Abstract

Emojis are widely used in digital communication. A key function of these symbols is to convey affective meaning. In order to study emojis scientifically, it is necessary to have normative data characterising them on a number of relevant variables. So far, however, resources in this area are scarce. This article presents subjective norms for 112 emojis in 13 affective dimensions that refer to discrete emotions: anger, disgust, fear, sadness, anxiety, happiness, awe, contentment, amusement, excitement, serenity, relief, and pleasure. This data was collected from 763 Spanish speakers and validated using standard methods applied to existing affective datasets of emojis and words. This is the first normative emoji study to provide data on a large number of positive emotions. Given that most emojis are used to communicate positive emotions, these norms will be of particular value to researchers interested in these graphic icons from a variety of academic fields. The dataset has been made freely available.

Subject terms: Human behaviour, Interdisciplinary studies

Background & Summary

Emojis are graphical icons that represent a wide range of concepts, including facial expressions, objects, living beings, gestures, activities, and symbols (see1, for a review). They were first introduced in Japan in late 1990s and became popular in 2010 after being standardized in the Unicode version 6.0, and supported by Apple on the iPhone2. The original emoji set contained 722 characters. This number has been steadily increasing since then, with 3,790 emojis in the latest Unicode version, released in September 2024 (Full Emoji List, v16.0; https://unicode.org/emoji/charts/full-emoji-list.html).

The massive use of emojis in computer-mediated communication (CMC) has greatly stimulated the scientific interest in these graphic icons, which have become a hot topic of research in academic fields as diverse as computer science, communication, marketing, linguistics, and psychology, among others (see1 and3 for reviews).

Much research in the field of communication has focused on the factors that influence emoji use in CMC, identifying age, gender, psychological traits, mood and culture as relevant variables. Indeed, older users are less likely to use emojis and use fewer emojis compared to younger users4. Women have a more positive attitude towards emojis and use them more frequently than men5,6. Furthermore, extroversion7 and good mood8 are positively associated with the use of emojis. There are also cultural differences, with people from certain cultures tending to use emojis more frequently than others9.

Research in semiotics has aimed to identify the semantic, pragmatic and phatic functions of emojis within texts10. Within this framework, recent theoretical developments have sought to establish the rules that govern the joint construction of meaning by emojis and language11.

Emojis are an important communicative resource used to overcome a clear limitation of CMC compared to face-to-face interactions: The lack of non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions, body language, and prosody. In this sense, emojis have a clear semantic function. Indeed, there is evidence indicating that emojis are semantically integrated with the accompanying text, as the congruence between emojis and the verbal message leads to a facilitated processing12–15. Furthermore, emojis act as semantic cues that help to clarify the meaning of the written message. For example, when communication includes emojis people are better at recognising the conveyed indirect meaning of sentences16, and at disambiguating ambiguous messages17. People also show a greater agreement in their ratings of the affective tone of messages when they include emojis2.

Another key communicative function of emojis is to convey affective meaning (e.g.18–20). In this regard, emojis facilitate the communication of subtle emotional cues, such as sarcasm21, and are used to both intensify and reduce the intensity of messages with an emotional content22. Moreover, these graphic symbols influence the mood of the receiver, with advertisements containing emojis producing a more positive affect in consumers than those that do not contain them23. This also has social consequences, such that emojis contribute to maintain emotional closeness in CMC24.

The emotional function of emojis has prompted researchers to characterise their affective content, leading to the development of emotional lexicons. These resources describe emojis in terms of their positivity or negativity or in terms of their association with specific emotions (e.g., fear or happiness). In one of the first studies in this line, Novak et al.2 created the Emoji Sentiment Ranking, in which 751 emojis were classified into positive, negative and neutral. This distribution was obtained by asking a small number of human annotators to label the affective polarity of the tweets in which the emojis appeared. Due to the subjectivity and time-consuming nature of human annotation, other studies have adopted automated methods. For example, Fernández-Gavilanes et al.25 used the official definitions in Emojipedia (an online encyclopaedia of emojis) to create an emoji lexicon, while Kimura and Katsurai26 relied on emotional vectors to automatically assign emotional labels to emojis. These vectors were based on the frequency of co-occurrence between emojis and emotional words (i.e., words that refer to emotions).

