Abstract

Background

There is an unmet need for novel immunotherapies to overcome immune evasion in patients with advanced skin cancers resistant to programmed death (PD)-1 / PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade. Cavrotolimod is a novel spherical nucleic acid configuration of a toll-like receptor 9 agonist oligonucleotide, designed to trigger innate and adaptive immune responses to tumors.

Patients and methods

The safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and preliminary efficacy of intratumoral cavrotolimod, first dosed alone and then in combination with anti-PD-1 antibodies (pembrolizumab or cemiplimab), were assessed in a combined Phase 1b/2 dose escalation/dose expansion study in patients with advanced skin cancers, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT03684785).

Results

A total of 58 patients (20 in dose-escalation and 38 in expansion cohorts) were enrolled. 55 (95%) of the 58 patients experienced progressive disease on prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy. Cavrotolimod, in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy, produced objective responses in 6 (12%) and stable disease (SD) in 8 (16%) of 51 evaluable patients on this study, leading to a disease control rate of 27% (14/51). 5 of 6 (83%) patients with an objective response and 13 of 14 (93%) patients with disease control had progressed on prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy. Disease control was durable, with median duration of 54 (range 24–88+) weeks for responses and 24 (range 11–35+) weeks for SD. Regression of both injected and non-injected tumors was observed. Cavrotolimod, alone and in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy, had a manageable safety profile with mostly transient adverse events (AEs). The most frequent Grade 3/4 cavrotolimod-related AEs were fatigue and injection site reactions. Cavrotolimod dosing was associated with robust chemokine/cytokine induction and lymphocyte activation in peripheral blood. Serial tumor biopsies of injected tumors suggested upregulation of genes associated with the interferon pathway, antiviral proteins, immune checkpoints, chemokines, granzymes and costimulatory proteins, along with increases in certain immune cell populations.

Conclusions

Cavrotolimod had a manageable safety profile and showed clinical activity in anti-PD-(L)1 refractory cutaneous malignancies, suggesting potential for further development as an antitumor immunotherapy in combination with other agents.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Toll-like receptor - TLR, Intratumoral, Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, Nanoparticle, Skin Cancer

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Anti-programmed death (PD)-1 and anti-PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) therapies can elicit durable responses in a subset of patients with advanced cutaneous malignancies. However, a significant proportion of patients exhibit intrinsic or acquired resistance. There is an unmet need to find effective therapies to overcome immune evasion in these patients. Intratumoral (IT) immunotherapies, such as oncolytic viruses, have shown potential in stimulating immune responses against cancer cells in a subset of patients with advanced skin cancers. However, more therapies with novel mechanisms of action are needed to expand the benefits of IT immunotherapy in anti-PD-(L)1 refractory cancers.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Cavrotolimod, a novel spherical nucleic acid configuration of a toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonist oligonucleotide, is designed to facilitate higher cellular uptake and better stimulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses against tumors. In this study, IT cavrotolimod, both as a monotherapy and in combination with PD-1 blockade (pembrolizumab or cemiplimab), yielded objective responses and clinical benefit in a subset of patients with anti-PD-(L)1 refractory melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma. IT cavrotolimod was safe and well-tolerated. Additionally, IT cavrotolimod led to increased inflammation within injected tumors and induced Th1-type chemokines and cytokines, alongside immune cell activation in peripheral blood. Regression of both injected and non-injected tumors was observed, suggesting induction of systemic antitumor immunity.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

These translational data reveal important insights about the pharmacodynamic effects of TLR9 agonists and possible rational combinations of TLR9 agonist therapies with other agents, including checkpoint inhibitors, and provide evidence for the promise of combination of IT approaches with other immunotherapy agents.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), specifically antibodies targeting the programmed death (PD)-1/PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway, have proven beneficial in a variety of cancers, including melanoma,1 Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC),2 and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC).3 The impressive success of PD-(L)1 blockade in advanced skin cancers reflects the induction of antitumor immunity against tumor neoantigens generated in high tumor mutational burden tumors secondary to ultraviolet radiation exposure4 or, in the case of virus-positive MCC, Merkel cell polyoma viral antigens. However, a significant proportion of patients do not experience durable benefit with PD-(L)1 blockade, and there are few effective therapies available after disease progression.

Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonism initially activates antigen-non-specific innate immunity followed by antigen-specific adaptive immunity.5 The innate immune effects of TLR9 activation can promote tumor killing either directly, through factors such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and granzyme B, or indirectly, through the activation of natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity.6 TLR9-mediated immune activation of B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs)7 is followed by the generation of antigen-specific antibody and T-cell immune responses. The pDCs activated through TLR9 become competent to recruit and activate CD4+ or CD8+ T cells,8 and suppress regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells.9 Because the activation of T cells results in PD-1 upregulation,10 risking lymphocyte anergy when engaged by tumor-expressed PD-L1, this TLR9-based mechanism of lymphocyte recruitment and activation is expected to synergize well with anti-PD-(L)1 therapies especially in T cell-poor tumor microenvironments (TME), wherein those agents have limited clinical activity.

Cavrotolimod is a spherical nucleic acid (SNA) (online supplemental material figure 1) designed as a TLR9 agonist. SNA constructs are three-dimensional arrangements of oligonucleotides where the nucleic acids are densely packed in a radial orientation, which facilitates high cellular uptake,11 high endosomal concentration (the intracellular localization of TLR9)12 and facile interaction of the oligonucleotide agonist with the TLR9 target due to the external presentation of the oligonucleotides. The projection of the oligonucleotide from the liposome surface contrasts with other oligonucleotide delivery technologies where the oligonucleotides are encapsulated within lipid or virus-like particles.

