ABSTRACT

Objective

This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of short‐term flupentixol‐melitracen in adult patients with aerophagia through a single‐center parallel randomized controlled trial.

Methods

Eligible patients were randomly divided into three groups based on the order of subjects. Each group consisted of 30 patients (15F/15M) who received 2 weeks of treatment. Groups 1, 2, and 3 were treated with itopride hydrochloride, flupentixol‐melitracen, and the combination of two medicines, respectively. The mean scores of aerophagia symptom relief measured by the visual analogue scale (VAS) after treatment were used as the endpoints.

Results

A total of 90 patients were eligible for the study, of which 76 completed the 2‐week treatment period. The scores indicating improvement of aerophagia by VAS showed significant improvement in Group 2 compared with Group 1 (6.92 ± 2.96 vs. 4.58 ± 4.08, p = 0.016) and Group 3 compared with Group 1 (7.34 ± 3.12 vs. 4.58 ± 4.08, p = 0.006). There was no significant difference between Group 2 and Group 3 (6.92 ± 2.96 vs. 7.34 ± 3.12, p = 0.618). The percentage of patients exhibiting scores indicating improvement of aerophagia by VAS ≥ 5 in Group 2 and Group 3 was significantly higher than Group 1 (p = 0.020, p = 0.007). The three groups had similar baseline characteristics and experienced similar non‐serious adverse effects during the treatment period.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that short‐term treatment with flupentixol‐melitracen, with or without a prokinetic benzamide derivative, is likely to improve symptoms of aerophagia in adults without significant adverse effects.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: ChiCTR‐IPR‐15006869

Keywords: aerophagy, antidepressant drugs, anxiety, anxiolytic drugs, depression

1. Introduction

Air swallowing is a physiological behavior that occurs in every individual. During this process, a variable volume of air (8–32 mL) is ingested into the gastrointestinal tract [1]. With the shift in the medical model from a biological to a bio‐psycho‐social approach, attention has been given to the association between emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety, and functional gastrointestinal disorders [2, 3]. Misdiagnosis, clinical neglect, and non‐targeted approaches have led to an increase in the frequency of consultations, cross‐consultations, and repeated diagnostic testing, potentially causing a significant psychological burden [4].

According to the Rome III criteria, excessive air swallowing accompanied by excessive belching has been classified as aerophagia [5]. There is a scarcity of literature on the prevalence or incidence of aerophagia in the general population. In the studied pediatric population, the prevalence of aerophagia was 7.5% [6]. A study reported that aerophagia affected 6.3% of adolescents, ranking it lower than functional constipation and abdominal migraines but higher than irritable bowel syndrome [7]. Additionally, aerophagia can be easily misdiagnosed as other illnesses like gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional dyspepsia, resulting in limited available studies on aerophagia [8, 9].

There were only a few published studies on treatments for belching in patients with aerophagia, which included speech therapy combined with cognitive behavioral therapy, as well as drug efficacy. The former mainly focused on increasing awareness of esophageal air influx and carrying out exercises to discontinue the belching mechanism [10]. The effective exercise of diaphragm contractions was usually achieved through controlling diaphragmatic breathing [11]. In terms of drug efficacy, baclofen, an agonist of the gamma‐aminobutyric acid B receptor, has been shown to increase lower esophageal sphincter pressure and decrease swallowing rate [12]. Prokinetic agents, simethicone, and activated charcoal can also be used to eliminate gastrointestinal gas [13].

Flupentixol exhibits anxiolytic and antidepressant properties at low doses. Melitracen acts as a tricyclic biphasic antidepressant when administered in low doses. Flupentixol‐melitracen is a combination medication utilized for the treatment of various mental disorders, including boredom, anxiety, and depression [14]. It is characterized by a quick onset of action and minimal side effects [14]. The relationship between emotional disorders and aerophagia is yet to be fully understood and requires further study. However, due to the clinical association between aerophagia and mood disorders, certain antidepressant and antipsychotic medications have been employed as empirical treatment options [15, 16, 17]. Flupentixol‐melitracen may be helpful for individuals suffering from aerophagia. This study was designed to demonstrate the clinical efficacy and safety of short‐term flupentixol‐melitracen in treating aerophagia among adult individuals through a single‐center parallel randomized controlled trial.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria

A total of 90 eligible subjects were enrolled in the outpatient department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University between November 2012 and November 2020. The diagnosis of aerophagia was primarily based on the Rome III diagnostic criteria [18], as this study began in 2012.

