Abstract

Objectives

To compare the suitability of the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) and the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) among Chinese college students, and to further validate the SPEED questionnaire by using the OSDI in a non-clinical sample.

Methods

This cross-sectional study involved 1,084 students from Nanyang Medical College, aged 18 to 21 years. The students completed the OSDI and SPEED questionnaires to assess dry eye symptoms. The correlation between the scores of the two questionnaires was analyzed to assess criterion validity. Based on the OSDI scores, a receiver operating characteristic curve was constructed to determine the area under the ROC curve and the cut-off point for evaluating the diagnostic threshold of the SPEED questionnaire.

Results

The Cronbach’s alpha values for the OSDI and SPEED questionnaires were 0.943 and 0.911, respectively. Notably, only 281 participants (25.92%) completed all 12 questions in the OSDI questionnaire, whereas all participants completed the SPEED questionnaire without omitting any questions. The mean SPEED scores Full were 3.71, 11.57, 13.84, and 19.72 for each subgroup. Posthoc testing revealed statistically significant differences between all groups (P < 0.05). A significant correlation was observed between the OSDI score, the SPEED score, and the SPEED score Full, particularly between the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full.

Conclusion

In comparison to the OSDI questionnaire, the SPEED questionnaire demonstrates a favorable response rate, reliability, and validity in differentiating dry eye symptoms among Chinese college students. It may be more appropriate for diagnosing dry eye and conducting epidemiological studies within this population.

Keywords: Dry eye disease, Standard patient evaluation of eye dryness, Ocular surface disease index, Correlation analysis, Suitability

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is one of the most prevalent and chronic ocular conditions globally, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 5–50% [1]. DED frequently results in ocular discomfort, which can manifest as blurred vision, dryness, grittiness, and ocular fatigue [2]. College students, in particular, are especially vulnerable to DED due to factors such as prolonged use of mobile phones and computers, contact lens wear, and late-night activities [3]. Despite experiencing symptoms of dry eye, many college students do not seek medical attention. As a chronic and progressive condition, DED presents considerable challenges to the academic and daily lives of college students, while also exacerbating the economic burden related to medical expenses and diminished productivity if not addressed therapeutically in a timely manner [4]. The evaluation of subjective dry eye symptoms is essential for the diagnosis of DED. Therefore, the identification of a reliable, valid, and easily comprehensible dry eye questionnaire for detecting DED in college students is of growing importance.

The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire, recognized as the most frequently used standardized assessment for dry eye, is consistently regarded as a valid and reliable tool for evaluating the severity of dry eye disease. However, it only measures the frequency of dry eye symptoms. In contrast, the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) questionnaire is a short and intuitive questionnaire that quantifies both severity and frequency of dry eye symptoms. It found that the SPEED questionnaire performs comparably to the OSDI questionnaire in distinguishing between asymptomatic and symptomatic participants within a nonclinical sample in Ghana and Pakistan [5, 6]. Given the differences in Eastern and Western cultures and social backgrounds, the reliability and validity of the SPEED questionnaire among Chinese college students remains uncertain.

The main objective of this study was to compare the SPEED and OSDI questionnaires in Chinese college students. Furthermore, we sought to expand on evidence in support of the use of the SPEED questionnaire for DED diagnosis, epidemiological investigation and follow-up in China.

Methods

Participants and samples

In October 2023, ten classes of freshmen at Nanyang Medical College were selected through random cluster sampling. Students who were using eye drops, had eye diseases or systemic diseases, or had a history of any ocular surgery were excluded from the study. All students in these classes were surveyed based on the principle of voluntary participation, and each provided verbal informed consent.

OSDI and SPEED questionnaires

Referring to published literature, SPEED and OSDI questionnaires were used to evaluate DED in this study [7, 8]. The Chinese version of the OSDI is a well-validated symptom assessment tool for dry eye disease. Existing studies have demonstrated its robust internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.89 to 0.925, as well as high test-retest reliability (ICC: 0.91–0.99) [9, 10]. Similarly, the Chinese adaptation of the SPEED questionnaire serves as another widely utilized instrument for evaluating subjective dry eye symptoms [11–13]. Zhang et al. found that the web-based OSDI questionnaire in Chinese was reliable for assessing DED and showed a correlation with the paper-based version [14]. To enhance the efficiency of data collection, the OSDI questionnaire and the SPEED questionnaire in Chinese were administered online using the Questionnaire Star platform (https://www.wjx.cn/), allowing students to scan and complete the questionnaire.

