Abstract

This study investigated the antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic properties of extracts from Elaphomyces cyanosporus, E. granulatus, and E. mutabilis mushrooms. The methanol extract of E. mutabilis had the highest total phenol and flavonoid content, with methanol extracts generally showing higher levels than water extracts. HPLC analysis identified gallic acid as the predominant phenolic compound in the E. mutabilis methanol extract (552.3 µg/g), along with chlorogenic acid and quercetin (75.84 µg/g). DPPH radical scavenging activity was highest in the methanol extract of E. granulatus, with the lowest IC50 value in E. mutabilis (38.20 µg/mL), indicating moderate antioxidant capacity. In metal chelation, both E. mutabilis and E. granulatus methanol extracts showed strong activity. Antibacterial tests revealed methanol extracts were more effective than water extracts, with E. cyanosporus showing the highest inhibition against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cytotoxicity was evaluated on HT-29 human colon cancer and L929 mouse fibroblast cell lines. The methanol extract of E. mutabilis exhibited significant DPPH scavenging, metal chelation, and selective cytotoxicity against HT-29 cells, with minimal effects on normal L929 cells. This selective toxicity suggests potential for developing anticancer agents with limited toxicity to normal cells. These findings highlight the potential for new antibacterial and anticancer agents from mushroom extracts.

Keywords: Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Bioactive compounds, Cytotoxicity, Elaphomyces, Nutraceuticals

Subject terms: Cell death, Chemical biology, Natural products

Introduction

The importance of natural compounds in cancer treatment is increasing. Natural compounds, obtained from plants, sea creatures, and microorganisms, have been shown to be effective in combating cancer1,2. Plant-derived compounds, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, are known for their antioxidant properties and can inhibit cancer cell growth by reducing oxidative stress3–5. Additionally, natural compounds may have chemopreventive effects, preventing or repairing DNA damage at the cellular level6,7. These compounds can be used in combination with traditional cancer treatments (chemotherapy, radiotherapy) to increase treatment effectiveness. Such combinations may be more effective at destroying treatment-resistant cancer cells8,9.

Mushrooms are rich in natural compounds and attract significant attention due to their positive effects on health. They are especially rich in beta-glucans, which have beneficial effects on the immune system. These polysaccharides can enhance immune responses by activating macrophages and other immune cells10,11. This provides protection against infections and also supports the defense mechanism against cancer cells12. Some mushrooms, such as reishi mushrooms, contain compounds called triterpenoids, which have anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and antioxidant properties and may play a role in cell protection and cancer prevention13,14.

Mushrooms are also rich in various vitamins (B vitamins, vitamin D) and minerals (selenium, potassium). These nutrients are important for overall health and support immune functions15,16. In addition, mushrooms contain phenolic compounds and flavonoids that have antioxidant properties. These compounds may reduce inflammation, inhibit the growth of cancer cells, and support cardiovascular health17. Penicillin, derived from the Penicillium fungus, is an example of the natural antibiotic properties of fungi18. Furthermore, mushrooms contain various antimicrobial compounds, making them effective in fighting infections19,20.

Elaphomyces T. Nees is an underground, spore-bearing genus within the Elaphomycetaceae family (Ascomycota). This genus is widely distributed across various forest habitats, from temperate and subarctic coniferous forests to tropical lowland regions21,22. Species within this genus, commonly called “deer fungus,” form ectomycorrhizal partnerships with the roots of numerous trees and shrubs worldwide23,24. While the biological activities of various Elaphomyces species have been documented, including antioxidant, anticancer, and antibacterial properties, this genus remains largely unexplored25–27. Despite these promising characteristics, studies on Elaphomyces are limited, and the full extent of their biological activities, particularly in cancer prevention and antibacterial efficacy, has yet to be fully investigated.

This research aims to address this gap by investigating three species of Elaphomyces: Elaphomyces cyanosporus Tul. & C. Tul., E. granulatus Fr., and E. mutabilis Vittad. To the best of our knowledge, the antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic effects of the methanol and water extracts of these species have not been tested. This study will evaluate the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging activity, metal chelation, and the total phenol and flavonoid contents of these extracts using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. Furthermore, the antibacterial effects of these extracts on human pathogenic gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria will be investigated, along with their cytotoxic effects on human colon cancer (HT-29) and mouse fibroblast (L929) cells.

Our goal is to help the pharmaceutical industry develop supplementary antioxidant sources with both antioxidant and cytotoxic properties, utilizing E. cyanosporus, E. granulatus, and E. mutabilis. Additionally, this research aims to provide an alternative treatment strategy against resistant bacterial strains. In summary, this study aims to fill the existing research gap and explore the potential therapeutic properties of Elaphomyces species, contributing to cancer therapy and antibacterial treatment.

Results and discussion

Effect of solvent type and species on extraction yields

Yield percentages of the extracts (ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis) obtained from mushroom samples are shown in Table 1. A clear trend was observed in the extraction yields depending on both the solvent type and the species used. In general, methanol extracts showed slightly higher or comparable yields compared to water extracts within the same species. For instance, ECME yielded 30.85%, while the corresponding ECWE yielded 28.75%. Similarly, EGME yielded 19.10%, slightly lower than EGWE at 20.00%, while for EMME yielded 16.14%, higher than EMWE at 14.12%. These results suggest that although methanol generally provides a better extraction yield, species-specific differences may influence solvent efficiency. This trend aligns with known solvent properties, where methanol, being a polar organic solvent, effectively extracts a wide range of polar and moderately non-polar compounds28. However, water, despite being highly polar, may show competitive efficiency due to its strong affinity for hydrophilic compounds. Therefore, the extraction efficiency appears to be influenced not only by solvent polarity but also by the specific chemical composition of the species29.

Table 1.

Yield (%) of obtained the mushroom extracts.

| Extract | Abbreviation of the extracts | Yield (w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol extract obtained from E. cyanosporus | ECME | 30.85 |

| Water extract obtained from E. cyanosporus | ECWE | 28.75 |

| Methanol extract obtained from E. granulatus | EGME | 19.10 |

| Water extract obtained from E. granulatus | EGWE | 20.00 |

| Methanol extract obtained from E. mutabilis | EMME | 16.14 |

| Water extract obtained from E. mutabilis | EMWE | 14.12 |

Although the present study did not investigate the effects of extraction parameters such as time, temperature, or solvent concentration, previous research has demonstrated that these factors significantly influence antioxidant yield. For example, higher extraction temperatures can enhance the solubility and diffusion of phenolic compounds but may also lead to thermal degradation if excessive. Similarly, prolonged extraction times may improve yield up to a point, beyond which degradation or oxidation may occur. Studies have also shown that the concentration and polarity of the solvent directly affect the efficiency of extracting antioxidant compounds30,31. Future studies should consider optimizing these parameters to maximize the recovery of bioactive compounds.

Identification and quantification of main phenolic compounds by HPLC

The present study demonstrated significant differences in the phenolic acid and flavonoid profiles of E. cyanosporus, E. granulatus, and E. mutabilis, as analyzed through HPLC. The HPLC chromatograms of the tested extracts were presented in Fig. 1. Methanol extracts were found to possess higher concentrations of both phenolic acids and flavonoids compared to water extracts, which is consistent with the known efficiency of methanol as a solvent for extracting phenolic compounds due to its ability to dissolve both polar and non-polar molecules32,33.

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatograms of the extracts recorded at (a) 254 nm and (b) 280 nm, along with (c) chromatograms of the standard compounds measured at both 254 and 280 nm. ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Among the identified phenolic acids, gallic acid, known for its potent antioxidant properties, was found in the highest concentration (552.3 µg/g) in EMME (Table 2). Similar high levels of gallic acid have been reported in Ganoderma lucidum34 and Pleurotus ostreatus35which are widely recognized for their antioxidant potential, largely attributed to gallic acid content. This aligns with previous studies that have reported gallic acid as a major constituent in various mushroom species, contributing to their strong radical scavenging abilities36,37. Chlorogenic acid, cinnamic acid, p-coumaric acid, 8 − 4’-dehydrodiferulic acid, isoferulic acid, and protocatechuic acid were also detected in all extracts, reinforcing the idea that Elaphomyces species are a rich source of phenolic acids, which play crucial roles in their biological activities, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects38,39.

Table 2.

