Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal pain is common among nurses and can lead to absenteeism, reduced productivity and impaired physical and mental health. Long-term pain may develop into chronic pain, which is a more serious and longer-lasting condition that will cause further harm to nurses’ health. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain and its associated factors among nurses in tertiary hospitals in China.

Methods

This was a multicentre cross-sectional study of 147,832 nurses from 67 tertiary hospitals in China between December 2023 and January 2024, using cluster sampling and online methods. This study was a secondary analysis of the Nurses’ Mental Health Study. The variables included sociodemographic information (sex, age, ethnicity, etc.), work-related information (professional title, years of working, department, etc.), and chronic pain characteristics (presence of chronic pain and site of pain). The study followed the STROBE guidelines. Statistical analyses included descriptive, chi-square test and binary logistic regression.

Results

The prevalence of chronic pain among the participants was 8.2%, with the most common sites of pain being the low back (55.8%), neck and shoulder (40.0%), and head (37.6%). Factors associated with chronic pain in nurses included sex, age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, body mass index, weekly working hours, years of working, night shift, and exercise habit. Additionally, we analysed subgroups by different groups of sex, age, type of work, and night shifts. After comparing all binary logistic regression analyses, it was found that age > 40 years [odds ratio (OR) = 3.01], marital status (separated, widowed, or divorced) [OR = 1.64], body mass index ≥ 24 [OR = 1.27], working over 48 h per week [OR = 1.32], and no exercise habits [OR = 1.21] were stable risk factors for chronic pain in the nurse population.

Conclusion

Nurses’ occupational health is vital for the quality and safety of patient care. This study underscores the need for targeted interventions (e.g., ergonomics training and education, work environment enhancement, shift optimization, healthy lifestyle promotion) to reduce chronic pain in nurses. Our findings may help provide a foundation for the prevention and management of chronic pain in nurses.

Clinical trial registration number

Not applicable. This study was not a clinical trial.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-025-03605-9.

Keywords: Nurses, Occupational health, Chronic pain, Prevalence, Risk factor

Background

Nurses are one of the most vulnerable professions to musculoskeletal pain due to their physically demanding clinical work which involves prolonged standing, walking, heavy lifting (e.g., carrying patients, medical equipment), and repetitive motions. Prolonged fixed postures can lead to overloaded contraction of small motor units, causing a buildup of metabolites in the muscle that stimulate pain receptors to trigger pain [1]. Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMSDs) are a group of muscle, nerve, or joint disorders caused by repetitive motions, poor posture, or overloading, which primarily manifest as pain and discomfort [2]. According to the 2022 Statistical Office of the United States Department of Labor report, nursing staff have the highest prevalence of occupational musculoskeletal pain of any profession [3]. A meta-analysis that included 15 countries showed that the combined prevalence of WMSDs among nurses was as high as 77.2% [4]. Studies have shown that musculoskeletal pain affects the physical and mental health of nurses, which may result in absenteeism [5], stress, poor sleep [6], reduced quality of life [7], early retirement, and even permanent disability [8]. Notably, prolonged pain may accelerate the transition from acute to chronic pain. Peripheral and central sensitization play a key role in this transition [9]. During the acute injury period, the site of injury releases inflammatory mediators, such as nerve growth factor, prostaglandin E2, and proinflammatory cytokines, which trigger pain signaling through stimulation of injury receptors in peripheral nerve endings, leading to peripheral sensitization. And prolonged input of pain signals causes plasticity changes in neurons in the spinal cord and brain, which enhances the transmission and amplification of pain signals, parameterizing central sensitization and causing pain to persist in the absence of significant peripheral stimulation [10]. Chronic pain (CP) is a common healthcare issue worldwide, defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “pain that persists or recurs for more than three months” [11]. It is a more severe and longer lasting condition that can significantly impact the health of nurses. Therefore, it is particularly important to pay attention to CP to maintain nurses’ occupational health.

CP affects between one third and one half of the global population and imposes an enormous burden on patients and their families [12–14]. However, existing research predominantly focuses on the general population, leaving a notable gap in studies specifically targeting the nursing profession. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the prevalence of CP is typically higher among females [15]. Given that the nursing profession is predominantly female, this suggests that they are at higher risk of pain-related problems. To our knowledge, only two studies from Iran have explored CP among nurses: one investigation involving 639 registered nurses revealed a striking prevalence of 64.8%, and identified that older age, female status, and type of formal or corporative employment were associated factors [16]; another study on nursing students reported a 30.2% prevalence rate [17]. Although risk factors for CP in the general population, such as sex, age, economic status, and physical activity, have been extensively studied, the impact of nursing-specific occupational exposures - including high workloads, prolonged static postures, and frequent night shifts - on development of CP remains poorly understood.

In China, there are over 5.2 million registered nurses, more than 8 billion outpatient visits per year, and the national utilization rate of hospital beds exceeding 70%, imposing substantial workloads on healthcare professionals [18]. Nurses in tertiary hospitals, in particular, face the challenge of caring for critically ill patients, demanding high-level professional skills. While studies have focused on CP among nurses, few large-scale epidemiologic studies have systematically examined the prevalence of CP and its association with demographic characteristics and work-related factors among nurses in tertiary hospitals in China, a high-volume, high-stress occupational group. Therefore, the objective of this research was to conduct a comprehensive, large-sample analysis of the prevalence of CP and its relationship with demographic and work-related factors in the professional group of nurses, providing a scientific basis for the development of CP prevention and management strategies for nurses.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive, quantitative, cross-sectional study was conducted.

