Abstract

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome and sexually transmitted infections remain critical public health challenges in Sierra Leone, with major implications for morbidity and mortality. Understanding the trends in the prevalence of these infections and identifying sex-based disparities are essential for designing effective, evidence-based interventions. This study examined the trends in age-standardized prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome and sexually transmitted infections in Sierra Leone in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2019.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was conducted using age-standardized prevalence rates (per 100,000 population) of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome and sexually transmitted infections from the World Health Organization health equity assessment toolkit database at five time points (2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2019). Inequality measures, including Difference (D), Ratio (R), Population Attributable Fraction (PAF), and Population Attributable Risk (PAR), were calculated to assess absolute and relative disparities between sexes. Confidence intervals (CI) were reported for all estimates to ensure robustness of results.

Results

The age-standardized prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome and sexually transmitted infections in Sierra Leone showed a steady decline, from 25,995.3 per 100,000 population in 2000 to 25,705.5 in 2019. However, sex-disaggregated analysis revealed disparities, with females consistently experiencing higher prevalence rates than males across all years. In 2019, the prevalence for females was 34,548.5 per 100,000 population (95% CI: 30,887.3–38,496.7), compared to 16,734.0 per 100,000 population for males (95% CI: 14,674.0–19,020.4). The inequality ratio remained constant at 2.1, indicating that females consistently bore more than twice the burden compared to males. The absolute difference between sexes decreased slightly over time, from 17,962.9 per 100,000 population in 2000 to 17,814.5 per 100,000 population in 2019.

Conclusions

Despite the decline in the prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome and sexually transmitted infections in Sierra Leone between 2000 to 2019, sex-based disparities remain substantial, with females consistently experiencing a higher burden than males. These findings underscore the need for sex-sensitive policies and interventions to address the causes of these disparities. Strengthening health systems, promoting gender equity, and implementing targeted prevention programs are essential to reducing the overall prevalence and achieving health equity in Sierra Leone.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Sexually transmitted infections, Sex disparities, Prevalence, Inequality measures, Sierra Leone, WHO health equity assessment toolkit

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) constitute global health threats, with sub-Saharan Africa bearing 67% of new HIV infections and 42% of STI cases worldwide [1, 2]. These infections disproportionately affect women and girls, who account for 63% of new HIV infections in the region due to biological susceptibility, gender-based violence, and limited sexual autonomy [3, 4]. In Sierra Leone a post-conflict nation ranked 182 out of 193 countries globally on the Human Development Index has faced substantially challenges exacerbated by fragile health systems, with only 3.6 physicians per 100,000 population and 54% healthcare access in rural areas [5, 6]. The country's HIV prevalence of 1.4% masks severe disparities with female sex workers face 8.4 times higher risk, while adolescent girls (15–24 years) account for 80% of new infections [7, 8]. Concurrently, STI prevalence reaches 21.6% among reproductive-aged women, with syphilis alone contributing to 15% of stillbirths [9]. These dual epidemics perpetuate cycles of poverty, as HIV/STI-related absenteeism costs Sierra Leone's economy an estimated 2.3% of GDP annually [10].

Previous studies have shown the burden of HIV/AIDS and STIs at the global and regional levels, highlighting the role of socioeconomic determinants, gender-based violence, and healthcare access in shaping disease prevalence [11, 12]. For example, UNAIDS has consistently reported higher HIV prevalence among women in sub-Saharan Africa, driven by intersection vulnerabilities such as poverty, limited education, and cultural norms that reduce womens' autonomy in sexual and reproductive health decision-making [1, 2]. Studies have also shown that men are less likely to access HIV testing and treatment services, resulting in delayed diagnoses and poorer health outcomes [13, 14]. Despite these insights, most research has focused on national or regional averages, often neglecting the granular, sex-disaggregated analysis of age-standardized prevalence rates. Specifically in Sierra Leone, existing studies have primarily relied on fragmented or outdated datasets, limiting the ability to capture the full scope of sex and age-related disparities in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence [15–20]. Furthermore, while global initiatives such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasize the importance of reducing health inequalities, there remains a paucity of evidence to guide targeted interventions in Sierra Leone.

