Abstract

Leiomyoma is the most common benign tumor of the female genital tract. It may develop subserous, intramural, or submucous. The submucous subtype accounts for 5% of all cases, and it may become pedunculated or prolapse outside the uterine cavity, resulting in vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain, significantly impacting the quality of life, especially for larger leiomyomas. The management of such cases may require vaginal access, which may disrupt hymen integrity and is not accepted in conservative communities. Here, we present an innovative hymen-conserving Laparoscopic-And-Suprapubic Hysteroscopic Approach (LASHA) via anterior colpotomy and myomectomy for endometrial cavity exploration and management of a prolapsed pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma in a virgin patient. A 30-year-old virgin presented to the clinic with heavy menstrual bleeding for the past 6 months. Abdominal ultrasound showed an enlarged uterus with multiple uterine myomas; the largest one was in the cervicovaginal zone, filling the vagina, showing a solid hypo-echoic mass, well delineated, filling the vaginal margins, and suggesting a prolapsed, pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma (5.7x6.6x 8.3 cm). Other subserosal and intramural myomas ranged from 2 to 7 cm. The LASHA approach was decided to preserve the hymen’s integrity based on the patient’s desire, resulting in a successful tumor excision. In summary, the LASHA approach of a prolapsed, pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma is an adequate, safe, and socially accepted alternative in conservative societies. Therefore, the indications of laparoscopy could be extended to endometrial cavity exploration and managing cervicovaginal leiomyoma in virgin women rejecting vaginal approaches. However, this technique necessitates adequate equipment and skills in laparoscopic surgery.

Keywords: leiomyoma, hymen, myomectomy, laparoscopy, hysteroscopy

Plain Language Summary

Uterine fibroids (also called leiomyomas) are a common benign cancer among women. It can develop in different parts of the uterus. Nevertheless, uterine fibroids, which develop inside the uterine cavity, might grow, forming a stalk and go down outside the uterus, leading to excessive bleeding and lower abdominal pain. In such cases, the doctors surgically remove the fibroids through the vagina. However, this approach might affect hymen integrity, which is not accepted in conservative communities. Therefore, we describe a novel hymen-conserving Laparoscopic-And-Suprapubic Hysteroscopic Approach (LASHA) for exploring and treating large pedunculated fibroids that have extended to the vagina in a virgin patient. The patient was 30 years old and presented to our clinic complaining of heavy menstrual bleeding for the past six months. By ultrasound examination, we found a distended uterus containing multiple fibroids, with the largest one being a pedunculated fibroid that had extended into the vagina. We were able to successfully remove these fibroids using the LASHA approach, emphasizing that this technique is feasible in conservative communities for virgin patients who refuse to perform surgeries through the vagina to avoid the disruption of their hymen. After the operation, the patient recovered well with minimal bleeding and pain and was discharged 24 hours later. At follow-up, she clarified that her symptoms had improved, and she was satisfied with the outcome of the operation.

Introduction

Uterine leiomyoma is the most prevalent benign tumor of the female genital tract. It affects about 70% and 80% of the white and the African women during their lifetime, respectively. The majority of the patients are asymptomatic. However, 30% of them may experience various symptoms, including abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic or back pain, constipation, urinary frequency, or infertility.1

Leiomyoma may develop subserous, intramural, or submucous. About 5% of leiomyoma is submucous, of which 1.3%–2.5% are pedunculated and may prolapse outside the uterine cavity in the cervix, vagina, or outside the vagina and the introitus.2,3 Furthermore, prolapsed leiomyoma may be complicated by necrosis due to reduced blood supply from the pedicle, sepsis, or uterine inversion.3,4

Prolapsed submucosal leiomyomas may be asymptomatic or present with vaginal bleeding or discharge or pelvic pain.5 Additionally, it might be complicated with urinary retention, obstructive uropathy, renal dysfunction, massive bleeding, hemodynamic shock, or chronic uterine inversion.6–9

Medical therapy is usually not effective, with a high failure rate. Transvaginal techniques are the classical approaches for prolapsed submucosal leiomyomas. Ultimately, the main treatment for women with leiomyoma is surgical, including either hysterectomy or myomectomy. However, hysterectomies are more suitable for those who completed their families; otherwise, vaginal myomectomy is an alternative uterus-conservative technique. However, prolapsed pedunculated submucosal uterine leiomyoma might be associated with intraoperative bleeding that could be controlled by hysteroscopy. Therefore, combining vaginal myomectomy and operative hysteroscopy is an optimal approach to avoid intra-operative complications and decrease the risk of recurrence.10–12

Hysteroscopic myomectomy generally has a low complication rate. However, there are some perioperative risks that may arise, including excessive fluid absorption, injury to the bladder and bowel, excessive bleeding, and uterine perforation. These complications are primarily associated with the process of cervical dilation.13 The use of hypotonic solution during uterine distension may lead to hyponatremia and neurological complications, or circulatory overload and pulmonary edema.14

Furthermore, intrauterine adhesions are a major postoperative complication. The application of anti-adhesion gel or intrauterine devices with oxidized regenerated cellulose and silicon immediately after the surgery is crucial.15–17

