Abstract

PURPOSE:

KRAS variants are associated with poor outcomes in biliary tract cancers (BTC). This study assesses the prevalence of KRAS variants and their association with survival and recurrence in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHC), extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHC), and gallbladder adenocarcinoma (GB).

METHODS:

In this cross-sectional, single institution study at Memorial Sloan Kettering, tumors from 985 patients treated between 2004-2022 with IHC, EHC, and GB who underwent either curative intent resection or were treated with chemotherapy for unresectable disease were used for targeted sequencing.

Results:

Of 985 patients sequenced, 15% had a KRAS mutation. 572 had unresectable disease (n=395 IHC, n=71 EHC, n=106 GB) and 413 were treated with curative intent resection (n=175 IHC, n=119 EHC, and n=119 GB). Median follow-up time was 18 months (IQR 11, 31). KRAS G12D mutations were most common in IHC (38%) and EHC (37%) tumors. Mutations in SF3B1 co-occurred with mutant KRAS in IHC and EHC, with co-mutant resectable patients having worse survival after adjusting for tumor type (HR 4.04, 95% CI 1.45-11.2, p=0.007). KRAS G12 mutations were associated with worse survival in IHC patients as compared to WT or other KRAS mutations, regardless of resection status (unresectable p<0.001, resectable p=0.011). After adjusting for clinical covariates, KRAS G12 mutations remained a prognostic indicator for IHC patients compared to WT (HR=1.99, 95% CI=1.41-2.80; p<0.001).

Conclusions:

The adverse impact of KRAS mutations in BTC is driven by G12 alterations in IHC patients regardless of resection status, which was not observed in GB or EHC. There are unique co-mutational partners in distinct BTC subsets. These differences have important clinical implications in the era of KRAS-targeted therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Biliary tract cancer (BTC) is a group of related but distinct malignancies defined by their anatomic location: extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHC), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHC), and gallbladder adenocarcinoma (GB). Resection and adjuvant chemotherapy is the most effective treatment in patients with localized disease1, while systemic therapy remains standard in patients with advanced disease. Despite advances in clinical management, particularly in targeted therapy for the minority of patients with tumors harboring specific genomic alterations2,3, 5-year survival remains poor at 7-20%4. Clinicopathological features were previously used to predict survival, but there is increasing interest in using molecular markers for prognostic assessment.

Large scale cohort analyses revealed the KRAS protooncogene, GTPase (KRAS; OMIM 190070) is a commonly mutated gene in 10% of IHC, up to 47% of EHC, and up to 20% of GB5,6. Disruptions in KRAS signaling leads to oncogenic transformation. KRAS mutations are dominated by single base missense mutations whose frequency varies widely among different cancer types. The majority of these mutations occur at codon 12 (G12), codon 13 (G13), or codon 61 (Q61) and impair GTP hydrolysis, causing constitutive KRAS activation and hyperactive downstream signaling 7.

KRAS variants differentially affect survival in colorectal and lung cancer8-10. In BTCs, limited analyses have been performed to interrogate the clinical consequences of mutant KRAS variants. One study found that in patients with resectable IHC, KRAS G12 variants predicted worse overall survival11. However, the distribution of KRAS variants among BTC subtypes and stages, their effect on survival, and their distinct co-mutational patterns have not been characterized. To address this gap, we interrogated the genomic landscape and prognostic significance of KRAS variants in a large cohort of BTC patients who underwent potentially curative resection or had unresectable disease.

METHODS

Patients:

This was a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of patients with BTC from a single institution (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSK]). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to data collection. EQUATOR guidelines were followed12. For this retrospective research protocol #16-812, informed consent was waived. Systemic chemotherapy regimens were determined by the treating oncologist. Most patients received systemic therapy; however some patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHC) were treated with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), consisting of continuous infusion of floxuridine into the liver circulation through a surgically implanted hepatic pump, often in combination with concurrent systemic chemotherapy (primarily gemcitabine + platinum). Patients with previous clinical tumor genetic profiling or with available banked tumor tissue/pathological slides for retrospective genomic analysis were included. A pathologist blinded to tumor genotype reviewed slides to confirm the diagnosis. Resected tumors were staged according to the 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC’s) classification. In unresected patients, staging was based on imaging and available pathology. The reasons for unresectability included locally advanced disease (multifocal liver disease, lymph node metastasis, or extensive vascular and/or biliary involvement) or distant metastatic disease.

Genomic Analysis:

Tumor and matched normal tissue from patients were profiled to identify somatic genomic alterations with MSK-IMPACT (Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets; NCT01775072), as described previously13. MSK-IMPACT is a hybridization capture-based NGS assay designed to sequence all exons and selected introns of potentially actionable genes based on current therapies. All specimens were sequenced in the clinical laboratories of the Molecular Diagnostics Service. All slides were re-reviewed by experienced attending pathologists to identify tumor and normal liver tissue for DNA extraction. All samples had >60% tumor content; DNA isolated from primary tumor and matched normal liver tissue or blood was sequenced. Classes of genomic alterations were determined and called against the patient’s matched normal sample. 73% (722/983) of biopsies for sequencing were from a primary site, 27% (261/983) were from a metastatic site and 2 patients were unknown and therefore excluded from this denominator. We examined somatic mutations that were considered oncogenic drivers based on OncoKB. Genomic data from all patients were analyzed simultaneously.

Statistical Analysis:

Disease and treatment characteristics were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Fisher exact test, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, Pearson Chi Squared test, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare groups.

