Abstract

Background

Real-world data on multiple myeloma (MM) outside Europe and North America are limited. The INTEGRATE study retrospectively assessed real-world treatment pathways and outcomes in MM from Argentina, China, South Korea, South Africa, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, and Türkiye.

Methods

Medical records (2010–2011) of patients (≥ 18 years) with newly diagnosed MM were analyzed. The primary endpoint was time to next treatment (TTNT). Secondary endpoints included treatment pathways and clinical outcomes stratified by stem cell transplantation (SCT).

Results

Of 1511 patients analyzed (median age: 59.5 years), 32% had IgG kappa MM and 35.9% had International Staging System stage III disease. Bortezomib- and thalidomide-based chemotherapy regimens were the most common first- and second-line treatments; lenalidomide-based regimens were common in later lines. Median TTNT from initiation of first-line treatment was 39.5 months. Only 31.7% of patients received SCT at diagnosis, with improved outcomes versus those without SCT (median overall survival: 114.1 vs 85.9 months; 5-year relapse-free rates after first-line treatment: 58.2% vs 49.3%).

Conclusion

Treatment strategies for MM outside Europe and North America align with guideline recommendations. More effective treatments and SCT at treatment initiation are needed. This study can guide future research in these regions utilizing newer treatment options.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12185-025-03972-8.

Keywords: Hematological malignancy, Treatment outcomes, Developing countries, Stem cell transplantation, Real-world evidence

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM), the second most common hematological malignancy, affects plasma cells [1, 2]. The discovery of new immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors (e.g., carfilzomib, ixazomib, pomalidomide, etc.) in the last decade has significantly changed the treatment landscape in MM [1, 2]. Additionally, novel therapies like CAR-T cell therapies and monoclonal antibodies have further improved outcomes in MM [3]. However, such developments have also added complexity to the selection of an optimal treatment strategy at first and subsequent lines, as well as the best sequence of agents to use.

Despite the availability of novel agents, MM remains mostly incurable, with several challenges including disease heterogeneity, delayed diagnosis, poor outcomes, and patient resistance to multiple drug classes [3]. The unclear influence of disease symptoms and treatment-related toxicities on the use of effective novel therapies, especially in later lines of treatment, identifying the most efficient combination of novel agents in induction and maintenance regimens, and defining the best therapeutic strategies according to risk stratification and patient characteristics, are unmet challenges in MM management [3, 4]. In developing regions, these challenges are further complicated by limited access to novel treatments, often due to cost and resource limitations [5, 6].

Information on the current real-world management of MM is limited, especially in regions outside Europe and North America [7–12]. The available real-world studies from developing regions are limited by sample sizes, center participation, and data quality [13–16]. The INTEGRATE study was conducted in patients with MM to collect information on diagnosis, treatment pathways, the proportion of stem cell transplantation (SCT), and real-world outcomes in regions outside Europe and North America. Data from patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) are presented here.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

The INTEGRATE study is an international, multicenter, observational, retrospective study of patients with MM. Forty-five sites from eight countries (Argentina, China, Republic of Korea, Republic of South Africa, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, and Türkiye) were included. China, Republic of Korea, and Taiwan were grouped together as East Asia for the purpose of this analysis. Participating centers were selected based on physician interest, resource availability, start-up information, and accessibility to a defined minimum dataset (patient characteristics, diagnosis, treatment information, clinical outcomes, and adverse events [AEs]) for all patients. All centers were required to have specialist MM treatment departments, access to complete treatment journey of patients, appropriate personnel to collect data, electronic data capture system, adequate sample size, and adequate means to systematically identify eligible patients for study inclusion. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. The relevant independent ethics committees/institutional review boards at each center approved the study and patients provided written informed consent (Supplementary methods).

All included patients were ≥ 18 years, alive or deceased at the time of retrospective data extraction, and diagnosed with MM between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2011 (Supplementary material S1A). All patients were required to have completed at least one full line of treatment. Patients with smoldering myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, participation in an interventional clinical trial during the study period, or without the minimum study dataset were excluded.

Pseudo-anonymized data were collected from March 21, 2018, to March 29, 2021, using a standardized web-based electronic case report form and assessed for random selection, pooled analysis, and reporting. Data were collected from the date of diagnosis until the death of the patient or the date when the patient was last known to be alive, whichever occurred first.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was time to next treatment (TTNT) in patients with MM. TTNT was defined as the time (in months) from the date of initiation of each line of treatment to the date of initiation of the next line of treatment or death in each patient.

Secondary endpoints included patients undergoing and not undergoing SCT, median duration of treatment, median overall survival (OS), best clinical response to each line of treatment according to the International Myeloma Working Group 2016 criteria, documented relapse or disease progression rates after start of first-line treatment, OS and relapse-free rates at 1, 2, and 5 years after start of first-line treatment and SCT, and AEs (assessed by severity and line of treatment).

Statistical analysis

The results were presented for the overall sample and at individual country/regional level. Baseline characteristics, treatment pathways, clinical outcomes, and AEs were presented as summary statistics. Categorical endpoints were summarized with frequency distributions (number, %) using only non-missing data for a particular variable. Continuous variables were summarized using measures of central tendency (median) and spread (range or interquartile range [IQR]). The TTNT after each line of treatment was summarized using the Kaplan–Meier method. The association between TTNT or death with time and the potential covariates/factors were assessed using the Cox model, where hazard ratios, the respective 95% confidence intervals (CI), and P-values were presented. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS®) Software, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the 2087 enrolled patients, 1855 were eligible for the study and 213 were excluded due to ineligibility (Supplementary material S1B). A total of 1511 patients with NDMM (Table 1) involving 59 from Argentina, 565 from East Asia, 387 from Russia, 48 from Saudi Arabia, 104 from South Africa, and 348 from Türkiye (Supplementary material S1B) were analyzed. The remaining patients were diagnosed with relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM) during the study period and were analyzed separately, whose results are outside the scope of this manuscript.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics by SCT status in patients with NDMM

| Characteristica | Overall (N = 1511) | SCT (n = 479) | Non-SCT (n = 987) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at MM diagnosis, years (range) | 59.5 (24.4–97.3) | 54.7 (24.4–73.8) | 63.1 (26.8–97.3) |

| Median age at first-line treatment | 59.6 (24.5–97.3) | 54.8 (24.5–73.8) | 63.1 (26.9–97.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 765 (50.6) | 261 (54.5) | 478 (48.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 758 (50.2) | 207 (43.2) | 518 (52.5) |

