Abstract

Background

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a severe cardiac condition characterized by ventricular dilation and impaired systolic function, leading to heart failure and sudden death. Current treatments have limited efficacy in reversing disease progression. Recent research suggests that disulfidptosis, a novel cell death mechanism, may play a role in DCM pathogenesis, though its specific involvement remains unclear.

Methods

This study utilized multiple GEO datasets to analyze the expression of 24 disulfidptosis-related genes (DiGs) in DCM patients and healthy controls. Differential expression analysis and consensus clustering were used to classify DCM patients into subgroups based on DiGs expression profiles. A predictive model was constructed using four machine learning methods, and its performance was validated with independent datasets. A ceRNA regulatory network was established, and in vivo experiments were conducted using a DCM mouse model to validate key findings.

Results

Nineteen DiGs were differentially expressed between DCM and controls. Consensus clustering divided DCM patients into two subtypes with distinct immune profiles. The support vector machine (SVM) model demonstrated superior diagnostic performance (AUC = 0.983), identifying ACTN4, MYH10, TLN1, DSTN, and NCKAP1 as core predictors. In vivo validation confirmed their expression changes in myocardial tissue. Single-cell RNA-seq further revealed increased fibroblast and macrophage infiltration in DCM, along with enrichment of fibrotic and immune pathways. Quercetin and resveratrol were predicted as potential drugs targeting these core genes.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that ACTN4, MYH10, TLN1, DSTN, and NCKAP1 play significant roles in the pathogenesis of DCM, influencing immune cell infiltration and metabolic homeostasis. Quercetin and resveratrol were identified as potential therapeutic agents, offering new directions for DCM treatment.

Keywords: dilated cardiomyopathy, diagnostic model, disulfidptosis-related genes, immune cell infiltration

Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a type of cardiomyopathy characterized by dilation of the left or both ventricles and impaired systolic function, without other organic heart diseases such as hypertension, valvular disease, or coronary artery disease.1 Its etiology is complex, including genetic factors, infections, toxin exposure, and autoimmune abnormalities.2 DCM is a significant cause of heart failure and sudden death, and its global incidence is influenced by geographical and racial differences.3,4 Clinically, it presents as progressive heart failure symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, and palpitations; severe cases may develop cardiogenic shock and life-threatening arrhythmias.5 Current treatment mainly focuses on improving cardiac function and preventing complications, including ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors.1 Patients with left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% are recommended for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) placement, and heart transplantation may be considered for patients with end-stage heart failure.1 Despite the availability of various treatment options, the reversal of disease progression remains limited, necessitating further research into the etiology and pathogenesis of DCM to develop more effective therapeutic strategies.

Research has indicated that DCM is closely related to various cell death mechanisms, including apoptosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, and pyroptosis.6–10 These mechanisms collectively lead to cardiomyocyte injury, ventricular remodeling, and cardiac dysfunction, impacting disease progression and prognosis. Disulfidptosis is a recently identified form of cell death mediated by the SLC7A11 gene, primarily through the abnormal accumulation of intracellular cysteine, resulting in the formation of disulfide compounds, which trigger oxidative stress and cell death.11,12 This mechanism is particularly pronounced under glucose-deficient conditions, as the depletion of NADPH further exacerbates disulfide stress.13 Currently, disulfidptosis has been found to be involved in the pathogenesis of cancer and ischemic stroke,13,14 but its specific role in cardiovascular diseases, especially in DCM, remains unclear. Although there is no direct evidence of disulfidptosis involvement in DCM, there are indirect connections between the two in several aspects. First, cardiomyocytes in DCM patients are often subjected to oxidative stress damage, and disulfidptosis also induces cell death through oxidative stress mechanisms. Secondly, the inflammatory response commonly seen in DCM is closely related to disulfidptosis, which regulates immune responses through inflammatory signaling pathways such as TNF, potentially exacerbating inflammatory damage in DCM.14 Additionally, DCM patients often have myocardial energy metabolism disorders, and disulfidptosis is activated under metabolic disorder conditions, suggesting that it may influence the pathological process of DCM through metabolic imbalance. Disulfidptosis may indirectly contribute to the pathogenesis of DCM through oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and metabolic imbalance.14 Thus, further investigation of its specific role in cardiomyocytes could offer new perspectives and therapeutic targets for DCM.

Machine learning, which identifies patterns for prediction and classification, has been increasingly applied in medical research. It mainly includes methods such as supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning, which can extract useful information from large and complex datasets. In disease diagnosis, machine learning can integrate clinical data and gene expression information to improve the accuracy of disease risk prediction and classification. For example, in ischemic stroke research, researchers have used algorithms such as LASSO, random forest, and support vector machines to identify key genes associated with disulfidptosis and construct a model to predict stroke risk.14 Moreover, machine learning also plays an important role in the discovery of biomarkers. By analyzing multidimensional omics data, such as genes, proteins, and metabolites, machine learning can identify disease-related biomarkers, providing new insights for early diagnosis and personalized treatment. For example, in cancer and cardiovascular disease research, machine learning is used to identify potential disease biomarkers that contribute to more precise disease management and therapeutic strategies.15 Overall, machine learning provides new tools for medical research through data-driven approaches, bringing revolutionary advancements in disease diagnosis, risk assessment, and personalized treatment.

In this study, we used the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database to analyze the differences in DiGs expression between the normal group and DCM patients. Based on the expression of DiGs, we classified DCM patients into two clusters and compared the DiGs between these clusters. Furthermore, we developed a prediction model, identified core DiGs by evaluating four machine learning methods, and validated the performance of the prediction model using external datasets. We constructed a CeRNA regulatory network based on core DiGs, identified potential therapeutic drugs targeting these core DiGs using the CTD database, and explored the relationship between core DiGs and immune cells using different immune cell infiltration algorithms. Finally, we validated the core DiGs through in vivo experiments. Our aim is to use bioinformatics techniques to identify the role of DiGs in the pathogenesis and progression of DCM, providing new targets and diagnostic markers for subsequent DCM treatment.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

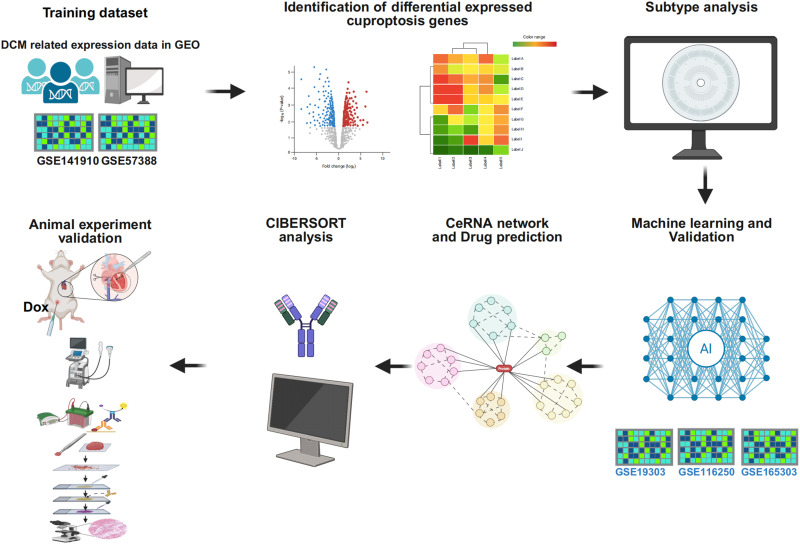

The datasets GSE141910,16 GSE57338,17 GSE19303,18 GSE116250,19 and GSE165303 were retrieved from the GEO database (Supplementary Table 1).20 Using the sva package in R 4.3.3, batch correction was performed on the GSE57338 and GSE141910 datasets, which were then combined to create a training set consisting of 297 control and 256 DCM samples.21 The GSE19303, GSE116250, and GSE165303 datasets were utilized as validation sets (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The study design.

Selection of Differentially Expressed DiGs

Differentially expressed DiGs were identified by selecting 24 genes reported in previous studies.11,12 Differential expression analysis between DCM and control samples was performed using the limma package in R. A moderated t-test was applied, and p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Genes with an adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results were visualized using heatmaps generated with the pheatmap package.22,23

Cluster Analysis Based on Differentially Expressed DiGs

Cluster analysis was performed using ConsensusClusterPlus on the DiGs in the training set. Subsequently, the training dataset was evaluated with Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA).24

Construction of a Predictive Model Utilizing Various Machine Learning Methods

The models included an extreme gradient boosting (XGB) model,25 support vector machine (SVM),26 random forest (RF),27 and generalized linear model (GLM).28 The DALEX package was utilized to visualize the residual distributions across the four machine-learning models. The optimal model was selected, and the top five genes were identified as core diagnostic markers. The performance of the models was evaluated by visualizing the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves using the “pROC” R package.

