Abstract

Helicobacter species colonize the gastrointestinal tract of various hosts, and are of interest due to their potential zoonotic transmission and impact on health of humans and animals. Comprehensive studies involving wild animals from different locations are lacking, hindering our understanding of their host range, prevalence, and genetic diversity. We investigated the prevalence and genetic diversity of Helicobacter species in thirteen wild carnivore species across twenty-two captive locations in India by targeting a partial region of the 16S rRNA gene. We used sequences obtained from positive samples for phylogenetic analysis, and evaluated factors influencing Helicobacter prevalence. We analysed faecal samples of 985 individuals of which 286 (29%) tested positive for Helicobacter, spanning all the host species included in this study. Helicobacter prevalence is strongly related to host species and location, and varied from 7.3% in common leopard to 80% in Indian fox. Phylogenetic analysis identified 59 unique genotypes clustered into 11 groups of three major Helicobacter types: enterohepatic, gastric, and unsheathed. Diverse Helicobacter species associated with diseases in humans and domestic animals were observed, such as H. canis, H. bilis, along with several novel genotypes which require formal classification. Overall, this study highlights the wide occurrence and high genetic diversity of Helicobacter species in captive wild carnivores in India. Our findings underscore the need for regular health assessments in captive facilities to monitor Helicobacter infections, which could impact health and management of endangered species. Future research should explore Helicobacter presence in biotic/ abiotic factors in zoo and free-ranging populations following One Health approaches.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12917-025-04886-7.

Keywords: Helicobacter, Zoonotic disease, Reverse zoonoses, Wild carnivores, 16S rDNA, Phylogenetics, India

Introduction

The world, as we know it, is changing and reshaping at an unprecedented scale and speed, bringing the last surviving wildlife populations in close proximity to humans and domestic animals. Following the recent COVID-19 pandemic, there is widespread concern about zoonotic disease risk and transmission of new/ more virulent pathogens from animals - both wild and domestic - to humans. What is even more worrying, and is slowly being accepted as a ticking bomb, is the exposure of endangered wild animals to pathogens from humans and livestock (reverse zoonosis) with serious consequences to their survival as well as public health [19]. Deforestation, land use conversion, climate change, illegal wildlife hunting and trade, booming pet markets, international trade and travel routes, are all rapidly driving the transmission of pathogens from animals to humans and vice versa [30].

By definition, zoonotic pathogens can infect multiple hosts, and organisms which can infect several taxonomic orders of animals, especially wild species, can potentially emerge as new threats [9]. The Helicobacter genus is one such group of organisms which can infect a wild range of host species. Over the past three decades, this genus of Gram-negative bacteria has expanded to include nearly fifty species, many of which can persistently colonize the gastrointestinal tract of various hosts [41]. Waite et al. [58] found that this genus is highly divergent and may soon be reclassified into several genera. Among its members, the gastric Helicobacter species are better studied, primarily due to the important and well-known species H. pylori, which infects a large proportion of the human population worldwide. H. pylori was identified as a major cause of chronic gastritis and its presence significantly increases the risk of developing peptic ulcers and gastric cancer in humans. There is now a growing interest in other gastric and enterohepatic Helicobacter species due to their association with several gastrointestinal and systemic diseases, cancers, etc. (reviewed in Ochoa and Collado [41]). Although many Helicobacter species are part of the resident gut microflora in normal or asymptomatic hosts, there is also compelling evidence that their presence is associated with various diseases and neoplasia during times of compromised immunity in both humans and animals [7, 20, 21, 24, 25, 35, 38, 46, 61, 42].

Helicobacter taxa are recognized as emerging potential pathogens owing to their wide presence and increasing zoonotic potential; however, their natural host range, epidemiological significance, and transmission remain obscure [22, 39]. While high prevalence and diversity of Helicobacter species in domestic and companion animals have been reported worldwide [40], studies on the prevalence of Helicobacter species in wild animals, both free-ranging and captive, are few and sporadic [8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 49, 55–57]. Furthermore, whereas population-based studies of a single Helicobacter species in humans have been used to assess intraspecific genetic variation [31]; very little is known about the level of genetic variation of Helicobacter species from wild animal populations. Hence, screening wild animals for the occurrence and prevalence of different Helicobacter species is crucial for gaining insights into their genetic diversity, host range, and eco-epidemiology.

Globally, ex-situ management and captive breeding of endangered animals are important components of species conservation, aimed at stabilizing and re-establishing dwindling populations in the wild [2, 45, 53]. However, drastic environmental changes when animals are brought into captivity can cause radical shifts in their microbiota, creating suitable conditions for the propagation of pathogenic microorganisms [32, 60]. This not only affects the survival of captive populations and endangers species management and reintroduction programs but also poses significant health threats, as the zoo environment is highly conducive to the exchange of pathogens. Helicobacter species have been associated with diseases in captive populations in a few reports, often with negative health outcomes [17]. For example, acute gastritis associated with Helicobacter species is a major cause of cheetah morbidity and mortality worldwide [56]. However, comprehensive studies investigating the incidence and diversity of Helicobacter species across a wide range of wild host species in various captive facilities are lacking.

In this study, we examine the prevalence and diversity of Helicobacter species in several wild carnivore mammals in zoos and rescue centers across India. India represents an enigma, with a high Helicobacter prevalence (80%) in human populations varying according to geographical locations [37]. Thus, it is essential to assess wild captive populations from different regions of India from a Helicobacter perspective. We further discuss the implications of our findings for more efficient management of wild animals in captivity.

