Abstract

Background

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a prevalent concern among adolescent girls. Childhood experiences of security or insecurity are recognized as significant foundational factors influencing body image and, consequently, the development of BDD. Adolescents with a history of childhood trauma may face an elevated risk of developing psychiatric conditions, including obsessive-compulsive disorder and BDD. This study, therefore, aimed to predict BDD symptoms based on childhood trauma, with self-compassion acting as a mediating factor. This framework integrates principles from cognitive-behavioral theory and attachment theory. Specifically, cognitive distortions stemming from cognitive-behavioral patterns, coupled with diminished self-esteem and self-worth as conceptualized by attachment theory, are believed to contribute to lower self-compassion, subsequently leading to a higher incidence of BDD symptoms.

Methods

A cross-sectional design employing structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to construct an optimal model for BDD symptoms, where the mediating role of self-compassion was tested in the relationship between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms. The study population comprised female students aged 16 to 22 in the cities of Meybod and Ardakan during the 2023–2024 academic year. A non-random convenience sample of 300 participants was selected. Data were collected using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale-Modified for BDD (BDD-YBOCS), and the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Statistical analyses, including Pearson’s correlation coefficient and stepwise multiple regression, were performed using SPSS-26 software. SEM analyses were conducted using AMOS-24 software.

Results

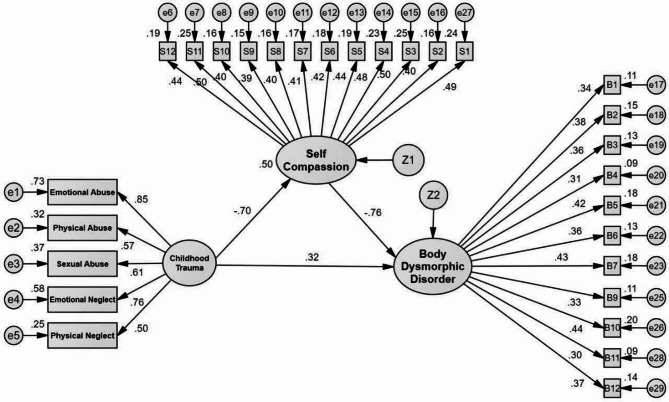

The study’s results indicated several significant relationships among the variables. Childhood trauma was found to have a significant negative direct effect on self-compassion (β=−0.704, p < 0.001), suggesting that higher levels of trauma are associated with lower self-compassion and vice versa. Conversely, childhood trauma exhibited a significant positive direct effect on BDD symptoms (β = 0.321, p < 0.001), indicating that increased trauma predicts more severe BDD symptoms. Furthermore, self-compassion demonstrated a considerable negative direct impact on BDD symptoms (β=−0.765, p < 0.001), implying that low self-compassion is linked to increased BDD symptomatology and vice versa. Crucially, the Sobel test statistic of 3.216 (exceeding the critical value of 1.96) confirmed that self-compassion significantly mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms (β = 0.538, p < 0.001). This mediation model suggests that self-compassion plays a vital role in explaining how childhood trauma contributes to the development of BDD symptoms.

Conclusion

The finding demonstrates a robust model fit, confirming self-compassion’s mediating role in the association between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms. Consequently, interventions aimed at enhancing self-compassion, such as group education programs and therapeutic approaches grounded in self-compassion therapy delivered in established treatment centers, could effectively mitigate the impact of childhood trauma. Such interventions are anticipated to lead to a reduction in BDD symptomatology, particularly by decreasing cognitive distortions related to body image and fostering greater self-acceptance.

Keywords: Body dysmorphic disorder, Childhood trauma, Iran, Self-compassion, Female youth

Plain language summary

Childhood trauma, alongside other interpersonal and familial challenges, poses a significant threat to the mental well-being of adolescents. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is one condition in which childhood trauma is recognized as a substantial contributing factor to its development and prevalence. This study aimed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the association between childhood trauma and body dissatisfaction among young women, an area previously underexplored. Specifically, the present research investigated whether self-compassion mediates the prediction of BDD symptoms based on experiences of childhood trauma. Data analysis revealed a positive correlation between childhood trauma, self-criticism, and body dissatisfaction. The mediation model demonstrated that higher levels of childhood trauma were associated with increased self-criticism (i.e., reduced self-compassion). Furthermore, lower self-compassion was significantly linked to greater body dissatisfaction. Consequently, the findings indicate that childhood trauma directly contributes to increased body dissatisfaction and indirectly influences BDD symptoms through its negative relationship with self-compassion. These results underscore the critical importance of childhood trauma in the development of body dissatisfaction among adult women, identifying self-compassion as a key mediating factor in this relationship. Early identification of childhood trauma could enhance quality of life and potentially prevent the onset of body dissatisfaction. Moreover, therapeutic interventions designed to cultivate self-compassion may serve as a crucial preventative measure against the progression of body dissatisfaction into more severe conditions, such as eating disorders, BDD, pathological exercise, and/or depression.

Introduction

While concerns about one’s appearance are a common human experience, for some individuals, these concerns escalate into a significant preoccupation that disrupts their daily functioning, potentially indicating body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) [1], which is defined as a severe, chronic, and debilitating mental disorder characterized by a persistent and pathological preoccupation with imagined perceived defects in physical appearance or weight [2]. The incidence of BDD has risen in recent years, particularly among young women, largely attributed to societal pressures that emphasize and idealize thinness [3]. BDD typically emerges during mid-to-late adolescence, specifically between the ages of 14 and 18 [4]. Research consistently indicates a considerable prevalence of BDD among youth, particularly females [5, 6]. Reported figures for BDD range from 12.5% [5], while the rate of body image dissatisfaction climbs as high as 36.7% [7]. Consequently, the widespread occurrence of BDD has become a significant global public health concern [8]. In Iran, a study on the prevalence of BDD among adolescents and young adults has revealed that at least one in three individuals reports BDD symptoms [9].