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the date of the first recurrence after surgery, last follow up, or death (whichever occurred first) for patients that were resectable. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from date of diagnosis until date of first progression, last follow up, or death (whichever occurred first) for unresectable patients. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the date of last contact or death. Follow up time was calculated as the median time from date of diagnosis until last contact for survivors. Time-to-event outcomes were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared between subgroups using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the univariate and multivariable relationships between covariates of interest and OS, RFS, and PFS, respectively. Patients who died without recurrence or progression were censored at the date of death.

Genes tested in co-mutation analysis with KRAS mutation were selected a priori. Using Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for tumor type, we assessed the relationship between TP53 or SF3B1 co-mutation with mutant KRAS and OS by resection status. P-values were 2-sided and considered statistically significant if less than 0.05. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.3.

RESULTS

Frequency of KRAS variants and association with clinicopathological features

A total of 985 patients with KRAS status available and biopsy-proven EHC, IHC, or GB treated between 2004-2022 were included in this cohort; the median follow-up time in survivors was 18 months (interquartile range [IQR] 11, 31). Of these, 149 (15%) had a KRAS mutation (EHC n=73; IHC n=60; GB n=16; Supplementary Figure 1). Overall median age (years) was similar in unresectable (64; [IQR: 56,72]) and resectable patients (63; [IQR: 53,71]); there were more female resectable EHC patients (62%) while both unresectable and resectable GB patients were 72% and 68% male respectively (Table 1). Additional demographic information is summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Tumor Type and Surgery Status

| Unresectable | Resectable | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 5721 |

IHC, N = 3951 |

EHC, N = 711 |

GB, N = 1061 |

p-value2 | Overall, N = 4131 |

IHC, N = 1751 |

EHC, N = 1191 |

GB, N = 1191 |

p-value2 |

| Age at diagnosis | 64 (56, 72) | 63 (55, 70) | 68 (61, 74) | 65 (56, 73) | 0.001 | 63 (53, 71) | 62 (52, 71) | 64 (54, 70) | 63 (53, 72) | 0.8 |

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Female | 274 (48%) | 207 (52%) | 37 (52%) | 30 (28%) | 197 (48%) | 85 (49%) | 74 (62%) | 38 (32%) | ||

| Male | 298 (52%) | 188 (48%) | 34 (48%) | 76 (72%) | 216 (52%) | 90 (51%) | 45 (38%) | 81 (68%) | ||

| Race | 0.065 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| White | 468 (82%) | 331 (84%) | 57 (80%) | 80 (75%) | 314 (77%) | 144 (83%) | 95 (81%) | 75 (64%) | ||

| Black | 27 (4.7%) | 15 (3.8%) | 3 (4.2%) | 9 (8.5%) | 34 (8.4%) | 7 (4.0%) | 7 (6.0%) | 20 (17%) | ||

| Asian | 56 (9.8%) | 32 (8.1%) | 11 (15%) | 13 (12%) | 48 (12%) | 17 (9.8%) | 13 (11%) | 18 (15%) | ||

| Other | 19 (3.3%) | 15 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.8%) | 11 (2.7%) | 5 (2.9%) | 2 (1.7%) | 4 (3.4%) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| BMI | 27.0 (23.5, 31.1) | 27.4 (23.6, 31.4) | 25.4 (22.5, 27.9) | 27.6 (23.4, 31.5) | 0.011 | 26.4 (23.1, 30.2) | 26.4 (23.6, 30.9) | 26.2 (22.6, 28.9) | 26.4 (23.1, 31.1) | 0.2 |

| Unknown | 7 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Alcohol | 0.010 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Never | 456 (82%) | 307 (80%) | 52 (78%) | 97 (92%) | 310 (77%) | 127 (75%) | 82 (70%) | 101 (86%) | ||

| Active | 89 (16%) | 69 (18%) | 12 (18%) | 8 (7.6%) | 86 (21%) | 41 (24%) | 33 (28%) | 12 (10%) | ||

| Former | 9 (1.6%) | 6 (1.6%) | 3 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.0%) | 2 (1.2%) | 2 (1.7%) | 4 (3.4%) | ||

| Unknown | 18 | 13 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Tobacco | 0.032 | 0.6 | ||||||||

| Never | 276 (49%) | 179 (46%) | 32 (46%) | 65 (61%) | 211 (51%) | 83 (48%) | 62 (52%) | 66 (55%) | ||

| Active | 55 (9.7%) | 44 (11%) | 7 (10%) | 4 (3.8%) | 40 (9.7%) | 21 (12%) | 9 (7.6%) | 10 (8.4%) | ||

| Former | 236 (42%) | 168 (43%) | 31 (44%) | 37 (35%) | 161 (39%) | 70 (40%) | 48 (40%) | 43 (36%) | ||

| Unknown | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Perineural invasion 3 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| No | 149 (40%) | 93 (63%) | 16 (14%) | 40 (38%) | ||||||

| Yes | 219 (60%) | 55 (37%) | 99 (86%) | 65 (62%) | ||||||

| Unknown | 45 | 27 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Lymphovascular invasion 3 | 0.12 | |||||||||

| No | 136 (35%) | 65 (40%) | 32 (28%) | 39 (35%) | ||||||

| Yes | 250 (65%) | 97 (60%) | 82 (72%) | 71 (65%) | ||||||

| Unknown | 27 | 13 | 5 | 9 | ||||||

| Clinical stage at treatment initiation | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 (0.4%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 147 (36%) | 54 (31%) | 51 (43%) | 42 (36%) | ||

| 2 | 81 (14%) | 65 (17%) | 12 (17%) | 4 (3.8%) | 100 (24%) | 63 (36%) | 16 (13%) | 21 (18%) | ||

| 3 & 4 | 487 (85%) | 326 (83%) | 59 (83%) | 102 (96%) | 164 (40%) | 57 (33%) | 52 (44%) | 55 (47%) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Presence of suspicious node on imaging (clinically +/−) | <0.001 | 0.041 | ||||||||

