Abstract

Background

The disruption of microbiota balance could be a pivotal factor in the complications arising from periodontal disease-induced inflammation outside the mouth. Nonetheless, it remains uncertain whether there is a direct causal relationship between the oral and gut microbiomes and gingivitis, especially in distinguishing between acute and chronic gingivitis.

Methods

We performed a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis using GWAS summary statistics from FinnGen data (149 acute gingivitis cases, 850 chronic gingivitis cases, and 195,395 controls) to explore the causal role of oral and gut microbiota. The primary analysis employed the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method, augmented by four supplementary approaches: weighted median, weighted mode, and MR Egger regression, all aimed at detecting and adjusting for horizontal pleiotropy.

Results

In the gut microbiota, the results of IVW showed that class Negativicutes, Verrucomicrobiae, genus Butyricicoccus, Eubacterium, Lactobacillus, order Selenomonadales and Verrucomicrobiales were linked to a higher risk of acute gingivitis, while family Peptostreptococcaceae, genus Coprococcus2, and genus Lachnospiraceae UCG001 were linked to a lower risk of acute gingivitis (P < 0.05). Class Erysipelotrichia, Methanobacteria, Verrucomicrobiae, family Defluviitaleaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Methanobacteriaceae, Verrucomicrobiaceae, genus Akkermansia, Christensenellaceae R 7group, Defluviitaleaceae UCG011, Methanobrevibacter, genus Paraprevotella, Senegalimassilia, order Erysipelotrichales, Methanobacteriales, Verrucomicrobiales, and phylum Cyanobacteria were linked to a higher risk of chronic gingivitis, while family Clostridiales vadin BB60 group, genus Allisonella, Dorea, and Lachnospiraceae UCG004 were linked to a lower risk of chronic gingivitis (P < 0.05). And in the oral microbiota, unknown Porphyromonas species (ASV0008) and Genus Porphyromonas were linked to higher risk of acute gingivitis (P < 0.05). Unknown Neisseria species (ASV0004) and unknown Veillonella species (ASV0001) were linked to higher risk of chronic gingivitis, while Class Bacilli was linked to lower risk of chronic gingivitis (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

This MR analysis confirms the distinct causal relationships between microbiota and both acute and chronic gingivitis, providing insights into potential prevention strategies in European.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-06658-z.

Keywords: Two-sample Mendelian randomization, Gut microbiota, Gingivitis, Genome-wide association study

Background

Gingivitis, a prevalent form of periodontal disease, arises from non-specific inflammation of the gum’s soft tissues, induced by tooth surface plaque. It is noteworthy that Chronic gingivitis caused by plaque is considered to be the most common clinical manifestation [1]. Gingivitis is marked by redness, swelling, and bleeding of the gums, without the loss of periodontal attachment [2]. Typically painless, it seldom causes spontaneous bleeding, often rendering the majority of patients unaware of or unable to recognize the condition [3]. Plaque-induced gingivitis is the most prevalent periodontal disorder among children and adolescents [4], with most kids exhibiting signs and symptoms of the disease [5]. Studies have found that gingivitis is more prevalent in pregnant women than non-pregnant women [6, 7]. Acute gingivitis is usually acute and short-lived, with symptoms of red, swollen and painful gums that bleed rapidly, whereas chronic gingivitis has a prolonged course with relatively mild symptoms and is characterised by long-term redness and swelling of the gums, tenderness and bleeding when brushing or biting hard objects. The prognosis of gingivitis is generally favourable, and the diseased tissue can return to normal once the tooth biofilm is removed [8]. However, if gingivitis progresses to periodontitis, loss of connective tissue attachments and bone damage can occur, which can eventually lead to tooth loss [8].

The oral and gut microbiota are the largest microbial habitat in the human body and is considered as a potential environmental factor affecting human living systems due to its important metabolic and immune functions. Scientists are increasingly directing their attention to the connection between the oral and gut microbiota and periodontal disease. Recent research has emphasized the “oral-gut axis,” a concept that underscores the interplay between oral and gut microbiota, potentially implicated in the interplay of periodontal disease-associated systemic inflammatory conditions [9]. It has been shown that in patients with periodontal disease, dysregulation of the oral microbiota by specific bacteria, including Clostridium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis, can lead to intestinal malignancies through the oral-gut axis [10]. Periodontitis represents a more severe affection of the periodontal tissues compared to gingivitis. Studies have shown that the oral microbiota is closely related to oral health [8]. Also, periodontal disease can induce gut microbiota imbalance through salivary microbiota, affecting intestinal health, and then affecting systemic diseases. Some studies suggest that the gut microbiota may influence gingivitis through homocysteine [11]. However, alterations in gut microbiota due to systemic diseases frequently coincide with changes in oral microbiota and may lead to local periodontal disease by influencing the host’s immune response [10]. These findings provide new evidence for the mechanism of association between periodontal disease and systemic disease.

