ABSTRACT

Lip adhesion (LA), performed in the treatment of wide cleft lip, is a technique used to relieve tension on the reconstructed lip and improve the outcome of definitive cleft lip repair; however, there are some limitations that need to be addressed, such as the formation of new scarring on the lip and postoperative wound dehiscence, with prominent protrusion of the premaxilla in bilateral cases. A 3‐month‐old boy underwent preoperative correction for complete bilateral cleft lip with prominent premaxillary protrusion, in which we pulled and attached the lateral lip to the premaxilla and then the contralateral lip to each other with barbed sutures. Definitive cleft repair was performed 1.5 months after the preoperative correction. Adequate preoperative retraction of the protruding premaxilla and reduced suture tension allowed for a definitive cleft lip repair, which resulted in a good lip shape. Preoperative lip and premaxilla correction with barbed sutures is a minimally invasive, simple procedure that can be performed in a short time, and is believed to provide stronger fixation than current methods because of its multi‐point fixation with multiple barbs. It also leaves the lip with almost no scarring, which may be advantageous for the definitive repair procedure. Continued follow‐up of the patient's lips after development and alveolar cleft surgery is warranted, as is the accumulation of additional cases using the same technique.

Keywords: barbed sutures, complete bilateral cleft lip, lip adhesion, preoperative correction

Preoperative lip and premaxilla correction using barbed sutures effectively reduces premaxillary protrusion and suture tension, improving outcomes in definitive lip repair.

Summary.

Preoperative lip and premaxilla correction using barbed sutures effectively reduces premaxillary protrusion and suture tension, improving outcomes in definitive lip repair.

This minimally invasive, quick technique provides strong multipoint fixation with minimal scarring, which may improve esthetic outcomes.

Long‐term follow‐up and further case studies are needed to validate this method.

1. Introduction

In cases of complete bilateral cleft lip, lip adhesion (LA) may be performed prior to definitive lip repair as an alternative to conservative treatments such as taping in patients with a wide cleft and/or prominent protrusion of the premaxilla. LA reduces cleft width and lip tension while providing adequate premaxillary retraction to improve lip morphology after definitive repair. However, scarring from the LA may interfere with the definitive lip repair when flaps are placed on the premaxilla and lateral lips. Postoperative wound dehiscence is common in patients with high wound tension. Furthermore, patients may develop additional scarring from the LA procedure and definitive cleft lip closure, which may negatively affect the growth of the maxillary alveolar arch [1, 2, 3].

We present herein a case in which preoperative lip and premaxilla correction was achieved by pulling the lateral lips and attaching the lip margins with barbed sutures (STRATAFIX Symmetric PDS Plus Knotless Tissue Control Device 3–0; Ethicon) with good results, as well as a review of the relevant literature.

2. Case History

The patient was a 3‐month‐old boy with a wide, complete bilateral cleft lip and alveolar arch, as well as a prominent forward protrusion of the premaxilla. He continued to wear the lip tape at home with little improvement (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preoperative findings: The patient had a prominent anterior protrusion of the premaxilla.

3. Treatment

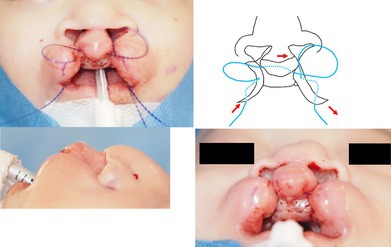

Since we expected that it would be difficult to achieve good results with a single procedure, we performed a lip and premaxilla correction with barbed sutures before definitive cleft lip closure. In this corrective procedure, we threaded the suture from the oral mucosa side to the lateral lip, through the premaxilla, to the contralateral lip, and cut the suture with enough traction to ensure that the lateral lips and premaxilla were attached on the left and right sides (Figure 2a). This technique applies a posterior tractive force to the premaxilla (Figure 2b,c), allowing the protrusion to be reduced postoperatively by pulling the left and right lateral lips posteriorly.

FIGURE 2.

Lip and premaxilla correction. (a) Two barbed sutures were threaded from the oral mucosa side to the lateral lip, through the premaxilla, and to the contralateral lip. Since the sutures are pulled, cut, and implanted submucosally, they do not need knots. (b, c) Immediately after the operation, the premaxilla was pulled back by the lips.

4. Conclusion and Results

The premaxilla was sufficiently retracted to allow the lips to move into a good position and relieve the tension associated with the sutures. One barbed suture was spontaneously removed after about 1 month of preoperative correction, and the other one was removed at the time of definitive repair. After the inflammation of the tissue caused by preoperative correction has subsided, we performed the bilateral cleft lip repair 1.5 months later using the DeHaan method, which is easier to perform without high tension. Good lip morphology and almost no scarring were observed (Figure 3a–e).

FIGURE 3.

Findings at the time of the definitive repair. (a, b) Preoperatively, the premaxilla was well retracted. (c, d) Postoperatively, good lip morphology was obtained. (e) 3.5 months after the definitive repair—good morphology was maintained.