This study uses the application of World Health Organization Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (WHO HEAT) to analyse sex-disaggregated, age-standardized HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence in Sierra Leone across two decades (2000–2019). Prevalence is a critical indicator that reflects the number of individuals living with HIV at a specific point in time, providing essential insights into the epidemic's scale and impact. While other measurements such as awareness, testing, antiretroviral therapy uptake, and viral load suppression are vital for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions and the overall health outcomes of individuals living with HIV, prevalence serves as a foundational metric for understanding the disease's demographic and public health implications. By analyzing age-disaggregated prevalence data, we aim to highlight the specific needs of different population segments, thereby informing targeted interventions and resource allocation. Building on recent work documenting provincial STI disparities [9], we incorporate novel inequality metrics (Population Attributable Risk, Ratio) to quantify the preventable burden of sex inequity. Our analysis addresses two evidence gaps identified in Sierra Leone's National HIV Strategic Plan: lack of longitudinal sex-disaggregated data, and limited metrics to prioritize intersectional interventions [21]. By establishing baseline estimates aligned with SDG 3.3, this work directly informs the Ministry of Health's 2021–2025 strategy to reduce HIV/STI disparities by 40% through sex-transformative programming [22].

Methods

Study design and data source

This study employed a cross-sectional design to analyse the age-standardized prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone from 2000 to 2019. Data were sourced from the WHO HEAT, an online interactive platform designed to facilitate the examination, analysis, and reporting of health inequality data. The HEAT platform draws from the Sierra Leone Demographic Health Survey Health Inequality Data Repository, which includes disaggregated health indicators from various global sources. The toolkit is publicly accessible at (https://www.who.int/data/inequality-monitor/assessment_toolkit). For this study, we focused on the sex-standardized prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs (per 100,000 population) as reported in the HEAT database. The data provided by the WHO HEAT platform are pre-processed and nationally representative, ensuring consistency and comparability across time points. All available data points were included in the analysis. However, it is important to note that no additional weighting was applied beyond this standardization process. This approach ensures the comparability of prevalence rates across different age groups while accurately reflecting the underlying data. The data adheres to stringent data processing and quality assurance protocols. Missing data were assessed, and appropriate methods were applied, such as imputation or exclusion, based on the extent and nature of the missing data. Quality checks include validation processes that assess the completeness and accuracy of the data, such as cross-referencing with national health statistics and demographic surveys. Additionally, the WHO employs statistical techniques to identify and correct anomalies or inconsistencies in the data. Before analysis, the data undergoes age-standardization to account for variations in age distribution across populations. These comprehensive quality assurance measures ensure that the data used in our analysis are reliable and accurately reflect the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone.

The WHO HEAT accounted for co-infections by counting each individual infection separately. For instance, individuals diagnosed with both HIV and another STI were included in the prevalence counts for both conditions. This approach enables us to present a detailed overview of the burden of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone, reflecting the true extent of these health issues in the population. We recognize that this method may lead to individuals being counted multiple times; however, it is critical for understanding the epidemiology of co-infections in the context of public health interventions. The analysis included five time points: 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2019. This longitudinal approach enabled a comprehensive evaluation of trends in prevalence and disparities over two decades.

Outcome measure and dimension of inequality

The primary outcome measure was the age-standardized prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs (per 100,000 population). This measure was chosen because it accounts for differences in population age structures, allowing for meaningful comparisons across time points and between subgroups. The dimension of inequality examined in this study was sex, with the population disaggregated into two subgroups: male and female.

Although the WHO HEAT platform supports the analysis of additional dimensions of inequality such as socio-economic status, geographic region, and urban-rural residence, this study focused exclusively on sex-based disparities due to the scope of the available data and the study’s primary objective. The analysis aimed to provide insights into sex-based differences in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs, a critical public health concern in Sierra Leone given the disproportionate burden of these infections among females and the socio-cultural factors influencing health outcomes. Combining HIV/AIDS and STI is grounded in the recognition that HIV and STIs share common transmission pathways and risk factors, making their combined analysis relevant for understanding the overall sexual health landscape in Sierra Leone. By examining these populations together, we aim to highlight the interconnectedness of these health issues, which can inform more effective public health strategies and interventions. While HIV and STIs are distinct, their co-occurrence necessitates an integrated approach to address the comprehensive sexual health needs of the population.

