Abstract

Background

Service quality plays a crucial role in shaping patient experience and satisfaction in prosthetic and orthotic services. However, limited research has examined the specific impact of SERVQUAL dimensions (Reliability, Assurance, Tangibility, Responsiveness, and Empathy) on patient satisfaction and patient experience in this field. This study aimed to assess the relationships between service quality, patient experience, and satisfaction, providing insights for healthcare improvement.

Methods

This cross-sectional study collected data from 307 patients receiving prosthetic and orthotic care at 14 centers across public, private, military, and NGO-operated facilities. A structured questionnaire based on the SERVQUAL model was administered, measuring patient experience, patient satisfaction, and service quality dimensions using a 5-point Likert scale. Structural equation modelling was conducted using IBM SPSS AMOS 28 to assess direct and indirect relationships among the study variables.

Results

The findings indicate that Responsiveness, Assurance, and Tangibility were the strongest predictors of patient experience and satisfaction (p < 0.001). Patient experience played a mediating role, reinforcing the importance of effective communication, timely service delivery, and competent care providers. Reliability significantly influenced PS (p < 0.001) but had no impact on PE (p = 0.386), while Empathy did not significantly affect PS (p = 0.311), suggesting that practical aspects such as device functionality and efficiency may be prioritized over emotional considerations in P&O care.

Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of service quality in shaping patient experience and satisfaction in P&O services. Responsiveness, Assurance, and Tangibility should be prioritized to enhance patient-centered care. Policymakers should focus on standardized training programs, infrastructure improvements, and public-private partnerships to ensure accessible and high-quality P&O services globally. Future research should explore longitudinal effects of service quality on patient outcomes to further optimize healthcare delivery in this field.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-025-13172-z.

Keywords: Service quality, Patient satisfaction, Patient experience, SERVQUAL, Prosthetics and orthotics, Structural equation modelling, Healthcare quality

Background

The quality of healthcare services has become a central focus in improving patient satisfaction and outcomes. One widely recognized framework for evaluating service quality in healthcare is the SERVQUAL (Service Quality) model, developed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1988) [1]. SERVQUAL is a multidimensional instrument designed to measure service quality by assessing gaps between patient expectations and actual service experiences across five key dimensions: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [1]. This model has been extensively used in various healthcare settings, including hospitals, dental services, and rehabilitation programs, to assess service quality and guide improvements [2–5].

In the field of prosthetics and orthotics (P&O), service quality is a critical determinant of patient satisfaction. Prosthetic and orthotic users rely on these devices for mobility, independence, and overall well-being [6]. The delivery of high-quality P&O services encompasses not only the technical precision of the devices but also the efficiency of service delivery, patient-centered care, and the responsiveness of healthcare providers [5–7]. Studies have shown that patient satisfaction in P&O is linked to both the technical aspects of device fitting and the quality of interactions with service providers [8–10]. Therefore, assessing the quality of P&O services through SERVQUAL provides valuable insights into areas that require improvement to enhance patient experiences and outcomes.

Each SERVQUAL dimension plays a crucial role in shaping patient perceptions of prosthetic and orthotic services. Tangibility (T) relates to the physical environment of the care facility, including accessibility, waiting rooms, and the cosmetic appearance of the provided devices, all of which contribute to patient perception of service quality [11, 12]. Reliability (RE) refers to the consistency and accuracy of service delivery, including clear communication, adequate information on prosthetic and orthotic devices, and efficient interactions with insurance providers, all of which influence patient trust in care providers [1, 13, 14]. Responsiveness (R) measures the willingness of service providers to assist patients promptly, minimize waiting times, and ensure accessibility of prosthetic and orthotic services [12]. Assurance (A) involves the competence and courtesy of healthcare professionals, as well as their ability to instill confidence in patients by providing clear guidance on device use, maintenance, and expected outcomes [12]. Empathy (E) encompasses the personalized attention, privacy, and responsiveness of healthcare professionals to patient concerns, ensuring a patient-centered approach in prosthetic and orthotic care [11, 12].

Globally, the demand for P&O services is rising due to factors such as aging populations, increasing prevalence of diabetes-related amputations, and traumatic injuries [15, 16]. While previous studies have explored service quality in various healthcare disciplines, there remains a gap in understanding how P&O services align with patient expectations across different healthcare systems. Evaluating P&O service quality from a patient-centered perspective can provide guidance for improving rehabilitation programs and optimizing resource allocation [17, 18].