The OSDI questionnaire consists of 12 questions divided into three parts: ocular symptoms, vision-related function, and environmental triggers. It can rapidly assess dry eye symptoms experienced over the past week. Responses are measured on a four-point Likert scale (0 = none of the time, 1 = some of the time, 2 = half of the time, 3 = most of the time, 4 = always). The formula for calculating the total OSDI score is: OSDI = (total score of OSDI × 25)/(total number of questions). The total OSDI score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Individuals with an OSDI score of 13 or higher are considered to exhibit positive symptoms for a diagnosis of DED. Based on the score, individuals’ dry eye symptoms can be classified as normal (< 13), mild dry eye (13–22), moderate dry eye (23–32), or severe dry eye (> 32) [5].The SPEED questionnaire consists of eight questions divided into two parts: frequency and severity of dry eye symptoms. The dry eye symptoms include dryness, grittiness or scratchiness; soreness or irritation; burning or watering; and eye fatigue. Each frequency question is graded on a scale from 0 to 4 (0 = none of the time, 1 = some of the time, 2 = often, 3 = constant), while each severity question is also graded from 0 to 4 (0 = no problem, 1 = tolerable, 2 = uncomfortable, 3 = bothersome, 4 = intolerable). The SPEED score can range from 0 to 28. Additionally, the SPEED questionnaire can track changes in dry eye symptoms occurring during the following time frames: at this visit, within the past 72 hours, and within the past 3 months. Furthermore, responses to the 12 binary questions can be combined with the eight questions, resulting in what is referred to as the “SPEED score Full.’’ The maximum score for the SPEED score Full is 40 [15].

With the class serving as the unit of investigation, the same investigator was responsible for explaining the purpose, significance, and methodology of the survey prior to the administration of the questionnaires. Subsequently, students completed the questionnaires anonymously online after providing oral informed consent. To ensure the quality of the responses, each IP address was allowed to submit answers only once, and all questions had to be answered before submission.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 software (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). The reliability of the two questionnaires, including their respective subsections, was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which measures internal consistency. Discriminant validity was evaluated by analyzing significant differences in SPEED scores in relation to disease severity, as determined by the OSDI classification, through analysis of variance and the Tukey test for multiple comparisons. Correlation between the OSDI score, the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full were analyzed by Spearman’s correlation. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey posthoc test was employed to assess the discriminant validity of the SPEED questionnaire by examining significant differences in SPEED score and SPEED score Full across varying levels of dry eye symptom severity, as defined by the OSDI score. The predictive ability of the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full for diagnosing OSDI was analyzed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The optimal cutoff threshold was established at the point where Youden’s index was maximized (Youden’s index = sensitivity + specificity − 1). Agreements between questionnaires were determined with Cohen’s kappa coefficient and percentage agreements. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Out of the 1,200 individuals surveyed, 1,084 participated in the study, resulting in a response rate of 90.33%. The majority of participants (66.24%) were female. The overall mean scores of the OSDI score, the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full were 15.45 ± 12.55, 5.16 ± 4.59, and 8.64 ± 7.12, respectively. The age range of participants was 18 to 21 years, with a mean age of 19.04 ± 0.73 years. The study population comprised four distinct age cohorts with participant numbers of 270, 498, 252, and 64 respectively. For analytical purposes, subjects were categorized into two age groups: 18–19 years and 20–21 years. The OSDI score, SPEED score, and SPEED score Full of the 18–19 year-old group were 15.21 ± 11.82, 5.18 ± 4.53, and 8.61 ± 7.02, respectively. Comparatively, the 20–21 year-old group showed similar results, with respective scores of 16.02 ± 14.18, 5.16 ± 4.86, and 8.65 ± 7.32 for these measures. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the two age groups in any of the assessed parameters: OSDI scores (p = 0.336), SPEED scores (p = 0.939), or SPEED scores Full (p = 0.929).

