September 2024. “Effects of Captions on Viewers' Perceptions of Images Depicting Human‐Primate Interaction.” Conservation Biology 38: 1–11. 10.1111/cobi.14199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund, C. A. , Heaning E. G., Mulrain I. R., McCann J. B., and DiGiorgio A. L.. 2021. “Building Better Conservation Media for Primates and People: A Case Study of Orangutan Rescue and Rehabilitation YouTube Videos.” People and Nature 3, no. 6: 1257–1271. 10.1002/pan3.10268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardi, K. , Nziza J., Ssebide B., et al. 2021. “Endangered Mountain Gorillas and COVID‐19: One Health Lessons for Prevention and Preparedness During a Global Pandemic.” American Journal of Primatology 84, no. 4–5: 1–8. 10.1002/ajp.23291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, J. 2024. Americans' Social Media Use. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/01/31/americans-social-media-use/. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, L. A. , Elwin A., Paterson S., and D'Cruze N.. 2023. “The Viewer Doesn't Always Seem to Care—Response to Fake Animal Rescues on YouTube and Implications for Social Media Self‐Policing Policies.” People and Nature 5, no. 1: 103–118. 10.1002/pan3.10416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, L. A. , Macdonald D. W., and D'Cruze N.. 2019. “Popularity of Pet Otters on YouTube: Evidence of an Emerging Trade Threat.” Nature Conservation 36: 17–45. 10.3897/natureconservation.36.33842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, A. , Slotow R., Fraser I., and Di Minin E.. 2017. “Ecotourism Marketing Alternative to Charismatic Megafauna Can Also Support Biodiversity Conservation.” Animal Conservation 20, no. 1: 91–100. 10.1111/acv.12292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, H. 2006. “Forty‐Two Thousand and One Dalmatians: Fads, Social Contagion, and Dog Breed Popularity.” Society & Animals 14, no. 4: 383–397. 10.1163/156853006778882448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hevesi, R. 2023. “The Welfare of Primates Kept as Pets and Entertainers.” In Nonhuman Primate Welfare: From History, Science, and Ethics to Practice, edited by Robinson L. M. and Weiss A., 121–144. 1st ed. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kalema‐Zikusoka, G. , Rubanga S., Ngabirano A., and Zikusoka L.. 2021. “Mitigating Impacts of the COVID‐19 Pandemic on Gorilla Conservation: Lessons From Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, Uganda.” Frontiers in Public Health 9, August: 1–7. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.655175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson, H. , and Nekaris K. A. I.. 2017. “Instagram‐Fuelled Illegal Slow Loris Trade Uncovered in Marmaris, Turkey.” Oryx 51, no. 3: 394. 10.1017/S0030605317000680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lappan, S. , Malaivijitnond S., Radhakrishna S., Riley E. P., and Ruppert N.. 2020. “The Human–Primate Interface in the new Normal: Challenges and Opportunities for Primatologists in the COVID‐19 Era and Beyond.” American Journal of Primatology 82, no. 8: 1–12. 10.1002/ajp.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblay, T. , Tuffin F., Saland M., Faure M., and Lê S.. n.d. MEDA ‐ Multivariate Exploratory Data Analysis (Version 1.0.0). [Jamovi Module]. https://sebastien-le.github.io/medasite/index.html.

- Leighty, K. A. , Valuska A. J., Grand A. P., et al. 2015. “Impact of Visual Context on Public Perceptions of Non‐Human Primate Performers.” PLoS One 10, no. 2: e0118487. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, C. , Speiran S., and Grasso C.. 2020. “Let Me Take a Selfie': Implications of Social Media for Public Perceptions of Wild Animals.” Society & Animals 31, no. 1: 64–83. 10.1163/15685306-BJA10023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn, T. , and Rose P. E.. 2021. “Education Is Entertainment? Zoo Science Communication on YouTube.” Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 2, no. 2: 250–264. 10.3390/jzbg2020017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Love, J. , and Agosti M.. n.d. Rj ‐ Editor to Run R Code Inside Jamovi (Version 2.0.8). [Jamovi Module].

