Abstract

Ab initio and density functional calculations have been carried out to more fully understand the factors controlling the catalytic activity of the Thermus aquaticus DNA methyltransferase (MTaqI) in the N-methylation at the N6 of an adenine nucleobase. The noncatalyzed reaction was modeled as a methyl transfer from trimethylsulfonium to the N6 of adenine. Activation barriers of 32.0 kcal/mol and 24.0 kcal/mol were predicted for the noncatalyzed reaction in the gas phase by MP2/6–31+G(d,p)//HF/6–31+G(d,p) and B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) calculations, respectively. Calculations performed to evaluate the effect of substrate positioning in the active site of MTaqI on the reaction determine the barrier to be 23.4 kcal/mol and 17.3 kcal/mol for the MP2/6–31+G(d,p)//HF/6–31+G(d,p) and B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) gas phase calculations, respectively. The effect of hydrogen bonding between the N6 of adenine and the terminal oxygen of Asn-105 on the activation barrier was also studied. A formamide molecule was modeled into the system to mimic the function of active site residue Asn-105. The activation barrier for this reaction was found to be 21.8 kcal/mol and 15.8 kcal/mol as determined from the MP2/6–31+G(d,p)//HF/6–31+G(d,p) and B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) calculations, respectively. This result predicts a contribution of less than 2 kcal/mol to the lowering of the activation barrier from amide hydrogen bonding between formamide and N6 of adenine. Comparison of the reaction coordinates suggest that it is not the hydrogen bonding of the Asn-105 that lends to the catalytic prowess of the enzyme since the organization of the substrates in the active site of the enzyme has a far greater effect on reducing the activation barrier. The results also suggest a stepwise mechanism for the removal of the hydrogen from the N6 of adenine as opposed to a concerted reaction in which a proton is abstracted simultaneously with the transfer of the methyl group. The hydrogen on the N6 of the intermediate methyl adenine product is far more acidic than in the reactant complex and may be subsequently abstracted by basic groups in the active site that are too weak to abstract the proton before the full sp3 hybridization of the attacking nitrogen.

Postreplicative methylation of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA is carried out by the S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) cofactor-dependent DNA methyltransferases (Mtases). These enzymes catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from the positively charged sulfur atom in AdoMet to the N6 exocyclic nitrogen of adenine, the C5 pyrimidine ring carbon or the N4 exocyclic nitrogen of cytosine. Methylation is often viewed as an increase in the information content of DNA because it enables the DNA to exist in various forms: unmethylated, fully methylated, and immediately following replication, hemimethylated. DNA Mtases are present in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms and are involved in a myriad of biological processes including DNA mismatch repair (1, 2), replication (3–6), transcriptional regulation (7–11), and gene imprinting (12). DNA methylation in prokaryotes functions primarily in restriction modification (R/M) systems, aiding bacteria in distinguishing between self and foreign DNA (13), but Mtases functioning outside of the R/M system have been found to be essential to the viability and virulence of bacterial cells (14–18). Attention has been given to bacterial DNA Mtases for the obvious possibility of antibiotics, while copious amounts of research has been directed toward the linking of cytosine DNA methylation patterns with various cancers in humans.