The response rates and reliability of the two questionnaires

Only 281 (25.92%) participants completed all 12 questions in the OSDI questionnaire. The completion rates for the OSDI questionnaire were as follows: 254 (23.43%) participants completed 11 questions, 177 (16.33%) completed 10 questions, 150 (13.84%) completed 9 questions, 109 (10.06%) completed 8 questions, 68 (6.27%) completed 7 questions, and 45 (4.15%) completed 6 questions. The response rate for the first six questions of the OSDI questionnaire was 100%. In contrast, the response rates for questions 7 to 12 were 35.70%, 76.29%, 74.91%, 73.06%, 72.69%, and 73.62%, respectively. Notably, the question regarding “driving at night” was the most frequently skipped. In contrast, all participants completed the SPEED questionnaire without skipping any questions. However, no significant difference was observed in the mean OSDI scores between the 281 participants who completed all questions (16.82 ± 15.64) and the 803 participants who did not (15.16 ± 11.22) (t = 1.913, P = 0.056).

The reliability of the two questionnaires was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Notably, no item was negatively correlated with the total scores in either questionnaire, indicating that the internal consistencies of both instruments were excellent and that the items within each questionnaire were not redundant.

Analysis of the prevalence of DED

According to the OSDI score grading, 533 participants (49.17%) were asymptomatic, 315 participants (29.06%) exhibited mild dry eye symptoms, 158 participants (14.58%) had moderate dry eye symptoms, and 78 participants (7.19%) experienced severe dry eye symptoms. Mean scores for various severity categories and the results of the analysis of variance are presented in Table 1. As the severity of dry eye increases, the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full also rise progressively. All between-group comparisons of the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full (no dry eye, mild, moderate, and severe dry eye) were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Mean scores of the two questionnaires across dye eye severity

| Type of dry eye based on OSDI scores | Number (%) | OSDI score (Mean ± SD) | SPEED score (Mean ± SD) | SPEED score Full (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dye eye | 533 (49.17) | 6.05 ± 4.07 | 2.02 ± 2.20 | 3.71 ± 3.83 |

| Mild dry eye | 315 (29.06) | 18.15 ± 3.01 | 6.99 ± 3.58 | 11.57 ± 5.19 |

| Moderate dry eye | 158 (14.58) | 26.84 ± 2.40 | 8.70 ± 4.21 | 13.84 ± 5.81 |

| Severe dye eye | 78 (7.19) | 45.60 ± 14.99 | 12.26 ± 4.82 | 19.72 ± 6.79 |

| F | 1694.592 | 394.376 | 423.344 | |

| P | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

The correlation between the two questionnaires

The OSDI score is highly significantly correlated with the SPEED score (rs=0.778, P<0.001) as well as the SPEED score Full (rs=0.775, P<0.001). There is also a low significant correlation between the OSDI score and the SPEED score for the asymptomatic group, mild dry eye group, moderate dry eye group, and severe dry eye group (asymptomatic: rs=0.421, P<0.001; mild: rs=0.309, P<0.001; moderate: rs=0.319, P<0.001; severe: rs= 0.356, P<0.001). Notably, the correlation between the SPEED score and SPEED score Full is particularly strong, with rs>0.88 in each group. These findings are presented in Table 2 and illustrated in the scatter plots from Fig. 1.

Table 2.

The correlation between the OSDI and SPEED questionnaire scores in different groups

| Type of Dry Eye Based on OSDI Scores | OSDI Score vs. SPEED Score | OSDI Score vs. SPEED Score Full | SPEED Score vs. SPEED Score Full | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r s | P | r s | P | r s | P | |

| All participants | 0.778 | P<0.001 | 0.775 | P<0.001 | 0.957 | P<0.001 |

| Asymptomatic group | 0.421 | P<0.001 | 0.446 | P<0.001 | 0.920 | P<0.001 |

| Dry eye group | 0.453 | P<0.001 | 0.440 | P<0.001 | 0.904 | P<0.001 |

| Mild dry eye group | 0.309 | P<0.001 | 0.283 | P<0.001 | 0.898 | P<0.001 |

| Moderate dry eye group | 0.319 | P<0.001 | 0.308 | P<0.001 | 0.882 | P<0.001 |

| Severe dry eye group | 0.356 | 0.001 | 0.353 | 0.002 | 0.891 | P<0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot of correlation between OSDI and SPEED questionnaires. A-C The Scatter plot of correlation in all participants. D-F The Scatter plot of correlation in asymptomatic group. G-I The Scatter plot of correlation in mild dry eye group. J-L The Scatter plot of correlation in moderate dry eye group. M-O The Scatter plot of correlation in severe dry eye group

