Abstract

With the rapid advancement of the Internet, emerging social media platforms facilitate real-time interaction among users, thereby rendering the impact of sentiments on behavior both faster and more complex. Analyzing and predicting the influence of sentiments on behavioral changes under various factors has become a critical issue. Grounded in the Emotions as Social Information (EASI) theory, this study conducts a comprehensive dynamic analysis of user sentimental changes from both personal and interpersonal perspectives. We employ HanLP for sentiment analysis and utilize structural equation modeling (SEM) and chi-square tests to analyze and validate the impact of sentiments on behavior. The results indicate that positive personal sentiment changes in users significantly enhance their purchase intentions. Furthermore, different users exhibit varying sentimental changes in their self-imitation behaviors. While positive emotions significantly influence users’ repetitive posting behavior, the effect of repeated video watching is less pronounced. This study, incorporating both real-time and video-time dimensions, dynamically validates that users who imitate others’ behaviors display more consistent positive emotions, providing evidence for sentimental contagion in user behaviors.

Subject terms: Computational science, Scientific data, Statistics

Introduction

With the rapid development of the internet, social media platforms have transformed the way individuals interact, fostering unprecedented online socialization1. Although these platforms support rich media such as images and emojis, text remains the primary medium for users to express opinions and emotions. On April 14, 2021, Elon Musk posted a tweet expressing optimism about Dogecoin on X/Twitter, which received over 300,000 likes and 70,000 retweets. Within 24 hours of the tweet, a surge in Dogecoin purchases caused its price to soar by approximately 80%, reaching a new all-time high. This illustrates how emotions shared online can quickly influence the behavior of others, even affecting financial markets. Such examples highlight the profound impact of emotions conveyed through social media texts in shaping user behavior, underscoring the urgency of understanding and measuring this influence. While Musk’s tweet reflects a one-to-many form of emotional influence in an asynchronous environment, synchronous platforms present a distinct dynamic where emotional contagion can occur in real time and among ordinary users. For instance, on March 27, 2024, a Bilibili livestream by content creator Mr MIDENG triggered intense real-time barrage interaction. According to third-party data from Huoshaoyun (https://www.hsydata.com/index2), over 70,000 users joined the flash sale, and there was a purchase increase of over 950% relative to normal traffic. During the livestream, viewers responded with an overwhelming volume of emotionally charged barrage comments, expressing excitement, urgency, and peer-driven encouragement to purchase. These cases highlight two crucial forms of emotional influence on social media: the broadcasted emotions of influential figures and the emergent, interactive emotional contagion among users in synchronous settings. Moreover, beyond the impact of others’ emotions, individual users’ emotions can initiate a self-reinforcing cycle; when individuals repeatedly encounter negative information, they may experience intensified negative emotions, leading to further negative behaviors. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the surge in online social activity corresponded with an increase in negative sentimental texts, which not only incited violent criminal behavior by the sender but also affected the actions of others2. Additionally, when the proportion of negative emotions, such as anger, approaches that of happiness, and the gap narrows to less than 12%, anger emerges the dominant emotion on social media, triggering collective outrage within the online community3. This indicates that behavior is influenced not only by positive emotions but also by negative ones, and this influence extends beyond the individual to others. The impact of emotions on behavior is often the result of the complex interplay of various factors, highlighting the importance of understanding their relationships to effectively guide user behavior and maintain a healthy online environment.

The Emotions as Social Information (EASI) theory is widely used to explain how emotions influence others’ reactions and behaviors in social interactions4. This theory suggests that emotions serve as a crucial and valuable source of social information. They enable individuals to gain insight into others’ perceptions, feelings, and intentions regarding various situations, thereby influencing their behavioral decisions and emotional responses. The EASI theory divides the impact of emotions on behavior into two distinct dimensions: first, from a personal perspective, it posits that an individual’s emotions lead to changes in their behavior; second, from an interpersonal perspective, it suggests that perceived emotional information from others affects one’s own emotions and behaviors. Traditional social media platforms, such as relatively static platforms like Twitter and Facebook, primarily focus on sharing text and emojis, and interactions between users are rarely in real time. Therefore, on these platforms, there is a time lag between the expression of emotions and the responses from others, making it difficult to capture real-time emotional interactions. This non-real-time interaction results in the effects of emotions on behavior being almost isolated when studied in such contexts. Existing research has accurately analyzed the impact of emotions on individual behaviors and predicted how emotions influence representative actions, such as purchase decisions5. At the same time, other studies have explored phenomena like emotional contagion to evaluate its effects on interpersonal emotional responses and behaviors6,7 .

However, emerging social media platforms such as Bilibili and Twitch combine video content with real-time barrage comment systems, enabling synchronous emotional expression and immediate feedback during interaction8. While EASI theory has been widely applied to asynchronous and controlled experimental settings involving isolated participants and static stimuli9, its applicability to real-time, dynamic environments remains underexplored. Moreover, existing studies have rarely examined self-imitation, the repeated emotional expression by the same user, as a distinct behavior from emphasis or strategic repetition, and have not simultaneously addressed interpersonal imitation. This study fills these gaps by investigating both self- and other-directed emotional imitation under the EASI framework in a synchronous barrage comment setting.

The barrage comment system enables the observation of two key emotional contagion pathways: one driven by emotionally salient video content, and the other shaped through users’ responses to others’ comments. These dual mechanisms can be interpreted through the lens of the Emotion as Social Information (EASI) theory. Specifically, the first reflects personal affective mechanisms, while the second corresponds to interpersonal pathways involving affective reactions (emotionally mirroring others) and informational effects (inferring social meaning from emotional expressions). To investigate these mechanisms in a naturalistic, high-resolution context, we focus on Bilibili, a platform whose synchronous comment system makes both pathways observable in real time. Bilibili (https://www.bilibili.com/) is a Chinese social video platform popular among young users. Its signature feature is the real-time barrage comment system, where user comments are overlaid directly on the video screen during playback. This synchronous, time-anchored interaction transforms individual viewing into a dynamic, collective experience. Unlike conventional asynchronous comment sections, barrage systems synchronize user feedback with specific video moments, amplifying the visibility and immediacy of emotional expressions. These characteristics make barrage systems a uniquely fertile environment for studying emotional contagion. The visibility of others’ reactions in real time fosters rapid emotional mimicry, while the coupling of user responses to the video timeline enables detailed tracking of affective dynamics. Importantly, this system affords a dual temporal structure, calendar and video time, which allows us to distinguish between emotion shifts driven by evolving social context and those induced by media content. Building on this framework, our study explores how user sentiments shape behavior through personal and interpersonal mechanisms. This approach connects general theories of emotional influence in social media with the specific contagion dynamics embedded in synchronous, video-integrated platforms.

