Abstract

Replication of HIV requires the Tat protein, which activates elongation of RNA polymerase II transcription at the HIV-1 promoter by interacting with the cyclin T1 (CycT1) subunit of the positive transcription elongation factor complex b (P-TEFb). The transactivation domain of Tat binds directly to the CycT1 subunit of P-TEFb and induces loop sequence-specific binding of P-TEFb onto nascent HIV-1 trans-activation responsive region (TAR) RNA. We used systematic RNA–protein photocross-linking, Western blot analysis, and protein footprinting to show that residues 252–260 of CycT1 interact with one side of the TAR RNA loop and enhance interaction of Tat residue K50 to the other side of the loop. Our results show that TAR RNA provides a scaffold for two protein partners to bind and assemble a regulatory switch in HIV replication. RNA-mediated assembly of RNA–protein complexes could be a general mechanism for stable ribonucleoprotein complex formation and a key step in regulating other cellular processes and viral replication.

HIV-1 encodes a transcriptional activator protein, Tat, which is expressed early in the viral life cycle and is essential for viral gene expression, replication, and pathogenesis (1–3). Tat enhances processivity of RNA polymerase II (pol II) elongation complexes that initiate in the HIV long terminal repeat region. In nuclear extracts, HIV-1 Tat associates tightly with the CDK9-containing positive transcription elongation factor complex b, P-TEFb (4–6). Recent studies indicate that Tat binds directly through its transactivation domain to the cyclin T1 (CycT1) subunit of the P-TEFb complex and induces loop sequence-specific binding of the P-TEFb complex to trans-activation responsive region (TAR) RNA (7–9).

Recruitment of P-TEFb to TAR has been proposed to be both necessary and sufficient for activating transcription elongation from the HIV-1 long terminal repeat promoter (10). Neither CycT1 nor the P-TEFb complex bind TAR RNA in the absence of Tat; thus TAR binding is highly cooperative for both Tat and P-TEFb (7, 9). In the C-terminal boundary of the CycT1 cyclin domain, Tat appears to contact residues that are not critical for CycT1 binding to CDK9 (8, 11–15). Mutagenesis studies showed that the CycT1 sequence containing amino acids 1–303 was sufficient to form complexes with Tat-TAR and CDK9 (8, 11–15). Recent fluorescence resonance energy-transfer studies using fluorescein-labeled TAR RNA and a rhodamine-labeled Tat protein showed that CycT1 remodels the structure of Tat to enhance its affinity for TAR RNA, and that TAR RNA further enhances interaction between Tat and CycT1 (16).

The mechanism by which CycT1 induces loop sequence-specific binding of the P-TEFb complex onto nascent HIV-1 TAR RNA is not understood presently. Does CycT1 interact directly with the TAR loop or merely reorganize Tat structure to bind the loop residues? Does Tat bind TAR loop in the presence of CycT1? What regions of CycT1 and Tat interact directly with the TAR loop sequence? Does phosphorylation of P-TEFb change the CycT1 region that contacts TAR RNA? We report here the use of systematic site-specific RNA–protein photocross-linking, Western blot analysis, and protein footprinting to define RNA–protein interactions in assembling the P-TEFb–Tat-TAR complex.

Materials and Methods

RNA and Protein Preparation.

RNAs containing 4-thiouridine at specific sites were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). RNAs were 5′ end-labeled with 0.5 μM [γ-32P]ATP [6,000 Ci/mmol (1 Ci = 37 GBq), ICN] per 100 pmol of nucleic acid by incubation with 16 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB, Beverly, MA) in the provided buffer. 5′ end-labeled RNAs were purified on a 20% denaturing gel, visualized by autoradiography, eluted from the polyacrylamide gels, and desalted on a reverse-phase cartridge. HA-tagged Tat (amino acids 1–86), CycT1 (amino acids 1–303), (TK)-Tat (amino acids 1–86), and (TK)-CycT1 (amino acids 1–303) were expressed in Escherichia coli (DHα strain) as glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins. These fusion proteins consisted of an N-terminal glutathione S-transferase moiety followed by a thrombin cleavage site. The hemagglutinin (HA) tag was expressed at the C terminus of Tat. The thymidine kinase (TK) site was cloned at the N terminus of Tat or CycT1(1–303). (HA)-Tat(1–86) and CycT1(1–303) clones were a kind gift from K. A. Jones (The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA). The (TK)-Tat clone was obtained from the National Institutes of Health. For the (TK)-CycT1(1–303) clone, the CycT1 DNA sequence corresponding to amino acids 1–303 was inserted into plasmid pGEX-2TK (Amersham Pharmacia) between BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. CycT1(1–303) DNA was obtained by PCR of pSF1 [glutathione S-transferase-CycT1(1–726)] plasmid with the following primers: 5′ end, 5′-GCGGATCCATGGAGGGAGAGAGGAA-3′, and 3′ end, 5′-GCGAATTCTGACATGCTCATTAAACCTGCA-3′. The clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Recombinant fusion proteins were purified from bacterial lysates by glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia) for 1 h at 4°C. The beads then were poured into a column and washed with 10 ml of WB buffer (1× PBS/1% Triton X-100/1 mM EDTA/50 μg/ml PMSF). For 32P labeling at the TK site of Tat and CycT1(1–303), the beads were equilibrated with 10 ml of PKA buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/10 mM MgCl2) added with 5 units of cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (Promega) and 200 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 20 min. The beads then were washed extensively with WB and TB (150 mM NaCl/50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0/2.5 mM CaCl2/5 mM DTT) buffers. To recover proteins, glutathione-Sepharose beads were treated with 50 NIH units of thrombin in 1 ml of TB and rocked at RT for 20 min before elution. Eluted proteins were stored as aliquots at −80°C. Expression and purification of P-TEFb proteins were carried out as described by Peng et al. (17).

