Abstract

Background

People using anabolic steroids adopt different strategies to manage risks and harms associated with the use of these substances. We investigated how users learn, develop and incorporate risk-management strategies, as well as the events triggering changes in their health-related behaviour.

Methods

Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted with anabolic steroid users living in the UK to discuss their risk-management strategies (19 males, 1 female; median age = 35.5 years; median time of anabolic steroid use = 9 years). Online interviews were transcribed verbatim and qualitative data was analysed via iterative categorisation.

Results

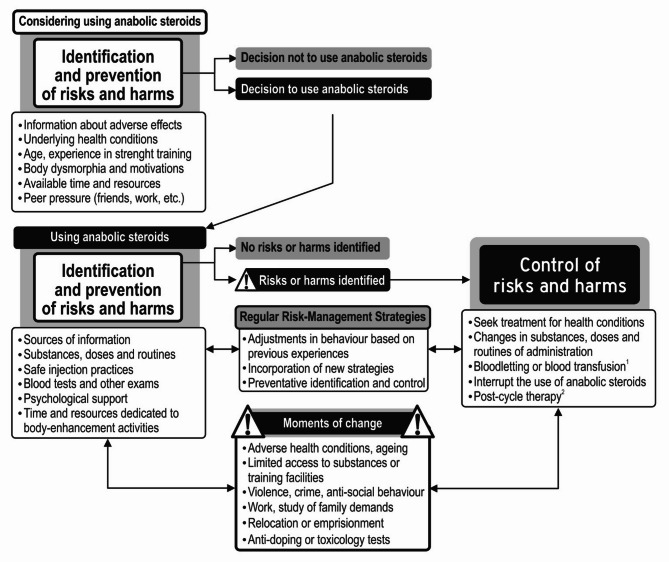

The use of risk-management strategies was characterised as a continuous cycle of identification, prevention and control of risks and harms. Preventative strategies were more commonly adopted after many years of anabolic steroid use. Changes in life circumstances and adverse health conditions were described as common triggers for changes in behaviour, including the cessation of anabolic steroid use.

Conclusion

Our findings can inform interventions aimed at increasing awareness and promoting healthier behaviours among people who use anabolic steroids. Further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the risk-management strategies employed by this population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12954-025-01269-x.

Keywords: Anabolic steroids, Human-enhancement drugs, Harm-reduction

Introduction

Potential harms associated with the use of androgenic-anabolic steroids (henceforth anabolic steroids) include hypogonadism [1, 2] cardiovascular disease [3, 4], cognitive deficits [5], anxiety [6], and increased aggressiveness [7]. Many factors impact the likelihood and severity of adverse health conditions associated with the use of these drugs, including genetic predispositions, comorbidities, types and doses of substances, age, sex, and the duration of use [8].

People using anabolic steroids may adopt a variety of practices to identify, prevent and manage risks and harms. These practices can be described as risk-management strategies [9], and include decisions about doses and substances in use; having blood tests done to monitor their health; seeking general practitioners (GPs) and other sources of support to treat adverse health conditions [10–12]. People using anabolic steroids frequently develop, incorporate and share risk-management strategies, building communities of practice with the purpose of minimising harms and maximising the perceived benefits of the drugs [13–17]. Recent studies have recognised the importance of understanding these strategies– frequently based on self-experimentation and anecdotal reports [11, 18–20]– to improve health interventions [11, 21]. However, little is known about how risk-management strategies are adopted, integrated, and evolve over the course of an individual’s experience with anabolic steroids.

The aim of this study is to characterise the strategies adopted by a cohort of people using anabolic steroids and identify triggers for their changes in health behaviours, therefore providing a better understanding of potential intercepts between risk-management strategies and the development of health policies.

Materials and methods

Study design

A qualitative study was designed using semi-structured interviews, allowing an in-depth investigation of risk-management strategies associated with the use of anabolic steroids. The results from an online survey conducted by our team [22] were used to identify some of the strategies investigated in this study. Furthermore, individual answers from the survey’s participants were used to customise the interviews, and to provide a better understanding of their personal experiences. The complementary use of quantitative and qualitative analyses is considered a useful method to investigate complex behaviours [23, 24].

Recruitment of participants

We aimed to recruit a sample with a diversity of demographic characteristics and experiences with the use of anabolic steroids. This theoretical sample [25] would ideally illustrate a range of risk-management strategies adopted by different users [26]. The inclusion criteria were being at least 16 years old, residing in the UK at the time of the study, and having used anabolic steroids without a medical prescription within the past 12 months. Based on the cohort of similar studies [27–31], we estimated that a minimum of 20 participants would be required to achieve theoretical saturation, i.e., when further data collection would not provide additional theoretical insight to the analysis [32]. Participants were recruited amongst the respondents of the aforementioned online survey who agreed to be invited for an interview. As the number of participants selected from the survey was considered insufficient for theoretical saturation, additional participants were recruited through advertisements on social media platforms and bodybuilding forums. Furthermore, participants who agreed to be interviewed were invited to refer acquaintances to the research team for eligibility screening and potential selection. Participants received a £20 voucher in appreciation for their time.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were used to investigate the participants’ history of anabolic steroid use and risk-management strategies. The interviews were conducted remotely by the first author using Microsoft Teams. The semi-structured interview protocol covered the following areas: (i) Background and rapport (i.e., occupation and strength-training routines); (ii) History of anabolic steroid use; (iii) Identifying, preventing and treating harm; (iv) Engagement with health services; (v) Other sources of support; (vi) Suggestions for improving the support for people using anabolic steroids. The topic guide can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Data analysis

Qualitative data was analysed following the principles of framework [33] and iterative categorisation [34, 35]. Transcriptions of the interviews were automatically generated by Microsoft Teams. Transcription mistakes were corrected, and the interviews were anonymised by the first author, warranting familiarisation with the data [34]. A preliminary thematic framework (available in the Supplementary Material) was created using a combination of deductive and inductive themes– the former, based on the topic guide; the latter, raised during the interviews. Based on this framework, we assigned labels (codes) to each theme and stored thematic-related excerpts from the interviews using NVivo 1.7. Raw data was exported to Microsoft Word in a separate file for each code. Selected codes from each sub-theme were compiled in a single paragraph for descriptive analysis, followed by interpretive analysis to identify patterns and associations within the data. Some items (demographics, risk-management strategies adopted before the first cycle, years of anabolic steroid use, frequency of blood tests) were summarised in theme-specific spreadsheets in Microsoft Excel to facilitate comparisons. Codes from the preliminary framework were synthesised into two overarching themes: (i) identification and prevention of risks and harms and (ii) treatment and control of risks and harms. We compiled a list of verbatim quotations illustrating the codes in each theme. Excerpts from the interviews were used to exemplify the participants´ risk-management strategies. We compared participants’ experiences with the available evidence regarding the use of anabolic steroids (deductive conceptualisation) and developed a model of strategies based on data from this research and previous studies (inductive conceptualisation). The analysis was finalised with a critical reflection and the discussion of our findings.