Quantities (µg/g) of different phenolic acids of the plant extracts.

| Plant extracts (µg/g) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids |

Detection wavelength (nm) |

RT (min) | ECME | ECWE | EGME | EGWE | EMME | EMWE |

| Chlorogenic acid | 280 | 6.932 | 176.1 ± 1.52 | 111.4 ± 1.23 | 211.2 ± 1.47 | 143.4 ± 1.27 | 243.1 ± 2.42 | 101.3 ± 1.12 |

| Cinnamic acid | 280 | 70.061 | 2.987 ± 0.21 | 2.122 ± 0.35 | 3.556 ± 0.12 | 3.143 ± 0.54 | 3.922 ± 0.71 | 2.725 ± 0.36 |

| p-Coumaric acid | 280 | 13.403 | 3.492 ± 0.05 | 2.102 ± 0.08 | 5.003 ± 0.15 | 4.230 ± 0.21 | 5.602 ± 0.43 | 3.723 ± 0.18 |

| 8 − 4’-Dehydrodiferulic acid | 254 | 55.553 | 19.13 ± 0.51 | 5.457 ± 0.25 | 11.03 ± 0.65 | 8.457 ± 0.84 | 12.84 ± 0.72 | 7.947 ± 0.52 |

| Gallic acid | 254 | 3.502 | 483.1 ± 6.06 | 403.7 ± 10.1 | 502.6 ± 9.87 | 470.7 ± 6.89 | 552.3 ± 5.46 | 456.9 ± 4.68 |

| Isoferulic acid | 280 | 46.267 | 1.791 ± 0.01 | 1.423 ± 0.02 | 2.124 ± 0.03 | 2.246 ± 0.05 | 2.457 ± 0.06 | 1.983 ± 0.32 |

| Protocatechuic acid | 254 | 4.582 | 175.6 ± 7.82 | 121.8 ± 6.32 | 187.43 ± 4.51 | 157.6 ± 8.32 | 254.2 ± 7.64 | 163.5 ± 5.78 |

Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). nd: not determined. ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

In terms of flavonoid content, quercetin was the most abundant (75.84 µg/g) in EMME (Table 3). Quercetin is well-known for its wide range of biological effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities40,41. Previous studies on Trametes versicolor42 and Lentinula edodes43 have also highlighted quercetin as a key flavonoid contributing to their health-promoting effects. The comparable flavonoid profiles observed in our study reinforce the therapeutic potential of Elaphomyces species. The presence of other key flavonoids such as epicatechin, resveratrol, and rutin in both methanol and water extracts further suggests that these mushrooms could be valuable for nutraceutical applications, especially considering the health-promoting benefits associated with these compounds44,45. The flavonoid compounds detected in this study differ structurally in terms of their hydroxylation patterns, glycosylation, and degree of polymerization. These structural variations significantly affect their biological activities46. For instance, flavonoids with a higher number of hydroxyl groups tend to exhibit stronger antioxidant properties due to their enhanced capacity to donate hydrogen atoms. Additionally, the presence of glycosyl moieties may influence the compound’s solubility, stability, and bioavailability, thereby modifying their overall biological effect47. Moreover, the position of hydroxyl groups on the flavonoid backbone, especially in the B ring, plays a critical role in determining the radical scavenging activity. These structural aspects are essential to understanding the functional diversity of the flavonoids identified in our study and their potential contribution to the observed biological outcomes48.

Table 3.

Quantities (µg/g) of different flavonoids of the plant extracts.

| Plant extracts (µg/g) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids |

Detection wavelength (nm) |

RT (min) | ECME | ECWE | EGME | EGWE | EMME | EMWE |

|

4,2’-Dihydroxychalcone 4-glucoside |

280 | 51.456 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Epicatechin | 280 | 33.944 | 0.984 ± 0.05 | 0.307 ± 0.03 | 1.021 ± 0.12 | 0.531 ± 0.07 | 1.137 ± 0.23 | 0.343 ± 0.06 |

| Naringenin | 280 | 60.317 | nd | nd | 1.001 ± 0.12 | 0.743 ± 0.17 | 1.223 ± 0.21 | 0.386 ± 0.05 |

| Phloridzin | 280 | 25.587 | 0.841 ± 0.12 | nd | 0.954 ± 0.07 | nd | 1.203 ± 0.12 | nd |

| Quercetin | 254 | 64.938 | 63.42 ± 4.31 | 54.48 ± 2.53 | 70.42 ± 6.22 | 72.14 ± 3.67 | 75.84 ± 3.51 | 67.82 ± 5.32 |

| Resveratrol | 280 | 28.818 | 0.743 ± 0.07 | 0.431 ± 0.09 | 1.985 ± 0.12 | 1.427 ± 0.23 | 2.457 ± 0.31 | 1.103 ± 0.17 |

| Rutin | 280 | 32.177 | 0.087 ± 0.01 | 0.075 ± 0.01 | 0.112 ± 0.02 | 0.127 ± 0.01 | 0.143 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). nd: not determined. ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

The higher concentrations of phenolic acids and flavonoids in methanol extracts indicate that methanol is a more effective solvent than water for extracting these bioactive compounds from Elaphomyces species. This may be due to the enhanced solubility of phenolic compounds in organic solvents, which facilitates better extraction yields49,50. This finding is also in agreement with previous extraction studies involving Inonotus obliquus51 and Hericium erinaceus52where methanol was shown to outperform aqueous solvents in phenolic and flavonoid recovery. These findings suggest that the choice of solvent is crucial when aiming to maximize the extraction of phenolic acids and flavonoids from mushroom species.

Overall, the HPLC results of this study highlight the potential of E. mutabilis, particularly its methanol extract, as a rich source of bioactive phenolic compounds. Future research should explore the bioavailability and bioactivity of these compounds in vivo to further validate their potential health benefits.

Determination of antioxidant compounds

When the total phenol and total flavonoid contents of the tested mushroom extracts were considered, the highest rates (91.36 µg GAE/mg extract and 76.06 QE/mg extract, respectively) were in the EMME application. When both total phenol and total flavonoid contents were considered, extracts were in the ascending order of ECWE < EMWE < EGWE < ECME < EGME EMME. Antioxidant compounds in methanol extracts were found to be higher than in water extracts. In addition, total phenol and total flavonoid ratios for each extract were statistically different from each other (Table 4). The superior efficiency of methanol compared to water in the extraction of phenolic and flavonoid compounds can be attributed to differences in polarity and solubility parameters. Methanol is a moderately polar solvent with a lower dielectric constant than water, allowing it to dissolve a broader range of compounds, including those with both polar and slightly non-polar characteristics53. Many phenolic and flavonoid compounds exhibit partial polarity, making them more soluble in solvents like methanol. Furthermore, methanol’s lower viscosity and surface tension enhance its ability to penetrate plant tissues and facilitate the efficient release of target phytochemicals54. Our results are in agreement with previous studies on various mushroom species. For instance, Pleurotus eous55 was reported to have a total phenolic content in high ration, while Russula pseudocyanoxantha56 showed different flavonoid concentrations. As seen in the literature, it is noteworthy that total phenolic and flavonoid contents are high in many different mushroom species57,58. Phenols increase the antioxidant capacity of mushrooms through their ability to neutralize free radicals. This helps protect cells from oxidative damage59. Flavonoids also have strong antioxidant properties and protect cells from free radical damage60. Phenols and flavonoids have anti-inflammatory effects due to their ability to reduce inflammation. This may be useful in the management of inflammatory diseases and conditions61. Phenolic compounds and flavonoids may inhibit the growth and spread of some cancer cells. They may play a protective role against cancer thanks to their antioxidant and antimicrobial effects62. These properties make mushrooms usable for medicinal purposes. Mushrooms with high phenolic and flavonoid contents in particular may provide more health benefits63. Although studies reflecting the antioxidant contents of different metabolites and extracts of Elaphomyces species are available in the literature26, there were no studies on methanol and water extracts of the mushrooms we tested. This reveals the original value of our study.

Table 4.

Antioxidant compounds of the mushroom extracts (µg/mg).

| Treatment | Total phenol (Gallic acid equivalent) |

Total flavonoid (Quercetin equivalent) |

|---|---|---|

| ECME | 67.32 ± 1.43 c | 56.26 ± 1.10 c |

| ECWE | 41.95 ± 1.22 f | 21.30 ± 0.51 f |

| EGME | 83.91 ± 1.96 b | 62.82 ± 0.83 b |

| EGWE | 63.06 ± 1.10 d | 47.55 ± 0.87 d |

| EMME | 91.36 ± 1.75 a | 76.06 ± 0.89 a |

| EMWE | 46.53 ± 1.96 e | 36.19 ± 0.56 e |

Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Values indicated by different letters in the same column differ from each other at the level of p < 0.05. ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