A number of crystal structures have been solved that are critical in elucidating the mechanisms the DNA Mtases employ (19–21). A comparison of the catalytic domains observed in these crystal structures reveals a high degree of homology (22). Very recently, the crystal structure of the DNA Mtase from Thermus aquaticus (MTaqI) was solved in complex with a specific DNA sequence and the cofactor analog 5′-deoxy-5′-[2-(amino)ethylthio]adenosine (AETA) (23). Involved in the restriction modification system for T. aquaticus, MTaqI methylates the N6 of adenine within the recognition sequence 5′-TCGA-3′. The protein contains nine amino acid motifs (I-XIII and X) that are conserved across all DNA Mtases and contains distinct N- and C-terminal domains also shared by the other DNA Mtases (24). The N-terminal domain contains the catalytic residues. A cleft in the enzyme sufficient to accommodate the DNA substrate arises as a result of the bilobial structure of the enzyme. Before this recent crystal structure, docking experiments with MTaqI revealed that the distance between the target adenine in the DNA and the methyl group of the cofactor to be 15 Å, suggesting that the adenine needed to be rotated out of the double helix about its phosphodiester bonds to put it in close proximity with the cofactor (25). This base flipping mechanism used by other DNA Mtases was further supported for MTaqI with chemical experiments (26, 27). The crystal structure solved by Goedecke et al. proved unequivocally that MTaqI utilizes the base flipping mechanism to extract the adenine by rotating it into position for direct methyl transfer. This distorted β-DNA form is stabilized by various protein–DNA interactions. The extrahelical adenine is held in position by stabilizing π-stacking interactions with Tyr-108 and Phe-196. Furthermore, Pro-393 makes van der Waals contact with the thymine formerly paired with the rotated adenine and coaxes it into position along the axis of the double helix partly occupying the space vacated by the adenine. This positioning of thymine prevents the adenine from rotating back into its original base paired position. Although this stabilization is vital to the function of the enzyme, it does not explain how the enzyme lowers the activation barrier for the methyl transfer. Experimental evidence indicates that the methyl transfer is the rate-limiting step for MTaqI (28, †).

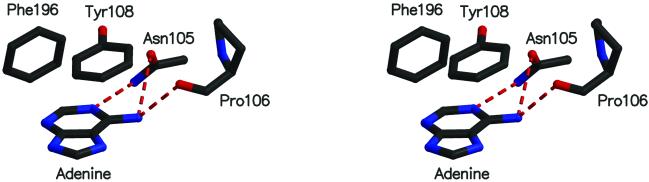

With no general base proximal to the adenine when it is in position to attack the methyl group, the exact catalytic mechanism has remained unclear. It has been proposed that hydrogen bonds from the amino group to both the backbone oxygen of Pro-106 and the terminal oxygen of Asn-105 could contribute to the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme (22–24). The recently solved crystal structure advanced this claim by showing that the two residues are in position below the plane of the adenine to possibly change the hybridization of N6, thus preparing it for nucleophilic attack.

To elucidate the mechanism of the methyl group transfer catalyzed by MTaqI, ab initio and density functional calculations were performed on a system modeled after the enzyme's active site both with and without catalyst.

Methods

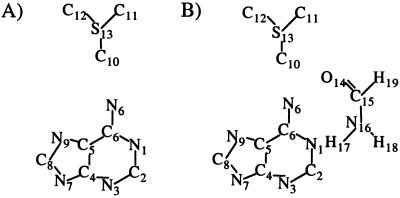

Quantum mechanical calculations were performed on model systems to examine the SN2 transmethylation reaction catalyzed by MTaqI. The methyl donor AdoMet is represented by trimethylsulfonium (TMS) and adenine was used as the nucleophile. The crystal structure solved by Godecke et al. with DNA substrate and inhibitor was used to generate starting structures for the noncatalyzed reaction. AdoMet was positioned on the inhibitor and then TMS was oriented in a manner that mimics the enzyme's positioning of the substrate (Fig. 1). The position of the adenine was dictated by the rotated adenine in the crystal structure. Two different ground states were calculated for the noncatalyzed reaction. One structure was allowed to fully optimize in the gas phase. The other structure is intended to resemble the attack geometry in the active site of MTaqI. To ensure that the general orientation of the active site was preserved during this optimization, the system was constrained. The C6–N6–C10 (110.00°) and N6–C10–S13 (179.00°) angles were constrained in addition to the dihedrals N1–C6–N6–C10 (−90.00°), C6–N6–C10–S13 (0.00°), N6–C10–S13–C11 (120.00°), and N6–C10–S13–C12 (−125.00°) (Fig. 2A). These constraints were only used in the ground state geometry. GAUSSIAN 98 was used for all quantum mechanical calculations (30). Geometry optimizations were performed at the HF/6–31+G(d,p) and B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) levels of theory (31, 32). Zero point energies (ZPE) were obtained from harmonic frequency calculations performed on all of the fully optimized structures. The ZPE were scaled by 0.893 for Hartree–Fock (HF) calculations and 0.980 for density functional theory (DFT) calculations (33, 34). Transition state structures were characterized by one imaginary frequency. To further access the effects of electron correlation, MP2 calculations were performed on all HF optimized structures because DFT energies can underestimate activation barriers (33, 35).

