Abstract

Objective

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder affecting up to 10% of women of reproductive age, with significant physical and psychological consequences. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of adult separation anxiety in women with PCOS. The secondary objective was to investigate the relationship between ASA (Adult Separation Anxiety) symptoms and the levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and intolerance of uncertainty.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 114 women with PCOS. Participants were administered the Sociodemographic Data Form, Adult Separation Anxiety Scale (ASA-27), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS-12). Data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 with Mann-Whitney U, chi-square tests, and Spearman correlations (significance set at p < 0.05).

Results

The findings revealed that 28.9% of women with PCOS exhibited separation anxiety symptoms above the cut-off score of 25. These symptoms were significantly correlated with elevated levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and intolerance of uncertainty. Moreover, individuals with separation anxiety above the cut-off score demonstrated notably higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and intolerance of uncertainty compared to those below the cut-off score. They also exhibited greater rates of clinical symptoms such as weight gain, acne, and infertility, as well as higher levels of testosterone, DHEAS, and LH/FSH ratio.

Conclusion

Adult separation anxiety may be relatively common among women with PCOS and may be linked to both psychological distress and hormonal/metabolic characteristics.These findings suggest that considering ASA during psychological assessments of PCOS could be valuable and warrant further investigation through longitudinal research.

Keywords: Polycystic ovary syndrome, Adult separation anxiety, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Uncertainty intolerance

Introduction

The endocrine disorder known as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a prevalent illness that affects women who are of reproductive age. It is brought on by a confluence of variables, including those induced by genetics, the environment, and metabolism. PCOS is associated with a variety of symptoms including hirsutism, infertility and metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism and cardiovascular disease [1]. It is the most prevalent endocrine condition in women of reproductive age and is a significant contributor to female infertility, affecting around 6 to 10% of women [2].

PCOS is a syndrome that has significant effects not only on physical health but also on psychological health. Several psychological disorders have been reported in women with PCOS [3]. Psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, eating disorders, mood disorders, impaired cognitive functions have been reported [4]. Psychological problems, especially anxiety and depression, frequently observed in women with PCOS can significantly affect their quality of life [5]. Effective management of depression symptoms and anxiety is crucial for women diagnosed with PCOS. International guidelines recommend screening for anxiety and depressive symptoms at diagnosis in all adolescents and women with PCOS [6, 7]. Women with PCOS often experience barriers to managing the condition due to symptoms of anxiety and depression [8]. Beyond its biological presentation, PCOS is ingrained in a sociocultural matrix where femininity, fertility, and appearance are socially scrutinized. Particularly for women negotiating unstable social or intimate relationships, these outside pressures can aggravate psychological conditions, including separation anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty [9]. Moreover, delays in diagnosis of PCOS can lead to missed opportunities for symptom management, counseling on fertility, and early engagement in preventive strategies for metabolic complications, highlighting the importance of addressing psychological aspects early [10].

Anxiety is a common psychological disorder influenced by a variety of factors, including intolerance of uncertainty. Intolerance of uncertainty refers to an individual’s inability to cope with ambiguous or unpredictable situations [11]. Research has shown that it contributes to increased psychological distress, anxiety, and depression [11, 12]. In this respect, intolerance of uncertainty has been recognized as a transdiagnostic factor in the development and maintenance of various anxiety symptoms [13]. Adult separation anxiety is one such anxiety disorder reported in the DSM-5 as occurring in adulthood. Symptoms typically involve persistent worries about actual or potential separations, such as those from parents or partners, or major life transitions [14]. Unlike other anxiety disorders, adult separation anxiety (ASA) has a strong foundation in early developmental experiences and attachment theory. Interpersonal insecurities and abandonment fears that characterize ASA may be mirrored or even exacerbated by the ongoing uncertainty and stigma surrounding PCOS, which spans issues such as fertility, body image, and gender expectations. Thus, exploring ASA in the context of PCOS from both sociocultural and psychological perspectives is warranted [15].

Adult separation anxiety disorder is reported to affect 6–7% of adults at some stage in their lifetimes in the literature [16, 17]. Since it has been defined as a new diagnostic category in recent years, its clinical features are not questioned sufficiently and therefore these symptoms and diagnosis are often missed. The clinical presentation may be complicated by other comorbid psychological symptoms. Comorbid psychological symptoms have been reported in adult separation anxiety disorder. Other psychological symptoms, especially anxiety disorders and depressive disorders, may be observed frequently [18]. Specifically, it is uncertain to what degree the mechanisms that contribute to other forms of anxiety are also associated with the symptoms of adult separation anxiety. There have been relatively few research on the association between characteristics like intolerance of uncertainty and adult separation anxiety. In the small number of research exploring adult separation anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty, it has been shown that the severity of separation anxiety may be connected to the level of uncertainty intolerance [19, 20].