In recent years, the observational studies on the relationship between gut microbiota and periodontal disease mainly focus on periodontal disease. Both animal experiments and observational research have identified a link between periodontal disease and intestinal microbiota changes [12]. Bajaj et al. have shown that by resolving the imbalance of oral and gut microbiota, inflammatory symptoms in patients with periodontitis and systemic diseases can be successfully alleviated [13]. Several nonsurgical periodontal treatments (e.g., mechanical plaque and calculus control, oral hygiene instruction, and topical antimicrobial therapy) play an important role in helping to maintain intestinal microecological homeostasis and reverse established microbiome dysbiosis [14]. Observational clinical studies have concluded that treatment of patients with periodontal diseases both reduces oral dysbiosis and alters gut microbial composition [15]. However, epidemiological studies on the relationship between oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis are still lacking, and the exact mechanism is unknown.

In this study, we employ Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis, using genetic variation as instrumental variables (IVs) to infer causality between exposure and outcome. The principles of MR studies are based on Mendelian laws, similar to randomized controlled trials (RCT) while avoiding high costs [16]. In epidemiological research, the presence of confounding factors significantly obstructs accurate causal inference between exposure and outcomes. Theoretically, the MR approach can effectively circumvent the impact of confounding variables and mitigate the influence of reverse causality. Through a two-sample MR analysis, we explored the genetic-level causal relationship between oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis, thereby advancing our understanding of gingivitis.

Materials and methods

Study design

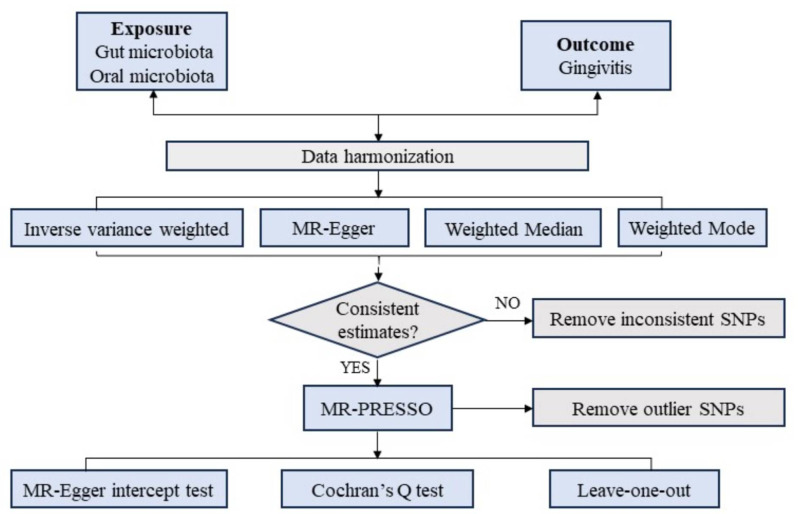

MR analysis employs genetic variants as IVs in an IV analysis framework [17, 18]. The MR Analysis has three important assumptions (Fig. 1). The first premise posits that the genetic variants serving as IVs should have a strong and consistent association with the exposure. The second premise stipulates that these genetic variations should be unrelated to any confounding factors. The third premise assumes that the chosen genetic variants influence the outcome risk solely through the risk factors and not through alternative pathways [19].

Fig. 1.

Study design overview. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism

GWAS summary data source

IVs pertaining to the gut microbiome were sourced from a genome-wide association study (GWAS) dataset provided by the international MiBioGen consortium [20]. And it contains 14,306 samples. This multi-ethnic, large-scale GWAS harmonized 16 S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing data and genotyping information from 18,340 individuals spanning 24 cohorts across the USA, Canada, Israel, South Korea, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Finland, and the UK. The objective of our initial study was to explore the relationship between autosomal human genetic variants and the gut microbiome, encompassing a total of 211 taxa (IDs provided in Table S1), which included 131 genera, 35 families, 20 orders, 16 classes, and 9 phyla. The GWAS data used for associations with gingivitis was obtained from FinnGen, a large-scale genomic research project developed in Finland. A detailed summary of the demographic and endpoint statistics for the 149 acute and 850 chronic gingivitis cases (and 195,395 controls) is provided in Table S2. Aggregated statistics from FinnGen can be accessed by the public on their official website (https://finngen.gitbook.io/documentation/data-download). According to the American Academy of Periodontology tips, gingivitis is the mildest form of periodontal disease. It causes the gums to become red, swollen and prone to bleeding. There is usually little or no discomfort at this stage (https://www.perio.org/). The International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) shows a discharge registration of ICD-K05.0 for acute gingivitis, which excludes acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis and herpesviral (herpes simplex) gingivostomatitis. The discharge registry for chronic gingivitis is ICD-K05.1, which includes NOS, desquamative, hyperplastic, simple marginal and ulcerative.