Results

Amongst the respondents of an online survey (n = 883), 11 (1.2%) participants agreed to take part in this study. Additional interviewees were recruited via social media and online forums (n = 4), and from other participants’ invitations (n = 5). Twenty interviews were performed between November 2021 and March 2022, with an average duration of 49 minutes (range = 37 to 114 minutes). The majority of participants were males (one was female) of white ethnicities (two were of Asian ethnicities) residing in England (three were living in Scotland, one in Wales). As shown in Table 1, the sample had a median age of 35.5 years (26 to 58 years). The median age of participants’ first use of anabolic steroids was 25.5 years (18 to 36 years), with a median of 9.0 years of use (< 1 to 36 years). Participants practiced strength training for a median of 5.5 years (1 to 24) before using anabolic steroids. The sample included people with a diversity of professional backgrounds, five of them being involved in strength-sports competitions. All the males were using injectable anabolic steroids or a combination of oral and injectable compounds, whilst the female participant used only oral substances.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics

| ID | Age | Years of AS* | ST before AS** | ST participation | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | 35 | 13 | 04 | Strongman | Teaching assistant |

| P02 | 54 | 36 | 02 | Bodybuilding | Senior manager |

| P03 (F) | 27 | < 1 | 08 | Powerbuilding | Researcher |

| P04 | 28 | 05 | 03 | Strength training | Maintenance engineer |

| P05 | 30 | 05 | 09 | Para-Powerlifting (C) | Gym staff |

| P06 | 32 | 06 | 06 | Strength training | Funeral director |

| P07 | 57 | 30 | 10 | Powerlifting | Train diver |

| P08 | 41 | 21 | 02 | Strength training | Technology director |

| P09 | 26 | 01 | 05 | Bodybuilding | Administrator |

| P10 | 53 | 28 | 05 | Bodybuilding (C) |

Sales manager (former Police Officer) |

| P11 | 58 | 26 | 03 | Bodybuilding | Marketing director |

| P12 | 46 | 08 | 10 | Strength training | Medical Doctor |

| P13 | 36 | 01 | 15 | Bodybuilding | Construction manager |

| P14 | 28 | 10 | 03 | Bodybuilding | Preferred not to say |

| P15 | 31 | 03 | 02 | Powerlifting (C) | Personal trainer |

| P16 | 32 | 06 | 14 | Strength training | Project manager |

| P17 | 52 | 28 | 06 | Strength training | Personal trainer |

| P18 | 29 | 10 | 01 | Bodybuilding (C) | Personal trainer |

| P19 | 52 | 13 | 24 | Powerlifting (C) | Sports physiologist |

| P20 | 40 | 06 | 18 | Bodybuilding | Healthcare assistant |

* Years of anabolic steroid use. ** Years of strength-training before using anabolic steroids. F: Female. ST: Strength training: C: Competitive athlete

The participants’ risk-management strategies are detailed below.

Reducing risks and preventing harms

In general, interviewees described their use of anabolic steroids as a conscious exposure to the risk of adverse effects in order to obtain the perceived benefits of these substances. Many participants adopted similar risk-management strategies before and during their use of anabolic steroids, frequently changing health behaviours as they gained experience with the drugs.

Self-assessment before the first cycle

All participants considered it was best to start the use of anabolic steroids at an older age, with some of them suggesting a threshold between 21 and 30 years of age. They advised against using anabolic steroids when ‘people are naturally more impulsive and a bit reckless’ [P07], therefore increasing the risk of over-exposure in order to accelerate the process of body enhancement. This advice seems to go against current trends observed in online communities of anabolic steroid users.

When I started [using anabolic steroids], back in 2001, 2002… Everybody was saying things like… don’t just jump straight onto enhancement, get your training in check, get your diet in check, understand how your body works, understand what kind of training works for you, get a good base of natural physical strength and ability before you start to use these things… Everybody was saying that, and I ignored it. I think a lot of young people do. Nowadays, what we have is young people advising other young people on what to do to look like an Instagram model… and it tends to involve ridiculous amounts of drugs at a very young age. [P08]

A thorough assessment of health and individual vulnerabilities before using anabolic steroids was considered an important strategy to reduce the risk of adverse effects.

Are you healthy before starting [anabolic] steroids? What does the rest of your life look like? (…) There’s a good chance that [anabolic steroids] are going to negatively impact your health. So, if you’re already starting from a compromised place, things could get worse quickly. [P03]

Participants also recommended prospective users to reach their ‘natural limits’ in strength training before considering using anabolic steroids.

I was only training about like 2 years before I went on [anabolic] steroids. Regrettably. I think that was far too soon. I think I should have explored my natural potential. But as soon as you go on, you don’t have the option again. [P15]

Proficiency in the performance of basic exercises was considered an indicative of when someone would be “ready” to use anabolic steroids.

If someone says to me… “Hey man, I want to take a cycle. What should I do?” The first thing I’d ask is “How much do you bench, how much you squat, how much you deadlift? If you’re not benching your body weight, squatting and deadlifting twice your body weight, go back to the gym. Eat well, train hard. You don’t need anything” [P19].

Some users tend to overlook the risks of long-term exposure to anabolic steroids until they experience severe adverse effects, as illustrated by P08, a man who used these drugs used for 21 years before suffering a myocardial infarction at the age of 40.

As a 41-year-old man now, I wish I’ve never started. I would say I definitely didn’t have enough training experience to warrant it. One of the regrets I have is that I wish I waited a lot longer. If I was going to use those substances again, I would want to really maximize all of the other training variables and lifestyle variables before doing that. [P08]

Choosing doses and patterns of use

Many participants mentioned the benefits of using the minimal possible dose of anabolic steroids to achieve their body-enhancement goals. According to them, some people join a ‘chemical race against themselves’ [P19] believing that muscle gains will be indefinitely proportional to the quantity of drugs they use. This behaviour was considered dangerous and ineffective, leading towards a ‘saturation point’ [P17] where marginal gains in muscle mass were accompanied by the exponential risk of experiencing adverse effects.

I realized that I was just taking too much [anabolic steroids] (…) If I took 100 mL or took 300 mL it doesn’t mean I was three times stronger. (…) You’re just being like a sponge. [P07]

Regarding different routines of anabolic steroids’ administration, about half of the participants adhered to ‘cycling’, with several weeks of high dosages followed by an ‘off (abstinent) period’ of variable duration.

I think the best the best harm-reduction that you can do is: Please don’t take much [steroids], and come off for the amount of time that you’ve been on. So time ‘on’ equals time ‘off’. Definitely come off until you’ve recovered, and don’t take much. [P17]

I don’t like it [blast-and-cruise]. People do it for because they’re scared to come off. I know people who are cruising on the same amount that I would take when I’m on [cycle], and they think that they’re cruising. [P17]

Those who chose a continuous exposure to the drugs– commonly referred to as “blast and cruise,” a regimen characterized by high-dose cycles followed by extended periods of lower doses [36]– emphasized the benefits of preventing loss of muscle mass and withdrawal symptoms. Some of them described this approach as a long-term commitment to the use of anabolic steroids.

