Abstract

Opuntia ficus-indica L. (prickly pear) contains natural compounds with known anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects. This study assessed the ability of normal (NCJ) and Lactobacillus-fermented prickly pear juice (FCJ) to reduce cadmium toxicity in male albino rats. Physical and chemical properties of both juices were analyzed, revealing that fermentation increased total phenolics and flavonoids, boosting antioxidant activity by 48.61 % and extending shelf life by 60 days.To evaluate cadmium detoxification, rats were divided into six groups: Group G1 (saline control), Group G2 (cadmium-intoxicated), Groups G3 and G5 (NCJ and FCJ only), and Groups G4 and G6 (cadmium exposure combined with NCJ or FCJ). After 60 days, the harmful effects of cadmium were assessed by measuring gene expression (TNF-α, P53, BCL-2, IL-1) and examining tissue histology. Both juices reduced cadmium toxicity markers, with FCJ showing superior efficacy. Furthermore, the juice treatments were safe for the rats, as no adverse effects were observed in Groups G3 and G5. These findings suggest that Lactobacillus-fermented juices may be effective in reducing cadmium contamination and promoting detoxification in biological systems.

Keywords: Antioxidant enzymes, Cd-detoxification, Lactobacilli, Opuntia ficus-indica L., Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Functional juice

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Cadmium (Cd) is a toxic heavy metal that can have serious health effects on humans. It is also an essential environmental pollutant; cigarette smoke, polluted water and air, and fast food contribute to public Cd exposure. Certain foods such as cereals, leafy vegetables, rice, and potatoes can accumulate Cd from contaminated soil. Cadmium can be ingested, inhaled, or absorbed transdermally; once inside, it circulates throughout the body and is ultimately expelled in the kidneys as urine [1]. Long-term Cadmium exposure may cause osteoporosis and increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, whereas acute exposure may induce stomach discomfort, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [2]. Moreover, Prickly pear is an excellent substrate for fermentation and nutritional supplements owing to its wide range of functional and nutritional properties [3]. Several therapeutic effects of prickly pear against cadmium-induced osteoporosis have been reported [4]. Its phenolic compound content supports its antioxidant capabilities, as it is considered to have the same potency as red grapes and grapefruit [5]. Ferulic acid, isorhamnetin, sinapic acid, and quercetin in vivo prickly pear, in addition to kaempferol, myricetin, luteolin, catechin, naringin, and syringaresinol [6], [7]. The presence of phenolic compounds in prickly pear fruit can contribute to the antioxidant protective role of this fruit against Cd toxicity [8]. Numerous strategies have been explored to reduce cadmium toxicity, with increasing attention given to the use of functional foods rich in antioxidants and detoxifying agents. Opuntia ficus-indica L. or Prickly pear, is a member of the Cactaceae family and has become naturalized in many parts of the world; it can be explored for this purpose [9]. The fruit is highly symbolic of Egyptian tradition. The total production of prickly pears in Egypt is nearly 31671 tons [10]. It has also been used for medicinal purposes because of its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory activity [11], and antimicrobial properties [12]. Opuntia fruit/pulp extracts possess medicinal and nutraceutical characteristics, including antidiabetic [13], cardioprotective, neuroprotective [14], anti-inflammatory [15], and hepatoprotective properties [16]. Fermentation of plant-based substrates with lactic acid bacteria, especially Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, is known to enhance the bioavailability and stability of bioactive compounds. Functional fermented beverages have gained popularity due to their enriched antioxidant activity and probiotic content, which may contribute to metal detoxification through mechanisms such as metal ion chelation, microbial biosorption, and gut microbiota modulation [17], [18]. However, limited research has investigated the synergistic role of Opuntia ficus-indica L. juice and fermentation in combating cadmium-induced toxicity in vivo. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to develop and evaluate the protective effects of Lactobacillus-fermented juice (FCJ) and non-fermented juice (NCJ) of prickly pear juices against cadmium-induced toxicity in male albino rats. The study aimed to assess the juices’ physicochemical properties, antioxidant potential, and their effects on cadmium accumulation, oxidative stress biomarkers, gene expression, and tissue histopathology in the liver and kidneys. This research addresses a critical gap by providing mechanistic insight into the detoxification potential of a natural, culturally significant fruit-based intervention and its enhancement through microbial fermentation.Materials and methods

2. Materials

The prickly pear fruits (Opuntia ficus-indica, yellow cultivar) used in the present study were purchased from a market in Alexandria, Egypt. The fruits were cleaned, peeled, removed seeds and prepared for the juice preparation step. Prickly pear juice was prepared according to a previously described method [19], and 100 g of fruit pulp was briefly mixed with 200 mL of distilled water for 5 min using a blender (Kenwood, Dubai, UAE). The juice was pasteurized (64°C/30 min) and divided into two treatments: non-fermented prickly juice (NCJ) and fermented prickly juice (FCJ), which were inoculated with functional strain Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RM1 (ca. 4 %, v/v, corresponding to ca. 9.0 Log CFU/mL), incubated at 37 °C/ 7 h, and then stored (at 4 °C) until further analysis.

Concerning the strain applied for fermentation, the Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RM1 strain was isolated from fermented milk (Rayeb milk) and submitted to NCBI GenBank under accession number MF81770868. This was identified in detail in previous works [20], [21]. The strain preparation and activation steps were performed using De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) media to propagate the probiotic strain at 30 °C/ 24 h and a pH of 5.7 ± 0.1. Before use, the culture was activated in sterile skimmed milk at 37 °C/ 8 h and then inoculated (ca. 4 % v/v) into pasteurized Opuntia ficus-indica L. juice.

Microbiological media were used to perform microbial analyses as described previously [22]. The total viable count (TC) was estimated on plate count agar (PCA), LAB was assessed by plating on MRS (Lactobacilli sp.), Enterobacteriaceae was counted using violet red bile glucose (VRBG) agar media, and coliforms on violet red bile (VRB) agar media [23]. These media were purchased from Oxoid Co. (Leopardstown, Dublin, Ireland). On the other hand, yeasts and molds were assessed using potato dextrose agar (PDA) as previously described and the media was purchased from Biolife Co., Viale Monza, Milan, Italy.

2.1. Statement

The investigation was conducted based on the recommended NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the rats were treated according to the criteria of Investigations and Ethics for Laboratory Animal Care at the Pharmaceutical & Fermentation Industries Development Centre (Ethical approval IACUC# 17–1Q-1020). All experiments, care, housing, use of animals, and reporting were performed following the recommendations in the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of in-vivo Experiments) guidelines and regulations [24]. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used in the experiments.

2.2. Physicochemical properties of prickly pear juice

2.2.1. Determination of pH

The pH values for non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice were measured (as a fresh juice and after the total time of the fermentation process (7 h/ 37 °C) using an ADWA pH meter (model AD1030; ADWA Instruments, Romania).

2.2.2. Determination of titratable acidity

Titratable acidity of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice was determined as the citric acid percentage by titrating with 0.1 M NaOH using phenolphthalein (C20H14O4) indicator [25] that was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

2.2.3. Determination of ascorbic acid

Titrimetric estimation of ascorbic acid was done using 2, 6-dichloro-phenol-indophenol reagent and was expressed in milligrams of ascorbic acid equivalent per 100 g (mg as equiv./100 g) of fresh weight [26].

2.2.4. Determination of total soluble solid

The total soluble solid (TSS) content was measured in juices using a portable refractometer (NR 101 Spain) following a previously described methodology [27].

2.2.5. Determination of the viscosity of juices

NCJ and FCJ juice viscosities were measured using a JP Selecta Wide Range Rotary Viscometer (Model STS-2011, Valencia, Spain) set to 100 rpm/20 C and spindle number L3. After 50 s of shearing, the results were reported in centipoises (cPs) [28].

2.2.6. Color analyses

The features of juice color were examined using a tristimulus colorimeter (Smart Color Pro, USA) [29]. It was represented using L* (100 = white, 0 = black), a* (positive = redness, negative = greenness), and b* (positive = yellowness, negative = blueness) values. The analyses of color were carried out in triplicate on materials subjected to the identical processing conditions, and mean values with standard deviations were recorded as the results.

2.2.7. Sensory evaluation of prickly pear juices

Sensory evaluation was conducted following institutional committee approval of the SRTA city, Alexandria, Egypt. An expert panel of 20 males and 20 females (aged between 25 and 54 years) evaluated the samples for taste, color, odor, consistency, viscosity, and overall acceptability [21]. The color, smell, taste, texture, appearance, and overall acceptability of the juice samples were evaluated using a scale of ten categories: 1 (thoroughly dislike), 3 (dislike), 5 (neither dislike nor like), 7 (like) and 9 (extremely like).

2.2.8. Sugar profile of the juice

The investigated juice samples were hydrolyzed in two steps according to the methodology that described before [30]. Hydrolysates sugar content was measured using a high-performance liquid chromatography apparatus (Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC Series, USA) equipped with a quaternary pump and monosaccharide column (300 mm × 7.8 mm; a Phenomenx® Rezex RCM; operated at 80°C). Separation process was accomplished using isocratic elution with water (HPLC-grade; flow rate 0.6 mL/min), where injection volume was adjusted (20 μL), and a detector of refractive index type (running at 40° C) utilized for sugar detection [31].