The GWAS data for 44 oral microorganisms were obtained from Evelina et al. [21]. And it contains 610 samples. Sample collection and processing have been described in detail by previous researchers. Briefly, samples were collected from saliva from 786 participants at Steno Diabetes Centre in Copenhagen, Denmark. Participants were asked not to brush their teeth on the day of the health assessment. Saliva production was stimulated with paraffin wax and the collected whole saliva samples were immediately stored at − 80 °C. The saliva samples were collected and processed in a single sample. DNA extraction and 16 S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of saliva samples were performed as reported [22]. Microbial DNA was isolated using the NucleoSpinSoil kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). bacterial cells were lysed using SL1 + Enhancer buffer SX. DNA yield and purity were assessed using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA), respectively. Genomic DNA was normalised to 30 ng per sample prior to PCR amplification of the 16 S rDNA V4 hypervariable region. PCR products were purified using the AmpureXP kit. PCR products were purified using the AmpureXP kit. The quality and quantification of the final libraries were determined using the 2100 Bioanalyser Instrument (Agilent, DNA 1000 reagent) and real-time quantitative PCR (EvaGreen TM). All samples were processed consecutively at the same location using the same equipment. Due to the number of samples, sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform using a double-ended 500-cycle sequencing chemistry in two runs (hereafter referred to as R1 and R2), the first of which yielded a total of 29,225,397 reads (R1, n = 666), and the second of which yielded a total of 4,193,449 reads (R2, n = 120).

More information about the exposure and outcome datasets are detailed in Table 1. All data were from public registries containing data from studies that already adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices, and no ethical approval was necessary. The original data used in this study, including the gut microbiota and cohort data as well as the analysis results, have been uploaded to the Zenodo database with the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14642359. The data can be accessed via the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/14642359.

Table 1.

Description of GWAS information

| Exposure/Outcome | Consortium/ID | Ancestry | Case/control | SNPs | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | |||||

| Gut microbiota abundance (class Actinobacteria id.419) | MiBioGen | European | 14,306 | 5,684,804 | 33462485 |

| Gut microbiota abundance (class Alphaproteobacteria id.2379) | MiBioGen | European | 14,306 | 5,470,627 | 33462485 |

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Phylum Firmicutes) | GCST90429799 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Phylum Proteobacteria) | GCST90429800 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Class Bacilli) | GCST90429801 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Order Bacteroidales) | GCST90429802 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Order Fusobacteriales) | GCST90429803 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Order Actinomycetales) | GCST90429804 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Order Clostridiales) | GCST90429805 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Family Veillonellaceae) | GCST90429806 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Family Pasteurellaceae) | GCST90429807 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Family Prevotellaceae) | GCST90429808 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Family Actinomycetaceae) | GCST90429809 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Family Lachnospiraceae_[XIV]) | GCST90429810 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Veillonella) | GCST90429811 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Haemophilus) | GCST90429812 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Streptococcus) | GCST90429813 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Neisseria) | GCST90429814 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Prevotella) | GCST90429815 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Porphyromonas) | GCST90429816 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Fusobacterium) | GCST90429817 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Rothia) | GCST90429818 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Schaalia) | GCST90429819 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Granulicatella) | GCST90429820 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Leptotrichia) | GCST90429821 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Genus Alloprevotella) | GCST90429822 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Veillonella species (ASV0001)) | GCST90429823 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species parainfluenzae) | GCST90429824 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Streptococcus species (ASV0003)) | GCST90429825 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Neisseria species (ASV0004)) | GCST90429826 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species histicola) | GCST90429827 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Streptococcus species (ASV0006)) | GCST90429828 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species parvula) | GCST90429829 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Porphyromonas species (ASV0008)) | GCST90429830 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Streptococcus species (ASV0009)) | GCST90429831 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species periodonticum) | GCST90429832 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species dispar) | GCST90429833 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Rothia species (ASV0012)) | GCST90429834 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species micronuciformis) | GCST90429835 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species pallens) | GCST90429836 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species mucilaginosa) | GCST90429837 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Rothia species (ASV0016)) | GCST90429838 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Schaalia species (ASV0017)) | GCST90429839 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (Species rogosae) | GCST90429840 | European | 610 | ||

| Saliva microbiota abundance (unknown Gemella) | GCST90429841 | European | 610 | ||

| Beta diversity of salivary microbiota | GCST90429842 | European | 610 | ||

| Outcome | |||||

| Acute gingivitis | FinnGen | European | 149/195,395 | 16,380,371 | - |

| Chronic gingivitis | FinnGen | European | 850/195,395 | 16,380,391 | - |

Selection of the genetic instruments

MR analysis was performed following three main assumptions [23]. First, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were significantly associated with the oral and gut microbiomes were screened. Since not enough SNPs associated with exposure were screened under the 5*10− 8 criterion, the screening criterion for SNPs associated with the gut microbiome was 5*10− 5, and 5*10− 6 for SNPs associated with the oral microbiome [24]. Secondly, a minor allele frequency (MAF) threshold of 0.01 was applied to the variants of interest. Thirdly, linkage disequilibrium (LD) among SNPs was addressed by excluding those with strong LD, as it could introduce bias in the results (with an r2 threshold of less than 0.001 and a clumping distance set at 10,000 kb) [25]. Fourth, if there is no corresponding SNP in the obtained GWAS, the proxy SNP with a higher LD relationship with the missing SNP is selected using the criterion that R2 is greater than 0.8 [17]. Furthermore, we calculate the F statistic for the IVs by using the following formula: F = R2*(N-2)/(1-R2), R2 denotes the variance of exposure explained by each IV. Generally, an average F statistic exceeding 10 is indicative of the absence of weak instrument bias [26]. We employed these meticulously selected SNPs as the definitive genetic IVs for the subsequent Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Statistical analysis