| No | 216 (40%) | 131 (35%) | 37 (53%) | 48 (51%) | 243 (79%) | 122 (81%) | 86 (82%) | 35 (66%) | ||

| Yes | 328 (60%) | 248 (65%) | 33 (47%) | 47 (49%) | 65 (21%) | 28 (19%) | 19 (18%) | 18 (34%) | ||

| Unknown | 28 | 16 | 1 | 11 | 105 | 25 | 14 | 66 | ||

| Tumor grade | 0.049 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 1 | 13 (2.7%) | 9 (2.6%) | 3 (6.1%) | 1 (1.2%) | 28 (6.9%) | 6 (3.6%) | 14 (12%) | 8 (6.7%) | ||

| 2 | 234 (49%) | 164 (48%) | 31 (63%) | 39 (45%) | 229 (57%) | 105 (63%) | 73 (62%) | 51 (43%) | ||

| 3 | 231 (48%) | 170 (50%) | 15 (31%) | 46 (53%) | 146 (36%) | 56 (34%) | 30 (26%) | 60 (50%) | ||

| Unknown | 94 | 52 | 22 | 20 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Tumor size pathology (cm) | 3.1 (2.7, 4.0) | 9.0 (6.8, 11.2) | 3.2 (3.0, 3.4) | 3.0 (2.5, 3.6) | 0.10 | 3.50 (2.40, 6.00) | 5.50 (3.50, 7.70) | 2.30 (1.78, 3.20) | 3.50 (2.40, 4.50) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 552 | 393 | 69 | 90 | 35 | 6 | 7 | 22 | ||

| Multifocal disease | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 205 (36%) | 83 (21%) | 46 (66%) | 76 (75%) | 336 (82%) | 122 (70%) | 114 (97%) | 100 (85%) | ||

| Yes | 360 (64%) | 311 (79%) | 24 (34%) | 25 (25%) | 75 (18%) | 53 (30%) | 4 (3.4%) | 18 (15%) | ||

| Unknown | 7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

Median (IQR); n (% of known values)

Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Pearson's Chi-squared test; Fisher's exact test

Parameters only presented for resectable patients given lack of data availability for unresectable patients.