This study contributes to the broader understanding of P&O service quality by applying the SERVQUAL framework in a Middle Eastern context. Jordan serves as an illustrative example of a low- to middle-income country (LMIC) with a diverse healthcare system, where prosthetic and orthotic services are provided through a network of 14 rehabilitation centers, including government, military, private, and NGO-operated centers. In Jordan, prosthetic and orthotic services are not universally covered by a centralized insurance scheme. Coverage varies by sector: military and governmental employees may receive full or partial subsidies through the Royal Medical Services and Ministry of Health, while services through private or NGO sectors often require out-of-pocket payments or partial external funding. This fragmentation creates disparities in access and satisfaction among users. The country’s increasing demand for P&O services, driven by trauma-related amputations, chronic diseases such as diabetes, and congenital conditions, reflects challenges common to many healthcare systems in similar economic and structural settings [19–22].

By assessing service quality dimensions including, tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy this study aimed to provide insights that can be extrapolated to other healthcare systems facing similar challenges. Identifying strengths and gaps in P&O service delivery will support evidence-based improvements, contributing to enhanced patient care and overall healthcare efficiency. Despite the global relevance of patient satisfaction and service quality, limited research has examined these relationships in the context of prosthetic and orthotic care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Most existing studies have focused on either technical outcomes or general satisfaction without applying structured service quality frameworks. Moreover, there is a noticeable gap in evidence regarding how individual SERVQUAL dimensions influence both patient experience and satisfaction in real-world, multi-provider rehabilitation systems such as in Jordan. This study addresses this gap by providing empirical data from diverse P&O centers in Jordan, making it one of the few to investigate these constructs in a Middle Eastern LMIC context using a validated, multidimensional service quality model.

This study aimed to assess the impact of service quality on patient satisfaction and experience in prosthetics and orthotics centers in Jordan using the SERVQUAL model. In particular, the study explores the mediating role of patient experience, uses cross-sectoral sampling across public, private, military, and NGO-operated centers, and applies structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the relationships between SERVQUAL dimensions, patient experience, and satisfaction.

The findings from this research will not only inform healthcare providers and policymakers in Jordan but also serve as a reference for similar regions where P&O service quality remains underexplored.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a cross-sectional quantitative design with mediation analysis to examine the impact of service quality dimensions, as defined by the SERVQUAL model, on patient satisfaction (PS) through the mediating role of patient experience (PE). This design was selected for its suitability in capturing relationships between multiple variables at a single point in time, particularly when assessing service perception across diverse healthcare providers. The SERVQUAL model provided the conceptual basis for the questionnaire structure and the hypothesized relationships in the structural equation model. Based on established theoretical and empirical work [1, 6, 23–25], each latent construct (Responsiveness, Assurance, Tangibility, Reliability, Empathy, PE, and PS) was represented by four indicators derived from validated SERVQUAL questionnaires and adapted to the P&O context. This design enabled a robust evaluation of both direct and indirect pathways from service quality dimensions to satisfaction outcomes.

Data were collected through a structured questionnaire survey administered in July 2024 at P&O 14 centers overing public, private, military-affiliated, and NGO-operated facilities. These included centers operated under four main service providers: Royal Medical Services (RMS), Ministry of Health (MoH), Private P&O Clinics, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). The survey included a five-point Likert scale, where participants rated their agreement with each statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with 3 as the neutral response. The survey included 3 demographic questions, and 28 items (4 items for each of R = Responsiveness, A = Assurance, E = Empathy, T = Tangibility, RE = Reliability, PE = Patient Experience, and PS = Patient satisfaction). The items used to measure each construct were adapted from established SERVQUAL instruments used in healthcare research [1, 6, 23–25]. Adaptations were based on terminology and service processes relevant to rehabilitation and assistive technology, ensuring content relevance while maintaining conceptual integrity. The survey was carefully designed to gather relevant information directly from research respondents, ensuring that their responses reflect first hand insights and opinions (The full questionnaire is provided Appendix 1).

Based on the SERVQUAL framework and previous empirical research, the following hypotheses were developed, H1-5) Each service quality dimension has a significant positive effect on Patient Experience (PE). H6-10) Each service quality dimension has a significant positive effect on Patient Satisfaction (PS). H11) Patient Experience (PE) has a significant positive effect on Patient Satisfaction (PS).

A convenience sampling method was chosen due to logistical constraints, variable patient availability, and the need for immediate feedback on service quality. While convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, efforts were made to ensure diversity in service providers and patient demographics, enhancing the study’s generalizability. The study included 307 valid responses, meeting the minimum sample size requirements for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [26].

