Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) remains a challenging condition to manage traditionally in clinical practice, and despite improvements in digital health, its impact on clinical outcomes remains uncertain.

Objective

This study aimed to assess the feasibility of a structured digital-blended follow-up for patients undergoing AF ablation, incorporating electronic patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) while evaluating its impact on the timing of recurrence diagnosis and reintervention.

Methods

In this retrospective observational study, we included patients enrolled in a structured 2-year digital program starting in January 2021. This featured a Web platform for physicians to record clinical variables and a patient-centered mobile application to report PROM (Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life [AFEQT] and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS]). Clinical outcomes were compared with those from a retrospective conventionally managed cohort (2017–2020) after propensity score matching (n = 363 per group).

Results

Until May 2024, 421 patients were enrolled (mean age: 60.9 years; 33.0% female). Over a median follow-up of 546 days, 64% of the patients used the application monthly, and completeness rates for AFEQT and PROMIS questionnaires were 80% and 50%, respectively. At 12 months, significant improvements were observed for AFEQT and PROMIS scores (cognitive and physical function, anxiety, and depression). Arrhythmia recurrence significantly influenced the rates of changes for AFEQT, depression, and physical function (P < .05 for interactions). Digital follow-up was associated with a shorter time until atrial tachycardia or AF recurrence (hazard ratio 1.45, P = .019) and antiarrhythmic intervention (hazard ratio 1.65, P = .022).

Conclusion

Systematic electronic PROM collection after AF ablation is feasible in clinical practice. Structured digital-blended integrated care guarantees continuity of AF management and supports earlier detection and treatment of recurrences.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Digital health, Mobile health, Patient-reported outcomes, Quality-of-life

Graphical abstract

Key Findings.

-

▪

A structured digital-blended follow-up program for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation, including a systematic electronic collection of patient-reported outcome collection, is feasible with high adherence and completeness rates.

-

▪

Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System scores improved significantly after ablation and was adversely affected by arrhythmia recurrences.

-

▪

Digital follow-up enabled earlier detection of arrhythmia recurrences and more timely antiarrhythmic interventions than conventional care.

-

▪

This study supports the integration of digital health tools into value-based and patient-centered AF care.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an increasingly prevalent arrhythmia in adults, with high morbidity and a significant burden on health care services.1,2 In selected patients, a rhythm control strategy reduces cardiovascular mortality and heart failure hospitalizations,3 and catheter ablation is a well-established rhythm control treatment that effectively decreases AF burden and significantly improves quality of life (QoL) in patients with symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AF.4,5 The conventional care model for these patients has traditionally been physician centered, but a recent shift has moved toward a more patient-centered approach. Recent advancements in digital health care have enabled the development of tools to support the transition to multidisciplinary integrated care, as recommended by the American (Comprehensive Care)6 and the European AF guidelines (AF-CARE pathway).1 Although survival and hospitalization outcomes are commonly documented in registries and clinical AF trials, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) remain infrequently assessed despite growing recognition of their importance in this disease management.7,8 Additionally, there are conflicting results regarding the clinical impact of including digital tools in the follow-up of patients after AF ablation. Several models for integrated care have been proposed with mixed results (nurse led vs cardiologist led), probably reflecting different methodologies.9,10

We aimed to describe a real-world implementation of a digital-blended follow-up of patients after AF ablation while assessing the feasibility of measuring electronic PROMs throughout the follow-up and evaluating the impact of recurrence on different QoL questionnaires. We further compared the time until arrhythmia recurrence and reintervention of a digital-blended follow-up with conventional patient management.