Data analysis

The data analysis for this study was conducted in the WHO HEAT using R version 4.1.0, a widely used statistical computing environment known for its robust data analysis capabilities and extensive package ecosystem. To facilitate the data cleaning and analysis process, custom scripts in R was developed. These scripts were designed to automate the following key tasks:

Data importation

Scripts were created to import data from the WHO HEAT database efficiently, ensuring that all relevant variables were captured.

Data cleaning

Custom functions were implemented to perform checks for missing values, identify outliers, and standardize variable formats. This automation enhanced the efficiency and reproducibility of the data cleaning process.

Age standardization

Specific scripts were utilized to perform age-standardization of prevalence rates, allowing for accurate comparisons across different age groups.

Statistical analysis

Custom scripts were also employed to conduct the statistical analyses necessary for the study, including prevalence calculations and the generation of visualizations.

The rationale for using R and developing custom scripts was to ensure flexibility and precision in the analysis. R's extensive libraries and community support provided us with the tools necessary to perform complex statistical operations, while custom scripts allowed to tailor the data processing steps to the specific requirements of the study. This approach not only streamlined the workflow but also enhanced the reproducibility of the findings.

Data analysis was conducted for individuals aged 15–49 years, using the WHO HEAT software, which facilitates the computation of estimates, confidence intervals (CIs), and summary measures of inequality. The HEAT platform provides tools for generating both absolute and relative measures of inequality, enabling a detailed exploration of disparities. Four measures were used to assess sex-based disparities in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs: Difference (D), Ratio (R), Population Attributable Fraction (PAF), and Population Attributable Risk (PAR).

Difference (D)

This metric quantifies the absolute disparity in prevalence rates between females and males by directly comparing their values, providing a clear indication of the magnitude of inequality in absolute terms.

Ratio (R)

This metric calculates the proportional difference in prevalence rates by dividing the prevalence among females by that of males, offering a relative measure of the disparity.

Population attributable fraction (PAF)

This metric represents the percentage of the overall prevalence attributable to sex-based inequality, reflecting the potential reduction in prevalence if the disparity were eliminated.

Population attributable risk (PAR)

This metric indicates the excess prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs attributable to sex-based inequality in the population, providing an absolute measure of the burden.

These metrics collectively provided a comprehensive understanding of both the magnitude and context of sex-based disparities in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence. It important to note that negative PAF and PAR values indicate that addressing health disparities could lead to a reduction in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence. Specifically, these negative values suggest that certain population groups experienced a lower prevalence of the health outcome than would be expected if disparities were eliminated. In the context of public health interventions, negative PAF and PAR values imply an opportunity for significant health improvements by focusing on reducing disparities; and emphasize the need for equitable health policies that prioritize vulnerable populations. It also guides policymakers in allocating resources effectively, ensuring that interventions are directed toward populations that would benefit the most from reduced disparities.

Estimates and 95% confidence intervals were computed for each subgroup (male and female) and for each year of analysis. The results were presented in tabular and graphical formats to facilitate interpretation and to highlight trends over time. The WHO HEAT platform’s standardized computations ensured robust comparisons across time points and subgroups, enhancing the reliability and validity of the findings. For further details on the inequality measures used, readers are referred to the relevant literature [23–25].

Population growth and demographics

We utilized age-standardization techniques to adjust for changes in population structure and growth. This approach allowed us to compare prevalence rates across different years while controlling for variations in age distribution. Additionally, we referenced demographic data from national censuses to ensure our estimates reflected the evolving population characteristics in Sierra Leone.

Changes in testing practices

We acknowledged that advancements in testing methodologies and increased access to testing services may have impacted reported prevalence rates. To address this, we examined trends in testing coverage and accessibility over the study period. While we did not have specific adjustment factors for testing practices, we discussed these changes in the context of our findings, noting that improved testing could lead to higher reported prevalence rates due to increased detection rather than an actual increase in incidence.

Age standardization

To account for variations in age distribution across different years and ensure comparability of prevalence estimates over time, we employed age standardization in our analysis. The following steps outline the process:

Selection of standard population

We used the WHO’s World Standard Population as the reference for age standardization. This population is widely recognized and facilitates comparisons across different studies and time periods.