Participant selection and setting

This study utilized baseline data from the Nurses’ Mental Health Study (NMHS), a nationwide multi-center prospective cohort study. The NMHS was designed to investigate the mental health status of nurses in tertiary hospitals in China and to explore their risk and protective factors. A cluster sample of nurses from 67 tertiary hospitals across 31 provinces was recruited. This study was a secondary analysis of the NMHS. Eligibility criteria for hospital selection were as follows: (1) general tertiary hospitals, (2) capability to manage a spectrum of diseases comparable to other tertiary hospitals within the province, (3) willing to participate in the NMHS study. The inclusion criteria for nurses were: (1) nurses’ age at least 18 years, (2) nurses have been registered and are on duty, (3) nurses are willing to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included: (1) intern nurses (nurses in preregistration or standardised training programmes); (2) nurses from other hospitals who are in short-term programmes of specialised certifications.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (LYF20230048). All nurses received informed consent forms, only those who agreed started the questionnaire and they had the right to choose to continue or withdraw from the study at any point in time.

Data collection

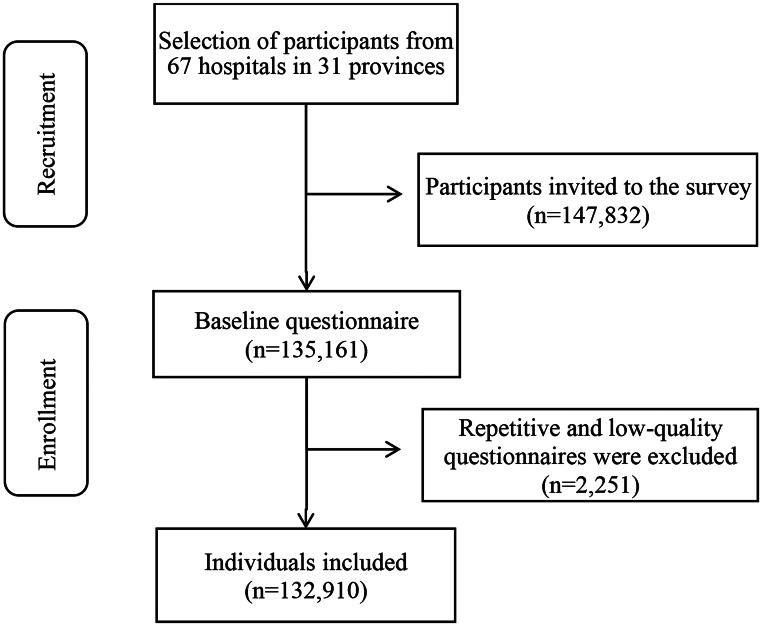

This study was conducted between December 2023 and January 2024 through the Questionnaire Star (https://www.wjx.cn/). Total 147,832 nurses were invited to participate in the survey and 135,161 online questionnaires were recovered, the final sample size for the baseline data included in the NMHS was 132,910, with an overall valid response rate of 89.91% (Fig. 1). Before analysis, data cleaning was performed by two independent researchers, which involved three steps. First, duplicate questionnaires were excluded. If the month of birth, telephone number, and the last four digits of the ID number were the same in both questionnaires, the first submitted questionnaire was retained. Next, outliers in continuous variables were removed, including values below P25-3IQR and above P75 + 3IQR [19]. Finally, checks for logical conflicts were performed. For example, if a participant reported working night shifts for longer years than his or her age, this was considered a logical conflict. Based on the identification method of invalid questionnaires [20], we regarded questionnaires with two or more logical conflicts as invalid and gave them exclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study participants

Measures

The NMHS online questionnaire was structured by all participating researchers based on the scoping review and qualitative research conducted previously, while the variable measures were developed through a comprehensive literature review. The questionnaire and scales used in this study were described in detail in the previously published protocol [21].

Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic variables in this study included sex, age, ethnicity, body mass index, education level, marital status and exercise habit, which were measured through self-designed questions.

Work-related variables

Work-related variables consisted of professional title, weekly working hours, years of working, type of work, department and night shift measured through self-designed questions.

Chronic pain

A screening question was used to identify individuals with CP according to the criteria of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) [11], “In the past year, did you have persistent or recurring pain for more than 3 months”, with responses including “Yes” and “No”. If the answer is “Yes”, the participant is asked about the specific site of the pain, including head, face, neck and shoulder, low back, stomach and intestine, hip and knee joint, general and others [22].

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0 software. Continuous variables, such as age, BMI, weekly working hours, and years of working, were grouped and presented as categorical variables. Number and frequency were used to describe categorical variables. The Chi-Square test was used to compare categorical variables of sociodemographic factors and work-related factors among nurses with and without CP. Binary logistic regression models were used to examine associations between CP and sociodemographic and work-related variables, and the model was selected for “Enter Method”. Results were shown as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For each test, the study considered the first of each categorical variable as the reference group. Based on previous relevance of CP in the literature [23, 24], we further analyzed subgroups for sex, age, type of work, and night shifts. In the univariable analysis, variables with significant between-group differences were entered into the binary regression model as independent variables. Significance level was set at P < 0.05 for all tests (two-sided). For the missing data, four variables have less than 2% missing values (age, BMI, years of working, and hours worked per week), and these missing values are all outliers. In order to ensure the completeness and veracity of the data, we chose the Expectation Maximization Algorithm to interpolate the missing data. This algorithm has a simple execution when the data size is extremely large, which finds the globally optimal solution through its own stable iterative process, and fills in the missing data with a relatively high accuracy [25].