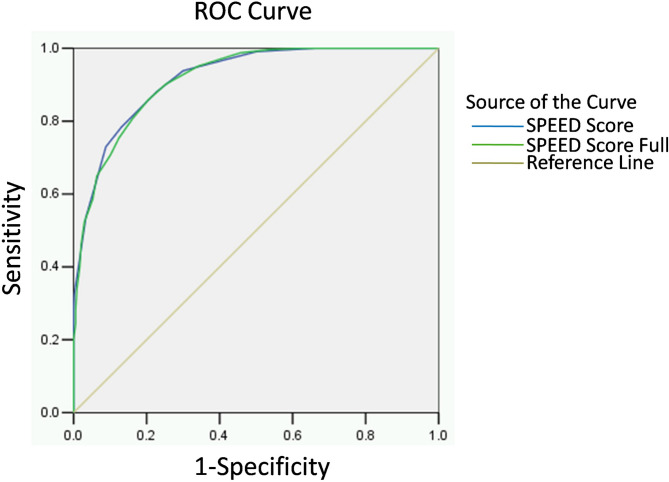

The diagnostic efficiency of the SPEED questionnaire

To evaluate the diagnostic predictive power, we conducted a ROC curve analysis for both the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full. The area under the curve (AUC) was found to be 0.919 and 0.917, respectively, indicating good sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing individuals with dry eye from healthy individuals (Fig. 2). The established diagnostic threshold for the SPEED score is set at 4, which provides a maximum sensitivity of 88.0% and a specificity of 77.3%. Furthermore, when the criteria of OSDI score of ≥ 13 points is applied in conjunction with a SPEED score of ≥ 4 points, the diagnostic results for 897 individuals (82.75%) were found to be consistent, yielding a Kappa coefficient of 0.654 (P<0.001). Using the same methodology, we determined that the diagnostic threshold for the SPEED score Full is 7, which yields a maximum sensitivity of 88.8% and a specificity of 79.5%. Additionally, when applying the criterion of an OSDI score of ≥ 13 points alongside a SPEED score Full of ≥ 7 points, the diagnostic results for 898 individuals (82.84%) were consistent, resulting in a Kappa coefficient of 0.656 (P<0.001).

Fig. 2.

ROC curves for diagnostic performance of SPEED questionnaire

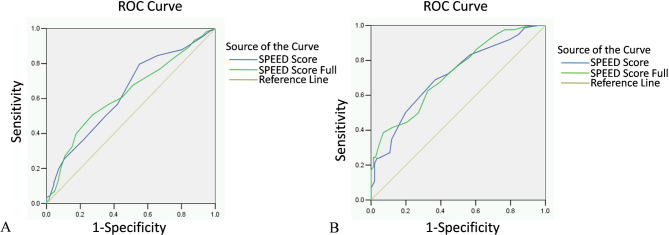

The previous results indicated that as the severity of dry eye symptoms increases, both the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full exhibited a gradual increase. We subsequently assessed the diagnostic efficiency of the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full in distinguishing between varying levels of dry eye severity. The detailed ROC curve, AUC, diagnostic threshold, Youden index, sensitivity, and specificity are presented in Fig. 3; Table 3.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves for predicting dry eye severity performance of SPEED questionnaire. A Prediction of the mild dry eye group and the moderate dry eye group. B Prediction of the moderate dry eye group and the severe dry eye group

Table 3.