Calculation of age-specific rates

We calculated age-specific prevalence rates for HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections for each year of the study. This involved determining the number of cases within specific age groups and dividing by the total population in those age groups.

Application of weights

The age-specific rates were then multiplied by the corresponding weights from the World Standard Population. This step ensured that each age group contributed proportionally to the overall prevalence estimate based on the standard population structure.

Summation of standardized rates

Finally, we summed the weighted age-specific rates to obtain the age-standardized prevalence estimate for each year. This method allowed us to compare prevalence rates across the two decades while controlling for changes in age distribution, thus providing a clearer understanding of trends in HIV/AIDS and STIs over time.

Results

Prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs (age standardized) (per 100 000 population) in Sierra Leone

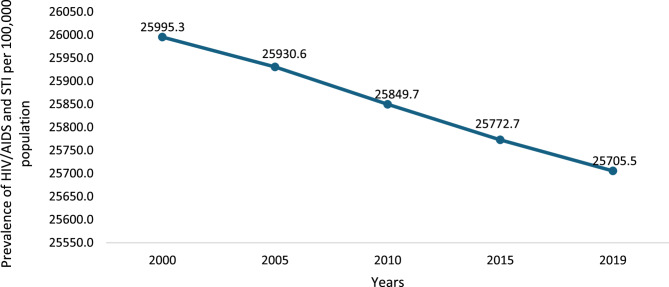

Figure 1 illustrates a steady decline in the age-standardized prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone from 2000 to 2019. In 2000, the prevalence was 25,995.3 per 100,000 population, which decreased to 25,930.6 by 2005. The trend continued with a gradual decline to 25,849.7 in 2010, 25,727 in 2015, and finally 25,705.5 in 2019.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs (age standardized) (per 100 000 population) in Sierra Leone by sex in Sierra Leone, 2000–2019

Table 1 results reveal notable sex-based disparities in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs throughout the study period, with females consistently experiencing higher prevalence rates than males. In 2019, the prevalence for females was 34,548.5 per 100,000 population (95% CI: 30,887.3–38,496.7), compared to 16,734.0 per 100,000 population for males (95% CI: 14,674.0–19,020.4). This pattern of higher prevalence among females was observed across all years. For instance, in 2015, the prevalence for females was 34,487.7 per 100,000 population (95% CI: 30,984.0–38,343.4), while for males, it was 16,783.7 per 100,000 population (95% CI: 14,685.6–19,046.8). Similarly, in 2010, females had a prevalence of 34,511.6 per 100,000 population (95% CI: 31,041.8–38,557.4), compared to 16,666.4 per 100,000 population (95% CI: 14,533.8–18,932.6) for males. This trend persisted in earlier years, with females showing higher prevalence rates in 2005 (34,509.5 per 100,000 population, 95% CI: 30,823.6–38,134.1) versus males (16,616.0 per 100,000 population, 95% CI: 14,542.9–18,740.4), and in 2000 (34,493.3 per 100,000 population, 95% CI: 30,961.8–38,205.3) compared to males (16,530.4 per 100,000 population, 95% CI: 14,467.7–18,807.6).

Table 1.

Trend in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs (age standardized) (per 100,000 population) by sex in Sierra leone, 2000–2019

| Year | Dimension | Sub-group | Estimate | CI- LB | CI-UB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Sex | Female | 34493.3 | 30961.8 | 38205.3 |

| 2000 | Sex | Male | 16530.4 | 14467.7 | 18807.6 |

| 2005 | Sex | Female | 34509.5 | 30823.6 | 38134.1 |

| 2005 | Sex | Male | 16,616 | 14542.9 | 18740.4 |

| 2015 | Sex | Female | 34487.7 | 30,984 | 38343.4 |

| 2015 | Sex | Male | 16783.7 | 14685.6 | 19046.8 |

| 2019 | Sex | Female | 34548.5 | 30887.3 | 38496.7 |

| 2019 | Sex | Male | 16,734 | 14,674 | 19020.4 |

CI-LB Confidence Interval Lower Bound, CI-UB Confidence Interval Upper Bound

Sex inequality on the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone, 2000–2019