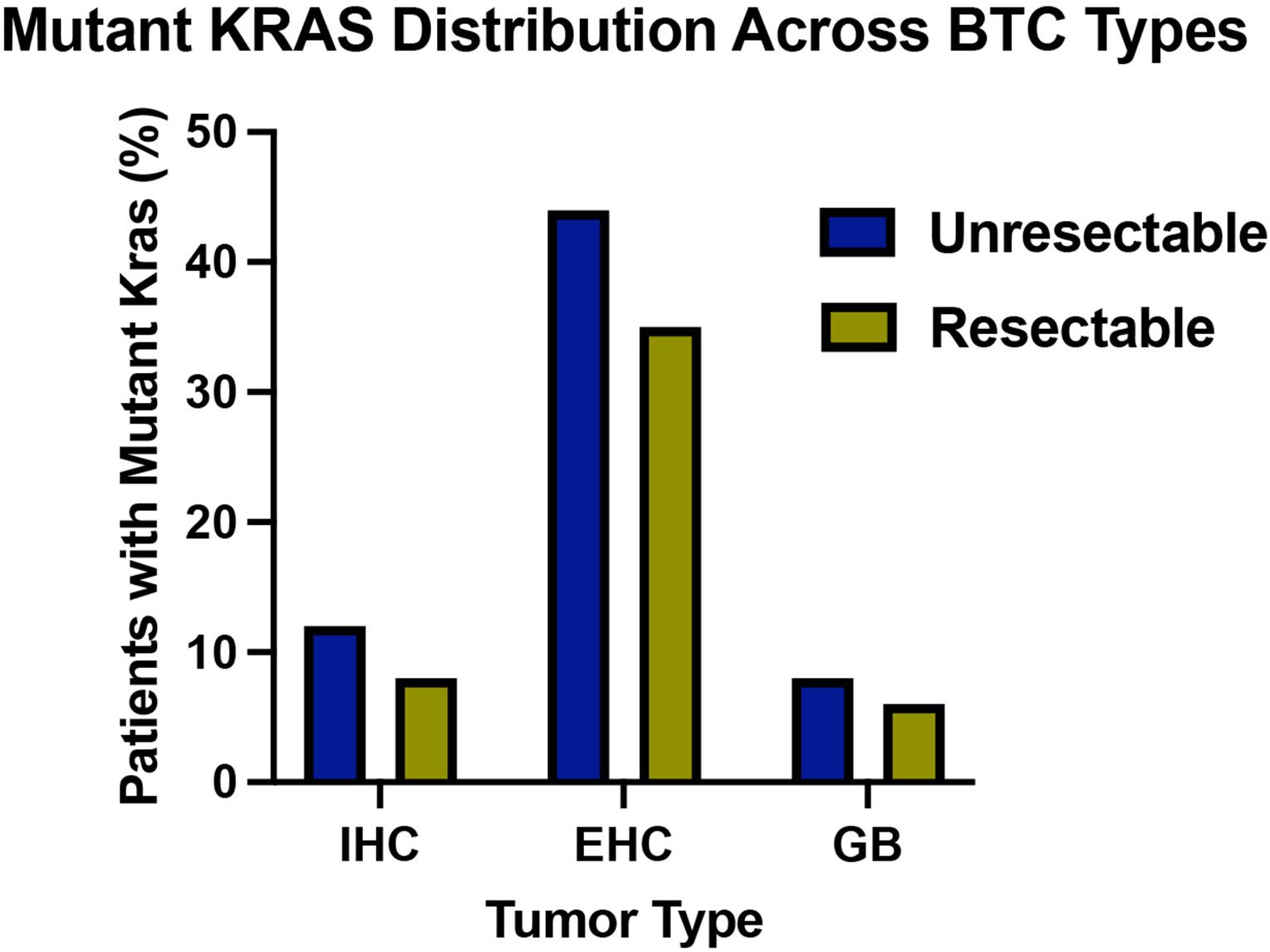

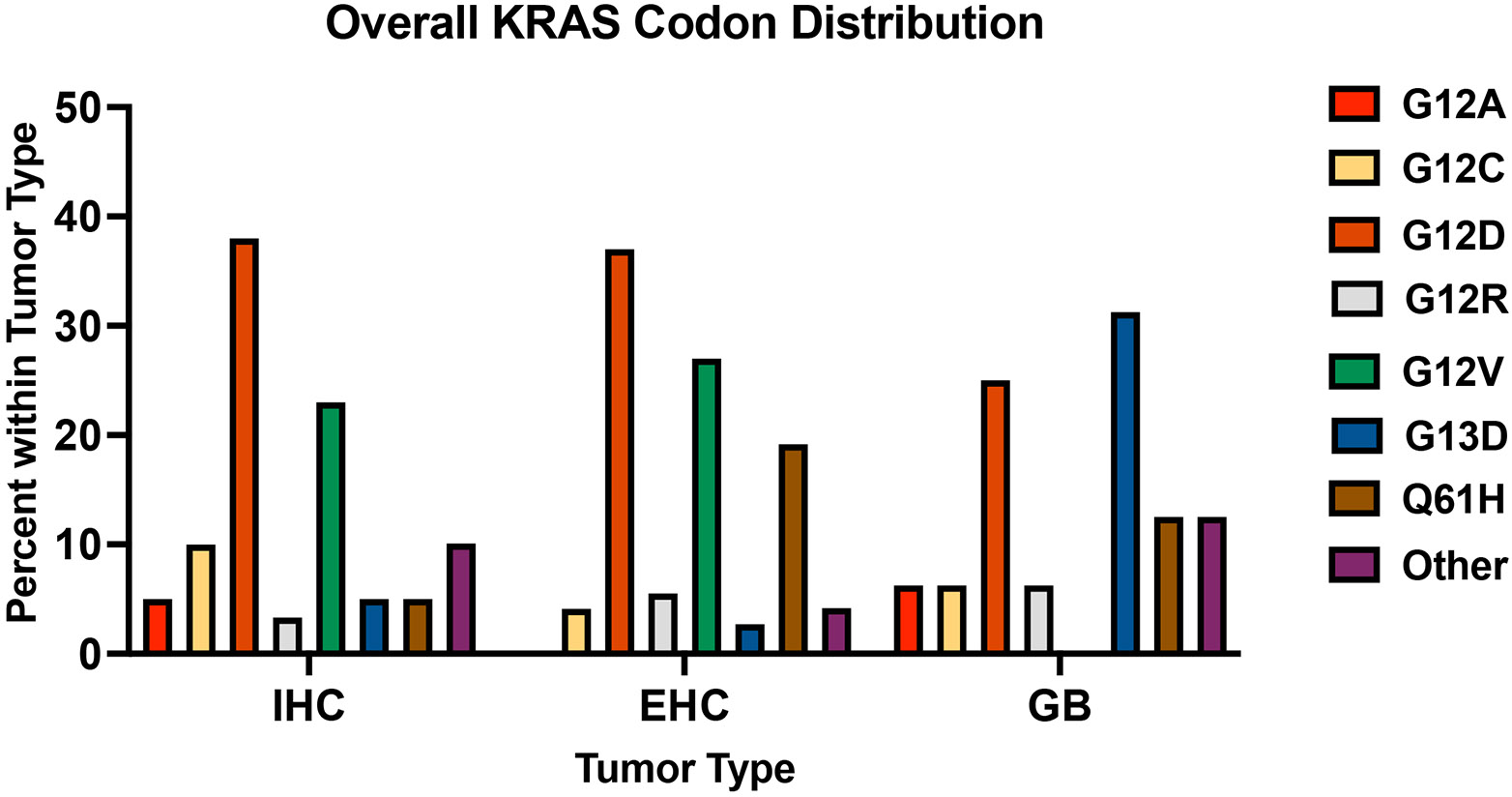

For the entire cohort, KRAS mutations were present to a similar extent in unresectable (n=86/572, 15%) and resectable (n=63/413, 15%) BTC cases (Supplementary Figure 1). For the individual subtypes, KRAS mutations were more common in unresectable (n=31/71, 44%) and resectable (n=42/119, 35%) EHC compared to IHC (unresectable n=46/395, 12%; resectable n=14/175, 8.0%) and GB (unresectable n=9/106, 8.5%; resectable n=7/119, 5.9%) (Figure 1A). Of those that had a KRAS mutation, KRAS G12D mutations were most common in IHC (n=23/60, 38%) and EHC (n=27/73, 37%), whereas G13D mutations were most common in GB (n=5/16, 31%). Of note, no G12V variants were observed in GB. Few patients had a KRAS G12C mutation (IHC: n=6/60, 10%; EHC: n=3/73, 4.1%; GB: n=1/16, 6.3%). (Figure 1B). Specific KRAS mutations had similar frequencies in unresectable and resectable cases (Figure 1C, 1D). We were also identified several uncommon KRAS variants including A146T and D92V (both present only in unresectable IHC) as well as G60D and others (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1: Frequency of KRAS alterations in biliary tract cancers.