As useful as they are, a limitation of these approaches is that they do not consider users’ perceptions27. This is a relevant issue, given the existing differences between emoji developers’ intended meanings and users’ interpretations27; the ambiguity of emoji interpretations, both between people and across platforms28; and the fact that many existing emojis may have more than one interpretation29.

As an alternative, several normative studies have been developed. In these, many users rate the affective properties of large sets of stimuli. This research has mostly adopted a dimensional approach to emotions, which describes emotional states in terms of a few affective dimensions, the most relevant of which are valence (i.e., the hedonic tone of an experience, ranging from highly unpleasant to highly pleasant) and arousal (i.e., the degree of activation elicited by the experience, ranging from highly calming to highly exciting30,31). Within this framework, these two dimensions can be used to describe the affective properties of any stimulus, such as pictures (e.g.32,33) and words (e.g.34,35). This approach has been applied to emojis recently, although only a few normative datasets are available so far. The most comprehensive studies in this regard are those of Ferré et al.36, who developed Emoji-SP with Spanish users; Rodrigues et al.27, who created the Lisbon Emoji and Emoticon Database (LEED) with Portuguese users; and Scheffler and Nenchev37, who obtained affective ratings from German speakers. All of them collected valence and arousal ratings for a large set of emojis (1031, 253, and 107, respectively). These normative datasets also included other variables such as familiarity, clarity, visual complexity27,36,37, frequency of use36,37, aesthetic appeal and meaningfulness27. Other smaller scale studies collecting valence and arousal ratings have been published in recent years (5,19,20,38; which included a set of 70, 33, 74 and 18 face emojis, respectively).

There is another framework for describing the human affective space, derived from basic (discrete) emotion theories, which posits the existence of a set of biologically determined emotions, with specific neural signatures, cognitive appraisals, facial expressions and behavioural action tendencies (e.g.39). There is variability in the number of emotions proposed, but most authors agree on five discrete emotions: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust (see40). Although much smaller in number than those focusing on valence and arousal, some normative studies have collected data on the association of different types of stimuli, such as words, with these five discrete emotions (e.g.41–44).

As can be seen above, the most widely accepted proposal encompasses four negative emotions (sadness, anger, fear, and disgust) and one positive emotion (happiness). More recent emotion theories, however, emphasise the need for a further differentiation of positive emotions. They conceptualise positive emotions as a set of specific states that facilitate an adaptive response to different types of fitness-relevant resources, and that have their own psychological, behavioural and neurophysiological markers (45, see also46, for an overview). In light of this, it is important to develop emotional lexicons that cover a wider range of positive emotions. This makes particular sense for emojis. The reason is that most emojis are positive2 and are used to communicate positive emotions17. Two recent studies have moved in this direction. Godard and Holtzman47 and Shoeb and de Melo48 developed a lexicon of emojis which included surprise and three positive emotions (anticipation, joy and trust) in addition to the typical four negative emotions (anger, disgust, fear and sadness). However, only Godard and Holtzman47 provided information on user perception through subjective ratings from a large number of participants. On the other hand, positive emotions are even more varied than those considered in the two aforementioned studies45,46.

We present a normative dataset with subjective ratings of 112 face emojis in 13 discrete emotions: anger, sadness, fear, disgust, anxiety, happiness, awe, contentment, amusement, excitement, serenity, relief, and pleasure. Therefore, the study has been conducted within the framework of basic emotion theories39. Furthermore, in line with recent theoretical proposals45, we included eight positive emotions to capture variability in positive emotional experiences. We selected these particular emotions because they have been included in some normative studies focusing on words (e.g.46). This could potentially facilitate future research involving both types of stimuli. Of note, Emoji-SP36 contains all these emoji, so there is also data available on valence, arousal, visual complexity, familiarity, frequency of use, and clarity. This resource will therefore be very useful for a more complete description of the affective properties of emojis, combining the dimensional36 and basic (current data) emotion approaches. It will be also useful for research with emojis in general. Some areas of application include sentiment analysis, social media studies, and chatbot design. For example, the inclusion of emojis has been shown to improve the accuracy of sentiment analysis49,50. In a different field, analysing social media posts can reveal differences in emoji usage relating to gender, age51 and personality52. Notably, emoji use not only provides information about the sender, but also influences how the receiver perceives him/her53, even when the sender is not human. Indeed, some studies have demonstrated that using emojis in human–chatbot interactions can enhance the chatbot’s perceived credibility, competence, social attractiveness54 and warmth55. The dataset developed in this study can benefit all these fields, as researchers can use it to select emojis that are well characterised in terms of their affective and non-affective properties. This will contribute to the rigour of studies and the validity of conclusions.