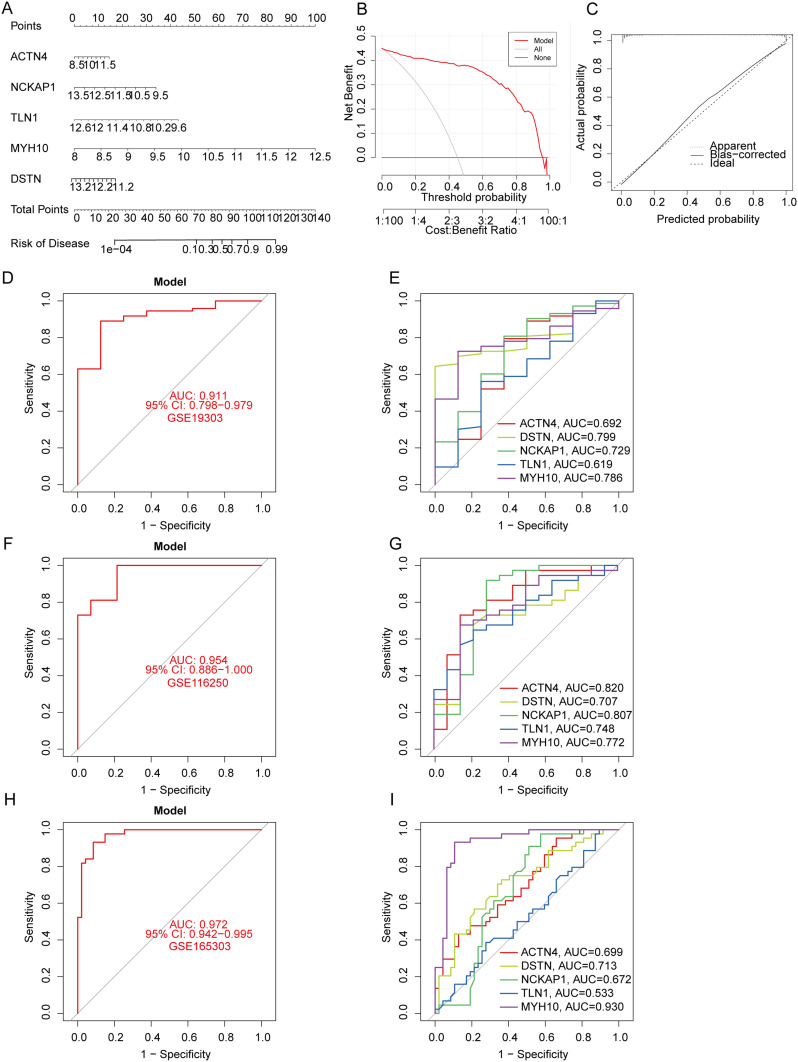

Nomogram Construction and Validation

To validate and enhance the applicability of the prediction model, a nomogram incorporating five key predictors (DSTN, ACTN4, MYH10, NCKAP1, and TLN1) was constructed using the “RMS” R package. Each predictor was assigned a score based on its regression coefficient, and the “total score” of the patient was calculated by summing these scores to predict the risk of prognosis or the probability of event occurrence. The calibration curve was used to assess the consistency between the predicted values of the model and the actual incidence, and decision curve analysis (DCA) was employed to evaluate the clinical utility of the nomogram, thereby validating the reliability of the model.

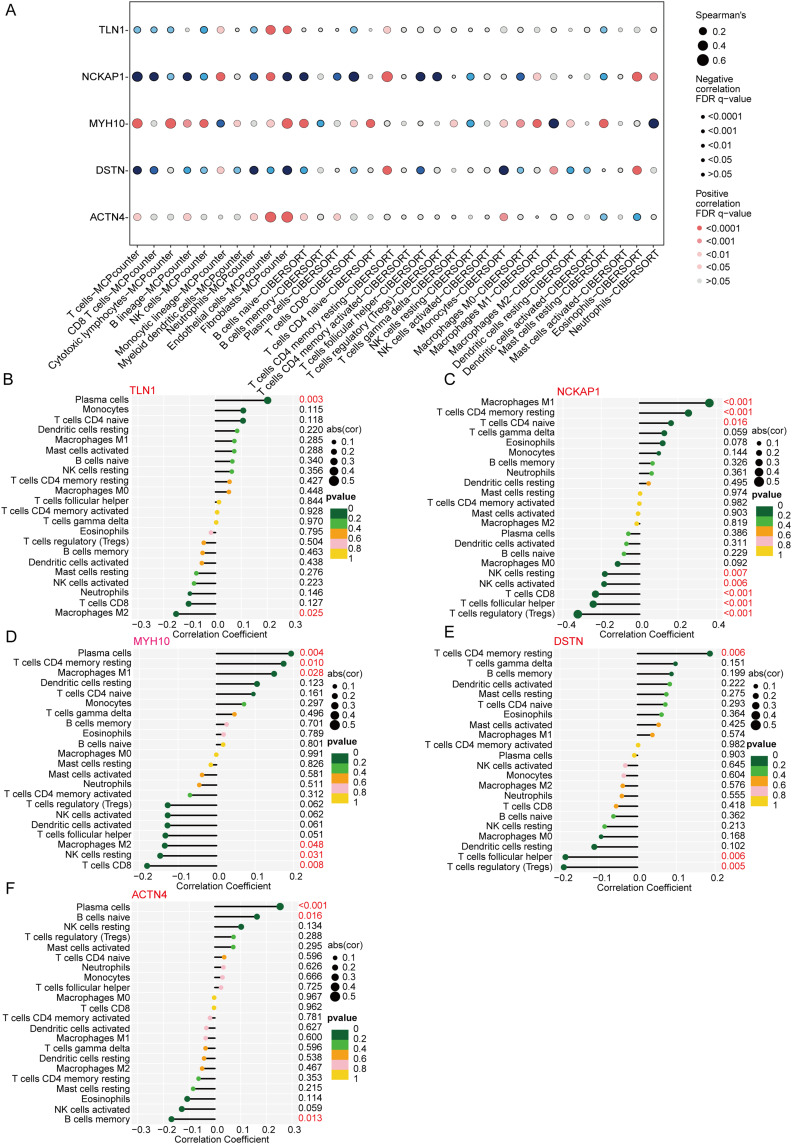

Analysis of Immune Cell Infiltration in DCM

Multiple algorithms, including MCPcounter, and CIBERSORT, were employed to comprehensively analyze the expression data of model genes and the infiltration levels of different immune cells. Specifically, the CIBERSORT algorithm quantitatively evaluates 22 types of immune cells for each sample using a deconvolution method based on Monte Carlo sampling and calculates the corresponding p-value for each sample. When p < 0.05, the results are considered statistically significant, indicating the accuracy and reliability of the deconvolution analysis in the samples. This algorithm ensures that the total proportion of all immune cell types in each sample is 1, meaning that the sum of the standardized proportions of all cell types equals 100%.29

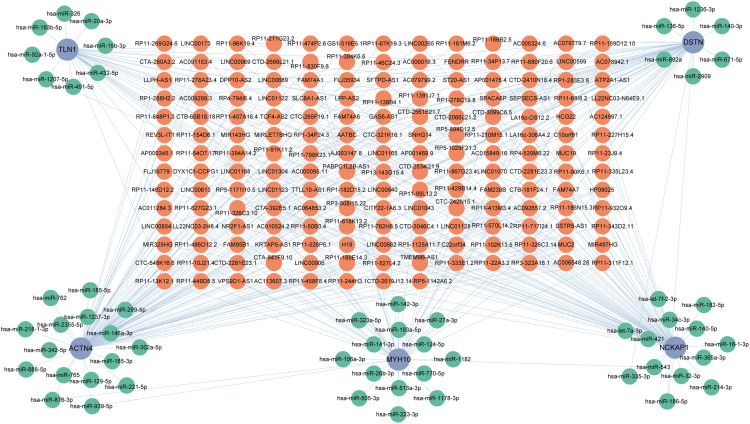

CeRNA Network Construction

The interactions between miRNA and mRNA were systematically predicted by integrating data from multiple databases. TargetScan, miRDB, and miRanda databases were used to validate and filter the binding sites and regulatory relationships between target miRNAs and mRNAs. The SpongeScan database was used to predict interactions between miRNAs and lncRNAs to identify potential competitive binding targets. Next, all validated miRNA-mRNA and miRNA-lncRNA interaction data were integrated and used to construct a ceRNA network of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA using Cytoscape software (3.7.2).