Table 2 presents inequality measures related to the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone by sex (male versus female) from 2000 to 2019. The difference between males and females in prevalence remained consistently high throughout the study period, ranging from 17,962.9 per 100,000 population in 2000 to 17,814.5 in 2019, indicating a persistent and substantial gap favoring males. The population attributable fraction values were negative across all years, with the lowest absolute value in 2000 (−36.4%) and the highest in 2019 (−34.9%), suggesting a significant proportion of the prevalence could be reduced if the disparity were addressed. Similarly, the population-attributable risk values were also negative, reflecting the reduction in prevalence (e.g., −9,464.9 per 100,000 in 2000 and − 8,971.5 in 2019) that could be achieved by eliminating inequality. The ratio of prevalence between males and females remained constant at 2.1 across all years, further emphasizing the consistent twofold burden on females compared to males.

Table 2.

Sex inequality on the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs (per 100,000 population) in Sierra Leone by different inequality dimensions, 2000–2019

| Year | Dimension | Measure | Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Sex | D | 17962.9 |

| 2000 | Sex | PAF | −36.4 |

| 2000 | Sex | PAR | −9464.9 |

| 2000 | Sex | R | 2.1 |

| 2005 | Sex | D | 17893.5 |

| 2005 | Sex | PAF | −35.9 |

| 2005 | Sex | PAR | −9314.7 |

| 2005 | Sex | R | 2.1 |

| 2010 | Sex | D | 17845.2 |

| 2010 | Sex | PAF | −35.5 |

| 2010 | Sex | PAR | −9183.3 |

| 2010 | Sex | R | 2.1 |

| 2015 | Sex | D | 17,704 |

| 2015 | Sex | PAF | −34.9 |

| 2015 | Sex | PAR | −8989 |

| 2015 | Sex | R | 2.1 |

| 2019 | Sex | D | 17814.5 |

| 2019 | Sex | PAF | −34.9 |

| 2019 | Sex | PAR | −8971.5 |

| 2019 | Sex | R | 2.1 |

D Difference, PAF Population Attributable Fraction, PAR Population Attributable Risk, R Ratio

Discussion

Our study is the first nationally representative and the first to use the WHO HEAT equity toolkit to analyse sex disparities on the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs among males and females in Sierra Leone. We noted a steady decline in HIV/AIDS and STIs prevalence in Sierra Leone from 2000 to 2019. It was observed that there were sex-based disparities in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs throughout the two decades, with females consistently experiencing higher prevalence rates than males. The absolute difference in prevalence between males and females was consistently high across the 5-time point from 2000 to 2019. It important to note evidence has shown that addressing inequality may lead to reductions in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence [26].

The decline in the overall prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs observed in this study reflects the impact of intensified prevention and treatment efforts, including antiretroviral therapy scale-up, public health campaigns, and improved access to STI diagnostic and treatment services in Sierra Leone [21]. Like our study, studies conducted in Ghana [27] and four countries in central Africa [28], have also shown a downward trend of HIV/AIDS across all age groups and sexes. To maintain this downward trend over time, there should be concerted efforts on HIV/AIDS and STI prevention, detection, and treatment. Healthcare workers and policymakers should ensure that healthcare services are delivered using the primary healthcare approach, providing preventive, promotive, and curative services to every patient accessing care in healthcare facilities. Furthermore, there should be a national awareness raising campaign to ensure that people have access to accurate information with a key focus on preventive and promotive strategies. Additionally, there should be a comprehensive implementation of the national HIV test all, treat all strategy, which has been shown to reduce new HIV infection burden and enhance viral load suppression [29].