Cavrotolimod exhibits cellular uptake and activity that is greater than the corresponding unformulated oligonucleotide and demonstrates specificity for TLR9 in vitro.13 In a variety of preclinical murine tumor models, cavrotolimod monotherapy administered via intratumoral (IT) or subcutaneous (SC) route led to decreased tumor volume and increased median survival of exposed animals compared with vehicle controls.14 15 IT cavrotolimod also produced antitumor effects and increased levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in preclinical mouse models of MCC and CSCC. Further, cavrotolimod together with a murine anti-PD-1 antibody yielded improvements in survival HR versus the antibody alone.15 Finally, results from a healthy participant clinical study (NCT03086278) suggested that cavrotolimod elicited cytokine and chemokine expression, and immune cell activation, in the blood after SC dosing.16

In this study, we sought to evaluate the safety, efficacy and immunologic effects of cavrotolimod, administered alone for 2 weeks and then together with an anti-PD-1 antibody, in patients with anti-PD-(L)1 resistant tumors. Melanoma, CSCC and MCC were selected as proof-of-concept focus areas for cavrotolimod for several reasons. First, these immunogenic cancers have unmet medical need in the post-PD-(L)1 setting. Second, these tumors often have superficial lesions that can be palpated, or imaged with ultrasound, for readily accessible IT administration and biopsy. Furthermore, there is precedent for activity for mechanistically related TLR agonists in these tumor types. Imiquimod, a TLR7 agonist, is used as a topical treatment for early stage CSCC.17 An IT TLR4 agonist (G100) led to tumor regression in locoregional and metastatic MCC.18 More recently, TLR9 agonists including vidutolimod,19 SD-10120 and tilsotolimod21 have demonstrated varying levels of activity in advanced melanoma. Unformulated CpG oligonucleotides SD-10120 and tilsotolimod21 have demonstrated limited success in eliciting clinical antitumor responses in the post-PD-1 setting. However, vidutolimod, a CpG oligonucleotide-loaded virus-like particle, given IT along with systemic pembrolizumab has shown meaningful clinical activity in anti-PD-1 refractory melanoma.19 Finally, TLR agonism is also implicated as one of the potential mechanisms of efficacy of the oncolytic virus talimogene laherparepvec, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for IT melanoma therapy.22

Materials and methods

Study design

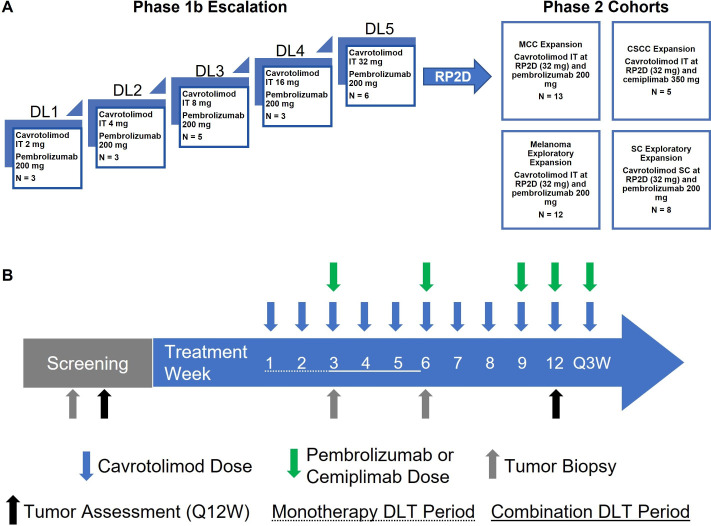

AST-008-102 was a combined Phase 1b/2 dose escalation/dose expansion study (NCT03684785) (figure 1). The Phase 1b dose escalation part used a classical 3+3 design, with ascending dose cohorts of IT cavrotolimod combined with intravenous pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cavrotolimod was dosed at weekly intervals for 8 weeks, followed by dosing every 3 weeks starting in study week 9. Starting in study week 3, intravenous pembrolizumab was administered every 3 weeks. The initial weekly dosing followed by every 3-week cavrotolimod dosing was informed by the vidutolimod dosing schedule19 and designed for patient convenience through less frequent dosing and alignment with the pembrolizumab dosing schedule. Because cavrotolimod was dosed alone for 2 weeks prior to the addition of pembrolizumab, (1) there were two dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) periods for each patient: a monotherapy DLT period of 15 days followed by a combination DLT period of 22 days. This design also had the advantage of enabling the assessment of cavrotolimod safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics alone and together with anti-PD-1 therapy.

Figure 1. AST-008–102 study overview. (A) Study design. (B) Schedule of dosing, tumor assessments and DLT periods. CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; DL, dose level; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma; N, number of patients enrolled; RP2D, recommended Phase 2 dose; SC, subcutaneous; IT, intratumoral.

Five dose escalation cohorts using 2, 4, 8, 16 or 32 mg doses of cavrotolimod were evaluated. The starting dose of cavrotolimod was conservatively selected based on preclinical and Phase 1a safety data, as well as published data from CpG7909 trials,5 as the pharmacophore in cavrotolimod is derived from CpG7909. A full rationale for the starting dose and dose range is provided in section 5.4 of the protocol in the online supplemental material. The Phase 2 dose expansion part evaluated the recommended dose of cavrotolimod (32 mg) administered either IT or SC in combination with intravenous pembrolizumab or cemiplimab in four additional cohorts of patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors refractory to PD-(L)1 therapy. These included three IT cohorts, enrolling patients with melanoma, MCC and CSCC, respectively, and a fourth basket cohort evaluating SC cavrotolimod in patients with no superficial tumor lesion accessible for repeated IT injection. Pembrolizumab was used in the MCC, melanoma, and SC dosing cohorts, and cemiplimab in the CSCC cohort to match with FDA-approved indications at the time of study design.

The MCC and CSCC expansion cohorts employed a Simon’s two-stage optimal design (Simon, 1989) to enable early termination for futility while maintaining statistical integrity. Assuming a null response rate of 5% and an alternative of 20%, with 5% type I error and 80% power, the design specified enrollment of 10 patients initially, with expansion to 29 if at least one response was observed; the null hypothesis would have been rejected if at least four responses were seen among 29 evaluable patients. The dose expansion cohorts in melanoma and using the SC route were for hypothesis generation and not powered for efficacy. The study was terminated for administrative reasons before enrollment into any Phase 2 cohort was complete. Actual enrollment by cohort is shown in figure 1 and table 1.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Dose escalation cohorts | Dose expansion cohorts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=20) |