Data collection method

The survey questionnaire was filled in by each patient at each of the prosthetics and orthotics centers. The questionnaire was filled and returned on the same day. The inclusion criteria were respondents were required to be 12 years or older. For participants under 16 years old, informed consent to participate was obtained from the parents or legal guardians in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the National Ethics Committee for Health Research. Additionally, all participants required to have the ability to understand the questions and communicate verbally without any cognitive impairment. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents (or their guardians, if under 16) provided informed written consent before completing the questionnaire. Surveys were administered and collected on the same day to ensure consistency in data collection.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Jordanian Ministry of Health, National Ethics Committee for Health Research (MOH/REC/2023/415). All responses were collected anonymously without recording names, contact information, or identifiable data. Completed questionnaires were coded numerically and securely stored in password-protected digital files accessible only to the research team. Survey administration was conducted in a private area within each center to maintain confidentiality during participation.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28 for descriptive statistics and IBM SPSS AMOS 28 for structural equation modeling (SEM). The sample size of 307 valid responses was determined using G*Power 3.1 for a multiple regression model with a medium effect size (f² = 0.15), power (1 − β) = 0.80, and α = 0.05. This exceeded the minimum requirement for structural equation modeling (SEM), ensuring robust statistical analysis. Data were screened for missing values, normality violations, and outliers. Missing data were handled using multiple imputations, and normality was assessed via Shapiro-Wilk test and Mardia’s coefficient for multivariate normality. Outliers were examined using Mahalanobis distance and Cook’s distance, with extreme cases removed if they significantly influenced results. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies (N, %) for categorical variables, were reported based on data distribution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (N = 307)

| Item | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18 or below | 80 | 26.1 |

| 19–29 | 46 | 15.0 | |

| 30–49 | 102 | 33.2 | |

| 50 or above | 79 | 25.7 | |

| Sex | Female | 115 | 37.5 |

| Male | 192 | 62.5 | |

| Service Provider | Government (MOH) | 160 | 52.1 |

| Military | 94 | 30.6 | |

| Private | 11 | 3.6 | |

| NGOs | 42 | 13.7 | |

| Total | 307 | 100.0 | |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS 28 to assess construct validity, including: Factor loadings (threshold: λ ≥ 0.50), Composite reliability (CR) (acceptable if CR ≥ 0.70), Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (acceptable if AVE ≥ 0.50) and Cronbach’s alpha (acceptable if α ≥ 0.70) [27, 28].

The measurement model was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with factor loadings (acceptable at λ ≥ 0.50), composite reliability (CR ≥ 0.70), average variance extracted (AVE ≥ 0.50), and Cronbach’s alpha (α ≥ 0.70) [28, 29]. Model fit indices were evaluated using recommended cutoffs: χ²/df (< 3.0), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (≥ 0.90), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) (≥ 0.90), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (≤ 0.08), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) (≤ 0.08) [30].

After validating the measurement model, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed to examine direct and indirect effects of SERVQUAL dimensions on patient satisfaction (PS) through patient experience (PE) as a mediator. Regression coefficients (β), standard errors (SE), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and P-values were reported. Model fit was assessed using R² values.

Bootstrapping (5,000 resamples, bias-corrected CI) was conducted in IBM SPSS AMOS 28 to test mediation effects, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Descriptive analysis

Out of the 344 responses received, only 307 were analyzed, as 37 responses did not meet the inclusion criteria for survey completion. The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. The majority of respondents were male (62.5%). Additionally, more than half (52.1%) of the respondents received their services from the Ministry of Health (MOH).

Validity and reliability by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Table 2 presents the standardized factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) values. The factor loadings for all items ranged from 0.551 to 0.920, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.50 [27].

Table 2.

Reliability analysis and factor analysis test

| Latent Variable | Indicator | FL | AVE (> 0.50) |

CR (> 0.70) |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

RE Mean = 3.32 SD = 0.836 Discriminant Validity Assessment = 0.757 |

|||||

| Re4 | 0.908 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.93 | |

| Re3 | 0.891 | ||||

| Re2 | 0.920 | ||||

| Re1 | 0.808 | ||||

|

A Mean = 3.883 SD = 0.736 Discriminant Validity Assessment = 0.759 |

A4 | 0.775 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| A3 | 0.854 | ||||

| A2 | 0.759 | ||||

| A1 | 0.773 | ||||

|

E Mean = 3.854 SD = 0 0.758 Discriminant Validity Assessment = 0.779 |

E4 | 0.799 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| E2 | 0.747 | ||||