For features involving multiple IVs, this study employed four widely utilized MR methods, with the random-effects inverse variance weighted (IVW) approach serving as the primary technique [27], MR-Egger regression [23], Weighted Median [28], and Weighted Mode methods [29] as supplementary methods. The IVW method consolidates the Wald ratio estimates of causal effects from multiple variants, assuming all IVs are valid [27]. The MR Egger approach does not rely on nonzero mean pleiotropy but sacrifices statistical power. However, it is less precise and can be influenced by outlier genetic variants [28]. The Weighted Median method offers robust estimates of effective IVs, assigning at least 50% weight [28]. Meanwhile, the Weighted Mode method estimates the causal effect of the subset with the highest number of SNPs by grouping SNPs into subsets based on the similarity of their causal effects [29]. Detailed descriptions of these methods have been published elsewhere [23].

Sensitivity analysis

Horizontal pleiotropy was assessed using the MR-Egger intercept test and the MR-PRESSO global test [30]. Any outliers flagged by the MR-PRESSO global test were excluded, and a robustness analysis was conducted using the leave-one-out approach to confirm the findings. To quantify heterogeneity, we employed both the IVW method and MR Egger regression, utilizing Cochran’s Q statistic. A Q value exceeding the number of instruments minus one or a significant Q statistic at a P-value < 0.05 suggests the presence of heterogeneity or invalid instruments. All analyses were executed using the “TwoSampleMR” package in R version 4.0.5.

Results

SNP selection

In this study, we identified 267 and 9,254 independent SNPs with significant P-values as IV SNPs for oral and gut microbiota(detailed in Table S3). All F-statistic values surpassed 10, with an average of 22.83 and 18.57 for oral and gut microbiota. Detailed information on IVs for oral and gut microbiota are listed in Table S4 and Table S8. The estimates obtained from various MR methods are displayed in Table S5 and Table S9.

Causal effects of gut microbiota on gingivitis

Acute gingivitis

The results of IVW showed that class Negativicutes (OR: 2.2607, 95% CI 1.1617–4.3995, P = 0.016), class Verrucomicrobiae (OR: 1.6263, 95% CI 1.0034–2.636, P = 0.048), genus Butyricicoccus (OR: 2.0537, 95% CI 1.0661–3.9562, P = 0.031), genus Eubacterium (OR: 1.8914, 95% CI 1.0738–3.3315, P = 0.027), genus Lactobacillus (OR: 1.646, 95% CI 1.0522–2.5749, P = 0.029), order Selenomonadales (OR: 2.2607, 95% CI1.1617–4.3995, P = 0.016), and order Verrucomicrobiales (OR: 1.6263, 95% CI 1.0034–2.636, P = 0.048) were linked to a higher risk of acute gingivitis, while family Peptostreptococcaceae (OR: 0.5229, 95% CI 0.3068–0.8914, P = 0.017), genus Coprococcus2 (OR: 0.5207, 95% CI 0.2954–0.9179, P = 0.024), and genus Lachnospiraceae UCG001 (OR: 0.5098, 95% CI 0.3155–0.8236, P = 0.006) were linked to a lower risk of acute gingivitis (Fig. 2 and Table S5).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of causal relationship between gut and oral microbiota and gingivitis (Positive results)

In terms of sensitivity analysis, The Cochran’s Q statistic (MR-IVW) showed that the MR analyses of 12 gut microbiota and acute gingivitis had heterogeneity (P < 0.05) (Table S6). The intercept test in the MR Egger analysis revealed horizontal pleiotropy in the MR studies of six gut microbiota associations with acute gingivitis (P < 0.05), as detailed in Table S6. Similarly, the global test in the MR-PRESSO analysis indicated horizontal pleiotropy in the MR studies of 13 gut microbiota associations with acute gingivitis (P < 0.05), as shown in Table S7. The distortion test in the MR-PRESSO analysis confirmed the absence of outliers in these gut microbiota and acute gingivitis MR studies (Table S7).