The higher prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STI among females is not only seen in Sierra Leone but also other parts of the world. In a study in South Africa, the HIV/AIDS prevalence was higher in females than in Males [30]. The high prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STI might be a result of biological factors, including the structure of the female reproductive organs [31]. However, other social factors might have been contributing greatly to this, including increased risk of sexual and gender-based violence, low decision-making (limited autonomy to take decision on their sexual right and activity), low level of education, and poverty [32]. Therefore, sex sensitive interventions should be developed and implemented using a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach. Several entry points can be used, including antennal care services, gynaecology clinics, adolescents and youth-friendly service centres, cervical cancer screening and treatment units, and one-stop centres that are handling SGBV issues. Furthermore, a wider screening, prevention, and treatment programme can be implemented to reduce the incidence and prevalence of STIs, prioritizing sexually active women and rural population. These include preventive approaches like routine and effective use of condoms, and vaccination initiatives, improvement in diagnostic capacities in hospitals, and effective case management of the common infection, including treatment of all sexual partners [33]. On the other hand, despite women showing higher HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence overtime as observed in our study. In the context of Sierra Leone, these findings could have been influence by factors like low testing rates among men, gender-based disparities disproportionately affecting women, among others. As a result, it is also crucial to implement targeted interventions to reduce the transmission of HIV in Sierra Leone. Some of these interventions include: developing targeted awareness campaigns that educate men about the importance of HIV testing, prevention, and treatment, and increase the availability of HIV and STI testing services in male-dominated spaces, such as workplaces, sports clubs, and community centers. Other interventions include: creating male-friendly health services that address the specific barriers men face in seeking care, including stigma and perceived lack of relevance, and promoting couples counseling and testing to encourage men to participate in health-seeking behavior alongside their partners. Furthermore, providing incentives for men to get tested and seek treatment, such as free health screenings, educational materials, or small rewards for participation in health programs will be vital in reducing HIV burden. Worth noting that, in the context of Sierra Leone other critical social determining factors like gender inequality, economic disparities, access to healthcare, cultural practices, social stigma and discrimination, violence, and community support systems disproportionately affect women thereby increasing their risk of contracting HIV/AIDS and STI. For instance, regarding gender inequality, women have less power in sexual relationships, making it difficult to negotiate safe sex practices. For economic disparities, women are more likely to experience low income and employment opportunities leading to economic dependency increasing their risk of contracting HIV/AIDS and STI. Also, persistent gender-based violence increases the risk of contracting HIV/AIDS and STI among women than men.

The findings of this study underscore the need for sex-sensitive public health strategies to address the persistent disparities in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence in Sierra Leone. Such interventions not only enhance women’s health but also contribute to the broader goal of achieving health equity and improving public health outcomes for the entire population. Efforts should focus on expanding access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services (SRHR), including STI screening, HIV testing, and treatment, particularly in rural and underserved areas where healthcare access is limited. Stakeholders should ensure adequate SRHR services needed for detecting and treating HIV/AIDS and STI infections are made readily available healthcare facilities, with special attention to rural areas. Healthcare workers providing SRHR services should be trained, and a regular refresher training be provided to them to enhance patient confidentiality. Stakeholders should establish a monitoring team to routinely supervise these service deliveries and ensure patients benefit from the comprehensive package without facing any barriers. Programs aimed at reducing gender-based violence and empowering women through education, economic opportunities, and community engagement are critical for addressing the root causes of gender disparities in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence. To enhance the successful implementation, stakeholders should establish or select an appropriate centre where women report this incident freely without facing any consequences. Awareness raising programs should be done to increase understanding on the location and benefit of reporting these incidents. The workers at this centre, should established a friendly interaction with medical practitioner who will be responsible for treating women in this centre who report incident of violence, mainly sexual violence. While females bear a disproportionate burden of HIV/AIDS and STIs, engaging men in prevention and treatment efforts is essential for reducing overall transmission rates. This includes promoting male HIV testing, condom use, and treatment adherence. Building a resilient health system capable of delivering equitable, high-quality care is essential for addressing the dual burden of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone. This includes investing in healthcare infrastructure, training healthcare providers, and integrating gender-sensitive approaches into national health policies.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis relied on secondary data from the WHO HEAT database, which might have been subjected to reporting biases and data quality issues inherent in national health surveys. This biasness, particularly information bias, could have likely aggravated by fear of respondents not been stigmatise by the population, despite the assurance provided by the data collectors. Second, while the study focused on sex-based disparities, other dimensions of inequality, such as socioeconomic status, geographic location, and urban-rural residence, were not explored due to data constraints. These factors may interact with sex to exacerbate health inequities and warrant further investigation. A qualitative study on gender dynamics is therefore recommended to provide a comprehensive and deeper perspective on the factors: socioeconomic status and geographic location influencing the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STI. Third, the study’s reliance on age-standardized prevalence rates limits its ability to capture the nuances of age-specific trends in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence, which may provide additional insights into high-risk populations. Also, it is important to note that the reliance on age-standardized rates may mask age-specific trends, especially in risk population, as certain age groups could have disproportionate burden that are obscured when aggregated, consequently affecting the precision of the study findings. Fourth, While HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence serves as a key indicator of the disease burden in a population, it is important to recognize its limitations. Prevalence estimates may not fully capture the complexities of the epidemic, as they do not account for several critical factors: temporal dynamics, underreporting and testing gaps, population mobility, socioeconomic factors, and viral treatment. Fifth, this study did not compute interventional analysis, thereby limiting causal inferences about trends. Future studies should incorporate data from program or policy timelines to better contextualize changes in the prevalence. Finally, the study did not assess the impact of specific interventions or policies implemented during the study period, which could provide valuable context for interpreting the observed trends.