Methodology

Study area and target species

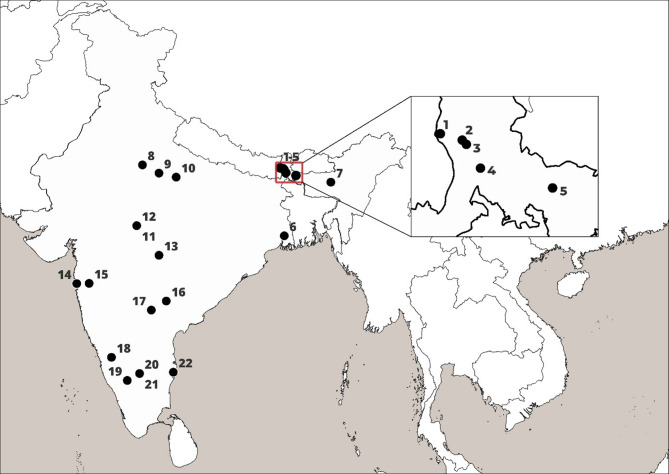

We collected samples from twenty-two zoos and rescue centers across eight states in India (Fig. 1; Table 1) from thirteen carnivore species - Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), lion (Panthera leo), common leopard (Panthera pardus fusca), snow leopard (Panthera uncia), wild dog/ dhole (Cuon alpinus), grey wolf (Canis lupus), Himalayan wolf (Canis himalayansis), golden jackal (Canis aureus), Indian fox (Vulpes bengalensis), striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), Himalayan black bear (Ursus thibetanus), and red panda (Ailurus fulgens) between November 2021 to January 2023.

Fig. 1.

Locations of zoos and rescue centers in India where captive carnivore samples were collected and examined for Helicobacter species. 1 – Red panda soft release center, Singhalila National Park (SRC-SNP); 2 – Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park, Darjeeling (P NHZP); 3 – Conservation Breeding Center, Tobkedara (NCBC); 4 – North Bengal Wild Animal Park, Siliguri (NBWAP); 5 – Khairbari Tiger Rescue Center, Madarihat (KTRC); 6 – Zoological Garden Alipore, Kolkata (ZGA); 7 – Assam State Zoo, Guwahati (ASZ); 8 – Wildlife SOS, Agra (WSOS-A); 9 – Etawah Lion Safari Park (ELSP); 10 – Kanpur Zoological Park (KNZP); 11– Van Vihar National Park, Bhopal (VVNP); 12 – Wildlife SOS, Bhopal (WSOS-BH); 13 – Gorewada Rescue Center, Nagpur (GRC); 14 – Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Mumbai (SGNP); 15 – Wildlife SOS, Junnar (WSOS-J); 16 – Kakatiya Zoological Park, Warangal (KAZP); 17 – Nehru Zoological Park, Hyderabad (NZP); 18 – Tiger and Lion Safari, Thevarakoppa (TLST); 19 – Sri Chamarajendra Zoological Garden, Mysuru (SCZG); 20 – Bannerghatta National Park (BNP); 21 – Wildlife SOS, Bannerghatta National Park (WSOS-BNP); 22 – Arignar Anna Zoological Park, Chennai (AAZP)

Table 1.

Helicobacter prevalence as seen in different host species across various zoos and rescue centers in India

| S. No | Host sp Location |

Lion (L) | Bengal tiger (YT, WT) | Common leopard (LP) | Snow leopard (SLP) | Sloth bear (B_MU) | H. bear (B_UT) | Red panda (RP) | Striped hyena (H) | Golden jackal (GJ) | Wild dog (WD) | Grey wolf (GW) | H. wolf (HW) | Indian fox (F) | Total | Location wise positive % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SRC-SNP | - | - | - | - | - | - |

9(9) 100% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | 9(9) | 100 |

| 2 | PNHZP | - |

1(0) 0% |

3(0) 0% |

2(1) 50% |

- |

3(2) 66.6% |

18(10) 55.5% |

- | - | - | - |

6(1) 16.7% |

- | 33(14) | 42.4 |

| 3 | NCBC | - | - | - |

9(5) 55.5% |

- | - |

9(7) 77.8% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | 18(12) | 66.7 |

| 4 | NBWAP | - |

5(1) 20% |

4(0) 0% |

- | - |

4(3) 75% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13(4) | 30.8 |

| 5 | KTRC | - |

1(0) 0% |

21(0) 0% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22(0) | 0.0 |

| 6 | ZGA | 4(1) 25% |

6(1) 16.6% |

1(0) 0%] |

- |

1(0) 0% |

2(2) 100% |

- |

2(2) 100% |

6(6) 100% |

4(3) 75% |

- | - | - | 26(15) | 57.7 |

| 7 | ASZ |

5(0) 0% |

6(0) 0% |

23(0) 0% |

- | - |

9(0) 0% |

- |

2(0) 0% |

6(0) 0% |

- | - | - | - | 51(0) | 0.0 |

| 8 | WSOS-A | - | - | - | - |

106(23) 21.7% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 106(23) | 21.7 |