| Asian | 572 (37.9) | 169 (35.3) | 396 (40.1) |

| Black or African American | 51 (3.4) | 15 (3.1) | 34 (3.4) |

| Otherb | 67 (4.4) | 37 (7.7) | 28 (2.8) |

| Type of myeloma, n (%) | |||

| IgG kappa | 484 (32.0) | 142 (29.6) | 332 (33.6) |

| IgG lambda | 239 (15.8) | 77 (16.1) | 159 (16.1) |

| IgG (light chain unknown) | 55 (3.6) | 11 (2.3) | 43 (4.4) |

| IgA kappa | 148 (9.8) | 43 (9.0) | 104 (10.5) |

| IgA lambda | 97 (6.4) | 37 (7.7) | 58 (5.9) |

| IgA (light chain unknown) | 13 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 12 (1.2) |

| IgD | 10 (0.7) | 4 (0.8) | 6 (0.6) |

| IgM | 14 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) | 12 (1.2) |

| IgE | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Light chain alone (kappa or lambda) | 235 (15.6) | 82 (17.1) | 151 (15.3) |

| ISS stage at diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Stage I | 193 (18.4) | 88 (22.9) | 100 (15.9) |

| Stage II | 293 (27.9) | 100 (26.0) | 189 (30.1) |

| Stage III | 377 (35.9) | 119 (30.9) | 252 (40.1) |

| Unknown | 185 (17.6) | 78 (20.3) | 84 (13.4) |

| Patients with plasmacytoma, n (%) | 314 (20.8) | 116 (24.2) | 195 (19.8) |

| Patients meeting criteria for CRAB, n (%) | 1508 (99.8) | 476 (99.4) | 987 (100.0) |

| Calcium elevated, n (%) | 101 (6.7) | 38 (8.0) | 62 (6.3) |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 246 (16.3) | 78 (16.4) | 163 (16.5) |

| Anemia, n (%) | 867 (57.5) | 235 (49.4) | 609 (61.7) |

| Any bone lesions, n (%) | 1231 (81.6) | 388 (81.5) | 811 (82.2) |

| 0 sites | 185 (15.0) | 49 (12.7) | 131 (16.1) |

| 1–3 sites | 533 (43.3) | 182 (47.0) | 336 (41.4) |

| > 3 sites | 452 (36.7) | 127 (32.8) | 321 (39.5) |

For 45 patients with NDMM, the status of SCT at MM diagnosis was reported as ‘unknown’. Therefore, the data for these 45 patients are not included in the SCT or non-SCT cohorts

CRAB calcium (elevated), renal failure, anemia, bone lesions, IgA immunoglobulin A, IgD immunoglobulin D, IgE immunoglobulin E, IgG immunoglobulin G, IgM immunoglobulin M, ISS International Staging System, MM multiple myeloma, NDMM newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, SCT stem cell transplantation

aBaseline characteristics were recorded at the time of MM diagnosis

bOthers include American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or another Pacific Islander, and other ethnicities

Patient baseline characteristics

Overall, the median age at MM diagnosis was 59.5 years, IgG kappa was the most common type of myeloma (32.0%), International Staging System (ISS) Stage III disease was the most common stage (35.9%), and most patients had bone lesions (81.5%) (Table 1). Most patient baseline characteristics were similar across the different countries (Supplementary material S2). Of note, the proportion of females was higher than males in Argentina (54.2%) and Russia (59.7%), most patients in Argentina had ISS Stage I disease (45.3%), and a higher proportion of patients in East Asia had only light chain myeloma (24.2%).

Treatment pathways

First-line SCT

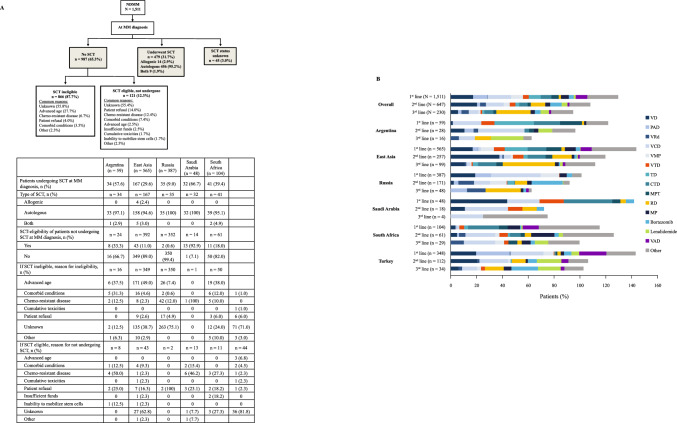

Only 479 (31.7%) patients of the 1511 patients with NDMM underwent SCT, while 987 (65.3%) did not have SCT and 45 (3.0%) reported an undisclosed status regarding SCT (Fig. 1A). The proportion of patients with NDMM undergoing first-line SCT was highest in Saudi Arabia (32/48, 66.7%) followed by Argentina (34/59, 57.6%), and was lowest in Russia (35/387, 9.0%). Of the 987 patients who did not have first-line SCT, most were SCT-ineligible (87.7%). The reason for SCT ineligibility was not known in 55.8% of the SCT-ineligible patients with NDMM, while it was advanced age in most of the remaining SCT-ineligible patients. Additionally, 12.3% of SCT-eligible patients did not undergo first-line SCT, although the reason for this was unknown in 55.4% of patients. Patient refusal and chemo-resistance were the next most common reasons for patients to not receive SCT.

Fig. 1.

Treatment patterns in patients with NDMM. A SCT pattern during MM diagnosis, overall (flowchart) and by region (table). B Most common (frequency ≥ 10%) chemotherapy regimens in the first three lines of treatment, overall and by region. CTD cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, dexamethasone, MM multiple myeloma, MP melphalan, prednisone, MPT melphalan, thalidomide, prednisone, NDMM newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, PAD bortezomib, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, RD lenalidomide, dexamethasone, SCT stem cell transplantation, TD thalidomide, dexamethasone, VAD vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, VCD bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, VD bortezomib, dexamethasone, VMP bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone, VRd bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, VTD bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone

Treatment distribution

All patients with NDMM received first-line treatment. However, the proportion of patients receiving subsequent lines of treatment decreased with each subsequent line of therapy (Fig. 1B). Bortezomib- and thalidomide-based chemotherapy regimens were the most common first- and second-line treatments, respectively (Fig. 1B). Bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, plus dexamethasone (VCD) and bortezomib plus dexamethasone (VD) were the most common first- (18.3%) and second-line regimens (20.4%), respectively. Lenalidomide-based regimens (lenalidomide and dexamethasone [RD]) were the most common chemotherapy regimens in later lines of treatment. This observation was consistent across all participating regions except Argentina, where thalidomide-based regimens were more common during the earlier lines of treatment. Treatment completion and disease progression were reported as the two main reasons for treatment change after first-, second-, and third-line treatment. Additionally, toxicity was reported as a common reason (8.0%, n = 21) for treatment change during first-line treatment with VD in patients with NDMM. The overall median durations of treatment across the first three lines of treatment in patients with NDMM were generally similar (first-line: 6.0 [IQR: 3.7–10.4], second-line: 6.4 [IQR: 3.2–11.9], and third-line: 6.6 [IQR: 3.3–9.6] months) and this was generally consistent across the regions (Supplementary material S3).

