Abstract

The literature on migration during armed confiict is abundant. Yet, the questions of highest policy relevance—how many people will leave because of a confiict and how many more people will be living outside a country because of a confiict—are not well addressed. This article explores these questions using an agent-based model, a computational simulation that allows us to connect armed confiict to individual behavioral changes and then to aggregate migration fiows and migrant stocks. With detailed data from Nepal during the 1996–2006 confiict, we find that out-migration rates actually decrease on average, largely due to a prior decrease in return migration. Regardless, the stock of migrants outside the country increases modestly during that period. Broadly, this study demonstrates that population dynamics are inherent to and necessary for understanding confiict-related migration. We conclude with a discussion of the generalizability and policy implications of this study.

Introduction

Armed conflicts have been widespread throughout human history and a prominent topic of concern in the public, political, and academic spheres for centuries. While there is an on-going debate about whether this phenomenon is increasing in frequency and severity, it is nonetheless highly likely, and unfortunate, that armed conflicts will continue in coming decades (Human Security Report Project 2014; Pettersson and Eck 2018). We estimate that in 2018, over three billion people (about 42 percent of the world population) lived in countries experiencing armed conflict on their territory.1 Given that migration and other demographic behaviors of these three billion people have substantial influence on human well-being and population distribution and change on a global scale, it is imperative, now as ever, to better understand the migration consequences of armed conflict.

Migration during armed conflict is a long-standing international policy concern, even before the creation of the 1951 Refugee Convention (FitzGerald and Arar 2018). Refugees and asylum seekers have become an even higher priority topic in policy and public discussion in the wake of the large and mostly unanticipated movement of Syrians into Europe and unaccompanied Central American minors into the United States in recent years, the first fleeing conflict and the second fleeing violence so extreme as to amount to localized conflict. In this context, policymakers are concerned with anticipating the potential shock of large numbers of incoming migrants. They need not understand whether any individual is more likely to leave their country, but would be best served by knowing aggregates, such as—how many out-migrants can we expect to leave an area experiencing armed conflict? This study seeks to contribute to understanding just that.

With an almost 50-year history of armed conflict and migration studies, the field has already delved into such questions. However, until recently, the theoretical and methodological tools were not particularly well-designed to address the policy-relevant question of how much armed conflict influences macrolevel migration stocks and flows. At face value, a straightforward count of people who move during a conflict should answer our key question. But the ability to count all individuals who out-migrate due to a conflict is stymied by imperfect systems to enumerate such individuals and the political nature of refugee status approvals. Such counts also cannot separate the additional migration due to a conflict from the migration that would have occurred had the conflict not broken out. In many conflict-affected countries, rates of migration are in fact very high prior to hostilities. What we do not yet understand, and what is critical for informed policy-making is the question of—how many more or fewer migrants can we expect to leave an area if a conflict begins (migration rates or migration flow) and how many more or fewer migrants will be outside their country of origin (migrant stock) than if a conflict did not happen in the same area? For most effective policy relevance, these questions should relate to stocks and flows of all migrants, regardless of refugee and other documented status.

In this paper, we address these questions. Because both migrant stock and flow are integrally related to return migration, we also examine return rates. We approach all these constituent pieces of macrolevel migration dynamics using a relatively new method—agent-based modeling (ABM). The ABM strategy allows us to examine how conflict affects individual-level demographic behaviors, and how those individual-level behaviors interact and combine over time to create macrolevel migration rates. It also allows us to simulate counterfactual scenarios of conflict and no conflict, creating the possibility to compare results and assess the actual influence of the conflict on migration rates, even in an area where migration already occurs in the absence of conflict.

We implement this ABM strategy in the rural Chitwan Valley of Nepal, with detailed longitudinal survey data and records of violent and political events that comprised the armed conflict between Maoist guerrilla and Government of Nepal forces from 1996 to 2006. Results show that, counterintuitively, the armed conflict actually decreased out-migration rates from Chitwan. A series of simulation experiments indicate that the primary explanation for this surprising finding is that the conflict decreased return migration rates which then affected subsequent out-migration. Even with both measures of migrant flow decreasing, we find a slightly increased number of people living outside the study area.

This is the first study that we are aware of that connects armed conflict to individual-level behaviors and then to subsequent macrolevel migration dynamics. We view this work as complementing the existing scholarship on armed conflict and migration by addressing new questions of macrolevel stocks and flows, and with the addition of return migration as a key piece of the migration dynamics puzzle. In addition to these contributions to the academic literature on migration during armed conflict, the new perspectives and evidence that we present here also suggest different angles for policy attention, in during- and postconflict settings. We discuss these findings and interpretation further in the conclusion.

Background: Studies of migration during armed conflict

There is a significant and decades-long history of scholarship on migration during armed conflict. Many earlier studies from around the world show that there are high rates of out-migration during armed conflicts (Apodaca 1998; Clark 1989; Davenport, Moore, and Poe 2003; Melander and Öberg 2006; Moore and Shellman 2004; Schmeidl 1997; Stanley 1987; Weiner 1996; Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo 1989). These studies largely follow a threat-based decision model, which is ultimately based on push–pull reasoning regarding migration—potential migrants base their decision to migrate on perceived threat to their personal security; when the perceived threat increases beyond an acceptable level, this serves as a push factor and the individual and/or household will migrate away.

While the threat-based model is entirely logical, scholars have also proposed theoretical advances, supported by empirical evidence, that incorporate other factors into the complexity of decision making about migration during armed conflict. The concept of mixed migration, which has gained theoretical traction and empirical support in recent decades, suggests that both conflict-related factors and nonconflict related factors influence migration during armed conflict (Boehm 2011; Crush, Chikanda, and Tawodzera 2015; Van Hear 2009; Vullnetari 2012; Williams 2015). Another complexity is introduced with studies indicating that armed conflict disrupts life and livelihoods in many ways, from access to markets, commodity prices, and property damage (Bundervoet and Verwimp 2005; Collier 1999; Gebre 2002; Justino 2006; Mack 2005; Shemyakina 2011; Verpoorten 2005), to access to schooling and availability of health services, and to changes in marital and fertility behaviors (Agadjanian and Prata 2001, 2002; Heuveline and Poch 2007; Lindstrom and Berhanu 1999b; Mack 2005; Shemyakina 2009; Williams et al. 2012). Given that economic, social, and demographic factors are key predictors of migration, it follows that conflict-induced changes to these factors can lead to changes in out-migration behavior, a matter explicitly addressed by Lindley (2010).

Despite this large body of literature, important questions remain. First, the threat-based decisions and push/pull theoretical models, while validated around the world, would suggest that all people exposed to armed conflict will out-migrate and not return until cessation of hostilities. This is far from the case; indeed, a careful examination of population statistics reveals that a large proportion, if not the majority, of people often do not migrate away. For example, at the height of hostilities in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Darfur, a total of 90 percent of Afghans, 82 percent of Iraqis, and 43 percent of Darfuris were not registered as displaced (either as refugees, asylum seekers, or internally displaced persons).

Second, the threat-based model and most of the supportive empirical research address the microlevel, taken to encompass the individual, household, and even community calculus of migration during armed conflict. The question they address is—will individuals and/or households be more likely to leave?—and studies accordingly focus on the microlevel. While undoubtedly important, microlevel studies cannot be straightforwardly applied to understanding the aggregate, macrolevel outcome. Assuming that aggregate rates are a linear summation of individual likelihoods is an ecological fallacy and could produce misleading results. On the one hand, studies that focus on the microlevel are useful for examining the impact of armed conflict on migration, but not useful for obtaining aggregate-level estimates. On the other hand, studies at the macrolevel can obtain aggregate-level counts of migration but cannot estimate to what extent that migration is influenced by armed conflict. Both types of studies are important feedstock for examining the question of how armed conflict influences aggregate migration stocks and flows—and we use insights from both of them for our study here.