| 9 | ELSP |

16(5) 31.2% |

1(0) 0% |

9(3) 33.3% |

- |

3(1) 33.3% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 29(9) | 31.0 |

| 10 | KNZP |

5(1) 20% |

8(2) 25% |

19(4) 21% |

- |

2(2) 100% |

4(3) 75% |

- |

6(5) 83.3% |

8(7) 87.5% |

- |

2(1) 50% |

- |

3(3) 100% |

57(28) | 49.1 |

| 11 | VVNP |

3(0) 0% |

11(0) 0% |

7(0) 0% |

- |

4(0) 0% |

- | - |

1(0) 0% |

1(1) 100% |

- | - | - | - | 27(1) | 3.7 |

| 12 | WSOS-BH | - | - | - | - |

16(2) 12.5% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16(2) | 12.5 |

| 13 | GRC | - |

10(8) 80% |

20(3) 15% |

- |

2(2) 100% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32(13) | 40.6 |

| 14 | SGNP | - |

5(0) 0% |

14(0) 0% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 19(0) | 0.0 |

| 15 | WSOS-J | - | - |

25(1) 4% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25(1) | 4.0 |

| 16 | KAZP | - | - |

2(0) 0% |

- |

3(1) 33.3% |

- | - | - |

4(4) 100% |

- | - | - | - | 9(5) | 55.6 |

| 17 | NZP |

9(5) 55.5% |

19(13) 68.4% |

13(4) 30.8% |

- |

10(6) 60% |

6(6) 100% |

- |

4(0) 0% |

16(4) 25% |

11(6) 54.5% |

4(2) 50% |

- |

2(1) 50% |

94(47) | 50.0 |

| 18 | TLST |

4(0) 0% |

5(0) 0% |

14(1) 7.14% |

- |

4(2) 50% |

- | - |

2(0) 0% |

5(2) 40% |

- | - | - | - | 34(5) | 14.7 |

| 19 | SCZG |

5(0) 0% |

17(0) 0% |

18(1) 5.5% |

- |

11(8) 72.7% |

6(5) 83.3% |

- |

16(9) 56.2% |

6(6) 100% |

30(12) 40% |

14(5) 35.71% |

- |

3(3) 100% |

126(49) | 38.9 |

| 20 | BBP |

15(0) 0% |

10(0) 0% |

45(1) 2.2% |

- |

3(2) 66.6% |

5(4) 80% |

- |

2(1) 50% |

8(4) 50% |

3(0) 0% |

7(3) 42.9% |

- | - | 98(15) | 15.3 |

| 21 | WSOS-BNP | - |

1(0) 0% |

3(0) 0% |

- |

65(28) 43.1% |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 69(28) | 40.6 |

| 22 | AAZP |

9(0) 0% |

27(4) 14.8% |

5(0) 0% |

- |

1(1) 100% |

1(0) 0% |

- |

5(0) 0% |

1(0) 0% |

6(0) 0% |

15(0) 0% |

2(1) 50% |

72(6) | 8.3 | |

| Total | 75(12) | 133(29) | 246(18) | 11(6) | 231(78) | 40(25) | 36(26) | 40(17) | 61(34) | 54(21) | 42 (11) | 6(1) | 10(8) | 985 (286) | 29.0 | |

| Host species positive % | 16.0 | 21.8 | 7.3 | 54.5 | 33.8 | 62.5 | 72.2 | 42.5 | 55.7 | 38.9 | 26.2 | 16.7 | 80.0 | 29.0 | - |

1 – Red Panda Soft Release Center, Singhalila National Park (SRC-SNP); 2 – Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park, Darjeeling (PNHZP); 3 – Conservation Breeding Center, Tobkedara (NCBC); 4 – North Bengal Wild Animal Park, Siliguri (NBWAP); 5 – Khairbari Tiger Rescue Center, Madarihat (KTRC); 6 – Zoological Garden Alipore, Kolkata (ZGA); 7 – Assam State Zoo, Guwahati (ASZ); 8 – Wildlife SOS, Agra (WSOS-A); 9 – Etawah Lion Safari Park (ELSP); 10 – Kanpur Zoological Park (KNZP); 11 – Van Vihar National Park, Bhopal (VVNP); 12 – Wildlife SOS, Bhopal (WSOS-BH); 13 – Gorewada Rescue Center, Nagpur (GRC); 14 – Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Mumbai (SGNP); 15– Wildlife SOS, Junnar (WSOS-J); 16 – Kakatiya Zoological Park, Warangal (KAZP); 17 – Nehru Zoological Park, Hyderabad (NZP); 18 – Tiger and Lion Safari, Thevarakoppa (TLST); 19 – Sri Chamarajendra Zoological garden, Mysuru (SCZG); 20 – Bannerghatta Biological Park (BBP); 21 – Wildlife SOS, Bannerghatta National Park (WSOS-BNP); 22 – Arignar Anna Zoological Park, Chennai

Sample collection and DNA analysis

Fresh faecal samples (one per individual) were collected with a clean and sterilised spatula, within minutes of defecation, after moving the concerned animal to another enclosure with the help of animal keepers. We took several precautions while collecting samples like wearing mask and gloves, avoiding sample’s contact with soil, transferring sample immediately into a sterile tube which was then sealed properly. Each sample collection tube was labelled with details such as Name/ ID of the animal, gender, location and date of sample collection. Faecal sample tubes were immediately transferred to a -10°C Zedblox Actipod™ to arrest microbial growth and to minimise contamination. DNA was isolated from the faecal samples with Nucleospin DNA stool Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) as per manufacturer’s instructions. We avoided possible contamination by aliquoting samples and isolating DNA in separate biosafety cabinets. DNA quality and quantity were measured with a UV-Nano-drop spectrophotometer. Samples with 20ng/µl of DNA were used directly while those with higher DNA concentrations were diluted to 20ng/µl prior to PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction). Helicobacter genus-specific primers, C97F (5’-GCTATGACGGGTATCC-3’) and C98R (5’-GATTTTACCCCTACACCA-3’), targeting ~ 398 bp segment of 16S rRNA gene [51] were used to detect the presence of Helicobacter taxa in the faecal samples. A 20 µl PCR reaction mixture consisted of 20ng/ul template DNA, 250µM dNTP, 1xTaq buffer (TaKaRa, Japan), 1x BSA, 1U Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Ex Taq Hot Start Version, TaKaRa, Japan), and 5µM of each primer. PCR was set in Veriti™ 96-well Fast Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA), with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 51°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 30 s and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Following PCR, the PCR products were visualized in a 2% agarose gel, and purified for Sanger sequencing. To test for contamination, negative controls were included at both the DNA extraction (no sample added) and PCR amplification (with PCR-certified water) steps.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