Results

Sample characteristics

The characteristics of the sample (n = 132,910) are presented in Table 1. The majority were female (93.5%), with a mean age of 33.5 years (range: 18–65 years). Nurses with a bachelor’s degree were 87.1%. More than half (52.7%) had ten years or less of work experience, 72.2% of nurses had to work night shift.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 132,910)

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 8,666 (6.5%) |

| Female | 124,244 (93.5%) | |

| Age (years) | ≤ 30 | 48,710 (36.6%) |

| 30–40 | 63,321 (47.6%) | |

| > 40 | 20,879 (15.7%) | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 123,295 (92.8%) |

| Others | 9,615 (7.2%) | |

| Education level | Associate degree or below | 11,677 (8.8%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 115,776 (87.1%) | |

| Master’s degree or above | 5,457 (4.1%) | |

| Marital status | Married or cohabitating | 91,617 (68.9%) |

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | 3,301 (2.5%) | |

| Never married | 37,992 (28.6%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 18.5 | 13,224 (9.9%) |

| 18.5–23.9 | 91,517 (68.9%) | |

| 24-27.9 | 23,423 (17.6%) | |

| ≥ 28 | 4,746 (3.6%) | |

| Professional title | Junior | 68,593 (51.6%) |

| Mid-level | 57,952 (43.6%) | |

| Senior | 6,365 (4.8%) | |

| Weekly working hours | < 40 | 33,145 (24.9%) |

| 40–48 | 80,236 (60.4%) | |

| > 48 | 19,529 (14.7%) | |

| Years of working | ≤ 10 | 70,064 (52.7%) |

| 11–20 | 46,533 (35.0%) | |

| 21–30 | 11,782 (8.9%) | |

| > 30 | 4,531 (3.4%) | |

| Type of work | Direct patient care | 124,769 (93.9%) |

| Non-direct patient care | 8,141 (6.1%) | |

| Department | Internal medicine | 34,519 (26.0%) |

| Surgery | 29,328 (22.1%) | |

| Gynecology and obstetric | 6,752 (5.1%) | |

| Otorhinology | 4,162 (3.1%) | |

| Pediatrics | 4,478 (3.4%) | |

| Psychiatry | 928 (0.7%) | |

| Infectious disease | 2,047 (1.5%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 15,364 (11.6%) | |