Conceptual framework

The framework for this study is based on the idea that armed conflicts do not just act on people, but they change how people act, as they adopt new behaviors to cope with dramatic changes to their context. Of course, armed conflict is not the only macrolevel phenomenon that changes the context within which people live and make behavioral decisions; climate change, natural hazards, political crises, and social change, in general, can be characterized in the same way. The conceptual framework we present here is relatively broad and can certainly be adapted to analyze population responses to these other phenomena.

One of the new behaviors that might be adopted in response to contextual change is migration, but armed conflict also affects marriage, childbearing, and many others. These new behavioral patterns at the microlevel can aggregate to create macrolevel demographic dynamics, such as migration rates, marriage rates, fertility rates, population growth, etc. Kingsley Davis wrote, over half a century ago,

The process of demographic change and response is not only continuous but also reflexive and behavioral-reflexive in the sense that a change in one component is eventually altered by the change it has induced in other components; behavioral in the sense that the process involves human decisions in the pursuit of goals with varying means and conditions. As a consequence, the subject has a frightening complexity-so much so that the temptation is great to escape from its intricacies. (Davis 1963, 345)

The second key component of our framework is that, even during an armed conflict, there are numerous and complex motivations for microlevel behavioral changes. In addition to violence and political instability, other social, economic, and political norms and factors will influence individual behavior. Further, as in periods of relative peace, we expect there to be individual-, household-, and community-level variation in how conflict and these other factors influence behaviors. This creates a complex system of interactions between individuals, the households, and communities in which they live, and the broader social, economic, and political context.

With these considerations in mind, we present our conceptual framework in Figure 1 as one way to begin sorting through the “frightening complexities” of understanding demographic change during armed conflict. The key components of this framework are (A) armed conflict will have direct effects on demographic behaviors at the microlevel (shown with a dashed line); (B) even in the context of conflict, individual, household, and community characteristics will also be important determinants of demographic behaviors and will affect these behaviors through similar mechanisms as during periods of relative peace; that is, in the absence of conflict (shown with solid lines); (C) in the context of conflict, individual, household, and community characteristics will moderate the impact of armed conflict on demographic behaviors (shown with dotted lines); (D) systematic variation in microlevel behaviors during conflict will have important consequences for population composition and dynamics at the macrolevel in the short- and long-term following armed conflict (shown with dash–dot lines).

FIGURE 1. Conceptual framework.

Although this conceptual framework and the pathways through which conflict affects macrolevel population patterns apply to any behavior, the primary topic of this study is migration. As such, in the top right corner of the conceptual diagram, we substitute “migration dynamics” for “population composition and dynamics” and from here, we continue our discussion with that focus. In addition, given existing work on how conflict affects individual migration behavior (Czaika and Kis-Katos 2009; Melander and Öberg 2006; Schmeidl 1997; Williams 2013, 2015; Williams et al. 2012), shown with arrows A, B, and C in our diagram, our aim here is to understand how those behaviors combine to form macrolevel dynamics, or arrow D.

The evidence we cite above helps us to understand how conflict affects migration directly and independent of other characteristics and behaviors. However, if we take our conceptual diagram broadly, this forces us to consider that armed conflict also has direct effects on other behaviors, such as marriage, childbearing, and education (Jayaraman, Gebreselassie, and Chandrasekhar 2008; Lester 1993; Lindstrom and Berhanu 1999a; Saxena, Kulczycki, and Jurdi 2004; Shemyakina 2011). We also know from existing research that various time-varying characteristics, such as marital, childbearing, and education status, influence individual migration behaviors (Massey and Espinosa 1997; VanWey 2005; Williams 2009).

With this in mind, our conceptual diagram needs to be understood as describing a single time step that must be placed in a longitudinal sequence of time steps. For example, in onetime step, armed conflict might have a direct effect on the out-migration of one person. Consider a second person who does not migrate in that time step, but instead, due to their various characteristics, the armed conflict influenced them to get married. For this second person, we follow the D arrow from individual behavior (get married) to individual characteristics (married). In the next time step, we can follow the B arrow from individual characteristic (married) to individual behavior (out-migration). With this longitudinal perspective, we can say that different demographic and social behaviors interact over time, to create indirect relationships between conflict and our outcome of interest. In other words, for our example person, this indirect relationship might look like: conflict → marriage → out-migration.

In addition, one person’s behavior can affect the behavior of those around them. For example, if the conflict influences a person to out-migrate in one time step (arrow A), then their migration and resulting remittances will influence the household characteristics and community context of all others in their household and community (arrow D) and subsequently influence the out-migration behavior of those others in the next time step (arrow B). These interactions between behaviors and between people over time are the reason that linear aggregation of microlevel behaviors (such as those obtained from regression analyses of individual behavioral likelihoods) is not sufficient to predict macrolevel trends (Auchincloss and Diez Roux 2008).

Accordingly, our conceptual framework (and empirical model) treats a population as an interactive complex system that changes over time. In this system, humans interact with others, behaviors influence the likelihood of subsequent behaviors, and the characteristics of individuals change over time. It is all these interactions together that create macrodemographic patterns, including migration. In the next section, we describe our empirical strategy, ABM, that is uniquely designed to examine the influence of armed conflict on migration rates within the context of an interactive, complex, and longitudinally dynamic system.

Methods

Agent-based modeling

Agent-based models are the most recent addition to a long history of computational microsimulation in the demographic sciences. Generally, demographic microsimulation models use data about individuals, apply a set of rules that govern their behaviors, and examine the subsequent demographic patterns, often at the aggregate level. Such strategies have long been the backbone of population projections, where the aggregate pattern of interest is the population size and age-sex composition, simulated with increasingly sophisticated methods over time (Azose and Raftery 2019; Azose, Ševčíková, and Raftery 2016). Demographic microsimulations used for projection are commonly referred to as “top-down” models, whereby macrolevel rates (for fertility, mortality, etc.) are used as behavioral rules, they are applied to individuals, and the behaviors of the individuals are calculated according to their attributes (such as age and sex). In the present day, these are most often “dynamic” models, meaning that individuals’ attributes (e.g., age) can change over time, their behaviors are calculated at each of a series of time steps (e.g., years), and their attributes are accordingly updated at each time step. In the case of armed conflict, Heuveline (2015) recently used a clever adaptation of demographic microsimulation by forward- and backward projecting population data to estimate conflict-related mortality under the Khmer Rouge regime in the late 1970s Cambodia.

ABM, which we use in this paper, builds on the dynamic demographic microsimulation approach, but with one important addition: agent interdependence. Whereas the behavioral rules (rates) in demographic microsimulations treat individuals as socially isolated pillars, the behavioral rules in ABMs are predictive equations that allow individuals to interact, so that their behaviors are influenced by both their own attributes and the behaviors and attributes of others. It is for this reason that ABMs are referred to as “bottom-up” models. This interdependence of individuals creates the possibility of “emergence,” which means macrolevel patterns that are qualitatively different from and not readily apparent from a simple summation of individual behaviors or attributes. For more discussion on ABMs, how they are used, and how they are different from demographic microsimulation; see Macy (2015); Macy and Willer (2002); and Zagheni (2015).

An important aspect of the ABM approach is that because it is a computational simulation, it can be used as an “experimental laboratory” of sorts (Williams, O’Brien, and Yao 2016). Multiple experimental scenarios can be simulated with an ABM, and the macrodemographic patterns of each scenario can be compared to determine the influence of the experimental treatment. This experimental approach is useful for testing theory and understanding the mechanisms that contributed to the macrolevel pattern observed. It is also particularly well-suited for examining the effect of a macrolevel event (like an armed conflict), on aggregate-level patterns (like a migration rate) that is difficult or impossible to do with observational data and standard statistical procedures. A key example, due to Entwisle, Verdery, and Williams (2020), uses an ABM to simulate macrolevel floods and droughts and the microlevel behavioral responses and assesses consequent patterns of migration at the aggregate level. Quite contrary to general expectations about climate change, Entwisle and colleagues find that out-migration decreased during climate events, and this was partially due to a decrease in return migration—a finding that is echoed in our analysis of armed conflict.