While perceived flaws centered on physical appearance can pertain to any body part, common areas of concern include the head, body hair, and facial features such as the nose, hair, and skin. Research suggests gender differences in specific areas of concern [10]. For example, men are more frequently preoccupied with their genitals, whereas women tend to focus on their skin, stomach, weight, and breasts. Furthermore, most individuals with BDD express concerns about multiple body areas, and some may even report a general sense of ugliness without being able to identify specific flaws [10]. Patients often spend considerable time daily ruminating about their appearance and may enhance or conceal perceived defects when attending social events. Individuals with BDD experience excessive self-consciousness, believing that others notice, judge, or comment on their perceived imperfections [9].

Conversely, a balanced perspective on physical appearance is generally associated with positive mental health, given its strong correlation with self-esteem, social acceptance, and overall quality of life. In initial social encounters, physical appearance often serves as the primary basis for forming immediate positive or negative assumptions about an individual’s personality and psychological attributes [11]. The widespread influences of mass media and increased opportunities for social comparison have intensified concerns regarding appearance and body shape. Consequently, there is a growing emphasis on physical appearance, leading to an expansion of body image concerns. This has become a significant preoccupation for many, particularly young people, who invest considerable time and resources in contemplating and altering their physical presentation.

Research by Goudarzi et al. [12] highlighted that an individual’s susceptibility to internalizing idealized images, engaging in social comparisons, and experiencing body dissatisfaction is influenced by a range of factors. While parental care and secure attachments can act as protective buffers against the negative effects of internalizing media ideals on body image, insufficient emotional support and care may be linked to difficulties in regulating anxiety and heightened self-doubt. These latter factors contribute to increased internalization and social comparison. Furthermore, etiological studies suggest that prolonged exposure to childhood trauma has ramifications beyond post-traumatic stress disorder, potentially impacting psychological self-regulation, interpersonal relationships, and self-perception, thereby predicting the development of BDD symptoms [13]. Experiences of abuse or neglect also can deprive children of essential love, belonging, and support from their primary caregivers, often leading them to internalize and adopt their parents’ negative perceptions [12]. It is also important to note that BDD is a complex psychiatric condition, likely resulting from the intricate interplay of psychological, social, biological, and genetic factors [14].

Traumatic childhood experiences, a broad category, encompass events like physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as a range of distressing and traumatic experiences resulting from accidental and natural life events and disasters, including the death of loved ones, divorce and separation of parents, etc [15]. Childhood maltreatment, occurred by a caregiver’s failure to meet a child’s basic needs, includes all forms of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect, which can occur individually or in combination. These experiences are significant predictors of lifelong physical and mental health outcomes, representing a major public health and social welfare concern. Their negative consequences span across various developmental stages and life domains. The long-term effects of such trauma can lead to physical, cognitive, psychological, behavioral, and social difficulties in adulthood [16].

There is a hypothesis suggesting that abusive experiences can lead to body dissatisfaction, intense body shame, and a distorted body image. Given that BDD involves a disturbance in body image, research into the connection between childhood maltreatment and the development of body image can be highly informative [17]. Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between levels of childhood trauma and abuse and later-life body image dissatisfaction, alongside a strong relationship between low self-esteem and body image dissatisfaction [18]. Specifically, it has been theorized that emotional abuse may contribute to internalized self-criticism in BDD, while physical abuse, particularly when directed at the body, may be more likely to play a role [19]. More precisely, childhood maltreatment may precipitate BDD symptoms through mechanisms such as altered social and emotional processing and stress-related biological changes [20]. These mechanisms include an increased perception of threat, cognitive biases related to threat, difficulties with emotion regulation, heightened emotional reactivity to threat, and neurodevelopmental changes in brain function and structure [21].

The attachment system is recognized as a natural facilitator of emotional regulation capacity [22]. This connection is crucial because, during their early years, children’s limited ability to regulate emotions depends significantly on the regulatory support provided through their attachment relationships to maintain physiological stability [23]. Essentially, a primary caregiver’s (such as a mother) capacity to comprehend and empathize with a child’s emotions fosters a secure and emotionally safe relationship. Conversely, early childhood trauma inflicted by close caregivers can disrupt the development of a secure attachment style, leading to a distorted attachment style and subsequent difficulties in recognizing and regulating emotions [23]. Consequently, individuals with secure attachments tend to exhibit better emotional regulation skills compared to those with insecure attachments [24]. While the connection between adult attachment styles and emotion regulation remains under-explored, particularly regarding the underlying mechanisms [25], existing literature suggests self-compassion as a crucial mediating factor [26].

Neff introduced the concept of self-compassion in 2003, positing that compassion directed inward is as vital as compassion extended to others. She defined self-compassion as treating oneself with the same care, kindness, and understanding typically offered to others, recognizing one’s experiences as an intrinsic part of the universal human condition [27]. According to Neff, self-compassion involves acknowledging and responding to one’s own suffering with kindness and without judgment, viewing personal failures and shortcomings as universal experiences common to all individuals [11]. This construct is characterized by three interconnected components: self-kindness (replacing self-judgment), common humanity (counteracting feelings of isolation), and mindfulness (preventing over-identification with negative emotions). The synergistic integration of these elements defines a self-compassionate individual [28].

Self-compassion is an adaptive form of self-communication that enables individuals to confront challenging life experiences actively and compassionately, without suppression or overwhelming emotional responses [29]. Neff and McGehee [30] propose that an individual’s relationship with themselves often mirrors their early interactions with primary caregivers. Consequently, individuals who experienced unpredictable parental responses may be more prone to self-criticism and self-rejection, leading to lower levels of self-compassion. This perspective is supported by several studies demonstrating a significant inverse relationship between insecure attachment and self-compassion, with individuals exhibiting insecure attachment reporting lower self-compassion than those with secure attachment [31]. In the context of BDD, the cognitive-behavioral model highlights a lack of self-compassion as a core cognitive pattern [32]. Specifically, individuals with BDD tend to selectively focus on minor perceived physical flaws, base their self-worth on appearance, react to these perceived imperfections with intense negative emotions, avoid social interactions, and engage in ritualistic behaviors (e.g., excessive mirror-checking) to neutralize unpleasant feelings [32].

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate a strong link between childhood maltreatment and reduced self-compassion, with higher levels of abuse correlating with lower self-compassion [33]. Individuals with a history of childhood abuse tend to exhibit diminished self-compassion and are more inclined towards self-blame [33]. For these individuals, self-criticism often serves as an ineffective coping mechanism, mistakenly aimed at fostering a sense of security, concealing perceived flaws, and evading experiences deemed shameful [34]. Conversely, substantial evidence indicates that cultivating self-care and compassion positively impacts an individual’s mental and psychological well-being [35]. Turk and Waller’s research [36] further supports the role of self-compassion as an adaptive emotion-regulation strategy in body image disorders, concluding that greater self-compassion predicts fewer body image concerns.