Chronic gingivitis

The results of IVW showed that class Erysipelotrichia (OR: 1.3152, 95% CI (1.0241–1.689, P = 0.032), class Methanobacteria (OR: 1.2282, 95% CI1.077–1.4007, P = 0.002), class Verrucomicrobiae (OR: 1.2771, 95% CI 1.049–1.5549, P = 0.015), family Defluviitaleaceae (OR: 1.2394, 95% CI 1.0112–1.5191, P = 0.039), family Erysipelotrichaceae (OR: 1.3152, 95% CI 1.0241–1.689, P = 0.032), family Methanobacteriaceae (OR: 1.2282, 95% CI 1.077–1.4007, P = 0.002), family Verrucomicrobiaceae (OR: 1.2822, 95% CI 1.052–1.5628, P = 0.014), genus Akkermansia (OR: 1.2444, 95% CI 1.0183–1.5206, P = 0.033), genus Christensenellaceae R 7group (OR: 1.29, 95% CI 1.0072–1.6524, P = 0.044), genus Defluviitaleaceae UCG011 (OR: 1.2518, 95% CI 1.0283–1.5239, P = 0.025), genus Methanobrevibacter (OR: 1.2742, 95% CI 1.1114–1.4607, P = 0.001), genus Paraprevotella (OR: 1.2454, 95% CI 1.012–1.5327, P = 0.038), genus Senegalimassilia (OR: 1.3171, 95% CI1.0662–1.6269, P = 0.011), order Erysipelotrichales (OR: 1.3152, 95% CI 1.0241–1.689, P = 0.032), order Methanobacteriales (OR: 1.2282, 95% CI 1.077–1.4007, P = 0.002), order Verrucomicrobiales (OR: 1.2771, 95% CI 1.049–1.5549, P = 0.015), and phylum Cyanobacteria (OR: 1.2484, 95% CI 1.0363–1.5039, P = 0.020) were linked to a higher risk of chronic gingivitis, while family Clostridiales vadin BB60 group (OR: 0.7928, 95% CI 0.6549–0.9596, P = 0.017), genus Allisonella (OR: 0.8434, 95% CI (0.7405–0.9606, P = 0.010), genus Dorea (OR: 0.7673, 95% CI 0.5969–0.9863, P = 0.039), and genus Lachnospiraceae UCG004 (OR: 0.7334, 95% CI0.5764–0.933, P = 0.012) were linked to a lower risk of chronic gingivitis (Fig. 2 and Table S9).

In terms of sensitivity analysis, The Cochran’s Q statistic (MR-IVW) showed that the MR analyses of 8 gut microbiota and chronic gingivitis had heterogeneity (P < 0.05) (Table S10). The intercept test of MR Egger analysis showed that the MR analyses of 11 gut microbiota and chronic gingivitis had horizontal pleiotropy (P < 0.05) (Table S10). The global test of MR-PRESSO showed horizontal pleiotropy in MR Analyses of 11 gut microbiota and chronic gingivitis (P < 0.05) (Table S11). The distortion test of MR-PRESSO analysis showed that the MR analyses of gut microbiota and chronic gingivitis had no outliers (Table S11).

Causal effects of oral microbiota on gingivitis

The results of IVW showed that unknown Porphyromonas species (ASV0008) (OR:1.5704, 95% CI 1.0210–2.4155, P = 0.04), and Genus Porphyromonas (OR: 1.1699, 95% CI: 1.0059–1.3606, P = 0.02) were linked to a higher risk of acute gingivitis, unknown Neisseria species (ASV0004) (OR: 1.3300, 95% CI: 1.0481–1.6877, P = 0.019), and unknown Veillonella species (ASV0001) (OR: 1.1699, 95% CI: 1.0059–1.3606, P = 0.042) were linked to a higher risk of chronic gingivitis, and Class Bacilli (OR: 0.8280, 95% CI 0.6927–0.9897, P = 0.038) were linked to a lower risk of chronic gingivitis (Fig. 2 and Table S12).

In terms of sensitivity analysis, The Cochran’s Q statistic (MR-IVW) showed that the MR analyses of 6 oral microbiota and gingivitis had heterogeneity (P < 0.05) (Table S13). The intercept test in the MR Egger analysis showed that there was no horizontal multidirectionality in the MR studies on the correlation between oral microbiota and gingivitis, as detailed in Table S13. Similarly, as shown in Table S14, the global test in the MR-PRESSO analysis demonstrated horizontal pleiotropy (P < 0.05) in the MR studies of 2 oral microbiota (unknown Streptococcus species (ASV0009) and Species periodonticum) associated with gingivitis. The exclusion test in the MR-PRESSO analysis confirmed the absence of outliers in these MR studies of oral microbiota and gingivitis (Table S14).

The robustness of our findings was supported by sensitivity analyses (scatter plots, funnel plots, and leave-one-out plots), all of which aligned with the IVW results. Detailed visualization data for these analyses have been deposited in the Zenodo database (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14642359) and are publicly accessible via: https://zenodo.org/records/14642359.

Discussion

Based on our current understanding, this study represents the inaugural MR investigation exploring the potential causal links between oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis among European individuals. Our findings reveal potential causal effects between various oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis. Based on the available snapshot data (i.e., data reflecting only an individual’s current gingivitis status), we observed potential causal links between microbiome composition and gingivitis status. Specifically, nine microbiome genera were found to be positively correlated with acute gingivitis, while three were negatively correlated; meanwhile, 19 microbiome genera were positively correlated with chronic gingivitis, while five were negatively correlated, such as genus Lachnospiraceae of gut microbiota was associated with a lower risk of acute and chronic gingivitis, and unknown Porphyromonas species (ASV0008) and Genus Porphyromonas of oral and gut microbiota were positively associated with acute gingivitis. These discoveries could potentially influence public health strategies aimed at mitigating the risk of gingivitis.