Additionally, minimally invasive myomectomy (MIM), including laparoscopic and robotic-assisted techniques, was shown to be a feasible approach for leiomyoma. The proportion of MIM has increased from 6% in 2009 to 89.5% in 2019, as it offers lower blood loss, post-operative pain, shorter hospital stays, and reduced morbidity compared with open surgery. However, the decision to perform MIM is influenced by several factors, including the number and position of leiomyoma, obesity, the higher costs, and challenging surgical techniques.18,19

Dolmans et al recommend avoiding the laparoscopic approach when there are more than four fibroids located in different areas of the uterus that require multiple incisions, when the fibroids are large (larger than 10–12 cm), or when the fibroids are situated in an intra-ligamental location.20

Gitas et al suggest that the laparoscopic approach is only suitable for a uterus measuring less than 16 weeks’ gestational size, with a maximum of five fibroids, and no individual fibroid larger than 15 cm. A diameter of 12 cm or more in the largest myoma would significantly increase the risk of surgical complications.21 Complications of laparoscopic myomectomies include conversion to hysterectomy, longer operative times, uterine rupture, and morcellation-related complications such as pelvic adenomyosis and parasitic leiomyomas.22–26

Although robotically assisted myomectomy offers more advantages than conventional laparoscopic myomectomy, particularly for technically challenging cases, it is associated with high financial costs, including increased hospital and professional charges as well as higher hospital reimbursement rates.27–29

However, these vaginal procedures may disrupt hymen integrity for virgin and unmarried women, which is a sign of sexual purity and dignity in certain societies, raising some social concerns for the patient and the physician.

Consequently, laparoscopic-hysteroscopic supra-pubic access (LASHA) is a novel, hymen-conserving technique. Here, we present the management of a virgin case with a prolapsed, pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma without disruption of hymen integrity.

Case Report

A 30-year-old, nulliparous virgin, class 3 obese patient (BMI: 44.3) presented to the gynecology clinic with heavy menstrual bleeding for the past 6 months and mild anemia (hemoglobin (Hb): 10 g/dL) that was corrected with oral iron tablets. Also, she was complaining of watery yellow-pinkish vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, persistent menstrual-type cramps, and chronic fatigue.

Her past medical history included anemia that required multiple blood transfusions. The patient was on medical treatment for hypothyroidism. Otherwise, her medical, gynecological, and family history were unremarkable. She has never been sexually active.