(A) Frequency of mutant KRAS in patients with unresectable IHC (n=46/395, 12%), EHC (n=31/71, 44%), and GB (n=9/106, 8%), and resectable IHC (n=14/175, 8%), EHC (n=42/119, 35%), and GB (n=7/119, 6%). (B) Frequency of specific KRAS codon alterations in IHC (n=60), EHC (n=73), and GB (n=16) reported as percentage of patients with each KRAS alteration out of total number of KRAS mutant tumors, stratified by tumor type. Other = other KRAS variants. (C, D) Frequency of the most common KRAS codon alterations in IHC (C; n=46 unresectable, n=14 resectable,) and EHC (D, n=31 unresectable, n= 42 resectable,).

KRAS Co-Occurring Mutations

Using available genomic data, we found SF3B1 mutations co-occurred with mutant KRAS only in IHC (n=5/60, 8.3%; p=0.007) and EHC (n=8/73, 11%; p=0.014) (Table 2). TP53 mutations tended to occur more often with wild-type KRAS in EHC (n=67/117, 57%; p=0.030) and GB (n=137/209, 66%; p=0.006), but not in IHC. ARID1A co-occurred more often with wild-type KRAS in EHC (n=29/117, 25%; p=0.004), but with mutant KRAS in GB (8/16, 50%; p=0.009) (Table 2). Finally, co-occurrence between KRAS and SMAD4 approached marginal significance for IHC (n=4/60, 6.7%, p=0.077) and GB (n=7/16, 44%; p=0.052), similar to previous reports14. Additional information stratifying co-occurrence patterns by tumor location and resection status can be found in Supplementary Table 2. Additionally, in patients that had a KRAS mutation in our analysis population, none had an FGFR fusion, and we found no relationship between MSI and KRAS mutation status (Supplementary Table 3).

TABLE 2:

Co-Mutations By Tumor Type

| IHC | EHC | GB | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comutation1 | Overall, N = 5702 |

KRAS Mut, N = 602 |

KRAS WT, N = 5102 |

p-value3 | Overall, N = 1902 |

KRAS Mut, N = 732 |

KRAS WT, N = 1172 |

p-value3 | Overall, N = 2252 |

KRAS Mut, N = 162 |

KRAS WT, N = 2092 |

p-value3 |

| TP53 | 117 (21%) | 14 (23%) | 103 (20%) | 0.6 | 97 (51%) | 30 (41%) | 67 (57%) | 0.030 | 142 (63%) | 5 (31%) | 137 (66%) | 0.006 |

| SMAD4 | 16 (2.8%) | 4 (6.7%) | 12 (2.4%) | 0.077 | 34 (18%) | 14 (19%) | 20 (17%) | 0.7 | 49 (22%) | 7 (44%) | 42 (20%) | 0.052 |

| ARID1A | 102 (18%) | 9 (15%) | 93 (18%) | 0.5 | 35 (18%) | 6 (8.2%) | 29 (25%) | 0.004 | 49 (22%) | 8 (50%) | 41 (20%) | 0.009 |

| SF3B1 | 13 (2.3%) | 5 (8.3%) | 8 (1.6%) | 0.007 | 10 (5.3%) | 8 (11%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.014 | 3 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.4%) | >0.9 |

| TGFBR2 | 14 (2.5%) | 3 (5.0%) | 11 (2.2%) | 0.2 | 14 (7.4%) | 8 (11%) | 6 (5.1%) | 0.13 | 4 (1.8%) | 1 (6.2%) | 3 (1.4%) | 0.3 |

| IDH1 | 134 (24%) | 10 (17%) | 124 (24%) | 0.2 | 4 (2.1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.4%) | 0.3 | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.0%) | >0.9 |

| CDKN2A | 13 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (2.5%) | 0.4 | 18 (9.5%) | 7 (9.6%) | 11 (9.4%) | >0.9 | 21 (9.3%) | 2 (12%) | 19 (9.1%) | 0.7 |

n (%)

Pearson's Chi-squared test; Fisher's exact test

We focused on co-occurring mutation associations with OS first for KRAS and TP53 given that TP53 is a well characterized BTC driver and second for KRAS and SF3B1, since we identified it as a novel co-occurrence. After adjusting for tumor type, unresectable patients with wild-type KRAS and mutant TP53 had worse survival compared to those wild-type for both (HR=1.43; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.83; p=0.005). Additionally, the combination of mutant KRAS and mutant TP53 in unresectable patients was particularly deleterious. Unresectable patients with both mutant TP53 and mutant KRAS had significantly worse survival than those wild-type for both (HR=1.92; 95% CI: 1.15, 3.18; p=0.012) after adjusting for tumor type. Resectable patients with mutant KRAS and wild-type TP53 had worse overall survival compared to those that were wild-type for both (HR=1.82; 95% CI: 1.04, 3.18; 0.036) after adjusting for tumor type (Supplementary Table 4). Interestingly, we also found that resectable patients with mutant KRAS and mutant SF3B1, after adjusting for tumor type, had significantly worse overall survival compared to those with wild-type for both (HR=4.04; 95% CI: 1.45, 11.2; p=0.007) (Supplementary Table 5). Taken together, KRAS co-mutational partners are distinct per BTC subtype and their co-mutational patterns are uniquely associated with overall survival.