The diagnostic threshold, Youden index, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full in predicting the severity of dry eye

| Mild-moderate DED | Moderate-severe DED | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPEED Score | SPEED score Full | SPEED Score | SPEED score Full | |

| Cutoff Score | 8 | 17 | 12 | 24 |

| Youden Index J | 0.247 | 0.290 | 0.321 | 0.316 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 79.7 | 44.9 | 68.9 | 38.6 |

| Specificity (%) | 45.0 | 84.1 | 63.2 | 99.3 |

| AUC (95%CI) | 0.631(0.617–0.646) | 0.625(0.610–0.640) | 0.711(0.694–0.728) | 0.725(0.709–0.741) |

| P | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

Discussion

Based on the OSDI scores, this study found that the prevalence of dry eye among college students is 50.83%. The traditional notion holds that advanced age is one of the most significant risk factors for DED. However, recent studies indicate a rising prevalence of DED among younger individuals [16]. For example, Wróbel-Dudzinska et al. utilized the OSDI questionnaire to survey 312 Polish university students, revealing that over half of the respondents (57.1%) exhibit symptoms of DED [17]. Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Ezinne et al. reported the prevalence of DED as high as 84.3% among students at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago [18]. Notably, more severe subjective symptoms were found in the younger DED individuals [16]. Therefore, it is essential to find a dry eye questionnaire that is simple, user-friendly, highly reliable, and valid for college students. This tool would facilitate early screening for dry eye, enhance awareness of eye health, and enable timely intervention measures.

The low response rates in the OSDI vision-related function section seem to be influenced by the sociocultural and lifestyle differences between China and the West may. For example, many Chinese college students typically do not drive, resulting in only 35.7% responding to the question regarding “driving at night.” Furthermore, the designated recall period of the past week may also affect responses, as factors such as season, climate, and weather can contribute to a certain non-response rate in the questionnaires concerning environmental triggers. The studies also observed similar phenomena [19, 20]. Previous research has confirmed that although the number of unanswered questions does not influence the total score, the purpose of the OSDI as a tool for assessing symptoms related to health-related quality of life is undermined when individuals leave a significant number of questions measuring these aspects unanswered [20]. This study indicates that whether all questionnaire items were completed had minimal impact on the results. However, the investigation was confined to healthy college students. Further research is needed to determine whether these findings can be generalized to broader populations.

The Cronbach alpha is commonly used to evaluate the internal consistency of questionnaires. A Cronbach alpha value exceeding 0.9 indicates excellent reliability [21]. The Cronbach’s alpha for the OSDI and SPEED questionnaires was found to be 0.943 and 0.911, respectively, which is slightly higher than the results reported by Nauman et al. and Kof et al. [15]. This discrepancy may be attributed to variations in the study populations. These findings suggest that both the OSDI and SPEED questionnaires exhibit good internal consistency.

A Spearman correlation coefficient ranging from 0.7 to 1.0 is considered to indicate a strong association, while a coefficient between 0.3 and 0.5 signifies a low association [22]. In this study, we found that the total scores of both questionnaires were strongly correlated, indicating a good concurrent validity. However, in the non-dry eye group, as well as in each subgroup of mild, moderate, and severe dry eye, there was a low positive correlation between the two questionnaires.

This finding aligns with the reported research results [5, 6]. This discrepancy may be attributed, in part, to the relatively small sample size in each subgroup. Additionally, there are inherent differences in the structure and content of the two questionnaires. The OSDI questionnaire exclusively measures the frequency of dry eye symptoms and their effects on the healthrelated quality of life, whereas the SPEED questionnaire evaluates both the frequency and intensity of dry eye symptoms. This suggests that the two questionnaires are not interchangeable, and the selection of the appropriate questionnaire should depend on the specific purpose for which it is being used. Notably, the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full exhibit a robust correlation in both the total score and each subgroup, with rs >0.88 in every group. In most SPEED questionnaire surveys, they only report the SPEED score. Therefore, it can be inferred that a high SPEED score in participants is likely to correspond with a high score on the SPEED score Full.

ROC curve analysis is widely utilized for the performance evaluation of diagnostic tests. AUC value exceeding 0.9 indicates high diagnostic accuracy [23]. In our study, the SPEED scores and the SPEED score Full demonstrated strong accuracy in detecting DED when compared to the OSDI score, with AUC values of 0.919 and 0.917, respectively. Furthermore, this study identified that cut-off scores of SPEED scores ≥ 4 and SPEED score Full ≥ 7 yielded the highest sum of specificity and sensitivity. We employed kappa to assess the concordance between the OSDI questionnaire and the SPEED questionnaire in distinguishing symptomatic from asymptomatic participants. A kappa value exceeding 0.6 was deemed indicative of good agreement [24]. Utilizing a SPEED score cutoff of 4, we obtained a kappa value of 0.654, with a percentage agreement of 82.75%. Conversely, applying a SPEED score Full cutoff of 7 yielded a kappa value of 0.656 and a percentage agreement of 82.84%. This indicates that the SPEED questionnaire is highly effective in differentiating between symptomatic and asymptomatic participants.