MR results suggested that Genus Lachnospiraceae was negatively associated with both acute and chronic gingivitis (protective effect), suggesting that it may inhibit gingivitis. However, some clinical studies have found Lachnospiraceae to be positively associated with gingivitis [31], which we believe may reflect dysbiosis (e.g., an inflammatory environment that promotes its proliferation) rather than a causal effect in disease states. Moreover, observational studies are susceptible to reverse causal interference. MR analysis reduces the effects of confounding factors and reverse causation and provides higher-quality evidence that Lachnospiraceae may have a protective effect and reduce the risk of gingivitis. Lachnospiraceae are one of the major groups of butyrate-producing bacteria [32], and butyrate has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [33]. The pathogenesis of gingivitis involves localized immune responses (e.g., Th17/Treg imbalance) [34], and gut flora may modulate oral immunity through the “gut-oral axis”. In terms of potential biological mechanisms, first, butyrate may reduce gingival inflammation by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway [35] and decreasing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-18) in gingival tissues. Second, Lachnospiraceae may reduce gingivitis by competitively inhibiting the colonization of oral pathogenic bacteria (e.g., Porphyromonas). Alternatively, oral bacteria may enter the gut through swallowing, leading to intestinal dysbiosis, which in turn affects gingival health through immune cell transfer or metabolites (e.g., LPS). Conversely, gut flora (e.g., Lachnospiraceae) may modulate the oral immune environment through metabolites (e.g., butyrate), resulting in bidirectional regulation. On the clinical front, if the negative correlation of Lachnospiraceae is further validated, gut flora could be modulated through dietary or probiotic interventions to reduce the risk of gingivitis. For example, a diet rich in dietary fiber may promote the growth of Lachnospiraceae [36], thereby indirectly improving gingival health. And for people who are prone to gingivitis (e.g., diabetics), gut flora modulation may be an adjunctive treatment. In conclusion, despite the contradiction with the results of observational studies, the advantage of causal inference of MR makes its results more reliable. In the future, further validation of its molecular mechanism and exploration of the value of clinical application are needed to provide new strategies for the prevention and treatment of gingivitis.

Clinical observational studies showed that Verrucomicrobiae levels were elevated in the gut microbiome of patients with periodontitis compared to healthy controls, whereas Verrucomicrobiae levels did not change significantly in patients with gingivitis [37]. And MR results showed that Verrucomicrobiae was positively correlated with acute and chronic gingivitis. The MR results suggest that Verrucomicrobiae may have a contributory role in the development of gingivitis. Observational studies did not find significant changes in intestinal Verrucomicrobiae in patients with gingivitis, probably because such studies were unable to distinguish between causal and concomitant phenomena, whereas MR analyses provided a stronger basis for causal inference. The major genus of the Verrucomicrobiae phylum, Akkermansia muciniphila, uses mucin as a substrate and is involved in the regulation of intestinal barrier function [38]. Akkermansia produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [39] that are anti-inflammatory in the gut [40] but may be utilized by pathogenic bacteria in the oral cavity. Although Verrucomicrobiae is primarily found in the gut, some studies suggest that its components or metabolites may migrate to the oral cavity [41] via the bloodstream and participate in localized gingival flora structural remodeling and inflammatory cascade responses. Clinically, Verrucomicrobiae can be used as a potential gut microbial marker for gingivitis risk assessment, especially for early identification of high-risk groups. The importance of the “oral-gut axis” can be emphasized, and in the future, the combination of gastrointestinal health assessment can be considered in dental practice for a more comprehensive health management.

In addition, MR results showed that unknown Porphyromonas species (ASV0008) and Genus Porphyromonas were positively associated with acute gingivitis. Porphyromonas is a known periodontal pathogen and its increase may directly contribute to acute episodes of gingival inflammation. Unknown Neisseria species (ASV0004) and unknown Veillonella species (ASV0001) were positively associated with chronic gingivitis, while Class Bacilli was negatively associated with chronic gingivitis. Increases in Neisseria and Veillonella may have promoted the persistence of chronic inflammation, whereas decreases in Bacilli may have weakened the protective effect against gingivitis. Similar to the findings of Ohira et al., an increase in periodontal pathogenic bacteria such as Porphyromonas was strongly associated with the development of gingivitis [42]. This genus can promote acute inflammation by destroying the host immune barrier through virulence factors such as gingival proteases. The association of Neisseria spp. (ASV0004) and Veillonella spp. (ASV0001) with chronic gingivitis may reflect their role as “bridge pathogens”. The former utilizes nitrate to produce nitrite (promoting an anaerobic environment) [43], while the latter provides nutrients to periodontal pathogens through lactate metabolism [44]. This is consistent with the ecological network characterization of the chronic gingivitis microbiome identified in previous macrogenomic studies [45]. On the clinical side, monitoring changes in the oral and gut microbiomes allows early prediction of the risk of gingivitis and provides the basis for personalized prevention and treatment. Interventions targeting specific microorganisms, such as the use of probiotics or antimicrobial drugs, may become a new approach to the treatment of gingivitis. Furthermore, regulating the balance of microbiota may indirectly reduce gingival inflammation by improving the systemic immune status. Overall, even though the associations of these bacteria are known, the MR study also provides the first genetic hints of their causal relationship with gingivitis (rather than the more severe periodontitis). Of course, we recognize that this is a limitation of current sequencing technologies or databases, and that higher resolution identification of the function of these flora will be needed in the future.