DPPH radical scavenging activity

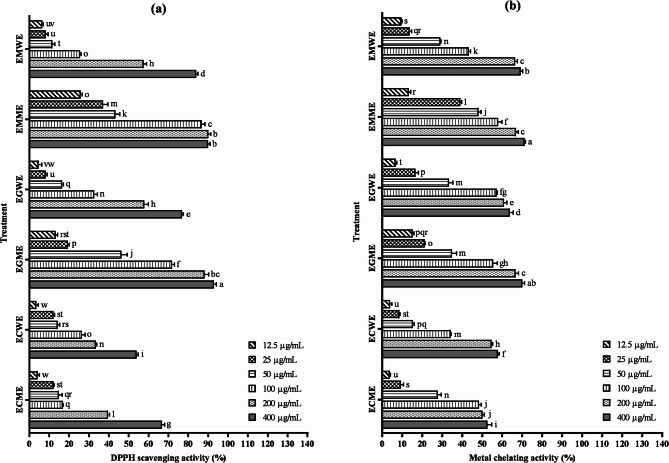

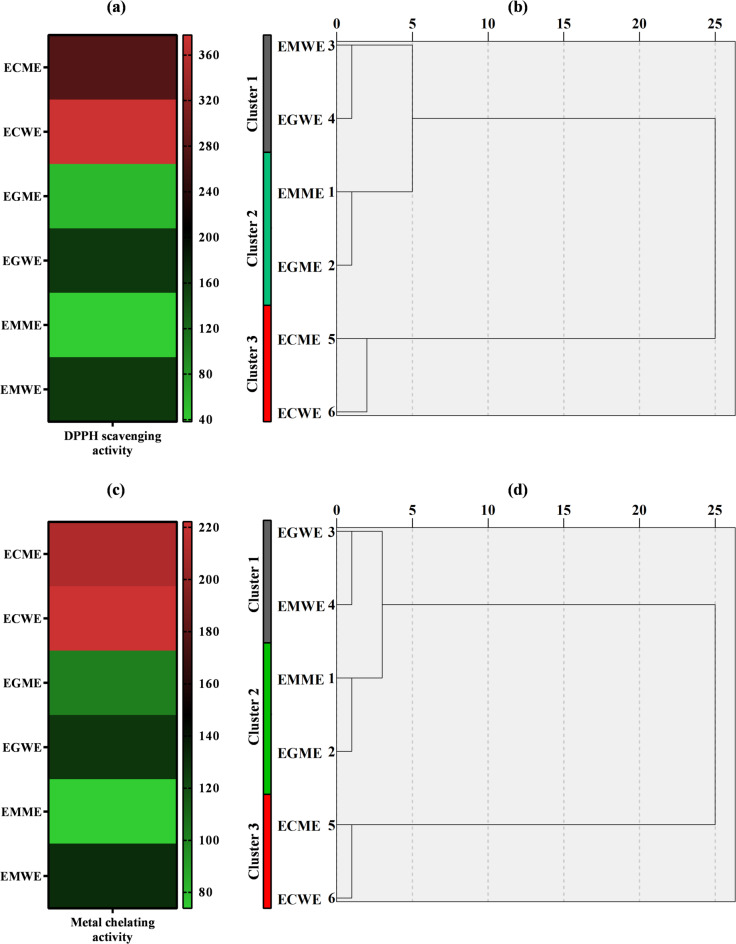

When the DPPH scavenging activities of the tested mushrooms were examined, a concentration-dependent increase was detected. The highest rate (92.94%) belonged to the maximum concentration of EGME. At the same time, this rate was statistically (p < 0.05) different from all other trials (Fig. 2a). When the IC50 value calculated to determine the most effective extract was taken into account, EMME (38.20 µg/mL) was notable for its lowest data. Considering the different extracts of each mushroom, methanol extracts with lower IC50 values showed more effective DPPH scavenging activity (Table 5). According to the heatmap and clustering analyses performed based on IC50 values to determine the similarity rates and activity levels of each extract, EMME and EGME appeared as the most effective applications under a single cluster. The least effective practices appeared in the data for mushrooms ECME and ECWE, and these two practices were included under Cluster 3 (Fig. 3a, b). The superior activity of EMME and EGME methanol extracts can be explained by their distinct phytochemical composition. HPLC analysis revealed that both extracts contained notably higher levels of phenolic acids and flavonoids compared to other samples. These compounds are well known for their strong antioxidant, metal chelating, and cytotoxic properties due to their ability to donate hydrogen atoms or electrons and chelate redox-active metals. The enhanced biological activities observed in EMME and EGME are therefore likely driven by the presence and abundance of these bioactive molecules. The effectiveness of methanol as a solvent in extracting these relatively polar compounds further supports the observed results64. As seen in previous scientific studies, many mushroom species have DPPH radical scavenging activity65–67. Previous studies on mushrooms such as Lentinula edodes68Auricularia auricula69and Ganoderma applanatum70 reported IC50 values ranging from 40 to 600 µg/mL, depending on extraction method and species. Compared to these findings, the IC50 value of 38.20 µg/mL observed for EMME demonstrates a remarkably strong DPPH scavenging potential. This positions E. mutabilis methanol extract as a more potent antioxidant than many commonly studied mushrooms. Free radicals damage cells, leading to oxidative stress. This stress is associated with aging, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic diseases71. Antioxidants with high DPPH scavenging activity may help prevent these diseases and protect cells. Antioxidants provide benefits such as delaying skin aging and supporting overall health. DPPH free radical scavenging activity therefore plays a critical role in antioxidant research and applications and provides significant benefits to human health72. There is no study in the literature on the DPPH scavenging activities of the mushroom extracts we used in our study. Therefore, we preferred to focus on this activity.

Fig. 2.

(a) DPPH radical scavenging and (b) metal chelating activities of different extracts from the mushrooms (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3). Values indicated by different letters differ from each other at the level of p < 0.05. ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Table 5.

IC50 values (µg/mL) resulting from DPPH scavenging activities of the mushroom extracts.

| Treatment | IC50 (Limits) | Slope ± Standard error of the mean (Limits) |

|---|---|---|

| ECME | 276.53 (238.86–327.65) | 1.35 ± 0.07 (1.20–1.50) |

| ECWE | 377.50 (310.34–479.09) | 1.13 ± 0.07 (0.99–1.27) |

| EGME | 55.57 (51.14–60.31) | 1.92 ± 0.07 (1.77–2.07) |

| EGWE | 161.31 (146.30–179.18) | 1.71 ± 0.07 (1.55–1.86) |

| EMME | 38.20 (34.30–42.28) | 1.54 ± 0.07 (1.39–1.68) |

| EMWE | 160.42 (146.14–177.27) | 1.82 ± 0.08 (1.66–1.98) |

ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Fig. 3.

Heatmaps and dendrograms based on IC50 values for (a, b) DPPH scavenging and (c, d) metal chelating activities of mushroom extracts (High and low activities were represented by red and green colour, respectively). ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Metal chelating activity

When the metal chelating activities of the tested mushrooms were examined, a concentration-dependent increase was observed. The highest concentration (400 µg/mL) application of EMME showed the highest activity with 71.25%, while the highest concentration application of EGME revealed an activity of 70.05%. It was calculated that these two data points were statistically indistinguishable from each other (p > 0.5), indicating no meaningful difference between them (Fig. 2b). When IC50 values of the extracts were taken into consideration, the following order emerged: EMME < EGME < EGWE < EMWE < ECME < ECWE (Table 6). According to the heatmap and cluster analysis calculated by taking into account the IC50 values, the most effective applications were mushrooms EMME and EGME under Cluster 2. Similar to the DPPH scavenging analysis, the least effective treatments in the metal chelation activity analysis were mushrooms ECME and ECWE, which have a red colour gradient and are under Cluster 3 (Fig. 3c, d). The metal chelating activities of various mushrooms have been previously reported to range from 60 to 83% in species such as Pleurotus citrinopileatus, Pleurotus djamor, Pleurotus eryngii, Pleurotus flabellatus, Pleurotus florida, Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus sajor-caju, and Hypsizygus ulmarius73. Compared to these findings, the activities observed in EMME (71.25%) and EGME (70.05%) are highly competitive, suggesting that Elaphomyces species can be as effective as traditionally studied medicinal mushrooms in terms of chelation potential. Studies on the metal chelating activities of different mushroom species are available in the literature74,75. All these studies have shown that the natural contents of mushrooms have the capacity to chelate metal ions that may cause oxidative stress76. Chelating agents help prevent oxidative stress and related cellular damage by reducing the effect of metal ions in triggering free radical production77. Mushrooms have an important place as natural chelating agents. They can be used as chelating agents due to their ability to bind metal ions and remove them from the environment or the body by complexing them78. The metal chelating activity of the extracts of mushrooms in our study has not been previously reported in the existing literature and provides a new and original contribution to the field of research.

Table 6.

IC50 values (µg/mL) resulting from metal chelating activities of the mushroom extracts.

| Treatment | IC50 (Limits) | Slope ± Standard error of the mean (Limits) |

|---|---|---|

| ECME | 211.10 (182.27–249.86) | 1.17 ± 0.07 (1.04–1.31) |

| ECWE | 222.18 (195.28–257.07) | 1.39 ± 0.07 (1.24–1.54) |

| EGME | 101.81 (89.76–116.26) | 1.13 ± 0.06 (1.01–1.26) |

| EGWE | 128.26 (113.52–146.30) | 1.22 ± 0.06 (1.09–1.35) |

| EMME | 73.87 (64.02–85.28) | 0.98 ± 0.06 (0.85–1.10) |

| EMWE | 131.84 (117.50–149.20) | 1.32 ± 0.06 (1.19–1.46) |

ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

The observed concentration-dependent increase in metal chelation activity of the mushroom extracts can be attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds, such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, and other secondary metabolites, which are known for their metal-chelating abilities. These compounds possess functional groups, such as hydroxyl (-OH) and carbonyl (C = O) groups, that can form coordination bonds with metal ions, thereby inhibiting metal-induced oxidative stress79. Studies have demonstrated that phenolic compounds, including polyphenols, flavonoids, and tannins, are effective in chelating metal ions such as Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Zn²⁺, which are involved in the generation of free radicals77. Additionally, the efficiency of metal chelation in mushroom extracts may vary depending on the concentration of these compounds, as higher concentrations lead to more available binding sites for metal ions. Therefore, the chelation activity observed in the extracts is likely due to the cumulative effect of these compounds acting synergistically80.