KRAS Codon Mutations and Survival

KRAS mutations were associated with worse overall survival (OS) (p=0.041) and worse progression free survival (PFS) (p=0.042) in unresectable BTC (Supplementary Figure 2). In IHC, KRAS mutations were associated with shorter OS in both unresectable (mutant KRAS median: 12 months, 95% CI: 9.8, 18; WT median: 19 months, 95% CI:18, 24; log-rank p<0.001) and resectable disease (mutant KRAS median: 27 months, 95% CI: 22, not reached; WT median: 61 months, 95% CI: 53, 80; log-rank p=0.007) (Figure 2A, 2B). In EHC and GB patients, KRAS mutations were not associated with worse OS in unresectable or resectable cases (Figure 2C-2F). We then assessed whether survival differences in IHC could be attributed to a specific KRAS variant. Interestingly, KRAS G12 mutations were associated with worse OS in IHC patients with unresectable tumors compared to other KRAS mutations and wild-type KRAS (KRAS G12 median: 11 months, 95% CI: 9.7, 18; KRAS Other median: 18 months 95% CI: 5.8, not reached; log-rank p<0.001). This was also true for those with resectable disease (KRAS G12 median: 27 months, 95% CI: 22, not reached; KRAS Other median: 47 months; 95% CI [not reached, not reached]; p=0.011) (Figure 3A, B). However, KRAS G12 mutations were not associated with shorter OS in EHC or GB patients when compared to other KRAS mutations and KRAS wild-type (Figure 3C-3F). In terms of RFS for resectable patients and PFS for unresectable, only KRAS G12 mutations in unresectable IHC trended toward worse outcomes (Supplementary Figure 3A-3F).

Figure 2: Association between KRAS mutations and survival.

(A, B) Kaplan-Meier curves for unresectable (A) and resectable (B) IHC patients showing overall survival stratified by tumor KRAS status, either wild-type (WT) or mutated (KRAS). (C, D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing overall survival of WT KRAS (WT) versus mutant KRAS (KRAS) unresectable(C) and resectable (D) EHC tumors. (E, F) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing overall survival of WT KRAS (WT) versus mutant KRAS (KRAS) unresectable (E) and resectable (F) GB tumors.

Figure 3: Association between KRAS variants and survival.

(A, B) Kaplan-Meier curves for unresectable (A) and resectable (B) IHC patients showing overall survival stratified by tumor KRAS status, either KRAS wild-type (WT), KRAS G12 mutated (KRAS G12), and other KRAS codon variants (Other KRAS). (C, D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing overall survival of WT versus KRAS G12 and Other KRAS unresectable (C) and resectable (D) EHC tumors. (E, F) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing overall survival of WT KRAS, KRAS G12, and Other KRAS unresectable (E) and resectable (F) GB tumors. (G) Kaplan-Meier curve for all IHC patients showing overall survival of tumors with WT KRAS versus KRAS G12C, KRAS G12D, KRAS G12V, and other KRAS mutations.

On univariate analysis, KRAS G12 mutations were associated with worse OS in IHC patients (HR=2.3, 95% CI=1.6-3.2; p<0.001), but not in EHC or GB (Supplementary Table 6). In our data, OS was shorter for EHC and GB than IHC. We thus assessed whether KRAS G12 mutations were a prognostic indicator separately in IHC, EHC, and GB patients. On multivariate analysis adjusting for age at diagnosis, clinical stage, multifocal disease, and curative surgery status, KRAS G12 mutations remained a prognostic indicator only in IHC patients (HR=1.98, 95% CI=1.41-2.79; p<0.001) (Table 3). OS also differed within mutant KRAS G12, with KRAS G12D and G12V variants exhibiting shorter OS compared to KRAS G12C variant, other mutant KRAS mutations, and wild-type KRAS (log-rank p < 0.001; Figure 3G). OS at 24 months in IHC patients with mutated KRAS G12D was 20% (95% CI: 8.7%, 48%) compared to at least 40% for KRAS G12C (40%, 95% CI: 14%,100%), G12V (41%, 95% CI: 21%, 78%), other KRAS (44%, 95% CI: 25%, 80%), and WT (56%, 95% CI: 51%, 61%) at this same time point.

TABLE 3:

Multivariable Associations with Overall Survival by Tumor Type

| IHC | EHC | GB | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | Event N |

HR1 | 95% CI1 | p-value | N | Event N |

HR1 | 95% CI1 | p-value | N | Event N |

HR1 | 95% CI1 | p-value |

| KRAS variant (3 groups) | 567 | 357 | 190 | 106 | 224 | 124 | |||||||||

| WT | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||||

| KRAS G12 | 1.98 | 1.41, 2.79 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 0.47, 1.16 | 0.2 | 0.64 | 0.20, 2.07 | 0.5 | ||||||

| Other KRAS | 1.24 | 0.59, 2.63 | 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.33, 1.21 | 0.2 | 1.73 | 0.80, 3.76 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis | 567 | 357 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 | 0.12 | 190 | 106 | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.04 | 0.014 | 224 | 124 | 1.02 | 1.01, 1.04 | 0.005 |

| Clinical stage | 567 | 357 | <0.001 | 190 | 106 | 0.047 | 224 | 124 | 0.094 | ||||||

| 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||||

| 2 | 1.21 | 0.71, 2.05 | 0.98 | 0.47, 2.04 | 0.63 | 0.27, 1.49 | |||||||||

| 3 & 4 | 2.81 | 1.68, 4.70 | 1.71 | 0.96, 3.06 | 1.39 | 0.79, 2.47 | |||||||||

| Curative surgery status | 567 | 357 | <0.001 | 190 | 106 | <0.001 | 224 | 124 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Resectable | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||||

| Unresectable | 2.54 | 1.90, 3.39 | 3.70 | 2.28, 5.99 | 2.94 | 1.86, 4.64 | |||||||||

HR = Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

DISCUSSION

KRAS is the most frequently mutated oncogene in cancer15. Despite progress investigating KRAS mediated oncogenesis, there remains outstanding questions about the clinical consequences of particular KRAS mutations and the ideal therapeutic strategy to target them.