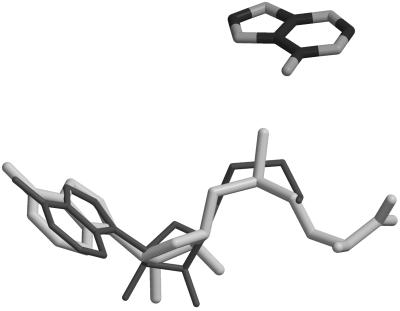

Figure 1.

Superposition of AdoMet on the inhibitor AETA in the active site of MTaqI.

Figure 2.

Atom numbering used in the text for (A) the noncatalyzed reaction and (B) the catalyzed reaction.

To examine the effect of hydrogen bonding between adenine and Asn-105 on the reaction, formamide was used to mimic the amide functionality of Asn-105. Stationary points acquired for the noncatalyzed system were placed in the active site of the enzyme and then formamide was overlaid on the terminal end of Asn-105. Trimethylsulfonium was constrained using the same dihedrals and angles as the noncatalyzed geometry. In addition, dihedrals C2–N1–C15–N16 (−173.85°), N1–N16–C15–O14 (1.90°), and N1–N16–C15–N6 (12.56°) were constrained to ensure formamide maintain the general orientation of the side chain of Asn-105 (Fig. 2B). As with the noncatalyzed reaction, these constraints were imposed only in the ground state calculations. The PM3 semiempirical Hamiltonian was used to initially optimize these structures (36). The final structures from the PM3 calculations were used as starting points for ab initio calculations at the HF/6–31+G(d,p). The structures obtained at the HF level were used as starting structures for optimizations performed at the B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) level of theory and also for single-point energy calculations at the MP2/6–31+G(d,p) level of theory.

Results and Discussion

The Noncatalyzed Reaction.