Antibacterial activity

Disc diffusion

The efficacy of the mushroom water and methanol extracts against bacterial strains was evaluated using a disc diffusion assay. The experiment focused on five bacterial strains, Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. typhi, P. vulgaris), with the mushroom extracts applied at a concentration of 40 mg/mL. The antibacterial effects of water and methanol extracts were compared against ampicillin (10 µg/disc) as a positive control and 10% DMSO as a negative control. The zones of inhibition (ZOIs) caused by ampicillin were larger and more distinct than those caused by the extracts. Figure 4; Tables 7 and 8 present the results of studying the average ZOIs in millimetres and summarizes the antibacterial effects of mushroom extracts. Following a 24-hour incubation period, all mushroom extracts, effectively inhibited the growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria resulting in them forming different ZOIs. When exposing bacteria to different mushroom extracts treatment at a concentration of 40 mg/mL, significant suppression of microbial growth was noted, leading to zone diameters spanning from 10.20 to 25.60 mm. When the effect of mushroom extracts on the tested bacteria was evaluated in general, it was observed that the methanol extracts provided the highest inhibition. Accordingly, the maximum mean ZOI was measured as 25.60 mm with ECME on K. pneumoniae. In addition, a wide range of activity was also observed on other bacteria tested with ECWE and the minimum mean ZOI was determined on E. coli bacteria with 13.00 mm (p < 0.05). The strong antibacterial activity of ECME was followed by the application EGWE, which provided an inhibition zone of 16.15 on E. coli, the most resistant to the extracts among the tested microorganisms. The results showed that S. aureus was more susceptible to all tested extracts, with at least one extract from this mushroom causing significant zones of inhibition against bacteria strains and exhibiting notable antibacterial activity. The fact that S. aureus, the only Gram-positive among the bacteria tested, was more susceptible to the extracts reflects a known situation where gram-negative bacteria are generally more resistant to antibacterial than Gram-positive ones. The greater susceptibility of S. aureus (a Gram-positive bacterium) compared to Gram-negative bacteria is consistent with existing literature and can be attributed to structural differences in their cell envelopes. Gram-negative bacteria possess an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides, which acts as a permeability barrier and limits the penetration of many antibacterial agents. In contrast, Gram-positive bacteria lack this outer membrane, allowing easier access of bioactive compounds to the peptidoglycan layer and underlying cellular targets81,82. These structural distinctions are crucial in determining the intrinsic resistance or susceptibility of bacterial species to various natural extracts.

Fig. 4.

Antibacterial activities of mushroom extracts, ampicillin (AMP) (10 µg/disc) as positive control, DMSO (10%) as negative control (all the experiments were performed in triplicate). ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Table 7.

The zones of Inhibition (ZOIs) diameters of the methanol extracts of mushrooms on test bacteria.

| ZOI (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | Positive control | Methanol extracts (40 mg/mL) | |||

| Pathogenic bacteria | DMSO (10%) | Ampicillin (10 µg/disc) | E. mutabilis | E. granulatus | E. cyanosporus |

| P. vulgaris | ND | 31.20 ± 0.52a | 14.20 ± 0.10c | 24.00 ± 0.10a | 21.50 ± 0.30c |

| S. typhi | ND | 40.50 ± 0.30b | ND | 16.10 ± 0.15d | 22.42 ± 0.25b |

| K. pneumoniae | ND | 32.40 ± 0.35c | 21.15 ± 0.20a | 23.00 ± 0.10b | 25.60 ± 0.20a |

| E. coli | ND | 33.15 ± 0.20a | 10.20 ± 0.15d | 14.20 ± 0.18e | 14.80 ± 0.15d |

| S. aureus | ND | 33.45 ± 0.25a | 20.50 ± 0.55b | 18.80 ± 0.70c | 25.50 ± 0.20a |

ND: Not determined. abcde Means with the different letters in the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Table 8.

The zones of Inhibition (ZOIs) diameters of the water extracts of mushrooms on test bacteria.

| ZOI (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | Positive control | Water extracts (40 mg/mL) | |||

| Pathogenic bacteria | DMSO (10%) | Ampicillin (10 µg/disc) | E. mutabilis | E. granulatus | E. cyanosporus |

| P. vulgaris | ND | 33.15 ± 1.40a | 18.00 ± 0.56a | 15.46 ± 0.50d | 17.80 ± 0.44c |

| S. typhi | ND | 31.00 ± 0.55b | ND | ND | 14.50 ± 0.20d |

| K. pneumoniae | ND | 30.10 ± 0.25c | ND | 18.20 ± 0.15b | 20.50 ± 0.40a |

| E. coli | ND | 33.35 ± 0.40a | 15.00 ± 0.30b | 16.15 ± 0.42c | 13.00 ± 0.30e |

| S. aureus | ND | 33.24 ± 0.20a | 13.80 ± 0.85c | 22.50 ± 0.20a | 19.52 ± 0.15b |

ND: Not determined. abcde Means with the different letters in the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

The findings show that the mushroom used in this study contains various antibacterial compounds and has broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. This activity, especially in methanol extracts, is likely due to bioactive compounds. These results suggest the mushroom could be a useful biomedical resource, similar to those reported in earlier studies83,84. The antibacterial activity observed in the mushroom extracts may be attributed to the presence of various bioactive compounds with known antimicrobial properties. Several studies have reported that phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and certain polysaccharides found in mushrooms can disrupt bacterial cell membranes, interfere with protein synthesis, or inhibit essential enzymatic pathways. Specifically, phenolic compounds can cause cell wall damage by increasing membrane permeability and inducing leakage of intracellular contents, ultimately leading to cell death. Flavonoids may inhibit nucleic acid synthesis and bind to bacterial enzymes, reducing their activity85,86. Although the exact mechanisms in our samples remain to be confirmed, the high levels of phenolic acids and flavonoids detected by HPLC in E. mutabilis and E. granulatus suggest that these compounds likely play a significant role in the antibacterial effects observed.

With the increasing antibiotic resistance in bacteria, there is a growing demand for new nutraceuticals and antibacterial agents. Pathogens such as Klebsiella spp., E. coli, Pseudomonas spp., and Proteus spp. have shown resistance to commercial antibiotics87. Mushrooms, rich in bioactive compounds, may offer a natural alternative for developing new antimicrobials88. The antibacterial effects of mushroom extracts depend on factors such as mushroom species, cultivation conditions, extraction methods, and evaluation techniques89. Several studies have reported that extracts from different mushroom species show antibacterial activity against various pathogens90–92.

The results demonstrated that all the tested mushroom extracts exhibited inhibitory effects on bacterial growth, with the diameters of the inhibition zones exhibiting variability. To our knowledge, this is the first report to focus on screening the antibacterialproperties of these three edible mushroom extracts. Additional research is needed to isolate and identify the specific compounds responsible for these properties.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The MIC and MBC values of six different mushroom extracts (ECWE, EMWE, EGWE, ECME, EGME, and EMME) were determined against five pathogenic bacterial strains, including E. coli, P. vulgaris, K. pneumoniae, S. typhi, and S. aureus. Differences in antibacterial activity among the extracts, comparative MIC and MBC values among the tested bacterial strains are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

MIC and MBC values of the mushrooms extracts against tested bacterial strains.

| Median MIC/Median MBC (mg/mL); MBC/MIC ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | E. coli | P. vulgaris | K. pneumoniae | S. typhi | S. aureus |

| ECME | 1.25/1.25; 1.0 | 1.25/2.50; 2.0 | 0.625/1.25; 2.0 | 1.25/2.50; 2.0 | 5/5; 1.0 |

| ECWE | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 1.25/2.50; 2.0 | 1.25/2.50; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 |

| EGME | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 1.25/2.50; 2.0 | 0.625/1.25; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 |

| EGWE | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 1.25/2.50; 2.0 | 5.00/10; 2.0 | 5.00/10.00; 2.0 |

| EMME | 2.50/2.50; 1.0 | 1.25/2.50; 2.0 | 0.312/0.625; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 |

| EMWE | 5.00/10.00; 2.0 | 5.00/10.00; 2.0 | 5.00/10.00; 2.0 | 2.50/5.00; 2.0 | 5.00/10.00; 2.0 |

ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis; MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: Minimum bactericidal concentration.