Methods

Data were obtained from 763 participants recruited through Prolific and three Spanish universities: Universidad de Murcia (Murcia, Spain), Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona, Spain), and Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid, Spain). Of these, 504 were female (66% of the sample) and 259 were male (34%). The mean age was 24.07 years (SD = 9.68; range = 17–70). Participants were recruited via the official communication channels of the universities’ teachers and the Prolific platform. They received either academic credit (university students) or monetary compensation (Prolific participants) for their participation. They signed an informed consent document prior to the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rovira i Virgili (reference CEIPSA-2021-PR-0044).

We selected 112 emojis from the Unicode Emoji 13 version, published by the Unicode Foundation (http://unicode.org/emoji/charts/full-emoji-list.html). All emojis represented faces, most of them anthropomorphic, although there were also some faces of animals (cats, monkeys) and of different creatures (e.g., demons, aliens, ghosts). We chose faces that potentially expressed an emotion.

The emojis were presented in their Facebook version. Participants rated them on 13 affective dimensions that refer to discrete emotions: anger, disgust, fear, sadness, anxiety, happiness, awe, contentment, amusement, excitement, serenity, relief, and pleasure. Participants were given the name of the emotion and its definition. These definitions were taken from42 and46. The instructions and definitions of the emotions can be found in the OSF repository at 10.17605/OSF.IO/WV7UB56. Participants had to indicate the extent to which the emoji reflected the discrete emotion they were rating. They were provided with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all” to “extremely”, to make their ratings. Participants also had the option “I don’t know the emoji” to indicate that they did not know a particular emoji.

Thirteen questionnaires were created, one for each discrete emotion. The 112 emojis appeared randomly in each questionnaire, in PNG format of size 72 × 72. The questionnaires were created and administered online using TestMaker57. The average time to complete each questionnaire was approximately 10 minutes. Each participant completed one or more questionnaires.

Data cleaning was carried out prior to analysis. One-hundred and three responses were removed. We removed 49 responses whose ratings showed a low correlation with the mean of all ratings on the same questionnaire (i.e., r < 0.1). Correlations close to zero are assumed to reflect idiosyncratic response patterns, whereas negative correlations indicate that the participant understood the rating scale in the reverse order. We also removed 54 responses from those participants who completed the same questionnaire twice. There was an average of 79.92 valid responses per questionnaire (range = 69–90, SD = 6.24), and each emoji received an average of 68.69 valid ratings (range = 65–90, SD = 6.23).

Data Records

The dataset is available in XLSX (“emojis_discrete_emotions_database.xlsx”) and PDF (“emojis_discrete_emotions_database.pdf”) format in the OSF repository: 10.17605/OSF.IO/WV7UB56. Each row contains data for a specific emoji, and each column corresponds to a specific variable. The id column contains a unique identifier code for each emoji in the database. This is followed by the ASCII code (ascii_code column). The emoji column represents the visual form of the emoji in their standard Unicode form. The category column classifies each emoji into a specific category for organisation purposes. The dataset contains ratings for 13 discrete emotions (rated from 1 to 5, see Methods), with the corresponding columns for mean ratings ([emotion]), standard deviation ([emotion]_sd), number of valid responses ([emotion]_n), and number of ‘don’t know’ responses ([emotion]_dk). This structure is repeated for the thirteen emotions included in the database: anger, disgust, fear, sadness, anxiety, happiness, awe, contentment, amusement, excitement, serenity, relief, and pleasure.

An XLSX file containing the raw data for the 13 discrete emotions is also available in the OSF repository. The file (“raw_data.xlsx”) consists of 13 sheets, each corresponding to a discrete emotion. Each column represents an emoji (identified by its id), while each row contains the participant’s rating for each emoji on a scale from 1 to 5, with blank cells indicating “don’t know” responses.