People are now more than happy to accept that they will be on testosterone for the rest of their lives. That small injection you have to do, maybe twice a week, it’s going to give you such a better quality of life. Why would you choose to not do that? [P18]

The continuous exposure to anabolic steroids was frequently intertwined with the concept of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), and many participants described their routines as ‘being on TRT between cycles’ [P01]. Their definitions of TRT or ‘maintenance doses’ varied from 100 mg of testosterone administered biweekly to 300 mg per week of various compounds.

I take trenbolone, Masteron [dostranolone] and testosterone propionate. Basically, I’ll just do kind of… 12 to 16 weeks of that, and then I’ll just go down to a TRT dose. I never come off. (…) I’d much rather stay on a small dose of testosterone throughout my life until I die, than come off and watch myself slowly turn into a creepy massive old man. [P02]

Seeking information

Participants used many different sources of information about anabolic steroids, including friends, providers of the drugs, books and online material. Most admitted having little knowledge about harm-prevention strategies before using the drugs for the first time.

Before the internet, there was nothing out there. (…) It was an underground thing. You looked for the biggest person in the gym and thought… “He must know someone”. And that’s how we did it. So, I never knew nothing about the backside of it. You know, the protection, or precautions. [P07]

The advice from friends and ‘gym buddies’ was frequently described as inaccurate or even harmful.

In the beginning, my friends [at the gym] were recommending me very high dosages. And they were recommending me certain kinds of anabolics that are not recommended for a first cycle. Such as trenbolone, for example. None of them had any knowledge about PCT [post-cycle therapy]. [P06]

According to the interviewees, it can be challenging to identify reliable information amidst the plethora of anecdotal reports and folk-pharmacology available online.

I think the problem [with online forums] is… everyone has an opinion, and all you need is an avatar and a login, and you can provide advice for people. And these people… you don’t know their experience. They may have copied and pasted it. They may have never taken steroids in their life, but they’ve done a bit of research and they think they’re some type of experts.(…) I have been in some of those sites, very much in the past, but in the last few years I tend to look for guys that I trust, that have a good reputation in bodybuilding, in terms of PEDs [performance-enhancement drugs] and nutrition. [P02]

Many participants recommended caution when following drug and training routines found in forums and other online platforms, as they rarely take into account individual risks and vulnerabilities.

Yeah, [the online forums] can be quite a mixed batch, because there’re different levels of experience there. The people who are training at a very high level to compete, they’re running very, very large cycles, very, very intense cycles. Then you have people who are just starting (…) So I think it would be easy to follow the wrong advice because you could read something that’s maybe far too advanced to yourself and think, oh OK, I need to do this. [P04]

The only woman in the sample described her difficulties in finding information about female-specific effects of anabolic steroids, such as disruptions to the menstrual cycle [1, 37]. Online communities dedicated to women using these drugs were viewed as safe spaces for sharing experiences and support.

Steroidsxx, on Reddit, is a forum dedicated to females, specifically to talk about steroids, particularly in the context of bodybuilding (…) When I missed my period, I tried to look for information and I couldn’t find anything. I went to [these forums] and people said it happen to them (…) I found the community quite well informed. [P03]

Some participants hired ‘steroids coaches’ to supervise their cycles, whilst others acted as coaches themselves, offering advice to less experienced users. Participant P13, who started using anabolic steroids after 15 years of drug-free bodybuilding, described mixed experiences with the coach who guided him through his first cycle.

I used an online coach (…) He gave me advice on how to prevent adverse effects. He mentioned drugs like metformin, telmisartan and things like regular blood checks, monitor blood pressure, monitor my blood glucose weekly, that sort of thing. (…) I used a low dose of Trenbolone for about six weeks, and I suffered from some mental side effects. Anxiety, paranoia, night sweats. I was using testosterone, trenbolone, T3 [thyroid hormone] and clenbuterol (…) I was extremely anxious, and I was really paranoid. [P13]

Many participants sought advice from their suppliers of anabolic steroids before changing their risk-management strategies:

I’ve done that in the past [ask information from a supplier], but not anymore. Do not take advice from the guy you buy steroids from. All he’s gonna do is take your money and you’re gonna see him more frequently than you would like. He might seem like a nice dude, but all he cares about is money. [P18]

Accessing injectable equipment

Most participants were not using the needle and syringe programme (NSP) to access sterile injectable equipment, although a few have done so in the past. Being able to buy their own injectable equipment was considered something that distinguished them from other drug users.

I would never go [to the NSP]. I would feel embarrassed to go there. I might be a drug user of anabolic steroids, but I don’t consider myself to be a junkie to go there. (…) The only steroid users who are going to the NSP are the ones who don’t have any money. Everybody else is going online and buying packs. (…) Why would you want to go to an NSP and seat with a bunch of junkies and queue to get free needles? [P19]

Monitoring health: blood test and other exams

Nearly all participants highlighted the importance of having blood tests to monitor their health whilst using anabolic steroids. Having blood tests was perceived as a preventative measure, informing dose adjustments and prompting them to seek help to treat identified abnormalities. With the exception of a few interviewees who monitored their health from the start– such as P03, who quit the drugs after the first sign of liver abnormalities– the majority of participants only started having regular blood tests after several years of drug use.

I probably used [anabolic steroids] for some good thirteen, fourteen years without having any kind of real tests. It sounds moronic now, but I would gauge my health just by kind of “how I felt”. (…) So, I started doing blood tests. They were annual for the first couple of years, and then I was having them every three months. I think I was starting to take things more seriously. [P08]

Some male participants who had sex with men reported having blood tests when screening for HIV in Sexual Health Clinics specialised in the support for the LGBTQIA + population, which were perceived as non-judgmental about the use of anabolic steroids.

The only time I have had a good response from NHS staff regarding steroid use was when I attended 56th [Dean] Street in London (…) They are excellent and they are totally nonjudgmental. They are there to help people. They are like… “OK you do steroids? Fine. Do you need needles, syringes? [P01]

However, most participants who approached their GPs for blood tests had their requests denied.

My GP said: “Taking steroids is a personal choice, and I don’t really think that we should be supporting you, because you shouldn’t really be taken them”. And I said: “So if I was drinking all day and I had a problem with my liver, would you suggest that I wouldn’t be allowed to have a test on my liver?” (…) And he said: “What you gonna do?” I said, “I just have to pay for the tests”. And that’s what I’ve done ever since. [P02]

Some participants considered that people using anabolic steroids should expect to pay for their own blood tests and other exams.

Get your blood work done. If you can’t afford blood work, you can’t afford gear [anabolic steroids]. And the other way around, if you can afford to buy gear, you can afford to get your blood work done. [P18]

Likewise, being able to afford an ‘enhanced lifestyle’ (e.g., intensive training routines, special nutrition, private health checks, etc.) was seen as a protective factor against adverse effects. One participant noted that the necessity to seek private services deepens the inequalities in users’ access to healthcare, potentially increasing the risk of adverse effects.