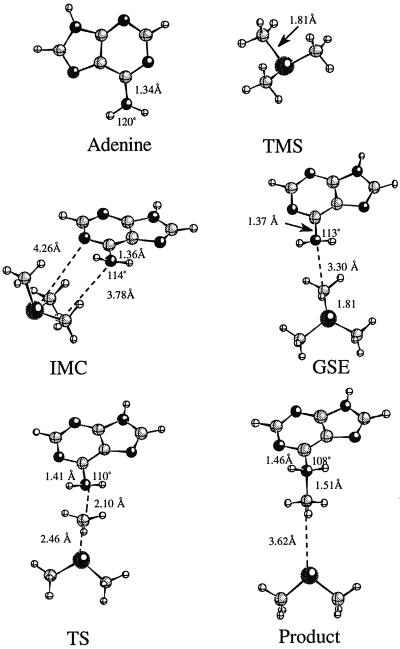

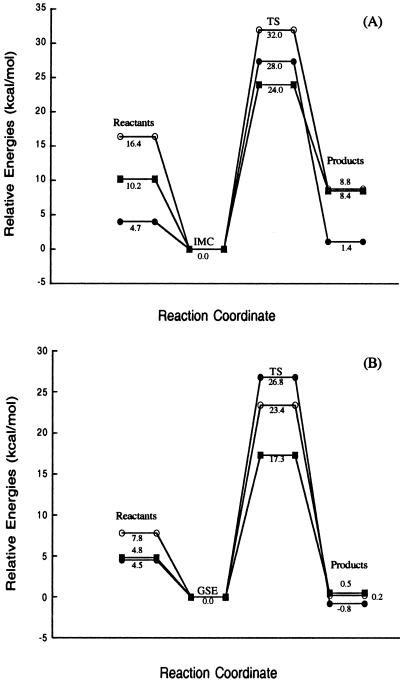

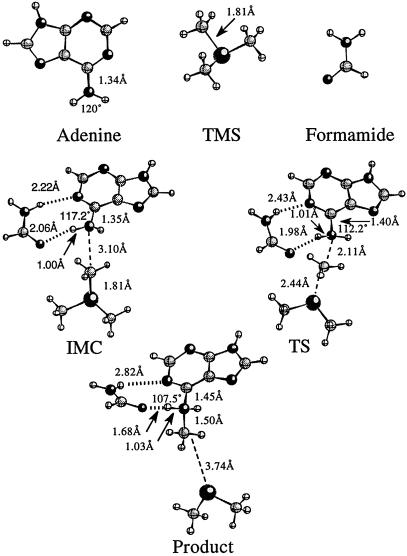

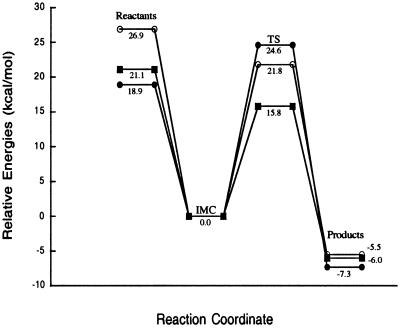

The methyl transfer reaction studied is a one-step SN2 mechanism involving nucleophilic attack by the N6 of adenine on the methyl group of TMS. Two calculations were performed on the ground state to determine the effect that MTaqI's orientation of the substrates has on the activation barrier for the reaction as described in Methods. All of the Hartree-Fock stationary points for the noncatalyzed reaction are shown in Fig. 3. Stationary points from the DFT optimizations have similar geometries. The reactant obtained from full optimization in the gas phase will be referred to as the ion molecule complex (IMC) geometry. The structure resembling the attack geometry in the enzyme's active site will be referred to as the ground state in the enzyme (GSE) geometry. In the IMC structure, the trimethylsulfonium ion straddles the N1 of the adenine ring to stabilize the positive charge on the sulfur through electrostatic interactions. The closest methyl on the TMS is 3.78 Å away from the attacking nitrogen. The angle between the N6 of adenine, the activated methyl, and the sulfur is not optimal for SN2 attack. A significant conformational change is required for the TMS molecule to be in position for an SN2 attack to occur on the methyl. The central barrier separating the reactants and products for this reaction is calculated to be 28.0, 32.0, and 24.0 kcal/mol for the HF, MP2, and DFT calculations, respectively (Fig. 4A). The reaction is endothermic from IMC to transition state (TS) to product and allows for the methylation reaction to readily reverse. In the GSE structure, the closest methyl is 3.30 Å away from the attacking nitrogen and the angle between the N6, the activated methyl, and the sulfur atom is nearly linear. In addition, the enzyme positions the substrates so that the activated methyl is under the adenine and in proximity to the attacking orbital of the nitrogen. This arrangement facilitates the SN2 transfer of the methyl group and does not require that the substrates significantly rearrange to get in position for the nitrogen to attack the methyl. The activation barrier for this reaction is 26.8, 23.4, and 17.3 kcal/mol for the HF, MP2, and DFT calculations, respectively (Fig. 4B). Although the reaction with the GSE is not endothermic as in the case of the IMC noncatalyzed reaction, it is still reversible. Energies from all of the calculations of the noncatalyzed reaction are shown in Table 1. The transition state, denoted TS, for the noncatalyzed reaction is shown in Fig. 3. The activated methyl group is planar and “floats” between the sulfur and attacking nitrogen in the transition state. The sulfur carbon distance increases from 1.81 Å in the GSE to 2.46 Å in the transition state, whereas the carbon nitrogen distance contracts from 3.30 Å in the GSE to 2.10 Å in the TS. The full-positive charge that was confined to the sulfur in the ground state is shared across the sulfur, attacking nitrogen, and the methyl group in the transition state.