2.3. Phytochemical analysis

2.3.1. Determination of total phenolic content (TPC)

The total phenolic content (TPC) of Opuntia ficus-indica L. juices was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu spectrophotometric method, and the results were expressed as micrograms of Gallic acid equivalents (µg GAE) per milligram (mg) of dry juice [32].

2.3.2. Determination of total Flavonoid content (TFC)

The total flavonoid concentration was calculated using the aluminium chloride colorimetric technique [33]. Concentrations of total flavonoids were given in terms of microgram Quercetin (μg Q) equivalents per mg of dry juice.

2.3.3. Bioactive compound profile (RP‑HPLC)

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to analyze phenolic acids, flavonoids, and betalains in Opuntia ficus-indica (prickly pear) juice. Fresh juice was filtered, centrifuged, acidified, and passed through 0.22 µm filters before analysis. Samples were injected into an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system with a C18 column using a gradient elution of 0.1 % formic acid in water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min with an injection volume of 20 µL. Detection was conducted at 280 nm for phenolic acids, 360 nm for flavonoids, and 535 nm for betalains. Identification was based on retention time and UV spectra compared to established standards, whereas quantification utilized external calibration curves. Results were expressed in milligrams per 100 mL of juice [34].

2.3.4. Determination of antioxidant potentials of juice

Opuntia ficus-indica L. juice was lyophilized for 48 h at 56 ͦ C in a Dura-Dry MP freeze dryer (FTS Process, USA at 0.04 Mbar). Antioxidant activity was determined by scavenging DPPH free radicals [35]. Each juice sample concentration was 7.81, 15.6, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 µg/mL. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard antioxidant at the same concentration.

2.3.5. Determination of microbiological properties of juices

The juice samples (fermented and non-fermented; 1 mL/sample) after a well-homogenizing step (2 min/ 20 °C+1) were serially diluted using a sterile peptone-water solution (0.1 %, w/v). Samples were examined for total viable count (TC), Lactobacilli content, Enterobacteriaceae, coliforms, yeasts, and fungi [22].

2.4. Assessment of NCJ and FCJ juices against Cd-intoxicated male rats

2.4.1. Experimental model and ethics

Male albino rats (150–155 g) were obtained from the Egyptian Organization for Biological Products and Vaccines (Egypt). Animals were housed in SRTA-City in standard cages under specific pathogen-free conditions and a 12:12 light-dark cycle at 22–25 °C with food and water available ad libitum and acclimatized to housing conditions for at least one week before experiment. All procedures were approved by the City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications Animal Ethics Committee (IACUC# 17–1Q-1020), conducted according to the criteria of the Investigations and Ethics for Laboratory Animal Care at the Pharmaceutical & Fermentation Industries Development Center (PFIDC), and in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Thirty animals were randomly placed into six experimental groups (5 rats each). The groups received one of the following treatments daily for 60 d.

The cadmium dose (10 mg/kg body weight, intraperitoneally) was selected based on previous toxicological studies [36], [37], where it reliably induced systemic oxidative stress and organ toxicity without causing acute lethality, allowing for effective evaluation of protective interventions.

-

•

Group 1 (normal): rats were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 0.9 % NaCl (physiological saline).

-

•

Group 2: Rats were intraperitoneally injected with 10 mg/kg CdCl2 dissolved in saline.

-

•

Group 3: Rats were orally administered NCJ (200 mg/kg dissolved in saline) by gavage.

-

•

Group 4: Rats were pre-administered 200 mg/kg NCJ 2 h before intraperitoneal injection of 10 mg/kg CdCl2.

-

•

Group 5: rats orally gavaged with FCJ (200 mg/kg dissolved in saline).

-

•

Group 6: rats were pre-administered 200 mg/kg FCJ 2 h before intraperitoneal injection of 10 mg/kg CdCl2.

The rats were administered daily according to the doses described for each group and up to 60 days of treatment, as per the experimental design. At the end of the experiment, the rats were sacrificed under (4–5 %) isoflurane anesthesia. Organs were rapidly removed, weighed, and homogenized in 10 % (w/v) cold 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for biochemical analysis [36].

2.4.2. Impact on body weight

The rats' initial and final body weights and the organs' weights were assessed as previously described [38].

2.4.3. Haematological parameters assessment

Hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), red blood cell (RBCs) count, white blood cell (WBCs) count, and differential count of white blood cells (monocytes, lymphocytes, and neutrophils) were assessed in rat blood samples using (Cell-Dyn® 6000 Hematology analyzer) [39].

2.4.4. Lipid profile analyses

Blood samples were initially held stationary at 0°C/ 30 min and then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 min/ 4°C. Serum total cholesterol (T-CH), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triacylglycerol (TG), and total lipids were determined with commercial kits (Bio Diagnostic kit), and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) was calculated using the equation (Triglyceride/5) [39].

2.4.5. Liver and kidney functions

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine transaminase (ALT), and aspartate transaminase (AST) enzyme activity were measured using a colorimetric approach [40]. Serum creatinine, uric acid, and bilirubin levels were measured using previously described techniques [41], [42].

2.4.6. Determination of cadmium concentration

We used the technique described in [36] to determine the Cd content. The liver/kidney tissues were weighed and dried (250 °C for 4 h). The dried samples were heated to 150 °C for 5 h in a mixture of 2 M nitric acid and 2 M hydrochloric acid. The samples were then diluted to a final volume of 50 mL with deionized water. Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) at 283.3 nm (ZEEnit 700 P-Graphite furnace absorption spectrometer (GFAAS), Analytik Jena, Germany) was used to determine the Cd content. Cd levels are reported in micrograms per milligram of fresh liver and kidney tissue (µg Cd/g tissue).

2.4.7. Determination of Malondialdehyde (MDA)

It was revealed that malondialdehyde (MDA) in kidney and liver homogenates is a significant diagnostic tool for lipid peroxidation. According to Tappel, and Zalkin, [41], The reaction was carried out according to Arango Duque and Descoteaux, [40], and the results were expressed as micromolars for each gram of protein (µM/g protein).

2.4.8. Determination of the antioxidant enzyme activities

Antioxidant enzyme activity was assessed in the homogenized kidney and liver samples. Homogenate tissue (10 % w/v) in phosphate buffer saline (0.1 M PBS; pH7.4) was prepared and then centrifuged (at 10,000 ×g /20 min/ 4°C). GPx activity was evaluated using a previously described methodology [43]. GPx and GST activity levels are expressed as units per gram of protein (U/g protein). SOD activity was determined following the methods outlined by Marklund et al., [43], where protein content in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford assay, with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1 mg/mL) as a standard to determine the protein concentration in the supernatant [44].

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Each rat was decapitated, and then a sample of its liver and kidneys was taken and frozen at (-80 °C) for later use. Single-step RNA isolation with acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction was used for manual RNA extraction [45]. SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and gene-specific primers were added to the synthesized cDNA (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). The target and GPDH reactions were carried out individually using Real-Time PCR (Rotor-Gene Q, QIAGEN Hilden, Germany) (Rotor-Gene Q, QIAGEN Hilden, Germany).

The temperature and time used were as follows: denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, annealing at 45°C for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 60 s, for a total of 40 cycles. Step One Software calculates the number of cycles needed to identify a change (Life Technologies). The mRNA expression of each target gene was normalized to that of the GPDH gene and expressed as a fold change relative to the controls. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Relative changes in gene expression levels were calculated using the 2 − ∆∆Ct method [46].

The primer sequences used for the amplification of target genes in rats were

TNF-α (F, 5-ACT GAA CTT CGG GGT GATTG 3′; R, 5-' GCT TGGTGG TTT GCT ACGAC-3′), P53(F-5′AGGGATACTATTCAGCCCGAGGTG-3′; R, 5-'ACTGCCACTCCTTGCCCCATTC-3′), BCL-2(F, 5-'ATGTGTGTGGAGAGCGTCAACC-3′; R,-5′ TGAGCAGAGTCTTCAGAGACAGCC-3′), and IL-1β (F-5′ CACCTCTCAAGCAGAGCACAG 3′; R-5′GGGTTCCATGGTGAAGTCAAC-3′).

2.6. Histopathological examination

Liver and kidney tissue samples were fixed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin at 25 °C for 24 h before being dried, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (4 – 5 mm). For light microscopy, hematoxylin and eosin staining were used to color deparaffinized slices uniformly. The original magnification of the images was 400x (Nikon Eclipse E200-LED, Tokyo, Japan) [47].

2.7. Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS version 16.0 was used to examine the data given to the computer. Means and standard deviations were used to characterize quantitative data. The F-test (analysis of variance) and Post Hoc test (Tukey) were employed to compare the groups under study, while the paired t-test was used to examine the two datasets. The results were deemed significant at the 5 % level [48].

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Properties

Table (1) clarifies the physicochemical parameters of NCJ and FCJ, with pH values of 5.91 ± 0.10 and 5.16 ± 0.05, respectively. Titratable acidity (TA) levels for NCJ and FCJ were 0.04 ± 0.0057 and 0.10 ± 0.010, respectively (Table 1). The NCJ and FCJ have high ascorbic acid (AA) content (32.50 ± 0.65, 33.50 ± 1.55 mg/100 g) (Table 1). After 24 h of fermentation, the AA concentration decreased only marginally. The TSS of NCJ and FCJ was between 0.22 ± 0.015 and 0.26 ± 0.01º Brix, respectively, with no significant differences (Table 1). The viscosity of NCJ and FCJ recorded 54.33 ± 1.52 and 53.16 ± 1.04 cP, respectively, with insignificant differences (Table 1). Indicators of yellow color intensity in prickly pear juice compared to non-fermented and fermented with LAB are shown in (Table 1). The color parameters were significantly changed by fermentation to decrease (a*) and (b*) values and increase lightness L in LAB-fermented juice. Regarding the sensory characteristics of juices (non-fermented or fermented), the results reflect the preference of the panelists' board for FCJ regarding its taste and viscosity. However, they recommend the color and appearance of the non-fermented juice of prickly pears. In conclusion, the panelists recommended FCJ as the best, giving it a high score for overall acceptability.