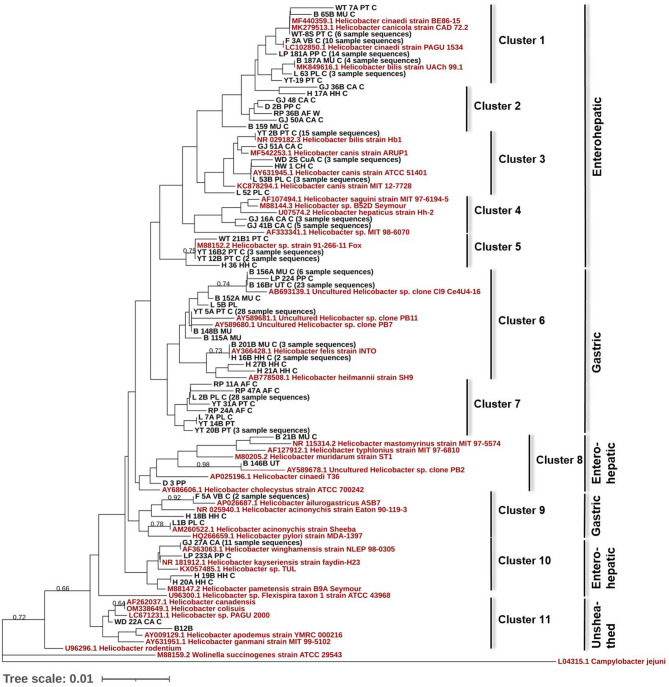

PCR amplicons were sequenced in ABI 3730 DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems, USA). Sequences were trimmed and assembled using CodonCode Aligner (CodonCode Corporation, USA) to generate consensus sequences. We searched for sequence similarities using NCBI-BLASTN [6, 33], and the cut-off for both percentage identity and query coverage was ≥ 98%. We identified the number of unique sequences using DnaSP program [47] and major genotypes based on number of occurrence (≥ 10). ClustalW multiple sequence alignment was performed in BioEdit [23]. A neighbour-joining (NJ) tree [48] was constructed in MEGA7 software [29] using K2-P distances among sequences (all trimmed to a length of 323 bp) with 1000 bootstraps [15] combining (i) 59 unambiguous sequences from samples in this study (i.e. excluding heterozygous sequences indicating multiple infections with more than one strain or species), (ii) 15 sequences of Helicobacter species known to occur in diverse mammalian species, Type strain: H. pylori strain MDA-1397 (HQ266659.1), H. canadensis (AF262037.1), H. canis strain ATCC 51401 (AY631945.1), H. cholecystus strain ATCC 700242 (AY686606.1), H. sp. Flexispira taxon 1 strain ATCC 43968 (U96300.1), H. ganmani strain MIT 99-5102 (AY631951.1), H. hepaticus strain Hh-2 (U07574.2), H. sp. MIT 98-6070 (AF333341.1), H. muridarum strain ST1 (M80205.2), H. pametensis strain B9A Seymour (M88147.2), H. rodentium (U96296.1), H. saguini strain MIT 97-6194-5 (AF107494.1), H. sp. B52D Seymour (M88144.3), H. typhlonius strain MIT 97-6810 (AF127912.1), H. acinonychis strain Eaton 90-119-3 (NR_025940.1)) [12] and (iii) 24 sequences showing high similarity (≥ 98% identity in BLAST searches) with the sequences obtained in this study, including four publicly available uncultured Helicobacter sequences retrieved from NCBI GenBank, mainly to signify the host origin of these isolates. Wolinella succinogenes (M88159) and Campylobacter jejuni (L04315) were used as outgroups as done previously [12, 59].

Statistical analysis

In order to determine if host species and sampling locations can explain Helicobacter infection among individuals, we performed generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) in R environment (R version-4.3.1, [44]). We modelled Helicobacter infection according to host species (n = 13) and sampling location (n = 22) as fixed effect, and sample ID to control the random effect using lme4 package [4]. To model Helicobacter occurrence, binomial family distribution with logit function (link = “logit”) was used. Model selection was based on information-theoretic (IT) approach with second-order Akaike’s information criterion corrected for small sample sizes (AICc) and Akaike weights (ω) to determine model support [5]. We report both conditional and marginal coefficients of determination of model (R2GLMM(c), which explains variance of both fixed and random factors, and R2GLMM(m), which explains variance of fixed factors only), which we calculated as the variance explained by the best model and ΔAICc.

Results

We collected faecal samples of 985 individuals belonging to thirteen endangered carnivore species in twenty-two zoos and rescue centers across India. Following PCR and sequence analysis, 286 samples were found to be positive for Helicobacter, giving an overall prevalence of 29%. Two species-specific markers targeting H. bilis and H. felis [3, 16] were used to further cross-check and verify the sequences generated with Helicobacter genus-specific markers. All the studied host species were found to be Helicobacter positive; however, Helicobacter prevalence varied in different species, the lowest being in common leopard (7.3%) and the highest in Indian fox (80%) as shown in Table 1. Location-wise prevalence ranged from 0% in Khairbari Tiger Rescue Center, Assam State Zoo and Sanjay Gandhi National Park; to 100% in Red Panda Soft Release Center, Singhalila National Park (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis revealed three major types of Helicobacter based on their preferred place of colonization, and anatomy of the flagella; enterohepatic, gastric and unsheathed (Fig. 2). A large proportion (nearly 50%) of the positive samples matched with unclassified Helicobacter spp., especially in ursids (sloth bear and Himalayan black bear) and red panda. In case of the canids (golden jackal, dhole, Himalayan wolf and Indian fox) and striped hyena, the most frequently matched species were H. canis, H. felis, H. cinaedii and H. winghamensis (Fig. 2; Supplementary Material S1).

Fig. 2.

Distribution and evolutionary relationships of Helicobacter strains/species in captive carnivore species: Neighbour-joining tree based on comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequences, obtained from this study (59 unique genotypes-in black, initials letters in the sample name represent an unique sample code indicating genus and species (e.g. MU- Melursus ursinus), last letter represents captive (C) or recently caught from wild (W)), 15 sequences of reference Helicobacter strain/species known to occur in diverse mammalian species (in red, see Methodology section for details), and 24 sequences showing high similarity (≥ 98%) in BLAST searches with the sequences obtained within this study (in red). GenBank accession numbers are shown along with strain/species name. Numbers above branches are bootstrap values (only those above 60 are shown). The sequences are clustered and grouped further based on their preferred place of colonization or if they are unsheathed