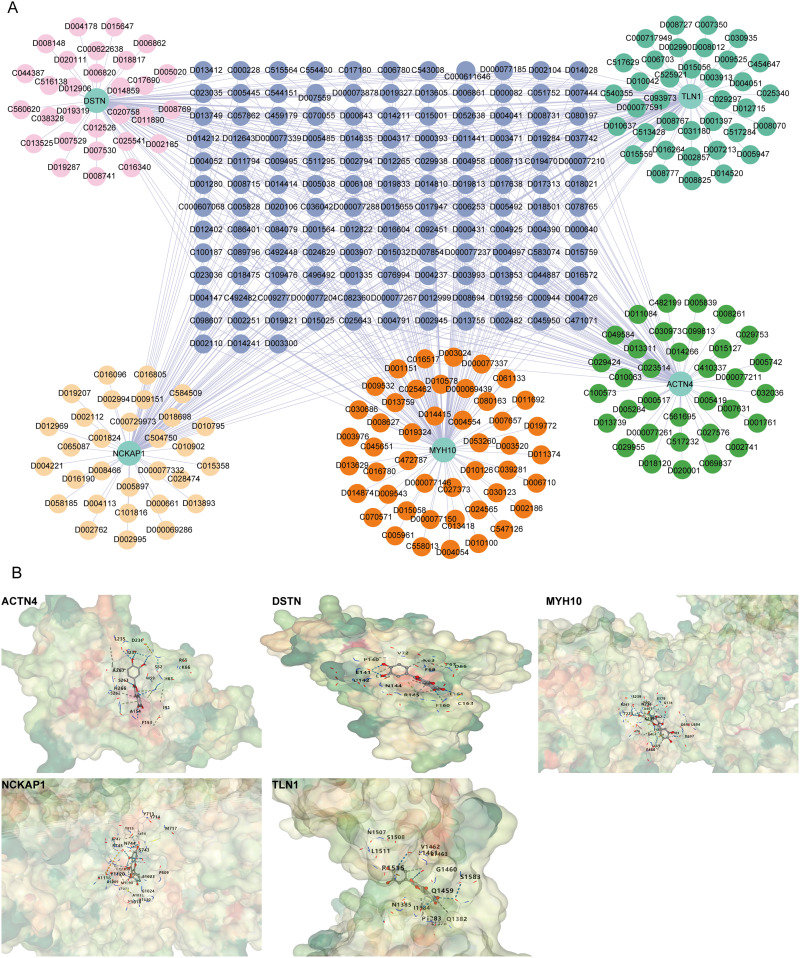

Prediction of Candidate Drugs and Molecular Docking Analysis

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) was used to predict interactions between targets and candidate drugs. Each core gene was input into the CTD to retrieve associated candidate compounds. A drug-gene interaction network was constructed using Cytoscape (version 3.7.2), and representative candidate small-molecule drugs targeting the core genes were selected for molecular docking validation. Protein structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or the AlphaFold database, and small-molecule structures were downloaded from the PubChem database and subjected to energy minimization. Molecular docking analysis was performed using AutoDock Vina. After docking, PyMOL and Discovery Studio were used to visualize the binding conformations and analyze hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and binding pocket characteristics. All binding energies were expressed in kcal/mol to evaluate the binding affinity between the drug and the target.

Animal

We purchased 8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice from the Animal Center of Suzhou University Medical College, Jiangsu Province (SYXK 2021–0065). All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Suzhou University (Approval No. 202408A0374) and conducted in strict accordance with the “Guidelines of the Chinese Animal Research Council” and the “Animal Care Guidelines” to minimize animal suffering. The mice were housed in well-ventilated rooms under controlled conditions: a temperature of 22±2°C, humidity of 55±5%, a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and ad libitum access to food and water. The mice were acclimatized for one week with standard laboratory chow and had a body weight range of 20–25g at the start of the experiment. After acclimatization, the mice were randomly assigned to a control group (n=6) and a DCM group (n=6). The DCM group received intraperitoneal injections of doxorubicin (DOX) at 5 mg/kg every 7 days to induce the DCM model, a widely used method for inducing dilated cardiomyopathy in rodents. Echocardiographic assessment was conducted after four weekly doses of DOX. Prior to euthanasia, the mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and euthanized by cervical dislocation, following ethical guidelines to ensure minimal discomfort.30

Chemicals and Materials

Sodium pentobarbital (Siasia Reagent, China), Antibodies: ACTN4 (Proteintech, 19096-1-AP, China), DSTN (affinity, DF15268, China), NCKAP1 (Proteintech, 12140-1-AP, China), MYH10 (Proteintech, 19673-1-AP, China), TLN1 (Proteintech, 14168-1-AP, China), β-actin (Proteintech, 19673-1-AP, China), goat anti-rabbit IgG (HRP Conjugate) (CST, 14708, USA) and goat anti-mouse IgG (HRP Conjugate) (CST, 14709, USA).

Echocardiographic Assessment of Cardiac Function

Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane (Baxter International, USA) and cardiac function was assessed using a cardiac ultrasound imaging system (FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Canada). The probe was placed on the left chest of the mouse to obtain long-axis images of the left ventricle, and parameters such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS), and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) were measured. The measurement results for each parameter were averaged over three consecutive cardiac cycles.

Histopathological Analysis of Myocardial Tissue

After extraction, mouse heart tissues were immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours at room temperature. The fixed tissues were then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%), cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Consecutive sections with a thickness of 4–5 μm were obtained using a rotary microtome and mounted onto glass slides.

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was performed to assess general myocardial structure and cellular morphology. Briefly, tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated through descending ethanol gradients, stained with hematoxylin for nuclear visualization, differentiated in acidic alcohol, followed by eosin staining to label cytoplasmic components. Morphological alterations such as cardiomyocyte disarray, nuclear condensation, and inflammatory infiltration were observed under a light microscope.

Masson’s trichrome staining was used to evaluate myocardial fibrosis. After deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were incubated with Weigert’s iron hematoxylin to stain nuclei, followed by treatment with acid fuchsin–ponceau solution and phosphomolybdic–phosphotungstic acid, and finally stained with aniline blue to label collagen fibers.

In addition, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was carried out to detect the expression of target proteins. After antigen retrieval and blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity, tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against ACTN4 (1:500), TNL1 (1:500), DSTN (1:500), MYH10 (1:200), and NCKAP1 (1:500). Following incubation with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, DAB substrate was used for color development. Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. Positive staining of target proteins was visualized and photographed under an optical microscope.

Detection of Key Disulfidptosis Protein Expression Levels in Myocardial Tissue

Total protein was extracted from the myocardial tissue homogenate, followed by quantification and denaturation. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by the addition of primary antibodies. Including ACTN4 (1:1000), TLN1 (1:1000), DSTN (1:1000), MYH10 (1:1000), and NCKAP1 (1:1000), the membrane was incubated overnight on a shaker at 4°C. The next day, the membrane was washed three times with TBST buffer, 10 minutes each time. Secondary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by three additional washes with TBST (10 minutes each). Finally, protein bands were detected using the Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, USA) imaging system. The bands were quantified using ImageJ software.

Single-Cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-Seq) Analysis

We analyzed the single-cell RNA sequencing dataset GSE183852 from the GEO database using the Seurat package in R.31 To ensure data quality, low-quality cells with fewer than 200 or more than 10,000 detected genes, or with over 10% mitochondrial gene content, were filtered out. After removing batch effects using the Harmony package, the data were normalized and the top 2,000 highly variable genes were selected. Dimensionality reduction was then performed using principal component analysis (PCA), and visualization was achieved with TSNE.32 Clustering was conducted using the Louvain algorithm, and specific marker genes for each subpopulation were identified using the FindAllMarkers function. Cell type annotation was automatically performed using the SingleR package and manually curated based on the CellMarker 2.0 database.33 Visualization analysis was further conducted using SCP and other R packages.

Analysis of the Association Between Core Gene Expression and Cardiac Functional Parameters

Expression profiles and corresponding clinical data of DCM patients were extracted from the GSE19303 dataset. Core gene expression levels were matched with echocardiographic parameters, specifically LVEF and LVEDD. Spearman rank correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the associations between gene expression and cardiac functional parameters. Scatter plots with fitted regression lines and marginal histograms were used to visualize the correlations.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0, and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. An independent samples t-test was conducted, with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ns indicating non-significance.