| Outpatient | 6,506 (4.9%) | |

| Emergency | 8,049 (6.1%) | |

| Operating room | 9,860 (7.4%) | |

| Nursing department | 1,514 (1.1%) | |

| Others | 9,403 (7.1%) | |

| Night shift | No | 36,975 (27.8%) |

| Yes | 95,935 (72.2%) | |

| Exercise habit | No | 54,928 (41.3%) |

| Yes | 77,982 (58.7%) |

BMI: Body Mass Index

The prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain

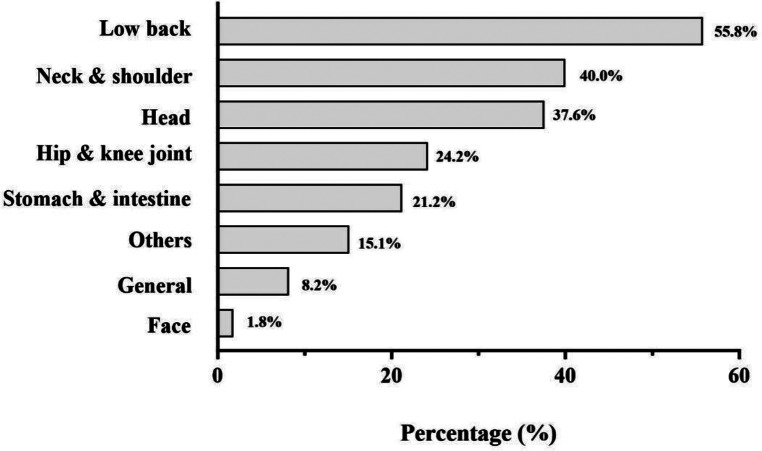

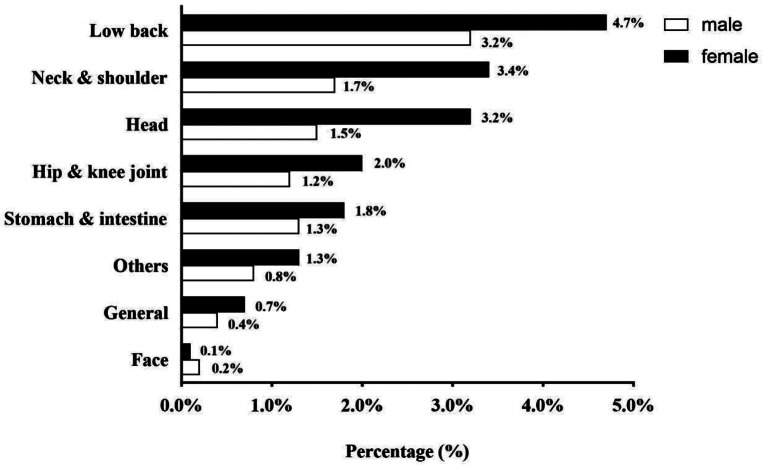

10,890 individuals experienced CP, with a prevalence of 8.2%. The prevalence of pain sites in the pain population are depicted in Fig. 2. Among those with CP, low back pain was the most common (55.8%), followed by neck and shoulder pain (40.0%) and headache (37.6%). For further analysis, we compared the prevalence of different pain sites by sex and department. The results showed that females had a statistically higher incidence of pain in all sites except face than males. There was a significant difference in the prevalence of CP sites in different departments, with outpatient department having the highest prevalence (except face) and psychiatry department having the lowest (except face, others). Detailed results are shown in Fig. 3 and sTable 6 (See Supplementary File 1).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence distribution of chronic pain by site among nurses

Fig. 3.

Prevalence distribution of chronic pain sites by sex

Univariable analyses showed that there were significant differences in sex, age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, BMI, professional title, weekly working hours, years of working, type of work, night shift, exercise habit, and the occurrence of CP (P<0.01) (Table 2). In addition, we tested for subgroups by sex and found that the results were consistent for females and the overall population, whereas males showed opposite results for ethnicity, education level, type of work, and night shifts (See Supplementary File 1, sTable 1).

Table 2.

The distribution of chronic pain by sociodemographic and work-related characteristics

| Variable | Category | Chronic pain | χ 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes

(n = 10,890) |

No

(n = 122,020) |

||||

| Sex | Male | 529 (6.1%) | 8,137 (93.9%) | 53.792 | <0.001 |

| Female | 10,361 (8.3%) | 113,883 (91.7%) | |||

| Age (years) | ≤ 30 | 2,152 (4.4%) | 46,558 (95.6%) | 1945.118 | <0.001 |

| 30–40 | 5,812 (9.2%) | 57,509 (90.8%) | |||

| > 40 | 2,926 (14.0%) | 17,953 (86.0%) | |||

| Ethnicity | Han | 9,980 (8.1%) | 113,315 (91.9%) | 22.254 | <0.001 |

| Others | 910 (9.5%) | 8,705 (90.5%) | |||

| Education level | Associate degree or below | 1,038 (8.9%) | 10,639 (91.1%) | 14.734 | 0.001 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 9,459 (8.2%) | 106,317 (91.8%) | |||

| Master’s degree or above | 393 (7.2%) | 5,064 (92.8%) | |||

| Marital status | Married or cohabitating | 8,525 (9.3%) | 83,092 (90.7%) | 888.706 | <0.001 |

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | 493 (14.9%) | 2,808 (85.1%) | |||

| Never married | 1,872 (4.9%) | 36,120 (95.1%) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 18.5 | 793 (6.0%) | 12,431 (94.0%) | 290.821 | <0.001 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 7,187 (7.9%) | 84,330 (92.1%) | |||

| 24-27.9 | 2,341 (10.0%) | 21,082 (90.0%) | |||

| ≥ 28 | 569 (12.0%) | 4,177 (88.0%) | |||

| Professional title | Junior | 4,113 (6.0%) | 64,480 (94.0%) | 919.674 | <0.001 |

| Mid-level | 6,041 (10.4%) | 51,911 (89.6%) | |||

| Senior | 736 (11.6%) | 5,629 (88.4%) | |||

| Weekly working hours | < 40 | 2,566 (7.7%) | 30,579 (92.3%) | 116.604 | <0.001 |

| 40–48 | 6,343 (7.9%) | 73,893 (92.1%) | |||

| > 48 | 1,981 (10.1%) | 17,548 (89.9%) | |||

| Years of working | ≤ 10 | 3,779 (5.4%) | 66,285 (94.6%) | 1869.928 | <0.001 |

| 11–20 | 4,726 (10.2%) | 41,807 (89.8%) | |||

| 21–30 | 1,685 (14.3%) | 10,097 (85.7%) | |||

| > 30 | 700 (15.4%) | 3,831 (84.6%) | |||

| Type of work | Direct patient care | 10,106 (8.1%) | 114,663 (91.9%) | 23.798 | <0.001 |

| Non-direct patient care | 784 (9.6%) | 7,357 (90.4%) | |||

| Night shift | No | 3,537 (9.6%) | 33,438 (90.4%) | 128.266 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 7,353 (7.7%) | 88,582 (92.3%) | |||

| Exercise habit | No | 4,939 (9.0%) | 49,989 (91.0%) | 79.305 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 5,951 (7.6%) | 72,031 (92.4%) | |||

BMI: Body Mass Index

Association factors for chronic pain

Due to the covariance between age and years of work, we selected between the two to include age in the final binary logistic regression model. The analysis showed that ten variables were significantly associated with CP. Female (OR = 1.10, 95% Confidence Interval [95% CI] = [1.00, 1.21]), age > 40 (OR = 3.01, 95% CI [2.77, 3.27]), other ethnicities (OR = 1.17, 95% CI [1.09, 1.25]), associate degree or below (OR = 1.36, 95% CI [1.20, 1.55]), married or cohabitating (OR = 1.10, 95% CI [1.03, 1.17]), BMI ≥ 28 (OR = 1.59, 95% CI [1.42, 1.79]), mid-level title (OR = 1.17, 95% CI [1.11, 1.23]), working hours per week over 48 (OR = 1.32, 95% CI [1.24, 1.41]), night shift (OR = 1.08, 95%CI [1.03, 1.14]), and no exercise habit (OR = 1.21, 95% CI [1.16, 1.26]) were positively associated with the occurrence of CP (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Binary logistic regression analysis of associated factors with chronic pain