Table 1.

Physicochemical analysis of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice.

| Physiochemical parameters | NPJ | FPJ |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 5.91 ± 0.10a | 5.16 ± 0.05b |

| TA (%) | 0.04 ± 0.0057a | 0.10 ± 0.010a |

| TSS (Brix) | 0.22 ± 0.015a | 0.26 ± 0.01a |

| Ascorbic acid (mg equiv. /100 g) | 33.50 ± 1.55a | 32.50 ± 0.65b |

| Viscosity (cP) | 54.33 ± 1.52a | 53.16 ± 1.04b |

| Color analyses | ||

| L* | 73.98 ± 0.42b | 76.56 ± 0.96a |

| a* | 12.95 ± 1.64a | 11.33 ± 1.02b |

| b* | 12.09 ± 1.50a | 10.14 ± 1.53b |

| HPLC analysis of sugars | ||

| Glucose (mM) | 6.33 ± 0.10a | 6.39 ± 0.05a |

| Fructose (mM) | 5.53 ± 0.40a | 5.59 ± 0.09a |

The mean values indicated in the same columns within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05). Represented data are the means of duplicates ±SD. NPJ: Non-fermented prickly juice; FPJ: Fermented prickly Juice; TA: Titratable acidity; TSS: Total soluble solids.

3.2. Sugar Content Analysis

Table (1) shows the HPLC analysis of NCJ and FCJ sugars. The results indicated insignificant differences between the fructose and glucose contents of NCJ and FCJ. Fructose contents of the examined juice were 5.53 ± 0.40 and 5.59 ± 0.09 mM for NCJ and FCJ, respectively. Furthermore, the FCJ recorded glucose content of 6.39 ± 0.05 mM, while NCJ recorded 6.33 ± 0.10 mM.

3.3. Total Phenolic, Flavonoid Contents and Antioxidant Activity

The phenolic content of NCJ and FCJ significantly differed between the juice extracts. Higher levels of TPC (315.80 ± 2.02 µg GAE/g) were detected in the FCJ compared with NCJ that recorded (285.83 ± 1.25 µg GAE/g) (Table 2). As illustrated in (Table 2), flavonoid contents of NCJ and FCJ juice showed that fermented prickly pear juice had the highest amount with (135.27 ± 1.41 µg catechol/g) than the non-fermented juice (119.03 ± 1.81 µg catechol/g). Concentration-dependent linear increases in DPPH radical scavenging activities were seen for the NCJ and FCJ extracts, with maximum values of 225.79 and 116.04 µg/mL, respectively (Fig. 1). The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of the NCJ and FCJ extracts were 225.79 ± 2.90 µg/mL, 116.04 ± 1.74.

Table 2.

Total phenolic (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC) and antioxidant activity of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice.

| Juices | TP | TF | IC50 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPJ | 285.83 ± 1.25a | 119.03 ± 1.81b | 225.79 ± 2.90a |

| FPJ | 315.80 ± 2.02b | 135.27 ± 1.41a | 116.04 ± 1.74b |

The mean values indicated in the same columns within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05). Represented data are the means of n = 5 ±SD.

NPJ: Non-fermented prickly juice; FPJ: Fermented prickly Juice. TP: Total phenolics (µg GAE/gram); TF: Total flavonoids (µg catechol/gram). Antioxidant activity IC50 value (μg/mL) of ascorbic acid was 6.27 ± 0.02.

Fig. 1.

Antioxidant activity determined using the DPPH assay in fermented and non-fermented juice. NPJ: Non-fermented prickly juice; FPJ: Fermented prickly Juice; AA: Ascorbic acid as standard antioxidant. Each measurement was done at least in triplicate, and the values are the means ± SD.

3.4. HPLC Concentration Profile of Major Compounds in Opuntia ficus-indica Juice

The HPLC analysis of Opuntia ficus-indica juice revealed a diverse profile of bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, and betalains (Table 3). Among the flavonoids, quercetin was the most abundant (2.34 mg/100 mL), followed by isorhamnetin (1.35 mg/100 mL) and kaempferol (1.12 mg/100 mL). Regarding phenolic acids, gallic acid showed the highest concentration (2.1 mg/100 mL), with notable levels of caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, and p-coumaric acid ranging from 0.52 to 0.82 mg/100 mL. In terms of betalains, betanin and indicaxanthin were dominant, detected at 7.5 mg/100 mL and 7.2 mg/100 mL respectively, while isobetanin was present at 4.1 mg/100 mL.

Table 3.

HPLC Concentration Profile of Major Compounds in Opuntia ficus-indica Juice.

| Compound | Class | Concentration (mg/100 mL juice) |

|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | 2.34 |

| Isorhamnetin | Flavonoid | 1.35 |

| Kaempferol | Flavonoid | 1.12 |

| Gallic acid | Phenolic acid | 2.1 |

| Caffeic acid | Phenolic acid | 0.82 |

| Chlorogenic acid | Phenolic acid | 0.67 |

| Ferulic acid | Phenolic acid | 0.52 |

| p-Coumaric acid | Phenolic acid | 0.6 |

| Betanin | Betacyanin (betalain) | 7.5 |

| Isobetanin | Betacyanin (betalain) | 4.1 |

| Indicaxanthin | Betaxanthin (betalain) | 7.2 |

3.5. Microbiological Analysis of Juices During Cold Storage

Microbiological analyses of NCJ and FCJ were carried out during cold storage at day 1, 7, 14, 21, and 60 (Table 4). Fortification of FCJ with the probiotic lactic acid bacteria strain significantly affected Lactobacilli counts (P < 0.05) compared to NCJ. Coliforms, yeasts, and molds were not detected in any juice sample during storage. The total microbial count in FCJ was significantly higher than in NCJ, while Enterobacteriaceae counts decreased during storage (Table 4). Lactobacilli population in FCJ increased from 6.60 ± 0.13 log10 CFU/g on day 1–6.95 ± 0.13 log10 CFU/g on day 60. In contrast, NCJ showed increases only in total count (TC) and Enterobacteriaceae.

Table 4.

Microbiological counts of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice.

| Storage period (Days) | Total bacterial count |

Enterobacteriaceae |

Lactobacilli sp. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPJ | FPJ | NPJ | FPJ | NPJ | FPJ | |

| Fresh | 3.49 ± 0.24e | 4.62 ± 0.13c | 1.89 ± 0.22e | 1.08 ± 0.27d | ND | 6.60 ± 0.13c |

| 7 | 4.50 ± 0.20d | 4.94 ± 0.26c | 4.32 ± 0.12d | 1.70 ± 0.22d | ND | 6.93 ± 0.25bc |

| 14 | 5.61 ± 0.12c | 5.75 ± 0.15b | 5.75 ± 0.15c | 2.95 ± 0.22c | ND | 7.19 ± 0.17ab |

| 21 | 6.86 ± 0.20b | 7.56 ± 0.30a | 6.51 ± 0.07b | 3.72 ± 0.24b | ND | 7.53 ± 0.05a |

| 28 | 7.46 ± 0.20a | 7.93 ± 0.32a | 7.29 ± 0.13a | 4.49 ± 0.38a | ND | 6.95 ± 0.13bc |

NPJ: Non-fermented prickly juice; FPJ: Fermented prickly Juice. The mean values indicated in the same columns within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05). Represented data are the means of duplicates ±SD.

3.6. Assessment of NCJ and FCJ Impact Against Cd-Intoxicated Male Rats

3.6.1. Effect of NCJ and FCJ Treatment on Body and Organ Weights

The effects of NCJ and FCJ on rats' relative and organ weights are shown in Table 5. Cadmium in G2 significantly decreased body weight gain by 27.76 % compared to G1 (51.01 %). The liver and kidney weights also decreased in the cadmium-treated group (G2), recorded at 4.25 g and 0.59 g, respectively, compared to the negative control group (G1), which recorded 6.86 g and 1.33 g.

Table 5.

Effect of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice on relative body and organs weights of rats.

| Experimental groups | IW | FW | WG% | Liver weight | Kidney weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 152.02 ± 4.24a | 229.50 ± 5.44b | 51.01 ± 2.36a | 6.86 ± 0.82a | 1.33 ± 0.10ab |

| G2 | 152.50 ± 5.00a | 194.75 ± 4.19d | 27.76 ± 3.05c | 4.25 ± 0.37c | 0.59 ± 0.15c |

| G3 | 150.75 ± 5.61a | 234.25 ± 4.34ab | 55.53 ± 5.81a | 7.32 ± 0.19a | 1.56 ± 0.14a |

| G4 | 155.25 ± 4.64a | 217.25 ± 4.57c | 40.03 ± 5.17b | 5.53 ± 0.69b | 1.05 ± 0.12b |

| G5 | 152.02 ± 7.25a | 243.75 ± 6.23a | 60.53 ± 5.60a | 7.41 ± 0.57a | 1.48 ± 0.32a |

| G6 | 154.50 ± 6.24a | 234.50 ± 4.79ab | 52.02 ± 8.39a | 7.06 ± 0.27a | 1.23 ± 0.19ab |

IW: Initial body weights; FW: Final body weights; WG: %Weight gain. G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3, saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice (NPJ); G4, CdCl2 + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NPJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ); G6, CdCl2 + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ). The mean values indicated in the same columns within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05). Represented data are the means of n = 5 ±SD.