MIC values ranged between 0.312 mg/mL and 5.00 mg/mL, while MBC values varied from 0.625 mg/mL to 10.00 mg/mL across the tested samples. Notably, all extracts exhibited bactericidal activity, as indicated by MBC/MIC ratios of ≤ 2. Among the evaluated samples, ECME and EMME demonstrated the strongest antibacterial effects, with MBC/MIC ratios of 1.0 against E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus, suggesting effective bacterial eradication at relatively low concentrations. In contrast, EMWE exhibited comparatively higher MIC and MBC values, indicating lower antibacterial potency. Overall, these findings suggest that certain mushroom extracts, particularly ECME and EMME, possess significant bactericidal potential against multiple pathogenic bacteria. The present study’s findings align with previous research demonstrating the antibacterial potential of mushroom extracts. For instance, methanolic extracts of Coriolus versicolor have exhibited MIC values ranging from 0.625 to 5 mg/mL against Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus and B. cereus, and MBC values between 1.25 and 5 mg/mL, indicating bactericidal activity93. Similarly, extracts from wild mushrooms such as Trametes and Microporus species have shown MIC values between 0.5 and 1.17 mg/mL against S. aureus and K. pneumoniae, with MBC values as low as 0.5 mg/mL, further supporting their strong antibacterial effects94. These studies corroborate our results, where ECME and EMME extracts demonstrated potent bactericidal activity, with MBC/MIC ratios of 1.0 against E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus.

Cytotoxic activity

The previously unreported cytotoxic activity of different extracts of three edible mushrooms on HT-29 and L929 cell lines was evaluated by Alamar blue assay with various concentrations (12.5–400 µg/mL). Findings regarding the cytotoxicity of the mushroom extracts for these cell lines after 24 h of treatment are shown in Fig. 5. According to these results, after 24 h of treatment of water and methanol extracts on cells, caused 3–12% cytotoxic effect even at the lowest concentration applied (12.5 µg/mL) and it has been recorded that the percentage of cytotoxic effect increases in a proportional manner at higher concentrations. Furthermore, it was found that there were significant alterations in the toxicity levels of the mushroom extracts on the cell lines and all methanol extracts caused more cytotoxicity in both cancer and normal cell lines compared to water extracts. Overall, the mushroom extracts exhibited a significant toxic effect on the human colon cancer cell line (HT-29), particularly ECME destroyed approximately 64% (IC50: 141.51 µg/mL) of HT-29 cells at the highest concentration (400 µg/mL). This extract demonstrated more strong inhibitory potential compared to other treatments used in the study, resulting in a significant decrease in the cell viability and proliferation. Thus, E. cyanosporus extract has distinguished itself as a more effective potential anticancer agent compared to the other tested mushroom extracts. The potential anticancer effect of E. cyanosporus extract is likely linked to its rich content of phenolic acids and flavonoids, as identified through HPLC analysis. Compared to the other mushroom species analyzed in this study, E. cyanosporus exhibited a broader and more abundant profile of these bioactive compounds. Phenolic acids such as gallic, caffeic, and ferulic acids, along with flavonoids like quercetin and rutin, are well-documented for their ability to induce apoptosis, inhibit cell proliferation, and modulate redox-sensitive signaling pathways involved in cancer development95,96. Similar anticancer activities have been reported in other phenolic-rich mushrooms, such as Ganoderma lucidum, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Inonotus obliquus, where phenolics and flavonoids were identified as the primary contributors to cytotoxic effects against cancer cell lines86,97. The high content and diversity of these compounds in E. cyanosporus support the hypothesis that its extract may exert anticancer effects through multiple molecular mechanisms.

Fig. 5.

Viability rates in (a) HT-29 human colon cancer and (b) L929 fibroblast cells treated with different extracts from the mushrooms (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3). Values indicated by different letters differ from each other at the level of p < 0.05. ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

ECME, EGME also possess high degree of growth inhibitory potential on HT-29 cells with low IC50 value (IC50: 188.54 µg/mL). According to the heatmap and cluster analysis calculated by considering the IC50 values, the most effective applications on HT-29 cells were ECME, EGME, and EMME, which have a green colour gradient and are under Cluster 1. The EMWE application stood out from the other applications by being placed under Cluster 3 (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6.

Heatmaps and dendrograms based on IC50 values for cytotoxic activities of mushroom extracts on (a, b) HT-29 human colon cancer and (c, d) L929 fibroblast cells (High and low activities were represented by red and green colour, respectively). ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Although ECME and EGME had ~ 50% inhibition against the normal L929 cell line, other mushroom extracts did not show any activity against the normal L929 cell line (> 350 µg/mL). EMME, which demonstrated the lowest toxicity among the methanol extracts tested, was only capable of inhibiting cell growth by 28% (IC50: 275.82 µg/mL) at a concentration of 400 µg/mL (Fig. 5; Tables 10 and 11). According to the heatmap and clustering analyses performed on L929 cells, the four applications (EGME, ECWE, ECME, and EGWE) with the lowest IC50 values attracted attention by being located under a single cluster. Applications EMME and EMWE were placed in separate clusters (Fig. 6c, d).

Table 10.

IC50 values (µg/mL) resulting from cytotoxic activities of the mushroom extracts on HT-29 cells.

| Treatment | IC50 (Limits) | Slope ± Standard error of the mean (Limits) |

|---|---|---|

| ECME | 141.51 (122.11–166.77) | 1.02 ± 0.06 (0.89–1.14) |

| ECWE | 477.97 (350.57–722.60) | 0.74 ± 0.06 (0.61–0.86) |

| EGME | 188.54 (165.06–218.96) | 1.26 ± 0.07 (1.12–1.39) |

| EGWE | 526.71 (410.64–722.63) | 1.02 ± 0.07 (0.87–1.16) |

| EMME | 275.82 (231.11–340.37) | 1.08 ± 0.06 (0.95–1.22) |

| EMWE | 1142.53 (716.81–2237.12) | 0.67 ± 0.06 (0.54–0.81) |

ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Table 11.

IC50 values (µg/mL) resulting from cytotoxic activities of the mushroom extracts on L929 cells.

| Treatment | IC50 (Limits) | Slope ± Standard error of the mean (Limits) |

|---|---|---|

| ECME | 226.95 (185.59–289.68) | 0.86 ± 0.06 (0.73–0.98) |

| ECWE | 412.13 (313.83–587.10) | 0.80 ± 0.06 (0.67–0.93) |

| EGME | 336.94 (275.39–431.15) | 1.03 ± 0.07 (0.89–1.16) |

| EGWE | 693.31 (514.78–1023.88) | 0.95 ± 0.07 (0.80–1.10) |

| EMME | 1493.18 (952.41–2813.82) | 0.83 ± 0.07 (0.68–0.99) |

| EMWE | 2352.56 (1352.25–5298.48) | 0.78 ± 0.08 (0.63–0.94) |

ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

Although preliminary in vitro or ex vivo studies on Elaphomyces species are limited, existing evidence suggests potential biological activity. Previous studies have demonstrated that various mushroom extracts exhibit significant anticancer activities against multiple cancer types, including breast, lung, stomach, and cervical cancers98–100. These effects are largely attributed to the presence of bioactive secondary metabolites found in mushrooms, which are known to possess a wide range of pharmacological properties such as hepatoprotective, anti-osteoporotic, antioxidant, and anticancer activities101,102. The IC₅₀ values of water, ethanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, and n-hexane extracts of Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus sajor-caju, Agaricus bisporus, and Agaricus campestris against various cancer cell lines ranged from 1 to 50 µg/mL103, whereas the IC₅₀ value of Donkioporiella melleaextract was around 1000 µg/mL104. In the present study, both ECME and EMME showed notable cytotoxic effects against HT-29 colon cancer cells. In evaluating the cytotoxic potential of the mushroom extracts, it is essential to consider the biological relevance of the observed IC₅₀ values. Although the extracts exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxic effects, their IC₅₀ values were higher than those typically reported for standard chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin or cisplatin, which generally show activity within the low micromolar range against HT-29 colon cancer cells. For instance, doxorubicin has been reported to have IC₅₀ values of 2.75 µM105 and 0.058 µM106. Similarly, cisplatin has shown IC₅₀ values of 167.66 µM107 and > 100 µM108 in HT-29 cells. This indicates that while the extracts may contain bioactive compounds with anticancer potential, they are likely less potent than conventional drugs in their crude form. However, natural extracts offer advantages such as lower toxicity, multi-targeted action, and potential for synergistic effects.

These findings provide preliminary evidence that ECME and EMME contain compounds with potential anticancer activity. Importantly, their use as natural, supportive agents alongside conventional chemotherapy could help to enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing the adverse effects commonly associated with anticancer drugs. Further research, including mechanistic studies and in vivo evaluations, is necessary to better understand their mode of action and to confirm their therapeutic potential.