Therefore, this study examines the relationship between emotions and user behavior under dual factors from both personal and interpersonal perspectives. In terms of the impact of emotions on individual behavior, it focuses on changes in users’ purchase intentions and self-imitation behaviors, while in the context of interpersonal influence, it explores changes in users’ behaviors when imitating others. The study proposes a total of eight hypotheses regarding emotions and behavior and verifies them. The first six hypotheses investigate how various emotional changes ultimately influence individual purchase intentions, the seventh focuses on the impact of emotions on self-imitation behavior, and the final hypothesis examines the influence of emotions on imitating others’ behavior.

The main contributions of this study are summarized below:

This study offers valuable theoretical and empirical insights into sentiments’ impact on social contexts. It deepens our understanding of the relationship between sentiments and behaviors, such as purchase intentions and imitation behaviors.

This dataset highlights the complex role of sentiment in short-term dynamics, providing a new perspective on its immediate impact on users’ behaviors, such as repeat viewing, commenting, and imitation of others. Specifically, we demonstrate a method for analyzing the effect of sentiment on user behavior using such a dataset.

This study demonstrates the dynamic process of sentimental contagion in both video and actual temporal time dimensions. It confirms the different effects of sentiments on self-repeated behaviors, such as video re-watching and commenting.

The components of this study are listed below. Section “Literature review”, the literature review section, introduces the preliminary knowledge, related work, and research hypotheses. Section “Methodology”, the methodology section, describes this study’s data collection, preprocess, and analysis methods. Sections “Results” and “Discussion”, the results and discussion section, show all the results obtained and the related discussions and comparisons. Section “Conclusion” is the conclusion of this study.

Literature review

The literature review part has three aspects: preliminary knowledge, related work, and research hypotheses. First, we will introduce some specific theories that can support our study. Second, we will introduce previous research relevant to our study and clarify the theoretical and empirical basis for each hypothesis in detail.

Preliminary knowledge

Sentiment analysis

In the information explosion era, the comments and feedback posted by users on different social media platforms contain rich sentimental information, which is crucial for understanding user behavior. Therefore, sentiment analysis has received widespread and sustained attention in recent years. Sentiment analysis is a natural language processing technique for extracting and analyzing sentimental information from text. It analyzes words and sentence structures in text to determine the sentimental tendencies of text (such as positive and negative). We use a sentiment analysis tool named HanLP to classify the barrage into different types: negative, positive, and neutral. HanLP was proposed by He et al. in 202110, and it is popular and reliable for analyzing the Chinese language. We use HanLP to classify sentiments and study the social impact of sentiments from both personal and interpersonal perspectives. It highlights the varied effects of sentiments from these different perspectives. We will also introduce more details about HanLP in the methodology section.

Emotions as social Information (EASI) theory

The Emotions as Social Information (EASI) theory, proposed by Van Kleef (2009)4, posits that emotional expressions function as critical social signals that influence observers’ cognition and behavior through two primary pathways: the informational pathway and the motivational pathway. In the informational pathway, individuals interpret others’ emotional expressions to infer intentions, appraisals, or evaluations, which subsequently guide their own decisions. In the motivational pathway, emotions act as social regulatory cues, eliciting conformity, compliance, or imitation based on perceived expectations or group norms. In the context of barrage-based platforms, emotional expressions embedded in real-time comments not only reflect users’ affective states but also serve as social cues that construct an informational environment for others. These cues influence how subsequent viewers interpret the video content, perceive the collective emotional climate, and decide how to respond. Such emotional signals may serve as indicators of amusement, approval, or relevance, which guide others’ expectations and reactions. This mechanism aligns with the EASI framework, which posits that emotional expressions regulate social behavior by shaping observers’ interpretations and motivations.

More detail, in the context of real-time barrage comment systems, these emotional signals are made publicly visible and synchronously broadcast to large audiences, intensifying their social impact. Studies on livestreaming and digital interactions have shown that such environments can significantly enhance emotional contagion, leading to behavioral alignment among viewers8. For instance, emotionally charged barrage comments may not only influence a viewer’s attitude toward a product (e.g., forming trust or admiration toward an influencer) but also shape their behavioral responses (e.g., repeated viewing or imitating others’ comments). This study thus extends the application of EASI theory to high-velocity online settings where emotional expressions are collectively experienced and rapidly propagated. Moreover, barrage comments used in this study possess a unique dual time structure: they are timestamped by both actual posting time and the video’s playback time. This structure enables us to track emotional fluctuations within individuals across moments and identify convergent emotional patterns among groups. Such temporal granularity provides a rare opportunity to examine short-term emotional influence and user behavior under continuous interaction conditions.

It is also important to distinguish between emotion and attitude in this framework. Emotions refer to short-term affective states, which can be triggered spontaneously by environmental stimuli. In contrast, attitudes are more stable evaluations or predispositions toward an object, such as brand favorability or trust. Although the two constructs are conceptually distinct, they are often intertwined in practice; for instance, attitudes may develop over time through repeated experiences or reinforced emotions11. This study focuses on emotional reactions observable in barrage interactions, treating them as real-time affective indicators that may carry evaluative significance. Moreover, imitative behavior may indicate a degree of affective and evaluative consistency in evaluations over time. We elaborate on the theoretical and empirical implications of imitation and repetition in the Section "User Imitation Behavior in Social Media".

Related work

In this section, we will review related research on sentiment analysis, users’ purchase intentions, and user imitation behavior on social media, point out the research gaps in these areas.

Sentiment and users’ purchase intention

The influence of emotions on human behavior, particularly purchase intentions, has been a central focus in marketing research. Extensive empirical studies have demonstrated the crucial role of emotions in shaping users’ purchase intentions and decision-making processes. Through analyzing cross-platform user-generated content (UGC), Jia et al.12 revealed how emotional factors in user reviews influence product sales through their impact on purchase intentions. In the context of social video media, the mechanism of emotional influence on users’ purchase intentions can be categorized into four key dimensions: users’ attitudes toward video content, attitudes toward influencers (video uploader), attitudes toward advertised products, and attitudes toward brands. These dimensions form a complex network of emotional influences on users’ purchase intentions. In this study we will focus on the relationship among these four factors.

First is the relationship between users’ attitudes toward video content and influencers. Research indicates that influencers have become essential elements in social media marketing13. However, influencers’ persuasive power diminishes when social network influence or advertising effectiveness is weak14. Meanwhile, in social media, users’ attitudes toward influencer-created video content are closely connected to their attitudes toward the influencers themselves. Some research focuses on how influencer-generated content and users’ attitudes toward influencers affect users’ purchase intentions. This effect occurs through enhancing consumers’ trust in branded content15. Therefore, it is important to examine the relationship between user attitudes toward video content and influencer in advertising videos.

Second is the relationship between users’ attitudes toward video content and advertised product. The EASI theory explains how emotions influence observers’ emotional states and behavioral choices through emotional contagion. Specifically, users unconsciously experience emotional resonance through various channels, including speech, music, text, and emoticons16. This emotional contagion is particularly prevalent in social media marketing. Video content marketing, due to its intuitive nature and interactivity, typically achieves the highest user engagement and propagation effects17. Thus, investigating the relationship between users’ attitudes toward in-video advertised product and video content will provides valuable insights.