TTNT and treatment-free interval

The overall median (95% CI) TTNT from initiation of first-line treatment in patients with NDMM was 39.5 (37.6–42.6) months (Fig. 2A) and the treatment-free interval (TFI) after first-line treatment was 33.5 months (Supplementary material S4). Median TTNT and TFI decreased with subsequent lines of treatment. The TFI between the first-line and second-line treatments were longer in patients undergoing SCT compared with non-SCT patients. Median TTNT from initiation of first-line treatment for NDMM varied across the regions and was lowest in South Africa for all lines of treatment (Fig. 2B–G). In a risk factor analysis, significantly shorter TTNT was observed in the following subgroups of patients with NDMM: Asian ethnicity, no SCT performed at first-line, and ISS Stage II/III (all P ≤ 0.022).

Fig. 2.

TTNT for different lines of treatment in patients with NDMM. A Overall, B Argentina, C East Asia, D Russia, E Saudi Arabia, F South Africa and G Türkiye. Patients who did not start the next line of treatment and were alive at that time were censored at the last known date to be alive at the time of data extraction. CI confidence interval, NDMM newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, NR not reached, TTNT time to next treatment

Clinical outcomes

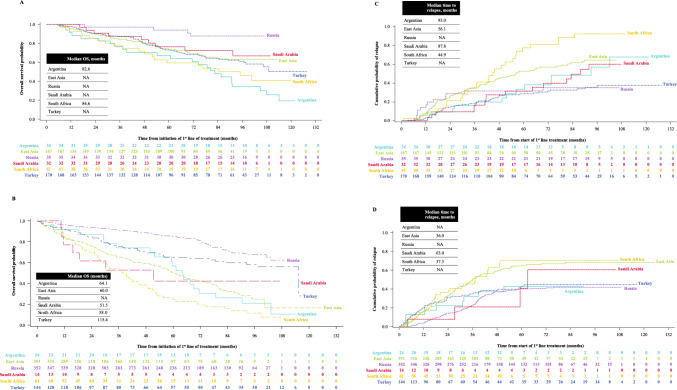

Most patients with NDMM achieved complete, very good partial, or partial responses after the first two lines of treatment (Table 2). The clinical responses tended to decline with subsequent lines of treatment. All clinical outcomes were better in patients undergoing SCT than in those without SCT. The 5-year OS and relapse-free rates after first-line treatment in patients undergoing SCT and those without SCT were 73.5% vs 64.6%, and 58.2% vs 49.3%, respectively. The median OS and median time to cumulative probability of relapse after first-line treatment were longer in patients undergoing SCT than in those without SCT (Fig. 3). The median OS in patients undergoing SCT was 114.1 months (IQR 55.7–NR) and in non-SCT patients was 85.9 months (IQR 38.7–NR). The clinical outcomes in the different regions were consistent with those of the overall results.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes by SCT status in patients with NDMM, overall and by region

| Overall (N = 1511) | Argentina (n = 59) | East Asia (n = 565) | Russia (n = 387) | Saudi Arabia (n = 48) | South Africa (n = 104) | Türkiye (n = 348) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCT (n = 479) | Non-SCT (n = 987) | SCT (n = 34) | Non-SCT (n = 24) | SCT (n = 167) | Non-SCT (n = 392) | SCT (n = 35) | Non-SCT (n = 352) | SCT (n = 32) | Non-SCT (n = 14) | SCT (n = 41) | Non-SCT (n = 61) | SCT (n = 170) | Non-SCT (n = 144) | |

| Best clinical response to first-line treatment, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| sCR | 15 (3.1) | 10 (1.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 7 (4.2) | 5 (1.3) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (1.1) | 5 (15.6) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| CR | 146 (30.5) | 195 (19.8) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (12.5) | 48 (28.7) | 66 (16.8) | 18 (51.4) | 78 (22.2) | 23 (71.9) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (4.9) | 10 (16.4) | 51 (30.0) | 36 (25.0) |

| VGPR | 109 (22.8) | 193 (19.6) | 18 (52.9) | 7 (29.2) | 44 (26.3) | 78 (19.9) | 3 (8.6) | 92 (26.1) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (14.3) | 14 (34.1) | 8 (13.1) | 28 (16.5) | 6 (4.2) |

| PR | 138 (28.8) | 245 (24.8) | 8 (23.5) | 8 (33.3) | 55 (32.9) | 113 (28.8) | 7 (20.0) | 77 (21.9) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (14.3) | 22 (53.7) | 13 (21.3) | 44 (25.9) | 32 (22.2) |

| MR | 4 (0.8) | 27 (2.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) | 16 (4.1) | 0 | 4 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (4.2) |

| SD | 22 (4.6) | 136 (13.8) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (12.5) | 8 (4.8) | 55 (14.0) | 1 (2.9) | 62 (17.6) | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (4.9) | 9 (5.3) | 12 (8.3) |

| PD | 3 (0.6) | 67 (6.8) | 0 | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 24 (6.1) | 0 | 17 (4.8) | 0 | 6 (42.9) | 1 (2.4) | 16 (26.2) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.4) |

| Best clinical response to second-line treatment, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| sCR | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 2 (14.3) | 0 | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| CR | 52 (25.9) | 87 (20.2) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (7.1) | 23 (25.6) | 14 (8.5) | 4 (36.4) | 53 (33.1) | 5 (38.5) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (5.7) | 13 (27.1) | 15 (28.8) |

| VGPR | 40 (19.9) | 103 (24.0) | 7 (50.0) | 3 (21.4) | 17 (18.9) | 31 (18.8) | 5 (45.5) | 66 (41.3) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 5 (20.0) | 0 | 6 (12.5) | 2 (3.8) |

| PR | 42 (20.9) | 78 (18.1) | 0 | 2 (14.3) | 24 (26.7) | 35 (21.2) | 1 (9.1) | 24 (15.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0 | 9 (36.0) | 13 (37.1) | 4 (8.3) | 4 (7.7) |