There are no studies in the literature investigating separation anxiety symptoms in patients with PCOS. Our research aimed to investigate the prevalence of adult separation anxiety in women with PCOS. The secondary objective was to investigate the relationship between ASA symptoms and the levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and intolerance of uncertainty.

Materials and methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between July 2022 and July 2023. This study was conducted at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic of Afyonkarahisar State Hospital. Participants were recruited by a gynecologist from among patients who had been diagnosed with PCOS based on the Rotterdam criteria. After receiving detailed information about the study, eligible individuals who provided written informed consent were asked to complete a set of self-report questionnaires. These questionnaires were administered in a quiet room within the clinic, and participants completed them individually. A total of 125 women meeting the inclusion criteria were initially invited to participate, and data collection was completed with 114 participants. All participants completed the questionnaires in full, and there was no missing data in the final analysis. Inclusion criteria were: women aged 18–40 years, diagnosed with PCOS based on the Rotterdam criteria, and capable of completing self-administered questionnaires. Exclusion criteria included illiteracy, current or past diagnoses of severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., psychosis, bipolar disorder), or neurological or metabolic conditions likely to impact cognitive functioning.

Participants were administered the Sociodemographic Data Form, Adult Separation Anxiety Scale (ASA-27), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS-12). The study was approved by Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee on June 3, 2022 with the decision numbered 2022/325. The principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed in the study. All participants gave written informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Sociodemographic data form

This form, developed by the researchers, included questions about participant gender, age, educational status, marital status, smoking, duration of illness, age at first menstruation, height and weight.

Adult separation anxiety questionnaire (ASA-27)

The Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire was developed by Manicavasagar et al. in 2003. The 27-item Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire is a self-report measure that looks into the signs and severity of separation anxiety in adults [21]. Diriöz et al. did a validity and reliability study in Turkey in 2012 [22]. The Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire (ASA-27) includes 27 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). The scale evaluates emotional and behavioral symptoms related to adult separation anxiety. The cut-off score for the scale was set as 25.

Intolerance of uncertainty scale (IUS-12)

Carleton et al. developed the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS-12) in 2007 based on the earlier work of Freeston et al., who created the original 27-item Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale [23]. The scale comprises 12 items and 2 subscales, and it is administered through self-report. The first 7 questions consist of the ‘prospective anxiety’ subscale related to cognitions about uncertain future events; the last 5 questions consist of the ‘inhibitory anxiety’ subscale related to anxiety symptoms and behavioral symptoms related to uncertainty. Using a Likert scale with five points, the scale ranges from one, which indicates “not at all suitable for me,” to five, which indicates “completely suitable for me”. The scale does not have a defined cut-off score, and the total score that can be obtained from the scale ranges from 12 to 60. Rising scores suggest a high level of intolerance to uncertainty. Sarıçam et al. conducted the Turkish validity and reliability investigation of the IUS-12 in 2014 [24].

Depression, anxiety and stress scale-short form (DASS-21)

DASS-21 is a scale consisting of 21 questions selected from the DASS-42 scale by Lovibond et al. [25]. This scale has three subscales of 7 items measuring Depression, Anxiety and Stress. Participants are asked to score their responses to each topic using a Likert-type scale that ranges from 0 to 3. A higher score indicates the severity of distress. For the purpose of determining the validity and reliability of the 21-item short version of the scale, the Turkish research was carried out by Sarıçam (2018) and the internal consistency coefficient of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85 for the depression subscale, 0.80 for the anxiety subscale, and 0.77 for the tension subscale [26].

Statistics

SPSS 22.0 was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The distribution of age and scale scores was evaluated by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare age and scale scores that did not conform to normal distribution between the two groups. Chi-square test was used for categorical variables in comparisons between two groups. Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the correlations between continuous variables. Figures and graphical visualizations were created using JASP software (version 0.18.3; University of Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Results