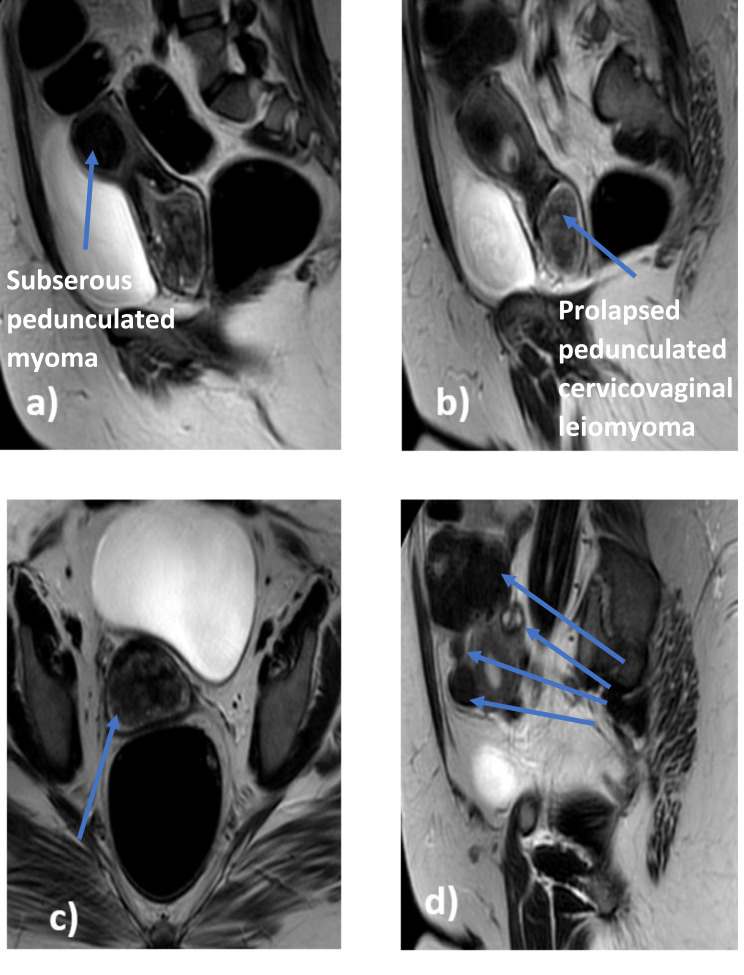

The vulvar area appeared normal during the gynecologic examination, with an intact annular hymen. The rectal examination indicated significant fullness in the vagina. Abdominal ultrasound examination and contrast MRI have revealed six leiomyomas. The largest one was intra-cavitary (FIGO 0) solid hypo-echoic in the cervicovaginal zone, well delineated, arising from the right side of the endometrial cavity and protruding from the cervical canal to the vagina and has a vascular pedicle suggestive of prolapsed pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma (5.7x6.6x 8.3 cm). A large pedunculated subserosal leiomyoma (7.3x6.8x6 cm) was located at the uterine fundus (FIGO 7). Additionally, there were two small intramural leiomyomas (FIGO 3 and FIGO 4), along with two small fundal subserosal leiomyomas (FIGO 5) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Subserous pedunculated myoma measuring (7.3x6.8x6 cm) located at the uterine fundus (FIGO 7). (b) The prolapsed cervicovaginal leiomyoma measuring (5.7x6.6x8.3 cm) arising from the right side of the cervix and protruding from the cervical canal to vagina (FIGO 0). (c)The coronal view demonstrating the distortion of the uterine contour. (d) Showing the multiple fibroids varying in locations (intramural and subserous) and also in their sizes, two small intramural leiomyomas (FIGO 3 and FIGO 4), along with two small fundal subserosal leiomyomas (FIGO 5).

Before her presentation to the clinic, the patient was informed that treatment options, including the vaginal approach, may disrupt the integrity of her during the operation but that a hymenal repair could be performed immediately after the intervention if desired. However, the patient and her family strongly refused the vaginal approach to preserve hymenal integrity.

The other options were open myomectomy or hysterectomy, but both options posed risks of post-operative adhesions, potential impacts on future fertility, and cosmetic concerns. Moreover, the hysteroscopic approach was refused by the patient and her family due to concerns about hymenal integrity and cultural beliefs, which emphasize the importance of maintaining virginity as a symbol of modesty and familial honor. Therefore, the patient and her family opted for a minimally invasive approach. Consequently, our team proceeded with the LASHA approach for endometrial cavity exploration.

The findings of the routine preoperative laboratory tests were within the normal range. After removing the other non-pedunculated myomas, our team proceeded to the LASHA approach for endometrial cavity exploration.

The laparoscopic procedure began by establishing a pneumoperitoneum using a Veress needle placed above the umbilicus, which achieved an intra-abdominal pressure of 15 mmHg. A central supraumbilical 10 mm port was first inserted for the laparoscope, followed by three 5 mm lateral accessory trocars placed under direct visualization. These accessory ports were strategically placed lateral to the deep inferior epigastric arteries and were used to facilitate unimpeded access to fibroids for laparoscopic instruments.