Technical Validation

We measured the interrater reliability of each questionnaire by means of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC58). Two-way random effects based on the absolute agreement of multiple raters (2,k) were used. The ICCs were all statistically significant (all ps < .001; M = 0.97, SD = 0.01, range = 0.96–0.98), indicating excellent support for the reliability of the data.

Descriptive statistics and distributions of the variables included in the dataset are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1. All the discrete emotions are negatively skewed, with mean scores below 2.5, which places them below the midpoint of the measurement scale (see Table 1). Nevertheless, each discrete emotion contains emojis with mean scores across the full range of the scale. These results are consistent with those of previous word datasets on discrete emotions42,44,46.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amusement | 2.23 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 4.72 |

| Anger | 1.61 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 4.73 |

| Anxiety | 1.89 | 0.77 | 1.03 | 3.80 |

| Awe | 1.98 | 0.66 | 1.14 | 3.95 |

| Contentment | 2.43 | 0.90 | 1.29 | 4.36 |

| Disgust | 1.55 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 4.54 |

| Excitement | 2.11 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 4.59 |

| Fear | 1.60 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 3.60 |

| Happiness | 2.29 | 1.19 | 1.06 | 4.69 |

| Pleasure | 2.26 | 0.96 | 1.10 | 4.28 |

| Relief | 2.16 | 0.91 | 1.13 | 4.00 |

| Sadness | 1.71 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 4.72 |

| Serenity | 2.33 | 0.90 | 1.15 | 4.32 |

Fig. 1.

Histograms with the distribution of the ratings of the variables.

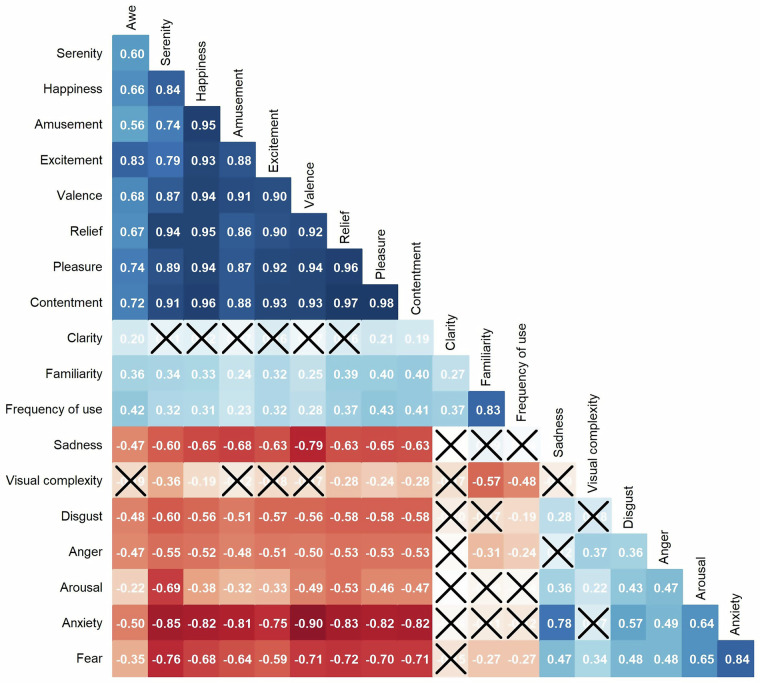

Bivariate correlations between the variables are shown in Fig. 2. We included in these correlations the ratings of visual complexity, familiarity, frequency of use, clarity, emotional valence and emotional arousal from the normative study by Ferré et al.36. Discrete negative emotions (anger, fear, disgust, anxiety, sadness) show a strong negative correlation with valence and a moderate positive correlation with arousal. In contrast, discrete positive emotions (amusement, awe, excitement, happiness, pleasure, relief, contentment, serenity) show a strong positive correlation with valence and a moderate negative correlation with arousal. Furthermore, strong positive correlations are observed between variables associated with negative emotions and similarly between those associated with positive emotions. These results are very similar to those reported by Hinojosa et al.46, who assessed the same discrete emotions using words. The consistency of these results underscores the robustness of the patterns observed in this emoji dataset.