MCC (n=13) |

CSCC (n=5) |

Melanoma (n=12) |

SC (n=8) |

|

| Mean age, years (range) | 62.8 (30–86) | 71.9 (56–92) | 61.2 (54–67) | 69.0 (58–78) | 67.8 (41–77) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 5 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 2 (40.0) | 4 (33.3) | 2 (25.0) |

| Male | 15 (75.0) | 9 (69.2) | 3 (60.0) | 8 (66.7) | 6 (75.0) |

| ECOG, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 9 (45.0) | 6 (46.2) | 0 | 9 (75.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| 1 | 11 (55.0) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (100.0) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 20 (100.0) | 12 (92.3) | 5 (100.0) | 11 (91.7) | 8 (100) |

| Tumor type, n (%) | |||||

| Melanoma | 10 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | 12 (100.0) | 3 (37.5) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 5 (25.0) | 13 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (25.0) |

| Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (10.0) | 0 | 5 (100.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (10.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colon adenocarcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25.0) |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) |

| Metastatic disease at screening, n (%) | 19 (95.0) | 12 (92.3) | 3 (60.0) | 12 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Prior PD-(L)1, n (%) | 19 (95.0) | 13 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Progressive disease at end of treatment on PD-(L)1, n (%) | 17 (85.0) | 13 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Prior lines of systemic therapy, n (%) | |||||

| 1 | 7 (35.0) | 8 (61.5) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| 2 | 5 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 2 (16.7) |

| 3 | 4 (20.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| ≥4 | 4 (20.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (41.7) |

CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma; PD-(L)1, programmed death-1 / programmed death ligand 1.

The study was approved by institutional review boards at each participating center. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. Written informed consent was obtained prior to the initiation of screening procedures.

Patients

In the dose escalation cohorts, eligible patients were adults with an advanced, inoperable, histologically confirmed solid tumor. Prior exposure to ICI was permitted, but not required. Patients had to have at least one superficial tumor, at least 1.0 cm in diameter, amenable to repeated IT injection via palpation or ultrasound, and at least two target lesions evaluable per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) V.1.1.23 One lesion was to remain non-injected throughout the study to monitor for abscopal effects.

In the dose expansion cohorts of melanoma, MCC and CSCC, only one evaluable target lesion was required. Patients were required to have confirmed tumor progression24 on prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy (avelumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab or cemiplimab) and had to receive the anti-PD-(L)1 therapy as the most recent preceding line of therapy with the last dose administered within 20 weeks of the first dose of cavrotolimod. Another expansion cohort evaluated SC cavrotolimod plus intravenous pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors, without superficial injectable lesions, and who had confirmed disease progression on an anti-PD-(L)1.

Full inclusion/exclusion criteria are found in the online supplemental material.

Objectives

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of cavrotolimod alone and in combination with pembrolizumab or cemiplimab. The secondary objectives were to recommend a cavrotolimod dose and regimen for further study, assess cavrotolimod PK, evaluate the immunologic effects of cavrotolimod alone and together with PD-1 blockade (pembrolizumab or cemiplimab) in blood and TME, and to provide a preliminary estimate of antitumor efficacy of cavrotolimod and pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. A secondary objective specific to the dose expansion part was to provide a preliminary estimate of efficacy of cavrotolimod together with pembrolizumab or cemiplimab in patients with advanced cancers resistant to PD-(L)1 blockade.

Treatment administration

All patients received weekly outpatient cavrotolimod injections for the first 8 weeks of the study, followed by injections every 3 weeks starting in week 9. Qualified professionals administered cavrotolimod. Pembrolizumab (200 mg) or cemiplimab (350 mg) was administered intravenously every 3 weeks starting in week 3. Cavrotolimod was injected IT into a maximum of four lesions per visit in all cohorts, with the total dose (as per cohort) and volume split equally among the injected lesions, except the SC expansion cohort, in which the entire dose was administered SC at a single site. The volume of the IT dose, which could range from 1 mL to 8 mL, was determined based on the diameter of the smallest injected tumor. As treatment progressed, if tumor lesions were no longer accessible for IT injection, SC administration of cavrotolimod was allowed.

Safety and efficacy assessments

Safety assessment tools included physical examinations, vital sign measurements, clinical safety laboratory evaluations, infusion-related reactions, ECGs, and diary entries, to capture adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs). The National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.5.0 was used for grading toxicities, with the exception of cytokine release syndrome, which was graded according to a separate scale by Lee et al.25 Tumor responses per RECIST V.1.1 were assessed every 12 weeks while on study, using radiologic, clinical or photographic assessments of tumor burden. Patients who had an evaluable screening/baseline tumor assessment and at least one evaluable post-treatment tumor assessment were considered evaluable for efficacy.

Flow cytometry and chemokine/cytokine assessments

Blood samples were collected pre-dose and 24 hours after the first and third doses of cavrotolimod, the latter given with the first dose of ICI. The samples were interrogated with flow cytometry to assess the activation of 18 subtypes of immune cells. Serum concentrations of 12 chemokines/cytokines related to cavrotolimod’s mechanism of action were measured using a Randox Investigator26 panel and ELISA. Flow cytometry, chemokine/cytokine results are included in the online supplemental material. 54 of the 58 patients gave at least one blood sample for these analyses.

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples were collected pre-dose and up to 24 hours following the first and third doses of cavrotolimod to assess plasma drug concentrations using a validated assay. All patients contributed at least one sample for PK analysis.

Tumor biopsies

Tumor tissue samples were collected from cavrotolimod-injected and non-injected lesions with punch or core needle biopsies. Biopsies were collected at three time points: (1) prior to the initiation of study treatment, (2) 1 week after the second cavrotolimod administration (ie, on the same day of, but before, the third cavrotolimod and first anti-PD-1 antibody doses), and (3) 1 week after the fifth dose of cavrotolimod (ie, on the same day of, but before, the sixth cavrotolimod and second anti-PD-1 antibody doses). The biopsies provided data from 18 paired samples for cavrotolimod alone and 14 paired samples for cavrotolimod combined with anti-PD-1 therapy.

Selected gene-expression profiling of RNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor biopsies was performed by NeoGenomics Laboratories with NanoString nCounter PanCancer Immune Profiling panel of 770 genes. Differential gene expression and cell quantification data were generated and analyzed with nSolver V.4.0 Advanced Analysis software.

Statistics

The study had no formal statistical hypotheses related to safety, PK, pharmacodynamics, or efficacy. Descriptive statistics are reported for data regarding patient characteristics, serum chemokine/cytokine induction and lymphocyte activation, and differentially expressed genes. Statistical analysis of the cell activation and chemokine/cytokine data were performed with an ordinary two-way analysis of variance and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism V.9.4. Differential expression statistics were calculated by nSolver Advanced Analysis software. Unadjusted p values for gene expression changes are reported herein. Application of the Benjamini-Yekutieli adjustment to the analysis resulted in no gene expression changes at the level of p<0.05. Immune cell population changes were assessed with paired two-sided t-tests.