Given these important properties of ABMs (e.g., connecting dynamic microbehaviors to aggregate-level patterns, the possibility of emergence, and the examination of experimental or contrapositive scenarios), they are emerging as powerful analytical tools in several areas of social science, including epidemiology, demography, sociology, geography, and archaeology (An et al. 2005; Axtell et al. 2002; Bruch and Mare 2006; Entwisle et al. 2008, 2016, Entwisle, Verdery, and Williams 2020; Epstein 1999; Grow and Van Bavel 2015, 2017; Parker et al. 2003) and there have been two articles advocating for their use in forced migration studies (Edwards 2008; Williams, O’Brien, and Yao 2016). Several studies stand out for using ABMs to study conflict-related migration, in particular: movement of refugees once they have fled their original residence (Suleimenova, Bell, and Groen 2017), the relationship between food insecurity and conflict-related migration (Campos, Suleimenova, and Groen 2019), the distribution of refugee arrivals across camps (Groen 2016), and the relationship between rebel movement and refugees in Aleppo, Syria (Sokolowski, Banks, and Hayes 2014). However, to our knowledge, ABMs have not yet been applied to analysis of armed conflict, macrodemographic dynamics, and migration stocks and flows.

Overview of the Chitwan ABM

We describe our ABM here, with the aim to provide enough model design information for our reader to understand the general functioning of the ABM and the details of how the migration portion works, reflecting the focus of this article. Full details of model design that are sufficient to enable replicability are presented in the online Appendix containing Supporting Information. Model structure flowcharts are presented in Figures A1.2–A1.8 of Online Appendix A1, standard description following ODD protocols (Grimm et al. 2006; 2010) in Online Appendix A2, and model equations in Online Appendix A3. Further discussion of model design and testing can also be found in Williams, O’Brien, and Yao (2016).

Setting

Our ABM is based on survey data from the Chitwan Valley of Nepal during the armed conflict of 1996–2006. Chitwan district borders India and is about 100 miles from Kathmandu. As shown in Figure A1.1 in the online Appendix A1 containing Supporting Information, there is one large city, Narayanghat, and the rest of the population lives in small rural villages. In 1996 (the beginning of our study period), about 80 percent of the households in the study area were engaged in subsistence agriculture as their primary livelihood, with some increases in market agriculture since then. Both domestic and international migration in this area is common, with almost 1,000 out-migrations (out of about 5,000 people) in 1997 alone. Many of these migrations are short term, and some of them reflect the same person moving out, returning, and moving out again in the same year. Most of this migration is used as a livelihood strategy to supplement farm and locally based income, and is thus primarily undertaken by individuals (instead of households), temporary, with relatively short periods of stay outside the study period, and with high rates of return.

The conflict in Nepal began in 1996 when the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) declared a “People’s War” with the aim to unseat the monarchy and install a democratic republic. They charged the government with poor administration, corruption, unfair taxation, and neglect of poor rural areas of the country. The earlier stages of the conflict were contained in several midwestern districts and aimed at damage to government installations. From mid-2000, however, the Maoists progressively expanded their campaign nationwide. In 2001, the Nepalese government responded by creating a special armed police force to fight the Maoists, beginning the nationwide conflict. After that, the government generally maintained control of district headquarters, cities, and large towns, and the Maoists controlled much of the rugged countryside, where communication and transportation are difficult. By 2001, they were operating in 68 of Nepal’s 75 administrative districts, including Chitwan where our study is based. Serious peace talks commenced in June 2006 and in November of that year the government and Maoists signed a comprehensive peace agreement officially ending the conflict.

Because this armed conflict was staged mainly using guerrilla tactics, there was generally no frontline, it was largely unknown where fighting would break out, and civilians were often unintentionally caught up in firefights and bomb blasts. They also experienced torture, extra-judicial killings, abductions, arrests without warrants, house raids, forced conscription, billeting, extortion, and general strikes that disrupted economic and social activity across the country (Hutt 2004; Pettigrew 2003, 2004). Three ceasefires were called and subsequently broken. The government declared a state of emergency, instituting martial law twice. From 2000 until the end of 2006, there were an estimated 17,000 fatalities due to the conflict and responsibility for these deaths lies with both the Maoists and the government security forces (estimates by Informal Service Sector, Nepal). Survey and ethnographic analyses indicate that most people felt continuously threatened and adjusted their daily activities accordingly (Axinn et al. 2013; Hutt 2004; Pettigrew 2003, 2004; Pettigrew and Adhikari 2009; Williams, Ghimire, and Snedker 2018). Other studies show that the conflict influenced migration, contraceptive use, marriage, and mental health in the Chitwan area and that these influences differed by community context, gender, age, marital status, and education (Axinn et al. 2013; Williams 2013, 2015; Williams et al. 2012).

While the conflict in Nepal received much less global media attention than the violence in Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, it is arguably more representative of present-day conflicts around the world. The average fatality rate of the Nepal conflict places it at moderate intensity, less than those of the wars in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq at the height of hostilities, but greater than many of the minor conflicts in recent decades (Pettersson, Högbladh, and Öberg 2019).

Data

We use survey data from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS) to design the hypothetical population and the behavioral rules in our Chitwan ABM. The CVFS is a multidisciplinary study of over 5,000 persons in western Chitwan (Axinn, Barber, and Ghimire 1997; Axinn, Pearce, and Ghimire 1999; Barber et al. 1997) that is publicly available at www.ICPSR.org. The survey is a representative sample of neighborhoods in Chitwan in which full censuses of individuals between the ages of 15 and 59 were taken. The CVFS contains several linked datasets, including an individual interview and life history calendar, a prospective demographic event registry that has been collected monthly since 1997, and neighborhood history calendars collected in 1995 and 2006. Because the data were collected before, during, and after armed conflict, the CVFS provides a rare opportunity to use the observed effects of armed conflict on migration and other individual behaviors. Data from the CVFS are paired with data on violent events (such as bomb blasts and gun battles) compiled by the South Asia Terrorism portal (www.satp.org), an Indian NGO that compiles records of all violent events in Nepal. We also collected data on political events related to the conflict, such as strikes and protests, states of emergency, and instances of major government instability.

Model design

The Chitwan ABM is organized into modules for individuals, households, and neighborhoods. Each module (shown with flowcharts in Figures A1.2–A1.8 in the online appendix containing Supporting Information) contains a set of probabilistic decisions and/or deterministic processes that each individual, household, and neighborhood make/undergo. At the beginning of each simulated month, individual agents go through the individual module, which is a series of behavioral decisions. Individual agents experience any of several demographic, social, and economic events/behaviors, including marriage, childbirth, out-migration, return-migration, death, education, and salaried work. Figure 2 shows the flow of the individual monthly module. The module first determines whether the agent dies this month, in which case he leaves the population. If the agent lives, the model runs through sequential behavioral modules to determine if the agent migrates marries, becomes pregnant, migrates, etc.

FIGURE 2. Flow diagram for the individual module of the Chitwan ABM.

The household and neighborhood modules are run at the end of each year (after 12 monthly individual module time steps). Households can die (if all the members of the household die) and accrue assets, proxied by summing agricultural income and the wages and salaries of individual household members during the year and subtracting consumption for each household member and costs for migration and purchases of land and livestock. Subfamilies can be created when adult children are married, subfamilies can split from the original household, and these new households can purchase land and livestock as per prescribed rules. The neighborhood module does not allow neighborhoods to behave, but simply records updated neighborhood characteristics, such as the number of migrants currently away.