| E3 | 0.551 | ||||

| E1 | 0.825 | ||||

|

T Mean = 4.102 SD = 0.682 Discriminant Validity Assessment = 0.771 |

T4 | 0.704 | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.88 |

| T3 | 0.818 | ||||

| T2 | 0.864 | ||||

| T1 | 0.843 | ||||

|

R Mean = 3.988 SD = 0.705 Discriminant Validity Assessment = 0.744 |

R4 | 0.836 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.86 |

| R3 | 0.865 | ||||

| R2 | 0.828 | ||||

| R1 | 0.854 | ||||

|

PE Mean = 3.854 SD = 0.665 Discriminant Validity Assessment = 0.781 |

PE1 | 0.859 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| PE2 | 0.837 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.685 | ||||

| PE4 | 0.839 | ||||

|

PS Mean = 3.852 SD = 0.722 Discriminant Validity Assessment = 0.751 |

PS1 | 0.644 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| PS2 | 0.699 | ||||

| PS3 | 0.661 | ||||

| PS4 | 0.634 |

FL Factor Loading, FLS Factor Loading Squared, AVE Average Variance Extracted, CR Composite Reliability, R Responsiveness, A Assurance, E Empathy, T Tangibility, RE Reliability, PE Patient Experience, and PS Patient satisfaction

The results indicate that all constructs exhibit strong internal consistency, with CR values ranging from 0.74 to 0.88 and AVE values between 0.50 and 0.78 both exceeding the recommended benchmarks [28]. All latent variables meet the convergent validity standard. Additionally, Cronbach alpha values for all constructs exceed 0.77, ranging from 0.77 to 0.93, affirming their reliability. Discriminant Validity Assessment were accepted for all variables.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis

The structural model was evaluated using path analysis within the SEM framework. Regression weights, standard errors (SE), critical ratios (CR), and p-values are summarized in (Table 3).

Table 3.

Structural equation modelling regression weights

| Factor | Patient Experience | Patient Satisfaction | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Effect | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Effect | |

| Reliability | 0.038 | 0.044 | 0.867 | 0.386 | 0.040 | 0.106 | 0.026 | 4.073 | *** | 0.188 |

| Assurance | 0.276 | 0.057 | 4.863 | *** | 0.237 | 0.184 | 0.037 | 5.019 | *** | 0.269 |

| Empathy | 0.170 | 0.051 | 3.314 | *** | 0.162 | −0.030 | 0.029 | − 0.013 | 0.311 | − 0.048 |

| Tangibility | 0.231 | 0.066 | 3.503 | *** | 0.168 | 0.182 | 0.041 | 4.425 | *** | 0.225 |

| Responsiveness | 0.563 | 0.052 | 10.843 | *** | 0.557 | 0.328 | 0.044 | 7.394 | *** | 0.551 |

|

Patient Experience ➜ Patient Satisfaction |

0.192 | 0.042 | 4.582 | *** | 0.325 | |||||

SE Standard errors of the regression weights, CR Critical Ratio, P p-value (*<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001)