Figure 3.

Stationary points obtained for the noncatalyzed reaction at the HF/6–31+G(d,p) level of theory. The distances between the atoms are in angstroms and the angles are in degrees. All angles reported are formed by H–N6–H.

Figure 4.

Relative energies for the noncatalyzed methyl transfer reaction at the HF/6–31+G(d,p) (●), MP2/6–31+G(d,p)//HF/6–31+G(d,p) (○), and B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) (■) levels of theory. A shows the relative energies for the IMC methyl transfer and B shows the relative energies for the GSE methyl transfer. Energies in B do not include zero point energies (ZPE).

Table 1.

Energies for the noncatalyzed methyl transfer from TMS to adenine

| Electronic energies, Hartrees | ZPE, kcal/mol | |

|---|---|---|

| HF/6-31+G(d,p) | ||

| Adenine | −464.549887201 | 67.68209 |

| TMS | −516.126872813 | 68.91310 |

| IMC | −980.693278577 | 142.26257 |

| GSE | −980.683897592 | — |

| TS | −980.641160209 | 137.53045 |

| Product | −980.685216503 | 139.03595 |

| DMS | −476.746082175 | 45.26776 |

| N-methyladenine | −503.930646353 | 93.48344 |

| MP2/6-31+G(d,p) | ||

| Adenine | −466.06474839276 | |

| TMS | −516.72584585453 | |

| IMC | −982.81667582093 | |

| GSE | −982.80298458087 | |

| TS | −982.76571995622 | |

| Product | −982.80268875149 | |

| DMS | −477.17334030449 | |

| N-methyladenine | −505.59643280287 | |

| B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) | ||

| Adenine | −467.353149121 | 68.61843 |

| TMS | −517.683556500 | 71.00511 |

| IMC | −985.055544755 | 141.18127 |

| GSE | −985.044328978 | — |

| TS | −985.016699124 | 140.77378 |

| Product | −985.043634621 | 142.14832 |

| DMS | −478.025919628 | 46.56299 |

| N-methyladenine | −507.009278295 | 95.24123 |

| B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) + COSMO | ||

| Adenine | −467.379325887 | |

| TMS | −517.759170204 | |

| IMC | −985.138482266 | |

| TS | −985.106571019 | |

| Product | −985.142463535 | |

| DMS | −478.029607808 | |

| N-methyladenine | −507.112813418 |

Analysis of all of the stationary points shows a continual change in the hybridization of the attacking nitrogen from sp2 in the separated products to sp3 in the tetrahedral product. This change in hybridization can be observed by monitoring the geometry changes around the attacking nitrogen throughout the progress of the reaction. Isolated adenine optimized in the gas phase is completely planar. The H–N6–H angle is 120° and the C6–N6 bond length is 1.34 Å (Fig. 3). In the tetrahedral product where the nitrogen is sp3 hybridized, the H–N6–H angle is 108° and the C6–N6 bold length is 1.46 Å. Both the IMC and GSE complexes have H–N6–H bond angles close to 113.5°. These distortions from the planar adenine are accompanied by a slight lengthening of the N6–C6 bond in each of the reactant complexes. Both of these changes indicate a small shift away from sp2 toward sp3 hybridization. The transition-state structure has the N6–C6 bond increased to 1.41 Å, indicating that a significant shift toward sp3 hybridization is starting to occur as the nitrogen begins to form a bond with the methyl group.

The Catalyzed Reaction.