Third is the relationship between users’ attitudes toward influencer and advertised product. Studies have confirmed that influencers can indirectly affect user purchase decisions through multiple dimensions, including attractiveness, expertise, credibility, and similarity18. Unlike traditional opinion leaders, social media influencers are often viewed as companions by their audience. This companion effect significantly influences user attitudes and behavioral intentions19. Research has shown that emotions affect users’ attitudes toward content creators and products, ultimately influencing purchase decisions20. Therefore, it is essential to examine the relationship between users’ attitudes toward influencers and their attitudes toward the advertised product.

Finally is the relationship between users’ attitude toward the brand, attitude toward the advertised product and their purchase intention. Research on brand attitudes, advertising product attitudes, and purchase intentions reveals that positive attitudes toward advertised products positively influence purchase intentions20. Additionally, user-generated social media content positively affects brand equity and brand attitudes, directly influencing consumer purchase intentions21. Hetet et al. demonstrated that brand innovativeness influences consumer evaluations of new products through perceived novelty, moderated by hedonic factors and price considerations22. In a social media marketing research23, empirical results show that users’ attitudes toward advertisements affect purchase intentions both directly and indirectly through brand attitudes. Therefore, examining the direct impact of these two factors on purchase intention is essential to better understand user behavior and refine marketing strategies

While existing research has revealed the significant role of emotions in commercial behavior, there remains a lack of systematic, comprehensive research on the complex mechanisms of emotional influence across different consumption scenarios. Most studies focus on examining the direct impact of sentimental changes on purchase decisions, with insufficient attention to the role of sentiments in driving repetitive behaviors such as imitation. Therefore, exploring the multidimensional mechanisms of sentimental influence holds significant theoretical value and practical implications.

User imitation behavior in social media

In recent years, mimicry behavior, particularly self-imitation and interpersonal imitation in social media environments, has received growing academic attention, though research remains limited. From a psychological perspective, imitation refers to the process of consciously or unconsciously replicating the behaviors of others, groups, or entities. Most existing studies focus on interpersonal mimicry and its effects, highlighting how others’ behaviors influence individual actions and how emotional expressions impact group dynamics. Empirical evidence has shown that mimicry during interactions can strengthen interpersonal relationships and foster trust and cooperation24. In broader social contexts, being mimicked has also been found to enhance social bonding and lead to more favorable evaluations of the imitator25. Meanwhile, words are often a way to express emotions, repeated exposure to emotionally valenced messages may reinforce cognitive or emotional alignment26.

Although these studies provide substantial empirical evidence for understanding the social influence of imitative behavior, research on consumers’ imitation behavior in social media remains relatively scarce. In particular, there is a lack of comparative studies that examine different imitative patterns from both interpersonal and individual perspectives simultaneously. This study draws on the findings of Scissors et al. on linguistic mimicry27 and proposes that similar imitation phenomena also exist in the barrage enviroment. Specifically, users repeatedly watch videos and repeatedly post the same or similar bthinkarrages, forming imitation in content or form. This distinction helps us understand how mimicry manifests in crowd-based digital interactions and how it operates as an emotion-driven mechanism within the EASI framework.

Research gaps

Therefore, existing research has obvious shortcomings in the following aspects. First, most studies focus on the direct impact of sentiments on purchasing behavior but do not fully explore the role of sentiments on users’ self-imitation behavior. Second, and more importantly, while the EASI theory provides a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding the role of emotions in social interactions, current research tends to focus solely on the impact of emotions on singular behaviors, overlooking their influence on multiple behavioral dimensions. Moreover, there remains a research gap in examining users’ imitation behavior simultaneously from both interpersonal and personal perspectives.

Against this background, our study aims to fill this gap by examining the dual impact of sentiments on self-behavior and interpersonal imitation behavior. Especially with the EASI theoretical framework, we will deeply explore how sentimental contagion drives complex user behavior. This study not only compares different self-imitation behaviors but also analyzes the dynamics of imitating others’ behaviors, thereby providing a new perspective for the existing literature and expanding the understanding of the interaction between sentiments and behaviors. To complete the research in this area, we try to study the influence of sentiments on behavior in three research questions:

How does video content influence viewers’ purchasing behaviors?

What is the relationship between self-imitating behavior (repeat viewing and repeat commenting) and sentimental dynamics?

Is there a correlation between imitating others’ behaviors (posting the same or similar comments) and sentimental reactions?

Then, based on these three questions, we will propose eight hypotheses. The specific hypotheses will be explained in detail in the next section.

Research hypotheses

The primary objective of this study is to conduct a dynamic analysis of users’ sentiment expressions on social networking platforms, drawing on both the individual and interpersonal dimensions of emotional influence as conceptualized in the EASI framework. In barrage-based environments, emotional expressions embedded in real-time comments not only reflect users’ internal affective states but also serve as socially informative cues that shape how others perceive, interpret, and respond to content. These emotional cues contribute to an informational environment that facilitates affective alignment and influences both evaluative and behavioral outcomes.

The first six hypotheses (H1a–H1f) are grounded in the personal perspective of emotional influence and examine how sentiment differences toward various stimuli (e.g., product types, creators) are associated with users’ purchasing intentions. While purchase intention is attitudinal in nature, we treat emotional expressions as proxies for underlying attitudes for the purpose of modeling. This approach is necessitated by data constraints, as our dataset does not allow empirical separation between affective and cognitive components.

Hypothesis 2 focuses on self-imitative behavior, subdivided into repeated video watching and repeated barrage commenting. These behaviors are theorized to reflect affective reinforcement, where users re-engage with emotionally salient content or their own prior expressions. Hypothesis 3 explores interpersonal imitation, defined as sentimentally aligned language reuse across users. Both forms of imitation are interpreted as manifestations of emotional contagion within the EASI framework.

We operationalize the two imitation types at the user level under individual and interpersonal perspectives, based on temporal and lexical patterns. We do not compare or analyze their interrelationship, but treat them independently as distinct manifestations of sentiment-driven behavior. This decision is motivated by both theoretical and empirical considerations. Theoretically, we follow the EASI framework in treating self-directed and socially induced emotional expressions as separate mechanisms of affective influence. Empirically, our dataset includes relatively few users who exhibit either form of imitation, and instances of users engaging in both are especially rare. Therefore, we analyze these behaviors independently, reflecting different social pathways of emotional influence.