Results

DiGs Expression and Immune Infiltration Analysis in DCM Patients

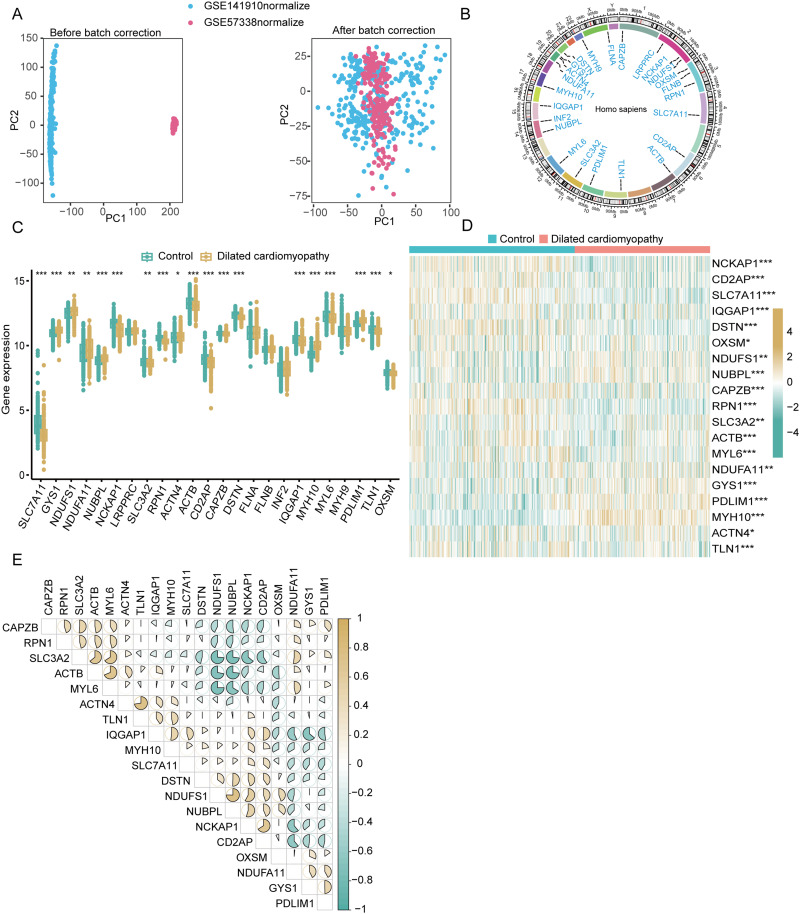

We generated the training dataset by merging the genes detected in GSE57338 and GSE141910 and removing batch effects (Figure 2A). The locations of Copy Number Variation (CNV) changes for the 24 DiGs across 23 chromosomes (Figure 2B). We analyzed the expression profiles of the 24 DiGs in DCM and control samples using the combined dataset. Comparative analysis indicated elevated expression levels of GYS1, NDUFS1, NDUFA11, NUBPL, ACTN4, MYH10, and PDLIM1, along with decreased expression of SLC7A11, NCKAP1, SLC3A2, RNP1, ACTB, CD2AP, CAPZB, DSTN, IQGAP1, MYL6, TLN1, and OXSM (Figure 2C and D). Interaction analysis of the 19 DiGs showed a significant positive correlation between NDUFS1 and NUBPL (R = 0.75), and a negative correlation between MYL6 and NDUFS1 (R = −0.75) (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Differential expression and interaction analysis of disulfidptosis-related genes (DiGs) in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) patients. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) plots before (left) and after (right) batch correction of GSE141910 (blue) and GSE57338 (pink) datasets. (B) Circos plot showing chromosomal distribution and copy number variations (CNVs) of 24 DiGs across 23 chromosomes. (C) Boxplot of 24 DiGs expression levels in control (green) and DCM (yellow) groups, with significant differences indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (D) Heatmap of 19 differentially expressed DiGs in control and DCM samples. Red indicates upregulation, blue indicates downregulation (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (E) Correlation matrix of the 19 DiGs, with positive (blue) and negative (brown) correlations shown by ellipse size and shape.

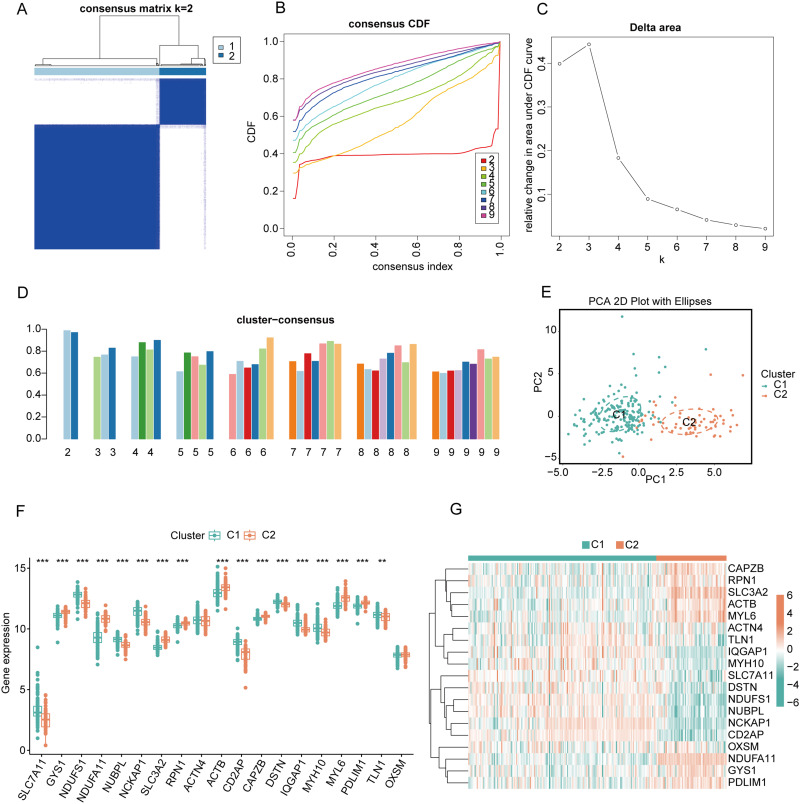

Identification of DCM Disulfidptosis Cluster

To further elucidate the expression patterns of DiGs in DCM, consensus clustering analysis was performed on 19 differentially expressed genes. The results showed that the consensus index fluctuated stably within the range of 0.2 to 0.6 (Figures 3A and B, Supplementary Figure 1). When the number of clusters (k) varied between 2 and 9, there was a significant difference in the area under the cumulative distribution function (CDF) curve between different cluster numbers (k and k-1) (Figure 3C). A higher consistency score (> 0.9) was observed only when k = 2 (Figure 3D). Based on the consensus matrix heatmap analysis, 243 patients were divided into two distinct subgroups: cluster 1 (n = 177) and cluster 2 (n = 66) (Figure 3E). Visualization of the clustering results using the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) method revealed significant differences between the two clusters (Figure 3F). Specifically, cluster 1 exhibited high expressions of SLC7A11, NDUFS1, NUBPL, NCKAP1, CD2AP, DSTN, IQGAP1, MYH10, and TLN1, while cluster 2 displayed high expressions of GYS1, NDUFA11, SLC3A2, RPN1, ACTB, CAPZB, MYL6, and PDLIM1 (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Consensus clustering and differential expression analysis of DiGs in DCM patients. (A) Consensus matrix heatmap showing the optimal clustering of DCM patients into two clusters (k = 2). (B) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves for different numbers of clusters (k = 2 to 9) based on consensus clustering. (C) Delta area plot showing the relative change in area under the CDF curve for k = 2 to 9, indicating k = 2 as the optimal number of clusters. (D) Bar plot of the cluster consensus score for different k values, demonstrating stable clustering at k = 2. (E) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing the separation between Cluster 1 (C1, green) and Cluster 2 (C2, Orange) based on DiGs expression. (F) Boxplot comparing the expression levels of 24 DiGs between Cluster 1 (C1, green) and Cluster 2 (C2, orange). Significant differences are marked with asterisks (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (G) Heatmap of the 19 differentially expressed DiGs between C1 and C2.

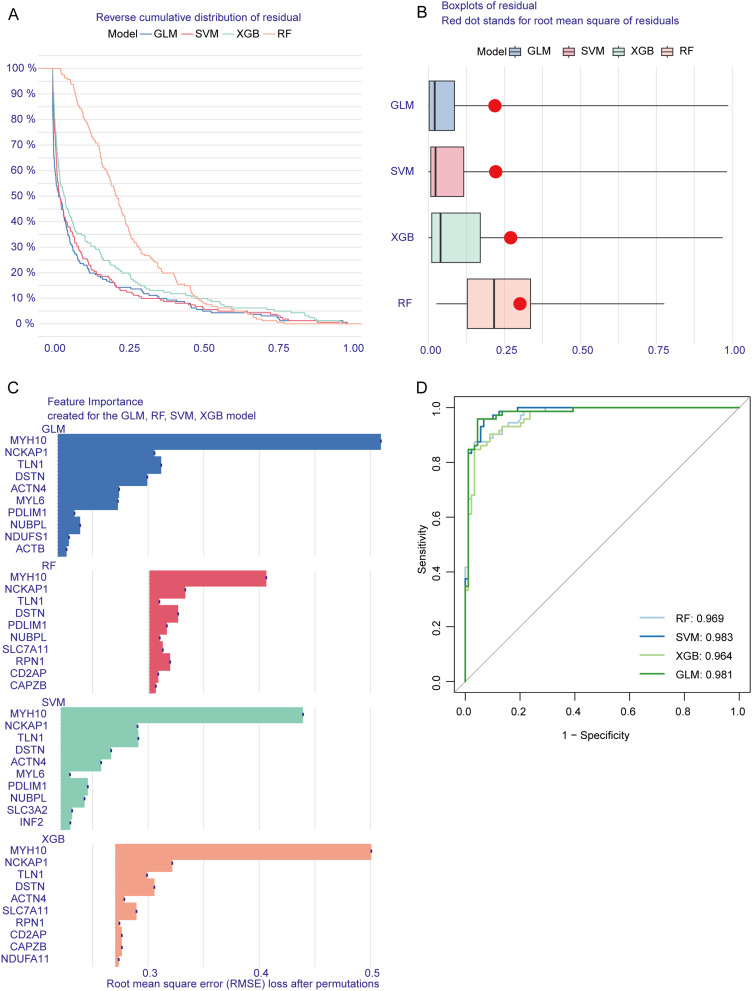

Machine Learning Model Construction

The SVM model exhibited minimal residual variation (Figure 4A and B), the top 10 significant variables for each model were identified based on root mean squared error (RMSE) (Figure 4C). Furthermore, we conducted 5-fold cross-validation and plotted ROC curves to evaluate the diagnostic performance of these algorithms. The SVM model achieved the highest AUC score (SVM: AUC = 0.983; RF: AUC = 0.969; XGB: AUC = 0.964; GLM: AUC = 0.981; Figure 4D), highlighting its superior ability to differentiate patients across various clusters. For subsequent analyses, the top five variables—ACTN4, TLN1, DSTN, MYH10, and NCKAP1—were selected from the SVM model as critical predictors.

Figure 4.