Some ABM rules are additive or deterministic. For example, a pregnant woman progresses one month in her pregnancy for each one-month time step, and household assets are a simple summation of annual incomes. Other behavioral rules, particularly those for demographic behaviors like out-migration, return migration, marriage, and childbearing, are more complicated and rely on probabilistic and stochastic processes. As an example, the out-migration behavior rule is based on a regression equation estimated from the CVFS survey data and based on published studies of individual-level out-migration during the conflict in Chitwan (Williams 2013, 2015; Williams et al. 2012). These studies define out-migration as leaving the Chitwan District, where some migrants move to other parts of Nepal and others move outside the country and our ABM similarly allows for migration within Nepal (outside Chitwan District) and internationally. As the equations in supplementary online material Appendix A1 show, men and women who are over the age of 16 and who are not currently migrants are considered at risk to out-migrate. Using the regression equations, the ABM calculates a probability of out-migration for each at-risk man or woman, depending on their characteristics at that time. The equations include multiple variables, such as age, sex, marital status, number of children, and whether there was a violent or political event in that month. For each agent at risk of out-migration, the model also generates a random number between 0 and 1. If the agent’s calculated probability of out-migration is greater than the random number, then the agent out-migrates that month. Once it is determined that an agent will migrate, the model then assigns the agent’s destination, (Nepal/India, other Asia, Middle East, Europe/Australia/North America). The migrant’s destination affects the amount of time until they are eligible for return (ranging from one to six months) and the amount of remittances they send.

It is through these probabilistic behavioral rules, driven by regression equations, that we build in interactions between demographic behaviors over time and between individuals. For example, an agent might marry and engage in salaried employment in one monthly time step. Her new marital status will affect the probability that she out-migrates in the next time step because marital status is a variable in the out-migration regression equations. That same woman will contribute her salary to her household’s assets, which then influences the behaviors of other household members in subsequent time steps, through a variable for household assets in the regression equations of several behaviors.

Conflict scenarios

To utilize the Chitwan ABM as an experimental laboratory and test the impact of conflict on migration rates, we run three different scenarios where conflict, or a series of violent and political events over time is the “treatment.” The first scenario, No conflict, is one in which there are no violent or political events. The second scenario, Conflict, replicates the series of violent and political events that occurred in Chitwan District during the actual armed conflict. To do this, in specific months, the model includes variables for the number of bomb blasts (0–12) in each month, the number of gun battles in each month (0–4), and the occurrence (0,1) of strikes and protests, a state of emergency, and government instability in each month. These events contribute to behavioral predictions as variables in the regression equations for out-migration, return migration, marriage, and pregnancy. The third scenario we test is Extreme conflict, in which we multiply each event variable by two. In this way, a month in which there were five bomb blasts in the historical record, will show five bomb blasts in the Conflict scenario and 10 bomb blasts in the Extreme Conflict scenario. By using No Conflict as a baseline and Conflict and Extreme Conflict as alternative scenarios, we can examine potential nonlinear effects on migration. The Extreme Conflict scenario is well within the realm of possibility for an armed conflict, so it retains policy relevance.

In each ABM scenario, the conflict occurs over a period of five years, as it did in Chitwan. We allow the ABM to run for 17 years prior to enacting the conflict scenarios in order for the simulated population dynamics to stabilize. Such a “burn-in” or stabilization period is common with ABMs and gives us more confidence that the changes we see between scenarios can be attributed to the conflict, instead of the stabilization process of the model. In particular, the 17-year burn-in period that we use allows the hypothetical children who were born in the first year of the simulation to age into eligibility for many of the demographic behaviors in our model. It also allows for sufficient time so that our agents’ characteristics and statuses are largely based on the simulation, instead of partially on the simulation and partially on the presimulation survey data. In our results presented below, we show 15 years of simulation data, comprised of five years of the preconflict period, five years of the conflict, and five years after. To allow stochastic elements in the model to manifest themselves and allow for uncertainty, we run each scenario 500 times and the results we report are the mean of the 500 runs. Standard deviations of the 500 runs are not a good measure of uncertainty,2 so instead, we present gray shading to show the 25/75 percentiles, 10/90 percentiles, and 2.5/97.5 percentiles around the No Conflict scenario mean. These enable the reader to see if the mean for the conflict and extreme conflict scenarios is outside these ranges of reasonably possible no conflict scenario values.

Assessing the ABM

Before presenting results from the ABM, we validate the model by testing whether it produces demographic results that are plausible and act some-what like a real population. To do so, we compare our ABM results with demographic rates from the Nepali population and the CVFS population, where appropriate.

Figure 3 shows the population size, population growth rate, and crude birth rate (CBR) of Nepal, from 1996 to 2010, based on data from the United Nations Population Division. These are compared to the same indicators calculated from our ABM. In Figure 3a it is seen that the actual population of Nepal grew at about the same rate as our simulated ABM population of Chitwan. Figure 3b shows that annual population growth rates for the Nepali and the ABM-simulated populations both generally decreased over time. Nepal population growth rates ranged from 2.4 to 1.0 percent annually, whereas the ABM growth rates ranged from 3.1 to 0.9 percent. They both display some variation over time, with a notable dip in 2008 and subsequent increase after that. The ABM growth rates are slightly more volatile, which can be expected of a smaller area and population. Similarly, the CBR from our ABM simulation, shown in Figure 3c, is within a reasonable range of the actual Nepali CBR over time. Our ABM simulation is again more volatile, likely due to the smaller population and because the Nepali rates are available for five-year periods that can mask shorter term volatility. As with population size, the ABM growth rates and CBR are not exactly the same as for the actual population of the whole country, but they are within a reasonable range. This gives us confidence in the value of our Chitwan ABM to produce results that are consistent with standard demographic dynamics.

FIGURE 3. Comparison of population size, growth rates, and CBR s from Nepal (U.N. Population Division) and simulated Chitwan ABM values: (a) population size, (b) population growth rate, and (c) CBR.

Results

We begin with out-migration rates.3 Figure 4a shows the annual out-migration rates for men, for all three scenarios—No Conflict, Conflict, and Extreme Conflict. Recall that our primary results, with solid, dashed, and dotted lines are the average of each indicator across 500 runs of the ABM. The gray shadings quantify uncertainty, for the assessment of how likely it is that the conflict and extreme conflict results are beyond a reasonable range of the no conflict scenario. Figure 4b shows the percent difference of each of the Conflict scenarios compared to the No Conflict scenario.

FIGURE 4. Annual men’s and women’s out-migration rates, based on Chitwan ABM: (a) men’s out-migration rates, (b) percent difference in men’s out-migration rates from no conflict scenario, (c) women’s out-migration rates, and (d) percent difference in women’s out-migration rates from no conflict scenario.

As can be seen, men’s out-migration during both conflict scenarios is lower than during the No Conflict scenario. During the first year of the conflict, we see slightly lower (about 2.5 percent, as shown in Figure 4b) out-migration rates compared to the no conflict scenario, this dips to 7–8 percent lower out-migration by year eight, and a dramatic 18–27 percent lower (for the Conflict and Extreme Conflict scenarios, respectively) by year nine towards the end of the conflict. After the simulated hostilities end, in year 10, there is an increase in out-migration rates in the conflict scenarios, such that by year 11 we find higher rates of men’s out-migration compared to the No Conflict scenario. However, the decrease in men’s out-migration in the conflict scenarios is not far out of the range of the No Conflict scenario; the lowest point in out-migration in the Conflict scenario reaches the 75th percentile of the No Conflict scenario, and this extends to the 90th percentile for the Extreme Conflict scenario. Accordingly, our results indicate that on average the simulated conflict produced less out-migration and that we can feel quite confident that it produced somewhere between no migration response and a lower migration response.

As shown in Figures 4c and 4d, the pattern for women’s out-migration rates is very similar. Migration rates in the conflict scenarios are lower than in the No Conflict scenario. Throughout the conflict, the difference in out-migration rates gets larger, from about 3 percent lower out-migration in year six, to 20–25 percent lower (for Conflict and Extreme Conflict) by year 8, and 35–49 percent lower by year 9. Following cessation of the conflict, by year 15, out-migration rates return to be comparable with those in the No Conflict scenario. Both conflict scenarios produce a decrease in women’s migration that is further out of the range of the No Conflict scenario than for men.