The cytotoxic activity of the extracts is primarily due to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which induce oxidative stress and activate apoptotic pathways109. Phenolic compounds and flavonoids in the extracts cause mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to cytochrome c release and caspase activation, ultimately resulting in cell death. Additionally, ROS-induced DNA damage and cell cycle disruption play a role in the cytotoxic effects. The choice of solvent, especially methanol, enhances the extraction of these bioactive compounds, thereby increasing their cytotoxic potential110.

Conclusions

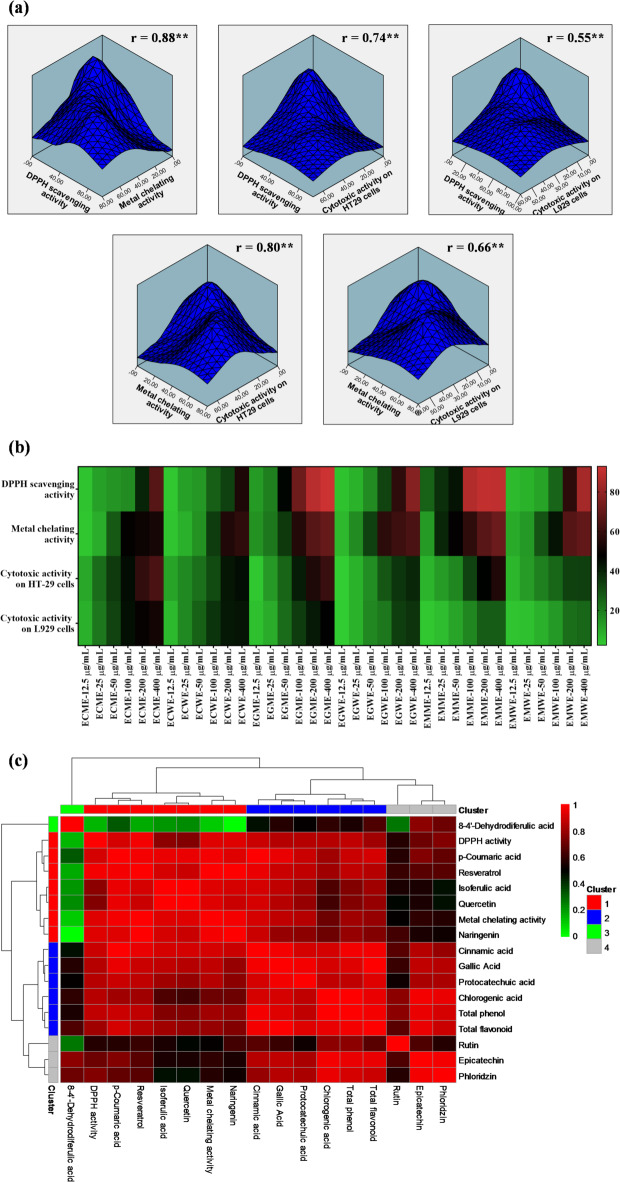

A comprehensive 3-D analysis was employed to elucidate the correlations between the activities of various extracts. The analysis revealed a statistically significant positive correlation (r = 0.88, p < 0.01) between DPPH radical scavenging and metal ion chelation activities, collectively referred to as antioxidant activity. Additionally, a significant positive correlation (r = 0.74, p < 0.01) was observed between DPPH scavenging activity and cytotoxic effects on cancerous cells. These findings indicate that the antioxidant potential of the extracts is closely associated with their cytotoxic effects on cellular models. The high correlation coefficients underscore the strong linkage between DPPH radical scavenging, metal ion chelation, and the cytotoxic response in HT29 cells, suggesting that these cells exhibit heightened sensitivity to antioxidant activity (Fig. 7a).

Fig. 7.

(a) 3-D density analysis was performed to assess the DPPH scavenging, metal-chelating, and cytotoxic activities of the extracts. During this evaluation, correlation coefficients (r) were calculated, with a double asterisk (**) denoting statistical significance at the 0.01 level. (b) Heatmap illustrated the percentages of DPPH scavenging, metal chelating, and cytotoxic activities of the mushroom extracts, with high activity shown in red and low activity in green. (c) The correlations between antioxidant activity, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and phenolic compounds of the extracts were analyzed using HPLC. ECME: Methanol extract of E. cyanosporus; ECWE: Water extract of E. cyanosporus; EGME: Methanol extract of E. granulatus; EGWE: Water extract of E. granulatus; EMME: Methanol extract of E. mutabilis; EMWE: Water extract of E. mutabilis.

According to the general heatmap analysis based on antioxidant and cytotoxic activities, we evaluated the clustering of the samples across different concentrations to understand their biological relevance. The colour gradients in the heatmap reflect the level of activity, with red indicating high activity and green indicating low activity. Notably, the samples treated at 200 µg/mL and 400 µg/mL formed a distinct cluster, particularly in DPPH scavenging and metal chelating assays, indicating strong antioxidant potential at these concentrations. Furthermore, within this cluster, the EMME extract was distinguished by a favorable biological activity profile: it exhibited high cytotoxic activity against HT-29 cancer cells and low cytotoxicity against L929 normal cells, as well as strong antioxidant properties. This selective bioactivity suggests that the extraction process using methanol for E. mutabilis was efficient in concentrating bioactive compounds with both therapeutic potential and safety. The clustering pattern thus implies that both extraction solvent and concentration significantly influenced the biological performance of the extracts. In addition, EMME also showed the highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents, which may explain its superior antioxidant and selective cytotoxic effects (Fig. 7b).

The relationship between the phenolic compounds identified through HPLC analysis and the antioxidant mechanisms of the extracts was determined using correlation analysis. Additionally, we assessed and examined the proximity of these variables within different clusters. According to the analysis, antioxidant and metal chelating activities showed a strong correlation and were grouped within the same cluster. The phenolic compounds associated with Cluster 1, as revealed by the HPLC analysis, included p-coumaric acid, resveratrol, isoferulic acid, quercetin, and naringenin. Compounds related to total phenolic and flavonoid content, which were grouped in the same cluster, included cinnamic acid, gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, and chlorogenic acid (Fig. 7c).

In conclusion, these findings suggest that the mushrooms (E. cyanosporus, E. granulatus, and E. mutabilis) we tested may provide multifaceted health benefits and can be used as valuable natural resources in the pharmaceutical and health supplement industries. While the concluding remarks suggest that further studies are needed to identify the bioactive compounds responsible for the observed activities, it is important to consider specific methodologies for advancing this research. Since HPLC has already been utilized to identify key compounds, the next step could involve bioassay-guided fractionation to isolate individual bioactive components from the extracts. This approach would allow for testing the isolated fractions for specific biological activities, helping to pinpoint the most active compounds. Additionally, molecular docking studies could complement this by modeling the interactions between these compounds and potential target proteins, providing deeper insights into their mechanisms of action. These strategies would help validate the bioactive compounds identified through HPLC and further elucidate their therapeutic potential.

Given that the mushrooms used in this study are not suitable for direct consumption, the extracts would be more appropriate for development into pharmaceutical formulations rather than dietary supplements. The bioactive compounds identified in the extracts, such as phenolic acids and flavonoids, exhibit significant biological activities, including antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer effects. These properties could be harnessed in the formulation of topical applications, oral capsules, or injection-based therapies, where controlled doses and targeted delivery systems can enhance their therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, further research into the pharmacokinetics and safety of these compounds is essential before advancing to clinical formulations. Therefore, the extracts show promising potential for pharmaceutical applications, particularly in the development of novel, bioactive therapeutics.

Materials and methods

Collection and identification of mushroom samples

Elaphomyces cyanosporus (Rize, Ardeşen, Kirazlık village, 41°07′N 41°05′E, Y.Uzun 5207), E. granulatus (Trabzon, Tonya, İskenderli village, 40°55′N-39°14′E, Y.Uzun 5464), and E. mutabilis (Rize, Ardeşen, Ortaalan village, 41.17°N 41.10°E, Y.Uzun 5748) specimens were collected from Türkiye. Fruit bodies were photographed in their natural habitats, and essential morphological and ecological characteristics were documented (Fig. 8). The specimens were then placed in paper bags and transferred to the fungarium, where they were dried in an air-conditioned room and prepared for fungarium storage. Identification of the samples was done using various literature sources21,111,112.

Fig. 8.

Images of (a) E. cyanosporus, (b) E. granulatus, and (c) E. mutabilis in their natural habitat.

Preparation of mushroom extract

Following a gentle heat treatment under a mild heat evaporator, the entirety of mushroom samples, underwent pulverization using liquid nitrogen and a mortar. These powder samples (5 g) were then extracted separately in water and methanol solvents with a Soxhlet extractor setup for 2 days. The extract was purified using Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the remaining solvent was evaporated in a rotary evaporator at 40 °C until dryness, followed by lyophilization to yield ultra-dry powders. The residues were stored in a sterile container at 4 °C until analysis113,114.