People who can pay for private exams, medical consultations and testosterone prescriptions are less likely to have problems. (…) Doctors, dentists, lawyers, the entire City of London… they can afford that. They look great, they are healthy, nothing will happen to them. But the average 20-year-old, living in a council state in South London… He pays £30 for a vial of steroids, takes one shot per week, he won’t even have a blood test. [P19]

Managing harms

The majority of interviewees who required treatment for adverse effects turned to informal sources of support– such as self-directed research, friends, and online forums– before consulting healthcare professionals. Their strategies to manage harm included changing drug routines, using ancillary drugs bought from illicit markets, and interrupting the use of anabolic steroids.

Seeking GPs and other health professionals

Most participants avoided seeking GPs for the treatment of adverse health conditions. In their experience, physicians would frequently try to discourage their use of anabolic steroids by refusing treatment for health conditions such as high-blood pressure [3].

It happened to somebody I know. He was running [blood pressure] 180 × 110 [mmHg], and the doctor said: “You stop what you’re doing. I’m not prescribing [blood pressure] medication”. So, what did this guy do? He went to buy blood pressure medication in the black market. [P20]

The interviewees also feared having the use anabolic steroids mentioned in their medical records, sometimes withholding this information even in the face of clinical emergencies. Such was the case of P12, a 46-year-old medical doctor.

I was always very concerned about invalidating things like life insurance, so I have never discussed it [anabolic steroid use] with GPs at all. Even to the extent that, when I was taken to hospital with a strangulated bowel (…) I was told “We really need to know whether you have anything affecting your blood volume, or your ability to coagulate your blood”, I still denied it. [P12]

However, some participants described a good relationship with their GPs, who were considered supportive and non-judgmental.

My private doctor wrote my GP a letter making him aware of our TRT therapy. They’ve got a good line of communication with one another. I wouldn’t say my GP is knowledgeable [about anabolic steroids], but I would say he is tolerant. [P15]

Others sought remote support from foreign-based health professionals, who reviewed their blood tests and recommended ancillary drugs.

I get my cycles now from a guy in [name of an European country] who is a doctor. He kind of specializes in training people and advice, writing programs and steroid cycles for people. (…) It’s not his professional practice per say. He’s an Epidemiologist, but he trains and advises a lot of people. [P01]

Bloodletting and blood donation

Some participants practiced bloodletting (i.e., drawing and disposing of venous blood) to manage elevated haematocrit and high blood pressure. According to them, instructions to perform bloodletting can be easily found online, allowing users to do it on themselves. Alternatively, it is possible to find health professionals willing to provide the procedure.

My haematocrit will usually go up, whenever I start doing higher doses. So, I’ll usually donate blood or do bloodletting whenever I’m on cycle to try and keep that down. (…) I had bloodletting done from an NHS nurse. She does blood work on the side, and also advises on blood tests for people that take performance enhancements. [P05]

Other participants also donated blood as a way to manage drug-induced polycythaemia, despite being aware that individuals using anabolic steroids should refrain from donating blood products.

I had high haematocrit during my second cycle. (…) So, I went to donate blood. Obviously, I’m aware that the guidelines say that you should not donate blood if you’re injecting steroids. So the day after, I called them and I said that I felt very sick, that I probably have an infection and so they discarded my blood. [P06]

Interrupting the use of anabolic steroids

Most participants reported eventual interruptions in the use of anabolic steroids as voluntary decisions with few adverse effects. There was a general perception of being in control of their own drug use. P20 described his intention to restore his natural production of testosterone with post-cycle therapy (PCT) in order to conceive a child.

My wife decided that was the perfect time to have a baby. At the beginning I thought “let me finish this cycle”, but then I realized that that was a very “drug addict” way of putting the thing. (…) So, I stopped it. I did a pretty extensive PCT (…), and two months later my wife was pregnant. [P20]

Participants were asked how the closure of gyms and other social distancing measures implemented in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic affected their drug use and risk-management strategies. Some of them experienced mild disruptions in their access to online drug markets, and changes in drug use were described as having little impact in their lives. A few participants had unlicensed access to gyms during the pandemic, allowing them to keep their training routines.

We couldn’t train properly. Gyms were all shut. (…) I spoke to my GP and asked “what should I do?” (…) And he said “Don’t come straight off ‘cause you’re gonna have a crash. It’s best if you just go on a cruise, and just cruise”. He said “hopefully until it gets sorted”. And that’s what happened. But fortunately for me, I got to know my gym owner well. I’ve got a private key, so after two weeks, I was able to get back into a gym. [P07]

Some users downgraded to ‘maintenance doses’, training at home with improvised equipment. Others had longer ‘off-periods’, resuming their cycles as soon as the gyms re-opened, and advised their friends and clients to do the same.

When lockdown started, I gave some advice for everyone to cut their cycle down. (…) This was the best time to give your body a rest. (…) A lot of people listened to this. They run off the ‘gear’ for a year. They gave their bodies a rest. Some people never went back to competition. They realised… you know, “I don’t need this. I should have done this years ago”. [P19]

Many participants reported voluntarily interrupting their use of anabolic steroids, each experiencing varying withdrawal symptoms.

I ceased using anabolic steroids about three months ago. I’ve stopped completely, and I’ve had bloods done since, just the hormones. And everything is come back in line. (…) I didn’t feel any negative effects of steroid withdrawal, which is surprising. I didn’t really feel anything. I was braced for all the things that I’ve been told about low mood, low libido, everything else. But I haven’t really noticed anything. My libido is clearly lower, but it was super high [when I was on steroids], so I think this is just physiological now. [P13]

I came off for about 8 months, about two years ago. I was going through a divorce and at the time I wasn’t focused on training. It was quite difficult to initially coming off. It feels a bit like a car crash, mentally and physically. [P16]

Unplanned, sudden interruptions were more commonly associated with severe withdrawal symptoms.

It comes to a point in life where you realize that you’re never going to pay your mortgage or feed your family through lifting weights. (…) I think you reach a point where you grow up. You start a family, or you maybe start a serious relationship, or you start to take on more commitments at work. (…) So, I dropped my dosage and some of the stronger compounds. I probably did that for about two or three months, and then I had my heart attack. (…) I had no choice but to stop, cold turkey. It was an absolutely horrific phase of depression, anxiety, and many suicidal thoughts and ideations (…) [P08].

Discussion

We characterised the strategies adopted by a cohort of people using anabolic steroids in the UK to manage risks associated with the use of these drugs. We observed that their history of anabolic steroid use was linked to the process of learning, developing, adopting and changing risk-management strategies.

Most participants considered that start using anabolic steroids in an early age and/or with little experience in strength-training would increase the risk of adverse effects, a perception supported by available evidence. Younger people seem more likely to use higher doses of anabolic steroids and other IPEDs in attempts to accelerate the achievement of body-enhancement goals [38–41]. Those users are also prone to consume alcohol and other recreational drugs whilst using anabolic steroids [42] and less willing to engage with health professionals in case of adverse effects [10]. This profile of poor risk management aligns with the YOLO (an acronym for ‘you-only-live-once’) type of anabolic steroids’ user, characterised by a carefree attitude towards the drugs [43]. Although knowledge about the long-term consequences of early anabolic steroid use is limited, it is reasonable to assume that many young users will reach their 30s and 40s after several years of exposure to the drugs. This may likely result in the early onset of conditions commonly observed in long-term users, such as dyslipidaemia, hypertension, erectile dysfunction, and cognitive impairment [3, 44, 45]. Regarding the lack of experience with strength training, a premature use of anabolic steroids might increase the risk of injuries on tendons and muscle ligaments suddenly required to support the workload of drug-enhanced muscles [46–48].