Materials and methods

Study design

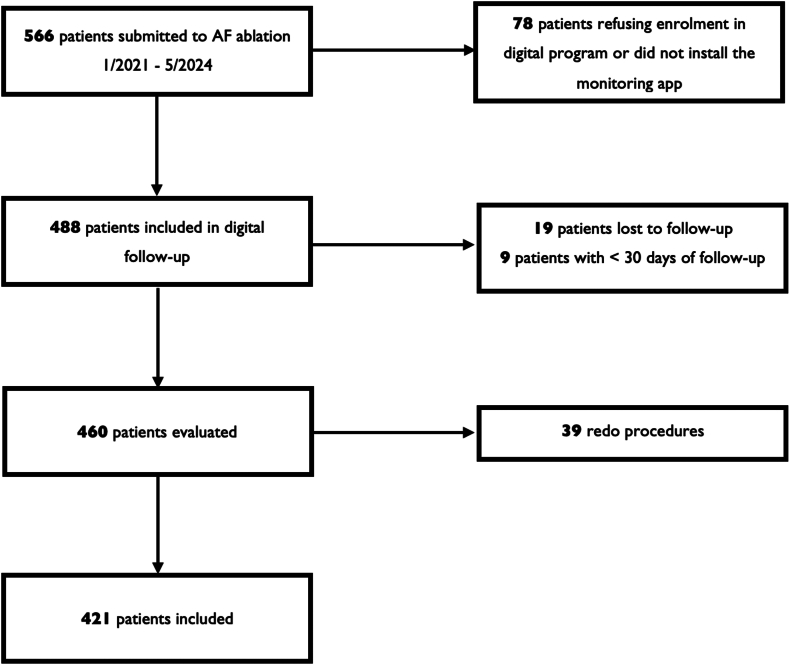

This was a nonrandomized, single-center, retrospective, observational study of patients submitted to AF ablation in a Portuguese tertiary hospital center. Patients older than 18 years with paroxysmal or persistent AF who underwent a first ablation between January 2021 and May 2024 were considered eligible. Patients were enrolled consecutively in the digital follow-up program and invited to install the monitoring mobile application (app) 1 week before the procedure. Exclusion criteria included redo procedures, patients who refused the digital follow-up program, those who failed to install the app, and individuals who were lost to follow-up during the study period (Figure 1). Clinical data were collected using a Web platform (Promptly - Software Solutions for Health Measures, https://promptlyhealth.com).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. AF = atrial fibrillation.

Procedure characteristics

According to the current guidelines, all patients received at least 4 weeks of oral anticoagulation before the procedure and took it for at least 3 months. Left atrial thrombi were excluded with cardiac computed tomography on the day of the procedure. Circumferential pulmonary vein isolation was achieved with radiofrequency, second-generation cryoablation, or pulsed field ablation. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Procedural success was defined as the electrical isolation of the pulmonary veins. Additional ablation lesions were performed at the operator′s discretion.

Follow-up program description

Our digital-blended 2-year follow-up program was based on the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement standards.11 It included scheduled visits, telephonic consultations, and remote monitoring through a digital health platform (Figure 2). It featured a Web platform for physicians to record baseline characteristics, medication, procedural variables, and clinical outcome measurements and to access patient-reported information and a smartphone mobile app (Promptly, version 2.5.7, Promptly Health, 2024; available on Apple App Store and Google Play Store). The app allowed patients to routinely report symptoms, vital signs (blood pressure and heart rate), and anthropometric and electrocardiographic data and to complete health-based questionnaires (Supplemental Figure 1). Patients received automated notifications prompting them to complete these questionnaires at predefined intervals. They also had the flexibility to access the app and report symptoms or submit data at their initiative. Additional program components included AF educational content and lifestyle recommendations, such as physical activity, which are accessible in the mobile app. Patients were advised to undergo an electrocardiogram (ECG) at specific time points, and these were automatically uploaded to the platform by the ambulatory clinics.

Figure 2.

Digital follow-up workflow. AFEQT = Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life; ECG = electrocardiogram; PROM = patient-reported outcome measure; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Furthermore, an ECG was performed at each in-person visit. The follow-up visits were conducted by physicians (cardiac electrophysiologists, fellows, and cardiology trainees) who reviewed the patient-submitted data before each predefined encounter: telephonic consultations at 1, 3, 6, and 18 months and in-person consultations at 12 and 24 months. Patient interaction with the app was defined as any instance of data entry, including completion of PROMs, symptom reporting, or vital sign logging.