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1 | |

| Female | 1.10 [1.00, 1.21] | 0.048 | |

| Age (years) | ≤ 30 | 1 | |

| 31–40 | 1.83 [1.71, 1.96] | < 0.001 | |

| > 40 | 3.01 [2.77, 3.27] | < 0.001 | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 1 | |

| Others | 1.17 [1.09, 1.25] | < 0.001 | |

| Education level | Master’s degree or above | 1 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1.21 [1.09, 1.35] | < 0.001 | |

| Associate degree or below | 1.36 [1.20, 1.55] | < 0.001 | |

| Marital status | Never married | 1 | |

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | 1.64 [1.46, 1.84] | < 0.001 | |

| Married or cohabitating | 1.10 [1.03, 1.17] | 0.005 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 18.5 | 1 | |

| 18.5–23.9 | 1.06 [0.99, 1.15] | 0.116 | |

| 24-27.9 | 1.27 [1.16, 1.38] | < 0.001 | |

| ≥ 28 | 1.59 [1.42, 1.79] | < 0.001 | |

| Professional title | Junior | 1 | |

| Mid-level | 1.17 [1.11, 1.23] | < 0.001 | |

| Senior | 1.02 [0.92, 1.13] | 0.705 | |

| Weekly working hours | < 40 | 1 | |

| 40–48 | 1.01 [0.96, 1.06] | 0.836 | |

| > 48 | 1.32 [1.24, 1.41] | < 0.001 | |

| Type of work | Non-direct patient care | 1 | |

| Direct patient care | 1.02 [0.94, 1.11] | 0.636 | |

| Night shift | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.08 [1.03, 1.14] | 0.003 | |

| Exercise habit | Yes | 1 | |

| No | 1.21 [1.16, 1.26] | < 0.001 |

BMI: Body Mass Index; OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval

Additionally, we analysed subgroups by different groups of sex, age, type of work, and night shifts. It was found that age above 30 years, marital status (separated, widowed, or divorced), higher BMI (over 24), working more than 48 h per week, and no exercise habits were stable risk factors for CP in the nurse population. (The results of the subgroup analyses are presented in sTable 2, sTable 3, sTable 4 and sTable 5 in the Supplementary File 1)

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of CP among nurses in tertiary hospitals in China was 8.2%, which was lower than expected. The interpretation could be influenced by several aspects. First, it may be due to sample selection, study settings, and variation in region and population of different countries. For example, according to the review by Cohen et al., the prevalence of CP in different countries varies from 11.0 to 40.0% [26]. Furthermore, pain is inherently subjective and CP assessment methods largely rely on self-reporting. The participants in this study were healthcare professionals whose self-report bias may have further influenced the prevalence estimates. Healthcare professionals often prioritize patients’ needs due to their professional responsibilities, paying little attention to their own health, which may dilute their discomfort [27, 28]. Third, the healthy worker effect (HWE) may introduce a bias that underestimates the prevalence of CP among nurses [29]. Although there is limited direct research on healthcare workers [30], HWE has been widely demonstrated in occupational population studies to lead to underestimation of health risks for those in employment - due to individuals with the condition being more likely to exit high-risk positions [31–33]. Studies have shown that a portion of the working-age population chooses to leave the labor market early due to chronic health problems [34]. Thus, healthcare workers with severe CP may be more inclined to transfer out of clinical positions or exit their careers, leading to biased results by including only practitioners with higher pain tolerance or milder symptoms in the current sample. In addition, the youthful characteristics of the study population may also be a factor for the prevalence lower than expected. Epidemiologic surveys showed that the prevalence of CP tends to increase significantly with age [35, 36]. Given the young age of our study population (80% or more < 40 years), which may also have led to an underestimation of CP prevalence.

The findings of this study showed that the most common sites of CP were the low back, neck and shoulder, and head, which is in line with previous studies. Zheng et al. reported that the CP areas were centered on the back and upper limbs [37]. A systematic review indicated that the low back, neck, shoulders, and wrists were the most susceptible sites for work-related skeletal disorders among all healthcare worker [38]. Additionally, a multicenter cross-sectional survey reported that ICU nurses most frequently experienced pain in the low back, neck and shoulders [7]. Our findings further confirmed the high prevalence of CP in these sites among healthcare professionals. Furthermore, our research showed that the prevalence of pain was higher in females compared to males at all sites, except the face. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that females are more likely to experience CP than males [24, 39]. Evidence has suggested that sex differences may be caused by various factors, such as sex hormone level [40], pain sensitivity [41], and psychosocial mechanisms [42], which may collectively contribute to a higher incidence of CP in females.