Our sample contained many older and experienced male anabolic steroid users– 9 out of 20 participants were between 40 and 58 years of age; 10 out of 20 used the drugs for 10 years or more– whose perspectives aligned with those described in previous studies [49, 50]. An increasing number of men appear willing to use anabolic steroids to maintain their physical prowess and perceived attractiveness into their later years, and if possible, throughout their entire lives. This finding underscores the necessity of further studies exploring the needs and vulnerabilities of this population, as it might lead to significant impacts on the health system.

Participants’ main sources of knowledge about anabolic steroids were friends and online resources, as previously reported [51–54]. Effective information gathering– e.g., finding knowledgeable sources, spotting harmful or unsuitable information, interpreting scientific studies– was described as an important risk-management strategy, whose mastery differentiates novice and experienced users. The interviewees emphasized the challenges of navigating the vast array of digital content related to anabolic steroids [51, 55–57]. They noted that some of the doses and training routines shared by high-profiled bodybuilders– who are more likely to appear in searches and feeds– can be inappropriate for beginners and those less equipped to discern harmful information. Our findings illustrate the perceived benefits and challenges– anonymity, trans-regional data sharing, non-judgmental environments, and varying levels of reliability– found in forums, social media platforms and video channels [51, 58]. Nowadays, steroid coaches represent a professionalisation of those emic networks of harm-reduction [59]. The coaches’ personal experiences with anabolic steroids, as well as their own enhanced physiques [60] grant them access to clients who tend to distrust the advice of those lacking first-hand experience with the drugs [61]. Additionally, the popularity of private laboratories and TRT clinics reflects an increased presence of private healthcare providers filling the gap created by the precarious support for people using anabolic steroids in the public-health sector [62]. TRT clinics and the majority of anabolic steroids-related services and online content, however, are aimed at male users. As observed in previous studies [63–65], male-dominated environments of peer-support frequently display stereotyped and misogynistic perceptions of female anabolic steroid users, where topics related to female-specific health concerns are rarely discussed. The reliance of a female participant of this study on a few ‘women-only’ platforms exemplified the scarcity of tailored resources for that sub-population [66, 67] [63–65].

A dichotomy was observed between participants who followed traditional ‘cycling’ routines and those who opted for ‘blasting-and-cruising’, also described as ‘being on TRT maintenance with cycles of higher doses’. Those cycling highlighted the advantages of having a period of anabolic steroid abstinence between cycles– the ‘off-cycle’, frequently associated with PCT– to recover the natural production of testosterone. Participants on continuous exposure to the drugs underscored the benefits of not experiencing withdrawal symptoms or loss of muscle mass. They tend to downplay deleterious consequences of uninterrupted use of these drugs, using risk-management strategies to prevent and control adverse effects for as long as possible. A study following 100 male anabolic steroid users suggests a risk of permanent harm to males’ reproductive system following the prolonged use of anabolic steroids, regardless of PCT, doses and recovery periods [68]. Whilst the majority of those users had their endogenous testosterone production returning to baseline levels, significant percentages still experienced low testosterone concentrations (11%) and reduced sperm counts (34%) one year after completing a cycle of anabolic steroids [2, 68]. Further studies are needed to understand the long-term risks of different routines of anabolic steroid use, namely the uninterrupted exposure to the drugs.

Many interviewees mentioned the strategy of seeking the ‘minimal effective dose’ [61] of anabolic steroids required to achieve their body-enhancement goals. Ecological studies, however, reported a lack of association between the doses employed by different users and the prevalence of adverse effects [2, 69], suggesting the absence of a risk-free threshold. Therefore, individual attempts to find a ‘less harmful dose’ are tailored via trial-and-error [11, 70].

All participants of this study considered adequate health-monitoring to be an important risk-management strategy. Their experiences with health professionals from the public sector, however, were mostly negative, echoing reports of stigmatising behaviour towards people using anabolic steroids [71–75]. Many interviewees adhered to a ‘code of silence’ [76] to avoid stigma and potential repercussions of drug use on their private health insurances. Given estimates suggesting up to nearly one million male anabolic steroid users in the UK [77] and the concealment of steroid use from healthcare professionals, it is concerning that the true prevalence of health conditions potentially linked to these substances remains unknown.

None of the participants reduced or stopped the use of anabolic steroids when their interactions with health professional were unsuccessful [59, 78], suggesting that refusing to manage health conditions associated with the use of anabolic steroids is an ineffective deterrent to drug use. Health professionals have described ethical and technical dilemmas in their interaction with anabolic steroid users, as they struggle to keep their patients engaged whilst advising against the use of potentially harmful drugs [12, 79, 80]. However, the UK’s Good Medical Practice guidelines preclude doctors from refusing to investigate and treat health conditions associated with their patients’ lifestyles [81]. Doctors working in the public sector should be encouraged to develop greater knowledge of harm-reduction strategies related to anabolic steroid use, as users without access to private healthcare are presumably at greater risk of inadequate health management. Examples of positive interactions with health professionals in this study corroborate findings from interventions in the Netherlands [2] and Australia [82] where doctors providing harm-reduction for people using anabolic steroids were able to identify and treat adverse effects, helping users to reduce or stop the use of these drugs.

The participants’ lack of engagement with needle exchange services echoed the accounts from previous reports [11, 83], illustrating their fear of being seen as injectable drug users and instead buying their own injection equipment. The stigma associated with injectable drug use [84] as and the peculiarities of anabolic steroid use– potentially requiring a high number of daily intramuscular injections with specific needles– drives this population further away from the monitoring and safe-injection advise of the NSP. Although most participants from this and other studies affirm that is rare for anabolic steroid users to share needles [83, 85] evidence has shown a higher prevalence of blood-borne viruses amongst injectable anabolic steroid users [86, 87]. The fact that none of our participants used the NSP probably represents a recruitment bias, but also exemplifies a sub-population of injectable drug users potentially overlooked by NSP-based studies and interventions [88, 89].

Bloodletting– and invasive procedure based on intravenous access followed by the disposal of human blood, an infectious waste– seems to be an increasingly common practice amongst people using anabolic steroids [78, 90], although its prevalence in the UK remains unknown. As seen in this study, it represents an additional business venue for health professionals illicitly profiting from the gaps in public healthcare [62]. Perhaps even more worrisome is the practice of donating blood with the purpose of managing drug-induced polycythaemia. People using anabolic steroids are not eligible for blood donation due to the risk of coagulation disorders in the recipient and the potential exposure of hormone-sensitive individuals — such as pregnant people, foetuses, and children — to synthetic androgens [91], and future interventions should investigate the impacts of this practice.