To ensure consistent patient selection for the trial, inclusion criteria were established. These criteria included adult patients who exhibited clinical symptoms in accordance with the Rome III diagnostic criteria. These symptoms included recurrent and troublesome belching occurring at least several times a week, as well as observable or objectively detectable air swallowing. In addition, patients were required to have experienced both recurrent belching and air swallowing for a minimum of 6 months prior to diagnosis, and for almost 3 months after diagnosis.

Exclusion criteria were also defined for the study. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) Obvious organic lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract, including cancer, peptic ulcer disease, or erosive reflux esophagitis; (2) Non‐erosive reflux disease, patients exhibiting symptoms of GERD, such as heartburn and acid regurgitation, and those who had successful empirical acid‐suppressive therapy were excluded; (3) Severe cognitive impairment and psychiatric disorders requiring immediate intervention, or hindering their ability to participate; (4) Critical organic lesions in the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, heart, kidney, thyroid, or any other vital organ. (5) Long term use of the drugs involved in this study, as well as a history of any use of these drugs involved in this study within the past 2 weeks; (6) A history of allergy to the drugs used in the study; (7) Highly excitable, acutely intoxicated with alcohol, barbiturates or opium; (8) Pregnant or breastfeeding patients.

2.2. Study Drugs

Itopride hydrochloride 50 mg (Elthon; Abbott Japan Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was administered orally three times daily. Flupentixol‐melitracen (Deanxit; H. Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark), containing 0.5 mg flupentixol and 10 mg melitracen, was administered twice daily (Bid_8‐12).

2.3. Study Design and Ethical Approval

This study was registered as a randomized parallel controlled trial (identifier: ChiCTR‐IPR‐15006869) at ClinicalTrials.gov. Its objective was to determine the clinical efficacy and safety of short‐term flupentixol‐melitracen in treating aerophagia among adult individuals. Approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University (approval number: No. 181, 2013).

A stratified sampling strategy was employed, with patients' sex as the basis for stratification. A basic random sampling approach using lots was then utilized. Consequently, 90 eligible outpatients were randomly allocated into three equal groups based on the sequence of their appointments. The grouping was as follows: Group 1 included 30 patients (15F/15M) treated with itopride hydrochloride; Group 2 contained 30 patients (15F/15M) treated with flupentixol‐melitracen; and Group 3 comprised 30 patients (15F/15M) treated with both itopride hydrochloride and flupentixol‐melitracen. Both of the two study drugs were given for 14 consecutive days. Figure 1 presents the study design and enrolment process.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram for the process of patient selection.

Baseline information, such as age, duration of aerophagia, and accompanying symptoms (insomnia, bloating, constipation, and diarrhea), was collected at the time of diagnosis.

2.4. Clinical Efficacy

The trial lasted for a duration of 2 weeks. After its completion, the treatment efficacies were evaluated by comparing the changes in clinical symptoms before and after the treatments. The efficacy of treatments was assessed by evaluating the overall improvement of belching using the belching visual analogue scale (VAS) [19], which is a 10‐point numeric rating scale. The percentage of patients exhibiting scores indicating improvement of aerophagia by VAS ≥ 5 in each group was also considered. The initial symptom of each patient was considered as 10 points, and each point of symptom reduction on the scale represents an improvement of the symptom by one point (recording as score of one), and so on.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The estimation of the sample size was based on pre‐experimental data, which indicated mean scores indicating improvement of aerophagia by VAS of 4.5 for Group 1, 7 for Group 2, and 7.5 for Group 3. The bilateral Type I error probability was set at α = 0.05, accompanied by a certainty level of β = 0.2. Sample size estimation was performed utilizing one‐way analysis of variance F‐tests of the software PASS version 15.0.5. The calculations indicated that 24 cases were necessary in each group. The Chi‐squared tests were employed to assess categorical variables. To compare continuous variables between groups, either the Student's t‐test or one‐way analysis of variance test was utilized. In cases where the data did not meet the homoscedasticity requirement or had a non‐normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U non‐parametric test was employed. Generalized estimating equations were used to analyze the mean scores of aerophagia symptom relief measured by VAS. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, Version 26.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 90 patients (ranging from 18 to 76 years of age) were included in this trial, diagnosed with aerophagia based on the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Among these patients, three did not adhere to their medication regimen, and nine were lost to follow‐up. One patient reported experiencing mild insomnia after taking itopride hydrochloride and flupentixol‐melitracen, and another patient developed hypotension after taking itopride hydrochloride. Consequently, 76 patients successfully completed the 2‐week treatment courses as outlined in the protocol (Figure 1). The demographics and clinical characteristics of these 76 patients are summarized in Table 1, and no significant statistical differences were observed among the three groups.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | p a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 26 | 25 | 25 | |