RNA–Protein Binding Assays and Photocross-Linking Reactions.

A typical binding reaction contained 1 pmol of TAR RNA and 10 pmol of Tat and CycT1(1–303) or P-TEFb in RBB buffer (30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.6/1% glycerol/3 mM DTT/50 mM KCl/5.4 mM MgCl2 and 100 μM ATP where indicated). Reaction mixtures (30 μl) were incubated at 30°C for 30 min before adding 20 μl of loading buffer (60% glycerol/0.01% bromophenol blue). Samples were loaded onto 10% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and run at 350 V for 1.5 h. For photocross-linking reactions, binding mixtures containing RNA and proteins were incubated at 30°C for 30 min and then irradiated (360 nm) for 20 min. After irradiation, 20 μl of 2× SDS loading buffer (100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.8/200 mM DTT/4% SDS/0.2% bromophenol blue/20% glycerol) were added to reaction mixtures, and samples were loaded onto 15% SDS gels and run at 30 mA for 4 h. The efficiencies of RNA–protein binding and cross-linking reactions were determined by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). For Western blot analysis, gel contents were transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes (Bio-Rad). Tat protein was detected by immunoblotting with a biotin-conjugated mouse antibody against the HA tag (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). CycT1(1–303) and CycT1(1–726) were detected with N-terminal (N-19) and C-terminal (T-18) CycT1 goat polyclonal antibodies, respectively (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were visualized with a BM chemiluminescence blotting kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and exposed to x-ray films for various times (10 sec to 1 min).

For preparative scale cross-linking reactions, 1 nmol of TAR RNA, Tat and CycT1(1–303), or P-TEFb were used to form RNA–protein complexes. These binding mixtures were irradiated (360 nm) and separated by 8 or 10% SDS/PAGE. The RNA–protein cross-link bands were visualized by autoradiography and electroeluted in SDS glycine buffer (25 mM Tris⋅HCl/250 mM glycine, pH 8.3/0.1% SDS) at 200 V for 2 h. Samples were dialyzed in 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 1 h and stored at 4°C.

Identification of Cross-Link Sites on TAR RNA, CycT1, and Tat.

Alkaline hydrolysis of free and cross-linked 32P-labeled TAR RNAs was carried out in hydrolysis buffer (50 mM Na2CO3/NaHCO3, pH 9.2) at 85°C for 15–20 min. TAR RNAs, labeled at the 5′ end, were incubated with 1 unit of T1 ribonuclease (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) at 4°C for 2 min in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0.

Purified 32P-labeled Tat and CycT1(1–303) and their cross-linked products (2 μl in 10-μl final reaction volume) were digested with sequencing grade proteases under the following conditions: 50 ng of modified trypsin (Promega) in 50 mM NH4HCO3 at 4°C for 1 min; 0.1 μg of LysC in 25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA at RT for 10 min; 0.1 μg of GluC in 50 mM NH4HCO3, pH 7.8 at RT for 5 min; and 0.1 μg of ArgC in 100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.6/10 mM CaCl2/5 mM DTT/0.5 mM EDTA at RT for 5 min. LysC, GluC, and ArgC were obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. For Cys cleavage, free and cross-linked proteins (2 μl) were incubated with 20 μl of cleavage buffer (1 M urea/5 mM β-mercaptoethanol/210 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.8) at 37°C for 15 min. After adding 2 μl of 2-nitro-5-thiocyano-benzoic acid (NTCB, 10 mg/ml in CH3OH), reaction mixtures were kept at 37°C for 15 min followed by the addition of 1 μl of 1 M NaOH and another 20 min at 37°C. All reactions were quenched by adding 10 μl of SDS loading buffer and freezing on dry ice. Samples then were heated at 100°C for 2 min and immediately loaded onto 15% SDS gels. Gels were run at 30 mA for 4.15 h.

Results

CycT1 Interacts with Nucleotide 31 in TAR Loop and Enhances Interaction Between Tat and Nucleotide 34.

To determine the direct interactions of CycT1 and Tat with TAR RNA loop residues, we chemically synthesized three TAR RNA constructs with a photoactive nucleoside, 4-thiouridine, at position 31, 33, or 34 (Fig. 1). Our experimental design to incorporate 4-thiouridine was based on observations that mutations at position 31 and 33 in TAR RNA loop did not significantly decrease CycT1–Tat binding. A single mutation at G34 to U34, however, dramatically decreased the binding of CycT1–Tat to TAR, and this binding was restored in part by a compensatory mutation at position C30 with A30 (18). We therefore synthesized a functional TAR RNA containing A30 and 4-thiouridine at position 34 for cross-linking experiments (Fig. 1). RNA sequences containing 4-thiouridine at position 31, 33, or 34 are referred to as sU31, sU33, or A30-sU34 TAR RNA, respectively.

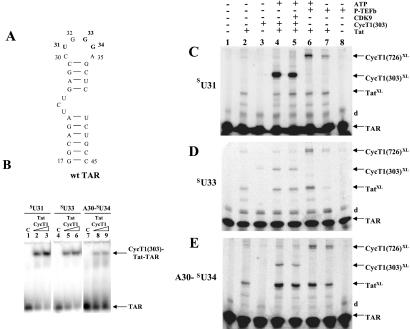

Figure 1.