The risk-management strategies described in this study were used to outline a model of continuous risk-management [9] adopted by people using anabolic steroids (Fig. 1). The model is based on a cycle of strategies adopted to identify, prevent, and control risks and harms. Naturally, not using anabolic steroids is the most effective strategy to prevent harms associated with the use of these drugs. Therefore, individuals considering the use of anabolic steroids often go through a more or less conscious period of self-assessment, during which they evaluate their health, motivations, strength training experience, and the pros and cons of starting using these drugs [19, 92]. This is an important moment of change [93], during which cultural influences, friends, and health professionals can impact the risk-assessment of potential users either way.

Fig. 1.

Risk-management strategies. 1: People must report history of anabolic steroid use before donating blood. Providing false or misleading health information is a crime in the UK [95]. 2: There is limited evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of different protocols of post-cycle therapy

Once a decision to try anabolic steroids is made, users might deploy strategies to prevent, identify and treat adverse effects, whilst trying to maximise the perceived benefits of the drugs. Naturally, this decision-making process may lead to increased risk exposure — for example, by deciding to use higher doses before strength-sport competitions, ignoring adverse symptoms, or choosing not to seek treatment for health conditions.

The top section of Fig. 1 illustrates the process of information gathering and self-assessment undertaken by potential users when considering the use of anabolic steroids. The lower half of the figure represents the cycle of identification, prevention and control or risks and harms associated with the use of the drugs. Strategies adopted in response to adverse events– such as undergoing diagnostic blood tests– can become part of users’ preventive approaches, such as routinely monitoring their health through regular examinations. These strategies often evolve over time, adapting to users’ circumstances, past events, and their own experiences with the drugs, reflecting the dynamic risk environment of anabolic steroid use [94]. The lower box in the middle represents the moments of change, i.e., events that could trigger the adoption of risk-management strategies– exemplified in this study by the user’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic– including a re-evaluation of peoples’ use of anabolic steroids.

This approach highlights the importance of addressing the use of anabolic steroids under a biopsychosocial approach [96], in which risks associated with physical, mental health and social vulnerabilities are taken into account. It also underscores the resiliency and agency of users and their communities of practice [21, 38], recognising their strategies as sources of insight for health professionals and policy makers engaged with people using anabolic steroids. Recent interventions [52, 97] demonstrate that people who use anabolic steroids are more likely to engage with non-judgmental, knowledgeable professionals who can identify periods of greater openness to promote positive changes in health-related behaviour– improving harm reduction outcomes and, sometimes, leading to the cessation of anabolic steroid use.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include potential recruitment bias, as individuals willing to discuss risk-management strategies may be more health-conscious regarding their use of anabolic steroids. The absence of more women in the sample underscores the need for further research into the behaviours of female users. The safety and efficacy of the strategies described by participants fall outside the scope of this study, and their practices should not be interpreted as safer methods for using anabolic steroids. Additional research is needed to determine an age threshold for the least harmful use of anabolic steroids, as well as to establish appropriate types and frequencies of medical examinations for monitoring the health of users. Future studies should investigate the risk-managing strategies of anabolic steroid users from other risk environments, and with access to different healthcare systems. As an in-depth qualitative study with a small sample size, these findings are not representative of the broader population of anabolic steroid users.

Conclusion

We characterised the risk-management strategies adopted by a cohort of anabolic steroid users living in the UK. These strategies were summarised as a continuous process of identification, prevention, and control of risks and harms. Risk-management strategies are commonly triggered by adverse circumstances and can be incorporated into preventative routines. Our findings can support studies investigating the efficacy of risk-management strategies, potentially leading to lower risk exposure and improving the outcomes of harm-reduction efforts.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of this study for their time and willingness to share their experiences. We thank Mr Tony Barnbroock for kindly allowing the use of his image in the advertisement of this study, and the reviewers of Harm Reduction Journal for their valuable observations, which helped improve this article.

Abbreviations

- GP

General practitioner

- NSP

Needle and syringe programme

- IPED

Image and performance enhancement drugs

- PCT

Post-cycle therapy

- TRT

Testosterone replacement therapy

Author contributions

JMXA was responsible for the study design, prepared the first draft of the analysis and made necessary adjustments suggested by the reviewers during the submission process.AK reviewed the data analysis and formal analysis.AK and PD provided critical comments on the final draft. All of the authors approved the final version submitted for publication.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from King’s College London Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee (Reference HR-20/21-22034). Participants’ consent was warranted prior to the interviews.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nieschlag E, Vorona E. Medical consequences of doping with anabolic androgenic steroids: effects on reproductive functions. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(2):R47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smit D, Buijs M, de Hon O, den Heijer M, de Ronde W. Positive and negative side effects of androgen abuse. The HAARLEM study: A one-year prospective cohort study in 100 men. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31(2):427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCullough D, Webb R, Enright KJ, Lane KE, McVeigh J, Stewart CE, et al. How the love of muscle can break a heart: impact of anabolic androgenic steroids on skeletal muscle hypertrophy, metabolic and cardiovascular health. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22(2):389–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’andrea A, Radmilovic · Juri, Caselli S, Carbone A, Scarafile R, Sperlongano S et al. Left atrial myocardial dysfunction after chronic abuse of anabolic androgenic steroids: a speckle tracking echocardiography analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34:1549–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Scarth M, Havnes I, Marie L, Mcveigh J, Van Hout M, Westlye LT, et al. Severity of anabolic steroid dependence, executive function, and personality traits in substance use disorder patients in Norway. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberlander JG, Henderson LP. The sturm und Drang of anabolic steroid use: angst, anxiety, and aggression. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35(6):382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chegeni R, Notelaers G, Pallesen S, Sagoe D. Aggression and psychological distress in male and female Anabolic-Androgenic steroid users: A multigroup latent class analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12(June):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Ronde W, Smit DL. Anabolic androgenic steroid abuse in young males. Endocr Connect. 2020;9(4):R102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolke T. Risk management. Walter de Gruyter GmbH; 2017.

- 10.Zahnow R, Mcveigh J, Ferris J, Winstock A. Adverse effects, health service engagement, and service satisfaction among anabolic androgenic steroid users. Contemp Drug Probl. 2017;44(1):69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey O, Keen S, Parrish M, van Teijlingen E. Support for people who use anabolic androgenic steroids: a systematic scoping review into what they want and what they access. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amaral J, Kimergård A, Deluca P. Prevalence of anabolic steroid users seeking support from physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e056445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strang J. Drug use and harm reduction: responding to the challenge. In: Heather N, Wodak A, Nadelman E, O’Hare P, editors. Psychoactive drugs & harm reduction: from faith to science. London: Whurr; 1992. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manning P. In: Manning P, editor. Drugs and popular culture. Willan Publishing; 2007. pp 115–117.