Future directions

Future research should aim to address the limitations of this study by incorporating additional dimensions of inequality, such as socioeconomic status and geographic location, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of health disparities in Sierra Leone. Longitudinal studies examining the impact of specific interventions, such as ART scale-up and community-based prevention programs, on sex-based disparities in HIV/AIDS and STI prevalence are also recommended. Furthermore, qualitative research exploring the lived experiences of women and men affected by HIV/AIDS and STIs can provide valuable insights into the social and cultural factors driving these disparities.

Conclusion

This study revealed notable sex-based disparities in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Sierra Leone, despite an overall decline in prevalence over two decades. Females consistently experienced more than twice the burden of these infections compared to males, reflecting sex inequities in healthcare access, social determinants, and biological vulnerabilities. These findings underscore the need for sex-sensitive public health strategies and policies, and a multisectoral approaches with relevant stakeholders from the education, social welfare, health, and community to address these disparities and achieve health equity in Sierra Leone. By prioritizing the needs of women and addressing the structural barriers to care, Sierra Leone can make progress toward reducing the burden of HIV/AIDS and STIs and improving the health and well-being of its population.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to MEASURE DHS and the World Health Organization for making the dataset and the HEAT software accessible.

Abbreviations

- D

Difference

- HEAT

Health Equity Assessment Toolkit

- DHS

Demographic Health Survey

- PAF

Population Attributable Fraction

- PAR

Population Attributable Risk

- R

Ratio

- SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors' contributions

AO and US contributed to the study design and conceptualisation. AO, YST, US, and IFK developed the initial draft. AO, YST, US, and IFK critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. All authors read and amended drafts of the paper and approved the final version. US had the final responsibility of submitting it for publication.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Data availability

The dataset used can be accessed at https://www.who.int/data/inequality-monitor/assessment_toolkit.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not seek ethical clearance since the WHO HEAT software, and the dataset are freely available in the public domain.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global AIDS update 2023: the path that ends AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS. 2023. 296 p. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-aids-update-2023_en.pdf

- 2.Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, Low N, Unemo M, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(8):548–P562. 10.2471/BLT.18.228486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalsgaard S, Viuff JH, Sandøy IF, Jervelund SS, Laursen TM, Wejse C, et al. Gender disparities in HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(12):e820–30. 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30235-7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Sierra leone. Sierra leone.gender assessment report for the health sector 2022. Freetown: Government of Sierra Leone; 2022. p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Bank Group. Sierra Leone poverty assessment 2021: climbing the ladder to poverty reduction. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2021. p. AUS0003109. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Global health observatory data repository: Sierra Leone [Internet]. Geneva: WHO. 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/countries/country-details/GHO/sierra-leone