Our technique of using barbed sutures for the preoperative lip and premaxilla correction improved the prominent anterior premaxillary protrusion, reduced the width of the cleft, and easily relieved the tension on the lip without complications such as scarring or wound dehiscence. This technique is simple, easy to use, and has provided excellent results at the time of the final cleft closure. We hope to accumulate more cases in the future to validate the outcomes of this case.

5. Discussion

In cases of complete bilateral cleft lip with a wide gap, it may be difficult to close the cleft in a single procedure, especially when in conjunction with the prominent protrusion of the premaxilla. Nonoperative methods using dedicated devices and taping have been reported to reduce cleft width [4, 5]; however, frequent visits to hospital clinics are needed with these methods, and they may involve complications such as epidermal peeling with tape, the development of dermatitis, and insufficient reduction in the gap in cases of a wide cleft or significant premaxillary protrusion [2]. In cases where conservative treatment has not been successful, osteotomy or LA has been attempted to reduce the cleft width prior to the cleft repair [6, 7].

Franco first described the resection of the protruding premaxilla in bilateral cleft lip in 1556, and in 1833 Gensoul performed surgical recessions of the premaxilla using the compression‐fracture technique. In the late 18th century, Cronin emphasized the importance of avoiding damage to the suture between the vomer and premaxilla (where forward growth of the premaxilla is thought to occur) and to the nasal septal cartilage. The possibility of postosteotomy midfacial developmental defects is still debated [8, 9, 10].

The possibility of growth disturbances in the maxillary alveolar arch, which has been pointed out in previous osteotomies, is unknown; however, it is expected to be less likely with this method, which causes less damage to the tissue than previous methods. Therefore, long‐term monitoring of the patient's growth and development is needed.

In 1965, Randall presented the LA as a partial closure of the complete cleft using tissue removed from the cleft during a normal lip repair. The definitive repair, performed several months later, is much easier after the preoperative correction, allowing a more normal lip and external nose to be achieved. Since its introduction, various LA techniques have been developed. The cleft lip margin is typically resected and combined on the dorsal side of the prolabium, for which a triangular or short wide‐base rectangular mucocutaneous flap is recommended. The C‐W technique involves designing a flap from the vermilion, while Millard and Latham proposed a technique that combines LA with periosteoplasty through an incision along the cleft margin [8, 9]. Taofeek reported the width of cleft above 14 mm statistically correlates significantly with the occurrence of early surgical site complications including wound dehiscence in primary repair without LA [11]. Nagy et al. reported the beneficial effects of LA in combination with a guidance plate outweighed the risks for anatomical reconstruction of a platform for definitive lip and nose repair [8]. On the other hand, one disadvantage of LA is wound dehiscence, which has reported rates as high as 24% in bilateral cases and 8% in unilateral cases, requiring reoperation [2]. Additionally, LA may result in scar formation, which destroys valuable tissues needed for definitive repair [2, 9].

In this case of a wide bilateral complete cleft lip and alveolar arch with prominent anterior protrusion of the premaxilla, we used barbed sutures to pull the lateral lips towards the midline and attached the lip margins instead of performing LA. The method used in this study results in no scarring on the lip because only the entry and exit sites of the sutures are incised in the oral mucosa for suture implantation. This may, therefore, have had a minimal impact on definitive lip repair.

Barbed sutures are widely used in various surgical fields because of their simplicity [12, 13, 14]. In the field of cosmetic surgery, barbed sutures are used in various minimally invasive percutaneous rejuvenation procedures such as lifting droopy tissue in the brow, midface, and neck, as well as in cosmetic breast surgeries such as breast augmentation, reduction, and lifting [13, 14]. Outside of cosmetic surgery, the use of the same barbed sutures as those used in this study has been reported on the scalp, resulting in strong closure of wounds with minimal scalp alopecia [15]. One important characteristic of standard sutures is the need to knot them to ensure their integrity. Additionally, excessive tension in individual sutures may result in localized ischemia. Pressure‐induced ischemia and necrosis are the main factors that render wounds susceptible to infection, leading to wound dehiscence [13]. These problems can be solved by using barbed sutures, which allow for the creation of multipoint anchors without the need for knots. It has been reported that continuous barbed dermal sutures result in significantly shorter closure times with blood flow obstruction similar to that of interrupted monofilament sutures [16].

In a normal LA suture, the force required to fix the lip is applied only at its edge; however, by pulling a wider area of tissue through the barbed suture, a stronger tractive force and fixation of the entire lip tissue can be achieved. When using a barbed suture, each barb becomes a fixation point, allowing the tissue to be fixed at multiple points. Therefore, the tension is more evenly distributed, and a higher tensile strength can be achieved while minimizing tissue damage [16]. Additionally, this technique does not require a large incision in the tissue and is completed by threading the sutures through the lips. The advantages of this technique are that it is easy to perform and can be completed in a short time.