The 114 patients diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are summarized in Table 1, which includes their demographic, clinical, and psychological characteristics. The participants’ mean age was 29.52 ± 4.98 years, and their mean body mass index (BMI) was 30.10 ± 4.88 kg/m². Gravidity, parity, and abortion all had median values of 0. 14.0% of patients were classified as normal weight, 39.5% as overweight, and 46.5% as obese, as per the BMI categories. The majority of participants were married (59.6%), not employed (78.9%), and smoked (42.1%). The median disease duration was 3.5 years, and 23.7% of the cohort reported a positive family history of PCOS. Infertility (40.4%), acne (40.4%), weight gain (78.1%), and menstrual irregularity (81.6%) were the most prevalent clinical symptoms. The average age at menarche was 14.29 ± 1.41 years. The mean total testosterone level was elevated (116.83 ± 14.26 ng/dL), the mean DHEAS level was 176.19 µg/dL, and the LH/FSH ratio was 1.96, as indicated by laboratory findings. The psychological assessment scores indicated that there were substantial levels of future anxiety (25.16 ± 6.42), inhibitory anxiety (17.66 ± 4.40), depression (8.69 ± 3.02), anxiety (10.04 ± 3.82), and stress (9.21 ± 2.73). It is important to note that 33 (28.9%) of the participants exhibited ASA-positivity, which is a sign of adult separation anxiety. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic and psychological characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) patients

| Variable (n = 114) | Mean ± SD, Median (Min– Max) n(%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic parameters | ||

| Age(year) | 29.52 ± 4.98 | |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 30.10 ± 4.88 | |

| Gravidity | 0.00 (0.00–2.00) | |

| Parity | 0.00 (0.00–2.00) | |

| Abortion | 0.00 (0.00–2.00) | |

| BMI category | Normal | 16 (14.0%) |

| Overweight | 45 (39.5%) | |

| Obese | 53 (46.5%) | |

| Marital status | Married | 68 (59.6%) |

| Single | 26 (22.8%) | |

| Divorced | 20 (17.5%) | |

| Working status | Working | 24 (21.1%) |

| Not working | 90 (78.9%) | |

| Smoking | 48 (42.1%) | |

| Positive family history for PCOS | 27 (23.7%) | |

| Duration of illness(year) | 3.50 (0.00–13.00) | |

| Age at first mens | 14.29 ± 1.41 | |

| Psychiatric illness in the family | 43 (37.7%) | |

| Menstrual irregularity | 93 (81.6%) | |

| Hirsutism | 40 (35.1%) | |

| Weight gain | 89 (78.1%) | |

| Acne | 46 (40.4%) | |

| İnfertility | 46 (40.4%) | |

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| Total Testosterone (ng/dL) | 116.83 ± 14.26 | |

| DHEAS (µg/dL) | 176.19 (101.00–247.00) | |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 101.71 ± 24.13 | |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 14.17 ± 3.78 | |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 10.68 ± 2.21 | |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 5.30 ± 1.27 | |

| LH/FSH Ratio | 1.96 (1.14–3.99) | |

| Psychiatric scale scores | ||

| Anxiety about the future | 25.16 ± 6.42 | |

| Inhibitory anxiety | 17.66 ± 4.40 | |

| IUS Total | 46.00 (17.00–60.00) | |

| Depression | 8.69 ± 3.02 | |

| Anxiety | 10.04 ± 3.82 | |

| Stress | 9.21 ± 2.73 | |

| ASA Score | 18.00 (4.00–72.00) | |

| ASA Positivitiy | 33 (28.9%) | |

BMI: body mass index, ASA: adult separation anxiety, PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome, IUS: intolerance of uncertainty scale. DHEAS: dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, LH: luteinizing hormone, FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone

Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical parameters of the ASA-positive and ASA-negative groups. Patients who tested positive for ASA were more likely to smoke (57.6% vs. 35.8%, p = 0.033) and were substantially less likely to work (3.0% vs. 28.4%, p = 0.003). The ASA-positive group had a higher prevalence of positive family history of PCOS (45.5% vs. 14.8%, p = 0.001). In ASA-positive patients, clinical symptoms such as weight gain (90.9% vs. 72.8%, p = 0.034), acne (57.6% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.017), and infertility (63.6% vs. 30.9%, p = 0.001) were significantly more prevalent. The laboratory results indicated that the total testosterone (123.27 ± 15.96 vs. 114.21 ± 12.71 ng/dL, p = 0.005), DHEAS (210.78 vs. 167.91 µg/dL, p = 0.009), estradiol (118.52 ± 17.40 vs. 94.86 ± 23.17 pg/mL, p = 0.001), and LH (11.70 ± 1.88 vs. 10.26 ± 2.21 mIU/mL, p = 0.001) values, as well as the LH/FSH ratio (2.49 vs. 1.85, p = 0.001), were elevated. Other variables did not exhibit any significant differences (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between ASA negative and ASA positive groups

| Variable | ASA Negative (n = 81) | ASA Positive (n = 33) |

p

value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(year) | 29.63 ± 4.93 | 29.27 ± 5.19 | 0.731 α | |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 29.91 ± 4.45 | 30.57 ± 5.86 | 0.519 α | |