Fig. 2.

Correlogram showing bivariate correlations between the variables. Positive correlations are shown in blue, with darker shades indicating stronger relationships, while negative correlations are shown in red. The “X” in the matrix indicates correlations where the p-value is greater than 0.05. All other correlations have p-values less than 0.05.

Limitations and future studies

This is the first large-scale normative dataset of emojis covering several positive emotions. One limitation, however, is that these data have been gathered only from Spanish people and from a larger proportion of women than men. Previous normative studies of emojis using a dimensional approach show a high correlation between valence and arousal ratings across different countries36,37. This suggests that the perception of the emotional properties of emojis is highly consistent. Therefore, a similar degree of correspondence can be expected for basic emotion ratings, such as those included in this dataset. However, individual differences (e.g., gender and age) and cultural differences may exist, and these are worth investigating in further research. Future studies should also cover a wider range of emotions and more complex emotional states that can be associated with emoji use (e.g.59).

Acknowledgements

Grants PID2021-125842NB-I00 and PID2023-149606NB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and FEDER, UE. Grant 101182959 from the Horizon Europe Framework Programme, HORIZON-MSCA-2023-SE-01. Grant 2023PFR-URV-00196, funded by URV.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication. More specifically, P.F.: Conceptualization, project administration, supervision, funding acquisition, writing original draft and writing review; J.H.: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, data curation, writing original draft; M.A.P.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing review; J.A.H.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing review.

Code availability

No custom code was used. ICC: Function ICC, from the psych package version 2.4.6. Descriptive statistics: Function summarise_all, from the dplyr package version 1.1.2. Histograms: Function ggplot, from the ggplot2 package version 3.5.1. Correlations: Function corrplot, from the corrplot package version 0.95. Software: R version 4.3.1 and RStudio version 2023.06.1 + 524were used.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bai, Q., Dan, Q., Mu, Z. & Yang, M. A systematic review of emoji: Current research and future perspectives. Front. Psychol.10, 2221, 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02221 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kralj Novak, P., Smailović, J., Sluban, B., Mozetič, I. Sentiment of Emojis. PLoS One10, 10.1371/journal.pone.0144296 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Tang, Y. & Hew, K. F. Emoticon, Emoji, and Sticker Use in Computer-Mediated Communication: A Review of Theories and Research Findings. Int. J. Commun.13, 2457–2483 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutet, I., Goulet-Pelletier, J.-C., Sutera, E. & Meinhardt-Injac, B. Are older adults adapting to new forms of communication? A study on emoji adoption across the adult lifespan. Comput. Human. Behav.13, 100379 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones, L. L., Wurm, L. H., Norville, G. A. & Mullins, K. L. Sex differences in emoji use, familiarity, and Valence. Comput. Human. Behav.108, 106305 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prada, M. et al. Motives, frequency and attitudes toward emoji and emoticon use. Telemat. Inform.35, 1925–1934 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall, J. A. & Pennington, N. Self-monitoring, honesty, and cue use on Facebook: The relationship with user extraversion and conscientiousness. Comput. Human. Behav.29, 1556–1564 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konrad, A., Herring, S. C. & Choi, D. Sticker and emoji use in Facebook messenger: Implications for graphicon change. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun.25, 217–235 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin, T.-J. & Chen, C.-H. A preliminary study of the form and status of passionate affection emoticons. Int. J. Des.12, 75–90 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danesi, M. The Semiotics of Emoji. (Bloomsbury, London, 2017).