In MR research, three major assumptions, namely, the assumptions of relevance, independence, and exclusivity, underlie its study. If the assumption of relevance is not met, then the selected genetic variants do not effectively represent or predict changes in the microbiome, thus weakening the basis for the use of MR methods. If the independence assumption is not met, then there may be confounding factors interfering with the results of the study, making it possible that associations between genetic variants and disease may be due to these confounding factors rather than a true causal effect. However, when the exclusionary restriction assumption is not met, it implies that there are pathways other than exposure factors that allow genetic variation to influence the results, which introduces bias and may lead to erroneous conclusions.

Future research should aim to gain a deeper understanding of how the aforementioned microorganisms specifically contribute to the development of gingivitis, including their metabolic pathways, interactions with host cells, and so on. In addition, longitudinal studies are needed to validate current cross-sectional results and to explore whether the presence of these microbes can be modified by interventions to improve gingival health. Meanwhile, research on personalized healthcare protocols is also an important direction, taking into account the differences in microbial composition between individuals.

A notable strength of this study lies in its application of the MR method, which effectively mitigates the impact of reverse causality and confounding variables. More importantly, this study explores the causal relationship between oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis at the genetic level, covering the broadest population, and is more practical and convincing than traditional observational epidemiological studies. There are also some limitations to this study. Firstly, the analysis of bacterial taxa was confined to the genus level, rather than more specialized classifications such as species or strains, owing to the restricted data accessible in the GWAS database. Secondly, the SNPs selected in this study have the potential to be inconsistent in their effects on traits, making it difficult to select appropriate IVs to act as true proxies for exposure. Therefore, research into the function of SNPs may be needed to help explain the genetic characteristics of oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis, and to facilitate the selection of more precise IVs. Furthermore, confounding factors associated with acute gingivitis include hormonal changes, stress, and host immunity, which have not been excluded from the current study, which may have biased the analysis. Finally, the genetic evaluation of the effect of oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis in this study ignores the influence degree of environmental factors, which may only partially explain the effect of oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis. In addition, although the removal of outliers eliminates horizontal pleiotropy, heterogeneity may still interfere with the interpretation of results by masking true causal effects or amplifying false-positive associations. In particular, heterogeneity may reflect the heterogeneous effects of different microbial subpopulations or host genetic backgrounds, leading to biased effect estimates.

Conclusions

The current MR analysis validated the causal links between oral and gut microbiota and gingivitis. Our study suggests that in the future it may be possible to develop diagnostic tools or therapeutic strategies based on oral and gut microbiota to prevent and treat gingivitis in European. However, additional research is necessary to reinforce the findings of our study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- MR