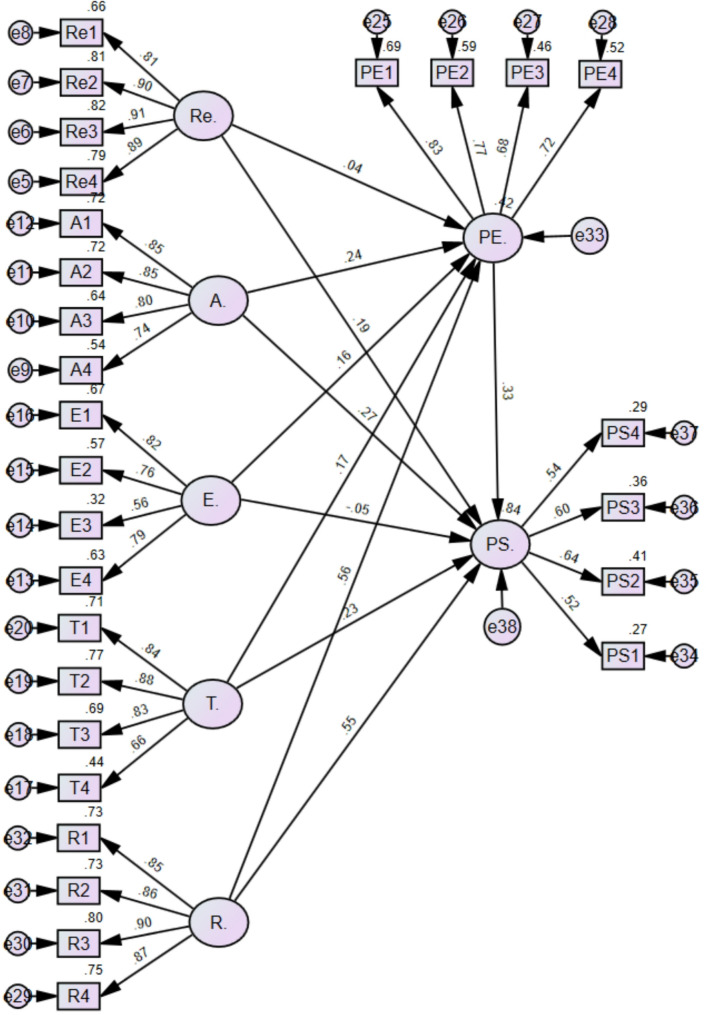

Findings indicated that nine out of eleven hypotheses were supported, demonstrating significant relationships between SERVQUAL dimensions, PE, and PS. Responsiveness showed the strongest effect on PE (β = 0.557, p < 0.001) and PS (β = 0.551, p < 0.001), emphasizing the importance of timely and accessible services. Tangibility (β = 0.231, p < 0.001) and Assurance (β = 0.237, p < 0.001) were also significant predictors of PE, while Assurance (β = 0.269, p < 0.001) and Tangibility (β = 0.168, p < 0.001) had direct positive effects on PS. Reliability significantly influenced PS (β = 0.188, p < 0.001), but its effect on PE was not statistically significant (p = 0.386). Empathy was a significant predictor of PE (β = −0.048, p < 0.001) but did not show a direct effect on PS (p = 0.311). PE had a direct positive influence on PS (β = 0.325, p < 0.001), confirming its mediating role in the model.

These findings highlight the key role of Tangibility, Responsiveness, and Assurance in shaping patient experience and satisfaction. Additionally, while Empathy contributed to PE, its direct effect on PS was not significant, suggesting that its impact may be mediated through other service quality dimensions.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the impact of service quality dimensions (SERVQUAL) on patient experience (PE) and patient satisfaction (PS) in prosthetic and orthotic (P&O) services. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), the findings (Table 3; Fig. 1) demonstrated that Responsiveness, Tangibility, and Assurance were the most influential factors in shaping PE and PS, reinforcing the significance of timely service delivery, accessibility, and provider competence in patient-centered care. Patient experience played a mediating role, further highlighting the importance of ensuring that interactions with service providers are smooth, informative, and reassuring. These findings align with previous research in healthcare quality assessment, emphasizing that efficient communication, professional guidance, and service availability are central to improving patient satisfaction [2, 6, 12, 31].

Fig. 1.

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), T = Tangibility, RE = Reliability R = Responsiveness, A = Assurance, E = Empathy, PE = Patient Experience, PS = Patient satisfaction

Studies in various healthcare settings have consistently found that timely service delivery, clear communication, and provider competence significantly enhance patient satisfaction and experience [32, 33]. Responsiveness, which emerged as the most influential factor in both patient experience (β = 0.557, p < 0.001) and patient satisfaction (β = 0.551, p < 0.001) in this study, has been previously identified as a key determinant of healthcare quality, particularly in rehabilitation services where delays can directly impact functional outcomes and quality of life [1, 34].

Similarly, the significant influence of Assurance highlights the role of healthcare provider competence and trust in P&O services. Assurance involves staff knowledge, courtesy, and the ability to instill confidence in patients, all of which contribute to positive patient-provider interactions [6, 34]. In prosthetic and orthotic services, where users require complex, individualized care, the reassurance provided by knowledgeable clinicians is particularly relevant. These findings align with research emphasizing that well-trained professionals and effective communication strategies foster higher levels of trust, patient engagement, and adherence to rehabilitation protocols [7].

Tangibility’s significant effect highlights the importance of the physical environment and equipment in shaping patient experience. Several studies have confirmed that well-maintained facilities and updated technology positively affect patient satisfaction by improving comfort and perceived quality of care [12, 35]. In P&O centers, where physical interaction with assistive devices is essential, the role of tangibles may be even more pronounced. These findings support the broader understanding that service environments contribute significantly to patient-centered care and overall satisfaction in rehabilitation services.

The non-significant impact of Reliability on Patient Experience (p = 0.386) contrasts with some studies that have identified Reliability consistency in service delivery, clear communication, and dependable follow-up as a key factor in shaping patient perceptions [6, 12, 14, 34]. However, Reliability did significantly influence Patient Satisfaction, suggesting that while patients may not immediately associate reliability with their overall experience, they do recognize its importance in their long-term satisfaction with P&O services. This discrepancy may stem from differences in patient expectations, where aspects such as technical competence and timely service delivery are prioritized during interactions with providers, while reliability becomes more apparent when assessing long-term service outcomes. Additionally, factors such as structured appointment systems, consistency in device quality, and follow-up care may contribute more directly to satisfaction rather than the immediate experience. Further research is needed to determine whether this pattern is specific to the P&O sector or reflects a broader trend in healthcare service evaluations.