Childhood maltreatment and other traumatic experiences are prevalent and severe in individuals with BDD, and are concurrently linked to the severity of clinical symptoms. Consequently, adversity stemming from maladaptive family functioning during childhood may be particularly pertinent to individuals with BDD, potentially contributing to the social and emotional processing difficulties associated with the disorder [37, 38]. The quality of early relationships, particularly with parents and peers, significantly influences an individual’s mental representations of themselves and their interactions with others, thereby laying a foundation for the development of cognitive distortions and excessive concerns about body image [39]. Insecure early attachments, often resulting from a lack of emotional support, persistent criticism, or neglect, can foster negative self-perception, feelings of worthlessness, and distrust towards others. These negative predispositions can lead individuals to interpret information and experiences negatively, especially concerning physical appearance.

Traumatic childhood experiences can impact the development and function of specific brain regions, promote the formation of dysfunctional or pathogenic psychological interpretations and beliefs, and impede the development of adaptive emotion regulation strategies [40]. Such experiences may also contribute to the emergence of maladaptive schemas characterized by a negative view of self and others, thereby exacerbating cognitive distortions, emotion regulation difficulties, and interpersonal relationship challenges [41]. Furthermore, early maladaptive schemas are associated with low self-compassion, which mediates the relationship between these schemas and BDD symptoms [8]. Current cognitive and behavioral models of BDD etiology highlight a potential role of self-compassion deficits as a vulnerability factor [42].

In the context of BDD, Veale and Gilbert [43] propose that the perceived threat of a physical flaw activates the threat-detection system, triggering defensive emotions (e.g., shame, disgust) and behaviors, such as camouflaging perceived defects. They further suggest that self-compassion approaches, by activating the contentment, soothing, and affiliative-focused system, could offer a novel strategy to mitigate the perceived threat of a distorted body image experienced by BDD sufferers. Therefore, Veale and Gilbert [43] advocate for a self-compassion-focused approach to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for BDD [42]. However, empirical research on the role of childhood trauma and self-compassion in adolescents’ body dysmorphic symptoms remains limited.

Given the aforementioned descriptions, this study investigates the complex interplay between childhood trauma, self-compassion, and BDD symptoms. Recognizing that understanding the root causes of BDD is crucial for effective intervention, the research employs a modeling framework to examine self-compassion’s multifaceted role as an explanatory mechanism linking childhood trauma to BDD symptoms. Specifically, the study addresses the question: Does self-compassion mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms? To this end, its aims are twofold: (a) to analyze the relationships among childhood trauma, self-compassion, and BDD symptoms, and (b) to explore the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms. The central hypothesis posits that self-compassion would mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms.

Methods

Participants and procedure

This cross-sectional study investigated girls aged 16 to 24 residing in the cities of Meybod and Ardakan during the 2023–2024 academic year. Based on the of the number of questionnaires’ items used in the present study (i.e., 52 items) and a typical requirement of 3 to 10 participants per item, the appropriate sample size ranged from 156 to 520 individuals. However, in accordance with Kline’s recommendation of a minimum of 200 participants for structural equation modeling (SEM) research, a convenience sample of 300 participants was ultimately chosen.

Participants for this study conducted over three to four months in 2023 following ethical approval and permissions from Meybod and Ardakan’s education departments, met specific inclusion criteria: informed consent and willingness to participate, age between 16 and 24 years, and no history of mental illness or psychiatric medication use. Exclusion criteria included unwillingness to cooperate or incomplete questionnaires. Before data collection, all participants provided informed consent; for those under 18, both the participant and their parents provided consent after receiving a comprehensive explanation of the research purpose, variables, and procedures. Participants were assured of confidentiality, anonymity (no identifying information was collected, and researchers were unaware of participants’ identities), and the freedom to withdraw at any stage. The questionnaire completion process and explanations were standardized across all schools and classes. Prior to data collection in schools and organizations, approval and permission were secured from relevant departments, and officials were thoroughly briefed on the research and its objectives. During questionnaire administration, a researcher was present to address any student queries.

Measures

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form (CTQ-SF). The CTQ-SF. developed by Bernstein et al. [44], is a 28-item self-report instrument used to assess various types of childhood trauma. It comprises five subscales: physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect, each measured by five items. The remaining three items are designed to identify individuals who may deny childhood problems. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Before scoring, items 2, 5, 7, 13, 19, 26, and 28 must be reverse-coded. Subscale scores range from 5 to 25, while the total questionnaire score ranges from 25 to 125. Higher scores indicate greater trauma. In the original study by Bernstein et al. [44], the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the subscales in adolescents ranged from 0.78 to 0.95, and its concurrent validity, when compared with therapists’ ratings of childhood trauma, ranged from 0.59 to 0.78. Additionally, the subscales demonstrated good test-retest reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.79 and 0.94, and their validity was confirmed through optimal factor analysis [31]. In Iran, Ebrahimi et al. [45] reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the five subscales ranging from 0.81 to 0.98. In the present study, the questionnaire’s overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.84.

The Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire (BDD-YBOCS). This scale, developed by Phillips et al. [46], is a 12-item self-report instrument designed to assess the severity of body image disturbance. This scale features a two-factor hierarchical structure encompassing obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors, complemented by two additional questions concerning insight and avoidance, collectively explaining 56% of the variance. Total scores range from 0 to 48, with a score exceeding 20 indicating a diagnostic criterion for BDD. The BDD-YBOCS has demonstrated robust reliability and validity in its original form [46]. Rabiei et al. [47] conducted the Iranian norming of the BDD-YBOCS, identifying two factors: obsessive-compulsive thoughts about appearance and the compulsion to control these thoughts, which together accounted for 66% of the variance. In the Iranian sample, the scale showed strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 for the total scale. Split-half and Guttman coefficients were 0.83 and 0.92, respectively, indicating its suitability for both diagnostic and therapeutic applications in Iran [47]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this questionnaire was calculated to be 0.80.