Sentiment and purchase intention

Building on the EASI theory4, emotional expressions on social media serve not only as affective signals but also as informational cues that shape others’ cognitive evaluations. In the context of barrage interactions, such expressions are publicly visible and can influence observers’ attitudinal responses toward the video, influencer, product, and brand. While attitudes and emotions are conceptually distinct, extensive research has demonstrated that emotional cues reliably shape judgment processes, including those involved in consumer evaluations and attitude formation28. Accordingly, the first set of hypotheses (H1a–H1f) investigates how sentiment-related exposures during barrage interactions influence users’ attitudinal responses and, ultimately, their purchase intentions. Drawing on prior literature in social media marketing23 and grounded in empirical observations from user behavior and barrage data, this study explores the interrelationships among four distinct types of sentiments: users’ attitudes toward the video content, the influencer, the advertised product, and the advertised brand. These attitudinal components are theorized to jointly contribute to users’ purchase intentions, although their interactive effects are not empirically tested in this study. Although constructs such as purchase intention and content evaluation are not purely emotional, emotional expressions in user-generated comments often signal users’ evaluative stance toward content. In this study, we model such emotional expressions as proxies for attitudinal orientation, acknowledging that our dataset does not support a fine-grained separation between affective and cognitive components. This modeling assumption allows us to examine associations between sentiment expressions and downstream behavioral intentions, while acknowledging theoretical boundaries.

The specific content of each hypothesis (H1a to H1f) is detailed below.

Attitudes toward video content have a positive impact on attitudes toward influencers.

Attitudes toward video content have a positive impact on attitudes toward the product.

Attitudes toward influencers have a positive impact on attitudes toward the product.

A positive attitude toward the product positively impacts purchase intention.

Attitudes toward the brand have a positive impact on attitudes toward the product.

A positive attitude toward the brand positively impacts purchase intention.

The first six hypotheses aim to clarify how internalized sentiment responses, shaped by barrage-mediated emotional expressions, translate into self-driven behavioral intentions such as purchase intention.

Next is the section on research and hypotheses on user’s imitation behavior. We will also focus on sentiment, how it affects users’ self-mimicry behavior, and how it affects their ability to imitate others.

Sentiment and imitation Behavior

As mentioned above, the current research on Bilibili barrage is extensive, yet limited attention has been paid to users’ imitation behaviors, particularly concerning emotional dynamics. Based on the barrage comment data collected in this study, we examine how sentiment-related expressions relate to two types of imitation: self-imitation and imitation of others.

On the one hand, this study explores the emotional dimensions of self-imitation behavior. Users on interactive video platforms often engage with content in repetitive ways, such as rewatching the same video or posting multiple barrage comments. These self-imitative behaviors may be linked to the user’s emotional engagement with the content. Drawing on the EASI model, which emphasizes the social and behavioral consequences of emotional expression, we examine whether such repetitive engagement is associated with the sentiment expressed in user comments. This leads to the following hypothesis:

-

H2.

Users who repeatedly watch videos or post barrage comments are likelier to post positive sentimental comments.

On the other hand, this study also examines how users imitate others’ expressions, especially in barrage environments. Here, imitation of others’ behavior is defined as posting the same or similar barrage comments as those previously observed from other users. Importantly, we conceptualize this not as mechanical mimicry, but as affectively motivated behavior. Drawing on emotional contagion theory29, individuals tend to unconsciously align their emotions with those expressed by others, often through subtle cues like facial expression, tone, or, in this case, language. In social media, such linguistic convergence has been recognized as a manifestation of affective alignment. Furthermore, the EASI model suggests that emotional expressions serve as social signals that influence observers’ judgment and behavior. Thus, imitating language with emotion can be viewed as an observable trace of sentiment contagion. Based on this, we propose

-

H3.

Users who have posted the same or similar barrage are likelier to have a positive sentimental tendency.

Thus far, within the framework of the EASI theory, this study has explored the influence of users’ sentiments on their purchase intentions, the correlation between self-imitative behaviors and sentimental tendencies, and how emotional contagion manifests through the imitation of others in online interactions, considering both intrapersonal and interpersonal perspectives. Accordingly, we propose eight hypotheses. While both self- and other-directed imitative behaviors are examined, this study does not attempt to compare the two or analyze their potential interrelationship due to data limitations. Each type of imitation is treated independently in the current analysis. In the next section, we introduce the methods used in this study in detail.

Methodology

Data collection

This section will provide a detailed description of the data collection platform, data collection methods, and preprocessing procedures, as well as the research classification methods used to test the hypotheses.

The data for this study is sourced from Bilibili. Bilibili is popular in Chinese social media due to its rich user-generated content and high interactivity, particularly its unique “barrage” commenting feature. Barrage is a special type of text comment in which the text flies across the screen, like bullets appearing before the audience. These comments are highly relevant to the current video content, stimulating viewers’ emotional engagement while providing uniform feedback30. This mechanism allows viewers to repeatedly post barrage comments to express their emotions and to rewatch videos to experience the emotions of other viewers, thereby creating a unique environment for emotional diffusion. Therefore, the distinctive features of the Bilibili platform provide a rich data source for this study, particularly suitable for exploring the influence of emotion on user behavior, such as repeated viewing and imitative behavior.

In this study, we selected a highly representative video from Bilibili as the focal point of analysis. The video was uploaded by the influential creator Daoyuesheshiyuji, and ranked first in overall popularity in December 2022, with a cumulative view count exceeding 1.35 billion. Its content centers on regional Chinese cuisines and cultural narratives, attracting a broad and diverse audience. The video also includes integrated product sponsorship by Toyota, featuring its model WILDLANDER, which provides a natural context for examining user sentiment and purchase intention. We focused on this single, high-engagement video to ensure analytic consistency and control for potential confounding factors such as content type, product category, or influencer characteristics. While we acknowledge the limitation of using a single dataset, the selected video’s broad appeal and rich behavioral data, especially in terms of repeated, same, and similar barrage comments, make it particularly suitable for studying real-time emotional and imitative behaviors on the platform.

We used Python 3.10 to obtain barrage data from the source webpage of Bilibili. We collected barrage within 30 days after the video was released. Each barrage includes the user ID, the barrage content, the specific date of publication, and the timestamp indicating the video’s playback position at the time of barrage posting. This timestamp information is crucial for tracking the changes in users’ emotional responses during video playback. Moreover, the data not only reflects single or multiple comments from the same user but also allows us to determine, via the timeline, whether users rewatched the video. Therefore, such a dataset provides an important basis for studying the interaction between emotion and user behavior.

Data preprocess

During the data preprocessing stage, we removed duplicates, blank entries, and invalid data (e.g., comments consisting solely of numbers or punctuation) to ensure the accuracy of our study results. After data cleaning, 50,937 valid barrage remained for next analysis. Then, we invited three Bilibili users to conduct sentiment annotation on a portion of the randomly selected barrage data, categorizing the sentiments as positive, negative, and neutral, to verify the accuracy of our sentiment analysis tool. The specific process is as followed. First, we randomly selected 2,000 barrage comment samples from the preprocessed data. Then, three loyal Bilibili users, who watch videos almost daily, were invited to annotate the texts. All three annotators are native Chinese speakers. After watching the videos, each user categorized the texts into three sentiment categories: positive, negative, and neutral. Meanwhile, we first calculated the Fleiss’ Kappa coefficient (k=0.5183) among three annotators to ensure annotation quality. This indicates moderate inter-rater agreement. Based on this preliminary result, we adopted the following strategy to determine the final labels: If all three annotators agreed on the label, it was accepted as the final result; when two out of three annotators agreed, the majority label was adopted as the final label; and for cases where all three annotators disagreed, a consensus was reached through group discussion to determine the final label. The final sentiment label for each barrage was determined based on the consensus of the three annotators. This systematic approach ensures both annotation efficiency and data quality reliability.