Model performance and feature importance analysis for predicting DCM using different machine learning methods. (A) Reverse cumulative distribution of residuals for four models—generalized linear model (GLM), support vector machine (SVM), extreme gradient boosting (XGB), and random forest (RF). (B) Boxplot showing residual distribution across the four models. (C) Feature importance analysis for the top predictive genes across the four models. (D) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves compare the models’ diagnostic performance.

Validation of the Predictive Performance of the SVM Model for DCM

We developed a nomogram to assess the predictive performance of the SVM model using data from 256 DCM cases (Figure 5A). To evaluate the accuracy of the nomogram, calibration curves and DCA were utilized. The DCA highlighted the high predictive accuracy of the nomogram, offering substantial support for clinical decision-making (Figure 5B). The calibration curve indicated a minimal discrepancy between the observed and predicted risks within the DCM cohort (Figure 5C). The predictive capability of the core biomarkers was further validated using independent datasets, namely GSE19303, GSE116250, and GSE165303. The ROC curves confirmed the robustness of the predictive model incorporating the five core markers, yielding AUCs of 0.911 (GSE19303, Figures 5D–E), 0.954 (GSE116250, Figures 5F and G), and 0.972 (GSE165303, Figures 5H and I). These results underscore the effectiveness of our diagnostic model in distinguishing DCM patients from healthy individuals.

Figure 5.

Validation and performance evaluation of the predictive model for DCM using independent datasets. (A) Nomogram integrating five core genes (ACTN4, NCKAP1, TLN1, MYH10, DSTN) to predict DCM risk. (B) Decision curve analysis (DCA) assessing the clinical utility of the model. (C) Calibration curve comparing predicted probabilities with actual outcomes. (D and E) ROC curves for the predictive model and individual core genes using the GSE19303 dataset. (F and G) ROC curves for the predictive model and individual core genes using the GSE116250 dataset. (H and I) ROC curves for the predictive model and individual core genes using the GSE165303 dataset.

CeRNA Network Establishment

This network consisted of 239 nodes, including 5 core diagnostic markers, 57 miRNAs, and 177 lncRNAs, interconnected by 337 interactions (Figure 6). Within this network, 78 lncRNAs were identified to competitively bind with Actn4 mRNA, mediated by 16 miRNAs, among which lncRNA LINC01043 concurrently targets both hsa-miR-221-5p and hsa-miR-218-1-3p. In addition, 36 lncRNAs were found to interact with Myh10 mRNA, regulated by various miRNAs. Furthermore, 48 lncRNAs were shown to target Dstn mRNA, influenced by hsa-miR-136-5p, hsa-miR-892a, hsa-miR-335-3p, hsa-miR-2909, hsa-miR-186-5p, hsa-miR-671-5p, hsa-miR-140-3p, and hsa-miR-1236-3p. Additionally, 64 lncRNAs were identified to target Nckap1 mRNA through multiple miRNAs. Moreover, 31 lncRNAs were observed to regulate Tln1 mRNA, mediated by a variety of miRNAs, including hsa-miR-20a-3p, hsa-miR-326, hsa-miR-193b-5p, hsa-miR-1207-5p, hsa-miR-92a-1-5p, hsa-miR-491-5p, hsa-miR-432-5p, and hsa-miR-15b-3p.

Figure 6.

Construction of the ceRNA regulatory network for core DiGs in DCM. The ceRNA network illustrates the interactions between lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs associated with five core genes (TLN1, DSTN, ACTN4, MYH10, NCKAP1). Orange nodes represent lncRNAs, green nodes represent miRNAs, and blue nodes represent mRNAs.

Prediction of Targeted Drugs

A drug prediction network comprising 315 nodes and 550 edges was constructed, consisting of the five core diagnostic genes and 333 predicted drugs (Figure 7A). Drug testing revealed that Resveratrol (D000077185) and Quercetin (D011794) exhibited simultaneous interactions with all five core diagnostic markers. Molecular docking studies were conducted with the core targets, resulting in an average binding energy of −7.19 kcal/mol (Figure 7B, Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 7.

Drug-gene interaction network and molecular docking analysis of quercetin with core target proteins in DCM. (A) Drug-gene interaction network for five core genes (TLN1, DSTN, ACTN4, MYH10, NCKAP1). (B) Molecular docking models showing the binding interactions between quercetin and the core proteins ACTN4, DSTN, MYH10, NCKAP1, and TLN1.

DiGs are Related to Immune Function in DCM Patients

Significant negative correlations were observed between core DiGs and immune cell subsets including NK cells, neutrophils, and macrophages, and a significant positive correlation with Endothelial cells and Fibroblasts (Figure 8A). The CIBERSORT algorithm was utilized to analyze the variations in the proportions of 22 immune cell types, focusing on macrophages, NK cells, B cells, and T cells (Supplementary Figure 3A and B). Correlation analysis further indicated the presence of disulfidptosis in regulatory macrophages, T cells, activated NK cells, and M2 macrophages (Figure 8B–F). Additionally, a comparative analysis of immune cell infiltration between the two clusters revealed significantly higher levels of NK cells, CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and M1 macrophages in cluster 2 (Supplementary Figure 4 and 5).

Figure 8.

Correlation analysis between core disulfidptosis-related genes and immune cell infiltration in DCM. (A) Dot plot showing the correlation between the expression levels of five core genes (TLN1, NCKAP1, MYH10, DSTN, ACTN4) and various immune cell types. The size and color of the dots represent the strength and direction of the correlation, respectively. (B–F) Correlation coefficients of immune cell types with the expression of TLN1 (B), NCKAP1 (C), MYH10 (D), DSTN (E), and ACTN4 (F). Positive and negative correlations are represented, and p-values indicate the significance of these associations.

Using GSVA, we identified cluster-specific DEGs revealing distinct functional disparities. Cluster 2 showed upregulation in pathways such as the neurotrophin signaling pathway, insulin signaling pathway, and TGF-β signaling pathway. Conversely, cluster 1 displayed heightened activity in the cardiac muscle contraction pathway (Supplementary Figure 6). Further functional enrichment analysis highlighted unique biological processes associated with each cluster. Cluster 1 was predominantly enriched in processes related to free ubiquitin chain polymerization and T cell proliferation. In contrast, cluster 2 was enriched in pathways including carbohydrate transport, regulation of autophagy, and negative regulation of cellular response to vascular endothelial growth factor stimulus (Supplementary Figure 7).

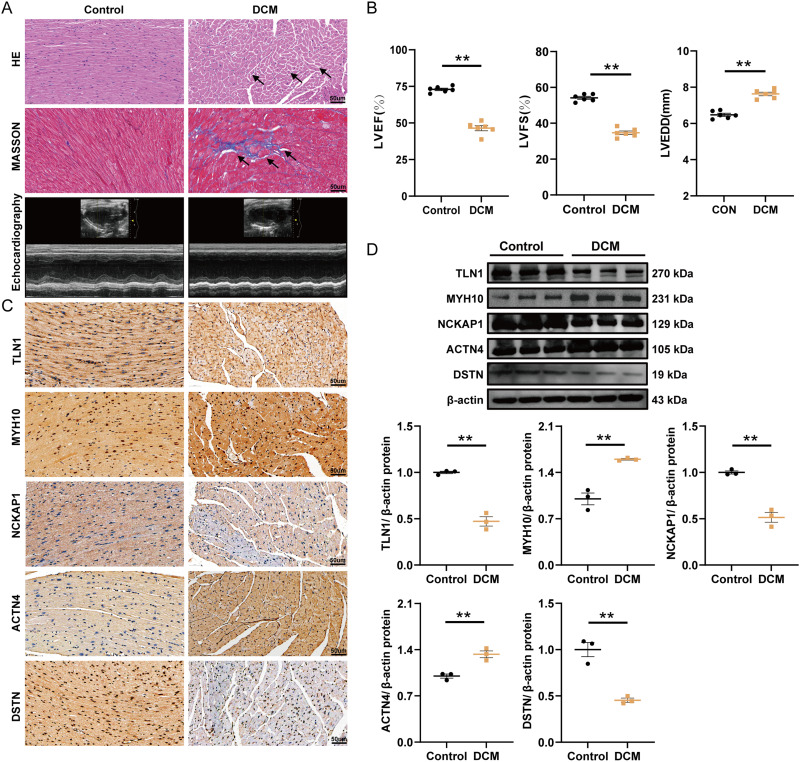

Five DiGs as Diagnostic Markers Were Validated in DCM Animal Model

Validating the bioinformatically identified diagnostic markers in vivo was crucial. To this end, a mouse model of DCM was established (Figure 9A and B). Notably, IHC analysis revealed a significant upregulation of ACTN4 and MYH10, alongside a downregulation of TLN1, DSTN, and NCKAP1 in the myocardial infarction region of the DCM group compared to the control group (Figure 9C). Additionally, WB results corroborated these IHC findings (Figure 9D).

Figure 9.

Histological, echocardiographic, and protein expression analysis of core genes in control and DCM mouse models. (A) Representative images of hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, Masson’s trichrome staining, and echocardiography in control and DCM groups. (B) Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), fractional shortening (LVFS), and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) in control and DCM groups (mean ± SD, n=6, **p≤ 0.01). (C) Immunohistochemical staining of TLN1, MYH10, NCKAP1, ACTN4, and DSTN in myocardial tissue from control and DCM groups (37.5X). (D) Typical bands of proteins in the Western blot experiment (mean ± SD, n=3, **p≤ 0.01).