- 15.Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E, Drainoni M, lynn, Edeza A, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in healthcare settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;198:80–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-Calderón F, Díaz-Batanero C, Barratt MJ, Palamar J. Harm reduction strategies related to dosing and their relation to harms among festival attendees who use multiple drugs. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019;38:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soussan C, Kjellgren A. Harm reduction and knowledge exchange-a qualitative analysis of drug-related internet discussion forums. Harm Reduct J. 2014;11(25):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreasson J, Johansson T. Online doping. The new self-help culture of ethnopharmacology. Sport Soc. 2016;19(7):957–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen J, Collins R, Darkes J, Gwartney D. A league of their own: demographics, motivations and patterns of use of 1,955 male adult non-medical anabolic steroid users in the united States. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2007;4(12):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piatkowski TM, Obst PL, White KM, Hides L. The relationship between psychosocial variables and drive for muscularity among male bodybuilding supplement users. Aust Psychol. 2022;57(2):148–59. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Underwood MMR. 2021 [cited 2023 Mar 14]. ‘Bro, do you even science?’: The increased emphasis on science in bodybuilding, and how it can improve steroid harm reduction. Available from: https://thinksteroids.com/articles/science-in-bodybuilding-and-how-it-can-improve-steroid-harm-reduction/

- 22.Amaral J, Kimergård A, Deluca P. Preventing and treating the adverse health conditions of androgenic-anabolic steroids: an online survey with 883 users in the united Kingdom. Perform Enhanc Health. 2023;11(September):100267. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neale J, Allen D, Coombes L. Qualitative research methods within the addictions. Addiction. 2005;100:1584–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative research: reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health Ans health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(42):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Vol. 27, Qualitative Health Research. SAGE Publications Inc.; 2017. pp. 591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Gilburt H, Drummond C, Sinclair J. Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: A qualitative study from the service users’ perspective. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(4):444–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimergård A, Parkin S, Jennings S, Brobbin E, Deluca P. Identification of factors influencing tampering of codeine-containing medicines in england: A qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch E, McGovern R, Elzerbi C, Breckons M, Deluca P, Drummond C, et al. Adolescent perspectives about their participation in alcohol intervention research in emergency care: A qualitative exploration using ethical principles as an analytical framework. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(6):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neale J, Parkman T, Day E, Drummond C. Socio-demographic characteristics and stereotyping of people who frequently attend accident and emergency departments for alcohol-related reasons: qualitative study. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2017;24(1):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parkin S, Neale J, Brown C, Jones JD, Brandt L, Castillo F, et al. A qualitative study of repeat Naloxone administrations during opioid overdose intervention by people who use opioids in new York City. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;87:102968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts E, Hillyard M, Hotopf M, Parkin S, Drummond C. Access to specialist community alcohol treatment in england, and the relationship with alcohol-related hospital admissions: qualitative study of service users, service providers and service commissioners. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(5):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahimi S, Khatooni M. Saturation in qualitative research: an evolutionary concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2024;6(100174). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burges R, editors. Analyzing qualitative data. 1994. pp. 173–94.

- 34.Neale J. Iterative categorization (IC): A systematic technique for analysing qualitative data. Addiction. 2016;111(6):1096–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neale J. Iterative categorisation (IC) (part 2): interpreting qualitative data. Addiction. 2021;116(3):668–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sagoe D, Mcveigh J, Bjørnebekk A, Essilfie M, stella, Andreassen CS. Polypharmacy among anabolic-androgenic steroid users: a descriptive metasynthesis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10(12):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christou MA, Christou PA, Markozannes G, Tsatsoulis A, Mastorakos G, Tigas S. Effects of anabolic androgenic steroids on the reproductive system of athletes and recreational users: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(9):1869–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macho J, Mudrak J, Slepicka P. Enhancing the self: amateur bodybuilders making sense of experiences with appearance and performance-enhancing drugs. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McVeigh J, Salinas M, Ralphs R. A Sentinel population: the public health benefits of monitoring enhanced body builders. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;95(xxxx):102890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monaghan L. Vocabularies of motive for illicit steroid use among bodybuilders. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(5):695–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Underwood M, Olivardia R. ‘The day you start lifting is the day you become forever small’: bodybuilders explain muscle dysmorphia. Health 2023 Nov;27(6):998–1018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Zahnow R, McVeigh J, Bates G, Hope V, Kean J, Campbell J, et al. Identifying a typology of men who use anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS). Int J Drug Policy. 2018;55:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christiansen A, Vinther AS, Liokaftos D. Outline of a typology of men’s use of anabolic androgenic steroids in fitness and strength training environments. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2017;24(3):295–305. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindqvist Bagge AS, Rosén T, Fahlke C, Ehrnborg C, Eriksson BO, Moberg T, et al. Somatic effects of AAS abuse: A 30-years follow-up study of male former power sports athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:814–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bjørnebekk A, Kaufmann T, Hauger LE, Klonteig S, Hullstein IR, Westlye LT. Long-term anabolic–androgenic steroid use is associated with deviant brain aging. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;6(5):579–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanayama G, DeLuca J, Meehan W III, Husdon J, Isaacs S, Baggish A, et al. Ruptured tendons in anabolic-androgenic steroid users: A cross-sectional cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2017;43(11):2638–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horn S, Gregory P, Guskiewicz KM. Self-reported anabolic-androgenic steroids use and musculoskeletal injuries: findings from the center for the study of retired athletes health survey of retired NFL players. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(3):192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones IA, Togashi R, Rick GF, Iii H, Weber AE, Thomas C. Anabolic steroids and tendons: A review of their mechanical, structural, and biologic effects. J Orthop Res. 2018;36:2830–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hearne E, Atkinson A, Boardley I, Mcveigh J, Van Hout MC. Sustaining masculinity: a scoping review of anabolic androgenic steroid use by older males. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2024 Jan 2;31(1):27–53.