Site-specific photocross-linking in CycT1–Tat-TAR complexes containing 4-thiouridine. (A) Secondary structure of TAR RNA used in this study. TAR RNA spans the minimal sequences required for Tat responsiveness in vivo (32) and for in vitro binding of Tat-derived peptides (33). Wild-type (wt) TAR contains two non-wild-type base pairs to increase transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. Sites of 4-thiouridine incorporation, U31, G33, and G34, are bolded in the TAR RNA. Numbering of nucleotides in the RNA corresponds to their positions in wild-type TAR RNA. (B) RNA gel-shift analysis of complexes containing recombinant Tat, CycT1(1–303), and sU31, sU33, and A30–sU34 TAR RNA sequences. Control (C) lanes are without proteins. Lanes 2 and 3, 5 and 6, and 8 and 9 contain increasing concentrations of protein complexes (0.2 μg of Tat and 0.6–1.2 μg of CycT1). Arrows indicate the position of RNA and RNA–protein complexes. (C–E) Analysis of RNA–protein photocross-link products. TAR RNA containing sU at specific positions in the loop was 5′ end-labeled and used to form complexes with Tat and CycT1 or P-TEFb, UV-irradiated (360 nm), and resolved on 15% SDS polyacrylamide gels. The sU RNA used is indicated on the left, and identities of cross-linked products are on the right. The letter “d” refers to dimers of TAR RNA. Lane 1 (control) contains RNA without irradiation. RNA–protein cross-link products with Tat, CycT1(1–303), and full-length CycT1 from P-TEFb are indicated as TatXL, CycT1 (303)XL, and CycT1 (726)XL, respectively.

To characterize and evaluate CycT1–Tat binding capabilities of 4-thiouridine-containing TAR RNAs, we performed electrophoretic mobility-shift experiments (Fig. 1B). Under similar conditions, CycT1–Tat bound all three sU TAR RNA sequences with varying efficiencies of RNA–protein complex formation: 75% with sU31 TAR, 60% with sU33 TAR, and 30% with A30- sU34 TAR. We used CycT1(1–303) in these RNA gel-shift assays instead of P-TEFb for three reasons: (i) this region of CycT1 is sufficient to form stable complexes with Tat-TAR and CDK9 (8, 10–14, 19–21), (ii) the kinase subunit CDK9 does not interfere with CycT1 specificity for Tat-TAR binding (8, 10–14, 19–21), and (iii) detection of the CycT1(1–303)–Tat-TAR complex by native gel electrophoresis methods is more straightforward and reliable compared with P-TEFb–Tat-TAR or CycT1(1–726)–Tat-TAR complexes. These results indicate that all 4-thiouridine-containing RNA sequences can form complexes with CycT1–Tat.

Site-specific photocross-linking reactions on ternary complexes containing CycT1, Tat, and sU TAR RNAs were performed by UV-irradiating (360 nm) the complexes. Cross-link products were analyzed by denaturing 15% SDS/PAGE (Fig. 1 C–E). Irradiation of 4-thiouridine-containing TAR RNAs with proteins yields bands with electrophoretic mobility less than that of TAR RNAs. As shown in Fig. 1C (lane 4), TAR RNA containing 4-thiouridine at position 31 formed a high-efficiency cross-link with CycT1(1–303) in the presence of Tat, whereas the Tat-TAR cross-link was a minor product. RNA–protein cross-link product formation with sU33 TAR was not very efficient, however, and both CycT1 and Tat resulted in minor cross-links bands (Fig. 1D, lane 4). It is interesting to note that the Tat-TAR cross-link was a major product when A30- sU34 TAR was photocross-linked with Tat, but this strong yield occurred only in the presence of CycT1 (Fig. 1E, lanes 2 and 4). The amount of Tat-TAR cross-link did not increase when sU31 or sU33 TAR were used, and adding CycT1 did not alter the Tat-TAR cross-link yields (Fig. 1 C and D, lanes 2 and 4). CycT1 cross-linking with sU33 or A30-sU34 TAR was not very efficient (Fig. 1 D and E, lane 4). Cross-linking Tat with all three sU TARs without CycT1 resulted in low-yield cross-link products (lane 2). CycT1 in the absence of Tat did not cross-link with any of the three sU TAR RNAs (Fig. 1 C–E, lane 3). Irradiation of sU TAR RNAs resulted in a minor cross-link product containing dimer TAR (“d” in Fig. 1 C–E). These results demonstrate that CycT1(1–303) directly interacts with TAR loop residues (U31, U33, and A30-U34), and the U31 side of the loop is the major site of interaction. Our results also show that in the presence of CycT1(1–303), Tat interacts with the U34 side of the TAR loop.

CDK9 autophosphorylation has been shown to regulate high-affinity binding of the Tat–P-TEFb complex to TAR RNA, suggesting that this autophosphorylation induces a conformational change in CycT1 for TAR binding (22, 23). To determine the phosphorylation effects of CDK9 on CycT1, we carried out our experiments in the presence and absence of ATP (Fig. 1 C–E, lanes 5–7). CDK9 phosphorylation did not show any significant effects on CycT1(1–303) cross-linking with TAR RNA (lane 5), but phosphorylation of P-TEFb enhanced the CycT1(1–726)–TAR cross-link formation (lanes 6 and 7). Control experiments showed that in the absence of Tat, P-TEFb did not cross-link to TAR RNA (Fig. 1 C–E, lane 8). As with CycT1(1–303), full-length CycT1 also formed the highest yield cross-links with sU31 TAR RNA (lane 6). These results demonstrate that P-TEFb phosphorylation enhances interaction of full-length CycT1 with TAR and does not affect CycT1(1–303)–TAR binding. Both full-length CycT1 and CycT1(1–303) interact with the U31 side of the RNA loop.