Additional methodological information is included in the online supplemental material.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between February 19, 2019 and December 29, 2021, 58 patients with advanced cancer were enrolled across 17 sites. The dose escalation stage of the study enrolled 20 patients with a variety of tumor types, 19 of whom had previously received an anti-PD-(L)1 antibody and 17 had experienced progressive disease (PD) on the prior anti-PD-(L)1 regimen. Of the two patients not experiencing PD on the prior anti-PD-(L)1 regimen, one had an initial complete response (CR) on pembrolizumab monotherapy followed by progression once off treatment, while the other patient lacked evaluable disease while receiving ipilimumab plus nivolumab. 19 of 20 patients had metastatic disease at the time of enrollment. 38 patients were enrolled in the dose expansion portion of the trial where all patients were required to have documented (confirmed) progression on an anti-PD-1 antibody as the most recent therapy prior to study entry. Detailed information about the patient characteristics is presented in table 1 and online supplemental material table 1.

Safety

In the dose escalation cohorts, 17 of 20 (85%) patients experienced cavrotolimod-related treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), the vast majority of which were grade (G) 1 or 2 (online supplemental material table 2). G3 cavrotolimod-related AEs were observed in two patients. One patient receiving 32 mg cavrotolimod experienced G3 TEAE of agitation, and another patient experienced G3 injection site reactions (ISRs). These reactions occurred after the DLT periods, and both led to cavrotolimod discontinuation. No G4 or G5 cavrotolimod-related AEs were reported in the dose escalation. The most commonly reported (>20%) cavrotolimod-related AEs were ISRs (50%), fatigue (40%), injection site pain (40%), nausea (30%), chills (30%), fever (25%), and flushing (25%) (online supplemental material table 3). In the dose range from 2 mg to 16 mg, there was no clear dose-dependent relationship in the incidence, frequency, or severity of influenza-like symptoms (defined as influenza-like illness, fever, chills, fatigue, nausea or myalgia) or ISRs, but the patients in the 32 mg dose cohort experienced the highest incidence and greatest frequency of those two TEAEs. No cavrotolimod-related SAEs were reported in the dose escalation cohorts. In the dose escalation, 13 patients (65%) experienced a total of 31 pembrolizumab-related TEAEs. The most common pembrolizumab-related TEAEs were fatigue (30% of patients), pruritus (15%), and nausea (10%), consistent with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

In the dose expansion cohorts, 35 of 38 (92%) patients experienced TEAEs related to cavrotolimod (online supplemental material table 4). The most commonly reported (>20%) preferred terms were fatigue (63%), ISRs (61%), chills (53%), fever (50%), diarrhea (26%), nausea (26%), and influenza-like illness (21%) (online supplemental material table 5). G3 or 4 AEs related to cavrotolimod were observed in 12 (32%) patients. Out of the 397 reported cavrotolimod-related AEs, 19 (5%) were G3 and 1 (0.3%) was G4. The G4 AE was hypotension, which was observed after the first dose of cavrotolimod, leading to discontinuation. Five patients experienced AEs leading to cavrotolimod dose reduction. Patients requiring dose reductions were more common in the SC dosing cohort (3 of 8 patients) compared with the IT-dosed cohorts (2 of 30 patients). Five patients experienced SAEs considered to be related to cavrotolimod, including asthenia, chills, fatigue, hypotension, immediate post-injection reaction, influenza-like illness, ISR, nausea, and fever. Hypotension and fever led to cavrotolimod discontinuation in two of those patients. Antihistamine premedication before cavrotolimod injection was employed to minimize the risk of immediate post-injection reactions. Across the MCC expansion cohorts, and melanoma and SC exploratory expansion cohorts (n=33), 22 patients (67%) experienced a pembrolizumab-related TEAE. The only TEAE occurring in at least 10% of patients was fatigue (36%).

In the CSCC expansion cohort, three patients (60%) had TEAEs attributed to cemiplimab. These were chills, hypoalbuminemia, hypocalcemia, lymphopenia, presyncope, pneumonitis, thyroid stimulating hormone decrease, nausea, and fever (all 20%). The AE profiles of these agents, when administered in combination with cavrotolimod, were generally consistent with those observed with each agent as monotherapy.

Antitumor activity

Dose escalation

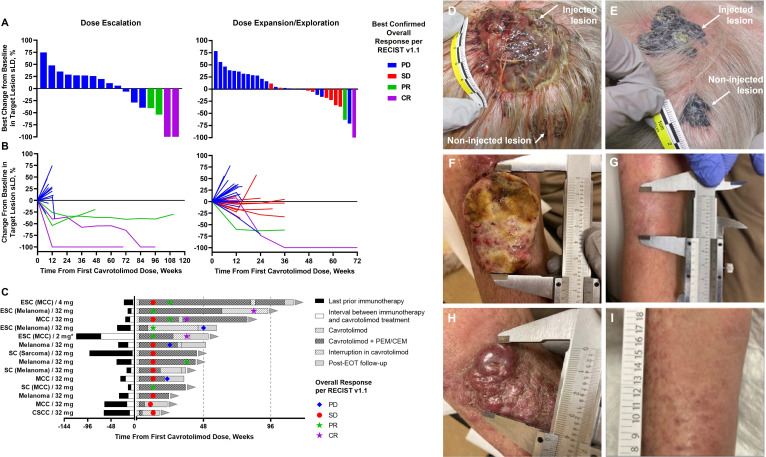

Of the 20 patients dosed with cavrotolimod in the dose escalation, 19 were deemed evaluable for efficacy, that is, they had an evaluable baseline tumor assessment, and at least one post-treatment assessment. The non-evaluable patient had discontinued the study after the first dose of cavrotolimod due to an SAE of treatment-unrelated aspiration pneumonia. Confirmed objective responses per RECIST V.1.1 were observed in 4 of 19 (21%) patients, including 2 patients with CR (1 MCC, 1 melanoma) and 2 with partial response (PR; 1 MCC, 1 melanoma) (figure 2A, table 2 and online supplemental material table 6). The other patients experienced PD as the best response. In the highest cavrotolimod dose cohort (32 mg, which was also selected for use in the dose expansion cohorts), there were 2 out of 6 (33%) patients with confirmed objective responses, reflecting 1 PR and 1 CR (both melanoma). All four responses were durable with a median duration of response of 73 weeks (range 38–88+ weeks). Three of these four responding patients had previously progressed on anti-PD-1 therapy prior to trial enrollment.