Treatment with NCJ (G3) and FCJ (G5) showed insignificant differences in liver and kidney weights compared to G1. Treatment with NCJ (G4) and FCJ (G6) improved weight gain to 40.03 % and 52.02 %, respectively, versus G2 (27.76 %). Similarly, G6 showed liver and kidney weights of 7.06 g and 1.23 g, respectively, close to those in G1.

3.6.2. Impact on Complete Blood Counts (CBCs)

Hematology parameter results illustrated in Table 6 show that cadmium toxicity led to significant decreases in hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), and red blood cells (RBCs) in G2 (9.80 g%, 32.20 %, 6.09 ×10⁶ cells/mm³) compared to G1 (14.40 g%, 45.20 %, 7.87 ×10⁶ cells/mm³), respectively. Treatment with NCJ and FCJ in G4 and G6 enhanced these parameters compared with G2. Additionally, the platelet (PLt) count in G2 increased to 1120.30 %. NCJ and FCJ treatments in G4 and G6 reduced PLt levels to 704.67 % and 770.62 %, respectively.

Table 6.

Effect of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice on CBCs of rats.

| Haematological parameters | Experimental Groups |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | |||

| Hb Content (g %) | 14.40 ± 0.45a | 9.80 ± 0.95c | 13.22 ± 1.25a | 11.16 ± 0.76bc | 12.56 ± 0.60ab | 10.13 ± 0.56c | ||

| RBC (cellsx106/mm3) | 7.87 ± 0.33a | 6.09 ± 0.36c | 8.39 ± 0.34a | 7.70 ± 0.43ab | 8.30 ± 0.30a | 6.96 ± 0.40b | ||

| Hct% | 45.20 ± 0.91a | 32.20 ± 0.96d | 44.73 ± 0.64a | 38.07 ± 0.45c | 41.76 ± 0.68b | 37.16 ± 1.15c | ||

| PLT% | 591.02 ± 4.58e | 1120.30 ± 2.00a | 894.02 ± 3.60b | 704.67 ± 4.16d | 699.32 ± 2.08d | 770.62 ± 2.08c | ||

| WBC (cellsx106/mm3) | 10.06 ± 1.10a | 10.53 ± 1.22a | 11.82 ± 0.85a | 12.50 ± 0.62a | 10.90 ± 0.85a | 10.76 ± 1.02a | ||

| Differential count of white blood cells (WBC) | ||||||||

| Mono. (%) | 6.13 ± 0.56a | 6.49 ± 0.49a | 6.16 ± 0.56a | 6.56 ± 0.40a | 6.10 ± 0.55a | 6.47 ± 0.85a | ||

| Lympho.(%) | 89.54 ± 1.82a | 70.60 ± 1.03c | 80.54 ± 0.82b | 78.05 ± 0.92b | 78.34 ± 0.48b | 79.04 ± 1.06b | ||

| Neutro. (%) | 20.23 ± 0.97d | 34.63 ± 0.77a | 22.36 ± 0.92c | 29.28 ± 0.95b | 28.50 ± 0.50b | 27.43 ± 1.10b | ||

| IG (%) | 0.10 ± 0.02bc | 0.09 ± 0.012c | 0.13 ± 0.03abc | 0.20 ± 0.05ab | 0.23 ± 0.03a | 0.16 ± 0.05abc | ||

| Eosino (%) | 2.38 ± 0.076bc | 2.97 ± 0.23a | 2.14 ± 0.15c | 2.55 ± 0.05abc | 2.34 ± 0.19bc | 2.72 ± 0.24ab | ||

| Baso (%) | 0.10 ± 0.03a | 0.10 ± 0.03a | 0.21 ± 0.017a | 0.20 ± 0.06a | 0.14 ± 0.025a | 0.17 ± 0.04a | ||

G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3 saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice (NCJ); G4, CdCl2+ non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ); G6, CdCl2+ fermented prickly pear juice(FPJ). Hb, Hemoglobin; RBC, Red blood cells; Hct, Hematocrit; PLT, Platelet; WBC, White blood cell; Mono., Monocytes; Lympho.; Lymphocytes; Neutro., Neutrophils; IG, Immature Granulocyte; Eosino, Eosinophils; Baso, Basophils.

Represented data are the means of n = 5 ±SD. The mean values indicated in the same rows within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05).

3.6.3. Lipid Profile Parameters

The results showed that total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides (TG), and total lipids were reduced, while low-density lipoprotein (LDL) was increased in G2 compared to G1 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effect of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice on plasma lipid profile of rat’s serum.

| Experimental groups | TC (mg/dl) | HDL (mg/dl) | LDL (mg/dl) | TG (mg/dl) | VLDL (mg/dl) | Total Lipid (mg/dl) | LDL/HDL | TC/HDL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 122.33 ± 2.51ab | 46.13 ± 1.30a | 49.84 ± 2.23bc | 145.83 ± 1.75a | 29.16 ± 0.35a | 542.80 ± 2.96a | 1.08 ± 0.03c | 2.65 ± 0.02c |

| G2 | 108.02 ± 2.00d | 31.46 ± 2.12d | 60.13 ± 2.20a | 119.20 ± 2.07b | 23.84 ± 0.41b | 502.17 ± 2.46 f | 1.91 ± 0.08a | 3.44 ± 0.28a |

| G3 | 124.17 ± 1.25ab | 45.50 ± 1.80a | 48.56 ± 1.40c | 141.83 ± 1.25a | 28.36 ± 0.25a | 536.02 ± 1.00b | 1.06 ± 0.06c | 2.73 ± 0.12c |

| G4 | 115.97 ± 1.43c | 35.13 ± 0.58c | 52.56 ± 0.73b | 121.93 ± 1.10b | 24.38 ± 0.22b | 513.40 ± 2.19e | 1.49 ± 0.03b | 3.30 ± 0.10a |

| G5 | 125.02 ± 1.90a | 39.83 ± 1.60b | 57.73 ± 0.87a | 144.80 ± 1.70a | 28.96 ± 0.34a | 531.17 ± 1.25c | 1.45 ± 0.04b | 3.14 ± 0.08ab |

| G6 | 119.77 ± 2.11bc | 41.83 ± 1.75b | 47.31 ± 0.70c | 142.87 ± 2.20a | 28.57 ± 0.44a | 526.30 ± 0.60d | 1.13 ± 0.06c | 2.86 ± 0.16bc |

G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3 saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G4, CdCl2 + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice(FPJ); G6, CdCl2 + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ). TC, Total cholesterol; HDL, High density lipoprotein; LDL, Low density lipoprotein; TG, Triglyceride; VLDL, Very low density lipoprotein. The mean values indicated in the same columns within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05). Represented data are the means of n = 5 ±SD

3.6.4. Liver and Kidney Functions

The considerable impact of Cd poisoning on kidney and liver function parameters is shown in Table (8). The Cd-induced group (G2) showed significant elevation in all liver functions, including aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and bilirubin. Due to the anti-oxidative effect of NCJ in G4 and FCJ in G6, there were significant decreases in all liver markers, especially bilirubin in G6 (3.18 mg/dL), which was restored to levels close to the healthy control G1 (2.85 mg/dL).

Table 8.

Effect of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice on kidney-liver serum biomarkers of rats.

| Experimental groups | ALT (IU/L) |

AST (IU/L) |

ALP (IU/L) |

Bilirubin mg/dl | Urea (mg/dl) | BUN (mg/dl) |

Creatinine (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 35.74 ± 2.04c | 54.23 ± 0.90d | 88.82 ± 2.05d | 2.85 ± 0.34c | 5.44 ± 0.40b | 2.5568 ± 0.40b | 0.61 ± 0.08b |

| G2 | 49.99 ± 1.84a | 77.50 ± 0.70a | 192.19 ± 1.29a | 7.58 ± 0.21a | 9.33 ± 0.77a | 4.3851 ± 0.77a | 0.92 ± 0.06a |

| G3 | 34.26 ± 0.86c | 52.70 ± 1.08d | 90.03 ± 1.73d | 2.74 ± 0.13c | 5.39 ± 0.19b | 2.5333 ± 0.19b | 0.62 ± 0.06b |

| G4 | 47.44 ± 1.32a | 70.46 ± 1.46b | 136.23 ± 0.87b | 4.14 ± 0.16b | 6.22 ± 0.08b | 2.9234 ± 0.08b | 0.69 ± 0.030b |

| G5 | 34.57 ± 1.29c | 53.20 ± 1.08d | 87.78 ± 1.48d | 2.64 ± 0.43c | 5.49 ± 0.18b | 2.5803 ± 0.18b | 0.60 ± 0.020b |

| G6 | 40.90 ± 1.21b | 59.17 ± 1.35c | 106.71 ± 0.67c | 3.18 ± 0.10c | 5.83 ± 0.34b | 2.7401 ± 0.34b | 0.64 ± 0.045b |

G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3 saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G4, CdCl2 + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ); G6, CdCl2 + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ). ALT, Alanine transaminase; AST, Aspartate transaminase; ALP, Alkaline phosphatase and BUN, Blood urea nitrogen. The mean values indicated in the same columns within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05). Represented data are the means of n = 5 ±SD.