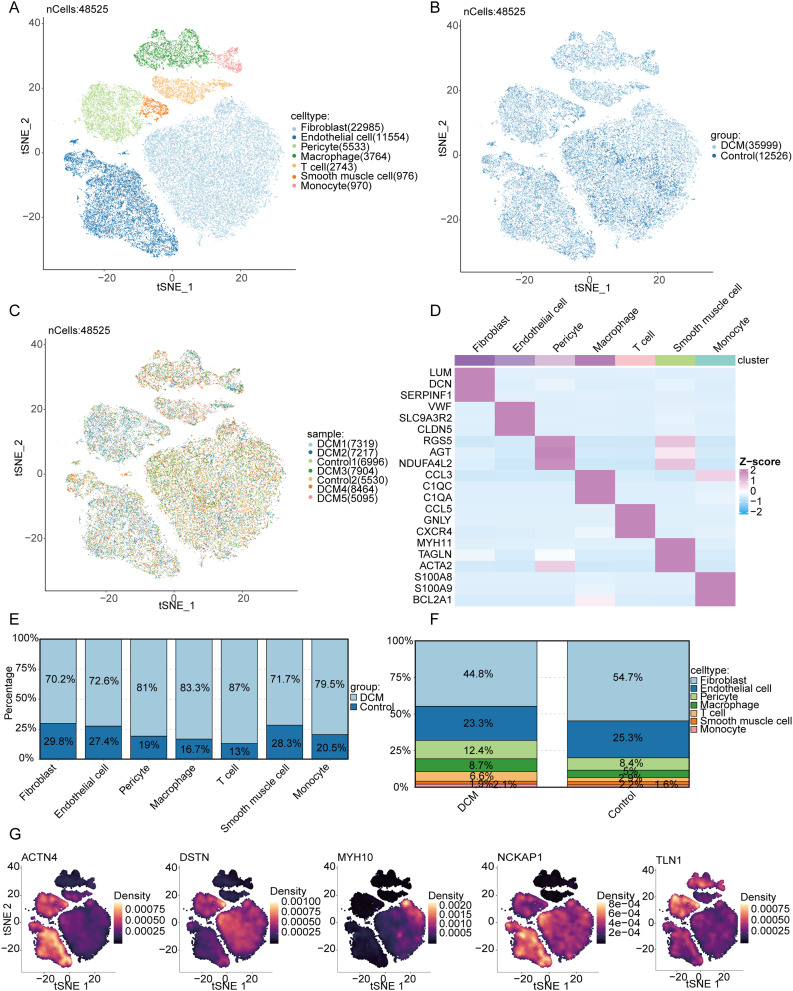

Validation in a Single-Cell Dataset

A total of 48,525 high-quality cardiac cells from the GEO single-cell transcriptomic dataset GSE183852 were included in our analysis. After batch effects were removed using the Harmony algorithm, linear dimensionality reduction was performed via principal component analysis (PCA), followed by nonlinear visualization using the tSNE method. Single-cell clustering was performed using the Louvain algorithm, with cell-type annotations refined via SingleR and validated against CellMarker 2.0 references (Figure 10A). Further analysis stratified by disease status revealed distinct differences in cell distribution between the DCM and control groups, suggesting alterations in cellular composition during myocardial remodeling (Figure 10B). Sample-level hierarchical visualization further validated the consistency and variability across samples (Figure 10C). Differential expression analysis of marker genes allowed us to generate a heatmap of cell type-specific genes (Figure 10D). Comparison of cell proportions revealed a significant increase in fibroblasts and macrophages in the myocardial tissue of DCM patients compared to controls, accompanied by a decrease in endothelial cells and T cells (Figure 10E). At the whole-tissue level, fibroblasts accounted for 44.8% of the cellular composition in the DCM group, significantly higher than the 25.3% observed in the control group (Figure 10F). In addition, we illustrated the expression patterns of key genes related to myocardial structure and cytoskeletal remodeling (ACTN4, DSTN, MYH10, NCKAP1, TLN1) across cell populations. These genes were primarily enriched in fibroblasts and certain immune cells, suggesting their potential involvement in structural abnormalities and fibrosis in DCM myocardial tissue (Figure 10G).

Figure 10.

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of cardiac tissues from DCM and control groups. (A) t-SNE plot showing clustering of 48,525 cardiac cells colored by cell type, identifying seven distinct cell populations. (B) t-SNE plot of the same cells colored by disease group (DCM vs Control). (C) t-SNE plot colored by individual sample origin. (D) Heatmap of representative marker genes across cell types. (E) Bar plots comparing the proportions of each cell type between DCM and control groups. (F) Overall cellular composition differences between DCM and control hearts. (G) Density plots of structural genes (ACTN4, DSTN, MYH10, NCKAP1, TLN1) projected on the t-SNE map, indicating spatial expression patterns.

Based on the previously annotated cell types, we further performed functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in various cell subpopulations (Supplementary Figure 8). For each cell type, representative marker genes were selected, and their expression patterns across subclusters were displayed in a heatmap. GO enrichment analysis revealed distinct biological functions among cell types: fibroblasts were significantly involved in extracellular matrix organization and collagen fibril formation, which are associated with matrix remodeling. Endothelial cells showed enrichment in pathways associated with epithelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Macrophages and monocytes were both enriched in pathways such as regulation of immune response and T cell activation, suggesting their potential roles in the immune-inflammatory microenvironment of DCM. Regarding KEGG pathway analysis, fibroblasts were significantly enriched in protein processing and the TGF-β signaling pathway, which are strongly linked to myocardial fibrosis. Macrophages and monocytes were enriched in inflammatory pathways such as Leishmaniasis and Rheumatoid arthritis. T cells were enriched in T cell receptor signaling and Th1/Th2 cell differentiation pathways.

Core Genes Exhibit Diverse Correlation Patterns with LVEF and LVEDD

Correlation analysis revealed that TLN1 was significantly positively associated with LVEF (r = 0.34, p = 0.0031), while MYH10 showed a significant negative correlation with LVEF (r = −0.40, p = 0.00053). In addition, MYH10 was significantly positively correlated with LVEDD (r = 0.29, p = 0.012). No statistically significant correlations were observed between ACTN4, DSTN, or NCKAP1 and either LVEF or LVEDD (Supplementary Figure 9).

Discussion

DCM is a heterogeneous cardiomyopathy with diverse etiologies and heart failure as its primary clinical manifestation. Despite existing treatment options that can alleviate symptoms to some extent, there are still limitations in controlling disease progression, and the prognosis is poor.1 Disulfidptosis, a recently identified form of programmed cell death triggered by intracellular disulfide accumulation and redox imbalance, has been primarily studied in cancer and neurological disorders, while its role in cardiovascular diseases remains largely unexplored. However, given the high energy dependence of cardiomyocytes and the prevalence of mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic remodeling in DCM, disulfidptosis may represent a novel death mechanism relevant to disease progression. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the role of disulfidptosis in DCM, identify novel molecular targets, and offer new directions for therapeutic intervention.

Our research identified 19 differentially expressed DiGs between control and DCM samples. Functional enrichment analysis highlighted their involvement in immune processes, particularly in the regulation of macrophages, NK cells, and B cells. Based on these 19 DiGs, we stratified the samples into two distinct clusters, referred to as cluster 1 and cluster 2. Cluster 1 demonstrated a higher degree of immune cell infiltration, indicating a more pronounced immune profile compared to cluster 2. Recent research underscores the pivotal role of the immune system in the pathogenesis and progression of DCM. Macrophage polarization can mitigate myocardial fibrosis associated with DCM and potentially reverse ventricular remodeling.34 During the progression of DCM, the activation of B cells, T cells, and NK cells plays a protective role by inhibiting the maturation and migration of inflammatory cells, thereby modulating local cytokine levels and attenuating myocardial injury.35,36 In parallel, our analysis uncovered significant differences in immune cell composition between the two clusters. Future studies should, therefore, focus on elucidating the complex interactions and underlying mechanisms between DiGs and immune cells in the setting of DCM.