Figure 2. Antitumor activity of cavrotolimod in combination with pembrolizumab or cemiplimab. (A) Best change from baseline of the sum of longest diameters (sLD) for target tumors by study phase (dose escalation, left panel; dose expansion, right panel). (B) Individual percent change from baseline in the sLD of target lesions over time. (C) Duration of treatment, onset, and duration of disease control. The cohort, tumor type (if not indicated by the cohort name) and dose are given. Photos: a patient in their 70s who had experienced PD on prior pembrolizumab monotherapy with melanoma metastases on the scalp. Cavrotolimod was injected into only the larger of the two pictured lesions at baseline (D) and at study week 12 (E). Regression of both the injected and non-injected tumors was observed at week 12. This patient went on to a CR at week 84. A patient in their 90s with three MCC lesions on the right arm after PD on prior pembrolizumab monotherapy. Cavrotolimod was injected into two lesions, one of which is pictured in (F). One injected lesion completely regressed by week 12 (not pictured) while the other completely regressed by week 36 (G). The non-injected lesion (pictured at baseline in (H)) completely regressed by week 24 (I). This patient experienced a CR at week 36. CEM, cemiplimab; CR, complete response; EOT, end of treatment; ESC, dose escalation cohort; MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma dose expansion cohort; Melanoma, melanoma dose expansion cohort; PD, progressive disease; PEM, pembrolizumab; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; SC, subcutaneous dose expansion cohort; SD, stable disease. *This patient was not anti-programmed death 1 antibody refractory prior to study enrollment.

Table 2. Confirmed best overall tumor response per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1.

| Dose escalation cohorts | Dose expansion cohorts | Study overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | MCC | CSCC | Melanoma | SC | ||

| Evaluable patients, n | 19 | 11 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 51 |

| CR, n (%) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (5.9) |

| PR, n (%) | 2 (10.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 3 (5.9) |

| SD, n (%) | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (25.0) | 8 (15.7) |

| PD, n (%) | 15 (78.9) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (75.0) | 6 (66.7) | 5 (62.5) | 37 (72.5) |

| ORR, n (%) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 6 (11.8) |

| DCR, n (%) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (37.5) | 14 (27.5) |

CR, complete response; CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; DCR, disease control rate; MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma; n, number of patients; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SC, subcutaneous; SD, stable disease.

The 32 mg dose was selected for the expansion cohorts based on a combination of efficacy, safety, and pharmacodynamic data. AEs at this dose were generally low grade, and two of six patients in the 32 mg dose escalation cohort achieved confirmed objective responses. Additionally, the levels of blood cytokine and chemokine emission, as well as lymphocyte activation, were similar for 32 mg compared with 16 mg (vide infra), suggesting that further dose escalation was unlikely to provide greater pharmacodynamic effects.

Dose expansion

A total of 38 patients, all with documented progression on PD-(L)1 therapy as the most recent line of treatment, were dosed in the dose expansion stage. 32 were considered evaluable for an efficacy assessment. Two confirmed responses were observed: one CR in a patient with MCC receiving IT cavrotolimod and one PR in another patient with MCC receiving SC cavrotolimod, with ongoing response durations of 49 and 24 weeks, respectively, at the time of their final on-study disease assessment. Non-injected target lesions responded in both these patients (the patients in the SC cohort were not dosed IT). SD was observed in 2 of 11 (18%) evaluable patients in the MCC cohort, 1 of 4 (25%) evaluable patients in the CSCC cohort, 3 of 9 (33%) evaluable patients in the melanoma cohort, and in 2 of 8 (25%) evaluable patients in the SC cohort (sarcoma and melanoma), table 2. The median duration of SD for these eight patients was 24 weeks (range 11–35+ weeks), with disease control ongoing in six patients as of their final assessment. Disease control rate (DCR), defined as the proportion of patients with CR, PR or SD as the best response, was 31% (10 of 32). Progression-free survival and immature overall survival Kaplan-Meier plots for the MCC and CSCC dose expansion cohorts are presented in online supplemental material figure 2, while landmark analyses for all groups are presented in online supplemental material tables 7–10.

In responding patients, tumor volumes often continued to shrink over time (figure 2B), with disease assessments often showing SD prior to an objective response (figure 2C). Regression of both injected and non-injected lesions was observed (online supplemental material figure 3). These systemic (abscopal) effects beyond the injected tumor(s) were observed in both non-injected regional and distant tumors. A representative example is the case of a patient in their 70s with melanoma metastases on the scalp who had experienced PD on prior pembrolizumab monotherapy. Cavrotolimod was injected into only the larger of the two pictured lesions (figure 2D). Regression of both the injected and non-injected tumors was observed at week 12 (figure 2E), ultimately resulting in a CR at week 84. This patient’s duration of response was 86 weeks, with the final on-study disease assessment showing a continued CR.

A CR was also observed in a patient in their 90s with multifocal MCC after developing PD on prior pembrolizumab monotherapy. This patient had three lesions on the right arm, and cavrotolimod was injected into two lesions. One injected lesion completely regressed by week 12 (not pictured), while the other injected lesion completely regressed by week 36 (baseline and week 36 pictured in figure 2F,G, respectively), and the non-injected lesion completely regressed by week 24 (baseline and week 24 pictured in figure 2H,I, respectively).

In summary, cavrotolimod in combination with an anti-PD-1 antibody produced objective responses in 6 (12%) and SD in 8 (16%) of 51 evaluable patients on this study, leading to a DCR of 27% (14/51). Across all study cohorts, the overall response rates for evaluable patients with melanoma, MCC and CSCC were 9%, 27%, and 0%, respectively, while the DCRs were 27%, 33%, and 17%, respectively.

Pharmacokinetics

IT administration of cavrotolimod resulted in peak plasma concentrations approximately 1 hour post-dose, followed by a rapid decline. During the dose escalation phase, plasma concentrations increased roughly linearly with dose (online supplemental material figure 4). In the dose expansion cohorts, patients who received cavrotolimod SC exhibited markedly lower plasma exposure compared with those dosed IT (online supplemental material figure 5). Cavrotolimod PK measured at study week 1 (prior to combination therapy) was qualitatively similar to those observed at study week 3 (the start of combination therapy).