| Gravidity | 1.00(0.00–2.00) | 0.00(0.00–2.00) | 0.101 β | |

| Parity | 1.00(0.00–2.00) | 0.00(0.00–2.00) | 0.261 β | |

| Abortion | 0.00(0.00–2.00) | 0.00(0.00–1.00) | 0.449 β | |

| BMI category | Normal | 11 (13.6%) | 5 (15.2%) | 0.907 γ |

| Overweight | 33 (40.7%) | 12 (36.4%) | ||

| Obese | 37 (45.7%) | 16 (48.5%) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 49 (60.5%) | 19 (57.6%) | 0.376 γ |

| Single | 16 (19.8%) | 10 (30.3%) | ||

| Divorced | 16 (19.8%) | 4 (12.1%) | ||

| Working status | Working | 23 (28.4%) | 1 (3.0%) | 0.003 γ |

| Not working | 58 (71.6%) | 32 (97.0%) | ||

| Smoking | 29 (35.8%) | 19 (57.6%) | 0.033 γ | |

| Positive family history for PCOS | 12 (14.8%) | 15 (45.5%) | 0.001 γ | |

| Duration of illness(year) | 4.00(0.00–13.00) | 3.00(0.00–12.00) | 0.883 β | |

| Menstrual irregularity | 63 (77.8%) | 30 (90.9%) | 0.101 γ | |

| Hirsutism | 31 (38.3%) | 9 (27.3%) | 0.264 γ | |

| Weight gain | 59 (72.8%) | 30 (90.9%) | 0.034 γ | |

| Acne | 27 (33.3%) | 19 (57.6%) | 0.017 γ | |

| İnfertility | 25 (30.9%) | 21 (63.6%) | 0.001 γ | |

| Age at first mens | 14.46 ± 1.40 | 13.91 ± 1.40 | 0.060 α | |

| Total Testosterone (ng/dL) | 114.21 ± 12.71 | 123.27 ± 15.96 | 0.005 α | |

| DHEAS (µg/dL) | 167.91(114.49–247.00) | 210.78(101.00–241.25) | 0.009 β | |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 94.86 ± 23.17 | 118.52 ± 17.40 | 0.001 α | |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 14.45 ± 3.25 | 13.46 ± 4.84 | 0.286 α | |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 10.26 ± 2.21 | 11.70 ± 1.88 | 0.001 α | |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 5.49 ± 1.29 | 4.83 ± 1.09 | 0.012 α | |

| LH/FSH Ratio | 1.85(1.14-4.00) | 2.49(1.71–3.38) | 0.001 β | |

α Independent t-test (mean ± SD), β Mann-Whitney U test [median (min-max)], γ chi-square test n (%). BMI: body mass index, ASA: adult separation anxiety, PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome, DHEAS: dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, LH: luteinizing hormone, FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone

The two groups also exhibited substantial differences in psychiatric and psychological characteristics (Table 3). ASA-positive patients exhibited elevated inhibitory anxiety (20.70 ± 1.42 vs. 16.43 ± 4.61, p = 0.001), IUS total (48.00 vs. 42.00, p = 0.004), depression (11.24 ± 2.12 vs. 7.65 ± 2.71, p = 0.001), anxiety (14.33 ± 1.29 vs. 8.30 ± 3.05, p = 0.001), stress (11.91 ± 1.33 vs. 8.12 ± 2.38, p = 0.001), and ASA score (40.00 vs. 13.00, p = 0.001). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of other psychiatric parameters (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Psychiatric and psychological profile comparison between ASA negative and ASA positive groups

| Variable | ASA Negative (n = 81) | ASA Positive (n = 33) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric illness in the family | 31 (38.3%) | 12 (36.4%) | 0.849 γ |

| Anxiety about the future | 24.59 ± 6.72 | 26.58 ± 5.48 | 0.136 α |

| Inhibitory anxiety | 16.43 ± 4.61 | 20.70 ± 1.42 | 0.001 α |

| IUS Total | 42.00 (17.00–60.00) | 48.00 (37.00–54.00) | 0.004 β |

| Depression | 7.65 ± 2.71 | 11.24 ± 2.12 | 0.001 α |

| Anxiety | 8.30 ± 3.05 | 14.33 ± 1.29 | 0.001 α |

| Stress | 8.12 ± 2.38 | 11.91 ± 1.33 | 0.001 α |

| ASA Score | 13.00 (4.00–24.00) | 40.00 (27.00–72.00) | 0.001 β |

α Independent t-test (mean ± SD), β Mann-Whitney U test [median (min-max)], γ chi-square test n (%). IUS: intolerance of uncertainty scale, ASA: adult separation anxiety