Patient-reported outcomes

The Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life (AFEQT) questionnaire is a validated PROM specifically designed to assess the impact of AF on a patient’s QoL.12 It is beneficial after AF ablation to assess both symptom improvement and broader life impacts. The AFEQT questionnaire consists of 20 questions covering 4 main domains: symptoms, daily activities, treatment concerns, and treatment satisfaction. The score is calculated with the first 3 domains and ranges from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better QoL and lower scores higher disability. The Portuguese version of the AFEQT was previously validated.13 An improvement of at least 5 points in the AFEQT score was considered clinically significant.14 Patients received notification for completing the AFEQT questionnaire on the app at enrollment and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of follow-up.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a set of standardized tools that use item response theory to evaluate various aspects of a patient’s health condition. In this study, 4 PROMIS short-form (4 questions) questionnaires were collected: cognitive function (v2.0),15 emotional distress-anxiety (v1.0),16 physical function (v2.0),17 and emotional distress-depression (v1.0).16 Each domain uses a T-score system where scores of >50 or <50 indicate a higher or lower function relative to a relevant reference population, respectively. We used the Portuguese versions of these formularies. For scoring, we used the HealthMeasures Scoring Service Web-based app. Patients received notification for completion of PROMIS questionnaires on the app at enrollment and 6, 12, and 24 months.

At 12 months, patients were deemed nonresponders if they failed to submit the AFEQT questionnaire on at least 2 occasions. This group was compared with the responder group. The completeness rate was defined as the proportion of sent questionnaires that were completed and assessed at both individual patient levels and across each scheduled time point.

Retrospective conventional cohort

The conventional group included all patients from our retrospective registry who underwent a first ablation procedure between January 2017 and December 2020 (n = 535) before the implementation of our digital program. Clinical and procedural data were collected from hospital records. Patients from this group were followed in the outpatient clinic in our center or the referring hospital; decisions regarding the frequency of visits and clinical management were made at the referring physician’s discretion. The evaluation of outcomes for this cohort was based on the national health information platform; the last search was performed in October 2023. This centralized database tracks public health care interactions, including hospital stays, outpatient visits, diagnostic examinations, and prescribed medication.

Clinical outcomes

The end point of time to AF recurrence was defined as time to any atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence lasting ≥30 seconds. The first 8 weeks of follow-up were defined as the blanking period, and arrhythmia recurrences occurring in this period were censored. An additional end point was time to an antiarrhythmic intervention, defined as the reintroduction of antiarrhythmic medication, a new ablation procedure, or electrical cardioversion. Clinical end point evaluation was limited to 24 months of follow-up, the same duration as the digital program.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median ± interquartile range, as appropriate. Assessment of normality was performed by graphical visual analysis (histogram and QQ plot). Accordingly, the Student t test and Mann-Whitney test were used to compare numerical variables. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. The AFEQT and PROMIS scores were analyzed using a repeated-measures linear mixed-effects model with scores as outcome variables and time, 12-month arrhythmia recurrence, and time × 12-month arrhythmia recurrence as fixed effects. Random effects included intercepts, adjusting for individual baseline differences. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation with an unstructured covariance matrix and Kenward-Roger degrees of freedom approximation was used. No data imputation was performed. Mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between baseline and 12 months were estimated for the groups: recurrence and no recurrence.

We performed propensity score matching to deal with the covariate imbalance between digital and conventional groups and reduce confounding bias. A propensity score–based 1:1 match was done with the nearest-neighbor method (further details in Supplemental Data). Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests alongside Cox proportional hazards models with matching weights to adjust for the propensity score matching. Treatment effects were estimated with marginal hazard ratios (HRs) and clustered-robust standard errors (SEs), accounting for dependencies within matched pairs. In addition, we calculated the restricted mean survival time to provide an absolute measure of the average time until antiarrhythmic intervention.

Statistical tests used 2-sided P values, and the significance level was .05. Analysis was performed using R statistical software 4.4.1 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes

Between January 2021 and May 2024, 421 patients were enrolled (mean age 60.9 ± 14.5 years, 33.0% female, 71.5% with paroxysmal AF) (Table 1). Pulmonary vein isolation was performed mainly with radiofrequency (74.0%), successfully achieved in 98.1%. In 21.9%, additional ablation lesions were performed. Procedure complications occurred in 10 patients (2.4%). As of May 2024, the median follow-up duration was 546 days; 251 patients had completed at least 1 year of follow-up, with a 12-month arrhythmia recurrence rate of 18.1%. A total of 1620 appointments were carried out, 75.4% of which were remote consultations. The median number of remote and in-person appointments per patient was 3 and 1, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Total (n = 421) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 60.9 (53.0, 67.5) |

| Female, % | 139 (33.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.1 (24.7, 29.4) |

| Hypertension, % | 196 (47.6) |

| History of smoking, % | |

| None | 257 (72.8) |

| Current | 31 (8.8) |

| Past | 65 (18.4) |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 191 (46.6) |