Mutational studies that have shown the phenolic hydroxyl group of Tyr-108 to not participate in the catalytic mechanism of MTaqI eliminate the option of the ionized Tyr-108 acting as a general base in the active site of the enzyme to abstract a proton from the aminonucleophile (28). It has been suggested that the positioning of the tyrosine residue would allow for the π-electrons of the aromatic tyrosine to interact with the developing positive charge on the nitrogen and thus serve to stabilize the transition state (37). The mutational study discounts this form of stabilization as a major contribution to lowering the activation barrier as the Y108A mutation causes only a ≈50-fold decrease in kcat. With no other obvious general base present, the enzyme's means for catalyzing the reaction was not obvious and has been the subject of speculation. It was known that the backbone amide oxygen of Pro-106 accepts a hydrogen bond from one of the amine hydrogens of the N6 while the side chain of Asn-105 hydrogen bonds with the other hydrogen (Fig. 5). It was thought that this bonding arrangement served to increase the electron density on the attacking nitrogen. However, previous to the most current crystal structure, it was impossible to see that the hydrogen bond acceptors lie below the plane of the adenine on the opposite side from AdoMet. It has been proposed that forming these hydrogen bonds with the amine group in this position forces a change in hybridization from sp2 to sp3 and in the process localizes the electrons onto the nitrogen (23). To explore the possible rate enhancing effect of the hydrogen bonding in the active site, a model system was constructed according to the coordinates of the x-ray crystal structure. Stationary points for the catalyzed reaction were obtained at the HF level of theory (Fig. 6). The DFT optimizations produced similar geometries. The addition of formamide into the reaction induces very little change in the GSE, TS, and product when compared with the same structures in the noncatalyzed reaction. The GSE with formamide has a C6–N6 bond length of 1.35 Å and a N–H6–N angle of 117.2°. This finding indicates that in the GSE for the catalyzed reaction the attacking nitrogen has more sp2 character in the ground state than either of the ground states in the noncatalyzed reaction. The enzyme's organization of the two reactants puts them in close enough proximity to induce a shift away from sp2 hybridization that is not in any way furthered by hydrogen bonding with Asn-105. Therefore, the hydrogen bonding between the adenine and Asn-105 does not serve to coax the hybridization of the nitrogen in the ground state toward sp3 geometry and does not provide a significant rate enhancing effect. This is reflected in the activation barrier for the catalyzed reaction being lowered by 2.2, 1.6, and 1.5 kcal/mol from the HF, MP2, and DFT calculations, respectively, relative to the noncatalyzed reaction. The activation barrier for the formamide catalyzed reaction, as shown in Fig. 7, is calculated to be 24.6, 21.8, and 15.8 kcal/mol from the HF, MP2, and DFT calculations, respectively. Energies from all of the calculations for the catalyzed reaction are shown in Table 2. In the transition state for the catalyzed reaction, the attacking nitrogen also has more sp2 character relative to the noncatalyzed reaction. Thus, the catalyzed reaction has a slightly earlier transition state relative to the noncatalyzed reaction. Comparison of the reaction coordinates for the catalyzed and the noncatalyzed reaction reveals that a more significant rate-enhancing effect comes from the enzyme's organization of the substrates in the active site when compared with the effect that the hydrogen bonding with the active site side chain has on the activation barrier. The addition of the formamide into the system proves to have a minor effect on the barrier in comparison to the orientation effects. However, although the formamide does not serve to greatly enhance the rate of the reaction, the bond formed between the O14 and amine hydrogen of N6 contracts 0.3 Å in the product serving to stabilize the positive charge on the N6 and causing the methylation reaction to be exothermic and nonreversible.

Figure 5.

Stereo picture of interactions between adenine and active site residues in MTaqI. Only side chains are shown for Phe-196, Tyr-108, and Asn-105. The backbone oxygen of Pro-106 is forming a hydrogen bond with adenine.

Figure 6.

Stationary points obtained for the catalyzed reaction at the HF/6–31+G(d,p) level of theory. The distances between the atoms are in angstroms and angles are in degrees. All angles reported are formed by H–N6–H.

Figure 7.

Relative energies for the catalyzed methyl transfer reaction at the HF/6–31+G(d,p) (●), MP2/6–31+G(d,p)//HF/6–31+G(d,p) (○), and B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) (■) levels of theory. Energies do not include ZPE.

Table 2.