As a multidisciplinary approach, machine learning has the potential to extract valuable insights from complex datasets. In our study, the SVM-based predictive model demonstrated the highest accuracy, highlighting its effectiveness in forecasting DCM. The model was developed using five key factors: NCKAP1, TLN1, DSTN, ACTN4, and MYH10. Research has indicated that TLN1 plays a critical role in DCM by maintaining the connection between cardiomyocytes and the extracellular matrix. The loss of TLN1 and TLN2 can lead to reduced β-1 integrin levels, damage to the cardiomyocyte membrane, and eventually DCM and heart failure.37 In DCM, ACTN4 enhances the structural stability of cardiomyocytes and the connections at intercalated discs by upregulating the expression of non-muscle α-actinin, helping cells cope with mechanical stress. This acts as a compensatory mechanism for cardiomyocytes under pathological conditions.38 MYH10 primarily functions in DCM by regulating the expression of contractile proteins in cardiomyocytes. The expression of MYH10 is increased in the cardiomyocytes of heart failure patients, which may be associated with impaired myocardial contractility and ventricular remodeling. However, in the peripheral blood of patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM), MYH10 expression does not show significant differences, suggesting that it may have different mechanisms of action in various stages of the disease or tissue types.39 NCKAP1 plays a role in atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia following vascular injury by regulating the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. It is a key protein targeted by miRNA-214 and contributes to reversing disease progression.40 DSTN, a member of the actin-depolymerizing factor family, has been relatively understudied in the context of DCM. However, its known roles in regulating nuclear morphology and the DNA damage response suggest a potential involvement in DCM pathogenesis. Recent studies have demonstrated that DSTN interacts with SNRK to modulate F-actin depolymerization, thereby preserving nuclear integrity in cardiomyocytes and suppressing aberrant DDR activation.41 Given that nuclear remodeling and genomic instability are hallmark features of DCM progression, DSTN may contribute to disease development by mediating crosstalk between the cytoskeleton and nuclear architecture. Under pathological conditions such as chronic mechanical or oxidative stress, dysregulated DSTN expression or function may exacerbate nuclear stress, chromatin accessibility alterations, and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Therefore, DSTN represents a promising regulator of cardiomyocyte homeostasis in DCM and may serve as a potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target.

The accuracy of the SVM model was validated in the test cohort. Additionally, we constructed a nomogram for DCM diagnosis based on the expression levels of NCKAP1, DSTN, TLN1, ACTN4, and MYH10. This nomogram exhibited substantial predictive value, suggesting its potential for clinical application. To further substantiate these findings, we established a DCM mouse model. WB results demonstrated a significant upregulation of ACTN4 and MYH10 in myocardial tissue, whereas DSTN, TLN1, and NCKAP1 showed marked downregulation. Moreover, IHC analysis of myocardial tissue corroborated these observations. To explore the clinical relevance of the core gene signature, we further analyzed the correlation between gene expression and echocardiographic measures of cardiac function. Notably, TLN1 and MYH10 demonstrated significant associations with LVEF and LVEDD, supporting their potential role as biomarkers that reflect both molecular alterations and functional remodeling in DCM. These findings suggest that integrating gene expression data with imaging phenotypes could enhance disease characterization and stratification. In future work, multimodal models incorporating transcriptomic, imaging, and clinical features may yield more robust diagnostic tools.

MicroRNA (miRNA) mainly influences cardiomyocyte function and cardiac remodeling in DCM by regulating the processes of cardiomyocyte proliferation, apoptosis, and fibrosis, and they have potential value as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.42,43 The ceRNA network analysis revealed interactions between hsa-miR-1207-5p and the genes TLN1 and NCKAP1, miR-1207-5p influences vascular remodeling and plaque stability in cardiovascular diseases by regulating the ADAMTS protein family. Its downregulation is associated with atherosclerosis and unstable angina, which is potentially valuable for early diagnosis.44,45 Research indicates that miR-939-5p is downregulated in the serum exosomes of ischemic heart disease patients, inhibiting NO production by targeting iNOS and affecting angiogenesis, potentially serving as an important regulator of vascular remodeling during myocardial ischemia.46 Additionally, miR-939 is a biomarker for poor prognosis in patients with acute heart failure, and its high expression is associated with ventricular hypertrophy and lower survival rates in heart failure patients.47 MiR-186-5p primarily regulates inflammatory responses and lipid metabolism in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. It participates in atherosclerosis formation by targeting and inhibiting cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), promoting lipid accumulation in macrophages and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, it is also associated with patients with unstable angina.48,49

We used the CTD database to predict drugs related to core DiGs and found common drugs including quercetin and resveratrol. Quercetin and resveratrol are natural plant compounds widely found in fruits, vegetables, and red wine, with various biological activities. Quercetin has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, capable of inhibiting oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress, thereby reducing cardiomyocyte damage and fibrosis, improving cardiac function, and preventing the progression of experimental autoimmune myocarditis (EAM) to DCM.50 Resveratrol has been shown to promote vasodilation and reduce blood pressure by inducing disulfide bond formation at Cys42 of cGMP-dependent protein kinase G1α (PKG1α), thereby improving cardiovascular function.51 Although its role in DCM has not been directly investigated, these findings suggest that resveratrol may exert vascular protective effects under oxidative stress conditions. Both resveratrol and quercetin exhibit potential therapeutic effects in DCM by attenuating fibrosis and enhancing cardiac function. Quercetin primarily acts through inhibition of inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways, whereas resveratrol exerts its effects via modulation of the PKG1α-mediated vascular redox signaling cascade. Through distinct pathological mechanisms, both compounds may suppress DCM progression and hold promise as novel therapeutic strategies and potential drug targets.

Collectively, our results indicate that structural remodeling and immune activation are intricately linked in the development of DCM. Fibroblast proliferation and the elevated expression of cytoskeletal remodeling genes (eg, ACTN4, TLN1, MYH10) indicate ongoing myocardial fibrosis, which likely impairs myocardial compliance and contractile performance. Meanwhile, the enrichment of macrophages and monocytes, along with their involvement in inflammatory pathways, suggests the presence of a pro-inflammatory microenvironment. These processes may not be independent but rather form a positive feedback loop: immune cells can secrete profibrotic factors such as TGF-β to activate fibroblasts, which in turn produce chemokines that sustain inflammation. Through the integration of scRNA-seq, machine learning, and regulatory network analysis, we uncovered potential diagnostic markers and unveiled therapeutic targets involved in the crosstalk between immunity and fibrosis. Future studies should further explore the dynamic crosstalk between immune cells and fibroblasts to uncover the underlying mechanisms of DCM and promote the formulation of targeted precision therapies.

However, our study has several limitations. First, additional clinical datasets from DCM patients are needed to further validate the expression levels and clinical associations of DiGs across broader and more diverse populations. Second, a comprehensive assessment of the predictive model requires access to detailed clinical parameters, including imaging indices and longitudinal prognostic data, which were not uniformly available in the included datasets. Third, although multiple immune deconvolution algorithms were employed, confounding factors such as age and sex could not be adjusted due to the incomplete metadata within the public GEO cohorts, potentially introducing bias in immune infiltration estimates. In addition, although a 5-fold cross-validation strategy was used for LASSO model optimization, a more rigorous nested cross-validation was not implemented due to computational limitations. Nevertheless, the robust diagnostic performance observed in three independent validation cohorts supports the reliability of the model. Lastly, increasing the sample size and integrating well-annotated, prospectively collected datasets in future research will be crucial to improve statistical power, enable multivariable regression analyses, and enhance the translational applicability of our findings.

Conclusions

This study aims to investigate the role of disulfidptosis in DCM and its potential molecular mechanisms. By integrating datasets from multiple GEO databases, the study identified 19 differentially expressed DiGs and classified DCM patients into two distinct immune subtypes based on these genes. A prediction model based on SVM was constructed and validated using a test set, demonstrating high predictive accuracy. Additionally, a CeRNA regulatory network of core genes was established, and potential therapeutic drugs related to core DiGs, such as quercetin and resveratrol, were predicted. Finally, the expression changes of core genes were validated in a DCM animal model, suggesting that core DiGs may serve as potential targets for DCM diagnosis and treatment.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81873486, 82403624), the Science and Technology Development Program of Jiangsu Province-Clinical Frontier Technology(BE2022754), Clinical Medicine Expert Team (Class A) of Jinji Lake Health Talents Program of Suzhou Industrial Park (SZYQTD202102), Suzhou Key Discipline for Medicine (SZXK202129), Demonstration of Scientific and Technological Innovation Project (SKY2021002), Suzhou Dedicated Project on Diagnosis and Treatment Technology of Major Diseases (LCZX202132), Research on Collaborative Innovation of medical engineering combination (SZM2021014), Research on Collaborative Innovation of medical engineering combination (SZM2022003), Suzhou Key Laboratory of Diagnosis and Treatment of Panvascular Diseases (SZS2023021), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20240437), Suzhou Science and Education Youth Science and Technology Project (KJXW2023086), Anhui clinical medical research transformation project (202304295107020117, 202304295107020087, 202304295107020083), Anhui provincial health research project (AHWJ2022c008), Anhui Province University Research Project (2024AH051883), Fuyang key research and development program project clinical medical research transformation project (FK20245525), 2024 Scientific Research Project of Fuyang Health Commission (FYZC2024-002).

Abbreviations

ACTN4, Alpha actinin 4; AUC, Area Under the Curve; CeRNA, Competing Endogenous RNA; CNV, Copy number variation; DiGs, Disulfidptosis-related genes; DCA, Decision Curve Analysis; DCM, Dilated cardiomyopathy; DSTN, Destrin; FDR, False discovery rate; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; GLM, Generalized Linear Model; GSVA, Gene Set Variation Analysis; MYH10, Myosin-10; NCKAP1, NCK associated protein 1; RF, Random Forest; ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic; SVM, Support Vector Machine; TLN1, Talin-1; XGB, Extreme Gradient Boosting.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

The study was based on publicly available, de-identified datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, which had obtained ethical approval and informed consent in the original studies. This exemption was confirmed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Taihe County People’s Hospital affiliated with Wannan Medical College (Approval No. 2023-09-2022-34). All animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Animal Ethics Committee of Suzhou University, Soochow University, China (reference number: 202408A0374).