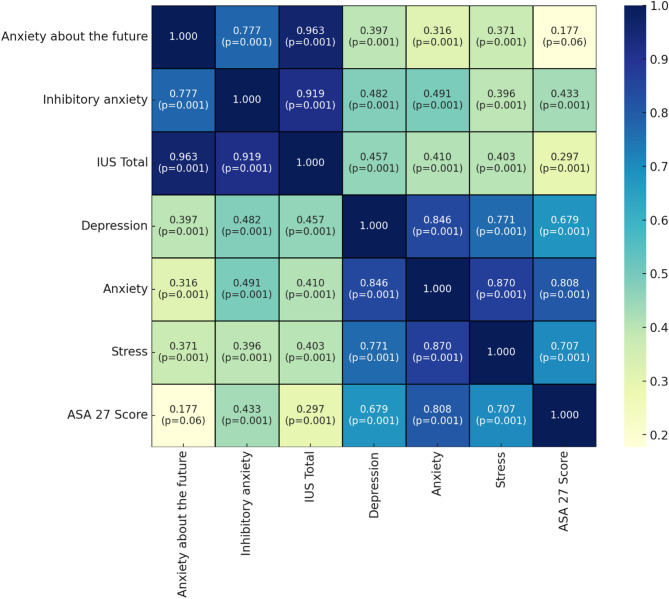

Fig. 1 shows the correlation analysis of the anxiety, depression and stress variables. The ASA-27 score, future anxiety(r = 0.177, p = 0.06), inhibitory anxiety (r = 0.433, p = 0.001), IUS total score (r = 0.297, p = 0.001), depression (r = 0.679, p = 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.808, p = 0.001), stress (r = 0.707, p = 0.001) show significant positive correlations. The IUS total score was significantly correlated with depression (r = 0.457, p = 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.410, p = 0.001), stress (r = 0.403, p = 0.001). Depression is highly correlated with anxiety (r = 0.846, p = 0.001), stress (r = 0.771, p = 0.001). Anxiety was significantly correlated with stress (r = 0.870, p = 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Correlation analysis of anxiety, depression, and stress variables

The correlation analysis (Table 4) demonstrated substantial positive correlations between ASA scores and psychiatric scale scores, including anxiety (r = 0.808, p = 0.001), stress (r = 0.707, p = 0.001), and depression (r = 0.679, p = 0.001). Total testosterone (r = 0.428, p = 0.001), DHEAS (r = 0.323, p = 0.001), estradiol (r = 0.466, p = 0.001), LH (r = 0.355, p = 0.001), and LH/FSH ratio (r = 0.528, p = 0.001) were all positively correlated with ASA scores among laboratory parameters. The ASA scores were negatively correlated with FSH (r=-0.239, p = 0.011). Other variables did not exhibit any significant correlation (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Correlation of ASA score with psychiatric scale scores and laboratory parameters

| ASA Score | ||

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric scale scores | ||

| Anxiety about the future | r |

0.177 0.060 |

| p | ||

| Inhibitory anxiety | r |

0.433 0.001 |

| p | ||

| IUS Total | r |

0.297 0.001 |

| p | ||

| Depression | r |

0.679 0.001 |

| p | ||

| Anxiety | r |

0.808 0.001 |

| p | ||

| Stress | r |

0.707 0.001 |

| p | ||

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| Total Testosterone | r |

0.428 0.001 |

| p | ||

| DHEAS | r |

0.323 0.001 |

| p | ||

| Estradiol | r |

0.466 0.001 |

| p | ||

| Prolactin | r |

0.101 0.286 |

| p | ||

| LH | r |

0.355 0.001 |

| p | ||

| FSH | r |

-0.239 0.011 |

| p | ||

| LH/FSH Ratio | r |

0.528 0.001 |

| p | ||

IUS: intolerance of uncertainty scale. DHEAS: dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, LH: luteinizing hormone, FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first study investigating adult separation anxiety symptoms in women with PCOS. According to the findings of our study, 28.9% of women with PCOS had separation anxiety symptoms above the cut-off score. There was a significant positive correlation between separation anxiety scale scores and stress, anxiety, depression and intolerance of uncertainty scores. The group with separation anxiety above the cut-off score had significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress and intolerance of uncertainty than the group with separation anxiety below the cut-off score.