We obtained 211 clear sequences from 286 Helicobacter positive samples, whereas clean chromatograms could not be obtained from 75 samples due to mixed Helicobacter signatures. We found 59 unique genotypes (Supplementary Material S1) in which 7 major genotypes represented 129 of 211 sequences (Genbank accession numbers PP961961 – PP962171). The neighbour-joining tree, with 59 genotypes along with 15 reference Helicobacter sequences and 24 Helicobacter sequences showing close match with sample sequences, showed 11 distinct sequence clusters (Fig. 2) falling into 3 major Helicobacter types (i.e. enterohepatic, gastric, unsheathed). The clusters were identified based on tree topology and sequence similarity. Some branches however were weakly supported, as is often observed in phylogenetic tree construction [52]. Clusters 1–5, 8 and 10 were enterohepatic, whereas clusters 6–7 and 9 were gastric, and cluster 11 was unsheathed Helicobacter species. Cluster 6 was the largest cluster representing 69 samples followed by cluster 1 (40 samples), cluster 7 (37 samples), cluster 3 (24 samples), etc. On closer look, cluster 6 was divided into two sub-clusters, one represented by H. felis and H. heilmannii, and the second largely represented by uncultured Helicobacter, all previously isolated from polar bear. Further, cluster 6 mainly consisted of samples from sloth bear (65.22%) and Himalayan black bear (15.94%). Reference Helicobacter sequences or sequences with high similarities with our study samples were distributed in all the clusters except cluster 2 and cluster 7, which were found to be unique with no close representatives in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). Cluster 2 consisted of seven unique sequences, three of them originating from golden jackal, and one each from common leopard, sloth bear, hyena and red panda. Although three distinct sub-groups can be observed within Cluster 2, due to the absence of closely related reference sequences, we grouped them together under a single cluster. Cluster 7 consisted of eight unique sequences - three of them originating from red panda, another sequence present in 28 individuals mostly red panda (57%), three sequences from tiger, and one from Asiatic lion. H. rodentium (U96296.1) and Helicobacter sp. Flexispira taxon 1 (U96300.1) sequences taken from NCBI as reference sequences, did not fall in any of the clusters.

Generalized linear mixed model showed a strong support for effects of host species and locations in explaining Helicobacter prevalence (ΔAICc = 159.30), by controlling the random effect of sample identity. The conditional coefficient (R2GLMM(c)) of determination was 0·601, while marginal coefficient (R2GLMM(m)) of determination was 0·484. The random effect of sample identity contributed to ~ 10% of the variation in Helicobacter prevalence. Highest Helicobacter prevalence was observed in Indian fox (80%) followed by red panda (72.2%), Himalayan black bear (62.5%), golden jackal (55.7%) and snow leopard (54.5%), while the lowest prevalence was noted in common leopard (7.3%) (Table 1). In terms of location, the maximum number of Helicobacter positive samples were from Red Panda Soft Release Centre, Singhalila National Park (100%) followed by Conservation Breeding Center, Tobkedara (66.7%), Kakatiya Zoological Park, Warangal (55.6%) and Nehru Zoological Park, Hyderabad (50.0%), whereas samples from several other locations were found to be Helicobacter negative (Table 1).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the most comprehensive screening of diverse wild carnivores housed in various captive facilities across a large and biodiverse region for the presence of Helicobacter species. Results of this study indicate that Helicobacter is present in all the thirteen wild animal species screened, with an overall prevalence of 29%. However, the prevalence varies among different host species and across various locations. We report Helicobacter presence for first time in some of the host species such as snow leopard, sloth bear, Himalayan black bear, striped hyena, dhole or Indian wild dog, Himalayan wolf and Indian fox. Among the canids, Indian fox and golden jackal show a high prevalence of Helicobacter species (Table 1) earlier detected and reported in humans, domestic dogs and cats [27, 28, 36]. Both these host species are commonly present around human settlements. However, mere presence of Helicobacter species may not indicate infections and/ or transmissions, especially when these organisms are known to be part of the normal gut flora. Further, small sample size in some of the host species could bias the overall occurrence comparison. Nevertheless, the high prevalence reported here definitely warrants further investigations. Comparatively lower prevalence of Helicobacter was observed in lion, tiger and leopard in comparison to other host species, and with reference to an earlier study [26]. However, the diversity of species/ strains was high, for example 14 different genotypes were observed in tiger samples, which could be due to high number of samples tested from various locations, compared to other host species.

We observed 59 Helicobacter strains/ species in 13 studied captive carnivores, which suggests wide presence and unexplored genetic diversity of Helicobacter in wild animals in India. Few Helicobacter strains/ species (i.e. 7 unique genotypes) dominate and are present in more than half of the samples sequenced. The detected genotypes showed close sequence similarity with various reference Helicobacter species included in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). Overall, noted clusters comprised of three Helicobacter types based on either their preferred place of colonization (i.e. enterohepatic, gastric) in the gastrointestinal tract, or Helicobacter without sheathed flagella (i.e. unsheathed) as observed in earlier studies [1, 12]. In India high occurrence and genetic diversity of H. pylori were observed in human populations [18]. Interestingly, only 15–20% of H. pylori infected populations in India develop gastric or duodenal ulcers. Although, we did not detect H. pylori in our studied samples, high diversity in strains or species could be a cause for concern of the health of captive populations, especially in the case of Helicobacter species which are associated with diseases in animals [8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 49, 55–57]. For example, we detected H. acinonychis in one lion sample (Fig. 2), a species earlier associated with cheetah deaths in captivity and also with diseases in other carnivores [13, 49, 56]. H. acinonychis has earlier been isolated and characterised from various big cats in different parts of the world [11, 14, 49, 55], and is found to be closely associated with H. pylori [55]. Eppinger et al. [14] presented compelling genomic evidence of reverse zoonosis and suggested that H. pylori jumped from humans to a wild feline host nearly 200 kya (range 100–400 kya), adapted to its new host, speciated as H. acinonychis and then spread globally in several feline species like cheetah, tiger and lion. Like H. pylori in humans, H. acinonychis is associated with chronic gastric pathology in wild felids [8, 34, 49, 55].