In summary, we find a decrease in out-migration rates during the simulated conflict. Given previous research at the individual level and widespread assumptions, we might expect exactly the opposite. Thus, this surprising result requires some investigation. With knowledge of our model design and demographic dynamics, there are four prime candidates for explanation. First is that the effect could be a straightforward linear aggregation of individual out-migration likelihoods that are determined by the out-migration regression equations in the model. Second, third, and fourth are the possibility that changes in patterns of marital status, childbearing, or return migration patterns during the conflict influence subsequent out-migration likelihoods. We interrogate each of these possible explanations next.

Out-migration equations

Recall that the probability of any individual to out-migrate in our Chitwan ABM is determined by the out-migration regression equations, shown in supplementary online material Appendix A1. If the coefficients for conflict events are negative, this would create lower individual probabilities for out-migration of individuals. These lower individual probabilities could directly translate into lower aggregate out-migration rates. Indeed, if this straight-forward explanation is true, then there would be little need for the ABM and we could simply use aggregations of regression analysis to examine aggregate-level out-migration rates.

Upon close examination of the out-migration equations, some conflict events have positive and some have negative coefficients. Further, the interaction terms that involve conflict events have various positive and negative effects. Thus, a simple look at our regression equations does not answer this question. Instead, to thoroughly examine this possibility, we used only the regression equations for out-migration to calculate the predicted probability of out-migration each month for an individual man, in a scenario of conflict and a scenario of no conflict. This hypothetical man is given the mean values of all individual, household, and community characteristics. Results are shown in Figure 5, with predicted probabilities in Figure 5a and percent difference between predicted probabilities in the two scenarios in Figure 5b.

FIGURE 5. Monthly predicted probabilities of men’s out-migration, based on regression equation: (a) predicted probabilities and (b) percent difference in predicted probability from no conflict scenario.

There are certainly differences in the predicted probability of individual male out-migration between the Conflict and No Conflict scenarios, based only on the regression equation. In some cases, the differences are positive, with higher out-migration in the no conflict scenario, and in some cases the differences are negative. Looking back at the ABM-based out-migration rates, in Figure 4, the effect of conflict on migration is consistently negative. Thus, while the out-migration equation for individuals certainly influenced out-migration in the ABM, the ABM results are not a simple linear aggregation of individual out-migration probabilities.

Marital status and out-migration rates

Our second prime candidate for explaining the negative impact of conflict on out-migration rates is marital status. If the conflict influences marriage rates (which it does, results not shown here), and marital status influences the individual likelihood of out-migration (which it does, as shown in the regression equation in Online Appendix A3), then it is possible that the lower out-migration rates that we find could be a result of the relationship between conflict and marriage. To test this possibility, we created a test ABM. It is exactly the same as our main ABM, except that the coefficients for marital status and interactions with marital status in the out-migration regression equations are set to 0. Effectively, this cuts all links between marital status and out-migration likelihood, such that any changes in marital status will have no effect on out-migration.

The result from this test on men’s out-migration is shown in Figure 6. Instead of presenting the out-migration rates, we shown the percent difference between the conflict and no conflict scenarios, for the main ABM and the test ABM 1 where marital status has no effect on out-migration. The results are almost indistinguishable during the conflict period. Interestingly, we do find differences between the test and main models on men’s out-migration after the conflict ends. Recall that there is a slight increase in out-migration in the Conflict scenario after the conflict ends. This postconflict out-migration increase is not as large in the test model, indicating that the postconflict out-migration boom is likely related to changes in marital status. While that is interesting and worthy of further examination, our purpose here is to understand if conflict-related changes to marriage might explain the decreases in out-migration during the simulated conflict. This experiment tells us that is not the case.

FIGURE 6. Percent difference in men’s out-migration rates, between no conflict and conflict scenarios. Results from main ABM, test ABM 1 where marital status has no effect on migration likelihood, and test ABM 2 where children have no effect on migration likelihood.

Childbearing and out-migration rates

Our third prime candidate for explaining the negative out-migration rates during the conflict scenarios is childbearing status. The logic behind this possibility is the same as for marital status—if the conflict influences birth rates (which it does, results not shown here), and childbearing status influences the individual likelihood of out-migration (which it does, as shown in the regression equations in Online Appendix A3), then it is possible that the lower out-migration rates that we find could be a result of the relationship between conflict and childbearing. We test this possibility in the same manner as for marital status and the result is also shown in Figure 6. The curve for test ABM 2 is almost indistinguishable from the main model during the simulated conflict period. Thus, changing birth rates during the conflict are not responsible for the decreased out-migration rates during the conflict.

Return migration and out-migration rates

The fourth possible explanation for decreased out-migration rates during the conflict is return migration. If the conflict influences return migration, then that will change the composition of the population resident in Chitwan who are subsequently exposed to the risk of out-migration. In addition, the return of migrants can be important for maintenance of the social networks that heavily influence out-migration. Both mechanisms linking return with out-migration are programmed into our ABM. To examine the possibility that it is return that is responsible for the decreases in out-migration rates that we find, we first examine how the conflict influenced return migration rates.4

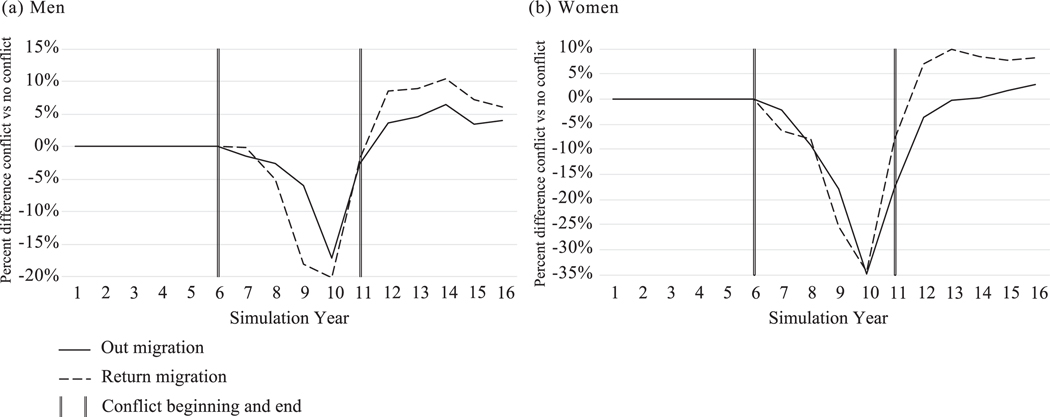

As can be seen in Figure 7, average return migration rates, for both women and men, decrease during the simulated conflicts. These decreases are stepwise, with an initial small decrease in the first two years of the conflict, larger decreases after that, and then an increase after the conflict is over. In addition, with men’s return migration, we see a small postconflict return migration increase, where the return rates are higher in the conflict scenarios compared to the No Conflict scenario. For men and women, the decreases in return rates for the conflict scenarios fall further from the reasonable range of the No Conflict scenario (in gray shading), giving us strong confidence in this result. Notably, the return rates look very similar to the out-migration rates.

FIGURE 7. Annual return migration rates, based on Chitwan ABM: (a) men’s return rates, (b) percent difference from no conflict scenario for men’s return rates, (c) women’s return rates, and (d) percent difference from no conflict scenario for women’s return rates.

When we explicitly compare the out- and return migration rates, we find this to be the case. This is shown in Figure 8, which presents the percent difference between the Conflict and No Conflict scenarios, with the solid line for out-migration and the dashed line for return migration. We show this for men in Figure 8a and for women in Figure 8b. This comparison confirms that the effect of the conflict is very similar for out and return migration. But with two differences—the pattern of change for out-migration rates appears to be about one year after that for return migration, and the return migration pattern is slightly greater in magnitude, reaching lower lows and higher highs.