To test the hypotheses proposed in this study, we used different classification methods based on the different dimensions of the barrage data. First, for the first six hypotheses regarding the significant impact of user sentimental changes on their purchase intentions, we classified the barrages based on keywords, examining the relationship between changes in users’ attitudes towards different targets (video content, influencers, brands, and products) and their purchase intentions. In 2019, researchers already classified influencer-generated content using a two-dimensional framework: informational value and entertainment value15. This framework empirically validates how different content types affect brand trust and purchase intention. This aligns with our study methodology, which categorizes barrage comments based on their targets: video content, influencers, brands, and products. This classification approach helps understand the core characteristics of user-generated content and provides a theoretical foundation for exploring the causal relationship between content types and consumer responses. Second, to test the H2 that positive emotional changes significantly impact users’ self-imitative behavior, we focused on analyzing whether users repeatedly watched videos and posted barrages as indicators of self-imitative behavior.

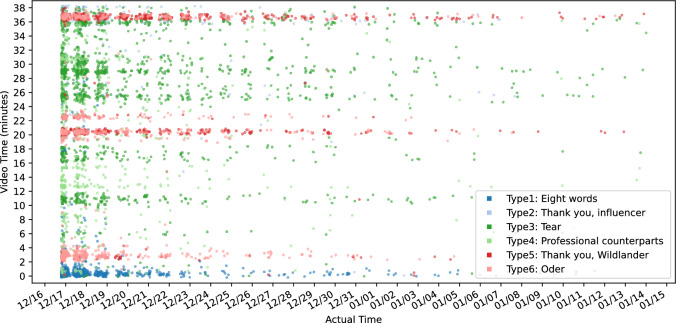

Finally, to test Hypothesis 3, which examines users who post the same or similar barrage comments, we first identified representative barrage types that explicitly referenced identifiable targets likely to induce imitation, namely, (1) influencers, (2) video content, and (3) advertised products or purchase intentions. We removed stop words and punctuation, applied word segmentation using SnowNLP31, and extracted the top 20 high-frequency content words. These were manually grouped into semantically coherent categories based on contextual usage. Among them, we selected six types, two for each imitation-relevant domain, that were both frequent and semantically specific, aligning with our theoretical framework, as presented in Table 1. To assess the clarity and coherence of these categories, two native Chinese speakers independently reviewed the six types and confirmed that they intuitively aligned with their respective target categories. We also expanded them with semantically similar variants observed in the data. This refinement process ensured internal consistency and relevance to the imitative behaviors under investigation. The resulting classification framework was designed to capture instances of repeated or similar barrage comments as behavioral indicators. As our classification was based on a representative keyword framework, comments that did not include any of the selected or semantically similar words were not considered as imitative instances in this analysis. Based on Table 1, we combined each barrage comment’s release timestamp with its corresponding video segment to generate Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, the distribution of identical or similar barrage comments also indicates that the distribution of similar types of barrage comments is identical, and the distribution of barrage comments is closely related to the video content. The distribution of blue dots on influencers is concentrated at the beginning of the video, with a small portion appearing at the end. The green color of video content almost runs through the entire video and is scattered in all places. The red color conveys advertising products and purchase intentions. It is concentrated at the beginning and end of the video, when the advertising products appear. The distribution shown in Figure 1 provides empirical support for our investigation of user imitation behaviors, specifically the patterns of posting the same or similar barrage comments. These observed distributions validate the feasibility of studying such imitative interactions among users.

Table 1.

Representative imitation barrage. Six representative types of similar or the same barrage comments targeting three different objects (influencer, video content, and product) were selected for analysis to investigate users’ imitation behavior.

| Category | Type | Content | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influencer | 1 | Eight words | The slogan proposed by the influencer |

| 2 | Thank you, influencer | Expressing appreciation to influencers | |

| Content | 3 | Tear, crying | Expresses moving sentiments |

| 4 | Professional counterparts | Comments based on video content | |

| Product | 5 | Thank you, Wildlander | Expressing gratitude to Wildlander |

| 6 | Order | Expressing the user’s purchase intention |

Fig. 1.

The distribution of imitating others’ behavior barrage. The distribution of six of the same or similar barrage comments made during the imitative process is illustrated across two distinct temporal dimensions: video and actual time. The receipt collection time is one month from the December 16, 2022, video release date. The dynamic process of audience sentimental contagion is evident from the actual time distribution depicted. Furthermore, the moments in the video when comments targeting various subjects emerge are strongly correlated with the video’s content. The barrage types are divided into influencer (types 1 and 2), video content (types 3 and 4), and advertised products and purchase intention (types 5 and 6).

Analysis methods

This study mainly used three research methods: first, the sentiment analysis model that runs through the study; second, the structural equation model (SEM) used to test the first six hypotheses of H1; and finally, the chi-square test to verify hypotheses 2 and 3.

Sentiment analysis tool HanLP

Choosing an appropriate sentiment analysis tool is crucial for our study. SnowNLP and HanLP10 are widely recognized among Chinese sentiment analysis tools. We used the labeled data, as discussed in detail in the data processing section, to compare their suitability. HanLP showed a higher agreement rate with human annotations. Therefore, we selected HanLP for sentiment classification in this study. HanLP excels in sentiment analysis by leveraging deep learning models, such as Transformers, trained within a multi-task learning framework. This enables it to generate sentiment scores ranging from -1 to 1 for Chinese text, capturing both sentiment polarity and intensity through a refined scoring system. Based on the sentiment scores computed by HanLP, we classified barrage comments into negative, neutral, and positive categories. Rather than applying a fixed threshold (e.g., 0), we adopted a tertile-based classification strategy. This approach partitions the score distribution into three equally sized segments, enabling balanced category representation.

Fixed thresholds are prone to misclassifying sentiment samples with varying intensities, especially in cases where the sentiment distribution is skewed. For example, when positive comments dominate, mildly positive messages may be incorrectly labeled as neutral. In contrast, distribution-aware thresholds adjust dynamically to the actual data distribution, thus more accurately reflecting users’ emotional expression across different video contexts. This method is supported by Kiritchenko et al.32, who demonstrated that distribution-based thresholds outperform fixed cutoffs, particularly in imbalanced sentiment corpora. Our approach is thus well-suited for dynamic, user-generated content platforms like Bilibili, where emotional expression varies significantly across videos. To visualize the sentiment distribution, we show the score histogram in Figure 2. Based on tertile thresholds, scores below 0.4680 were classified as negative, those between 0.4680 and 0.7031 as neutral, and those above 0.7031 as positive. Meanwhile, this method enables flexible adaptation across videos with varying emotional tone, making it well-suited for dynamic, user-generated content platforms like Bilibili.