| MR | 9 (4.5) | 12 (2.8) | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 7 (7.8) | 5 (3.0) | 0 | 3 (1.9) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (3.8) |

| SD | 12 (6.0) | 36 (8.4) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (21.4) | 6 (6.7) | 24 (14.5) | 0 | 6 (3.8) | 0 | 0 | 5 (20.0) | 3 (8.6) | 0 | 0 |

| PD | 12 (6.0) | 41 (9.5) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (6.7) | 21 (12.7) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 15 (42.9) | 2 (4.2) | 0 |

| Best clinical response to third-line treatment, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| sCR | 3 (3.8) | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CR | 13 (16.3) | 47 (32.4) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (13.2) | 4 (6.7) | 1 (50.0) | 36 (78.3) | 0 | 0 | 4 (22.2) | 0 | 2 (20.0) | 6 (28.6) |

| VGPR | 11 (13.8) | 15 (10.3) | 4 (36.4) | 0 | 5 (13.2) | 7 (11.7) | 0 | 6 (13.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| PR | 20 (25.0) | 22 (15.2) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (40.0) | 13 (34.2) | 17 (28.3) | 0 | 1 ( 2.2) | 1 (100) | 0 | 5 (27.8) | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 0 |

| MR | 5 (6.3) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 5 (13.2) | 2 (3.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SD | 6 (7.5) | 16 (11.0) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (7.9) | 8 (13.3) | 0 | 2 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 5 (45.5) | 0 | 0 |

| PD | 9 (11.3) | 18 (12.4) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (13.2) | 10 (16.7) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 2 (100) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (27.3) | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| Patients with any documented clinical response from first-line treatment, n (%) | 423 (88.3) | 727 (73.7) | 34 (100) | 19 (79.2) | 159 (95.2) | 293 (74.7) | 30 (85.7) | 288 (81.8) | 32 (100) | 8 (57.1) | 39 (95.1) | 35 (57.4) | 129 (75.9) | 84 (58.3) |

| Median time difference between first response and first relapse/disease progression (IQR), months | 24.7 (10.2–46.3) | 10.8 (1.3–26.9) | 47.7 (9.9–65.8) | 1.0 (0.3–20.9) | 22.3 (10.5–42.3) | 5.7 (1.0–19.0) | 7.9 (3.6–15.1) | 23.6 (9.1–33.0) | 39.0 (28.7–76.9) | 26.8 (-8.5–59.2) | 30.1 (16.6–48.5) | 10.2 (1.0–25.3) | 19.6 (9.1–41.1) | 2.8 (1.3–18.5) |

| Any documented relapse or disease progression after first-line treatment, n (%) | 207 (43.2) | 434 (44.0) | 14 (41.2) | 10 (41.7) | 89 (53.3) | 184 (46.9) | 12 (34.3) | 138 (39.2) | 15 (46.9) | 9 (64.3) | 28 (68.3) | 42 (68.9) | 49 (28.8) | 51 (35.4) |

| Relapse-free rate post first-line treatment, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||||||

| 1-year | 94.2 (91.7–96.0) | 88.4 (86.1–90.3) | 93.9 (77.9–98.4) | 87.1 (65.2–95.7) | 92.6 (87.3–95.7) | 84.3 (79.8–87.8) | 85.7 (69.0–93.8) | 96.2 (93.6–97.8) | 100 (100–100) | 92.3 (56.6–98.9) | 92.6 (78.7–97.5) | 83.3 (71.1–90.6) | 97.0 (92.9–98.7) | 80.1 (72.2–86.0) |

| 2-year | 80.5 (76.5–83.8) | 75.5 (72.4–78.3) | 90.7 (73.8–96.9) | 78.0 (54.8–90.2) | 73.8 (66.2–80.0) | 67.3 (61.6–72.5) | 71.2 (53.1–83.4) | 86.2 (82.0–89.5) | 90.5 (73.4–96.8) | 92.3 (56.6–98.9) | 78.6 (61.5–88.7) | 63.7 (49.4–75.0) | 85.4 (78.8–90.0) | 68.8 (59.6–76.4) |

| 5-year | 58.2 (53.2–62.9) | 49.3 (45.4–53.1) | 66.4 (44.6–81.3) | 57.2 (33.4–75.3) | 47.2 (38.8–55.1) | 35.6 (29.1–42.0) | 68.2 (50.0–81.0) | 60.0 (54.0–65.4) | 68.4 (47.8–82.2) | 59.3 (15.7–86.3) | 22.3 (9.30–38.8) | 29.4 (15.5–44.8) | 71.4 (63.1–78.2) | 57.1 (46.5–66.3) |

| Relapse-free rate post first SCT, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||||||

| 1-year | 85.2 (81.6–88.2) | – | 90.3 (72.8–96.8) | - | 79.6 (72.4–85.1) | - | 77.1 (59.5–87.9) | - | 93.6 (76.9–98.4) | - | 88.9 (73.0–95.7) | - | 89.1 (83.1–93.1) | - |

| 2-year | 74.3 (69.9–78.2) | – | 83.1 (63.9–92.6) | - | 66.2 (58.1–73.1) | - | 68.2 (50.0–81.0) | - | 86.9 (68.8–94.9) | - | 68.2 (49.9–81.0) | - | 81.1 (73.8–86.6) | - |

| 5-year | 54.9 (49.8–59.8) | – | 60.4 (38.2–76.7) | - | 45.4 (37.0–53.4) | - | 65.0 (46.6–78.4) | - | 60.2 (39.4–75.9) | - | 21.7 (8.94–38.0) | - | 68.3 (59.5–75.6) | - |

| Median OS (95% CI) | 114.1 (106.2–NR) | 85.9 (79.2–97.1) | 82.6 (54.3–104.8) | 64.1 (49.8–71.5) | NR | 60.0 (54.7–68.1) | NR | NR | NR (91.4–NR) | 51.4 (11.7–NR) | 84.6 (52.0–NR) | 38.0 (27.6–48.5) | NR (97.7– NR) | 115.4 (82.1–NR) |

| OS rate after start of first-line treatment, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||||||

| 1-year | 96.2 (94.0–97.6) | 90.1 (88.1–91.9) | 91.2 (75.1–97.1) | 91.5 (70.0–97.8) | 95.1 (90.5–97.5) | 84.2 (80.0–87.6) | 100 (100–100) | 96.6 (94.1–98.0) | 100 (100–100) | 76.9 (44.2–91.9) | 92.7 (79.0–97.6) | 85.2 (73.6–92.0) | 97.6 (93.8–99.1) | 92.8 (87.1–96.1) |