FIGURE 8. Percent difference between no conflict and conflict scenarios, comparing out- and return migration rates, based on Chitwan ABM: (a) men and (b) women.

These slight differences, the one-year lag between return and out-migration rates and the higher volatility of return migration, are significant clues in our investigation of why out-migration rates decreased during the simulated conflict. Specifically, migrants are by definition those whose individual, household, or neighborhood characteristics made them more likely to migrate than those who stayed at the origin. When migrants return to the origin area, they become again eligible to, or exposed to the risk of out-migration. If return migration is high, then the origin area population will be comprised of a high number of people who are selected for out-migration. If return migration is low, then the origin area population will be increasingly comprised of those who are not selected for out-migration. This standard demographic reasoning suggests that (among other things) out-migration should follow return-migration in time.

Our results indicate that this is likely the case in our ABM. The one-year lag in our Figure 8 graphs suggests that out-migration is following return migration. The slightly less volatile out-migration effects suggest a dampening of the signal between return and out-migration, which can also be expected when other factors affect the behavior (out-migration) that is a partial consequence of another behavior (return migration).

Conceptually understanding decreased out-migration rates

To summarize the discussion above, we began with the unanticipated finding that aggregate out-migration rates, for both men and women, were lower during the simulated conflict scenarios, compared to a scenario of no conflict. In seeking to understand the reason for this surprising result, we employed a series of experiments and demographic reasoning to explore several possible causal mechanisms. We now present these in Figure 9 as a path diagram, which is a simplified derivative of our conceptual framework in Figure 1.

FIGURE 9. Path diagram of possible mechanisms linking armed conflict and out-migration rates. Stronger effects are represented with solid and dashed arrows.

While all of the individual-level behavioral mechanisms we tested have some effect on out-migration rates, return migration behavior stands out as the strongest mechanism linking armed conflict with lower out-migration rates. This is represented with a bold and solid arrow in Figure 10. Out-migration behaviors also (of course) had an important effect on out-migration rates, but likely not as strong as return migration. We represent this with a dashed and bolded arrow in Figure 10. Finally, individual-level marriage and childbearing behaviors are also related to out-migration but contribute little to influencing decreased out-migration rates.

FIGURE 10. Migrant stock, based on Chitwan ABM: (a) percent of population living out (migrant stock) each year and (b) the number of extra people living out (migrant stock) in each conflict scenario compared to the no conflict scenario.

Migrant stocks

Up to this point, we have entirely focused on migration rates or flows of people leaving and returning to the study area each year. This extensive attention is because our finding that conflict resulted in decreasing out-migration rates was surprising and required thorough explanation. While understanding how conflict influences migration rates, or flows, has substantial policy-relevance, we now address an equally or even more policy important question—how many people can we expect to be out of the study area because of an armed conflict?

The answer to the migrant stocks question cannot be assumed from our presentation thus far. While we find that out-migration rates decreased during the conflict, we also find that return migration rates also decreased. Instead, we calculate migrant stocks from our ABM and present this in Figure 10. Figure 10a shows the percent of the ABM population that is living outside the study area each year, and Figure 10b shows the number of people living outside in the two conflict scenarios compared to the No Conflict scenario.

As shown, migrant stock (or the number of persons living outside the study area) is higher in the conflict scenarios. Towards the end of the simulated conflict, in year 9, migrant stock reaches about 2.8 percent of the population in the No Conflict scenario, and 3.1 percent and 3.4 percent in the Conflict and Extreme conflict scenarios, respectively. Turning this into the number of people, as shown in Figure 10b, we find that out of this population of about 10,500 persons, the Conflict scenario produced at most an extra 45 persons living outside the district and the Extreme Conflict scenario produced an extra 88 persons in the migrant stock. Thus, even while out-migration rates decreased because of the conflict, at the same time, migrant stock increased.

Conclusion

In this study, we seek to understand how armed conflict influences macrolevel migration dynamics. By using an innovative ABM strategy, we are able to simulate population processes from the Chitwan Valley of Nepal during an armed conflict as a complex, interactive, and temporally dynamic system. In doing so, we find the surprising result that rates of out-migration decreased due to the armed conflict. While we find that out-migration rates decreased, we also show that stock of migrants outside the study area increased, but to a relatively small extent.

Our results are surprising because they are different, in fact the opposite of, common expectations and media presentations of large refugee and internally displaced movements away from armed conflict. However, our ABM method allows us to provide a sensible demographic explanation for the unforeseen phenomenon: return migration. We find that rates of return migration also decrease because of the conflict and because of the integral connection between return and out-migration, it is the changes to return migration that most likely induced the subsequent changes in out-migration. This feedback mechanism between return and out-migration is also apparent in an ABM study of migration during climate disasters in Thailand (Entwisle et al. 2020). That study, based on a different setting, data, and ABM found the similarly surprising result of decreased out-migration during extreme floods and droughts. At the same time, they found decreases in average return migration, which likely influenced the general lack of subsequent out-migration. Thus our study is the first for armed conflict, but the second in the demographic literature, showing that the integral connection between out- and return migration can create aggregate-level outcomes that are not linear aggregations of microlevel behaviors.

Examining migration as a system of closely connected out- and return migratory behaviors helps to explain our surprising results for out-migration rates, but it also better matches the livelihood system in our study area, Chitwan Nepal, and allows us to consider other possible consequences of armed conflict. Specifically, in the preconflict period, the migration regime in Chitwan (and the rest of Nepal) can be characterized as temporary and highly mobile; many people left, most of them returned within relatively short periods of time, and many of the returnees subsequently left again. Of note is that livelihood strategies were centered around and dependent on this system of out- and return migration. During the conflict, our finding that both out- and return migration decreased dramatically can be taken to mean that the conflict disrupted the preexisting migration system—temporary in nature with high rates of back and forth churning— and created a new migration one—longer term in nature, with lower rates of churning. Because the preconflict migration system was closely tied to livelihood strategies, one of the implications of our results is that we must now question how the conflict-affected migration system in turn influenced livelihood strategies in the Chitwan area, with implications for remittance flows and household labor. Another implication of our results is to question how the conflict-affected migration system influenced migrants themselves who spent longer periods of stay outside the study area and how those longer periods of stay might affect the likelihood of their return and postreturn integration into households and communities in the postconflict period.

Our Chitwan ABM is a case study of one setting, and our results necessarily apply to just that setting. This study should not be taken to imply that similar dynamics will occur in other places, especially our finding that aggregate out-migration rates decreased during the armed conflict. Generalizability of this dynamic can only be confirmed with studies in other settings. However, we can consider the pivotal characteristics of the Nepal setting that drive our results and surmise that we might find similar results in settings with similar pivotal characteristics. First, the conflict in Nepal was of moderate intensity. Second, the preconflict migration system was one of high rates of temporary migration. This suggests that the conclusions in this study might have some relevance for other areas of the world that can be characterized in the same way. Notably, many countries in the world, particularly those that are poorer and have large agricultural sectors experience high rates of temporary migration and migration-dependent livelihoods. Also notable is that while intensely violent conflicts feature prominently in the news media and public awareness, the most common type of armed conflict today is actually of moderate intensity (Pettersson and Eck 2018). Thus, there are many areas of the world that are comparable to Chitwan on these two factors, in which we might expect to find similar migration dynamics during armed conflict. Of course, future research is required to verify that possibility. In addition, studies of other areas, with more intense violence and different migration systems, will be an interesting contribution to understanding how conflict might have a range of influences on migration dynamics.