This study further explored the prevalence of CP among nurses in different departments, with the highest prevalence in the outpatient department (12.0%) and the lowest in the psychiatric department (6.5%), which showed significant differences. We analyzed age and years of work experience in different departments, which showed that outpatient nurses were markedly older than other departments (42.4% of nurses > 40 years), with a higher proportion having over 10 years of work experience (See Supplementary File 1, sFigures 1 and 2). Previous studies have shown that high age and years of service have a higher prevalence of CP [23, 43], which may partly explain why outpatient nurses have the highest prevalence of CP. Meanwhile, psychiatric nurses have the lowest prevalence of CP. There may be two main reasons for this situation. First, compared with other departments, due to the demands and characteristics of their work, psychiatric nurses focus their daily work on medication administration, ward rounds, and psychotherapy, and are involved less in nursing operations that tend to cause CP. They usually emphasize more on improving patients’ mental health [44]. And these tasks are relatively less likely to cause physical burdens. Second, job satisfaction is a risk for the prevalence of CP [45]. Studies have shown that job satisfaction is negatively correlated with the occurrence of CP [23, 46]. Chinese nurses generally experience moderate job satisfaction [47, 48], while psychiatric nurses generally have higher job satisfaction [49], which may be one of the important reasons for their lower prevalence of CP. The above points involve hypotheses that still need further research.

This study comprehensively analyzed the factors associated with CP in nurses. The results show that sex, age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, BMI, weekly working hours, years of working, night shifts, and exercise habit are related to the occurrence of CP among nurses. Most findings align with previous studies on nurses’ pain, despite regional and demographic variations. For example, a meta-analysis of non-specific chronic low back pain among nurses identified associations with sex, marital status, work patterns, and professional experience [23]. Specifically, female nurses may have a higher risk for this type of pain than male counterparts, and married nurses faced an elevated risk compared to those who were single. In addition, nurses working night shifts were more likely to suffer from chronic low back pain than day shift workers, which may be related to disrupted biorhythms and improper body posture during work. Meanwhile, working for over 10 years was also seen as a significant risk factor, suggesting that the cumulative body burden may lead to increased pain as careers lengthen. Skela-Savič et al. emphasized that aging also contributes to an increased likelihood of CP [50]. Younan et al. showed that underweight or overweight, more than 6 years of service, lack of exercise, and over 40 h of work per week were prone to skeletal muscle disorders [51], which are key contributors to CP [52]. Subgroup analyses revealed stable risk factors for CP among nurses: being over 30 years, marital status (separated, widowed, or divorced), higher BMI (over 24), working more than 48 h per week, and lack of exercise habits.

To improve CP problems among nurses, a series of evidence-based interventions are necessary. First, regular training and education on ergonomic knowledge should be organized [53], including the definition of ergonomics, types of risks, and work postures, combined with biomechanical model demonstrations to provide training on patient transfers, office work, and bending while maintaining correct posture [54–56]. Emphasis on teaching proper body mechanics and lifting techniques, especially for females over 30 years old, to enhance their awareness of health risks and self-protection. Next, promote smart modifications to the work environment, and recommend auxiliary devices (e.g., electric beds, sliding sheets, hoists) if conditions permit [57]. Evidence suggests that patient transfer of assistive devices is effective in reducing nurses’ risk of WMSD [58]. Third, optimize the shift system, rationally arrange the number of night shifts, avoid working continuously over 10 h, to ensure that employees have enough rest time [59]. For example, the data-driven intelligent nursing scheduling management system studied by Zhai et al. can be referred to refine scheduling [60]. Finally, promoting an active and healthy lifestyle, encouraging participation in physical activity (e.g., jogging, swimming, playing ball games, etc.), especially among nurses who are usually inactive and with a BMI above 24. Epidemiologic studies have found that physical inactivity and high BMI are associated with a higher risk of chronic low back, neck and shoulder pain, and that this effect may be minimized by exercise [61, 62].

Limitations

The primary strength of the current study is using a nationally representative population to investigate the prevalence and associated factors of CP among nurses. However, there are some limitations of this study. First, due to the cross-sectional study design, a causal association between the variables and CP could not be verified. Second, the measurement of CP relied on single questions and did not assess the severity of CP. Moreover, given the HWE, we could not exclude the possibility that workers with CP changed jobs or left the labor market due to occupational physical burden, which may underestimate the real prevalence. Finally, data were collected through a self-assessment questionnaire, which may be subject to subjective factors leading to the risk of omission, recall and non-response bias.

Conclusion

While studies have focused on pain among nurses, few large-scale epidemiologic studies have systematically examined the prevalence of CP and its association with demographic characteristics and work-related factors among nurses in tertiary hospitals in China. This study showed that the prevalence of CP among nurses was 8.2%. Associated factors included sex, age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, BMI, weekly working hours, years of working, night shift, and exercise habit. Nurses are at the core of the healthcare system, and their health directly impacts the quality and safety of patient care. It is essential for hospital administrators to implement interventions aimed at reducing CP to safeguard the occupational health of nurses.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Chinese Nursing Association for this cohort research project. We thank the 132,910 participants who responded to the survey and the nursing administrators of the participating hospitals for their support of this survey.

Abbreviations

- WMSDs

Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders

- CP

Chronic pain

- CDC

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- NMHS

The Nurses’ Mental Health Study

- IASP

The International Association for the Study of Pain

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- ORs

Odds Ratios

- CIs

Confidence Intervals

- HWE

The Healthy Worker Effect

Author contributions

Study design: Zhenhui Ren, Yamin Li, Yusheng Tian; Data collection: Zhenhui Ren, Jiaxin Yang, Chongmei Huang, Qiang Yu, Xuting Li, Zengyu Chen, Dan Zhang, Chunhui Bin, Meng Ning, Yiting Liu, Jianghao Yuan, Yusheng Tian; Data analysis: Zhenhui Ren; Study supervision: Yamin Li, Yusheng Tian; Manuscript writing: Zhenhui Ren; Critical revisions for important intellectual content: Zhenhui Ren, Yamin Li, Yusheng Tian.