Identities of the proteins cross-linked to sU TAR RNAs were confirmed by Western blotting with antibodies to detect HA-Tat, CycT1(1–303), and CycT1(1–726). Tat cross-linked to A30-sU34 TAR with high efficiencies (Fig. 2A). CycT1(1–303) and full-length CycT1 gave the highest yield cross-links with sU31 TAR (Fig. 2B and C). Full-length CycT1 antibodies were used to identify the cross-linked products with sU TAR RNAs in the presence of P-TEFb and Tat. These results are consistent with the findings shown in Fig. 1 that sU31 TAR forms CycT1–RNA cross-links with higher efficiencies when compared with sU33 and A30-sU34 TAR sequences.

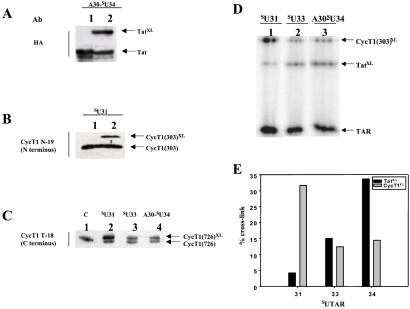

Figure 2.

(A–C) Detection of RNA–protein photocross-link products by Western blotting. RNA–protein cross-link products were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes, and the protein contents were visualized by immunoblotting with antibodies against HA (for HA-Tat) N and C termini of CycT1. Antibodies are shown on the left and sU TAR constructs are above each blot. (A) Analysis of Tat-TAR cross-link. Lane 1 (control) contains Tat without RNA or CycT1. Lane 2 shows products of photocross-linking Tat–CycT1(303) with A30-SU34 TAR. The HA-tagged Tat protein was detected by a biotin-conjugated antibody against the HA tag. (B) Analysis of CycT1(1–303) cross-linked with sU31 TAR RNA. Lane 1 contains CycT1(1–303). Lane 2 contains the products of photocross-linking CycT1(303)–Tat with SU31 TAR RNA. The cross-linked product was detected by CycT1 N-19 antibody against the N-terminal region of CycT1. (C) Cross-linked products of photoreactions containing P-TEFb-Tat-sU TAR sequences. The CycT1(1–726) subunit of P-TEFb cross-linked to sU31, sU33, and A30-sU34 TAR RNA was detected by CycT1 T-18 antibody against the C-terminal region of CycT1. Lane 1 (control) shows the P-TEF-b complex without RNA. (D) Site-specific photocross-linking of CycT1–Tat-TAR complexes in nondenaturing gels. RNA–protein complexes containing Tat, CycT1(1–303), and 5′ end-labeled sU31, sU33, and A30-sU34 TAR RNA sequences were isolated on nondenaturing gels as described in the Fig. 1 legend and irradiated (360 nm) while trapped in the gel. Cross-link products then were analyzed by 15% SDS/PAGE. The sU RNA used is indicated above each lane. RNA–protein cross-link products with Tat and CycT1(1–303) are indicated as TatXL and CycT1XL, respectively. (E) Quantitative analysis of RNA–protein cross-linking reactions. The A30-sU34 TAR RNA is labeled as 34.

To prove that the RNA–protein cross-linking reactions were specific and occurred within the complexes, we end-labeled sU TAR RNAs and incubated them with Tat and CycT1(1–303). RNA–protein complexes were isolated on nondenaturing gels. We next UV irradiated “in gel” trapped complexes and separated the cross-linked products on SDS gels (Fig. 2D). The relative ratios of Tat and CycT1 cross-links were the same as detected by “in solution” cross-linking reactions. Quantitative analysis of the cross-linked products revealed that CycT1 and Tat cross-linked to both sides of the TAR loop, because the sites of major cross-links for CycT1 and Tat were U31 and U34, respectively (Fig. 2E).

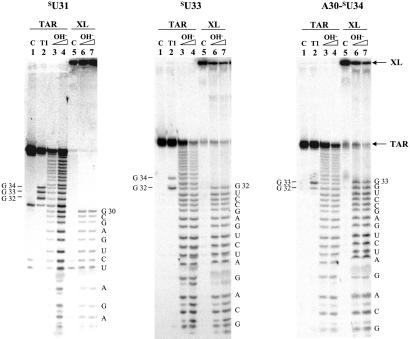

The position of the cross-link on the sU TAR RNA of each CycT1(1–303)–TAR cross-linked product was assessed by alkaline hydrolysis of the 32P-labeled sU nucleic acid. The identity of RNA fragments was confirmed by T1 nuclease digestion at single-stranded guanines in the loop of TAR. In each case the RNA hydrolysis ladder stopped at the nucleotide before the thio-modified base, therefore proving the site of cross-linking to the protein (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mapping of cross-linked bases in the RNA–protein cross-linked products. Lane 1, 5′ end-labeled RNA; lane 2, T1 nuclease digestion of RNA; lanes 3 and 4, hydrolysis ladder of TAR RNA at 85°C for 10 and 15 min, respectively; lane 5, RNA–protein cross-link; lanes 6 and 7, hydrolysis ladder of the RNA–protein cross-link at 85°C for 10 and 15 min, respectively. The TAR RNA sequence is labeled on the right, and T1 cutting sites are on the left. The sU RNA used in each experiment is indicated above.

CycT1 Amino Acids 252–260 Cross-Link to Nucleotide 31 Side of the TAR Loop.

Formation of covalent bonds between 4-thiouridine TAR RNAs and proteins provides evidence of the binding of CycT1 and Tat to the 31 and 34 sides of the loop, respectively. How do the proteins interact within CycT1–Tat-TAR complex, and which amino acid residues come in close contact with the loop of TAR? To address these questions we developed a protein-footprinting assay for both CycT1 and Tat cross-linked to TAR RNA.