- MacKinnon, M. 2006. “Supplying Exotic Animals for the Roman Amphitheatre Games: New Reconstructions Combining Archaeological Ancient Textual, Historical and Ethnographic Data.” Mouseion: Journal of the Classical Association of Canada 50, no. 2: 137–161. [Google Scholar]

- Moloney, G. K. , Tuke J., Dal Grande E., Nielsen T., and Chaber A. L.. 2021. “Is YouTube Promoting the Exotic Pet Trade? Analysis of the Global Public Perception of Popular YouTube Videos Featuring Threatened Exotic Animals.” PLoS One 16, 4 April: e0235451. 10.1371/journal.pone.0235451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekaris, I. , Anne K., Musing L., Vazquez A. G., and Donati G.. 2016. “Is Tickling Torture? Assessing Welfare Towards Slow Lorises (Nycticebus spp.) Within Web 2.0 Videos.” Folia Primatologica 86, no. 6: 534–551. 10.1159/000444231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekaris, K. A. I. , Campbell N., Coggins T. G., Rode E. J., and Nijman V.. 2013. “Tickled to Death: Analysing Public Perceptions of ‘Cute’ Videos of Threatened Species (Slow Lorises ‐ Nycticebus spp.) on Web 2.0 Sites.” PLoS One 8, no. 7: e69215. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman, V. , Ardiansyah A., Langgeng A., et al. 2022. “Illegal Wildlife Trade in Traditional Markets, on Instagram and Facebook: Raptors as a Case Study.” Birds 3, no. 1: 99–116. 10.3390/birds3010008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman, V. , Morcatty T. Q., El Bizri H. R., et al. 2023. “Global Online Trade in Primates for Pets.” Environmental Development 48: 100925. [Google Scholar]

- Nijman, V. , and Nekaris K. A. I.. 2017. “The Harry Potter Effect: The Rise in Trade of Owls as Pets in Java and Bali, Indonesia.” Global Ecology and Conservation 11: 84–94. 10.1016/j.gecco.2017.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman, V. , Smith J. H., Foreman G., Campera M., Feddema K., and Nekaris K. A. I.. 2021. “Monitoring the Trade of Legally Protected Wildlife on Facebook and Instagram Illustrated by the Advertising and Sale of Apes in Indonesia.” Diversity 13, no. 6: 236. 10.3390/d13060236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, V. F. , Lopes P. F. M., and Ferreira R. G.. 2023. “#capuchinmonkeys on Social Media: A Threat for Species Conservation.” Anthrozoös 36, no. 4: 665–683. 10.1080/08927936.2023.2210440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel, C. D. , Orams M., and Lück M.. 2020. “#biteme: Considering the Potential Influence of Social Media on in‐Water Encounters With Marine Wildlife.” Tourism in Marine Environments 15, no. 3: 249–258. 10.3727/154427320X15754936027058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quarles, L. F. , Feddema K., Campera M., and Nekaris K. A. I.. 2023. “Normal Redefined: Exploring Decontextualization of Lorises (Nycticebus & Xanthonycticebus spp.) on Social Media Platforms.” Frontiers in Conservation Science 4: 1–10. 10.3389/fcosc.2023.1067355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle, E. , and MacKay J. R. D.. 2020. “Social Media Contexts Moderate Perceptions of Animals.” Animals 10, no. 5: 845. 10.3390/ani10050845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley Koenig, C. M. , Koenig B. L., and Sanz C. M.. 2019. “Overrepresentation of Flagship Species in Primate Documentaries and Opportunities for Promoting Biodiversity.” Biological Conservation 238: 108188. 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodela, J. September 2023. “TikTok Algorithm 2024 Explained: How It Works Plus Tips to Go Viral.” VistaSocial. https://vistasocial.com/insights/tiktok-algorithm-2023/.