Funding

Chinese Nursing Association (Grant Number: ZHKY202306); The Scientific Research Project of Health Commission of Hunan Province (Grant Number: W20243200).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (LYF20230048), and the rules and procedures of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed during the study. All participants received informed consent forms, only those who agreed started the questionnaire and they had the right to choose to continue or withdraw from the study at any point in time.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yamin Li, Email: amin5433@163.com.

Yusheng Tian, Email: tianyusheng@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lu YM, Lei J, You HJ. Research progress on pain mechanism and non-pharmacological treatment after skeletal muscle injury. Chin J Pain Med. 2023;29(02):138–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang K, Zeng X, Li J, Guo Y, Wang Z. The prevalence and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2024;157:104826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahsavari D, Sobani ZA. New insight into endoscopic work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMD): why repeated motions damage. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(3):716–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun W, Yin L, Zhang T, Zhang H, Zhang R, Cai W. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses: a meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2023;52(3):463–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen XH, Li N. Investigation on occupational low back pain protection of ICU nurses in 3A grade hospitals. Fujian Med J. 2017;39(01):149–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu JM, Guo FY. Investigation of occupational musculoskeletal disorder, sleep quality and work pressure of nursing staff in a hospital in Shanghai. Ind Hlth Occup Dis. 2018;44(06):432–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang S, Lu J, Zeng J, Wang L, Li Y. Prevalence and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among intensive care unit nurses in China. Workplace Health Saf. 2019;67(6):275–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laštovková A, Nakládalová M, Fenclová Z, Urban P, Gad’ourek P, Lebeda T, et al. Low-back pain disorders as occupational diseases in the Czech Republic and 22 European countries: comparison of National systems, related diagnoses and evaluation criteria. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2015;23(3):244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasir A, Afridi M, Afridi OK, Khan MA, Khan A, Zhang J, et al. The persistent pain enigma: molecular drivers behind acute-to-chronic transition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2025;173:106162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puntillo F, Giglio M, Paladini A, Perchiazzi G, Viswanath O, Urits I, et al. Pathophysiology of musculoskeletal pain: a narrative review. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720x21995067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019;160(1):19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM, Donaldson LJ, Jones GT. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. Bmj Open 2016;6(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Sá KN, Moreira L, Baptista AF, Yeng LT, Teixeira MJ, Galhardoni R, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep. 2019;4(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Zimmer Z, Fraser K, Grol-Prokopczyk H, Zajacova A. A global study of pain prevalence across 52 countries: examining the role of country-level contextual factors. Pain. 2022;163(9):1740–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, DeBar L, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United states, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kheiry F, Rakhshan M, Shaygan M. The prevalence and associated factors of chronic pain in nurses Iran. Rev Latinoam Hiperte. 2019;14(1):21–. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaygan M, Tehranineshat B, Mohammadi A, Foruhi Z. A national survey of the prevalence of chronic pain in nursing students and the associated factors. Investig Educ Enferm. 2022;40(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.National Health Commission P. Development and information technology department. Statistical Bulletin of China’s Health Development in 2022. 2023; Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s3585u/202309/6707c48f2a2b420fbfb739c393fcca92.shtml

- 19.Seo S. A review and comparison of methods for detecting outliers in univariate data sets. University of Pittsburgh; 2006.

- 20.Ren F, Yu H, Zhao B, Hao Y, Wang J, editors. Identification method research of invalid questionnaire based on partial least squares regression. Chinese Control and Decision Conference; 2011.