Mendelian randomization

- IVW

Inverse-variance weighted

- SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- IV

Instrumental variable

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

Author contributions

Jichao lin carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, study design, and drafted the manuscript and Qingjiang Xu participated in statistic analysis and drafted the manuscript. Qinglian Wang, Wei Bi and Youcheng Yu participated in study design and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Xiamen, China (Grant No. 3502Z202373085).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The original data used in this study, including the gut microbiota and cohort data as well as the analysis results, have been uploaded to the Zenodo database with the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14642359. The data can be accessed via the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/14642359.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Page RC, Gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:345–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murakami S, Mealey BL, Mariotti A, Chapple ILC. Dental plaque-induced gingival conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blicher B, Joshipura K, Eke P. Validation of self-reported periodontal disease: a systematic review. J Dent Res. 2005;84:881–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh T-J, Eber R, Wang H-L. Periodontal diseases in the child and adolescent. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century–the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2003;31 Suppl 1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kashetty M, Kumbhar S, Patil S, Patil P. Oral hygiene status, gingival status, periodontal status, and treatment needs among pregnant and nonpregnant women: A comparative study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2018;22:164–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rakchanok N, Amporn D, Yoshida Y, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Sakamoto J. Dental caries and gingivitis among pregnant and non-pregnant women in Chiang mai, Thailand. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2010;72:43–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Stefano M, Polizzi A, Santonocito S, Romano A, Lombardi T, Isola G. Impact of oral Microbiome in periodontal health and periodontitis: A critical review on prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:426–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam GA, Albarrak H, McColl CJ, Pizarro A, Sanaka H, Gomez-Nguyen A, et al. The Oral-Gut axis: periodontal diseases and Gastrointestinal disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanisic D, Jovanovic M, George AK, Homme RP, Tyagi N, Singh M, et al. Gut microbiota and the periodontal disease: role of hyperhomocysteinemia. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021;99:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SY, Hwang BO, Lim M, Ok SH, Lee SK, Chun KS et al. Oral-Gut Microbiome Axis in Gastrointestinal disease and Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Domokos Z, Uhrin E, Szabó B, Czumbel ML, Dembrovszky F, Kerémi B, et al. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease have a higher chance of developing periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greuter T, Vavricka SR. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease - epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baima G, Ferrocino I, Del Lupo V, Colonna E, Thumbigere-Math V, Caviglia GP, et al. Effect of periodontitis and periodontal therapy on oral and gut microbiota. J Dent Res. 2024;103:359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu X. Mendelian randomization and Pleiotropy analysis. Quant Biology (Beijing China). 2021;9:122–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S, Mendelian Randomization. JAMA. 2017;318:1925–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li P, Wang H, Guo L, Gou X, Chen G, Lin D, et al. Association between gut microbiota and preeclampsia-eclampsia: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. 2022;20:443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehm FJ, Zhou X. Statistical methods for Mendelian randomization in genome-wide association studies: A review. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:2338–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, Radjabzadeh D, Wang J, Demirkan A, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut Microbiome composition. Nat Genet. 2021;53:156–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stankevic E, Kern T, Borisevich D, Poulsen CS, Madsen AL, Hansen TH, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies host genetic variants influencing oral microbiota diversity and metabolic health. Sci Rep. 2024;14:14738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poulsen CS, Nygaard N, Constancias F, Stankevic E, Kern T, Witte DR, et al. Association of general health and lifestyle factors with the salivary microbiota - Lessons learned from the ADDITION-PRO cohort. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1055117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekula P, Del Greco MF, Pattaro C, Köttgen A. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3253–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H, Zhang Y, Li S, Tao Y, Gao R, Xu W, et al. The association between genetically predicted systemic inflammatory regulators and polycystic ovary syndrome: A Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:731569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:755–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiol (Cambridge Mass). 2017;28:30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal Pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1985–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbanck M, Chen C-Y, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal Pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kistler JO, Booth V, Bradshaw DJ, Wade WG. Bacterial community development in experimental gingivitis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang CJ, Chang HC, Sung PC, Ge MC, Tang HY, Cheng ML, et al. Oral fecal transplantation enriches Lachnospiraceae and butyrate to mitigate acute liver injury. Cell Rep. 2024;43:113591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li G, Lin J, Zhang C, Gao H, Lu H, Gao X, et al. Microbiota metabolite butyrate constrains neutrophil functions and ameliorates mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1968257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Wang X, Lu S, Lv H, Zhao T, Xie G, et al. Metabolic disturbance and Th17/Treg imbalance are associated with progression of gingivitis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:670178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei H, Yu C, Zhang C, Ren Y, Guo L, Wang T, et al. Butyrate ameliorates chronic alcoholic central nervous damage by suppressing microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and modulating the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;160:114308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hao Y, Ji Z, Shen Z, Xue Y, Zhang B, Yu D, et al. Increase dietary Fiber intake ameliorates cecal morphology and drives cecal Species-Specific of Short-Chain fatty acids in white Pekin ducks. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:853797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lourenςo TGB, Spencer SJ, Alm EJ, Colombo APV. Defining the gut microbiota in individuals with periodontal diseases: an exploratory study. J Oral Microbiol. 2018;10:1487741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu W, Kaicen W, Bian X, Yang L, Ding S, Li Y, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila alleviates high-fat-diet-related metabolic-associated fatty liver disease by modulating gut microbiota and bile acids. Microb Biotechnol. 2023;16:1924–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Z, Huang S, Li T, Li N, Han D, Zhang B, et al. Gut microbiota from green tea polyphenol-dosed mice improves intestinal epithelial homeostasis and ameliorates experimental colitis. Microbiome. 2021;9:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 2011;3:858–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geerlings SY, Kostopoulos I, de Vos WM, Belzer C. Akkermansia muciniphila in the human Gastrointestinal tract: when, where, and how? Microorganisms. 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Ohira C, Kaneki M, Shirao D, Kurauchi N, Fukuyama T. Oral treatment with Catechin isolated from Japanese green tea significantly inhibits the growth of periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gulae and ameliorates the gingivitis and halitosis caused by periodontal disease in cats and dogs. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;146:113805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willmott T, Serrage HJ, Cottrell EC, Humphreys GJ, Myers J, Campbell PM, et al. Investigating the association between nitrate dosing and nitrite generation by the human oral microbiota in continuous culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2024;90:e0203523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wicaksono DP, Washio J, Abiko Y, Domon H, Takahashi N. Nitrite production from nitrate and its link with lactate metabolism in oral Veillonella spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Cheng X, Shen S. Identification of key genes in periodontitis. Front Genet. 2025;16:1579848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The original data used in this study, including the gut microbiota and cohort data as well as the analysis results, have been uploaded to the Zenodo database with the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14642359. The data can be accessed via the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/14642359.