Fig. 2.

Sentiment distribution of the barrage comments. Based on the tertile distribution, sentiments of barrage comments are classified as negative (-1 to 0.4680), neutral (0.4680 to 0.7031), and positive (0.7031 to 1).

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a statistical technique combining causal relationships and multivariate analysis to estimate relationships between multiple latent variables simultaneously. It originated in psychology and the social sciences and is used to test hypotheses and handle complex theoretical models. SEM’s main strength is its ability to analyze multiple causal relationships simultaneously, making it highly flexible and well suited for studying latent variables.

Our study performed SEM analysis using two software packages, SPSS and SPSS AMOS, to verify the relationship and size between the first six hypotheses. The main purpose of the first six hypotheses is to explore how users’ sentimental changes toward different goals affect their purchase intentions. Therefore, SEM is very suitable for our study questions.

Chi-square test

The chi-square test is a statistical method used to determine if there is a significant association between categorical variables. It compares the observed frequencies in a contingency table to the expected frequencies to test for independence or goodness of fit.

Our study uses the chi-square test to evaluate hypotheses 2 and 3, specifically examining the relationship between different imitative behaviors and sentiments. Hypothesis 2 focuses on self-imitation behaviors, while Hypothesis 3 examines the mimicry of others’ behaviors. The chi-square test helps assess whether these behaviors are significantly associated with different sentimental states.

Results

Based on the data from the video containing sponsor information, as shown in Figure 3, H1a through H1f are fully supported. Specifically, the datset confirms the relationships between the following variables: user sentiment towards video content positively influences the sentiment of influencers who post the videos (H1a). Additionally, the attitude toward video content positively impacts product attitude (H1b) and the attitude of influencers toward products (H1c). Furthermore, a positive attitude toward advertising the product enhances purchase intention (H1d). Brand attitude positively influences the attitude toward advertising products (H1e), and a positive brand attitude also strengthens purchase intention (H1f).

Fig. 3.

SEM test result for H1a-H1f. The results indicate that user sentiment toward video content positively influences the sentiment of influencers who post the videos (H1a). Additionally, attitude toward video content positively impacts product attitude (H1b) and the attitude of influencers toward products (H1c). Furthermore, a positive attitude toward advertising the product enhances purchase intention (H1d). Brand attitude positively influences the attitude toward advertising products (H1e), and a positive brand attitude also strengthens purchase intention (H1f). These findings illustrate the process by which sentimental dynamics among influencers, video content, brands, and advertised products culminate in influencing personal purchase intention.

For hypotheses 2 and 3, chi-square tests were conducted. Hypothesis 2 examines whether users exhibiting self-imitation behaviors (repeated video viewing or barrage commenting) are more likely to make positive sentimental comments due to the self-reinforcing theory in the echo room effect. In self-imitation behavior, the actions of repeatedly watching videos and repeatedly posting barrage comments yield different results. The analysis of user data for repeated barrage commenting (Table 2) shows that this aspect of Hypothesis 2 is rejected (p > 0.05). Detaily, as shown in Table 2, the chi-square tests reveal a statistically significant association between sentiment distribution and the behavior of repeatedly posting barrage comments ( ). In contrast, the relationship between repeated video watching and sentiment was not statistically significant (

). In contrast, the relationship between repeated video watching and sentiment was not statistically significant ( ). This suggests that different forms of repetitive behavior may have different emotional implications. While repetitive commenting appears closely linked with affective expression, repeated viewing may be influenced by non-emotional factors such as content navigation or passive engagement. These interpretations are discussed in detail in Section “Discussion”. Meanwhile, the distribution of self-imitation behaviors is shown in Figure 4.

). This suggests that different forms of repetitive behavior may have different emotional implications. While repetitive commenting appears closely linked with affective expression, repeated viewing may be influenced by non-emotional factors such as content navigation or passive engagement. These interpretations are discussed in detail in Section “Discussion”. Meanwhile, the distribution of self-imitation behaviors is shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Self-imitation’s chi-square test. To explore the sentimental variations associated with users’ self-imitation behavior, we analyzed the results using the chi-square test. Our findings reveal a disparity between the behaviors of repeatedly watching videos and repeatedly posting comments, indicating that distinct sentimental inclinations characterize various forms of self-imitation behaviors.

| User type | Negative (Observed) | Neutral (Observed) | Positive (Observed) | Chi-square value | P value | Expected frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users without repetitive behavior | 8,070 | 7,871 | 7,514 | 22.34 | *** |  |

| Users who repeatedly post barrage | 7,086 | 7,299 | 7,672 | 21.78 | *** |  |

| Users who repeatedly watch video | 1,811 | 1,795 | 1,839 | 0.39 | 0.82 |  |

Note: ***: P<0.001, **: P<0.05

Fig. 4.

Sentiment Distribution Among Users with Different Repeated Behavior. This study examines the distribution of self-imitation users versus others and analyzes the specific sentimental distributions associated with each user type. The results show that repeat barrage posters and repeat video watchers together account for 54% of all users. Non-repetitive users exhibit the highest proportion of negative sentiment and the lowest proportion of positive sentiment. In contrast, repeat barrage posters display the highest proportion of positive sentiment and the lowest proportion of negative sentiment. For repeat video watchers, although positive sentiment is the most prevalent, they also have the lowest proportion of neutral sentiment, and the gap between negative and positive sentiment is only 0.5%.

Hypothesis 3 investigates whether users who imitate others’ barrage comments (posting the same or similar content) demonstrate consistent sentimental tendencies. Based on the analysis results (Table 3), Hypothesis 3 is accepted (p < 0.05). Figure 5 shows the distribution of imitation of others’ behavior.

Table 3.

Imitation’s chi-square test. We applied the chi-square test to investigate the sentimental shifts among users who engaged in imitative behavior. The findings suggest that users who post similar or identical comments tend to have more positive sentimental states.

| User type | Positive (Observed) | Negative (Observed) | Neutral (Observed) | Chi-square value | P value | Expected frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-normal barrage | 14,423 | 7,573 | 12,796 | 103.32 | *** |  |

| Post- mimicry barrage | 2,544 | 3,257 | 4,229 | 421.59 | *** |  |

Note: ***: P<0.001, **: P<0.05

Fig. 5.

Sentiment Distribution Among Non-Repetitive Users. This study examines the distribution of imitative others users versus others and analyzes the sentimental distributions associated with imitative behavior. The results indicate that users who post mimicry barrages (same or similar barrage comments) are relatively few, accounting for only 19.7% of the total. In comparison, regular barrage posters constitute the majority at 80.3%. Regular barrage posters exhibit the highest proportion of negative sentiment and the lowest proportion of positive sentiment. In contrast, mimicry barrage posters exhibit the highest proportion of positive sentiment (42.2%), which is more than 1.66 times the proportion of their negative sentiment, making them the most positively inclined user group.