Oncogenic KRAS mutations were previously considered to have overlapping downstream effects, regardless of the specific variant. However, recent data suggests that distinct KRAS variants have unique functional and clinical consequences. In colorectal cancer, KRAS G12 variants are uniquely predictive of worse survival16 and are thought to represent a distinct biological state, as patients with KRAS G13 mutant disease respond significantly better to anti-EGFR therapies17 and trifluridine/tipiracil therapy9. These clinical differences are meaningful as distinct KRAS variants may have differing biological activities. In IHC, groups have shown tissue specific activation of KRAS G12D is sufficient to develop IHC and disease latency is shortened with a concomitant P53 mutation18. Mutations at glycine 13 affect GTPase activity, cycling, and interaction with effector proteins differently than those as position 12 or 6119. Similarly, we show KRAS G13 and KRAS G12 disease are indeed different clinical entities: within BTCs, the anatomical tumor location in which these mutations occur affects overall survival.

In our evaluation of KRAS mutations in BTC subtypes using a large, robustly annotated dataset, we observed a 15% overall incidence of KRAS mutations, with EHC having the highest incidence, similar to prior reports14,20,21. The KRAS G12 mutation was previously reported to be associated with worse OS and RFS in resectable IHC tumors, though never explored broadly across BTC tumor types11. In the current study, KRAS mutations were present in 11% of IHC tumors and most were G12D. Although KRAS mutations were significantly more common in EHC, we show that KRAS G12 mutated IHC patients (not EHC or GB) have worse OS in both unresectable and resectable disease. When correcting for age, clinical stage, and other relevant clinicopathologic features, KRAS G12 mutations were unique prognostic indicators for worse overall survival only in IHC. This suggests KRAS G12 mutated IHC is an aggressive, distinct form of the disease and is strongly associated with poor OS, regardless of resection status, and especially in those with G12D or G12V mutations, the latter of which was not observed in GB. Thus, for each biliary tract cancer subtype, an ideal KRAS signaling level may be required for carcinogenesis. Specific KRAS variants may serve as a biological toggle to attenuate downstream consequences of KRAS signaling. Our study lays the groundwork for further interrogation into the oncogenic signaling environment established by these KRAS variants as unique nodes may be identified and further targeted in combination therapies. Transcriptional and epigenetic analysis should be performed on tumors harboring these mutations to determine potential targetable vulnerabilities in IHC tumors as compared to genetically similar EHC and GB tumor types. Additionally, given the role of hepatic artery infusion pump (HAIP) treatment in unresectable cholangiocarcinoma, future studies should investigate the association with KRAS variants and survival in this distinct patient population. The data further support the observation that each subtype of BTC should be evaluated separately with regard to treatment paradigms and RAS directed therapeutics.

Though KRAS is a known factor in BTC pathogenesis, inhibition of downstream signaling (ex: MEK) has only modest clinical activity22,23. Recently, there have been breakthroughs in KRAS variant targeting agents with the advent of variant specific KRAS G12C inhibitors. Sotorasib has shown anticancer activity in patients with advanced KRAS G12C mutated pancreatic cancer and adagrasib, a KRAS G12C inhibitor with a longer half-life, showed durable clinical benefit non-small-cell lung cancer 24-26. KRAS G12C inhibitors are being used in combination with pembrolizumab in non-small-cell-lung cancer patients27 and cetuximab in colorectal cancer28 . Preclinical studies demonstrate utility in KRAS G12C inhibition coupled with mTOR and IGF1R inhibition in lung adenocarcinoma29. There is significant excitement over the development of additional KRAS variant targeting agents, some of which are currently in development for KRAS G12D30.

Pan-RAS inhibitors (including RMC-6236) have shown promising clinical efficacy in lung and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, especially in patients with KRAS G12 mutant disease31. These agents work uniquely as active state-selective inhibitors, binding active KRAS with immunophilin cyclophilin A, sterically blocking RAS-effector interactions. These compounds should be investigated in IHC patients. Stratifying which patients would benefit from specific KRAS variant inhibition will be of paramount importance to achieve robust clinical outcomes. Our data suggest patients with KRAS G12 mutant IHC, especially G12D, should be considered high risk and may be candidates for clinical trials of allele-specific or pan RAS inhibitors.

Our data revealed co-mutational patterns in KRAS mutant disease, including a novel association with SF3B1 in IHC and EHC, suggesting a role for aberrant splicing in KRAS G12 mutant IHC/EHC tumorigenesis. There is high association in co-mutations between patients with resectable and unresectable disease. On multivariate analysis, after adjusting for tumor type, resectable patients with KRAS MUT and TP53 WT had significantly worse overall survival compared to those with WT for both. While KRAS and SF3B1 co-mutations have not previously been described in BTCs, SF3B1 is commonly mutated in myelodysplastic syndromes and KRAS co-mutations are associated with significantly worse overall survival than KRAS wild-type patients32. Taken together, this provides rationale for pre-clinical assessment of combinatorial therapies targeting aberrant spliceosome activity in KRAS mutant IHC and EHC.

Our study is limited by small patient numbers (for KRAS variants, especially in EHC and GB) and its retrospective nature in a single institution, warranting further validation with an external cohort. Overall faster disease kinetics for EHC and GB in this smaller cohort may obscure the prognostic effect of certain KRAS variants. Tumor samples were taken at a single timepoint and location, not accounting for potential biological consequences of intratumor heterogeneity. Heterogeneous stromal content, especially in EHC, could have introduced ascertainment bias in KRAS variant calling. Larger cohort studies will be necessary to delineate co-mutational patterns and to better assess survival differences.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrate clinically relevant differences in prevalence among KRAS variants in subtypes of BTC utilizing one of the largest single-center clinically annotated genomic datasets. We demonstrate that KRAS mutations commonly co-occur with SF3B1 and utilizing a multivariable analysis, show KRAS G12 mutations are a prognostic indicator for inferior OS in IHC but not EHC or GB tumors, regardless of resection status. KRAS G12 mutations, especially G12D and G12V account for most of this difference. The significance of these data is paramount as we enter the era of effective KRAS therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

CONTEXT SUMMARY.