Energies for the catalyzed methyl transfer from TMS to adenine

| Electronic energies, Hartrees | ZPE, kcal/mol | |

|---|---|---|

| HF/6-31+G(d,p) | ||

| Adenine | −464.549887201 | 67.68209 |

| TMS | −516.126872813 | 68.91310 |

| Formamide | −168.948420394 | 27.50956 |

| IMC | −1149.65535606 | — |

| TS | −1149.61608471 | 166.39590 |

| Product | −1149.66705258 | 167.70445 |

| DMS | −476.746082175 | 45.26776 |

| N-methyladenine | −503.930646353 | 93.48344 |

| MP2/6-31+G(d,p) | ||

| Adenine | −466.06474839276 | |

| TMS | −516.72584585453 | |

| Formamide | −169.44644057807 | |

| IMC | −1152.2798863060 | |

| TS | −1152.2451204441 | |

| Product | −1152.2886308198 | |

| DMS | −477.17334030449 | |

| N-methyladenine | −505.59643280287 | |

| B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) | ||

| Adenine | −467.353149121 | 68.61843 |

| TMS | −517.683556500 | 71.00511 |

| Formamide | −169.910820236 | 27.95666 |

| IMC | −1154.98113660 | — |

| TS | −1154.95594616 | 170.23970 |

| Product | −1154.99068561 | 171.22515 |

| DMS | −478.025919628 | 46.56299 |

| N-methyladenine | −507.009278295 | 95.24123 |

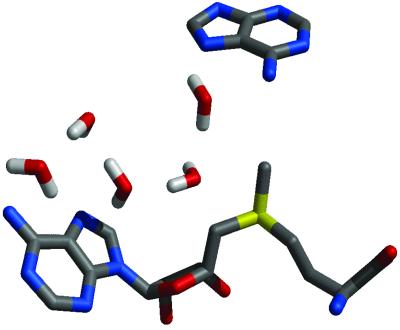

Hydrogen bonding with formamide does not cause significant stretching of the N–H bond on the attacking amino group in the transition state. Thus, abstraction of the hydrogen is not simultaneous with the methyl transfer but rather stepwise with the transfer of the methyl group occurring first, followed by the abstraction of the proton from the intermediate tetrahedral product in the subsequent step. The proton acceptor could be the Asn-105 or the backbone oxygen of Pro-106 because the tetrahedral nitrogen is significantly more acidic. However, we suggest that it is most likely an active site water molecule near the adenine that abstracts the hydrogen because it is part of a water channel that leads out to bulk solvent (Fig. 8). It has been suggested that water molecules play a similar role in the active site of the HhaI DNA Mtase (29). It should be noted that the N–H bond starts to stretch in the fully sp3-hybridized product and that if there are other factors—i.e., π interactions that could shift the transition state to later in the reaction coordinate—then the proton abstraction might be able to occur simultaneously.

Figure 8.

Active-site water chain leading from bulk solvent to proton on N6 of adenine in MTaqI.

Conclusions

Our results show that the methyl transfer reaction catalyzed by MTaqI does not rely on hydrogen bonding in the active site to achieve significant rate enhancement. Optimal positioning of AdoMet in the active site of MTaqI for the SN2 transfer of the methyl group to the N6 of adenine produces a far greater rate enhancement than the hydrogen bonding. Furthermore, when compared with the noncatalyzed reaction, the hydrogen bonding in the active site between the adenine and the terminal oxygen of Asn-105 does not change the hybridization of the attacking nitrogen toward sp3 to prepare it for nucleophilic attack. When hydrogen bonding with the formamide, the transition state occurs slightly earlier on the reaction coordinate. Thus, the mechanism is stepwise with the methyl group first adding to the nucleophilic nitrogen forming a fully sp3-hybridized product. The adenine then becomes significantly more acidic and can lose the proton to bases much too weak to abstract the proton concertedly with the transfer of the methyl. An active-site water molecule most likely fills this role, transferring the proton to bulk solvent by means of a water bridge.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for their helpful suggestions and Dr. Kalju Kahn for his advice throughout the project. This study was supported by the National Science Foundation. The authors gratefully acknowledge computer time on the University of California, Santa Barbara, Origin2000, which is partially supported by Grant CDA96-01954 from the National Science Foundation and a grant from Silicon Graphics Inc.