| 2-year | 89.7 (86.6–92.1) | 83.5 (81.0–85.8) | 85.3 (68.2–93.6) | 87.1 (65.2–95.7) | 89.4 (83.5–93.3) | 75.9 (71.0–80.1) | 97.1 (80.9–99.6) | 93.7 (90.6–95.8) | 100 (100–100) | 61.5 (30.8–81.8) | 85.3 (70.2–93.1) | 70.0 (56.6–79.9) | 90.3 (84.6–93.9) | 84.5 (76.9–89.7) |

| 5-year | 73.5 (69.1–77.4) | 64.6 (61.2–67.9) | 67.1 (48.4–80.2) | 56.6 (34.4–73.8) | 73.7 (65.9–80.0) | 50.5 (44.2–56.4) | 93.9 (77.8–98.4) | 85.2 (80.8–88.6) | 91.7 (53.9–98.8) | 42.2 (14.9–67.7) | 59.4 (41.5–73.4) | 26.2 (15.7–38.0) | 72.9 (65.0–79.3) | 65.0 (55.2–73.1) |

There were 45 patients with NDMM (Argentina: 1, East Asia: 6, Saudi Arabia: 2, South Africa: 2, Türkiye: 34), in whom the status of SCT at MM diagnosis was reported as ‘unknown’ and these are not included in the above table

CI confidence interval, CR complete response, IQR interquartile range, MR minimal response, NDMM newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, NR not reached, OS overall survival, PD progressive disease, PR partial response, sCR stringent complete response, SCT stem cell transplantation, SD stable disease, VGPR very good partial response

Fig. 3.

Overall survival and relapse probability in patients with NDMM by SCT status. A Overall survival in patients undergoing SCT. B Overall survival in non-SCT patients. C Probability of relapse in patients undergoing SCT. D Probability of relapse in non-SCT patients. NA not available, NDMM newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, OS overall survival, SCT stem cell transplantation

A comparative summary of the treatment regimen choices and clinical outcomes in the current study and other real-world studies from developed and developing regions is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the INTEGRATE study with other real-world studies in MM

| Study | Study type | Study period | Study region | Follow-up duration | Patient type | Sample size | Age | Proportion of SCT | Treatment choice | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed regions: USA, Europe, Japan | ||||||||||

| He et al. [12] | Retrospective review of US-SEER and Optum databases | 2007–2018 | US | NA | NDMM with no transplant | 17,731 | Mean: 71 years | 0 | Bortezomib- and lenalidomide-based |

OS range: 56.3–112.6 months TTNT range: 7–24.3 months |

| Cejalvo et al. [18] | Retrospective analysis | NA | Spain | NA | Transplant-ineligible NDMM | 675 | Mean: 75.6 years | SCT-ineligible | First-line: non-VMP bortezomib-based | Median OS: 33.5 months (95% CI 29.1–37.2) |

| Remes et al. [20] | Retrospective, observational study of Finnish Hematology Registry | 2009–2013 | Finland | Median: 25 months | NDMM | 321 | Median: 66.0 years | NA | Conventional (n = 46) vs ASCT-novel (n = 114) vs non-SCT-novel (n = 161) |

Median OS: Conventional: 25.6 months Non-SCT-novel: 46.2 months ASCT-novel: NR Median TTNT: Conventional: 7.8 months Non-SCT-novel: 12.6 months SCT-novel: 33.9 months |

| Hajek et al. [32] | Noninterventional, observational, retrospective analysis of prospectively collected patient medical record | 2007–2014 | Czech | NA | NDMM and RRMM | 2446 | NA | NA | Bortezomib-, thalidomide-, and lenalidomide-based |

Median OS: 50.3 months OS, PFS, and depth of response decreased with subsequent lines of treatment |

| Mohty et al. [10] | Prospective, non-interventional study | 2010–2012 | Europe (several countries), Türkiye, Israel, South Africa | NA | NDMM and RRMM | 2358 | Median: 63.0 years | n = 775 | Bortezomib-, thalidomide-, and lenalidomide-based |

First-line bortezomib or thalidomide/lenalidomide: SCT: ORR: > 85%, VGPR: > 50% Non-SCT: ORR: 64–85%, VGPR: 24–53% First-line other regimen: SCT: ORR: 71%, VGPR: 29% Non-SCT: ORR: 51%, VGPR: 10% |

| Yong et al. [11] | Observational cross-sectional and retrospective patient chart review | 2014 | Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and UK | 12 months in the past year | MM | 4997 | > 65 years: 64% | Not stated |

Bortezomib- and thalidomide-based regimens common in first-line and lenalidomide-based regimens in third-line Median duration of 1L treatment – 6 months |

Median treatment-free interval: 10 months VGPR: 74% for 1L vs 11% for 5L Clinical outcomes better with SCT vs no SCT (P < 0.001 for treatment-free interval and complete response) |

| Akizuki et al. [17] | Retrospective study | 2010–2018 | Japan | 32.8 months | NDMM | 284 | Median: 71 years | 16.5% | 80% received novel agents (51.8% received bortezomib-based regimens as first-line) | NA |

| Developing regions | ||||||||||

| Hungria et al. [19] | Analysis of 2 observational studies datasets | 1998–2007 | Latin America and Asia | NA | MM | 3664 | NA | 26% | NA | Median OS: 56 months in Latin America and 47 months in Asia (HR: 0.83, P < 0.001) |

| Hungria et al. [21, 35] | Retrospective medical chart review | 2008–2015 | Latin America | Median 2.2 years | NDMM | 1518 | Median: 61.0 years | 33.9% | Thalidomide- and bortezomib-based regimens |

Median PFS following first-line treatment SCT: 31.1 months Non-SCT: 15 months Median PFS following second-line treatment: SCT: 9.5 months Non-SCT: 10.9 months PR or above: 91.7% with SCT vs 64.9% without SCT |

| Hungria et al. [28] | Retrospective-prospective study | 2007–2009 | Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru | 62 months | MM | 852 |

Mean (SCT-eligible:): 54.7 years Mean (SCT-ineligible): 67.4 years |

ASCT: 26.9% | Thalidomide-based regimens most common in SCT-ineligible patients |

Median OS: SCT-ineligible: 43 months SCT: 73.6 months |

| Nasr et al. [24] | Retrospective study | 2002–2019 | Lebanon | NA | NDMM | 134 | Mean: 61.9 years | 24.6% | Bortezomib-based regimens were most common induction agents |