Similarly, the unexpected lack of a significant relationship between empathy and patient satisfaction (p = 0.311) challenges findings from studies that emphasize the role of emotional connection in healthcare [11, 12]. Empathy, which involves healthcare providers’ ability to understand and address patient concerns, is generally considered a key determinant of positive patient-provider relationships and overall satisfaction [11]. However, in P&O services, practical considerations, such as device functionality, technical expertise, and service efficiency may take precedence over emotional aspects when patients evaluate their overall satisfaction [6]. This aligns with research suggesting that in assistive technology and rehabilitation services, patients often prioritize outcome-driven factors (such as mobility and comfort) over interpersonal care quality [6].

The strong influence of Reliability on both PE and PS underscores the necessity for P&O facilities to maintain consistent and dependable services. Ensuring that devices are delivered on time and function as promised can significantly enhance patient satisfaction.

The findings of this study offer important theoretical implications within the SERVQUAL framework. The results confirm that service quality dimensions particularly Responsiveness, Tangibility, and Assurance are strong predictors of patient satisfaction and experience in prosthetic and orthotic services. This aligns with SERVQUAL theory, which suggests that tangible service elements and timely, competent interaction with service providers shape consumer perceptions of quality [1]. However, the limited impact of Empathy and Reliability suggests that SERVQUAL dimensions may vary in relative importance depending on healthcare context. In the case of P&O, where users depend on functional devices and efficient service processes, patients may prioritize technical and procedural reliability over emotional or interpersonal engagement [6]. These results emphasise the need to interpret SERVQUAL dimensions flexibly when applied in assistive technology and rehabilitation settings. Additionally, the confirmed mediating role of patient experience highlights how perceived service quality influences satisfaction indirectly emphasizing the theoretical importance of experience as a pathway in the SERVQUAL-patient satisfaction link.

Beyond its practical applications, this study enhances the theoretical development of the SERVQUAL model within assistive technology and rehabilitation. The varying importance of certain dimensions, especially the minimal impact of Empathy and Reliability on patient satisfaction, indicates a need to reassess how these factors are defined and evaluated in specialized services like P&O. Since patient priorities in this field focus heavily on functional and technical aspects, future versions of SERVQUAL might benefit from adding dimensions such as technical precision or device usability to strengthen its predictive accuracy. Additionally, the strong influence of Responsiveness on both patient experience and satisfaction suggests that related survey items may need more emphasis or detailed refinement. These findings open the way for a more context-specific SERVQUAL model designed for P&O and rehabilitative services, particularly in LMICs where service delivery is shaped by unique structural challenges.

From a policy-making perspective, these findings highlight the need for stronger regulations and monitoring mechanisms to ensure high-quality P&O services globally. Healthcare systems worldwide, particularly those in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), can benefit from implementing targeted strategies to enhance patient experience and satisfaction in P&O care. Based on the study’s findings, the following policy recommendations can be considered: (1) Establishing competency-based education and continuous professional development programs that would enhance Assurance and Reliability, ensuring that clinicians are well-equipped to provide high-quality, patient-centered P&O care. (2) Upgrading P&O facilities, ensuring accessibility, and integrating modernized equipment and technology that would enhance Tangibility, directly impacting patient comfort and perception of care. (3) Implementing national and international quality assessment protocols can help monitor patient satisfaction and experience, allowing policymakers to identify and address gaps in service delivery. (4) Establishing a collaboration between government agencies, private healthcare providers, NGOs, and research institutions would ensure equitable access to high-quality P&O services, particularly in regions where prosthetic and orthotic care remains underfunded or fragmented.

By implementing these measures, healthcare policymakers and administrators worldwide can drive improvements that will ultimately enhance patient outcomes and satisfaction in P&O services across diverse healthcare systems. While Jordan serves as an illustrative example of LMICs, these recommendations are broadly applicable to other healthcare environments facing similar challenges in service quality regulation, accessibility, and patient-centered care.