| Age (years) | 39.54 ± 14.98 | 47.28 ± 11.54 | 40.84 ± 12.23 | 0.085 |

| Sex, n | 0.520 | |||

| Male | 13 | 15 | 11 | |

| Female | 13 | 10 | 14 | |

| Duration of aerophagia (months) | 20.85 ± 14.56 | 22.96 ± 16.13 | 23.45 ± 19.87 | 0.844 |

| Accompanying symptoms (%) | ||||

| Insomnia | 17 | 15 | 14 | 0.789 |

| Bloating | 26 | 20 | 23 | 0.046 |

| Constipation | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0.081 |

| Diarrhea | 3 | 6 | 6 | 0.432 |

Significance level of mean difference: p < 0.05.

3.2. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Study Drugs

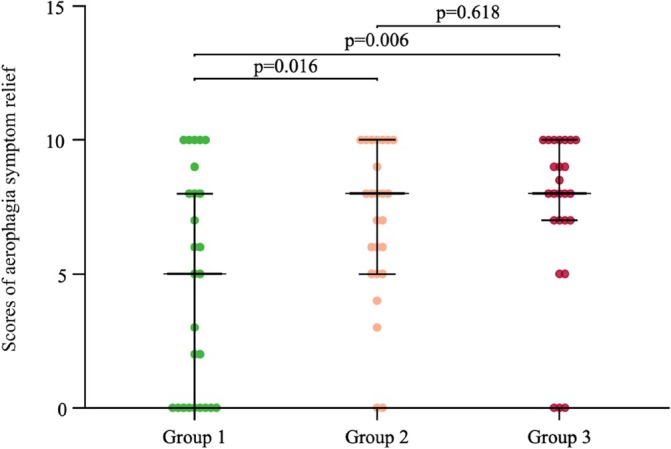

A total of 76 out of 90 eligible patients successfully completed the 2‐week study. The scores indicating improvement of aerophagia by VAS were 4.58 ± 4.08, 6.92 ± 2.96, and 7.34 ± 3.12 in Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, aerophagia symptoms displayed a significant improvement in Group 2 compared with Group 1 (p = 0.016), as well as in Group 3 compared with Group 1 (p = 0.006). However, no significant difference was observed between Group 2 and Group 3 (p = 0.618).

FIGURE 2.

The scores indicating improvement of aerophagia in each group, as measured by the visual analogue scale (VAS), 2 weeks after treatment.

The percentage of patients exhibiting scores indicating improvement of aerophagia by VAS ≥ 5 was found in 53.8% (14/26), 84.0% (21/25), and 88.0% (22/25) in Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3, respectively. In comparison, the percentage of patients exhibiting scores indicating improvement of aerophagia by VAS ≥ 5 in Group 2 and Group 3 was significantly higher than Group 1 (p = 0.020, p = 0.007; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The percentage of patients exhibiting scores indicating improvement of aerophagia ≥ 5 in each group, as measured by the visual analogue scale (VAS), 2 weeks after treatment.

One patient in Group 1 encountered a hypotensive episode, while another patient in Group 3 manifested symptoms of insomnia and trembling disorder subsequent to the treatment. However, both patients achieved a complete recovery from side effects upon discontinuation of the medications.

4. Discussion

The pathophysiology of aerophagia is not completely understood. Most studies utilize high‐resolution manometry and impedance [20, 21, 22]. The studies propose that aerophagia is caused by an expansion of stomach capacity due to the retention of air, along with a vagally driven reaction that triggers relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing the release of gastric air. While the symptom of recurrent excessive belching may initially be tolerable for many patients, it progressively becomes intolerable, primarily due to frequent medical visits, misdiagnosis, and its adverse impact on quality of life and daily activities [6, 23].

There appears to be a reciprocal relationship between psychological disorders and aerophagia, where they influence each other causally and symptomatically. Previous studies demonstrated the act of air swallowing significantly increased when patients experienced feelings of nervousness, anxiety, or depression [15]. It is worth mentioning that numerous studies have found a significant association between belching disorder and anxiety disorder [17, 21]. Furthermore, pneumatosis of the stomach and intestine can potentially alter the microbiota of the digestive tract, consequently influencing the mental well‐being of the host through the gut–brain axis [24]. These changes potentially lead to the development and worsening of anxiety and depression.

Like many common functional gastrointestinal disorders, aerophagia has been hypothesized to have a predisposition toward psychological factors; however, limited research has been conducted to investigate this hypothesis [4]. A study involving 3335 subjects demonstrated that stress independently contributes to belching disorders [17]. Previous studies presented as adult case reports or conducted on children have suggested that the pathogenesis of aerophagia may be associated with psychological factors [25, 26].