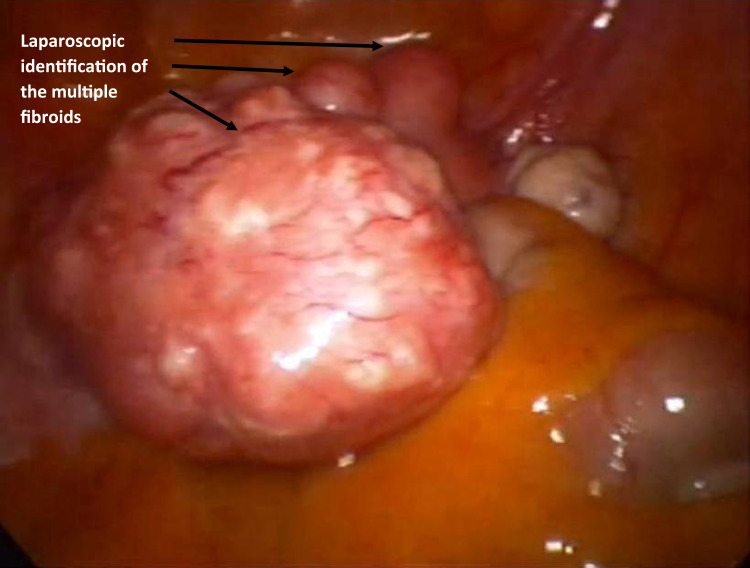

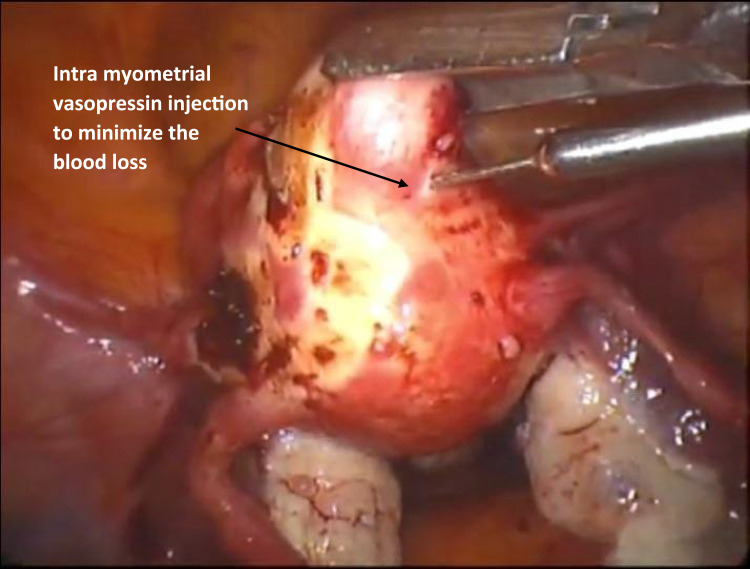

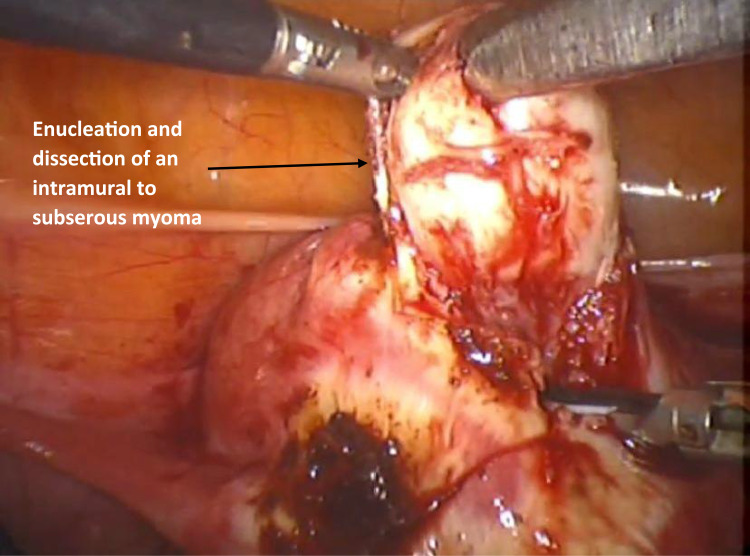

Laparoscopy identified a pedunculated fibroid, approximately 7 cm in size (Figure 2), and intra-myometrial vasopressin was injected to minimize bleeding (Figure 3). Dissection began from the left pelvic side wall, targeting the serosa within the myometrium using a harmonic scalpel. Dissection continued until the myoma pseudo-capsule was reached. The fibroids were enucleated using a 0-degree camera, ensuring thorough visualization (Figure 4). Similarly, another intramural fibroid 3.5 cm in size was identified and dissected from its pseudo-capsule.

Figure 2.

The first pedunculated fundal fibroid identified by the laparoscopy.

Figure 3.

Fibroid intra-myometrial injection by vasopressin.

Figure 4.

Enucleation and dissection of an intramural fibroid.

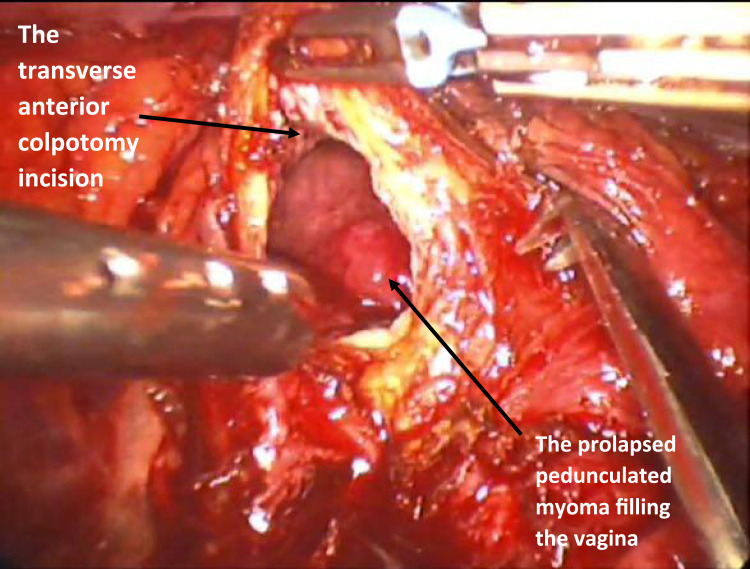

A transverse anterior colpotomy incision was performed after bladder dissection using a harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) from lateral to medial and bluntly for further mobilization using a gauze (Figure 5). A soaked gauze was applied on the vaginal opening at its entrance to maintain the pneumoperitoneum even after performing the anterior colpotomy. We have approached the lesion perpendicularly, utilizing blunt palpation to locate the exact site for the colpotomy. This tactile feedback enabled us to perform the colpotomy directly over the lesion with precision. The cervicovaginal pedunculated leiomyoma was identified through the colpotomy incision, grasped, and excised using a bipolar electrocautery coagulation (Figure 6). A 7×8 cm mass was removed and extracted.

Figure 5.

Transverse anterior colpotomy incision.

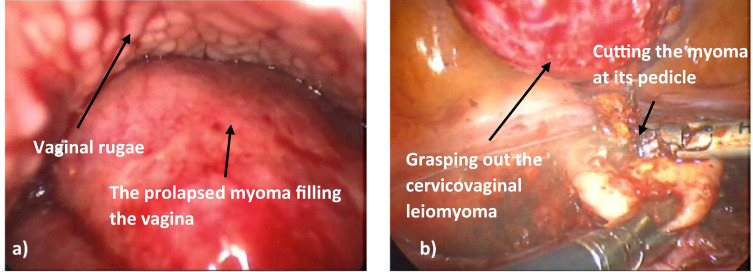

Figure 6.

(a) Identification of the prolapsed cervicovaginal leiomyoma through the colpotomy incision. (b) Grasping of the prolapsed myoma out through the colpotomy incision and its excision at its pedicle using the bipolar electrocautery.