- 7.Statistics Sierra Leone, ICF. Sierra Leone demographic and health survey 2019. Freetown, Maryland: SSL and ICF; 2020. p. 520. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiba DF, Lakoh S, Wang S, Sun W, Barrie U, Kamara MN, Jalloh AT, Tamba FK, Yendewa GA, Song JW, Yang G. Sero-prevalence of syphilis infection among people living with HIV in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional nationwide hospital-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osborne A, Essuman MA, Wongnaah FG, Aboagye RG, Bangura C, Ahinkorah BO. Provincial distribution and factors associated with self-reported sexually transmitted infections and their symptoms among women in Sierra Leone. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):1265. 10.1186/s12879-024-09266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations Development Programme. Socioeconomic impact of HIV/AIDS in Sierra Leone. Freetown: UNDP Sierra Leone; 2021. p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Elendu ID, Elendu TC, Amaechi EC, Usoro EU, Chima-Ogbuiyi NL, Agbor DB, Onwuegbule CJ, Afolayan EF, Balogun BB. Global perspectives on the burden of sexually transmitted diseases: a narrative review. Medicine. 2024;103(20):e38199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Worafi YM. Epidemiology and burden of infectious diseases in developing countries: HIV and stis. InHandbook of medical and health sciences in developing countries: education, practice, and research 2023 Dec 15 (pp. 1–22). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- 13.Levy ME, Wilton L, Phillips G, Glick SN, Kuo I, Brewer RA, Elliott A, Watson C, Magnus M. Understanding structural barriers to accessing HIV testing and prevention services among black men who have sex with men (BMSM) in the united States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:972–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Li X, Brecht ML, Koniak-Griffin D. Can self-testing increase HIV testing among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casey SE, Larsen MM, McGinn T, Sartie M, Dauda M, Lahai P. Changes in HIV/AIDS/STI knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours among the youth in Port Loko, Sierra Leone. Glob Public Health. 2006;1(3):249–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly JD, Reid MJ, Lahiff M, Tsai AC, Weiser SD. Community-level HIV stigma as a driver for HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases in Sierra Leone: a population-based study. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(4):399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen MM, Casey SE, Sartie MT, Tommy J, Musa T, Saldinger M. Changes in HIV/AIDS/STI knowledge, attitudes and practices among commercial sex workers and military forces in Port Loko, Sierra Leone. Disasters. 2004;28(3):239–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osborne A, Bangura C, Williams SM, Koroma AH, Fornah L, Yillah RM, Ahinkorah BO. Spatial distribution and factors associated with HIV testing among adolescent girls and young women in Sierra Leone. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1): 1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fornah L, Shimbre MS, Osborne A, Tommy A, Ayalew AF, Ma W. Geographic variations and determinants of ever-tested for HIV among women aged 15–49 in Sierra Leone: a spatial and multi-level analysis. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Audrey Djibo D, Sahr F, Allen McCutchan J, Jain S, Rosario G, Araneta M, K Brodine S, Shaffer A. Prevalence and risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis infections among military personnel in Sierra Leone. Curr HIV Res. 2017;15(2):128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Sierra leone. National HIV and AIDS strategic plan 2021–2025. Freetown: Government of Sierra Leone; 2023. p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Government of Sierra Leone. Voluntary National review report on the implementation of the sustainable development goals. Freetown: Office of the President; 2023. p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlotheuber A, Hosseinpoor AR. Summary measures of health inequality: a review of existing measures and their application. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6): 3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Handbook on health inequality monitoring: with a special focus on low-and middle-income countries. World Health Organization; 2013.

- 25.Hosseinpoor AR, Nambiar D, Schlotheuber A, Reidpath D, Ross Z. Health equity assessment toolkit (HEAT): software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:1–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiv TL. Addressing inequalities still key to ending HIV/AIDS. The lancet. HIV. 2023;10(1):e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boah M, Yeboah D, Kpordoxah MR, Issah AN, Adokiya MN. Temporal trend analysis of the HIV/AIDS burden before and after the implementation of antiretroviral therapy at the population level from 1990 to 2020 in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martial NT, Mubarik S, Yu C. The trend of HIV/AIDS incidence and risks associated with age, period, and birth cohort in four central African countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5): 2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Endalamaw A, Gilks CF, Assefa Y. To what extent is equity entrenched in HIV/AIDS-related policy documents in Ethiopia?? A policy content analysis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2025;23:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kharsany AB, McKinnon LR, Lewis L, Cawood C, Khanyile D, Maseko DV, Goodman TC, Beckett S, Govender K, George G, Ayalew KA. Population prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in a high HIV burden district in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: implications for HIV epidemic control. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:130–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Gerwen OT, Muzny CA, Marrazzo JM. Sexually transmitted infections and female reproductive health. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7(8):1116–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muluneh MD, Francis L, Agho K, Stulz V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of associated factors of gender-based violence against women in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9): 4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV, viral hepatitis and STI prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. World Health Organization; 2022 Jul. p. 29. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used can be accessed at https://www.who.int/data/inequality-monitor/assessment_toolkit.