Previously, treatments for belching have primarily encompassed speech therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy [10], diaphragmatic breathing [11], baclofen [12], acid‐suppressing drugs [20], surgical intervention [27], and prokinetic agents [27]. The primary focus of treatment is on cognitive‐behavioral therapy, speech therapy, and baclofen [16, 22, 28]. However, cognitive behavioral therapy and speech therapy, despite their potential efficacy to some extent, proved to be time‐consuming and burdensome [10]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of baclofen as a therapeutic treatment was unsatisfactory. The previous studies have shown that baclofen can induce secondary effects [29, 30].

Flupentixol‐melitracen exhibits anxiolytic and antidepressant properties, promoting enhanced autonomic and central nervous system functioning while modulating the levels of various neurotransmitters within the synaptic gaps [14]. Additionally, it reduces mental perception anomalies and diminishes visceral hypersensitivity, potentially through increased vagus nerve activity in individuals with this condition [14]. In the present single‐center parallel randomized controlled trial, we presented evidence that treatment with flupentixol‐melitracen significantly reduced belching severity, indicating its clinical effectiveness and supporting its promotion for short‐term use in patients with aerophagia. Moreover, patients demonstrated a superior response to flupentixol‐melitracen in comparison to those who solely received prokinetic agents. Furthermore, no side effects were reported in patients who solely received flupentixol‐melitracen. Additionally, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were implemented, excluding individuals with comorbid gastroesophageal reflux disease and those using proton pump inhibitors. This study could offer a new and innovative therapeutic approach as an alternative treatment option for aerophagia in the future.

The limitations of this study stem from its short duration of therapy and its single‐center nature. These tests were not conducted on our patients due to their time‐consuming nature, high cost, limited medical compensation, and the discomfort associated with the tests, often resulting in poor adherence. Additionally, the relatively high rate of loss to follow‐up (10%) in this study somewhat reduced the impact of the achieved results. Furthermore, in order to exclude patients with GERD or peptic ulcer, or other symptoms of upper GI tract disease, entry criteria for this clinical trial are generally rigorous, and most patients might not be suitable for the studies. Only patients with isolated aerophagia were included. However, the sample size of the study might be too small to draw firm conclusions. To enhance the credibility of the study's findings, the usage of high‐resolution manometry and 24‐h pH‐impedance, in accordance with the Rome IV diagnostic criteria for belching disorders, would provide objective data [31].

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study is the very first one to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of anti‐depressant in controlling the symptom of aerophagia. Our results suggest that the use of flupentixol‐melitracen with or without a prokinetic benzamide derivative is likely to improve symptoms without significant adverse effects. Our findings might provide a treatment option for patients whose aerophagia arises and attract the attention of mental health issues in patients with aerophagia.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University (approval number: No. 181, 2013).

Consent

For the test to be conducted and the results to be published, informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Zhu S.‐l., Li P., Xu H.‐w., Yao S., and Huang L.‐l., “Therapeutic Efficacy of Flupentixol‐Melitracen for Treatment of Aerophagia in Adults: A Single‐Center Parallel Randomized Controlled Trial,” JGH Open 9, no. 8 (2025): e70199, 10.1002/jgh3.70199.

Funding: This work was supported by Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou City (Grant 201803010103).