It should be noted that around 25% of Helicobacter positive samples could not be included in our phylogenetic tree due to mixed Helicobacter signatures. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility of presence of other strains/ species of Helicobacter undermining the overall diversity. The significant effect of sample location on Helicobacter prevalence could be largely because samples from different species were collected from different locations. Therefore, in order to tease apart the role of location in shaping Helicobacter prevalence, samples from one host species should be collected from different locations. Future research should also account for the effect of other host variables like age, health status, etc. This is often difficult to achieve, as both the number of animal species and individual counts vary across facilities. Nevertheless, we accounted for all available mega- and meso-carnivores from each facility to assess the full breadth of Helicobacter presence and its genetic diversity in captive carnivore population in India.

A large proportion of red panda, sloth bear and Himalayan black bear samples showed the presence of Helicobacter species which did not match with any of the known or classified Helicobacter species or strains (i.e. cluster 6, 7 in Fig. 2). We obtained similar results in free-ranging red panda samples collected in Neora Valley National Park, West Bengal. This suggests possible presence of novel Helicobacter strains or species in these host species, and requires further research and formal classification. An earlier study by Sommer et al. [54] showed that Helicobacter abundance increases in brown bears in summer months in response to diet change after the hibernation period. Interestingly, it has also been observed that cases of H. pylori-associated gastritis increase with altitude in human subjects [43, 50], Thus, whether the observed Helicobacter species or strains in red panda and Himalayan black bear are opportunistic pathogens or important gut flora associated with cold adaptation or any other vital function in these high-altitude animals remains to be tested. These results also explain why two locations, Red Panda Soft Release Center, Singhalila National Park and Conservation Breeding Center, Tobkedara have the maximum numbers of Helicobacter positive samples as these largely or exclusively house red panda. Interestingly, both these locations are fairly isolated, have minimal human footfall, and are dedicated for the conservation of endangered Himalayan species like red panda and snow leopard. Similarly, cluster 2 in our phylogenetic tree has seven genotypes without any close reference Helicobacter species, suggesting novel genotypes not recorded earlier. Three of these genotypes are exclusively from golden jackal. All our findings warrant further research in this direction in order to formally classify these genotypes and to ascertain their association with animal health.

Conclusions

We documented the broad occurrence and high genetic diversity of Helicobacter species in wild captive carnivores in India with prevalence varying according to host species. Diverse Helicobacter species known to be associated with diseases in humans and domestic animals were observed, and also several novel strains/ species were detected which require further research and formal classification. Our results indicate that Helicobacter species could be common residential bacteria in some of the host species, but given their ability to cause severe debilitating diseases in multiple hosts, these species should be studied further for their impact on health of wild animals. The zoonotic potential and mode of transmission of these Helicobacter species through contaminated food, water or vectors like rats, need to be examined in detail. Future research should examine zoo personnel like animal keepers in order to explore the zoonotic potential of Helicobacter species, as well as free ranging wild populations in order to disentangle the role of captive facilities in Helicobacter infection following the One-Health framework. We recommend inclusion of potential pathogens such as Helicobacter species in regular health assessment in zoos and rescue centers for better health management of animals and their keepers and to record pathogen transmission events, if any.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the Chief Wildlife Wardens of the states of Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Assam, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka for permitting us to collect samples of animals in captivity. We are grateful to the support extended by staff of zoos and rescue centers.

Author contributions

W.U. – conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, software, visualization, writing original draft; G.K. – sample collection, methodology, investigation, formal analysis; S.N. – sample collection, methodology, data curation, validation; N.S. – sample collection, methodology; B.S.H. – resources, data curation; Md. A.H. – resources, data curation; A.B.S. – fund acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision; and P. A.R. – fund acquisition, project administration, supervision, resources, visualization, writing original draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of a project entitled “SBI Foundation Centre of Excellence for Genome-guided Pandemic Prevention” (GAP570) funded by SBI Foundation, India.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information with Genbank accession numbers PP961961 – PP962171.

Declarations

Animal ethics approval and consent to participate

Permissions to collect samples for this study were granted by Chief Wildlife Wardens of West Bengal (No.1703/WL/4R-31/2021, dated 01/09/2021), Maharashtra (No: Desk-22(8)/WL/Research/CR-37(21–22)/1344/21–21, Nagpur, dated 07/09/2021), Telangana (No.26803/2012/WL-2, dated 14/09/2021), Assam (No. WL/FG/31/Research.T.C./28th T.C.2021, dated 20/12/2021), Tamil Nadu (No.4822/2021/WL1, dated 28/01/2022), Madhya Pradesh (No./M.H.-II/ Research/2824, Bhopal, dated 13/04/2022), Karnataka (No.PCCF(WL)/E2/CR-37/2021-22, dated 17/05/2022), and Uttar Pradesh (No. 23-2-12(G), Lucknow, dated 20/05/2022).

Consent for publication

All authors in our study (Wasim Uddin, Gulafsha Khan, Sneha Narayan, Neha Sharma, Basavaraj S. Holeyachi, Md. Abdul Hakeem, Archana Bharadwaj Siva and P. Anuradha Reddy) agree to the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ashaolu JA, Tsai Y, Liu C, Ji D. Prevalence, diversity and public health implications of Helicobacter species in pet and stray dogs. One Health. 2022;15:2352–7714. 10.1016/j.onehlt.2022.100430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Ballou JD, Lees C, Faust LJ, Long S, Lynch C, Lackey LB, Foose TJ. (2010) Demographic and genetic management of captive populations. In Press: Devra G. Kleiman, Kaci Thompson, and Charlotte Kirk-Baer, editor. Wild Mammals in Captivity. Univ. of Chicago Press.