Pharmacodynamic assessments

Serum chemokine/cytokine induction and lymphocyte activation are expected effects of TLR9 agonism and pDC activation.7 We hypothesized that cavrotolimod activates pDCs, leading to cytokine and chemokine release, lymphocyte activation, and inflammatory signaling that promotes immune cell recruitment to the TME. To evaluate this mechanism, we measured serum cytokine and chemokine levels, assessed peripheral lymphocyte activation, and performed gene expression analyses on both cavrotolimod-injected and non-injected tumors.

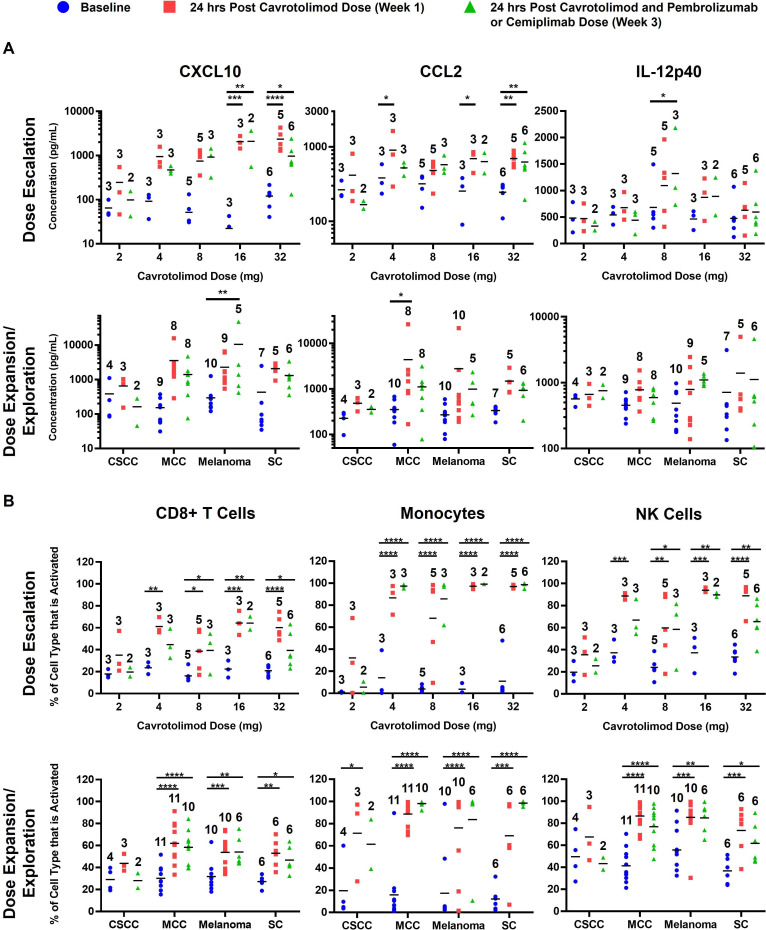

Serum chemokine/cytokine induction and lymphocyte activation

Cavrotolimod increases Th1-type cytokines and chemokines and activates immune cell populations. Among the 12 cytokines/chemokines measured, CXCL10, CCL2, and IL-12p40 are highlighted for their antitumor potential (figure 3A). During dose escalation, CXCL10 and CCL2 were robustly induced at 16 and 32 mg, while IL-12p40 showed the strongest induction at 8 and 16 mg. Similar patterns were seen in the MCC, melanoma, and SC cohorts. The full cytokine/chemokine results are available in the online supplemental data.

Figure 3. Peripheral blood cytokine/chemokine levels are increased and lymphocytes are activated after intratumor or SC cavrotolimod. (A) Chemokine/cytokine concentrations and (B) lymphocyte activation by dose escalation level and cohort and in the blood before and after cavrotolimod alone or in combination with an anti-programmed death 1 antibody. The horizontal bar in each group represents the group mean. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 versus baseline. Ordinary two-way analysis of variance and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test of post-dose samples versus baseline were used. The number above each bar represents the number of patient samples in that group. CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma; NK, natural killer; SC, subcutaneous.

Flow cytometry analyses suggested that cavrotolimod activated monocytes, NK cells, and CD8+ T cells 24 hours post-dose (figure 3B), consistent with previous data. Data on 15 other immune cell populations are available in the online supplemental data. Greater immune cell activation was observed at 16 mg and 32 mg doses. Similar activation was noted in the MCC, melanoma, and SC cohorts, while the CSCC cohort showed weaker activation.

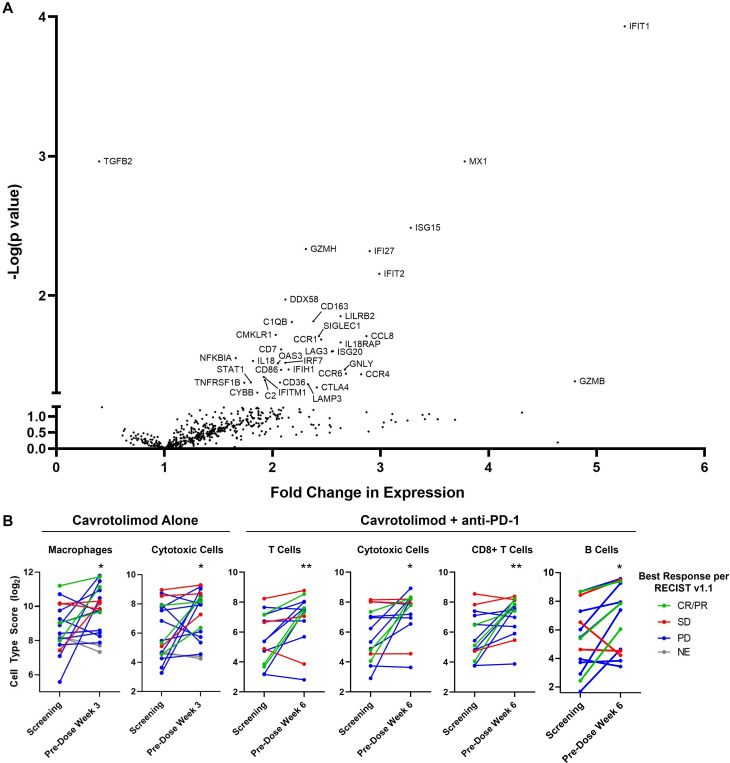

Induction of tumor inflammation and immune cell composition changes

Two doses of IT cavrotolimod induced a type 1 IFN response27 in the injected tumors, with upregulation in IFN pathway genes, transcription factors, antiviral proteins, immune checkpoints including CTLA-4 and LAG-3, cytokines/chemokines, granzymes and a costimulatory protein (all p<0.05, figure 4A). These changes are consistent with those observed after IT injection of tilsotolimod, another TLR9 agonist.21 Further, two IT doses of cavrotolimod reduced expression of TGFB2 (p=0.0011), whose expression is thought to drive tumor cell proliferation and promote immune evasion.28 In addition, changes in tumor immune cell population can be inferred from the gene expression signatures in this assay.29 Cavrotolimod injections yielded a twofold increase in cytotoxic cells (an analysis category consisting of NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK/T cells) and macrophages (figure 4B).