| Sleep apnea, % | 32 (7.8) |

| Previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, % | 19 (4.6) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, % | 41 (10.0) |

| Coronary artery disease, % | 18 (4.4) |

| Heart failure, % | 49 (11.9) |

| Cardiac implantable device, % | 19 (4.6) |

| Thyroid dysfunction, % | 42 (10.6) |

| History of anemia, % | 26 (7.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease, % | 27 (7.5) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1.0 (0, 2.0) |

| Systolic dysfunction, % | 49 (12.3) |

| Moderate or severe valvular disease, % | 47 (11.7) |

| Left atrial volume, mL/m2 | 37.0 (30.0, 45.0) |

| Continued use of antiarrhythmic drugs, % | |

| III | 166 (41.2) |

| Ic | 78 (19.4) |

| No | 159 (39.5) |

| Oral anticoagulation, % | |

| No | 12 (2.9) |

| NOAC | 393 (95.2) |

| VKA | 8 (1.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation type, % | |

| Paroxysmal | 298 (71.5) |

| Persistent | 119 (28.5) |

| Time since diagnosis, y | 2.0 (1.0, 5.0) |

| Previous electrical cardioversion, % | 161 (44.0) |

| Ablation energy, % | |

| Radiofrequency | 307 (72.9) |

| Cryoenergy | 78 (18.5) |

| Pulsed field ablation | 36 (8.6) |

Values are presented as n (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR), where applicable.

CHA2DS2-VASc = congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism, vascular disease, age 65–74 years, sex category; IQR = interquartile range; NOAC = non–vitamin K oral anticoagulant; SD = standard deviation; VKA = vitamin K antagonist.

App utilization and health-related questionnaires

The app was used at least monthly by 64% of patients (any PROM or clinical data entry). At least 1 remote ECG was uploaded for 24.1%. We found a median individual-level AFEQT completeness rate of 80% (completed or sent), with time point–specific rates ranging from 54% to 71% (Figure 3A). A total of 1213 AFEQT questionnaires were analyzed, and 82.5% of the population had ≥2 fulfilled questionnaires, meeting the criteria for responders. When comparing nonresponders with responders (Supplemental Table 1), we observed that nonresponders were older (63.1 vs 60.0 years, P = .007) and more often had persistent AF (36.4% vs 20.3%, P = .022). Responders and nonresponders had no significant statistical differences regarding clinical outcomes (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 3.

Trends in quality-of-life scores and questionnaire completeness rates over 12 months after ablation. A: Left panel reveals AFEQT mean scores with 95% confidence intervals over the first 12 months after ablation. B: Right panel displays mean PROMIS T-scores with error bars for the 4 studied domains over the same period. Warm colors indicate domains in which lower scores are better, and cool colors indicate domains in which higher scores are better. Round points represent scheduled time points of PROM assessment. Completeness rates for each time point (questionnaires completed or sent) are displayed below the plots. AFEQT = Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life; PROM = patient-reported outcome measure; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

The mean AFEQT score (lower score indicates a higher disability) at baseline was 57.2 points (standard deviation 22.7), and there was a significant increase at 12 months, with +19.5 points (95% CI, 15.3–23.7 points, P < .001), indicating improved QoL. The mean adjusted difference was +13.2 points (95% CI, 10.5–16.0 points, P < .001) (Figure 3A), and 70.8% of patients had a clinically meaningful improvement in the AFEQT score. Regarding PROMIS, we analyzed 1920 questionnaires and found a median individual-level completeness rate of 50%, with time point–specific rates ranging from 30% to 63% (Figure 3B). We observed a significant increase in physical function (+3.9 points; 95% CI 2.5–5.4 points; P < .001) and cognitive function (+1.9 points; 95% CI 0.5–3.2 points; P = .006) and a significant decrease in depression score (−2.6 points; 95% CI −3.9 to −1.2 points; P < .001) and anxiety score (−4.2 points; 95% CI −5.7 to −2.7 points; P < .001) (Figure 3B).

For both AFEQT and PROMIS anxiety, depression, and physical function questionnaires, the magnitude of improvements in QoL was significant in patients without AF recurrence (Table 2). There was a statistically significant interaction between the variables, time and 12-month arrhythmia recurrence status, for AFEQT, PROMIS depression and physical function, indicating that this status influenced the rates of change in the scores (P < .05 for interactions). In the group of patients with 12-month arrhythmia recurrence, there were no significant mean adjusted differences between baseline and 12 months for the AFEQT score, PROMIS anxiety, depression, and cognitive function. However, a significant decrease in physical function was observed.