Discussion

The findings indicate that first six hypotheses regarding the impact of emotions on users’ purchase intention are supported and consistent with previous research results. First, the data from the video with advertisements confirms that positive sentiment toward video content positively influences the sentiment toward both the influencers and the advertised products featured in the video, which are the same as the previous studies13,19. This one highlights the importance of video content in social media marketing. Second, the datasets validate that positive sentiment toward the advertised products directly and positively impacts users’ purchase intentions, which is consistent with H1d and the findings of Mukherjee et al.23. This highlights the link between user attitudes toward products and their purchasing behaviors. Third, the SEM analysis of the video sponsored by Toyota reveals that positive brand attitudes significantly enhance users’ attitudes toward the advertised products, supporting H1e. This result is consistent with the findings of Hetet et al.22, reinforcing the idea that brand perception plays a crucial role in shaping product attitudes. In addition, users’ attitudes toward the brand directly impact their purchase intentions, as proposed in H1f, and indirectly influence these intentions through their attitudes toward the products.

All first six hypotheses indicate that the sentiments directed at different objects, such as video content, influencers, products, and brands, interact and collectively influence users’ behavior, ultimately shaping their purchasing decisions. This result supports H1a-H1f and aligns with understanding how social media markets function. These findings illustrate the role of positive sentiments in shaping users’ perceptions within the social media ecosystem. Meanwhile, such results indicate that the intensity and relationship of the impact of users’ sentimental changes for different objects on purchase intention are inconsistent. This shows that, in social media marketing, marketers should adopt multi-dimensional and targeted strategies and reasonably weigh the focus of each dimension to achieve the best results.

Additionally, our analysis reveals that the impact of emotions on different types of self-imitation behaviors among users is inconsistent with Hypothesis 2. The repetitive behavior of self-imitation in H2 is categorized into two types: repeatedly watching videos and posting barrage comments. A chi-square test was conducted on the data for these two types of repetitive and regular user behavior. This categorization aims to assess whether different forms of repetitive behavior have varying impacts on the results. As shown in Table 2, it is important to highlight that different types of repetitive behavior yield varying sentiment analysis results. On the one hand, there is a statistically significant correlation between users who engage in self-imitation behavior, particularly those who repeatedly post barrage comments, and their likelihood of posting positive sentimental comments. This indicates that users who frequently post barrage comments are more inclined to express positive sentiments. However, the results of the repetitive behavior of repeatedly watching videos tell a little different story. Although the distribution of users who repeatedly watch videos is similar to those who post comments, the chi-square test yielded a P-value greater than 0.05. This suggests insufficient evidence for a significant correlation between repeated video viewing and sentiment. Studies have already demonstrated a strong connection between sentiment and re-watching video behavior33. However, such a relationship was not reflected in our study. Several explanations may account for this discrepancy. One explanation is the instrumental view. Users may repeatedly watch videos to obtain specific information, instructions, or low-involvement entertainment, independent of emotional engagement. This perspective aligns with Wang and Tchernev’s34 findings that media multitasking is primarily driven by cognitive or habitual needs, while emotional gratifications, though present, tend to arise as unintended byproducts rather than deliberate goals. Repeated media use, therefore, may reflect goal-oriented or routine behaviors rather than affective states. Another explanation is passive engagement. Repeated viewing may reflect habitual exposure or background use rather than affective involvement. On platforms like Bilibili, users often allow videos to auto-play or use them as ambient content, resulting in minimal emotional investment despite high viewing frequency. This aligns with Vorderer et al., who argue that enjoyment depends on active user engagement, such as empathy, presence, and interest, without which emotional responses are unlikely to emerge35.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that positive emotions indeed impact imitation behaviors among users of Hypothesis 3. The chi-square test results in Table 3 confirm that users who imitate others are statistically more likely to post positive comments. This finding aligns with the theory of imitation behavior and prosocial relationships25, emphasizing the importance of sentimental connections between individuals in fostering prosocial behavior. Additionally, prosocial behavior helps strengthen ties between individuals and groups, thereby facilitating the formation of closer social networks.

Overall, these results indicate that emotions influence both personal behavior and interpersonal interactions. The correlation between emotions and different types of self-influence varies. Positive emotions interact through video content, influencer attitude, brand attitude, and product attitude, ultimately positively impacting users’ purchase intention. Additionally, positive emotions promote self-imitative behaviors, particularly in repeated commenting, though their effect on repeated video watching remains unclear. Finally, positive emotions are positively correlated with imitation behaviors among users.

Limitation and future direction

This study also has several limitations. First, it relies on a barrage appearing in videos, which requires a substantial volume of comments to effectively observe the same user’s sentimental changes and imitative behaviors. Due to time and resource constraints, this study focused on a single video with over 50,000 comments. And, we acknowledge that data from a single video may not fully capture the extensive diversity of user behaviors and emotional responses. Future research should consider expanding the data collection to include multiple videos with consistent characteristics. Specifically, videos with identical thematic content, brand presence, and product information. This would enable a more comprehensive analysis of emotional response patterns and behavioral variations across an interconnected series of videos while maintaining controlled variables.

Second, the study examines users’ comments and sentiment changes without incorporating demographic information such as gender, age, and region. While such demographic data would enrich our findings, these limitations stem from Bilibili’s platform constraints and privacy protocols. The platform does not publicly provide detailed demographic information, and users have the option to set such data as private. Moreover, these details are protected as sensitive user information and are not accessible during barrage collection. Therefore, we suggest that future research could explore incorporating demographic information if more data becomes available, particularly through surveys or collaborations with the platform.

Third, this study focuses on short-term emotional changes and user behavior patterns after video release. This research scope was chosen based on data availability constraints and our understanding of user behavior characteristics on video platforms. Research as early as 2007 has demonstrated that video content’s influence and user engagement follows a clear temporal decay pattern: user comments increase rapidly in the initial period after video release when engagement reaches its peak, and these early interactions critically impact the content’s subsequent diffusion trajectory, followed by a gradual decrease in commenting frequency until stabilization or complete cessation36. Based on this consideration, we collected danmaku data within one month of the video’s release as the foundation for analysis. While this one-month data collection period limited the study’s temporal scope, it ensured data continuity and completeness, avoiding potential issues of data loss and sample attrition common in longitudinal studies. Meanwhile, future research could focus on video series to track long-term emotional changes, which would provide insights into sustained user engagement patterns.

Finally, our sentiment classification method and granularity using HanLP may struggle with sarcasm, ambiguity, and domain-specific language, limiting its precision. Although we validated tool choice through comparison with labeled data, further refinement using hybrid models or manual annotation could improve accuracy. Additionally, the behavioral proxies used to represent imitation, such as repeated commenting or lexical similarity, are indirect and may not fully capture user intent. Future studies could enhance construct validity by incorporating experimental methods and multi-modal behavioral data.