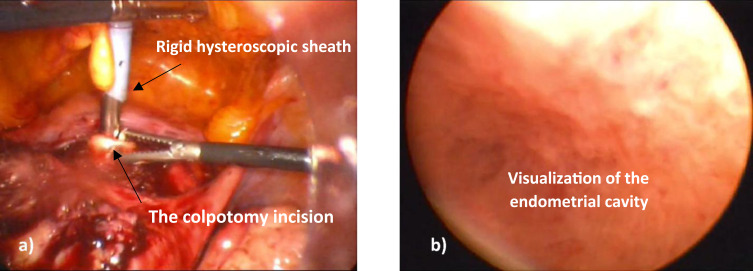

A 5 mm port suprapubic port was placed 3 cm above the pubic symphysis in the midline to minimize the risk of injury to vital organs and to facilitate the introduction of a rigid 5 mm hysteroscopic sheath through the colpotomy incision. This approach enhances surgical access while ensuring safety during laparoscopic procedures.

The hysteroscopic sheath was inserted through the colpotomy (without disrupting the hymen) through the colpotomy incision and advanced sequentially through the external OS, cervical canal, and internal OS, ultimately reaching the uterine cavity to visualize the uterine cavity, ensure adequate hemostasis, and rule out any additional endometrial lesions, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

(a) Rigid hysteroscopic sheath insertion through the colpotomy incision. (b) Visualization of the endometrial cavity to rule out any other lesions or any source of bleeding.

Then, the uterus and vaginal defect were repaired in multiple layers, with careful attention to preserving the myometrium to maintain uterine function and the integrity of the uterine cavity for future pregnancies; continuous barbed sutures were used to restore normal uterine anatomy. The fibroids were removed from the pelvis via morcellation (Video S1).

No intraoperative complications were observed. The procedure lasted 120 minutes with an operative blood loss of 430 mL. No blood transfusions were required intraoperatively or postoperatively.

On the first post-operative day, the Hb level was 11 g/dL, and the pain was assessed with a visual analog scale (VAS) score of 4. Minimal vaginal bleeding was observed, and the patient was discharged 24 hours after surgery. Follow-up assessments were scheduled to monitor recovery, uterine repair integrity, and potential complications. The patient reported significant symptom relief and was satisfied with the surgical outcomes.

Discussion

Uterine leiomyoma can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding, and its removal is beneficial for treating heavy menstrual bleeding associated with leiomyoma in women who wish to preserve their uterus and fertility, as demonstrated in our case.30

Vaginal myomectomy is the treatment of choice for prolapsed pedunculated leiomyoma due to its simplicity and safety.10 However, in conservative communities, intact hymens are seen as a symbol of sexual purity and virginity. As a result, unmarried women may largely reject surgical interventions through the vaginal route, despite the low risk of hymen disruption. Therefore, the gynecologist should consider other safe and effective techniques based on the patient’s desire or anatomic obstacles.

Here, we present a case of successful removal of a prolapsed, pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma by anterior colpotomy and myomectomy via laparoscopic access in a 30-year-old virgin woman, ensuring the preservation of hymenal integrity without intra- or post-operative complications. Prior to the surgery, the patient was not downregulated prior to surgery due to the acute and severe nature of her symptoms, particularly heavy menstrual bleeding and pelvic pain, which required immediate surgical intervention. Tranexamic acid was administered to the patient to control the heavy menstrual bleeding by inhibiting fibrinolysis through the reversible blocking of plasminogen.31 However, despite the established efficacy of tranexamic acid during the acute and chronic settings, it has no direct effect on uterine leiomyoma, and it failed to control the bleeding in our patient. Therefore, surgical intervention was recommended.

The LASHA approach was chosen to allow for the immediate excision of the tumor, thereby alleviating her symptoms and improving her quality of life without delay. Pre-operative downregulation was unnecessary since the surgical approach did not require a reduction in uterine size and prompt symptom relief was the priority. Instead, intra-myometrial vasopressin injection and bipolar electrocautery were utilized during the procedure to minimize blood loss.

There are several approaches for managing leiomyoma, and the choice depends on several factors, including the tumor size and location, the extensions, the desire for fertility, the symptoms severity of symptoms, the patient’s age, and the surgeon’s experience.32 Surgical interventions focusing on the removal of the myoma while preserving the uterus are the preferred surgical approach among fertile women.33,34 Hysterectomy is commonly used for large leiomyomas for women who have completed their family or for those with severe hemorrhage, sepsis, or failed myomectomy.35–37

The resection of small pedunculated leiomyoma by hysteroscopy is usually successful. However, it is not suitable for large masses.38 For symptomatic prolapsed pedunculated leiomyoma, vaginal myomectomy is the optimal choice being safe, straightforward with minimal morbidity. However, it may lead to infection, excessive bleeding from the stalk, and uterine inversion.2,39 However, the technique is not suitable for cases with a large and high-up leiomyoma stalk or inadequate vaginal surgical space. In such cases, abdominal approaches could be considered.

Ultrasound evaluation is the initial diagnostic tool for leiomyoma. Nevertheless, MRI and CT can provide accurate preoperative tumor localization. Moreover, MRI offers imaging planes that cannot be obtained via either transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound, allowing better visualization of the posterior and lateral aspects of the pelvis.40

The pelvic ultrasound in the present case revealed a large, solid, hypo-echoic mass in the cervicovaginal area. This mass was well-defined and filled the vaginal margins. These findings were confirmed by a pelvic MRI, which indicated that the mass is most likely a prolapsed, pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma (5.7x6.6x8.3 cm).