Figure 4. Differential gene expression and immune cell composition changes elicited by cavrotolimod. (A) Volcano plot of differential gene expression comparing cavrotolimod-injected tumor RNA derived from lesions at screening and pre-dose week 3. Datapoints corresponding to differentially expressed genes (unadjusted p<0.05) are labeled with the gene name abbreviation. N=18 pairs of samples. (B) Changes in immune cell score in cavrotolimod-injected lesions. p<0.05, **p<0.01. Paired two-tailed t-test versus baseline. Cell abundance estimates from these gene expression signatures, referred to as cell type scores, are presented in log2 scale so an increase of one unit corresponds to a doubling in abundance. N=18 and 14 paired biopsies for cavrotolimod alone, and cavrotolimod plus anti-PD-1, respectively. CR, complete response; NE, not evaluable; PD, progressive disease; PD-1, programmed death 1; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; SD, stable disease.

The second post-treatment biopsy results (after five doses of IT cavrotolimod plus one dose of an anti-PD-1 antibody) show some genes were expressed at the second biopsy time point that were not at the first biopsy. These transcripts were a marker of activated lymphocytes, other immune checkpoints including ICOS, KLRG1, and TIGIT, a costimulator, other chemokines/cytokines, and another granzyme (all p<0.05, online supplemental material figure 6). Increases in cytotoxic cells, T cells, CD8+ T cells, and B cells were also observed (p<0.05, figure 4B). On average, the patients with tumor responses tended to have greater fold increases in levels of cytotoxic cells, T cells, and CD8+ T cells compared with those experiencing PD.

Compared with injected lesions, non-injected lesions biopsied at screening and at the pre-dose time point in week 3 showed fewer statistically significant changes in gene expression (online supplemental material table 11). By week 6, the alterations observed were primarily limited to a 1.5-fold to 3-fold upregulation of a small number of IFN pathway genes (online supplemental material table 12). A twofold increase in B cells was found in non-injected lesions at week 3 (online supplemental material figure 7 p<0.05). This small gene expression and immune cell content change may be due to the timing of the biopsy, which was 1 week after the most recent dose of the TLR9 agonist (and 3 weeks after the anti-PD-1 antibody dose) or may reflect limited pharmacodynamic changes in non-injected lesions.

Discussion

This phase 1b/2 study represents the first clinical investigation of cavrotolimod, a novel spherical nucleic acid configuration of TLR9 agonistic oligonucleotides, in patients with advanced cancer. Our results suggest that cavrotolimod has a manageable safety profile and can lead to antitumor immune responses and clinical benefit in a subset of patients with advanced melanoma, CSCC and MCC, including those who had progressed on prior anti-PD-(L)1 regimens.

Both IT and SC administration of cavrotolimod alone or in combination with PD-1 blockade was safe and feasible in a multicenter setting. Observed AEs were mostly low grade and largely expected of TLR agonism. No DLTs were observed with cavrotolimod alone, or in combination with pembrolizumab. Most cavrotolimod-related AEs such as influenza-like symptoms and ISRs were transient and were not serious or severe. Importantly, there was no increase in the incidence of immune-related AEs with the addition of cavrotolimod to anti-PD-1 agents.

Cavrotolimod in combination with an anti-PD-1 antibody produced objective responses in 6 (12%) and SD in 8 (16%) of 51 evaluable patients on this study, leading to a DCR of 27% (14/51). Importantly, all eight patients with SD and five of six responding patients had previously progressed on PD-(L)1 blockade. Antitumor activity was observed not only in cavrotolimod-injected lesions, but also in distant, non-injected lesions, suggesting successful induction of systemic immune responses against the tumors. The objective responses were typically durable, lasting from 24 to 88+ weeks, with five patients having ongoing responses as of their final on-study disease assessment. Similarly, six of eight patients with SD were progression-free as of their last on-study disease assessment.

The AEs, clinical responses and disease control are supported by correlative data which confirmed on-target effects of cavrotolimod with TLR9 agonism to produce immune activation in the blood as assessed by gene expression analysis, changes in chemokines/cytokines and lymphocyte activation. In addition, gene expression analysis of transcripts derived from paired tumor biopsy tissues suggested that cavrotolimod induced IFN-mediated tumor inflammation, costimulatory protein and granzyme expression, and increased the levels of some lymphocyte populations. However, no gene signature that predicted responses was found in this small cohort of benefiting patients.

Our results add to the rapidly growing evidence for the utility of IT immunotherapies, specifically TLR9 agonism, in reversing immune evasion mechanisms in a subset of patients with anti-PD-(L)1 refractory cancers. Other IT TLR9 agonists, including vidutolimod and SD-101, have been combined with anti-PD-1 antibodies and evaluated in patients with skin cancer who have progressed on anti-PD-1 therapy. Vidutolimod combined with pembrolizumab achieved an objective response rate (ORR) of 25% (11 of 44),19 while SD-101 with pembrolizumab showed an ORR of 21% (6 of 29) in patients with melanoma.30 Despite their IT administration, responses with these agents can be systemic and durable, typically with minimal additional systemic toxicities, and exhibit comparable response rates with systemic therapies in this challenging setting. This is a contrast to existing combination regimens such as anti-PD-1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 antibodies (eg, nivolumab with ipilimumab), anti-PD-1 blockade with lenvatinib, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy that have demonstrated encouraging response rates. However, these approaches are often associated with significant toxicity and tolerability challenges,31 32 and TIL therapy, in particular, is logistically demanding and frequently toxic.33 Further, the combination intravenous therapy of relatlimab plus nivolumab, which is approved for previously untreated advanced melanoma, was associated with ORRs of up to only 12% in patients with melanoma who had progressed on one or more anti-PD-1 regimens.34

Beyond the refractory setting, the activity of IT agents plus anti-PD-(L)1 combination raises the possibility of using these agents in treatment-naive patients, including both metastatic and neoadjuvant settings, to enhance efficacy without additional systemic toxicity. However, only a subset of patients respond to TLR9 agonist therapy in combination with ICIs, suggesting a need for predictive biomarkers to fully harness the benefit of this class of drugs. Notably, RNA sequencing data from tumor biopsies of vidutolimod-treated patients identified two transcriptional signatures associated with the antitumor activity of vidutolimod, suggesting the potential for predictive biomarker application in TLR9 agonist therapies.35 Larger datasets and improving technology may help identify predictive biomarkers for cavrotolimod in the future.