Regarding kidney function, urea, BUN, and creatinine levels (Table 8) showed significant increases in G2 compared to G1. These parameters improved in rats treated with NCJ (G4) and FCJ (G6), with significant reductions in urea and creatinine levels compared to G2.

3.6.5. Cd Concentrations in Liver and Kidney Tissues

In the Cd-induced group (G2), the Cd concentration in the liver was 45.59 μg/g and in the kidney was 9.62 μg/g, representing a 4.7-fold higher accumulation in the liver (Table 9). Compared with G2, the group treated with FCJ showed a significant reduction in Cd levels to 2.72 μg/g in the liver and 1.18 μg/g in the kidney — a 3.5-fold reduction. NCJ treatment also reduced Cd levels but to a lesser extent (10.51 μg/g in the liver and 3.08 μg/g in the kidney).

Table 9.

Effect of non-fermented and fermented prickly pear juice on Cd concentrations in liver and kidney tissues.

| Experimental groups | Liver (μg/g) | Kidney (μg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| G1 | ND | ND |

| G2 | 45.59 ± 1.87a | 9.62 ± 0.51a |

| G3 | ND | ND |

| G4 | 10.51 ± 1.28b | 3.08 ± 0.38b |

| G5 | ND | ND |

| G6 | 2.72 ± 0.24c | 1.18 ± 0.05c |

G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3 saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G4, CdCl2 + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice(FPJ); G6, CdCl2 + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ). The mean values indicated in the same columns within variable with different superscripts (a, b and c) were significantly different (p < 0.05). Represented data are the means of n = 5 ±SD

3.6.6. Liver and Kidney MDA Levels and Antioxidant Enzymes

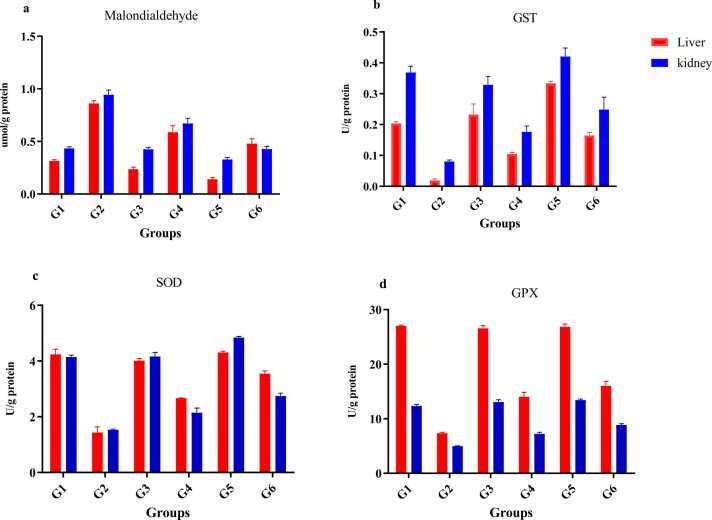

The antioxidant enzyme activities—superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)—were significantly higher in the FCJ-treated group (G6) than in the NCJ group (G4), indicating a stronger antioxidant response (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The MDA level and antioxidant enzyme activity in all the treated groups' liver and kidney tissues. TBARS; (b) GST; (c) SOD; (d) GPX. Each measurement was done at least in triplicate, and the values are the means ± SD for five rats in each group: TBARS=Thiobarbituric acid substances; GST=glutathione transferase; SOD=superoxide dismutase; GPx=glutathione Peroxidase MDA=Malondialdehyde. * P < 0.05 significantly different from the normal control group. G1, sasaline; G2, CdCl2; G3 saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G4, CdCl2 + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ); G6, CdCl2 + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ).

In terms of MDA (malondialdehyde) levels, ingestion of NCJ and FCJ (G3 and G5) showed no significant effect compared to control (G1) in kidney and liver tissues (P > 0.05). However, cadmium administration in G2 significantly increased MDA concentrations by 2.2-fold (kidney) and 2.7-fold (liver) versus G1. In NCJ-treated rats (G4), MDA levels were significantly reduced: 0.6703 ± 0.0486 µmol/g protein (kidney) and 0.9437 ± 0.0440 µmol/g protein (liver) (P < 0.05). FCJ (G6) showed a further significant reduction in MDA levels: 0.4273 ± 0.0263 µmol/g protein (kidney) and 0.4783 ± 0.0467 µmol/g protein (liver).

Cadmium exposure in G2 also significantly decreased GST, SOD, and GPx activities compared to G1 in both tissues (Figs. 2b, 3c, 3d). NCJ (G4) and FCJ (G6) treatments significantly increased these enzyme activities, with FCJ achieving higher levels than NCJ (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

P53, TNF-α, IL-1, and BCL-2 gene expression levels in liver and kidney tissue of all the treated groups. (a) P53; (b) TNF-α; (c) IL-1; (d) BCL-2. Each measurement was done at least in triplicate, and the values are the means ± SD for five rats in each group; P < 0.05, significantly different from the normal control group. G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3 saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G4, CdCl2 + non-fermented prickly pear juice (NCJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ); G6, CdCl2 + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ).

3.6.7. RT-PCR

The expression levels of key genes related to inflammation and apoptosis—TNF-α, P53, BCL2, and IL-1—were measured in kidney and liver tissues (Fig. 3a–d). Administration of NCJ (G3) and FCJ (G5) had insignificant effects on these genes compared to the control group (G1) (P > 0.05). Cadmium administration in G2 significantly increased P53, TNF-α, and IL-1 expression levels and decreased BCL2 expression compared to G1 (P < 0.05). In G4 (NCJ-treated Cd group), expression of P53, TNF-α, and IL-1 decreased significantly versus G2 in both kidney and liver tissues: Kidney: P53 (2.17 ± 0.21 vs. 3.04 ± 0.22), TNF-α (2.10 ± 0.14 vs. 4.12 ± 0.28), IL-1 (1.80 ± 0.06 vs. 2.23 ± 0.08); Liver: P53 (2.43 ± 0.07 vs. 3.42 ± 0.01), TNF-α (6.58 ± 0.04 vs. 9.45 ± 0.06), IL-1 (1.89 ± 0.01 vs. 2.21 ± 0.01). BCL2 expression was significantly higher in G4 than G2 (P < 0.05). In G6 (FCJ-treated Cd group), expression of P53, TNF-α, and IL-1 was significantly lower than in G2 in both tissues (P < 0.05), while BCL2 was significantly higher.

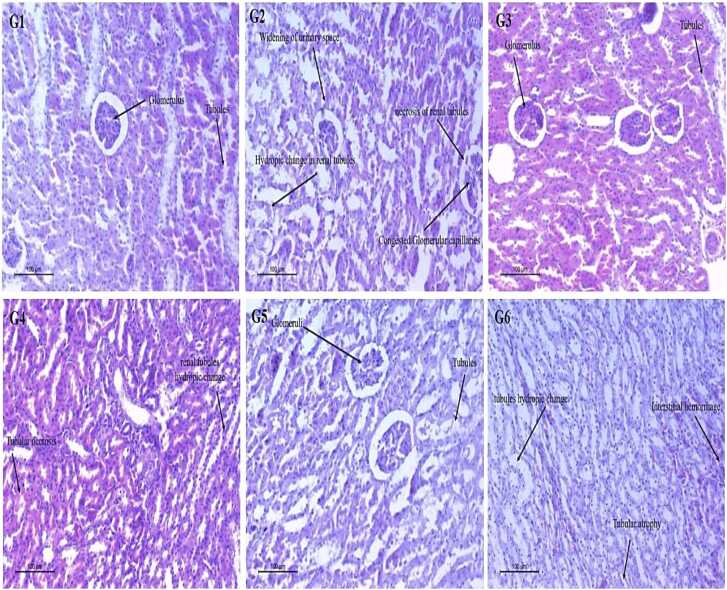

3.6.8. Histopathology of Liver and Kidney

In the control group (G1), liver histology showed normal hepatocytes, fine hepatic cords, sinusoidal gaps, and nuclei with fine chromatin (Fig. 4 G1, G3, G5). In contrast, CdCl₂-treated rats (G2) exhibited multiple pathological changes: scattered chromatin, nuclear shrinkage, cytoplasmic vacuolization, nuclear pyknosis, membrane rupture, chromatin strand fragmentation, necrosis, hemorrhagic spots, fibrosis, and inflammatory infiltration.

Fig. 4.

Histological changes of rats' kidney tissues. G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3, saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G4, CdCl2+ non-fermented prickly pear juice(NCJ); G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ); G6, CdCl2+ fermented prickly pear juice (FPJ).

In groups treated with NCJ (G4) and FCJ (G6), liver histo-architecture improved, showing reduced cytoplasmic vacuolization, typical sinusoidal gaps, and lamellar hepatocyte arrangements (Fig. 4, G4, G6).