It was observed that both the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full increased with the severity of dry eye, as categorized by the OSDI. This association suggests that the SPEED questionnaire could also be utilized to assess the severity of dry eye symptoms, similar to the OSDI questionnaire. Subsequently, we employed the same method for verification. We found that the SPEED score achieved an AUC of 0.631 in distinguishing mild dry eye from moderate dry eye, and an AUC of 0.711 for differentiating moderate from severe dry eye. The corresponding cutoff values are 8 and 12, respectively. The criteria for this graded diagnosis differ slightly from those established by Graae et al. [25]. They determined the grading criteria of the SPEED score for diagnosing dry eye as follows: normal (< 4), mild (4-5.9), moderate (6-9.9), and severe (≥ 10). Graae’s study involved 218 elderly cataract patients in Norway [25], whereas our study focused on 1,084 young Chinese college students. So the differing cutoff values may be attributed to variations in patient demographics, including age and ethnicity. In our study, the grading criteria for the SPEED score Full were established as follows: normal (< 7), mild dry eye (7–16), moderate dry eye (17–23), and severe dry eye (≥ 24). It is important to note that the grading diagnostic criteria for the SPEED score Full have not yet been reported. The findings from this study can serve as a reference and foundation for future related research.

Nevertheless, several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the study population consisted exclusively of healthy college students rather than clinically diagnosed dry eye patients. Furthermore, while the reliability and validity of the SPEED questionnaires were assessed using the OSDI as a benchmark, the study did not examine the relationship between questionnaire scores and objective clinical signs of dry eye. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted cautiously due to potential information bias. Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable preliminary evidence supporting the use of symptom-based questionnaires for dry eye assessment in Chinese college students. Future research should address these gaps to establish more definitive conclusions.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrated that the SPEED questionnaire is comparable to the OSDI questionnaire in several aspects among Chinese college students, including strong reliability and validity. Additionally, it effectively enables graded diagnosis of dry eye severity, similar to the OSDI questionnaire. Notably, the response rate for the SPEED questionnaire was 100%, significantly higher than that of the OSDI questionnaire. Furthermore, the SPEED score and the SPEED score Full are highly positively correlated, indicating that either can be utilized for statistical analysis of the SPEED questionnaire results. Consequently, the SPEED questionnaire may be more suitable for diagnosing dry eye and conducting epidemiological investigations among Chinese college students.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- DED

Dry eye disease

- SPEED

Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness

- OSDI

Ocular Surface Disease Index

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

Authors’ contributions

XH-M contributed to design the study, data collection and management, and wrote the whole paper. RJ-G and JJ-W contributed to data interpretation. KL-Y, MH-W and ZP-X performed the statistical analysis. SW-R contributed to design the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Key Scientific Research Projects of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (No. 24B320012) and Scientific Research Project Fund of Nanyang Medical College (No. 2022ZRKX028).