To examine the region of CycT1 cross-linked to the U31 side of TAR loop, we subjected the purified [32P]CycT1(1–303)-sU31 TAR cross-linked product to protease digestion and compared it with the protease cleavage products from noncross-linked (free) [32P]CycT1(1–303). [32P]CycT1 was labeled at the N terminus, hence only N terminus-containing fragments could be detected in this assay. CycT1 cross-linked with TAR RNA had a lower migration rate than free CycT1, and thus each protease-generated fragment that was cross-linked to RNA was detected as a shifted band compared with the analogue fragment obtained from digesting free [32P]CycT1. Fragments generated by cross-linked product digestion, which were not shifted, indicated regions at the N terminus side of the cross-linking site (Fig. 4 A and B).

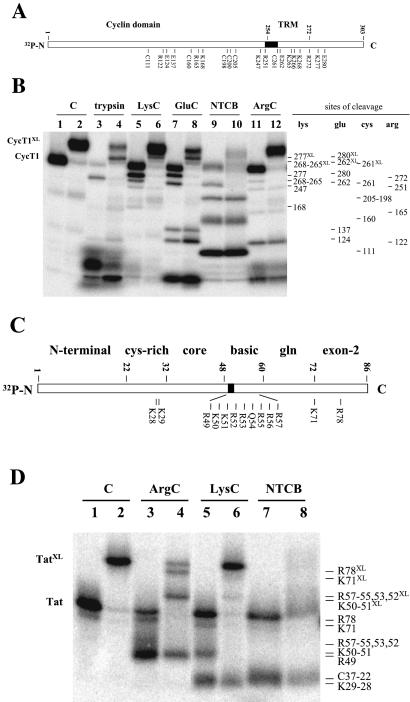

Figure 4.

Mapping of CycT1 and Tat regions photocross-linked to TAR RNA. (A) Schematic representation of protease and NTCB cutting sites in CycT1(1–303). TRM, Tat:TAR recognition motif. (B) CycT1(1–303) labeled at the N terminus with 32P as described was photocross-linked with unlabeled sU31 TAR RNA and Tat. To locate the cross-linked region, cross-linked (even-numbered lanes) and noncross-linked (odd-numbered lanes) CycT1 subunits were subjected to protease and NTCB digestions as indicated, and the cleavage patterns from these reactions were compared. Lanes 1 and 2 (control) contain purified nontreated CycT1. Samples (lanes 3–12) were treated with the proteases or chemicals indicated above. Identified cutting sites are labeled on the right: Lys for LysC, Arg for ArgC, Glu for GluC, and Cys for NTCB. Trypsin cleavage was identified mainly at Lys. Fragments bound to cross-linked TAR migrated slower than noncross-linked fragments and are indicated by the site of cleavage and XL (see text for details). (C) Schematic representation of protease and NTCB cutting sites in Tat. (D) Tat labeled at the N terminus with 32P as described was photocross-linked with unlabeled A30-sU34 TAR RNA and CycT1. To locate the cross-linked region, cross-linked (even-numbered lanes) and noncross-linked (odd-numbered lanes) Tat were subjected to protease and NTCB digestions as indicated, and the cleavage patterns from these reactions were compared. Lanes 1 and 2 (control) contain purified nontreated Tat. Samples (lanes 3–8) were treated with the proteases or chemicals indicated above. Identified cutting sites are labeled on the right: Lys for LysC and Arg for ArgC. Fragments bound to cross-linked TAR migrated slower than the noncross-linked fragments and are indicated by the site of cleavage and XL (see text for details).

Digestion was performed with four different sequencing-grade proteases (Trypsin for Arg and Lys, ArgC for Arg, LysC for Lys, and GluC for Glu). Protein cleavage at Cys residues was performed by NTCB. The identity of the obtained fragments was assigned by comparing the digestion pattern at the indicated cutting sites. The results are shown in Fig. 4 A and B.

Because only six Cys residues are distributed along the CycT1 sequence, NTCB cleavage at Cys allowed a first-coarse mapping of the whole protein and determination of a 62-aa region where the cross-linking site was located. Cleavage occurred at all Cys (amino acids 261, 205, 200, 198, 160, and 111) residues (Fig. 4B, lane 9). Cys-205, Cys-200, and Cys-198 were detected as a single band. Fragment 1–261 can be seen clearly in the free [32P]CycT1 (Fig. 4B, lane 9) but is shifted in cross-linked CycT1 (lane 10). NTCB cleavage of both free and cross-linked CycT1 at 198 gave identical bands on gel. This analysis revealed that the RNA was cross-linked covalently to the CycT1 region between amino acids 198 and 261.

Further protease digestion allowed us to narrow the region where cross-linking occurred on CycT1. ArgC-relevant cutting sites were detected at positions 122, 165, 251, and 272. The cleavage patterns of the cross-linked and free proteins clearly indicated that the RNA was bound to fragment 1–272 but not to 1–251, because the only protein fragment band corresponding to 1–272 was absent from the cross-linked CycT1 digestion (lanes 11 and 12). Combining these results with the data from NTCB cleavage at Cys, we defined the cross-linked region in CycT1 to nine amino acids, 252–260.