Table 2.

Estimated marginal means and mean adjusted differences of AFEQT and PROMIS scores between baseline and 12 months in the groups, without or with 12-month recurrence

| Quality-of-life questionnaires | Baseline | 12 mo | Mean adjusted difference (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean overall AFEQT score (SE) | ||||

| No recurrence | 70.2 (1.4) | 84.6 (1.7)∗ | +14.4 (10.9–17.9) | <.001 |

| Recurrence | 67.1 (3.1) | 67.8 (3.5)∗ | +0.6 (−6.9 to 8.1) | .871 |

| Anxiety PROMIS, mean t score (SE) | ||||

| No recurrence | 54.8 (1.0) | 52.1 (0.7)∗ | −2.8 (−0.7 to −4.8) | .008 |

| Recurrence | 55.2 (2.1) | 56.3 (1.6)∗ | +1.1 (−3.4 to 5.6) | .631 |

| Depression PROMIS, mean t score (SE) | ||||

| No recurrence | 51.6 (0.9) | 49.4 (0.7)∗ | −2.2 (−0.4 to −3.9) | .018 |

| Recurrence | 50.2 (1.9) | 53.7 (1.5)∗ | +3.5 (−0.4 to 7.4) | .082 |

| Cognitive function PROMIS, mean t score (SE) | ||||

| No recurrence | 49.8 (0.9) | 51.7 (0.7)∗ | +1.8 (−0.1 to 3.7) | .058 |

| Recurrence | 49.6 (2.0) | 47.8 (1.5)∗ | −1.9 (−6.0 to 2.3) | .377 |

| Physical function PROMIS, mean t score (SE) | ||||

| No recurrence | 45.3 (0.8)∗ | 49.7 (0.6) | +4.4 (2.8–6.0) | <.001 |

| Recurrence | 52.2 (1.8)∗ | 47.5 (1.4) | −4.6 (−8.1 to −1.1) | .010 |

AFEQT = Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life; CI = confidence interval; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SE = standard error.

Statistically significant between-group differences at each time point.

Comparison with retrospective cohort

After propensity score matching, we observed similar baseline characteristics between groups, with 363 patients each (Supplemental Table 3). No significant differences were observed between groups regarding major adverse cardiovascular events or emergency department visits at 12 months (Supplemental Table 4). Kaplan-Meier estimates were conducted over the 24-month follow-up period for the end points of AT or AF recurrence and antiarrhythmic intervention (Figure 4). At 1 year, freedom from AT or AF recurrence was 85.4% in the conventional group and 82.3% in the digital group. In a weighted Cox proportional hazards model, digital follow-up was associated with significantly less freedom from AT or AF recurrence than conventional follow-up (marginal HR 1.45; cluster-robust SE of 0.16; P = .019) (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the freedom from an antiarrhythmic intervention (reintroduction of antiarrhythmic medication, cardioversion, or new ablation) was significantly lower in the digital group (marginal HR 1.65; cluster-robust SE of 0.23; P = .022), as depicted in Figure 4B. The restricted mean time to antiarrhythmic intervention was significantly shorter in the digital group (−167 days; 95% CI −290 to −43; P = .008).

Figure 4.

Time-to-event analysis for arrhythmia recurrence and antiarrhythmic intervention by follow-up strategy. Kaplan-Meier curves revealing freedom from AT recurrence (A) and from antiarrhythmic intervention—defined as reinitiation of antiarrhythmic medication, cardioversion, or repeat ablation (B) over a follow-up period of 24 months. AF = atrial fibrillation; AT = atrial tachyarrhythmia.

Discussion

This study describes a real-world implementation of a digital-blended structured follow-up for patients after AF ablation. We successfully included >400 patients, revealing high inclusion rates (86.2%) and low rates of patients lost to follow-up (3.9%). The systematic collection of electronic PROM was feasible and showed high completeness rates, enabling the observation of improvements across all domains. Telemedicine-based digital follow-up was associated with earlier recurrence detection and antiarrhythmic intervention (Central Illustration).