Some study limitations exist. The use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings beyond the study population. Additionally, this non-random approach may introduce potential response bias, as those who chose to participate might differ systematically from those who did not, possibly influencing the distribution of satisfaction scores or experiences. The data used are cross-sectional in nature and do not capture the changes in the perceived service quality of the providers in different tiers. Additionally, the study relies on self-reported data, which may introduce bias due to social desirability bias or recall limitations. Future studies should explore the reasons behind the non-significant effects of Reliability and Empathy on patient experience and satisfaction in this context. Longitudinal or mixed-methods research could provide deeper insight into how these perceptions evolve and how different sampling strategies affect representativeness.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insight into how patients perceive service quality in prosthetic and orthotic (P&O) care using a structured, multidimensional instrument grounded in the SERVQUAL model. By capturing first-hand patient feedback across five key service domains, the results highlight the service attributes most closely linked to satisfaction and experience. The findings underscore that in the context of assistive technology and rehabilitation, aspects such as timely service, professional competence, and the physical service environment matter more to patients than emotional or interpersonal dimensions alone.

These findings suggest that patient-centered quality improvement efforts should prioritize operational responsiveness, assurance through trained staff, and investment in tangible aspects of service delivery. Additionally, the mediating role of patient experience affirms the importance of not only what services are delivered, but how patients perceive their interactions throughout the care process.

As demand for P&O services grows globally, particularly in low- and middle-income settings, these insights can inform more responsive and effective care models tailored to patient expectations.

Future research should expand on these findings by including larger, more diverse populations across multiple countries or regions to enhance generalizability. Longitudinal studies could help explore how perceptions of service quality evolve over time, particularly in response to organizational or policy-level changes in rehabilitation services. Additionally, qualitative or mixed-methods approaches could provide deeper insights into why certain dimensions, such as empathy or reliability, may be perceived as less impactful by patients in prosthetics and orthotics care. Investigating the perspectives of service providers alongside users could also help align expectations and service delivery standards.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AMOS

Analysis of Moment Structures

- AVE

Average Variance Extracted

- CFA

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- CFI

Comparative Fit Index

- CR

Composite Reliability

- CR (in SEM results)

Critical Ratio

- FL

Factor Loading

- LMICs

Low–and Middle–Income Countries

- MoH

Ministry of Health

- NGO

Non–Governmental Organization

- P&O

Prosthetics and Orthotics

- PE

Patient Experience

- PS

Patient Satisfaction

- RMS

Royal Medical Services

- RMSEA

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SEM

Structural Equation Modeling

- SERVQUAL

Service Quality Model

- SRMR

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual

- TLI

Tucker–Lewis Index

- A

Assurance (Competence and courtesy of healthcare professionals)

- E

Empathy (Personalized attention, privacy, and responsiveness)

- R

Responsiveness (Prompt assistance and accessibility of services)

- RE

Reliability (Consistency and accuracy of service delivery)

- T

Tangibility (Physical environment, accessibility, and appearance of devices)

Authors’ contributions

M.A. and A.A. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, software, resources, project administration, funding acquisition, validation, and writing– original draft preparation. H.A. contributed to methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, and writing– original draft preparation. A.M. contributed to validation and writing– original draft preparation. B.M. contributed to methodology, funding acquisition, formal analysis, data curation, and conceptualization. N.A., A.S., E.D., and D.V. contributed to writing– review & editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the dataset is very large and to avoid data misuse but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Respondents were required to be 12 years or older. For participants under 16 years old, informed consent to participate was obtained from the parents or legal guardians in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the National Ethics Committee for Health Research. Additionally, all participants required to have the ability to understand the questions and communicate verbally without any cognitive impairment. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents (or their guardians, if under 16) provided informed written consent before completing the questionnaire. Surveys were administered and collected on the same day to ensure consistency in data collection.

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Jordanian Ministry of Health, National Ethics Committee for Health Research (MOH/REC/2023/415).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perc. J Retail. 1988;64(1):12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang YL, et al. Contribution and trend to quality Research–a literature review of SERVQUAL model from 1998 to 2013. Informatica Economica. 2015;19(1). 10.12948/issn14531305/19.1.2015.03.