LysC, GluC, and trypsin digestion helped us confirm the positions of the identified residues. Four important cutting sites by GluC were observed in free CycT1 at 124, 137, 262, and 280 (lane 7). When cross-linked CycT1 was digested with GluC, 262, and 280 bands were shifted, indicating that the cross-linked site was located before residue 262 from the N terminus of CycT1 (lane 8). During LysC digestion, cleavage occurred in free CycT1 at 168, 247, 265–268 (appears as one band), and 277 (lane 5), and bands corresponding to 265–268 and 277 were shifted in cross-linked CycT1 (lane 6). Trypsin cleavage was very efficient, and one major band, corresponding to Lys-265–268 and observed in free CycT1 (lane 3), clearly was shifted in the cross-linked product (lane 4). These bands were confirmed on gels that were run for longer times to better resolve high molecular weight bands (data not shown). These results demonstrate that sU31 in the TAR loop cross-linked to the 10-aa region of CycT1 containing residues 252–261.

Tat Residue K50 Cross-Links to Nucleotide 34 in TAR Loop.

We next tested which residues of Tat formed covalent bonds with 4-thiouridine at position 34 of TAR by applying the same strategy used to identify the CycT1 cross-linking region. Purified [32P]Tat cross-linked to A30-sU34 TAR and [32P]Tat (free Tat) were subjected to ArgC, LysC, and NTCB cleavage. Arg and Lys residues form the basic domain of Tat, which is flanked by sequences of the core and Gln-rich domains (namely amino acids 38–72; ref. 24). The N terminus (amino acids 1–22) and Cys-rich regions (amino acids 22–32) are part of the Tat core domain (amino acids 1–48), which is known to be essential for Tat to interact with the CycT1 subunit of P-TEFb (1–3). ArgC and LysC proteases cut the middle of the Tat sequence to separate the RNA-binding and CycT1-interacting regions. Therefore, these enzymes were selected to identify the RNA- and CycT1-binding domains separately. We chose NTCB to map cross-linked sites by cleaving protein at Cys residues. This strategy was not very useful, however, because NTCB cleaves at Cys residues under basic conditions, and RNA–Tat protein cross-links were not stable under these conditions. Nonetheless, NTCB cleavage of Tat was useful for locating amino acid positions within the Tat sequence.

ArgC digestion of [32P]Tat gave two bands: one minor band corresponding to cleavage at R78 and another major band with a slight smear region above it containing a heterogeneous population of cleaved fragments caused by enzyme cutting at R57, -56, -55, -53, -52 and -49 (Fig. 4D, lane 3). ArgC digestion of cross-linked [32P]Tat showed the shifted Tat fragment 1–78 (labeled as R78XL), which therefore contains the covalently bound TAR (lane 4). The band containing a heterogeneous population of cleaved fragments was partially shifted (labeled R57–55, 53–52XL) and partially nonshifted (labeled R49) (lane 4; see below LysC digestion).

LysC digestion of [32P]Tat produced three bands: K29–28, K50–51, and K72 (lane 5). LysC digestion of cross-linked [32P]Tat clearly shows that the bands corresponding to K50–51 and K72 were shifted, and the K29–28 band was not (lane 6). Because K51–50 was shifted, the nonshifted band in lane 4 was designated R49, indicating that the cross-linking occurs after residue 49 in the Tat sequence. If the cross-link was formed at K51, the enzyme would cut only at K50 and we would not see the shifted fragment. However, if the cross-linking occurred at K50 and the LysC cut at K51, the protein fragment would be shifted as observed (lanes 4 and 6). These results indicate that cross-linking occurs at K50 in the Tat sequence when 4-thiouridine is incorporated at position 34 in TAR loop.

Adding CycT1 C-Terminal Region and CDK9 Does Not Change the TAR-Interacting CycT1 Conformation.

We have shown that CDK9, whether in complexes containing CycT1(1–303) or CycT1(1–726), did not affect the cross-linking efficiencies of 4-thiouridine-containing TAR to the CycT1 subunit. It has been suggested that the C-terminal region of CycT1 has an autoinhibitory role that is overcome by phosphorylation effects of CDK9 in P-TEFb (22, 23). Does addition of the CycT1 C-terminal domain to CycT1(1–303) and CDK9 change the CycT1 conformation, which would change the regions that cross-link with TAR? To answer this question we prepared 5′ end-labeled SU31 TAR RNA and photocross-linked it with Tat and CycT1 or Tat and P-TEFb in the presence of ATP, as described in the Fig. 1 legend. Expression and purification of P-TEFb proteins was carried out as described by Peng et al. (17).

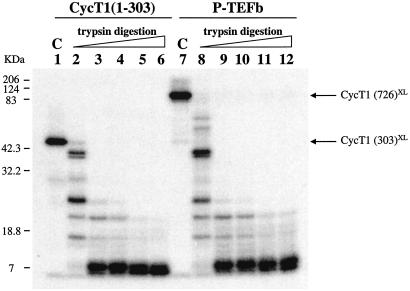

TAR RNA cross-link products with CycT1(1–303) and CycT1(1–726) were purified and subjected to trypsin digestion under the same conditions (Fig. 5). The fragment patterns caused by trypsin cleavage were identical for both cross-linked CycT1 subunits (lanes 2–6 and 8–12). These results show that adding the C-terminal region of CycT1 and CDK9 does not alter the TAR-interacting conformation of CycT1.

Figure 5.

Identical regions of CycT1 in P-TEFb and CycT1(1–303) cross-link to TAR RNA.SU31 TAR RNA was 5′ end-labeled and used to form complexes with Tat and CycT1(1–303) or P-TEFb. These complexes were irradiated, purified, and digested with trypsin. Lanes 1 and 7 (control) contain nontreated CycT1(1–303)–TAR and CycT1(1–726)–TAR cross-links. RNA–protein cross-links were digested with 50 ng of trypsin under identical conditions in lanes 2–6 and 8–12. Lanes 2 and 8, 4°C for 5 min; lanes 3 and 9, 25°C for 5 min; lanes 4 and 10, 30°C for 5 min; lanes 5 and 11, 37°C for 10 min; lanes 6 and 12, 37°C for 1 h.