Psychological comorbidities are known to be higher in women with PCOS. In particular, the prevalence of comorbid anxiety and/or depression is higher. According to a meta-analysis conducted by Cooney et al. in 2017, women diagnosed with PCOS had a threefold increased risk of experiencing moderate to severe depression symptoms and a fivefold increased risk of experiencing severe anxiety symptoms compared to women who do not have PCOS [27]. In 2021, in a study investigating anxiety-like and depression-like behaviors in women with PCOS, the prevalence was 26.1% and 52.0%, respectively [28]. In 2025, Lee et al. reported the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with PCOS to be approximately 33% [29]. In two follow-up studies in Taiwan and Australia, women with PCOS who did not have psychiatric disorders at baseline had a higher risk of developing depression and anxiety during follow-up [30, 31]. A 2023 meta-analysis by Nasiri-Amiri et al. revealed increased prevalence of anxiety and depression among adolescents and young women with PCOS, underscoring the notion that these psychological challenges manifest early and last throughout life [32].

There has been lately interest in the connection between anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty. It has been suggested as a transdiagnostic factor in the psychopathology of anxiety disorders, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression and generalized anxiety disorder [33]. In the literature, there are few studies examining adult separation anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty [20, 34]. In a study investigating the relationship between adult separation anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in a non-clinical group, it was reported that adults with significant separation anxiety symptoms may also be characterized by high levels of intolerance of uncertainty. It was underlined that, depending on personal and contextual factors, this image can potentially have an impact on the overall pattern of symptoms related to depression and anxiety [34]. Değirmenci et al. investigated the relationship between adult separation anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in pregnant women and reported that those with high separation anxiety scores also had high intolerance of uncertainty scale scores [20]. Boelen et al. In a study conducted with university students, it was shown that intolerance of uncertainty was significantly related to the symptom levels of adult separation anxiety. They also found that intolerance of uncertainty was significantly positively associated with generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety and depression symptom levels [35].The reported links between ASA and IU in PCOS patients point to a potential feedback loop in which intolerance of reproductive and health-related uncertainty may increase attachment insecurities, especially in those predisposed to ASA. Hormonal dysregulation could moderate these mechanisms and social stigma could aggravate them [34]. In the light of these data, it is seen that our findings are compatible with the literature and our research results support that adult separation anxiety symptoms can be seen at a high rate in PCOS patients. In our study, in line with the literature, intolerance of uncertainty scores were significantly positively correlated with depression, anxiety, stress scores and adult separation anxiety scores. These findings suggest that, as previous studies have suggested, intolerance of uncertainty may be transdiagnostically associated with different types of anxiety and depression-related psychopathologies in individuals with adult separation anxiety symptoms.

Given that women with PCOS frequently experience heightened anxiety and uncertainty related to fertility, body image, and social stigma, it is plausible that ASA symptoms may also be elevated in this population. These observations are also corroborated by qualitative research. In their 2024 study, Wright et al. discovered that women with PCOS frequently characterise their experiences as being influenced by persistent ambiguity regarding their health, identity, and future. These factors may contribute to emotional distress and attachment-related insecurity [9]. Social stigmatisation associated with clinical symptoms can lead to loss of self-confidence, social withdrawal and increased psychological stress levels, particularly in women who deviate from social norms regarding body image [36]. Women with PCOS often struggle with body image distress, which can lead to feelings of depression and anxiety [37]. Various factors such as ethnicity, place of birth and cultural background can influence how women perceive and cope with PCOS symptoms, potentially exacerbating anxiety and depression [38]. Consequently, it may be said that both hormonal imbalances and psychosocial influences contribute to the emergence and intensity of mental symptoms in these people, and that these aspects may mutually reinforce one another. A clearer understanding of the interplay between hormonal, psychological, and sociocultural factors in PCOS may inform both more holistic and more targeted approaches to treatment planning.

The hormonal abnormalities in PCOS, especially abnormalities in insulin and androgens such as testosterone, further complicate the situation. Research indicates that elevated testosterone levels may exacerbate anxiety symptoms by influencing the activity of emotional processing centers, including the amygdala [39, 40]. Similarly insulin resistance has been shown to facilitate the emergence of mental symptoms by triggering inflammatory processes and influencing the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [41, 42].PCOS symptoms such as hirsutism, insulin resistance and androgen levels, which are the clinical equivalent of hormonal disorders, have been found to affect cognitive performance and quality of life, leading to anxiety, depression and social maladjustment [43]. Furthermore, recent clinical research has demonstrated that the metabolic characteristics of PCOS are substantially correlated with impairments in female sexual function, indicating a more extensive effect on psychosocial well-being [44].