PROMs

Current guidelines emphasize the importance of including QoL as a key outcome measure in clinical practice and research to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments such as ablation. In this observational study, the AFEQT questionnaire, an AF-specific health-related QoL measure, achieved 80% completeness rates, demonstrating improved adherence compared with previous real-world experiences of systematic electronic PROM collection. The completeness rates for AFEQT were closer to those found in clinical trials: 91% in CABANA (Catheter Ablation versus Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation)18 and 85% in STAR AF II (Substrate and Trigger Ablation for Reduction of Atrial Fibrillation–Part II).19 In clinical practice, PROM collection is usually clinic based, as described in the Utah mEVAL (My Evaluation) AF program,20 which reported a 90% completeness rate for AF symptom severity score (AF-specific QoL PROM). Previous experiences of real-world systematic electronic PROM collection relied on e-mail notifications and online surveys, such as the Cleveland Clinic experience,21 which reported approximately 50% completeness rate for the same PROM. In our experience, mobile app–based questionnaires are feasible and probably the most convenient method to assess QoL in this group of patients. Older patients, a segment of the AF population that usually has poorer health-related QoL,22 were more frequently nonresponders. Future studies should consider digital literacy in older adults, as many older patients are less comfortable with technology.

Beyond health-related QoL questionnaires, the International Consortium of Healthcare Outcome Measures for AF also considers that validated PROMIS can be used to assess other QoL domains.11 In this study, we evaluated 4 PROMIS questionnaires: physical function, cognitive function, depression, and anxiety, with lower completeness rates than the AFEQT questionnaire. A possible explanation might be that PROMIS is not disease specific, but the AFEQT addresses AF-specific symptoms, possibly making it more engaging for patients because it reflects their personal experiences with AF. Nevertheless, significant improvements in the 4 domains were observed 12 months postablation. Regarding the AFEQT score, we noted a significant increase of nearly 20 points by the end of the first year, with >70% of patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement. This clear improvement in patients’ QoL after ablation is aligned with data from key randomized controlled trials, such as CABANA,18 and the recent sham-control AF ablation trial, SHAM-PVI.5 Several studies have consistently revealed that AF recurrences and the burden of AF negatively affect QoL.23 In our study, a recurrence during the first year significantly affected the trajectory and rates of change in the AFEQT score, illustrating the sensitivity to arrhythmia recurrence. The impact of arrhythmia recurrence on PROMIS domains was more nuanced. Although the interaction between time and recurrence was significant for the domains of depression and physical function, notable between-group differences in scores at 12 months were also observed for anxiety and cognitive function domains. These findings suggest that arrhythmia recurrence may influence specific aspects of QoL to varying degrees. Determining the impact of recurrences in a patient’s QoL may contribute to personalized treatment decisions regarding the continuation or cessation of rhythm control.