Discussion

The interaction between P-TEFb, Tat, and TAR is a key step in the transactivation process of HIV-1. The interaction between Tat and TAR is known to involve amino acids 48–57 in the protein moiety and nucleotides in the bulge region of the nucleic acid. The loop of TAR RNA is known to give specificity to P-TEFb–Tat-TAR complex formation, thus allowing differentiation of the immunodeficiency viruses among different host species. The mode of interaction between the protein complex and the loop of TAR, however, had not been elucidated yet.

In this report we have shown that both the CycT1 subunit of the P-TEFb complex and Tat directly interact with different nucleotides within the TAR loop. NMR studies (25, 26) and probing tertiary folding of RNA by a tethered iron chelate (27) revealed that the hairpin loop of TAR RNA has a flexible structure in solution. Our cross-linking results showing specific interaction of proteins to two sides of the TAR loop suggest that the TAR hairpin loop adopts a more defined structure after binding to the Tat–CycT1 complex such that CycT1 and Tat bind to two sides of the loop and interact with specific functional groups. We investigated whether these relevant chemical groups in the TAR loop were involved in protein interactions by incorporating 4-thiouridine nucleotides on different sides of the loop, which after UV irradiation form covalent bonds with vicinal chemical residues.

When the 4-thio group was introduced at position 31, we found that the CycT1 subunit [either in CycT1(1–303)–Tat-TAR or P-TEFb–Tat-TAR complexes] was bound covalently to TAR RNA. When the 4-thio group was moved to position 33 or 34 within the TAR loop, the amount of CycT1 cross-linked to RNA dramatically decreased. Tat alone appeared to bind weakly to all sides of the 4-thio-modified loop. Interestingly, when CycT1 was added to the complex, Tat showed higher covalent binding affinity to the 34 side of the loop and lower affinity to the nucleotide 31 region. In contrast, adding CycT1 did not affect the low cross-linking rate by Tat to position 33. Both CDK9 in the complex or CycT1 in the absence of Tat did not reveal any binding to the TAR loop.

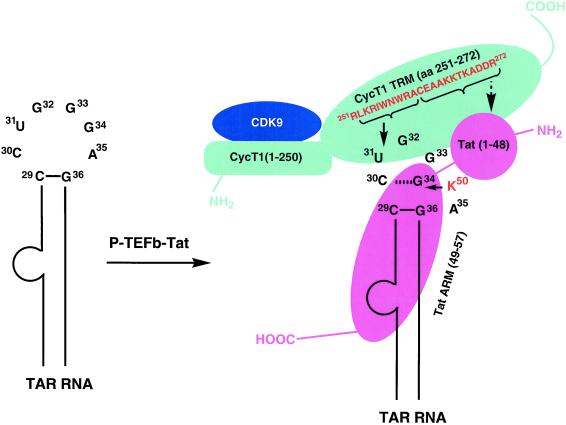

Subsequent protease digestion studies of the Tat-CycT1(1–303)–TAR complex and of the two major cross-linked products (CycT1-SU31 and Tat-A30SU34 TAR) established that residues between amino acids 252 and 261 in the CycT1 subunit are involved in the cross-linking to SU31, and residue Lys-50 in Tat is cross-linked to position 34 of TAR in the presence of CycT1. These findings lead us to suggest a model for P-TEFb–Tat-TAR interaction. When Tat alone is added to TAR RNA, it binds mostly to the bulge region, for which it displays a higher affinity, and makes nonspecific contacts with nucleotides in a possibly fluctuating loop structure. In the presence of CycT1 or the P-TEFb complex, CycT1 binds both to Tat and the nucleotide 31 side of the TAR loop, possibly inducing structural changes in TAR or Tat and TAR where Tat specifically interacts with the 34 side of the nucleic acid (Fig. 6). CycT1 and Tat binding to TAR RNA is highly cooperative, and a capacity of 85.5 ± 0.5%, Hill coefficient of 2.7, and dissociation constant (KD) of 2.45 ± 0.02 nM were observed (18), indicating that there are three binding sites on TAR RNA. CycT1 does not bind TAR RNA in the absence of Tat, and Tat binding to TAR, although detectable, is very inefficient in the absence of CycT1 (18). It is conceivable that the CycT1–Tat heterodimer directly binds to TAR RNA in the U-rich RNA bulge region, and this binding facilitates the interactions of CycT1–Tat at the other two sites in the RNA loop where CycT1 interacts with the U31 side and Tat binds to the G34 side.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of P-TEFb–Tat-TAR ternary complex. P-TEFb is a two-subunit kinase complex containing a CDK9 and a CycT1. CDK9 subunit of P-TEFb binds to the cyclin box sequence (amino acids 1–250) of CycT1. A Tat:TAR recognition motif (TRM) in the CycT1 sequence spans amino acid residues 251–272, which is necessary to form a complex with Tat and TAR RNA. Amino acid sequence 252–260 from TRM was cross-linked to the U31 side of the TAR loop, suggesting that the residues 261–272 are involved in interaction with Tat core domain (amino acids 1–48), shown as a round ball indicating a compact structure. RNA is recognized by the Arg-rich RNA recognition motif (ARM) of Tat, and Lys-50 interacts with the G34 side of the TAR loop. CycT1 and Tat binding to TAR RNA is highly cooperative and a capacity of 85%, Hill coefficient of 2.7, and dissociation constant (KD) of 2.45 nM were observed (18), indicating that there are three binding sites on TAR RNA. It is conceivable that the CycT1–Tat heterodimer directly binds to TAR RNA in the U-rich RNA bulge region, and this binding facilitates the interactions of CycT1–Tat at the other two sites in the RNA loop: CycT1 interacts with the U31 side, and Tat binds to the G34 side. Amino acids cross-linked with TAR RNA are shown by solid arrows and the suggested Tat-interacting region of TRM is shown by a broken arrow. CycT1 is shown in cyan, CDK9 in blue, and Tat in pink. N and C termini of proteins are labeled as NH2 and COOH, respectively.