In the literature, the prevalence rate of adult separation anxiety in the community has been reported to be approximately 6–7% [17]. There are studies investigating the combined symptoms of adult separation anxiety with various psychiatric disorders. According to the findings of Manicavasagar et al., the prevalence of adult separation anxiety was found to be 46% in patients who suffered from either panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder [45]. In another study involving adult anxiety disorder patients, the combination of symptoms of adult separation was found to be 23–42% [17]. In 2016, Gesi et al. found an additional diagnosis of adult separation anxiety in 53.2% in a study conducted with panic disorder patients [46]. According to the findings of our study, 28.9% of women with PCOS had separation anxiety symptoms above the cut-off score. Due to the absence of any other research in the existing literature about separation anxiety in patients with PCOS, it was not possible to compare this rate with other study groups that had the same diagnosis. In 2015, a large-scale study investigating separation anxiety disorder among countries in the World Mental Health Survey reported that, when controlling for age and country, woman gender and low educational level could be considered predictors of adult separation anxiety symptoms [47].The fact that our sample consisted of women and that 45.6% of them had an education level below high school may have contributed to this high rate. The frequent occurrence of comorbid mental disorders in PCOS patients and the fact that the most common comorbid disorders are anxiety and depression may contribute to this rate being higher than in the normal population. It should also be noted that the Uncertainty Intolerance Scale comprises two subscales. In our study, symptoms of adult separation anxiety were more strongly associated with the inhibitory anxiety subscale than with the anxiety about the future subscale. This suggests that, in women with PCOS, inhibitory anxiety — reflecting behavioural inhibition in the face of uncertainty — may play a more central role in adult separation anxiety symptoms than purely cognitive concerns about the future. These results are consistent with theoretical models that propose avoidance and behavioural withdrawal as salient features of ASA. Future studies may benefit from investigating these distinct contributions of IU subtypes further to better tailor psychological interventions.

Limitations

There is limited data on adult separation anxiety in the literature. Our study contributes to the literature on this subject and draws attention to separation anxiety disorder which is often overlooked by clinicians. We believe that adult separation anxiety should not be ignored in a condition such as PCOS in which psychological comorbidity is very common. However, our study also has some limitations. The small sample size is one of these limitations. Another limitation of our study is that the symptoms of adult separation anxiety and other mental symptoms were evaluated with self-report scales. A further limitation with our research is that we didn’t have a matched healthy control group, which is people who don’t have PCOS and don’t have any current mental health problems. This makes it hard for us to tell whether the levels of ASA and accompanying symptoms we see are just in women with PCOS or if they are part of a larger trend in the general population. Also, even though this was a quantitative study, we know that the way the researcher and subject interacted might have affected the results. Because healthcare professionals, including a gynaecologist, gathered the data in a clinical context, participants’ answers may have been affected by how they saw themselves as an authoritative figure or how they thought others would see them. When looking at self-reported psychological symptoms, this positional element should be taken into account.

Conclusion

In our study, 28.9% of patients with PCOS had separation anxiety symptoms above the cut-off score. In addition, people with high adult separation anxiety scores had higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress and intolerance to uncertainty than those without. It is important to keep adult separation anxiety symptoms in mind when evaluating mental symptoms in patients with PCOS. Future research should prioritize doing longitudinal studies to track the progress of women with PCOS and investigate the factors that may impact the occurrence of PCOS, as well as depression and anxiety symptoms, in this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the study participants and the healthcare professionals who assisted in data collection.

Abbreviations

- ASA

Adult Separation Anxiety

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DASS-21

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21

- DHEAS

Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate

- FSH

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone

- IUS

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale

- LH

Luteinizing Hormone

- PCOS

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Author contributions

ÖG, FA and MA contributed to the concept and design of the study. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were carried out by ÖG and FA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MA. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has not received any grants from funding organizations in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: 2022/325, Date: June 3, 2022). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Khobragade NH, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Insights into its prevalence, diagnosis, and management with special reference to gut microbial dysbiosis. Steroids. 2024:109455. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bozdag G, et al. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu R, et al. New insights into the interaction between polycystic ovary syndrome and psychiatric disorders: a narrative review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;164(2):387–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blay SL, Aguiar JV, Passos IC. Polycystic ovary syndrome and mental disorders: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Podfigurna-Stopa A, et al. Mood disorders and quality of life in polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(6):431–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, et al. Transtheoretical model-based mobile health application for PCOS. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenwood EA. The puzzle of polycystic ovary syndrome, depression, and anxiety. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(5):821–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan M, et al. Women’s experience of polycystic ovary syndrome management: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;164(3):857–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright PJ, Dawson RM, Corbett CF. Exploring the experiential journey of women with PCOS across the lifespan: a qualitative inquiry. Int J Womens Health. 2024;16:1159–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson-Helm M, et al. The needs of women and healthcare providers regarding polycystic ovary syndrome information, resources, and education: a systematic search and narrative review. Semin Reprod Med. 2018;36(1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rettie H, Daniels J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2021;76(3):427–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews JL, et al. The effect of intolerance of uncertainty on anxiety and depression, and their symptom networks, during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morriss J, et al. Intolerance of uncertainty heightens negative emotional States and dampens positive emotional States. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1147970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Text revision; 2000.