Kidney histology in the control group revealed normal glomeruli, intact Bowman’s capsule, and well-distributed proximal, distal, and collecting tubules (Fig. 5 G1, G3, G5). In contrast, CdCl₂-treated rats (G2) showed atrophied glomeruli, pyknotic tubular nuclei, enlarged cortical tubule cells, and hemorrhagic patches between glomeruli and tubules (Fig. 5 G2). Treatment with NCJ and FCJ (G4, G6) restored renal cortical architecture with minimal deterioration (Fig. 5 G4, G6).

Fig. 5.

Histological changes of rats' liver tissues. G1, saline; G2, CdCl2; G3 saline + non-fermented prickly pear juice; G4, CdCl2+ non-fermented prickly pear juice; G5, saline + fermented prickly pear juice; G6, CdCl2+ fermented prickly pear juice.

4. Discussion

Lower pH increases organic acid content (e.g., citric and malic acids), hence amplifying bitterness and tanginess. The pH values suggest compositional differences affecting sensory qualities, especially bitterness. Reflecting the effects of the probiotic strain utilized, titratable acidity (TA) is a more accurate indication of acid effect on taste than pH [25]. Although after fermentation ascorbic acid (AA) somewhat dropped, the drop stays within reasonable nutritional levels. Crucially aiding immune system and defense against oxidative stress, AA is an antioxidant. Ascorbic acid oxidase can be triggered by pasteurization, which helps to degrade it [49]. Comparable AA loss in orange juice also results from lactiplantibacillus plantarum fermentation [50]. Fruit juices naturally include citric, malic, and ascorbic acids [51]. Total soluble solids (TSS) mirror juice quality [52], [53] indicating sugar and organic acid concentrations, which influence sweetness and customer liking. Although NCJ and FCJ have very little TSS changes, even small discrepancies can affect taste impression. LAB strain and juice matrix help to understand how fermentation affects AA content [54], [55]. Men and women respectively can get about 90 % or 74 % of their daily AA with a 200 mL glass of NCJ or FCJ. viscosity greatly influences the flavor and sensation of a product on the tongue. FCJ delighted consumers' expectations for a smooth and balanced texture—something that made it more enjoyable and widely approved—by means of its relatively higher viscosity [21]. Its greater acidity at the same time most likely contributed to lower enzymatic browning, which can influence color particularly in fermentation [56]. Fascinatingly, participants seemed to assess NCJ more in terms of color; FCJ won them over with taste and texture. FCJ came out with the best overall rating at last.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) sugar analysis revealed a significant link in total sugar levels between the two juice varieties. This implies that a consistent way to tell fermented from non-fermented prickly pear liquids could be sugar level. Though the actual variations in fructose and glucose levels were somewhat little, the fermenting process depends much on these natural sugars, particularly fructose and glucose. A good fermentation depends on probiotic activity, which they assist generate. Although these sugars neither directly bind to or remove cadmium, they help probiotics' energy needs, therefore improving the detoxification process [57].

Our results showed higher TPC concentrations than that obtained by Verón for pasteurized NCJ (670.7 ± 4.0 μg GAE/mL) and FCJ (688.1 ± 34.3 μg GAE/mL), respectively [32]. In our study, flavonoid levels in prickly pear juice were higher than those in Annona squamosa juice (46–50 μg quercetin/g) [34]. Flavonoid levels were 187.80 ± 11.31 (mg EC/100 g) in acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) and 114.80 ± 0.04 (mg EC/100 g) in guava (Psidium guajava L.) fruit by-products fermented with probiotic Lactobacilli [58]. Generally, fermented prickly pear juice extract's antioxidant capacity (scavenging activity) was higher than non-fermented juice's. These results agree with Chan's reports that fermented bambangan exhibited higher antioxidant activity than non-fermented bambangan [59].

Microbial evaluation of fermented and non-fermented prickly pears was targeted to explore the changes in fresh juices during cold storage for up to 60 days. These results reveal microbial changes brought about by the fermentation process followed using the novel LAB strains. The results indicate the better characteristics of fermented juice than the crude (non-fermented juice) of the prickly pear. Adjunct probiotic cultures have been reported to reduce coliforms during juice storage [60]. The application of probiotics significantly increased the population of Lactobacilli (P < 0.05), maintaining high levels (>10⁶ log10 CFU/g) during 60 days of storage [61]. Most likely, starting and probiotic cultures along with milk non-starter LAB that survived pasteurization produced lactobacilli [62]. These findings show how over long-term storage probiotic fortification could help FCJ's microbiological stability and safety.

Unlike previous evaluation objectives, juices were administered to experimental rats to evaluate their efficacy in reducing cadmium toxicity. The insignificant differences in organ weights between G1 and treatment groups G3 and G5 agree with Almeer et al. [36], indicating protective effects. Preventive effects of NCJ (G4) and FCJ (G6) were evident in improved weight gain and organ weights compared to the cadmium-only group (G2). These results confirm those of Zhu and Athmouni [63], who linked similar effects of the great phenolic and flavonoid contents of prickly pear juice. Moreover already shown is the probiotic action of lactobacilli against cadmium poisoning [64]. Tissue damage and cellular degeneration caused by oxidative stress and cadmium exposure explain the noted weight loss in G2's organs [36].

The cadmium toxicity effect was clearly indicated by significant reductions in Hb, Hct, and RBCs in G2, confirming hematological damage. Treatment with NCJ and FCJ (G4 and G6) improved these levels, demonstrating their potential protective effects.

On the other hand, the elevated platelet count in G2 suggests enhanced coagulation activity due to cadmium stress. After treatment with NCJ and FCJ, PLt levels dropped reflecting a normalizing impact [2] revealed a similar observation about platelet count decrease with dietary intervention, so supporting the preventive action of functional juices in blood health under toxic stress.

The hypolipidemic effect of LAB is expressed by different mechanisms that reduce atherogenic indices, either through suppression of LDL concentrations or lowering of TG and total lipids, as previously reported by Abd El-Aziz et al. [65]. The observed changes align with the data on body weight augmentation, as heavy metal toxins like cadmium and zinc are recognized for diminishing feed consumption and appetite [66].

The elevated levels of AST, ALT, ALP, and bilirubin in G2 indicate cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity. The reductions seen in G4 and G6 highlight the preventive attributes of NCJ, especially FCJ, possibly associated with their antioxidant properties. The significant restoration of bilirubin in G6 to near-normal levels (3.18 mg/dL vs. 2.85 mg/dL in G1) emphasizes the potential of fermented juice.

LAB probiotics, such as Lactobacilli spp., play a role in cadmium detoxification by binding metals to negatively charged groups on their surface structures (carboxyl, hydroxyl, phosphate), preventing cadmium absorption. This aligns with previous research indicating the extraction of toxic metals (As, Cd, Pb, Hg) from water and food utilizing LAB strains [67], [68], [69].

Building on earlier work that highlighted the kidney-shielding power of prickly pear juice, our results show that both the native (NCJ) and fermented (FCJ) forms markedly reduced urea, BUN and creatinine. Fermentation amplifies the drink’s polyphenol load—raising overall phenols and flavonoids—which, in turn, helps guard the liver and kidneys from cadmium-induced injury.

In group G2, the liver accumulated a greater concentration of cadmium than the kidneys, underscoring the liver's function as an initial repository for metals. Nevertheless, the kidneys serve as the primary detoxification organs in the body; their continuous blood filtration and waste elimination render them susceptible to the effects of prolonged exposure [70]. Giving the animals native (NCJ) or fermented (FCJ) prickly-pear juice lowered cadmium levels in both organs, confirming the juices’ cleansing power. The fermented version worked better—likely because its Lactobacillus cultures can latch onto cadmium ions on their cell walls and pull them out of host tissues [64]. These findings reinforce earlier reports that probiotics help the body rid itself of heavy metals.

The results demonstrate that cadmium induces oxidative stress by blocking crucial antioxidant enzymes (GST, SOD, GPx), as previously reported [69]. In contrast, therapy using NCJ and FCJ alleviated these effects, with FCJ exhibiting superior efficacy, perhaps due to the improved bioavailability of antioxidants via fermentation. The substantial increase in MDA levels in G2 corroborates oxidative tissue damage resulting from cadmium exposure, in agreement with Badr et al. [71] and Ezedom et al. [70]. The FCJ therapy (G6) resulted in the most significant decrease in MDA, indicating potent free radical scavenging and metal-chelating properties. Increased enzyme activity and decreased MDA levels in G6 corroborate previous studies indicating that the fermentation of lactiplantibacillus plantarum enhances antioxidant capacity. This may entail the creation or production of antioxidant compounds during fermentation [37], encompassing molecules capable of chelating deleterious metals and neutralizing reactive oxygen species [72].

The increased protection observed in the FCJ- and NCJ-treated groups suggests that elevated amounts of phenolic acids and flavonoids in Opuntia ficus-indica juice enhance its notable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Quercetin, isorhamnetin, and kaempferol are acknowledged for their free radical scavenging, DNA protective, and enzyme-modifying properties. These characteristics can help to explain why rats exposed to cadmium had downregulation of the TNF-α, IL-1, and P53 genes. Gallic and caffeic acids improve the chelation of metal ions and lower lipid peroxidation, therefore matching the observed drop in MDA levels and improved histoarchitecture of the liver and kidneys. Furthermore, the increased activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GST, GPx) and the heightened concentrations of betacyanins (betanin, isobetanin) and betaxanthins (indicaxanthin) not only impart a vibrant hue to the juice but also contribute to cytoprotection and the regulation of oxidative stress pathways. These substances collaboratively enhance the detoxifying and preventive properties against cadmium-induced organ damage, hence augmenting the therapeutic efficacy of fermented prickly pear juice [73].