Mean PFS similar across different bortezomib-based regimens Mean PFS with SCT vs no SCT (75 vs 52 months, P = 0.016) |

| Qian et al. [15] | Retrospective study | 2007–2015 | China | NA | NDMM | 122 | Median: 70.5 years | NA | Both novel and conventional agents used |

Median OS: 33 months 5-year OS rate: 30.4% OS with and without bortezomib-based regimens: 37 vs 28 months |

| Weil et al. [36] | Retrospective study | 2009–2015 | Israel | 12 months | NDMM | 552 | Mean: 65.6 years | 38.4% | Both novel and conventional agents used |

Median OS: 5.2 months Median OS with bortezomib-based regimens: 6.5 months |

1L first-line, 5L fifth-line, ASCT autologous stem cell transplantation, CR complete remission, HR hazard ratio, MM multiple myeloma, NA not available, NDMM newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, NR not reached, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, PR partial response, RRMM relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, SCT stem cell transplantation, TTNT time to next treatment, US-SEER United States-Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, VGPR very good partial remission, VMP bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone

Adverse events

For a median follow-up duration of 57 months, a total of 1623 AEs were reported in 579 (38.3%) patients with NDMM. Of these, 599 were treatment-related AEs reported in 274 (18.1%) patients, and 478 were serious adverse events reported in 267 (17.7%) patients.

Discussion

INTEGRATE is one of the largest real-world studies to characterize the management of MM in regions outside Europe and North America. It showed that novel agents like proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs in combination with first-line SCT during earlier lines of treatment led to better clinical outcomes across regions like Argentina, East Asia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Türkiye. Considering the limited real-world evidence regarding MM in these regions, the present study contributes relevant real-world data to the literature. Additionally, these findings may help serve as reference for future studies on MM in these regions.

In general, patient characteristics in patients with NDMM were similar to those reported in other real-world studies [5–14, 16–21]. Although consistent with previous real-world reports [8, 17, 19, 22–25], the SCT rates at MM diagnosis in this study was low (31.7%), despite evidence suggesting early SCT following induction therapy in eligible patients with MM is the standard of care to achieve deep response [26]. Most patients who did not receive SCT were ineligible, although the reason for this was not recorded in over half of the ineligible patients. Among the SCT-eligible patients, patient refusal and comorbid conditions were cited as causal factors for not receiving SCT treatment. The logistical challenges associated with low numbers of transplant centers, waiting lists, as well as added costs in resource-limited countries [5, 6, 27], could also have contributed to the lower proportion of SCT observed in these regions.

Patients with NDMM most commonly received bortezomib-based regimens for the first three lines and lenalidomide-based regimens for later lines of treatment across all regions except Argentina. This is consistent with other real-world studies from both developed and developing countries [9–12, 15, 17–20, 24]. In Argentina, thalidomide-based regimens were common in the first two lines of treatment, consistent with previous observations in Latin America [27–29]. The observed use of the same treatments in different lines is in contrast with current treatment patterns [30], where clinicians opt to change drugs for different lines of therapy. Consistent with observations from other real-world studies [9–12, 15, 17–20, 24], choice of chemotherapy regimens varied considerably in clinical practice across the different regions (Fig. 1B and Supplementary material S3). Although triplet regimens were more common than doublet regimens during first-line treatment, their use declined with subsequent lines of treatment. This may be due to poor tolerance, drug resistance, decreased performance status of patients with disease progression, limited accessibility to triplet regimens, or higher costs.

The treatment regimens were generally used for similar durations to those reported in other real-world studies [9, 11, 18, 20, 31, 32]. Completion of planned treatment was a common reason for treatment change, which contrasts with current practices [30], where treatment continues until disease progression. This could be because maintenance treatments were not common at the time of the study, or treatment durations in developing regions were only for a fixed duration due to costs and/or accessibility. The proportion of patients receiving subsequent lines of treatment consistently decreased with each line of treatment, which was consistent with other real-world studies [8, 11, 25]. This may be due to frailty, advanced age, loss to follow-up, and complications or death associated with disease severity. In resource-limited countries, this may also be influenced by increased costs and complexity of treatment regimens and patients’ ability to pay for treatment [5, 6, 33]. The decreasing proportion of patients receiving subsequent lines of treatment suggests the need for upfront use of effective and optimal treatment strategies, rather than reserving them for later lines.

The median TTNT in patients with NDMM, especially for the first three lines of treatment was relatively longer (range 20.9–39.5 months) than found in other real-world studies of MM with novel agents (range 12.6–38.4 months) [10, 12, 20, 34]. The OS and clinical response rates in our study were higher than those reported in other real-world studies [6, 8–11, 19, 20, 28, 32]. A US study by Mohty et al. showed a median TTNT ranging from 19.3 to 38.4 months with lenalidomide- and bortezomib-based regimens [9], and a retrospective study in China showed better median OS with bortezomib-based regimens than with conventional regimens (37 vs 28 months, P = 0.029) [15]. Median OS and clinical response rates were significantly better in patients with first-line SCT than in the non-SCT cohort. This is consistent with other real-world studies that have shown the positive impact of SCT on clinical outcomes in patients with NDMM [8, 20, 28]. In a multicenter registry study in Finland, the median TTNT for first-line treatment (33.9 months) and median OS (not reached) with novel agents combined with SCT were better than without SCT (12.6 and 46.2 months, respectively) [20]. The Latin American HOLA study showed that patients with SCT had longer median OS (79.3 vs 52.8 months, P < 0.0001), longer median PFS following first-line treatment (31.1 vs 15.0 months, P < 0.0001), and higher rates of partial response or above (91.7% vs 64.9%, P < 0.0001) than patients without SCT [35]. A European study and a Latin American study showed that patients with SCT had a higher complete response at first-line (47% vs 25% of patients; P < 0.001) [11] and better OS (73.6 vs 43.0 months) [28] than patients without SCT, respectively. Further, any documented relapse or disease progression after first-line treatment for both patients undergoing SCT and those without SCT were less than 50%, implying that some patients may have altered their treatment regimens even without clinically evident progression meeting International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria, as observed by the TTNT of 39.5 months within the first-line population. Together, these findings may suggest that the clinical outcomes may be better with the use of novel agents and SCT during the earlier lines of treatment in patients with NDMM.