Key Objective:

Are specific KRAS variants associated with survival outcomes and distinct genomic alterations in biliary tract cancer (BTC) subtypes?

Knowledge Generated:

In both resectable and unresectable patients, KRAS G12 mutations are associated with worse overall survival in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHC), not extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHC) or gallbladder adenocarcinoma (GB), as compared to WT or other KRAS variants. Mutations in SF3B1 are a novel co-occurrence with KRAS in IHC and EHC, and co-mutant, resectable patients have worse overall survival after adjusting for tumor type.

Relevance:

This data defines which KRAS alterations are clinically relevant in distinct BTC subtypes. IHC patients with KRAS G12 mutant tumors have high risk disease and a clinical need for variant specific KRAS therapeutic agents. This work also describes a unique co-mutational landscape that provides the basis for future mechanistic work or combinatorial drug studies.

Funding:

WRJ is supported by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health U01 CA238444-01A1 and Foundation for the National Institutes of Health R01EB027498-A1. MG is supported by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health P30 CA008748. RG is supported by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health T32GM007739, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Grayer Fellowship, and the National Institutes of Health 1F30CA284575-01A1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beal EW, Cloyd JM & Pawlik TM Surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: current and emerging principles. J Clin Med 10, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abou-Alfa GK et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 21, 671–684 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu AX et al. Final overall survival efficacy results of ivosidenib for patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma with IDH1 mutation: the phase 3 randomized clinical claridhy trial. JAMA Oncol 7, 1669–1677 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banales JM et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 17, 557–588 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boerner T. et al. Genetic determinants of outcome in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 74, 1429–1444 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridgewater JA, Goodman KA, Kalyan A & Mulcahy MF Biliary Tract Cancer: Epidemiology, Radiotherapy, and Molecular Profiling. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book e194–e203 (2016) doi: 10.1200/EDBK_160831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang L, Guo Z, Wang F & Fu L KRAS mutation: from undruggable to druggable in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6, 386 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Margonis GA et al. Association Between Specific Mutations in KRAS Codon 12 and Colorectal Liver Metastasis. JAMA Surg 150, 722–729 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Haar J. et al. Codon-specific KRAS mutations predict survival benefit of trifluridine/tipiracil in metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat Med 29, 605–614 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marabese M. et al. KRAS mutations affect prognosis of non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line platinum containing chemotherapy. Oncotarget 6, 34014–34022 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou S-L et al. Association of KRAS variant subtypes with survival and recurrence in patients with surgically treated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. JAMA Surg 157, 59–65 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McShane LM et al. REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK). Br J Cancer 93, 387–391 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen B. et al. Genomic characterization of metastatic patterns from prospective clinical sequencing of 25,000 patients. Cell 185, 563–575.e11 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowery MA et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas: potential targets for intervention. Clinical Cancer Research 24, 4154–4161 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simanshu DK, Nissley DV & McCormick F RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell 170, 17–33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RP et al. Specific mutations in KRAS codon 12 are associated with worse overall survival in patients with advanced and recurrent colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 116, 923–929 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tejpar S. et al. Association of KRAS G13D tumor mutations with outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without cetuximab. Journal of Clinical Oncology 30, 3570–3577 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Dell MR et al. KrasG12D and p53 Mutation Cause Primary Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Res 72, 1557–1567 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostrem JML & Shokat KM Direct small-molecule inhibitors of KRAS: from structural insights to mechanism-based design. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15, 771–785 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zen Y. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: typical features, uncommon variants, and controversial related entities. Hum Pathol 132, 197–207 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simbolo M. et al. Multigene mutational profiling of cholangiocarcinomas identifies actionable molecular subgroups. Oncotarget 5, 2839–2852 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bekaii-Saab T. et al. Multi-institutional phase II study of selumetinib in patients with metastatic biliary cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology 29, 2357–2363 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowery MA et al. Binimetinib plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Phase I/II Trial in Patients with Advanced Biliary Cancers. Clinical Cancer Research 25, 937–945 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong DS et al. KRASG12C Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors. N Engl J Med 383, 1207–1217 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strickler JH et al. Sotorasib in KRAS p.G12C-Mutated Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med 388, 33–43 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jänne PA et al. Adagrasib in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring a KRAS G12C Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine 387, 120–131 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jänne PA et al. LBA4 Preliminary safety and efficacy of adagrasib with pembrolizumab in treatment-naïve patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring a KRASG12C mutation. Immuno-Oncology and Technology 16, 100360 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaeger R. et al. Adagrasib with or without Cetuximab in Colorectal Cancer with Mutated KRAS G12C. New England Journal of Medicine 388, 44–54 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molina-Arcas M. et al. Development of combination therapies to maximize the impact of KRAS-G12C inhibitors in lung cancer. Sci Transl Med 11, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang D & Kang R Glimmers of hope for targeting oncogenic KRAS-G12D. Cancer Gene Ther (2022) doi: 10.1038/s41417-022-00561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Jingjing, et al. “Translational and Therapeutic Evaluation of Ras-GTP Inhibition by RMC-6236 in Ras-Driven Cancers.” American Association for Cancer Research, American Association for Cancer Research, 3 June 2024, aacrjournals.org/cancerdiscovery/article/doi/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-24-0027/742968/Translational-and-Therapeutic-Evaluation-of-RAS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma L. et al. A Novel Prognostic Scoring Model for Myelodysplastic Syndrome Patients With SF3B1 Mutation. Front Oncol 12, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.