Therefore, the vaginal myomectomy followed by hymenal repair was suggested. Open myomectomy and hysterectomy were also suggested, but the patient and her family refused these options and preferred a minimally invasive approach, so the laparoscopic approach was decided, along with the patient’s desire to preserve hymenal integrity.

Yet, our patient was obese, which is considered a challenge for performing the laparoscopy. Traditionally, obesity was associated with perioperative difficulties during laparoscopic procedures, including prolonged procedure time, excessive blood loss, higher risk of complications, and technical difficulties such as the unfamiliarity of initial trocar entry, port placement, or management of hypercarbia.41–43

However, it was recently shown that laparoscopy could be performed safely on obese patients with adequate surgeon training and skills and appropriate perioperative considerations, including preoperative prophylaxis, optimal patient positioning to allow visualization and avoid physical barriers, and accurate abdominal entry and port placement.44

Several reports have discussed the removal of leiomyoma from virgin women while preserving hymenal integrity by different approaches. Toy et al, Komleh et al, and Hidayah et al have reported a successful excision of large prolapsed pedunculated leiomyoma of virgin women through abdominal operation and laparotomy.45–47 Alternatively, Wehbe and his colleagues performed the procedure using posterior colpotomy via laparoscopic access.48 And, Yalcin et al performed mini-laparotomic anterior colpotomy.49

Sleiman et al managed to excess the large cervicovaginal leiomyoma of two virgin cases by anterior or posterior colpotomy through laparoscopic abdominal access with successful hymen preservation. Posterior colpotomy usually offers easier access and avoidance of bladder dissection than the anterior colpotomy. Nevertheless, anterior colpotomy is adopted in the presence of endometriosis-related changes or when the main bulk of the leiomyoma is situated anteriorly.11 In this case, anterior colpotomy was preferred over posterior colpotomy because it provides better exposure to the myoma pedicle and a wider surgical field. Additionally, this approach minimizes the risk of injury to the colon and rectum, making it a safer and more effective option for this procedure. Additionally, the anterior colpotomy incision was performed after bladder dissection using a harmonic scalpel from lateral to medial and bluntly for further mobilization using a gauze.

For future pregnancies and labor in our case, a Cesarean section is generally recommended for patient safety, given that the uterine cavity was not opened. However, according to the Montgomery Protocol and ethical guidelines, vaginal delivery may be considered under the supervision of a lead care consultant, with continuous fetal monitoring throughout labor. It is important to emphasize that a Cesarean section is a safer option, as it reduces the risk of uterine rupture due to scarring from the intramural and subserous myomectomy and helps avoid over-distension of the colpotomy incision.

Here, a suprapubic port was placed to minimize the risk of injury to vital organs and to facilitate the introduction of a hysteroscopic sheath through the colpotomy incision. The suprapubic access allowed the surgery to remain minimally invasive, and the easy access of the port. The needles are passed under direct visualization with minimal camera manipulation, allowing for the extraction of large tissue samples within a specimen pouch through the same suprapubic incision in a short amount of time.

We employed morcellation to minimize the risk of spreading occult sarcomatous leiomyoma fragments within the abdominal cavity.50 Moreover, we utilized bipolar electrocautery and intra-myoma injection of vasopressin to successfully decrease intraoperative blood loss or the need for blood transfusion.51

Continuous barbed sutures were used to restore normal uterine anatomy. Previous clinical trials emphasized the superiority of barbed sutures compared to conventional absorbable sutures. Barbed sutures decrease the suturing time and facilitate the suturing process of the uterine wall defect, reducing blood loss and the post-operative need for blood transfusion.52

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case of a prolapsed, pedunculated cervicovaginal leiomyoma was successfully treated by anterior colpotomy and myomectomy via laparoscopic access, allowing for the removal of the leiomyoma while preserving hymenal integrity and fertility. The suprapubic access improves surgical access and ensures safety during the laparoscopic procedures. Additionally, the anterior colpotomy minimizes the risk of injury to the surrounding organs and facilitates access to the leiomyoma. Therefore, the indications of laparoscopy could be extended to cervicovaginal leiomyoma in virgin cases who reject vaginal approaches. However, this technique necessitates adequate equipment and advanced skills in laparoscopic surgery. Additionally, proper counseling with the patients and their family is necessary during the choice of the surgical approach to discuss the benefit-risk balance, considering potential intraoperative complications and the recurrence rate after surgery.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the patient for her courage and willingness to share her experience, which made this case report possible. We also thank our surgical team for their skill and teamwork during the laparoscopic myomectomy, and we are grateful to the nursing and support staff for their outstanding care throughout the patient’s treatment journey. Moreover, the authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr Omnia Mokbel, Research Unit Manager at El-Banna Group and Nadine el Masry Research adminstrative for her valuable insights and thorough review throughout the research process.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Informed Consent