Determination and measurement of primary phenolic compounds using HPLC

Acetonitrile (HPLC grade, ≥ 99.9%), methanol (HPLC grade, ≥ 99.8%), acetic acid (HPLC grade, ≥ 99.8%), and ultra-pure water (HPLC grade) were obtained, along with standards for chlorogenic acid, cinnamic acid, p-coumaric acid, 8 − 4’-dehydrodiferulic acid, 4,2’-dihydroxychalcone 4-glucoside, epicatechin, gallic acid, isoferulic acid, naringenin, phloridzin, protocatechuic acid, quercetin, resveratrol, and rutin from Sigma Chemical Co. (USA). Each compound was prepared as a standard stock solution at a concentration of 500 mg/L in methanol and stored at 4 °C in the dark. Serial dilutions were made daily using a 1:1 (v/v) methanol/water solution to create standard working solutions.

The HPLC system (Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity) was outfitted with a column oven (G1316A), an auto-sampler (G1329B), a pump (G1311C), an ACE 5 C18 analytical column (5 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 4.60 mm), and a diode array detector (G1311D) capable of reading wavelengths from 190 to 800 nm. The sample injection volume was set to 20 µL, with the oven temperature at 25 °C and a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The mobile phase gradient consisted of water with acetic acid (98:2, v/v %) as phase A, acetonitrile with acetic acid (99.5:0.5, v/v %) as phase B, and acetonitrile as phase C. The gradient program was run as follows: 90% (A) and 10% (B) from 0 to 30 min, 80% (A) and 20% (B) from 30 to 60 min, 55% (A) and 45% (B) from 60 to 62 min, 40% (B) and 60% (C) from 62 to 77 min, and 90% (A) and 10% (B) from 77 to 80 min. Following each run, initial mobile phase conditions were held for 5 min to stabilize the column.

Determination of antioxidant activity

Total phenol content

To determine the total phenolic content of mushroom extracts in methanol and water, gallic acid was used as a standard. Methanol and water extracts (400 µg/mL) along with the standard were placed in microplate wells at 20 µL each. Next, 20 µL of 2 N Folin reagent was added, and the mixture was pipetted and incubated in the dark for 3 min. Then, 20 µL of 35% (w/v) sodium carbonate and 140 µL of dH2O were added, followed by another 10-minute incubation in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 725 nm, and results were calculated in gallic acid equivalents (GAE) based on a standard calibration curve with gallic acid113.

Total flavonoid content

For measuring the total flavonoid content in methanol and water extracts from mushrooms, quercetin served as the standard. A 50 µL portion of each extract (400 µg/mL) and standard was added to microplate wells. Then, 215 µL of 80% ethyl alcohol, 5 µL of 10% aluminum nitrate, and 5 µL of 1 M potassium acetate were added to the wells. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 40 min. Absorbance was read at 415 nm, and flavonoid content was calculated in quercetin equivalents (QE) using a standard calibration curve based on quercetin113.

Free radical scavenging activity

For assessing the DPPH scavenging activity of methanol and water extracts from mushrooms, extracts were prepared at final concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 µg/mL in microplate wells. Following the method, 20 µL of each extract was added to the wells, along with 180 µL of 0.06 mM DPPH in methanol. The reduction of DPPH free radicals was evaluated by measuring absorbance at 517 nm after a 60-minute incubation in the dark. The free radical scavenging activity of the extracts was calculated as a percentage using the specified formula113:

Metal chelating activity

To evaluate the metal chelating activity of methanol and water extracts from mushrooms, the extracts were tested at final concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 µg/mL in the microplate wells. According to the procedure, 50 µL of each extract was added to the wells, followed by 10 µL of 5 mM ferrozine, 5 µL of 2 mM FeCl2, and 185 µL of methanol. The mixture was then allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 min. Spectrophotometric measurements were taken at 562 nm, and the metal chelating activities of the extracts were calculated as a percentage using the designated formula113:

Determination of antibacterial activity

Disc diffusion assay

The antibacterial activity of two different extracts of three mushrooms (40 mg/mL) were evaluated against pathogenic microorganisms (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 70063, Salmonella typhi ATCC 14028, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 426) by the disc diffusion assay115. In the experimental procedure, fresh overnight cultures of five different pathogenic microorganisms in Mueller-Hinton broth were seeded separately on Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates. Mushroom extracts (40 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving them in 10% DMSO. Following, sterile discs (diameter of 6 mm) were placed onto the surfaces of MHA plates that had been previously inoculated with the respective pathogenic microorganisms at concentrations of 108−109 CFU/mL. Ampicillin (10 µg/disc) and 10% DMSO loaded discs were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After the incubation period, the diameter of the zone of inhibition (ZOI) surrounding the discs, a quantitative indicator of the antibacterial properties of the mushroom extracts, was measured in millimetres (mm). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

MIC and MBC determination

MIC, defined as the lowest concentration at which an antimicrobial agent inhibits visible bacterial growth, was determined using the broth microdilution technique. Similarly, MBC, representing the concentration necessary to achieve complete bacterial killing, was evaluated by transferring aliquots from non-turbid wells onto agar plates. Following this, MIC and MBC assessments of sporopollenin and the synthesized microcapsule formulations were performed using a resazurin-based reduction assay, by previously described protocols116, with slight modifications to the method117. The antibacterial evaluation was conducted against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29,213, Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 70,063, Salmonella typhi ATCC 14,028, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 426. Each bacterial strain was cultured overnight in Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) (Merck, Germany) at 37 °C with agitation at 180 rpm, and the bacterial suspensions were adjusted to match a 0.5 McFarland standard. Test samples were dissolved in 1% DMSO to prepare a stock solution of 10 mg/mL. Subsequently, bacterial suspensions were diluted to a final concentration of 10⁵–10⁶ CFU/mL in MHB and inoculated into 96-well microplates (10 µL/well). Serial two-fold dilutions of the samples were prepared in MHB to yield final concentrations ranging from 0.156 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL (100 µL/well). Plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. A negative control group, containing no DMSO, was included to verify that DMSO did not influence bacterial growth. After incubation, 15 µL of Alamar Blue® reagent was added to each well, followed by an additional 2 h incubation at 37 °C. The MIC value was recorded as the lowest sample concentration, which prevented the resazurin color shift from blue to pink, indicating inhibition of bacterial metabolic activity.

Determination of cytotoxic activity

Cell culture

In vitro cytotoxicity investigation, the HT-29 human colon cancer cell line and the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line employed as experimental models. The cell lines used in this study were obtained from the existing cell culture collection of our laboratory at the Department of Biology, Kamil Özdağ Faculty of Science, Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey University, Karaman, Türkiye. These cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (100 IU/mL/100 µg/mL), and 0.01% gentamicin. The cell lines were incubated in a humidified environment containing 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cell lines grown until reaching 80–90% confluency was sub-cultured by standard trypsinization procedure118.

Alamar blue assay

The cytotoxicity of the mushroom extracts was evaluated by Alamar Blue®assay (Sigma-Aldrich) on HT-29 and L929 cell lines. The samples to be test were prepared as a stock solution in DMSO at a concentration of 40 mg/mL, ensuring that the final concentration of DMSO in the cell culture medium did not exceed 0.1%119. The cells were plated into 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and incubated under standard conditions with 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. Following fixation, each well was rinsed twice with 1xPBS. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to various concentrations of mushroom extracts (12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 µg/mL) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After the incubation period, Alamar Blue reagent (1:10, v/v) was added to the microplate wells and following 4 h of incubation, absorbance readings were taken using a spectrophotometric microplate reader (Multiscan Go, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at wavelengths of 570 nm and 600 nm. The negative control was a culture medium containing only 0.1% DMSO. The viability of cells in each sample was determined by comparing it to the viability of control cells, and the percentage of cell viability was calculated accordingly.

Statistical analyses

Parametric statistical tests were used in the analysis. The activities of the extracts were evaluated through a one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test. Additionally, Probit regression analysis was applied to calculate the median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values. To examine the relationships among DPPH scavenging, metal chelating, and cytotoxic activities across different extracts, three-dimensional (3D) density analysis was performed. These statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 27.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Additionally, heatmap and hierarchical cluster analyses, employing Ward’s minimum variance method, were used to identify similarities and differences among DPPH scavenging, metal chelating, cytotoxic activities, and HPLC results. These analyses were executed in the Rstudio console with R software (version 4.1.0).