- 11.Logi, L. & Zappavigna, M. A social semiotic perspective on emoji: How emoji and language interact to make meaning in digital messages. New Media Soc.25, 3222–3246 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barach, E., Feldman, L. B. & Sheridan, H. Are emojis processed like words?: Eye Movements reveal the time course of semantic processing for emojified text. Psychon. Bull. Rev.28, 978–991 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeifer, V. A., Armstrong, E. L. & Lai, V. T. Do all facial emojis communicate emotion? the impact of facial emojis on perceived sender emotion and text processing. Comput. Human. Behav.126, 107016 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robus, C. M., Hand, C. J., Filik, R. & Pitchford, M. Investigating effects of emoji on neutral narrative text: Evidence from eye movements and perceived emotional valence. Comput. Human. Behav.109, 106361 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissman, B., Engelen, J., Baas, E., Cohn, N. The lexicon of emoji? conventionality modulates processing of emoji. Cogn. Sci. 47, 10.1111/cogs.13275 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Holtgraves, T., Robinson, C. Emoji can facilitate recognition of conveyed indirect meaning. PLoS One15, 10.1371/journal.pone.0232361 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Riordan, M. A. The communicative role of non-face emojis: Affect and disambiguation. Comput. Human. Behav.76, 75–86 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherbonnier, A. & Michinov, N. The recognition of emotions beyond facial expressions: Comparing emoticons specifically designed to convey basic emotions with other modes of expression. Comput. Human. Behav.118, 106689 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaeger, S. R., Roigard, C. M., Jin, D., Vidal, L. & Ares, G. Valence, arousal and sentiment meanings of 33 facial emoji: Insights for the use of emoji in consumer research. Food Res. Int.119, 895–907 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutsuzawa, G., Umemura, H., Eto, K., Kobayashi, Y. Classification of 74 facial emoji’s emotional states on the valence-arousal axes. Sci. Rep. 12, 10.1038/s41598-021-04357-7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Garcia, C., Țurcan, A., Howman, H. & Filik, R. Emoji as a tool to aid the comprehension of written sarcasm: Evidence from younger and older adults. Comput. Human. Behav.126, 106971 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampietro, A. Emoji and Rapport Management in spanish WhatsApp chats. J. Pragmat.143, 109–120 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das, G., Wiener, H. J. D. & Kareklas, I. To emoji or not to emoji? examining the influence of emoji on consumer reactions to advertising. J. Bus. Res.96, 147–156 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson, W., Huang, P. & Yu, Q. Emoji and communicative action: The semiotics, sequence and gestural actions of ‘face covering hand’. Discourse Context Media26, 91–99 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández-Gavilanes, M., Juncal-Martínez, J., García-Méndez, S., Costa-Montenegro, E. & González-Castaño, F. J. Creating Emoji Lexica from unsupervised sentiment analysis of their descriptions. Expert Syst. Appl.103, 74–91 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura, M., Katsurai, M. Automatic construction of an emoji sentiment lexicon. Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining 2017, 1033–1036, 10.1145/3110025.3110139 (2017).

- 27.Rodrigues, D., Prada, M., Gaspar, R., Garrido, M. V. & Lopes, D. Lisbon emoji and Emoticon Database (LEED): Norms for emoji and emoticons in seven evaluative dimensions. Behav. Res. Methods50, 392–405 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tigwell, G. W., Flatla, D. R. Oh that’s what you meant! Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct, 859–866, 10.1145/2957265.2961844 (2016).

- 29.Częstochowska, J. et al. On the context-free ambiguity of emoji. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media.16, 1388–1392, 10.1609/icwsm.v16i1.19393 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW): Instruction Manual and Affective Ratings (Citeseer, 1999).