Genes such as P53, TNF-α, IL-1, and BCL2 act as reliable signposts for what is happening inside stressed cells—they flag oxidative damage, inflammation, or the push toward cell death. P53, for example, is the classic “guardian of the genome,” pausing the cell cycle for DNA repair or, if the damage is too severe, triggering apoptosis [74]. By contrast, TNF-α and IL-1 are frontline pro-inflammatory messengers [40], while BCL2 sits on the other side of the balance, blocking the cell-death cascade [75]. In the cadmium-exposed group (G2), expression of P53, TNF-α, and IL-1 shot up, whereas BCL2 dropped—clear molecular proof of cadmium’s inflammatory and pro-apoptotic punch. Supplementing with native prickly-pear juice (NCJ, G4) toned down these disruptions, and the fermented version (FCJ, G6) did even better: it sharply suppressed the pro-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory genes and revived BCL2 expression. That pattern mirrors earlier reports by Marcel et al. [76] and Yang et al. [77].

The enhanced protective efficacy of FCJ arises from its fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RM1, a process that significantly increases the bioavailability of its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds. Upon introduction, these chemicals bind to cadmium ions, neutralize detrimental free radicals, and modulate inflammatory signals, thus reducing tissue damage. Ultimately, the synergistic effect of increased polyphenols and fermentation byproducts provides robust gene-level protection in the FCJ group.

Histological findings confirm the pronounced hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of cadmium exposure, correlating with elevated liver enzymes (AST, ALT, ALP), renal markers (urea, creatinine, BUN), oxidative damage (MDA), and dysregulated gene expression (↑TNF-α, IL-1, P53; ↓BCL-2). Cd-induced damage includes necrosis, vacuolization, and glomerular atrophy. Treatment with NCJ, especially FCJ, significantly improved the histoarchitecture of the liver and kidney, corresponding with the restoration of biochemical and molecular markers. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic characteristics of fermented prickly pear juice were crucial in this protective effect. The high levels of polyphenols and flavonoids in FCJ, enhanced by fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RM1, promoted metal chelation, neutralization of reactive oxygen species, and tissue repair. The study validates previous findings, illustrating the protective advantages of natural polyphenols in mitigating hepatic and renal injury [78], [79]. This definitive layer of data substantiates FCJ's role as a detoxifying agent with diverse protective mechanisms—histological, metabolic, and genetic—against cadmium-induced organ toxicity.

5. Conclusion

This study developed a functional fermented beverage from Opuntia ficus-indica L. juice using Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RM1, resulting in enhanced antioxidant properties, improved storage stability, and high sensory acceptance. Both fermented (FCJ) and unfermented (NCJ) juices were safe for consumption and effectively mitigated cadmium-induced toxicity in rats. The juices improved antioxidant enzyme activity, modulated inflammation- and apoptosis-related gene expression, and preserved liver and kidney tissue integrity. Fermentation further amplified these effects, likely due to increased polyphenol bioavailability and probiotic activity. These findings highlight FCJ’s potential as a health-promoting nutraceutical, especially for individuals exposed to heavy metals.

Practical Implications: The findings of this study highlight the potential of FCJ as a functional health beverage with antioxidant and detoxification benefits. The improved sensory attributes and extended shelf life also present market opportunities for consumers seeking natural, health-promoting products. The protective effects against heavy metal toxicity suggest that FCJ could be valuable in occupational health settings, offering a natural solution for individuals exposed to cadmium and other toxins. These promising results pave the way for further research and applications in food safety and public health.

Ethical statement

This manuscript is original, has not been published previously, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to its submission. All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with ethical standards and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications (Approval No. 17–1Q-1020). The study adhered to the ethical guidelines for laboratory animal care established by the Pharmaceutical & Fermentation Industries Development Center (PFIDC) and complied fully with the ARRIVE guidelines to ensure the humane treatment and welfare of animals used in the study. No human subjects were involved in this study. The research was conducted in accordance with responsible scientific conduct and institutional policies regarding ethical research practices.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nourhan M. Abd El-Aziz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mohamed G. Shehata: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ebtehal A. Farrage: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ahmed N. Badr: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Amira M.G. Darwish: Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Mohamed Gamal Shehata reports was provided by City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications (SRTACity). If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

Handling Editor: Prof. L.H. Lash

Contributor Information

Ahmed N. Badr, Email: noohbadr@gmail.com.

Ebtehal A. Farrage, Email: Ebtehal_15@hotmail.com.