The findings in this study also have relevance beyond just situations of armed conflict. Our conceptual model, in Figure 1, can relate to any kind of macrolevel change, such as climate and environmental change, natural hazards, political change, all of which occur with unfortunate frequency in countries rich and poor. For any of these macrochanges that affect how people behave at the microlevel, our conceptual model is useful for planning a study of the aggregate demographic results and the ABM strategy is useful for implementing such a study. In the case of migration, this conceptual and modeling strategy enables the analyst to address the migration system that is comprised of interconnections between return and out-migration and the driving force behind the surprising results in this study and Entwisle et al. (2020). In the case of other demographic outcomes of interest, our strategy enables similar system-level analyses, such as accounting for the dynamic interconnections between marriage, fertility rates, and population growth. The demographic literature is already strong in assessing the factors that influence the likelihood of microlevel behavioral changes. We aim now to use those insights, a complex systems conceptual perspective, and ABM techniques to advance scholarship of the aggregate population changes and rates that are essential for informed policymaking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by generous grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development including a research grant (HD067587) and a research infrastructure grant (R24HD042828) to the University of Washington Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology. We thank Barbara Entwisle, William Axinn, and Dirgha Ghimire for their assistance, the Institute for Social and Environmental Research- Nepal for collecting the survey and violent event record data, Meeta Sainju-Pradhan for collecting the political event data, the South Asia Terrorism Portal, and Informal Service Sector for collecting records of violent events, and the Chitwan Valley Family Study respondents for sharing their lives and experiences. All errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Calculated with data from Uppsala Conflict Data Program (https://ucdp.uu.se/) and United Nations Population Division World Population Prospects data (https://population.un.org/wpp/).

Just as we can calculate a mean, it would also be possible to calculate a measure of uncertainty, based on standard deviations or percentiles, from the 500 simulation runs. However, such measures rely on sample size, which in our case is 500 runs. Because we can manipulate sample size, by running the model 1,000, 2000, or more times, that means our uncertainty measures are also manipulable and therefore not meaningful.

Annual out-migration rates are calculated by using the number of age eligible people who migrated out of Chitwan during the year, dividing that by the number of people resident in Chitwan at the beginning of the year, and multiplying that by 100. Agents must be 16 years or older to migrate on their own (without their parents). All our migration results are calculated only for the 16 years and older population.

We calculate return migration rates by dividing the number of return migrations during a year by the number of people who were out of the Chitwan District (migrants) at any time that same year. Although there is not a standard practice for calculating return migration rates, because it is rarely done, standard demographic procedures for calculating other rates often use a population count at the beginning or middle of the year. In this case, we do not use the population of migrants at the beginning or mid-year because our model follows migration on a monthly basis and allows for people to migrate and return within the same year. Thus, the population exposed to the risk of return migration is those who are non-resident at the beginning of the year and those who moved out during that same year and could still return that year.

Contributor Information

NATHALIE E. WILLIAMS, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

MICHELLE L. O’BRIEN, New York University–Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, UAE.

XIAOZHENG YAO, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA..

References

- Agadjanian Victor, and Prata Ndola. 2001. “War and Reproduction: Angola’s Fertility in Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Southern African Studies 27(2): 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian Victor, and Prata Ndola. 2002. “War, Peace, and Fertility in Angola.” Demography 39(2): 215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Li, Linderman Marc, Qi Jiaguo, Shortridge Ashton, and Liu Jianguo. 2005. “Exploring Complexity in a Human–Environment System: An Agent-Based Spatial Model for Multidisciplinary and Multiscale Integration.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95(1): 54–79. [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca Clair. 1998. “Human Rights Abuses: Precursor to Refugee Flight?” Journal of Refugee Studies 11(1): 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss Amy H., and Roux Ana V. Diez. 2008. “A New Tool for Epidemiology: The Usefulness of Dynamic-Agent Models in Understanding Place Effects on Health.” American Journal of Epidemiology 168(1): 1–8. 10.1093/aje/kwn118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Barber Jennifer S., and Ghimire Dirgha J.. 1997. “The Neighborhood History Calendar: A Data Collection Method Designed for Dynamic Multilevel Modeling.” In Sociological Methodology edited by Raftery Adrian E., 355–392 Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Ghimire Dirgha J., Williams Nathalie E., and Scott Kate M.. 2013. “Gender, Traumatic Events, and Mental Health Disorders in a Rural Asian Setting.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 54(4): 444–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Pearce Lisa D., and Ghimire Dirgha. 1999. “Innovations in Life History Calendar Applications.” Social Science Research 28(3): 243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Axtell Robert L., Epstein Joshua M., Dean Jeffrey S., Gumerman George J., Swedlund Alan C., Harburger Jason, Chakravarty Shubha, Hammond Ross, Parker Jon, and Parker Miles. 2002. “Population Growth and Collapse in a Multiagent Model of the Kayenta Anasazi in Long House Valley.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99(3): 7275–7279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azose Jonathan J., and Raftery Adrian E.. 2019. “Estimation of Emigration, Return Migration, and Transit Migration between All Pairs of Countries.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(1): 116–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azose Jonathan J., Ševčíková Hana, and Raftery Adrian E.. 2016. “Probabilistic Population Projections with Migration Uncertainty.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(23): 6460–6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S., Shivakoti Ganesh P., Axinn William G., and Gajurel Kishor. 1997. “Sampling Strategies for Rural Settings: A Detailed Example from Chitwan Valley Family Study, Nepal.” Nepal Population Journal 6(5): 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm Deborah A. 2011. “US-Mexico Mixed Migration in an Age of Deportation: An Inquiry into the Transnational Circulation of Violence.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 30(1): 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch Elizabeth E., and Mare Robert D.. 2006. “Neighborhood Choice and Neighborhood Change.” American Journal of Sociology 112(3): 667–709. 10.1086/507856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bundervoet Tom, and Verwimp Philip. 2005. “Civil war and economic sanctions: Analysis of anthropometric outcomes in Burundi”. Households in Conflict Working Paper No. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Campos Christian Vanhille, Suleimenova Diana, and Groen Derek. 2019. “A Coupled Food Security and Refugee Movement Model for the South Sudan Conflict.” In Computational Science – ICCS 2019, edited by Rodrigues J, et al. , 725–732. International Conference on Computational Science Faro, Portugal. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 11540. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Lance. 1989. Early Warning of Refugee Flows. Refugee Policy Group; (Washington D.C.). [Google Scholar]

- Collier Paul. 1999. “On the Economic Consequences of Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 51(1): 168–183. [Google Scholar]

- Crush Jonathan, Chikanda Abel, and Tawodzera Godfrey. 2015. “The Third Wave: Mixed Migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa.” Canadian Journal of African Studies /Revue canadienne des études africaines 49(2): 363–382. [Google Scholar]

- Czaika Mathias, and Kis-Katos Krisztina. 2009. “Civil Conflict and Displacement: Village-Level Determinants of Forced Migration in Aceh.” Journal of Peace Research 46(3): 399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport Christina, Moore Will, and Poe Steven. 2003. “Sometimes You Just Have to Leave: Domestic Threats and Forced Migration, 1964–1989.” International Interactions 29(1): 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Kingsley. 1963. “The Theory of Change and Response in Modern Demographic History.” Population Index 29(4): 345–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards Scott. 2008. “Computational Tools in Predicting and Assessing Forced Migration.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21(3): 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Barbara, Malanson George, Rindfuss Ronald R., and Walsh Stephen J.. 2008. “An Agent-Based Model of Household Dynamics and Land Use Change.” Journal of Land Use Science 3(1): 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Barbara, Verdery Ashton, and Williams Nathalie. 2020. “Climate Change and Migration: New Insights from a Dynamic Model of Out-Migration and Return Migration.” American Journal of Sociology 125(6): 1469–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Barbara, Williams Nathalie E., Verdery Ashton M., Rindfuss Ronald R., Walsh Stephen J., Malanson George P., Mucha Peter J., Frizzelle Brian G., McDaniel Philip M., Yao Xiaozheng, Heumann Benjamin W., Prasartkul Pramote, Sawangdee Yothin, and Jampaklay Aree. 2016. “Climate Shocks and Migration: An Agent-Based Modeling Approach.” Population and Environment 38(1): 47–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein Joshua M. 1999. “Agent-Based Computational Models and Generative Social Science.” Complexity 4(5): 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald David Scott, and Arar Rawan. 2018. “The Sociology of Refugee Migration.” Annual Review of Sociology 44(1): 387–406. [Google Scholar]