Clinical impact of remote AF management

Several clinical care pathways have been proposed with mixed results in clinical outcomes but with consistent improvements in adherence to guideline-directed recommendations.9,10,24 The TeleCheck-AF approach, developed during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, used app-based heart rate and rhythm monitoring for teleconsultations, facilitating the management of AF without in-person visits.25 Similar to our study, the TeleCheck approach also revealed no differences in emergency department visits despite an 80% reduction in face-to-face consultations.26 Adherence might be a benefit driver, as in the mAFA-II (mobile atrial fibrillation application) trial,27 where the authors found a reduction in the composite outcome of stroke, death, and hospitalization risk, with adherence to the mobile health intervention reaching 92%. However, the much smaller emPOWERD-AF trial enrolled 80 patients with AF to study the impact of implementing a physician-oriented Web platform and patient-oriented smartphone app.28 At 6 months, the app adherence was 53.9%, and there was a significant increase in QoL, without differences in AF-related hospitalizations. However, comparisons between studies are difficult because there is considerable heterogeneity in mobile health interventions and adherence definitions. In our study, despite modest ambulatory ECG reporting, 64% of patients interacted with the app at least once monthly, demonstrating sustained engagement. At the end of the 2-year follow-up period, patients in the digital group followed primarily through telemedicine experienced a significantly shorter time to arrhythmia recurrence and to antiarrhythmic intervention compared with those in the conventional care group. These findings suggest that the digital pathway enabled earlier detection and more timely clinical responses to recurrence events. AF can perpetuate its progression through structural and electrophysiological remodeling,29,30 making early rhythm control essential to reduce cardiovascular events, as found in the EAST-AFNET 4 (Early Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation for Stroke Prevention Trial) study.3 Delays between AF diagnosis and ablation have been associated with worsened long-term outcomes.31,32 Several studies also support early rhythm control following AF recurrence after ablation. For instance, Baman and colleagues33 observed that cardioversion within 30 days of a persistent atrial arrhythmia was an independent predictor of sinus rhythm maintenance. Additionally, a study from the China Atrial Fibrillation Registry found that electrical cardioversion during the blanking period after ablation was associated with significantly lower rates of 1-year AF recurrence, further highlighting the benefits of early rhythm control.34 Structured digital follow-up may offer a feasible and scalable approach to achieving earlier rhythm control after AF ablation. However, further studies are needed to confirm these findings and determine whether this approach improves long-term clinical outcomes.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the absence of randomization to adequately compare clinical outcomes between groups. Bias was reduced using propensity score analysis to adjust for differences between populations, but there is the potential for residual confounding, namely temporal biases. For example, certain procedural advances, such as the introduction of pulsed field ablation during the digital follow-up period, were not present in the conventional care group. Notably, selection bias in group allocation was minimized, as the digital-blended approach replaced conventional care in our center starting in January 2021. Collecting patient-reported outcomes may introduce selection bias, as more satisfied or health-conscious patients may have been more likely to complete the questionnaires. In addition, older patients, who often experience poorer health-related QoL, were more frequently nonresponders. We also observed lower PROMIS completeness rates at baseline, which may have limited our ability to capture changes in those specific domains of well-being early in the follow-up period. The single-center design, in addition to the underrepresentation of the female sex and the predominantly white cohort, limits the generalizability of the results. Moreover, the absence of QoL assessment in the conventional group precluded direct comparisons between groups. No continuous rhythm monitoring was implemented in this study, probably contributing to the underestimation of the arrhythmia recurrences. Finally, longer follow-up is needed to assess the sustained impact of the digital program beyond the 2-year period.

Conclusion

Implementing digital tools for assessing PROMs in real-world clinical practice is feasible, with high completeness rates for the AFEQT questionnaire comparable to those found in randomized clinical trials. AFEQT and PROMIS scores improved significantly after ablation and were adversely affected by arrhythmia recurrences. A structured digital-blended follow-up, relying mainly on telemedicine, enabled earlier detection of arrhythmia recurrence and more timely antiarrhythmic interventions than conventional care. This study supports the inclusion of digital tools in the value-based and integrated health care framework in the follow-up of patients after AF ablation.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work has been partly funded by MICIN project PID2022-140556OB-I00, Spain, and Reference Group BSIoS T39_23R (Aragon Government). R Almeida is funded by https://doi:10.54499/CEECINST/00056/2021/CP2804/CT0004.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Authorship

All authors attest they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Patient Consent

Written informed consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective design.

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted at Unidade Local de Saúde Gaia e Espinho, Portugal, in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Unidade Local de Saúde Gaia e Espinho’s ethical committee approved the study protocol. The research reported in this paper adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hroo.2025.04.004.