- Rosenbaum, S. , and Silk J. B.. 2022. “Pathways to Paternal Care in Primates.” Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 31, no. 5: 245–262. 10.1002/evan.21942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S. R. , Vreeman V. M., and Lonsdorf E. V.. 2011. “Specific Image Characteristics Influence Attitudes About Chimpanzee Conservation and Use as Pets.” PLoS One 6, no. 7: e22050. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroepfer, K. K. , Rosati A. G., Chartrand T., and Hare B.. 2011. “Use of ‘Entertainment’ Chimpanzees in Commercials Distorts Public Perception Regarding Their Conservation Status.” PLoS One 6, no. 10: e26048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaboch, M. S. , and Cahoon S. N.. 2021. “Pet Primates for Sale in the United States.” PLoS One 16, 9 September: e0256552. 10.1371/journal.pone.0256552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehl, K. , and Tien S.. February 2023. Engagement Rate Calculator + Guide for 2024. Hootsuite. https://blog.hootsuite.com/calculate-engagement-rate/#6_engagement_rate_formulas. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, M. N. , Borrie W. T., McLeod E. M., and Miller K. K.. 2022. “Wildlife Photos on Social Media: A Quantitative Content Analysis of Conservation Organisations' Instagram Images.” Animals 12, no. 14: 1787. 10.3390/ani12141787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, J. 2014. “Spectacles of Animal Abuse.” In The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life, edited by Campbell G. L., 461–477. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silk, J. B. 2007. “Social Components of Fitness in Primate Groups.” Science 317, no. 5843: 1347–1351. 10.1126/science.1140734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Media Animal Cruelty Coalition . 2022. “What's the Issue?” https://www.smaccoalition.com/issue.

- Soulsbury, C. D. , Iossa G., Kennell S., and Harris S.. 2009. “The Welfare and Suitability of Primates Kept as Pets.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 12, no. 1: 1–20. 10.1080/10888700802536483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spee, L. B. , Hazel S. J., Dal Grande E., Boardman W. S. J., and Chaber A. L.. 2019. “Endangered Exotic Pets on Social Media in the Middle East: Presence and Impact.” Animals 9, no. 8: 480. 10.3390/ani9080480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista . February 2025. “Number of Social Media Users Worldwide From 2017 to 2028.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/.

- Sterckx, R. 2012. “Animals, Gaming and Entertainment in Traditional China.” In Perfect Bodies: Sports, Medicine and immortality, edited by Lo V., British Museum Research Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, M. S. , Morcatty T. Q., Nijman V., and Shepherd C. R.. 2022. “The Next Exotic Pet to Go Viral: Is Social Media Causing an Increase in the Demand of Owning Bushbabies as Pets?” Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy 33, no. 1: 51–57. 10.4404/hystrix. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- TikTok . June 2020. “How TikTok Recommends Videos #ForYou.” https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/how-tiktok-recommends-videos-for-you.

- TikTok . May 2021. Search Entry: “Monkey for Sale.” https://www.tiktok.com/search/user?q=monkey%20for%20sale&t=1740875903233.

- TikTok . March 2024a. “About. TikTok.” https://www.tiktok.com/about?enter_method=bottom_navigation.

- TikTok . March 2024b. “Community Guidelines. TikTok.” https://www.tiktok.com/community-guidelines/en/overview/.

- Twining‐Ward, C. , Luna J. R., Back J. P., et al. 2022. “Social Media's Potential to Promote Conservation at the Local Level: An Assessment in Eleven Primate Range Countries.” Folia Primatologica 93, no. 2: 163–173. 10.1163/14219980-bja10001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, S. , Setchell J. M., Maréchal L., Oram F., Wallis J., and Cheyne S. M.. 2021. “Best Practice Guidelines for Responsible Images of Non‐Human Primates. The IUCN Primate Specialist Group Section for Human–Primate Interactions.” https://human-primate-interactions.org/resources/.

- Yates, R. 2009. “Rituals of Dominionism in Human‐Nonhuman Relations: Bullfighting to Hunting, Circuses to Petting.” Journal for Critical Animal Studies 7, no. 1: 132–171. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Table S1: Presence/Absence Variable Descriptions. Supporting Table S2: Linear Regression Results. Supporting Table S3: Median TikTok Metrics. Supporting Table S4: Food Variable Descriptions. Supporting Table S5: Significant DSCF pairwise comparisons of the median number of views, likes, shares, and comments a video received by taxonomic group. Supporting Table S6: Significant DSCF pairwise comparisons of the median number of views, likes, shares, and comments a video received by video location. Supporting Table S7: Mann‐Whitney U Results on the Number of Views, Likes, Comments, Shares and Overall Engagement and Human Presence.

Data Availability Statement