The first three authors contributed equally to this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Pouderoux P., Ergun G. A., Lin S., and Kahrilas P. J., “Esophageal Bolus Transit Imaged by Ultrafast Computerized Tomography,” Gastroenterology 110 (1996): 1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee S. H., Yoon S. H., Jung Y., et al., “Emotional Well‐Being and Gut Microbiome Profiles by Enterotype,” Scientific Reports 10 (2020): 20736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai W., Zhou Y., Wan L., et al., “Transcriptomic Signatures Associated With Gray Matter Volume Changes in Patients With Functional Constipation,” Frontiers in Neuroscience 15 (2021): 791831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Appleby B. S. and Rosenberg P. B., “Aerophagia as the Initial Presenting Symptom of a Depressed Patient,” Primary Care Companion To The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 8 (2006): 245–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chitkara D. K., Bredenoord A. J., Rucker M. J., et al., “Aerophagia in Adults: A Comparison With Functional Dyspepsia,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 22 (2005): 855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Devanarayana N. M. and Rajindrajith S., “Aerophagia Among Sri Lankan Schoolchildren: Epidemiological Patterns and Symptom Characteristics,” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 54 (2012): 516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scarpato E., Kolacek S., Jojkic‐Pavkov D., et al., “Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents in the Mediterranean Region of Europe,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16 (2018): 870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Masui D., Nikaki K., Sawada A., Sonmez S., Yazaki E., and Sifrim D., “Belching in Children: Prevalence and Association With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease,” Neurogastroenterology and Motility 34 (2022): e14194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plaidum S., Patcharatrakul T., Promjampa W., and Gonlachanvit S., “The Effect of Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAP) Meals on Transient Lower Esophageal Relaxations (TLESR) in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Patients With Overlapping Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS),” Nutrients 14 (2022): 1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glasinovic E., Wynter E., Arguero J., et al., “Treatment of Supragastric Belching With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Improves Quality of Life and Reduces Acid Gastroesophageal Reflux,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 113 (2018): 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ong A. M., Chua L. T., Khor C. J., et al., “Diaphragmatic Breathing Reduces Belching and Proton Pump Inhibitor Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16 (2018): 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenhill C., “Motility: Baclofen Effective for Rumination and Supragastric Belching in a Pilot Study,” Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 9, no. 3 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fardy J. and Sullivan S., “Gastrointestinal Gas,” CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal 139 (1988): 1137–1142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hashash J. G., Abdul‐Baki H., Azar C., et al., “Clinical Trial: A Randomized Controlled Cross‐Over Study of Flupenthixol + Melitracen in Functional Dyspepsia,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 27 (2008): 1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bredenoord A. J., Weusten B. L., Timmer R., and Smout A. J., “Psychological Factors Affect the Frequency of Belching in Patients With Aerophagia,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 101 (2006): 2777–2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Popa S. L., Surdea‐Blaga T., David L., et al., “Supragastric Belching: Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Issues and Treatment,” Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology 28 (2022): 168–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shang H. T., Ouyang Z., Chen C., Duan C. F., Bai T., and Hou X. H., “Prevalence and Risk Factors of Belching Disorders: A Cross‐Sectional Study Among Freshman College Students,” Journal of Digestive Diseases 23 (2022): 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tack J., Talley N. J., Camilleri M., et al., “Functional Gastroduodenal Disorders,” Gastroenterology 130 (2006): 1466–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sawada A., Anastasi N., Green A., et al., “Management of Supragastric Belching With Cognitive Behavioural Therapy: Factors Determining Success and Follow‐Up Outcomes at 6–12 Months Post‐Therapy,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 50 (2019): 530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kessing B. F., Bredenoord A. J., and Smout A. J., “The Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Excessive Belching Symptoms,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 109 (2014): 1196–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun X., Ke M., and Wang Z., “Clinical Features and Pathophysiology of Belching Disorders,” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 8 (2015): 21906–21914. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rangan V., Sheth T., Iturrino J., Ballou S., Nee J., and Lembo A., “Belching: Pathogenesis, Clinical Characteristics, and Treatment Strategies,” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 56 (2022): 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rajindrajith S., Hettige S., Gulegoda I., et al., “Aerophagia in Adolescents Is Associated With Exposure to Adverse Life Events and Psychological Maladjustment,” Neurogastroenterology and Motility 30 (2018), 10.1111/nmo.13224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim C. S., Shin G. E., Cheong Y., Shin J.‑. H., Shin D. M., and Chun W. Y., “Experiencing Social Exclusion Changes Gut Microbiota Composition,” Translational Psychiatry 12 (2022): 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hu M. T. and Chaudhuri K. R., “Repetitive Belching, Aerophagia, and Torticollis in Huntington's Disease: A Case Report,” Movement Disorders 13 (1998): 363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oswari H., Alatas F. S., Hegar B., et al., “Aerophagia Study in Indonesia: Prevalence and Association With Family‐Related Stress,” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 55 (2021): 772–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hinder R. A. and Fakhre G. P., “A Question of Gas,” Digestive and Liver Disease 39 (2007): 319–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Punkkinen J., Nyyssönen M., Walamies M., et al., “Behavioral Therapy is Superior to Follow‐Up Without Intervention in Patients With Supragastric Belching—A Randomized Study,” Neurogastroenterology and Motility 34 (2022): e14171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blondeau K., Boecxstaens V., Rommel N., et al., “Baclofen Improves Symptoms and Reduces Postprandial Flow Events in Patients With Rumination and Supragastric Belching,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 10 (2012): 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pauwels A., Broers C., Van Houtte B., et al., “A Randomized Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled, Cross‐Over Study Using Baclofen in the Treatment of Rumination Syndrome,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 113 (2018): 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li J., Xiao Y., Peng S., Lin J., and Chen M., “Characteristics of Belching, Swallowing, and Gastroesophageal Reflux in Belching Patients Based on Rome III Criteria,” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 28 (2013): 1282–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.