Conclusion

This study aims to explore the impact of sentiments on users’ self-related behaviors, including purchase intentions, repetitive behavior, and imitation of others, with a focus on short-term dynamics in a social media environment. The results indicate that sentiments significantly influence users’ purchase intentions, their tendency to repeatedly post comments, and their likelihood of mimicking others’ barrage behavior.

Beyond empirical findings, this study proposes a novel classification of short-term repetitive behaviors into multiple types. This data-driven approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the interaction between sentiment and behavior, and it extends the application of the EASI theory in real-time, user-generated environments.

These findings have important implications for social media marketing. Practitioners should pay closer attention to users’ emotional dynamics in interactive environments and adopt multidimensional strategies to enhance user participation. Specifically, strategies that account for both emotional expression (e.g., barrage sentiment) and user behavior (e.g., repetition or imitation) may better capture attention and stimulate engagement.

However, this study has certain limitations. The data were collected from a single platform, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider cross-platform and cross-cultural differences in how sentiments influence user behavior. In addition to data scope, this study also faces several methodological and theoretical constraints, such as the granularity of sentiment classification, the behavioral proxies used to represent imitation and repetition, and the applicability of the EASI framework to real-time barrage environments.

In summary, this study advances our understanding of how emotions shape user behavior in social media settings, contributes to the refinement of sentiment-behavior frameworks, and provides actionable insights for both researchers and industry practitioners.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST SPRING Grant Number JPMJSP2124 and JST-Mirai Program Grant Number JPMJMI23B1, Japan.

Author contributions

Q.W. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the study. Q.W. and L.L. were responsible for executing the experiments and data collection. S.J. and M.Y. were jointly involved in reviewing and revising the first draft.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Most can be retrieved from the Bilibili website, except for deleted comments.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Khan, M. L. Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on youtube?. Computers in human behavior66, 236–247 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin, F. et al. Unfolding the determinants of covid-19 vaccine acceptance in china. Journal of medical Internet research23, e26089 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan, R., Xu, K. & Zhao, J. An agent-based model for emotion contagion and competition in online social media. Physica a: statistical mechanics and its applications495, 245–259 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Kleef, G. A. How emotions regulate social life: The emotions as social information (easi) model. Current directions in psychological science18, 184–188 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.He, Z. et al. Influence of emotion on purchase intention of electric vehicles: a comparative study of consumers with different income levels. Current Psychology42, 21704–21719 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin, F. et al. Sentiment mutation and negative emotion contagion dynamics in social media: A case study on the chinese sina microblog. Information Sciences594, 118–135 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara, E. & Yang, Z. Measuring emotional contagion in social media. PloS one10, e0142390 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng, L. M., Duan, S., Zhao, Y., Lü, K. & Chen, S. The impact of online celebrity in livestreaming e-commerce on purchase intention from the perspective of emotional contagion. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services63, 102733 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkinson, B. & Manstead, A. S. Current emotion research in social psychology: Thinking about emotions and other people. Emotion Review7, 371–380 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, H. & Choi, J. D. The stem cell hypothesis: Dilemma behind multi-task learning with transformer encoders. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 5555–5577 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021).

- 11.Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M. & Nyer, P. U. The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the academy of marketing science27, 184–206 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia, Y., Feng, H., Wang, X. & Alvarado, M. “customer reviews or vlogger reviews?’’ the impact of cross-platform ugc on the sales of experiential products on e-commerce platforms. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research18, 1257–1282 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi, Y., Lim, W. M., Jagani, K. & Kumar, S. Social media influencer marketing: foundations, trends, and ways forward. Electronic Commerce Research 1–55 (2023).

- 14.Rossman, G. & Fisher, J. C. Network hubs cease to be influential in the presence of low levels of advertising. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences118, e2013391118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lou, C. & Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising19, 58–73. 10.1080/15252019.2018.1536847 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer, A. D., Guillory, J. E. & Hancock, J. T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences of the United States of America111, 8788 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinerean, S. Content marketing strategy: Definition, objectives and tactics. Expert journal of marketing5, 92–98 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashraf, A., Hameed, I. & Saeed, S. A. How do social media influencers inspire consumers’ purchase decisions? the mediating role of parasocial relationships. International Journal of Consumer Studies47, 1416–1433 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung, J., Shim, S. W., Jin, H. S. & Khang, H. Factors affecting attitudes and behavioural intention towards social networking advertising: a case of facebook users in south korea. International journal of Advertising35, 248–265 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee, K. & Banerjee, N. Effect of social networking advertisements on shaping consumers’ attitude. Global Business Review18, 1291–1306 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schivinski, B. & Dabrowski, D. The effect of social media communication on consumer perceptions of brands. Journal of Marketing Communications22, 189–214 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hetet, B., Ackermann, C.-L. & Mathieu, J.-P. The role of brand innovativeness on attitudes towards new products marketed by the brand. Journal of Product & Brand Management29, 569–581 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee, K. & Banerjee, N. Social networking sites and customers’ attitude towards advertisements. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing13, 477–491 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Steenaert, B. & Van Knippenberg, A. Mimicry for money: Behavioral consequences of imitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology39, 393–398 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Kawakami, K. & Van Knippenberg, A. Mimicry and prosocial behavior. Psychological science15, 71–74 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zajonc, R. B. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology9, 1 (1968).5667435 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scissors, L. E., Gill, A. J. & Gergle, D. Linguistic mimicry and trust in text-based cmc. In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work, 277–280 (2008).

- 28.Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P. & Kassam, K. S. Emotion and decision making. Annual review of psychology66, 799–823 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T. & Rapson, R. L. Emotional contagion. Current directions in psychological science2, 96–100 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, W., He, Z. & Liu, M. An empirical study of the influencing factors on user experience for barrage video website–a case study of bilibili. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 310–321 (Springer, 2021).

- 31.Wang, R. Snownlp: Simplified chinese text processing. https://github.com/isnowfy/snownlp (2013). Accessed: March 11, 2024.

- 32.Kiritchenko, S., Zhu, X. & Mohammad, S. M. Sentiment analysis of short informal texts. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research50, 1–31 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim, J. S., Choe, M.-J., Zhang, J. & Noh, G.-Y. The role of wishful identification, emotional engagement, and parasocial relationships in repeated viewing of live-streaming games: A social cognitive theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior108, 106327 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, Z. & Tchernev, J. M. The, “myth’’ of media multitasking: Reciprocal dynamics of media multitasking, personal needs, and gratifications. Journal of communication62, 493–513 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vorderer, P., Klimmt, C. & Ritterfeld, U. Enjoyment: At the heart of media entertainment. Communication theory14, 388–408 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu, F. & Huberman, B. A. Novelty and collective attention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences104, 17599–17601 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Most can be retrieved from the Bilibili website, except for deleted comments.