Appendix. Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Van Gelder I.C., Rienstra M., Bunting K.V., et al. ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3314–3414. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buja A., Rebba V., Montecchio L., et al. The cost of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Value Health. 2024;27:527–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2023.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchhof P., Camm A.J., Goette A., et al. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1305–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade J.G., Wells G.A., Deyell M.W., et al. Cryoablation or drug therapy for initial treatment of atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:305–315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dulai R., Sulke N., Freemantle N., et al. Pulmonary vein isolation vs sham intervention in symptomatic atrial fibrillation: the SHAM-PVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;332:1165–1173. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.17921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joglar J.A., Chung M.K., Armbruster A.L., et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:e1–e156. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lan R.H., Perez-Guerrero E., Saeed M., Perez M.V. Rising trend in use of patient-reported outcomes in atrial fibrillation clinical trials. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21:1524–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinberg B.A. Moving toward PRO-guided care of AF. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2023;9:1945–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2023.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendriks J.M., de Wit R., Crijns H.J., et al. Nurse-led care vs. usual care for patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized trial of integrated chronic care vs. routine clinical care in ambulatory patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2692–2699. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijtvliet E.P.J.P., Tieleman R.G., van Gelder I.C., et al. Nurse-led vs. usual-care for atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2019;41:634–641. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seligman W.H., Das-Gupta Z., Jobi-Odeneye A.O., et al. Development of an international standard set of outcome measures for patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) atrial fibrillation working group. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1132–1140. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spertus J., Dorian P., Bubien R., et al. Development and validation of the Atrial Fibrillation Effect on QualiTy-of-Life (AFEQT) Questionnaire in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:15–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.958033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darmits B. University of Coimbra; Coimbra: 2020. Efeito da fibrilhação auricular na qualidade de vida [master’s thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes D.N., Piccini J.P., Allen L.A., et al. Defining clinically important difference in the atrial fibrillation effect on quality-of-life score. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai J.-S., Wagner L.I., Jacobsen P.B., Cella D. Self-reported cognitive concerns and abilities: two sides of one coin? Psychooncol. 2014;23:1133–1141. doi: 10.1002/pon.3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilkonis P.A., Choi S.W., Reise S.P., et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose M., Bjorner J.B., Gandek B., Bruce B., Fries J.F., Ware J.E., Jr. The PROMIS Physical Function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:516–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mark D.B., Anstrom K.J., Sheng S., et al. Effect of catheter ablation vs medical therapy on quality of life among patients with atrial fibrillation: The CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:1275–1285. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantovan R., Macle L., De Martino G., et al. Relationship of quality of life with procedural success of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation and postablation AF burden: substudy of the STAR AF randomized trial. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1211–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg B.A., Turner J., Lyons A., et al. Systematic collection of patient-reported outcomes in atrial fibrillation: feasibility and initial results of the Utah mEVAL AF programme. Europace. 2020;22:368–374. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussein A.A., Lindsay B., Madden R., et al. New model of automated patient-reported outcomes applied in atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L., Gallagher R., Neubeck L. Health-related quality of life in atrial fibrillation patients over 65 years: a review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:987–1002. doi: 10.1177/2047487314538855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuel M., Khairy P., Champagne J., et al. Association of atrial fibrillation burden with health-related quality of life after atrial fibrillation ablation: substudy of the cryoballoon vs contact-force atrial fibrillation ablation (CIRCA-DOSE) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1324–1328. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart S., Ball J., Horowitz J.D., et al. Standard versus atrial fibrillation-specific management strategy (SAFETY) to reduce recurrent admission and prolong survival: pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:775–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61992-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pluymaekers N., Hermans A.N.L., van der Velden R.M.J., et al. Implementation of an on-demand app-based heart rate and rhythm monitoring infrastructure for the management of atrial fibrillation through teleconsultation: TeleCheck-AF. Europace. 2021;23:345–352. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gawalko M., Betz K., Hendriks V., et al. Changes in healthcare utilisation during implementation of remote atrial fibrillation management: TeleCheck-AF project. Neth Heart J. 2024;32:130–139. doi: 10.1007/s12471-023-01836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y., Guo J., Shi X., et al. Mobile health technology-supported atrial fibrillation screening and integrated care: a report from the mAFA-II trial Long-term Extension Cohort. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;82:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazaridis C., Bakogiannis C., Mouselimis D., et al. The usability and effect of an mHealth disease management platform on the quality of life of patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation-the emPOWERD-AF study. Health Inform J. 2022;28 doi: 10.1177/14604582221139053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wijffels M.C.E.F., Kirchhof C.J.H.J., Dorland R., Allessie M.A. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1995;92:1954–1968. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brundel B.J.J.M., Henning R.H., Kampinga H.H., Van Gelder I.C., Crijns H.J.G.M. Molecular mechanisms of remodeling in human atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:315–324. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bunch T.J., May H.T., Bair T.L., et al. Increasing time between first diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and catheter ablation adversely affects long-term outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segan L., Kistler P.M., Chieng D., et al. Prognostic impact of diagnosis-to-ablation time on outcomes following catheter ablation in persistent atrial fibrillation and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Heart Rhythm. published online ahead of print September 24, 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baman T.S., Gupta S.K., Billakanty S.R., et al. Time to cardioversion of recurrent atrial arrhythmias after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation and long-term clinical outcome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:1321–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong Z., Du X., Hou X.X., He L., Dong J.Z., Ma C.S. Effect of electrical cardioversion on 1-year outcomes in patients with early recurrence after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol. 2021;44:1128–1138. doi: 10.1002/clc.23663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.