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). This tool developed by Neff and colleagues [48 [is a 12-item instrument that assesses self-compassion across three bipolar factors, yielding six subscales: self-kindness (items 2, 4) versus self-judgment (items 11, 12), mindfulness (items 3, 7) versus over-identification (items 1, 9), and common humanity (items 5, 10) versus isolation (items 6, 8). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (rarely) to 5 (almost always). Neff et al. [48 [reported an internal consistency of 0.86 for the total scale, with subscale reliability coefficients ranging from 0.54 to 0.75. The Iranian version of the SCS has demonstrated robust psychometric properties. For example, Azizi et al. [49] confirmed its six-factor structure through confirmatory factor analysis and reported strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.79 for self-kindness, 0.79 for self-judgment, 0.93 for common humanity, 0.90 for perceived isolation, 0.88 for mindfulness, and 0.88 for over-identification. Additionally, the Iranian SCS showed a significant positive correlation with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (r = 0.261, p < 0.05) and significant negative correlations with the Ruminative Response Scale (r = -0.363, p < 0.05), Beck Depression Inventory–II (r = -0.177, p < 0.05), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (r = -0.361, p < 0.05) [49]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this questionnaire was 0.78.

Statistical analysis

Data collected from research participants were analyzed using SPSS-26 and AMOS-24 software. The relationships between childhood trauma, self-compassion, and BDD symptoms were assessed using Pearson’s correlation analysis trough SPSS-26. The structural mediation modeling (SEM) using the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) was conducted to evaluate the mediating role of self-compassion in the link between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms in AMOS-24. In SEM, the model fit was assessed based on established criteria, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Parsimony Comparative Fit Index (PCFI). To further evaluation of indirect effect, 95% confidence interval using conducting bootstrapping with 5000 re-samples was also ran through AMOS-24. If 95% confidence interval does not cover zero, significance of indirect effect is conformed.

To establish the foundational assumptions for SEM, several preliminary analyses were conducted. Data normality was evaluated through the calculation of skewness and kurtosis. Pearson’s correlation and regression analyses were performed to investigate inter-variable relationships. The presence of multicollinearity was assessed using tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) statistics, while the Mahalanobis distance index was employed to identify and address multivariate outliers.

Results

This section outlines the demographic characteristics of the 300 female participants, who ranged in age from 16 to 24 years. The average age of participants was 19.65 years (SD = 3.29). In terms of educational background, the majority of participants, 193 (64.3%), reported having a high school degree. A smaller proportion, 63 (21%), held a bachelor’s degree, while 44 (14.7%) had attained a master’s degree. For the preliminary analysis of the research data, we examined the descriptive statistics of the variables, including mean and SD of variables presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study variables (n = 300)

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Maximum and minimum | Skewness | Kurtosis | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood trauma | 39.08 ± 11.87 | 28–90 | 1.165 | 0.909 | 0.695 | 1.439 |

| Self-compassion | 38.76 ± 8.93 | 11–58 | − 0.347 | -0.474 | 0.695 | 1.439 |

| BDD | 15.31 ± 6.96 | 2–43 | 1.269 | 1.127 | - | - |

Note. BDD = body dysmorphic disorder; VIF = variance inflation factor

This table presents the descriptive statistics for the studied variables, including means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, tolerance, VIF, and ranges, for a sample size of 300

The mediating role of self-compassion in the link between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms was assessed using SEM. However, before running SEM, to ensure the appropriateness of the SEM analysis, several critical assumptions were rigorously assessed. Univariate normality was established, as evidenced by skewness and kurtosis values falling within Kline’s [50] recommended range of ± 2. Furthermore, multivariate normality was confirmed, with both the standardized coefficient of variation and critical level remaining below the acceptable threshold of 5. The absence of multivariate outliers was corroborated by the Mahalanobis distance index. Moreover, the absence of problematic multicollinearity was verified through tolerance values exceeding 0.1 and VIF values remaining below 5 (see Table 1 for all relevant statistics).

The Pearson’s correlation and regression analyses revealed a significant relationship between the variables within the SEM (Table 2). Specifically, a significant negative correlation was observed between childhood trauma and self-compassion (r = -0.552, p < 0.01), indicating that higher levels of childhood trauma are associated with lower self-compassion. Conversely, a significant positive relationship was found between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms (r = 0.612, p < 0.01), suggesting that increased childhood trauma is linked to a higher risk of developing BDD. Furthermore, there was a significant negative correlation between self-compassion and BDD symptoms (r = -0.695, p < 0.01), implying that low self-compassion may increase the occurrence of BDD symptoms. Additionally, Table 3 presents the results of regression analyses to test whether there are significant relationship between childhood trauma and self-compassion, as well as between childhood trauma and self-compassion with BDD symptoms in predicting BDD symptoms. The results indicated that childhood trauma significantly predicted self-compassion (R2 = 0.305, F = 130.698, β=−0.552, 95% CI [− 0.487,−0.344], p < 0.001). Furthermore, childhood trauma (β = 0.328, 95% CI [0.139,0.245], p < 0.001) and self-compassion (β=−0.514, 95% CI [− 0.472,−0.330], p < 0.001) together significantly predicted BBD symptoms (R2 = 0.558, F = 187.378). Therefore, there were significant relationships between variables, allowing conducting SEM.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix for the study’s variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1- Childhood trauma | - | ||

| 2- Self-compassion | -0.552* | - | |

| 3- BDD | 0.612* | -0.695* | - |

Note. BDD = body dysmorphic disorder. * p < 0.01

This table presents the correlations among childhood trauma, self-compassion, and body dysmorphic disorder, illustrating both the strength and direction of the relationships between these variables

Table 3.