This study has several limitations due to its retrospective nature. The patients were predominantly from specialized treatment centers, thus may not represent the entire patient population. Treatment pathways and clinical outcomes were based on investigators’ assessments, and not on any conventionally defined criteria. The results may have been influenced by selection bias stemming from the retention of patients with minimal data, the inclusion of only patients with prior treatment, and the potential exclusion of older patients, potentially due to systematic bias in referrals to participating centers or case inclusions. The generalization of these data should be made with caution, due to the unknown impact of country- and institution-specific differences in availability, access, and choice of different lines of treatments, patient selection bias, and relatively younger and healthier patients than other real-world studies. Low patient numbers in later treatment lines due to deficiencies in the follow-up data limit the generalizability of the findings. However, this can be mitigated through careful interpretation, particularly when considering the sample sizes in each treatment line, such as focusing on the first three lines of therapy. The treatment choices presented here do not consider the physician’s intention underlying that treatment choice. The TTNT may not accurately reflect treatment effectiveness since the reasons for starting a new therapy are not always related to disease progression and may vary between different centers. Additionally, some patients who may have progressed to relapse or refractory MM during the study period may have influenced the overall results. The AE data presented here may only include those recorded in the medical records, and may not include AEs not formally recorded. Other limitations include not assessing progression-free survival and not assessing TTNT by SCT status. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the study findings are from 2010 to 2011, which may not be applicable today due to the changed diagnostic and treatment landscape in MM. However, these findings contribute important real-world data in MM from regions under-represented in literature.

In conclusion, our study provides a wealth of information to better understand the management of NDMM in regions outside Europe and North America. These retrospective real-world data highlight the diversity of treatments used to manage MM in clinical practice. Clinical outcomes were better in patients who underwent SCT than those without SCT, emphasizing a positive impact of SCT on long-term clinical outcomes. The variety of treatment regimens used in this study highlights that the treatment choices for different lines of therapy in MM should be individualized and strategically sequenced based on patient and tolerability profiles. The treatment strategy should consider the most effective and novel treatments at initiation of therapy for longer durations and using SCT earlier in treatment to achieve better outcomes. The findings of our study provide a rich source of real-world evidence for future research in MM, which can inform how best to meet the future needs of patients with MM, especially in regions outside Europe and North America.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients, participating principal and co-investigators, and study site staff for their contributions to the INTEGRATE study. Data analysis was provided by IQVIA, and medical writing assistance was provided by Sandra Kurian (MPharm) of Synergy Vision Ltd (London, UK), with funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International AG – Singapore Branch.

Author contributions

All authors had access to and verified all the data reported in this manuscript and accept responsibility for this publication. All authors were involved in study design and methodology. All authors except ZH were involved in data collection. ZH was involved in the statistical analysis of this study. All authors contributed equally toward analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript development. All authors have reviewed and approved this manuscript for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals International AG—Singapore Branch. The funding source was involved in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of this manuscript, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability

The datasets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participants’ data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available within 3 months from initial request to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection, and requirements for consent and anonymization.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Kihyun Kim has received research funding from Janssen, BMS, and Amgen, and served as a consultant for Janssen, BMS, Amgen, Takeda, and LG Chem. Estelle Verburgh has received research funding from MSD and Takeda, received honoraria and speaker’s bureau from Takeda, served in an advisory role for MSD, NovoNordisk, and Takeda, and has unpaid roles in the executive committees of South African Clinical Hematology Society and South African Stem Cell Transplantation Society. Tatiana Mitina has received honoraria and serves as a member on the Board of Directors or advisory committee for Takeda. Wenming Chen has received honoraria from Takeda, Johnson & Johnson, Beigene, Amgen, Sanofi, Antengene, and Novartis. Su-Peng Yeh has received honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, Janssen, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Takeda, and has served in an advisory role for Abbvie, Amgen, Janssen, Astellas, Astex, Novartis, Sanofi, and Takeda. Natalia Schutz has received honoraria, research funding, and serves on the advisory board for Takeda, Amgen, Johnson & Johnson, and Sanofi. Fahad Alsharif has no conflicts of interest. Wee Joo Chng has received honoraria from Takeda, Johnson & Johnson, BMS/Celgene, Amgen, Abbvie, Sanofi, Pfizer, Antengene, and Novartis, and research funding from Johnson & Johnson, BMS/Celgene, Novartis, and Aslan. Zhongwen Huang is an employee and shareholder of Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Meral Beksac has served on the advisory board and speakers bureau for Amgen, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda, and on the advisory board for Oncopeptides.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised for retrospective open access.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/22/2025

The original online version of this article was revised for retrospective open access.