Data availability

All data supporting the study is presented in the manuscript or available upon request from the corresponding author of this manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanyang Medical College in Henan Province, China. Informed written consent was obtained all participants in the study before, all the research methods followed the guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liang Q, Li J, Zou Y, Hu X, Deng X, Zou B, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals the heterogeneity of conjunctival microbiota dysbiosis in dry eye disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:731867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu K, Bunya V, Maguire M, Asbell P, Ying GS. Systemic conditions associated with severity of dry eye signs and symptoms in the dry eye assessment and management study. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(10):1384–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan C, Li A, Hao Y, Zhang X, Guo Y, Gu Y, et al. The relationship between circadian typology and dry eye symptoms in Chinese college students. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:1919–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saldanha IJ, Bunya VY, McCoy SS, Makara M, Baer AN, Akpek EK. Ocular manifestations and burden related to Sjogren syndrome:results of a patient survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;219:40–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashmani N, Munaf U, Saleem A, Javed SO, Hashmani S. Comparing SPEED and OSDI questionnaires in a non-clinical sample. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:4169–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asiedu K, Kyei S, Mensah SN, Ocansey S, Abu LS, Kyere EA. Ocular surface disease index (OSDI) versus the standard patient evaluation of eye dryness (SPEED):a study of a nonclinical sample. Cornea. 2016;35(2):175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang B, Liu XJ, Sun YF, Su JZ, Zhao Y, Xie Z, et al. Development and validation of the Chinese version of dry eye related quality of life scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pucker AD, Dougherty BE, Jones-Jordan LA, Kwan JT, Kunnen CME, Srinivasan S. Psychometric analysis of the speed questionnaire and CLDEQ-8. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(8):3307–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo B, Chan KY, Li PH, Tse JSH, Liao X, Eng D, et al. Validation and repeatability assessment of the Chinese version of the ocular surface disease index (OSDI), 5-item dry eye (DEQ-5), and contact lens dry eye questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8) questionnaires. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2024;17:102353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aljarousha M, Alghamdi WM, Attaallah S, Alhoot MA. Ocular surface disease index questionnaire in different languages. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. 2025;13(4):190–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang F, Yang L, Ning X, Liu J, Wang J. Effect of dry eye on the reliability of keratometry for cataract surgery planning. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2024;47(2):103999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou YB, Fan NW, Lin PY. Value of lipid layer thickness and blinking pattern in approaching patients with dry eye symptoms. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54(6):735–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng Z, Chu X, Zhang C, Liu H, Yang R, Huang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety evaluation of a single thermal pulsation system treatment (Lipiflow®) on meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int Ophthalmol. 2023;43(4):1175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang XM, Yang LT, Zhang Q, Fan QX, Zhang C, You Y, et al. Reliability of Chinese web-based ocular surface disease index questionnaire in dry eye patients:a randomized, crossover study. Int J Ophthalmol. 2021;14(6):834–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngo W, Situ P, Keir N, Korb D, Blackie C, Simpson T. Psychometric properties and validation of the standard patient evaluation of eye dryness questionnaire. Cornea. 2013;32(9):1204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barabino S. Is dry eye disease the same in young and old patients? A narrative review of the literature. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22(1):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wróbel-Dudzińska D, Osial N, Stępień PW, Gorecka A, Żarnowski T. Prevalence of dry eye symptoms and associated risk factors among university students in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ezinne N, Alemu HW, Cheklie T, Ekemiri K, Mohammed R, James S. High prevalence of symptomatic dry eye disease among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in university of West indies, Trinidad and Tobago. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2023;15:37–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pult H, Wolffsohn JS. The development and evaluation of the new ocular surface disease Index-6. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(4):817–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee S, Agrawal D, Chaturvedi P. Ocular surface disease index((c)) and the five-item dry eye questionnaire:a comparison in Indian patients with dry eye disease. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(9):2396–00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou L, Parmanto B. Development and validation of a comprehensive well-being scale for people in the university environment (Pitt wellness Scale) using a crowdsourcing approach:cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e15075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furtner J, Berghoff AS, Albtoush OM, Woitek R, Asenbaum U, Prayer D, et al. Survival prediction using Temporal muscle thickness measurements on cranial magnetic resonance images in patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(8):3167–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Duan X, Zhang Z, Yang Z, Zhao C, Liang C, et al. Combination of CT and telomerase+ Circulating tumor cells improves diagnosis of small pulmonary nodules. JCI Insight. 2021;6(11):e148182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin YY, Wang LC, Hsieh YH, Hung YL, Chen YA, Lin YC, et al. Computer-assisted three-dimensional quantitation of programmed death-ligand 1 in non-small cell lung cancer using tissue clearing technology. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graae Jensen P, Gundersen M, Nilsen C, Gundersen KG, Potvin R, Gazerani P, et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease among individuals scheduled for cataract surgery in a Norwegian cataract clinic. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:1233–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the study is presented in the manuscript or available upon request from the corresponding author of this manuscript.