- 3.Jonkisz A, Karniej P, Krasowska D. The servqual method as an assessment tool of the quality of medical services in selected Asian countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):7831. 10.3390/ijerph19137831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christoglou K, Vassiliadis C, Sigalas I. Using SERVQUAL and Kano research techniques in a patient service quality survey. World Hosp Health Services: Official J Int Hosp Federation. 2006;42(2):21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geertzen J, et al. Consumer satisfaction in prosthetics and orthotics facilities. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2002;26(1):64–71. 10.1080/03093640208726623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosmans J, Geertzen J, Dijkstra PU. Consumer satisfaction with the services of prosthetics and orthotics facilities. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2009;33(1):69–77. 10.1080/03093640802403803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baars EC, et al. Prosthesis satisfaction in lower limb amputees: A systematic review of associated factors and questionnaires. Medicine. 2018;97(39):e12296. 10.1097/MD.0000000000012296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legro MW, et al. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931–8. 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinemann AW, Bode R, O’reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191–206. 10.1080/03093640308726682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alauddin MF, Susmartini S, Herdiman L. Study of 3D printing layered Fiber fabric filaments as an alternative to polypropylene materials in ankle foot orthosis for children with cerebral palsy. Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Industri. 2023;22(1):161–70. 10.23917/jiti.v22i1.21433. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e76–84. 10.3399/bjgp13X660814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fachri M. The effect of tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy aspects on hospitalization services in hospitals on patient satisfaction. Int J Psychol Health Sci. 2024;2(2):39–51. 10.38035/ijphs.v2i2.522. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–8. 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnusson L, Ahlström G. Patients’ satisfaction with lower-limb prosthetic and orthotic devices and service delivery in Sierra Leone and Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:1–13. 10.1186/s12913-017-2044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z, et al. Global trends and current status of amputation: bibliometrics and visual analysis of publications from 1999 to 2021. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2022:101097. 10.1097/PXR.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Walicka M, et al. Amputations of lower limb in subjects with diabetes mellitus: reasons and 30-day mortality. J Diabetes Res. 2021;2021(1):8866126. 10.1155/2021/8866126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnusson L. Professionals’ perspectives of prosthetic and orthotic services in tanzania, malawi, Sierra Leone and Pakistan. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2019;43(5):500–7. 10.1177/0309364619863617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harkins CS, McGarry A, Buis A. Provision of prosthetic and orthotic services in low-income countries: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2013;37(5):353–61. 10.1177/0309364612470963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health J. Centers for Prosthetics and Orthotics in Jordan. 2025. https://www.moh.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/AR/license_announcemment/%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%83%D8%B2_%D8%A3%D8%B7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%81_%D8%B5%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%A9_%D9%88%D8%AC%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%A6%D8%B1.pdf.

- 20.Al-Masa’fah W, Abushaikha I, Bwaliez OM. Exploring the role of additive manufacturing in the prosthetic supply chain: qualitative evidence. TQM J. 2024. 10.1108/TQM-02-2024-0071. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cross ICotR. Jordan: Facts and Figures for the First Half of 2024. 2024. cited 2025; Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/report/jordan-facts-figures-first-half-2024.

- 22.International H. Jordan Country Card 2023. 2023. Available from: https://www.hi-us.org/sn_uploads/federation/country/pdf/JORDAN_Country_Card_EN_2023_1.pdf. Cited 2025 25/1.

- 23.Ramstrand N, Mussa A, Gigante I. Factors influencing satisfaction with prosthetic and orthotic services–a National cross-sectional study in Sweden. Disabil Rehabil. 2024:1–8. 10.1080/09638288.2024.2319342. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Utami F, Argianto A. Perceived service quality and user satisfaction with Orthotic-Prosthetic devices and services among individual with physical disabilities. Indonesian J Disabil Stud. 2023;10(2):319–30. 10.21776/ub.ijds.2023.10.02.15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baghbanbashi A, et al. Evaluation of user’s satisfaction with orthotic and prosthetic devices and services in orthotics and prosthetics center of Iran university of medical sciences. Can Prosthetics Orthot J. 2022;5(1). 10.33137/cpoj.v5i1.37981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Westland JC. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2010;9(6):476–87. 10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bollen KA, Hoyle RH. Latent variables in structural equation modeling. Handb Struct Equation Model. 2012;1:56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009.

- 29.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 5th ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2023.

- 30.Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge; 2013 Jun 17.

- 31.Coulter A, Oldham J. Person-centred care: what is it and how do we get there? Future Healthc J. 2016;3(2):114–6. 10.7861/futurehosp.3-2-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf JA, et al. Reexamining defining patient experience: the human experience in healthcare. Patient Experience J. 2021;8(1):16–29. 10.35680/2372-0247.1594. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkowitz B. The patient experience and patient satisfaction: measurement of a complex dynamic. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016;21(1). 10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No01Man01. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Andriani V, Murti B. The Impact of Reliability, Responsiveness, and Assurance on Patient Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis. in The International Conference on Public Health Proceeding. 2024. 10.26911/ICPH11/Management/2024.AB04. [DOI]

- 35.Bitner MJ. Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J Mark. 1992;56(2):57–71. 10.1177/002224299205600205. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the dataset is very large and to avoid data misuse but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.