Regression-based results for relationships observed among the research variables

| Predictors | Criterion variable | R | R 2 | F | β | t | S.E | 95% CI (Upper bound/Lower bound) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood trauma | Self-compassion | 0.552 | 0.305 | 130.698 | -0.552 | -11.432 | 0.036 | (-0.487/-0.344) | 0.001* |

| Childhood trauma | BDD | 0.747 | 0.558 | 187.378 | 0.328 | 7.080 | 0.027 | (0.139/0.245) | 0.001* |

| Self-compassion | -0.514 | -11.113 | 0.036 | (-0472/-0.330) | 0.001* |

Note. BDD = body dysmorphic disorder; CI = confidence interval. * p < 0.001

This table presents the relationships between the variables, illustrating the strength and statistical significance of their liner relationships

The results of SEM model are presented in Fig. 1. In this analysis, the research model also underwent a measurement model examination. During this process, items with a factor loading below 0.3 were removed. Specifically, item 8 was eliminated from the BDD variable. The final model, presented in Table 4, demonstrated a good fit to the data. Specifically, the Chi-square/df = 1.259, RMSEA = 0.029, CFI = 0.935, GFI = 0.909, IFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.930, PCFI = 0.859, Pclose = 1, and Hoelter = 268 collectively suggested that the proposed model accurately describes the data and aligns with its structure. In the model, childhood trauma had a positive significant link to BDD symptoms (β = 0.32, p < 0.001), as well as a negative significant association with self-compassion (β=−0.70, p < 0.001), which, in turn was negatively and significantly associated with BDD symptoms (β=−0.76, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The model accounted for 55.8% of the variance in BDD symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Structural equation modeling of research variable relationships

Table 4.

Model fit indices for the model and the measurements used in this research

| Fit indices | RMSEA | X2/DF | PCLOSE | CFI | GFI | IFI | TLI | PCFI | Helter index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model values | 0.029 | 1.259 | 1 | 0.935 | 0.909 | 0.937 | 0.930 | 0.859 | 268 |

| structural model values | 0.029 | 1.259 | 1 | 0.935 | 0.909 | 0.937 | 0.930 | 0.859 | 268 |

| The desired amount | < 0.08 | < 3 | > 0.05 | > 0.9 | > 0.9 | > 0.9 | > 0.9 | > 0.5 | > 75 |

Note. RMSEA = Root mean squared error of approximation; X2/df = Normed Chi-square; PCLOSE = P-value of the null hypothesis; GFI = Goodness-of-Fit Index, CFI = Comparative Fit Index; IFI = Incremental Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; PCFI = Prudent Comparative Index; Helter index = Productivity index

Table 5 presents the results of a 95% confidence interval derived from a bootstrapping analysis with 5000 resamples, conducted to evaluate the indirect effect of childhood trauma on BDD symptoms, as mediated by self-compassion. In addition, the mediating role of self-compassion was further examined by calculating the Sobel test presented in this table. The findings demonstrated a significant indirect effect of childhood trauma on BDD symptoms mediated by self-compassion (β = 0.538, p < 0.001). The Sobel test results further support this mediating role (Table 5), indicating that heightened childhood trauma may diminish an individual’s self-compassion, consequently increasing their vulnerability to BDD symptoms both directly and indirectly.

Table 5.

Indirect effect of childhood trauma on BDD symptoms mediated by self-compassion

| Independent variable | Mediating variable | Dependent variable | Indirect effect | Lower bound | Upper bound | p | Sobel mediation test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sobel statistic | P | |||||||

| Childhood trauma | Self-compassion | BDD | 0.538 | 0.380 | 0.794 | 0.001* | 5.72 | 0.001* |

Note. BDD = body dysmorphic disorder. * p < 0.001

This table presents the indirect effect of childhood trauma on BDD symptoms, as mediated by self-compassion. These results were obtained using bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to compute a 95% confidence interval. It presents the path coefficients, standard errors, and p-values for these indirect effects, thereby highlighting the mediation effects within the proposed model.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate a model assessing BDD symptoms, focusing on the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms. The findings revealed that self-compassion significantly mediated this relationship, aligning with the results of previous studies [51, 52].

This study’s primary finding established a direct correlation between childhood trauma and BDD symptoms, indicating that early traumatic experiences substantially heighten the risk of developing BDD in adulthood. This relationship can be attributed to the profound impact of childhood trauma on body image dissatisfaction, which often reflects the hostile internalization experienced by survivors. Essentially, BDD is characterized by an excessive preoccupation with perceived or exaggerated flaws in one’s physical appearance.

An individual’s comfort with their physique is deeply intertwined with their awareness of their own thoughts, values, and beliefs about their body. This is particularly salient given that the body is constantly scrutinized in social interactions and subjected to external judgments [53]. From a cognitive-behavioral perspective, individuals with BDD demonstrate biased information processing and harbor distorted and negative beliefs about their appearance and body image, leading them to over-attend to information that emphasizes perceived imperfections. This cognitive bias subsequently forms and reinforces negative and distorted beliefs—or cognitive errors—concerning physical appearance and beauty, which are central to the core features of BDD [54]. Furthermore, childhood trauma frequently results in heightened self-focused attention, often rooted in feelings of worthlessness, shame, and inadequacy. This excessive self-observation commonly manifests as a preoccupation with the body [55]. It’s theorized that experiences of abuse and trauma intensify these negative emotions and foster a profound sense of alienation toward one’s body, ultimately instilling feelings of fear, anxiety, and self-hatred.

Another key finding of this study is the indirect relationship between self-compassion and BDD symptoms, This signifies that as much as self-compassion increases, the risk of BDD decreases, and vice versa, corroborating research by Tadayin [56] and Mirzaei [57], which explored the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapies in reducing shame in childhood trauma survivors, mitigating negative thoughts, and improving adult intimate relationships. From a cognitive-behavioral standpoint, self-compassion fosters a positive and supportive relationship with oneself, aiming to reduce negative thoughts and enhance feelings of kindness and empathy. This approach focuses on modifying negative attitudes and thought patterns, guiding individuals toward greater self-acceptance and self-kindness through awareness, cognitive restructuring, and behavioral exercises.