Change history

5/20/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12185-025-04012-1

References

- 1.Naymagon L, Abdul-Hay M. Novel agents in the treatment of multiple myeloma: a review about the future. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9(1):52. 10.1186/s13045-016-0282-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szalat R, Munshi NC. Novel agents in multiple myeloma. Cancer J. 2019;25(1):45–53. 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dima D, Jiang D, Singh DJ, Hasipek M, Shah HS, Ullah F, et al. Multiple myeloma therapy: emerging trends and challenges. Cancers. 2022;14(17):4082. 10.3390/cancers14174082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffer CA, Zonder JA. Transplantation for myeloma—now or later? N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1378–9. 10.1056/NEJMe1700453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasola FA, Eteng KII, Akinyemi JO. Multiple myeloma: challenges of management in a developing country. J Med Med Sci. 2012;3(6):397–403. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogbonn Collins N. Management of multiple myeloma in developing countries. In: Khalid Ahmed A-A, editor. Update on multiple myeloma. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2018. p. Ch. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chari A, Parikh K, Ni Q, Abouzaid S. Treatment patterns and clinical and economic outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide- and/or bortezomib-containing regimens without stem cell transplant in a real-world setting. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(10):645–55. 10.1016/j.clml.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coriu D, Dytfeld D, Niepel D, Spicka I, Markuljak I, Mihaylov G, et al. Real-world multiple myeloma management practice patterns and outcomes in selected Central and Eastern European countries. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2018;128(9):500–11. 10.20452/pamw.4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohty M, Knauf W, Romanus D, Corman S, Verleger K, Kwon Y, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in non-transplant newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Eur J Haematol. 2020;105(3):308–25. 10.1111/ejh.13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohty M, Terpos E, Mateos M-V, Cavo M, Lejniece S, Beksac M, et al. Multiple myeloma treatment in real-world clinical practice: results of a prospective, multinational, noninterventional study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(10):e401–19. 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yong K, Delforge M, Driessen C, Fink L, Flinois A, Gonzalez-McQuire S, et al. Multiple myeloma: patient outcomes in real-world practice. Br J Hematol. 2016;175(2):252–64. 10.1111/bjh.14213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He J, Schmerold L, Van Rampelbergh R, Qiu L, Potluri R, Dasgupta A, et al. Treatment pattern and outcomes in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients who did not receive autologous stem cell transplantation: a real-world observational study : treatment pattern and outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma. Adv Ther. 2021;38(1):640–59. 10.1007/s12325-020-01546-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu WN, Chang CF, Chung CH, Chien WC, Huang TC, Wu YY, et al. Clinical outcomes of bortezomib-based therapy in Taiwanese patients with multiple myeloma: a nationwide population-based study and a single-institute analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9): e0222522. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J, Lu J, Chen W, Huo Y, Huang X, Hou J. Clinical features and treatment outcome in newly diagnosed Chinese patients with multiple myeloma: results of a multicenter analysis. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4(8): e239. 10.1038/bcj.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian X, Chen H, Xia J, Wang J, Zhou X, Guo H. Real-world clinical outcomes in elderly Chinese patients with multiple myeloma: a single-center experience. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5887–93. 10.12659/msm.907588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schütz NP, Ochoa P, Duarte P, Remaggi G, Yantorno S, Corzo A, et al. Real world outcomes with bortezomib thalidomide dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide bortezomib dexamethasone induction treatment for transplant eligible multiple myeloma patients in a Latin American country. A retrospective cohort study from Grupo Argentino de Mieloma Múltiple. Hematol Oncol. 2020;38(3):363–71. 10.1002/hon.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akizuki K, Matsuoka H, Toyama T, Kamiunten A, Sekine M, Shide K, et al. Real-world data on clinical features, outcomes, and prognostic factors in multiple myeloma from Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. J Clin Med. 2020;10(1):105. 10.3390/jcm10010105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cejalvo MJ, Bustamante G, González E, Vázquez-Álvarez J, García R, Ramírez-Payer Á, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in real-world transplant-ineligible patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2021;100(7):1769–78. 10.1007/s00277-021-04529-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hungria VTM, Lee JH, Maiolino A, de Queiroz CE, Martinez G, Bittencourt R, et al. Survival differences in multiple myeloma in Latin America and Asia: a comparison involving 3664 patients from regional registries. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(4):941–9. 10.1007/s00277-019-03602-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remes K, Anttila P, Silvennoinen R, Putkonen M, Ollikainen H, Terävä V, et al. Real-world treatment outcomes in multiple myeloma: Multicenter registry results from Finland 2009–2013. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12): e0208507. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Moraes Hungria VT, Chiattone C, Pavlovsky M, Abenoza LM, Agreda GP, Armenta J, et al. Epidemiology of hematologic malignancies in real-world settings: findings from the Hemato-Oncology Latin America Observational Registry Study. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–19. 10.1200/jgo.19.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fonseca R, Usmani SZ, Mehra M, Slavcev M, He J, Cote S, et al. Frontline treatment patterns and attrition rates by subsequent lines of therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1087. 10.1186/s12885-020-07503-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar SK, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Terpos E, Nahi H, Goldschmidt H, et al. Natural history of relapsed myeloma, refractory to immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors: a multicenter IMWG study. Leukemia. 2017;31(11):2443–8. 10.1038/leu.2017.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasr F, Ghoche AA, Diab S, Nasr L, Ammanouil E, Riachy C, et al. Lebanese real-world experience in treating multiple myeloma: a multicenter retrospective study. Leuk Res Rep. 2021;15: 100252. 10.1016/j.lrr.2021.100252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raab MS, Cavo M, Delforge M, Driessen C, Fink L, Flinois A, et al. Multiple myeloma: practice patterns across Europe. Br J Haematol. 2016;175(1):66–76. 10.1111/bjh.14193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, Mateos MV, Zweegman S, Cook G, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up(†). Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):309–22. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Magalhães Filho RJP, Crusoe E, Riva E, Bujan W, Conte G, Navarro Cabrera JR, et al. Analysis of availability and access of anti-myeloma drugs and impact on the management of multiple myeloma in Latin American countries. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(1):e43–50. 10.1016/j.clml.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hungria VT, Maiolino A, Martinez G, Duarte GO, Bittencourt R, Peters L, et al. Observational study of multiple myeloma in Latin America. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(1):65–72. 10.1007/s00277-016-2866-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vargas-Serafin C, Acosta-Medina AA, Ordonez-Gonzalez I, Martínez-Baños D, Bourlon C. Impact of socioeconomic characteristics and comorbidities on therapy initiation and outcomes of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: real-world data from a resource-constrained setting. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(3):182–7. 10.1016/j.clml.2020.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goel U, Usmani S, Kumar S. Current approaches to management of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(S1):S3–25. 10.1002/ajh.26512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez-McQuire S, Yong K, Leleu H, Mennini FS, Flinois A, Gazzola C, et al. Healthcare resource utilization among patients with relapsed multiple myeloma in the UK, France, and Italy. J Med Econ. 2018;21(5):450–67. 10.1080/13696998.2017.1421546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hájek R, Jarkovsky J, Maisnar V, Pour L, Špička I, Minařík J, et al. Real-world outcomes of multiple myeloma: retrospective analysis of the Czech registry of monoclonal gammopathies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(6):e219–40. 10.1016/j.clml.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarín-Arzaga L, Arredondo-Campos D, Martínez-Pacheco V, Martínez-González O, Ramírez-López A, Gómez-De León A, et al. Impact of the affordability of novel agents in patients with multiple myeloma: real-world data of current clinical practice in Mexico. Cancer. 2018;124(9):1946–53. 10.1002/cncr.31305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibayama H, Itagaki M, Handa H, Yokoyama A, Saito A, Kosugi S, et al. Primary analysis of a prospective cohort study of Japanese patients with plasma cell neoplasms in the novel drug era (2016–2021). Int J Hematol. 2024;119(6):707–21. 10.1007/s12185-024-03754-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Moraes Hungria VT, Martínez-Baños DM, Peñafiel CR, Miguel CE, Vela-Ojeda J, Remaggi G, et al. Multiple myeloma treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in the Latin America Haemato-Oncology (HOLA) Observational Study, 2008–2016. Br J Hematol. 2020;188(3):383–93. 10.1111/bjh.16124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weil C, Gelerstein S, Sharman Moser S, Chodick G, Barit Ben-David N, Shalev V, et al. Real-world epidemiology, treatment patterns and survival of multiple myeloma patients in a large nationwide health plan. Leuk Res. 2019;85: 106219. 10.1016/j.leukres.2019.106219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participants’ data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available within 3 months from initial request to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection, and requirements for consent and anonymization.