- 21.Ning M, Li X, Chen Z, Yang J, Yu Q, Huang C, et al. Protocol of the nurses’ mental health study (NMHS): a nationwide hospital multicentre prospective cohort study. Bmj Open. 2025;15(2):e087507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byrne EM, Kirk KM, Medland SE, McGrath JJ, Colodro-Conde L, Parker R, et al. Cohort profile: the Australian genetics of depression study. Bmj Open. 2020;10(5):e032580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun W, Zhang H, Tang L, He Y, Tian S. The factors of non-specific chronic low back pain in nurses: A meta-analysis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2021;34(3):343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborne NR, Davis KD. Sex and gender differences in pain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2022;164:277–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu JY, He YL, Cui LZ, Huang ZX. Distribution consistency-based missing value imputation algorithm for large-scale data sets. J Tsinghua Univ (Science Technology). 2023;63(5):740–53. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2082–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohanty A, Kabi A, Mohanty AP. Health problems in healthcare workers: A review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(8):2568–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Liu J, Chen M, Tan X, Zheng T, Kang Z, et al. Sleep problems of healthcare workers in tertiary hospital and influencing factors identified through a multilevel analysis: a cross-sectional study in China. Bmj Open. 2019;9(12):e032239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chowdhury R, Shah D, Payal AR. Healthy worker effect phenomenon: revisited with emphasis on statistical methods - a review. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2017;21(1):2–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hämmig O, Vetsch A. Stress-buffering and health-protective effect of job autonomy, good working climate, and social support at work among health care workers in Switzerland. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(12):e918–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunger B, Seibt R. Psychosocial work stress and health risks - a cross-sectional study of shift workers from the hotel and catering industry and the food industry. Front Public Health. 2022;10:849310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seibt R, Kreuzfeld S. Working time reduction, mental health, and early retirement among part-time teachers at German upper secondary schools - a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1293239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Payne J, Esquivel NS, Strazza K, Viator C, Durocher B, Sivén J, et al. Work-related factors associated with psychological distress among grocery workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. AJPM Focus. 2024;3(6):100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laaksonen M, Ilmakunnas I, Tuominen S. The impact of vocational rehabilitation on employment outcomes: A regression discontinuity approach. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2022;48(6):498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray CB, de la Vega R, Murphy LK, Kashikar-Zuck S, Palermo TM. The prevalence of chronic pain in young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2022;163(9):e972–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang PF, Bazarova NN, Wethington E. How older adults with chronic pain manage social support interactions with mobile media. Health Commun. 2022;37(3):384–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yongjun Z, Tingjie Z, Xiaoqiu Y, Zhiying F, Feng Q, Guangke X, et al. A survey of chronic pain in China. Libyan J Med. 2020;15(1):1730550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacquier-Bret J, Gorce P. Prevalence of body area work-related musculoskeletal disorders among healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2023;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Steingrímsdóttir ÓA, Landmark T, Macfarlane GJ, Nielsen CS. Defining chronic pain in epidemiological studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2017;158(11):2092–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(1):76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mogil JS. Sources of individual differences in pain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2021;44:1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):52–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durán J, Zitko P, Barrios P, Margozzini P. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and chronic widespread pain in chile: prevalence study performed as part of the National health survey. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27(6s):S294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tzeng WC, Feng HP, Lin CH, Chang YC, Haddad M. Physical health attitude scale among mental health nurses in taiwan: validation and a cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 2023;9(6):e17446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin G, Nie Y, Fan J, Yang Y, Chen D, Li Y, et al. Association between urinary phthalate levels and chronic pain in US adults, 1999–2004: A nationally representative survey. Front Neurol. 2023;14:940378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wijayanti IAS, Adnyana IMO, Widyadharma IPE, Wiratnaya IGE, Mahadewa TGB, Astawa INM. Neuroinflammation mechanism underlying neuropathic pain: the role of mesenchymal stem cell in neuroglia. AIMS Neurosci. 2024;11(3):226–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Zheng J, Liu K, Liu X, Wu Y, Wang J, et al. Workplace violence against nurses, job satisfaction, burnout, and patient safety in Chinese hospitals. Nurs Outlook. 2019;67(5):558–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chu WJ, Han RC, Liu HF, Liu Y, Zheng W. Study on the relationship between work satisfaction and resignation intention of nurses in third class hospitals in Xu. Health Vocat Educ. 2023;41(23):150–4. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou H, Jiang F, Rakofsky J, Hu L, Liu T, Wu S, et al. Job satisfaction and associated factors among psychiatric nurses in tertiary psychiatric hospitals: results from a nationwide cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(12):3619–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skela-Savič B, Pesjak K, Hvalič-Touzery S. Low back pain among nurses in Slovenian hospitals: cross-sectional study. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(4):544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Younan L, Clinton M, Fares S, Jardali FE, Samaha H. The relationship between work-related musculoskeletal disorders, chronic occupational fatigue, and work organization: A multi-hospital cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(8):1667–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De la Corte-Rodriguez H, Roman-Belmonte JM, Resino-Luis C, Madrid-Gonzalez J, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. The role of physical exercise in chronic musculoskeletal pain: best medicine-a narrative review. Healthc (Basel). 2024;12(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Van Eerd D, Irvin E, Le Pouésard M, Butt A, Nasir K. Workplace musculoskeletal disorder prevention practices and experiences. Inquiry. 2022;59:469580221092132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang S, Li L, Wang L, Zeng J, Yan B, Li Y. Effectiveness of a multidimensional intervention program in improving occupational musculoskeletal disorders among intensive care unit nurses: a cluster-controlled trial with follow-up at 3 and 6 months. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang A, Zhou Y, Li X, Wang W, Zhao X, Chen P, et al. Investigating and analyzing the current situation and factors influencing chronic neck, shoulder, and lumbar back pain among medical personnel after the epidemic. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Demir OB, Yilmaz FT. The effect of posture regulation training on musculoskeletal disorders, fatigue level and job performance in intensive care nurses. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anak Nicholas Felix S, Siew WF. Prevalence, associated factors, and risk management practices of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among registered nurses in hospitals in sarawak, Malaysia. SAGE Open Nurs. 2025;11:23779608251335546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdul Halim NSS, Ripin ZM, Ridzwan MIZ. Effects of patient transfer devices on the risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2023;29(2):494–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Y, Li Z, Chen Q, Fan Y, Wang J, Ye Y, et al. Association of working hours and cumulative fatigue among Chinese primary health care professionals. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1193942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhai Y, Li R, Yan Z. Research on application of meticulous nursing scheduling management based on data-driven intelligent optimization technology. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022:3293806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sterling M, de Zoete RMJ, Coppieters I, Farrell SF. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain part 4: neck pain. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Bigand T, Wilson M, Bindler R, Daratha K. Examining risk for persistent pain among adults with overweight status. Pain Manag Nurs. 2018;19(5):549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.