The multi-component model of self-compassion further elucidates this finding. Regarding self-kindness, individuals with BDD often hold derogatory self-views by excessively focusing on real or imagined weaknesses and constantly engaging in negative self-judgment, demonstrating a lack of self-love. Concerning common humanity, those with BDD tend to view themselves in isolation, failing to recognize their shared human fallibility. They adopt a black-or-white perspective—perfect or worthless—leading to persistent self-dissatisfaction and an inability to acknowledge that flaws, pain, and discomfort are universal human experiences. Mindfulness, the third component, also appears weak in individuals with BDD. They tend to take every thought or feeling seriously, struggling to discern which thoughts warrant attention, thus becoming consumed by negative emotions. Therefore, when confronting unpleasant aspects of oneself, self-compassion is expected to mitigate harsh judgments. By creating a non-reactive and non-judgmental environment, it enhances an individual’s capacity to respond to environmental threats or stressors, such as external pressures [58, 59]. Self-compassion can serve as a protective factor against body image disorders. When appearance concerns arise, self-compassion allows individuals to accept their flaws and consider alternative perspectives by activating a soothing regulatory system. This enables them to replace BDD-characteristic preoccupation with appearance—marked by negative emotions and maladaptive cognitions and behaviors—with self-love and affection [60]. Generally, individuals with low self-compassion exhibit harsh self-judgments, irrespective of their body size, shape, or societal ideals, lacking self-acceptance and failing to embrace their bodies as they are [52].

These findings align with previous research, such as that by Rogers et al. [61], who found that positive facets of self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness) is correlated with lower body appearance concerns in adolescent girls. From a cognitive-behavioral perspective, these results suggest that individuals with more negative self-attributions and self-evaluations are more prone to BDD-related symptoms, whereas those with fewer cognitive errors and negative self-evaluations are less susceptible [62]. Additionally, this study expands existing literature on the link between self-compassion and psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety, body image concerns), indicating that lower self-compassion plays a role in the development of these disorders.

Finally, the present study highlighted the role of self-compassion in linking childhood trauma to BDD symptoms. Emotional abuse appears to correlate with self-criticism in individuals with BDD, while physical or sexual abuse is linked to body-focused shame [63]. However, the relationship between trauma and BDD symptoms is not a simple linear one, as our findings suggest. Instead, trauma contributed to BDD symptoms through mechanisms involving altered cognitive and emotional processing, such as self-compassion. Specifically, a lack of childhood care, emotional support, and acceptance is associated with deficits in the core components of self-compassion: self-kindness versus self-judgment, a sense of common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification with experience. Although these components are often impaired during traumatic childhood experiences, self-compassion may help reduce the overall emotional suffering of traumatized individuals by moderating the unpleasant emotions and psychological distress resulting from those experiences [64]. Self-compassion can foster empathy and kindness towards oneself, increase mindfulness of events and feelings, and consequently enhance an individual’s mental capacity. These factors collectively predict a reduction in psychological disorders, including BDD.

Implications of the study

This research significantly advances our theoretical understanding by proposing that self-compassion is not merely a coping mechanism, but a pivotal mediating factor in the manifestation of BDD following early adverse experiences. The findings suggest that childhood trauma may contribute to BDD symptoms by undermining an individual’s capacity for self-compassion. This offers a more nuanced model of the intricate pathways from trauma to psychopathology, emphasizing the critical role of internal emotional regulation processes.

From a clinical perspective, these results highlight the substantial potential of self-compassion-focused interventions for both the prevention and treatment of BDD, especially in individuals with a history of childhood trauma. Therapists could effectively incorporate techniques aimed at fostering self-kindness, recognizing common humanity, and promoting mindfulness into their therapeutic protocols. Practical applications might include exercises such as compassionate self-talk, mindful body scans centered on acceptance, and strategies designed to diminish self-criticism. Furthermore, identifying reduced levels of self-compassion in individuals with a history of trauma could serve as an early indicator of heightened risk for developing BDD, thereby enabling the implementation of targeted preventative interventions. These approaches, by counteracting the negative self-focus and cognitive distortions related to body image, complement other beneficial strategies like addressing attachment-related wounds and enhancing emotion regulation through emotion-focused therapies, all of which contribute to the multifaceted treatment of BDD.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations that warrant cautious interpretation of its findings. A primary concern is the potential for recall bias regarding participants’ negative childhood experiences. Traumatic memories can be repressed, making accurate recollection difficult. Additionally, the convenience sampling method and the non-clinical population (high school and college students in Ardakan and Meybod) limit the generalizability of the results, as factors like peer pressure and media influence weren’t controlled for. The study’s cross-sectional design further restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between variables. Future research should address these limitations. Longitudinal studies are recommended to provide stronger insights into causal pathways, observe the effects of time and age on the symptoms of the disorder, and track changes in self-compassion across different life stages. This would enhance the effectiveness of future interventions. Furthermore, future studies should include both men and women to assess the impact of gender on the studied model. Finally, exploring methods beyond self-report data could help mitigate recall bias and other situational or memory-related errors that might introduce variability into the results.

Future research would benefit from incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews, alongside questionnaires to better address potential limitations, although the substantial sample size in this study likely mitigated some errors. Additionally, socio-demographic factors, including race/ethnicity and specific cultural influences of Meybod and Ardakan, were not part of the main analyses and warrant consideration in future investigations. To enhance the generalizability of findings, subsequent studies should employ diverse methodologies, integrate other influential variables, and include both male and female participants.

Conclusion

Young people are a vital demographic, and their well-being is crucial for a nation’s future. Yet, many face significant interpersonal and familial challenges, such as childhood maltreatment, which can lead to considerable psychological distress. These adverse experiences are linked to various psychological disorders, including BDD, ultimately harming mental health and quality of life. This study revealed that childhood trauma was associated with lower levels of self-compassion, and self-compassion was significantly and negatively related to BDD symptoms. Specifically, a history of childhood trauma was indirectly linked to BDD symptoms while reduced self-compassion mediated this link.

Notably, it is also important to consider the complex relationship between body image and culture, particularly in Iran. Here, dominant cultural norms, shaped by tradition, religion, and history, profoundly influence women’s perceptions of beauty and body image, often leading to significant concerns, especially among female students. The hijab, a prominent cultural symbol, plays a notable role in shaping these concerns; while seen as protection and privacy, it can also subtly foster beauty competition in private settings. Social pressures for a slim physique and flawless facial features often amplified by media and advertising, frequently clash with cultural ideals of modesty and innocence. This conflict can induce guilt, shame, and body dissatisfaction among female students. Furthermore, traditional gender roles and familial expectations further complicate body image perceptions. Thus, body image concerns among Iranian female students are shaped by a complex interplay of cultural norms and societal expectations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who helped us in conducting this research.