- 50.Ip EJ, Trinh K, Tenerowicz MJ, Pal J, Lindfelt TA, Perry PJ. Characteristics and behaviors of older male anabolic steroid users. J Pharm Pract. 2015;28(5):450–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tighe B, Dunn M, McKay FH, Piatkowski T. Information sought, information shared: exploring performance and image enhancing drug user-facilitated harm reduction information in online forums. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Havnes IA, Jørstad ML, Wisløff C. Anabolic-androgenic steroid users receiving health-related information; health problems, motivations to quit and treatment desires. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morahan-Martin J. How internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: A cross-cultural review. CyberPsychology Behav. 2004;7(5):497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rowe R, Berger I, Copeland J. No pain, no gainz? Performance and image- enhancing drugs, health effects and information seeking. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2017;24(5):400–8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griffiths S, Murray SB, Krug I, McLean SA. The contribution of social media to body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms, and anabolic steroid use among sexual minority men. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21(3):149–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boursier V, Gioia F, Griffiths MD. Objectified body consciousness, body image control in photos, and problematic social networking: the role of appearance control beliefs. Front Psychol. 2020;11(February):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van de Ven K, Mulrooney KJD. Social suppliers: exploring the cultural contours of the performance and image enhancing drug (PIED) market among bodybuilders in the Netherlands and Belgium. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;40:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cox L, Gibbs N, Turnock LA. Emerging anabolic androgenic steroid markets; the prominence of social media. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2024;31(2):257–70. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gibbs N, Cox L, Turnock L. Anabolics coaching: emic harm reduction or a public health concern? Perform Enhanc Health. 2022;10:100227. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hutson DJ. Your body is your business card: Bodily capital and health authority in the fitness industry. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2013;90:63–71. Available from: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Piatkowski T, Cox L, Gibbs N, Turnock L, Dunn M. The general concept is a safer use approach’: how image and performance enhancing drug coaches negotiate safety through community care. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turnock L, Gibbs N, Cox L, Piatkowski T. Big business: The private sector market for image and performance enhancing drug harm reduction in the UK. International Journal of Drug Policy [Internet]. 2023;122(November):104254. Available from: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104254 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Henning A, Andreasson J. Yay, another lady starting a log! Women’s fitness doping and the gendered space of an online doping forum. Communication Sport. 2021;9(6):988–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andreasson J, Henning A. Challenging hegemony through narrative: centering women’s experiences and Establishing a sis-science culture through a women-only doping forum. Communication Sport. 2022;10(4):708–29. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sverkersson E, Andreasson J, Henning A. Women’s risk assessments and the gendering of online IPED cultures and communities. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2024;31(4):422–30. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ainsworth N, Thrower N, Petróczi S. Fragile femininity, embodiment, and self-managing harm: an interpretative phenomenological study exploring the lived experience of females who use anabolic-androgenic steroids. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2022;14(3):363–81. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piatkowski T, Robertson J, Lamon S, Dunn M. Gendered perspectives on women’s anabolic–androgenic steroid (AAS) usage practices. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smit D, Buijs M, De Hon O, Den Heijer M, De Ronde W. Disruption and recovery of testicular function during and after androgen abuse: the HAARLEM study. Hum Reprod. 2021;36(4):880–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amaral J, Deslandes AC, Padilha MC, Vieira Neto L, Osorio LE, Aquino Neto FR et al. No association between psychiatric symptoms and doses of anabolic steroids in a cohort of male and female bodybuilders. Drug Test Anal. 2022Jun;14(6):1079–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Christian H, Henriksen B, Havnes IA, Jørstad ML, Bjørnebekk A. Health service engagement, side effects and concerns among men with anabolic- androgenic steroid use: a cross-sectional Norwegian study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2023;18(19):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hill SA, Waring WS. Pharmacological effects and safety monitoring of anabolic androgenic steroid use: differing perceptions between users and healthcare professionals. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2019;10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jacka B, Larance B, Copeland J, Burns L, Farrell M, Jackson E. Health care engagement behaviors of men who use performance- and image-enhancing drugs in Australia. Subst Abus. 2020 Jan;41(1):139–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Dunn M, Henshaw R, McKay FH. Do performance and image enhancing drug users in regional Queensland experience difficulty accessing health services? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35(4):377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McVeigh J, Bates G. Stigma and the use of anabolic androgenic steroids by men in the united Kingdom. In: Addison M, McGovern W, McGovern R, editors. Drugs, identity and stigma. Palgrave Macmilan Cham; 2022. pp. 121–46.

- 75.Fink J, Schoenfeld BJ, Hackney AC, Matsumoto M, Maekawa T, Nakazato K, et al. Anabolic-androgenic steroids: procurement and administration practices of doping athletes. Phys Sports Med. 2019;47(1):10–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richardson A, Antonopoulos GA. Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) users on AAS use: Negative effects, ‘code of silence’, and implications for forensic and medical professionals. J Forensic Leg Med [Internet]. 2019;68(July):101871. Available from: 10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101871 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Hope V, Walker Bond V, Boardley I, Smith J, Campbell J, Bates G, et al. Anabolic androgenic steroid use population size estimation: a first stage study utilising a Delphi exercise. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2022;13:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Turnock L, Gibbs N, Cox L, Piatkowski T. Big business: the private sector market for image and performance enhancing drug harm reduction in the UK. Int J Drug Policy. 2023;122(November):104254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dawson R. Drugs in sport– the role of the physician. J Endocrinol. 2001;170:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dunn M, Piatkowski T, Whiteside B, Eu B. Exploring the experiences of general practitioners working with patients who use performance and image enhancing drugs. Perform Enhanc Health. 2023;11(2):100247. [Google Scholar]

- 81.GMC. Good medical practice [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2023 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice---english-20200128_pdf-51527435.pdf

- 82.Eu B, Dawe J, Dunn M, Lee K, Griffiths S, Bloch M, et al. Impact of harm reduction practice on the use of non-prescribed performance and image-enhancing drugs: the PUSH! Audit. Aust J Gen Pract. 2023;52(4):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kimergård A, Mcveigh J. Variability and dilemmas in harm reduction for anabolic steroid users in the UK: A multi-area interview study. Harm Reduct J. 2014;11(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Simmonds L, Coomber R. Injecting drug users: A stigmatised and stigmatising population. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(2):121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kimergård A, McVeigh J. Environments, risk and health harms: a qualitative investigation into the illicit use of anabolic steroids among people using harm reduction services in the UK. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hope V, McVeigh J, Marongiu A, Evans-Brown M, Smith J, Kimergård A, et al. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, HIV, hepatitis B and C infections among men who inject image and performance enhancing drugs: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hope V, Mcveigh J, Marongiu A, Evans-Brown M, Smith J, Kimergård A, et al. Injection site infections and injuries in men who inject image- and performance-enhancing drugs: prevalence, risks factors, and healthcare seeking. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(1):132–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bates G, Mcveigh J, Leavey C. Looking beyond the provision of injecting equipment to people who use anabolic androgenic steroids: harm reduction and behavior change goals for UK policy. Contemp Drug Probl. 2021;48(2):135–50. [Google Scholar]

- 89.van de Ven K, Zahnow R, McVeigh J, Winstock A. The modes of administration of anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) users: are non-injecting people who use steroids overlooked? Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2020;27(2):131–5. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brennan R, Wells J, Van Hout MC. Blood letting—Self-phlebotomy in injecting anabolic-androgenic steroids within performance and image enhancing drug (PIED) culture. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;55(February):47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Give NHS. Blood. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Who can give blood. Available from: https://www.blood.co.uk/who-can-give-blood/

- 92.Grogan S, Shepherd S, Evans R, Wright S, Hunter G. Experiences of anabolic steroid use: In-depth interviews with men and women body builders. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(6):845–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thompson S, Michaelson J, Abdallah S, Johnson V, Morris D, Riley K et al. ‘Moments of change’ as opportunities for influencing behaviour: A report to the department for environment, food and rural affairs. New Econ Foundation. 2011.

- 94.Bates G, Tod D, Leavey C, Mcveigh J. An evidence-based socioecological framework to understand men’s use of anabolic androgenic steroids and inform interventions in this area. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2019;26(6):484–92. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Department of Health. False or misleading information: Issued under the Care Act 2014 [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/notes/division/5/2/5#:~:text=This section creates a new,provider as a corporate body.

- 96.Mullen C, Whalley BJ, Schifano F, Baker JS. Anabolic androgenic steroid abuse in the united kingdom: an update. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(10):2180–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Campbell JASUK, Conference. 2020. 2020 [cited 2022 Jul 15]. The Glasgow experience. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRGCbiyPNSQ

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.