- 31.Russell, J. A. Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychol. Rev.110, 145–172 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurdi, B., Lozano, S. & Banaji, M. R. Introducing the open affective standardized image set (OASIS). Behav. Res. Methods49, 457–470 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchewka, A., Żurawski, K. & Jednoróg, A. Grabowska, The Nencki Affective Picture System (NAPS): Introduction to a novel, standardized, wide-range, high-quality, Realistic Picture Database. Behav. Res. Methods46, 596–610 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferré, P., Guasch, M., Moldovan, C. & Sánchez-Casas, R. Affective norms for 380 Spanish words belonging to three different semantic categories. Behav. Res. Methods44, 395–403 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warriner, A. B., Kuperman, V. & Brysbaert, M. Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas. Behav. Res. Methods45, 1191–1207 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferré, P., Haro, J., Pérez-Sánchez, M. Á., Moreno, I. & Hinojosa, J. A. Emoji-SP, the Spanish emoji database: Visual complexity, familiarity, frequency of use, clarity, and emotional valence and arousal norms for 1031 Emojis. Behav. Res. Methods55, 1715–1733 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheffler, T. & Nenchev, I. Affective, semantic, frequency, and descriptive norms for 107 face emojis. Behav. Res. Methods56, 8159–8180 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischer, B. & Herbert, C. Emoji as affective symbols: Affective judgments of emoji, emoticons, and human faces varying in emotional content. Front. Psychol.12, 645173, 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645173 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ekman, P. Facial expression and emotion. Am. Psychol.48, 384–392 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briesemeister, B. B., Kuchinke, L. & Jacobs, A. M. Discrete emotion norms for nouns: Berlin affective word list (denn–bawl). Behav. Res. Methods43, 441–448 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ćoso, B., Guasch, M., Bogunović, I., Ferré, P. & Hinojosa, J. A. Crowd-5E: A Croatian psycholinguistic database of affective norms for five discrete emotions. Behav. Res. Methods55, 4018–4034 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferré, P., Guasch, M., Martínez-García, N., Fraga, I. & Hinojosa, J. A. Moved by words: Affective ratings for a set of 2,266 Spanish words in five discrete emotion categories. Behav. Res. Methods49, 1082–1094 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinojosa, J. A. et al. Affective norms of 875 Spanish words for five discrete emotional categories and two emotional dimensions. Behav. Res. Methods48, 272–284 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stadthagen-González, H., Ferré, P., Pérez-Sánchez, M. A., Imbault, C. & Hinojosa, J. A. Norms for 10,491 Spanish words for five discrete emotions: Happiness, disgust, anger, fear, and sadness. Behav. Res. Methods50, 1943–1952 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiota, M. N. et al. Beyond happiness: Building a science of discrete positive emotions. Am. Psychol.72, 617–643 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hinojosa, J. A. et al. The bright side of words: Norms for 9000 Spanish words in seven discrete positive emotions. Behav. Res. Methods56, 4909–4929 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godard, R. & Holtzman, S. The multidimensional lexicon of emojis: A new tool to assess the emotional content of Emojis. Front. Psychol.13, 921388, 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921388 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shoeb, A. A., de Melo, G. EMOTAG1200: Understanding the association between emojis and emotions. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-main.720 (2020).

- 49.Liu, C. et al. Improving sentiment analysis accuracy with emoji embedding. J. Saf. Sci. Resil.2, 246–252 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoo, B. & Rayz, J. T. Understanding Emojis for Sentiment Analysis. The International FLAIRS Conference Proceedings34, 10.32473/flairs.v34i1.128562 (2021).

- 51.Koch, T. K., Romero, P. & Stachl, C. Age and gender in language, emoji, and emoticon usage in instant messages. Comput. Human. Behav.126, 106990 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kennison, S. M., Fritz, K., Hurtado Morales, M. A. & Chan-Tin, E. Emoji use in social media posts: relationships with personality traits and word usage. Front. Psychol.15, 1343022, 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1343022 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cavalheiro, B. P., Prada, M. & Rodrigues, D. L. Examining the effects of reciprocal emoji use on interpersonal and communication outcomes. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh.41, 2147–2168 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beattie, A., Edwards, A. P. & Edwards, C. A Bot and a Smile: Interpersonal Impressions of Chatbots and Humans Using Emoji in Computer-mediated Communication. Commun. Stud.71, 409–427 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu, S. & Zhao, L. Emojifying chatbot interactions: An exploration of emoji utilization in human-chatbot communications. Telemat. Inform.86, 102071 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emoji-Dis: A dataset of emojis characterised in 13 discrete emotions. 10.17605/OSF.IO/WV7UB (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Haro, J. Testmaker: Aplicación para crear cuestionarios online, (available at http://jharo.net/dokuwiki/testmaker) (2012).

- 58.Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med.15, 155–163 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buono, P., De Carolis, B., D’Errico, F., Macchiarulo, N. & Palestra, G. Assessing student engagement from facial behavior in on-line learning. Multimed. Tools Appl.82, 12859–12877 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No custom code was used. ICC: Function ICC, from the psych package version 2.4.6. Descriptive statistics: Function summarise_all, from the dplyr package version 1.1.2. Histograms: Function ggplot, from the ggplot2 package version 3.5.1. Correlations: Function corrplot, from the corrplot package version 0.95. Software: R version 4.3.1 and RStudio version 2023.06.1 + 524were used.