Improving the prominent protrusion of the premaxilla with sufficient force from the prolabial lip allowed the lip to be formed without tension on its medial and lateral aspects during the definitive repair surgery. The lack of additional scar formation at the time of the barbed suturing procedure resulted in good lip morphology after the definitive repair. To the best of our knowledge, a similar approach using barbed sutures for cleft lip has not been reported to date.

Author Contributions

Yuzuka Oda: writing – original draft. Kazuki Shimada: writing – review and editing. Yukiko Ida: writing – review and editing. Takako Komiya: writing – review and editing. Miki Fujii: writing – review and editing. Hajime Matsumura: supervision, writing – review and editing.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient and his parents mentioned in this study. We also thank medical staff for their valuable help.

Oda Y., Shimada K., Ida Y., Komiya T., Fujii M., and Matsumura H., “Preoperative Correction Using Barbed Sutures as an Alternative to Lip Adhesion for Complete Bilateral Cleft Lip With Prominent Protrusion of the Premaxilla: A Case Report,” Clinical Case Reports 13, no. 8 (2025): e70694, 10.1002/ccr3.70694.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. These data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions, as they contain information that could compromise the confidentiality of research participants.

References

- 1. Sasaguri M., Hak M. S., Nakamura N., et al., “A Study of Effects of Hotz's Plate and Lip Adhesion in Patients With Complete Unilateral Cleft Lip and Plate: Follow‐Up Observation Until 5 Years of Age,” Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and Pathology 26 (2014): 292–300, 10.1016/j.ajoms.2013.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang J. F., Smetona J., Lopez J., Peck C., Pourtaheri N., and Steinbacher D. M., “Does Initial Cleft Lip Width Predict Final Aesthetic Outcome?,” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open 9 (2021): e3966, 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takahashi S., Ujiie H., Shigematsu T., Tachikawa J., Tanabe H., and Fuma Y., “About Lip Adhesion for Complete Cleft Lip,” Journal of the Japan Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 16 (1970): 396–400, 10.5794/jjoms.16.396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. R. Millard, Jr. , Cleft Craft: The Evolution of Its Surgery—Volume II: Bilateral and Rare Deformities (Little Brown and Company, 1977). [Google Scholar]

- 5. M. L. Griswold, Jr. and Sage W. F., “Extraoral Traction in the Cleft Lip,” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 37 (1966): 416–421, 10.1097/00006534-196605000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seibert R. W., “Lip Adhesion,” Facial Plastic Surgery 9 (1993): 188–194, 10.1055/s-2008-1064612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seibert R. W., “Lip Adhesion in Bilateral Cleft Lip,” Archives of Otolaryngology 109 (1983): 434–436, 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800210010002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagy K. and Mommaerts M. Y., “Lip Adhesion Revisited: A Technical Note With Review of Literature,” Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery 42 (2009): 204–412, 10.4103/0970-0358.59283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farhadi R. and Wallace R. D., “Primary Premaxillary Ostectomy and Setback: Dealing With the “Fly‐Away” Premaxilla,” Annals of Plastic Surgery 90 (2023): 325–330, 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vargervik K., “Growth Characteristics of the Premaxilla and Orthodontic Treatment Principles in Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate,” Cleft Palate Journal 20 (1983): 289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amoo Abiodun T., Olutayo J., Adeyemi M., Taiwo Abdurrazaq O., and Adeyemo Wasiu L., “Does the Initial Width of Cleft Lip Play a Role in the Occurrence of Immediate Local Complications Following Primary Cleft Lip Repairs?,” Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 32, no. 2 (2021): 670–674, 10.1097/scs.0000000000007179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sakuma T., Teraoka H., Shoji T., Kinoshita H., Nakagawa Y., and Ohira M., “A Case of Postoperative Small Intestinal Obstruction due to Absorbable Barbed Suture Used in Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair,” Japanese Journal of Gastroenterological Surgery 55 (2022): 718–724, 10.5833/jjgs.2021.0154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paul M. D., “Bidirectional Barbed Sutures for Wound Closure: Evolution and Applications,” Journal of the American College of Certified Wound Specialists 1, no. 2 (2009): 51–57, 10.1016/j.jcws.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitchell R. T. and Bengtson B. P., “Clinical Applications of Barbed Suture in Aesthetic Breast Surgery,” Clinical Plastic Surgery 42 (2015): 595–604, 10.1016/j.cps.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hosomi K., Yuzuriha S., Nagai F., and Yanagisawa D., “Additional Relaxing Suturing Using Absorbable Symmetric Barbed Sutures to Help Close Scalp Defects,” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open 20 (2020): e2658, 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsumura H., Shimada K., Ito N., et al., “Evaluation of Incision‐Site Blood Flow Using Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging: Set‐Back Continuous Suturing With Barbed Sutures vs. Set‐Back Continuous or Interrupted Suturing With Monofilament Sutures,” International Journal of Surgical Wound Care 4 (2023): 45–50, 10.36748/ijswc.4.2_45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. These data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions, as they contain information that could compromise the confidentiality of research participants.