Abbreviations

- CTQ

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

Author contributions

M.K: Conceptualization, investigation, resources, project administration, writing-original draft preparation, review and editing, reviewed and approved the final draft, visualization, and validation. A. Ch: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, software, supervision, interpreted the data and drafted the results section resources, reviewed, interpreted the data and drafted the results section, and approved the final draft. A.M: Conceptualization, investigation, Supervision, reviewed and approved the final draft.

Funding

The present study was accomplished without any outside financial support. No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Data availability

The data set is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol, including all methodologies, received approval from the ethics committee of Yazd University (IR.YAZD.REC.1403.041), Yazd, Iran, and adhered to all relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were assured of their anonymity and data confidentiality. Participants had the autonomy to determine the time, place, and duration of their interviews and were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without penalty.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained online from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Soltanizadeh M. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on obsessions-compulsions in Girl adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder. Shenakht J Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;2(4):1–0. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokhtari asl Ghareh M. Sociological study of eating disorders and its related factors. ]Master’s thesis[. Tabriz University, 2012.

- 3.Alizadeh NA. Evaluation and comparison of eating disorders in elite Iranian wrestlers. ]Master’s thesis[. Tabriz University, 2011.

- 4.Egan SJ, Wade TD, Shafran R. The transdiagnostic process of perfectionism. Revista De Psicopatol Psicología Clín. 2012;17(3):279–94. 10.5944/rppc.17.num.3.2012.11844. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam MM, Basak N, Shahjalal M, Nabi MH, Samad N, Mishu SM, Mazumder S, Basak S, Zaman S, Hawlader MD. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) symptomatology among undergraduate university students of Bangladesh. J Affect Disord. 2022;314:333–40. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krebs G, Clark BR, Ford TJ, Stringaris A. Epidemiology of body dysmorphic disorder and appearance preoccupation in youth: prevalence, comorbidity and psychosocial impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2025;64(1):30–40. 10.31234/osf.io/zmd2h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alharballeh S, Dodeen H. Prevalence of body image dissatisfaction among youth in the united Arab emirates: gender, age, and body mass index differences. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(2):1317–26. 10.1007/s12144-021-01551-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazemi Frooshani Z, Mirdricvand F, Ghazanfari F. Designing and testing a model of the antecedents of eating disorders symptoms in female students of Isfahan university in 2017: A descriptive study. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2019;18(4):377–90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saadatmand E, Mahmoud Alilou M, Esmaeilpour K, Hashemi T. Investigating the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder mediated by self-compassion. IJPN. 2022;10(1):64–75. http://ijpn.ir/article-1-1979-en.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohajerin B, Bakhtiyar M, Olesnycky OS, Dolatshahi B, Motabi F. Application of a transdiagnostic treatment for emotional disorders to body dysmorphic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:637–44. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghavi Z. The relationship between self-compassion and body ugliness symptoms in women asking for beauty shopping: the mediating role of cognitive fusion related to body image. ]Master’s thesis[. Al-Zahra University, 2020.

- 12.Goodarzi M, Noori M, Aslzakerlighvan M, Abasi I. The relationship between childhood traumas with social appearance anxiety and symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder: the mediating role of Sociocultural attitudes toward appearance. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2022;16(1). 10.5812/ijpbs.113064.

- 13.Morton C, Mooney TA, Lozano LL, Adams EA, Makriyianis HM, Liss M. Psychological inflexibility moderates the relationship between thin-ideal internalization and disordered eating. Eat Behav. 2020;36:101345. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.101345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteleone AM, Tzischinsky O, Cascino G, Alon S, Pellegrino F, Ruzzi V, Latzer Y. The connection between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder psychopathology: a network analysis study in people with bulimia nervosa and with binge eating disorder. Eating and Weight Disorders-studies on Anorexia, Bulimia, and Obesity. 2022; 1: 1–9. 10.1007/s40519-021-01169-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization. Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire. Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). 2018; 245– 58.

- 16.Mohammad Ali hodratollahifard G, Chinaveh, Mahbobeh, Sajad Aminimanesh. Modeling of the symptom manifestation of personality disorders in nursing students and temporary nurses within the human research project based on childhood trauma and the mediating role of emotional cognitive regulation. Iran J Nurs (IJN). 2020;33(123):84–107. 10.29252/ijn.33.123.84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arabaci LB, Arslan AB, Dagli DA, Tas G. The relationship between university students’ childhood traumas and their body image coping strategies as well as eating attitudes. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35(1):66–72. 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamidinejad N, Dolatshahi B, bagheri F. Investigating the relationship between perfectionism and childhood trauma with disordered eating behaviors with the mediating role of body image dissatisfaction. Health Psychol. 2023;12(46):77–92. 10.30473/hpj.2023.64030.5546. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veale D, Neziroglu F. Body dysmorphic disorder: A treatment manual. Wiley; 2010. Feb 4.

- 20.McLaughlin KA, Colich NL, Rodman AM, Weissman DG. Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: a transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–1. 10.1186/s12916-020-01561-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaul D, Smith CC, Stevens J, Fröhlich AS, Binder EB, Mechawar N, Schwab SG, Matosin N. Severe childhood and adulthood stress associates with neocortical layer-specific reductions of mature spines in psychiatric disorders. Neurobiol Stress. 2020;13:100270. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;25:6–10. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fonagy P, Bateman AW. Adversity, attachment, and mentalizing. Compr Psychiatr. 2016;64:59–66. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozeren GS. The correlation between emotion regulation and attachment styles in undergraduates. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58(2):482–90. 10.1111/ppc.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clear SJ, Gardner AA, Webb HJ, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Common and distinct correlates of depression, anxiety, and aggression: attachment and emotion regulation of sadness and anger. J Adult Dev. 2020;27(3):181–91. 10.1007/s10804-019-09333-0.

- 26.Doorley JD, Kashdan TB, Weppner CH, Glass CR. The effects of self-compassion on daily emotion regulation and performance rebound among college athletes: comparisons with confidence, grit, and hope. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2022;58:102081. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102081. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(3):223–50. 10.1080/15298860390209035.