The patient provided written informed consent for publication and any accompanying images.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Giuliani E, As-Sanie S, Marsh EE. Epidemiology and management of uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;149(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydın S, Çelik HG, Maraşlı M, Bakar RZ. Clinical predictors of successful vaginal myomectomy for prolapsed pedunculated uterine leiomyoma. J Turkish Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2018;19(3):146. doi: 10.4274/jtgga.2017.0135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serradilla LN, Gómez-Ríos MA, Nicolás C, Ramón Y, Cajal L. Embolization before surgery of a large pedunculated submucosal myoma prolapsed into the vagina. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(5):554–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandrasiri DACT, Munasinghe BM, Pushpakanthan EJ, Jayasinghe JBU, Nissankaarachchi RD. Vaginal prolapse of a large uterine cervical leiomyoma complicated with cervical inversion: a case report of an extremely rare entity with review of the literature. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221135596. doi: 10.1177/2050313X221135596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Shukri M, Al-Ghafri W, Al-Dhuhli H, Gowri V. Vaginal myomectomy for prolapsed submucous fibroid: it is not only about size. Oman Med J. 2019;34(6):556–559. doi: 10.5001/omj.2019.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brito LGO, Magnani PS, de Azevedo Trapp AE, Sabino-de-Freitas MM. Giant prolapsed submucous leiomyoma: a surgical challenge for gynecologists. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(3):299–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thanasa E, Thanasa A, Grapsidi V, et al. Bilateral obstructive uropathy and severe renal dysfunction associated with large prolapsed pedunculated submucosal leiomyoma of the uterus misdiagnosed as an intracervical fibroid: report of a very rare case and a mini‑review of the literature. Med Int. 2024;4(3):1–9. doi: 10.3892/mi.2024.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson PR. A large submucous fibroid polyp causing inversion of the uterus. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;20(4):251–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1980.tb00779.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babah O, Afolabi B, Olufemi A, A A, O O. Prolapsed submucous uterine fibroid with associated uterovaginal prolapse: a case report. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13(3):64–67. doi: 10.9790/0853-13346467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golan A, Zachalka N, Lurie S, Sagiv R, Glezerman M. Vaginal removal of prolapsed pedunculated submucous myoma: a short, simple, and definitive procedure with minimal morbidity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271(1):11–13. doi: 10.1007/s00404-003-0590-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sleiman Z, Ayed A, Christoforou C, et al. Hymen conservative techniques for vaginal surgery – a practical approach. Przeglad Menopauzalny. 2022;21(1):64. doi: 10.5114/pm.2022.113556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mauri F, Lambat Emery S, Dubuisson J. A hybrid technique for the removal of a large prolapsed pedunculated submucous leiomyoma. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51(5):102365. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2022.102365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciebiera M, Łoziński T, Wojtyła C, Rawski W, Jakiel G. Complications in modern hysteroscopic myomectomy. Ginekol Pol. 2018;89(7):398–404. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2018.0068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu R, Zhou X, Wang L, Cao Y. Gas embolism during surgical hysteroscopy leading to cardiac arrest and refractory hypokalemia: a case report and review of literature. Medicine. 2023;102(37):E35227. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000035227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takasaki K, Henmi H, Ikeda U, Endo T, Azumaguchi A, Nagasaka K. Intrauterine adhesion after hysteroscopic myomectomy of submucous myomas. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49(2):675–681. doi: 10.1111/jog.15499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng M, Chang WH, Yang ST, et al. Efficacy of applying hyaluronic acid gels in the primary prevention of intrauterine adhesion after hysteroscopic myomectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Life. 2020;10(11):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bortoletto P, Keefe KW, Unger E, Hariton E, Gargiulo AR. Incidence and risk factors of intrauterine adhesions after myomectomy. F&S Reports. 2022;3(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.xfre.2022.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost AS, McMahon M, Smith AJB, Borahay MA, Patzkowsky KE. Predictors of minimally invasive myomectomy in the national inpatient sample database, 2010–2014. JSLS J Soc Laparosc Robot Surg. 2021;25(4):e2021.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaritsky E, Le A, Tucker LY, Ojo A, Weintraub MR, Raine-Bennett T. Minimally invasive myomectomy: practice trends and differences between Black and non-Black women within a large integrated healthcare system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(6):826.e1–826.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolmans MM, Donnez J, Fellah L. Uterine fibroid management: today and tomorrow. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45(7):1222–1229. doi: 10.1111/jog.14002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gitas G, Alkatout I, Allahqoli L, et al. Severe direct and indirect complications of morcellation after hysterectomy or myomectomy. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2022;31(3):418–425. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2020.1802292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Jiang W, Xu H, Ye X, Xu C. Characteristics of uterine rupture after laparoscopic surgery of the uterus: clinical analysis of 10 cases and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(9):3630–3639. doi: 10.1177/0300060518776769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Güven CM, Uysal D. In-bag abdominal manual morcellation versus contained power morcellation in laparoscopic myomectomy: a comparison of surgical outcomes and costs. BMC Surg. 2023;23(1). doi: 10.1186/s12893-023-02007-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Fibroids and medical therapy: bridging the gap from selective progesterone receptor modulators to gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(4):739–741. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbas AM, Michael A, Ali SS, Makhlouf AA, Ali MN, Khalifa MA. Spontaneous prelabour recurrent uterine rupture after laparoscopic myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;38(7):1033–1034. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2018.1447913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asgari Z, Salehi F, Hoseini R, Abedi M, Montazeri A. Ultrasonographic features of uterine scar after laparoscopic and laparoscopy-assisted minilaparotomy myomectomy: a comparative study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(1):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Advincula AP. Robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy: technique & brief literature review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2024;93:102452. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2023.102452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.T M, T S, L A, D K, F W. Implementation of robot-assisted myomectomy in a large university hospital: a retrospective descriptive study. Facts Views Vis ObGyn. 2023;15(3):243–250. doi: 10.52054/FVVO.15.3.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheng Y, Hong Z, Wang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopic myomectomy: a systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21(1). doi: 10.1186/s12957-023-03104-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saridogan E. Surgical treatment of fibroids in heavy menstrual bleeding. Women’s Heal. 2016;12(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, Carmona F, Calaf J, Chapron C. The modern management of uterine fibroids-related abnormal uterine bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2024;122(1):20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cianci S, Gulino FA, Palmara V, et al. Exploring surgical strategies for uterine fibroid treatment: a comprehensive review of literature on open and minimally invasive approaches. Medicina. 2023;60(1):64. doi: 10.3390/medicina60010064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falcone T, Parker WH. Surgical management of leiomyomas for fertility or uterine preservation. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):856–868. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182888478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laughlin SK, Stewart EA. Uterine leiomyomas: individualizing the approach to a heterogeneous condition. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2):396–403. (). doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820780e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.da Silva BB, da Silva-Sampaio JP, Lopes-Costa PV, da Silva BB, da Silva-Sampaio JP. Huge prolapsed pedunculated necrotizing submucosal leiomyoma. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(7):1128–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newton BW, Harmanli O. Perplexing presentation of uterine prolapse and a prolapsed pedunculated leiomyoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):799.e1–799.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pieh-Holder KL, Bell H, Hall T, DeVente JE. Postpartum prolapsed leiomyoma with uterine inversion managed by vaginal hysterectomy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2014/435101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Küçük T. When virginity does matter: rigid hysteroscopy for diagnostic and operative vaginoscopy--a series of 26 cases. J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(5):651–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caglar GS, Tasci Y, Kayikcioglu F. Management of prolapsed pedunculated myomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89(2):146–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamoto Y, Tanaka YO, Nishida M, Tsunoda H, Yoshikawa H, Itai Y. MR imaging of the uterine cervix: imaging-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23(2):425–445. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidson BA, Weber JM, Monuzsko KA, Truong T, Havrilesky LJ, Moss HA. Evaluation of surgical morbidity after hysterectomy during an obesity epidemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(4):589–596. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Hanlan KA, Emeney PL, Frank MI, Milanfar LC, Sten MS, Uthman KF. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: making it safe and successful for obese patients. JSLS J Soc Laparosc Robot Surg. 2021;25(2):e2020.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mikhail E, Miladinovic B, Velanovich V, Finan MA, Hart S, Imudia AN. Association between obesity and the trends of routes of hysterectomy performed for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(4):912–918. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbaresso R, Parikh S, Pasic R. Should laparoscopy be performed in the morbidly obese? An expert opinion supporting conventional laparoscopy and intraoperative considerations for the patient with obesity with benign gynaecological conditions. Gynecol Obstet Clin Med. 2024;4(3):e000049. doi: 10.1136/gocm-2024-000049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasekhi Komleh M. Treatment of pedunculated submocusal myoma with preservation of hymen; case report of Sarem women’s hospital. Sarem J Reproduc Med. 2019;4(1):77–79. doi: 10.29252/sjrm.4.1.77 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toy H, Camuzcuoglu H, Vural M. Surgical management of prolapsed pedunculated submucous leiomyoma in a virgin woman. Duzce Med J. 2011;13:63–65. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hidayah GN, Harzif AK, Noviani A, Tantry HP, Santoso BI, Situmorang H. Selecting the best surgical approach in various cases of prolapsed pedunculated submucosal fibroids: a case series. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;113:109029. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.109029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wehbe GS, Doughane M, Bitar R, Sleiman Z. Laparoscopic posterior colpotomy for a cervico-vaginal leiomyoma: hymen conservative technique. Facts Views Vision in ObGyn. 2016;8(3):169. doi: 10.1016/j.circir.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yalçin I, Pabuçcu E, Kahraman K, Sönmezer M, Kahraman K. Mini-laparotomic colpotomy for a cervicovaginal leiomyoma: preservation of hymenal integrity. Inter J Reproduc Biomed. 2016;14(3):217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKenna JB, Kanade T, Choi S, et al. The Sydney contained in bag morcellation technique. J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):984–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faivre E, Surroca MM, Deffieux X, Pages F, Gervaise A, Fernandez H. Vaginal myomectomy: literature review. J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(2):154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tatar SA, Karadağ B, Karadağ C, Turgut GD, Karataş S, Mülayim B. Barbed versus conventional suture in laparoscopic myomectomy: a randomized controlled study. J Turkish Soc Obstet Gynecol. 2023;20(2):126. doi: 10.4274/tjod.galenos.2023.21208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]