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Jili Fan and Xiaohong Bo have contributed equally to the work and share first authorship.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Stephane H, Neal KL, Carsten T, Karin K. Dilated cardiomyopathy: causes, mechanisms, and current and future treatment approaches. Lancet. 2023;402(10406):998–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vissing C, Espersen K, Mills H, et al. Family Screening in Dilated Cardiomyopathy: prevalence, Incidence, and Potential for Limiting Follow-Up. JACC Heart Fail. 2022;10(11):792–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2022.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weintraub RG, Semsarian C, Macdonald P. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2017;390(10092):400–414. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31713-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eldemire R, Mestroni L, Taylor MRG. Genetics of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Annu Rev Med. 2024;75(1):417–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-052422-020535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Japp A, Gulati A, Cook S, Cowie M, Prasad S. The Diagnosis and Evaluation of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(25):2996–3010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Li E, Zou J, et al. Ubiquitin Ligase RBX2/SAG Regulates Mitochondrial Ubiquitination and Mitophagy. Circulation Res. 2024;135(3):e39–e56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.124.324285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang Y, Feng M, Su Y, et al. Jmjd4 Facilitates Pkm2 Degradation in Cardiomyocytes and Is Protective Against Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2023;147(22):1684–1704. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.064121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haesen S, Jager M, Brillouet A, et al. Pyridoxamine Limits Cardiac Dysfunction in a Rat Model of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Antioxidants. 2024;13(1). doi: 10.3390/antiox13010112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng C, Duan F, Hu J, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101523. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Zhao M, Zheng Z, et al. TRPA1 deficiency aggravates dilated cardiomyopathy by promoting S100A8 expression to induce M1 macrophage polarization in rats. FASEB j. 2023;37(6):e22982. doi: 10.1096/fj.202202079RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machesky L. Deadly actin collapse by disulfidptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25(3):375–376. doi: 10.1038/s41556-023-01100-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Nie L, Zhang Y, et al. Actin cytoskeleton vulnerability to disulfide stress mediates disulfidptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25(3):404–414. doi: 10.1038/s41556-023-01091-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu W, Jin D, Zhang Y, et al. Provoking tumor disulfidptosis by single-atom nanozyme via regulating cellular energy supply and reducing power. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):4877. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-60015-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao S, Zhuang H, Ji W, Cheng C, Liu Y. Identification of Disulfidptosis-Related Genes in Ischemic Stroke by Combining Single-Cell Sequencing, Machine Learning Algorithms, and In Vitro Experiments. Neuromolecular Med. 2024;26(1):39. doi: 10.1007/s12017-024-08804-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu D, Zhang X, Fang Y, et al. Identification of a lactylation-related gene signature as the novel biomarkers for early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;282(Pt 6):137431. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan WLW, Anene-Nzelu CG, Wong E, et al. Epigenomes of Human Hearts Reveal New Genetic Variants Relevant for Cardiac Disease and Phenotype. Circ Res. 2020;127(6):761–777. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Morley M, Brandimarto J, et al. RNA-Seq identifies novel myocardial gene expression signatures of heart failure. Genomics. 2015;105(2):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ameling S, Bhardwaj G, Hammer E, et al. Changes of myocardial gene expression and protein composition in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy after immunoadsorption with subsequent immunoglobulin substitution. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111(5):53. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0569-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi T, Sumida TS, Satoh M, et al. Cardiac dopamine D1 receptor triggers ventricular arrhythmia in chronic heart failure. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4364. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18128-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clough E, Barrett TJM. The Gene Expression Omnibus Database. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.). 2016;1418:93–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leek J, Johnson W, Parker H, Jaffe A, Storey JJB. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2012;28(6):882–883. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Cao C, Ma Q, et al. RNA-seq analyses of multiple meristems of soybean: novel and alternative transcripts, evolutionary and functional implications. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(169):169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu K. Become Competent in Generating RNA-Seq Heat Maps in One Day for Novices Without Prior R Experience. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2239:269–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinf. 2013;14(7). doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanda E, Okami S, Okada M, et al. Machine Learning Models Predicting Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes and Mortality in Patients with Hyperkalemia. Nutrients. 2022;14(21). doi: 10.3390/nu14214614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu H, Ding S, Ning X, et al. Integrated bioinformatics and validation reveal TMEM45A in systemic lupus erythematosus regulating atrial fibrosis in atrial fibrillation. Mol Med. 2025;31(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s10020-025-01162-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rigatti SJJ. Random Forest. J Insur Med. 2017;47(1):31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmoudi Z, Chenaghlou M, Zare H, Safaei N, Yousefi MJF. Heart failure: a prevalence-based and model-based cost analysis. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2023;10(1239719). doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1239719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman A, Liu C, Green M, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nature Methods. 2015;12(5):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wenjun Y, Dawei D, Yang L, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific Tbk1 deletion aggravated chronic doxorubicin cardiotoxicity via inhibition of mitophagy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;222:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu S, Qin J, Ding M, et al. Bulk integrated single-cell-spatial transcriptomics reveals the impact of preoperative chemotherapy on cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor cells in colorectal cancer, and construction of related predictive models using machine learning. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2025;1871(1):167535. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korsunsky I, Millard N, Fan J, et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat Methods. 2019;16(12):1289–1296. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0619-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu C, Li T, Xu Y, et al. CellMarker 2.0: an updated database of manually curated cell markers in human/mouse and web tools based on scRNA-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D870–d876. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong N, Mohan J, Kopecky B, et al. Resident cardiac macrophages mediate adaptive myocardial remodeling. Immunity. 2021;54(9):2072–2088.e2077. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Cheng L, Huang Y, Feng F, Li Y. Immune cells and related cytokines in dilated cardiomyopathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;171(116159):116159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sikking MA, Harding D, Henkens M, et al. Cytotoxic T Cells Drive Outcome in Inflammatory Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2024;135(12):1193–1195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.124.325183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manso A, Okada H, Sakamoto F, et al. Loss of mouse cardiomyocyte talin-1 and talin-2 leads to β-1 integrin reduction, costameric instability, and dilated cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(30):E6250–E6259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701416114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cetinkaya A, Berge B, Troidl K, et al. αRadixin Relocalization and Nonmuscle -Actinin Expression Are Features of Remodeling Cardiomyocytes in Adult Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Dis Markers. 2020;2020:9356738. doi: 10.1155/2020/9356738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dehghani K, Stanek A, Atashi F, et al. CCND1 Overexpression in Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy: a Promising Biomarker? Genes. 2023;14(6):1243. doi: 10.3390/genes14061243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Afzal TA, Luong LA, Chen D, et al. NCK Associated Protein 1 Modulated by miRNA-214 Determines Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Migration, Proliferation, and Neointima Hyperplasia. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanczyk PJ, Tatekoshi Y, Shapiro JS, et al. DNA Damage and Nuclear Morphological Changes in Cardiac Hypertrophy Are Mediated by SNRK Through Actin Depolymerization. Circulation. 2023;148(20):1582–1592. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.066002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng Z, Xia L, Fan S, et al. Circular RNA CircMAP3K5 Acts as a MicroRNA-22-3p Sponge to Promote Resolution of Intimal Hyperplasia Via TET2-Mediated Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation. Circulation. 2021;143(4):354–371. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirai K, Ousaka D, Fukushima Y, et al. Cardiosphere-derived exosomal microRNAs for myocardial repair in pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Trans Med. 2020;12(573). doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb3336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raitoharju E, Seppälä I, Oksala N, et al. Blood microRNA profile associates with the levels of serum lipids and metabolites associated with glucose metabolism and insulin resistance and pinpoints pathways underlying metabolic syndrome: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Mol Cellular Endocrinol. 2014;391(1–2):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cui Y, Song J, Li S, Lee C, Zhang F, HJIhj C. Plasmatic MicroRNA Signatures in Elderly People with Stable and Unstable Angina. International Heart Journal. 2018;59(1):43–50. doi: 10.1536/ihj.17-063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, Liao Y, Gao L, et al. Coronary Serum Exosomes Derived from Patients with Myocardial Ischemia Regulate Angiogenesis through the miR-939-mediated Nitric Oxide Signaling Pathway. Theranostics. 2018;8(8):2079–2093. doi: 10.7150/thno.21895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su Y, Sun Y, Tang Y, et al. Circulating miR-19b-3p as a Novel Prognostic Biomarker for Acute Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(20):e022304. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Gonzalo-Calvo D, Martínez-Camblor P, Bär C, et al. Improved cardiovascular risk prediction in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis using machine learning modeling and circulating microribonucleic acids. Theranostics. 2020;10(19):8665–8676. doi: 10.7150/thno.46123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samadishadlou M, Rahbarghazi R, Piryaei Z, et al. Unlocking the potential of microRNAs: machine learning identifies key biomarkers for myocardial infarction diagnosis. Cardiovascular Diabetol. 2023;22(1):247. doi: 10.1186/s12933-023-01957-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Javadi B, Sahebkar A. Natural products with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities against autoimmune myocarditis. Pharmacol Res. 2017;124:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prysyazhna O, Wolhuter K, Switzer C, et al. Blood Pressure-Lowering by the Antioxidant Resveratrol Is Counterintuitively Mediated by Oxidation of cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Circulation. 2019;140(2):126–137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.