- Gebre Yntiso D. 2002. “Contextual Determination of Migration Behaviours: The Ethiopian Resettlement in Light of Conceptual Constructs.” Journal of Refugee Studies 15(3): 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm Volker, Berger Uta, Bastiansen Finn, Eliassen Sigrunn, Ginot Vincent, Giske Jarl, Goss-Custard John, Grand Tamara, Heinz Simone K., Huse Geir, Huth Andreas, Jepsen Jane U., Jørgensen Christian, Mooij Wolf M., Müller Birgit, Pe’er Guy, Piou Cyril, Railsback Steven F., Robbins Andrew M., Robbins Martha M., Rossmanith Eva, Rüger Nadja, Strand Espen, Souissi Sami, Vabø Rune, Visser Ute. 2006. “A Standard Protocol for Describing Individual-Based and Agent-Based Models.” Ecological Modelling. 198(1–2): 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm Volker, Berger Uta, DeAngelis Donald L., Polhill J. Gary, Giske Jarl, Railsback Steven S.. 2010. “The ODD Protocol: A Review and First Update.” Ecological Modelling. 221(23): 2760–2768. [Google Scholar]

- Groen Derek. 2016. “Simulating Refugee Movements: Where Would You Go?” Procedia Computer Science 80: 2251–2255. [Google Scholar]

- Grow André, and Van Bavel Jan. 2015. “Assortative Mating and the Reversal of Gender Inequality in Education in Europe: An Agent-Based Model.” PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow André, and Van Bavel Jan, eds. 2017. Agent-Based Modelling in Population Studies: Concepts, Methods, and Applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline Patrick. 2015. “The Boundaries of Genocide: Quantifying the Uncertainty of the Death Toll During the Pol Pot Regime in Cambodia (1975–79).” Population Studies 69(2): 201–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline Patrick, and Poch Bunnak. 2007. “The Phoenix Population: Demographic Crisis and Rebound in Cambodia.” Demography 44(2): 405–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Security Report Project. 2014. Human Security Report 2013: The Decline in Global Violence: Evidence, Explanation and Contestation. Vancouver: Human Security Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutt Michael J. 2004. “Monarchy, Democracy and Maoism in Nepal.” In Himalayan People’s War: Nepal’s Maoist Revolution, edited by Hutt Michael J., 1–20. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman Anuja, Gebreselassie Tesfayi, and Chandrasekhar S. 2008. “Effect of Conflict on Age at Marriage and Age at First Birth in Rwanda.” Population Research and Policy Review 28(5): 551. [Google Scholar]

- Justino Patricia. 2006. “On the Links between Violent Conflict and Chronic Poverty: How Much Do We Really Know?” CPRC Working Paper 61. [Google Scholar]

- Lester David. 1993. “The Effect of War on Marriage, Divorce and Birth Rates.” Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 19(1–2): 229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley Anna. 2010. “Leaving Mogadishu: Towards a Sociology of Conflict-Related Mobility.” Journal of Refugee Studies 23(1): 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom David P., and Berhanu Betemariam. 1999a. “The Impact of War, Famine, and Economic Decline on Marital Fertility in Ethiopia.” Demography 36(2): 247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom David P., and Berhanu Betemariam. 1999b. “The Impact of War, Famine, and Economic Decline on Marital Fertility in Ethiopia.” Demography 36(2): 247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack Andrew. 2005. Human Security Report 2005: War and Peace in the 21st Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macy Michael W. 2015. “Social Simulation: Computational Models.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, edited by Wright James D., 701–705. Oxford: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Macy Michael W., and Willer Robert. 2002. “From Factors to Actors: Computational Sociology and Agent-Based Modeling.” Annual Review of Sociology 28: 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., and Espinosa Kristin E.. 1997. “What’s Driving Mexico-U.S. Migration? A Theoretical, Empirical, and Policy Analysis.” American Journal of Sociology 102(4): 939–999. [Google Scholar]

- Melander Erik, and Öberg Magnus. 2006. “Time to Go? Duration Dependence in Forced Migration.” International Interactions 32(2): 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Will H., and Shellman Stephen M.. 2004. “Fear of Persecution: Forced Migration, 1952—1995.” Journal of Confiict Resolution 48(5): 723–745. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Dawn C., Manson Steven M., Janssen Marco A., Hoffmann Matthew J., and Deadman Peter. 2003. “Multi-Agent Systems for the Simulation of Land-Use and Land-Cover Change: A Review.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 93(2): 314–337. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson Therése, and Eck Kristine. 2018. “Organized Violence, 1989–2017.” Journal of Peace Research 55(4): 535–547. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson Therése, Högbladh Stina, and Öberg Magnus. 2019. “Organized Violence, 1989–2018 and Peace Agreements.” Journal of Peace Research 56(4): 589–603. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew Judith. 2003. “Guns, Kingship, and Fear: Maoists among the Tamu-Mai (Gurungs).” In Resistance and the State: Nepalese Experiences edited by Gellner David, 305–325. New York: Berghagn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew Judith. 2004. “Living between the Maoists and the Army in Rural Nepal.” In Himalayan People’s War: Nepal’s Maoist Revolution edited by Hutt Michael J., 261–284 Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew Judith, and Adhikari Kamal. 2009. “Fear and Everyday Life in Rural Nepal.” Dialectical Anthropology 33: 403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena Prem C., Kulczycki Andrzej, and Jurdi Rozzet. 2004. “Nuptiality Transition and Marriage Squeeze in Lebanon: Consequences of Sixteen Years of Civil War.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 35(2): 241–258. 10.3138/jcfs.35.2.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeidl Susanne. 1997. “Exploring the Causes of Forced Migration: A Pooled Time-Series Analysis, 1971–1990.” Social Science Quarterly 78(2): 284–308. [Google Scholar]

- Shemyakina Olga. 2009. “The Marriage Market and Tajik Armed Conflict.” Households in Conflict Network Working Paper 66. [Google Scholar]

- Shemyakina Olga. 2011. “The Effect of Armed Conflict on Accumulation of Schooling: Results from Tajikistan.” Journal of Development Economics 95(2): 186–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski John A. , Banks Catherine M., and Hayes Reginald L.. 2014. “Modeling Population Displacement in the Syrian City of Aleppo.” In Proceedings of the Winter Simulation Conference 2014, December 7–10 [Google Scholar]

- Stanley William Deane. 1987. “Economic Migrants or Refugees from Violence? A Time-Series Analysis of Salvadoran Migration to the United States.” Latin American Research Review 22(1): 132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Suleimenova Diana, Bell David, and Groen Derek. 2017. “A Generalized Simulation Development Approach for Predicting Refugee Destinations.” Scientific Reports 7(1): 13377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hear Nicholas. 2009. “Managing mobility for human development: The growing salience of mixed migration.” United Nations Development Programme. Accessed October 31, 2014. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/managing-mobility-human-development [Google Scholar]

- VanWey Leah K. 2005. “Land Ownership as a Determinant of International and Internal Migration in Mexico and Internal Migration in Thailand.” International Migration Review 39(1): 141–172. [Google Scholar]

- Verpoorten Marijke. 2005. Self-insurance in Rwandan households: The use of livestock as a buffer stock in times of violent conflict. In CESifo Conference, Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Vullnetari Julie. 2012. “Beyond ‘Choice or Force’: Roma Mobility in Albania and the Mixed Migration Paradigm.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38(8): 1305–1321. [Google Scholar]