Abbreviations

- MTaqI

DNA methyltransferase from Thermus aquaticus

- AdoMet

S-adenosyl-l-methionine

- Mtases

methyltransferases

- IMC

ion molecule complex

- GSE

ground state in the enzyme

- TMS

trimethylsulfonium

- DFT

density functional theory

- HF

Hartree–Fock

- TS

transition state

Footnotes

Holz, B., Pues, H., Wolcke, J. & Weinhold, E. (1997) FASEB J. 11, A1151 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Marinus M G, Poteete A, Arraj J A. Gene. 1984;28:123–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modrich P. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:229–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boye E, Lobner-Olesen A. Cell. 1990;62:981–989. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90272-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell D W, Zinder N D. Cell. 1987;50:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden G B, Pratt M J, Schaechter M. Cell. 1988;54:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell J L, Kleckner N. Cell. 1990;62:967–979. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90271-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braaten B A, Nou X, Kaltenbach L S, Low D A. Cell. 1994;76:577–588. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nou X, Skinner B, Braaten B, Blyn L, Hirsh D, Low D. Mol Microbol. 1993;7:545–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bird A P, Wolffe A P. Cell. 1999;99:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyes J, Bird A P. EMBO J. 1992;11:327–333. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandeis M, Ariel M, Cedar H. BioEssays. 1993;15:709–713. doi: 10.1002/bies.950151103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaenisch R. Trends Genet. 1997;13:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bickle T A, Kruger D H. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:434–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.434-450.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephens C, Reisenauer A, Wright R, Shapiro L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1210–1214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright R, Stephens C, Shapiro L. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5869–5877. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5869-5877.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson G, Reisenauer A, Wright R, Jensen R, Jensen A, Shapiro L, Roop R M. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3482–3489. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.12.3482-3489.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahng L S, Shapiro L. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3065–3075. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3065-3075.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Low D A, Weyand N J, Mahan M J. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7197–7204. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7197-7204.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Gara M, Zhang X, Roberts R J, Cheng X. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:201–209. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong W, O'Gara M, Blumenthal R M, Cheng X. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2702–2715. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.14.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schluckebier G, Kozak M, Bleimling N, Weinhold E, Saenger W. J Mol Biol. 1997;265:56–67. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schluckebier G, O'Gara M, Saenger W, Cheng X. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:16–20. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goedecke K, Pignot M, Goody R S, Scheidig A J, Weinhold E. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:121–125. doi: 10.1038/84104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malone T, Blumenthal R M, Cheng X. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:618–632. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labahn J, Granzin J, Schluckebier G, Robinson D P, Jack W E, Schildkraut I, Saenger W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10957–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holz B, Klimasauskas S, Serva S, Weinhold E. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1076–1083. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holz B, Weinhold E. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1999;18:1355–1358. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pues H, Bleimling N, Holz B, Wolcke J, Weinhold E. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1426–1434. doi: 10.1021/bi9818016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau E Y, Bruice T C. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:9–18. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frisch M J, Trucks G W, Schlegel H B, Pople J A. GAUSSIAN 98. Pittsburgh: Gaussian; 1998. , Version A.6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becke A D. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee C, Yang W, Parr R G. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pople J A, Scott A P, Wong M W, Radom L. Isr J Chem. 1993;33:345–350. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong M W. Chem Phys Lett. 1996;256:391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bach R D, Glukhovtsev M N, Gonzalez C, Marquez M, Estevez C M, Baboul A G, Schlegel H B. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:6092–6100. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart J J P. J Comput Chem. 1989;10:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schluckebeir G, Labahn J, Granzin J, Saenger W. Biol Chem. 1998;379:389–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]