- 3.Baele M, Van den Bulck K, Decostere A, Vandamme P, Hänninen ML, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F. Multiplex PCR assay for differentiation of Helicobacter felis, H. bizzozeronii, and H. salomonis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1115–22. 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1115-1122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. Fitting linear Mixed-Effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. (2004) Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach, model selection and multimodel inference. Springer New York. 10.1007/B97636

- 6.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castiglioni V, Facchini RV, Mattiello S, Luini M, Gualdi V, Scanziani E, Recordati C. Enterohepatic Helicobacter spp. In colonic biopsies of dogs: molecular, histopathological and immunohistochemical Investigations. Vet Microbiol. 2012;159(1–2):107–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cattoli G, Bart A, Klaver PS, Robijn RJ, Beumer HJ, van Vugt R, Pot RG, van der Gaag I, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. Helicobacter acinonychis eradication leading to the resolution of gastric lesions in tigers. Veterinary Records. 2000;147(6):164–5. 10.1136/vr.147.6.164. PMID: 10975334. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Cleveland S, Laurenson MK, Taylor LH. Diseases of humans and their domestic mammals: pathogen characteristics, host range and the risk of emergence. Philosophical Trans Royal Soc B. 2001;356:991–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortez Nunes F, Mateus L, Teixeira T, Barradas S, de Witte P, Haesebrouck C, Amorim F, I. and, Gärtner F. Presence of Helicobacter pylori and H. suis DNA in free-range wild boars. Animals (Basel). 2021;11(5):1269. 10.3390/ani11051269. PMID: 33925029; PMCID: PMC8146769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dailidiene D, Ogura K, Zhang M, Mukhopadhyay AK, Eaton KA, Cattoli G, Kusters JG, Berg DE. Helicobacter acinonychis: genetic and rodent infection studies of a Helicobacter pylori-like gastric pathogen of cheetahs and other big cats. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewhirst FE, Shen Z, Scimeca MS, Stokes LN, Boumenna T, Chen T, Paster BJ, Fox JG. Discordant 16S and 23S rRNA gene phylogenies for the genus helicobacter: implications for phylogenetic inference and systematics. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(17):6106–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton KA, Dewhirst FE, Radin MJ, Fox JG, Paster BJ, Krakowka S, Morgan DR. Helicobacter acinonyx sp. nov., isolated from cheetahs with gastritis. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1993;43(1):99–106. 10.1099/00207713-43-1-99. PMID: 8379970. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Eppinger M, Baar C, Linz B, Raddatz G, Lanz C, Keller H, Morelli G, Gressmann H, Achtman M, Schuster SC. Who ate whom? Adaptive Helicobacter genomic changes that accompanied a host jump from early humans to large felines. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:1097–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng S, Ku K, Hodzic E, Lorenzana E, Freet K, Barthold SW. Differential detection of five mouse-infecting helicobacter species by multiplex PCR. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(4):531–6. 10.1128/CDLI.12.4.531-536.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox JG, Dangler CA, Sager W, Borkowski R, Gliatto JM. Helicobacter mustelae-associated gastric adenocarcinoma in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Vet Pathol. 1997;34(3):225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh P, Sarkar A, Ganguly M, et al. Helicobacter pylori strains harboring babA2 from Indian sub-population are associated with increased virulence in ex-vivo study. Gut Pathogens. 2016;8(1). 10.1186/s13099-015-0083-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Gibb R, Redding DW, Chin KQ, Donnelly CA, Blackburn TM, Newbold T, Jones KE. Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems. Nature. 2020;584(7821):398–402. 10.1038/s41586-020-2562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert MJ, Duim B, Zomer AL, Wagenaar JA. Living in cold blood: arcobacter, campylobacter, and Helicobacter in reptiles. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill J, Haydon TG, Rawdon TG, McFadden AM, Ha HJ, Shen Z, et al. Helicobacter bilis and Helicobacter trogontum: infectious causes of abortion in sheep. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2016;28(3):225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein EJC, Solnick JV. Clinical significance of Helicobacter species other than Helicobacter pylori. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):349–54. 10.1086/346038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen R, Thomson JM, Fox JG, El-Omar EM, Hold GL. Could Helicobacter organisms cause inflammatory bowel disease? FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;61(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herstad K, Moen A, Gaby JC, Moe L, Skancke E. (2018) Characterization of the fecal and mucosa-associated microbiota in dogs with colorectal epithelial tumors. PLoS ONE, 13(5), e0198342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Jakob W, Stolte M, Valentin A, Schröder H-D. Demonstration of Helicobacter pylori-like organisms in the gastric mucosa of captive exotic carnivores. J Comp Pathol. 1997;116(1):21–33. 10.1016/S0021-9975(97)80040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaakoush NO, Holmes J, Octavia S, Man SM, Zhang L, Castano-Rodrıguez N, Day AS, Leach ST, Lemberg DA, Dutt S, et al. Detection of Helicobacteraceae in intestinal biopsies of children with crohn’s disease. Helicobacter. 2010;15(6):549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakuta R, Yano H, Kanamori H, Shimizu T, Gu Y, Hatta M, Aoyagi T, Endo S, Inomata S, Oe C, et al. Helicobacter cinaedi infection of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(11):1942–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindahl JF, Grace D. The consequences of human actions on risks for infectious diseases: a review. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2015;5(1). 10.3402/iee.v5.30048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Linz B, Balloux F, Moodley Y, et al. An African origin for the intimate association between humans and Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2007;445:915–8. 10.1038/nature05562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Yu J, Huan Z, et al. Comparing the gut microbiota of Sichuan golden monkeys across multiple captive and wild settings: roles of anthropogenic activities and host factors. BMC Genomics. 2024;25:148. 10.1186/s12864-024-10041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madden T. (2002) The BLAST Sequence Analysis Tool. Oct. In: McEntyre J, Ostell J, editors. The NCBI Handbook [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2002 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21097/