It is interesting that the TAR RNA provides a scaffold for binding of two protein partners and for the assembly of a regulatory switch in HIV replication. TAR RNA has been shown recently to strongly enhance the interaction between Tat and CycT1 (16). RNA-induced protein–protein interactions have been documented most clearly with the λN protein, which binds to a site in the boxB RNA to mediate transcriptional antitermination (28–31). The regulation of protein interactions through structural alterations in RNA could be an important mechanism for controlling the order of assembling the Tat–P-TEFb–TAR complex, both to ensure that Tat will not commit to TAR in the absence of CycT1(P-TEFb) and that P-TEFb is preferentially used at the viral promoter, because cellular genes do not express TAR RNA. This architectural mechanism for assembling RNA–proteins could be a key step in regulating other cellular processes and viral replication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Katherine Jones for human CycT1 clones and Dr. David Price for P-TEFb clones and assistance in purification. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI 41404.

Abbreviations

- P-TEFb

positive transcription elongation factor complex b

- CycT1

cyclin T1

- TAR

trans-activation responsive region

- HA

hemagglutinin

- TK

thymidine kinase

- RT

room temperature

- sU

sequence containing 4-thiouridine

- NTCB

2-nitro-5-thiocyano-benzoic acid

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Cullen B R. Cell. 1998;93:685–692. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emerman M, Malim M. Science. 1998;280:1880–1884. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taube R, Fujinaga K, Wimmer J, Barboric M, Peterlin B M. Virology. 1999;264:245–253. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Y, Pe'ery T, Peng J, Ramanathan Y, Marshall N, Marshall T, Amendt B, Mathews M B, Price D H. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2622–2632. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancebo H S Y, Lee G, Flygare J, Tomassini J, Luu P, Zhu Y, Peng J, Blau C, Hazuda D, Price D, Flores O. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2633–2644. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold M, Yang X, Herrmann C, Rice A. J Virol. 1998;72:4448–4453. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4448-4453.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei P, Garber M E, Fang S-M, Fischer W H, Jones K A. Cell. 1998;92:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garber M E, Wei P, KewalRamani V N, Mayall T P, Herrmann C H, Rice A P, Littman D R, Jones K A. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3512–3527. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garber M E, Wei P, Jones K A. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:371–380. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieniasz P D, Grdina T A, Bogerd H P, Cullen B R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7791–7796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bieniasz P D, Grdina T A, Bogerd H P, Cullen B R. EMBO J. 1998;17:7056–7065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujinaga K, Cujec T, Peng J, Garriga J, Price D, Grana X, Peterlin B. J Virol. 1998;72:7154–7159. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7154-7159.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wimmer J, Fujinaga K, Taube R, Cujec T, Zhu Y, Peng J, Price D, Peterlin B. Virology. 1999;255:182–189. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivanov D, Kwak Y T, Nee E, Guo J, Garcia-Martinez L F, Gaynor R B. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:41–56. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Q, Chen D, Pierstorff E, Luo K. EMBO J. 1998;17:3681–3691. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Tamilarasu N, Hwang S, Garber M E, Huq I, Jones K A, Rana T M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34314–34319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng J, Zhu Y, Milton J T, Price D H. Genes Dev. 1998;12:755–762. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richter, S., Cao, H. & Rana, T. M. (2002) Biochemistry41, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bieniasz P D, Grdina T A, Bogerd H P, Cullen B R. J Virol. 1999;73:5777–5786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5777-5786.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujinaga K, Taube R, Wimmer J, Cujec T, Peterlin B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1285–1290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen D, Fong Y, Zhou Q. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2728–2733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fong Y W, Zhou Q. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5897–5907. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.5897-5907.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garber M E, Mayall T P, Suess E M, Meisenhelder J, Thompson N E, Jones K A. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6958–6969. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6958-6969.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rana T M, Jeang K-T. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;365:175–185. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaeger J A, Tinoco I., Jr Biochemistry. 1993;32:12522–12530. doi: 10.1021/bi00097a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aboul-ela F, Karn J, Varani G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3974–3981. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.20.3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huq I, Tamilarasu N, Rana T M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1084–1093. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Gilst M R, Rees W A, Das A, von Hippel P H. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1514–1524. doi: 10.1021/bi961920q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su L, Radek J T, Labeots L A, Hallengra K, Hermanto P, Chen H, Nakagawa S, Zhao M, Kates S, Weiss M A. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2214–2226. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.17.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legault P, Li J, Mogridge J, Kay L E, Greenblatt J. Cell. 1998;93:289–299. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mogridge J, Legault P, Li J, Van Oene M D, Kay L E, Greenblatt J. Mol Cell. 1998;1:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakobovits A, Smith D H, Jakobovits E B, Capon D J. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2555–2561. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.6.2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cordingley M G, La Femina R L, Callahan P L, Condra J H, Sardana V V, Graham D J, Nguyen T M, Le Grow K, Gotlib L, Schlabach A J, Colonno R J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8985–8989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]