Conclusions

Cavrotolimod, alone or in combination with anti-PD-1 antibodies, elicited immune activation consistent with TLR9 agonism, demonstrated manageable AEs, and resulted in antitumor responses in anti-PD-(L)1 refractory solid tumor populations. This work warrants further study of cavrotolimod for treatment of solid tumors including cutaneous malignancies. Further research should focus on identifying predictive biomarkers, exploring combinations with other ICIs and/or applications to different tumor types to fully realize the therapeutic potential of cavrotolimod.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for participating in the study.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by Exicure, Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board, Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board, Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Northwestern University Institutional Review Board, U.T. M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board, University of Iowa IRB-01, Human Subjects Office, University of Miami, Institutional Review Board, US Oncology, Inc., Institutional Review Board, Western Institutional Review Board. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was first published online. The supplemental data has been updated.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2542–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, et al. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:341–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2500–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krieg AM. CpG still rocks! Update on an accidental drug. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012;22:77–89. doi: 10.1089/nat.2012.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krieg AM. Development of TLR9 agonists for cancer therapy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1184–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI31414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–95. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:709–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zoglmeier C, Bauer H, Nörenberg D, et al. CpG Blocks Immunosuppression by Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor-Bearing MiceIn Vivo TLR9 Activation Blocks Suppression by MDSC. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1765–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon S, Labarriere N. PD-1 expression on tumor-specific T cells: Friend or foe for immunotherapy? Oncoimmunology. 2017;7:e1364828. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1364828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi CHJ, Hao L, Narayan SP, et al. Mechanism for the endocytosis of spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7625–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305804110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad-Nejad P, Häcker H, Rutz M, et al. Bacterial CpG-DNA and lipopolysaccharides activate Toll-like receptors at distinct cellular compartments. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1958–68. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<1958::AID-IMMU1958>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radovic-Moreno AF, Chernyak N, Mader CC, et al. Immunomodulatory spherical nucleic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3892–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502850112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nallagatla S, Anderson BR, Anantatmula S, et al. Abstract 4706: Spherical nucleic acids targeting toll-like receptor 9 enhance antitumor activity in combination with anti-PD-1 antibody in mouse tumor models. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4706. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-4706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mix S, Schroff M, Daniel WL. Cavrotolimod, a Nanoparticle Toll-like Receptor 9 Agonist, Inhibits Tumor Growth and Alters Immune Cell Composition in Mouse Models of Skin Cancer. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2023;6:2682–96. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.2c05121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniel WL, Lorch U, Mix S, et al. A first-in-human phase 1 study of cavrotolimod, a TLR9 agonist spherical nucleic acid, in healthy participants: Evidence of immune activation. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1073777. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1073777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna E, Abadi R, Abbas O. Imiquimod in dermatology: an overview. Int J Dermatol . 2016;55:831–44. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia S, Miller NJ, Lu H, et al. Intratumoral G100, a TLR4 Agonist, Induces Antitumor Immune Responses and Tumor Regression in Patients with Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:1185–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribas A, Medina T, Kirkwood JM, et al. Overcoming PD-1 Blockade Resistance with CpG-A Toll-Like Receptor 9 Agonist Vidutolimod in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:2998–3007. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribas A, Medina T, Kummar S, et al. SD-101 in Combination with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Melanoma: Results of a Phase Ib, Multicenter Study. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1250–7. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haymaker C, Johnson DH, Murthy R, et al. Tilsotolimod with Ipilimumab Drives Tumor Responses in Anti-PD-1 Refractory Melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1996–2013. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohlhapp FJ, Kaufman HL. Molecular Pathways: Mechanism of Action for Talimogene Laherparepvec, a New Oncolytic Virus Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1048–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kluger HM, Tawbi HA, Ascierto ML, et al. Defining tumor resistance to PD-1 pathway blockade: recommendations from the first meeting of the SITC Immunotherapy Resistance Taskforce. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000398. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee DW, Gardner R, Porter DL, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood. 2014;124:188–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-552729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saluk J, Hoppensteadt D, Syed D, et al. Biomarker profiling of plasma samples utilizing RANDOX biochip array technology. Int Angiol . 2017;36:499–504. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.17.03854-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–86. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Martin R, Haendler B, Hofer-Warbinek R, et al. Complementary DNA for human glioblastoma-derived T cell suppressor factor, a novel member of the transforming growth factor-beta gene family. EMBO J. 1987;6:3673–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danaher P, Warren S, Dennis L, et al. Gene expression markers of Tumor Infiltrating Leukocytes. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:18. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribas A, Mehmi I, Medina T, et al. Phase Ib/II study of the combination of SD-101 and pembrolizumab in patients with advanced melanoma who had progressive disease on or after prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:viii451–2. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy289.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arance A, de la Cruz-Merino L, Petrella TM, et al. Phase II LEAP-004 Study of Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab for Melanoma With Confirmed Progression on a Programmed Cell Death Protein-1 or Programmed Death Ligand 1 Inhibitor Given as Monotherapy or in Combination. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:75–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monberg TJ, Borch TH, Svane IM, et al. TIL Therapy: Facts and Hopes. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29:3275–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ascierto PA, Lipson EJ, Dummer R, et al. Nivolumab and Relatlimab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma That Had Progressed on Anti–Programmed Death-1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy: Results From the Phase I/IIa RELATIVITY-020 Trial. JCO. 2023;41:2724–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Zhao L, Zheng P, et al. Abstract LB107: Novel transcriptional signatures associated with antitumor activity in vidutolimod (vidu)-treated patients (pts) with anti-PD-1-refractory melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Cancer Res. 2022;82:LB107. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2022-LB107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.