- 28.Neff K. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):85–101. 10.1080/15298860309032. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neff K. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):85–101. 10.1080/15298860309032. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neff KD, McGehee P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self Identity. 2010;9(3):225–40. 10.1080/15298860902979307. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huynh T, Phillips E, Brock RL. Self-compassion mediates the link between attachment security and intimate relationship quality for couples navigating pregnancy. Fam Process. 2022;61(1):294–311. 10.1111/famp.12692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prazeres AM, Nascimento AL, Fontenelle LF. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a review of its efficacy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;307–16. 10.2147/NDT.S41074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Tao J, He K, Xu J. The mediating effect of self-compassion on the relationship between childhood maltreatment and depression. J Affect Disord. 2021;291:288–93. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahar B, Doron G, Szepsenwol O. Childhood maltreatment, shame-proneness and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder: A sequential mediational model. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015;22(6):570–9. 10.1002/cpp.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harouni B, Khoshakhlagh H. The mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between self-concept and body image with social anxiety in female students of Isfahan university of technology. Women’s Interdisciplinary Res. 2022;10(4):67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turk F, Waller G. Is self-compassion relevant to the pathology and treatment of eating and body image concerns? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;79:101856. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malcolm A, Pikoos TD, Grace SA, Castle DJ, Rossell SL. Childhood maltreatment and trauma is common and severe in body dysmorphic disorder. Compr Psychiatr. 2021;109:152256. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monzani B, Luxton R, Jassi A, Krebs G. Adverse childhood experiences among adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder: frequency and clinical correlates. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2024;31(4):e3028. 10.1002/cpp.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Longobardi C, Badenes-Ribera L, Fabris MA. Adverse childhood experiences and body dysmorphic symptoms: A meta-analysis. Body Image. 2022;40:267–84. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheffler JL, Stanley I, Sachs-Ericsson N. ACEs and mental health outcomes. In Adverse Childhood Experiences 2020 Jan 1 (pp. 47–69). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-816065-7.00004-5

- 41.Pilkington PD, Bishop A, Younan R. Adverse childhood experiences and early maladaptive schemas in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2021;28(3):569–84. 10.1002/cpp.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen LM, Roberts C, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Farrell LJ. Exploring the relationship between self-compassion and body dysmorphic symptoms in adolescents. J Obsessive-Compulsive Relat Disorders. 2020;25:100535. 10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100535. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veale D, Gilbert P. Body dysmorphic disorder: the functional and evolutionary context in phenomenology and a compassionate Mind. J Obsessive-Compulsive Relat Disorders. 2014;3(2):150–60. 10.1016/j.jocrd.2013.11.005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(2):169–90. 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebrahimi H, Dejkam M, Seghatoleslam T. Childhood traumas and suicide attempt in adulthood. IJPCP. 2014;19(4):275–82. http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2090-fa.html. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, Aronowitz BR. A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):17. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-03978-003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rabiee M, Khorramdel K, Kalantari M, Molavi H. Factor structure, validity and reliability of the modified yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale for body dysmorphic disorder in students. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2010;15(4):343–50. http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-888-en.html. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neff KD, Dahm KA. Self-compassion: what it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness. Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation. 121– 37; 2015.

- 49.Azizi A, Mohammadkhani P, Foroughi AA, Lotfi S, Bahramkhani M. The validity and reliability of the Iranian version of the Self-Compassion scale. PCP. 2013;1(3):149–55. http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-83-en.html. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford; 2023 May. p. 24.

- 51.Lathren CR, Rao SS, Park J, Bluth K. Self-compassion and current close interpersonal relationships: A scoping literature review. Mindfulness. 2021;12:1078–93. 10.1007/s12671-020-01566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghabel Z, Shafiee Tabar M, Bahrami A. Self-compassion and cognitive flexibility in people with body dysmorphic disorder syndrome. Shenakht J Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;10(2):67–79. 10.32598/shenakht.10.2.67. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nigar A, Naqvi I. Body dissatisfaction, perfectionism, and media exposure among adolescents. Pakistan J Psychol Res. 2019;34(1):57–77. 10.33824/PJPR.2019.34.1.4. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nourizadeh Mirabadi M, Hosseinzadeh Taghvaei M, Moloodi R, Sodagar S, Bahrami Hidaji M. The efficacy of schema therapy on coping styles and body image concerns in obese people with binge-eating disorder: A single subject study. J Psychol Sci. 2023;21(120):2501–18. 10.52547/JPS.21.120.2501. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Firoozi M. Post-traumatic growth in response to occupational stress among firefighters in iran: A qualitative research. Int J Occup Hygiene. 2019;11(1):9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tadayon P. Developing a structural model to explain suicidal thoughts based on childhood trauma with the mediating role of self-compassion and shame in women of Ilam city ]Master’s thesis in general psychology [. Bu Ali Sina University, 2021.

- 57.Mirzaei F, Berimani S, Zare F, Farahani S. The structural model of the relationship between childhood trauma and sexual intimacy with the mediating role of self-compassion in married women. Appl Res Behav Sci. 2023;14(54):50–69. http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2398-en.html. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C. Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: implications for eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2013;14(2):207–10. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wheeler SM, Williams L, Beauchesne P, Dupras TL. Shattered lives and broken childhoods: evidence of physical child abuse in ancient Egypt. Int J Paleopathol. 2013;3(2):71–82. 10.1016/j.ijpp.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gilbert P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. Br J Clin Psychol. 2014;53(1):6–41. 10.1111/bjc.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodgers RF, Franko DL, Donovan E, Cousineau T, Yates K, McGowan K, Cook E, Lowy AS. Body image in emerging adults: the protective role of self-compassion. Body Image. 2017;22:148–55. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gilbert P, McEwan K, Matos M, Rivis A. Fears of compassion: development of three self-report measures. Psychol Psychotherapy: Theory Res Pract. 2011;84(3):239–55. 10.1348/147608310x526511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kopera M, Zaorska J, Trucco EM, Suszek H, Kobyliński P, Zucker RA, Nowakowska M, Wojnar M, Jakubczyk A. Childhood trauma, alexithymia, and mental States recognition among individuals with alcohol use disorder and healthy controls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108301. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fanimohammadabady M, Karami S, Shahheydari A, Kamkar M, Alexithymia E, Avoidance. Self-Compassion, Mindfulness-Based cognitive therapy. IJPN. 2023;11(4):95–107. http://ijpn.ir/article-1-2193-en.html. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data set is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.