Mohamed G. Shehata, Email: gamalsng@gmail.com.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Yildirim S., Celikezen F.C., Oto G., Sengul E., Bulduk M., Tasdemir M., Cinar D.A. An investigation of protective effects of lithium borate on blood and histopathological parameters in acute cadmium-induced rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018;182:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-1089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenston S.S.F., Su H., Li Z., Kong L., Wang Y., Song X., Gu Y., Barber T., Aldinger J., Hua Q., Li Z., Ding M., Zhao J., Lin X. The systemic toxicity of heavy metal mixtures in rats. Toxicol. Res. 2018;7:396–407. doi: 10.1039/c7tx00260b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramoba L., Monyama M.C., Moganedi K. Storage potential of the cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) fruit juice and its biological and chemical evaluation during fermentation into cactus pear wine. Beverages. 2022;8:67. doi: 10.3390/beverages8040067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jihen T., Saida N., Amani S., Lamia M., Lazhar Z. Evaluation of biological activities of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes extract against cadmium-induced osteoporosis in male Wistar rats. J. Adv. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2020;2:26–39. doi: 10.14302/issn.2328-0182.japst-20-3447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bousbia N., Mazari A., Lamoudi L., Akretche-Kelfat S., Chibane N., Dif M.E. Evaluation of the phytochemical composition and the antioxidant activity of cactus pear flowers and fruit derivatives. Rev. Agrobiol. 2022;12:3235–3243. [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Mostafa K., El Kharrassi Y., Badreddine A., Andreoletti P., Vamecq J., El Kebbaj M., Hammed S., Latruffe N., Lizard G., Nasser B., Cherkaoui-Malki M. Nopal cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica) as a source of bioactive compounds for nutrition, health and disease. Molecules. 2014;19:14879–14901. doi: 10.3390/molecules190914879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mena P., Tassotti M., Andreu L., Nuncio-Jáuregui N., Legua P., Del Rio D., Hernández F. Phytochemical characterization of different prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill.) cultivars and botanical parts: UHPLC-ESI-MSn metabolomics profiles and their chemometric analysis. Food Res. Int. 2018;108:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-Cayuela T., Gómez-Maqueo A., Guajardo-Flores D., Welti-Chanes J., Cano M.P. Characterization and quantification of individual betalain and phenolic compounds in Mexican and Spanish prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L. Mill) tissues: a comparative study. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019;76:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2018.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Naqeb G., Fiori L., Ciolli M., Aprea E. Prickly pear seed oil extraction, chemical characterization and potential health benefits. Molecules. 2021;26:5018. doi: 10.3390/molecules26165018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Neney B.A.M., Zeedan K.I.I., El-Kotamy E.M., Gad G.G., Abdou A. Effect of using prickly pear as a source of dietary feedstuffs on productive performance, physiological traits and immune response of rabbit. Egypt. J. Nutr. Feeds. 2019;22:91–106. doi: 10.21608/ejnf.2019.75844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antunes-Ricardo M., Gutiérrez-Uribe J.A., Martínez-Vitela C., Serna-Saldívar S.O. Topical anti-inflammatory effects of isorhamnetin glycosides isolated from Opuntia ficus-indica. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/847320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khatabi O., Hanine H., Elothmani D., Hasib A. Extraction and determination of polyphenols and betalain pigments in the Moroccan prickly pear fruits (Opuntia ficus-indica) Arab. J. Chem. 2016;9:S278–S281. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2011.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abd F.H., El-Razek, Hassan A.A. Nutritional value and hypoglycemic effect of prickly cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L. Opuntia) fruit juice in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011;5:356–377. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gambino G., Allegra M., Sardo P., Attanzio A., Tesoriere L., Livrea M.A., Ferraro G., Carletti F. Brain distribution and modulation of neuronal excitability by indicaxanthin from Opuntia ficus-indica administered at nutritionally relevant amounts. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:133. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez-Maqueo A., García-Cayuela T., Welti-Chanes J., Cano M.P. Enhancement of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of prickly pear fruits by high hydrostatic pressure: a chemical and microstructural approach. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019;54:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2019.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serra A.T., Poejo J., Matias A.A., Bronze M.R., Duarte C.M.M. Evaluation of Opuntia spp. derived products as antiproliferative agents in human colon cancer cell line (HT29) Food Res. Int. 2013;54:892–901. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.08.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerbino E., Carasi P., Tymczyszyn E.E., Gómez-Zavaglia A. Removal of cadmium by Lactobacillus kefir as a protective tool against toxicity – ERRATUM. J. Dairy Res. 2014;81:287. doi: 10.1017/S0022029914000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daisley B.A., Monachese M., Trinder M., Bisanz J.E., Chmiel J.A., Burton J.P., Reid G. Immobilization of cadmium and lead by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 mitigates apical-to-basolateral heavy metal translocation in a Caco-2 model of the intestinal epithelium. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:321–333. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1526581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karabagias V.K., Karabagias I.K., Gatzias I., Riganakos K.A. Characterization of prickly pear juice by means of shelf life, sensory notes, physicochemical parameters and bio-functional properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;56:3646–3659. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03797-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mogahed Fahim K., Noah Badr A., Gamal Shehata M., Ibrahim Hassanen E., Ibrahim Ahmed L. Innovative application of postbiotics, parabiotics and encapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum RM1 and Lactobacillus paracasei KC39 for detoxification of aflatoxin M1 in milk powder. J. Dairy Res. 2021;88:429–435. doi: 10.1017/S002202992100090X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shehata M.G., Alsulami T., Abd El-Aziz N.M.A., Abd-Rabou H.S., El Sohaimy S.A., Darwish A.M.G., Hoppe K., Ali H.S., Badr A.N. Biopreservative and anti-mycotoxigenic potentials of Lactobacillus paracasei MG847589 and its bacteriocin in soft white cheese. Toxins. 2024;16:93. doi: 10.3390/toxins16020093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shehata M.G., Abd El-Aziz N.M., Darwish A.G., El-Sohaimy S.A. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei KC39 immobilized on prebiotic wheat bran to manufacture functional soft white cheese. Fermentation. 2022;8:496. doi: 10.3390/fermentation8100496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oblinger J.L., Kennedy J.E., Langston D.M. Microflora recovered from foods on violet red bile agar with and without glucose and incubated at different temperatures. J. Food Prot. 1982;45:948–952. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-45.10.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Percie du Sert N., Hurst V., Ahluwalia A., Alam S., Avey M.T., Baker M., Browne W.J., Clark A., Cuthill I.C., Dirnagl U., Emerson M., Garner P., Holgate S.T., Howells D.W., Karp N.A., Lazic S.E., Lidster K., MacCallum C.J., Macleod M., Pearl E.J., Petersen O.H., Rawle F., Reynolds P., Rooney K., Sena E.S., Silberberg S.D., Steckler T., Würbel H. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2020;40:1769–1777. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20943823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Do T.V.T., Fan L. Probiotic viability, qualitative characteristics, and sensory acceptability of vegetable juice mixture fermented with Lactobacillus strains, J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019;10:412–427. doi: 10.4236/fns.2019.104031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes D.E. Titrimetric determination of ascorbic acid with 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol in commercial liquid diets. J. Pharm. Sci. 1983;72:126–129. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600720208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jafari S.M., Jabari S.S., Dehnad D., Shahidi S.A. Effects of thermal processing by nanofluids on vitamin C, total phenolics and total soluble solids of tomato juice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017;54:679–686. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2505-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akalın A.S., Unal G., Dinkci N., Hayaloglu A.A. Microstructural, textural, and sensory characteristics of probiotic yogurts fortified with sodium calcium caseinate or whey protein concentrate. J. Dairy Sci. 2012;95:3617–3628. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hrušková M., Švec I., Sekerová H. Colour analysis and discrimination of laboratory prepared pasta by means of spectroscopic methods. Czech J. Food Sci. 2011;29:346–352. doi: 10.17221/25/2011-CJFS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shehata M.G., Darwish A.M.G., El-Sohaimy S.A. Physicochemical, structural and functional properties of water-soluble polysaccharides extracted from Egyptian agricultural by-products. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020;65:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.aoas.2020.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siragusa S., De Angelis M., Di Cagno R., Rizzello C.G., Coda R., Gobbetti M. Synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid by lactic acid bacteria isolated from a variety of Italian cheeses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:7283–7290. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01064-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewanto V., Wu X., Adom K.K., Liu R.H. Thermal processing enhances the nutritional value of tomatoes by increasing total antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:3010–3014. doi: 10.1021/jf0115589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakanaka S., Tachibana Y., Okada Y. Preparation and antioxidant properties of extracts of Japanese persimmon leaf tea (Kakinoha-cha) Food Chem. 2005;89:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shehata M.G., Abu-Serie M.M., Abd El-Aziz N.M., El-Sohaimy S.A. Nutritional, phytochemical, and in vitro anticancer potential of sugar apple (Annona squamosa) fruits. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:6224. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rashid N., Shimada Y., Ezaki S., Atomi H., Imanaka T. Low-temperature lipase from psychrotrophic Pseudomonas sp. strain KB700A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:4064–4069. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.9.4064-4069.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almeer R.S., Alarifi S., Alkahtani S., Ibrahim S.R., Ali D., Moneim A. The potential hepatoprotective effect of royal jelly against cadmium chloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is mediated by suppression of oxidative stress and upregulation of Nrf2 expression. Biomed. Pharm. 2018;106:1490–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adi P.J., Burra S.P., Vataparti A.R., Matcha B. Calcium, zinc and vitamin E ameliorate cadmium-induced renal oxidative damage in albino Wistar rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2016;3:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ismael N.M.M., Shehata M.G. Improvement of lipid profile and antioxidant of hyperlipidemic albino rats by functional Plantago psyllium cake. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2020;8:424–437. doi: 10.12944/CRNFSJ.8.2.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burtis C.A., Ashwood E.R., Tietz N.W. Elsevier; 1999. Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arango Duque G., Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:491. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tappel A.L., Zalkin H. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation in mitochondria by vitamin E. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959;80:333–336. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu A.H.B. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2006. Tietz clinical guide to laboratory tests-E-book. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marklund S., Marklund G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974;47:469–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:581–585. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu F., Xu Y., Wang Y., Wang Y. Real-time PCR analysis of PAMP-induced marker gene expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. BioProtoc. 2018;8 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Omotoso B.R., Abiodun A.A., Ijomone O.M., Adewole S.O. Lead-induced damage on hepatocytes and hepatic reticular fibres in rats; protective role of aqueous extract of Moringa oleifera leaves (Lam) J. Biosci. Med. 2015;3:9. doi: 10.4236/jbm.2015.35004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Barbary A.A.A., Alkhateeb M.A. DFT study of Se-doped nanocones as highly efficient hydrogen storage carrier. Graphene. 2021;10:49–60. doi: 10.4236/graphene.2021.104004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaprasob R., Kerdchoechuen O., Laohakunjit N., Sarkar D., Shetty K. Fermentation-based biotransformation of bioactive phenolics and volatile compounds from cashew apple juice by select lactic acid bacteria. Process Biochem. 2017;59:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodríguez H., Landete J.M., de la Rivas B., Muñoz R. Metabolism of food phenolic acids by Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 748T. Food Chem. 2008;107:1393–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.09.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pyo Y.H., Jin Y.J., Hwang J.Y. Comparison of the effects of blending and juicing on the phytochemicals contents and antioxidant capacity of typical Korean kernel fruit juices. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014;19:108–114. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2014.19.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang B., Peng B., Zhang C., Song Z., Ma R. Determination of fruit maturity and its prediction model based on the pericarp index of absorbance difference (IAD) for peaches. PLOS ONE. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li J., Zhang C., Liu H., Liu J., Jiao Z. Profiles of sugar and organic acid of fruit juices: A comparative study and implication for authentication. J. Food Qual. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/7236534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Filannino P., Di Cagno R., Gobbetti M. Metabolic and functional paths of lactic acid bacteria in plant foods: Get out of the labyrinth. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018;49:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Degrain A., Manhivi V., Remize F., Garcia C., Sivakumar D. Effect of lactic acid fermentation on color, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in African nightshade. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1324. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Managa M.G., Akinola S.A., Remize F., Garcia C., Sivakumar D. Physicochemical parameters and bioaccessibility of lactic acid bacteria fermented chayote leaf (Sechium edule) and pineapple (Ananas comosus) smoothies. Front. Nutr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.649189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parhi P., Liu S.Q., Choo W.S. Synbiotics: Effects of prebiotics on the growth and viability of probiotics in food matrices. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre. 2024;32 doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2024.100462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Oliveira S.D., Araújo C.M., Borges G.d.S.C., Lima M.d.S., Viera V.B., Garcia E.F., De Souza E.L., De Oliveira M.E.G. Improvement in physicochemical characteristics, bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of acerola (Malpighia emarginata D.C.) and guava (Psidium guajava L.) fruit by-products fermented with potentially probiotic lactobacilli. LWT. 2020;134 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan S.T., Padam B.S., Chye F.Y. Effect of fermentation on the antioxidant properties and phenolic compounds of Bambangan (Mangifera pajang) fruit. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023;60:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s13197-022-05615-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masoumikia R., Ganbarov K. Antagonistic activity of probiotic lactobacilli against human enteropathogenic bacteria in homemade tvorog curd cheese from Azerbaijan. Bioimpacts. 2015;5:151–154. doi: 10.15171/bi.2015.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shori A.B. The potential applications of probiotics on dairy and non-dairy foods focusing on viability during storage. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2015;4:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2015.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Viljoen B.C. The interaction between yeasts and bacteria in dairy environments. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001;69:37–44. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu X., Athmouni K. HPLC analysis and the antioxidant and preventive actions of Opuntia stricta juice extract against hepato-nephrotoxicity and testicular injury induced by cadmium exposure. Molecules. 2022;27:4972. doi: 10.3390/molecules27154972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]