- 34.Mangiaterra S, Marker L, Cerquetella M, Galosi L, Marchegiani A, Gavazza A, Rossi G. Chronic stress-related gastroenteric pathology in cheetah: relation between intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Biology (Basel). 2022;11(4):606. 10.3390/biology11040606. PMID: 35453805; PMCID: PMC9028982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maurer KJ, Ihrig MM, Rogers AB, Ng V, Bouchard G, Leonard MR, Carey MC, Fox JG. Identification of cholelithogenic enterohepatic Helicobacter species and their role in murine cholesterol gallstone formation. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4):1023–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melito PL, Munro C, Chipman PR, Woodward DL, Booth TF, Rodgers FG. Helicobacter winghamensis sp. nov., a novel Helicobacter sp. isolated from patients with gastroenteritis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(7):2412–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misra V, Pandey R, Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Indian enigma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(6):1503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell HM, Rocha GA, Kaakoush NO, O’Rourke JL, Queiroz DMM. The family Helicobacteraceae. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F, editors. The prokaryotes. Berlin (Germany): Springer; 2014. pp. 337–92. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mladenova-Hristova I, Grekova O, Patel A. Zoonotic potential of Helicobacter spp. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2017;50(3):265–9. 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moussa IM, Eljakee J, Beder M, Abdelaziz K, Mubarak AS, Dawoud TM, Hemeg HA, Alsubki RA, Kabli SA, Marouf S. Zoonotic risk and public health hazards of companion animals in the transmission of Helicobacter species. J King Saud Univ - Sci. 2021;33(6):101494. 10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101494. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ochoa S, Collado L. Enterohepatic Helicobacter species – clinical importance, host range, and zoonotic potential. Crit Reviews Mocrobiology. 2021;47(6):728–61. 10.1080/1040841X.2021.1924117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng W, Li H, Xu Y, Yan L, Tang Z, Hossein Mohseni A, Taghinezhad-S S, Tang X and Fu X. Association of Helicobacter bilis infection with the development of colorectal cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73(11–12):2785–95. 10.1080/01635581.2020.1862253 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Quiñones-Laveriano DM, De La Cruz-Vargas JA, Quintana-Gomez S, Failoc-Rojas VE, Lozano-Gutiérrez J, Mejia CR. The altitude of residential areas and clinical diagnosis of chronic gastritis in ambulatory patients of peru: A cross-sectional analytic study. Medwave. 2020. 10.5867/medwave.2020.06.7972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.R Core Team. R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramirez O, Altet L, Enseñat C, Vilà C, Sanchez A, Ruiz A. Genetic assessment of the Iberian Wolf Canis lupus signatus captive breeding program. Conserv Genet. 2006;7:861–78. 10.1007/s10592-006-9123-z. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rimbara E, Mori S, Matsui M, Suzuki S, Wachino J, Kawamura Y, Shen Z, Fox JG, Shibayama K. Molecular epidemiologic analysis and antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter cinaedi isolated from seven hospitals in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(8):2553–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, Sánchez-Gracia A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3299–302. 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schröder HD, Ludwig C, Jakob W, Reischl U, Stolte M, Lehn N. Chronic gastritis in tigers associated with Helicobacter acinonyx. Journal of Comparative Pathology. 1998;119(1):67–73. 10.1016/s0021-9975(98)80072-8. PMID: 9717128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Sharma PK, Suri TM, Venigalla PM, Garg SK, Mohammad G, Das P, Sood S, Saraya A, Ahuja V. Atrophic gastritis with high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori is a predominant feature in patients with dyspepsia in a high altitude area. Trop Gastroenterol. 2014;35(4):246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen Z, Fox JG, Dewhirst FE, Paster BJ, Foltz CJ, Yan L, Shames B, Perry L. Helicobacter rodentium sp. nov., a urease-negative Helicobacter species isolated from laboratory mice. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47(3):627–34. 10.1099/00207713-47-3-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon C. An evolving view of phylogenetic support. Syst Biol. 2022;71(4):921–8. 10.1093/sysbio/syaa068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snyder NFR, Derrickson SR, Beissinger SR, Wiley JW, Smith TB, Toone WD, Miller B. Limitations of captive breeding in endangered species recovery. Conserv Biol. 1996;10:338–48. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020338.x. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sommer F, Ståhlman M, Ilkayeva O, Arnemo JM, Kindberg J, Josefsson J, Newgard CB, Fröbert O, Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota modulates energy metabolism in the hibernating brown bear Ursus arctos. Cell Rep. 2016;14(7):1655–61. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tegtmeyer N, Traverso R, Rohde F, Oyarzabal M, Lehn OA, Schneider-Brachert N, Ferrero W, Fox RL, Berg JG, D.E. and, Backert S. Electron microscopic, genetic and protein expression analyses of Helicobacter acinonychis strains from a Bengal tiger. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71220. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071220. PMID: 23940723; PMCID: PMC3733902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terio KA, Munson L, Marker L, Aldridge BM, Solnick JV. Comparison of Helicobacter spp. In cheetahs Acinonyx jubatus) with and without gastritis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:229–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terio KA, Mitchell E, Walzer C, Schmidt-Küntzel A, Marker L, Citino S. Diseases impacting captive and free-ranging cheetahs. Cheetahs: Biology and Conservation. 2018;349–64. 10.1016/B978-0-12-804088-1.00025-3. PMCID: PMC7148644.

- 58.Waite DW, Vanwonterghem I, Rinke C, Parks DH, Zhang Y, Takai K, Sievert SM, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the class Epsilonproteobacteria and proposed reclassification to Epsilonbacteraeota (phyl. nov). Front Microbiol. 2017;8:682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wasimuddin, Čížková D, Bryja J, Albrechtová J, Hauffe HC, Piálek J. High prevalence and species diversity of Helicobacter spp. Detected in wild house mice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(22):8158–60. 10.1128/AEM.01989-12. PMID: 22961895; PMCID: PMC3485938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wasimuddin, Menke S, Melzheimer J, Thalwitzer S, Heinrich S, Wachter B, Sommer S. Gut microbiomes of free-ranging and captive Namibian cheetahs: diversity, putative functions and occurrence of potential pathogens. Mol Ecol. 2017;26(20):5515–27. 10.1111/mec.14278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu Q, Zhang S, Li L, Xiong L, Chao K, Zhong B, Li Y, Wang H, Chen M. Enterohepatic Helicobacter species as a potential causative factor in inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2015;94(45):e1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information with Genbank accession numbers PP961961 – PP962171.