Author contributions

F.U. and B.E. designed the experiments. Y.U. and A.K. collected mushroom samples and made their identifications. All authors carried out the experiments. F.U., B.E., and H.S.K analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The data sets analyzed in the current study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Singh, D. et al. In Silico molecular screening of bioactive natural compounds of Rosemary essential oil and extracts for Pharmacological potentials against rhinoviruses. Sci. Rep.14, 17426 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chroho, M., Bailly, C. & Bouissane, L. Ethnobotanical uses and Pharmacological activities of Moroccan Ephedra species. Planta Med.90, 336–352 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thepmalee, C. et al. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using cordycepin and Cordyceps militaris extract to sensitize cancer cells and modulate immune responses. Sci. Rep.14, 21907 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oluwole, O., Fernando, W. B., Lumanlan, J., Ademuyiwa, O. & Jayasena, V. Role of phenolic acid, tannins, stilbenes, lignans and flavonoids in human health–a review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol.57, 6326–6335 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karatas, M., Dogan, M., Emsen, B. & Aasim, M. Determination of in vitro free radical scavenging activities of various extracts from in vitro propagated Ceratophyllum demersum L. Fresenius Environ. Bull.24, 2946–2952 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, T. et al. Natural products for combating multidrug resistance in cancer. Pharmacol. Res.202, 107099 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsayed, W., El-Shafie, L., Hassan, M. K., Farag, M. A. & El-Khamisy, S. F. Isoeugenol is a selective potentiator of camptothecin cytotoxicity in vertebrate cells lacking TDP1. Sci. Rep.6, 26626 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stasiłowicz-Krzemień, A., Gościniak, A., Formanowicz, D. & Cielecka-Piontek, J. Natural guardians: natural compounds as radioprotectors in cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 6937 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali, M. et al. Recent advance of herbal medicines in cancer-a molecular approach. Heliyon9, e13684 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Steenwijk, H. P., Bast, A. & De Boer, A. Immunomodulating effects of fungal beta-glucans: from traditional use to medicine. Nutrients13, 1333 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu, J. et al. Effects of dietary Brassica rapa L. polysaccharide on growth performance, immune and antioxidant functions and intestinal flora of yellow-feathered quail. Sci. Rep.14, 28252 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia, J., Rodrigues, F., Saavedra, M. J., Nunes, F. M. & Marques, G. Bioactive polysaccharides from medicinal mushrooms: a review on their isolation, structural characteristics and antitumor activity. Food Biosci.49, 101955 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh, S. K., Pandey, K., Ghosh, M. & Sur, P. K. Mycochemistry, antioxidant, anticancer activity, and molecular Docking of compounds of F12 of Ethyl acetate extract of Astraeus Asiaticus with BcL2 and caspase 3. Sci. Rep.15, 4313 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trivedi, R. & Upadhyay, T. K. Preparation, characterization and antioxidant and anticancerous potential of Quercetin loaded β-glucan particles derived from mushroom and yeast. Sci. Rep.14, 16047 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assemie, A. & Abaya, G. The effect of edible mushroom on health and their biochemistry. Int. J. Microbiol. 8744788 (2022). (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Gruendemann, C. et al. Effects of Inonotus hispidus extracts and compounds on human immunocompetent cells. Planta Med.82, 1359–1367 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdelshafy, A. M. et al. A comprehensive review on phenolic compounds from edible mushrooms: occurrence, biological activity, application and future prospective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.62, 6204–6224 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, H., Fu, Y., Song, F. & Xu, X. Recent updates on the antimicrobial compounds from marine-derived Penicillium fungi. Chem. Biodivers.20, e202301278 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, J. H. et al. Antimicrobial efficacy of edible mushroom extracts: assessment of fungal resistance. Appl. Sci.12, 4591 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amr, M. et al. Utilization of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles from Agaricus bisporus extract for food safety application: synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial efficacy, and toxicological assessment. Sci. Rep.13, 15048 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paz, A. et al. The genus Elaphomyces (Ascomycota, Eurotiales): a ribosomal DNA-based phylogeny and revised systematics of European ‘deer truffles’. Persoonia38, 197–239 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castellano, M. A. & Stephens, R. B. Elaphomyces species (Elaphomycetaceae, Eurotiales) from Bartlett experimental forest, new hampshire, USA. IMA Fungus. 8, 49–63 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trappe, J. et al. Diversity, ecology, and conservation of truffle fungi in forests of the Pacific Northwest. 772US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, (2009).

- 24.Uzun, Y. & Kaya, A. First record of Elaphomyces decipiens for the mycobiota of Turkey. J. Fungus. 12, 134–137 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanikunaite, R., Trappe, J. M., Khan, S. L. & Ross, S. A. Evaluation of therapeutic activity of hypogeous ascomycetes and basidiomycetes from North America. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms. 9, 7–14 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanikunaite, R., Khan, S. I., Trappe, J. M. & Ross, S. A. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory and antioxidant compounds from the truffle Elaphomyces granulatus. Phyther Res.23, 575–578 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anusiya, G. et al. A review of the therapeutic and biological effects of edible and wild mushrooms. Bioengineered12, 11239–11268 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcus, Y. Extraction by subcritical and supercritical water, methanol, ethanol and their mixtures. Separations5, 4 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plaskova, A. & Mlcek, J. New insights of the application of water or ethanol-water plant extract rich in active compounds in food. Front. Nutr.10, 1118761 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tranquilino-Rodríguez, E. et al. Optimization in the extraction of polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant activity from Opuntia ficus‐indica using response surface methodology. J. Food Process. Preserv. 44, e14485 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borrás-Enríquez, A. J., Reyes-Ventura, E., Villanueva-Rodríguez, S. J. & Moreno-Vilet, L. Effect of ultrasound-assisted extraction parameters on total polyphenols and its antioxidant activity from Mango residues (Mangifera indica L. var. Manililla) Separations. 8, 94 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allay, A. et al. Enhancing bioactive compound extractability and antioxidant properties in hemp seed oil using a ternary mixture approach of Polar and non-polar solvents. Ind. Crops Prod.219, 119090 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fioroni, N. et al. Antioxidant capacity of Polar and non-polar extracts of four African green leafy vegetables and correlation with polyphenol and carotenoid contents. Antioxidants12, 1726 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atila, F. et al. Effect of phenolic-rich forest and Agri-food wastes on yield, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of Ganoderma lucidum. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14, 25811–25821 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gąsecka, M., Mleczek, M., Siwulski, M. & Niedzielski, P. Phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of pleurotus ostreatus and pleurotus eryngii enriched with selenium and zinc. Eur. Food Res. Technol.242, 723–732 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erbiai, E. H. et al. Antioxidant properties, bioactive compounds contents, and chemical characterization of two wild edible mushroom species from morocco: Paralepista flaccida (Sowerby) Vizzini and Lepista nuda (Bull.) Cooke. Molecules28, 1123 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu, M. et al. LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS characterization of phenolic compounds in common commercial mushrooms and their potential antioxidant activities. Processes11, 1711 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elsayed, E. A., El Enshasy, H., Wadaan, M. A. M. & Aziz, R. Mushrooms: a potential natural source of anti-inflammatory compounds for medical applications. Mediators Inflamm. 805841 (2014). (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Sajon, S. R., Sana, S., Rana, S., Rahman, S. M. M. & Nishi, Z. M. Mushrooms: natural factory of anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and nutrition. J. Pharmacogn Phytochem. 7, 464–475 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ouachinou, J. M. A. S. et al. Variation of secondary metabolite contents and activities against bovine diarrheal pathogens among Zygophyllaceae species in Benin and implications for conservation. Planta Med.88, 292–299 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawat, P. et al. Bone fracture-healing properties and UPLC-MS analysis of an enriched flavonoid fraction from Oxystelma esculentum. Planta Med.90, 96–110 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knežević, A. et al. Antioxidative, antifungal, cytotoxic and antineurodegenerative activity of selected Trametes species from Serbia. PLoS One. 13, e0203064 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baptista, F. et al. Nutraceutical potential of lentinula edodes’ spent mushroom substrate: a comprehensive study on phenolic composition, antioxidant activity, and antibacterial effects. J. Fungi. 9, 1200 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chopra, H. et al. Narrative review: bioactive potential of various mushrooms as the treasure of versatile therapeutic natural product. J. Fungi. 7, 728 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nnemolisa, S. C. et al. Antidiabetic and antioxidant potentials of Pleurotus ostreatus-derived compounds: an in vitro and in Silico approach. Food Chem. Adv.4, 100639 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kachlicki, P., Piasecka, A., Stobiecki, M. & Marczak, Ł. Structural characterization of flavonoid glycoconjugates and their derivatives with mass spectrometric techniques. Molecules21, 1494 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parcheta, M. et al. Recent developments in effective antioxidants: the structure and antioxidant properties. Mater. (Basel). 14, 1984 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kongpichitchoke, T., Hsu, J. L. & Huang, T. C. Number of hydroxyl groups on the B-ring of flavonoids affects their antioxidant activity and interaction with phorbol ester binding site of PKCδ C1B domain: in vitro and in Silico studies. J. Agric. Food Chem.63, 4580–4586 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osorio-Tobón, J. F. Recent advances and comparisons of conventional and alternative extraction techniques of phenolic compounds. J. Food Sci. Technol.57, 4299–4315 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gil-Martín, E. et al. Influence of the extraction method on the recovery of bioactive phenolic compounds from food industry by-products. Food Chem.378, 131918 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]