- 15.Diamond D, Keefe JR. Separation anxiety: the core of attachment and separation-individuation. Psychoanal Study Child. 2024;77(1):251–74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akkus M, Akkuş F. The association of dysfunctional attitudes and adult separation anxiety in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silove DM, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult separation anxiety disorder in an anxiety clinic. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bögels SM, Knappe S, Clark LA. Adult separation anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(5):663–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boelen PA, Reijntjes A, Carleton RN. Intolerance of uncertainty and adult separation anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther. 2014;43(2):133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sevil Degirmenci S, et al. The relationship between separation anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(17):2927–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manicavasagar V, et al. A self-report questionnaire for measuring separation anxiety in adulthood. Compr Psychiatr. 2003;44(2):146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diriöz M, et al. Ayrılma Anksiyetesi Belirti Envanteri Ile Yetişkin Ayrılma Anksiyetesi Anketinin Türkçe Versiyonunun Geçerlik ve güvenirliği. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2012;23(2):108–16.22648873 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carleton RN, Norton MPJ, Asmundson GJ. Fearing the unknown: a short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(1):105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarıçam H, et al. The Turkish short version of the intolerance of uncertainty (IUS-12) scale: the study of validity and reliability. Route Educational Social Sci J. 2014;1(3):148–57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sariçam H. The psychometric properties of Turkish version of depression anxiety stress scale-21 (DASS-21) in health control and clinical samples. J Cogn Behav Psychotherapies Res. 2018;7(1):19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooney LG, et al. High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(5):1075–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin H, et al. The prevalence and factors associated with anxiety-like and depression-like behaviors in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:709674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee IT, et al. Depression, anxiety, and risk of metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2025. 110(3):750-756. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Hung J-H, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders following polycystic ovary syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart R, Doherty DA. The potential implications of a PCOS diagnosis on a woman’s long-term health using data linkage. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2015;100(3):911–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasiri-Amiri F, et al. Depression and anxiety in adolescents and young women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2023;35(3):233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holaway RM, Heimberg RG, Coles ME. A comparison of intolerance of uncertainty in analogue obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20(2):158–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iannattone S, et al. Profiles of intolerance of uncertainty, separation anxiety, and negative affectivity in emerging adulthood: a person-centered approach. J Affect Disord. 2024;345:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boelen PA, Vrinssen I, van Tulder F. Intolerance of uncertainty in adolescents: correlations with worry, social anxiety, and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(3):194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geller S, Levy S, Avitsur R. Body image, illness perception, and psychological distress in women coping with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Health Psychol Open. 2025;12:20551029251327441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alur-Gupta S, et al. Body-image distress is increased in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and mediates depression and anxiety. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(5):930–e9381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheikh J, et al. Emotional and psychosexual well-being is influenced by ethnicity and birthplace in women and individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome in the UK and India. BJOG. 2023;130(8):978–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filova B, et al. Effects of testosterone and estradiol on anxiety and depressive-like behavior via a non-genomic pathway. Neurosci Bull. 2015;31:288–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Wingen GA, et al. Testosterone increases amygdala reactivity in middle-aged women to a young adulthood level. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(3):539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amaral CLd, et al. Activation of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor prevents against microglial-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in hypothalamic neuronal cells. Cells. 2022;11(14):2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang C, et al. Nonlinear association between depressive symptoms and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance: a cross-sectional analysis in the American population. Front Psychiatry. 2025;16:1393782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehrabadi S, et al. Association of acne, hirsutism, androgen, anxiety, and depression on cognitive performance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2020;18(12):1049–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cevik Dogan M, Yoldemir T. The association between female sexual function and metabolic features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in Turkish women of reproductive age. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2024;40(1):2362249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manicavasagar V, et al. Continuities of separation anxiety from early life into adulthood. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gesi C, et al. Separation anxiety disorder from the perspective of DSM-5: clinical investigation among subjects with panic disorder and associations with mood disorders spectrum. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(1):70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silove D, et al. Pediatric-onset and adult-onset separation anxiety disorder across countries in the world mental health survey. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(7):647–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.